ollected

Florentin marandache (author and editor) (on Neutrosophics, Plithogenics, Hypersoft Set, and other topics)

nowledge

2022 lobal

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor)

Collected Papers

(on Neutrosophics, Plithogenics, Hypersoft Set, Hypergraphs, and other topics) Volume X

Peer Reviewers:

Akbar Rezaei

Department of Mathematics, Payame Noor University, Tehran, IRAN rezaei@pnu.ac.ir

Xindong Peng

School of Information Science and Engineering, Shaoguan University, Shaoguan, PR CHINA 952518336@qq.com

Muhammad Saeed

Department of Mathematics, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, PAKISTAN muhammad.saeed@umt.edu.pk

Selçuk Topal

Mathematics Department, Bitlis Eren University, TURKEY s.topal@beu.edu.tr

Memet Şahin

Department of Mathematics, Gaziantep University, Gaziantep, TURKEY mesahin@gantep.edu.tr

Muhammad Aslam

King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, SAUDI ARABIA magmuhammad@kau.edu.sa

Florentin Smarandache

(author and editor)

Collected Papers

(on Neutrosophics, Plithogenics, Hypersoft Set, Hypergraphs, and other topics)

Volume X

GLOBAL KNOWLEDGE

Publishing House Miami, United States of America 2022

Editors:

GLOBAL KNOWLEDGE - Publishing House 848 Brickell Ave Ste 950 Miami Florida 33131, United States https://egk.ccgecon.us info@egk.ccgecon.us

ADSUMUS – Scientific and Cultural Society 13, Dimitrie Cantemir St. 410473 Oradea City, Romania https://adsumus.wordpress.com/ ad.sumus@protonmail.com

NSIA Publishing House

Neutrosphic Science International Association https://www.publishing nsia.com/ University of New Mexico, Gallup, United States Universidad Regional Autónoma de los Andes (UNIANDES), Babahoyo, Los Rios, Ecuador

Publishing: Prof. Dan Florin Lazar lazar.danflorin@yahoo.com

Prof. Dr. Maykel Yelandi Leyva Vazquez ub.c.investigacion@uniandes.edu.ec

ISBN 978-1-59973-737 9

Introductory Note

This tenth volume of Collected Papers includes 86 papers in English and Spanish comprising 972 pages mainly on Neutrosophics, Plithogenics, Hypersoft Set, Hypergraphs, but also on various other topics such as Pandemic, COVID-19, Low-Level Laser Therapy, Neurology Disorders, Phytochemistry, Phytomedicine, Plant Medicine, Mannose-Binding Lectins, Moringa Oleifera uses, DNA Transduction, Information Medicine, Ivermectin, Laser LED Pointer, Deep Learning, Edge Computing, Transfer Learning, Ratio estimators, Mean square error, Impact factor, Journal impact factor, Garfield impact factor, improved impact factor, extended impact factor, total impact factor, Blue ocean shift, hospitality, restaurant industry, customer satisfaction, Software development methodology, intelligent control, real time control systems, hardening process, materials, high-frequency currents, robot simulation, graphical user interface, semantic word representation, sentiment classiffication, and so on, written between 2014-2022 by the author alone or in collaboration with the following 105 co-authors (alphabetically ordered) from 26 countries: Abu Sufian, Ali Hassan, Ali Safaa Sadiq, Anirudha Ghosh, Assia Bakali, Atiqe Ur Rahman, Laura Bogdan, Willem K.M. Brauers, Erick González Caballero, Fausto Cavallaro, Gavrilă Calefariu, T. Chalapathi, Victor Christianto, Mihaela Colhon, Sergiu Boris Cononovici, Mamoni Dhar, Irfan Deli, Rebeca Escobar-Jara, Alexandru Gal, N. Gandotra, Sudipta Gayen, Vassilis C. Gerogiannis, Noel Batista Hernández, Hongnian Yu, Hongbo Wang, Mihaiela Iliescu, F. Nirmala Irudayam, Sripati Jha, Darjan Karabašević, T. Katican, Bakhtawar Ali Khan, Hina Khan, Volodymyr Krasnoholovets, R. Kiran Kumar, Manoranjan Kumar Singh, Ranjan Kumar, M. Lathamaheswari, Yasar Mahmood, Nivetha Martin, Adrian Mărgean, Octavian Melinte, Mingcong Deng, Marcel Migdalovici, Monika Moga, Sana Moin, Mohamed Abdel-Basset, Mohamed Elhoseny, Rehab Mohamed, Mohamed Talea, Kalyan Mondal, Muhammad Aslam, Muhammad Aslam Malik, Muhammad Ihsan, Muhammad Naveed Jafar, Muhammad Rayees Ahmad, Muhammad Saeed, Muhammad Saqlain, Muhammad Shabir, Mujahid Abbas, Mumtaz Ali, Radu I. Munteanu, Ghulam Murtaza, Munazza Naz, Tahsin Oner, Gabrijela Popović, Surapati Pramanik, R. Priya, S.P. Priyadharshini, Midha Qayyum, Quang Thinh Bui, Shazia Rana, Akbara Rezaei, Jesús Estupiñán Ricardo, Rıdvan Sahin, Saeeda Mirvakili, Said Broumi, A. A. Salama, Flavius Aurelian Sârbu, Ganeshsree Selvachandran, Javid Shabbir, Shio Gai Quek, Son Hoang Le, Florentin Smarandache, Dragiša Stanujkić, S. Sudha, Taha Yasin Ozturk, Zaigham Tahir, The Houw Iong, Ayse Topal, Alptekin Ulutaș, Maikel Yelandi Leyva Vázquez, Rizha Vitania, Luige Vlădăreanu, Victor Vlădăreanu, Ștefan Vlăduțescu, J. Vimala, Dan Valeriu Voinea, Adem Yolcu, Yongfei Feng, Abd El Nasser H. Zaied, Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas.

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 5

Florentin Smarandache is professor of mathematics at the University of New Mexico and he published over 300 articles and books. He coined the words "neutrosophy" [(French neutre < Latin neuter, neutral, and Greek sophia, skill/wisdom) means knowledge of neutral thought] and its derivatives: neutrosophic, neutrosophication, neutrosophicator, deneutrosophication, deneutrosophicator, etc. He is the founder and developer of neutrosophic set / logic / probability / statistics etc. In 2006 he introduced the degree of dependence/independence between the neutrosophic components T, I, F.

In 2007 he extended the neutrosophic set to Neutrosophic Overset (when some neutrosophic component is > 1), and to Neutrosophic Underset (when some neutrosophic component is < 0), and to Neutrosophic Offset (when some neutrosophic components are off the interval [0, 1], i.e. some neutrosophic component > 1 and some neutrosophic component < 0). Then, similar extensions to respectively Neutrosophic Over/Under/Off Logic, Measure, Probability, Statistics etc.

Then, introduced the Neutrosophic Tripolar Set and Neutrosophic Multipolar Set, also the Neutrosophic Tripolar Graph and Neutrosophic Multipolar Graph.

He then generalized the Neutrosophic Logic/Set/Probability to Refined Neutrosophic Logic/Set/Probability [2013], where T can be split into subcomponents T1, T2, ..., Tp, and I into I1, I2, ..., Ir, and F into F1, F2, ..., Fs, where p+r+s = n ≥ 1. Even more: T, I, and/or F (or any of their subcomponents Tj ,Ik, and/or Fl) could be countable or uncountable infinite sets.

In 2015 he refined the indeterminacy "I", within the neutrosophic algebraic structures, into different types of indeterminacies (depending on the problem to solve), such as I1, I2, , Ip with integer p ≥ 1, and obtained the refined neutrosophic numbers of the form Np = a+b1I1+b2I2+ +bpIp where a, b1, b2, , bp are real or complex numbers, and a is called the determinate part of Np, while for each k in {1, 2, , p} Ik is called the k th indeterminate part of Np. Then consequently he extended the neutrosophic algebraic structures to Refined Neutrosophic Algebraic Structures [or Refined Neutrosophic I Algebraic Structures] (2015), which are algebraic structures based on sets of the refined neutrosophic numbers a+b1I1+b2I2+ +bpIp.

He introduced the (T, I, F) Neutrosophic Structures [2015]. In any field of knowledge, each structure is composed from two parts: a space, and a set of axioms (or laws) acting (governing) on it. If the space, or at least one of its axioms (laws), has some indeterminacy, that structure is a (T, I, F) Neutrosophic Structure. And he extended them to the (T, I, F) Neutrosophic I Algebraic Structures [2015], i.e. algebraic structures based on neutrosophic numbers of the form a+bI, but also having indeterminacy related to the structure space (elements which only partially belong to the space, or elements we know nothing if they belong to the space or not) or indeterminacy related to at least an axiom (or law) acting on the structure space. Then he extended them to Refined (T, I, F) Neutrosophic Refined I Algebraic Structures.

Also, he proposed an extension of the classical probability and the imprecise probability to the 'neutrosophic probability' [1995], that he defined as a tridimensional vector whose components are real subsets of the non standard interval [ 0, 1+] introduced the neutrosophic measure and neutrosophic integral: http://fs.gallup.unm.edu/NeutrosophicMeasureIntegralProbability.pdf and also extended the classical statistics to neutrosophic statistics: http://fs.gallup.unm.edu/NeutrosophicStatistics.pdf

Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 6

Florentin

Neutrosophics

A. Salama, Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache Some Types of Neutrosophic Crisp Sets and Neutrosophic Crisp Relations / 32

Said Broumi, Irfan Deli, Florentin Smarandache Neutrosophic Parametrized Soft Set Theory and Its Decision Making / 40

Said Broumi, Rıdvan Sahin, Florentin Smarandache Generalized Interval Neutrosophic Soft Set and its Decision-Making Problem / 51

Florentin Smarandache, Mumtaz Ali, Munazza Naz, Muhammad Shabir Soft Neutrosophic Left Almost Semigroup / 70

Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache Lower and Upper Soft Interval Valued Neutrosophic Rough Approximations of an IVNSS-Relation / 80

Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache, Mamoni Dhar Rough Neutrosophic Sets / 88

Irfan Deli, Mumtaz Ali, Florentin Smarandache Bipolar Neutrosophic Sets and Their Application Based on Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Problems / 98

Florentin Smarandache Neutrosophic social structures specificities / 104

Said Broumi, Mohamed Talea, Assia Bakali, Florentin Smarandache On Strong Interval Valued Neutrosophic Graphs / 112

Kalyan Mondal, Surapati Pramanik, Florentin Smarandache Rough Neutrosophic Hyper-complex set and its Application to Multi attribute Decision Making / 135

