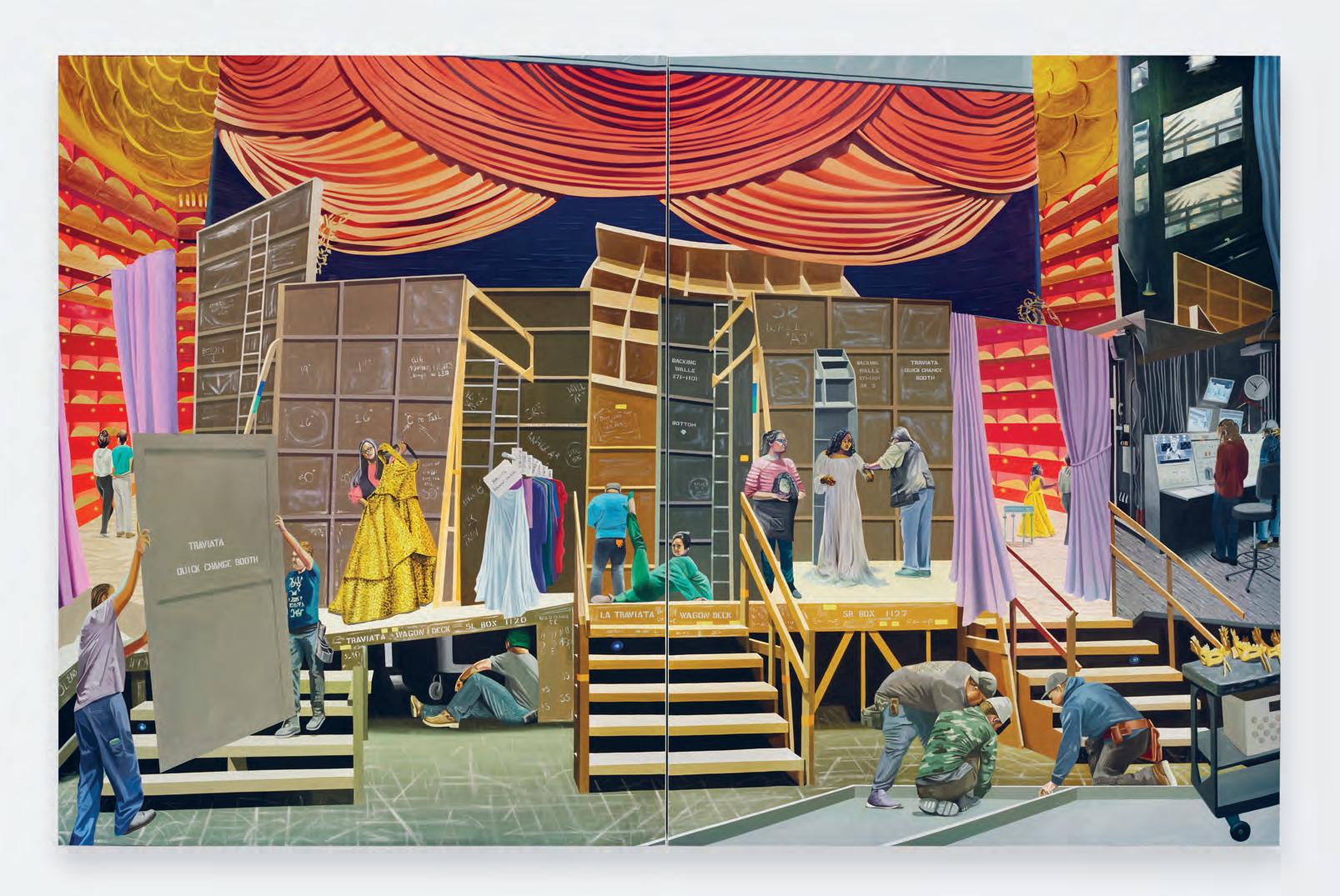

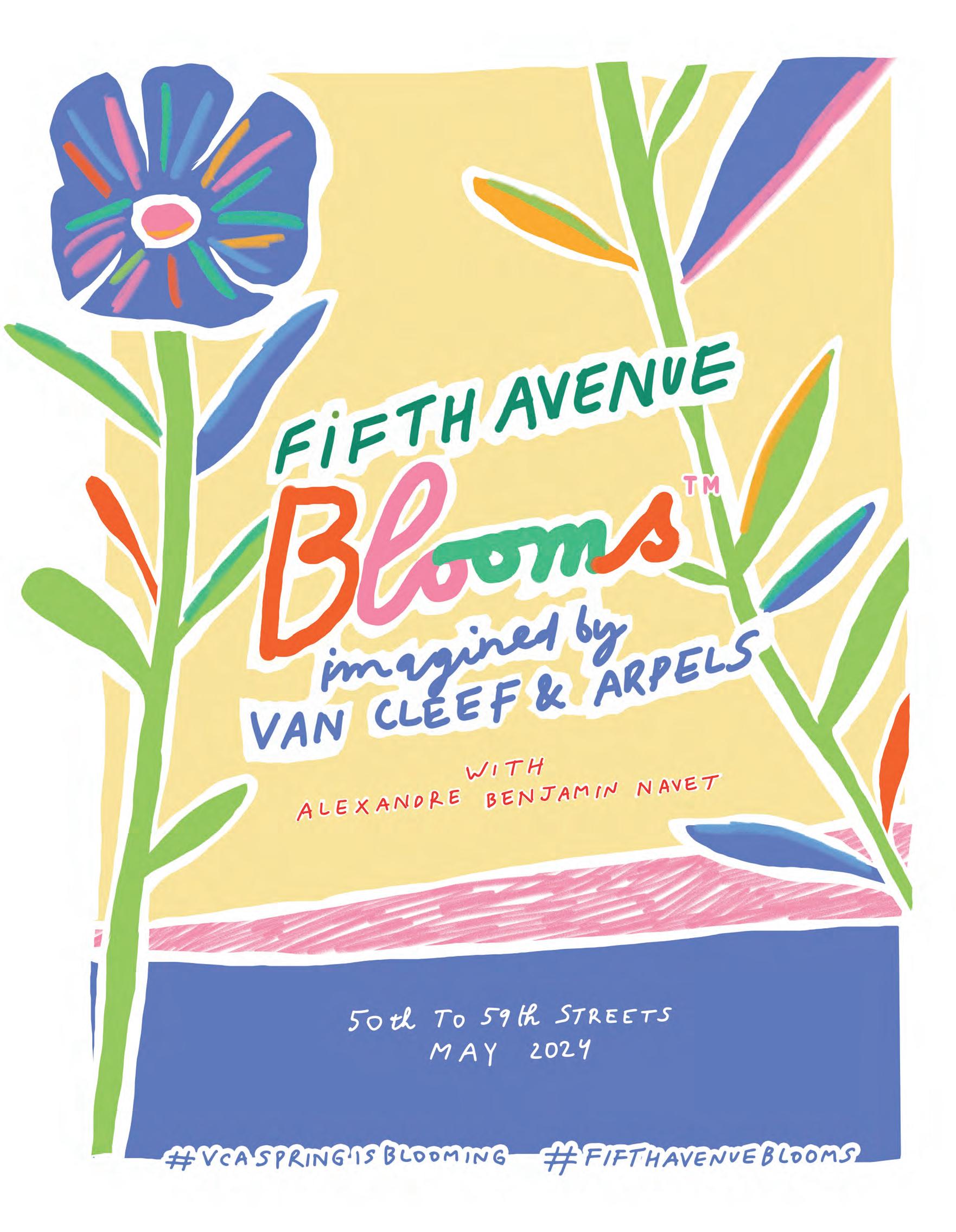

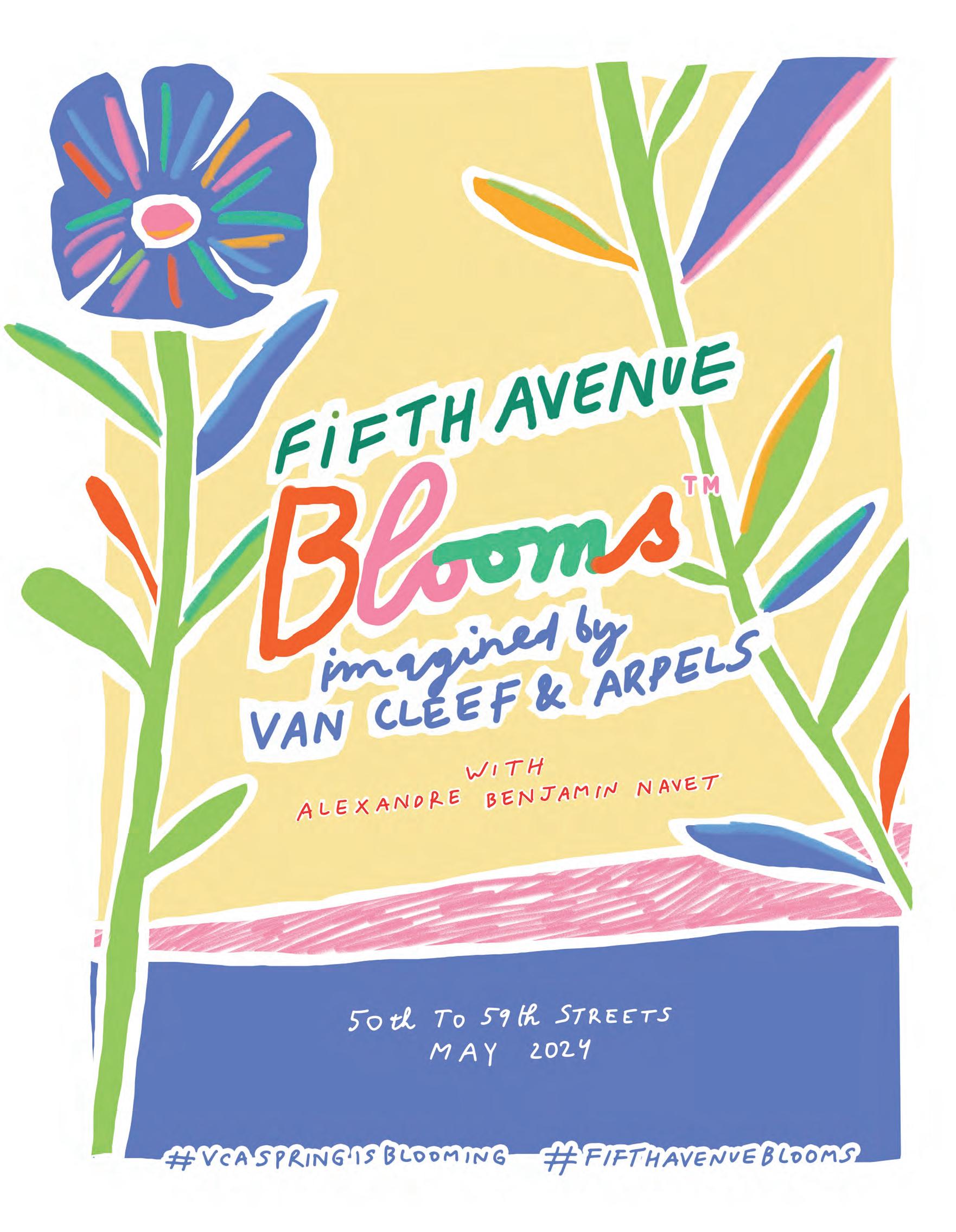

Matty Davis Takes on The High Line Dodie Kazanjian at the Met Opera

Ellen Fullman’s String Theory Performance Space ’s Next Act

Matty Davis Takes on The High Line Dodie Kazanjian at the Met Opera

Ellen Fullman’s String Theory Performance Space ’s Next Act

THE SHED, NEW YORK MAY 1–5, 2 0 24

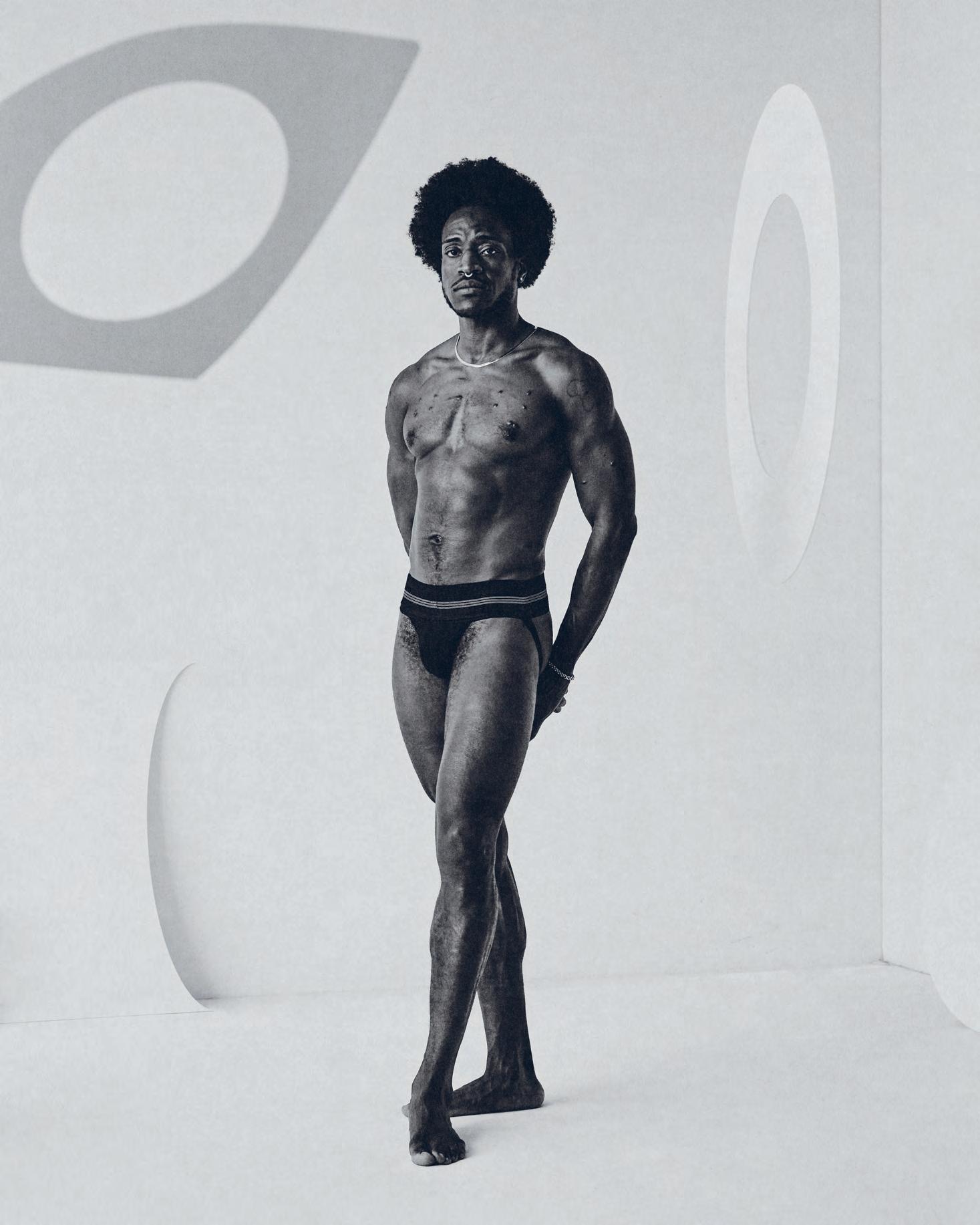

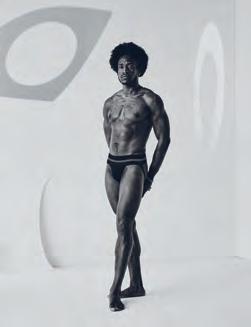

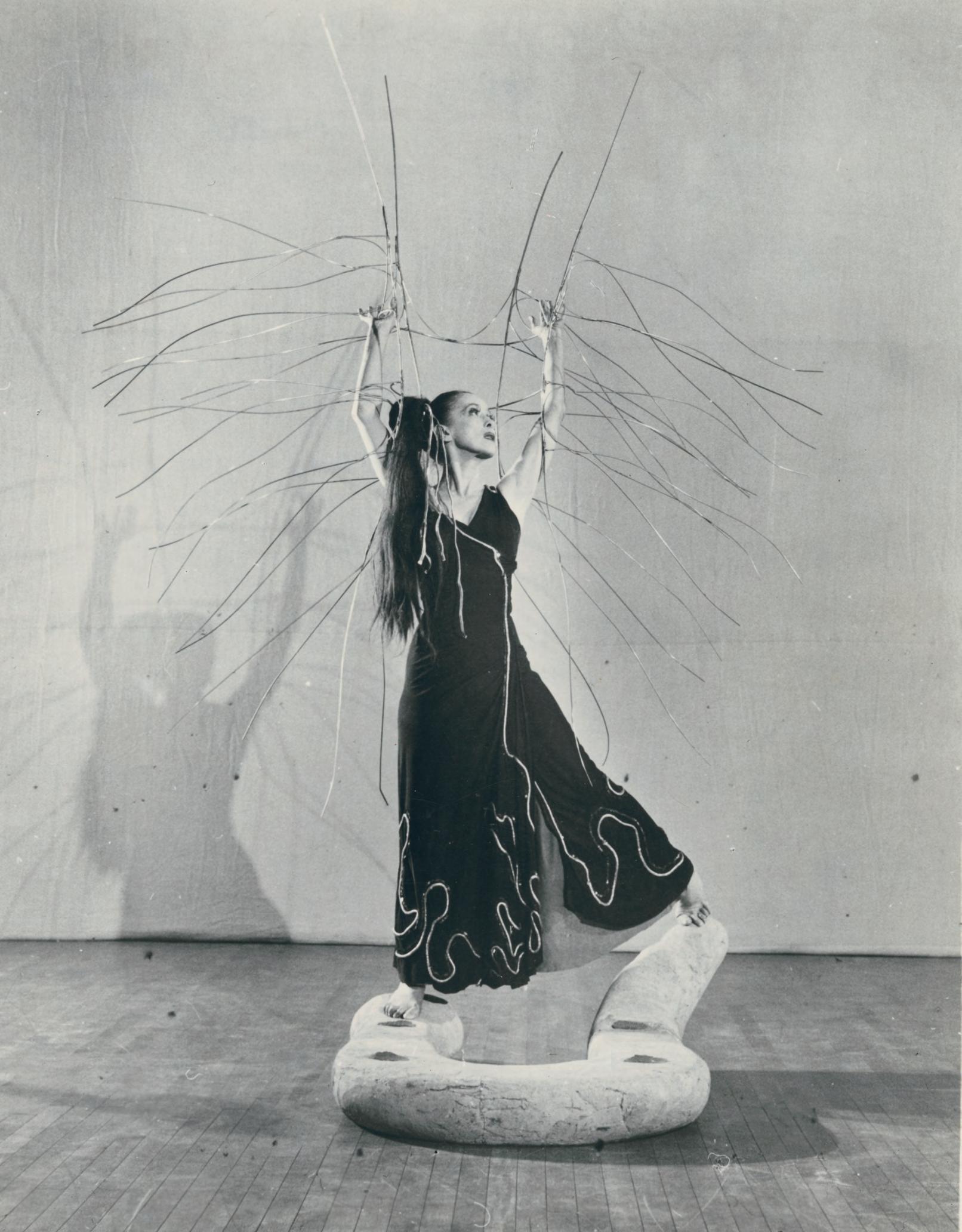

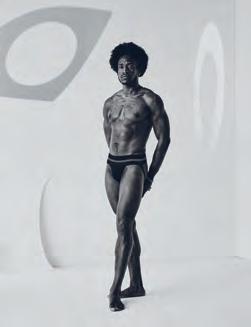

Isamu Noguchi as Set Designer Performer Portraits by Tess Ayano

dior.com –800.929 dior (3467)

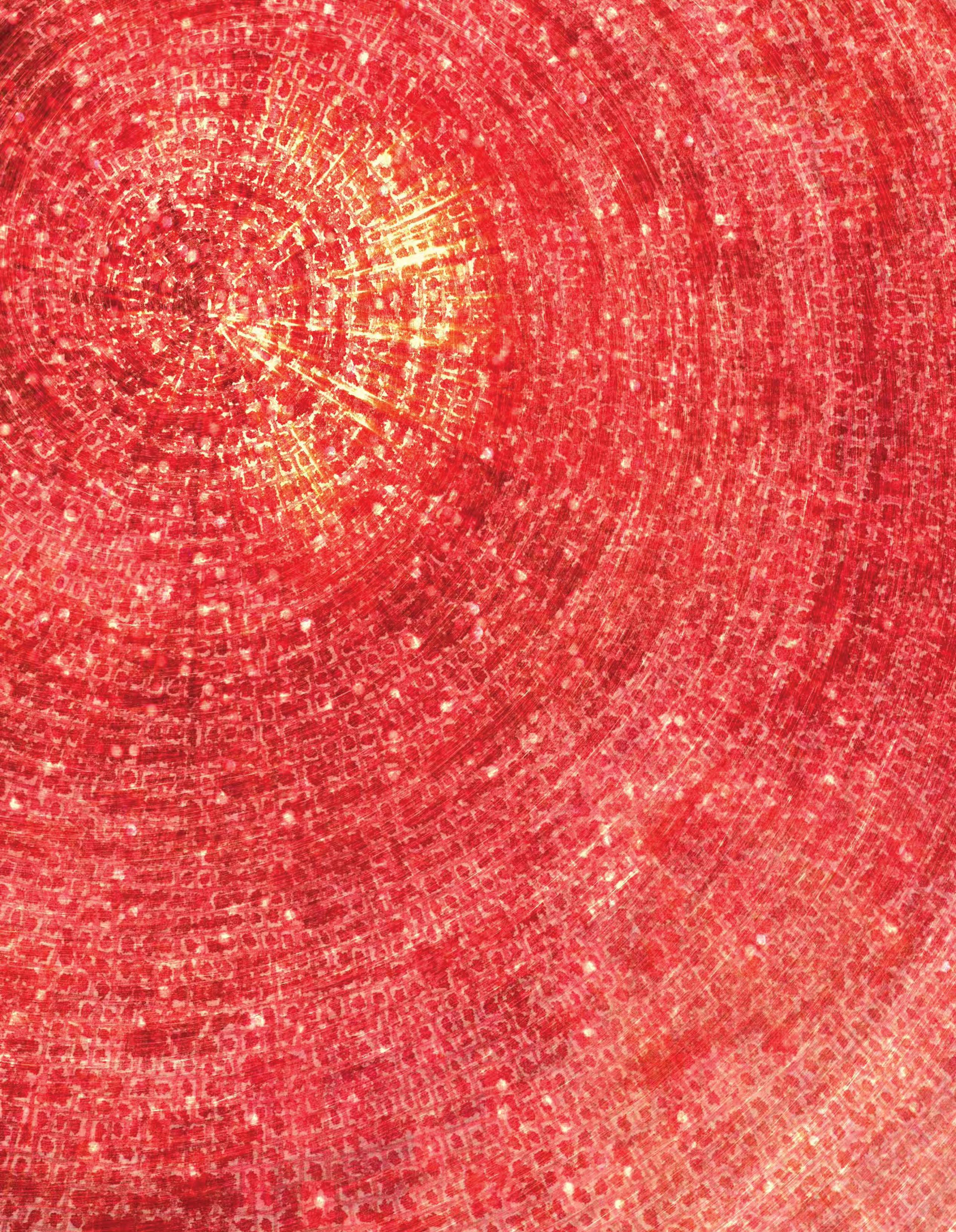

ROSE DES VENTS COLLECTION

gold, pink gold, white gold, diamonds and ornamental stones.

Yellow

PARTICIPANT: Jason Statham, Actor

WEARING: 440T1 Panama Tinto Terra Stone Island Closed Loop Project

LOCATION: London, 51.5072*N 0.1276*W

QUESTION 06 OF 100

WHAT COULDN’T YOU LIVE WITHOUT? COMEDY.

QUESTION 19 OF 100

WHAT ARE YOU READING? CARNIVORE MD.

QUESTION 20 OF 100

WHO ARE YOUR INSPIRATIONS? BRUCE LEE AND WIM HOF.

QUESTION 22 OF 100

WHAT THOUGHTS ARE ON YOUR MIND RIGHT NOW? THAILAND.

QUESTION 26 OF 100

WHAT DO YOU WANT TO SUSTAIN? HEALTH.

QUESTION 36 OF 100

WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE CITY IN THE WORLD? LONDON.

QUESTION 42 OF 100

WHICH BUILDING WOULD YOU LIKE TO LIVE IN?

CASA M BY VINCENT VAN DUYSEN.

QUESTION 65 OF 100

WHEN YOU NEED INSPIRATION, WHERE DO YOU GO? MARTIAL ARTS.

QUESTION 68 OF 100

WHAT DID YOU LEARN FROM YOUR PARENTS AND/OR GRANDPARENTS? WORK HARD AND BE ON TIME.

QUESTION 80 OF 100

WHAT ARE YOU GRATEFUL FOR? MY FRIENDS, MY FAMILY, MY KIDS.

QUESTION 92 OF 100

WHAT IS SELF-CARE TO YOU? THE GYM.

Original research commissioned by:

A RESEARCH PROJECT IN 100 QUESTIONS

PROJECT CONTINUES AT STONEISLAND.COM

PARTICIPANT: Arco Maher, Stone Island Archivist

WEARING: 431T1 Panama Tinto Terra Stone Island Closed Loop Project

LOCATION: London, 51.5072*N 0.1276*W

QUESTION 21 OF 100

WHAT DO YOU COLLECT? VINTAGE STONE ISLAND.

QUESTION 28 OF 100

WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE SEASON? WINTER, I LOVE LAYERING CLOTHING.

QUESTION 33 OF 100

DO YOU PREFER WORDS OR IMAGES? OR BOTH?

DEFINITELY IMAGES. I ALWAYS LOOK FOR OLD MAGAZINES AND ARCHIVE PHOTOGRAPHS.

QUESTION 36 OF 100

WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE CITY IN THE WORLD? KYOTO, JAPAN.

QUESTION 55 OF 100

WHO IS THE SMARTEST PERSON YOU KNOW? MY FATHER.

QUESTION 56 OF 100

WHAT’S THE BEST WAY TO OVERCOME FEAR? TAKING RISKS.

QUESTION 60 OF 100

WHICH COLOUR MAKES YOU FEEL ENERGISED? GREEN.

QUESTION 61 OF 100

DO YOU HAVE A FAVOURITE TEXTILE? MONOFILAMENT MESH.

QUESTION 68 OF 100

WHAT DID YOU LEARN FROM YOUR PARENTS AND/OR GRANDPARENTS?

POSITIVITY AND THE IMPORTANCE OF A TIGHT FAMILY UNIT.

QUESTION 75 OF 100

CLASSIC OR MODERN? OR BOTH?

VINTAGE WITH A SPRINKLING OF MODERN.

A RESEARCH PROJECT IN 100 QUESTIONS

PROJECT CONTINUES AT STONEISLAND.COM Original research commissioned by:

Iconic New York City Real Estate

ce@compass.com Nick Gavin is a real estate licensee affiliated with Compass. Compass is a licensed real estate broker and abides by Equal Housing Opportunity laws. Located at 110 Fifth Avenue, 3rd Fl. NY, NY 10011

nickgavinoffi

CONTENTS

“I’m suspicious of things that make sense,” said the New York-based artist Pope.L, who passed away this year aged 68. I’ve often felt that performance art, in which Pope.L excelled, has a special ability to be ambivalent, avoiding a single meaning. A lot about the world today doesn’t seem to “make sense:” perhaps performance art has a particular role to play in it again.

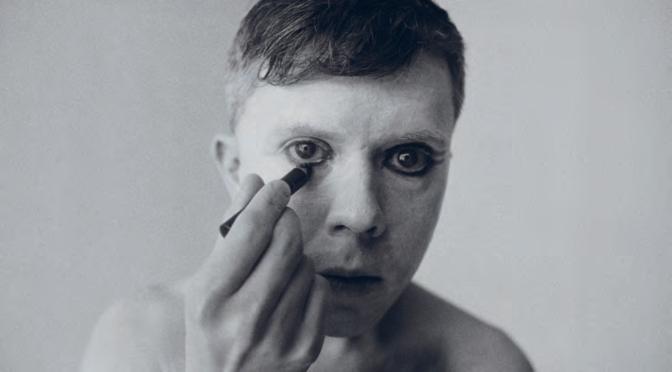

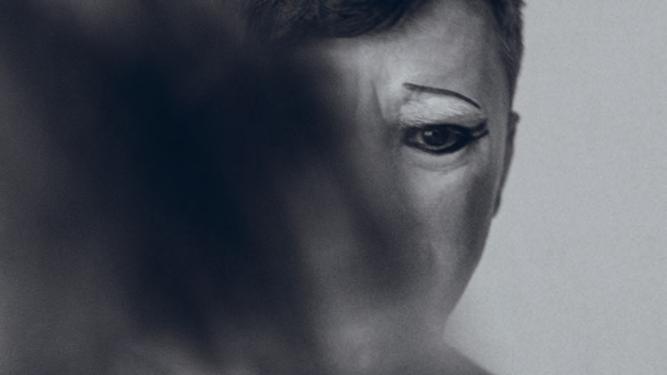

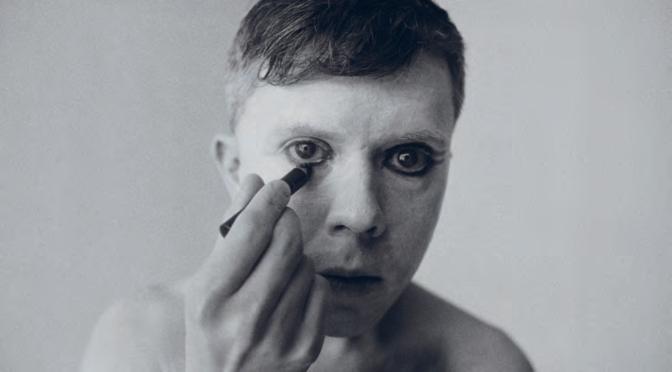

