O N T E N T S

G O E T H E D A K A R

L I F E A Q U A P O N I C

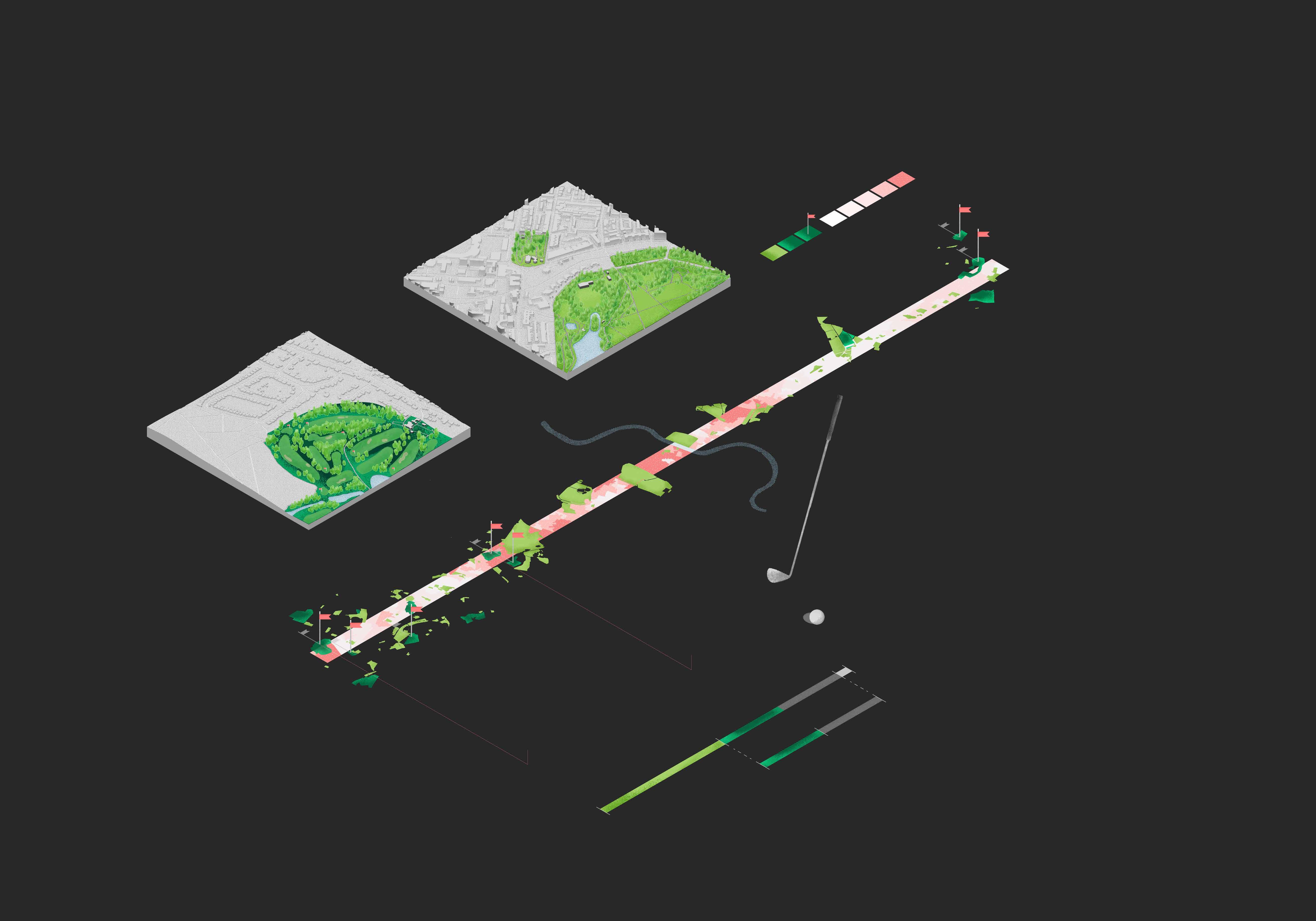

R I B B O N H O U S E

E X T R A A P P E N D A G E S

B U M P E R S C H O O L

F H H B I O L A B

E M P I R E R E D U X

(PARTNER: ALICE COCHRANE)