Florentin Smarandache, Maikel Leyva Vázquez

Fundamentos de la lógica y los conjuntos neutrosóficos y su papel en la inteligencia artificial (Fundamentals of neutrosophic logic and sets and their role in artificial intelligence) / 148

Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Rebeca Escobar Jara, Florentin Smarandache Modelos mentales y mapas cognitivos neutrosóficos (Mental models and neutrosophic cognitive maps) / 154

Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Florentin Smarandache

Modelo de Recomendación Basado en Conocimiento y Números SVN (Modelo de Recomendación Basado en Conocimiento y Números SVN) / 163

Contents

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 7

Florentin Smarandache

Lógica neutrosófica refinada n valuada y sus aplicaciones a la física (n-Valued Refined Neutrosophic Logic and Its Applications to Physics) / 170

Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Florentin Smarandache Computación neutrosófica mediante Sympy (Neutrosophic Computing with Sympy) / 175

Florentin Smarandache

Operadores con conjunto neutrosóficos de valor único Oversets, Undersets y Offset / 181

T. Chalapathi, R. V. M. S. S. Kiran Kumar, Florentin Smarandache Neutrosophic Invertible Graphs of Neutrosophic Rings / 185

Florentin Smarandache

Grado de dependencia e independencia de los (sub) componentes de Conjuntos Borrosos y Neutrosóficos / 194

Florentín Smarandache

Tripleta de estructura Neutrosófica y Tripleta de estructura Neutrosófica extendida / 200

Florentín Smarandache

Historia de las Teorías Neutrosóficas y sus Aplicaciones (actualizado) / 207

Erick González Caballero, Florentin Smarandache, Maikel Leyva Vázquez On Neutrosophic Offuninorms / 212

Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Jesús Estupiñan, Florentin Smarandache Neutrosofía en Latinoamérica, avances y perspectivas (Neutrosophics in Latin America, advances and perspectives) / 238

A. A. Salama, Florentin Smarandache Neutrosophic Local Function and Generated Neutrosophic Topology / 245

Florentin Smarandache, Jesús Estupiñán Ricardo, Erick González Caballero, Maikel Yelandi Leyva Vázquez, Noel Batista Hernández Delphi method for evaluating scientific research proposals in a neutrosophic environment / 251

Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Florentin Smarandache Resolucion de sistemas de ecuaciones lineales neutrosóficas mediante computación simbólica (Solving neutrosophic linear equations systems using symbolic computation) / 261

M. Lathamaheswari, S. Sudha, Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache Neutrosophic Perspective of Neutrosophic Probability Distributions and its Application / 267

Florentin Smarandache

Introducción a la Super-Hiper-Álgebra y la Super-Hiper-Álgebra Neutrosófica (Introduction to Super Hyper-Algebra and Neutrosophic Super-Hyper Algebra) / 281

Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 8

Florentin

Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers,

Florentin Smarandache

La Neutro-Geometría y la Anti-Geometría como Alternativas y Generalizaciones de las Geometrías no Euclidianas (Neurometrics and Anti Geometry as Alternatives and Generalizations of Non-Euclidean Geometries) / 287

Saeed Mirvakili, Florentin Smarandache, Akbar Rezaei

On neutro Hv-semigroups / 301

Florentin Smarandache

The SuperHyperFunction and the Neutrosophic SuperHyperFunction / 318

Plithogenics

Florentin Smarandache

Plithogenic Set, an Extension of Crisp, Fuzzy, Intuitionistic Fuzzy, and Neutrosophic Sets - Revisited / 326

Florentin Smarandache

Conjunto plitogénico, una extensión de los conjuntos crisp, difusos, conjuntos difusos intuicionistas y neutrosóficos revisitado / 340

Shazia Rana, Madiha Qayyum, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache, Bakhtawar Ali Khan

Plithogenic Fuzzy Whole Hypersoft Set, Construction of Operators and their Application in Frequency Matrix Multi Attribute Decision Making Technique / 359

Florentin Smarandache

Extension of Soft Set to Hypersoft Set, and then to Plithogenic Hypersoft Set / 376

Mohamed Abdel Basset, Rehab Mohamed, Abd El Nasser H. Zaied, Florentin Smarandache

A Hybrid Plithogenic Decision-Making Approach with Quality Function Deployment for Selecting Supply Chain Sustainability Metrics / 383

Shazia Rana, Muhammad Saeed, Midha Qayyum, Florentin Smarandache

Plithogenic Subjective Hyper Super Soft Matrices with New Definitions & Local, Global, Universal Subjective Ranking Model / 404

Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache

Plithogenic Cognitive Maps in Decision Making / 428

S.P. Priyadharshini, F. Nirmala Irudayam, Florentin Smarandache

Plithogenic Cubic Sets / 441

Sudipta Gayen, Florentin Smarandache, Sripati Jha, Manoranjan Kumar Singh, Said Broumi, Ranjan Kumar

Introduction to Plithogenic Hypersoft Subgroup / 450

Shio Gai Quek, Ganeshsree Selvachandran, Florentin Smarandache, J. Vimala, Son Hoang Le, Quang Thinh Bui, Vassilis C. Gerogiannis

Entropy Measures for Plithogenic Sets and Applications in Multi-Attribute Decision Making / 476

9

Florentin

X

Florentin Smarandache

Introduction to Plithogenic Logic / 493

Florentin Smarandache

Introducción a la Lógica Plitogénica (Introduction to Plitogenic Logic) / 500

Mohamed Abdel Basset, Rehab Mohamed, Florentin Smarandache, Mohamed Elhoseny

A New Decision-Making Model Based on Plithogenic Set for Supplier Selection / 506

Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache, Said Broumi

COVID-19 Decision-Making Model using Extended Plithogenic Hypersoft Sets with Dual Dominant Attributes / 525

Nivetha Martin, R. Priya, Florentin Smarandache

New Plithogenic Sub Cognitive Maps Approach with Mediating Effects of Factors in COVID-19 Diagnostic Model / 537

Akbar Rezaei, T. Oner, T. Katican, Florentin Smarandache, N. Gandotra

A short history of fuzzy, intuitionistic fuzzy, neutrosophic and plithogenic sets / 552

Alptekin Ulutaș, Ayse Topal, Darjan Karabasevic, Dragisa Stanujkic, Gabrijela Popovic, Florentin Smarandache

Prioritization of Logistics Risks with Plithogenic PIPRECIA Method / 570

Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache, R. Priya

Introduction to Plithogenic Sociogram with Preference Representations by Plithogenic Number / 578

Hypersoft Set

Muhammad Saqlain, Muhammad Saeed, Muhammad Rayees Ahmad, Florentin Smarandache

Generalization of TOPSIS for Neutrosophic Hypersoft set using Accuracy Function and its Application / 592

Muhammad Saqlain, Sana Moin, Muhammad Naveed Jafar, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache

Aggregate Operators of Neutrosophic Hypersoft Set / 599

Mujahid Abbas, Ghulam Murtaza, Florentin Smarandache

Basic operations on hypersoft sets and hypersoft point / 612

Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache

Introduction to Combined Plithogenic Hypersoft Sets / 627

Atiqe Ur Rahman, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache and Muhammad Rayees Ahmad

Development of Hybrids of Hypersoft Set with Complex Fuzzy Set, Complex Intuitionistic Fuzzy set and Complex Neutrosophic Set / 635

Atiqe Ur Rahman, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache

Convex and Concave Hypersoft Sets with Some Properties / 655

Adem Yolcu, Florentin Smarandache, Taha Yasin Ozturk

Intuitionistic Fuzzy Hypersoft Sets / 667

X 10

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor)

Collected Papers,

Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X

Atiqe Ur Rahman, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache

A theoretical and analytical approach to the conceptual framework of convexity cum concavity on fuzzy hypersoft sets with some generalized properties / 679

Muhammad Ihsan, Muhammad Saeed, Atiqe Ur Rahman, Florentin Smarandache

Multi Attribute Decision Support Model Based on Bijective Hypersoft Expert Set / 695

Hypergraphs

Ali Hassan, Muhammad Aslam Malik, Florentin Smarandache

Regular and Totally Regular Interval Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs / 716

Muhammad Aslam Malik, Ali Hassan, Said Broumi, Assia Bakali, Mohamed Talea, Florentin Smarandache Isomorphism of Single Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs / 729

Muhammad Aslam Malik, Ali Hassan, Said Broumi, Assia Bakali, Mohamed Talea, Florentin Smarandache Isomorphism of Interval Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs / 751

Muhammad Aslam Malik, Ali Hassan, Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache

Regular Bipolar Single Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs / 777

Florentin Smarandache, Ali Hassan

Regular Single Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs / 783

Florentin Smarandache, Nivetha Martin

Plithogenic n-Super Hypergraph in Novel Multi-Attribute Decision Making / 789

Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache Concentric Plithogenic Hypergraph based on Plithogenic Hypersoft sets - A Novel Outlook / 811

Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache, Said Broumi

PROMTHEE Plithogenic Pythagorean Hypergraphic Approach in Smart Materials Selection / 825

Miscellanea

Monika Moga, Gavrilă Calefariu, Florentin Smarandache, Flavius Aurelian Sârbu, Laura Bogdan

Determining the Duration of R&D Processes through Monte Carlo Simulation / 835

Florentin Smarandache, Ștefan Vlăduțescu Towards a Practical Communication Intervention / 840

Victor Vladareanu, Radu I. Munteanu, Ali Mumtaz, Florentin Smarandache, Luige Vladareanu

The optimization of intelligent control interfaces using Versatile Intelligent Portable Robot Platform / 852

Luige Vlădăreanu, Florentin Smarandache, Mumtaz Ali, Victor Vlădăreanu, Mingcong Deng

Robot System Identification using 3D Simulation Component Applied on VIPRO Platform / 860

11

Florentin

Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache

What we can do to save humanity in the coming era of global eavesdroppers (or the social innovation way to solve collective action problem) / 866

Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache

The World Within Us (Or A Sketch of Consciousness Space Beyond Freudian Mental Model and Implications to Socio-Economics Modeling and Integrative Cancer Therapy) / 871

Luige Vladareanu, Victor Vladareanu, Hongnian Yu, Hongbo Wang, Florentin Smarandache

Robot Advanced Intelligent Control developed through Versatile Intelligent Portable Platform / 883

Victor Vladareanu, Sergiu Boris Cononovici, Marcel Migdalovici, Hongbo Wang, Yongfei Feng, Florentin Smarandache

Application for Position and Load Reference Generation of a Simulated Mechatronic Chain / 889

Luige Vladareanu, Mihaiela Iliescu, Victor Vladareanu, Alexandru Gal, Octavian Melinte, Florentin Smarandache, Adrian Margean

Improvement of the Material's Mechanical Characteristics using Intelligent Real Time Control Interfaces in HFC Hardening Process / 895

Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache

On the Efficacy of Moringa Oleifera as Anticancer Treatment: A Literature Survey / 901

Darjan Karabašević, Florentin Smarandache

Selection of Optimal Software Development Methodology Based on Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment Method / 906

Dragisa Stanujkic, Darjan Karabasevic, Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas, Florentin Smarandache, Fausto Cavallaro

An Approach to Determining Customer Satisfaction in Traditional Serbian Restaurants / 922

Dragisa Stanujkic, Darjan Karabasevic, Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas, Florentin Smarandache, Willem K.M. Brauers

A Bipolar Fuzzy Extension of the MULTIMOORA Method / 933

Mihaela Colhon, Florentin Smarandache, Dan Valeriu Voinea

Entropy of Polysemantic Words for the Same Part of Speech / 949

Volodymyr Krasnoholovets, Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache, Rizha Vitania, The Houw Iong

A Short Remark on Multipurpose Laser Therapy “Helios” in Ukraine and its Potential Application for Treatment of Neurology Disorders / 957

Florentin Smarandache

Improved, extended, and total impact factor of a journal / 962

and editor) Collected Papers, X 12

Florentin Smarandache (author

Abu Sufian, Anirudha Ghosh, Ali Safaa Sadiq, Florentin Smarandache

A Survey on Deep Transfer Learning to Edge Computing for Mitigating the COVID-19 Pandemic / 966

Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache

A Review of the Evidences Showing that Certain Plant Medicines can be Useful for Novel Corona Virus Treatment / 977

Zaigham Tahir, Hina Khan, Muhammad Aslam, Javid Shabbir, Yasar Mahmood, Florentin Smarandache

Neutrosophic ratio-type estimators for estimating the population mean / 983

Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache

Remark on Neutrosophy Perspective on Blue Ocean Shift / 994

Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache, Rizha Vitania

A Possible Application of DNA Transduction Experiment: Information Medicine for Pedestrians” / 997

Collected Papers, X 13

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor)

List of Countries

SOUTH AFRICA (1)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (1)

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES (1)

SAUDI ARABIA (1)

BELGIUM (1)

UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN (1)

PR CHINA (4)

CUBA (1) CZECH REPUBLIC (1)

ECUADOR (4) EGYPT (4) GREECE (1) INDIA (19)

INDONESIA (3) IRAN (2) ITALIA (1) JAPAN (1) LITHUANIA (3)

MALAYSIA (2) MOROCCO (3)

PAKISTAN (21)

ROMÂNIA (16)

SERBIA (3) TURKEY (8) UKRAINE (1)

SR VIETNAM (1)

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 14

List of Authors

A

Abu Sufian

Department of Computer Science, University of Gour Banga, Malda, INDIA sufian.csa@gmail.com

Ali Hassan

Department of Mathematics, International Islamic University, Islamabad, PAKISTAN alihassan.iiui.math@gmail.com

Ali

Safaa Sadiq

Wolverhampton Cyber Research Institute, School of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, UNITED KINGDOM

Anirudha Ghosh

Department of Computer Science, University of Gour Banga, Malda, INDIA

Assia Bakali

Ecole Royale Navale, Boulevard Sour Jdid, Casablanca, MOROCCO assiabakali@yahoo.fr

Atiqe

Ur Rahman

Department of Mathematics, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, PAKISTAN aurkhb@gmail.com

B

Laura

Bogdan

Babes Bolyai University, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Cluj Napoca, ROMÂNIA eby_laura99@yahoo.com

Willem K.M. Brauers

Faculty of Business and Economics, Department of Economics, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, BELGIUM willem.brauers@uantwerpen.be

C

Erick González Caballero

Asociación Latinoamericana de Ciencias Neutrosóficas, La Habana, CUBA erickgc@yandex.com

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 15

Fausto Cavallaro

Department of Economics, Università degli Studi del Molise, Via Francesco De Sanctis, 1, Campobasso, ITALIA cavallaro@unimol.it

Gavrilă Calefariu

Transilvania University, Faculty of Technological Engineering and Industrial Management, Brașov, ROMÂNIA bgcalefariu@unitbv.ro

T.Chalapathi

Department of Mathematics, Sree Vidyanikethan Eng. College, Tirupati, INDIA chalapathi.tekuri@gmail.com

Victor Christianto

Malang Institute of Agriculture (IPM), Malang, INDONESIA victorchristianto@gmail.com

Mihaela Colhon

Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Sciences, University of Craiova, 200585 Craiova, ROMÂNIA mcolhon@inf.ucv.ro

Sergiu Boris Cononovici

Robotics and Mechatronics Dept., Institute of Solid Mechanics of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, ROMÂNIA cononovici@imsar.bu.edu

D

Mamoni Dhar

Department of Mathematics, Science College, Kokrajhar, Assam, INDIA

Irfan Deli

Muallim Rifat Faculty of Education, Aralik University, Kilis, TURKEY irfandeli@kilis.edu.tr

E

Rebeca Escobar-Jara

Universidad de Guayaquil, Facultad de Comunicación Social, Guayaquil, ECUADOR

G

Alexandru Gal

Robotics and Mechatronics Department, Romanian Academy, Institute of Solid Mechanics, București, ROMÂNIA galexandru2003@yahoo.com

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 16

N.Gandotra

Yogananda School of AI, Comput. Data Sci., Shoolini University, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, INDIA neerajgandotra@shooliniuniversity.com

Sudipta Gayen

National Institute of Technology Jamshedpur, INDIA sudi23dipta@gmail.com

Vassilis C. Gerogiannis

Department of Digital Systems, University of Thessaly, Larissa, GREECE vgerogian@uth.gr H

Noel Batista Hernández

Universidad de Guayaquil, ECUADOR noelbatista1965@gmail.com

Hongnian Yu

School of Computer Science and Network Security, Dongguan University of Technology, Guangdong, PR CHINA yu61150@ieee.org

Hongbo Wang

Parallel Robot and Mechatronic System Laboratory of Hebei Province, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, PR CHINA hongbo_w@ysu.edu.cn I

Mihaiela Iliescu

Robotics and Mechatronics Department, Romanian Academy, Institute of Solid Mechanics, București, ROMÂNIA iliescumihaiela7@gmail.com

F.Nirmala Irudayam

Department of Mathematics, Nirmala College for Women, INDIA nirmalairudayam@ymail.com J

Sripati Jha

National Institute of Technology Jamshedpur, INDIA

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 17

Darjan Karabašević

Faculty of Applied Management, Economics and Finance, Business Academy University, Belgrade, SERBIA darjan.karabasevic@mef.edu.rs

T.Katican

Department of Mathematics, Ege University, 35100 Izmir, TURKEY tugcektcn@gmail.com

Bakhtawar

Ali Khan

Kashana e Iqbal, Sialkot, PAKISTAN bakhtawar_1987@hotmail.com

Hina Khan

Department of Statistics, Government College University, Lahore, PAKISTAN hinakhan@gcu.edu.pk

Volodymyr Krasnoholovets

Principal Investigator and Inventor, Indra Scientific, Kiev, UKRAINE

R.Kiran Kumar

Department of Mathematics, S.V. University, Tirupati, INDIA kksaisiva@gmail.com

Manoranjan Kumar Singh

Magadh University, Bodh Gaya, INDIA

Ranjan Kumar

Jain Deemed to be University, Jayanagar, Bengaluru, INDIA ranjank.nit52@gmail.com

L

M.Lathamaheswari

Department of Mathematics, Hindustan Institute of Technology & Science, Chennai, INDIA lathamax@gmail.com

M

Yasar Mahmood

Department of Statistics, Government College University, Lahore, PAKISTAN syed.yasar@gcu.edu.pk

Nivetha Martin

Department of Mathematics, Arul Anandar College (Autonomous), Karumathur, Tamil Nadu, INDIA nivetha.martin710@gmail.com

K

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 18

Adrian Mărgean

Scientific Research Department, Top Ambient, ROMÂNIA office@rugvity.ro

Octavian Melinte

Robotics and Mechatronics Department, Romanian Academy, Institute of Solid Mechanics, București, ROMÂNIA octavian.melinte@imsar.ro

Mingcong Deng

The Graduate School of Engineering, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Tokyo, JAPAN deng@cc.tuat.ac.jp

Marcel Migdalovici

Robotics and Mechatronics Dept., Institute of Solid Mechanics of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, ROMÂNIA migdal@imsar.bu.edu.ro

Monika Moga

Transilvania University, Faculty of Technological Engineering and Industrial Management, Brașov, ROMÂNIA amoga_monika@yahoo.com

Sana Moin

Lahore Garrison University, DHA Phase VI, Sector C, Lahore, 54000, PAKISTAN moinsana64@gmail.com

Mohamed Abdel-Basset

Department of Operations Research, Faculty of Computers and Informatics, Zagazig University, Sharqiyah, EGYPT analyst_mohamed@yahoo.com

Mohamed Elhoseny

College of Computer Information Technology, American University in the Emirates, Dubai, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Rehab Mohamed

Faculty of Computers and Informatics, Zagazig University, Zagazig, EGYPT

Mohamed Talea

Laboratory of Information processing, Faculty of Science Ben M’Sik, University Hassan II, Casablanca, MOROCCO taleamohamed@yahoo.fr

Kalyan Mondal

Department of Mathematics, Jadavpur University, West Bengal, INDIA kalyanmathematic@gmail.com

Muhammad Aslam

Department of Statistics, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, SAUDI ARABIA aslam_ravian@hotmail.com

Muhammad Aslam Malik

Department of Mathematics, University of Punjab, Lahore, PAKISTAN aslam@math.pu.edu.pk

Muhammad Ihsan

Department of Mathematics, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, PAKISTAN mihkhb@gmail.com

Florentin Smarandache

Collected Papers, X 19

(author and editor)

Muhammad Naveed

Jafar

Lahore Garrison University, DHA Phase VI, Sector C, Lahore, PAKISTAN naveedjafar@lgu.edu.pk

Muhammad Rayees Ahmad

Department of Mathematics, University of Management and Techology, Lahore, PAKISTAN rayeesmalik.ravian@gmail.com

Muhammad Saeed

Department of Mathematics, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, PAKISTAN muhammad.saeed@umt.edu.pk

Muhammad

Saqlain

Lahore Garrison University, DHA Phase VI, Sector C, Lahore, 54000, PAKISTAN msaqlain@lgu.edu.pk

Muhammad Shabir

Department of Mathematics, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, PAKISTAN mshabirbhatti@yahoo.co.uk

Mujahid Abbas

Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics,, University of Pretoria, Lynnwood Road, Pretoria, SOUTH AFRICA abbas.mujahid@gmail.com

