I’ve been putting off writing this note because I genuinely cannot comprehend how my time here is over. When I first got to Emerson College, journalism felt like a chore. Hard news never appealed to me, but it was the route I thought was the most “realistic.” I was truly convinced I would work for a local newspaper for the rest of my life until I was introduced to the concept of music journalism at a Wolf Alice concert in November 2021. Abby and I enthusiastically waited in line with a fellow Emersonian Nora Onanian (shoutout). Nora pulled out a tiny notebook and began writing notes. “What is that for?” I asked, in which she responded it was for a WERS concert review. I, of course, followed up with a million questions because never once did I think of combining my indescribable love for music with my passion for writing and connecting with others. After the show, we luckily met Wolf Alice, in which I accidentally introduced myself as a music journalist to the bassist Theo Ellis. I had no idea why it slipped out of my mouth. I assumed it was nerves, but maybe my gut knew what my path was all along. The next month, I eagerly applied to Five Cent Sound to get started as a writer and editor. I even arrived at the first general meeting 15 minutes early to make a good impression (LOL). My first semester provided me with insane opportunities to profile my favorite artists and even attend the Dua Lipa concert that jump-started my unhealthy obsession (If you know.. Boy do you know). By month one at Five Cent Sound, I knew I had to incorporate music into my career somehow.

I fell in love with this magazine, and I knew I needed to be promoted to the e-board somehow. I became the Head Online Director in fall 2022, thanks to the lovely Ashley Onnembo who believed in me. The blog became my baby (and still is…) and only deepened my attachment to this organization. By the end of the year, Ashley asked if me and Abby would be interested in becoming CoEditors-in-Chief. To be fully transparent, we freaked out for MONTHS after accepting the position. We wholeheartedly believed we could never handle running an entire organization with 150 members, but we were so very wrong. Listen, It was never sunshine and rainbows (e.g. crafting the last issue in the Iwasaki Library for 30 hours), but being Co-Editor-in-Chief has been the most rewarding aspect of my Emerson career, and I mean that. It has been such an honor to witness the mindblowing talent from every single one of you guys on staff. We are so grateful for every piece of content anyone has ever put out for us. I love this maga zine, and I will forever cherish it for the rest of my life. I hope you all enjoy this issue :)

Love, Alexa Maddi xoxo

When I first arrived at Emerson in the fall of 2020, I felt pretty lost as a journalism major. I lacked a known focus within the field and felt as though I was behind my peers due to a lack of experience. In the spring of 2021, I saw a merch fundraiser for a student organization called Five Cent Sound. Interested in the cool design of the sweatshirt, I checked out Five Cent Sound’s Instagram and blog and was enamored by what the publication had to offer. I had just started to discover that I enjoyed writing about music, so I knew this would be a great collective to join. From the beginning, the organization has been such a welcoming place when it comes to sharing your vision for art, writing, and other platforms of expression. When I scored my first print article that semester, I was also encouraged to take on the task of creating my own visuals, which was a much-needed push to discover my creative capabilities when it comes to art and design. That semester, I truly found my passion for writing and discovered my interest in music journalism.

Throughout the past few years with Five Cent Sound, I’ve been able to grow as a writer and I’ve been lucky enough to have been fully immersed in the talent of the Boston music scene. I’ve gained confidence in my writing abilities that I don’t think I would have earned without being a part of FCS. The inspiring display of leadership by Dani Ducharme, Kristen Cawog, Ashley Onembo, and Paulina Subia taught me everything I know and assured me that I’d be able to

successfully follow in their footsteps as a co-leader of Five Cent Sound. I was almost psychotic enough to take on the role alone, but I made one of the best decisions of my life asking my best friend and roommate Alexa Maddi to take on the responsibility of leadership with me. I wouldn’t have been able to make any of this happen without her and I’m so grateful we were able to bond through music and our hatred for that digital journalism class in the spring of freshman year. I’m also incredibly grateful for the staff we’ve had throughout my year of being a Co-Editor-in-Chief. I’ve never seen such passion, creativity, and knowledge come together to create incredible bodies of work. Watching the organization grow under Alexa and I’s guidance has been amazing to witness and we can only hope for more well-deserved growth in the future And to the e-board, your drive and talent were vital to Alexa and I’s sanity countless times. I can’t believe my time with FCS has already come to an end, but I will forever be grateful to have been part of such a welcoming community of music lovers and artists. Keep listening, keep learning, keep creating and support local music! :)

Love, Abby Stanicek xoxo

Exec

Co-Editor-in-Chief // Alexa Maddi

Co-Editor-in-Chief // Abby Stanicek

Creative Director // Rose Luczaj

Head & Managing Editor // Grace Chapdelaine

Head Online & DEI Director // Daphne Bryant

Assistant Online Editor // Izzy Astuto

Social Media Manager // Katie Palmer

Photo Coordinator // Ally Giust

Playlist Coordinator // Annaliese Baker

Editorial

General Editors

Dana Albala

Georgia Decker

Maya Eberlin

Rachel Hackam

Norah Lesperance

Emie Mcathie

Hollie Raposo

Emily Zeitz

Copyeditors

Georgia Decker

Kayla Gibbs

Sophie Hartstein

Norah Lesperance

Emie Mcathie

Alison Sincebaugh

Creative

Liam Alexe

Nicole Armstrong

Hazel Armstrong-McAvoy

Christina Casper

Shell Garcia

Aryssa Guerrero

Sydney Johnson

Melanie Pozo

Hollie Raposo

Rocio Sola Pardo

Justin Wise

On the Death of Genre by Jagger van Vliet // 9

Keep Them Dancing by Izzie Claudio // 15

Poetry of the Working Mind in Real Time: The Art of Freestyling by Gianna Di Cristo // 21

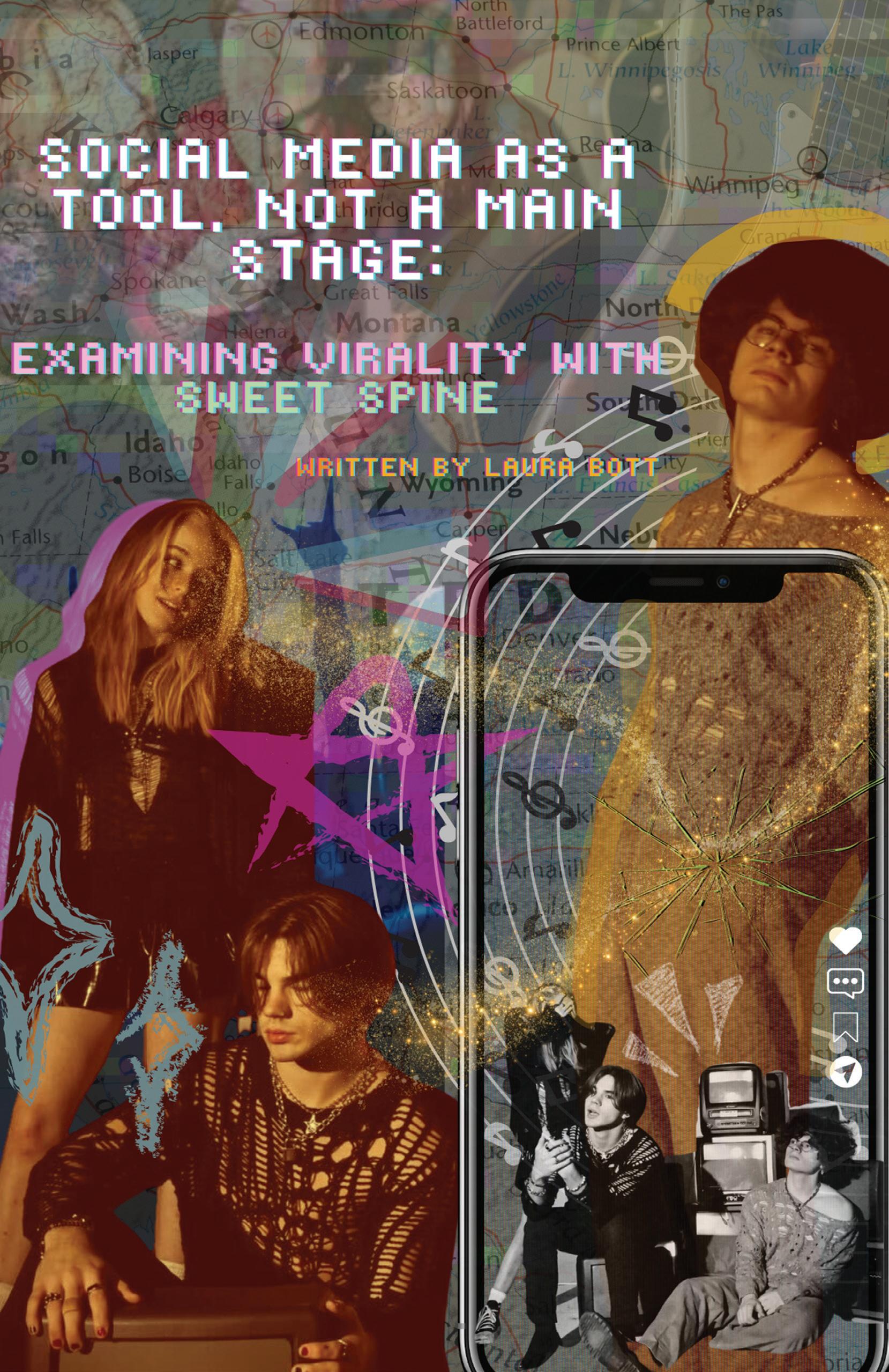

Social Media As a Tool, Not a Main Stage: Examining Virality With Sweet Spine by Laura Bott // 29

