HOME COMING

Thank you, reader.

I believe in music and the communities it builds. These two forces are what makes Five Cent work, and this issue, “Homecoming,” shows that in a special way. The twelve pieces that shape this issue are personal and open; reading them led me to reflect on what molds my own taste. However, this issue holds more than the written pieces: the graphics add a vibrant, new layer to every story, breathing life into the homecoming party.

Without Sophie, none of this would be possible. Her dedication, organization, and commitment are inspiring. From a hectic hiring week to the first issue of the year, “Homecoming” has become something beautiful, and I am so excited for you to experience it.

“Homecoming” reflects on family, friendship, heritage, culture, and the thread that binds them all: music. It is a celebration of the role music plays in our lives, and at points, a critique of how modernity has enveloped the culture around music. There is a nostalgic drive in our writers and designers that breathes through this issue. I think it’s timely.

Perhaps most importantly, “Homecoming” would be nothing without you. I hope you find the time to sit back and read, laugh, cry, learn, listen, and indulge in pieces that connect us to Boston, to music, and to ourselves. From copy edits to color choices, this is a piece primed and ready for reading.

Music is something to experience together. It takes a team to put together Five Cent, and a lot of music lovers to enjoy it. So, thank you for being a part of this journey. Take a step through the pages, open your eyes, and enjoy “Homecoming.”

Welcome,

Gavin Miller

Hello reader!

What you hold in your hands is the culmination of nearly two months of hard work, anxious Slack messages, and learning InDesign from the ground up.

“Homecoming,” to me, is more important now than it perhaps ever has been. It is vital to stick with your roots in times of trouble, and to reflect on what brought us to this very moment in time so we can move forward as one. It is our backstories that make us stronger together — in life as much as in music. This is what we are hoping to bring to the table with “Homecoming.”

Thank you to our incredible print team, without whom this issue would still be a nice idea in our heads. From our editorial to our creative team, everyone gave this project 110%, and I am so grateful for their time and dedication. Thank you to our writers for lending us their moving, and often quite vulnerable, words. I promise we will take the utmost care of them.

Thank you, most importantly, to Gavin, who helped bring me back down to Earth many times, assuring me that this mag will get done despite my neuroses — and, clearly, he was right! I think we have built something very beautiful together, and I am elated to be able to share it with all of you now.

We built this for you, dear reader, and I sincerely hope you enjoy. Sit back, relax, and step into our “Homecoming.”

Love always, Sophie

Hartstein

our team!

Executive

Co-Editor-in-Chief - Sophie Hartstein

Co-Editor-in-Chief - Gavin Miller

Creative Director - Rebecca Calvar

Managing Editor - Emma O’Keefe

Head Online Director - Sydney Johnson

Assistant Online Editor - Marianna Orozco

Photo Coordinator - Rose Luczaj

Assistant Photo Coordinator - Rocío Solá Pardo

Playlist Coordinator - Norah Lesperance

Social Media Manager - Mia Rodriguez

Editorial

General Editors

Dana Albala

Taylor Blose

Nina Fauci

Rachel Hackam

Olivia Lindquist

Delaney Roberts

DEI Editors

Shannon Cullen

Kalyn Thompson

Copyeditors

Penelope Alevrontas

Georgia Decker

Grace Grauwiler

James Hollander

Emie McAthie

Marianna Orozco

Alison Sincebaugh

Creative

Visual Artists

Liam Alexe

Nicole Armstrong

Hazel Armstrong-McEvoy

Rebecca Calvar

Isabelle Galgano

Matthias Gat

Rose Luczaj

Ha Pham

Hollie Raposo

our five cents:

Quilted: A Love Letter to Record Shops by Sachi Andrade // 7

Just What I Needed: How School of Rock Changed My Life by Rose Luczaj // 11

What is Sampling? by Emma O’Keefe // 15

Diva Cup: Saviors of Sincerity by Jagger van Vliet // 19

A Homecoming I Can Count On by Olivia Lindquist // 25

Plucking Feathers at the Party: A Critique of Modern Concert Culture by Rynn Dragomirov // 29

Come Home: Get in the Pit by Gavin Miller // 37

Poisoned Nostalgia by Jack Silver // 43

Electronic Resurgence Parts I and II by Sachi Andrade and Audrey DuMurias // 49

Que Cante Mi Gente by Izzie Claudio // 55

How to Name a Persian Daughter by Taraneh Moeini // 61

Back to Boston by Emma O’Keefe // 67

by Sachi Andrade

visualbyLiamAlexe

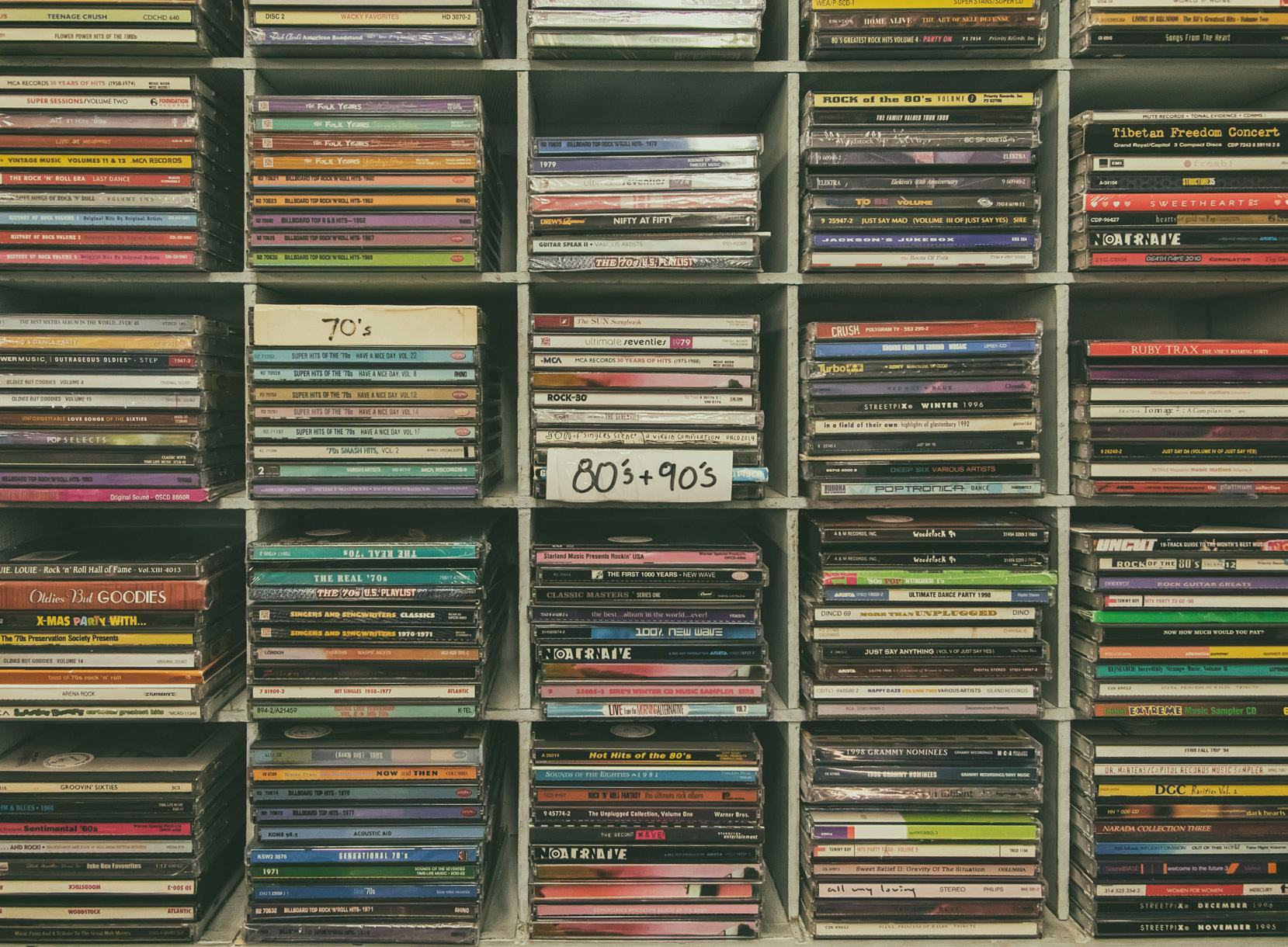

In the current discourse of “third places” and whether or not Gen Z has any, there is a space that is often skipped: record shops. A third place is a space where one can meet and connect with other people, cultivating a sense of community. Libraries, coffee shops, gyms, clubs, and any social environment outside of the workplace are a few examples. One of the main points in the discourse of third places fading is the prevalence of the internet.

