Dear Reader,

This edition of The Rough Draft is like no other. Embracing the absence of a specific theme, the dedicated members of the lit mag knew that this edition had to emerge from our authors, artists, and community. This choice was a calculated risk we knew would be rewarding. We sought to enable and inspire the artistic voices of our community, resisting the typical enforcement of conformity when our goal was to embrace unconventionality.

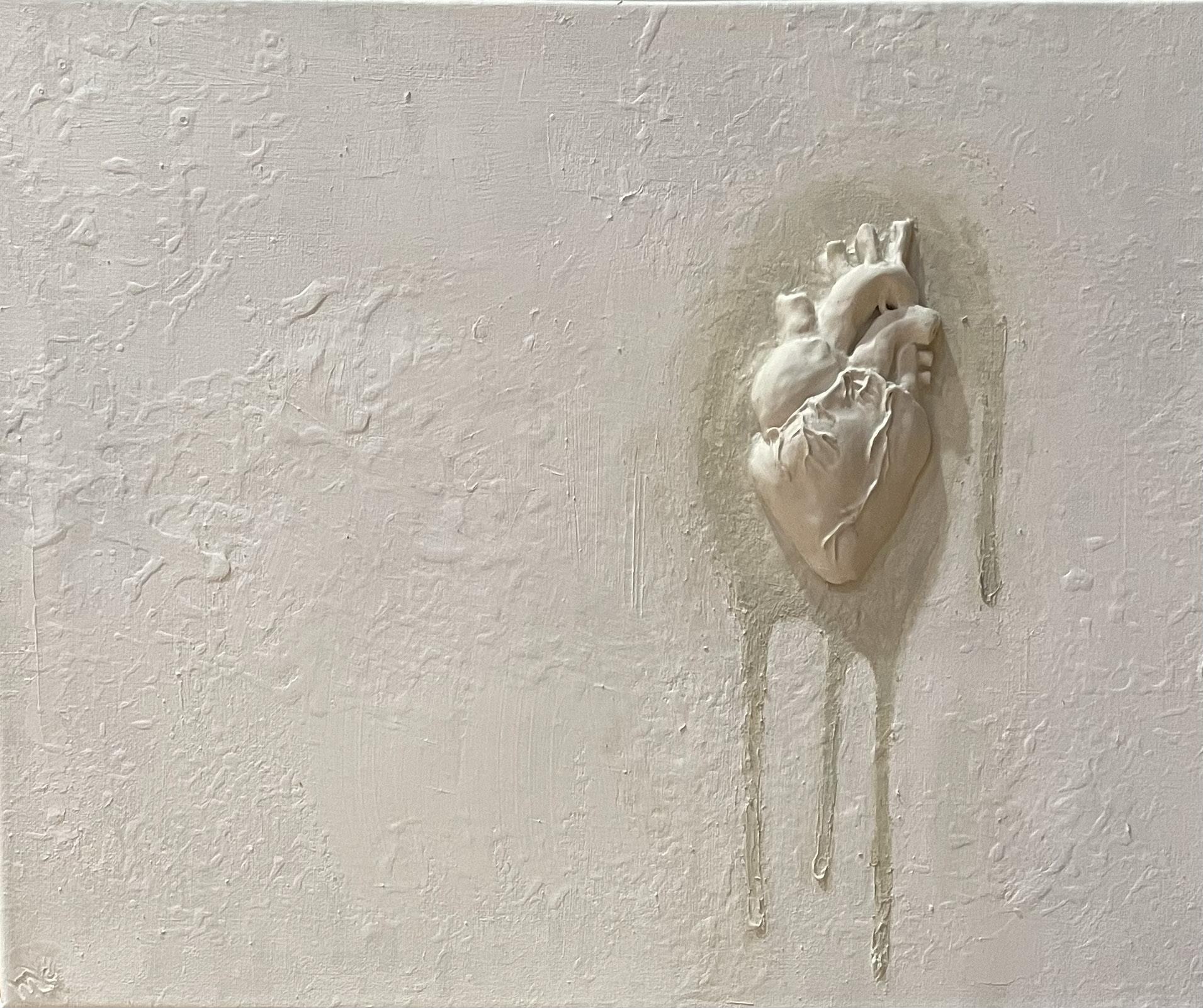

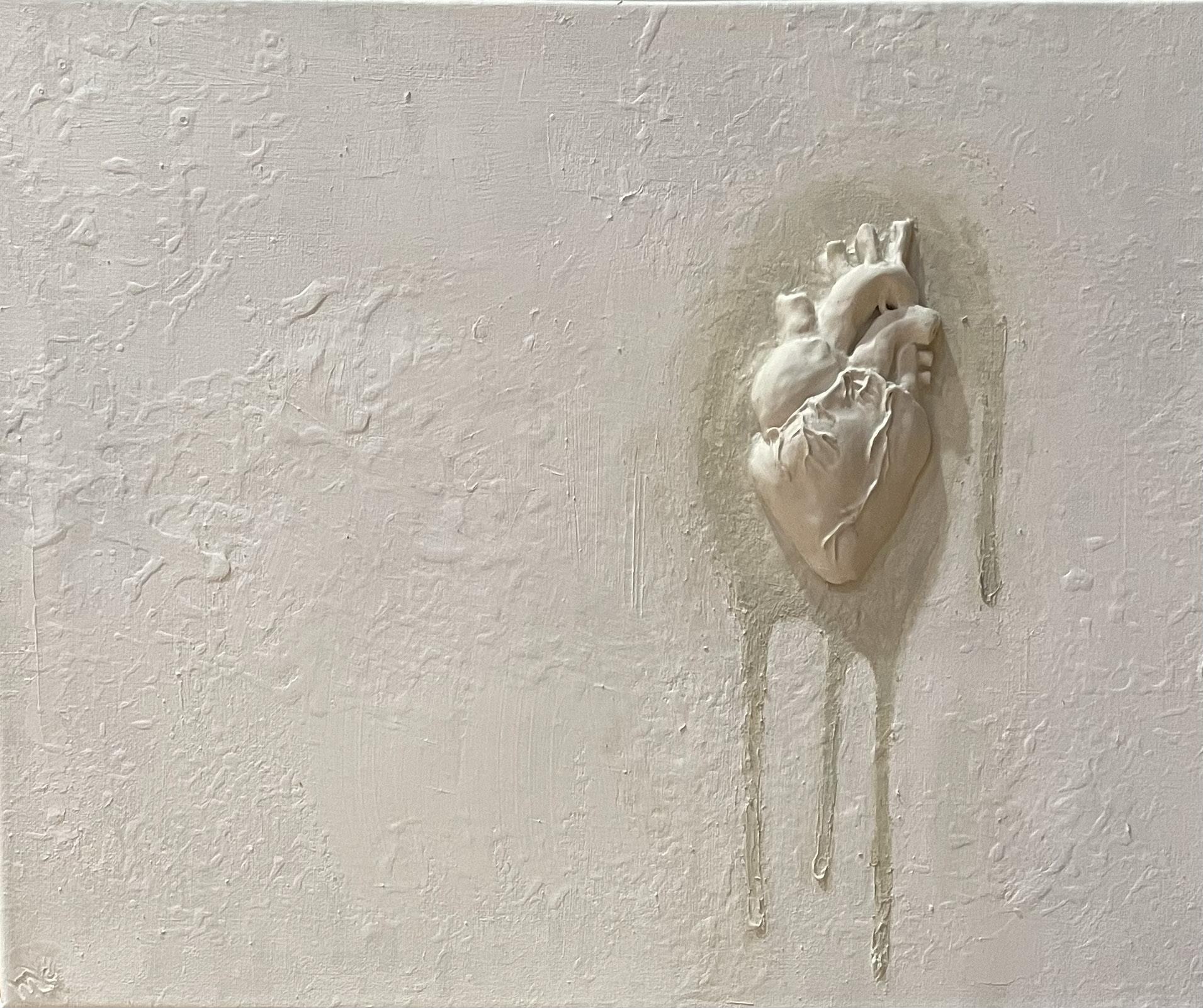

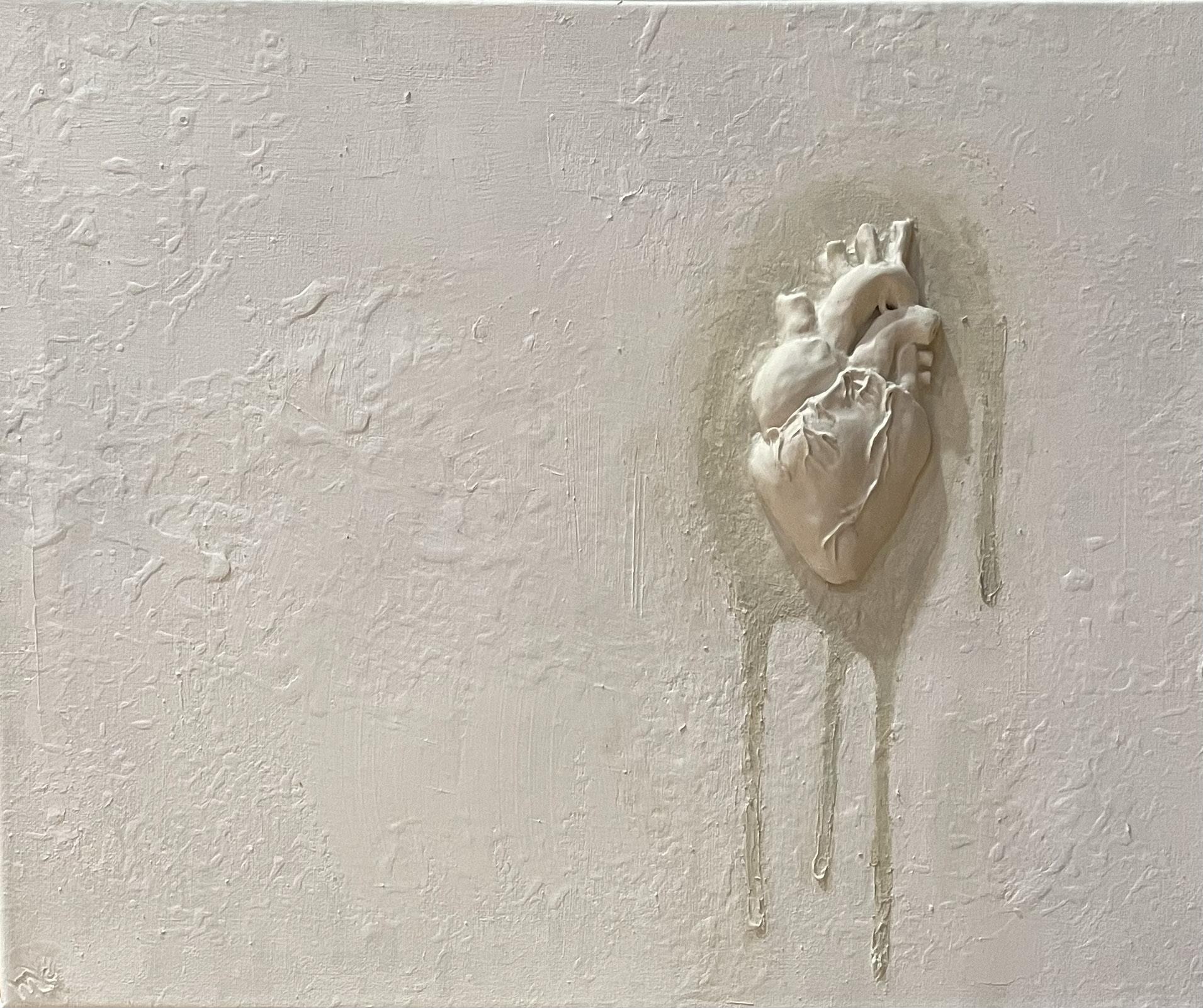

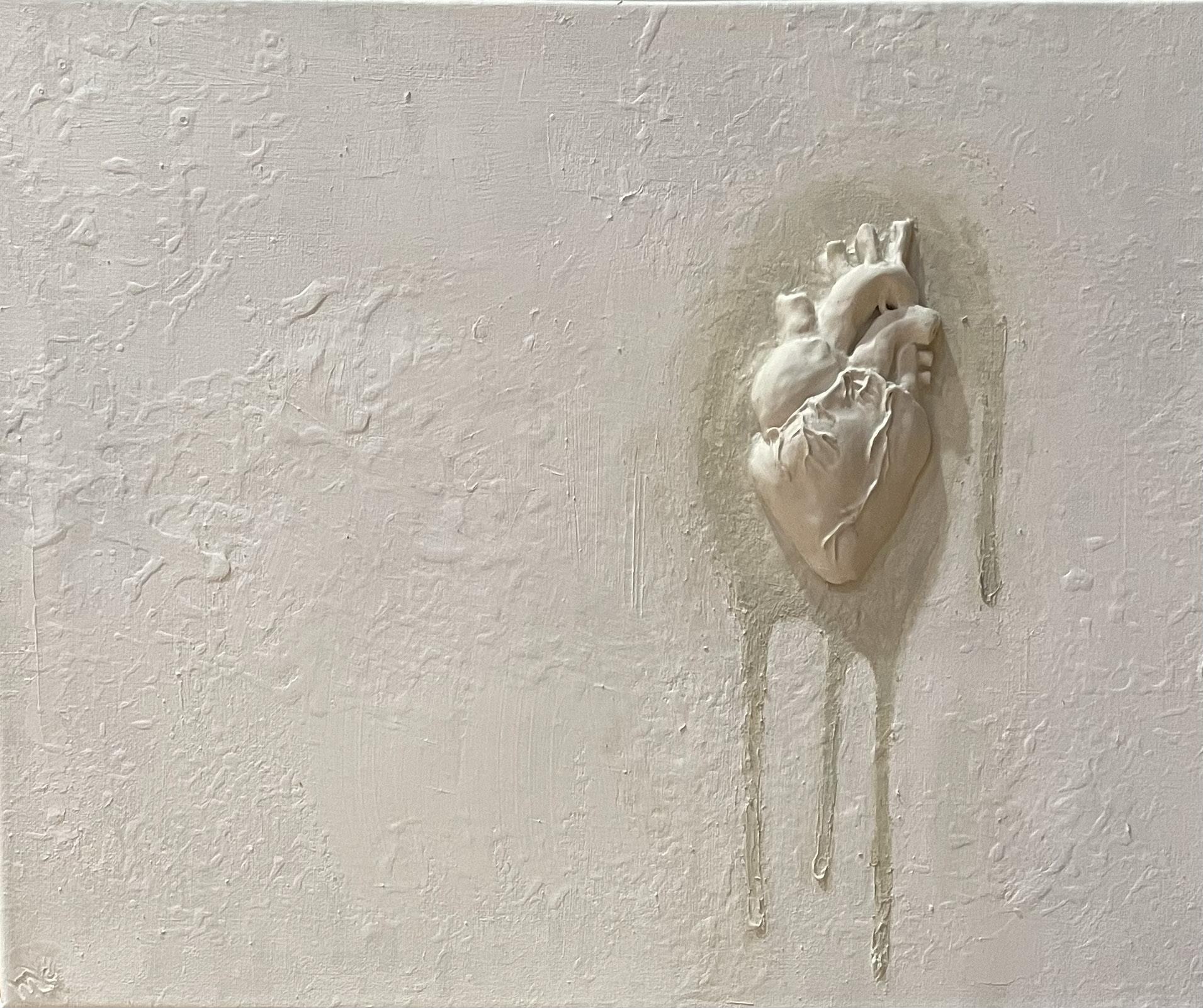

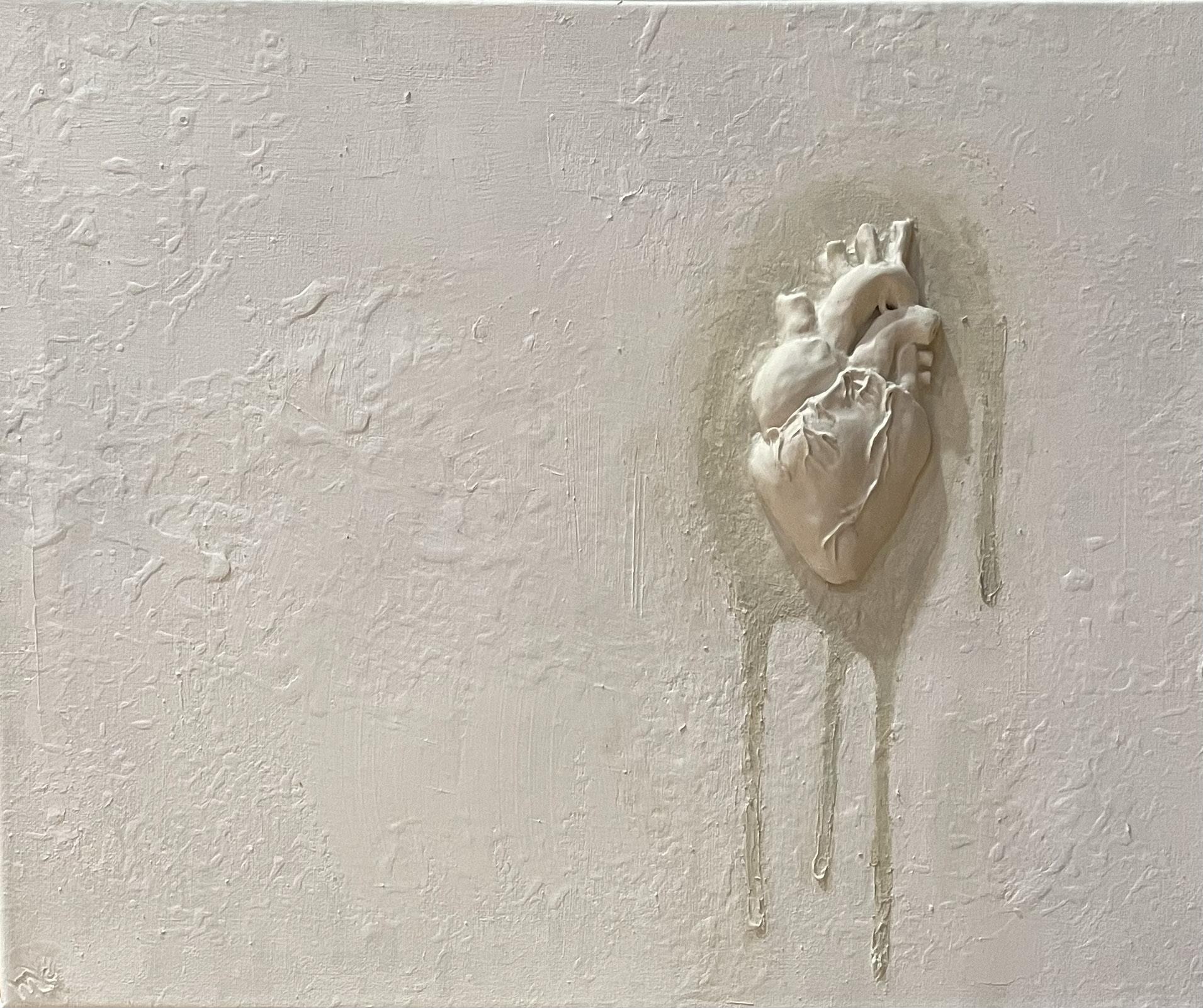

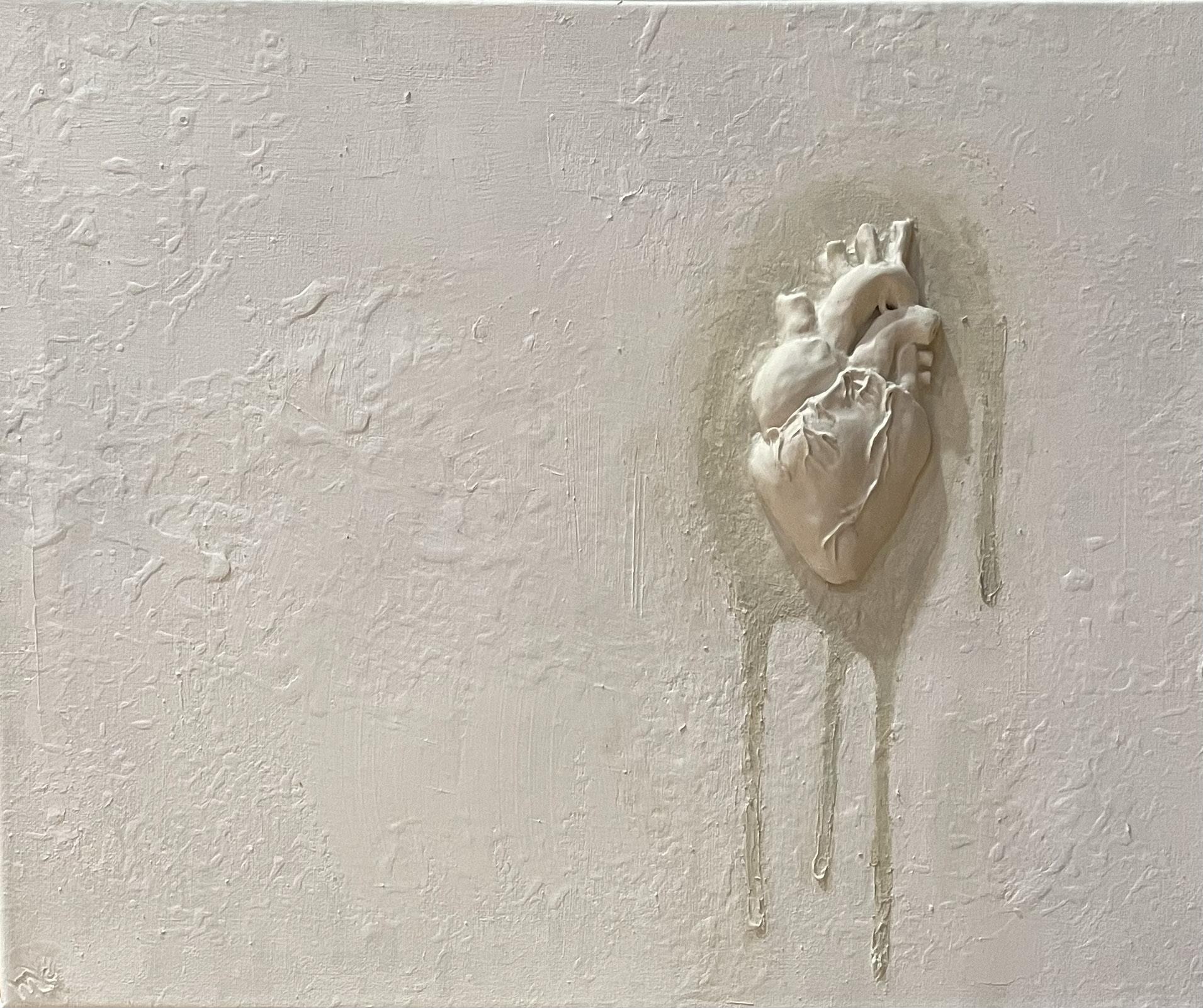

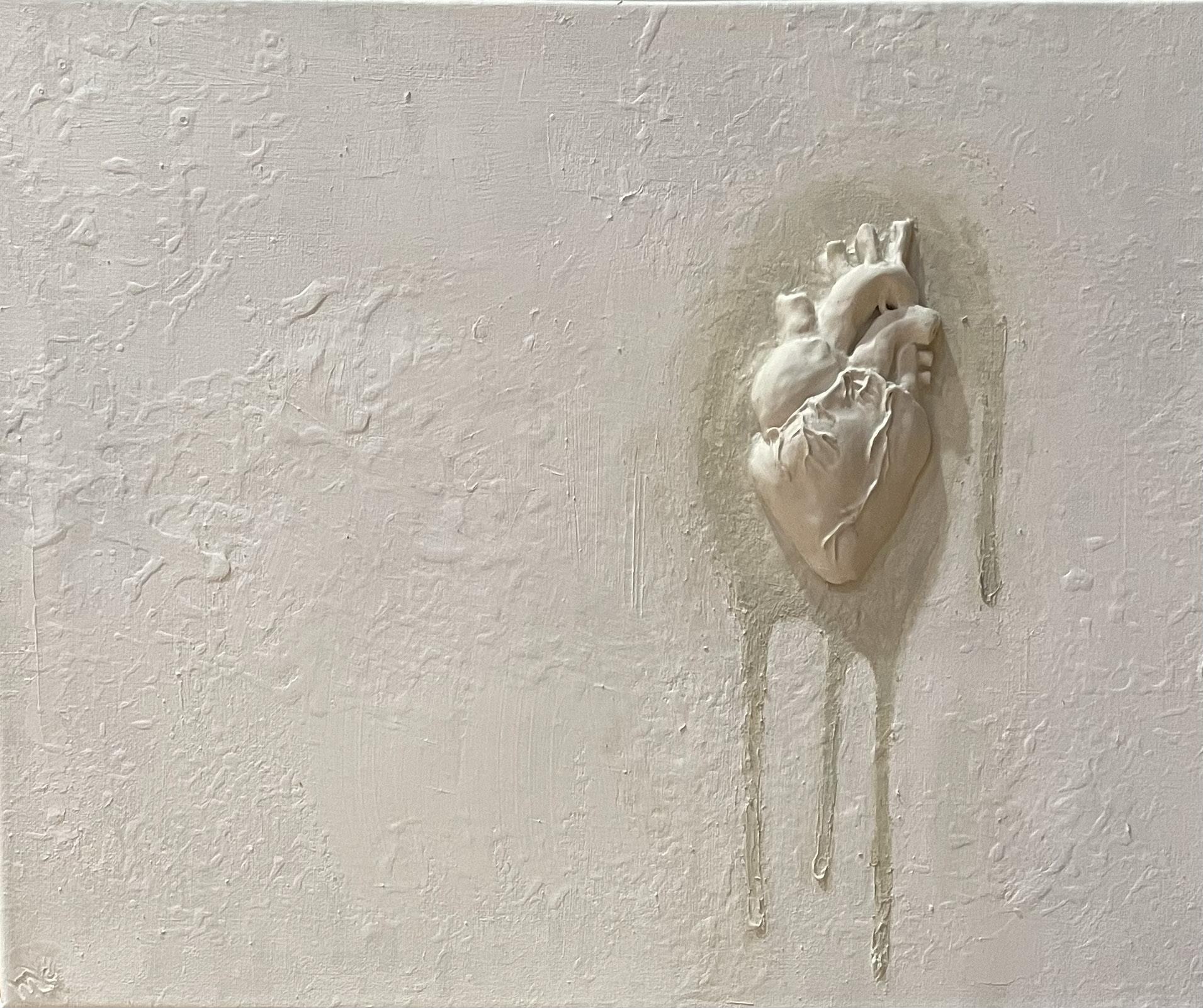

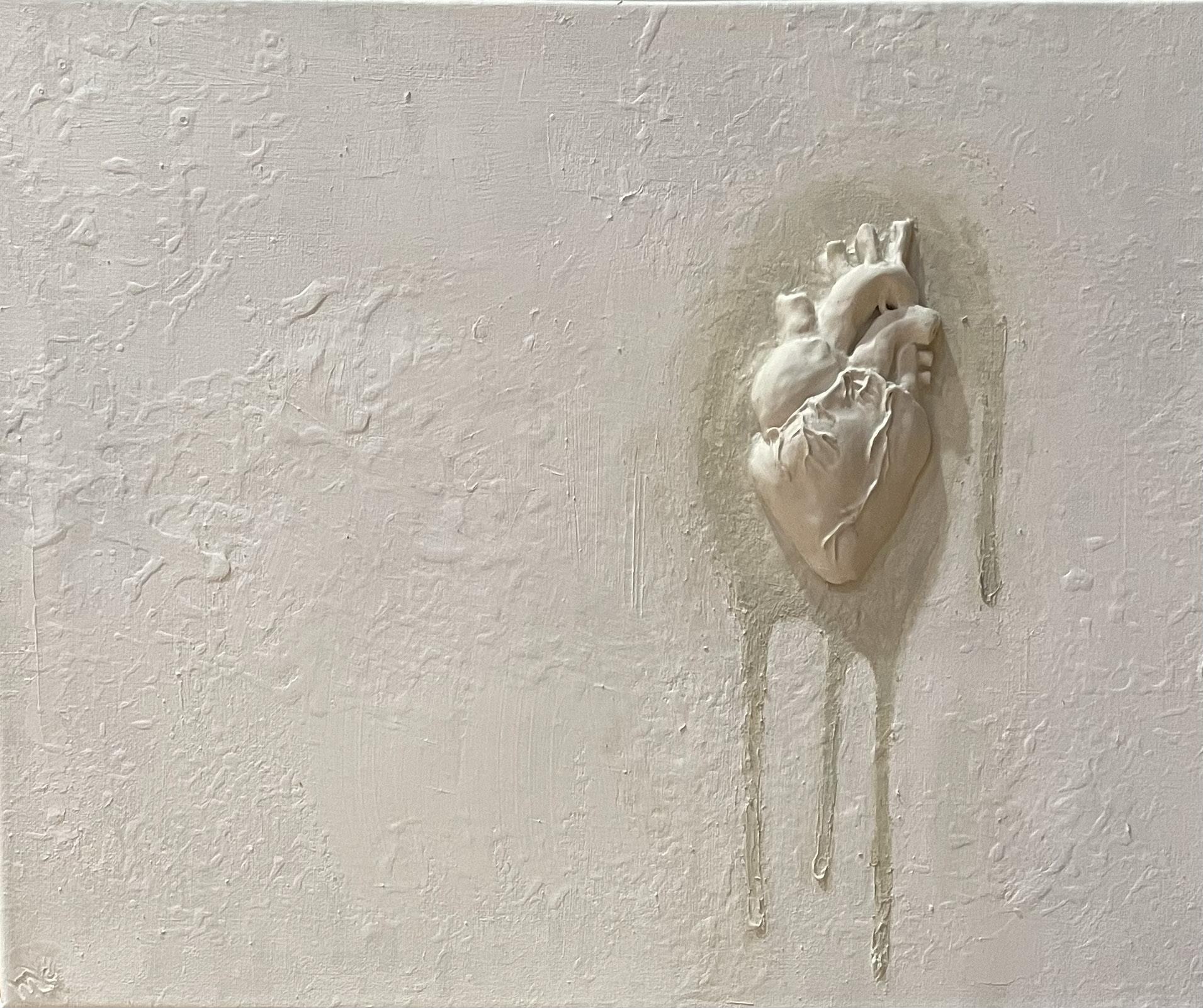

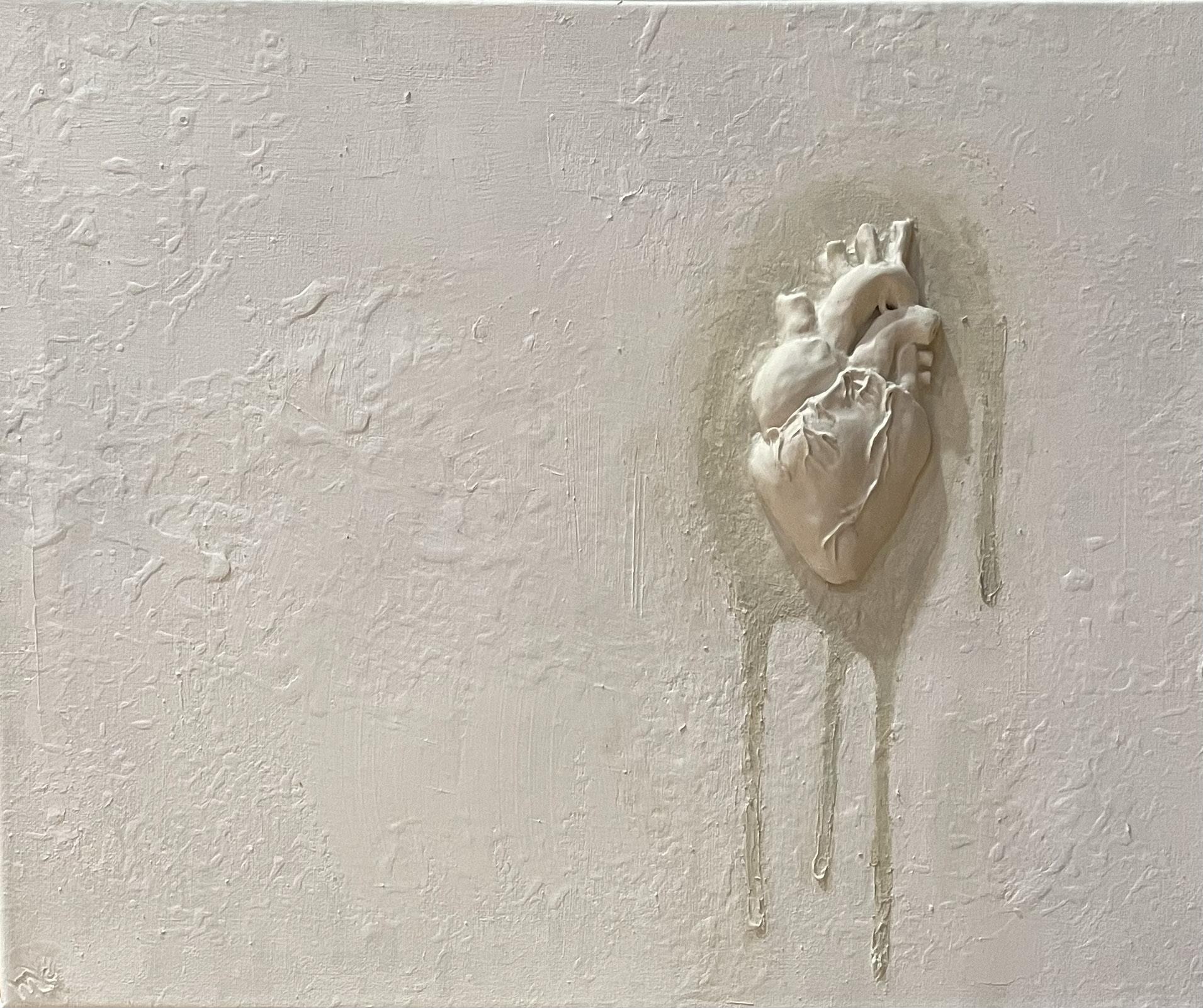

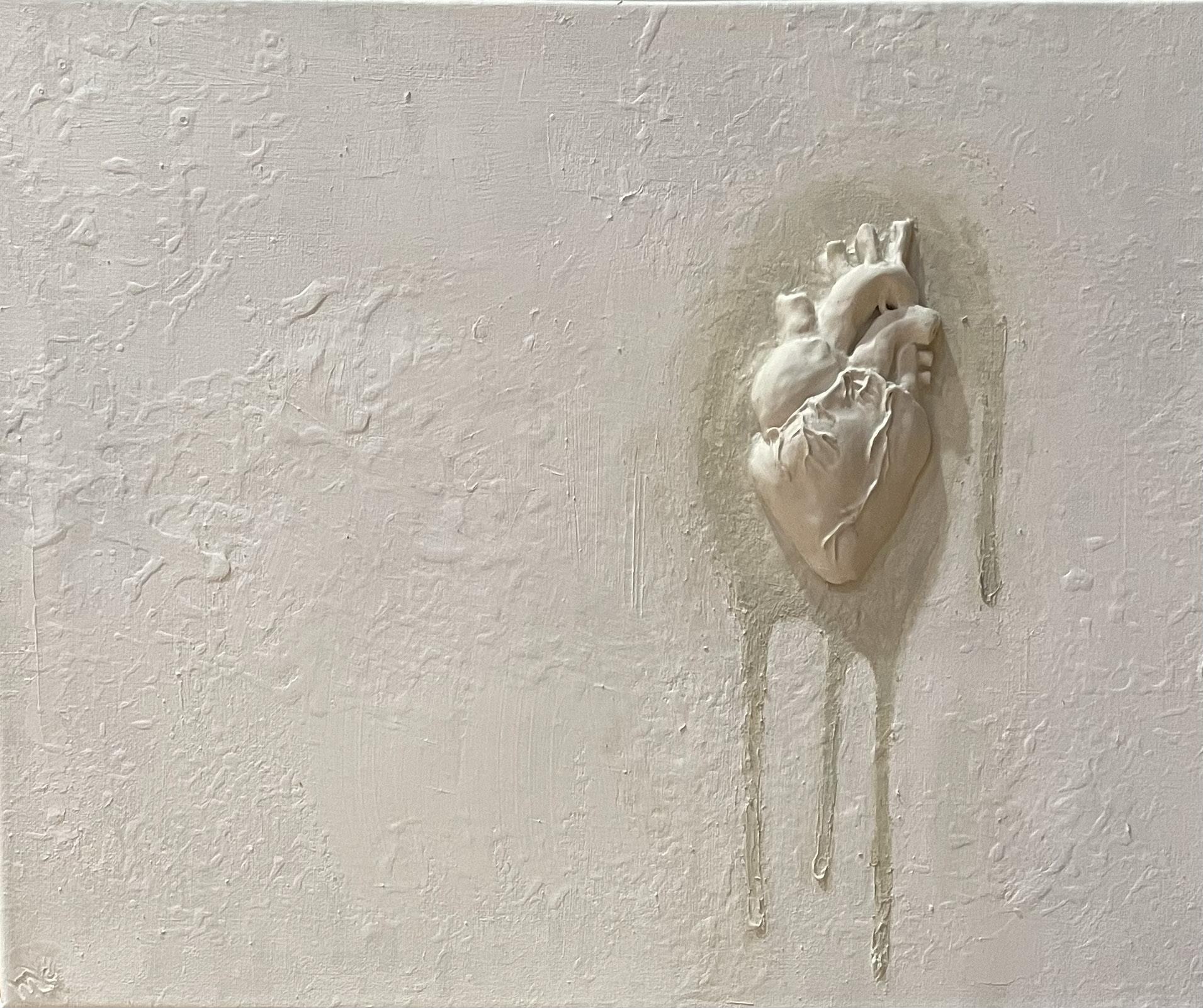

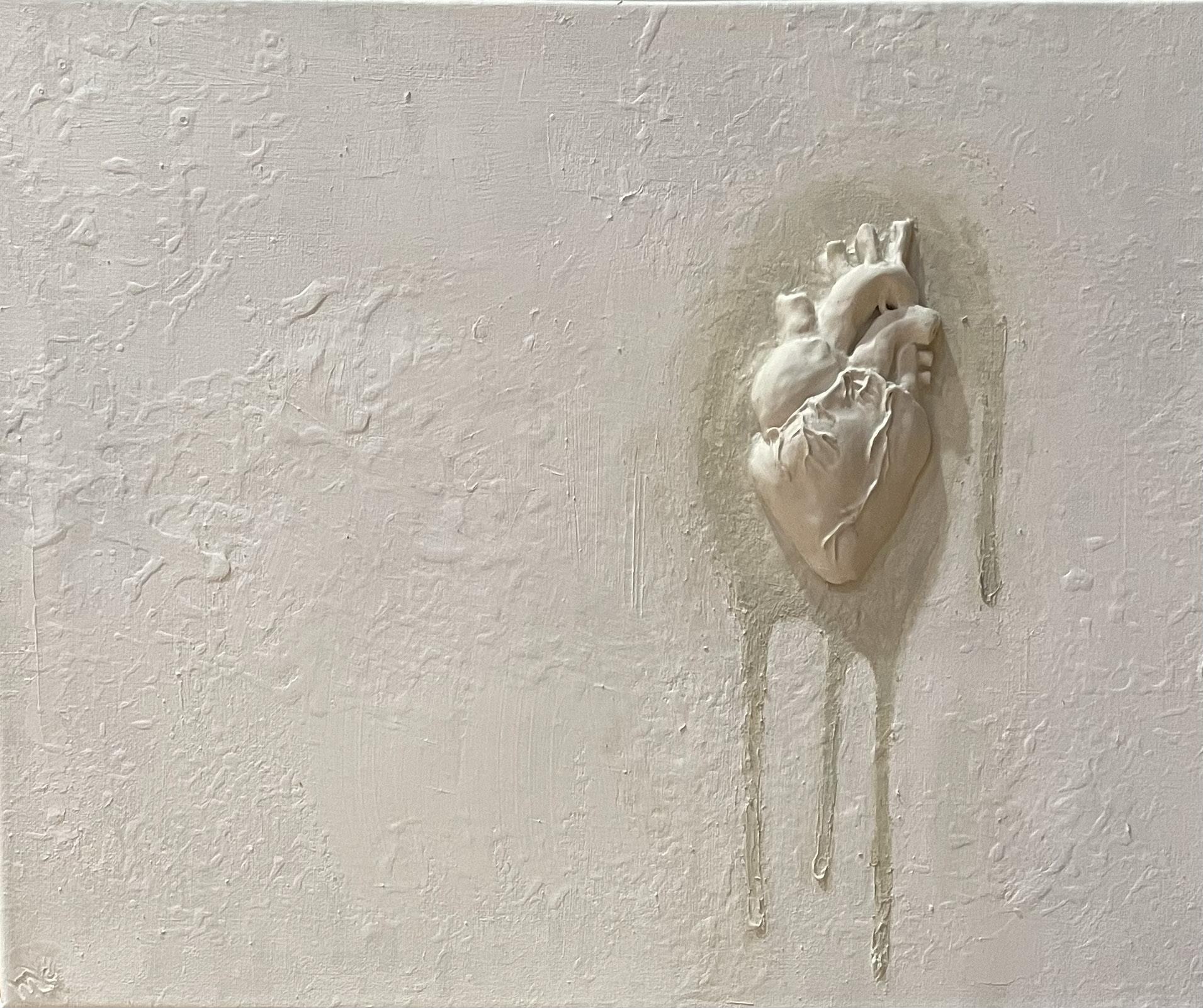

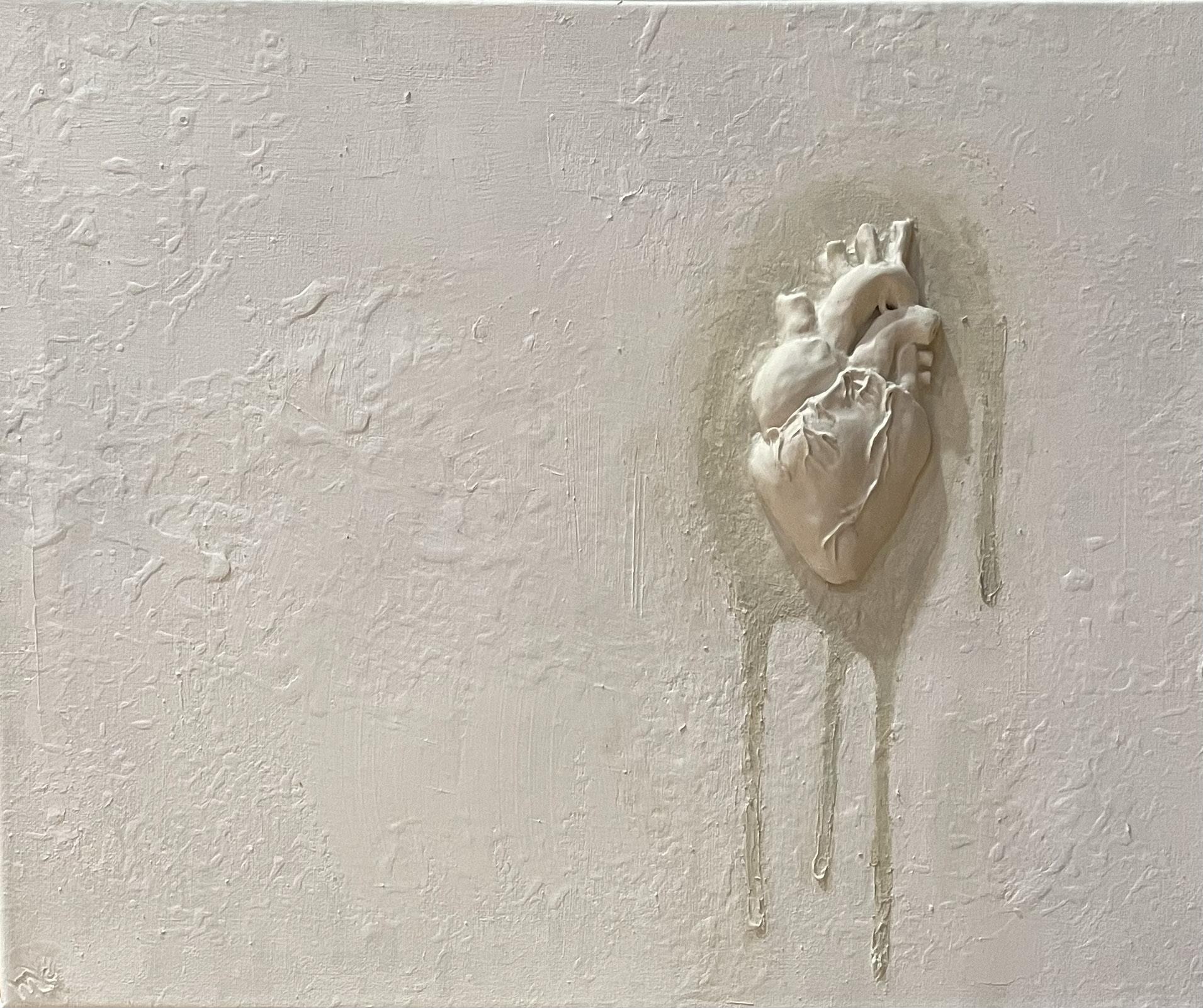

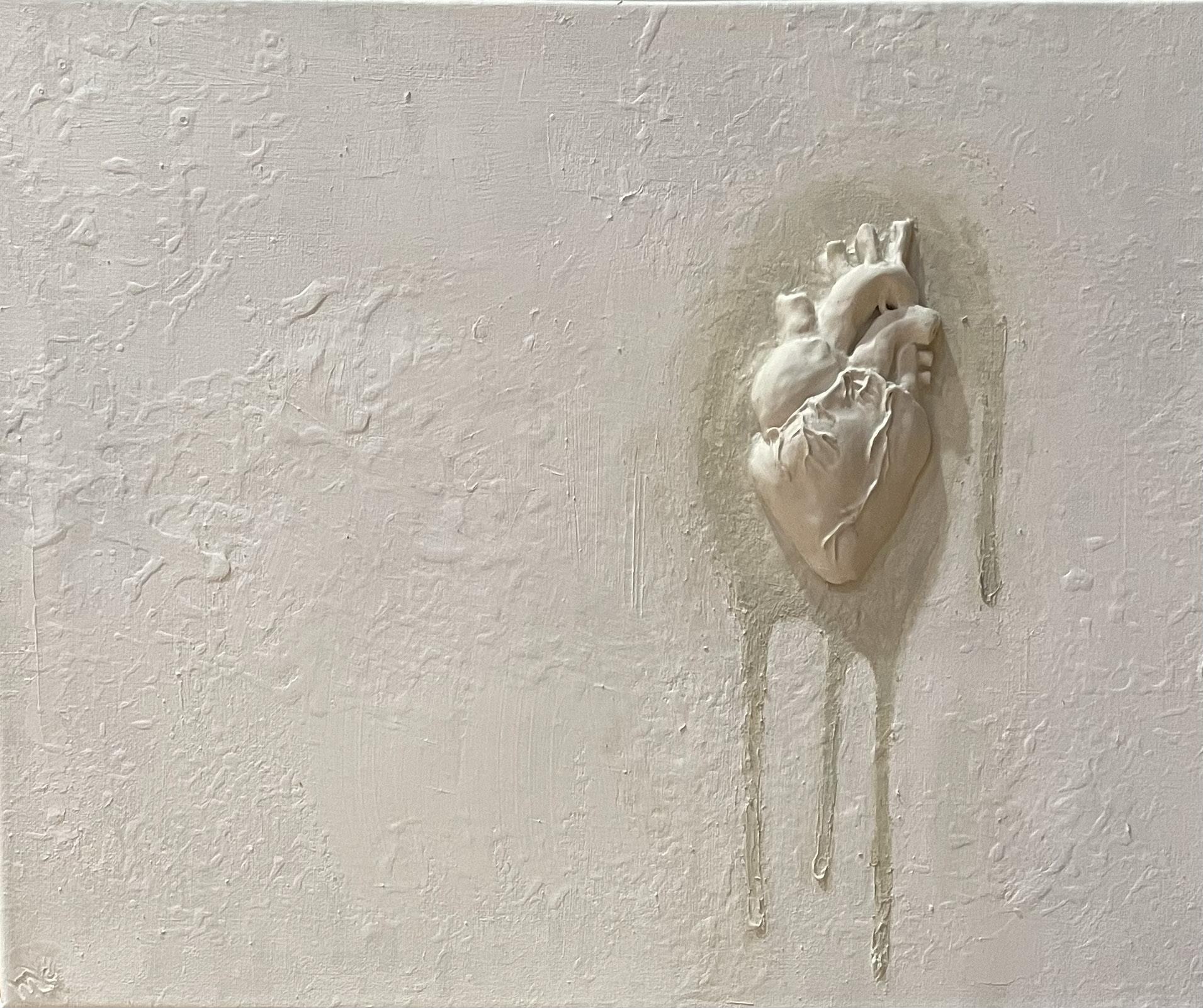

We knew that the heart of our magazine would emerge. And it did–figuratively and literally. This gold-encrusted heart encapsulates the essence of this magazine and our overall message of an emotional arc with some classic teenage angst. As you read through this edition, the vulnerability and honesty from our contributors will be instantly evident. You will soon read about the sweep of emotions that the human heart can feel: love, grief, joy, memory, etc. In such a turbulent and formative period of our lives, having a creative outlet to which to contribute creates a conducive environment for creative expression and hopeful belonging.