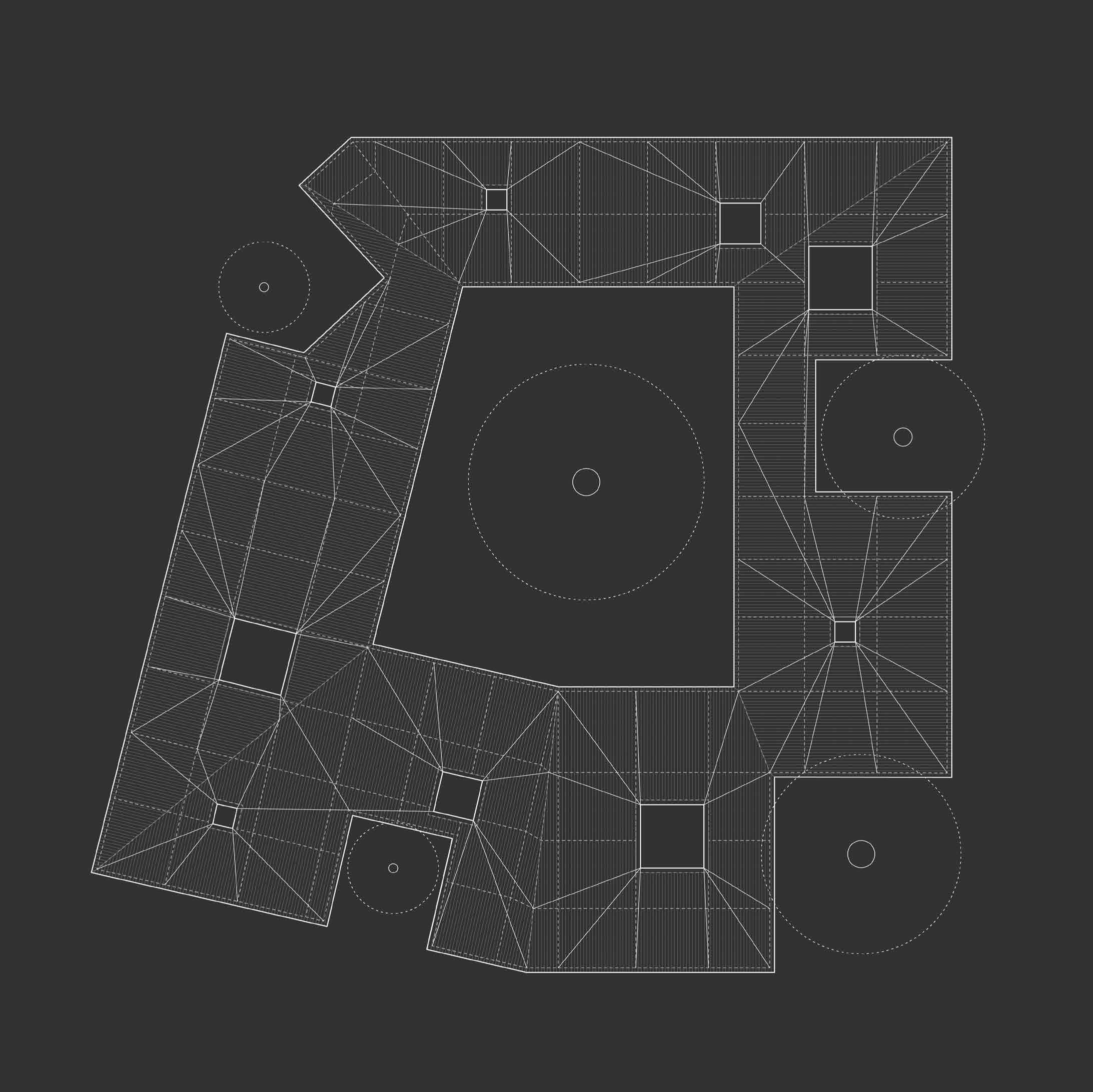

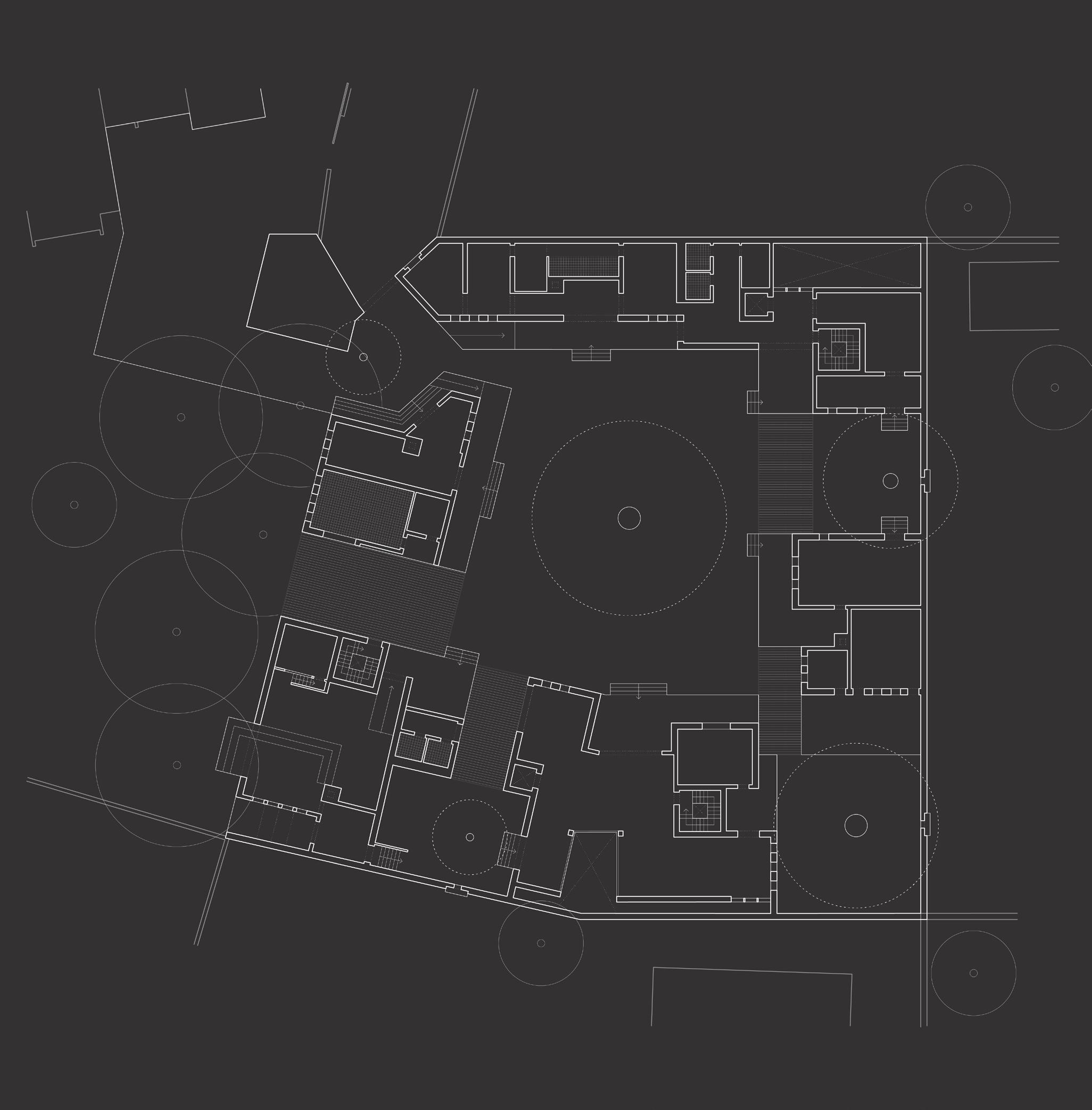

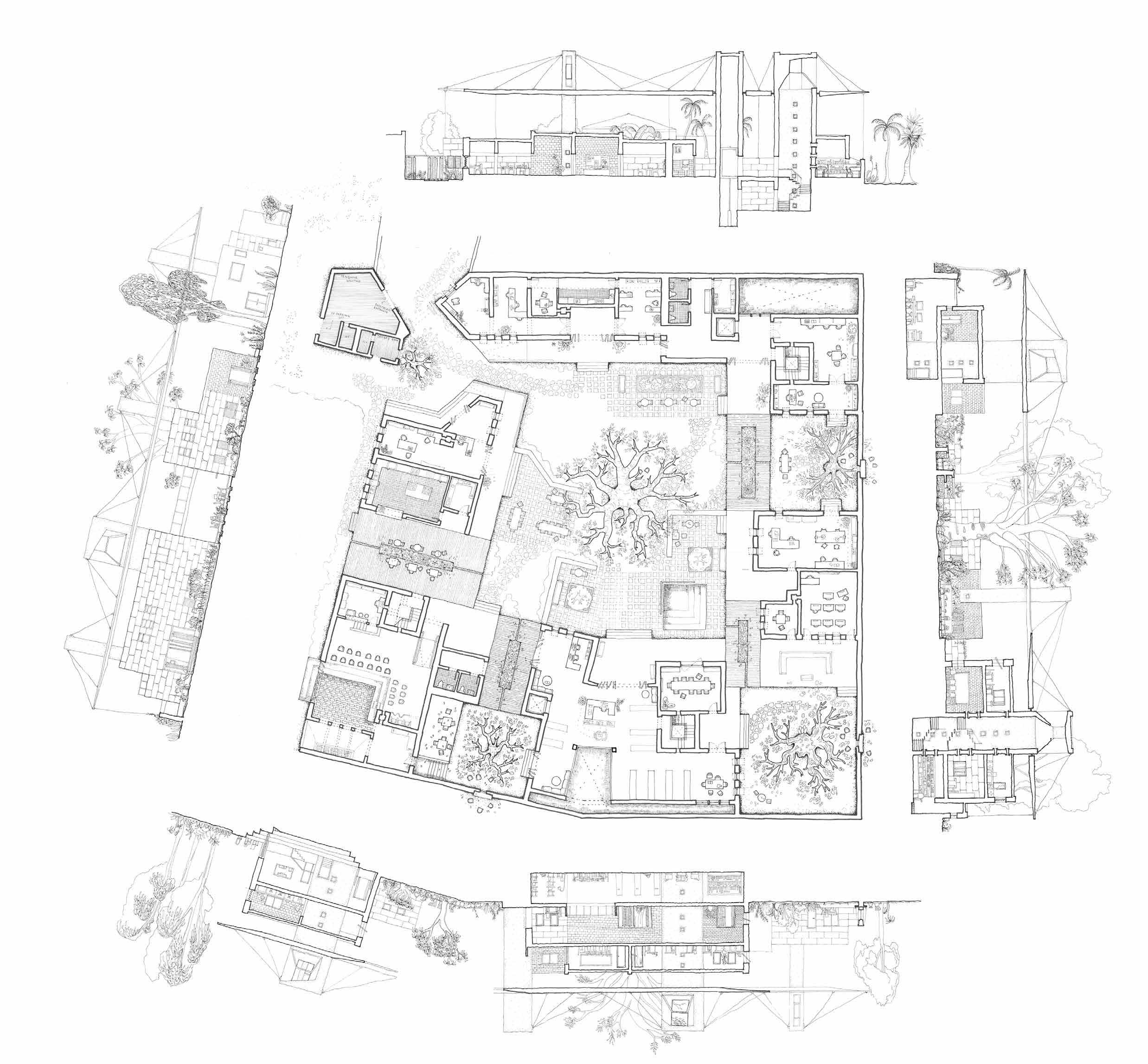

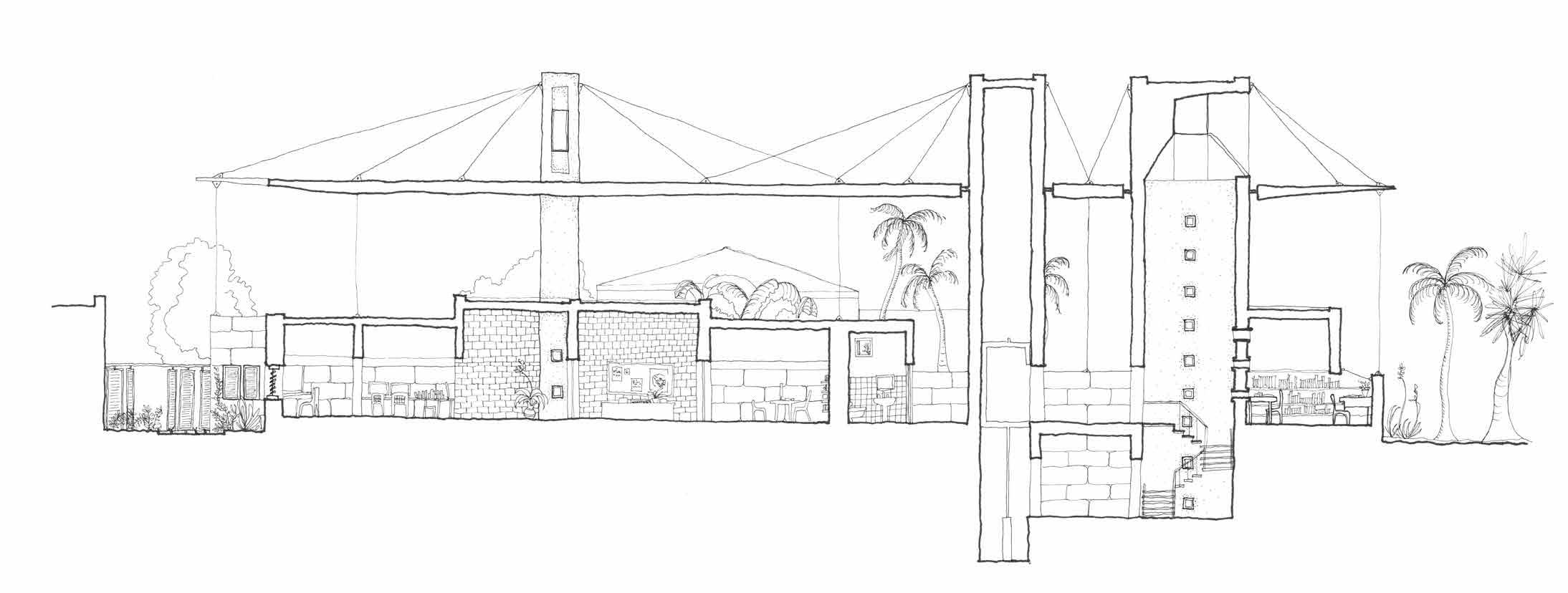

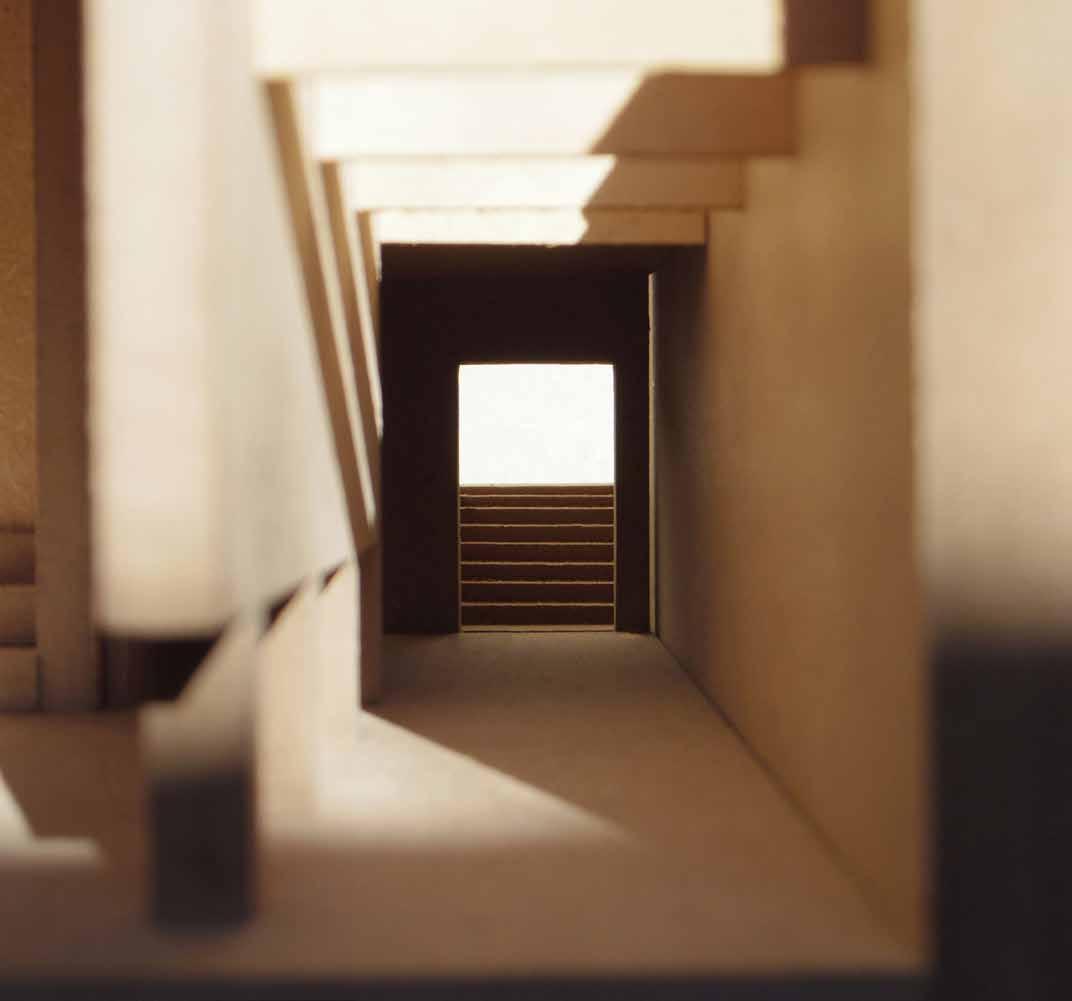

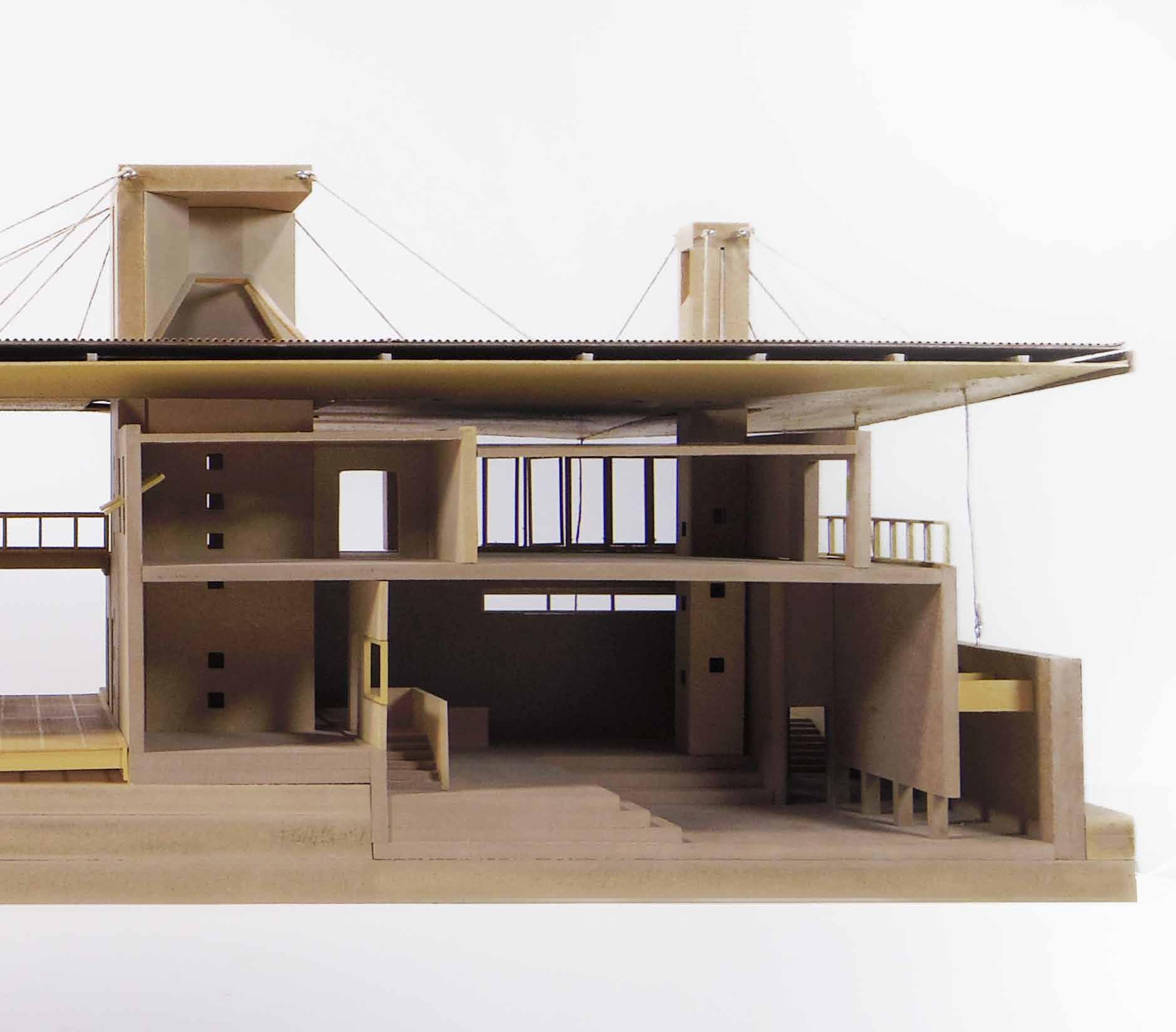