However, shopping for vinyl online is not comparable to going into a physical store. The tangibility of vinyl is one of its most distinct and valuable elements — it bridges the gaps between the five senses with an immersive experience. As you dig through a genre you’re familiar with, the turntable plays something you might have never heard before, and the smell of old vinyl brings a literal air of familiarity. Music is synonymous with home for many and bonds people from all walks of life, making these brick-and-mortar stores, in many ways, a home.

they transform into social spaces to discuss the recent happenings in music

Record stores are far beyond being a room with a bunch of piles of polyvinyl. They transform into social spaces to discuss the recent happenings in music, from concerts for well-known artists to smaller, more local musicians. Independent record stores contribute to uplifting the local music scene and provide an invitation to become more involved in the community outside of the store.

Or maybe community is built in-store, through a conversation about a rare avant-garde jazz press, or a moment to reminisce on the albums that have led you to listen to what you had chosen on a given day. Memory is

the thread and stitching of the quilt of record stores. It’s the writing on old records telling the story of the vinyl before it is brought to a new home.

Record shops also serve as sanctuaries for anyone interested in music: the casual listener, the rare collector, the audiophile, producers, and onwards. An incredibly important aspect of these stores is the individual culture crafted by owners, friends, and customers. It’s like a beautifully knit quilt: everyone adds a block continuously, creating a warm and welcoming atmosphere for all. Not only do these spaces retain a particular identity, they become woven into the cultural fabric of their location. Independent record shops also often become cultural centers, havens for groups to build community through music, especially as music is often cultural itself. The existence of these places are open invitations to explore sound while allowing us to also learn about one another through our differing relationships to music.

The miscellaneous items around the shop store the memories of its customers and staff. Though, every record store has its individual flair, and the commonality between them is the purpose of decor. These objects do more than just simply exist in the space: They add to the character and culture of said record store, and more blocks are knitted into the quilt.

Peppa Pig is chilling in one of the aisles of Looney Tunes Records in Allston. Upon inquiry about Peppa, the shop’s owner, Pat McGrath, said, “The sweet spot to listen to records is in front of Peppa the Pig, Peppa represents the sweet spot in the store … a landmark of the sweet spot.” Up in Beacon Hill, inside the glass case at the Music Research Library lies the mystical (ironic) safety-yellow bumper sticker that reads, “Keep Honking! I’m Listening to Alice Coltrane’s 1971 Meteoric Sensation ‘Universal Consciousness.’” The bumper sticker is one of the more niche items in the

store; it is a great conversation starter or something you chuckle to yourself about after seeing it. I did ask if it was on sale, but “It’s too ingrained in the DNA of this store to sell,” said co-owner Vasili Kochura. Another block in the quilt.

Vinyl has already been around, fallen in popularity, and is on the rise once again. Its wavering popularity also raises the question: If vinyl dies out with the younger generations, do these spaces die out? It’s highly unlikely, since the main driver for these shops is the sheer passion for sharing music, and some records you cannot find via streaming. Kochura had some insight on this, stating, “I think record stores will always be around because people will always be interested in the past; they tend to be a time capsule for certain eras.” With this, the record shop may be an immortal entity — a shared space that I hope will transcend time.

In the downtown area of Fairfield, Connecticut, nestled between a Subway sandwich shop and a local dry cleaners, is one of the most special places I’ve ever known. This two-story converted colonial is home to the local School of Rock; an oasis for the outcasts, a refuge for the rare, and a safe haven for everyone in between. Despite its conventional concealment, within its soundproofed walls lies a creative community unlike any other.

The original School of Rock was established in Philadelphia in 1998 by Paul Green as a music school, with the intention of educating artists of all ages about the history of rock and roll. It began franchising in 2004, and now has over 375 locations worldwide that teach guitar, bass, drums, vocals, and keyboards. Although each school operates in a slightly different way, they all have a lesson component and a performance program, allowing students the opportunity to improve their craft with one-on-one guidance, and play as part of a band on stage.

The first two programs that a student can enroll in — Little Wing and Rookies — begin at age 4, and teach children the fundamentals of music and rhythm while exposing them to some of rock’s most iconic names, like The Beatles and The Who. Students can then transition into Rock 101 from the ages of 8–18, which combines lessons and group rehearsals that culminate in a live performance three times a year. The shows cover songs by a variety of bands and genres every season, ranging from The Rolling Stones to southern rock to neo-soul.

Additionally, there are opportunities for students to elevate their gigging experience through the House Band and AllStars programs. The House Band admits kids and teens through an audition process and consists of approximately 20 of the top students at each School of Rock location. This group performs in neighboring towns and even travels out of state to play shows on a regular basis. The AllStars program is audition-based, but also reaches an international scale and only accepts the top 1 percent of School of Rock students worldwide. Once

selected, AllStars are divided into tour groups to play at venues such as Red Rocks Amphitheater and open for bands at festivals like Lollapalooza.

My School of Rock journey began when I was thirteen years old after I had quit classical piano lessons in search of a more vibrant music style. My dad, who grew up playing the drums and was part of the adult performance program at the School of Rock Fairfield, dragged me to one of the seasonal children’s shows. What I assumed would be a bore turned out to be the catalyst for the next six years of my life, and as the keyboardist in the Van Halen cover band began the introduction to “Jump” on the synthesizer, I was instantly hooked.

My first show was The Doors, an all-levels group that allowed me to show off my keyboard skills with songs like “Break on Through,” and even shred a nasty clarinet solo on “Touch Me” (we didn’t have any saxophonists in the band). Then, I worked my way up to my third show, Steely Dan, which was Music Director approval only, meaning I had to be granted special permission to enroll to cover such an advanced band. Playing classics such as “Peg” and “Reelin’ in the Years” alongside what I considered to be School of Rock Fairfield legends truly lit a fire within me. From that moment on, I was determined to become an AllStar one day.

Fast forward to a few years later; not only had I become a House Band member, but I was also a 2020 AllStar and employee at the School of Rock Fairfield before I had turned 18. Supervising the younger kids at rehearsals, substitute teaching keyboard lessons, and assisting with posting on social media for the school gave me a sense of purpose and pride, and I found myself more inspired and motivated than ever before.

As someone who had never felt that her artistic passions were fully understood at the local public high school, I looked forward to every afternoon spent at the School of Rock to reinvigorate my desire to create and initiate positive change. The School of Rock Fairfield is where I

met my best friends and closest mentors. It’s also where I fell in love for the first time — and, subsequently, experienced my first heartbreak. I learned discipline and dedication, confidence and leadership, and played on massive stages with an even bigger smile on my face because I was doing so with the people I cared about most.

On the evening of my high school graduation in 2021, I didn’t join my school friends for photos at the beach or prepare a speech for my classmates. Instead, I stopped by the School of Rock Fairfield in my cap and gown to take a photo with the teachers who supported me through the roller coaster ride that high school had been. The last time they saw me before I left for school, my coworkers and instructors gave me a card full of handwritten messages with two watermelon Red Bulls and a small bouquet of roses. I cried like a baby, but knew that this would be far from my last time seeing these people.

Now every time I go home for a holiday, I visit the School of Rock Fairfield. I sit in on a song, or just catch up with familiar faces at the front desk. In such a fast-paced, divided world, it’s critical that we recognize the community staples such as the School of Rock Fairfield that help bring together children and adults from all walks of life under the unifying force of music. I attribute my best memories to my time at the School of Rock Fairfield, and I cannot wait to see how my favorite hometown haunt continues to change the lives of the local youth for years to come.

visual by Matthias Gat

Listen to the first thirty seconds of “Hung Up” by Madonna. Do you recognize that intro from somewhere other than her 2005 dance-pop hit? You might be familiar with the sound of that instrumental synth from ABBA’s 1979 disco hit “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight).” This is an example of sampling in music. Sampling is when an artist takes a piece of media, whether an instrumental or vocals, and reuses and recontextualizes it for their music. This is done more than you might think. Modern artists such as Kanye West, Pharrell Williams, and even Ariana Grande frequently use samples in their songs, showcasing the techniques’ continued relevance in contemporary music.

Sampling is foundational to hip-hop as we know it today. DJs popularized it in the ’70s and ’80s and took pieces of genres such as soul and funk songs to create new and infused compositions for Hip-hop artists. There isn’t a single artist to point to and say they invented the technique, but producers like Q-Tip (known for his work with A Tribe Called Quest), RZA (the leader of Wu-Tang Clan), and Adam Horovitz (a member of the Beastie Boys) are among some of the most famous hip-hop artists/ producers to popularize the technique.