The program for Frieze New York 2024 has a special emphasis on performance, including a new, co-commissioned performance by Matty Davis on the High Line (p.16), a collaboration with Performance Space New York (p.20) and a concert by Ellen Fullman (p.13). Picking up on this theme, the issue explores the iconography of Alvin Ailey (p.52), how galleries are embracing live art (p.10) and Dodie Kazanjian’s work to put contemporary art and opera in dialogue (p.50). Tess Ayano’s story on rising performance stars produced the portrait of Cole Escola on our cover. It reminds me a little of Peter Hujar’s images of Ethyl Eichelberger: both, like Pope.L, lost too young. Perhaps another thing performance art can do right now is remind us to cherish the living.

Matthew McLean, Creative Director, Frieze Studios & Editor, Frieze Week

9 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK 10 Key Performance Indicators Live art meets commercial 13 String Theory Ellen Fullman wires up Artists Space 14 Future Facing The new CEO of The Shed, Max Hodges 16 Live Wire Matty Davis’s High Line x Frieze commission 19 Vote of Confidence Artists for democracy 20 A Return to Intimacy Performance Space’s Pati Hertling and Taja Cheek 22 Paper Gods The Bread and Puppet Theater’s urgent work Global Partners Global Media Partner Global Lead Partner Deutsche Bank On the Cover Cole Escola photographed by Tess Ayano, 2024 Frieze Week is printed in Canada by Imprimerie Solisco and published by Frieze Publishing Ltd © 2024. The views expressed in Frieze Week are not necessarily those of the publishers. Unauthorized reproduction of any material is strictly prohibited.

16 26 34 40 24 Dobel 26 Figuring It Out Together Collectors Lisa Young and Steven Abraham 33 Hot Tickets Great museum shows 34 Skin Deep How avant-garde art embraced self-care 36 On Point Martha Graham and Isamu Noguchi 40 Show Time New York’s performers by Tess Ayano 50 A Brief History of Gallery Met Art at the opera 52 What Images Are Made Of Jimmy Robert on Alvin Ailey Frieze New York Partner Official Partner of Focus

As the likes of Sarah Michelson and Nora Turato sign with blue-chips, and dedicated programs and performance residencies spring up, Cassie Packard asks: are commercial galleries embracing a new approach to live art?

KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS

It is not new for commercial galleries to present performance art. A number of early works that are now considered part of the canon debuted in such settings; New York witnessed the premieres of Simone Forti’s See-Saw (1960) at Reuben Gallery, Allan Kaprow’s Yard (1961) at Martha Jackson Gallery, Vito Acconci’s Seedbed (1972) at Sonnabend Gallery and Joseph Beuys’s I Like America and America Likes Me (1974) at René Block Gallery, to name but a few examples.

However, in recent years, especially in the wake of the Covid-19 lockdowns and the hunger they spurred for live events and communal gathering, there has been a shift in the extent to which commercial galleries are emphasizing live performance in their programs. Among blue-chip and

mega galleries which are accustomed to playing a producer role on a grand scale (of exhibitions, publications, public programs, culinary experiences and more) and capable of financially supporting work that is not only difficult or impossible to sell, but also potentially expensive to produce this shift has manifested in the formation of dedicated performance programs, the commissioning of new pieces and even the creation of residencies.

Consider Pace Live, launched by Pace in 2019. This performance and event program, which was initially housed at the gallery’s New York headquarters but has since become rhizomatic, is led by Mark Beasley, formerly curator of media and performance at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. “The gallery is grounded

in the early days of performance and happenings in New York,” Beasley tells me via email, highlighting its representation of Claes Oldenburg, Lucas Samaras and Robert Whitman.