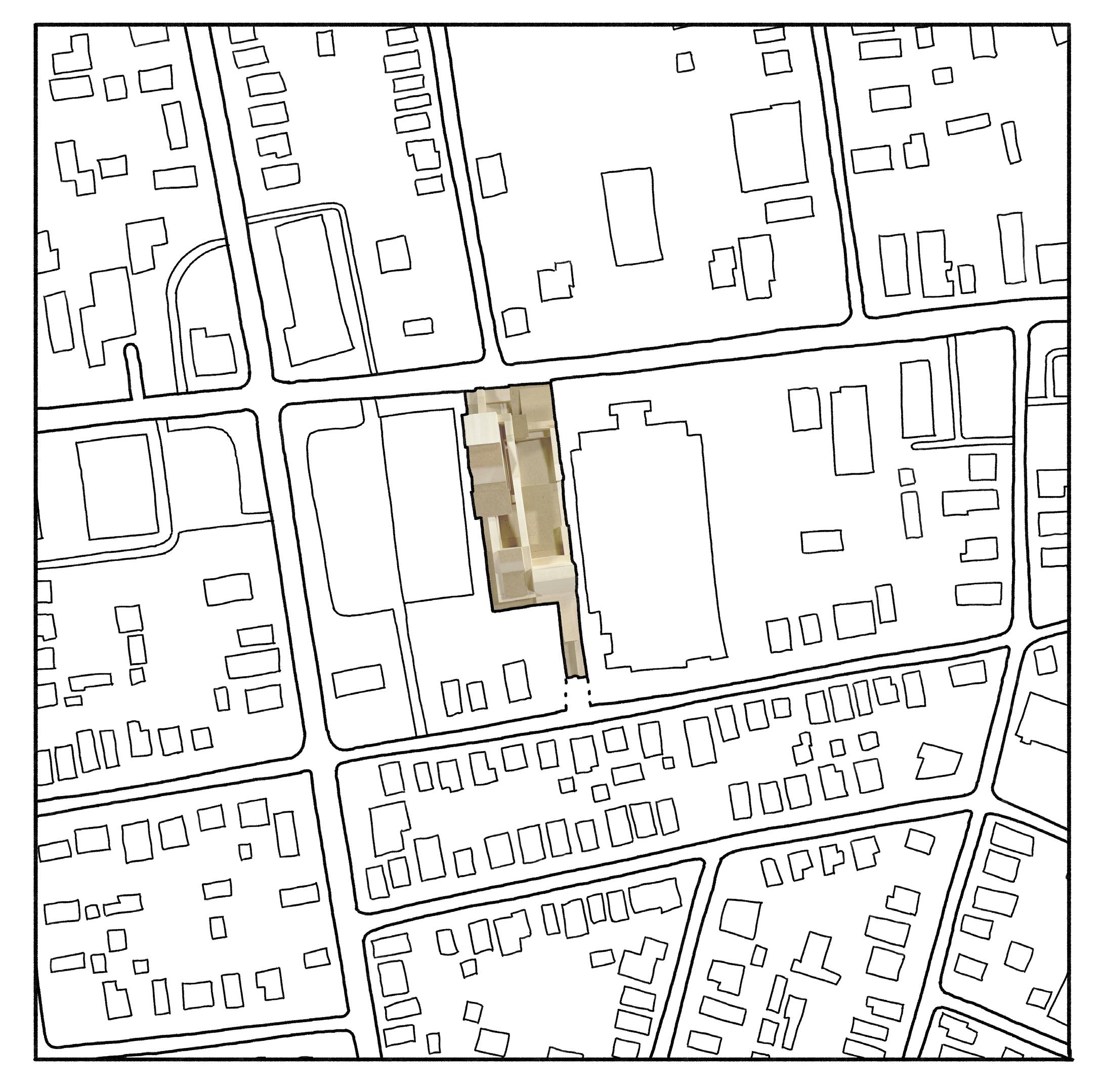

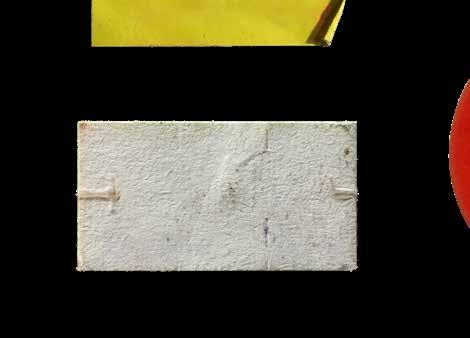

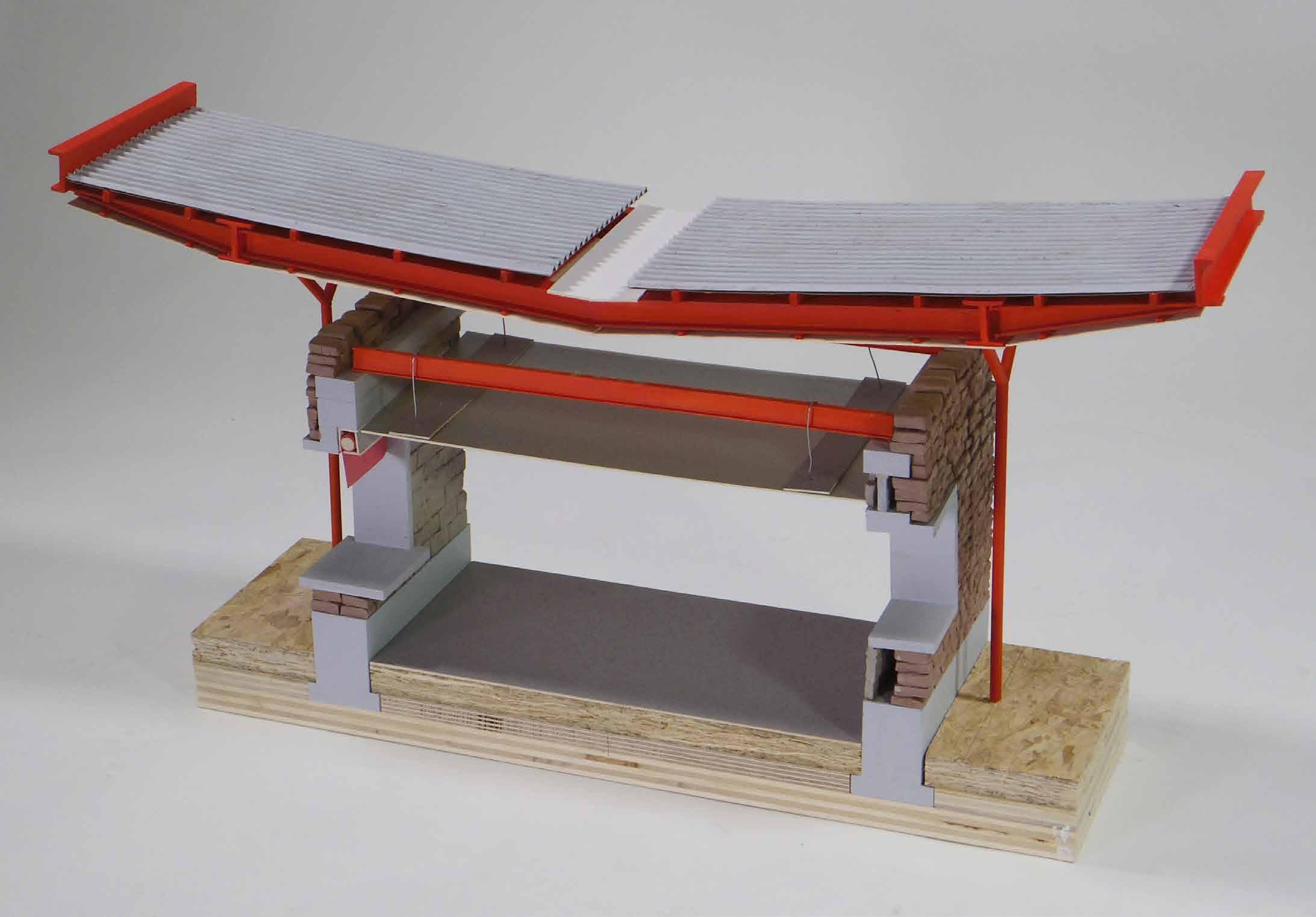

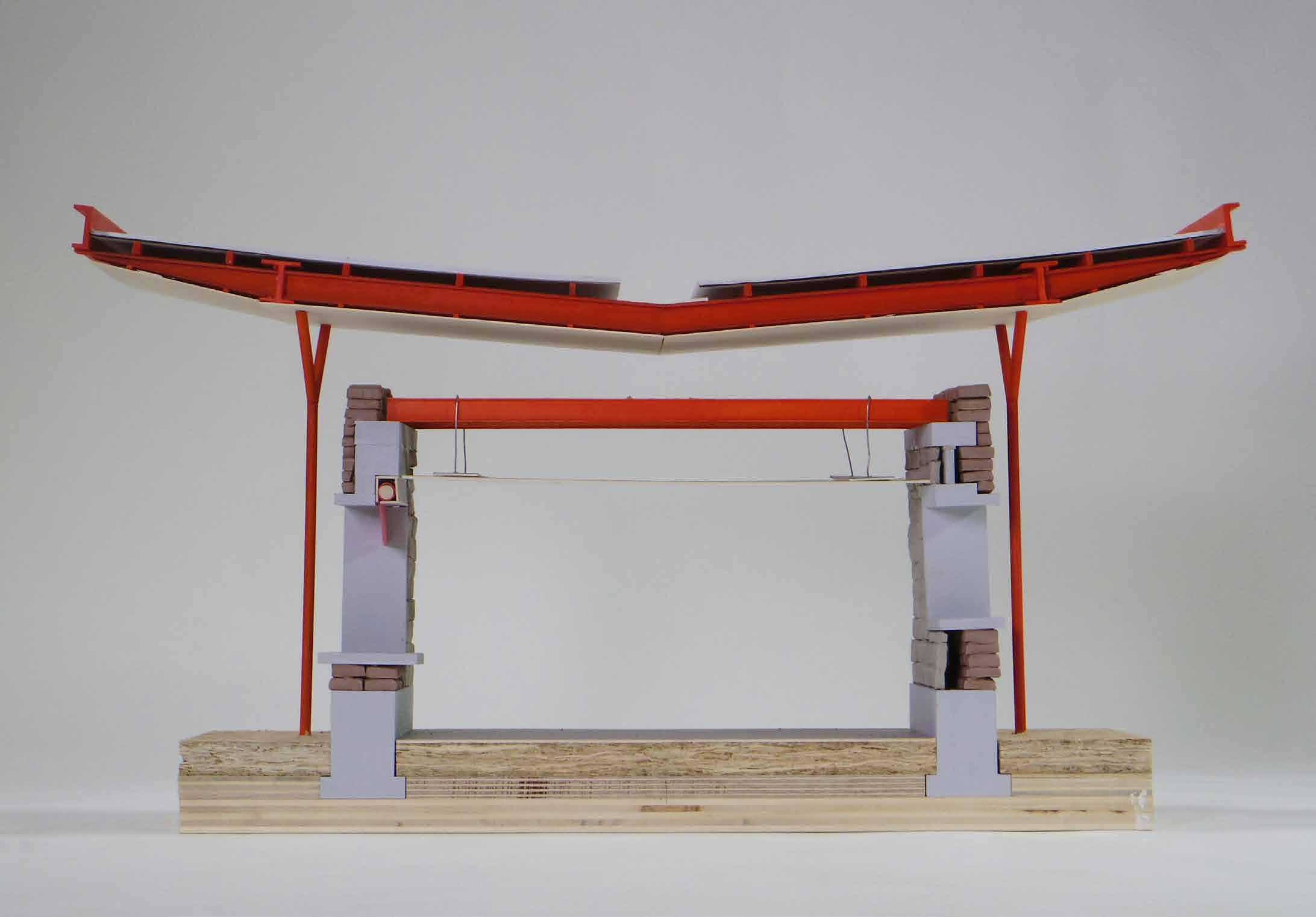

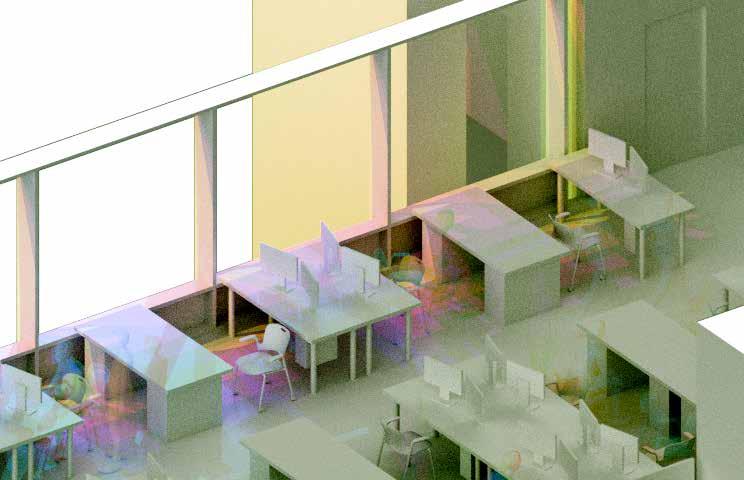

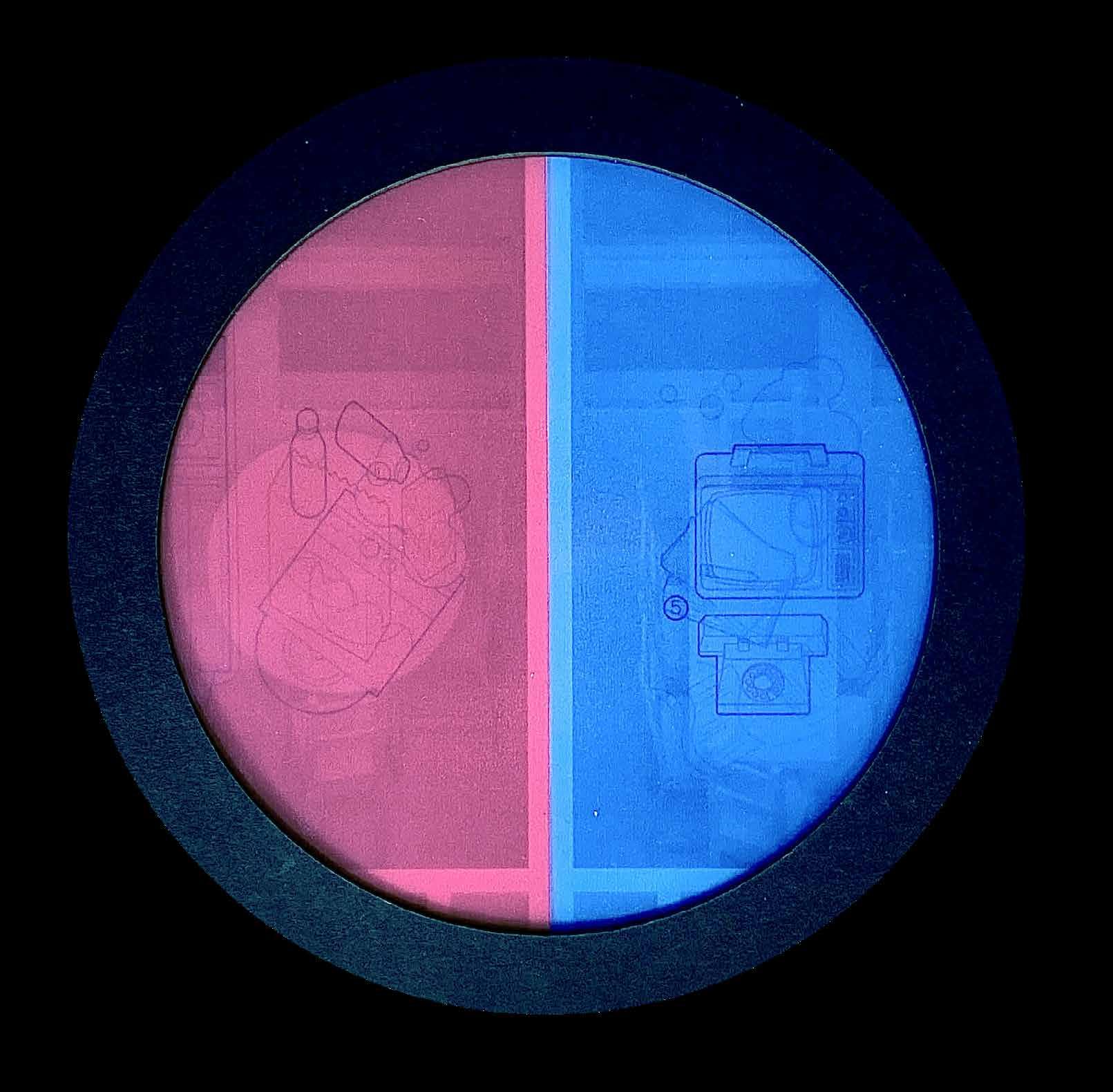

