12 minute read

Introduction: The Rock Art of the Hunter-Gatherers of Southern Africa Léa Jobard, Carole Dudognon & Camille Bourdier

introduction

Advertisement

Léa Jobard, Carole Dudognon Camille Bourdier &

After a century and a half of research, Southern Afr ican roc k ar t is today built up on remarkable archaeological materials that make it possible to conceive, in the long term, the history of the hunter-gatherers who, for a long time, have been deprived of it. While the artistic testimonies of contemporary groups have drawn researchers’ attention at the very time when these p o p u l at i o n s we re d i s a p p e a r i n g ( E g o, 2 0 0 0 ) , t h e ethnographic and linguistic stories of the latest artists have tried to give meaning again to these works (Bleek, 1874, 1932; Orpen, 1874). Considered for a long time as the expression of the recent history of San populations, these artistic productions offer a visual quality that was lauded th as early as the 19 century. They have been reproduced on the occasion of many redrawing campaigns, some of which have initiated parallels with European prehistory (Breuil, 1948). Covering a surface area of a few million square kilometres from Namibia to Mozambique, and from the north of Zimbabwe to the Cape of Good Hope, the abundant documentation work has revealed, among hunter-gatherer populations, a powerful traditional heritage of wall iconography. Within this common whole, a complex set of spatial variations leads to recognising four major “artistic” provinces: ZimbabweLimpopo, Namibia, South-Eastern Cape and the central plateau of South Africa, i.e. the Western Cape (LewisWilliams, 1983; Garlake, 1987; Parkington et al., 1994; Hampson et al., 2002; Eastwood and Eastwood 2006; Eastwood et al., 2010). Thanks to the theoretical and methodological renewal of the 1970s, approaches that, from then on, had turned to social anthropology and ethnography, shed light on the recurrence of the main designs and compositions beyond distances: a shamanic essence of which rock art would be the expression and illustration (Vinnicombe, 1976; Lewis-Williams, 1983; Lewis-Williams and Dowson, 1989; Lewis-Williams and Pearce, 2012; van den Heever, this issue; Witelson, this issue). th Since the end of the 20 century, dating has become a fundamental issue in research, in order to consider the historical depth of this ontological-religious and sociocultural framework, as encouraged by the constant renewal of methodological approaches applied to rock art. According to the current data, in Southern Africa, g r a p h i c e x p re s s i o n a p p e a re d d u r i n g t h e M i d d l e Stone Age in various sites, in the form of geometric decorations on raw materials or on objects (187 00050 000 years: Marean et al., 2007; Mackay and Welz, 2008; Henshilwood et al., 2009, 2014; D’Errico et al., 2012; Jacobson et al., 2012: Texier et al., 2013). The animals painted on the plaques of the Apollo 11 Rock Shelter in Namibia introduced figurative expression during the Late Middle Stone Age, around 30 000 years ago (Rifkin et al., 2015). Where rock art is concerned, direct dating (Mazel and Watchman, 1997; Bonneau et al., 2011) is currently associated with this practice for the Holocene Later Stone Age, although some archaeological contexts point towards initial evidence dating from the end of the Pleistocene (Walker, 1995). Many studies tend to reconsider the antiquity and, more generally, the age of these graphic productions. Direct dating is conditioned by the presence of specific elements in the way paintings are composed, which only c o n c e r n s a m i n o r i t y o f d r aw i n g s t y l e s , i n c i t i n g researchers to innovate in their methods (Mullen, this issue). When the geomorphology of the site has led to their accumulation and conser vation, archaeological deposits at the foot of or near decorated walls can hold precious data on the chrono-cultural framework of the