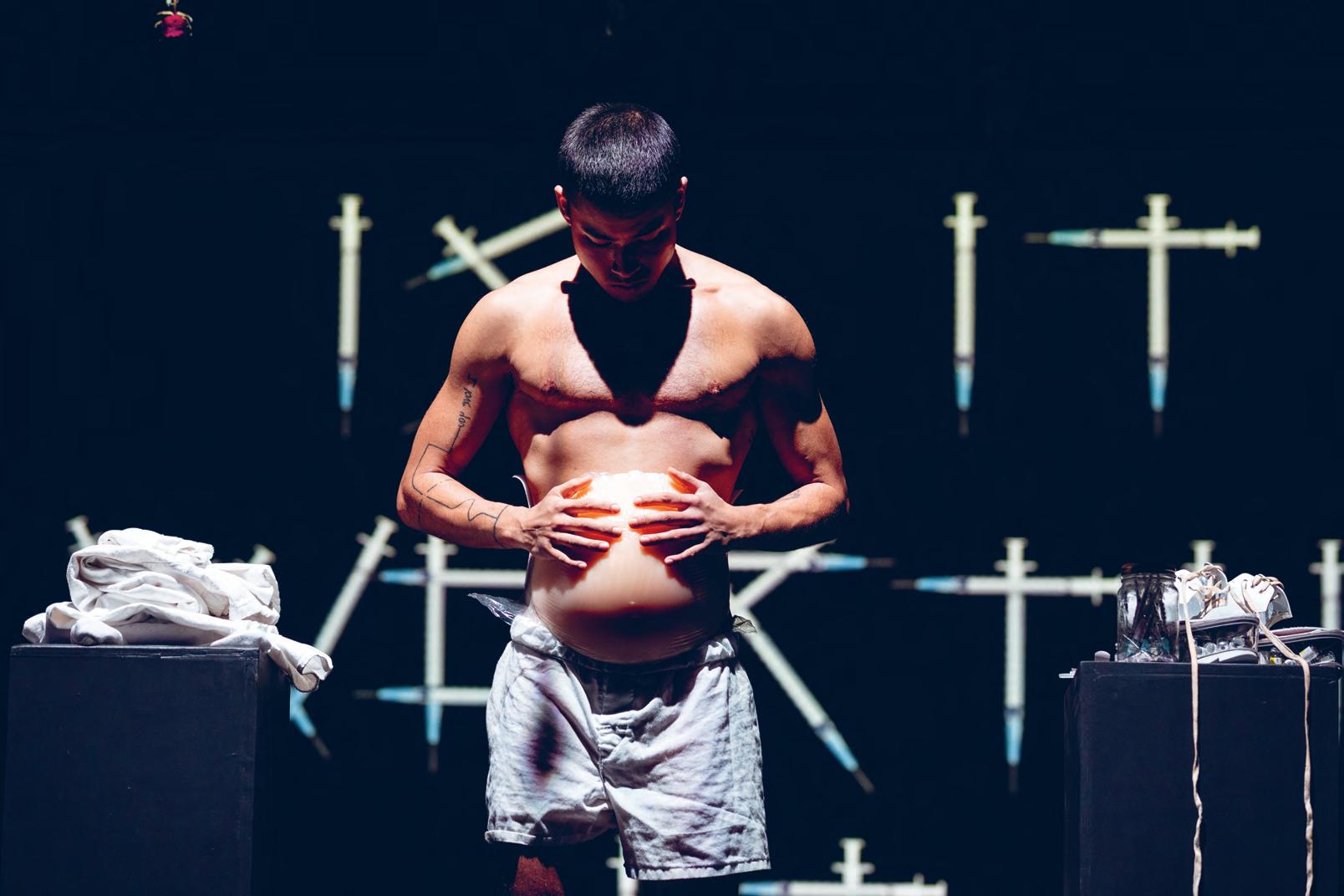

Pace Live mounts reperformances of historic works last year restaging Whitman’s American Moon (1960) amid a recreation of the original set as well as new, responsive works, such as Miles Greenberg’s Fountain II (2023), which is inspired by Hermann Nitsch’s oeuvre and was presented alongside Pace’s exhibition of the Viennese actionist’s work last spring. “Often these performances are one-off events,” says Beasley. “However, sometimes we plan a restaging or the event develops over time. There’s a natural fluidity that allows for the work to move

beyond the gallery and into other spaces, from public venues to biennials.”

Russell Salmon, director of public programs at Hauser & Wirth, likewise points out that performance is in the gallery’s DNA with artists like Kaprow and Paul McCarthy. Hauser & Wirth’s West 18th Street outpost in New York, which opened last year, features an amphitheater for public programs including performance. The gallery also launched The Performance Project in a dedicated space at its Downtown Los Angeles location in 2022; projects have ranged from Martin Creed’s Life Is Soft (2022–ongoing) to Autumn Breon’s Protective Style (2023). Hauser & Wirth additionally invites artists to respond to exhibitions. For example, painter Pat Steir’s passion for poetry and music led to poet Anne Waldman and composer and saxophonist James Brandon Lewis being commissioned to perform in dialogue with her 2022 exhibition in New York. Such an approach occasions new work and fosters cross-disciplinary dialogue while drawing more visitors to the shows themselves.

Sarah Michelson and Nora Turato are both predominantly known for their experimental performance work: Michelson as a choreographer and dancer whose work engages with architecture, dance history and dance-as-labor, and Turato for performances that grapple with the voids, slippages and elasticities of language. Last year, they joined the rosters of David Zwirner and Sprüth Magers, respectively.

“What I think is being recognized with wider gallery representation of artists who work with performance,” says Turato by email, “is that, while performance may not fall into a category of traditional object-based art and any marketable connotations that may hold, it can and often does bring people into the galler y, create engagement with the program and draw in a diverse audience. I also think galleries that see value in supporting these ways of working are committed to and trusting of their artists, beyond market persuasions.”

MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK 10 GALLERIES

Below Nora Turato, Cue The Sun, 2023, performed at the New York Society for Ethical Culture as part of the Performa Biennial. Courtesy: the artist and Performa; photograph: Walter Wlodarczyk

Opposite Miles Greenberg, Fountain II 2023, performed at Pace Gallery, New York, as part of “Hermann Nitsch: Selected Paintings, Actions, Relics, and Musical Scores, 1962–2020.” Courtesy: Pace Gallery

Michelson showed the multimedia performance Oh No Game Over (2021) at David Zwirner in New York for five days in 2021, having developed the piece on site for several months beforehand.

The year prior, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis acquired Michelson’s first “object-based artwork,” the expanded environment /\ March 2020 (4pb) (2020), made specifically for their spaces. As a newly represented artist, she is helping to build a residency program for other dancers to work and perform in David Zwirner’s galleries, and premiered a work of her own at the Los Angeles gallery this January.

From Yves Klein’s “Anthropometry” paintings (1960) to Yoko Ono’s written event scores, “performance was always hiding in plain sight” in museums and galleries, says RoseLee Goldberg, who founded New York nonprofit Performa in 2004, when we spoke by phone. Noting that artists have historically been attuned to the relationship between performance and objects, she underscores that when Performa commissions artists some of whom are primarily painters or sculptors to make performances for its biennial, the undertaking should feed, rather than interfere with, any object-making practices.

Turato, who presented Cue The Sun (2023) at last year’s Performa, views her performances as inextricably linked to her broader body of work, which includes enamel panels, wall paintings and videos based on performance scripts. While Turato’s performances themselves cannot be sold, when artists do elect to sell their performances, what collectors receive can take a variety of forms, including photographic and video documentation, archival ephemera and props, written and verbal instructions, and intellectual property rights agreements; a discussion of the work’s parameters and production requirements is often involved. The growing interest in collecting performance has even catalyzed focused art fairs, such as Performance Exchange in London and A Performance Affair in Brussels.

Around the same time Performa was founded, London’s Tate Modern introduced a live performance program, in 2003, and made its first performance acquisition, Roman Ondak’s Good Feelings in Good Times (2003), when the piece was re-enacted at Frieze London in 2004. A few years later, New York’s Museum of Modern Art acquired Tino Sehgal’s performance Kiss (2003), inaugurated a workshop on performance in institutions and grew its media department to include performance. Such assertions of the art-historical significance of performance have likely encouraged galleries to double down on the genre, as did a post-lockdown drive toward the live, the expanded role of the gallery in the experience economy and, most importantly, galleries’ commitments to the interests and practices of the artists whom they support.

“The whole framework of the art world is changing so much,” says Goldberg. “Performance brings people together, has a direct relationship to the public, and allows the issues of our age to be aired in an immediate way. I really think it’s the future.”

11 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

Cassie Packard is an arts writer. She lives in New York, USA.

Zwirner Lucas Arruda Assum Preto

2–June 15, 2024 537 West 20th Street, New York Lucas Arruda, Untitled (from the Deserto-Modelo series) 2023. Photo by Everton Ballardin. © Lucas Arruda

David

May

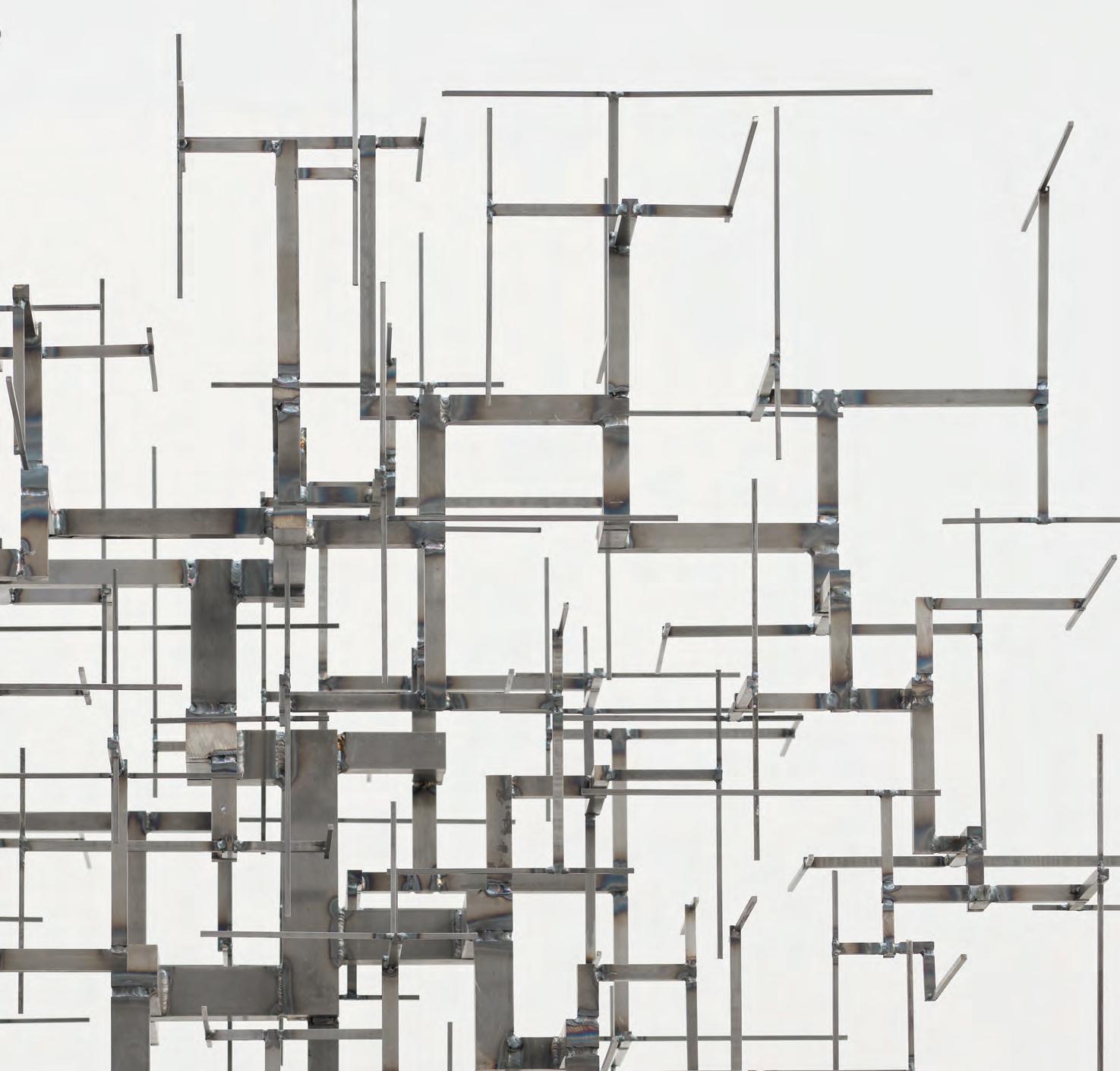

Ellen Fullman’s Long String Instrument is an epic musical installation, four decades in the making. Frieze Week in New York offers a rare chance to see Fullman bring it to life at Artists Space

STRING THEORY

An array of metal strings stretches across the room from wall to wall. As Ellen Fullman moves slowly between them, running her rosin-covered fingers across them, the sonic vibrations generate rich overtones and drones of intriguing complexity. Witnessing a performance is a transfixing and meditative experience. This is Fullman’s majestic and minimalist Long String Instrument. The musician and composer has been developing and refining it since the early 1980s. It varies in size from around 50 to 100 feet long; its strings are attached to wooden resonator boxes and are tuned in just intonation a system in which all the intervals are ratios of whole numbers.

The Long String Instrument is as much an art installation as it is a soundmaking device. Fullman, who grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, was steeped in the blues, rock and soul of the South before going to art school in Kansas City to study sculpture. In her last semester there, she created Metal Skirt Sound Sculpture, a pleated garment made of guitar strings and sheet metal, connected to a small amplifier, which she wore for her performance Streetwalker (both 1980).

In 1981, Fullman moved to New York, where she immersed herself in experimental music in the creative ferment of the downtown scene of the early 1980s. “I went a lot to Phill Niblock’s loft, Experimental Intermedia; I went to Roulette Intermedium,” she recalls in our recent conversation. “It was fantastic to be in that community.” On reading Harry Partch’s book Genesis of a Music (1949), she was inspired by the author’s iconoclastic instrument designs and began building her Long String Instrument. Since 1985, she has recorded several albums and collaborated with many composers and groups, including Keiji Haino, the Kronos Quartet, Pauline Oliveros and the Deep Listening Band and Frances-Marie Uitti.

This spring, Fullman is giving two rare collaborative performances at Artists Space in downtown Manhattan her first shows in New York since 2013. Now based in California, she says, “I’m looking forward to being in New York. I lived there for five years, so it will feel like coming home.”

On April 26, she is performing with the JACK Quartet, a New York-based string quartet specializing in new music, and on

May 3 she is playing with Konrad Sprenger, a pseudonym of the Berlin-based composer and multi-instrumentalist Joerg Hiller. Sprenger and Fullman are longtime collaborators, but the show with the JACK Quartet is a new endeavor. “I have been very excited about working with them because they specialize in just intonation,” Fullman says, “and their sound is really in tune on these unusual intervals. The quartet functions as a kind of extension of the harmony that my instrument is producing.”

For the concerts, Fullman will bring an array of wooden resonator boxes, tuning devices and strings, along with various tools and hardware. “We will mount these components directly to the walls at Artists

Space,” she explains. “The strings will be extended from wall to wall and that’s where I will walk.” Both of the pieces are brandnew works, and both are still in progress. “The Long String Instrument at the core, extending out in harmony, is the kind of form I’m interested in,” she says. “The outward movement is performed by other instruments.” Fullman has been exploring intervals that are beyond conventional Western musical harmonies and has become very interested in extending the harmonic spectrum of The Long String Instrument to the parts that other instruments are playing including resonances which emerge, seemingly by happenstance. “I’m really interested in sympathetic resonances,”

she says, “and how a frequency played by another instrument can trigger timbral changes in my instrument.”

The concerts at Artists Space offer an extraordinary opportunity to see this one-of-a-kind instrument and musician in action. Fullman promises that the shows will be immersive, exploratory experiences. In her words, “It’s going to go to a lot of different places.”

Ellen Fullman will perform at Artists Space, New York, USA, on May 3.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic. She lives in Los Angeles, USA.