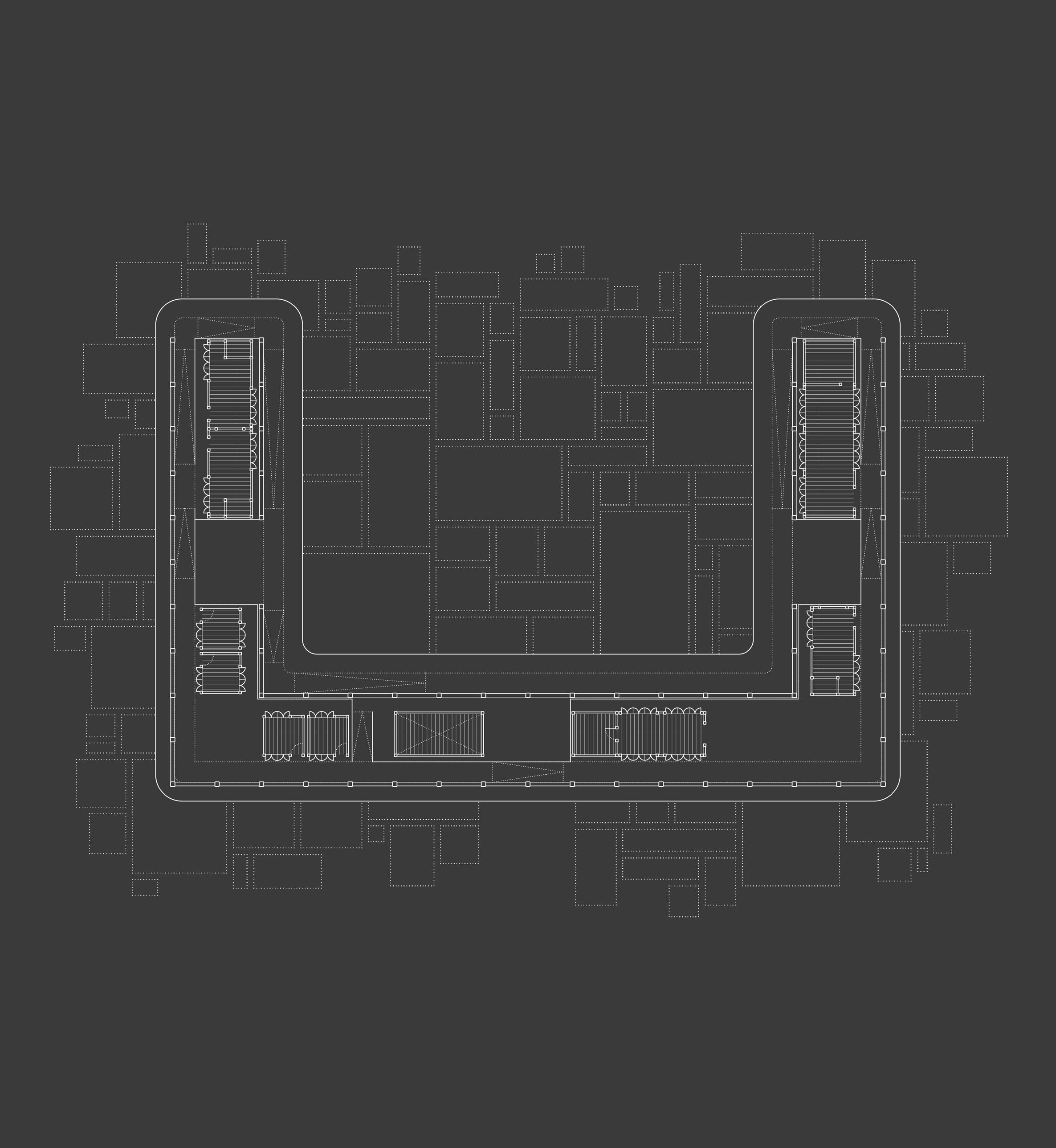

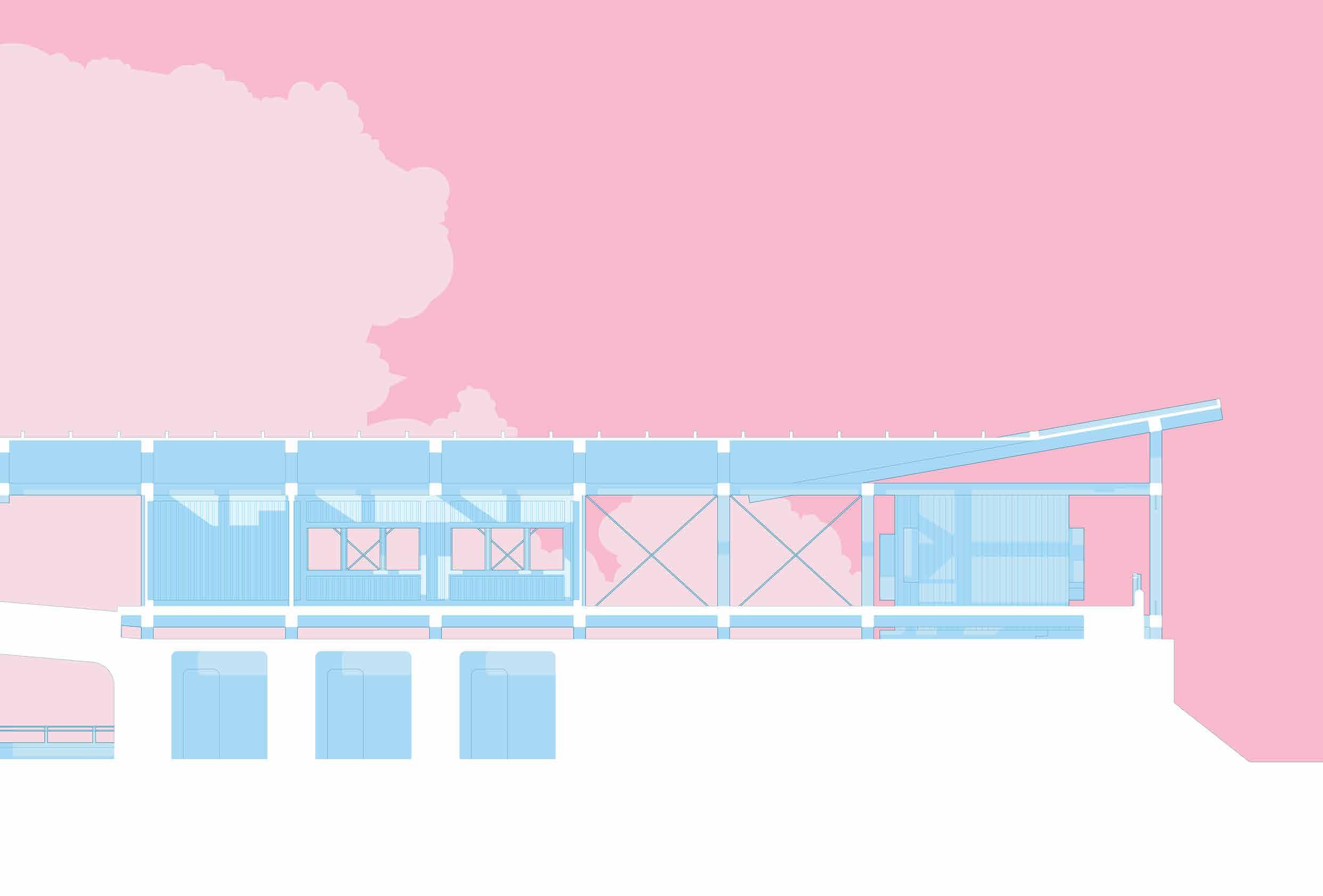

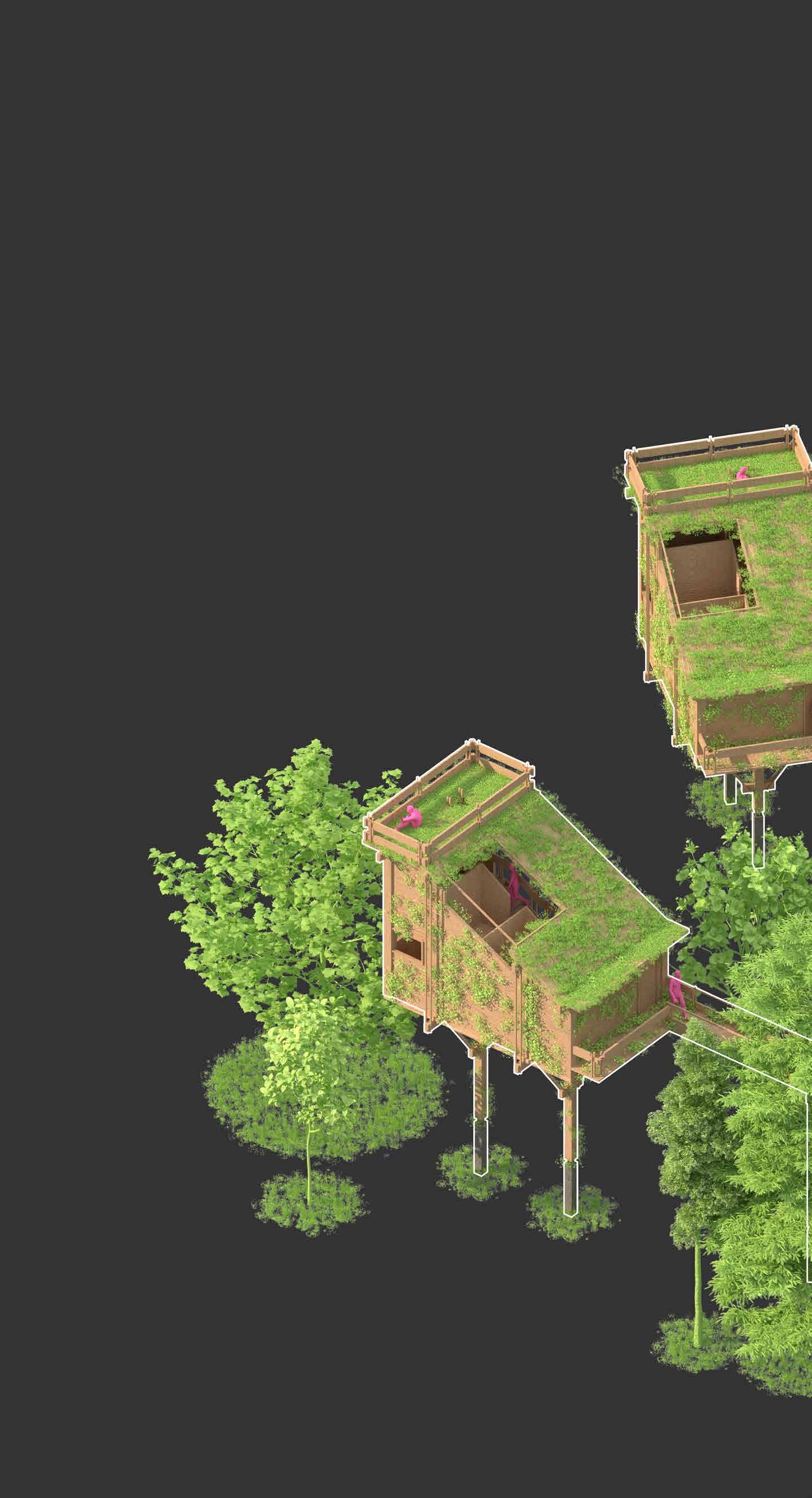

In Dakar, Senegal, the consturction of a new branch headquarters for the Goethe Institute is already nearing completion. The real building, built by this studio project’s advisor Francis Kéré, is a German language school and arts center. The challenge was to re-invent the realized building, giving new form to its programattic and cultural requirements.