rock decorations (Muianga, this issue; Porraz et al., this issue), through direct or indirect evidence (e.g. fragments of decorated walls or pigment analyses respectively) (Bourdier et al., this issue; Mauran, this issue; Nhunzvi et al., this issue). The study of multiple taphonomic processes concerning the evolution of the walls and the actual paint, bring complementary indications (Bourdier et al., this issue; Mullen, this issue). Finally, the superimposition of graphics – very abundant in some sites – offers a relative chronology of the designs, for which the main challenge, as far as researchers are concerned, is to read and understand them from a chronostylistic point of view (Bourdier et al., this issue; Dudognon, this issue; Witelson, this issue). Relative or absolute, the chronological issue questions continuities and ruptures in rock art and, correlatively, the sociocultural dynamics of hunter-gatherers in the long term. It restores another chapter of the past life and history of these populations, complementary to the categories of remains traditionally tackled by archaeology (such as technical and cynegetic equipment, food and costumes). As shown by the fruitful research guided by social anthropology, rock art is also a unique window on the sociology of past populations, according to problems which are central to many current works. Who actually produced rock art? Was it part of a strictly specialised production (exper ts from the r itual and spir itual spheres)? Could other categories of people have access to walls depending on the place and time? In which spheres in the lives of these populations did rock art intervene? What was the role of rock art in the relations between individuals and communities? How did populations b e h ave vis-à-vis o l d e r i c o n o g r a p h i e s ? We re t h e s e integrated, ignored, copied or rejected? The ethnographic approach, which is constantly being refined, continues to shed much light on the symbolic, spiritual and social context underlying the creation of these iconographies and their observation (Witelson, this issue), helping to clarify the reading and deepen the interpretation of certain designs (van den Heever, this issue). Moreover, in order to apprehend the global nature and at the same time the specificities of these societies – and as such to better understand the choices made in the symbolic sphere – it is necessary to put rock art back in its archaeological and environmental contexts. The role of the iconography and the position it takes in the life of individuals, can be understood by considering how the location of the decorated sites was chosen within the environment (Jobard, this issue), and by analysing the designs compared to those already present on the walls (Dudognon, this issue). The material culture and its remains which testify to past ecosystems (animal remains, charcoals, seeds, pollens) offer precious information on the territorial organisation, the number and sociocultural function of the sites occupied, the socioeconomic spaces defined by these populations within their environment, as well as the exchange networks of goods and ideas (Mauran, this issue; Muianga, this issue; Nhunzvi et al., this issue; Porraz et al., this issue). Cross-checking these archaeological and environmental data with the regional distribution of the decorated sites, questions the ecology of societies through dynamics of socio-cultural adaptation and resilience, not only through time but also through space (Jobard, this issue; Nhamo, this issue). Finally, the technology used to produce rock art (raw materials, tools, technical processes) informs certain aspects of group sociology, on the one hand through the degree of necessary know-how, and on the other in the light of the logistic, economic and social investment – from the lear ning point of view in par ticular – implemented in these symbolic activities (Mauran, this issue; Nhunzvi et al., this issue). To date, the means to conserve and develop this exceptional heritage remain a major challenge, and are particularly central in Southern Africa, where five sets of roc k ar t of var iable geog raphic scales are part of the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites: MalotiDrakensberg Park, South Africa / Lesotho; Tsodilo, Botswana; Matobo Hills, Zimbabwe; Chongoni, Malawi; Twyfelfontein, Namibia. This classification is certainly indicative of the importance of the underlying heritage, cultural, economic and social issues pertaining to these sites. In this light, the same taphonomic processes, which limit considerably our understanding of the paintings, are still operating and are even aggravated by increased tourism in these sites (Bourdier et al., this issue; Dudognon, this issue; Duval & Hœrlé, this issue; Kumalo et al., this issue; Mauran, this issue). The different conservation actors must constantly innovate in order to find permanent material and administrative solutions,