The Sound of Resistance by Rocio Sola Pardo // 39

Techno in Transit by Melanie Pozo // 45

Exploring Improvisation: Jam Music by Roxie Jenkin // 53

Live Legends: The Most Spontaneous On Stage Moments in Music by Emma O’Keefe // 63

A Writer’s Embrace of the Bass by Nina Rezendes Fauci // 71

Taking Coltrane to Work by Gavin Miller // 77

Improvisation in Music and Life by Abby Stanicek // 83

Death of the Artist by Izzy Astuto // 89

The Many Lineups of Paramore and the Musical Effects of Them by Julia DaSilva-Novotny // 95

Now It’s Just Me, Myself, and this Tune Payton Cavanaugh // 103

Visual by Justin Wise // Article by Jagger van Vliet

“Genre” is now completely and utterly obsolete.

Yes, it is the case that nearly all of the music we consume is generally categorized and sorted plainly into one of many neat divisions. This has been an unavoidable convention for decades. It would seem as though we cannot view music without these parameters. Just as in the industries of film and literature, music has always been delivered in a way that was dismally expected. Yet, delivered unto the age of the internet, this idea has begun to dissolve.

I believe, firstly, that given time, creative-minded people cannot be helped from straining against older boundaries. As such, the moment when nascent music-sharing apps like SoundCloud arrived into the music industry, artists were already predisposed toward the alternatives to mainstream distributors.

The purpose of any artist is to always strive for a more direct vein, a more immediate connection to their audience. Here is the mainline artery, happily disconnected from the record labels who had, until this time, dictated what music was able to reach the public. Within these apps, intense subcultures developed naturally, or rather, a new music that began to distort the firmly established way of things. Immutable to a fault, record labels refused to acknowledge the internet’s zeitgeist. In truth, they failed to under-

stand the importance of this new horizon, which remained in ever-constant motion.

This was an immediate oversight and one that artists were far quicker to recognize than their corporate counterparts. Almost immediately, a “SoundCloud generation” instilled itself in the rap community, wherein young artists rose to prominence in a way that could only be made possible by the instantaneous nature of the internet. Virality, above all else, dictates what will succeed, such that eccentric images and personas emerged alongside the music that was never given a chance before. Insert the talent of artists, Rico Nasty, Denzel Curry or 21 Savage. This was, to my mind, an intensely creative time, ripe with the exact sort of passion that had perhaps dwindled in the previous years. Artists — truly unheard of, young artists — were rewarded now for understanding how to use a tool that still remained obscure to those formerly in control.

It was in that moment (2016–2018) that the very notion of genre began to fall away. Record labels had, until this point, relied on genre more so as a tool for marketing than anything else. But in this new stage, genre was treated more to the effect of loose suggestion. The boundaries which had, until this point, governed which music fit into which box appeared obsolete. Genre was too set in stone, too immovable for a culture which hates stagnancy.

Artists have come to understand that

there is inherent worth to being in touch with the heartbeat of the internet. Though often a vaporous, impossibly abstract thing, when a musician does manage to place their finger perfectly on the pulse, the art that ensues is immediately of a different essence.

Lil Nas X exists as a prime example of a musician who understands the internet. Through admixtures of passion, outrage and sheer audacity, Lil Nas X captivates the internet, while simultaneously propelling art itself. There is rare creativity in this, and perhaps the youth recognize some mutual respect for themselves reflected by the culture they helped develop.

To provide a directly contrasting failure: often in this era, record labels who found themselves desperate to commercialize would attempt to forcefully insert a musician into the scene. Known notably as industry plants, this title was given to musicians who arrived abruptly into the music industry with the aegis of a powerful label to promote their success. Though the term became readily overused, artists like Jack Harlow, Dua Lipa and The Kid Laroi have all been the targets of this label. Regardless of veracity, there exists, on the internet, a distinct sense of justice that seems to recognize insincere, ersatz or otherwise corporate artistry.

As it presently stands, art on the internet has matured well into an always-moving, intensely creative thing. Musicians must now

strive to keep up with this erratic landscape where, at one moment, a single trend might skyrocket or viscerally undo any body of work. And, though this effect could be seen as rightfully exhausting, I feel that true respect ought to be directed to the select musicians who have mastered that curious art of remaining fluid.

The musicians who have established themselves in the internet’s zeitgeist or, better still, worked to shape the zeitgeist itself, are those who have not remained stubborn in their art. To remain obdurate is a grave error in the age of the internet. Refusing the opportunity to develop music beyond old parameters means being left behind by the new voices.

Here, we see a number of encouraging developments: artists breaking down typically gendered sounds, incorporating live orchestras or choirs, sampling from otherwise obscure records and even going so far as to switch genres entirely.

Observe musicians in the nature of Lil Yachty, who, after establishing himself for many years within the rap community, released a veritably unexpected project that was deeply ensconced in the sounds of psychedelic rock. More in this vein, musicians Rico Nasty and WILLOW have also moved seamlessly between rock, punk, rap and pop.

Increasingly, artists are displaying comfort in venturing from their established restrictions. Or, more to the point, they are ceas-

ing to see these restrictions at all.

It is no longer a jarring thing to see a musician break away from their established sound. Or, if it is jarring, then there is a newfound openness that was perhaps not present before. In this way, even artists who stand to lose far more are experimenting with different genres. We have seen mainstream artists Beyoncé and Lana Del Rey foray into country music, and even hip-hop legend Kendrick Lamar incorporates blues and jazz into his works. More often than not, these fluid musicians bridge the gaps between genres so seamlessly that it is difficult even to describe their sounds accurately. This is what I mean when I say that genre has become obsolete: music is now allowed to exist solely for itself.

The internet, constantly changing and evolving, has produced a generation of musicians who are much the same. Spontaneity is rewarded and unplanned art receives the attention it deserves. The music that comes from this moment is diverse, intensely creative and passionate above all else. It is as near to authentic expression as we have ever been. It is my sincerest hope that this spirit of independence — of riotous creation — continues to pave a new way for music and for art.

Article by Izzie Claudio // Visual by Liam Alexe and Christina Casper

You go to a club and hear the muted bass from outside. As you enter, it’s almost impossible not to move your body. The music echoes in your ears and pricks at your skin. The DJ is bouncing in their booth, and the song begins to morph into something new. The crowd sparkles with excitement as they realize the ingenious way two songs are now playing at once. Everyone cheers even louder, everyone dances even more.

Dance music has become a vital genre in the music world. The grooves that we hear today, that keep our bodies moving, have their roots in house music. Take Beyonce’s 2023 album Renaissance for example: this album, chock full of dance hits, is a love letter to house music. House is an important foundation for a huge portion of the dance music we see today, and what’s at the core of house music? Mixing.