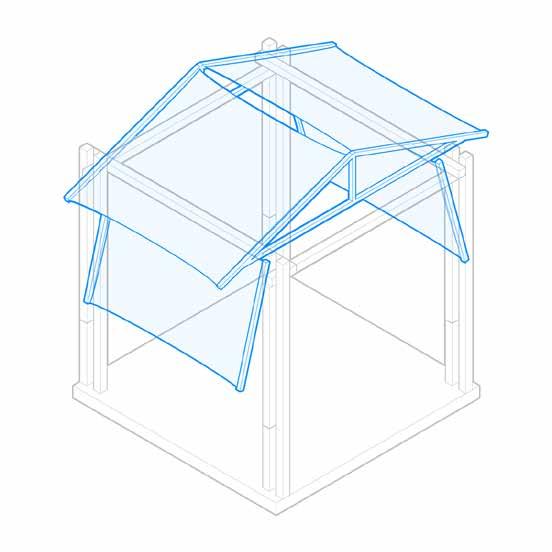

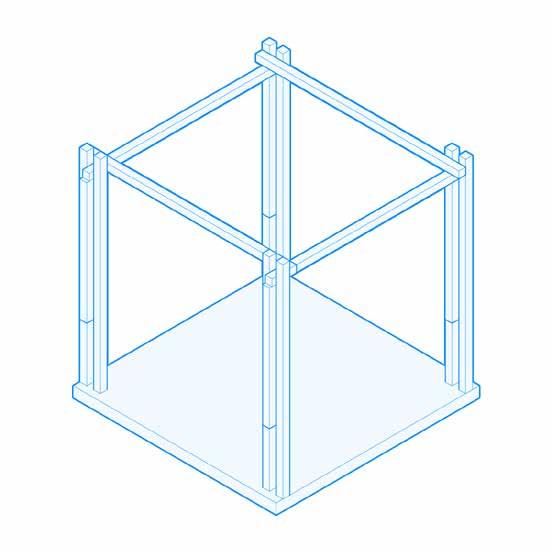

The proposal attempts to incorporate the edge of its pocket site into the building, such that the perimeter wall becomes architecture itself. Manifest as a skylight, a mezzanine, a corridor, or a courtyard, the treatment of this shared wall changes along the edge. What remains constant is a climatically sensitive roof, held by wind towers and chimneys, alleviating the building from the burden of bearing load and opening up new material possibilities.

The proposal draws also on a long cultural history of the Baobab tree, evoking a “village” which weaves in and around the Baobab at the center of the site and the Ficus, Filao, and Sapotier trees at the edges.