13 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK FAIR PROGRAM

Below Ellen Fullman at her studio in Berkeley, 2024 Photography Ian Bates

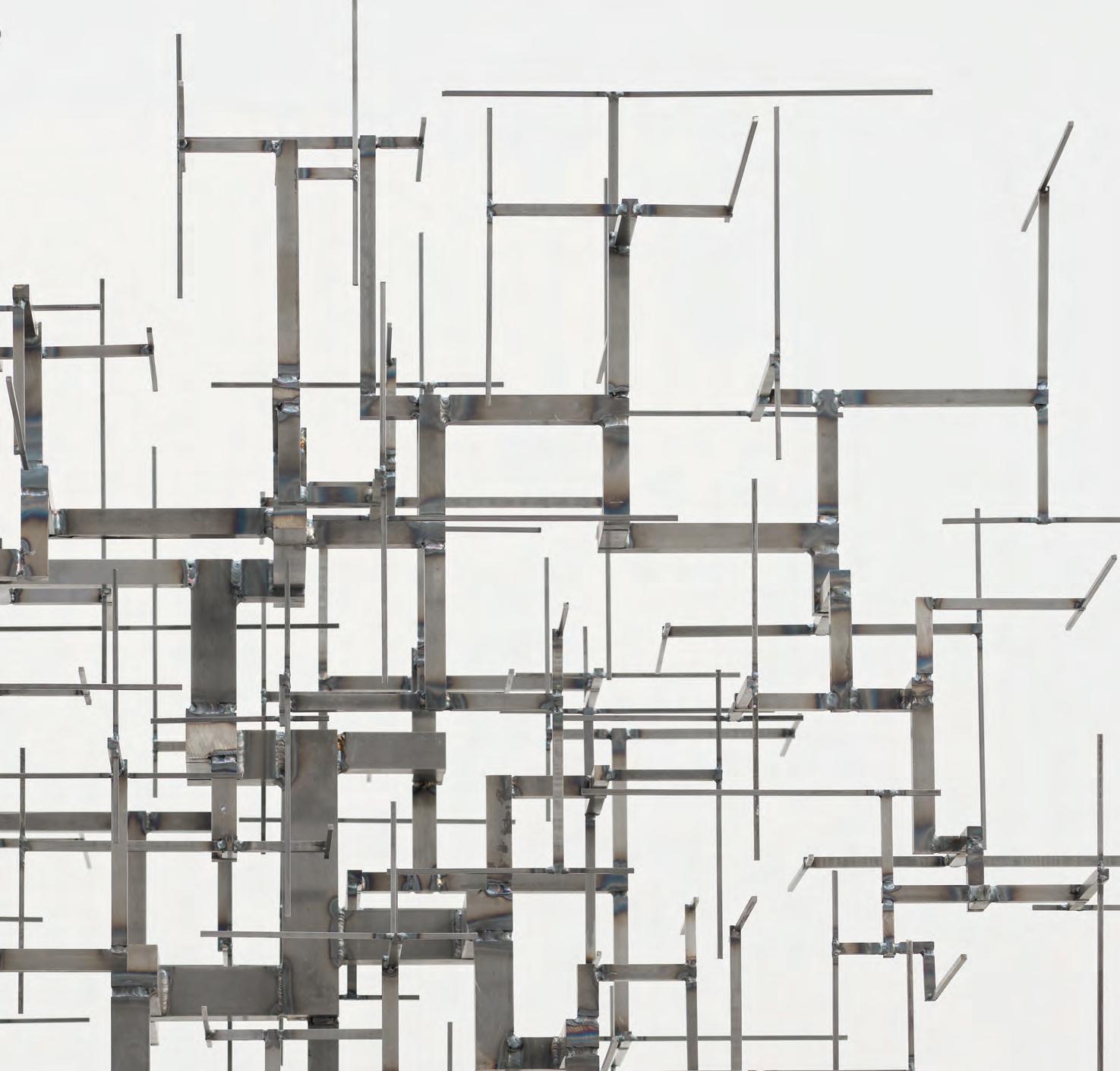

Newly joined from the Boston Ballet, The Shed’s CEO Max Hodges discusses what’s to come for the cultural institution where Frieze New York takes place: from site-specific spectacles to a new staging of King Lear

SUSAN YUNG

How was it going from your role as executive director at the Boston Ballet to The Shed? What have you been able to transfer from your experiences there?

MAX HODGES

The Shed was built to anticipate the future of art-making. When David Rockwell, Liz Diller and the team at Diller, Scofidio + Renfro created this space, they were designing for maximum flexibility, and for the interplay between different artistic genres, for scale and spectacle. We have gorgeous, column-free galleries, a 500-seatblack box, adaptable theater and a dedicated event space. The building is movable. It has a telescoping feature that, when deployed over the plaza, creates a performance or exhibition space called the McCourt, which is dazzling in its scale. All these things anticipate where artists want to be heading in the future. A lot of contemporary artists are innovating across art and technology and they’re leaving behind the old boundaries between disciplines.

I also think that The Shed has anticipated the future of audience demand. We’re at a moment when audiences want to be served in new and different ways, and they’re looking for the immersive, experiential and interdisciplinary. The Shed is built for that.

FUTURE FACING

“A lot of artists are leaving behind the old boundaries between disciplines.”

This future-facing ethos is similar to what we had at the Boston Ballet. There, it was always our aim to be moving the art form forward with commissions from a broad set of voices who were innovative in movement vocabulary and engaging with urgent topics relevant to our audiences.

Coming here has been really, really fun. We’re not bound by precedent and that is very exciting.

SY What past events at The Shed stand out for you? And what kind of performances intrigue you, generally? MH In its short life, The Shed has had more than its fair share of what I would call breakthrough cultural events. I’m thinking about the immersive 2021 exhibition “DRIFT: Fragile Future,” Tomás Saraceno’s 2022 project Particular Matter(s) and last summer’s Sonic Sphere, where we suspended an enormous, spherical concert hall: folks could climb inside, lie back and experience live or recorded music in a completely different auditory and physical environment. Some of our theatrical offerings also come to mind: David Hare’s play Straight Line Crazy, featuring Ralph Fiennes, in 2022, or, in 2023, the world premiere of Stephen Sondheim’s musical Here We Are

Personally, I’m intrigued by everything. Dance is certainly my first love but I really do love works that defy genre description, that are unbound in some way, or have us facing space in a different way. From my time at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, one of the projects I was most proud of was Doug Aitken’s sleepwalkers in 2007, which was projected onto the building’s facades.

SY How do you see The Shed evolving? Will you continue to produce events on a huge scale, such as Saraceno’s project or Sonic Sphere?

MH The answer to the second question is absolutely, yes. When I think about what’s drawing audiences back out, particularly to view live art, I see that scale and spectacle are important factors. Culturally inclined and adventurous audiences are seeking multisensory, interdisciplinary and participatory experiences. And the possibility for scale and spectacle is something that makes The Shed unique.

Commissioning site-specific works with a long duration is part of our vision going forward. We’re so young and, after the disruption of the pandemic, I really feel like we have a new beginning and are in a place from which we’ll continue to grow.

SY Can you discuss the importance of community programs at The Shed?

MH The Shed is deeply linked to the local community in many ways as a voting site and as a hub for critical city services. Open Call is one of our signature programs: it’s a biannual call for emerging artists from across the five boroughs of New York, who are working in the visual and performing arts. We have worked very hard to make sure its reach is as broad as possible and are aiming to catch these artists early, to help them accelerate and amplify their artistic voices. We have a cohort of visual artists and a cohort of performing artists, and they receive commissions and residency support from us. We staged a group show in our galleries with the visual artists last fall and, this summer, we’ll present the commissioned works from the performing artists’ residency both programs are free to the public.

SY Finally, what can you share about the future programs that you are particularly excited about?

MH I’m looking forward to continuing to expand our theatrical audience into a younger and more diverse crowd. Something that we’re experimenting with and investing in are irresistible offers for young theater patrons. For example, reserving the front rows of performances for folks under 30. After our exciting partnership with the National Theatre in London this March, which brought us Lucy Prebble’s play The Effect, I’m thrilled to welcome Kenneth Branagh this fall with his new King Lear. It’s a very intense and incisive version of Lear for a modern audience.

I feel sure its themes of power and love will resonate with audiences in the fall as much as ever.

14 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK FRIEZE PARTNER: THE SHED

Below Sonic Sphere, The Shed, New York, 2023. Courtesy: The Shed; photograph: Ahad Subzwari

Susan Yung is a writer focusing on art, dance and culture. She lives in the Hudson Valley, USA.

Max Hodges is chief executive officer of The Shed, New York, USA. She lives in New York.

The Queen of Naples, Caroline Bonaparte Murat, owned thirty-four Breguet watches.

Start with one.

Make History with us.

breguet.com

Reine de Naples 8918

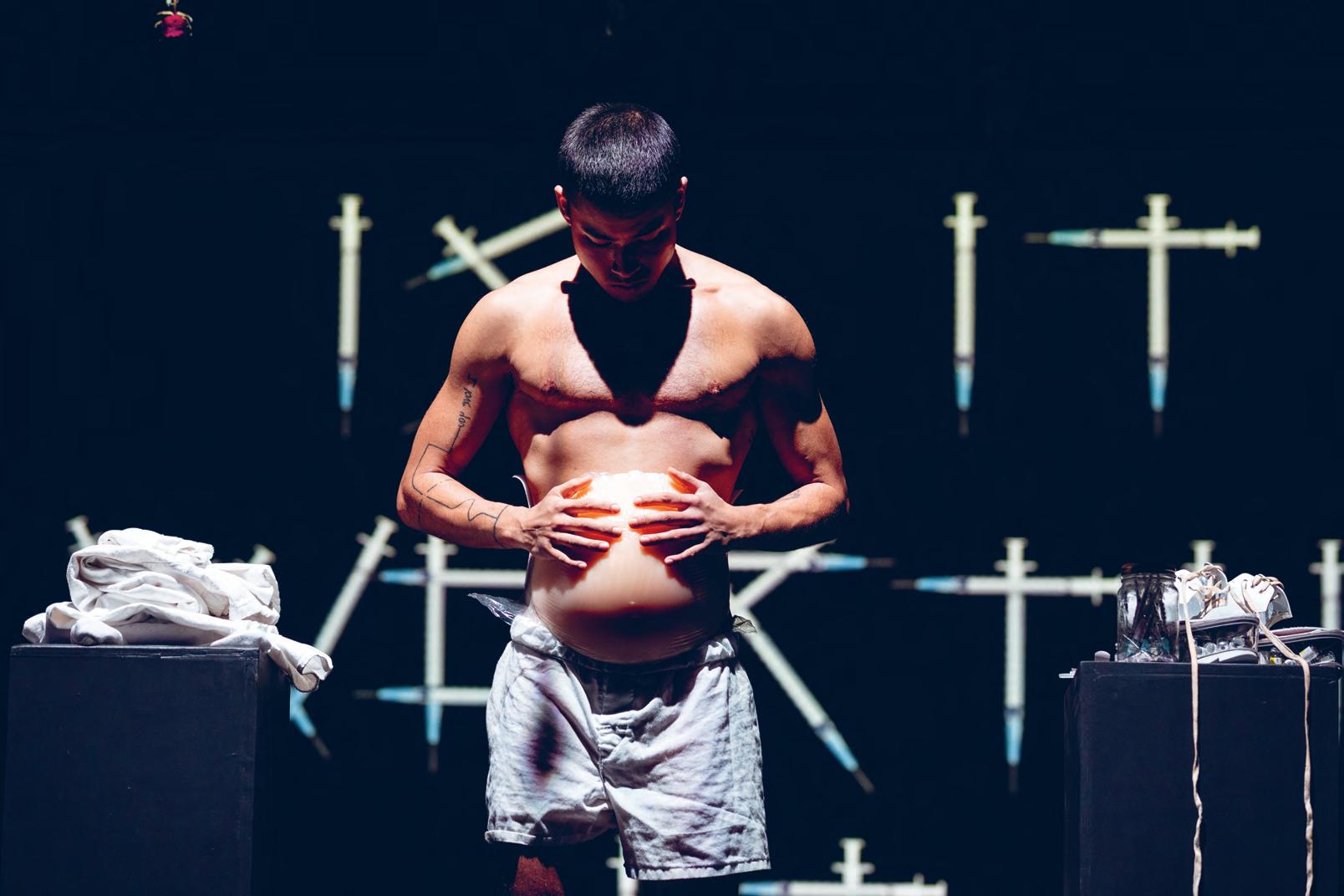

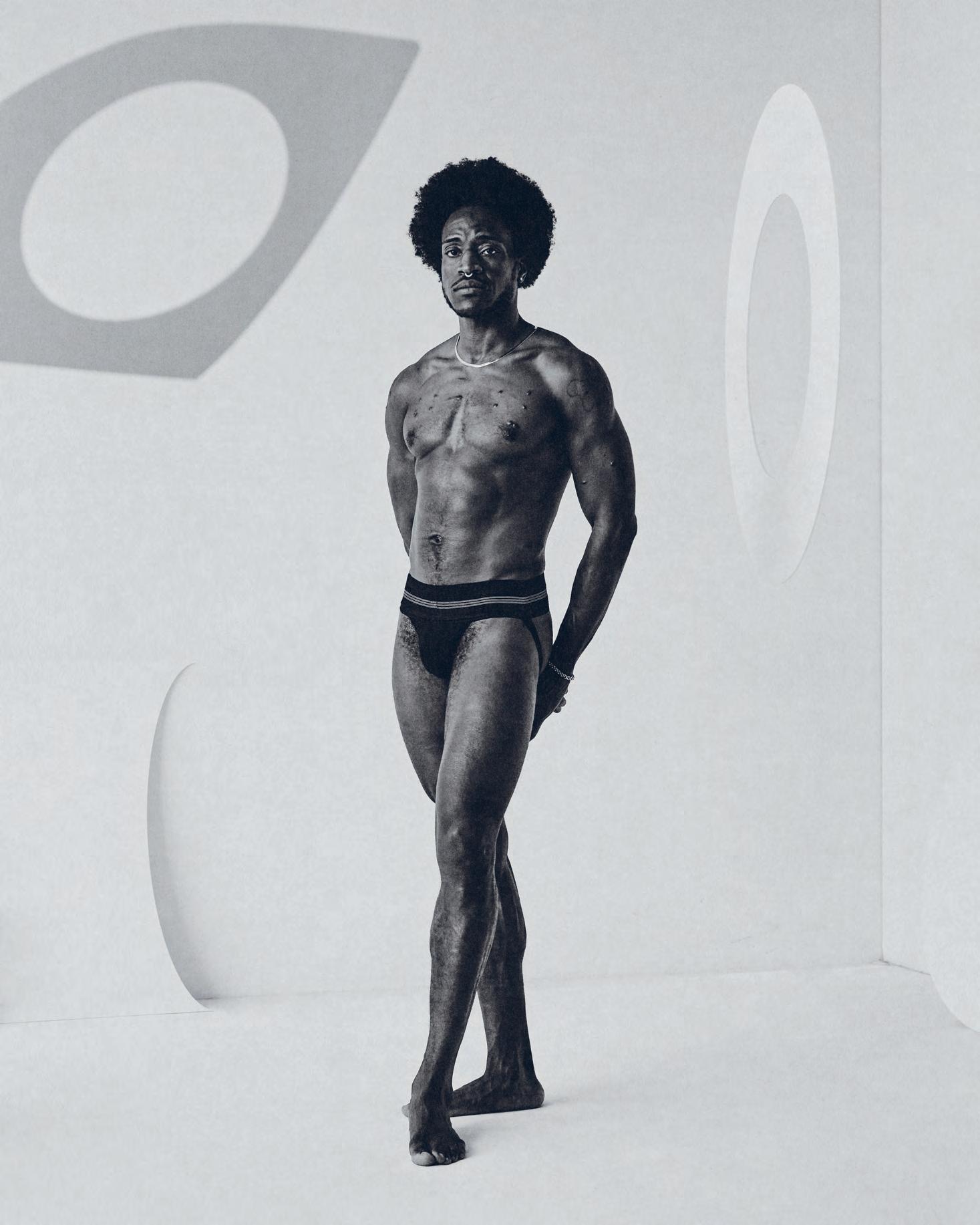

A new performance co-commissioned by Frieze and the High Line, Matty Davis’s Die No Die explores the shared dynamics that make individual selves

LIVE WIRE

Matty Davis is attempting the impossible. From lying on the ground, he tries to execute a handless kip-up arching his back, pushing from his shoulders to propel his body from horizontal to vertical. He thrusts his chest off the ground and drives his knees forward, failing a few times before fully launching himself upright. But his goal is not only to land in a standing position; rather, it is to arrive perched, hovering off-balance on the balls of his feet, and from there to catapult himself from one action of precarity into another. Davis approaches this series of movements with relentless, reckless, urgent exertion. Rather than watching his control, I witness him play at the edge of his ability, seeking possibilities of physicality that exist only in the margins of his awareness. He aims to find accidental, excessive expressivity to be surprised and undone by where his body might take him.

Davis grew up in Cranberry Township in suburban Pennsylvania, an athlete and skater who only discovered art and dance as a senior in college. His work as an artist, choreographer and performer has been commissioned and supported by venues including the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2017), Pioneer Works, New York (2017), Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2019) and KANAL Centre Pompidou, Brussels (2021). Voracious in his appetite for physical risk and effort, Davis mixes the spectacular with the quotidian. Virtuosic, ecstatic, almost sacrificial dancing happens alongside acts of tender devotion in a wide-open field, on a basketball court, in a museum or in the intimacy of a collaborator’s living room.