introduction

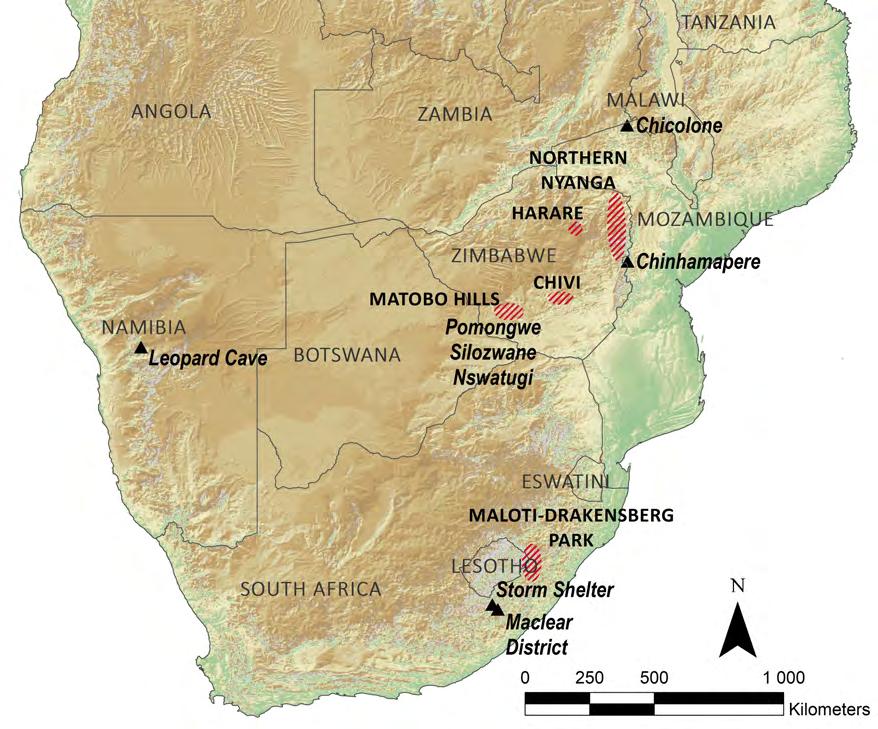

Location of sites discussed in the issue (image: L. Jobard)

making it possible to adapt to the new human and financial logistical realities (Duval & Hœrlé, this issue; Kumalo et al., this issue). With the increasing tourist phenomenon, the need to take social and economic repercussions into account for local populations, is becoming all the more acute (Duval & Hœrlé, this issue; Bourdier et al., this issue). This special issue intends to be a reflection on the plurality of approac hes and scales of analysis, as implemented in several ongoing research works on the rock art of hunter-gatherers in Southern Africa. These works are carried out by a new generation of young researchers and students from Africa and Europe, many of whom receive support from IFAS-Research. A majority of them are focusing on Zimbabwe, which testifies to the renewed scientific dynamism found in this country, where archaeological activities had, unfortunately, neglected rock art these past decades. Several contributions are part of the Franco-Zimbabwean interdisciplinary programme MATOBART (Bourdier, Machiwenyika, Nhamo and Porraz co-ord.), working in the Matobo Hills. This programme which receives the support of the French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, the Institut Universitaire de France, the Ambassador of France in Zimbabwe and IFAS-Research, using an integrated approach, combines archaeological research, university training, conser vation and development. Like other prog rammes presented in this publication, it is a testimony of the renewal of scientific co-operation dedicated to this archaeological heritage, which has become symbolic of the Prehistory of the African continent.