A Brief History of House

Disco dominated the clubs in the 70s, but it began to decrease in popularity as the 80s began. DJs searched for new and innovative ways to keep people dancing, so house was created out of experimentation. DJs such as Frankie Knuckles, Larry Levan, and Ron Hardy returned to their disco records to find the answer. They were also influenced by drum machines, which appeared heavily in the pop music of the 80s. This led to the question, what if we combine the rich grooves of disco

and introduce an electronic twist? DJs then became producers, exploring the abilities of various drum machines, such as, most importantly, the Roland TR-909. Its recognizable drum beat is the connecting thread in the sound of house. The key elements laid before the DJs: the bright funk and vocals of disco and the bone-rattling bass of the drum machine. House music was born and DJs changed the game for dance music in the underground clubs of Chicago, NYC, and Detroit. Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body” combines a soulful piano riff with a hypnotizing beat proclaiming, “Gotta have house music all night long.” Frankie Knuckles combines a fun techno beat with a sensual ballad of love in “Your Love.” Larry Heard’s “Can You Feel It” is a masterclass in production using a drum machine, and features a powerful monologue about the spirit of house music, “You see, no one can own house music / Because house music is a universal language, spoken and understood by all.”

Innovation and Mixing on the Dance Floor

Early house songs were often heard for the first time on the dance floor, and DJs created the tracks with dancers in mind. DJs built dance breaks into the entrancing tunes, which allowed for an explosion of movement on the floor. Another key innovation was the introduction of another song while the first continued to play, also known as mixing. This blending of songs created a new sound altogether. The music was continuous, tracks flowing in and out in a never-ending wave of deep beats. This practice continues today, expand-

ing from house into several branches of dance music and techno. Unique mixes leave audiences happily surprised and begging for more. The unexpected mixes are a welcome sound at a party, club, or performance.

The Minds Behind the Music

With the rise of the internet, there are DJs almost everywhere you look. A quick search on YouTube, will provide access to endless videos of live sets. What was once heard solely on the dance floor can easily be watched and appreciated.

Whether it’s a college student mixing together their favorite early 2000s hits or a parent showing their child the ropes, it’s all born from their own ideas. DJs are always bringing something new to the turntable.

Rafael Rodriguez, whose DJ name is Lego, started mixing at 11 years old. He was always surrounded by house music, learning the ropes with a friend on basic DJ equipment. Keep in mind, this was the 80s. Mixing was done using vinyl, and skills like matching the beats weren’t always perfect. Lego regularly does live sets, and he makes sure that his transitions follow a clear path, moving smoothly from one song to the next. “I have an idea of where I wanna go…and then I take it from there. I go on a journey,” he says. The music is always moving forward, there’s no time to stop and think about what’s going to happen next. “I’m always thinking like a chess

player,” he says. “Two, three songs ahead.” Transitions are key, and Lego is always asking himself, “How am I going to get from one place to the next?”

Lego emphasizes a keyword when it comes to mixing: vibe. “It all goes back to the vibe,” he says. It’s important to establish that connection between the crowd and the DJ.

“Once I got them, it’s a roller coaster ride… we’re going on a journey,” he says. He notes the importance of reading the room and emphasizes that keeping the vibe strong is crucial. It’s an art form to establish a strong connection between the DJ and the crowd, and it’s what makes mixing such a unique and soulful experience.

The Techniques

Mixing is a process of trial and error. DJs get a feel for what songs go well together and take apart the structure of each song. Where are the breaks in the vocals or instrumentation? Do I need to speed up this next song to match the beat of the song currently playing? Where is the best place to start bringing in the next song? DJs, like Lego, ask themselves all of these questions when they craft a mix. A mix can last hours, as each song continues into another. The most important practice is to keep the beat. One, two, three, four. While waiting to introduce the next song, move your record (or whatever circle you have on your board) to the beat making that record scratch motion. One, two, three, four, release! Keep in mind where the dance breaks are, this is often the best time

to start bringing in the next song so there isn’t too much going on at once.

There are foundational techniques when it comes to mixing, but at the end of the day, every DJ mixes differently. There’s no one correct place to bring in the next song, and there are several fun knobs on the board that continue to make the sound into something new and unique. If multiple DJs were given the same songs to mix, each outcome would be different because it all depends on what the DJ wants to do at that moment. How do they want to spice up the tune? How do they make the crowd dance more? Sometimes what may seem intentional could be a cover-up for a mistake. Unless you are in the mind of the DJ, you never know what they’re cooking up in the booth.

“The human voice is enchanting. You combine that with something to say based on your experiences, based on your political understandings, and then you weave the words in such a way that it’s somewhere in between song and speech, but it’s not a speech, and it’s not a song, but you become you in your poetry.”

— Abiodun Oyewole, The Last Poets

Improvising in rap is known as freestyling, a key part of the genre where artists gain respect amongst their peers and audiences. Even though the landscape of rap has changed, freestyling should be recognized for playing a role in building up the genre to what it is today.

The definition of freestyle, as many don’t know, is a term whosedefinition has changed. Originally it was meant to categorize a rap that wasn’t about anything specific in subject matter, but rather be able to highlight how expansive one’s vocabulary and skill to string together words were. “Off the dome” was the correct terminology in the 80s. In a 2017 interview with Complex Magazine, West Coast rapper Myka 9 recalls the term “freestyling” being coined when he heard it in the skateboarding and BMX community growing up. He says he started referring to off-the-dome rap as freestyling and it stuck, eventually catching on to East Coast rappers, which is why we refer to the art form as freestyling today.

In the documentary Freestyle: The Art of Rhyme, Abiodun Oyewole, half the duo of The Last Poets, explains that freestyling is bigger than rap, and is a testament to the humanity and perseverance of Black folks. “A lot of people don’t realize that hip-hop was born as the need to get-rid-of, to exercise the rage,” says Oyewole, “Then I consider all the music we’ve created and how much we have produced out of the so-called pain, the so-called pathos, and I think about how when you create from the anger, you start to heal yourself.”

While rapping was officially born in the Bronx, New York in the 70s, its roots can be seen in Black churches many years prior.

Jazz musician and historian Eluard Burt II explains that when preachers get up in front of the church to deliver a sermon, they speak in a way that falls in line with the atmosphere, catching a rhythm. Sermons are meant to address past and present events and show how God gives us context to navigate through them. “He [the preacher] has to get more than a cadence going, he’s got to get a rhythm going. It’s the rhythm that signifies and identifies where he goes next,” says Burt. Sometimes there is no planned speech, but rather they speak from the heart in that moment. Off the dome, one might say.

Freestyling can take place anywhere, any time, but there were two main events where they thrived: Battle Raps and Cyphers. Battle

Raps are exactly what they sound like: going head-to-head with another MC to see who could produce the cleverer diss to one another to get crowds going. It takes place on a stage in a venue, other times in public. Two people must stand before an audience and showcase what their talent, while a host moderates it. In Los Angeles in 1989, The Good Life Centre opened as a place for artists to make a name for themselves with freestyling. In New York City, The Lyricists Lounge opened in 1991 to do the same. This gave underground rappers an environment to thrive and develop.

My first impression of battle rap was Eminem’s tale to fame in 8-Mile and on MTV’s Wild N’ Out. It was always so impressive to me how quickly someone could churn out words and disses with no hesitation, saying something smart and witty in a matter of seconds. Being able to step back after hearing someone throw out a line that forces you to connect the dots also adds to the art, heightening the respect I have for it. Cyphers are similar, but they are a little more intimate. Usually taking place in a park, or somewhere in public, a group of people circle up and compete to see who has more intricate rhymes. It does not have to get personal, but it can. Cyphers can let anyone in on the beat, taking turns with each other, not just two people. As a teenager, I used to watch XXL Magazine’s Freshman Class Cypher on YouTube annually. Although it is a handpicked group and not just a group of people from around the neighborhood, the concept stays the same. The

first one I ever watched was the 2016 Cypher, which included Lil Uzi Vert, 21 Savage, Kodak Black, Denzel Curry, and Lil Yachty. Looking back at it now, these artists are prominent in the rap space or have been at some point, winning Grammys and becoming favorites, even if their freestyle was not strong. Other cyphers where I was introduced to artists for the first time include the 2019 Cypher, which featured Megan Thee Stallion. I remember thinking, “Damn, she didn’t take a breath or skip a beat. There’s no way she won’t break through after this.” As a woman in rap, she brought her A-game and completely washed her male counterparts. She brought this oldschool, Houston style, and was relentless. XXL Freshman Cyphers go back to 2011 when Mac Miller and Kendrick Lamar both had the chance to get on the mic, and it’s crazy to watch these artists who are so influential now in the infancy of their careers.