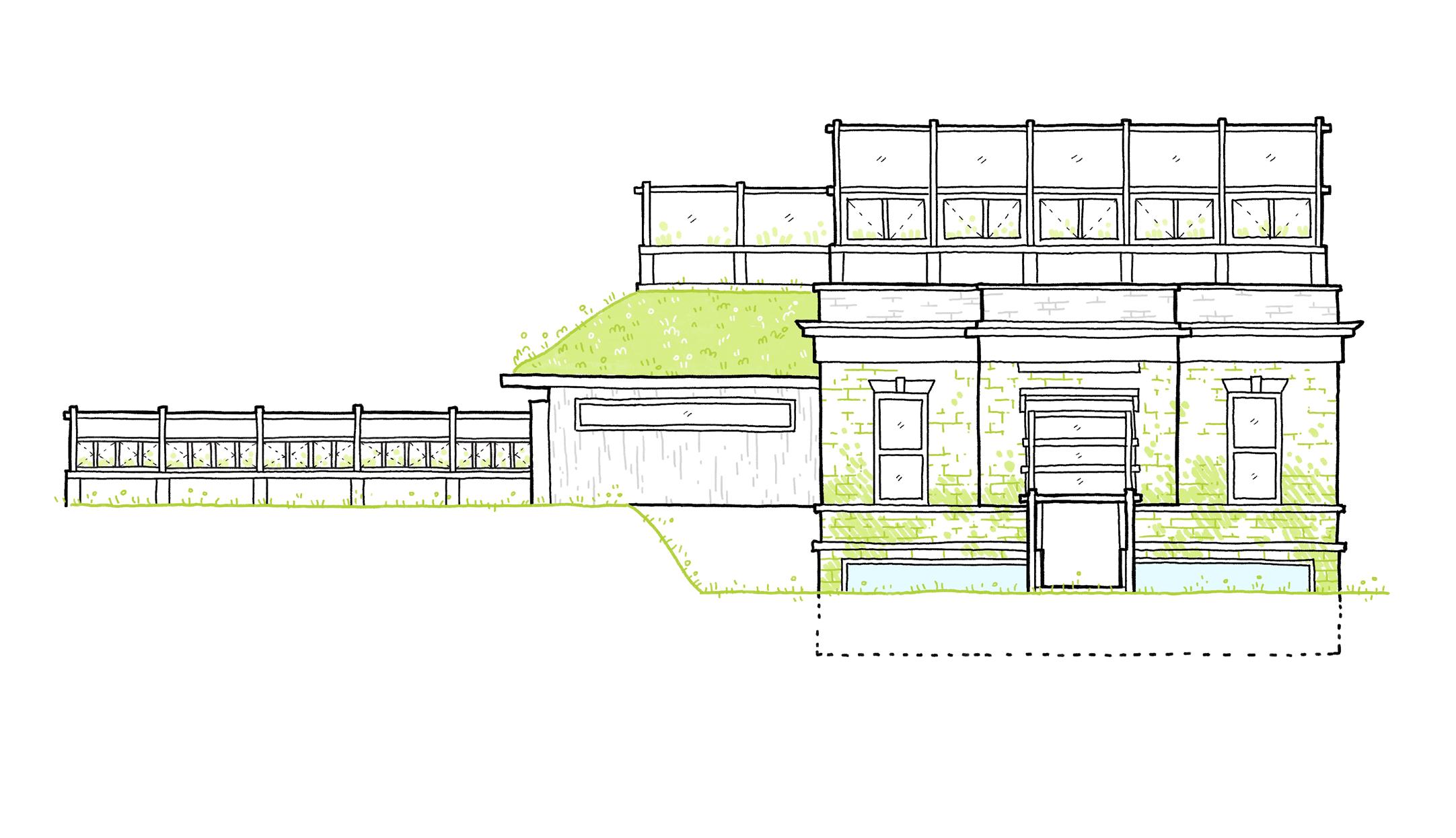

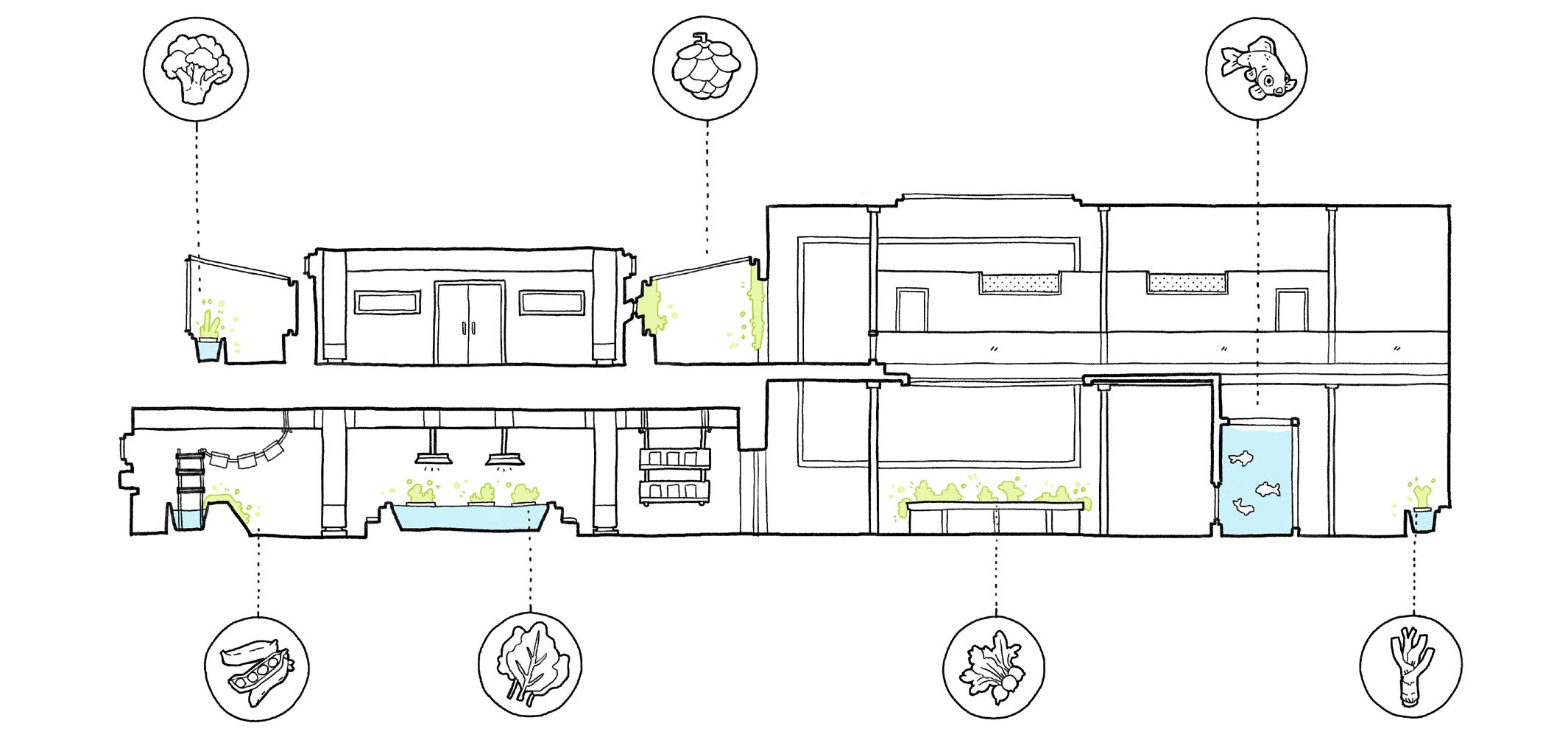

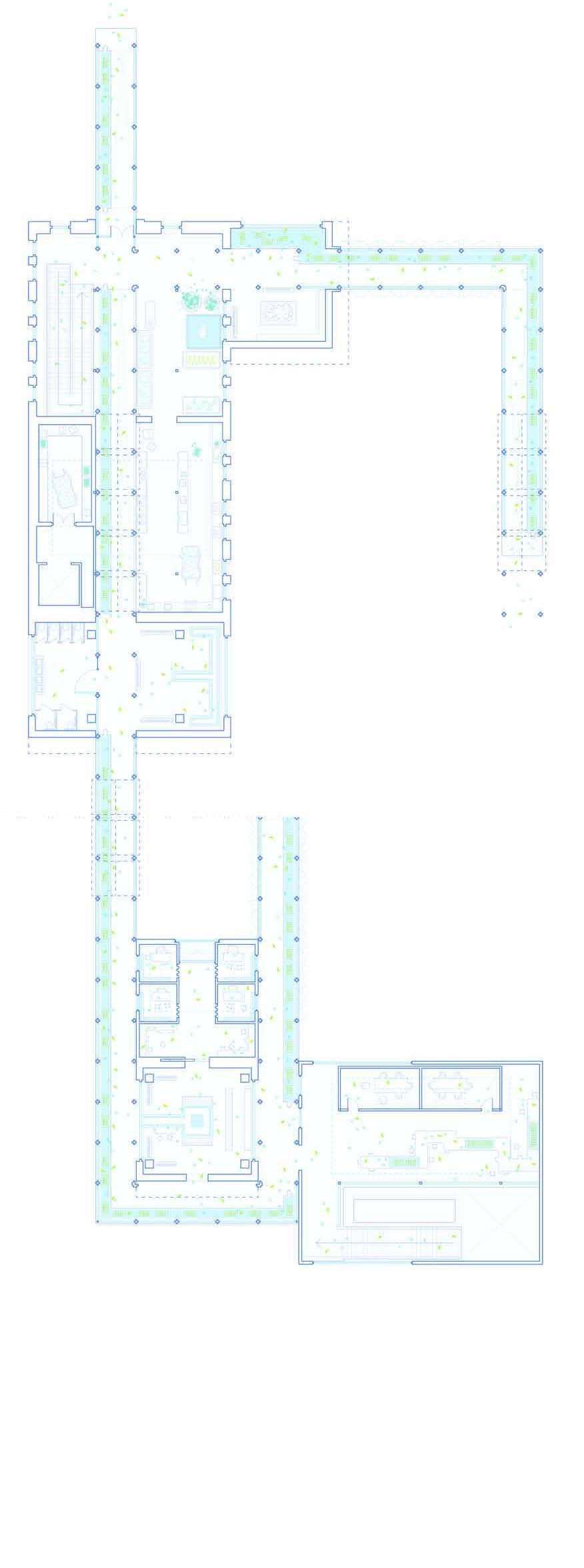

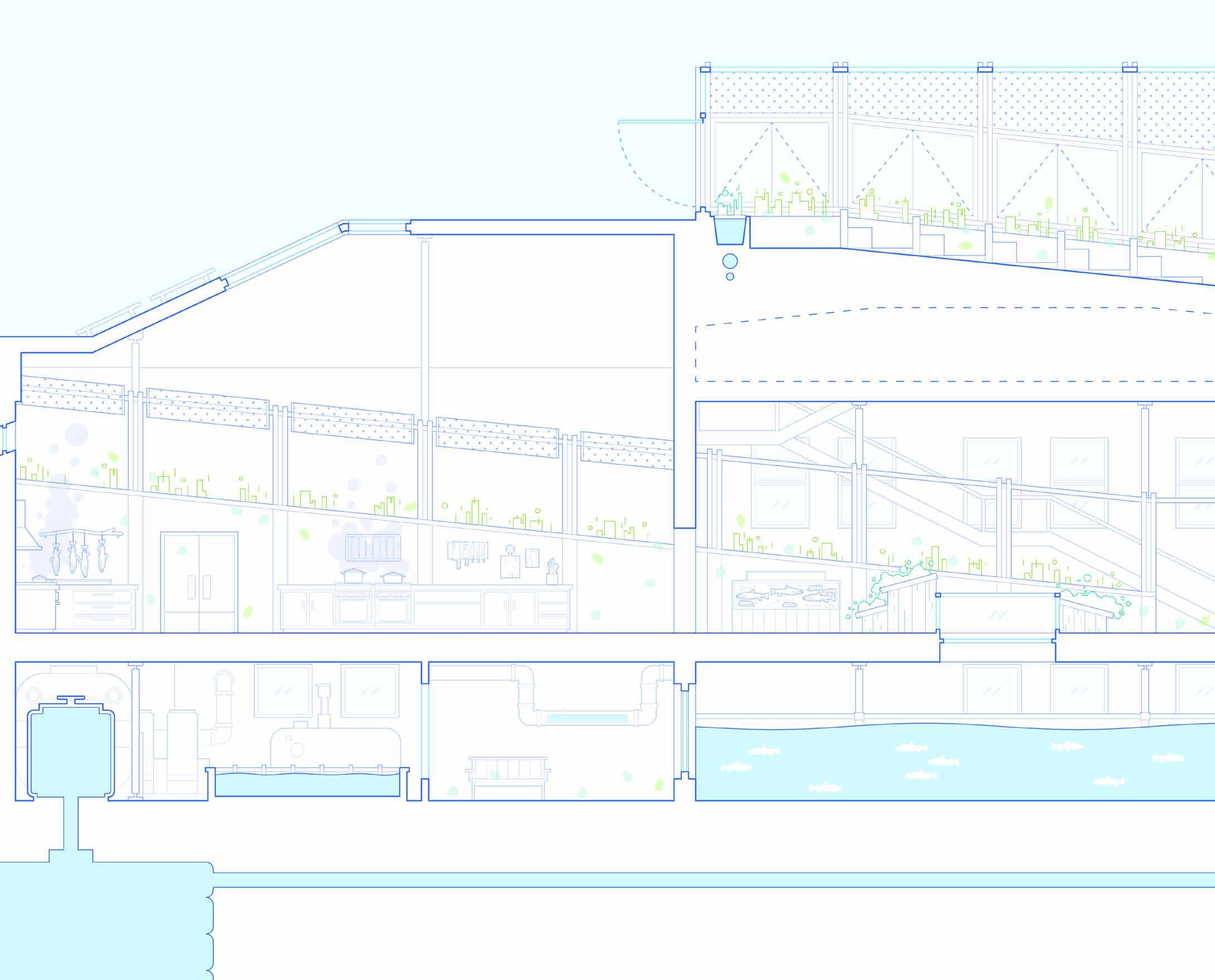

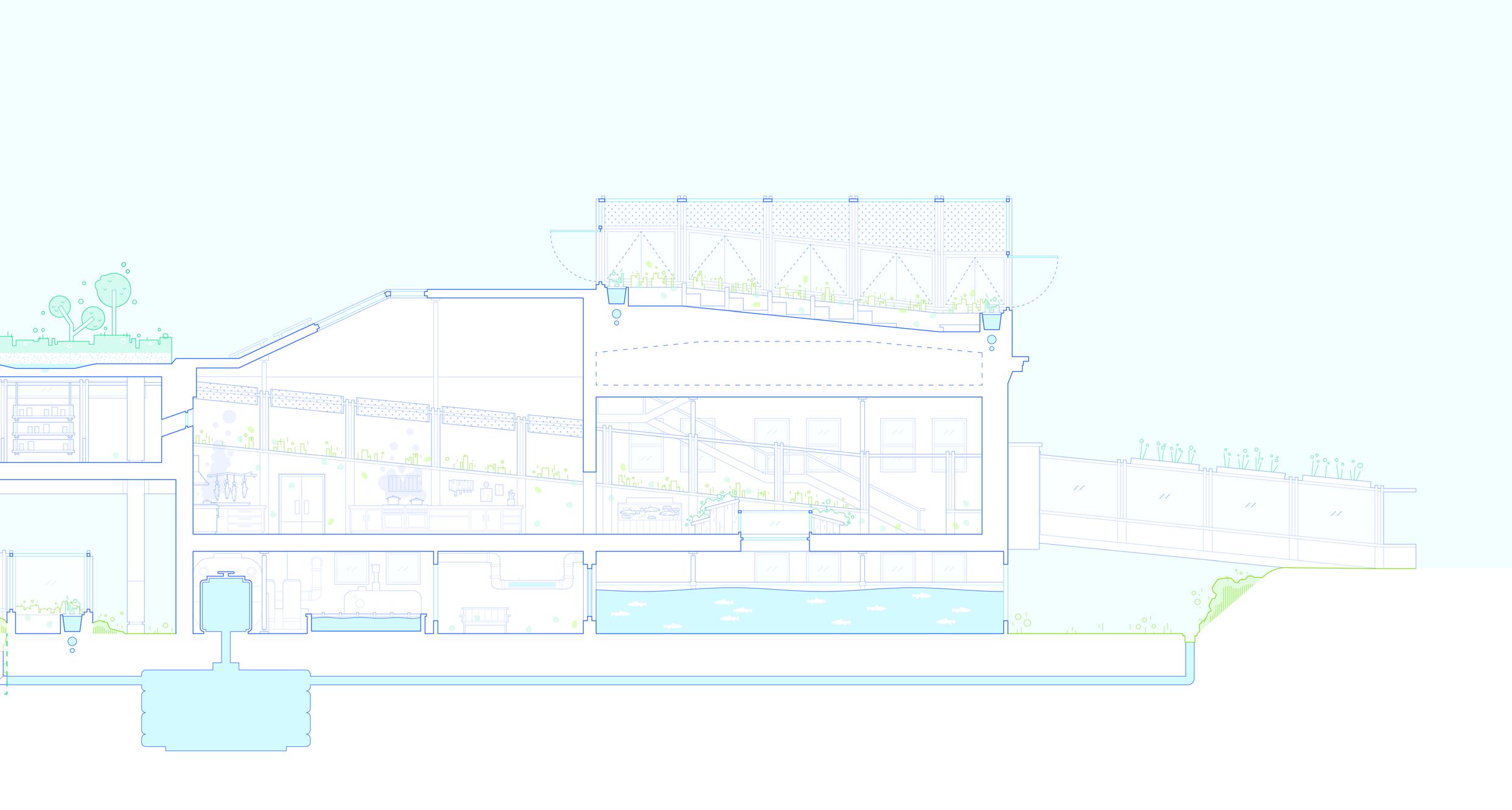

of a historic library building in downtown New Haven. The building is one of over 1,000 Carnegie Libraries built in the United States in the late nineteenth century.