Sampling became a standard of hip-hop culture in the ’80s, and was done without consequences. To sample a song legally today, you need permission from the songwriter, the publisher of the song, and the record label. However, it was standard back then to use samples without permission. Sampling another artist was a way for people to connect with a sound of another time or genre. It was widely perceived as a compliment to another artist to sample their music.

In the early ’90’s we saw the first historic music sampling lawsuit, which set the precedent for today’s use of sampling and the debate around whether sampling is considered stealing. In 1991, rapper and singer Biz Markie released “Alone Again” which sampled the instrumentals of “Alone Again (Naturally)” by Gilbert O’Sullivan. However, Markie did not have clearance from

O’Sullivan to use this sample. When Markie was sued for stealing from O’Sullivan, the judge ruled that Markie had to pay $250,000 in damages. The judge even referred Markie to criminal court for theft. Though the case never reached criminal court, the suggestion shows how demonized Markie was by the judge.

This case set the legal standard for sampling today. The case and the outcome are ironic, seeing as a Black man was sued for supposedly stealing a white man’s music, while white artists (The Beatles, Elvis, the list goes on) had been blatantly taking and profiting from Black artists without direct permission or legal consequences for decades by this point. The debate around whether sampling is stealing is inherently linked to race, as Black hip-hop artists are the ones who consistently reap the financial and legal damages. It’s important to question if the technique had been popularized by white artists, whether it would be labeled as stealing like it often is today.

Up until 2014, the GRAMMYs did not allow songs that used samples to be nominated for Song of the Year. This would inevitably prevent Black hiphop artists, who most often sampled in their songs, from winning the award.

This disparity raises critical questions about race, equity, and the power dynamics within the music industry. Up until 2014, the GRAMMYs did not allow songs that used samples to be nominated for Song of the Year. This would inevitably prevent Black hip-hop artists, who most often sampled in their songs, from winning the award. The exclusion and lack of credit given to Black artists in sampling is reflective of a larger issue of racism present in the music industry where Black artists aren’t given the credit they deserve.

Sampling in ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s hip-hop took from more obscure songs and media. Sounds and songs artists loved would be used in new and innovative ways. It wasn’t used as

a nostalgia bait tool like it’s often used nowadays. The question of whether sampling is used as a pull on people’s nostalgic heartstrings or a creative musical technique is debated, but there’s no straightforward answer.

Sampling has a reputation for being “lazy,” or copying another song. This isn’t how the technique originated or is supposed to be used, but sometimes sampling can be used less innovatively. Look at “Ice Ice Baby” by Vanilla Ice, which samples Queen’s “Under Pressure.” Not a lot of people have respect for that song or that artist, but it’s well-known because it uses Queen’s catchy instrumental. This is an example of nostalgia bait sampling, because the artist doesn’t add anything new or different to the elements of the famous song he uses.

Miley Cyrus’ “We Can’t Stop” is a song you likely didn’t know used sampling but actually does. “La Di Da Di” by Doug E. Fresh and Slick Rick is one of the most sampled songs of all time. You can hear it in the pre-chorus of Cyrus’ Bangerz hit when she sings, “So la-da-di-da-di, we like to party.” Here, an artist changes and recycles a piece of an old song’s lyrics in a very different way from the original. Nostalgia bait or innovation? Sampling can be either one, it depends on the artist’s reinterpretation or lack thereof.

Mark Ronson is one of the most worked with producers in pop music today. Ronson is known for producing hits from the likes of Amy Winehouse to Bruno Mars. In his TED Talk on sampling he states, “In music, we take something that we love and we build on it.” He describes sampling as a way to insert himself into a narrative of a song or piece of music he loves. Hip-hop artists have been taking the music they love and building on it for decades now through sampling, and pop artists are now catching up. Sampling is sometimes looked down upon, but, when used correctly, it’s an innovative and creative way for artists to take old sounds and make them completely new.

It’s another Friday night house show — low ceiling, stifling air, and a perfectly dismal headline act. So, this is the underground scene as it exists today. Playing host to a coterie of bands imitating other bands and music insisting desperately on its own importance, the scene may as well be asleep. What is the youth to do? Where are the saviors of sincerity? Simply put, who on Earth can kick the scene awake?

Enter: Diva Cup!

Formed only two years ago, this all-woman punk outfit has already smashed through the milestones that wellestablished bands still aspire for. They have gained a loyal following, produced scores of merch, mixed and mastered an entire album, and they have done it all in a blindingly authentic rage.

Now, as Diva Cup steadily joins our Zoom meeting, it becomes immediately apparent that this band is not defined by any barriers, much less time zones. Two Diva Cup members are presently abroad in Berlin — guitarist Maxx Goodman and drummer Maggie Kempen. “Everybody drinks beer here,” Kempen jokes, toasting her laptop camera. “They’ll just carry it on the street, and I felt like being German today.” The remaining members — lead singer Polly Torian and bassist Addy Harrison — join from Boulder, Colorado, where the band originated.

As a sidenote: Harrison joined the Zoom slightly late. Yet, without overstating it, nothing could have displayed Diva Cup’s unrelenting authenticity better.

“What’s up, girl!” Kempen exclaims, the moment a freshfaced Harrison appears on the screen.

“How’s Berlin?” Harrison asks at once.

“So good, mama. We miss you!”

Setting aside the performing and the music, Diva Cup instantly feels like nothing short of a family. Evident in every remark, there is a distinct warmth within the band. Even separated by an ocean, the members spent the time between questions catching up and joking as though they were all still together, rehearsing in person.

Born of an unlikely “right time, right place” meeting at Radio 1190, CU Boulder’s student radio station, Diva Cup has not wasted a single moment.

“I had met Polly a few times before,” says Goodman.

“And I knew Polly from a different show,” Kempen chimes in, “I literally ran into Polly and Maxx at the radio station and I was having a tough time, so Polly asked me, ‘Do you play any instruments?’ Obviously, I fibbed a little and told her, ‘Well, yeah, I’m a drummer.’”

I got so sick of the circle jerk in music of “Oh, I know this band,” or “I play jazz chords” . . . Nobody fucking cares. Just be who you want to be.

It would seem that this happenstance meeting occurred not a moment too soon. When asked about the state of Boulder’s underground scene, Torian delivers a resounding assertion: “It’s flopping!” Without Diva Cup, Torian paints a picture of the otherwise lukewarm scene, “It’s all just men with jazz masters, and they all have a fucking saxophone player, and they all have moustaches and beanies, and I just don’t fucking care.”

“I got so sick of the circle jerk in music of ‘Oh, I know this band,’ or ‘I play jazz chords’ … Nobody fucking cares. Just be who you want to be,” Kempen adds with another toast.

These last words speak volumes to Diva Cup’s raison d’être, as it were. The band, quite simply, doesn’t care what anyone thinks.

It should, then, come as no surprise that Diva Cup’s forthcoming album will be an unapologetic ode to everything the band stands for. Split into two EPs “divided by thematic concepts,” the full album will encompass both EPs, delivering fans a complete picture of Diva Cup in all its glory.

“As a little spoiler, if you’ve seen us live you will have heard all the songs,” Goodman explains, “It’s essentially our setlist from all the shows we’ve played.”

While videos of the band’s electric live performances do circulate across the internet, the EPs will contain fully mixed and mastered editions of the songs fans know and love.

Speaking on this process, Torian says, “We got [the album] produced at Mighty Fine Productions in Denver. Loren Dorland was our producer because we really wanted to work with a fellow woman on the project.”

“Working with women is important to us,” adds Kempen. “Or really just working with cool fucking people, honestly.”

Another eye-roll-inducing tendency within other bands is to safeguard the details of their future projects carefully. Here, Diva Cup couldn’t be bothered to waste time on anything less than complete transparency.

“I will leak all of our shit right now!” Kempen declares.

As it stands, the two EPs will be titled The Revenge of Sassy and The Rise of Sassy.

“Addy, you have to take the mic and explain that,” says Kempen.

“I had this childhood horse named Sassy,” Harrison explains. “Apparently, my grandma found her in a field in Kansas, where her mom had been struck by lightning. Sassy was still hanging around, trying to get her to wake up … And I think it was Maggie who basically said, ‘We’re actually not going to let this concept go.’”

Without fail, each member unashamedly encourages their fellow bandmates with a passion that comes from the shared belief in everything Diva Cup is.

“At the end of the day, even if we’re having a rehearsal and it’s really shitty and we’re all in bad moods, we all still showed up. At its core, that’s what keeps us going. Sometimes we’re all exhausted and are like, ‘Fuck this,’ and ‘Fuck each other,’ but the fact of the matter is we pulled up, and we’re all here for each other,” says Kempen.