Frieze and the High Line have cocommissioned Die No Die, a choreographic work by Davis for five performers to be presented this May. Last year, Davis shared iterations of the project at The Momentary in Bentonville, Arkansas, and a site-specific version at the University of Iowa Ashton Cross Country Course with PE and Public Space One. In addition to the live element, which will be performed on the High Line by Davis and a cast of collaborators, a new publication and an installation of original artwork will be presented in parallel at The Shed. While performance anchors Davis’s practice, writing, photography, design and drawing are equally important. The new installation and publication are intended to be experienced in tandem with the performance work.

Davis began working on Die No Die during the early days of the pandemic, driven to examine a bodily and intellectual response to the precarity of that time. His attention focused at once on himself, his own vitality and proximity to mortality, and on the ways in which shared conditions would inevitably impact each of us differently. Davis, who spoke to me via Zoom during a research trip to the Crater of Diamonds State Park in Murfreesboro, Arkansas, talks about selfhood as being related to the geologic formation of gemstones. Die No Die stems from the

idea that the forces that shape our lives vulnerability, grief, privilege, desire, prejudice, rejection, curiosity, loss, interdependence form a network of pressurized constraints that act as a thick, constantly changing, atmosphere through which we move. As we travel through this dense space, our bodies are abraded, honed and shaped by the resistances and supports we encounter. In Die No Die, the goal seems to be to further intensify and make visible the extreme pressures that, while shared, ultimately produce us as distinct individuals.

In the 2019 publication Wood Bone Mill, which followed an eponymous performance made in collaboration with Bryan Saner who will also appear in Die No Die on the High Line Davis writes: “I’m often interested in risk, in the terms of what we can survive together, not in this macho way but in this way that requires everything you have in terms of care and sensitivity and deep listening.” There is no overarching physical aesthetic or set of capacities that his collaborators must adhere to, rather it is each person’s commitment to moving Davis’s questions/directives through their own physical research that determines their movement. He writes: “Common structure refracts particularity, revealing the wholly unique and irreplaceable nature of each life.”

The score for Die No Die has four parts. As Davis explains, the first, “‘The Critical Gesture of Arrival,’ asks each individual performer to collect their physical and psychological energy as fully and intensely as possible. It asks them then to hold it, to allow it to build, to become hard and heavy and perhaps difficult to carry until, finally, they surrender it, casting it into the performance space.” “Oppositional States,” the final action for each performer, dictates that they pass the performance on to the next participant. They must engage with one another at the point where one person concludes their performance and the next one begins. At this moment of encounter, each performer must, as Davis states, “hold a life that isn’t yours.”

The score (which also includes “A Gem” and “Send the Heart Deeper”) is designed to be successive, with each performer moving through the four parts before passing each one on. The work travels linearly along the High Line.

In as much as the work creates a process of transmission for the performers, it is designed to implicate viewers as well.

Taylor Zakarin, associate curator of High Line Art, speaks about the importance of Davis’s work traversing the length of the structure: “There is no barrier between artist and viewer. By being there, you inherently become a part of the work which speaks to the High Line’s broader mission around public art and accessibility.”

Davis is dancing and there is dirt and sweat all over his shirt and face; his hair is flying in all directions at once. He is spinning, arms open, palms facing out while his head is tilted up to look at the sky. In this position, with the force of his spiraling movement, he can’t stay upright for long. He is twisting while falling. It is both elegant and messy; his exquisite bodily awareness and lack of control are simultaneously evident. It can be shocking and exhilarating to watch.

I recognize in Davis the wonder, courage and fear that come with surrender, the desire to throw oneself into living with the hope and faith that this next risk might take you somewhere you have never been before.

16 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK FAIR PROGRAM

Below and opposite Matty Davis at his home in Brooklyn, 2024 Photography Christian Werner

Matty Davis’s Die No Die (The High Line), a performance and publication co-commissioned by High Line Art and Frieze, will be presented at the High Line, New York, USA, on April 30, May 1 and May 2

Jesse Zaritt is a dance artist and assistant professor at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia, USA. He lives in New York, USA.

ANTONY GORMLEY Aerial 30 April – 15 June 2024 White Cube, 1002 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10075

In a critical election year, Plan Your Vote marshals artists to strengthen democracy, Thara Parambi reports

VOTE OF CONFIDENCE

This year will be the biggest election year in history. A total of 76 countries will hold scheduled elections in 2024, with more than four billion people just over half of the human population being eligible to vote. In the US, voter turnout is lower than in other developed countries coming in at about 60 percent in presidential elections, as compared to 70 percent in its counterparts. There are several factors that prevent voters from participating, one of these being voter suppression, which comprises various legal and illegal efforts such as imposing strict ID laws, cutting voting times, restricting registration

and purging voter rolls to prevent eligible citizens from exercising their right to vote. In 2023 alone, 150 voter suppression bills were introduced in 32 states; in 2022, 250 restrictive bills were introduced in 27 states. These tactics disproportionately affect people of color and those from low-income backgrounds. Data shows that wealthy Americans vote at much higher rates than those who earn less and, of course, this in turn affects public policy and who it serves.

Plan Your Vote an initiative led by Christine Messineo, Director of Americas at Frieze, in partnership with Vote.org attempts

to address these issues and encourage voting. It utilizes the potent visual languages of an incredible roster of artists, including Derrick Adams, Wangechi Mutu, Calida Rawles, Laurie Simmons and Hank Willis Thomas, whose pieces are emblazoned with the text “PLAN YOUR VOTE.ORG” and available for people to download and share. Since 2020, moreover, visitors to Frieze New York and Los Angeles have been able to check and confirm their registration status and plan the logistics of voting in person or in absentia in their state. Since inception, the Plan Your Vote initiative has generated over 20 million media impressions and over 10,000 voter verifications and registrations via Vote.org.

To date, Vote.org has registered more than 4.7 million voters, verified 10.9 million voters’ registration status and helped more than 4.3 million request their mail-in ballot. In addition to providing everything Americans need to register and vote, Vote.org has also taken legal action against voter suppression in Texas, Georgia and Florida. To symbolize the nefarious, tangible impact of voter suppression tactics, last year at Frieze New York and Los Angeles visitors were given water bottles inscribed with the word “banned,” referencing a Georgia law banning the distribution of food and drinks at polling stations. The bill’s passage came on the heels of the 2020 election, when Vote.org handed out water bottles to voters who had to wait in hours-long lines to cast their ballot. The long lines were an intentional attempt to keep voters from the ballot box, the result of closed polling places in specific, targeted communities.

As Andrea Hailey, CEO of Vote.org, tells me: “The Banned water bottles were a powerful way of drawing attention to laws that are aimed at washing people out of the process and picking and choosing voters instead of letting voters pick leaders.” She continues: “Plan Your Vote has been very

impactful for us. We’ve been able to work with artists, museums and institutions to register thousands of people, many of whom we wouldn’t have been able to reach otherwise. The coalition that has come together here joins creative forces with corporate leaders and schools from throughout America that’s the way you fight encroaching authoritarianism. It’s so important to show what’s happening in this country and to make sure that everyone can have their voice heard and knows that they can use a trusted, nonpartisan source to do that.”

The success of politics demands a capability to reimagine the world. Such thinking is innate to artists, making their collaborations with politicians and policymakers a petri dish for radical and innovative action. The artist-as-activist is a role that is well documented throughout history. Joseph Beuys was one such firm believer in the political power of art and he encouraged his students to engage in activism alongside him. In his 1973 work Demokratie ist lustig (Democracy Is Merry), we see a screen-printed photograph of a smiling Beuys being escorted away from a sit-in with his students, which protested the undemocratic institutional practices at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf Following the sit-in, Beuys was dismissed from his post. As certain as it is that democracy will always be under siege, so it is that artists will be ready to take up arms in its defense.

For the third consecutive year, Vote.org will be on site at Frieze New York registering voters. To download and share artworks from the Plan Your Vote campaign, visit: planyourvote.org

Thara Parambi is a writer and artist. She lives in London, UK, and Los Angeles, USA.

19 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK FAIR PROGRAM

Below Christine Sun Kim, 2020. Courtesy: the artist and planyourvote.org

Ahead of a collaboration with artist Chella Man at Frieze New York, director Pati Hertling and newly appointed artistic director Taja Cheek explain how Performance Space is getting bigger by getting smaller

A RETURN TO INTIMACY

TARA AISHA WILLIS

When did each of you first come into contact with Performance Space New York?

PATI HERTLING

I grew up in Berlin and first moved to New York in the early 2000s to study law at Fordham University, during which time I stayed in Long Island City and on St Mark’s Place, near Performance Space 122 [PS122]. Then, when I returned from Berlin for a second time in 2007, I again lived around the corner from PS122 and, while I think I only went to a show there once or twice, I was always very aware of the space, its place in the East Village and its long history as a radical venue for performance.

TAJA CHEEK

I found my way into the art world by accident. In college, I was studying music and was very dissatisfied with it for many reasons, so I ended up finding my way to the art school. I went to a lot of talks and found out about spaces like The Kitchen, where I interned right after college. I worked in the archives because they were mounting their anniversary show and I learned so much about New York in the 1970s and ’80s the interconnected web of people, places and spaces. I probably first encountered PS122 at that time.

TAW Pati, you’ve been working at Performance Space since 2018, which has been an especially intense six years.

PH Yes, in January 2020 we handed over the keys to a group of artists. That was the start of our 02020 project, which, for us, was a new beginning. Embarking on this, at first, I was concerned that we needed a structure: we needed to ask questions and find solutions. But then, through the daily experience, I began to understand clearly that the power of it, and the potential for change, was in the process and not about getting answers at all. Everything that happened inside the building and our interactions with neighbors, artists and the community seemed to be a microcosm of what was going on outside in 2020.

It was a year-long project and it fundamentally changed how we approach everything we do at Performance Space in a way that was not premeditated or planned. The experience has now become part of our DNA.

TAW And how is it for you, Taja, coming in now?

TC It was encouraging to me that everyone could work collaboratively to build a structure based on mutual respect and sustainability thinking about everyone

on staff as human beings, as people who live multifaceted lives.

I’m curious about a lot of the past programs that are no longer happening. I hope to keep having conversations with people that were key to these earlier moments, like Sarah Michelson. I’m curious about Hothouse, for example, and histories of improvisation at the institution. Improvisation is something that I’m interested in and want to find a way back to.

TAW Both of you have such variety in your backgrounds: Taja as an artist and curator; Pati with your legal background and as a curator. How are these histories and practices helping you usher in this next phase?

TC I think there’s a fear of artists within institutions and, if you’re an artist, you’re expected to behave in a certain way. There’s a concern that if you’re a practicing artist you won’t put enough into your role that , somehow, everything you’re doing will be self-serving and you won’t be able to give yourself fully to an organization. But there are so many important figures in our field, historically and currently, who were or are artists, who went to art school or pursued other, related studies. These creative experiences brought them to their roles as curators

or directors. In general, there’s not enough of an acknowledgment of the messy entanglement of titles and roles that everyone inhabits.

PH In my “previous life” as a Holocaust art restitution attorney, I was able to get a very deep understanding of how and why cultural movements, especially during the 1920s and ’30s, became critical in times of political oppression. I have always been interested in the history of social spaces where artists and their communities gathered and conversed and how these spaces then acted as strongholds of cultural resistance.

Learning more about the history of Performance Space, particularly its role in the 1980s as a haven for free speech amid the culture wars and the AIDS epidemic, has deepened my conviction in the importance of these kinds of sites. I firmly believe that real-life experiences and the insights they provide especially regarding our communities’ immediate needs often have a more significant impact than traditional academic and art-historical approaches.

Institutions like ours should aim not just to follow an established path but also to engage with and reflect the changing needs and concerns of our communities.

MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK 20 FAIR PROGRAM

Chella Man’s film The Device That Turned Me into a Cyborg Was Born the Same Year I Was (2023) is on view at The Shed, New York, USA, during Frieze. Their performance Autonomy, co-presented with the Jewish Museum, will take place on May 2 at Performance Space New York.

And so, through our leadership structures and approaches, our leadership team, including myself, Taja and Ana Beatriz Sepúlveda, are working to be fully reflexive and deeply engaged with our growing communities. We’ve all developed our skills through hands-on organizing, curating, programming and administering, rather than relying solely on formal academic qualifications. I think there is a real commitment to adaptability and responsiveness, ensuring that our work remains relevant and impactful in the face of evolving societal challenges.

TAW You have multiple spaces and this building can operate in so many different ways. Are there things that you’re already thinking about in terms of the program’s structure?

TC I’m not there yet, but I think a season can tell a story or have a point of view. Whether it’s overt or not, a collection of programs, presented together, is meaningful and an audience will pick up on trends and themes across a season.

TAW Can you tell us about your collaboration with Frieze this year?

PH We have invited Chella Man to select the video program at Frieze and they are also going to do a performance, titled Autonomy, at Performance Space.

Chella showed work at Performance Space in 2022, as part of our “John Giorno Octopus Series” [in the group exhibition “Transcendence,” organized by Puppies Puppies aka Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo]. After this, Chella stayed in communication with us and often participated in our Sunday Open Movement workshops. Chella has actively expanded our community at Performance Space by bringing their communities of friends and collaborators with them. Working with them is a great example of how we want to exist and grow as an organization expanding through all of our deep contact points with artists and thinkers, making our space an inviting and accessible one so that people want to be here and feel safe to work and experiment. We are embracing this development on a presenting and production level, too. Many of our upcoming commissions are by artists who first came to Performance Space through our open programs and workshops and have been invited back to show more fully fledged commissioned works.

Through their connections to the disability community, Chella has also had a big impact on our conversations around accessibility at Performance Space. We are working with a lot of other artists, too, trying to make the institution more accessible

and thinking through certain aspects of readability and legibility for hearing and non-hearing audiences we were keen to bring that to the fair.

TC I think a good sign of a communitycentered organization is that artists are given the opportunity to grow and develop through it. That is a strength of Performance Space and something I want to build on.

TAW I’m noticing a commitment to building building on the knowledge gained from the last thing.

PH I like the idea of the curator, the singular voice, being pushed into the background to the advantage of the community.

TAW Looking beyond Performance Space to other venues in New York, or the field at large, are there tendencies or conversations happening right now that you are interested in?

TC I feel like there is a return to intimacy, which sounds very vague, and I mean it very vaguely. Intimacy in the sense of smaller performances or smaller convenings of people, convenings in homes; a return to sincerity, in a way. Maybe not just in New York, but especially in New York. I think that’s exciting and something to build off of.

PH One thing that has been talked about a lot recently is that few spaces are dedicated

to interdisciplinary and, especially, performance work. The field has become more institutionalized and, as institutions grow, they become expensive to run and can’t do experimental work anymore. In the wake of this, real vitality and energy are tangible in DIY artist-built spaces that have emerged around New York like PAGEANT, Grace Exhibition Space, Happyfun Hideaway and many others. These projects, in a way, begin as PS122 began: by filling a need that artist communities urgently feel.

I see Performance Space as now being more established than these venues, but still not a large institution we have an active and supportive function within the ecosystem. A core part of what we do is create a space for new work and new artists.

21 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK FAIR PROGRAM

Above Chella Man’s performance for “Transcendence,” 2022, organized by Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo) as part of the “John Giorno Octopus Series.” Photograph: Maria Baranova

Tara Aisha Willis is an independent curator, dance artist, writer and lecturer in theater and performance studies at the University of Chicago, USA.

Pati Hertling is director of Performance Space New York, USA.

Taja Cheek is artistic director of Performance Space New York, USA.

Fifty years ago, the anti-war Bread and Puppet Theater left the Lower East Side for a farm in Vermont. Today, the company’s participatory morality plays feel as necessary as ever, finds Hussein A.H. Omar

PAPER GODS

I saw Bread and Puppet Theater’s most recent show in San Antonio, Texas. This city was the former home of US Air Force serviceman Aaron Bushnell, whose fatal self-immolation on February 25 this year, just a few days prior to the performance, recalled the horrifying spectacle of Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc’s protest in 1963 against the persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government. Bookending Bread and Puppet Theater’s work thus far, these two acts were desperate demands for conscience: one echoed by the company over the course of six decades.

Some 60 years after it was founded in a loft in the Lower East Side by Peter and Elka Schumann in 1963, and 50 years since it left New York for a farm in Glover, Vermont, Bread and Puppet Theater continues to respond to urgent crises with unapologetically political performances, staged in any place that’s not a “proper” theater. With its ritual distribution of bread and aioli to audiences, its repurposed bedsheets and its painted cardboard, papier-mâché heads and woodblock-printed banners, the group has a homespun aesthetic redolent of the 1960s anti-war movement from which it emerged. Before October 7, 2023 those aesthetics might have felt nostalgic, even reactionary. And yet, as the world sees mass demonstrations on a scale that nears that of the Anti-Vietnam War protests, the idioms, tactics and languages of those times feel closer to us than ever.