We decided to take some of our past critiques to heart, scale back on the design aspect and take a more minimalist approach to let the words and art speak for themselves. We chose to approach our teachers, department directors, other faculty members, and our peers to evaluate our past publications and grapple with suggestions that would improve our publication. We listened, embraced uncomfortable conversations, challenged tradition, and refined our purpose as a vehicle for creativity. We listened. We debated. We opted to focus on valuing minimalism. By doing so, we hope that we changed this magazine for the better.

It has been an honor to be a part of this process for three years, and I hope you can connect with this edition like I have. There is no doubt in my mind that this magazine will be left in the hands of brilliant storytellers, artists, and editors. As the editor of this student-run and student-produced publication, I hope that you appreciate the talent of this group and the hard work it took to create this. I hope that you are left inspired, touched, and motivated to write—because good writing is never finished.

A special thanks to our members, community, and our phenomenal sponsor Dr. Allred, who has played a fundamental role throughout the production of this publication.

Ida Nour Guerami, Editor-in-Chief

Ida Nour Guerami, Editor-in-Chief

It was too big of a bite. Slowly, it travels down, Leaving flames to burn me inside out Heat sizzles off my skin, Sweat trickles down my spine, The words Fire! Fire! erupt in my mind, I want to scream,

But I can’t because of where I am, So silently, I cry instead and think vehemently of what could have been:

Oh, if I only chose a salad!

Oh, if I only averted the luscious meat and cheese of the mighty chicken burger!

