10 minute read

Phytanthropes. Human-Plant Conflations in the Rock Art of Zimbabwe Stephen van den Heever

Phytanthropes

Advertisement

Stephen van den Heever

Stephen van den Heever completed an Honours degree in Archaeobotany from the University of the Witwatersrand in 2015. He then held the position of tracing technician at the Rock Art Research Institute.

Introduction

In San cosmology, little distinction is made between the natural and human world because the lives and roles of humans, animals, plants, natural phenomenon, and landscape are inseparably intertwined and intermeshed one with another. Previously, researchers have looked at animals, weather, and health but little attention has been given to plants beyond their prosaic uses. Yet plants are an intrinsic par t of hunter-gatherer lives. They play a significant role in every aspect of their existence, from subsistence and medicine to magic, religion, ritual, and mythology. In order to get a more complete understanding of San cultures, this lacuna must be redressed because there is evidence of the importance of plant-people relationships deeply intrenched in San beliefs and ontologies of San groups, I use phytanthropic (part plant, part human) motifs found in rock art, in conjunction with ethnobotanical records from elsewhere in southern Africa, focusing on the relationships between Zimbabwean hunter-gatherers and plants.

Botanical motifs

Botanical motifs have been recorded in the huntergatherer rock art across much of southern Africa, yet the vast majority occur in Zimbabwe. These motifs are found in seven of the ten Zimbabwean provinces, with 53% found in Mashonaland East. Botanical motifs are highly

cosmology. To open a discussion on a wider array of schematized, although some types, like trees, are still easily recognisable as, what Taylor (1927 in Mguni 2009) calls ‘conventional trees’. It is because many rock ar t researc her s have posited that these plants are unidentifiable (Garlake, 1995; Walker, 1996; Hubbard, 2013). However, this is only the case if researchers try to identify the plants based on wester n taxonomic classifications and not the culturally specific classificatory system that the painter likely would have used. Using the above analytical method, in conjunction with relevant ethnographic material, has allowed me to allocate the content of botanical motifs into seven categories: trees, tubers, leaves, fruit, flowers, mushrooms and phytanthropes.

Phytanthropes

One of the most interesting and, to date, unstudied subsets of botanical motifs are phytanthropes (from the Greek phytos – pertaining to plants, and anthropos – h u m a n ) . P hy t a n t h ro p e s a re b e i n g s f o u n d i n t h e Zimbabwean rock art that combine the features of humans and plants, similar to the way that therianthropes combine features of humans and animals. Phytanthropes are rare and have not been described in reports of the rock art of the rest of southern Africa.

Despite being rare in the rock art, phytanthropes do appear in the ethnographic material collected from the Northern Cape and Kalahari (Bleek and Lloyd, 1911; Bleek, 1935; Marshall, 1962, 1999; Biesele, 1976; Guenther, 1989). A widely held belief amongst San groups is that creation occurred in two orders (Guenther, 1989; Hewitt, 2008). During the first order, after all the people and animals were created, they all lived in a primordial state in which animals, people, and plants appeared to be one, but could easily shift according to need (Guenther, 1989; Keeney, 2003; Mguni, 2009). It was only after an event – the exact nature of which varies between groups – that all things were settled into their current forms (Bleek and Lloyd, 1911; Biesele, 1975; Guenther, 1989, 1999; Eastwood & Eastwood, 2006). Following this, many San believe that animals, plants, and humans are, in many ways, equal in that they all have some deg ree of personhood (Guenther, 1989). These beliefs extend to include natural forces like rain as persons with agency – which can exert their own will (Low, 2014).

People had to forge and maintain relationships with certain plants in order to use them safely. For example, the root of ʃo-/õä (a medicinal and magical plant or class of plants used by the ǀXam) could only be safely collected by a ʃo-ǀ õä -ka-ǃkwi, a ritual specialist who used this class of plant medicine (de Prada-Samper, 2007). A ʃo-ǀ õä -ka-ǃkwi had to be introduced to the plant and had to learn to speak its language. Such a connection was formed that the ʃo-ǀ õä -ka-ǃkwi took on the scent of this plant and in doing so took on some of its powers (McGranaghan, 2012).

San deities often took the form of trees and plants; for example, Hi∫e (Nharo), ǀXue, (Juǀ’hoãn) and, to a lesser extent, ǀKaggen (ǀXam) are fundamentally associated with the botanical world (Mguni, 2009). This can be seen in the folklore and mythologies; for example the ǀXam believe that certain groups of plants (e.g. water plants like reeds and rushes) have guardians and these belong to members of the Early Race (Bleek and Lloyd, 1911 in Hoff, 2011). These guardians often look like or have features of those which they guard (Hoff, 2011), so phytanthropes may be the guardians of these plants.