Mumtaz Ali

Department of Mathematics, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, PAKISTAN mumtazali770@yahoo.com

Radu I. Munteanu

Technical University of Cluj Napoca, 15 C tin Daicoviciu, Cluj Napoca, ROMÂNIA radu.munteanu@mas.utcluj.ro

Ghulam Murtaza

Department of Mathematics, University of Management Technology, Lahore, PAKISTAN ghulammurtaza@umt.edu.pk

N

Munazza Naz

Department of Mathematical Sciences, Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi, PAKISTAN munazzanaz@yahoo.com

O

Tahsin Oner

Department of Mathematics, Ege University, 35100 Izmir, TURKEY tahsin.oner@ege.edu.tr

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 20

Gabrijela Popović

Faculty of Applied Management, Economics and Finance, University Business Academy in Novi Sad, SERBIA gabrijela.popovic@mef.edu.rs

Surapati Pramanik

Department of Mathematics, Nandalal Ghosh B.T. College, Panpur, West Bengal, INDIA sura_pati@yahoo.co.in

R.Priya

Department of Mathematics, PKN Arts College, Madurai, INDIA iampriyaravi@gmail.com

S.P. Priyadharshini

Department of Mathematics, Nirmala College for Women, INDIA priyadharshini125@gmail.com

Q

Midha Qayyum

COMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore Campus, Department of Mathematics, Lahore, PAKISTAN mqayyum17@gmail.com

Quang Thinh Bui

Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, VŠB Technical University of Ostrava, Ostrava, CZECH REPUBLIC qthinhbui@gmail.com

R

Shazia Rana

Dept. Math, University of Management and Technology, Johar Town Campus, Lahore, PAKISTAN shaziaranams@gmail.com

Akbara Rezaei

Department of Mathematics, Payame Noor University, Tehran, IRAN rezaei@pnu.ac.ir

Jesús Estupiñán Ricardo

Universidad Regional Autónoma de Los Andes, ECUADOR ub.c.investigacion@uniandes.edu.ec

Rıdvan Sahin

Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Ataturk University, Erzurum, TURKEY mat.ridone@gmail.com

P

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 21

Saeeda Mirvakili

Department of Mathematics, Payame Noor University, Tehran, IRAN

Said Broumi

Laboratory of Information Processing, Faculty of Science Ben M’Sik, University Hassan II, Casablanca, MOROCCO broumisaid78@gmail.com

A. A. Salama

Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Faculty of Sciences, Port Said University, EGYPT drsalama44@gmail.com

Flavius Aurelian Sârbu

Transilvania University, Faculty of Technological Engineering and Industrial Management, Brașov, ROMÂNIA dsflavius@unitbv.ro

Ganeshsree Selvachandran

Department of Actuarial Science and Applied Statistics, Faculty of Business & Information Science, UCSI University, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA Ganeshsree@ucsiuniversity.edu.my

Javid Shabbir

Department of Statistics, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, PAKISTAN js@qau.edu.pk

Shio Gai Quek

Department of Actuarial Science and Applied Statistics, Faculty of Business & Information Science, UCSI University, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA queksg@ucsiuniversity.edu.my

Son Hoang Le

Faculty of Information Technology, Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology (HUTECH), Ho Chi Minh City, SR VIETNAM lh.son84@hutech.edu.vn

Florentin Smarandache

Dept. Math. And Sciences, University of New Mexico Gallup, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA smarand@unm.edu

Dragiša Stanujkić

Technical Faculty in Bor, University of Belgrade, Vojske Jugoslavije 12, 19210, Bor, SERBIA dstanujkic@tfbor.bg.ac.rs

S.Sudha

Department of Mathematics, Hindustan Institute of Technology & Science, Chennai, INDIA sudha.aarpitha@gmail.com

S

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 22

Taha Yasin Ozturk

Department of Mathematics, Kafkas University, Kars, TURKEY

Zaigham Tahir

Department of Statistics, Government College University, Lahore, PAKISTAN zghmscholar@gmail.com

The Houw Iong

Professor in Physics, Institut Teknologi Bandung and Telkom University, Bandung, INDONESIA

Ayse Topal

Nigde Omer Halisdemir University, 51240 Nigde, TURKEY U

Alptekin Ulutaș

Sivas Cumhuriyet University, Sivas, TURKEY aulutas@cumhuriyet.edu.tr V

Maikel

Yelandi Leyva Vázquez

Universidad Politécnica Salesiana de Guayaquil, ECUADOR mleyvaz@gmail.com

Rizha Vitania

Faculty of Medicine, Brawijaya University, INDONESIA

Luige Vlădăreanu

Romanian Academy, Institute of Solid Mechanics, București, ROMÂNIA luige.vladareanu@vipro.edu.ro

Victor Vlădăreanu

Romanian Academy, Institute of Solid Mechanics, București, ROMÂNIA victor.vladareanu@imsar.ro

Ștefan Vlăduțescu

University of Craiova, Faculty of Letters, Department of Journalism and Communication, Craiova, ROMÂNIA stefan.vladutescu@yahoo.com

J.Vimala

Department of Mathematics, Alagappa University, Karaikudi, Tamil Nadu 630003, INDIA vimaljey@alagappauniversity.ac.in

Dan Valeriu Voinea

Faculty of Letters, University of Craiova, 200585 Craiova, ROMÂNIA

T

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 23

Adem Yolcu

Department of Mathematics, Kafkas University, Kars, TURKEY

Yongfei Feng

Parallel Robot and Mechatronic System Laboratory of Hebei Province, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, PR CHINA yf_feng@126.com Z

Abd

El Nasser H. Zaied

Department of Operations Research, Faculty of Computers and Informatics, Zagazig University, Sharqiyah, EGYPT

Edmundas

Kazimieras Zavadskas

Institute of Sustainable Construction, Labor of Operational Research, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilnius, LITHUANIA

edmundas.zavadskas@vgtu.lt

Y

Florentin Smarandache (author and

Collected Papers, X 24

editor)

NEUTROSOPHICS

1. A.A. Salama, Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache (2014). Some Types of Neutrosophic Crisp Sets and Neutrosophic Crisp Relations. I.J. Information Engineering and Electronic Business, 9

2. Said Broumi, Irfan Deli, Florentin Smarandache (2014). Neutrosophic Parametrized Soft Set Theory and Its Decision Making. International Frontier Science Letters 1(1), 11

3. Said Broumi, Rıdvan Sahin, Florentin Smarandache (2014). Generalized Interval Neutrosophic Soft Set and its Decision Making Problem. Journal of New Results in Science 7, 29 47

4. Florentin Smarandache, Mumtaz Ali, Munazza Naz, Muhammad Shabir (2014). Soft Neutrosophic Left Almost Semigroup. SISOM & ACOUSTICS 2014, Bucharest 22 23 May, 140 149

5. Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache (2014). Lower and Upper Soft Interval Valued Neutrosophic Rough Approximations of an IVNSS Relation. SISOM & ACOUSTICS 2014, Bucharest 22 23 May, 204 211

6. Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache, Mamoni Dhar (2014). Rough Neutrosophic Sets. Italian Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 32, 493 502

7. Irfan Deli, Mumtaz Ali, Florentin Smarandache (2015). Bipolar Neutrosophic Sets and Their Application Based on Multi Criteria Decision Making Problems. Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Advanced Mechatronic Systems, Beijing, China, 249 254

8. Florentin Smarandache (2015). Neutrosophic social structures specificities. Social Sciences and Education Research Review 2(1), 3 10

9. Said Broumi, Mohamed Talea, Assia Bakali, Florentin Smarandache (2016). On Strong Interval Valued Neutrosophic Graphs. Critical Review XII, 49 71

10. Kalyan Mondal, Surapati Pramanik, Florentin Smarandache (2016). Rough Neutrosophic Hyper complex set and its Application to Multi attribute Decision Making Critical Review XIII, 111 128

11. Florentin Smarandache, Maikel Leyva Vázquez (2018). Fundamentos de la lógica y los conjuntos neutrosóficos y su papel en la inteligencia artificial (Fundamentals of neutrosophic logic and sets and their role in artificial intelligence). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 1, 16 21

12. Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Rebeca Escobar Jara, Florentin Smarandache (2018). Modelos mentales y mapas cognitivos neutrosóficos (Mental models and neutrosophic cognitive maps. Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 1, 22 28

13. Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Florentin Smarandache (2018). Modelo de Recomendación Basado en Conocimiento y Números SVN (Modelo de Recomendación Basado en Conocimiento y Números SVN). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 1, 29 35

14. Florentin Smarandache (2018). Lógica neutrosófica refinada n valuada y sus aplicaciones a la física (n Valued Refined Neutrosophic Logic and Its Applications to Physics). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 2, 3-8

15. Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Florentin Smarandache (2018). Computación neutrosófica mediante Sympy (Neutrosophic Computing with Sympy). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 3, 16 21

16. Florentin Smarandache (2018). Operadores con conjunto neutrosóficos de valor único Oversets, Undersets y Offset. Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 4, 1-4

17. T. Chalapathi, R. V. M. S. S. Kiran Kumar, Florentin Smarandache (2018). Neutrosophic Invertible Graphs of Neutrosophic Rings. In: Florentin Smarandache, Surapati Pramanik (Editors), New Trends in Neutrosophic Theory and Applications II, 209 217

18. Florentin Smarandache (2019). Grado de dependencia e independencia de los (sub) componentes de Conjuntos Borrosos y Neutrosóficos. Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 5, 1-6

19. Florentín Smarandache (2019). Tripleta de estructura Neutrosófica y Tripleta de estructura Neutrosófica extendida. Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 7, 1-7

List of Papers

Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 25

Florentin

20. Florentín Smarandache (2019). Historia de las Teorías Neutrosóficas y sus Aplicaciones (actualizado). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 8, 53 57

21. Erick González Caballero, Florentin Smarandache, Maikel Leyva Vázquez (2019). On Neutrosophic Offuninorms. Symmetry 11, 1136. DOI: 10.3390/sym11091136

22. Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Jesús Estupiñan, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Neutrosofía en Latinoamérica, avances y perspectivas (Neutrosophics in Latin America, advances and perspectives). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 14, 1-7

23. A.A. Salama, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Neutrosophic Local Function and Generated Neutrosophic Topology. Neutrosophic Knowledge 1, 1-6

24. Florentin Smarandache, Jesús Estupiñán Ricardo, Erick González Caballero, Maikel Yelandi Leyva Vázquez, Noel Batista Hernández (2020). Delphi method for evaluating scientific research proposals in a neutrosophic environment. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 34{Special Issue: Social Neutrosophy in Latin America}, 204 213