The beat of my chest danced sporadically.

Oh, my Lord, My heart was on fire.

Are lives just a randomizer within a giant while loop?

An endless cycle, a never-ending pursuit

Of choices made, paths taken, with each step, a new randomization?

Or is there a purpose, a reason for each twist and turn we take?

Is there meaning in the madness, a cause behind the highs and lows?

Or are we just players in a game, our moves predetermined by an algorithm?

The thought of it all, it makes me ponder…

Is this loop infinite, a never-ending ride?

Or is there a condition, a breaking point in the code?

The questions linger, and I can’t help but to wonder

If there’s a way to end this cycle, a chance to break the pattern

Or are we forever bound, to play this game, with no way to escape or to know the end?

But I still hold on to the hope that my effort isn’t in vain, And search for a way to debug this cycle, break free from this chain.

import java.util.Random; public class Main{ public static void main(String[] args){ Random random = new Random(); while (/*???*/){

String name = Values.names.get(random.nextInt(Values. names.size()));

int choice = Values.choices.get(random.nextInt(Values. choice.size()));

int path = Values.paths.get(random.nextInt(Values.path. size()));

Human temp = new Human(name, choices, paths);

public static class Human{ private String name; private String choices; private String paths; public Human(String name, String choices, String paths) { this.name = name; this.choices = choices; this.paths = paths;

Harriet

HoskingWhen I say I love you

I don’t love you like birthday cake

The special occasion kind of sentiment