Some of the most notable names in rap came up on the 90s radio show The Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito Show: DJs Robert “Bobbito” Garcia, a Def Jam Records promoter, and Adrian “Stretch” Bartos, a New York City club DJ. The duo hosted the show from 1990 to 1998 at Columbia University’s WKCR. It premiered artists like Notorious B.I.G, Nas, Wu-Tang Clan, DMX, Talib Kweli, and Busta Rhymes. The most recognized freestyle to come out of this show was the Big L and Jay Z recording that took place in 1995. What was so significant about this freestyle was how it launched Jay Z’s career, and a year later he dropped his first album, Reasonable Doubt. Hearing Jay

Z in the very early stages of his career is interesting. It definitely isn’t one of his strongest bars, but I did enjoy “For greater understanding, I’m landing blows / Knocking sense into those that oppose me / Enticing when slicing through tracks / You’re screamin’ ‘Jesus Christ, he’s back!’ and God knows he can rap.” My favorite line of Big L’s from this freestyle is “My .38 works great, so make a mistake and hesitate / I can’t wait to demonstrate this nickel plate / He didn’t listen to what I was speaking / He started reaching, so I left him sleeping with his temple leaking, alright?” That’s hard.

Other freestyles that took people by surprise include King Los on Sway in the Morning in 2015, in which he rapped for ten minutes straight during the Five Fingers of Death Challenge. The line that made me go “damn” was “I don’t really get it / I got two brains in the same mind / I break it down and get two thoughts at the same time.” Straight poetry, what else can I say about it?

J. Cole’s freestyle from 2021 on LA’s Power 106 reignites what so many people appreciate and love about hip hop in the past. He raps over two beats and aces it each time. The wordplay in the first part of the freestyle wowed me: “Put the fear of God in ******, I’m pure Devil / Walking contradiction my description / Off the top, magician, compositions nonfiction / Shitted in the competition’s pot to piss in.” It’s not just saying long words that rhyme with each other, it’s a well-structured diss that he didn’t have to think about writing beforehand. It left his

brain like it was no big deal. It’s admirable to see one of the biggest rappers of today further prove why he’s so praised.

What all these freestyles have in common is not only being able to prove that they can impress anyone on the spot, but also the fact that everything came off the tongue so effortlessly—it felt natural. Never once did it feel like they were offbeat or that they were struggling. It’s also about the bravado, the cockiness that can be conveyed—and rightfully so.

Although freestyling is not required for artists to gain a following nowadays, it is still looked at fondly by those who grew up in the golden age of hip-hop. Recognizing the skill and output it takes from within to be able to perform on the spot is like no other.

Many one-hit wonders have graced the ears of listeners around the world, opening a door to the music industry just for it to slam shut in their faces soon after. Who let the dogs out? Did video really kill the radio star? These are questions we may never know the answer to, as these artists have since vanished from everyone’s radars. This phenomenon has occurred time and time again over the decades and has only become more rampant following the rise of video-sharing platforms like Instagram and TikTok. While some artists seem like they were born to perform and experience success, others must try much harder to get their songs heard. Those who frequently promote their music online may suddenly be trending for an instant or two, but it’s unclear what most do with these short-term moments moving forward. To further examine the process of creating and releasing music, let’s deep dive into Greenville-based shoegaze/alt-rock band Sweet Spine, as they balance consecutive waves of virality, a growing audience, and what comes after the door has been cracked open.

Sweet Spine first experienced the suddenness of virality with their single “Darkness.”

Released in the summer of 2023, “Darkness” gained traction when lead vocalist and creator of Sweet Spine, Fox Haynes, posted a TikTok to the song, which subsequently received millions of views and thousands of comments. Going from zero to 100 in such a short period was a lot of weight for a few teenagers to carry, which led to a shift in how the band needed to function: “Original-

ly, ‘Darkness’ was the whole reason we needed management because it just became so much with a working lifestyle that I couldn’t handle all the engagement, messages, and interactions we were getting” Haynes says.

While changes in visibility were quickly occurring for Sweet Spine, so were changes in bandmates. Haynes and current drummer Brannan Crook were thrown together when Sweet Spine’s original drummer was unable to enter the 21+ venue for their show. With two hours until showtime and a two-hour drive to the venue, Haynes called Crook to fill in for the missing member. A few months later, he would become a permanent band member – “From then on, I was like ‘damn he’s gotta play drums for us’” says Haynes.

Brannan Crook: Joining in the middle of that wave of blowing up, gaining traction, and being in those management calls, I was just kind of dumped into the deep end of what a band could be.

Further changes were made when scheduling conflicts left them looking for a new bassist. Asked to join through Instagram DMs without so much as a trial practice run, Taylor Priola was similarly thrown headfirst into everything Sweet Spine had to offer. Just over a month later, they would undergo their first release together, dropping the single “888” on November 24, 2023. The band soon posted an Instagram reel at band practice of themselves playing the song, with text on the screen saying, “Hey you, stop scrolling.” Soon after

the video was posted, it steadily grew to 1.5 million views while their follower count went from 6k to 10k to over 40k.

Fox Haynes: With “Darkness,” it was like, “Cool we had one thing do well,” but with “888” there was a lot more pressure for it to do well because it was the next release– and it did.

Not only did this reel do well, but another one of Sweet Spine playing the song at band practice once again received another million views several weeks later.

Haynes: That was reassuring to us that it wasn’t just a moment or fluke, but that if we work hard and promote things, they will grow.

In February, Sweet Spine had another viral reel with the same format. As their followers, listeners, and like counts continued to increase, the band was careful not to become too complacent with this newfound growth.

Crook: Not to put down the online support, but looking at a screen, a human being can’t comprehend the amount of people that is.

Taylor Priola: Internally we were just thinking, “Social media is cool and all these numbers are great and I’m glad we’re growing,” but it didn’t feel real yet. There was a huge aspect of that growth that wasn’t super apparent to us until we went out on tour.

Ultimately, touring for Sweet Spine took those numbers and made them tangible. When

they embarked on a two-month-long tour from the East to the West Coast, they were able to feel that love being reflected in them in a physical space too.

Haynes: A crazy moment for the tour, a little bit less than halfway through, was when we played New Jersey…. Playing New Jersey, to put it simply, was fucking insane. People showed up with posters and guitars for us to sign, and they knew our names.

Priola: Fans were buying merch and asking for photos before they had even seen us play.

Haynes: It was the most “band” show I’ve ever played in my life. We felt like a real band.

Touring their 2022 album C-Section, Sweet Spine experienced a breakout tour that very few bands get to have as their first headline: one where people in states the band had never even been to knew their names and admired them. Part of this wide audience reach was due to their newfound online visibility that pushed their music to individuals across the country, and even across the world. It went beyond likes or follower counts and ultimately revealed a driving message behind the band both as a business and as a project.

Crook: At the end of the day, the last thing we wanna do is ride on virality forever. Social media is a tool, not a main stage.

Through the calculated “quality over quantity” approach that has been working for Sweet Spine’s posting methods thus far, they’ve been able to use this tool to their utmost

advantage. They snagged aspiring opportunities such as their recent spot in the renowned music showcase and festival, South By Southwest, a long-time dream of Priola’s.

Rather than letting the pressure of numbers weigh them down, Sweet Spine seeks to harness it to continue doing what they love in the biggest ways possible.

Priola: The rise of Sweet Spine internationally has only been since July 2023 [when “Darkness” went viral]. In late 2022, we had 10k streams overall. In 2023 it was around 2 million. It’s very motivating to think that if this is the success we gained from [a viral moment] that happened halfway through the year, what is to hold from a full year?

Currently, the band is working on their next upcoming project, writing and recording in an isolated cabin in South Carolina while continuing to promote their music online. They all comment on how stressful this period of time is: juggling meeting deadlines, planning, and maintaining their rapidly growing social media presence.

Haynes: I feel like I’m making the thing that is going to make or break the next ten years of my life. Yet during this nerve-racking period of recovery from tour, Sweet Spine is already ready for the next one. Tour for us is a celebration. Once we’ve been working and posting consistently for six months and grow-

ing, all we can think is that it’s time to get out there and meet these people.

Priola: And see what it’s all for.

And what is it all for, one may ask? Ultimately, this answer lies in connection, both with audiences and with each other.

Priola: An example of that is we have a nowfriend named Elvis who came to the Jersey show. He had posted the first ever “888” cover on Instagram and said he was coming to the show. We invited him to come up on stage with us; he brought his guitar for us to sign. It was all just very surreal.

Within music, there is often an apparent parasocial dynamic between the artist and the fan. Seeing glimpses into the lives of one’s favorite band online and listening to their personal stories through a song makes it easy for hierarchical structures to form, where artists are put on a pedestal above everyone else by those who consume their art. However, Sweet Spine does their best to move away from this dynamic, hoping to form meaningful connections with the people who allow them to do what they love every day.