This could not be more clear in every endeavor Diva Cup puts itself to. In particular, the band’s headlining at Boulder’s Fox Theater in June of 2024, posed the largest test to their combined talents — a test the band passed with flying colors, packing the venue and delivering another iconic Diva Cup performance. The event also marked the largest merch release from the band, entirely produced by the members themselves.

“We all put blood, sweat, and cum into that shit,” Kempen says. “We had Diva Cup shirts, pins, thongs.”

“And kazoos,” Torian chimes in.

Completely organic creativity suffuses itself throughout everything Diva Cup touches, extending even to their choices in collaboration. Their upcoming music video for the iconic single “Public Venmo Porn Girls” was shot by Kempen’s own sister. Visuals for the band’s album cover were designed by Ha Pham, a fellow artist

friend of Torian. Diva Cup acts much like a conductor, attracting artists and creatives into the “beautiful Diva Cup soup,” as Kempen phrases it.

Amidst a milieu of cheap copyists and pretentious wannabes, Diva Cup is the much-needed slap in the face. They are everything that music can once again stand for: a return; a homecoming to authentic, furious expression.

But no one could say it better than Kempen herself:

“Regardless of the songs or this next album, it’s about keeping the energy of, ‘Fuck you! We’re women, and we’re going to do whatever the fuck we want!’”

a homecoming

i can count on

by Olivia Lindquist

Home, for most people, is a place where one lives permanently. I live with a very different definition of home, though. For the first 14 years of my life, my dad was an active-duty member of the U.S. Air Force. He wasn’t a pilot or a weapons officer, but I still found his job cool enough. He spent twenty years as an aircraft mechanic specializing in C-17s and C-5s — those massive cargo planes that look like they shouldn’t be able to fly. He also had a brief stint as a maintenance production superintendent on training airplanes, but that was only for a few months at most. Either way, due to his mechanic position, he often worked nights and swing shifts. This meant he would leave for work around 2 p.m., before my sister and I got out of school, and be back any time between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m. Needless to say, I rarely saw him during the week. Due to the demands of his job, we moved frequently and, until he retired, I’d never lived in one spot for more than four years.

Home to me, and many other military brats, is “where the heart is,” as the saying goes. Home is where I find pieces of my dad when I can’t see him.

I grew up with long road trips. Whether we were driving across the country moving from one place to another, or just going between Las Vegas, Nevada and Spokane, Washington for summer break, music was a staple. My dad controlled the music while he drove, but the rest of the time we could pick what we wanted to listen to. I spent a lot of time playing the “Who Sings This?” game in my dad’s car. Many rounds included fun facts that I had been told a dozen times before, but that didn’t matter because it was something I could share with him. My favorite one is that Pearl Jam and Soundgarden are both from the Seattle area. My dad listens to a lot of Pearl Jam. The two songs he played most frequently were “Even Flow” and “Jeremy” — I think that second one is because his name is Jeremy.

His music taste has influenced mine more than I would like to admit sometimes. Every year we spent New Year’s Eve singing bad karaoke and watching videos about the top 10 songs of the ’90s and 2000s. “Baby Got Back” by Sir Mixa-Lot was a constant in our household even when I was too

young to know what it was about; because of him my greatest party trick from third through fifth grade was being able to rap the entire song. Other kids had “Can’t Hold Us” by Macklemore and Ryan Lewis, and while my dad and I enjoyed their music as well, we preferred “Baby Got Back.”

I still have intense flashbacks to pop hits countdowns, sparkling apple cider, and fireworks over the Las Vegas Strip every time I hear this song. We listened to a lot of AC/DC, Bon Jovi, Beastie Boys, and P!nk. I can remember singing “Highway to Hell” with him on the way to visit his work when we lived in Vegas and feeling the warmth of joy every time I got to say the H-E-doublehockey-sticks word that resulted in a fit of giggles. I remember singing “Wanted Dead or Alive” in Rock Band every other weekend with him, my mom, and my sister — sitting on our old, stained couch with pizza and soda and a complete lack of understanding regarding what the lyrics actually meant. I remember jamming out to “Fight For Your Right” by the Beastie Boys on our drive through the Colorado Rocky Mountains while it was pouring rain and I tried to not freak out about the elevation. The song’s upbeat rhythm and fast lyrics helped to ease my pounding heart every time I noticed how high up we were. I remember my dad instilling in me that P!nk was an icon, primarily with her song “Raise Your Glass” while driving to San Francisco when the roads were bare but I was nine and needed entertainment.

Comedy music was a regular in our household whenever someone was upset. Weird Al’s “The Saga Begins,” “Eat It,” “Fat,” and “White and Nerdy” were listened to at least biweekly. He also introduced me to The Lonely Island through the song “Jack Sparrow” because of my interest in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise. I was way too young to be listening to them, but “Jack Sparrow” wasn’t too explicit, so it was fine. Now, at 20 years old, I still have days where I listen to nothing but The Lonely Island and Weird Al. I’ve been able to share this music with my friends, finding joy in the goofiness of these lyrics. I’m even making plans to go see Weird Al on tour next July.

Needless to say, he’s influenced my music taste more than he probably knows. He introduced me to my favorite artist, Fall Out Boy, and through them I found my love of going to concerts with my dad. He took me to my first concert in 2018, which was Fall Out Boy’s Mania tour. Since then, I’ve seen Fall Out Boy twice more, Weezer twice, Green Day once, and dozens of other bands. He took me to Warped Tour in 2019 where we spent the weekend rocking out on the beach in Atlantic City to Blink-182, We The Kings, Bowling for Soup, and nearly 25 other bands.

When I went to my first solo concert in 2023, I took everything I learned from him to heart: Drink water, wait for traffic to clear out before leaving the venue, get your merchandise before the opener starts, and always wear earplugs. While that show was Big Time Rush and I went because I got cheap, nosebleed seating, I couldn’t help but be overwhelmed with how much his habits had rubbed off on me. Because of him, I can be present in these moments, knowing I’ve taken his recommendations to heart, and just exist with the music. Now every time I plan for a new concert I always include him, even if it’s not someone he would inherently enjoy, because he likes being able to spend time with me now after so many years of missing out.

Music has always been so intertwined with my relationship to my dad. It’s something that, even now that I’m in college, makes me feel at home. Even when I listen to a musical or a band I introduced him to, I still find myself remembering those hours in the car jamming out to Green Day and AC/DC. I still remember those nights singing along to Sir Mix-a-Lot and Bon Jovi, and watching Weird Al music videos like movies on the living room TV. Because of music, I can always have a piece of him with me. I can always count on that homecoming.

Scan this QR code and listen to Olivia’s homecoming playlist!

by Rebecca Calvar

visual

“I got a few rules tonight … Rule number two is, like … Look. I know New York crowds are cool and shit, I know there’s a lot of students here, a lot of you guys this is your first show and stuff. I’m not down with the being cool. You better have a motherfucking good time tonight … The whole point of this shit is to have a good time. No being cool, just having a good time. You feel me, New York?”

These were some of the first words spoken by Childish Gambino during his New World Tour debut in Brooklyn, NYC. Ascending from below the stage in a full-body robotic suit and mask, Gambino gave us a brief snippet of “H3@RT$ W3RE M3@NT T0 F7¥” from his newest album, Bando Stone and the New World, shortly after shedding the helmet and running down to greet fans lining the barricade. Now maskless and projected on the large screens inside the Barclays Center, Gambino connected with the audience face to face — “You better have a good fucking time,” he stated.

Gambino’s New World Tour in August was one of the first concerts I’d been to in over a year, which was out of character for me. I remember being 13 and always having upwards of five concerts under my belt in a given year. I was constantly on the hunt for tickets, always eager to see an artist live and goof around in a GA pit. It was never uncomfortable, and I never doubted that those around me were enjoying themselves. The experience simply felt different back then — a reality that seemed to shift once concerts reemerged post-quarantine.

I don’t know what it is, but concerts just don’t feel as fun anymore. I’m sure this has something to do with me getting older and shifting priorities, but even at shows for artists I’ve dreamt of seeing live my entire life — like Childish Gambino — I’ve started to notice that concert culture has taken a serious hit in recent years. Part of this is because it seems like nobody is having a good time. This, of course, is a generalization, but how else am I supposed to explain an almost motionless pit at a Childish Gambino concert?

Some concertgoers may be having an authentic experience, but the fact that a large majority of crowds don’t seem involved in the performance lays a huge wet blanket on live music. Despite urges for audiences to “have a motherfucking good time,” I don’t see the dancing, the level of excitement, the emotional investment that I once did at live performances. Concerts are supposed to be a collective experience; if we wanted to enjoy music alone, we’d stay home and only ever invest in high-quality sound systems. Part of the experience is enjoying music amongst a group of people who appreciate it with the same intensity you do. When this group seems like it doesn’t even want to be there, it makes it difficult to feel like you’re experiencing something special. If I could have more fun with this music alone, why should I pay so much money to see it live?