With candles and a song

I don’t love you like that

I love you like a comfortable sweater

I love you in an every day, soul- crushing, mind- boggling way

So when I say I love you more

I don’t mean that I love you more than you love me

I love you more than any other person here

I mean, I love you every day

I love you lives in the coffee in the morning

In the tender moments

In the laughing at an inside joke and a heartfelt hug from behind

I love you like this because when it isn’t expected it’s better Because birthday cake always tasted better at midnight anyway

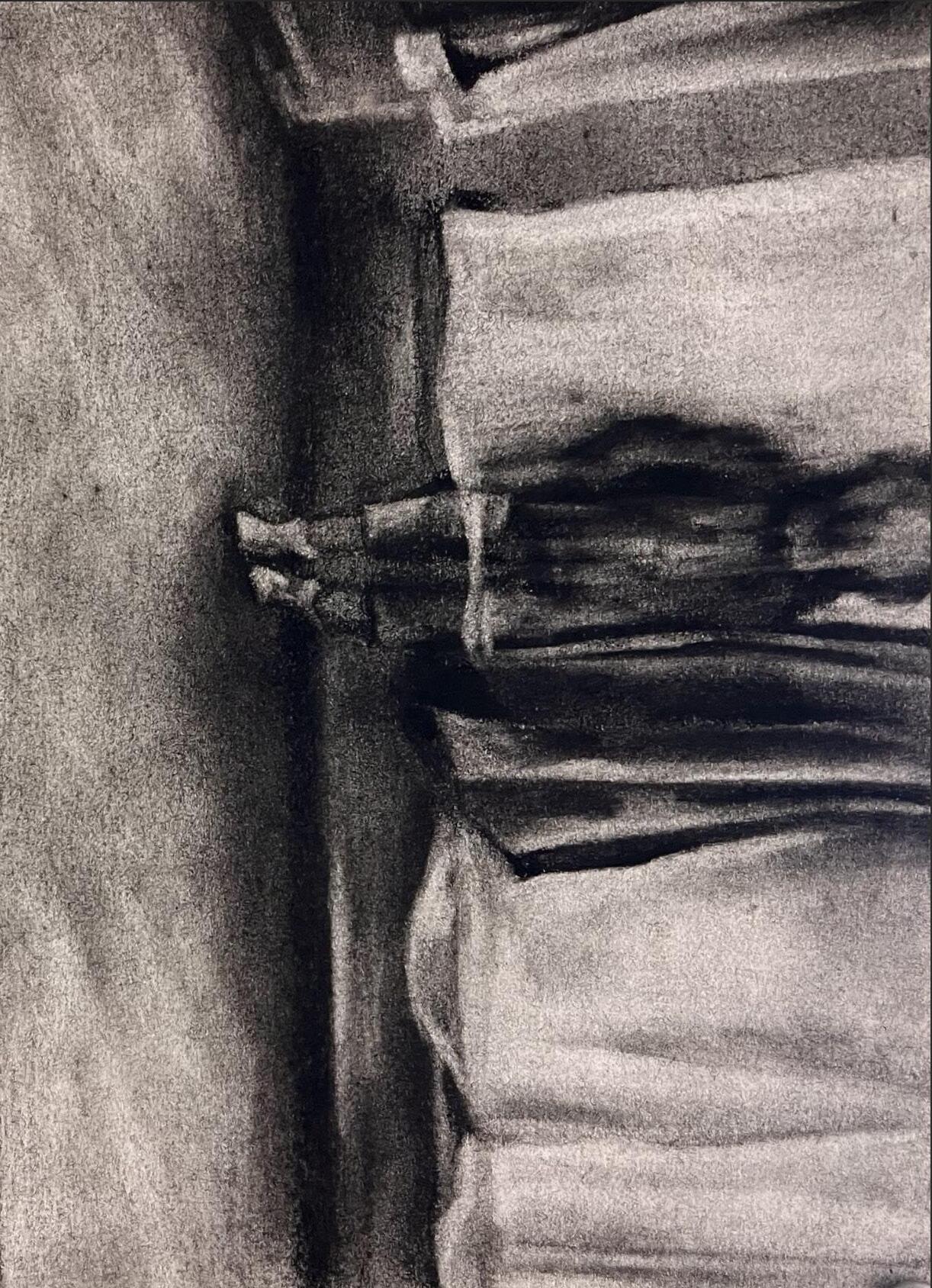

Connor CarricoGrace Semko

to distract me from your state.

twists and turns

could ever want.

but instead, beg my mind to let me rip the sickness from you, the universe.

and i fear i will never be the same.

When I first start learning, infinity’s the limit Every day is undefined, nor hour, second, minute One line is what I’ll follow, one value to the next

At the bottom of the mountain there is no apex

Yet, an endless scale of x’s is too steep a hill to climb, If I do not know my limits, I lose myself in time

If beginnings come from nothing, they break the rules of physics, If infinity’s the endpoint, I can’t use analytics

But accounting for the trillions and my polyhedron foes Appears a little clearer written as ones and ohs Instead of deviating with mathematical precision, I’ll cut the apple in five slices with the simplest division.

So to give a little value to the point that I now linger, Every year I spend with you, I’ll count upon on my fingers Counting up from one, I’ll raise my hands up high, And each number I go up, I’ll do it with more pride.

