9 minute read

Diversity in Late Stone Age Art in Zimbabwe. An Elemental and Mineralogical Study of Pigments (Ochre) from Pomongwe Cave, Matobo Hills, Western Zimbabwe Jonathan Nhunzvi, Ancila Nhamo, Laure Dayet, Stéphanie Touron & Millena Frouin

the rock art of the hunter-gatherers in southern africa

Diversity in Late Stone Age Art in Zimbabwe

Advertisement

An Elemental and Mineralogical Study of Pigments (Ochre) from Pomongwe Cave, Matobo Hills, Western Zimbabwe

Jonathan Nhunzvi, Ancila Nhamo, Laure Dayet Stéphanie Touron & Millena Frouin

Jonathan Nhunzvi is a holder of a master’s degree in Archaeology from the University of Zimbabwe. He is interested in rock art, Stone Age and archaeological management. Ancila Nhamo is currently a Research Specialist in Humanities and Social Sciences in the Research and Innovation Directorate at the University of Zimbabwe. She is also a senior lecturer of Archaeology and Heritage Studies in the Department of History. Her interests are in rock art and archaeological management, conservation and sustainable usage. Laure Dayet, associate researcher, UMR 5608 TRACES Stéphanie Touron, holder of a PhD in Geology, is the head of the Rock Art Conservation Department at the Laboratory of Research for Historical Monuments in France. Her research is focussed on environmental conditions for conservation, identication of constitutive materials of art and its medium, and sanitary assessments of rock art. Millena Frouin, holder of a PhD in Earth Sciences and working as a geoarchaeologist for more than 10 years, is now involved in Rock art and Megalith conservation at the Research Laboratory for Historical Monuments.

Ochre is a common archaeological artefact that is widespread discovered in Iron Age, Late Stone Age (LSA) and Middle Stone Age (MSA) contexts throughout Africa (Watts, 2002). According to Watts (2002), a considerable ochre record exists for both the MSA (250 000-40 000 BP) and LSA (40 000-2 000 BP) of southern Africa. The exploitation of ochre had become common place and continues into the MSA, the LSA, histor ical and ethnographic periods. Despite this, little work has been done on these assemblages and ochre variability and sourcing patterns are not well understood for any of the periods. This study analysed ochre samples from Pomongwe Trench V excavated by Walker in 1979. These are housed at the Zimbabwe Museum of Human Science in Harare. Geological samples from surrounding sources were also studied in order to analyse the sourcing patterns by ancient communities residing at Pomongwe in different periods of the site’s occupational history as evidenced from other researches (Dayet et al, 2015; Porraz et al, 2013). At Pomongwe Cave, ochre occurs in all the 14 levels of Walker’s Trench V. Cooke (1963) also reported the presence of ochre in his excavations of Trench 1-3. There is evidence that ochre was used for various purposes such as making pigment for rock art, colouring objects such as beads, bone tools and body painting (Walker, 1995). But little is known of the elemental, mineralogical composition of the ochre as well as where it was sourced. There was also little infor mation on var iation of utilization of this resource over time and patterns of preference for different types of ochre, especially for the different purposes. For example, was ochre used for rock art the same way that for colouring beads and body painting? Thus, the meaning of this variability in types of ochre to the socio-economic and technological practices of the LSA at Pomongwe Cave is not known (Dayet et al, 2013; Hughes and Solomon 2000).

Methods

Archaeological samples

Trench V of Walker (1995) had 14 levels which yielded 490 ochre pieces available for the study. Out of these samples, 26 were selected for the study. Their selection was based on colour, texture and modification with an equal representation from all levels.

Geological Samples

Three source areas were chosen to investigate both the degree of homogeneity within a source (intra-source variation) and between sources (inter-source variation): Hope Fountain, which is approximately 20 kilometres north of Pomongwe Cave; Criterion (25 kilometres north-east); and Esigodini (40 kilometres north-west). The results were used for comparative analyses with archaeological samples. A total number of five samples per single source were collected.

Analyses

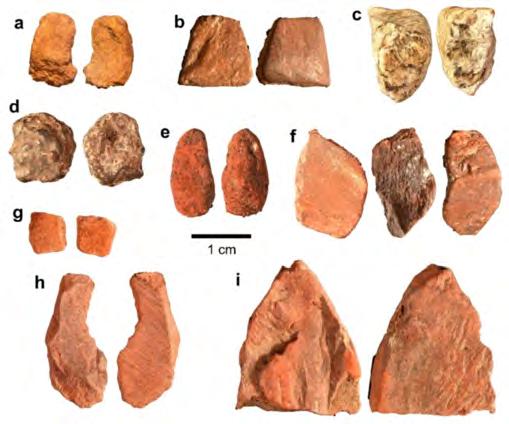

For both archaeological and geological samples, m a c ro s c o p i c a n d m i c ro s c o p i c o b s e r vat i o n s we re recorded. These include colour (red, dark red, yellow, and black), texture (clay, silt and sand; Fig. 1), technotypological features, and use wear traces (striations). The elemental and mineralogical analyses were carried out using XRD, pXRF, XRF and SEM-EDS techniques. Out of the 26 samples, 3 of them showed traces of utilisation, so were not subjected to analyses. A total of 23 archaeological samples were subjected to XRD and pXRF and among these, 4 were examined using SEM-EDS technique. The 15 collected geological samples were subjected to XRF analysis.

Results

Macro and microscopic analyses

Colour frequencies of samples were almost similar with predominance of red and dark red from level 1-14, while level 1-5 also recorded yellow and black pieces. In terms of texture, the sequence is dominated with

Figure 1: Plate with different colours of ochre pieces from Pomongwe Cave sequence (by Nhunzvi J).

silt/clay. There is also evidence of crystallized pieces from level 1-4 and level 14 records sand/clay pieces. Level 2, 7 and 8 recorded pieces with evidence of utilization (Fig. 2).