The cost of the average concert has risen exponentially

from $91.86 in

2019

to $122.84

for the top 100 music tours in 2023, before resales.

Well, it’s those same large sums of money we have to dish out for shows that tie into my first hypothesis. Tickets are harder and more expensive to buy than ever before. According to Pollstar, a global concert industry data publication, the cost of the average concert ticket has risen exponentially from $91.86 in 2019 to $122.84 for the top 100 music tours in 2023, before resales. On top of this, ticket resellers, or “scalpers” as Whizy Kim calls them in her Vox piece “The real reason it costs so much to go to a concert,” now make up a hefty chunk of presale lotteries and regular sales. There are infinite ways for resellers to gain a numeral advantage for buying out tickets, and little to no regulation for how they flip those tickets. According to Kim, while using bots to buy out tickets is illegal, “enforcement against the resellers who use them has been lax.”

A host of other issues are also contributing to the high-stakes nature of buying concert tickets. For one, the 2009 merger between Ticketmaster and Live Nation, a business venture that led to an antitrust lawsuit from the U.S. Department of Justice, has meant that for the last few years, a single company has dominated both a large percentage of ticket sales and most concert venues. Not only is it now more expensive than ever for us to buy tickets, but it’s also expensive for artists, who only see a small fraction of the sales they make unless they’re already doing well for themselves. Fees from online ticket companies have also risen dramatically, and consumer demand is either incredibly high or surprisingly low, leaving artists struggling to sell tickets when their success in the charts doesn’t translate into real life.

So, we’re left with two danger zones. The first is on the consumer’s end, where audiences become increasingly hard to impress. The reality is that when people pay so much money for shows, their standards become higher; they want a return on their investment, and whether or not the artists they see live up to that is subject to question. A lot of shows don’t feel worth it when you sacrifice an arm and a leg to attend them. So, consumers become more selective with the tickets they do buy, or they attend shows only to feel like they wasted money for a performance they weren’t crazy about. The second is on the performer’s end. Touring independently is incredibly expensive, but if you sign with a company like Live Nation to help out with costs, you’re left paying interest while they reap the benefits of both your ticket sales and the concession sales from all the venues you play. It’s much more difficult to put on a complex, pyrotechnicallyadvanced performance when you can barely pay to be on tour in the first place. Renaissance- and Eras-level shows are exclusive to those who have the means to afford them. There’s also been heavy criticism, especially in the hip-hop community, about the decreasing quality of performances in recent years; maybe artists just aren’t delivering on the same level as they once did. In either case, morale around concerts is dropping.

However, as far as we’ve come from paying $20 for Nirvana tickets in the ’90s, I don’t believe these money troubles are solely to blame. I think young people are more overwhelmed with performance anxiety — no pun intended — than ever before. We live in a culture concerned with image and surveillance, taking almost every aspect of the human experience and putting it on full blast online. As much as we want to believe that we’re immune to this, there’s something to be said about the way the internet often makes us feel like we’re being judged in real life.

Our generation is now in the unique position where being online involves curating a personality. Your Instagram isn’t just a collection of photos you like; it’s a character, a hyper-specific personal brand. Something I’ve struggled with is feeling a constant, imaginary pressure to prove to everyone exactly who I am because I must be as palatable in person as my online profile. I have to be interesting upon first glance; I need to prove to everyone that I like this artist or that style or that niche piece of media, all of which have easily identifiable names, à la corpcore or clean girl. Every day is a battle to not care about how others are perceiving you. When we start projecting that onto others, we all become part of the Indie-lympics. Everyone wants to have the best music taste and be the most unique, mysterious person in a room; to release that is to admit that you’re not some perfect model art student from NoCal who worships Elliott Smith. Young people yearn for community but are too concerned with the way they’re perceived to be vulnerable enough to find it. Attending certain shows is just a projection of how we want others to view us, and we’re more concerned with marketing our hobbies than genuinely enjoying them.

We can see this reflected in the decline of concert etiquette. Fewer and fewer people seem to know how to behave themselves at shows. Concertgoers will queue for hours to secure a spot at the front of a pit, but the merit of their six hours in line can be quickly overshadowed by someone behind them pushing their way

to the front. Crowds seem to lack respect for one another. Mosh pits feel like death traps, full of teenage boys who only care about capturing a perfect video of the action rather than looking out for those around them. Fans yell obscenities at their favorite artists in hopes of being noticed, or force internet jokes into the concert space, as we recently saw with Beabadoobee’s performance of “Girl Song” at Maryland Heights. We have seen that putting your own image above the well-being and enjoyment of those around you spoils the live music experience. Concerts should remind us of how powerful the collective human experience is, not the individual. Our preoccupation with “being cool” crushes this notion.

It seemed like many were [...] waiting for something to happen besides the music, though that was the entire reason we were there.

One experience that made these observations abundantly clear to me was Trixie Mattel’s Solid Pink Disco Pride 2024 kickoff party. If the name of the show doesn’t make it clear enough, it’s a big pink disco. Without dancing to complete the music, it’s a big sea of semi-drunk pink people; yet, the crowd was barely participating. For the life of me, I couldn’t understand what was stopping people from dancing at a DJ set, where the only thing to do is move your body. There’s no commentary, no standup, no buffers. Just you and the music. Even if people weren’t into the openers, the morale of the crowd was shockingly low for a Pride kickoff party — to which tickets weren’t that cheap either. It seemed like many were waiting for something that wouldn’t come; they were waiting for something to happen besides the music, though that was the entire reason we were there. The issue with that is, well, there’s nothing else we should be expecting. Maybe we’ve become so

overindulgent, so stuffed full of dopamine, that we struggle to recognize the merit of just live music. We’re waiting for some life-changing moment that will get turned into a viral TikTok, that others will watch and think, “Wow, I wish I got to experience that live.” What we struggle to recognize is that the music is this moment. The music only affects us as much as we allow it, and if we’re only ever searching for that one soulsatisfying event, we completely miss out on what’s actually in front of us.

What we need more than ever is a return to fun — a homecoming. We need to relearn how to enjoy ourselves again, to breathe new life into what has made live music so crucial to the human experience for so long. I urge all of us, myself included, to stop searching for something bigger. Take live performance for exactly what it is. Be attentive and present. Listen to the different instruments on stage; listen to the lyrics and their delivery, think about what emotional experience the artist is trying to create for you. Consider the hundreds of people it took to make this show happen and how their vision is playing out in front of you. Think about what those around you are feeling and how that makes you feel. Reflect on your experiences and purge the things that are burdening you between the crowd and the noise. Forget about being mysterious, forget about who you were before this moment. No more being cool; just having a good time.

Come Home: Get inthe Pit

by Gavin Miller

visual by Rebecca Calvar

On the outskirts of failing friendships and falling nations there’s a harbor of joy called The Pit. I’m not quite sure where it is, nor what exactly defines it. I know a handful of things about it, though: it’s the sweaty, cramped area before the stage; it’s what draws in the pinnacles of love and hate; it’s a space you’re in before you know it. Does this not sound like home?

What a conundrum it is to not feel at home with your friends. Home is ultimately the people we surround ourselves with, so when those people are there but never present, consistent but still uncaring, and familiar but often frigid, one is faced with a set of social contradictions. The loyalty of a lasting relationship combats the reality of things: that what was once dear to us has since departed.

This is when it’s time to find home again.

Entering my senior year of highschool I found increasing favor with baggier jeans, harsher hardcore, and more introverted practices. I also found decreasing favor with many of the friends who I assigned a subconscious loyalty to, those who had simply always been there. Such friends had been a house, but never a home to me. Confronting my newfound loneliness, I went house hunting for friend groups and was soon met with a set of six glorious words: “I’m going to that concert too!”

The newfound friend who spoke those words was Zach, and he didn’t know it then, but it meant the world that he would go to a hardcore show with me. All of my friends were too busy with the constant noise of high school spectacles — there was always something for them to complain about, to dramatize.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, roughly fifty years before my angsty teenage self was blessed by the joy of hardcore, there was a war bubbling in Northern Ireland, 1972. There were gunshots out of windows, bombs in the basements, pubs with invisible writing telling Protestants or Catholics not to enter, and a swarm of armed idiots roaming in from Britain (from your neighbor’s house too).