Crook: There’s a sort of instinct to perform, as performers. When you get all these messages like, “You’re my fav band!” you get put on a pedestal immediately. There’s an instinct and sort of selfish human desire to be That Guy —

Haynes: I am the person you think I am!

Crook: — But also an immense joy in showing

people that I’m just like you.

At the end of the day, Sweet Spine wants you to know that they aren’t That Guy. Or they might be, but they are really just people, too.

Haynes: On tour, it was like wow, all these artists we look up to are just people and feel the same way as we do.

Crook: They all think their music sucks.

Priola: They all think they look ugly in that photo.

Haynes: They all think they’re not big enough or they’re not doing enough, but that’s almost what keeps you going.

And as they navigate these new experiences, the thing moving them forward above all else is getting to experience them together.

Priola: Not only based on fan experiences and interactions, but how we solved issues that we had with shows, mental health, and ourselves, was just a very clarifying thing. It clarified that like, this is staying.

Crook: There were a lot of moments sleeping on the floor, or something with the show fell through, or the car alternator broke and we had to jump it every time we started the car. But there are plenty of other people I could’ve done that with who would not have made jokes about it.

Haynes: I’ve been further than I’ve ever been from home with you guys.

Priola: I think I speak for all of us when I say there really is no one we’d rather be

doing this with. And to be able to celebrate those rewards together, big or small, means we’re doing it right.

Crook: Every morning that we wake up and get to participate in this band in some way, we have succeeded. Even just waking up and being the drummer of Sweet Spine, I have already succeeded.

This “awww” moment of the interview shows us exactly how Sweet Spine has been able to prosper from their recent successes and strive for more every day. Being a part of the band and playing music drives them to improve and adapt to changes thrown their way, all while acting as a collective. Virality has been a valuable asset in getting them to this point, but building from that momentum to create real experiences with fans, and each other, allows them to make something that lasts, rather than relying solely on fleeting one-hit wonder opportunities. There’s a reason why their viral reels have a common theme and general format: casually practicing a song together and showcasing the craft of live performance. It’s why, when they showcase their art in online spaces, there are people ready to embrace it, hold it close, and eventually buy a ticket in the hopes of experiencing their songs in person.

Crook: We really are just three morons on stage who happened to get good at music.

Priola: We’re just silly. And we had a guitar and a car to get here.

Haynes: I hope that anyone who comes across our band notices that first, and I hope they

see that’s all we are: three morons who love our people and who create art. We love the people who love our art and if they don’t love it, we love them anyway. It goes no deeper than that really.

Crook: And I think that’s a lot more beautiful than having 3 performers on stage– more beautiful than having three people who are “meant to be there,” whatever that means.

Rocio Sola Pardo and Justin Wise

The sound of resistance begins with a soothing voice that pierces through the silent atmosphere. It’s followed by the powerful beat of firm hands hitting against drums that blend together in a constellation of uniform rhythms, echoing through the Earth. Joy begins to dance through the crowd, and waves of vibrant, colorful skirts hypnotize you in their passionate spins. This climax of vocals, instruments and dance make up the fabric of the Caribbean folkloric genre of music known as “bomba.”

Considered one of the oldest musical genres in the Caribbean, bomba was born in the Hispanic Caribbean island of Puerto Rico over 400 years ago, when the period of Spanish colonization over the Americas was in its early stages. The musical tradition was created by enslaved people who were forced to work on sugar plantations along the coastal towns of Loíza, Mayagüez, Ponce and San Juan. Most of the enslaved population that was brought to the island consisted of a West African ethnic group called Yoruba, which mainly inhabited parts of Togo, Nigeria and Benin. Although the Yoruba were the main cultural group that dominated the genre, bomba also combines the cultural and musical traditions of the Ashanti ethnic group of Ghana, and the word “bomba” originates from the Bantu and Akan languages of West African regions.

Bomba emerged as a musical outlet for enslaved people to escape from their harsh conditions and celebrate their African heritage.

Bailes de Bomba (“bomba dances”) were spaces where the community of enslaved people gathered to express their anger, frustration and yearning for their home. They also used bomba as a way to commemorate important occasions such as marriages, to celebrate religious ceremonies, to communicate with each other and to plan rebellions against their Spanish colonizers.

Unlike most musical genres, bomba is entirely improvised, and it establishes a dialogue in which the dancer controls the rhythm of the music.

Bomba consists of barriles de bomba (two or more drums of different pitches depending on their size), a maraca held by the Laina (the soloist that leads the other singers) and a cuá, which is a stick drum made of bamboo material. A bomba performance typically begins with the Laina marking the rhythm with the maraca and singing a chorus that is echoed by the other singers. The largest and lowest-pitched drum, called the buleador, then plays a fixed beat that establishes the foundational rhythm of the song. The subidor, or the small, high-pitched drum, then layers the buleador’s beat with an improvised rhythm, and marks the beat of the dancer’s movements in a freestyle manner, establishing a rhythmic conversation between the dancer and the drummer that becomes the main spectacle of the bomba performance. The dancer, who can be a man or a woman, marks the beat of the drum by making sharp and rapid movements with their feet and upper body. The male dancer

usually wears all white with a fedora, and the female dancers usually wear a long plantation skirt with a headscarf.

During the early years of bomba, men dominated the musical performances, while female dancers would complement their rough movements by softly waving their skirts in the background. During the early 20th century, Doña Caridad Brenes de Cepeda, one of the most recognized bomba dancers of her time, broke the traditional mold of the bomba performance when she introduced a more prominent role for women in the genre. Now, women dominate the bomba genre and use the medium to create awareness of female struggles and celebrate their Puerto Rican heritage.

Since its inception, bomba spread throughout the island and evolved into different styles. There are currently 16 styles of bomba, with each of them encompassing a distinct rhythm, tone and purpose. The most prominent bomba styles are yubá, sicá and holandés. Yubá is a style of bomba that is performed at a moderate tempo with a 6/8 rhythm, and is recognized for its slower beat that expresses a solemn and heavy tone. Sicá is the most popular and commercially prominent style of bomba that is practiced all throughout the island. Holandés is considered to be the fastest bomba style, and is one of the only ones that is influenced by enslaved people who weren’t from Puerto Rico. Sicá contains influences from the culture of Dutch enslaved people who lived on the neighboring islands of Curaçao, Aruba, Bonaire and St. Croix, and the name

“holandés” alludes to European or French Creole terms that were developed by the inhabitants of those islands. The unique styles that encompass the bomba genre have a notable influence on popular Puerto Rican genres like reggaeton and salsa, which are widely recognized today.

A new generation of Puerto Ricans are embracing their heritage by preserving and celebrating bomba in innovative ways.

Many young people use bomba to express their resistance against current political struggles, and continue to use the genre as a way to embrace their African heritage.

Despite the brutal mistreatment and oppression that West African enslaved people suffered at the hands of Spanish colonizers, bomba serves as an example of the influence and endurance of the African people that helped shape a crucial piece of the Puerto Rican identity.

When you think of Berlin nightlife, do you think of that one comedy sketch of Nick Kroll saying, “For Breakfast, we will have something cool like a cigarette and, like, a bar of chocolate,” in an awful European accent with obnoxious Techno beats in the back? Well, that’s okay; that is what most TikTok-pilled Gen Z-ers think, too. It is not all Gen Z’s fault: ever since the Techno explosion came out of Berlin, Techno has been solely associated with drugs, escapism and sex. This simplification is not synonymous with the root of rave culture. Although Techno clubs are considered a haven for ravers to escape to a place dedicated to self-exploration without societal pressures, there is an equal amount of looking out as there is looking in.

To get to the essence of Techno and its implications today, we have to go back to 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall. This liberation allowed East and West Berlin to gain access to the Western world, meaning they could begin to explore different genres of music. A significant influence of Berlin’s Techno scene was the musical renaissance of house music in Detroit about a decade before. Similar to how Techno was Berlin’s artistic response to the oppression caused by the Soviet government, Detroit’s invention of house music had a sociopolitical message behind it. During the early ’80s, Detroit was one of the city’s foremost leaders in the auto industry. Detroit, the birthplace of Henry Ford’s automobile company, which gave its citizens many job opportunities, is now a ghost town of old

factories and warehouses after its industry crashed. With the arrival of the technological revolution, the industrialization age stopped, causing the people of Detroit to feel secluded. This dystopian atmosphere inspired musicians to experiment with European electronic music, Afrobeats and soul by remixing different house records.