One person I love most who I’ll know for all my life, Two loving eyes that watch me, and hide from me the strife

Three more books at bedtime, before the lights go out, Four furry heads to coddle before they start to pout

Five fingers on each hand, braiding gently in my hair, And six pieces of advice when life brings more to bear

Seven sunny days where I will see you on and off, And eight cups of hot chocolate when the cold air makes you cough

Nine looks a little older, bringing a newfound sense of fear, Now ten is double digits, and the numbers are unclear.

….andifIonlyhavetwohands,wheredoIgofromhere?

Now, as I grow older, why does math get so complex?

I can’t put it on one finger, or count it on the next.

Now I search for every point that accounts for the logistics, And calculate the error of each medical statistic.

What’s the probability of the optimized return?

I can’t keep adding upwards when the rules are not as stern. Life is money, life is numbers, life is a slivered chance of luck The interval’s defined and now your value’s stuck.

But when I find I’m adding backwards in a tri-dimensioned space, Asking which values won’t exist and who could ever take their place,

I remember math is futile in the universe’s laws, And has no grasp on fate when cancer sinks its mighty claws.

So if life is just that simple, of numbers and of shapes, I can define it once again, and seal the holes with tape And if I only have to count, I think I can learn again, I’ll count it on my fingers, but this time start from ten.

Ten is worth a lifetime, a decade full of love, Use nine lives with caution before nature’s fist ungloves Eight is worth a cake, someone grab a lighter, But seven’s not enough for them to tell you you’re a fighter

Six just pastpassed the checkpoint, almost made it out alive, I’ll have to pack my bags in case you’re only here for five Four years is way too long for me to journey far from home, And three is just too short for me to spend it all alone

If the bell is ringing twice, here comes the Holy Trinity, But if you only have one left, I love you to infinity.

Ifyoucountuponyourfingers, Thereisonethingyoushouldknow Whencountingdownfromten, Youwillalwaysreachzero.

Yasmeen Mogharbel

Surrounded by your achingly familiar town, You stand outside the solemn building once called home.

One step, two steps, three steps, With every patter on the cobblestones The old world melts away And a new one falls into place.

You leave behind The wispy remnants of childhood, The hazy summers and tumultuous winters. The past, now a variegated blur in your mind’s eye, Marred by beautiful, painful moments.

You long for The spark that breathless laughter made you feel, Childhood innocence slowly seeping through the cracks, Slipping away, Down to the earth’s fiery core.

Each step sheds the blissful cocoon Years of jaded repetition grants. Each step brings forth A novel set of unbridled fears, Accompanied by monsters’ faces Pressed up against the fog–Waiting, Watching.

You see The childhood demons you always ignored, Heartbreaking moments frozen in time. Every fear, every insecurity, every intrusive thought, That relentlessly haunts you With uncontrollable vengeance.

You crave The future you could only fantasize about, Effortless perfection, Praying your dreams are only inches away from coming true.

Your pace quickens, Your heart racing. The edge of the world seems tantalizingly close, And it’s all you can do to keep from reaching out to touch it.

One foot after another: One, two, three, One, two, three. One, two, One.

Bridget Frank“Choose your color,” my mother said as she held out a col lection of paint chips. For the 5-year-old version of me, this was the most exciting decision I could possibly make. What color should my bedroom be? After considering the options for a mere second, I point ed to “fuchsia,” a blinding shade of pink that perfectly embodied the intense girliness of my childhood. Luckily, my older sister was horri fied. She immediately protested, suggesting I go with “banana yellow” instead. As I sit in my “banana yellow” bedroom writing this essay, I realize that this was only the beginning of my journey with the color yellow.

The color yellow seems to follow me everywhere. It glows in the oily lamps we light during Diwali. It fills the sky during summer bike rides with my sister. It shines in my mother’s gold jewelry, ear rings and necklaces passed down from generation to generation. It slowly appears in our suburban landscape when autumn sets in, com mencing a season of family birthdays and new beginnings. It creates a vivid picture of my Indian culture as I add my grandmother’s daal and sambar to my dinner plate. I can even find it in my name, as it is synonymous with “light” and “sunshine.”

Why is the color yellow in almost every experience, every facet of my identity? Ever since I became aware of its presence, it has grown increasingly apparent and recognizable.

The color yellow is a reminder that all experiences have a silver lining. Throughout my life, I have struggled to see both sides of every situation. The pessimist in me loves to focus on the negatives, dismiss ing the good in circumstances I encounter. Whether it be a presenta tion in school or a competitive tennis match, a fear of failure seems to overpower any positive thought. Sometimes, these thoughts of selfdoubt and hopelessness can become so powerful that the “bright side” appears to be nonexistent or hypothetical. However, just as the color yellow remains a constant in my life, so does this “bright side.” Yellow has enabled me to understand that happiness, success, and fulfillment are potential outcomes of every situation. However, they are outcomes that I must be willing to work towards and seek out. Similar to how I became aware of the color yellow in my life, rec ognizing the “bright side” has allowed me to find it more frequently in the circumstances and challenges I face. The pessimist in me is still there. Yet, by changing my mindset, the negative thoughts have an increasingly smaller influence in my life.

Sydney KrugThe color yellow continues to be an aspect of almost every one of my experiences. It is a sign of reassurance and a source of strength. It reminds me of the positives in any given condition. Yellow has become a fundamental part of my identity and how I perceive the world. Whatever could have happened if my sister had not prevented me from choosing “fuchsia” all those years ago?

There’s nothing that makes me happier than the sound of my mother cutting open a cardboard box after receiving a package.

Growing up, cardboard boxes were a key element in my household. The way I interacted with boxes changed many times throughout my life. When I was an infant, my grandfather would create a “baby bus” by connecting a box to a rope, placing my brother and me inside and pulling us around the house that way. This allowed us to achieve speeds that were not yet achievable by crawling, and most importantly provided all three of us with pure joy. As I got older, I loved sitting inside of cardboard boxes just to enjoy the coziness and comfort that being in a small space brings.

My twin brother and I, who have always been referred to as “opposites” because of our very different interests, loved to showcase our passions to one another since a very young age. He loved prehistoric mammals, ancient civilizations, and dinosaurs, while I loved painting, building, and plastering stickers onto every surface which I was allowed. This led to our iconic creation of a “museum” in the living room, made of several joined cardboard boxes and with items carefully hand-picked by my brother, especially small models of dinosaur skeletons. Our collaboration on this project strengthened our bond and sparked my interest in pursuing the arts.

Boxes are meant to be explored, transformed into complex shapes and spaces–and sometimes, they’re meant to simply provide the coziness of a small, enclosed space. Simplicity has a unique, comforting, and cozy quality of its own.

Although my room is small, I’ve spent countless hours customizing it to accurately reflect my interests, the people I enjoy spending time with, and my beloved simple comforts such as my soft blankets and pillows.

Recently I’ve been exploring a variety of new interests, such as international relations, foreign language, environmentalism, and architecture. When asked about my future plans and how I would possibly connect all four passions, I was often told to “think outside the box.” I was skeptical about this approach and believed that I would ultimately only have to choose one to pursue later in life. Yet now I realize that it’s possible to embed my love for design in all four of these interests. And while I found the “think outside the box” phrase slightly daunting, (because how could you possibly decide on one way to connect ideas–there’s so many options to choose from!)–I instead began to “expand on the box”. I’ve been exploring how architecture designed with the local environment in mind can influence happier populations, reduce emissions and eliminate the waste of resources. I dream of bringing this kind of eco-friendly architecture to countries worldwide, especially my family’s home country of Kazakhstan, where pollution plagues several large cities. Studying foreign languages will improve my designs as I gain the ability to communicate with global communities and gain an understanding of their cultures, ultimately influencing my designs to not only reflect an environmentally-conscious approach, but also each population’s history and customs.

Years of exploring who I am–through design, language and collaboration–have all been possible thanks to my hobby of tinkering with cardboard boxes. I’ve developed my lifelong philosophy of working “from the inside out.” Rather than thinking outside the box, I expand on the box. I add new layers and new spaces for ideas to grow and flourish. Or I completely take it apart, bend its walls, and convert it into a cylinder or some sort of abstract shape. And to top it all off, I add stickers and bright colors. Because my ultimate goal is to share my intertwined passions with the people I love, bring them joy, and create a healthy and sustainable planet.

Ida Guerami

Ida Guerami

Our love was in the abstract

Where I could create the boy who was capable of being more than the “All-American” that his father lived vicariously through

I bet he painted me red, white, and blue too Colored over my brown hair and made it blonde

We were both trying to create a masterpiece with no canvas

So talented, reckless, and delusional but that’s what made it revolutionary That’s what made us memorable

I was a modernist, and he was trained to be a traditionalist

It would’ve been beautiful, it could’ve been magnificent

If only we were given a canvas…

Siena Wilson Jennifer Kim

Jennifer Kim

Look to this window, where we used to sit together holding lopsided mugs, burning our skin with the heat of steaming tea. Our stools placed towards plum-black skies touching the farpushed horizon, rainy March weather where the soil turned to mud soup, goldened clouds in pinky skies luminescent with the last snatches of daytime sunlight.

Was it our past selves that came to you first? I thought the world of you. The late winter mornings after a sleepover when you would press your heavy palms against the chilled glassy surface, trace smiley faces in the fog of your warm breath. Pans scraping in the kitchen, the smell of butter bread slick in the air, the feeling of being children, and being young and being free. Or did you feel the sting of red wine against your lips, knees pressed firmly into your chest, a chatty night catching up on the sofa as newfound adulthood greeted us?

When you saw the stars, I saw the stars in you. Not in that over type of way. But the slight glimmer of the moonlight fed the

Katherine Nurikblacks and browns in your eyes, like an artist had filled them in with dots of clear white. There was something poetic about the freedom painted in the air the day we turned twenty together, like we had physically evolved from the narrow minds of teenagers. That freedom was beautiful. It was the cool night wind sliding in from outside stroking our faces, and I knew I wanted to cry, the short burn behind my closed eyelids and the dull ache in my chest pulsing so hard it was almost visible in the air between us.

It’s been over a decade. The edges of you in my head have started to fade, not an abrupt exit like the ending of a play, but I can feel the special narrative of us coming to an end. I can feel the plot dying like an unwatered plant, the leaves paling and brittle as bark. But if I remember closely, I still conjure the window and our mothers’ butter bread and the wine we stole from my dad, the hopeful stars in your eyes and the freedom in mine, and how we used to look, like we were just getting with the world. Would the word friendship be enough to describe the feeling I felt for you? Would the word friendship be enough to describe any real friendship in the world? It’s just a word. It doesn’t embroider the detail of the salty, teary eyes of teenage heartbreak, or two kids gasping for air with their bellies sore from laughter, legs kicking at each other and the ground.

Look to this window, where we used to sit together holding lopsided mugs, burning our skin with the heat of steaming tea. Was it our past selves that came to you first? For me, it was us now. I can imagine you with smile lines and rougher skin. I can imagine you stressing over peppery streaks of gray hair scattered across your brown hair. We’ve been reduced to an occasional glimpse of a thought, a once-in-a-few-months type of curiosity. Our story was finally closing. This is my last passage to you.

Cast of Characters

Character: OLIVE Female Early/Mid twenties

Character: THOMAS Male Early/Mid twenties

Scene

The living room of the couple OLIVE and THOMAS. There is a couch, center stage, with a coffee table in front of it.

Time

Early evening, right before THOMAS gets home from work.

(OLIVE sitting on a couch, leg bouncing excitedly as she looks at her phone.

THOMAS enters, looking at OLIVE with anticipation. OLIVE nods, and THOMAS runs up and hugs her.)

THOMAS

Oh my god. This—this is just—really?

OLIVE

Yes, really.

(THOMAS holds OLIVE by the shoulders to look at her)

I can’t even—

THOMAS

OLIVE

I know

THOMAS

You’re really—

OLIVE

I am.

(another hug)

THOMAS

We have to call my mom, Ellen, oh, and Luca. Who else knows?

OLIVE

Just you. Just you.

Clara StevensTHOMAS

This is gonna be amazing! I mean, who would have even thought that I’d be doing this? When we tell Luca, he’s gonna be terrified. Happy, but God will the look on his face be priceless.

OLIVE

Ellen probably won’t believe it. Me? There is no way she’ll believe we are responsible enough.

THOMAS

Well, we’ll show them! (THOMAS starts walking around the room) We have so much to do!

(THOMAS grabs his phone)

OLIVE

Call your mom first!

THOMAS

Oh, yeah.

(THOMAS dials a number and holds the phone to his ear)

THOMAS

Mom? Mom, you’ll never guess what. I think you’re finally getting old.

(OLIVE playfully wacks his arm)

(quietly) Thomas!

OLIVE

THOMAS

Okay, okay, that was a bad joke. I was only saying it because... drumroll please... You’re gonna be a grandma! (beat) Really! (beat) She just told me. (beat) You’re the first to get the call. (beat) I’m serious! Why would I joke about that? Here, Olive can back me up on this.

(THOMAS hands the phone to OLIVE)

OLIVE

He’s telling the truth. (beat) I know! No, we haven’t thought of—

(THOMAS takes the phone back)

THOMAS

What do you want to be called? Gammy? Meemaw? (beat) No way. You can’t go by just Grandma. What about COW? (he laughs) No! It obviously stands for Crazy Old Woman.

(OLIVE takes back the phone)

OLIVE

I think grandma is a perfectly fine choice. (beat) Mhm. I will. Thank you.

THOMAS

Bye Mom! Love you!

(OLIVE hangs up the phone and gives it back to THOMAS)

THOMAS

I don’t think I can call anyone else right now. There is so much going on in my head. (starting to ramble) Oh! How are you feeling? Are you getting morning sickness yet? Wait, it’s dinner time. Oh my god! Do you want dinner? How hungry—

I’m fine. It kind of feels like my heart is going to burst out of my chest, but I feel great. I don’t think I could eat right now if I was the hungriest person alive. I can barely stand the thought of sitting down, I’m so excited. Okay. Alright. Grab some paper and a pen.

(THOMAS grabs them)

OLIVE

So we’re gonna need a crib

THOMAS

A crib. Right. Good call. What about pacifiers?

OLIVE

Yes! Ooh and formula. (THOMAS nods) And diapers, clothes, toys. Oh! And we’ll need to get a playpen. A car seat. Oh god and those mirrors people use while driving. Babies need special spoons, don’t they? Oh, and the bottles ! If we want to get ahead, we could even get books and shoes—when do babies even start to walk? Well, maybe ours will be a prodigy. What else? Of course

there’s the cradle and the stroller, too. And–

THOMAS Olive OLIVE

We’ll need sippy cups and those adorable little spoons.