Bibliography

BLEEK, W. H. I., 1874, “Remarks on Orpen’s Mythology of the Maluti Bushmen”, Cape Monthly Magazine, 9(49) p. 10-13. BLEEK, W. H. I., 1932, “Customs and beliefs of the /Xam Bushman. Part III: Game Animals”, Bantu Studies, 6, p. 233-249. BONNEAU, A., BROCK, F., HIGHAM, T., PEARCE, D. G., POLLARD A. M., 2011, “An improved pretreatment protocol for radiocarbon dating black pigments in San rock art”, Radiocarbon, 53(3), p. 419-428. BREUIL, H., 1948, “The white lady of Brandberg, South-West Africa, her companions and her guards”, The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 3(9), p. 2-11. D’ERRICO, F., GARCÍA MORENO, R., RIFKIN, R., 2012, “Technological, elemental and colorimetric analysis of an engrave ochre from the Middle Stone Age levels of Klasies River Cave 1, South Africa”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(4), p. 942-952. EASTWOOD, E.B., EASTWOOD, C., 2006, Capturing the Spoor, Rock Art of Limpopo: An Exploration of the Rock Art of Nothernmost South Africa, Cape Town, David Philip. EASTWOOD, E.B., BLUNDELL, G., SMITH, B., 2010, “Art and authorship in southern African rock art: Examining the Limpopo-Shashe Confluence Area”, in G. BLUNDELL, C. CHIPPINDALE, B. SMITH (dir.), Seeing and Knowing: Understanding Rock Art with or without Ethnography, Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, p. 75-96. EGO, R., 2000, San. Art rupestre d’Afrique australe, Paris, Adam Biro. GARLAKE, P., 1987, The Painted Caves, Harare, Modus. HAMPSON, J., CHALLIS, S., BLUNDELL, G., DE ROSNER, C., 2002, “The rock art of Bongani Moutain Lodge and Environs, Mpumalanga Province South African introduction to problems of Southern African rock-art regions”, South African Archaeological Bulletin, 57(175), p. 15-30. HENSHILWOOD, C. S., D’ERRICO, F., WATTS, I, 2009, “Engraved ochres from Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa”, Journal of Human Evolution, 57, p. 27-47. HENSHILWOOD, C.S., VAN NIEKERK, K.L., WURZ, S., DELAGNES, A., ARMITAGE, S.L., RIFKIN, R.F., DOUZE, K., KEENE, P., HAALAND, M.M., REYNARD, J., DISCAMPS, E., MIENIES, S.S., 2014, “Klipdrift Shelter, southern Cape, South Africa: Preliminary report on the Howiesons Poort layers”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 45, p. 284-303. HENSHILWOOD, C. S., D’ERRICO, F., VAN NIEKERK, K., DAYET, L., QUEFFELEC, A., POLLAROLO, L., 2018, “An abstract drawing from the 73,000-year-old levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa”, Nature, 562, p. 115-118. JACOBSON, L., DE BEER, F.C., NSHIMIRMANA, R., HORWITZ, L.K., CHAZAN, M., 2012, “Neutron tomographic assessment of inclusions on prehistoric stone slabs: a case study from Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa”, Archaeometry, 55(1), p. 1-13. LEWIS-WILLIAMS, J. D., 1983, The Imprint of Man: The Rock Art of Southern Africa, Cambridge, University Press. LEWIS-WILLIAMS, J. D., DOWSON, T. A., 1989, Images of Power: Understanding Bushman Rock Art, Southern Book Publishers, Johannesburg. LEWIS-WILLIAMS, J. D., PEARCE, D. G., 2012, “Framed idiosyncrasy: method and evidence in the interpretation of San rock art”, South African Archaeological Bulletin, 67(195), p. 75-87. MACKAY, A., WELZ, A., 2008, “Engraved ochre from a Middle Stone Age context at Klein Kliphuis in theWestern Cape of South Africa”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 35, p. 1521-1532. MAREAN, C.W., BAR-MATTHEWS, M., BERNATCHEZ, J., FISHER, E., GOLDBERG, P., HERRIES, A.I.R., JACOBS, Z., JERARDINO, A., KARKANAS, P., MINICHILLO, T., NILSSEN, P.J., THOMPSON, E., WATTS, I., WILLIAMS, H.M., 2007, “Early human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene”, Nature, 449, p. 905-908. MAZEL, A. D., WATCHMAN, A. L., 1997, “Accelerator radiocarbon dating of Natal Drakensberg paintings: results and implications”, Antiquity, 71(272), p. 445-449. ORPEN, J. M., 1874, “A glimpse into the mythology of the Maluti Bushmen”, Cape Monthly Magazine, 9(49), p. 1-13. PARKINGTON, J.E., YATES, A., MANHIRE, A., 1994, “Rock painting and history in the south-western Cape”, in T. DOWSON, D. LEWIS-WILLIAMS (dir.), Contested Images, Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, p. 29-60. RIFKIN, R., HENSHILWOOD, C., HAALAND, M., 2015, “Pleistocene figurative art mobilier from Apollo 11 cave, Karas region, Southern Namibia”, South African Archaeological Bulletin, 70(201), p. 113-123. TEXIER, P-J., PORRAZ, G., PARKINGTON, J., RIGAUD, J-P., POGGENPOEL, C., TRIBOLO, C., 2013, “The context, form and significance of the MSA engraved ostrich eggshell collection from Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 40, p. 3412-3431. VINNICOMBE, P., 1976, People of the Eland: Rock Paintings of the Drakensberg Bushmen as a Reection of their Life and Thought, Pietermaritzburg, University of Natal Press. WALKER, N. J., 1995. “Late Pleistocene and Holocene hunter-gatherers of the Matopos: An archaeological study of change and continuity in Zimbabwe”, Studies in African Archaeology, 10, Uppsala.