Elemental and mineralogical analyses

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) samples were mainly composed of hematite, quartz and clay minerals such as muscovite/ illite, kaolite and biotite, some of the samples shows the peaks and variation.

Por table X-ray Fluorescence (pXRF) recorded different elements, but only elements with 10% and above readings were recorded and only iron oxide (Fe), manganese (Mn) and calcium (Ca) fall within this range.

Scanning Electron Microscopy–Energy Dispensed Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) results of 4 samples subjected to the technique were complementary or consistent with X R D a n d p X R F re s u l t s. S a m p l e s re c o r d e d h i g h concentration of (Mn) with (23.8%) and a very low concentration of (Fe), while some recorded a significant concentration of (Fe). (Mn) recorded a low concentration which was consistent with XRD results which had high hematite.

the rock art of the hunter-gatherers in southern africa

Figure 2: Piece showing profile of being utilised (by Frouin M).

Geological Samples

Samples from Hope Fountain contained high contents of (Fe) with some samples recording (38%) and (Ca) (3.9%). Criterion and Esigodini samples contained high (Ca) content and low (Fe) and (Mn).

Discussion and Conclusion

From the macroscopic and microscopic analyses, temporal variations in the types of ochre exploited were observed in the sequence of occupation of Trench V. For example, the sequence from stratigraphy show that in terms of colour, Pomongwe period (11 000-9 500 BP) preferred red pigment as compared to Nswatugi (9 4004 8 0 0 B P ) , M a l e m e ( 1 3 0 0 0 - 1 1 0 0 0 B P ) a n d Amadzimba (4 100-2 200 BP) (Bandama, 2013; Walker & Thor p, 1997). In ter ms of texture, crystallized pieces are evident in the Amadzimba cultural group.

From the elemental and mineralogical analyses, one of the variations observed was from level 14, dated to 13 000 BP, which denotes the transition from MSA to LSA. Both pXRF and XRD data has shown low content of (Fe) with a high concentration of clay minerals such as illite. This varies with levels 13, 12 and 8 which records high (Fe) content, which can explain the preferred ochre pieces rich in iron oxide. The data from level 7 to 5 (Nswatugi cultural group) records significant high concentration of iron oxide, hematite and calcium. From the pXRF analyses sample 114 records only low concentration of calcium with 8.8%, while sample 127 recorded high concentrations in (Fe 34.8%) and (Ca 17.6%). It can be observed from group preferred materials rich in calcium and iron oxide, which varies with other groups that preferred either iron or calcium. Such variation can be understood from Walker (2012) who argued that, after 13 000 BP, several innovative industrial stages and stylistic phases can be recognized within LSA period. Nswatugi cultural group could have been this industrial innovative, since the period from Walker (1995) is associated with stylistic rock art as evidenced from the site Nswatugi.

These initial results indicate that major iron or hematite sources in the region can be identified based on their colour, texture and elemental content. Its sequence var iation and discr iminated using complementary techniques such as pXRF, XRF, XRD and SEMEDX. The study has also tried to look into sourcing of Iron oxide (Fe) in the Matobo landscape and match them with archaeological samples, though it was only limited to one technique that requires other complementally techniques such as XRD and SEM-EDS. The ability to study source areas and match samples to source is, therefore, a significant contribution towards to our understanding of exploitation, acquisition and exchange networks of iron oxide or hematite technologies in the past.

Bibliography

BANDAMA, F., 2013, “A reappraisal of Stone Age hunter gatherer research in Zimbabwe with a special focus on the later period in eastern Zimbabwe”, in MANYANGA, M. and S. KATSAMUDANGA (eds.), Zimbabwean Archaeology in the Post-Independence Era, Harare, Sapes Books, p. 17-31. COOKE, C. K., 1963, “Report on Excavations at Pomongwe and Tshangula Caves, Matopo Hills, Southern Rhodesia”, The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 18(7), p. 73-151.

DAYET, L., TEXIER, P.-J., DANIEL, F., PORRAZ, G., 2013, “Ochre resources from the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(9), p. 3492-3505. DAYET, L., LE BOURDONNEC, F.-X., DANIEL, F., PORRAZ, G., TEXIER, P.-J., 2015, “Ochre provenance and procurement strategies during the middle stone age at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa”, Archaeometry, 57(5), p. 3-15. HUGHES, J., SOLOMON, A., 2000, “A preliminary study of ochres and pigmentaceous materials from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Towards an understanding of San pigment and paint use”, Natal Museum Journal of Humanities, 12, p. 15-31. PORRAZ, G., TEXIER, P.-J., ARCHER, W., PIBOULE, M., RIGAUD, J.-P., TRIBOLO, C., 2013, “Technological successions in the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof rock shelter, Western Cape, South Africa”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(9), p. 3376-3395. WALKER, N. J., 2012, The Rock Art of the Matobo Hills, Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Prehistory, p. 17-34. WALKER, N., 1995, Late Pleistocene and Holocene Hunter-gatherers of the Matopos, Uppsala, Societas Archaeologica Uppsaliensis. WALKER, N. J., THORP, C., 1997, “Stone Age Archaeology in Zimbabwe”, in PWITI, G. (ed.), Caves, Monuments and Texts. Zimbabwean Archaeology Today, Uppsala, Studies in African Archaeology, p. 9-32. Watts I., 2002, “Ochre in the Middle Stone Age of Southern Africa: Ritualised Display or Hide Preservative?”, South Africa Archaeological Bulletin, 57(175), p. 1-14.