THOMAS

Olive

OLIVE Yeah?

THOMAS

We have to think... um...

OLIVE

What?

THOMAS

Olive, we still don’t have the money.

OLIVE

(beat) I... I know that. I mean, I know that babies are expensive—obviously they are. But we don’t need to think about that— not for another nine months or so, right?

We can figure that out along the way. Hey... it’s gonna be fine. We’ll be fine. Thomas, we’re having a baby! This is amazing!

THOMAS

But we don’t have that long. Maybe until

Jeffrey Chen you freak out about those things? (beat) I know. Names. Let me think... Bert for a boy and Helga for a girl? (beat)Fine, what about Bartholomew? And Glinda? (beat)

THOMAS

(quiet) We could sell the necklace. OLIVE

THOMAS

(louder, still hesitant) We could sell the necklace.

the baby’s actually born, but we need to pay for doctor’s appointments, maternity clothes, and those vitamins everyone talks about. (beat) We don’t have that kind of money. You know we don’t. And you’re gonna want to have a baby shower! I want you to have a baby shower. But—

OLIVE

Hey, don’t worry. It’s going to be fine. I’ll ask for a raise—

THOMAS

But what about when you can’t work anymore?

We can’t pay for daycare! How are we supposed to pay for everything and have one of us stay home to take care of it?

OLIVE

Thomas, you need to calm down. Why don’t we just take a minute to be happy before

THOMAS

THOMAS

Then what do you expect us to do? There is no way a raise alone can pay for this. Even a promotion couldn’t! I know that you think

it’s important, but it would—

OLIVE

No! We can do this without selling it.

THOMAS

We have nothing.

OLIVE

Take out a loan.

THOMAS

And risk losing the house? Olive, just think this through. I want this baby as badly as you do, but there is no way to pay for everything we need to keep you both happy and healthy. Not unless we sell the necklace.

OLIVE

I’m not listening to this anymore. We are not selling the necklace. We can ask your family for help!

THOMAS

We can’t keep calling in favors! We have a solution. I just can’t see why you aren’t thinking this through!

OLIVE

You know exactly why. Why aren’t you thinking this through?

THOMAS

Oh, don’t tell me you still care about that.

OLIVE

Of course, I do! I’ve never stopped caring.

THOMAS

It’s from your mother! How can you even bear to see the damn thing?!

OLIVE

Because! I don’t want to get rid of something so important! It’s tradition!

(long pause)

THOMAS

I thought we were past this. You still want—

OLIVE

No, that’s not what I meant—

THOMAS

You want to give that thing to our child?

OLIVE

Listen—

THOMAS No

OLIVE

Let me explain—

THOMAS No

OLIVE

(shouting) Thomas! (beat) You have no idea how it feels. I’ve told you over and over

again that this is important to me. I will not sell the necklace and ruin it. My child will not miss out on this. Despite my mom’s behavior. I will not let how she treated me ruin my chance to pass on the feeling I got to feel. Just think about it! Once it’s born we can have a whole party where we give it the necklace. We’ll frame it in their room! Doesn’t that just make you so excited?

(long pause)

THOMAS

Do you even want it?

OLIVE

Oh my god, Thomas—I just went over this—

THOMAS

No! Not the necklace; the baby.

(beat) OLIVE

What? Of course, I want the baby. We’ve been planning this for so long.

THOMAS

Really? Do you really want this baby? Or do you want a baby? Some—some thing to pass on the necklace and continue your tradition of “feeling special”?

OLIVE

That is the most idiotic thing I’ve ever heard.

THOMAS

Is it, really? Because that sounds like you just want a way to continue the tradition that you think is so important instead of actually raising and loving a child.

OLIVE

I did not say that.

THOMAS

You said you wouldn’t let her abuse ruin the tradition that she inflicted on you! Can’t you see how ridiculous that sounds?

OLIVE

Well, that’s not what I meant.

THOMAS

It’s what you said!

OLIVE

We don’t even know if the necklace is valuable. Yes, it’s old and shiny, but—

THOMAS

Ten thousand.

OLIVE

What?

THOMAS

It’s worth ten thousand dollars.

OLIVE

How do you know that? Why do you know that? (beat) Did you take it to get it appraised?! (beat) You went behind my back and took a family heirloom to some jewelry store?! To see how much money you could make by giving it away to some random person?!

THOMAS

Yes.

OLIVE

Why? What reason could you possibly have to do that?

THOMAS

Things like this! This is the exact reason! We are having a baby! We can’t just hope for money to fall out of the sky. This necklace could pay for so much!

OLIVE

I can’t believe you’re thinking of this. It’s tradition! I pass it on to my child, they pass it to theirs, and it keeps going and going! I’ve told you this so. Many. Times. I don’t know how else to say it. I want this baby to feel loved!

THOMAS

Our kid can be loved without objectifying love! If you’re human enough, you can love a person without the need for gifts! We will love this child unconditionally, but I will not be forced to raise a kid without

any money.

(long pause)

“Human?”

OLIVE

THOMAS

Oh my god—You know what? I’m not arguing with you anymore.

OLIVE

We aren’t done with this.

THOMAS I am.

OLIVE

Well, you don’t make the decisions!

THOMAS

Neither do you!

(long pause)

THOMAS

I’m not just letting this go. If you don’t sell the necklace, you won’t be able to support your child. (beat) I need to go. I need to step into the hall. I need to think.

(THOMAS goes down to SL. OLIVE sighs and walks down to SR. Lighting changes so that it appears they are in separate rooms. OLIVE goes to the edge of the stage, where the necklace is. She

picks it up and holds it in front of her face. Both proceed to talk, sort of thinking out loud.)

What do I do?

BOTH

THOMAS

What can I do?

What should I do?

OLIVE

THOMAS

I can’t raise a kid without any money.

OLIVE

I don’t know how to do this without something to hold onto.

THOMAS

What if I can’t afford to feed us?

OLIVE

What if I can’t show it love?

THOMAS

(beat) What if Olive turns out like her mother?

OLIVE

(beat) But what if I turn out like my mother?

THOMAS

I won’t let this ruin my life.

OLIVE

I won’t let tradition ruin my baby’s life.

THOMAS

She won’t sell it.

OLIVE

I’ll sell it.

THOMAS

I can’t do this. (THOMAS exits)

OLIVE

I can do this. (OLIVE exits)

A die is cast, those Few have voted. Peace is past to these men devoted. They take up arms, they leave their homes, To serve those men of shadowed thrones.

Afar they are led by their masters and fearNumbers on each head and a tag on each earTo come upon some distant land and find some distant foe

With steel handed unto them by whom would never bear their woe.

And on each side of the fields these men know not the other,

But a fragmented apparition yielded by another. To whom do these “honored” men owe this sacrifice? Their own idle Watchers who may under eternity keep, Or those Few of idle words with ironic mockery may weep?

They fall upon the open fields where their God may oversee-

But was He watching when the valiant fell to the Few’s decree?

And in these fields lie the blossoms which decay may bring But who will be the ones to see these flowers spring?

Dyuthi Harikar

Dyuthi Harikar

I have always loved singing and music. I am a strong believer that said love comes from my grandmother, Kathrine Walsh, a first soprano who sang with famous artists of her day and my introduction to singing apart from lullabies on the radio. And, it didn’t hurt that she was a great role model for a young girl–a strong, determined woman who happened to be a state representative. All my life, she’s been singing along to the songs playing on the radio as she watches over my grandfather’s shoulder. He cooks dinner, always something with potatoes (it feels legally required for an Irishman named James Leo Francis Patrick Walsh to eat potatoes with every meal), and as he does her voice carries. Heavy vibrato fills their sunroom in the suburbs of Vermillion, Ohio. I would look around, in awe of how they went from poverty when they were raising my mom to owning such a big house later in life and having enough money to retire. Granted, it probably wasn’t quite as big a house as I remember. As an eight year old even pebbles seem huge.

I vividly remember being confused about how the sliding doors worked to enter the living room from the kitchen, so nervous I would get my finger stuck somehow. I remember the giant piano with ivory keys (a donation from my Grandfather’s former employer, Oberlin College) with Japanese geisha dolls sitting on it (a gift from my mom’s years in Japan). I remember how I would sing with my grandmother as I baked cookies with my grandfather. I could walk just a few steps and see the waves of Lake Erie hitting the cliffside, crashing seemingly to the beat of whichever song she sang.

Then one day, the music stopped. The waves weren’t there anymore, the piano had been donated, and the dolls were tucked away in boxes. They had moved to an apartment closer to town, where they could more easily go to the store and didn’t have to worry about all those stairs in their old house. But I still didn’t understand why, even in their apartment, there was never any music. Everyone else knew why grandma had stopped singing but me.

I could see her right in front of me, smiling and talking, but she wasn’t singing. Twelve year old me didn’t get it.

I could see her right in front of me, smiling and talking, but she wasn’t singing. Twelve year old me didn’t get it.

She had stopped singing, had stopped knitting, and stopped being her. Once, she had knit a dress for me to wear to my Aunt’s wedding. I still have the picture of me in that deep royal blue to match my Aunt’s untraditional gown, holding a pumpkin and grinning beside the women of my family. Now, she wouldn’t even enter her art room filled with yarn and knitting needles, and she would yell at the radio for playing her once favorite songs. She didn’t even want to get out of her comfy chair in front of the TV. She didn’t want the lemon drops, saying she never liked them, and she didn’t like the new reporters on CNN.

My grandparents have since moved into a retirement home together, realizing that their old house was too big for two elderly people to take care of on their own, and even bigger still for a couple where half is unsure of what her breakfast was that morning. The previous apartment had been too far from a hospital, and they thought living right upstairs from nurses may be life saving later on.

The first time I heard it was the summer before Junior year of high school, when I was 16, on the drive up to a farmhouse owned by family friends in Rising Sun, Ohio. I was looking out the window as we pulled out of our driveway in Virginia and my dad said:

“B, grandma has Dementia.”

That certainly made the silence of the eight hour car ride feel much heavier. I thought through everything and connected the dots in my mind–she started changing when I was eleven or twelve, and it took until I was sixteen to even find out. I realized what the whispers were, remembering when conversation would change when I entered the room.

We stayed in Rising Sun for the week and brought our new puppy, Capo, to play in their big pond. We would watch the owners’ daughter, two years old at the time, run around and

around and around the Capo, giggling and yelling “baypo baypo baypo!” The farmhouse was also a wedding venue and an art studio. There was a beautiful gazebo we decided to eat dinner in on the first night.

A giant storm came by, and my dad called me over to the edge of the property. We were, obviously, in a very flat area with mostly farmland and the occasional house or silo popping up. I could see the storm clouds approaching from miles away, never having experienced something quite the same. Overhead, the skies were a bright blue contrasted with wispy white streaks, and yet when I lowered my head I could see a black sky with flashes of lightning hours before it reached us. I sat with a handheld telescope for an hour, just watching as it approached. When it finally hit us, I was given the task of bringing the food out to the gazebo and holding an umbrella over it while I ran. Everyone was laughing and laughing, and laughing even more when I made a stupid mistake. I had noticed that one person, Mrs. Zinzer, had rain blowing on her while she ate. I went over and tried to hold the umbrella over her, but the rain just became more direct due to

the shape of the umbrella and ended up pouring all over her shoulder instead of just spraying her back.

There were also gorgeous indoor spaces, like their beautiful display cases of art and historical artifacts in their office. The same room was filled with leather furniture and books bound by the same material, the carpet a beautiful olive. Their garage was stone and covered in gorgeous ivy on the sides and decorated with golden window details and ornate lighting inside. Also inside, since it was a wedding venue, were lots of chairs and a stage with a sound system for performers. My dad asked if I could sing a specific song for them.

So I spent the entire week learning, in secret, how to sing it and play it on guitar. I looked up the chords and listened to the original recording on repeat in my headphones as I fell asleep. I waited until my mom ran to the store or went to talk to her sister and then practiced in the room I was staying in. At night, I would sneak outside and sit on the swing bench and play for a couple of hours because I knew everyone was asleep inside and it would be the only time I could practice fully.

Then, I asked my grandpa if I could perform a few songs for everyone, as my parents usually try to make me do at family events, and played a few classic rock and folk songs like “House of the Rising Sun’’ and “Simple Man.” Then, I said, “This one is for Poppa and Grandma.” I played the first chord of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” by Peter, Paul, and Mary, shaking with nervousness. But the music took away all of those nerves. I just let go of all of my stress and sang, my fingers strumming along as I did.

I could smell the flowers that covered their yard and taste the lemonade I had just drank. I could feel the warm sun hitting my back and hear the splash of the fountain a few yards away. Each deep breath I took lifted my shoulders up and I felt the slight resistance of my blue, embroidered guitar strap. My hair

brushed the side of my cheek and my fingertips danced across the strings.

When I got to the chorus, I heard a noise. I was slightly surprised, as I had not heard any additional noise when I practiced on my own, and had forgotten where I was, lost in the music.

I opened my eyes to see my grandmother staring at me, singing along and smiling, and my grandfather sitting next to her, crying alongside my mother.

Later that night, my dad pulled me aside and said, “Good job, B.”

My grandfather just hugged me and said, “Thank you.”

It was the first time she had sung in two years.

My grandparents have since made the decision to move my grandma into their retirement home’s “Jameson House,” aka the Dementia specialized care unit. My grandfather still lives in his apartment, but eats every meal he can with his wife. We visit every summer and more recently every christmas time. She now is in the choir there. She has started singing again, but still doesn’t remember much.

Last time we visited, she didn’t know who I was, but I have yet to be prouder of anything in my entire life than giving music back to my grandmother.

Maya Manghat

Maya Manghat

My home was warmly built for me

Posh greens and blues from mother’s brush

Tangled together are the trees

Soft songs being caroled in the hush

We breathe as one, the life and me

The cool air stings our tranquil throats

Tears are frozen, not one breaks free

Snowflakes falling, we wrap our coats

We are selfish, so naive

Absent is our striking blue

Hiding behind bats, tar, steel

We breathe in twice the CO2

Our home is blasted, brutally bloodied

But still, we spew with pride and gloats

Greens replaced with paper money

The hot air burns our throttled throats

We bleed as one and breathe no more,

Our heads are fused with insatiable hunger

Ignoring the unstable, unstoppable gore

My home, our home, safe no longer

Madeline Chang

Fingers pressing into fruit, sweet blood dribbling down my forearms

A trail for the ants that will walk

My body when I sleep

I imagine the fruit in my stomach, sweet, rotting flesh on flesh Seasons change, boundaries blur. At what point will a gardener bring Shovel to my skin And call it soil?