Here, stirring in the streets of Belfast, was the question of what defines home. If Northern Ireland isn’t Catholic, is it home? Even those with houses are made homeless, as bombs detonate every twenty minutes. Bloody Sundays don’t happen at home. There is the noise: the booms, the howls, the thunders of chaos in the backyard. Yet, beneath it all are the downstairs pubs, the raucous shows, and the haircuts only captured in old blurry photographs. Pain and anger are buried beneath Northern Irish cities, pushed into basement concerts.

There, joy is found.

There’s love when bodies are thrown against each other, buzzing and burning with energy and pleasure and feeling. Flying like birds with clipped wings, fleeing to take off, only to fall back against the concrete where you’re picked up and tossed again. You’re tossed again, picked up and tossed, only to help someone else up off the floor, a stranger, a friend. It is a cymbal, a rattle, a bang. Noise, unadulterated noise, complete in the mix between guttural yawps of pleasure (well, maybe occasionally some pain, but it’s all pleasure isn’t it?). For young Catholics and Protestants living through The Troubles, catharsis was found in a simple truth: they can dance through it together.

I was lost during my senior year of high school. The show that found me was a double feature: Soul Glo and Show Me The Body. Zach and I ran a little late, but still managed to enter the small Seattle basement venue before the show had begun. The walls were plain and the space was cramped. The stench of something indiscernible but unpleasant plagued the air; it rose like a thick, invisible fog. And we were there, me and a friend I had barely made, excited by the prospect of throwing ourselves into something new — physically tossing myself into a perceived danger. This is the closest to home one ever gets: a dangerous safety.

The screams of Pierce Jordan make my soul glow; the banjo twangs of Julian Cashwan Pratt show me how my body

can move. The wall of the crowd is indomitable in its potent noise against colossal speakers. And I am there, and I am smiling, and I am baptized in the joy across my face. There is so much to let go of, there always is. Yet in that tight venue, dancing against my years of insecure friendships, I found rest in the mosh pit.

Strict definitions place moshing as the direct child of the California hardcore and punk scene’s slam dancing, but footage from the UK rock scene of the late ’60s to early ’70s demonstrates the birth of the movement that would legitimize itself with rules and circles (the physical “mosh pits”), according to William Tsitsos in Rules of Rebellion. Where one draws the line on specific definitions matters very little to me; I can tell when I look at the smiles of those young Irish punks that they found the same thing I found beneath a collapsing foundation: home.

Even outside Belfast, in smaller seaside towns like Bangor, the Northern Irish felt the tension of rotting empathy during The Troubles. The punk scene was not only an escape, but the only place some folks had to bring their hate. Accounts from the time confirm that the clash of political ideology spilled out on the street, then back to the stage. Hector, a Northern Irish interviewee from Bangor, spoke to author and historian Fearghus Roulston on the effect of the punk scene on angry youngsters, saying the “Clash gigs were a bit like a riot set to music. Kinda all this aggression, kinda going forward, not anything in particular, but in the end you come out like fucking Buddha.”

This was in the late ’70s, where a new generation had been raised amidst the hatred and divide of The Troubles. Though, there can’t be a one-dimensional, fantastical view of punk as freeing because of this. What takes in hatred to drive it out still ultimately consumes it, leading one to the muggy history of skinheads. Even so, the punk scene’s growth shows that a joyous collection of punk bodies is meant for the purge of hatred, not an expansion of it.

Reflecting further on the interview with Hector, Fearghus Roulston wrote that “Being a punk […] meant existing outside of the sectarian architecture of the conflict.” The conflict in this excerpt is unnamed. It can be the newest imbecile in charge or the oldest law in the book, an argument with your husband or your parents’ divorce, the melting feeling of being alone or the yearning to feel more alone.

Or, it can be the dissolution of the friend group I held for as long as I could remember — the slow dissolve, marked by cracks and wear.

At the show with Zach, the music struck me to move my feet. There are rules of course: You pick up every stranger; you push and get pushed back; you build a human wall around the fallen (no matter who they are); you try to jump up (unless you want to be thrown); you can kick, but mark your space; fling your arms, but stay alert. These are the basics, but it’s all about care, about making it so everyone can create a home at once, together, in The Pit. The rules of The Pit are the new laws for the lawless, or, as Hector put it, “... wherever you were when you heard the police sirens [at the start of the song], you made for the dancefloor, running over tables.” The tension, the unresolvable teen contradictions, and the feuds with what it meant to be a friend; those were the police sirens ringing and ringing and ringing. I made for the dance floor my senior year of high school while screaming along to Soul Glo.

Those who get high on a past they never lived may say we’ve lost it. The sacred spaces are gone. The police moved in. The journalists wouldn’t shut their pie holes. The scene committed suicide after Bush. They’ll say that we survive off of nostalgic remnants. They say a lot, and it’s easy to believe it.

Surely, The Troubles have ended, but the cracks of the local nation remain. It’s in the two recessions since I was born, increasing class tension (both globally and domestically); the never-ending American project

of foreign war launched before I was born. All the moments I’m too young to remember and too old to forget. It’s in the spirit of Rock Against Bush, the impending doom of inevitable changes — constant, unending, karmic changes. Of course we laugh now, looking back, at the bodies slammed against each other in those Irish pubs, thinking it impossible that such movements would fix anything. The sling and fling of bodies against concrete walls, flesh pressing up against scarred flesh, Catholics and Protestants laughing and laughing and laughing in the same space. At the time, it was a miraculous space in the most literal sense; a joy buried beneath fury. But then I was there, in the middle of the gig, a religious experiment used on the political extremities, especially in areas like D.C. and California through the ’80s. Once I was there, I could only think we hadn’t lost anything; this was still home. As it had been, and will forever be. The Pit remains a haven.

Zach and I drove home that night. It was a rare clear night for a Seattle winter. We stopped at Taco Bell, we laughed about the opener’s hectic sound issues, we laughed harder about the bruises we’d endured in the pit, we talked about new releases and shows and all of the music we wanted to make. Good conversation had eluded me for so long, good friends felt like a foreign mystery. We were there just an hour before, long hair shaking between people with some of the worst tattoos I’d ever seen. Regardless, we drove East down Interstate 90 that night, going 70, singing all the songs we’d just belted, even though our voices were hoarse.

When people are lost, they go home. From Belfast in the 1970s to backyards in Allston, the spirit of moshing is finding home where the people are, in between squished bodies, singing the same song, louder and louder and louder. Come on, come home: get in the pit.

visual by Rebecca Calvar

“The seasons go so fast Thinking that this one was gonna last Maybe the question was too much to ask”

- Adrianne Lenker

on “Sadness As A Gift”

This won’t last forever. One decade will slip to the next, and soon middle age will greet even the youngest of us with welcoming, out-of-touch arms. When tomorrow’s teenagers look back on our era, the picture will be inevitably incomplete. The complexities of our generation will be paved over by a clear, easily marketable aesthetic that can be repurposed and sold in T-shirts and coffee mugs. Endless trends, artists, and albums will be forgotten and omitted in the larger scheme of history — replaced by a grand amalgamation that corporate entities will call “2020s music.” And if these entities are the army that flatten culture, nostalgia is their weapon of choice.

A longing for the past, whether experienced or not, is not inherently harmful. Appreciating and examining the cultural markers of a particular time is a fantastic way to expand one’s artistic horizons and knowledge in general. But when a company’s sole objective is to profit off of this longing, it leads to products entirely devoid of authenticity and artistry. Whether it is a cliché, overproduced biopic about rock stars from the ’70s, or brand new artists that sound and dress practically identical to older legends, the commodification of nostalgia is utterly poisonous. To put it bluntly: Why would a large record company care if an artist’s music is authentic if that artist is successfully capitalizing on our nostalgia?

To be an authentic artist in a genre with a long, respected history is a delicate tightrope act. Their music must not stray too far from the confines of the genre, but it also cannot merely mimic their predecessors. The artist may face massive backlash for defying these expectations, especially if the genre has previously been dominated by a single perspective or demographic. Studio albums Bright Future by Adrianne Lenker and

Manning Fireworks by MJ Lenderman were released this year, and both manage to walk that line. They capture the essence of their respective genres without coming across as retro, or, more specifically, using nostalgia as a crutch.

Lenker and Lenderman stand independently as artists, yet they still proudly display their influences. While these albums share a stripped-back, spontaneous atmosphere, the two sound vastly different. Lenker’s sincere, intimate indie-folk recalls artists such as Elliott Smith, The Microphones, and early Joni Mitchell. Lenderman’s sardonic, scrappy alt-country brings to mind artists such as Pavement, The Silver Jews, and, on occasion, Songs: Ohia. Lenker may leave a genuine laugh at the end of her recording, but she means every word that came before it. Lenderman, on the other hand, will sing wholeheartedly about sitting under a “half-mast McDonald’s flag” and being “up too late with Guitar Hero”.