The belief in the liminality between plants and people is not restricted to mythology and the Early-Race stories

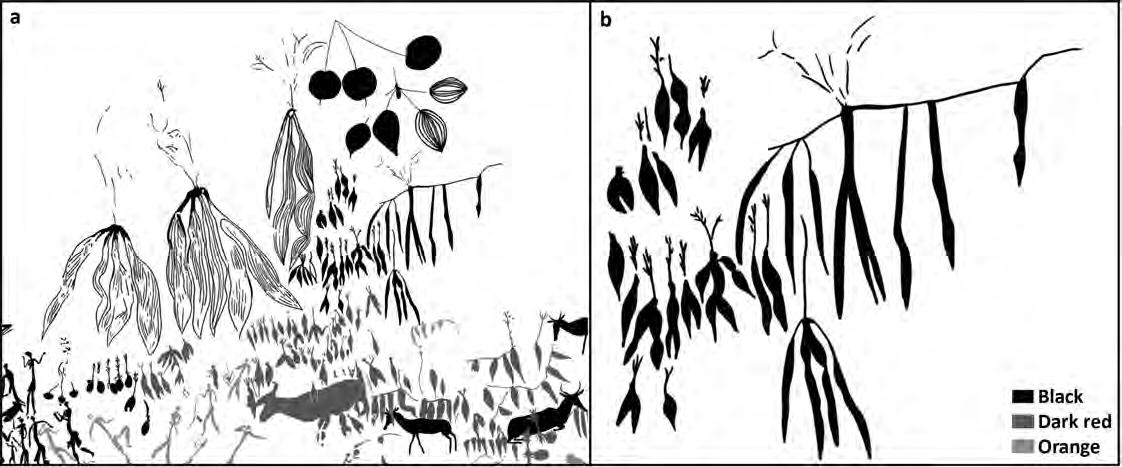

Figure 1: a) Upper section of a panel at Thetford with numerous roots, tubers, and phytanthropes (Mashonaland Central); b) three phytanthrope figures isolated from the panel (redrawn from picture: S. Van den Heever).

(Mguni, 2009), but features in inter views with San individuals. For instance, a Juǀ’hoãn woman said that she was ’not a person or an animal at all, but an edible root called ≠dwaǀk∂ma’ (Biesele, 1976).

Phytanthropes have elements of different plants types and can be largely separated into tuberous phytanthropes, arboreal phytanthropes, and those with more subtle plantlike characteristics with the former being the most numerous. The panel at Thetford, Mashonaland Central (Figure 1) contains the largest and most diverse collection

Figure 2: Tree phytanthrope at Macheke, Mashonaland East, Zimbabwe (redrawn from Goodall, 1959: S. van den Heever). of roots and tubers recorded in Zimbabwe so far. These tubers and roots are in varying shapes, sizes, and configurations but the vast majority are elongated fusiform shapes that are sprouting or are connected to others of the same type by horizontal lines. The three figures at the centre of this panel (Figure 1b) have humanoid shapes with tuber-like appendages, arms formed out of the horizontal connecting roots, and sprouting leaves/vines from their heads. The plants surrounding these figures have the same style of leaves emerging from their tops even though the tubers differ greatly in appearance suggesting at this sprouting an important feature of tuberous plants in the beliefs of the Zimbabwean hunter-gatherers. The connection with roots is likely a metaphor for travelling underground (which is part of the spirit world in the San three-tiered cosmos), and associated somatic sensations experienced during trance, the elongation of the limbs and trunk (Lewis-Williams & Dowson, 1989), tingling of hair roots (pilo-erection) giving one the sense of bristling or being hair y (Hollmann, 2002), and difficulty breathing (Huffman, 1983). The sprouting vegetation from the heads of these figures could be representations of supernatural potency as it boils in the stomach and then travels through the spine and out through the head (Katz, 1982), and the lines or ropes a person uses to leave their body during out of body experiences when in a deep trance (Huffman, 1983). Roots and tubers are the most common type of plant part used to aid in entering trance for novices, by replicating the somatic sensations mentioned above, as well as the feeling of supernatural potency boiling in the stomach (Shostak, 1983; Lee, 1993). To the left of the panel is a procession of women dancing around two other human figures. The first is painted in a natural depression in the rock face and is curled up with their legs drawn towards their body. The second kneels besides the first with their elongated arms extended towards the first. This scene is reminiscent of a healing dance with the curled-up figure being cured with the knelling figure. In light of this, I interpret these figures as phytanthropes who are likely to be ritual specialists in trance who have taken on aspects of tuberous plants.