Thus, the immigration of Techno began, and club promoters flew Detroit DJs to Berlin to showcase their sets. Unfortunately, Detroit is not recognized as the birthplace of electronic dance music in the public eye, and the African American techno pioneers from Detroit are often left out of the techno-revolution narrative. This is not to dismiss Detroit’s influence on Berlin nightlife, however. Berlin incorporated aspects of Detroit’s house scene by taking the foundation of rhythmic beats and industrial elements and stripping down the soul-vocals element to create a more minimalistic, hard-hitting sound. This was an explosive cultural and political era for Berlin and a moment of economic success out of the rubble of the communist regime.

The Berlin techno scene was established because of the apartment blocks and rent controls built in the communist era, which were very cheap. This allowed an opportunity for young artists to escape and make DJing their primary profession and a well-respected job. Although Detroit is considered the birthplace of Techno, Berlin made the genre mainstream, as it was a hub for raves held at exclusive clubs like Tresor and Berghain, Berlin’s most

historical and legendary rave venues.

Due to the popularity of Berlin’s scene in the ’90s, major cities such as NYC and London attempted to emulate Berlin’s nightlife atmosphere. Club Kids started to make their way onto the scene and built the bridge between Techno and fashion. Club Kids is a term for the generation who reclaimed the downtown NYC night scene after Andy Warhol’s death. With Warhol’s legacy of Avant-garde art left behind, Club Kids incorporated this absurdism into their looks. The provocative and outrageous nature of the Club Kids aesthetic started to catch the eye of NYC club promoters, who figured out that Club Kids could play an essential role in their business. They had bodyguards, offices inside the club and even magazine publications. However, this level of respect did not reach past the dance floor. Mayor Rudy Giuliani of New York implemented a mandate over night clubs, which inherently fought to suppress the gender expression of the Club Kids’ scene. In response, Club Kids began hosting their “Outlaw Parties” illegally – in public.

Nonetheless, the Club Kids did not want to be forced underground and fought for a mainstream audience through television talk shows in the absence of social media. Although the Club Kids were made spectacles on these shows, they were able to challenge their hedonistic and drug-involved stereotype by discussing the artistry behind their look and what it means to be a part of the Club Kids community. For them, just attending a rave

was a campy performance; their goal was to get maximum fame not for a specific accomplishment, but simply for their extravagant way of being.

The presence of Club Kids in pop culture shook up the fashion world. It introduced this idea of gender fluidity and diverse queerness, greatly contrasting the cisgender white gay male demographic of Berlin Techno clubs in the ’90s. This is not to say that one way of raving is more authentic than another or that white gay men will forever dominate the Berlin scene. Berlin is gradually becoming more accepting as more queer people of color – for example, Philadelphia-born and Berlin-based DJ LSDXOXO created “Floorgasm,” a Techno Party initiative for queer people of color that gained significant popularity over the years.

The minimalism of Berlin Techno is minimal for a reason: it is impacted by the emotionally stripped aftermath of the Berlin Wall. We can begin to appreciate the German and American ways of Techno by separating them from elitist ideas and focusing on the socio-political motives behind them. Today, we see the influence of the Club Kids in pop culture, from the fashion designs of Jean Paul Gaultier to the ever-growing popularity of DIY/upcycled clothing items, a Club Kid clothing staple. We can also see the commercialization of Techno through the minimization of Berlin into a singular, inauthentic aesthetic on social media. Algorithms filled with Rave OOTDs of influencers wearing all-

black clothing sourced via fast fashion or TikTok POVs: waiting in the Berghain club line. People attack these content creators in the comments, calling them “posers” or saying, “You couldn’t even get into Berghain anyway.” But, can people get over it? Nothing is exclusive anymore because of social media’s expansive platform; it’s the whole point. Yes, stripping Berlin club culture down to Shein black latex is awful, but people need to accept that Techno has gone mainstream. Festivals like Coachella, Gov Ball, Boiler Room, Ultra and the Electric Daisy Carnival festival, a.k.a EDC, are events millions of people flock to worldwide to celebrate electronic dance music, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Underground basement and warehouse raves are still thriving and will remain cherished by the LGBTQ+ community as a safe place for years to come. We can even see this in the local Boston music scene; who doesn’t enjoy a good Allston rave in a sweaty basement that gets shut down by the police an hour later? A great example of how the legacy of Berlin Techno and the NYC Club Kids scene lives on is through “Clear The Floor,” a BIPOC-centered rave collective in Boston. Today, I will be talking with Amaya Thomas Santana, founder of “Clear The Floor,” about the importance of BIPOC spaces in the techno scene and authenticity in rave culture.

Melanie Pozo: Why did you decide to start Clear The Floor?

Amaya Thomas Santana: I decided to start Clear The Floor due to the lack of electronic music in the scene that wasn’t just strictly techno or strictly house music or strictly, like, mainstream electronic music [in Boston]. And, I know a lot of DJs of color, including myself, and there was really just no space for us to play strictly for us. I thought of Clear The Floor for maybe a year – the idea and the concept. Then, I believe 2021, we started Clear The Floor in April. We’re now coming up to our two-year anniversary, which is really fun, and now we strictly highlight DJs of color – queer DJs of color.

MP: Do you see any influence or aspect of rave history in the Clear The Floor community?

Thomas Santana: We’re all inspired by early age, electronic music, right? So, I’m very much inspired by Electro, like Detroit Techno-ghetto-house and Miami bass because I grew up in Miami.

MP: How have you seen the Boston rave scene grow over the years?

Thomas Santana: The rave scene of Boston has been growing for the past five years, like Allston’s always has had a rave scene. We had DJs like Armand Van Helden, we had raves in the tunnels at MIT in the ’90s and early 2000s. That all started disappearing, I would say, in 2010 – to where we are now, where we have really no venues to go to that are very

big and owned by really big corporations. Within the fast past five years, [I’ve seen] a lot of you going back to how you talked about Club Kids, like a lot of just subcultures [are] popping up out of the music scene in Boston. That’s been phenomenal for Clear The Floor, in the sense that the community growing in Boston has really, really pushed it forward, and now you’re seeing more and more parties pop up like Aversion and House of Fag. But, yeah, Boston’s always had a music scene, especially the electronic music scene. We’re just now putting it to the forefront. Like, we have the longest drum and bass residency in the country going on. You know, it’s been going on for 25 years now!

MP: With that being said, what does this imply for the future?

Thomas Santana: Right now, I think we’re at a great place. I think the only thing that’s really stopping us from growth is the lack of access to mid-size venues or locally owned venues that aren’t pubs or freakin’ dive bars, you know? [Venues that aren’t] as mainstream as Royale, we want venues for the local scene. I think if that starts to pop up, Boston is going to have a really big explosion. I will say though, the pot is boiling. We’re ready to grow. We’ve had artists from around the world hear about us and want to debut with us, so it’s been beautiful. Boston has been solely on the map, and [now] it’s only going to go further and further. And, the great thing is – we’re still a small community.

Hidden beneath murky jazz, between the cracks of funk and among the realms of rock lies jam music. Playing with heavy improvisation and the fusion of genres, jam bands create outlandish live music experiences for their audiences. Jam sets typically consist of a handful of songs that range from 5 to 30 minutes, starting as any song would–with verses and a hook–but then transitioning into what stretches the music to its long form: the jam. These jams are often the highlights of jam band concerts and are what keep the fans coming back for more.

In 1965, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Ron McKernan, Phil Lesh and Bill Kreutzmann banded together to create the music group known today as The Grateful Dead. In 1967, the band released their self-titled first album, Grateful Dead, and by the end of the 1960s, they had quickly assembled a dedicated fanbase of “Deadheads.” The Dead was the true jumping point for most, if not all, jam bands to come.

Following the success of The Dead, jam bands started popping up around the country. Phish, who share similar success and influence as The Dead, emerged in the 1990s, and fans of the jam band genre flocked towards them. The String Cheese Incident, King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard, MOE, Umphrey’s McGee, and other popular jam bands also became prosperous through the growing interest in the genre and, following the unfortunate death of Jerry Garcia, they aimed to keep the iconic legacy going. “The jam scene has “definitely

changed a lot,” says Ewan Bourne, guitarist of Berklee-based jam band Jammwich, “Ever since Jerry Garcia died, I think that was like the king dying in the jam scene, kind of. And then all these other people are like, ‘Alright, now it’s our turn. We got to step it up.’”