25. Maikel Leyva Vázquez, Florentin Smarandache (2021). Resolucion de sistemas de ecuaciones lineales neutrosóficas mediante computación simbólica (Solving neutrosophic linear equations systems using symbolic computation). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 15, 41 46

26. M. Lathamaheswari, S. Sudha, Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache (2021). Neutrosophic Perspective of Neutrosophic Probability Distributions and its Application. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 17(2), 11 14

27. Florentin Smarandache (2022). Introducción a la Super Hiper Álgebra y la Super Hiper Álgebra Neutrosófica (Introduction to Super Hyper Algebra and Neutrosophic Super Hyper Algebra). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 20, 1-6

28. Florentin Smarandache (2022). La Neutro Geometría y la Anti Geometría como Alternativas y Generalizaciones de las Geometrías no Euclidianas (Neurometrics and Anti Geometry as Alternatives and Generalizations of Non Euclidean Geometries). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 20, 91-104

29. Saeed Mirvakili, Florentin Smarandache, Akbar Rezaei (2022). On neutro Hv semigroups. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 42(3), 1289 1299. DOI: 10.3233/JIFS 202559

30. Florentin Smarandache (2022). The SuperHyperFunction and the Neutrosophic SuperHyperFunction Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 49, 594 600

PLITHOGENICS

1. Florentin Smarandache (2018) Plithogenic Set, an Extension of Crisp, Fuzzy, Intuitionistic Fuzzy, and Neutrosophic Sets - Revisited. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 21, 153 166

2. Florentin Smarandache (2018). Conjunto plitogénico, una extensión de los conjuntos crisp, difusos, conjuntos difusos intuicionistas y neutrosóficos revisitado. Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 1, 3-9

3. Shazia Rana, Madiha Qayyum, Muhammad Saeed, F. Smarandache, Bakhtawar Ali Khan (2019). Plithogenic Fuzzy Whole Hypersoft Set, Construction of Operators and their Application in Frequency Matrix Multi Attribute Decision Making Technique. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 28, 34 50

4. Florentin Smarandache (2019). Extension of Soft Set to Hypersoft Set, and then to Plithogenic Hypersoft Set. Octogon Mathematical Magazine 27(1), 413 418

5. Mohamed Abdel Basset, Rehab Mohamed, Abd El Nasser H. Zaied, Florentin Smarandache (2019). A Hybrid Plithogenic Decision Making Approach with Quality Function Deployment for Selecting Supply Chain Sustainability Metrics. Symmetry 11, 903. DOI: 10.3390/sym11070903

6. Shazia Rana, Muhammad Saeed, Midha Qayyum, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Plithogenic Subjective Hyper Super Soft Matrices with New Definitions & Local, Global, Universal Subjective Ranking Model. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 6(2), 56 79

7. Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Plithogenic Cognitive Maps in Decision Making. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 9(1), 9 21

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 26

8. S.P. Priyadharshini, F. Nirmala Irudayam, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Plithogenic Cubic Sets. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 11(1), 30 38

9. Sudipta Gayen, Florentin Smarandache, Sripati Jha, Manoranjan Kumar Singh, Said Broumi, Ranjan Kumar (2020). Introduction to Plithogenic Hypersoft Subgroup. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 33, 208 233

10. Shio Gai Quek, Ganeshsree Selvachandran, Florentin Smarandache, J. Vimala, Son Hoang Le, Quang Thinh Bui, Vassilis C. Gerogiannis (2020). Entropy Measures for Plithogenic Sets and Applications in Multi Attribute Decision Making. Mathematics 8, 965. DOI: 10.3390/math8060965

11. Florentin Smarandache (2021). Introduction to Plithogenic Logic. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 45, 1-7

12. Florentin Smarandache (2021). Introducción a la Lógica Plitogénica (Introduction to Plitogenic Logic). Neutrosophic Computing and Machine Learning 18, 1-6

13. Mohamed Abdel Basset, Rehab Mohamed, Florentin Smarandache, Mohamed Elhoseny (2021). A New Decision Making Model Based on Plithogenic Set for Supplier Selection. Computers, Materials & Continua 66(3), 2751- 2769. DOI:10.32604/cmc.2021.013092

14. Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache, Said Broumi (2021). COVID 19 Decision Making Model using Extended Plithogenic Hypersoft Sets with Dual Dominant Attributes. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 13(2), 75 86

15. Nivetha Martin, R. Priya, Florentin Smarandache (2021). New Plithogenic Sub Cognitive Maps Approach with Mediating Effects of Factors in COVID 19 Diagnostic Model. Journal of Fuzzy Extension and Applications 2(1) 1 15

16.Akbar Rezaei, T. Oner, T. Katican, Florentin Smarandache, N. Gandotra (2022). A short history of fuzzy, intuitionistic fuzzy, neutrosophic and plithogenic sets. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 18(1), 99 116

17. Alptekin Ulutaș, Ayse Topal, Darjan Karabasevic, Dragisa Stanujkic, Gabrijela Popovic, Florentin Smarandache. (2022). Prioritization of Logistics Risks with Plithogenic PIPRECIA Method. In C. Kahraman et al. (Eds.): INFUS 2021, LNNS 308, 663 670. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030 85577 2_78

18. Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache, R. Priya (2022). Introduction to Plithogenic Sociogram with Preference Representations by Plithogenic Number. Journal of Fuzzy Extension and Applications 3(1) 96 108

HYPERSOFT SET

1. Muhammad Saqlain, Muhammad Saeed, Muhammad Rayees Ahmad, Florentin Smarandache (2019). Generalization of TOPSIS for Neutrosophic Hypersoft set using Accuracy Function and its Application. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 27, 131 137

2. Muhammad Saqlain, Sana Moin, Muhammad Naveed Jafar, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Aggregate Operators of Neutrosophic Hypersoft Set. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 32, 294 306

3. Mujahid Abbas, Ghulam Murtaza, Florentin Smarandache, Basic operations on hypersoft sets and hypersoft point (2020). Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 35, 407 421

4. Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Introduction to Combined Plithogenic Hypersoft Sets. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 35, 503 510

5. Atiqe Ur Rahman, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache and Muhammad Rayees Ahmad (2020). Development of Hybrids of Hypersoft Set with Complex Fuzzy Set, Complex Intuitionistic Fuzzy set and Complex Neutrosophic Set. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 38, 497 508

6. Atiqe Ur Rahman, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Convex and Concave Hypersoft Sets with Some Properties. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 38, 335 354

7. Adem Yolcu, Florentin Smarandache, And Taha Yasin Ozturk (2021). Intuitionistic Fuzzy Hypersoft Sets. Communications Faculty of Sciences University of Ankara - Series A1 Mathematics and Statistics 70(1), 443 455. DOI: 10.31801/cfsuasmas.788329

Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 27

Florentin

8. Atiqe Ur Rahman, Muhammad Saeed, Florentin Smarandache (2022). A theoretical and analytical approach to the conceptual framework of convexity cum concavity on fuzzy hypersoft sets with some generalized properties. Soft Computing, 18. DOI: 10.1007/s00500 022 06857-8

9. Muhammad Ihsan, Muhammad Saeed, Atiqe Ur Rahman, Florentin Smarandache (2022). Multi Attribute Decision Support Model Based on Bijective Hypersoft Expert Set. Punjab University Journal of Mathematics 54(1), 55 73. DOI: 10.52280/pujm.2021.540105

HYPERGRAPHS

1. Ali Hassan, Muhammad Aslam Malik, Florentin Smarandache (2016). Regular and Totally Regular Interval Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs. Critical Review XIII, 5 18

2. Muhammad Aslam Malik, Ali Hassan, Said Broumi, Assia Bakali, Mohamed Talea, F. Smarandache (2016). Isomorphism of Single Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs. Critical Review XIII, 19 40

3. Muhammad Aslam Malik, Ali Hassan, Said Broumi, Assia Bakali, Mohamed Talea, Florentin Smarandache (2016). Isomorphism of Interval Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs. Critical Review XIII, 41 66

4. Muhammad Aslam Malik, Ali Hassan, Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache (2016). Regular Bipolar Single Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 13, 84 89

5. Florentin Smarandache, Ali Hassan (2016). Regular Single Valued Neutrosophic Hypergraphs. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 13, 118 123

6. Florentin Smarandache, Nivetha Martin (2020). Plithogenic n Super Hypergraph in Novel Multi Attribute Decision Making. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 7(1), 8 30

7. Nivetha Martin, Florentin Smarandache (2020). Concentric Plithogenic Hypergraph based on Plithogenic Hypersoft sets - A Novel Outlook. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 33, 78 91

8. Nivetha Martin, F. Smarandache, Said Broumi (2021). PROMTHEE Plithogenic Pythagorean Hypergraphic Approach in Smart Materials Selection. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 13(1), 52 60

MISCELLANEA

1. Monika Moga, Gavrilă Calefariu, Florentin Smarandache, Flavius Aurelian Sârbu, Laura Bogdan (2014). Determining the Duration of R&D Processes through Monte Carlo Simulation. Applied Mechanics and Materials 657, 886 890. DOI: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.657.886

2. Florentin Smarandache, Ștefan Vlăduțescu (2014). Towards a Practical Communication Intervention. Revista de cercetare și intervenție socială 46, 243 254

3. Victor Vladareanu, Radu I. Munteanu, Ali Mumtaz, Florentin Smarandache, Luige Vladareanu (2015). The optimization of intelligent control interfaces using Versatile Intelligent Portable Robot Platform. Procedia Computer Science 65, 225 232

4. Luige Vlădăreanu, Florentin Smarandache, Mumtaz Ali, Victor Vlădăreanu, Mingcong Deng (2016). Robot System Identification using 3D Simulation Component Applied on VIPRO Platform. Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Advanced Mechatronic Systems, Melbourne, Australia, 6

5. Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache (2018). What we can do to save humanity in the coming era of global eavesdroppers (or the social innovation way to solve collective action problem), 5 p.

6. Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache (2018). The World Within Us (Or A Sketch of Consciousness Space Beyond Freudian Mental Model and Implications to Socio Economics Modeling and Integrative Cancer Therapy). BAOJ Cancer Research & Therapy 4(3): 057, 13

7. Luige Vladareanu, Victor Vladareanu, Hongnian Yu, Hongbo Wang, Florentin Smarandache (2018). Robot Advanced Intelligent Control developed through Versatile Intelligent Portable Platform. J Fundam Appl Sci. 10(4S), 155 160. doi: 10.4314/jfas.v10i4s.75

Collected Papers, X 28

Florentin

Smarandache (author and editor)

8. Victor Vladareanu, Sergiu Boris Cononovici, Marcel Migdalovici, Hongbo Wang, Yongfei Feng, Florentin Smarandache (2018). Application for Position and Load Reference Generation of a Simulated Mechatronic Chain. J Fundam Appl Sci. 10(4S), 161 167. DOI: 10.4314/jfas.v10i4s.76

9. Luige Vladareanu, Mihaiela Iliescu, Victor Vladareanu, Alexandru Gal, Octavian Melinte, Florentin Smarandache, Adrian Margean (2018). Improvement of the Material's Mechanical Characteristics using Intelligent Real Time Control Interfaces in HFC Hardening Process. J Fundam Appl Sci. 10(4S), 193 198. DOI: 10.4314/jfas.v10i4s.81

10. Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache (2019). On the Efficacy of Moringa Oleifera as Anticancer Treatment: A Literature Survey. BAOJ Cancer Research & Therapy 5(2): 069, 5

11. Darjan Karabašević, Florentin Smarandache (2019). Selection of Optimal Software Development Methodology Based on Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment Method, 51 66

12. Dragisa Stanujkic, Darjan Karabasevic, Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas, Florentin Smarandache, Fausto Cavallaro (2019). An Approach to Determining Customer Satisfaction in Traditional Serbian Restaurants. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 6(3), 1127 1138. DOI: 10.9770/jesi.2019.6.3(5)

13. Dragisa Stanujkic, Darjan Karabasevic, Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas, Florentin Smarandache, Willem K.M. Brauers (2019). A Bipolar Fuzzy Extension of the MULTIMOORA Method. Informatica 30(1), 135 152. DOI: 10.15388/Informatica.2019.201

14. Mihaela Colhon, Florentin Smarandache, Dan Valeriu Voinea (2019). Entropy of Polysemantic Words for the Same Part of Speech IEEE Access 8, 2975 2982. DOI: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2962420

15. Volodymyr Krasnoholovets, Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache, Rizha Vitania, The Houw Iong (2020). A Short Remark on Multipurpose Laser Therapy “Helios” in Ukraine and its Potential Application for Treatment of Neurology Disorders. EC Neurology SI2, 20 25.

16. Florentin Smarandache (2020). Improved, extended, and total impact factor of a journal. Bulletin of Pure and Applied Sciences 39E(2), 183 187

17. Abu Sufian, Anirudha Ghosh, Ali Safaa Sadiq, Florentin Smarandache (2020). A Survey on Deep Transfer Learning to Edge Computing for Mitigating the COVID 19 Pandemic. Journal of Systems Architecture 108, 101830, 11. DOI: 10.1016/j.sysarc.2020.101830

18. Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache (2020). A Review of the Evidences Showing that Certain Plant Medicines can be Useful for Novel Corona Virus Treatment. EC Microbiology 16(8), 64 69

19. Zaigham Tahir, Hina Khan, Muhammad Aslam, Javid Shabbir, Yasar Mahmood, Florentin Smarandache (2021). Neutrosophic ratio type estimators for estimating the population mean. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 11. DOI: 10.1007/s40747 021 00439-1

20. Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache (2021). Remark on Neutrosophy Perspective on Blue Ocean Shift. Bio Science Research Bulletin 37(1), 3. DOI: 10.5958/2320 3161.2021.00001.8

21. Victor Christianto, Florentin Smarandache, Rizha Vitania (2021). A Possible Application of DNA Transduction Experiment: Information Medicine for Pedestrians”. EC Microbiology 17(4), 18 25

Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 29

Florentin

Florentin Smarandache’s Collected Papers series:

Collected Papers, Vol. I (first edition 1996, second edition 2007) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/CP1.pdf

Collected Papers, Vol. II (Chişinău, Moldova, 1997) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/CP2.pdf

Collected Papers, Vol. III (Oradea, Romania, 2000) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/CP3.pdf

Collected Papers, Vol. IV (100 Collected Papers of Sciences) Multispace & Multistructure. Neutrosophic Transdisciplinarity (Hanko, Finland, 2010) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/MultispaceMultistructure.pdf

Collected Papers, Vol. V: Papers of Mathematics or Applied mathematics (Brussels, Belgium, 2014) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/CP5.pdf

Collected Papers, Vol. VI: on Neutrosophic Theory and Applications (Global Knowledge, 2022) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/CP6.pdf

Collected Papers, Vol. VII: on Neutrosophic Theory and Applications (Global Knowledge, 2022) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/CP7.pdf

Collected Papers, Vol. VIII: on Neutrosophic Theory and Applications (Global Knowledge, 2022) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/CP8.pdf

Collected Papers, Vol. IX: on Neutrosophic Theory and Its Applications in Algebra (Global Knowledge, 2022) Free download: http://fs.unm.edu/CP9.pdf

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 30

NEUTROSOPHICS

Collected Papers, X 31

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor)

Some Types of Neutrosophic Crisp Sets and Neutrosophic Crisp Relations

A.A. Salama, Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache

A.A. Salama, Said Broumi, Florentin Smarandache (2014). Some Types of Neutrosophic Crisp Sets and Neutrosophic Crisp Relations. I.J. Information Engineering and Electronic Business, 9

Abstract The purpose of this paper is to introduce a new types of crisp sets are called the neutrosophic crisp set with three types 1, 2, 3. After given the fundamental definitions and operations, we obtain several properties, and discussed the relationship between neutrosophic crisp sets and others. Finally, we introduce and study the notion of neutrosophic crisp relations.

Index Terms Neutrosophic set, neutrosophic crisp sets, neutrosophic crisp relations, generalized neutrosophic set, Intuitionistic neutrosophic Set.

I.Introduction

Since the world is full of indeterminacy, the neutrosophics found their place into contemporary research. The fundamental concepts of neutrosophic set, introduced by Smarandache in [16, 17, 18], and Salama et al. in [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15], provides a natural foundation for treating mathematically the neutrosophic phenomena which exist pervasively in our real world and for building new branches of neutrosophic mathematics. Neutrosophy has laid the foundation for a whole family of new mathematical theories generalizing both their classical and fuzzy counterparts [1, 2, 3, 19] such as a neutrosophic set theory. In this paper we introduce a new types of crisp sets are called the neutrosophic crisp set with three types 1, 2, 3. After given the fundamental definitions and operations, we obtain several properties, and discussed the relationship between

neutrosophic crisp sets and others. Finally, we introduce and study the notion of neutrosophic crisp relations.

The paper unfolds as follows. The next section briefly introduces some definitions related to neutrosophic set theory and some terminologies of neutrosophic crisp set. Section 3 presents new types of neutrosophic crisp sets and studied some of their basic properties. Section 4 presents the concept of neutrosophic crisp relations . Finally we concludes the paper.

II Preliminaries

We recollect some relevant basic preliminaries, and in particular, the work of Smarandache in [16 , 17, 18], and Salama et al. [4,5]. Smarandache introduced the neutrosophic components T, I, F which represent the membership, indeterminacy, and non-membership values respectively, where 1,0 is nonstandard unit interval.

Definition 2.1 [9, 13, 15]

A neutrosophic crisp set (NCS for short) 321,, AAAA can be identified to an ordered triple321,,AAA are subsets on X, and every crisp event in X is obviously an NCS having the form321,,AAA ,

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 32

Salama et al. constructed the tools for developed neutrosophic crisp set, and introduced the NCS NN X , in X as follows:

1) N may be defined as four types:

i)Type1: ,,, X N or

1) AB may be definedas twotypes: i) Type1: 332211,, BABABABA or ii) Type2: 332211,, BABABABA

ii)Type2: ,,,XX N or iii)Type3: ,,, X N or iv)Type4: ,, N

2) N X may be definedas fourtypes

i)Type1: ,,, XX N

2) AB may be definedas twotypes: i) Type 1: 332211,, BABABABA or ii)Type 2: 332211,, BABABABA

ii)Type2: ,,, XXX N iii) Type3: ,,, XXX N iv)Type4: ,,, XXXX N Definition 2.2 [9, 13, 15] Let 321,, AAAA a NCE or UNCE on X , then the complement of the set A ( cA , for short maybe defined as three kinds of complements

1C Type1: 321,, cccc AAAA , 2C Type2: 123,, AAAA c

Proposition 2.1 [9, 13, 15] Let JjA j : be arbitrary family of neutrosophic crisp subsets in X, then 1) jA may be definedtwotypes as : i)Type1: 132,,jj j AjAA A ,or ii)Type2: 132,,jj j AjAA A

2) jA may be definedtwotypes as : i)Type1: 132,,jj j AjAA A or ii)Type2: 132,,jj j AjAA A

III.New Types of Neutrosophic Crisp Sets

3C Type3: 1 2 3 ,, AAAA c c One can define several relations and operations between NCS as follows: Definition 2.3 [9, 13, 15] Let X be a non-empty set, and NCSS A and B in the form321,, AAAA ,321,, BBBB , then we may consider two possible definitions for subsets ( BA ) ( BA ) may be defined as two types:

1)Type1: 33 2211 and , BABABABA or 2)Type2: 33 2211 and , BABABABA

We shall now consider some possible definitions for some types of neutrosophic crisp sets Definition 3.1

Let X be a non-empty fixed sample space. A neutrosophic crisp set (NCS for short) A is an object having the form 321,, AAAA where 321,andAAA are subsets of X Definition 3.2

Definition 2.4 [9, 13, 15] Let X be a non-empty set, and NCSS A and B in the form321,, AAAA ,321,, BBBB are NCSS Then

The object having the form 321,, AAAA is called 1) (Neutrosophic Crisp Set with Type 1) If satisfying 21 AA , 31AA and 32AA . (NCS-Type1 for short). 2) (Neutrosophic Crisp Set with Type 2 ) If satisfying 21 AA , 31AA and 32AA and . 321XAAA (NCSType2 for short).

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 33

3) (Neutrosophic Crisp Set with Type 3 ) If satisfying 321 AAA and . 321XAAA (NCS-Type3 for short). Definition 3.3

,5.0)(xx A A ,5.0)(xx A A and 2)()()(0xxx A A A .