On that day, The sweetest fruit Will grow

From my lips, Bursting forth from the wine-soaked soil where the ants go.

There is a fox screaming.

Screaming, shrieking into the dawn air. The day has not yet begun, and it will not for some time, but he is there.

He yells.

He howls in suburbia, the land he’s not supposed to roam, the habitat that does not fit him.

He’s supposed to be in the woods.

He’s supposed to have animals to hunt, friends and foes to fight.

He’s supposed to have adventure and danger and excitement but he’s here, where there’s none of that.

He screams.

A dog responds with a bark.

The dog wants to be like the fox, but cannot live without his bed and his treats or the love of his owners.

He cannot live like the fox, who does not live like himself.

The dog barks.

The fox screams.

The dog barks.

I’m awake. They’ve woken me up.

I shouldn’t be awake, I shouldn’t be witnessing this. But they’re outside my window, where they shouldn’t be.

The fox screams.

The dog barks.

The fox screams again. His voice cracks under the weight of his reasons, the weight of what his scream cannot say.

Fight me, he begs. Fight me and let me live.

The dog barks. No, he responds. I can not.

The dog has a fence holding him back, and years of bred cowardice stopping him.

The fox has years of not fighting, of traveling suburban landscapes. How long has it been since he hunted the way his ancestors did? How long has it been since he was like them?

The fox screams.

The dog has gone inside.

The fox screams.

The dawn does not respond.

Clara StevensOutside the farm communes, small, hypertrophic blemishes on the face of the earth, and the roads, snaking keloid Frankenstein seams, the Midlands are desolate. The ground, for thousands of square miles, is the same, an endless expanse of bare and beige skin interrupted only by small, living scars of civilization that a giant could pinch between its fingers like a human pinches grains of sand.

It is natural, then, that when some stocky, middle-aged man wakes up and there is only a gray, windless sky and flat, limp dust as far as the eye can see, he is terribly afraid. In fact, he is not all that far from one of those treasured blemishes, even his own farm commune, but the Midlands has a habit of making the world seem much larger than it really is.

The man is so afraid, in fact, that it takes a good long minute to realize that he hasn’t a clue who he is and why he’s here. There are a lot of things he does remember, to be sure. He remembers how to talk, and how to walk. He knows that he’s in the Midlands, although he doesn’t know quite where, because wherever you are in the Midlands, unless you are nearby a road or a farm commune, it all really looks the same. He remembers the practical knowledge. He could count to ten, or one-hundred-thousand, if he wanted to, but being the practical Midland sort, he wasn’t interested in wasting time on such foolish exercises. All the knowledge is still there, but all the memories attached to these facts, who he really is, are gone.

For example, if you were to show him a door, he would certainly know it was a door, but, from his perspective, it would be like the first time he’s ever seen a door. This, of course, isn’t true–he has in fact seen many doors.

Naturally, he is rather upset that he’d forgotten who he was. All the thoughts floating at the surface of his brain seem to be weighed down by anchors, like the pirate boats he had read about as a child (not being able to recall that he had read these as a child, of course, he did not know at what point in time he he had read about those pirate boats, and for all he knew it could have been a few months ago.) Following the memories proves to be fruitless. Whenever he dives in, tries to follow the chain links concatenated to the anchors, his memories, he can only go so far

before the iron rusts to a fine dust. It is a Sisyphean task.

As I said, though, this man is a good and practical Midlander, so he doesn’t linger on these thoughts for long before he gets up with a characteristic decisiveness and heads off in no direction in particular. Certainly, he’s still afraid, but he understands what happened, at least a little. Here is the reason:

As inhospitable as the Midlands may seem, besides some airborne bacteria, who even then are barely getting by, there are creatures that live underground during the daytime, coming out at night, called terafeeks. They are small yet resilient creatures, who breed faster than the government can control. The creatures spend most of their lives in hibernation, but they have a very strong sense of smell–so strong they can scent a brain from a mile away–and whenever they smell a brain, and it is nighttime, they come out to feed.

Now, mind you, the terafeeks are not zombies. It is an unfortunate stereotype that the terafeeks are barbaric things, but they are in truth rather polite. While any neurons would do for them, and they would happily feast on one’s entire brain, and kill their victims slow and painful, they only take the memories of their prey, and even then they keep the important ones, that aren’t something about that victim’s life. In Gnork, where the ground has as many blemishes as a newborn in a radiation zone, they are kept in clinics, trained to erase those unpleasant memories that people would rather not have.

So getting fed on by a terafeek is just what happened to the man, who is now walking due East, in the direction of the sun that is only a vague imprint on the clouds.

Now the question is really how he ended up in the wilder Midlands. The farm communes and roads have fences made of stakes sunk deep in the ground so the terafeeks can’t get in. Ejecting someone out into the wilder Midlands is only ever a punishment. The man is rather displeased with himself for having done something that warrants such punishment, or maybe with his commune unfairly leaving him to the terafeeks. In the gray expanse, anything seems possible, so he decides to be angry at anything, because maybe if anything weren’t possible he wouldn’t be in this wasteland in the first place.

The man keeps on his path with a steady, tirelessly obedient trudge, except there wasn’t much trudging to do on the dry, hard-as-rock dirt. His shoes might as well have been striking on an infinite plane of concrete, the way the soles reverberated through the earth, vibrating the hibernating terafeeks in their underground cubbies.

While he walks, the man wonders who he is (or who he used to be, depending on the way you look at it.) The man knows a good deal about farming, so he figures he is probably a farmer. This is about as far as he gets, though, before he is struck by a sudden pang of hunger. The hunger is the sort that flowers with radiating petals like prickly, fibrous blades of grass, thousands of them, long and spindly and each just the right length to make a perfect circle. This is the nature of the man’s affliction. Not that he would understand this, since he has never seen a flower before, nor a blade of grass. The man huffs, lifting the straps of his overalls with his thumbs, as if to accommodate a stomach that feels bloated with hunger. He doesn’t know this, but that’s something he’s always done whenever he’s felt anxious. I’m no psychologist, but I like to think it’s a reminder for himself. That is, he’s reminding himself, whenever he isn’t quite sure what to do, that he must keep on working, and keep on going, and that’s all there is to it.

The man soon reaches the conclusion that there’s no good in trying to think anymore, because hunger has made his thoughts choppy and disconnected, like a staticky radio station. He focuses on walking instead. One foot, another foot, over and over again, paying blind penance for whatever he did to land him here, or on behalf of whomever put him here.

Not much time passes before the man begins to feel the first throws of thirst, his throat drying like the soil beneath the soles of his sturdy boots. This is not as bad as the all-consuming hole roiling in his stomach, making his body tremble with weakness. It is definitely not as bad as the fatigue. It looms over him like a tsunami closing in over a village, yet to be observed but nonetheless present – inevitable. It has begun to cast a shadow over his consciousness, turning into a muraled dome of cerulean-black. The tsunami eviscerates the buildings and cattle and cattle-people. By the time it rolls away, a hand receding back on

the arm of a sofa chair after squashing a fly, there’s nothing left that won’t soon disintegrate into the tumultuous ocean.

As I predicted, after a few minutes, exhaustion overcomes the man, punctual as always. The man, being human, adamantly refuses the demanding call of slumber, and by sheer willpower persists on walking. Driftwood swept underwater by backwash, imagining that it’s still a floorboard.

The man’s hunger, thirst, and fatigue, which have begun to bleed into each other, mixing into an overall unsatisfactory soup, swallowing his attention whole, is bruised by a low murmur erupting from the vacuum of the Midlands. The sound is so whisper-quiet at first that he initially mistakes it for the wind. He stands still, cocks his head over his shoulder in the direction of the noise, and sure enough, there is a distant, indistinct mass, a round, brown freckle on the cracked earth, marching steadily forward. It is at this moment that the true weight of his vulnerability dawns upon him. He is afraid, because he knows that there isn’t supposed to be anyone out in the wilder Midlands, leaving him with a gut-wrenching conviction that they will hurt him. There is nowhere to go and nowhere to hide. There is nothing trapping him as far as the eye can see, and the only force restraining him is gravity, and yet he is also a caged bird, completely ignorant of the nature of his enclosure and his captors. The man’s flesh itself is a prison.

He has no real choice in the matter but to stand and wait, watching the Earth’s freckle slowly approach. This is especially frustrating, being the practical Midland sort, to not have anything to do, and to feel so afraid without understanding just what you’re afraid of. Minutes pass, and he lies in foolishly, needlessly agonizing wait. The sound crescendos. He wonders if he’ll look stupid, standing there in the middle of the wasteland, ogling the sky, so matte gray and unyieldingly, invariably smooth that it appears to be an unbent plane of plastic that the sun is dimly filtering through. He briefly contemplates fleeing, but it’s too late. They are too near.

Eventually, the mass, which is now near enough it now seems to be a small caravan, is within shouting range of the man. They call out to the man, “Hello!”

The man, with unknowingly characteristic sternness, responds, “Hello, there.” Although he has said this before many times, and his mouth knows how to form words, this is the first time that, in his memory, he has ever spoken. The words leave a strange taste in his mouth.

As the passengers disembark from the caravan, the man is relieved that they appear to be friendly.. The leader extends his hand, and dips his head down in a slight bow, which is customary for him but not so much for the man. Nonetheless, the man understands the invitation of a handshake, and accepts cordially. The leader asks, “What are you doing here?” which ordinarily would come across as rather rude, but in the wilder Midlands is nothing short of considerate.

The man shrugs.

The leader nods knowingly. “Terafeek?” He takes the man’s silence to be a yes. “How long have you been here?”

The man pauses. He opens his mouth to speak, flicking his tongue across his dry lips. In truth, he has no idea how long he was asleep for, or even how long he has been awake for. In the Midlands, the sky is so thickly clouded that the sun is almost impossible to find. The light is dispersed by the clouds, making shadows soft, malleable, and directionless. Sunrise and sundown are brief. He knows he has been awake for less than a day. Finally, he says, “I don’t know.”

The leader nods again. “What is your name?” The words are simple enough, but they carry much weight. The first implication is acknowledgement. He is acknowledging that the man does not have a name. Second, he is reminding the man that he has a name, even if he does not know it. Third, he is signifying acceptance. He is humanizing the man, by indirectly giving him one.

The man, being the practical Midlands type, does not give it all that much thought. He says the first name that comes to mind, and that name is Frank.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, Frank. My name is Daur.” Daur squints up at the sky, and, somehow detecting a hairthin ray of sunlight filtering from the blanket of clouds, determining it to be near sundown. “Dinner is soon. You can eat with

of sun bursting forth from the horizon. She, like Frank, and everyone else on this Earth, has never seen the brilliant show of color the sun puts on every morning and evening, but the woman has heard of it, and dreamed of it (not literally, because there is no dreaming of things that do not exist) many times. She has even heard that during the day, it used to be that the sky was the brightest, most vibrant blue you could possibly imagine, and that the sun cast a golden light on everything richer and more prismatically complex than any artificial light ever could.

Frank remains quiet. There is something chilling about the intimacy of being alone in consciousness with someone else, an experience that until now, in his memory that is so brief but is simultaneously his eternity, his everything, is reserved for the lone self. Because of this, he does not acknowledge the presence of the woman, hoping she in turn will not recognize him. Unfortunately for Frank, without taking her eyes off the expanse above her, which she patiently waits to turn from caliginous murk to pristine beige-gray, the woman senses his wakefulness. She does not turn around, however, perhaps as a courtesy.

When she does, it startles Frank, who has been staring at the fine grain of the dust beneath him, the accumulation of centuries of disintegration, lost and forgotten. Frank is shaken from his grasp on the stable Earth. “I’m sorry,” she says, acutely perceptive of his fear, but this only makes Frank more afraid. The simple knowledge that the woman can read his emotions terrifies him. It is a deep-rooted fear of vulnerability, Midlandish pragmatism.

“It’s okay,” Frank stammers in response. She pats the ground besides her firmly, head still over her shoulder, beckoning Frank to sit next to her. Frank, hands now brown with the particulate vestiges of a bygone era, crawls beside her.

“You’re new,” the woman says. “Name?”

“Frank,” he answers, quicker than he did last time.

“Wendy,” she responds. Wendy pauses. “Terafeek?” She needs only one word to convey what she means; Did a terafeek erase your memory, or do you know who you are? Frank notices that Wendy is a woman of few words, bearing the distinctive Midlandish manner of speaking, unlike the rest of the caravaners.

Frank understands now. He feels a fierce, throbbing pang of empathy for the doomed endeavor. The sacrifices Daur and others still have made in the name of a dream that will never come to fruition.

Their hopes are all wrong. Plants have been extinct for the past 35,000 years. To see a plant is as impossible as rain or snow, impossible as a sunrise or sundown that isn’t monochrome as a black-and-white photo, washed out and the color of crumbling ash. Frank understands this, too, although like with plants, he does not know what rain or snow or black-and-white photos are, and he has only ever heard of sundowns in fairy tales.

Resisting time, and the erosion that its gentle child entropy has marked for the Earth, is futile as resisting sleep. Frank realizes this now, standing on the windswept past and encroached by the volume of the future that never ends, the sky trudging on and on even when it is no longer beautiful. Even the hypertrophic and keloid scars that civilization has scratched onto the shallow surface of the Earth will someday be lost forever, and someday, someday so distant there isn’t a number for how many days it will take, there will be no Earth left at all.

“It’s okay,” Wendy says, reading his mind again, and echoing the words he stuttered at the beginning of the conversation, but they have taken on a whole new meaning. They seem to grow upwards and downwards, like a living crystal breathing oxygen, sinking roots into the soil, single organisms outlasting religions, civilizations, and everything else humans make that is supposed to last forever.

The words grow outward like this, bleeding into the void air like a marker bleeds through a tissue, even though they are over soon enough. Plants can live for a long time; long enough that they dwarf the very existence of humanity. Even the plants are gone now, but plants aren’t sad that they’re gone. The sole preoccupation of plants, was, and is, even past their disappearance, to exist, and this was and is and will be all that ever mattered.

“It’s okay. Don’t mourn when the scars and blemishes fade into a grayscale oblivion. You are a scar right now, one that thinks, and feels and sometimes does good things, and this is what matters.”

Amber Li

I see a stuffed hawk; It stares at me with dead eyes. I wonder if it died in a window strike, Its wings splayed, its body not of Cotton, but flight muscles and Power.

I wonder if it died

Flying forward, flying Fast,

As the passenger pigeon did Into a rain of bullets, Now lying still, its posture perfect, Its feathers pristine. As the ivory-billed woodpecker did Onto its final tree

I saw its red crest of regret. It couldn’t even comprehend The drumming of the chainsaws.

ww

I wonder if it died

With vigor in its breast, the same vigor that Extracts fossils, Those not neatly preserved and displayed, But ground up into oil To run our world To live Our life.