With remarkable consistency, the work of the company has persistently framed the American empire as a death cult.

Described by Schumann as “a wild feast against death,” his first show in the US in 1962 was called Totentanz (literally, “death dance”) and his latest, The Palestine Emergency Mass (2024), conducts a funeral

service for the ongoing catastrophe we are forced to witness but are powerless to stop. He demands during the course of the performance that we reflect on whether it is worth saving “a civilization that has routinely large numbers of dead as part of its merchandise.” Bread and Puppet’s shows more often than not have little plot: largely allegorical, their eponymous “puppets” which are sometimes masks, sometimes idols stand for archetypes rather than characters. They are a cross between medieval morality plays like Everyman and Mankind and avant-garde performance art, infused with the rituals of High Church Catholicism and a playful entirely concocted “pagan” cosmology.

When asked in an interview published in TDR: The Drama Review in 1968 why he turned to puppets to intervene in politics, Schumann insisted that it was for the sense of “alienation” which “is automatic with puppets.” The performers operating the company’s puppets typically dressed in white fade into collectivity, allowing principles to float above personalities. Where egos fall apart, ideas come into sight. One might say that the performers, who are often masked and sometimes concealed, make it possible to unmask the ideologies that shape our political horizons but which we seldom recognize as fictions. The apparent naivety of Bread and Puppet’s aesthetic aims to uncover the illusions that conceal our most deeply held convictions. To take one example from The Palestine Emergency Mass, the company perform “a traditional American war dance.” It is nothing but histrionic screaming, the entitled temper tantrum of those whose unquestioned sense of moral and material superiority has been questioned. Here, the condescending, hubristic ethnographic gaze,

through which the “West” constantly imagines the “rest” that it seeks to either remake in its own image or eradicate, is turned back on itself. In this regard, the company’s puppets “profane the holy,” to paraphrase a segment from The Communist Manifesto (1848) that’s chanted in this recent show: the mélange of pagan and Catholic ritual unveils the irrational contingencies that underwrite both, equally.

The show depicts a conflict between two groups of protagonists: “the Terrorists” and “the Horrorists;” the former are depicted as merely the enemies that have decided to get in the way of the latter’s unencumbered “total military superiority.” The difference is cosmetic: the former are small, the latter wear suits. Just as shredded newspapers and flour can make a hollow god, a suit can transform a man. Power makes truth and might makes right.

In a surprising twist, the show’s titular funeral mass isn’t held for the thousands dead since October 7 but instead is a funeral for moribund thinking, “a funeral to bury the rotten idea of the day” revealed, mid-ceremony, to be the limited notions of “freedom” and “democracy” that politicians disingenuously tout. It is for ourselves what the production, evoking cultural theorist Klaus Theweleit’s “not-yet-born,” calls the “not-yet-dead” that we are grieving. In the final scene of The Palestine Emergency Mass, the performers start to repeatedly scream. By the third scream, the captive audience, unprompted, began to desperately, cathartically, even hysterically, join them.

“Indulgent, sentimental, defeatist,” so wrote art critic and AIDS activist Douglas Crimp of public mourning rituals during the AIDS crisis in his 1989 essay “Mourning and Militancy,” reflecting

the suspicion in which some activists have held them. To skeptics, these performances may seem at best like distractions and, at worst, like a kind of numbing agent, satisfying impotent people’s desires to feel like they are doing something, while in fact postponing the kind of risky militant actions that could more effectively force the hand of the powerful. In that way, the company’s name, Bread and Puppet, seems deliberately to invoke not just the revolutionary demand for “bread and roses” but the Roman panem et circenses, or “bread and circuses”, which the poet Juvenal said was all that was needed to appease the masses.

Before seeing Bread and Puppet Theater’s work in person, I was wholly convinced that the point of political theater was to “turn grief into anger,” that mourning was only worth indulging in if it could be transformed into activism. But, on watching the performance, I realized that this persistent demand that political theater convert grief into “something useful” misses a fundamental point. We need to mourn, collectively, the lost objects that we believed made us who we are, as a prerequisite for selftransformation. Derailed by a density of death that’s hard to digest, there is an unacknowledged power in our capacity to scream back together.

22 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK THEATER

Hussein A.H. Omar is writing a 500-year history of Egypt as told through the stories of his family and their cemeteries. He also organizes with Writers Against the War on Gaza.

Opposite Bread and Puppet Theater in Montpelier, VT, 2006. Photograph: Randy Duchaine/Alamy

True Maestro

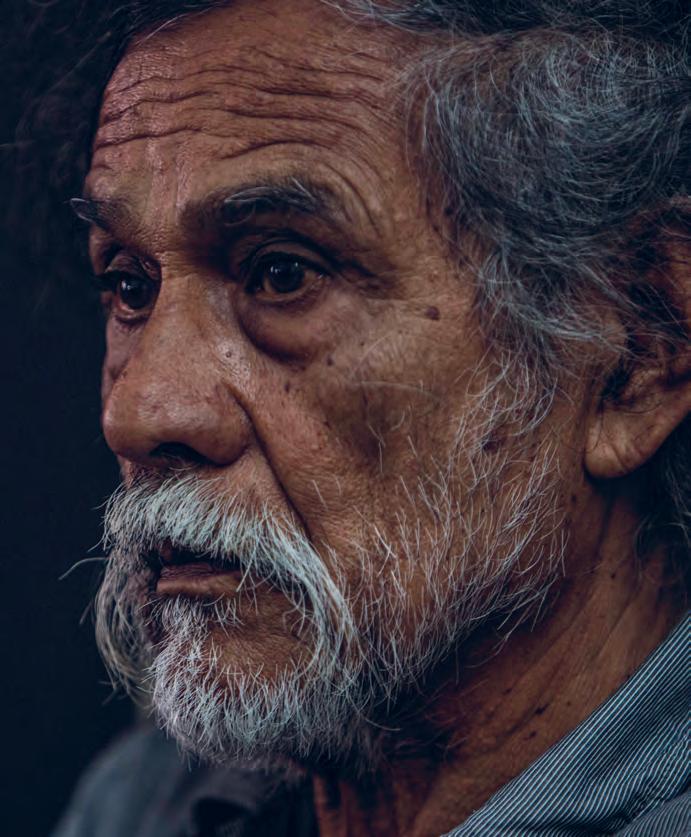

One of Francisco “El Maestro” Toledo’s last projects is revealed: a special tequila bottle adorned with wildlife

In 2015, a minor controversy erupted at the Oaxaca International Book Fair when an artist named Markoa publicly denounced the Mexican master Francisco Toledo, calling him a “cacique of art and of Oaxacan culture.” The accusation, correlating Toledo’s wealth and local influence with the cacicazgos of colonial Mexico, in which indigenous elites, bosses and strongmen upheld the social order through autocratic rule, was met with loud disapproval. Amid angry whistles and jeering, the journalist Elena Poniatowska offered this sharp rejoinder: “If only

the whole country would be filled with caciques like Francisco Toledo.”

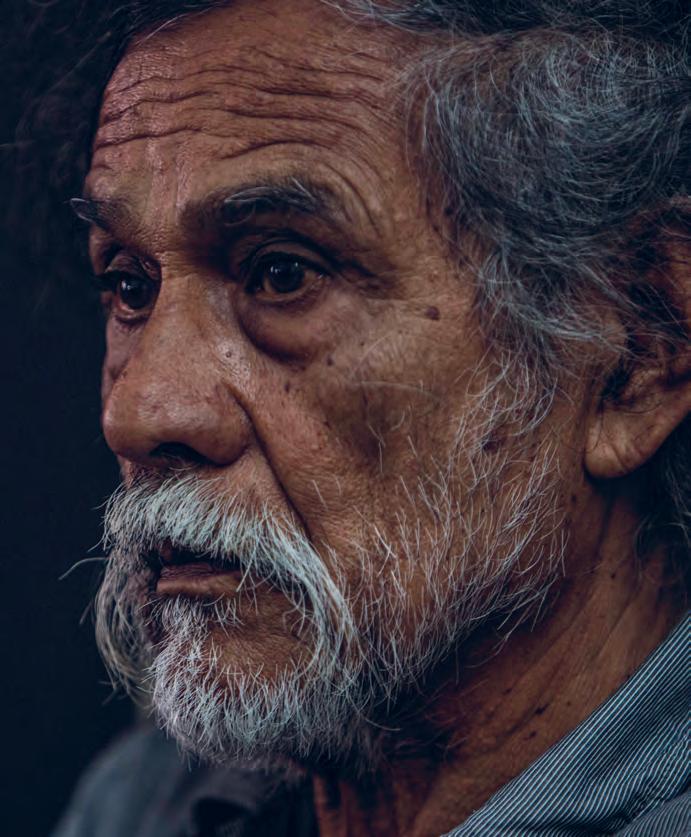

Toledo, who died in 2019 at the age of 79, was a titan of Mexican art and culture, his technical virtuosity and febrile imagination earning him the nickname “El Maestro.” Over a career spanning nearly 70 years, he traversed formats and media, becoming accomplished in sculpture, photography, painting, ceramics, illustration and lithography.

One of Toledo’s final projects engaged this multiplicity of media. Commissioned by Maestro Dobel Tequila, in 2019 Toledo

painted a prism composed of four cubes. This form has been translated into the bespoke casing for “Dobel Grandes Maestros ‘Toledo Edition,’” decorated with a lagarto or lizard with a curled tongue. The bottle itself features a hand-carved, volcanicstone base and stone topper, sourced from Teotihuacan, and a hand-engraved and frosted bottle featuring the same playful lagarto.

This lizard motif is typical of Toledo’s fantastic realism, buoyed by a deep appreciation for unconventionally beautiful beasts such as bats, tapirs, crickets, rabbits, monkeys. A natural fabulist, his work often depicts transformations, altered states and the complex webs of life tying together all living creatures, revealing his deep familiarity with traditional Zapotecan narratives. In a nod to this heritage, the Maestro Dobel Tequila collaboration was created as an edition of 281 with 16 bottles available for purchase in the US each one representing one of the 281 indigenous languages spoken in Mexico, including Zapotec languages.

The first bottle available in the US will be auctioned on Artnet and can be previewed at the Maestro Dobel Tequila Artpothecary exhibit at Frieze New York, which is itself designed to channel the airy elegance of Toledo’s home state, replete with displays of Oaxacan craftmanship. Though he lived in an austere, mostly furnitureless house with his family, the softspoken Toledo was a familiar sight on the streets of the Oaxacan capital: lean and wild-haired, wearing loose cotton clothes and workaday huaraches. He worked daily to fund the public projects in Oaxaca that today may be his crowning achievements: the Museum of Contemporary Art of Oaxaca; the Graphic Arts Institute of Oaxaca; a library for the blind; a small factory devoted to handmade paper; a center for photography; an arthouse cinema; and a botanical garden.

Born in Mexico City in 1940, Toledo claimed as his hometown the coastal city of Juchitán, near the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in the flat, hot, eastern end of Oaxaca state. Spurred by political turbulence in the

Isthmus region, Toledo’s family migrated to Minatitlán in the Gulf of Veracruz when he was a young boy, where he felt he was living in a state of permanent exile. Encouraged to study law by his shopkeeper father, Toledo eventually moved to Mexico City in his late teens to train at the Taller de Grabado, where he met the Oaxacan painter Rufino Tamayo. Success came early for Toledo, who mounted shows in Mexico City and the US before the age of 20. From 1960 to 1965 he lived in Paris, painting and printing at the famed Atelier 17. In the French capital, Toledo visited Octavio Paz and reconnected with Tamayo, who was instrumental in helping to sell his work.

Toledo resettled permanently in Mexico in the 1980s, living and working in Oaxaca’s capital. In 2014, after 43 students disappeared in Guerrero, in the southwest of the country, he staged the exhibition “Duelo” (Mourning), at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. He spent a year creating ceramics challenging sculptures showing bloodied and flayed expressions of frozen anguish.

In a wide-ranging interview with writer Karen Moe in 2017, Toledo admitted to a constitutional pessimism, a clear sense that “man’s barbarism and destruction of the environment and of each other is never going to change.” Yet he always felt compelled to keep working, doing so, he said, out of pure “necedad, solo necedad.” In other words, out of pure foolishness.

24 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

Visit the

exhibit on Floor 6 of The Shed during

New

Patricia Escárcega is a journalist. She lives in Los Angeles, USA.

Maestro Dobel Artpothecary

Frieze

York.

FRIEZE PARTNER: MAESTRO DOBEL TEQUILA

Below Francisco Toledo, 2015. Photograph: Miguel Tovar/LatinContent via Getty Images

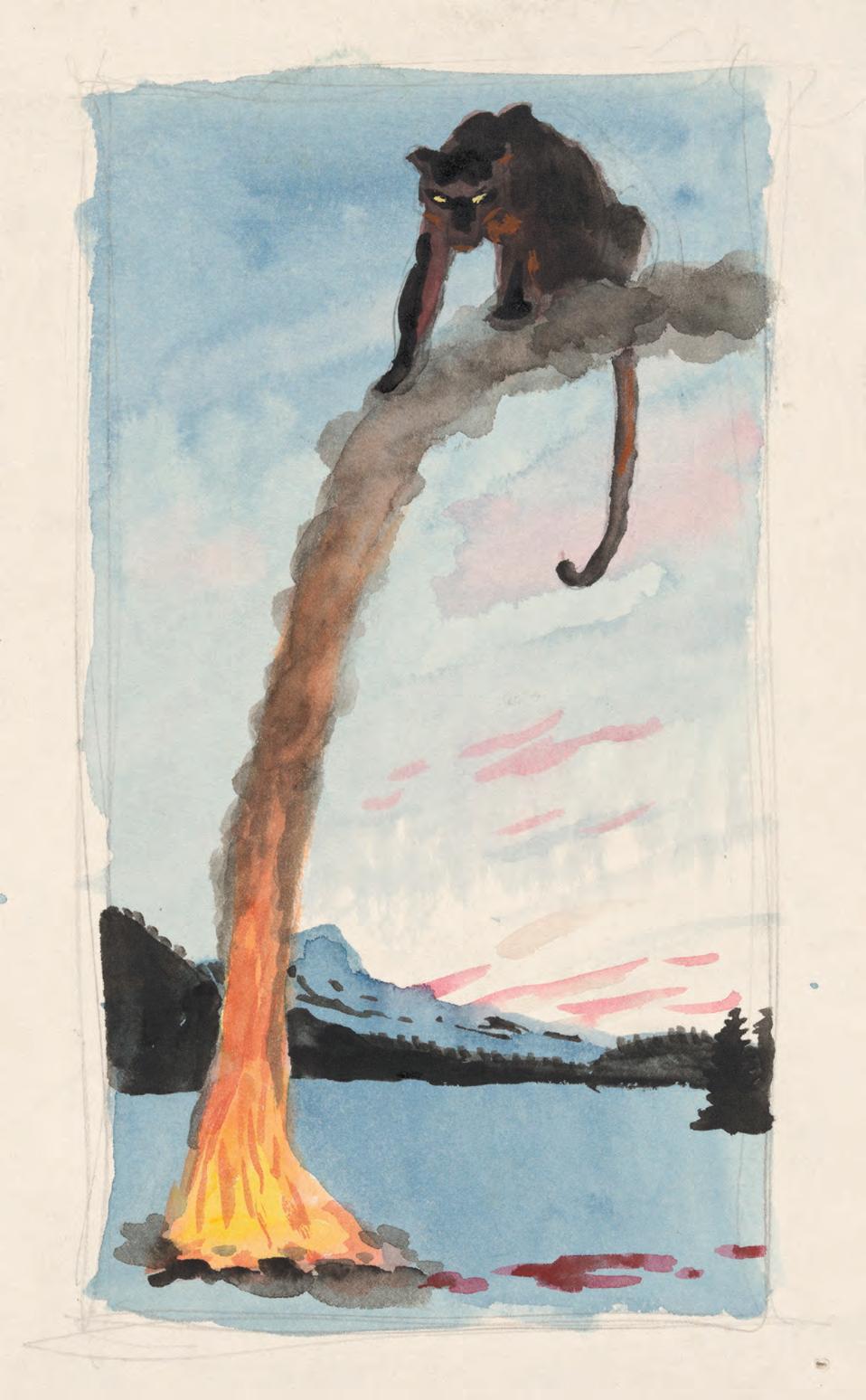

WALTON FORD BIRDS AND BEASTS OF THE STUDIO

THROUGH OCTOBER 20, 2024

Madison Ave. at 36th St.

themorgan.org

#MorganLibrary

Walton Ford: Birds and Beasts of the Studio is supported by the Alex Gordon Fund for Exhibitions, Thomas J. Reid and Christina M. Pae, Gagosian, and Bettina Bryant. The exhibition is a program of the Morgan Drawing Institute.