On these albums, the songs sound as though they have always been written -- they were simply waiting for someone to sing them to life.

What separates the two on the surface, however, only draws them closer in their depths. Lenker and Lenderman each have the rare ability to create something immediately breathtaking. On these albums, the songs sound as though they have always been written — they were simply waiting for someone to sing them to life. These are songs that are crafted thoughtfully and lovingly — the perfect antidote to the music industry’s greed and unoriginality. Even the lyrics are deceptively simple, with both artists avoiding cliches as well as overly convoluted metaphors. When Lenker confesses, “I feel God here and there / People tell me it’s everywhere”

she might as well be an ancient Greek philosopher. When Lenderman plainly states, “It falls apart / We all got work to do,” it sounds like a mission from a slacker higher power.

On these albums no one is attempting to relive the glory days or prove that great music is not dead. Lenker and Lenderman are not shackled by their genre’s intimidating pasts; instead, they focus on the uncertain future ahead. “This whole world is dying / Don’t it seem like a good time for swimming / Before all the water disappears?” Lenker sings on “Donut Seam,” an oddly sweet tune about the end of times. Lenker’s aim is not to romanticize all that came before, but rather to focus on the lovely, fleeting present. There is a tenderness embedded in every moment of her songs that sets the soul at ease. When Lenker does choose to evoke nostalgia (like on her opening track “Real House”), it sounds natural and true to her lived experiences. Lenker never shies away from her heartbreak or her fear to make her songs more marketable — she embraces them like they were old friends.

Lenderman is slightly less gentle in his approach, with songs like “Wristwatch” capturing the plight of modern loneliness within an undeniable earworm. The wailing guitars in the first 20 seconds are enough to send chills crawling down the spine, but Lenderman does not stop there. He croons about a “wristwatch that’s a compass and a cell phone,” and a “wristwatch that tells me you’re all alone.” His message rings clear: Our possessions are not enough to replace an emptiness inside. Corporations want to capitalize on our discontent by selling a picturesque version of the past, but Lenderman stares directly into the abyss. In an age where music and technology seem more watered down and disposable than ever, songs like “Wristwatch” simultaneously fuel frustration and offer a glimmer of hope.

Adrianne Lenker’s Bright Future and MJ Lenderman’s Manning Fireworks are staggering works of art on their

own, and being surrounded by countless artists trying to cash in on nostalgia makes them truly stand out in the crowd. Of course, such artists are not solely to blame. After all, it is far easier for most people to reminisce about simpler times (as if there ever were such a thing) than it is for them to face the unknown that lies ahead. It takes patience, thoughtfulness, and even bravery to look unflinchingly at the present and eagerly into the future. Music is often an escape from reality, and forcing listeners to confront the complexities of life is not always received well. Still, the greatest of songwriters can challenge listeners without alienating them. Adrianne Lenker and MJ Lenderman are not saviors of music by any means, but this year they have released remarkable albums that compel their listeners to examine their place in the world today. Two albums that sit proudly in the canon of their predecessors, without shamelessly mimicking or exploiting them. Albums like these remind us that art is not a rearview mirror but a highway, one that stretches endlessly and magnificently forward.

Year of the electronic sound

2010

written by

Audrey DuMurias Sachi Andrade

visual by Hazel Armstrong-McEvoy

Part I

By Audrey DuMurias

What every generation thinks of when they hear the words “pop music” is arguably varying, as pop is simply short for “popular.” Our parents might recognize artists like Kate Bush or ABBA as a pop sound, while Gen Z thinks of that as “’70s and ’80s” music. When I think of pop, it brings me back to my roots. The songs I would hear on the radio in the car while going to elementary school. Songs by Justin Bieber, Katy Perry, or Kesha, for example. So, what does the next generation consider “pop music,” and how is it different from what Generation Z grew up with? Well, I’m here to let you know, and the answer may surprise you. It can be argued that electronic music with an EDM/club vibe has become the younger generation’s pop standard today.

It feels impossible to discuss club sounds and electropop’s rise in listeners without mentioning Charli XCX’s Brat album. While the album was released early summer of 2024, it has only progressed in infesting the minds of teens. I see her everywhere, hear her everywhere, and feel the influence of her music everywhere. Charli XCX had a few hits in the early 2010s, and seemingly dropped off the face of mainstream pop music. Little did we know, she had been conjuring, anticipating, and perfecting her new persona, personal sound, and marketing techniques to turn herself into one of the top IT Girls of the next generation of music lovers. While there is no way to know how she became who she is today from what she used to be 10 years ago, (think “Fancy” by Iggy Azalea), it is obvious that she is a current trailblazer for the new era of pop sounds.

Several things can be credited to Charli XCX and the sound of electronic/club music paving its path to popularity. Perhaps it’s a change in party culture, a technological advance in the music industry, or the societal need for music created purely based on vibes rather than lyrics

as an escape from the real world. All are undoubtedly contributors to this new wave of pop, but I, as well as most likely many others, would testify to the reason being TikTok, and social media culture in general. Brat was not the only music that found its audience on the popular social platform. Almost every newly popular artist found themselves the target of TikTok viral sounds and trends. A short snippet of the catchiest part of a song blowing up on everyone’s phone, causing people to search for the song, and eventually the artist. This pattern of trending music has been recognized by the industry, and has been going on for quite some time now. Marketing professionals have analyzed what exactly it is about viral clips of tracks that make them so popular — a consistent and reliable sound, for example: energetic, upbeat, club, and electronic party music.

a new generation has begun to recognize the appeal of this modern pop style, and many artists have scrambled to keep up with the changing trends

A new generation has begun to recognize the appeal of this modern pop style, and many artists have scrambled to keep up with the changing trends. Besides Charli XCX’s shift in sound, Troye Sivan and Tate McRae are great examples of this shift. Troye was previously known for slower, more reflective and somber tracks that felt deep and personal. While his newer album is also personal, it features a much more computer-generated sound with a huge amp-up in energy. Of course, some of his past songs were energetic, and all of his new songs aren’t just electro-pop dance music. From 2016’s Blue Neighbourhood album to 2023’s Something to Give Each Other, the tonal shift in Troye’s music is glaringly obvious.

As for Tate McRae, she found YouTube fame from an original song titled “One Day,” accompanied by piano in 2017. For years, she arguably had a hard time breaking into the pop scene, until a song of hers went viral on TikTok for being upbeat and catchy. She has collaborated with DJs like Tiesto for their song “10:35.” “10:35” is one of Tiesto’s most popular songs from his 2023 album DRIVE, which also features Charli XCX.

With this new age of pop music turning away from that nostalgic 2010s sound we all know and love, it makes us think about the impact of electronic music and its sneaky importance for the entirety of the music industry. Pop music’s recent change is only a fraction of a testament to the influence that the electronic resurgence is having on the constantly progressing music industry. Sachi Andrade has graciously given us her insight into another way this electronic upheaval is changing the scene.

Part II

By Sachi Andrade

In some corners of the internet, the sound of postrage has been all the rage. Rage is a subgenre of trap, primarily pioneered by the tail-end of the golden era of SoundCloud rap from 2014–2018. Artists such as Lil Uzi Vert, XXXTentacion, Trippie Redd, and Playboi Carti are major influences. As music is ever-changing, we are entering an era of “post-rage.” Artists most associated with this edgier, electronic sound are artists on Playboi Carti’s record label, Opium. Outside of this label, artists such as Lancey Foux, Dom Corleo, Molly Santana, Yeat, Nettspend, and many more are contributors to this sound. One of the defining elements of post-rage is what it derives from EDM and other subgenres of electronic music, cultivating a hybrid genre that doesn’t stray from its trap roots. This more experimental sound has also brought interesting collaborations and projects to the forefront.

In 2023, Lil Uzi Vert released Pink Tape, one of their most controversial projects. Containing collaborations with Bring Me The Horizon, Snow Strippers, and BABYMETAL, the project was a conglomeration of sounds that meshed J-rock, electropop, and the distinct rage sound that made Uzi a staple in the scene. It was different. Pink Tape was met with a lot of criticism; its reception was similar to Playboi Carti’s Whole Lotta Red, released three years prior. Whole Lotta Red, now considered a milestone in the evolution of the rage genre and the transition to post-rage, set the bar for this new sound. The electronic elements of this project were undeniably present, especially on “ILoveUIHateU” with a chiptune style. Chiptune is essentially 8-bit music, using the same synthesizers and generators used for old arcade and console video games, producing a highly digitized sound. This chiptune sound can also be found later in Destroy Lonely’s “by the pound,” or Ken Carson’s “Teen

X Babe.” Both artists are signed to the Opium label.