I wonder if its eyes shined Like the Hope Diamond, Its indigo, so adored, Dug up from deep, etched lines we scribbled on the earth in search Of more.

I wonder if it died Quick, quick

As flowers are being crushed under foot, While we coo at the butterflies they sustain.

I wonder if its last breath was deep, deeper than Bottom trawlers scraping the floor of the ocean Deeper than where sea monsters swam And still swim, metallic and artificial.

Siena WilsonI wonder what that hawk had seen, what its species has seen

Soaring on the thermals that our forests of Cement have created, looking down at Unraveled tree rings, incinerated canopies, oceans overflowing, coasts eroding, and creeks

Drying up, flying through Nights that have become gray from too many Spotlights, skies of smog clouds, sunsets

Yellowed and tired-looking.

I wonder if its chest rattled with Unexplainable glee, Thinking the reflection was the shade Of the tree, thinking the future was Bright and golden (so bright it blinds us). It couldn’t hear the clock ticking, the Seconds winding

Like years (how much time do we have?)

I wonder if it died flying forward, flying so Fast

It didn’t see the window

until BAM!

There are a billion buildings, collapsed like Termite mounds, A thousand lights are snuffed like Fireflies. There is a hawk going nowhere And we are all just Bones.

Pity blinded the fool; a weeping disgrace, his life faltered by the anticipation of beauty. under a starlit sky

He walked and wished for the heavens; Subservient to an illegitimate wish.

Jeffrey ChenPlay.

Your hands shake, Rap-tapping on the keys.

Are you—nervous?

No. Play.

Did you practice? Stop.

Try again.

It wasn’t like this at home, Was it?

Look across the theater

It’s empty.

There’s no one here. No lights to blind you. Yet you shake. No, You smile. Too toothy, too fake. Play.

I won’t stop you this time. Lose yourself in the music Let it wrap your mind You’re too far gone So I’ll reel you back in Now nail the ending Great.

Could’ve been better.

Eye the clock. Play.

Check the time–almost done. But you will leave the music here with me, Won’t you?

Is a little part in you sad?

Shove your books in the bag Walk so that your big hair bobs slightly Confidence.

There are people sitting, Smiling–Their eyes are on you. They heard you play Through the walls. Show them your pride, Scholar.

Musician.

Fraud. Rush to the door and Step outside and The cold air fills your nose and Exhale.

Even your empty breath is filled with lies.

Izzy Abhamongkol

Izzy Abhamongkol

- The brain -

How do you explain the human brain? Take it for what it is. A lump of flesh, of neurons, of life. The central cortex of the universe seems a lot less complicated than that of a human being, but perhaps that is just a result of my understanding. This retention of knowledge in my mind (a quite distressful place) leads only to more questions. Of which I am sure there are answers, but it seems… that I am all out of time.

There seems to be a lot of stigma about the people who are placed in facilities like these. I wouldn’t go so far as to disprove all of them entirely, but for the most part, the patients here aren’t even dangerous. At least not to others. Of course, there are the few who are placed in our care for violent tendencies but that remains to be the rare lot of them. When I take vitals in the morning I talk with the older lady from room 115 about what the cafeteria is serving for lunch. We share the same sentiments about how the orange jello is not to be trusted. The seventeen-year-old girl who arrived yesterday has a tiredness about her that seems to weigh down her very soul, but she still smiles and greets me when I walk past her in the hall. However, there is one boy, the patient in room 206. He has been here longer than most, and unlike the others who stay for a while and leave when they get better, he remains. The other nurses call him the “permanent resident”, the doctors just say that he is a special case. I asked once what they meant by that, but no one has given me a straight answer. I ask the other nurses but it seems as if they’re not entirely sure themselves. His name is Jericho. He is a ghostly thing really, far too pale to be considered healthy, almost more specter than boy, with an attitude typical of a nineteen-year-old. Nothing that truly stands out and most certainly nothing to explain why he’s in a place like this. He has a journal that he keeps with him everywhere he goes. I’ve never seen him write in it but I’ve never once seen him without it either. At least until now.

- November 19th -

Just before lights out while the patients take their turns at the showers, the nurses do a routine inspection of the rooms to

Nina Dooleymake sure that nobody has anything that they shouldn’t. The usual shake-down, shoelaces, hoodie strings, utensils from the cafeteria, and pencils or scissors from the activity room. That was when I found it. The small leather-bound book tucked away between the mattress and the frame of the bed, despite the better part of me telling myself that it would be impolite to snoop, the other, louder, more curious part of me, tells myself that by looking through its contents I’m simply doing my job.

Undoing the clasp of the journal I flip to the first page. I suppose I expected something along the lines of grotesque drawings of animal corpses or disfigured human bodies, having pegged him for the quiet sociopathic type, but instead what I found was much more intriguing. Pages upon pages of writing. Ink filling margin to margin with script written in such messy handwriting, I could barely read it. Absorbed in my thoughts I fail to notice when he enters the room until a sharp voice breaks through the silence.

“What are you doing?” The owner of the journal asks accusingly. I do not freeze.

“Nightly inspections,” I say, and it is mostly the truth. His gaze lands on the book I am holding in my hands.

“That’s mine,” He says.

As I hold out the book for him to take, I study his features, his clothing, his body language, looking for anything that reveals to me what exactly this boy has done to warrant being locked up in a place like this. As if by staring hard enough I could read from him his life as simply as you’d read the page of a book. His pain, his anger, his reason for being, I want to understand. But I know people like him. I know that they do not trust easily and I know they have every right not to. Maybe I am selfish for seeing in him more a story than I do a boy, but my curiosity has always been my downfall. However I’ve given him no reason to trust me and whether it be my person or my profession, it’s clear that he doesn’t. So for now I

turn and leave without another word.

- November 22rd -

When I take his vitals in the morning, I tell him that I wanted to be a writer. He scoffs and asks me how the hell I ended up here if my original plan could have led me anywhere else. He’s mocking me, which I deem as progress, so I tell him. I tell him how it was never an option. I tell him how it was either: be a doctor or be a disappointment. I tell him how even as a nurse I still fall into the latter in the darling eyes of my mother.

And for days after we continue to trade a story for a story. He tells me about how he has been left to rot in this place. He tells me about how the doctors say that it’s for his own good. That had he been left alone he would have become a danger to both himself and others. He believes that the doctors are foolish for this. He argues that even here within these walls the only thing that has really made a difference is the quality of food and not for the better. We share the same sentiments about how being here feels like damnation for sins that are no fault of our own. He jokingly says that we might be more alike than I think, laughing at the irony of both of

us sitting together in this room, the only difference being that he is the one that is trapped. He is wrong. He believes that he alone is tied to this place, he does not know that chains exist in many ways that are least of all physical. I laugh it off and move on.

We talk about the upcoming holidays. I ask him about his family. He tells me about his father, and although present, he says it would be easier to hold a meaningful conversation with a salt shaker than with him. So instead I ask about his mother. He tells me that she is beautiful at face value only. That he loves her with all of his heart and hates her with all of his soul. He tells me about how just the sound of her voice made him want to beg for forgiveness. To scream and cry, to throw himself down at her feet and apologize for all the wrong he had not done. To be forgiven for all the faults that were not his own. This I understand far too well. He tells me that in another time she sits him down at the kitchen table and says to him, “Jericho dear, all I want is to help.”

And in this time he believes her with all the trust of a naive child. In this time she stays, even if only for a little while longer. He’s not in much of a mood for talking after that. I give him space.

I make polite conversation with the patients. The general consensus being excitement for the upcoming holiday. Anticipation for the special activities the staff members will prepare. The lady from room 115 tells me that they plan to serve turkey for lunch in lieu of the traditional Thanksgiving feast. I tell her about how I’m leaving for the holidays and that I won’t be back until next week. She says that I’m lucky. I do not feel lucky. I do not tell her about how my week off will be spent in a house that feels less like a home and more like a prison. Bound by nothing more than blood and obligation to people who call themselves my family.

I ask about her own relationship with her family. She tells

me about how much she misses them. She tells me about her husband. How even before death he had been gone from their lives long before his own came to an end. She tells me about her daughter, Lily. She tells me that Lily used to love singing, used to love frilly dresses, and wearing her mother’s jewelry. She tells me how on the first day of school Lily would always linger just a second longer at the entrance, refusing to let go of her mother’s hand. Reminiscing about the days when Lily would climb into her bed when she was too scared to sleep alone. Back when she was young and naive enough to believe in the monsters that lived in her closet. Back when she was young and naive enough to believe that her mother didn’t have monsters of her own. Halfway through speaking her voice catches in her throat, and her eyes begin to water. Cautiously I ask about what had happened to Lily, expecting her to tell me about some horrible accident that resulted in her untimely death, but the answer is both simple and far sadder than I would have thought.

“Only time, dear.” She chuckles and whispers through tears.

Repeating it like both a prayer and a curse, she says again, “Only time.”

It is now that I realize that it’s indeed quite possible to be able to mourn for things that have not died.

In the morning I take vitals for the patients. It seems as if nothing has changed. It feels silly, expecting the world within these walls to have been affected by my absence, however short. I head down the hall to the now-so-familiar room. Knocking twice before I open the door. I step into the room only to find it unnaturally tidy and shockingly empty of all of Jericho’s possessions.

Usually, this means only that a patient has been discharged. Normally a cause for celebration. And I would have been happy for him, really I would, I would have been happy if not for the boarded-up window along with remnants of shattered glass and blood still littering the floor beneath it.

I seem to accumulate regrets in the same way that my windowsill accumulates dust. The doctors said that it was an unfortunate accident. The nurses said, quieter and in confidence, that he was bound to leave, one way or another. Just one more patient gone and yet another to take his place. I find myself back in room 206, a room that is no longer his. Staring at the shattered glass that still litters the wooden floor. Only upon further inspection, does it appear that not all of his possessions have been cleared away. On the sill of the broken window lies a small leather-bound book. I think of it less like an apology and more like an explanation.

However not the one I’d hoped.

Katherine Nurik

in the cornerS of my walls, nearest where the floor would be i will scribble a storm of deformed letters witH sharpie— so i know when i Am nobody my woRds will always be i’ll Pray you remember me for even worse than death Is the dEath of legacy

Of steel, of bones

Of paper, of glass

Of answers to questions

That no one will ask

Of words that flood

Like rivers of blood

They boil and steam

Spilled out in the sun

If you will pour me Out on the concrete

My skin will not shrivel, My eyes will not bleed

So show me the jokes And tell me the lies

Stare down my shirt And poke at my thighs

For I am not human And I am not me; I am a girl; That is all I’m allowed To be

Amelia Vineyard

Amelia Vineyard

Any author, anthropologist, or historian can corroborate the correlation between literature and culture. This is, of course, is the essence of literature as a whole, a sort of creative journal that reflects its societal counterpart, a window into the institutions, norms, and politics of the moment in sophisticated art, a direct contrast to the gauche yet (supposedly) straightforward non-fictitious television, radio, and print news. The strength of literature is founded on the art of human connection, the dexterity of empathy, and human nature’s innate ability to recognize itself even in the most foreign of accounts. In these textual presentations, the essence of culture can be derived and thus serves as one of the most powerful instruments of cultural examination, found even in the most benign of literary works. It is through such facts that we can examine the broad theme of women in literature: timeless grace coupled with bitter conflict. Literature is in itself a key to understanding past civilizations, as well as a tool to help us predict the fate of the female in the future. Through the somewhat more antiquated works of Shakespeare in his renowned Hamlet and Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1879), to Ralph Elli-

Winner of the Richard Rouse Expository Writing Prize

Winner of the Richard Rouse Expository Writing Prize

son’s celebrated novel Invisible Man (1952), and Sylvia Plath’s contemporaneous masterpiece The Bell Jar (1963), the role of women in society can be measured and tracked, forming a scope of both the achievements and difficulties that have plagued women for centuries. Through the thorough exploration of these cultural monuments, we can essentially uncover the mysteries of our heritage. Like an archaeologist digging up relics of a lost time, readers can unearth stories of those long perished.

The most basic element of how women are evaluated in society is, of course, how their male counterparts see and perceive them. There seems to be a ringing consensus in literary works, one that is as domestic as it is tranquil: “Before all else, you are a wife and mother” (Ibsen 64). The delegation of women as wives and mothers is not unexpected, but perhaps its longevity is; A Doll’s House, written in 1879, reflects the same tiresome stereotypes women still combat in 2022, almost 150 years later. Perhaps the true question to be examined in our litany of literary tradition is why this standard has been golden all of these years.

The role of women can be best described in an almost mythical fashion: the man, a courageous and gallant knight, his armor shined to display his own reflection, and the woman, the tempestuous beast, both the dragon and the treasure it defends. If this is too whimsical a comparison, then we can, of course, dilute the tale to the basics of Genesis with Adam, the original “beast” who so generously bequeathed his rib upon Eve, his consequential female counterpart. Eve, in turn, was seduced by the devilish serpent and betrayed Adam and her God, relegating herself, and all her future daughters, to the title of creation’s original sinners as those who betrayed their husbands and their God, but alas, came forth bearing the glowing gift of her indiscretions, the apple (or fig, or however you choose to

interpret it). Perhaps these stories are the basis of female objectification, the idea of women as both curse and blessing, the trophy of men’s most desperate desires: “Do you know, Nora, I have often wished that you might be threatened by some great danger, so that I might risk my life’s blood, and everything for your sake”

(Ibsen 58). Torvald’s confession only further solidifies our understanding of her role as a woman: she is something meant to be taken, to be saved, an object to be acted upon, not an individual of her own. At best, men view women as a thing to be achieved, something to be earned. At worst, a woman is just a symbol of man’s greatest triumphs, quests, and adventures. Nora is an example of the latter; Torvald wishes to save Nora, not because she is in any danger, but because he wants to prove that he can. He wants to wear his wife as a talisman around a neck, a golden metal to signify his dashing attempts to rescue her.

Sarah Sirhandi

Torvald, of course, affirms these theories by referring to Nora as his “treasure,” claiming that her beauty is “all [his] very own” (Ibsen 55). Nora is nothing but a piece of art on his wall, an item he possesses, but does not truly understand. “Treasure” implies that he has somehow won her, that she is a bounty meant to be taken, to be owned, to be admired. Yet, Nora is none of these things; she is neither a masterful piece of art, nor a golden idol resting at the bottom of a perilous cave; she is a woman, she is human, and has worth outside the ideological constraints of her gender.