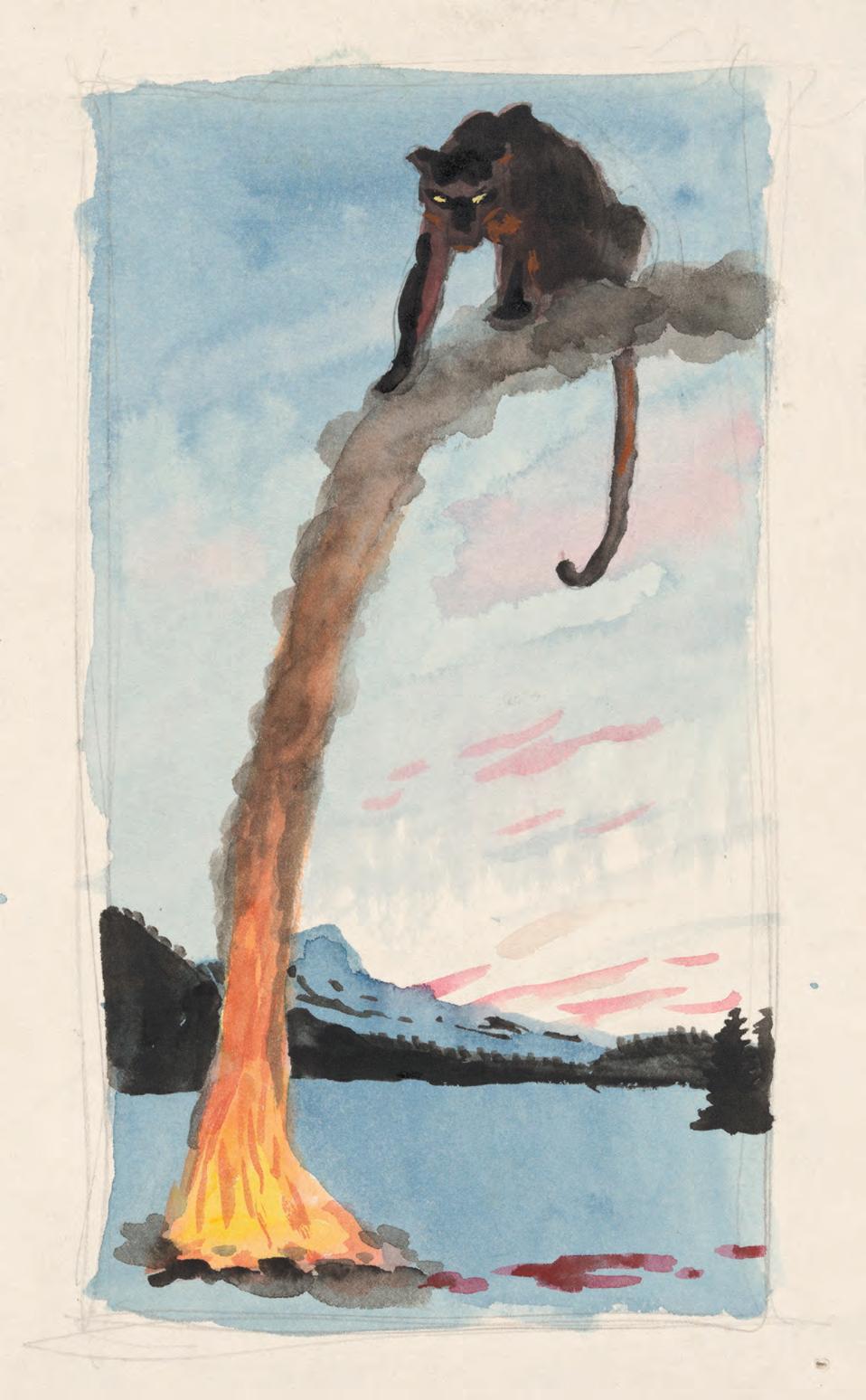

Walton Ford (b. 1960), Study for “Verfolgen,” 2018. Watercolor, gouache, and ink over graphite. The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the artist, 2019.213. ©️ 2024 Walton Ford. Photography by Janny Chiu.

Walton Ford: Birds and Beasts of the Studio is supported by the Alex Gordon Fund for Exhibitions, Thomas J. Reid and Christina M. Pae, Gagosian, and Bettina Bryant. The exhibition is a program of the Morgan Drawing Institute.

Walton Ford (b. 1960), Study for “Verfolgen,” 2018. Watercolor, gouache, and ink over graphite. The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the artist, 2019.213. ©️ 2024 Walton Ford. Photography by Janny Chiu.

Collectors Lisa Young and Steven Abraham, co-founders of The Here and There Collective, talk about their support of early and mid-career artists of the Asian diaspora to Frieze New York’s new Focus curator, Lumi Tan

LUMI TAN

One thing I find really special about your approach to collecting is that it’s based around relationship-building and not just with artists. You consistently give credit to curators and other professionals who have influenced you. How do you go about building these relationships?

LISA YOUNG

I think it’s very organic, as with any relationship. Being in New York really helps because you can go to shows and see the same people and start talking to them.

I think we are very intentional, and this was especially so when we started out, because we don’t come from art-world backgrounds or families. We’re the first in our families to collect or take a serious interest in art. Coming into the art world as outsiders, we began collecting in 2017 and set a goal of just showing up going to a lot of openings and seeing who

FIGURING IT OUT TOGETHER

organized the shows, which gallery represented the artists we were interested in, who were the artists that we liked to see. We took an approach of genuine curiosity and appreciation.

STEVEN ABRAHAM

When we decided to collect contemporary art, we quickly came to appreciate the proximity we have to the creators, to the makers themselves. You’re able to tap into their community and it’s a real privilege.

When we started collecting artists from the Asian diaspora that became amplified, because we could relate to their stories and connect with them on a deeper level.

LT It is so rare for artists, and particularly artists of color, to have a connection or way of relating to the people who buy their work. As a second generation Asian American, it’s been meaningful to follow your work through The Here and There Collective [THAT Co.]: the online

project you created in 2021 to provide Asian-diasporic artists with a platform and way to connect. Did this project grow out of the priorities you were establishing within your collection?

LY Yes, there are definitely parallels between the two. The platform came out of our personal collecting journeys and our focus on the Asian diaspora, out of conversations we were having and a desire to connect. We often cite ARTNOIR as a key mentor. We wanted to find that for ourselves and to educate ourselves because we knew we wanted to grow our collection, and that this was our focus. So, we were wondering who was out there. But we also wanted to share our discoveries with other people and encourage them to look at the artists we had encountered. Having done a lot of studio visits, we realized we could help artists connect to other artists, gallerists or curators and create a community.

THAT Co. started during the Covid-19 pandemic and, initially, was done virtually. It’s been nice to focus more on face-to-face community-building since then. We started a residency program, for example, and have created more physical spaces.

SA THAT Co. grew as we grew as collectors. Claire Kim has come on board as our director of curatorial affairs. I feel a certain kinship with curators because I think collectors and curators are on a similar journey of discovering artists. Of course, curators also have the academic background, which allows them to contextualize the artists’ practices.

LY Our philosophy on collecting is that it’s less of a one-sided transaction. We think about it more in terms of stewardship and as bi-directional, especially because our collection is of primarily emerging to early- and mid-career artists. I almost see a peership with many of the artists that we have collected because, in a way, we’re all

MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK 26 COLLECTING

Photography Ryan Lowry

Opposite Lisa Young and Steven Abraham at their home in New York, February 2024

wall:

Matrilineality, 2019

On

Dominique Fung,

MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK 27

trying to figure out the art world. A lot of our conversations are about how to work it out together. It speaks to the strength of an ecosystem.

SA With our residency, we ask the artists what they are hoping to achieve and we tailor our support accordingly.

LT To zoom way out, I wanted to ask about the term “Asian American” and the current discussion around how it can’t really mean anything because the Asian diaspora is so huge and allencompassing. How does that apply to your perspective on collecting? Do you set boundaries on who or what you’re looking at or where you’re traveling to?

I know that female representation is very important to you. Does New York, as your home base, play a significant role as well?

SA I don’t think we’ve actually had an intentional conversation about this,

but I’ve never felt that we have to collect from different regions. Usually, it’s a little bit more natural, a little bit more organic. For instance, I’m originally from Indonesia, so I’m always interested in Southeast Asian artists. During the pandemic, there was a resurgence of the Indonesian art scene, with conversations happening online about the different types of artists and artist communities there. For me, it was a natural progression to learn more about the scene, and its collectors and institutions, in Indonesia and the surrounding region. Our friends span many different diasporas: the Chinese or East Asian diasporas, but also the South Asian diaspora. Whenever there is talk of Asian art, the focus tends to lean towards the East Asian perspective so, there is a conversation to be had around the visibility of the broader Asian diaspora, too.

LY We aren’t looking at a map and saying: “Only from here.” Our collection is rooted in the work and how we connect to it, and that naturally lends itself to our personal stories as well. For instance, Steven was brought up in Asia and his first language was that of his ethnic heritage, whereas I was born and raised in New York and my primary language has always been English.

I think that how we respond to the artworks in our collection is also a reflection of our own experiences of what it means to be Asian or Asian American. For Steven, it’s very different than it is for me. We read each work differently because of how, as people, we identify within those communities. I don’t think there’s necessarily a rubric for our collection, but each work must be something that we resonate with and which provides us with more questions than answers.

LT That’s what I always say about the artists that I want to work with! If, after a studio visit, I leave with more questions than answers, then I know I want to pursue a commission or something that’s very open-ended with them. I want to begin that process together and not know what the outcome will be. Do you feel like that with regards to the future of your own collection and THAT Co.? Will they respond to how these artists progress in their careers and how their needs develop, and the relationships that you will continue to build with them?

SA In the beginning with THAT Co., we tried to make things as inclusive as possible. We didn’t just want to build an audience we wanted to build a community. And with our residency, we always start by asking our artists what their career goals are and build our program from there.

28 COLLECTING MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

Above, left Clockwise from left: Dew Kim, Till I Know What Love Is 02, 2023 (on wall); Arghavan Khosravi, A Family Portrait (Childhood Memories), 2019 (on wall); Heidi Lau, Chrysanthemum Vessel 2020 (partially visible on floor)

Above, right On wall, left to right: Timothy Lai, Everything I Say Is Wrong, You Don’t Understand, 2021; Anna Ting Möller, shrimp pile 2023; Xin Liu, Teratoma, 2019 On floor: Liao Wen, Hesitation 犹疑, 2020

29 MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

On bookshelf: Kathy Huang, Portrait of Lisa, 2023

On wall, clockwise from top left: Oscar Yi Hou, Entitled (Chinaman 2), 2020; Yesiyu Zhao, Facial 2021; Alvin Ong, Mood #17, 2020; Candice Lin, Papaver Somniferum (Death Centaur) 2020; Tidawhitney Lek, Father 2022; Maia Cruz Palileo, Afterward 2019; Eko Nugroho, The Witness Radio Project, 2010; Anna Park, Steven + Lisa 2022; Maia Cruz Palileo, Kumander 2020

LY I think it’s less about who we specifically want represented in our collection in the next five to ten years and more about expanding the question of what it means to be a collector. Are there other forms of patronage? Maybe not something new, but something more like old-school patronage: supporting an artist in their career and not just acquiring the work on a one-off basis. That is also at the root of THAT Co. It’s wonderful that we have been able to collect many works that we love to live with, but what else can we do? That’s more conceptually how I think about pushing our collection and us as collectors.

But, more practically, I am also wondering how we can challenge ourselves as appreciators of art and with regards to what we live with. Personally, I would love for us to collect more video art or to go towards work that is perhaps more challenging in terms of content.

SA Last year, THAT Co. presented a series of performances at Spring Hill Arts Gathering in Washington, Connecticut. It was such a meaningful experience. There were beautiful performances by many artists that I knew of, though I hadn’t seen that area of their practice, so it was full of wonderful surprises. This is something we want to keep on building. I’m also interested in having more conversations about collecting and supporting artists.

Last year, we collaborated with ARTNOIR for a panel talk about representation, which took place in Los Angeles during Frieze Week. It was a fruitful, engaging conversation that considered how we can evolve into being allies or advocates for marginalized groups. That led to the recent Voices of the Diaspora conversation at the city’s Hammer Museum, which we coorganized with the Asian American Pacific Islander Arts Network and ARTNOIR,

bringing together artists and thought leaders from different diasporas, including Charles Gaines, Harry Gamboa Jr., Kris Kuramitsu and Tala Madani, among others. I’m curious about how we can evolve the conversation about Asian American artists’ representation and identity, so that we’re not talking about the same things in another five or ten years.

LY I’m interested in the ecosystem as a whole and the expansion of what it means to be a collector within that. What are the other roles in this ecosystem and how can we all consider the future together?

SA At the essence of it, with THAT Co. we’re trying to create a very accessible archive for artists in our diaspora. Secondly, we are looking at how we can support younger artists to really propel their early careers and help create their first documentation. At the end of the day, we want to try to connect others and it is so rewarding

to hear of people using our archive to curate shows or give talks, or about relationships that have been formed as a result of the platform. Community is so important to provide a sounding board, to have real give and take and to keep on evolving.

30 COLLECTING MAY 1–5, 2 0 24 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

Lumi Tan is a curator and writer. She is currently the curatorial director of Luna Luna and advisor for Focus at Frieze New York, USA. She lives in New York.

Lisa Young and Steven Abraham are collectors and co-founders of The Here and There Collective. They live in New York, USA.

Above, left On wall, left to right: Pauline Shaw, cut the sky 2022; Umber Majeed, We Buy Asians, 2015

Above, right Catalina Ouyang, font V, 2020

ANDREA BOWERS

HENRIQUE OLIVEIRA

MARCUS COATES

PASCALE MARTHINE TAYOU

THIJS BIERSTEKER

TOMOKO SAUVAGE

TALK WITH NATURE ON RUINART.COM

FRIEZE NEW YORK PLEASE DRINK RESPONSIBLY

RUINART ART LOUNGE

©2024 BMW of North America, LLC. The BMW trademarks are registered trademarks. THE ALL - ELECTRIC BMW i7. BMWUSA.com

A round-up of significant shows at New York institutions during Frieze Week, from the Whitney Biennial to the Met’s look at the Harlem Renaissance and surveys of Pacita Abad, Es Devlin, Terry Fox and Joan Jonas

HOT TICKETS

Whitney Biennial: “Even Better Than the Real Thing”

Whitney Museum, until August 11

The 2024 Whitney Biennial grapples with how artificial intelligence is shifting our grip on reality as gender rhetoric continues to delimit autonomy. Featuring 71 artists and collectives, and co-curated by Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli, highlights include Isaac Julien’s multi-screen Once Again … (Statues Never Die) (2022), Mary Lovelace O’Neal’s latest body of paintings, “Doctor Alcocer’s Corsets for Horses” (2023), and Ligia Lewis’s A Plot, A Scandal (2023). There are also extensive performance and film programs.

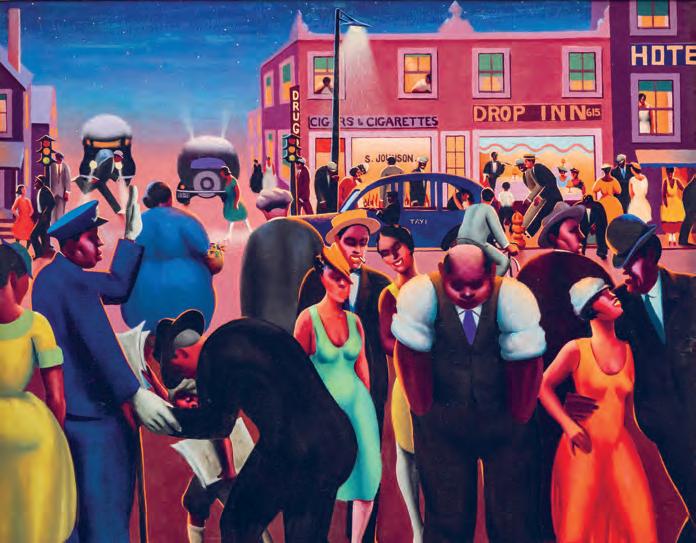

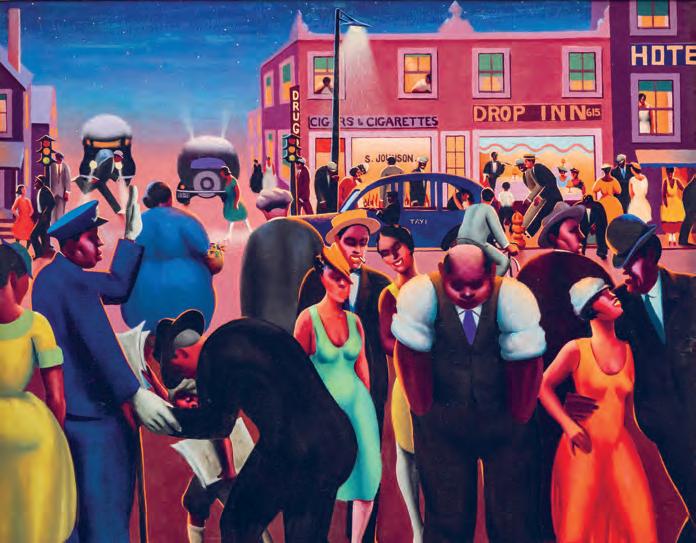

“The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism”

Metropolitan Museum of Art, until July 28

A landmark show, this is the first artmuseum survey of the Harlem Renaissance in New York since 1987, establishing its development of the Black subject as central to international modern art. It explores how Black artists portrayed everyday life in the early decades of the Great Migration, when millions of African Americans moved away from the segregated South to the North, Midwest and West, including New York’s Harlem. Among 160 works, it features Charles Alston, Aaron Douglas, Meta Warrick Fuller, William H. Johnson, Archibald Motley, Winold Reiss, Augusta Savage, James Van Der Zee and Laura Wheeler Waring, alongside pieces portraying the international African diaspora by Germaine Casse, Jacob Epstein, Henri Matisse, Ronald Moody, Edvard Munch and Pablo Picasso.

“Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys”

Brooklyn Museum, until July 7

The first major exhibition of the collection of the Deans aka music power couple Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys “Giants” is just a selection of their world-class holdings. The show spotlights work by Black diasporic artists, including Derrick Adams, Arthur Jafa, Meleko Mokgosi, Odili Donald Odita, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Gordon Parks, Deborah Roberts, Tschabalala Self, Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley. It also explores the relationships between the Deans and the artists they support, encouraging “giant conversations” inspired by the works on show.

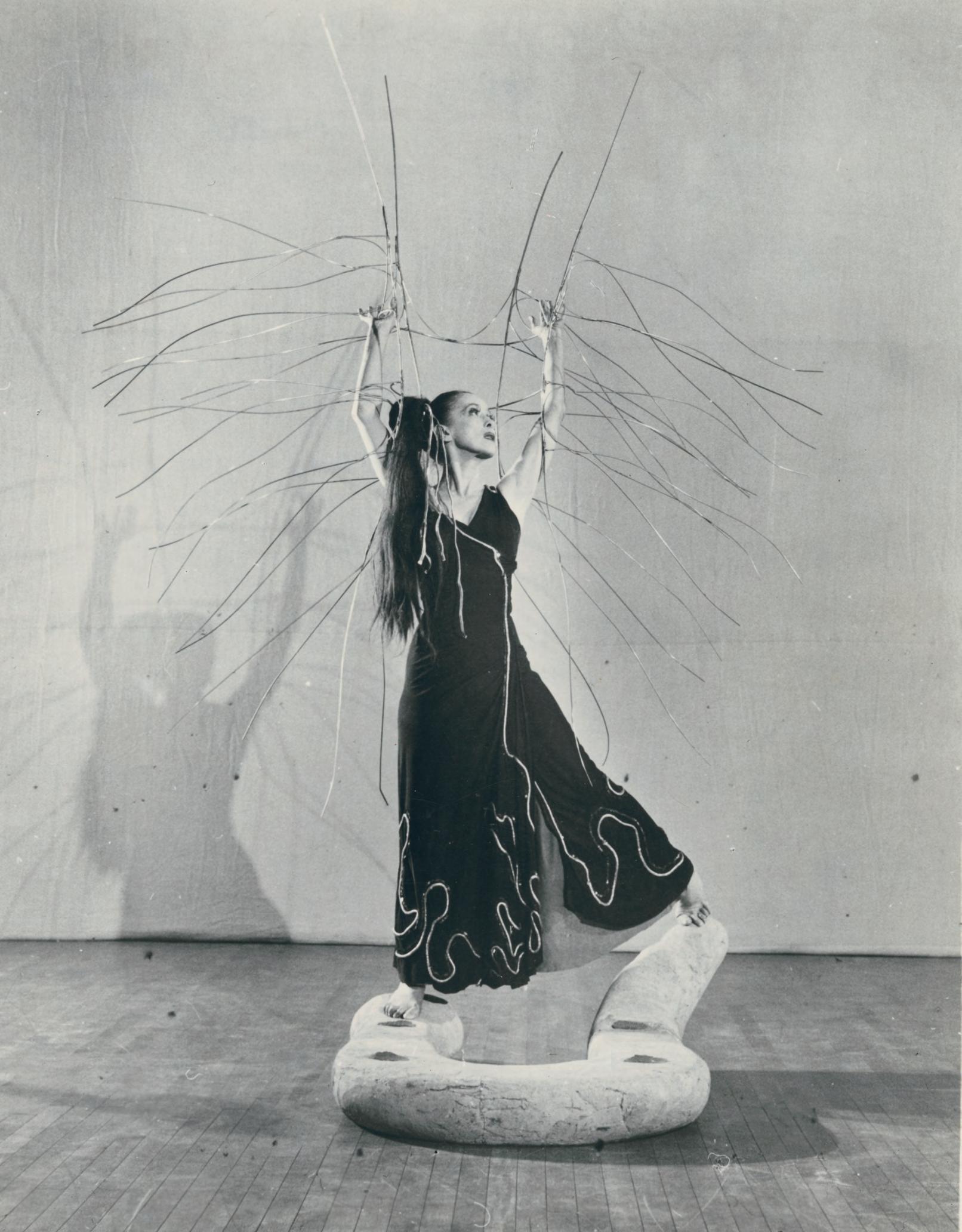

“Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning” Museum of Modern Art, until July 6

This MoMA show is the most comprehensive retrospective of Joan Jonas’s work to date, covering more than five decades of performance, video, drawing, sculpture and installation. Jonas began her career in New York’s 1960s downtown art scene, where she was a pioneer in her use of performance and video, drawing from diverse sources including Noh and Kabuki theater, literature and art history. “Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning” includes drawings, photographs, notebooks, oral histories, film screenings, performances and installations.

“Peter Hujar: Rialto”

Ukrainian Museum, May 2–September 1

Born in the US to an immigrant family, Peter Hujar spoke only Ukrainian for the first five years of his life. That outsider

position and his abusive childhood were reflected again and again in his photography. Hujar’s technical mastery was paired with an endlessly questing exploration of an unseen New York of gay cruising, flamboyant performance, danger and vulnerability. This exhibition features 74 of Hujar’s earliest photographs from 1955 to 1969, including three series: “Southbury” (1957), focusing on the Southbury Training School for mentally challenged students; “Florence” (1958), which features neurologically impaired children; and “Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo” (1963), of centuries-old, exposed corpses. A fascinating overture to the work of one of New York’s seminal photographers.

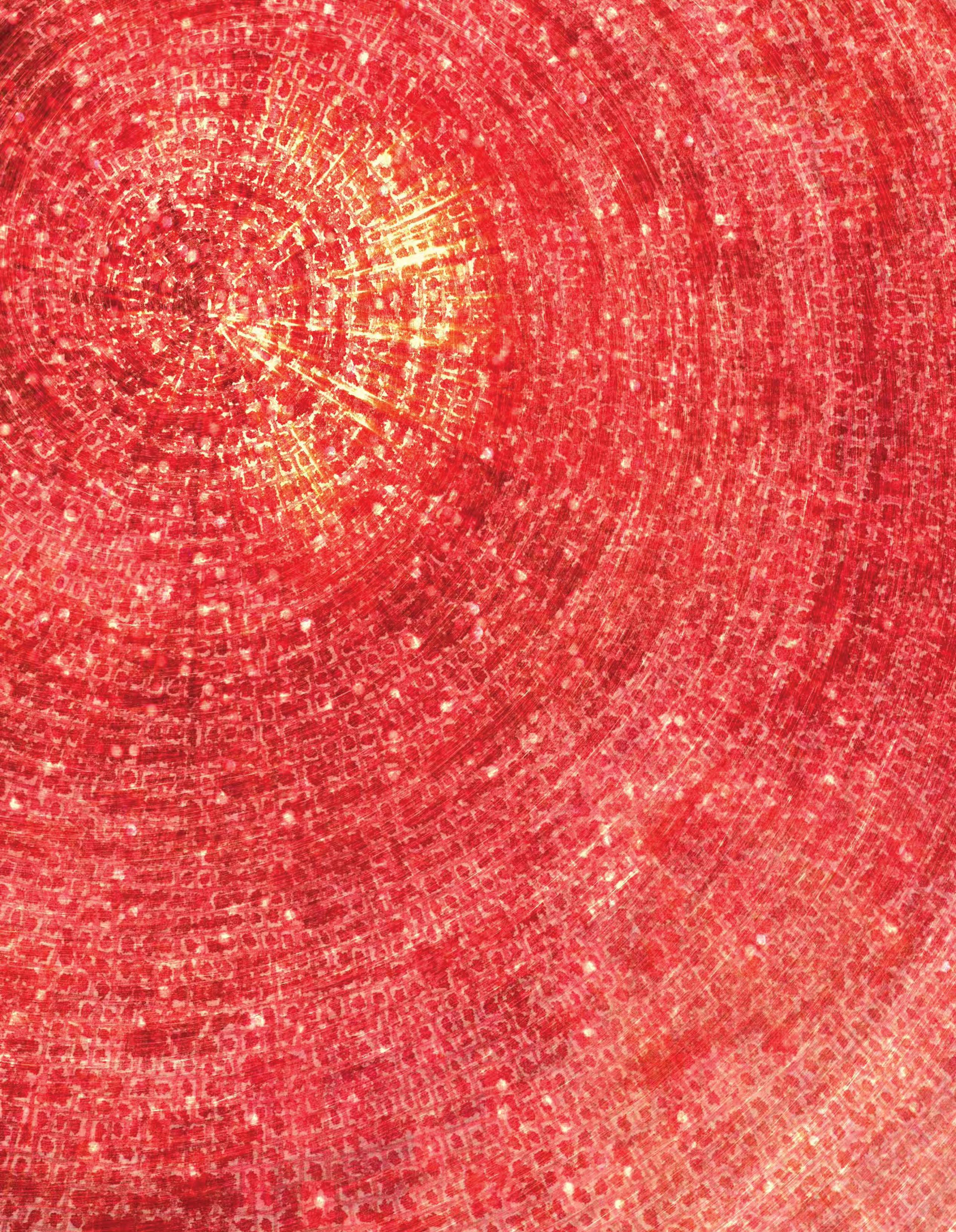

“Melissa Cody: Webbed Skies”/ Pacita Abad

MoMA PS1, until September 2 Pacita Abad is known for stuffing and stitching her canvas to make quilted paintings. Her first retrospective, at MoMA PS1, delves into her 32-year career, revealing her socio-political drive across textile, costume, ceramics and works on paper. Also at MoMA PS1, Melissa Cody’s first solo museum show, “Webbed Skies,” features major new work. Cody blends traditional techniques with digital technology, continuing the reinvention that spurred the Navajo weaving movement: during the forced expulsion from their lands in the mid-19th century, Navajo people were given blankets by the government, which they unraveled to use in their own textile works.

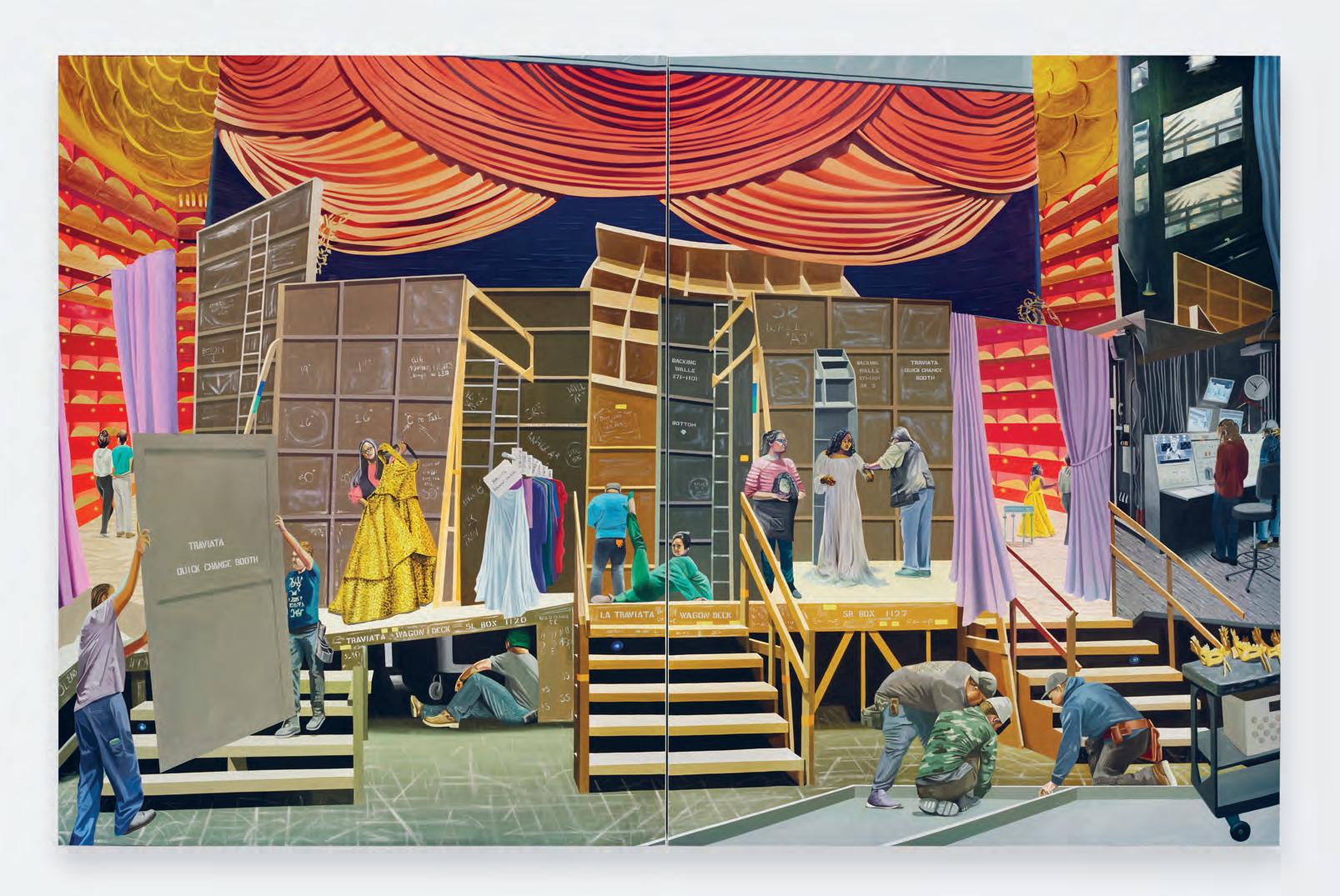

“An Atlas of Es Devlin” Cooper-Hewitt, until August 11

This is the first monographic museum exhibition of British artist and stage designer Es Devlin. Devlin began in small theaters in the 1990s and has since produced work for the National Theatre, the Metropolitan Opera, World Expo, the Lincoln Center, the United Nations, the Olympics, the NFL, The Weeknd and U2, among others. This exhibition digs through her 30-year archive, unearthing unseen sketches, paintings and cardboard models the seeds of her oftenmonumental projects.

Beatriz Cortez & Candice Lin Performance Space, until June 9

Beatriz Cortez and Candice Lin’s dual exhibition at Performance Space explores experiences of diaspora and migration through sculpture. Cortez creates portals that connect across time and space. Visitors can interact with her work, which evokes a yearning for a distant land. Lin’s multi-part installation addresses

Asian indentured laborers, the circulation of goods they produce, and the relationships between race and linguistics.

Harmony Holiday: “Black Backstage” The Kitchen, until May 25 Installed immersively, “Black Backstage” transforms The Kitchen into a place that suggests the aesthetic of makeshift storefront churches, revival meetings, faith healings and other underground, “backstage” spaces of Black displacement, ritual, creation and performance. The exhibition comprises film, writing, a sound installation, live performance and public conversations.

“Terry Fox: All These Different Things Are Sculpture”/“Dream Lines: Marian Zazeela” Artists Space, until May 11

“Terry Fox: All These Different Things Are Sculpture” is the late conceptual artist’s first institutional show in New York since 1980, and comprises video, sound works and performance documentation. Fox created extreme physical and psychological performances that used his own body alongside an arsenal of materials that included everything from flour and dead fish to the sound of purring cats. Among his works was Yield (1973), a set of ritualized, trancelike actions that took place over three days with Fox creating skeletal outlines on the floor, blowing smoke and baking bread.