A neutrosophic crispwith three types the object 321,, AAAA can be identifiedto an ordered triple321,,AAA are subsets on X, and every crisp set in X is obviously a NCS having the form 321,,AAA .Every neutrosophic set )( ), ( ), ( xxxA AA A on X is obviously on NS having the form )( ), ( ), ( xxxAAA

1) (Neutrosophic Set [7]): Let X be a non-empty fixed set. A neutrosophic set ( NS for short) A is an object having the form )( ), ( ), (, xxxxAAAA where xxAA , and x A which represent the degree of member ship function (namely x A ), the degree of indeterminacy (namely x A ), and the degree of non-member ship (namely x A ) respectively of each element Xx to the set A where 1)( ), ( ), (0xxxAAA and 3)()()(0xxx A A A . 2) (Generalized Neutrosophic Set [8]): Let X be a non empty fixed set. A generalized neutrosophic (GNS for short) set A is an object havingthe form )( ), ( ), (, xxxxA AA A where xxAA , and x A which represent the degree of member ship function (namely x A ), the degree of indeterminacy (namely x A ), and the degree of non-member ship (namely x A ) respectively of each element Xx to the set A where 1)( ), ( ), (0xxxAAA and the functions satisfy the condition 5.0 xxx A A A and 3)()()(0xxx A A A 3)(Intuitionistic Neutrosophic Set [16]). Let X be a non-empty fixed set. An intuitionistic neutrosophic set A (INS for short) is an object having the form )( ), ( ), ( xxxA AA A where xxAA , and x A which represent the degree of member ship function (namely x A ), the degree of indeterminacy (namely x A ), andthe degree of non-member ship(namely x A ) respectively of each elementXx to the set A where )( ), ( ), (5.0xxxAAA and the functions satisfy the condition ,5.0 xx A A

Remark 3.1

1) The neutrosophic set not to be generalized neutrosophic set in general. 2) The generalized neutrosophic set in general not intuitionistic NS but the intuitionistic NS is generalized NS. Intuitionistic NS Generalized NS NS

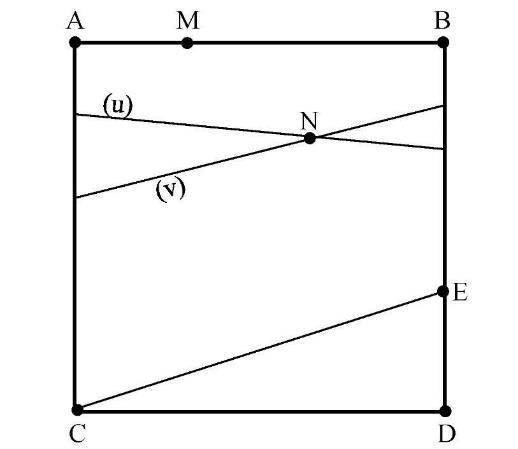

Fig.1: Represents the relation between types of NS Corollary 3.1 Let X non-empty fixed set and )( ), ( ), ( xxxA A A A be INS on X Then: 1)Type1- cA of INS be a GNS. 2)Type2- cA of INS be a INS. 3)Type3- cA of INS be a GNS. Proof Since A INS then )( ), ( ), (5.0xxxAA A , and 5.0)()(,5.0)()( xx xx A A A A 5.0)()(xx A A Implies 5.0)( ), ( ), ( xxx A c A c A c then is not to be Type1- cA INS. On other hand the Type 2- cA , )( ), ( ), ( xxxA A A A c be INS andType 3- cA , )( ), ( ), ( xxxA A A c A c and5.0)( x A c implies to )( ), ( ), ( xxxA A A c A c GNS and not to be INS

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 34

Example 3.1 Let cbaX ,, , andCBA,, are neutrosophic sets on X, ,\8.0,7.0,9.0(,\)6.0,7.0,6.0(,\)8.0,9.0,7.0 c b a A c b a B \8.0,5.0,9.0(,\)5.0,4.0,6.0(,\)5.0,9.0,7.0 c b a C \8.0,5.0,9.0(,\)5.0,8.0,6.0(,\)5.0,9.0,7.0

By the Definition 3.3 no.3 ,5.0)( xxx A A A A be not GNS and INS, c b a B \8.0,5.0,9.0(,\)5.0,4.0,6.0(,\)5.0,9.0,7.0 not INS, where 5.04.0)( b A . Since 5.0)()()(xxx B B B then B is a GNS but not INS. c b a Ac \2.0,3.0,1.0(,\)4.0,3.0,4.0(,\)2.0,1.0,3.0 be a GNS, but not INS. c b a Bc \2.0,5.0,1.0(,\)5.0,6.0,4.0(,\)5.0,1.0,3.0 be a GNS, but not INS, C be INS andGNS, c b a C c \2.0,5.0,1.0(,\)5.0,2.0,4.0(,\)5.0,1.0,3.0 be a GNS but not INS.

Definition 3.4

A neutrosophic crisp set (NCS for short) 321,, AAAA can be identified to an ordered triple321,,AAA are subsets on X, and every crisp set in X is obviously an NCS having the form321,,AAA , Salama et al in [6,13] constructed the tools for developed neutrosophic crisp set, and introduced the NCSNN X , in X as follows:

1) N may be defined as four types:

i) Type1: ,,, X N or ii)Type2: ,,,XX N or iii)Type3: ,,, X N or iv)Type4: ,, N

2) N X may be definedas fourtypes

i)Type1: ,,, XX N

ii)Type2: ,,, XXX N

v) Type3: ,,, XXX N

vi)Type4: ,,, XXXX N

Definition 3.5

A NCS-Type111 , NN X in X as follows:

1) 1N may be definedas three types: i) Type1: ,,,1 X N or ii) Type2: ,,,1 X N or iii) Type3: ,, N .

2) 1N X may be definedas one type Type1: ,, 1 XX N Definition 3.6 A NCS-Type2, 2 2 , NN X in X as follows:

1) 2 N may be definedas twotypes: i) Type1: ,,,2 X N or ii) Type2: ,, 2 X N

2) 2 N X may be definedas one type Type1: ,, 2 XX N Definition 3.7 a NCS-Type 3,33 , NN X in X as follows:

1) 3 N may be definedas three types: i) Type1: ,,,3 X N or ii)Type2: ,,,3 X N or iii) Type3: .,, 3 XX N

2) 3 N X may be defined as three types i)Type1: ,,, 3 XX N ii)Type2: ,,, 3 XXX N iii)Type3: ,,, 3 XXX N

Corollary 3.1

In general

1-Every NCS-Type 1, 2, 3 are NCS. 2-Every NCS-Type 1 not to be NCS-Type2, 3. 3-Every NCS-Type 2 not to be NCS-Type1, 3. 4-Every NCS-Type 3 not to be NCS-Type2, 1, 2. 5-Every crisp set be NCS.

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 35

The following Venn diagram represents the relation between NCSs

i)Type 1: },{ }, ,,{ }, ,{ ecfedfeD c be NCS-Type 3 but not NCS-Type 1, 2. ii)Type 2: },,,{ }, ,,{ }, ,,,{ dcbacbafdbaD c be NCS-Type 3 but not NCS-Type 1, 2. iii)Type 3: },,,{ }, ,,{ }, ,,,{ dcbafedfdbaD c be NCS-Type 3 but not NCS-Type 1, 2. Definition 3.8

Let X be a non-empty set, 321,, AAAA

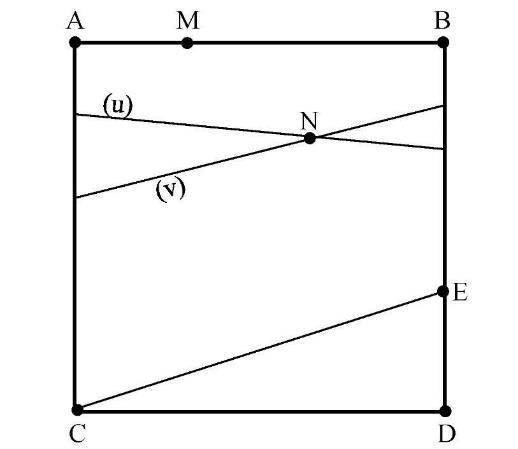

Fig. 2: Venn diagram represents the relation between NCSs

Example 3.2

Let DCBA,,, are NCSs on },,,,,{fedcbaX , the following types of neutrosophic crisp sets i) }{ }, },{ { cbaA be a NCS-Type 1, but not NCS-Type 2 and Type 3 ii) },{ }, ,{ }, ,{ efdcbaB be a NCS-Type 1, 2, 3 iii) },,{ }, },{ ,,,{fbaedcbaC be a NCS-Type 3 but not NCS-Type 1, 2. iv) },,,{ }, ,,{ }, ,,,{fdbacbadcbaD be a NCS but not NCS-Type 1, 2, 3. The complement for DCBA,,, may be equals The complement of A i)Type 1: },,,,{ }, ,,,,{ }, ,,,,{ fedbafedcafedcb Ac be a NCS but not NCS—Type1, 2,3 ii)Type 2: }{ }, },{ { abcA c be a NCS-Type 3 but not NCS—Type1, 2 iii)Type 3: }{ }, ,,,,{ }, { afedcacA c be a NCS-Type 1 but not NCS—Type 2, 3. The complement of B may be equals i)Type 1: },,,{ }, ,,,{ }, ,,,{ dcbafebafedcB c be NCS-Type 3 but not NCS-Type 1, 2. ii) Type 2: },{ }, ,{ }, ,{ badcfeB c be NCSType 1, 2, 3. iii)Type 3: },{ }, ,,,{ }, ,{ bafebafeB c be NCS-Type 3, but not NCS-Type 1, 2. The complement of C may be equals i)Type 1: },,{ }, ,,,,{ }, ,{ edcfdcbafeC c ii)Type 2: },,,{ }, },{ ,,{ dcbaefbaC c , iii)Type 3: },,,{ }, ,,,{ }, ,,{ dcbadcbafbaC c , The complement of D may be equals

1) If A be a NCS-Type1 on X , then the complement of the set A ( cA , for short maybe defined as one kind of complement Type1: 123,, AAAA c

2) If A be a NCS-Type 2 on X , then the complement of the set A ( cA , for short maybe defined as one kind of complement 123,, AAAA c 3)If A be NCS-Type3 on X , then the complement of the set A ( cA , for short maybe definedas one kind of complement defined as three kinds of complements 1C Type1: 321,, cccc AAAA , 2C Type2: 123,, AAAA c 3C Type3: 1 2 3 ,, AAAA c c

Example 3.3 Let },,,,,{fedcbaX , }{ }, },{ ,,,{fedcbaA be a NCS-Type 2, },{ }, },{ ,,{ edcbaB be a NCS-Type1., },{ }, ,{ }, ,{ fedcbaC NCS-Type 3, then the complement }{ }, },{ ,,,{fedcbaA , },,,{ }, },{ { dcbaefA c NCS-Type 2, the complement of },{ }, },{ ,,{ edcbaB , },,{ }, },{ ,{ cbaedB c NCS-Type1. The complement of },{ }, ,{ }, ,{ fedcbaC may be defined as three types: Type 1: },,,{ }, ,,,{ }, ,,,{ dcbafebafedcC c . Type 2: },{ }, ,{ }, ,{ badcfeC c , Type 3: },{ }, ,,,{ }, ,{ bafebafeC c , Proposition 3.1 Let JjA j : be arbitrary family of neutrosophic crisp subsets on X, then 1) jA may be definedtwotypes as :

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 36

Type1: 3 2 ,, 1 jj j AjAA A ,or Type2: 3 2 ,, 1 jj j AjAA A 2) jA may be definedtwotypes as : Type1: 3 2 ,, 1 jj j AjAA A or Type2: 3 2 ,, 1 jj j AjAA A .