Arboreal phytanthropes are conflations of humans and trees demonstrating a near seamless integration of

the rock art of the hunter-gatherers in southern africa

features from both. There are those with and without leaves, but all have the trunk forming the torso, the roots forming the legs, branches forming the arms, with rounded human heads. The human heads often have branches growing from them. Trees and humans share many superficial morphological features and humans can often look like trees. It is the human head, and the number of branches and roots (i.e. two of each) that demarcate these as phytanthropes and not just trees. These features are evident in the phytanthrope figure from Macheke (Figure 2) where the branches forming the arms, and branches from the head join to a solid canopy.

Conclusion

In light of these considerations, I propose that phytanthropes are either mythic figures like those m e n t i o n e d a b ove, o r, m o r e l i k e ly, a r e h u m a n s transforming with plant power. Mythic figures could be deities, members of the Early Race, or guardians like those of the ǀXam. The prevalence of botanical motifs across Zimbabwe along with the presence of phytanthropes are physical representations of the importance of people-toplant (and perhaps plant-to-people) relationships to the hunter-gatherers of Zimbabwe.

Bibliography

BIESELE, M., 1975, Folklore and ritual of Kung hunter gatherers, Doctoral dissertation, Harvard, Harvard University. BIESELE, M., 1976, “Aspects of !Kung folklore”, in R.B. LEE, I. DE VORE (eds.), Kalahari Hunter-gatherers: Studies of the !Kung San and their Neighbours, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, p. 303-324. BLEEK, D.F., 1935, Kun Mythology, Zeitschrift für Eingeborenensprachen, 25, p. 261-283. BLEEK, W.H.I., LLOYD, L., 1911, Specimens of Bushman Folklore, London, Allen. EASTWOOD, E.B., EASTWOOD, C., 2006, Capturing the Spoor: an Exploration of Southern African Rock Art, New Africa Books. GARLAKE, P., 1995, The Hunter’s Vision, British Museum Press. GOODALL, E., 1959, Prehistoric Rock Art of the Federation of Rhodesia & Nyasaland, National publications trust. GUENTHER, M., 1989, Bushman Folktales. Oral Traditions of the Nharo of Botswana and the/Xam of the Cape, Studien zur Kulturkunde, 93. GUENTHER, M.G., 1999, Tricksters and Trancers: Bushman Religion and Society, Indiana University Press. HEWITT, R., 2008, Structure, Meaning and Ritual in the Narratives of the Southern San, NYU Press. HOFF, A., 2011, “Guardians of Nature Among the ǀXam San: an exploratory study”, The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 66(193), p. 41-50. HOLLMANN, J., 2002, “Natural Models, Ethology and San Rock-Paintings: pilo-erection and depictions of bristles in southeastern South Africa”, South African Journal of Science, 98(11-12), p. 563-567. HUBBARD, P., 2013, “Plants in Rock Art: some thoughts from Zimbabwe”, The Digging Stick, 30(1), p.16-17. HUFFMAN, T.N., 1983, “The Trance Hypothesis and The Rock Art of Zimbabwe”, Goodwin Series, 4, p. 49-53. KATZ, R., 1982, Boiling energy: community healing among the Kalahari Kung, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. KEENEY, B.P., (eds), 2003, Ropes to God: Experiencing the Bushman Spiritual Universe, 8, Leete’s Island Books. LEE, R.B., 1993, The Dobe Juǀ’hoansi, nd 2 edition, Fort Worth, Harcourt Brace College Publishers. LEWIS-WILLIAMS, J.D., DOWSON, T.A., 1989, Images of Power: Understanding Bushman Rock Art, Johannesburg, Southern Books. LOW, C., 2014, “Khoe-San ethnography, ‘new animism’ and the interpretation of southern African rock art”, The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 69(200), p. 164-172. MARSHALL, L. J., 1962, “!Kung Bushmen Religious Beliefs”, Africa, 32, p. 231-249. MARSHALL, L., 1999, Nyae Nyae !Kung Beliefs and Rites, Peabody Museum Press.

MCGRANAGHAN, M., 2012, Foragers on the frontiers: the ǀXam Bushmen of the Northern Cape, South Africa, in the nineteenth century, Doctoral dissertation, Oxford, Oxford University. MGUNI, S., 2009, “Natural and Supernatural Convergences Trees in Southern African Rock Art”, Current Anthropology, 50(1), p. 139-148. PRADA-SAMPER, J.D., 2007, “The plant lore of the ǀXam San. Kabbo and ≠Kasiŋ’s identification of ‘Bushman medicines’”, Culturas Populares, 4, p. 1-17. SHOSTAK, M., 1983, Nisa: The Life and Words of a !Kung Woman, New York, Vintage Books. WALKER, N., 1996, The Painted Hills: Rock Art of the Matopos, Zimbabwe: a Guidebook, Mambo Press.