One of the appeals of jam music is that all performances are unique. Because their music is improvisational in nature, it’s unlikely jam bands would wind up playing the same song twice, and when it does happen, it doesn’t always work out as well as it did the first time.

“We like to fall into this trap a lot recently, where like, oh man, there was one time where we went to this one chord sequence spontaneously, and it was awesome, so yeah, of course, we’re going to try that again this week…it might be okay, but if you do it two or three times, it’s kind of predictable,” says Brian O’Connell, vocalist and bassist of Massachusetts-based jam band Arukah. Predictability is not in the jam band handbook. The experimental nature is why the songs last as long as they do. “There’s a lot of times where we’re planning a song on the setlist that might say, you know, 10 minutes, but then it goes into like 20 minutes,” says Seth Gomez, guitarist of Boston-based jam band The Chops. Gomez says that this is a direct result of his band’s freeform, free-flowing sound that doesn’t stick to a set of rules.

Like most bands, jam bands record their music to put on streaming platforms and perform live. However, their studio music differs from their live performances because it is only a piece of what they have to offer. Sometimes they’ll put out live albums to try and capture the true essence of a live jam performance, but when it comes to playing their music on the radio, they have to shorten their songs to fit. Bands navigate this in different ways and vary how they make their music to keep the listening experience unique, even in a studio recording. Gomez says that recording songs in a studio is harder as a jam band, but his band makes the most of it by “adding a lot of different layers, different instruments and stuff that we can’t provide in the live setting..that way, it still has that unique quality where you’re gonna be surprised or, you know, continue listening, but it’s not like a live track where it’s just the four of us.”

How is it that, in the live setting, they can play these long songs without knowing what is coming next or going back to try again if they make a mistake? The answer is communication. “It’s a constant conversation, both visual and just in what you’re hearing, you know. We’re listening to each other play constantly,” says Brian Epstein, drummer of Arukah, “after you play a song or particular jam in a certain way for a little while, you know, you start to get into almost a groove on how to come out of it.” Dan Sienko, bassist and vocalist of Jammwich, also finds com-

munication to be at the root of their creative process. “It’s listening to each other. I feel like that goes along with just knowing our tendencies,” says Sienko, “The more we’ve jammed together, the more we know how each other plays and what we’re likely to do…if I know I want to do something, then I can kind of predict what might happen, how [the band] might react.”

Because the long-winded songs are so unpredictable, they create a unique concert experience every time. Jam bands have been part of the music scene for a while, so keeping the music fresh is essential.

“Something, for me, that I like about a Phish show is that the show just feels so singular… the setlist is always something never done before,” says Silas Gourley, guitarist of Jammwich, “I would hope that [our] show gives that particular audience that special onetime experience, and then we move on to the next thing, like on the improv way.”

Bands keep their music unpredictable by adding unique characteristics to it. “In addition to long jams and, you know, a lot of heavy improv, we also have really good songs,” Epstein says about Arukah’s music, “These guys write really good songs with intricate parts and also catchy melodies, and things that are approachable to people who may not otherwise be drawn to a band that will jam and improv for 25 minutes also.”

Arukah does this through both their songwriting and the songs that they choose to play in every set. “In terms of what I think what we’re trying to do more and more of, is to provide contrast, musical contrast throughout the show, throughout sets,” O’Connell says. By doing this, they make their songs memorable, which can’t always be said for every jam band. “I saw [some jambands] a couple of times and stuff, and they’re really good players, and they can get to certain zones, but not one song I even remotely remember,” says Dennis Angelo, guitarist and lead vocalist of Arukah, “I’m not trying to rip on jam bands or anything like that. These guys are great players; it’s just kind of like I either remember it or I don’t. I don’t necessarily remember a lot, but music, I do.” That’s the feeling they hope to create for their audiences, something to remember and take home with them after every show.

Jammwich is also no stranger to creating a memorable jam experience. “We’re also seeing a lot of the same combinations in the music that all the jam bands are playing,” says Bourne, “I feel like something that’s gonna start happening soon is, and I think we’re doing that already, but it’s incorporating different combinations of genres into jamming that most bands in the jam scene don’t use.” Jammwich is attempting to incorporate that contrast into their own music. Gourley expands, “Ewan, Owen, [Jammwich drummer] and I love the Grateful Dead, we love Phish and we like to speak that language at the same time, but Dan comes at it with the grunge side...I

would say, it helps kind of come at it from a different perspective for us. And with the writing too, it provides something a little bit more refreshing.”

The Chops exemplifies a band that is actively employing this combination of genre and style in their music to create unique experiences. “For us, I think the big difference is our sound is more so residential to 60s music. Kind of like [Jimi] Hendrix or Jefferson Airplane, but we also have a lot of inspiration from the 80s music, like Alan Parsons Project or even 80s [Pink] Floyd,” Gomez says. He finds that using inspiration from artists— other than Jerry Garcia or Phish—provides a fresh perspective on jam music. “I think that is one thing our audience and our fans really enjoy about us. Just the different sounds we bring,” Gomez says.

Along with the improvement of their music through constant time spent writing and playing together, the bands’ relationships as people also become stronger. “I always like to say that music is one of the great communicators, a universally understandable language,” says Sienko, “I feel like it’s just like another way for us to learn about each other. We just get better at hanging out through jamming. We get better at jamming through hanging out.” The members of Jammwich all connected at school on their shared enjoyment of bands like Phish, King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard and The Grateful Dead when they met at Berklee. From there, they decided to form their band, building on their shared

love of jam bands but also from each of their separate influences.

The Chops also connected early on through their love for jam bands. Though getting off to a rough start after navigating through COVID-19 restrictions, they eventually found each other through the musical grapevine. Gomez, however, knew that he wanted to push this band to be as unique as possible. “We were all into The Grateful Dead, Phish and other jam bands, but I didn’t want it to sound like that,” he says, “I really wanted to go back to that classic 60s sound with influence from like modern jam bands.” This unique approach is what allows the band to grow.

Similarly, Arukah has a shared love of the jam band scene, but it was not that that brought them together. After playing with the band New Motif, Angelo found O’Connell through their mutual friend. “I was all intimidated to meet him and stuff,” says Angelo, “you know, big bad bass player guy… but no, he was a really nice guy and it was the easiest thing to be in a room with him.” This relationship blossomed even further after Epstein joined the band. “We put in a lot of work, we spend a lot of hours and travel around and just, you know, doing that with other people, there’s camaraderie and kinship there,” O’Connell says.

Not only does the music they play build a relationship within their bands, but they aim to create the same joyful environment for

their audiences. “I definitely think giving people a nice unique experience really was one of the things that drew me to getting into jamming in the first place,” says Sienko.

“At a show, I feel like it’s one of the only times you can get that amount of people in a room and not fight with each other. People are just enjoying it, and I feel like everyone’s able to forget about, you know, whatever could be going south in their lives at the moment.” O’Connell emphasizes, “To play for just one person to have come up to you and sincerely have that look on their face like, ‘Dude, you blew my mind…you’re just hanging out here by the bar, like being cool, like a regular person and you know you melted their faces, there’s nothing more satisfying than that.” As Angelo says, Arukah hopes to be their audience’s “Joy Delivery Service.”

Every night of The Eras Tour, Taylor Swift plays 45 songs accompanied by meticulous choreography, costume changes and visuals, but it’s the two nightly surprise songs that really get people talking. Swift sticks to an identical set list each night until it’s time for the surprise songs. For many fans, these two songs are the highlight of the three and a half hour show. While planned moments onstage can garner attention and praise, it’s the more spontaneous moments that create real buzz and cultural significance. These are just a few of the most iconic extemporaneous live performance moments of all time:

Bob Dylan, 1965:

Bob Dylan’s prolific songwriting and iconic folk protest songs led him to be known as the voice of a generation, seeking political change and justice. His early folk work garnered wide critical and commercial acclaim before he delved into electric rock and pioneered the folk rock genre with his 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home. While the album was well received, Dylan’s set at the Newport Folk Festival of that year was controversial among festival-goers. The night before his set, Dylan heard about condescending remarks made by festival organizer, Alan Lomax, while introducing The Paul Butterfield Blues Band to the stage. Lomax had stated that the band was running late and referred to their music as “purely imitative.” Paul Butterfield’s band played with a fully amplified sound. After hearing these remarks, Dylan decided to switch from his typical acoustic set to playing electric. He felt that if the

festival wanted to keep electric music out, he’d be the one to bring it in. While it’s disputed how much booing there actually was, it’s safe to say that many traditionalist folk fans weren’t happy. The spontaneous decision to play with an amplified band shocked the audience and brought out strong feelings and opinions, both positive and negative. Isn’t that what music is all about?