Definition 3.9

Definition 4.1

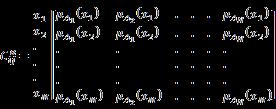

Let X and Y are two non-empty crisp sets and NCSS A and B in the form 321,, AAAA on X,

321,, BBBB on Y. Then

i) The product of two neutrosophic crisp sets A and B is a neutrosophic crisp setBA given by 332211,, BABABABA onYX

(a)If 321,, BBBB is a NCS in Y, then the preimage of B under , f denoted by ), (1 Bf is a NCS in X defined by ),.)( ( ), ()( 3 1 2 1 1 1 1 BfBfBfBf (b) If 321,, AAAA is a NCS in X, then the image of A under , f denoted by ), ( Af is the a NCS in Y defined by .))( ), ( ), ()( 3 2 1 c AfAfAfAf Here we introduce the properties of images and preimages some of which we shall frequently use in the following.

ii) We will call a neutrosophic crisp relation BAR on the direct productYX The collection of all neutrosophic crisp relations on YX is denoted as)(NCRYX

Definition 4.2

Let R be a neutrosophic crisp relation onYX , then the inverse of R is denoted by 1 R where BAR onYX then ABR 1 on . XY

Corollary 3.2 Let A, JiA i : , be a family of NCS in X, and B, KjB j : NCSin Y, and YXf : a function. Then (a) ), ()( 2 1 21AfAfAA ), ()( 2 1 1 1 21BfBfBB (b) )) (( 1 AffA and if f is injective, then ))(( 1 AffA , (c) BBff )) (( 1 and if f is surjective, then ,))(( 1 BBff (d) ), ())( 1 1 i i BfBf ), ())( 1 1 i i BfBf (e) ); ()( ii ii AfAf ); ()( ii ii AfAf andif f is injective,then ); ()( ii ii AfAf (f) ,)( 1 N N XYf N N f )( 1 (g) ,)( N N f ,)( N N YXf if f is subjective. Proof Obvious

Example 4.1

Let},,,{dcbaX , }{ }, },{ ,{ dcbaA and },{ }, },{ { bdcaB then the product of two neutrosophic crisp sets given by )} ),,( , {( {()},, )},,( ), , {( bdddccabaaBA and )} ),,( , {( {()},, )},,( ), , {( dbddccbaaaAB , and )} , {( {()},, {()},, 1 ddccaaR , BAR 1 on XX , )} ),,( , {( {()},, {()},, 2 dbddccbaR ABR 2 onXX .

Example 4.2 From the Example 3.1 1 1R = )} , {( {()},, {()},,ddccaa AB and )} ),,( , {( {()},, {()},, 1 2 bdddccabR AB .

Example 4.3

IV.Neutrosophic Crisp Relations

Let },,,,,{fedcbaX , }{ }, },{ ,,,{fedcbaA , },{ }, ,{ }, ,{ dfcebaD be a NCS-Type 2,

Here we give the definition relation on neutrosophic crisp sets and study of its properties. Let X, Y and Z be three ordinary nonempty sets

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 37

},{ }, },{ ,,{ edcbaB be a NCS-Type1. },{ }, },,{ ,{ fedcbaC be a NCS-Type 3. Then )} ,( ), , {( )},,( ), , {( )},,( ), ,(, ),( ), ),,( ),,( ),,( ),,( ),,( , {( dfffceeebdad bcacbbbbabbaaa DA )} ),,( ),,( ,( ), , {( )},,( ), ,( ), ),,( , {( )},,( ), ),,( ),,( , {( fdedffefdccc decebbabbaaa CD we can construct many types of relations on products. We can define the operations of neutrosophic crisp relation.

v) QRSRQSR . .

vi) QRSRQSR . vii)If , RS , RQ then RQS

Proof Clear Definition 4.5

The neutrosophic crisp relation )(NCRXX I , the neutrosophic crisp relation of identity may be defined as two types i)Type1: }, },{ { AAAAI ii)Type2: , }, { AAI

Definition 4.4 Let R and S be two neutrosophic crisp relations between X and Y for every YXyx ),( and NCSS A and B in theform 321,, AAAA on X, 321,, BBBB on Y, Then we can defined the following operations

i) SR may be definedas twotypes a)Type1:SR , 11SR BA , 22SR BA SRBA33 b)Type2:SR , 11SR BA , 22SRBA RSAB33 ii) SR may be definedas twotypes a)Type1: SR SRSRSR BABABA 332211,, , b)Type2: SR

SRSRSR BABABA 332211,, . iii) SR may be definedas twotypes a)Type1:SR

SRSRSR BABABA 332211,, , b)Type2: SR

SRSRSR BABABA 332211,, .

Theorem 4.1 Let R , S and Q be three neutrosophic crisp relations between X and Y for every YXyx ),( , then i) 11 SRSR ii) . 11 1 SRSR iii) . 11 1 SRSR iv) 1 1 RR

Now we define two composite relations of neutrosophic crisp sets. Definition 4.6

Let R be a neutrosophic crisp relation in YX , and S be a neutrosophic crisp relation in ZY . Then the composition of R and S ,SR be a neutrosophic crisp relation in ZX as a definition may be defined as two types i)Type1: SR )(), ( zxSR })() {( { 22 11 S R BABA , }, )() {( 22 22 S R BABA })() {( 33 33 S R BABA . ii)Type2 : SR )(), ( zxSR })() {( { 22 11 S R BABA , }, )() {( 22 22 S R BABA })() {( 33 33 S R BABA . Example 4.5 Let },,,{dcbaX , }{ }, },{ ,{ dcbaA and },{ }, },{ { bdcaB then the product of two events given by )} ),,( , {( {()},, )},,( ), , {( bdddccabaaBA , and )} ),,( , {( {()},, )},,( ), , {( dbddccbaaaAB , and )} , {( {()},, {()},, 1 ddccaaR , BAR 1 on XX , )} ),,( , {( {()},, {()},, 2 dbddccbaR ABR 2 onXX .

Florentin Smarandache (author and editor) Collected Papers, X 38

)} , {( {()},, {()},, )} , {( 21ddccbaaaRR )} , {( )},, { ddcc and }{)},,).(,).(, {( )},.).(,).(, {( 1 abbaaaabbaaaI A , }{ }, {)},.).(,).(, {( 2 abbaaaI A

Theorem 4.2

Let R be a neutrosophic crisp relation in YX , and S be a neutrosophic crisprelation in ZY then111)( RSSR

Proof Let BAR onYX then ABR 1 , DBS on ZY then BDS 1 , from Definition 3.6 andsimilarly we can ),( and ),(),( 1 1 1 )( zxIzxIzxI R S SR then 111)( RSSR .

References

[1]K. Atanassov, intuitionistic fuzzy sets, in V.Sgurev, ed.,Vii ITKRS Session, Sofia(June 1983 central Sci. and Techn. Library, Bulg. Academy of Sciences ( 1984).

[2]K. Atanassov, intuitionistic fuzzy sets, Fuzzy Sets and Systems 2087-96, (1986)

[3]K. Atanassov, Review and new result on intuitionistic fuzzy sets, preprint IM-MFAIS-1-88, Sofia, (1988).

[4]S. A. Alblowi, A.A. Salama and Mohmed Eisa, New Concepts of Neutrosophic Sets, International Journal of Mathematics and Computer Applications Research (IJMCAR),Vol. 4, Issue 1, (2014) 59-66.

[5]I. M. Hanafy, A.A. Salama and K. Mahfouz, Correlation of Neutrosophic Data, International Refereed Journal of Engineering and Science (IRJES) , Vol.(1), Issue 2 .(2012), pp.39-33

[6]I.M. Hanafy, A.A. Salama and K.M. Mahfouz,," Neutrosophic Classical Events and Its Probability" International Journal of Mathematics and Computer Applications Research(IJMCAR) Vol.(3),Issue 1,Mar (2013) ,pp.171-178.

[7]A. A. Salama and S.A. Alblowi, "Generalized Neutrosophic Set and Generalized Neutrosophic Spaces,"Journal Computer Sci. Engineering, Vol. (2) No. (7) (2012),pp 129-132 .

V.Conclusion

In our work, we have put forward some new types of neutrosophic crisp sets and neutrosophic crisp continuity relations. Some related properties have been established with example. It ‘s hoped that our work will enhance this study in neutrosophic set theory.

[8]A. A. Salama and S. A. Alblowi, Neutrosophic Set and Neutrosophic Topological Spaces, ISOR J. Mathematics, Vol.(3), Issue(3), (2012), pp 31-35.

[9] A.A. Salama, Neutrosophic Crisp Point & Neutrosophic Crisp Ideals, Neutrosophic Sets and Systems, Vol.1, No. 1, (2013) pp. 50-54.

[10]A. A. Salama and F. Smarandache, Filters via Neutrosophic Crisp Sets, Neutrosophic Sets and Systems, Vol.1, No. 1, (2013), pp. 34-38.

[11] A.A. Salama and S.A. Alblowi, Intuitionistic Fuzzy Ideals Spaces, Advances in Fuzzy Mathematics , Vol.(7), Number 1, (2012) pp. 51 60.

[12] A.A. Salama, and H.Elagamy, Neutrosophic Filters, International Journal of Computer Science Engineering and Information Technology Reseearch (IJCSEITR), Vol.3, Issue(1),Mar 2013,(2013) pp 307 312.

[13] A.A. Salama, F. Smarandache and V Kroumov, Neutrosophic crisp Sets & Neutrosophic crisp Topological Spaces, Neutrosophic Sets and Systems, Vol.(2), pp25 30, (2014).

[14] A.A. Salama, Mohamed Eisa and M. M. Abdelmoghny, Neutrosophic Relations Database, International Journal of Information Science and Intelligent System, 3(1) (2014).

[15] A. A. Salama , Florentin Smarandache and S. A. ALblowi, New Neutrosophic Crisp Topological Concepts, Neutrosophic Sets and Systems, (Accepted), (2014) .

[16] M Bhowmik and M Pal, Intuitionistic Neutrosophic Set Relations and Some of its Properties, Journal of Information and Computing Science, Vol.(5),No.3,(2010),pp 183 192.

[17] F Smarandache, Neutrosophy and Neutrosophic Logic, First International Conference on Neutrosophy , Neutrosophic Logic, Set, Probability, and Statistics University of New Mexico, Gallup, NM 87301, USA(2002).