Ken Carson ventured out on his Chaos World Tour this summer, having Los Angeles-based 2hollis as an opener during the U.S. leg. 2hollis’ 2024 singles, “crush” and “trauma” are both tracks hybrids of electropop, rage, and EDM. Not only did this introduce hyperpop to a new audience, but this can also be representative of the state of rage — moving to a more electronic sound. 808s are now leaning more toward electronic than hip-hop. It’s moving from the raves to the mosh pits of Ken Carson concerts — then moving to TikTok, showcasing footage from these concerts. The power the internet holds in popularizing music is unmatched. TikTok sounds become trends and spread, introducing hundreds of thousands of users to different genres.

There is a considerable, recent shift toward more electronic music. For example, Imogen Heap’s airy “Just For Now,” and A$AP Rocky’s “I Smoked Away My Brain (I’m God x Demons Mashup)” (which samples “Just For Now”), were both trending this spring. Not only was Imogen Heap’s solo work trending, but Frou Frou, the short-lived electronica duo she was a part of, was also trending. In 2022, the group released a compilation of offcuts, and one track in particular, “A New Kind of Love (Demo),” was trending on TikTok around the same time as “I Smoked Away My Brain.” Another electronic duo, Crystal Castles, has fluctuated in popularity on the platform over the years, from “Crimewave” in 2020 to “Kerosene” in 2023, and onwards. Away from the bubbly yet somber electropop, certain subgenres associated more with raves and clubs — known as trance and dance — have also trended on TikTok this year. Snow Strippers’ fast-paced, “Under Your Spell” has gained much traction this fall. There is no denying that electronic music is back!

Raposo

Que Cante Mi Gente

by Izzie Claudio

visual by Hollie

Fania All-Stars

When June rolls around in Chicago, Puerto Rican flags tacked onto car windows are seen fluttering in the wind. The fences go up around Humboldt Park as the community prepares for a summer staple: The Puerto Rican Festival. Humboldt Park is a Chicago neighborhood home to thousands of Puerto Ricans, and our cultural pride is clear as you walk the streets. Family-owned restaurants every few steps, murals celebrating various villages on the island, and a giant arch donning the glorious flag — red and white stripes and one star backed with blue. I live a block away from the park, and to see it bustling with pride every June reminds me of the rich culture Puerto Ricans work so hard to preserve.

Music brings together many cultures around the world, and for Puerto Ricans that music is salsa. Salsa was born out of a multitude of sounds that were all floating around the melting pot of New York City. The hypnotizing Afro-Cuban rhythms, established jazz sound, and budding energy of rock ‘n’ roll all played a role in the birth of salsa. It was the ’60s and music was transforming and reflecting the turbulent times. Latinos were building a community in Spanish Harlem, and music was a way to spread joy and express hardships. After experimenting with style and instrumentation, the classic salsa sound

began to sprout. The rich brass moved to the frontlines, pianos oozed with Latin soul, and smiling faces sat behind congas as they carried that hip-swaying rhythm.

As salsa continued to find its footing, a legendary group was formed. Johnny Pacheco, a passionate Dominican musician, and Jerry Masucci, an Italian lawyer who fell in love with the Latin sound, joined forces to create Fania Records. With this record label, they aimed to build a solid platform for salsa musicians and a space for them to create this exciting new genre. Quickly, Fania All Stars was formed; a powerhouse group of salsa artists that began dishing out hit after hit. This group is where the bulk of classic salsa artists reached new heights. Willie Colón, Héctor Lavoe, Celia Cruz, Rebuén Blades, Cheo Feliciano, Ismael Miranda, Ray Barretto, and many others produced music with Fania Records and performed with Fania All-Stars. Salsa was taking over NYC, and this was just the beginning.

It’s the ’70s and audiences all over the world have fallen in love with the expansive instrumentation and powerful vocals that painted salsa albums. Many, especially Willie Colón and Héctor Lavoe, continued to draw inspiration from the urban grit of NYC. On many album covers, you can see the influence of ’70s action films, such as Super Fly and Shaft. That energy was captured visually, and inside the album an explosion of Latin flair that got audiences moving within the first few seconds. The infamous Fania All-Stars show at New York’s Yankee Stadium in 1973 drew a crowd of more than 40,000. This was a night bursting with energy and pride. Overwhelmed with excitement the crowd couldn’t

help but storm the stage. The music of their homes has been reinvented and echoes through the streets of the second island that they now call home; the island of Manhattan.

Héctor Lavoe’s 1975 hit “Mi Gente,” spoke to Latinos everywhere. This is a song about pride with lyrics that make you wave your flag high in the air and sing for those who came before you. Lavoe begins with a call to the community. He sings, “Oigan mi gente / Lo más grande de este mundo / Siempre me hacen sentir un orgullo profundo.” “Listen, my people, the greatest thing in this world. They always make me feel a deep pride.” Lavoe sings with an open heart in this tune; he connects with the audience from the start, telling them how his people inspire in him such profound pride. He is proud to be Puerto Rican, he is proud to be Latino, and all he wants to do is celebrate with his people. The chorus has a sense of freedom: you can feel Lavoe’s beaming smile as he thinks of his beautiful culture and the rich community that keeps that culture alive. He sings “Ay, que cante mi gente / Ahora que yo estoy presente / díganme lo que tienen que decir / Que yo canto como el coquí / El coquí de Puerto Rico.” Lavoe repeats the lyric “que cante me gente,” instilling a memorable melody. “Let my people sing,” demands Lavoe. Now that he’s here, he wants to hear what everyone has to say. He sings like the coquí, the iconic frog of Puerto Rico, whose recognizable whistle can immediately transport any Puerto Rican to the island.

Lavoe is not only calling out to his people to sing, he’s demanding that they have the space to sing. He beautifully melds cultural pride with a statement. Latinos faced many hardships as immigrants in the U.S.,

and they always deserve a space to let their culture ring free. Salsa created that space, and those rich horns still make hearts swell. This beautiful music sounds like home. Whether you’re pushing your way through the hustle of American cities or strolling the cobblestone streets of Old San Juan, this music will always bring so many people home. Izzy Sanabria, a collaborator with Fania Records and the CEO of Salsa Magazine, sums it up perfectly, “Salsa provided a rhythm and music that we could live by, breathe, and make love to. It was the essence of the Latino soul.”

The Classics

A “Mi Gente” - Héctor Lavoe

A “Pedro Navaja” - Willie Colón, Rubén Blades

A “Aguanile” - Willie Colón, Héctor Lavoe

A “Arroz Con Habichuela” - El Gran Combo De Puerto Rico

A “El Cantante” - Héctor Lavoe

A “Anacaona” - Cheo Feliciano

A “Juan Pachanga” - Rubén Blades, Fania All Stars

A “La Murga” - Willie Colón, Héctor Lavoe, Yomo Toro

How to Name a Persian Daughter

by Taraneh Moeini

by Rebecca Calvar

visual

Rahim Moeini Kermanshahi was born in Kermanshah, Iran on February 5, 1923. He was an Iranian poet and lyricist and is regarded as one of the pioneering songwriters of Persian traditional music. His wife’s name was Eshrat Atoofi; they were married for 67 years before her passing in 2013. Together they had five children; Shirin, Hossein, Noushin, Maryam, and Farhad. Rahim was an active songwriter for 60 years, and during that time he published over 20 books and wrote lyrics for nearly 500 songs. All of this can be learned from his Wikipedia page, which has been revised 600 times by random Wikipedia contributors.

All of this is generic information that anyone can learn about him. Unlike his lyrics, it is not very personal. Nothing very emotional, like his life, and nothing very beautiful, like how he spoke. Everything I remember about him is grand, beautiful, and heartbreaking. He exuded wisdom and passion. When he looked around a room, he hardly spoke — his eyes were noticing every single detail around him. He wrote so much in his life and said so little. My father, Farhad Moeini, loved his father so much. And Rahim, my Baba, loved me.

My grandfather, who we called “Baba,” meaning “father” in Farsi, was incredibly proud to be Iranian. He felt Iran was the greatest country in the world and he used a lot of nationalistic themes in his songwriting. He thought the younger generation of Iran’s post-revolution society lost sight of its greatness and lost pride in it, which he believed was the worst thing that could happen. If the younger generation cannot believe in Iran, then who will? What home do we have to go back to?

Persian traditional music is driven by emotion and mood. The lead singer is crucial, not just because they are the lead singer, but because they set the strongest tone for the music. Poetic lyricism is imperative for highly regarded Persian traditional music. The lyrics are typically composed of specific themes. One is nationalism—Persians are incredibly proud of their country and culture. Another popular theme is love,