The

Beatles, 1969:

On January 30th, 1969, The Beatles gave their final live performance on the rooftop of Apple Corps headquarters in central London. The set was planned only a few days before the performance, and it’s not clear whose idea it originally was. Audio engineer, Glyn Johns claims he thought of it while others present that night suggest it was John Lennon. While Lennon and Paul McCartney were excited about the idea, Ringo Starr and George Harrison were hesitant. Harrison had only recently agreed to come back to the band on the terms that they would record their new songs in Apple Corps headquarters, not knowing they’d be performing on the rooftop of that very building in a few short days. The set lasted a whole 42 minutes before the Metropolitan Police shut it down. Following the iconic impromptu performance, The Beatles then recorded the infamous album Abbey Road before Lennon left the band in September of 1969. Footage of the show can be found in the 1970 documentary film Let It Be.

Jimi Hendrix, 1969: Now known as one of the most famous record-

ings of the national anthem, Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the 1969 Woodstock festival blew away the entire country at the time of its performance. The festival embodied the ideals of peace and love, with its attendees primarily being the decade’s anti-establishment youth. Transitioning from Hendrix’s well known song, “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” he segued into his own electric guitar interpretation of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Hendrix’s performance was widely received as a form of protest against the Vietnam War given the rise of the peace movement within the counterculture. However, Hendrix denied having any political intentions with his performance, later asserting that his interpretation was improvised. When asked by Dick Cavett about the moment, Hendrix stated, “all I did was play it.” This instance of musical expression has gone down in history as one of the most iconic live performances of all time, and the moment was revolutionary regardless of Hendrix’s intentions.

Jay-Z, 2008:

When American rapper, Jay-Z was announced as the headliner for Glastonbury Music Festival in 2008, Oasis member, Noel Gallagher made headlines for his snide remarks regarding the rapper’s upcoming performance. Gallagher, being a former Glastonbury headliner himself, asserted that “people [weren’t] going to go” to the festival with a hip-hop artist at its forefront. This, of course, turned out not to be the case. To open his set, Jay-Z sang “Wonderwall,” Oasis’ biggest hit. To add

insult to injury, Jay-Z didn’t seem to know most of the lyrics to “Wonderwall” during the performance, letting the audience do the heavy lifting for Gallagher and the band’s song. Jay-Z used the song to transition into his own hit, “99 Problems.” This is a legendary moment in pop culture history, made evident by the clip resurgence on TikTok in the last year. His young fans who missed the original moment have heralded Jay-Z for his trolling.

Beyonce, 2013:

Beyoncé has been widely praised as one of the greatest live performers of all time for her stunning vocals and precise choreography. At the 2013 Super Bowl, Beyoncé and Bruno Mars joined Coldplay for their halftime show. During a dance battle between Beyoncé and Mars, the former lost her balance and almost fell, but quite literally bounced back and continued her otherwise nearly perfect performance. Beyoncé has always been praised for her dance skills, but it was this moment, where she made a mistake, that fans applauded her choreography the most – because of her impressive ability to quickly recover. The moment probably isn’t Beyoncé’s favorite, but it proved to fans that she is still human… just a better and more talented human than the rest of us.

Sabrina Carpenter, 2023: In 2021, Olivia Rodrigo dropped “drivers license.” The lyrics of the song hinted toward a love triangle between Rodrigo and two fellow ex-Disney actor-musicians, Joshua Bassett

and Sabrina Carpenter. This release spurred an overwhelming amount of tabloid gossip and social media speculation regarding the three up-and-coming stars. Rodrigo’s career soared as the protagonist of this love triangle, while Bassett and Carpenter were painted as villains. Carpenter’s music up until this point had been restricted by the tight constraints of her Disney contract; she was still releasing music under Disney’s Hollywood Records. Rodrigo, on the other hand, had a number one hit in 2020 that instantly shot her out of the Disney bubble. The two were constantly compared, and Carpenter was torn down for a lack of vulnerability and personality in her public persona – two traits Rodrigo was commended for.

Carpenter’s album, emails i can’t send was her first full body of work released under her new label. It included the song “Nonsense,” which she performed with a different outro every night of tour, and now, as an opener for Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour. The outros have shown audiences a glimpse of Carpenter’s unfiltered identity with fun, sexually suggestive lyrics that she comes up with on the spot. For her Philadelphia show, she sang, “this crowd is giving me all the endorphins / I wish someone would rearrange my organs / Philly is the city I was born in.” These lyric changes have gone viral on TikTok and exposed Carpenter’s bubbly personality to a wider audience. The fun tradition on her tour has skyrocketed Carpenter’s career and the public opinion has shifted in her favor. Because of these spontaneous live moments, she

is no longer seen as an evil Olivia Rodrigo counterpart, but instead is more widely respected as an artist and individual.

These improved moments and last-minute decisions have helped define these artists careers. Even someone with such meticulous choreography as Beyoncé can’t ensure that everything will go as planned, but this is the beauty of live performance. Seeing these artists’ vulnerability to expression of their beliefs onstage is what makes these moments significant to both pop culture and their long-standing legacies.

Visual by Rocio Sola Pardo and Christina Casper

Great writers are always something else.

Winter break of my junior year, I decided I needed something to take me away from the notebook or keyboard after being a self-proclaimed writer since I was 10 years old. Something that would expand my creative palate in an exciting and completely unpredictable way. Something that wasn’t writing; something more than a hobby, but less than a career.

Flannery O’Connor put it best in her book Mystery and Manners, in which she expands on this idea by talking about painting:

I know a good many fiction writers who paint, not because they’re any good at painting, but because it helps their writing. It forces them to look at things. Fiction writing is very seldom a matter of saying things; it is a matter of showing things…Any discipline can help your writing: logic, mathematics, theology, and of course and particularly drawing. Anything that helps you to see, anything that makes you look.

What would my “something else” be? I didn’t have a clue on where to start until one night during this winter break, my boyfriend of two years, Seth, invited me along to a jam session at his friend Colin’s house. I agreed, and we went. While they played, I sat at the drum set behind them, marveling at Seth while

he charismatically played his favorite Grateful Dead songs; “Fire On the Mountain,” “Help on the Way / Slipknot!” and “Morning Dew.” After about an hour of watching them play, Seth asked me if I wanted to hop on the bass and play with them. I have no formal experience playing any sort of string instrument, but to my own surprise, I say yes.

I began to play with them, and almost instantly, I felt a sensation I hadn’t felt since the years I spent learning piano at a young age from a woman named Miss Nina Raposo at her home in Westport, Massachusetts. I gained the ability to play almost any song by ear, and over time, I developed a knack for true rhythm.

Having a bass in my hands was a burst of excitement and passion I never thought I’d feel. The more I played, the better I felt. The cooler I felt. I played the bass on their rendition of Pink Floyd’s “Breathe (In The Air),” and watched as they both were in awe, shocked at how I was even able to keep up with their tempo on my first try.

Colin said, “Holy shit, Nina. How did you do that so fast? If I didn’t know you, I’d have thought you’d been playing the bass for months. You should seriously consider taking up the bass. A knack for a rhythm like that doesn’t happen often.” Seth and I looked at each other, giggling and smiling, because we knew this would be the start of something great.

Soon after that night, Seth gave me his black bass guitar with a beautiful leather strap with smiling suns on it. He was over the moon. He said, “You should write music,” as if my skills are interchangeable. There’s pressure in “should.” Is there a difference between writing an essay and writing a song? A, B, C, D — Do, Re, Mi. Words tumble out of my fingertips as if they were pre-packaged and sealed. I’m committed to writing as a way of life, so why not try a new medium?

I’ve been playing bass for a month now, and I’m absolutely loving it. I’ve learned how to play classic songs with killer bass riffs. Some of my favorites have been “Seven Nation Army” by The White Stripes, “Stand By Me” by Ben E. King, “Psycho Killer” by The Talking Heads, “Some” by Steve Lacy and “Another One Bites The Dust” by Queen.

I didn’t expect taking up an instrument to change my identity as a writer at all. But as I play more often, the connections between music and writing have begun to emerge. Playing the bass has opened my mind to a new way for me to manifest my creativity. Music and writing have always gone hand in hand in my mind, never failing to gloriously complement each other in melody and harmony. Every sentence is a song on paper.