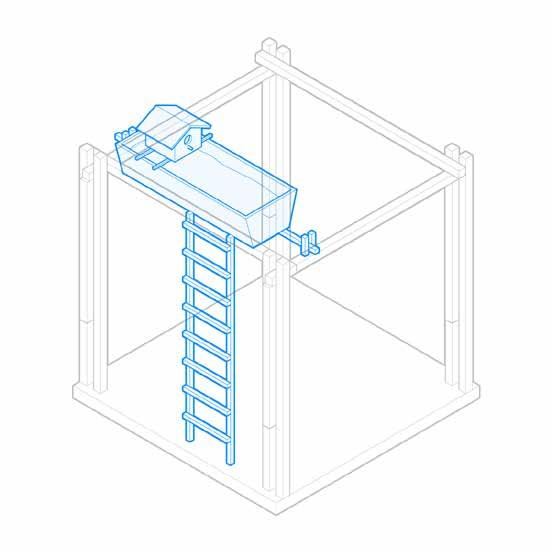

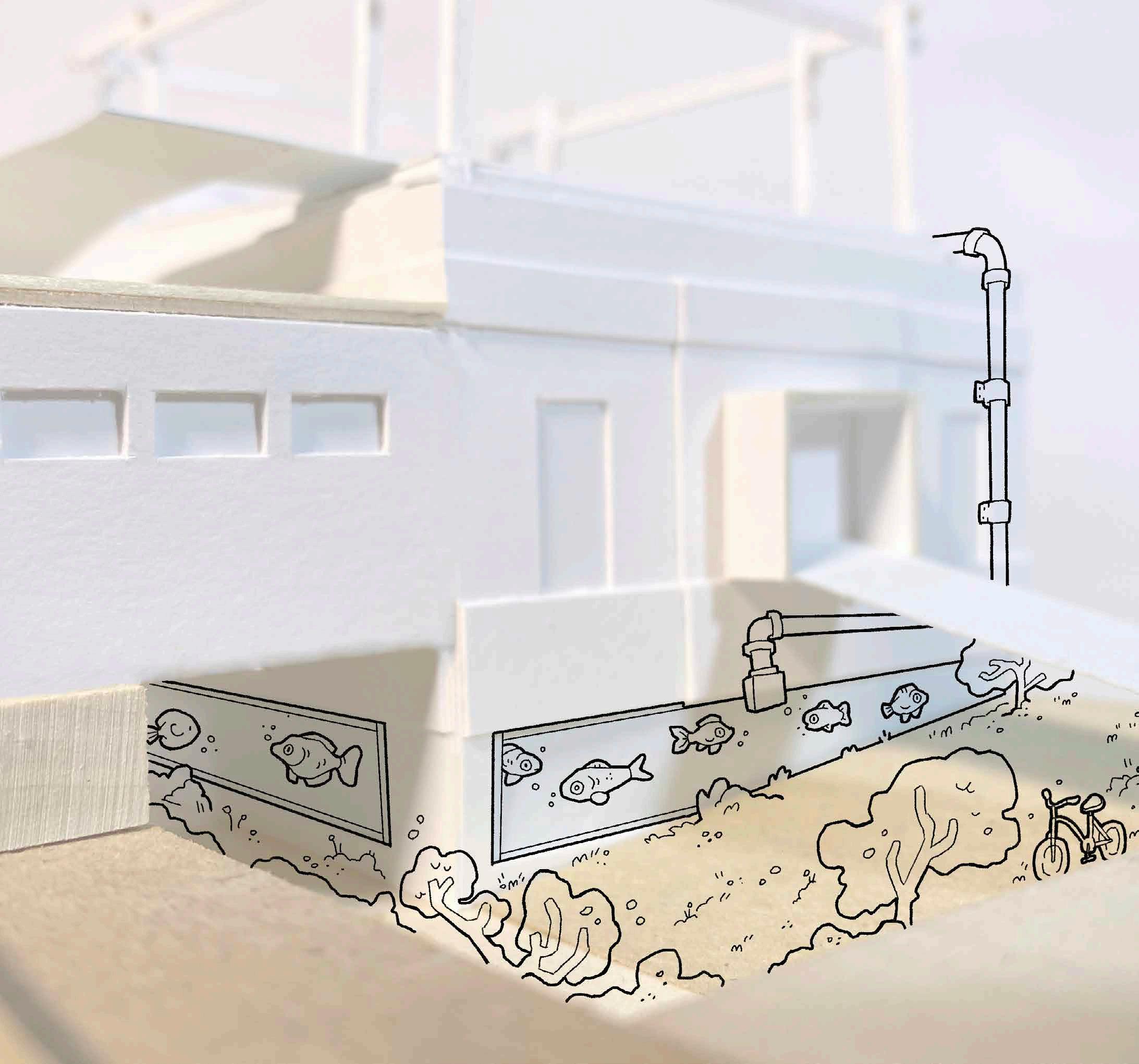

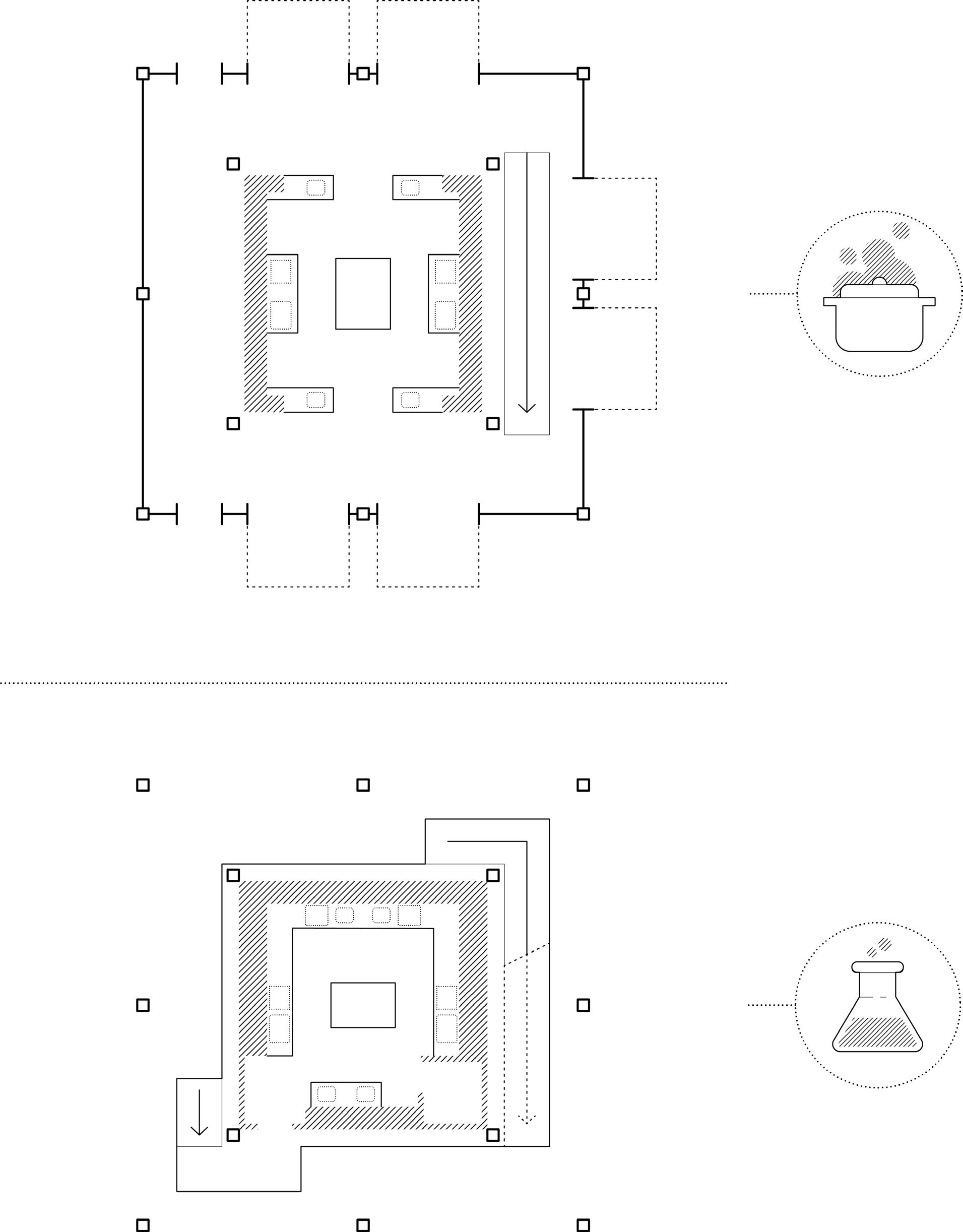

The proposal aims to expand the original 10,000 square foot program to accommodate an added revenue engine for the library: an aquaponics farm. The farm generates produce and fish which can be sold in the building’s new front market, but also promotes spaces for urban agriculture education and active community participation in growing food.

By distributing the inherited library program into small pieces across the site, added programs can enjoy the benefits of their own libraries of appropriate reading material: a children’s library next to the daycare, a cookbook library next to the market, and so on. An attenuated garden-ramp weaves together those scattered books, circulating water and people from the very top of the building to the fish tank below.

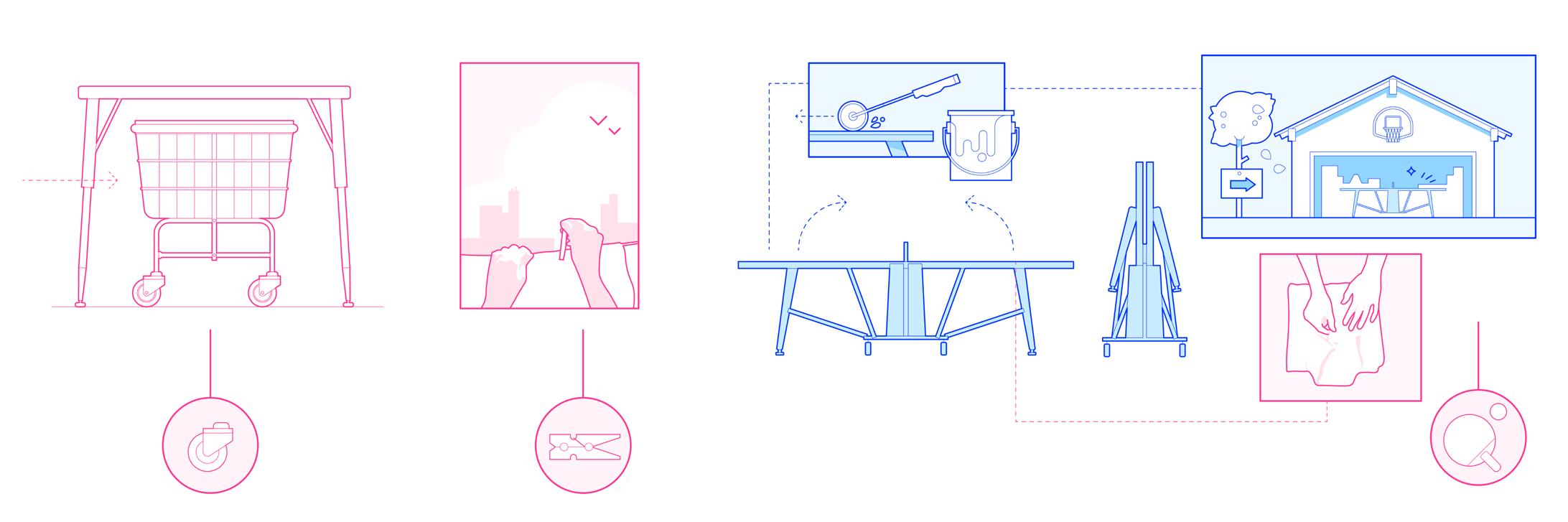

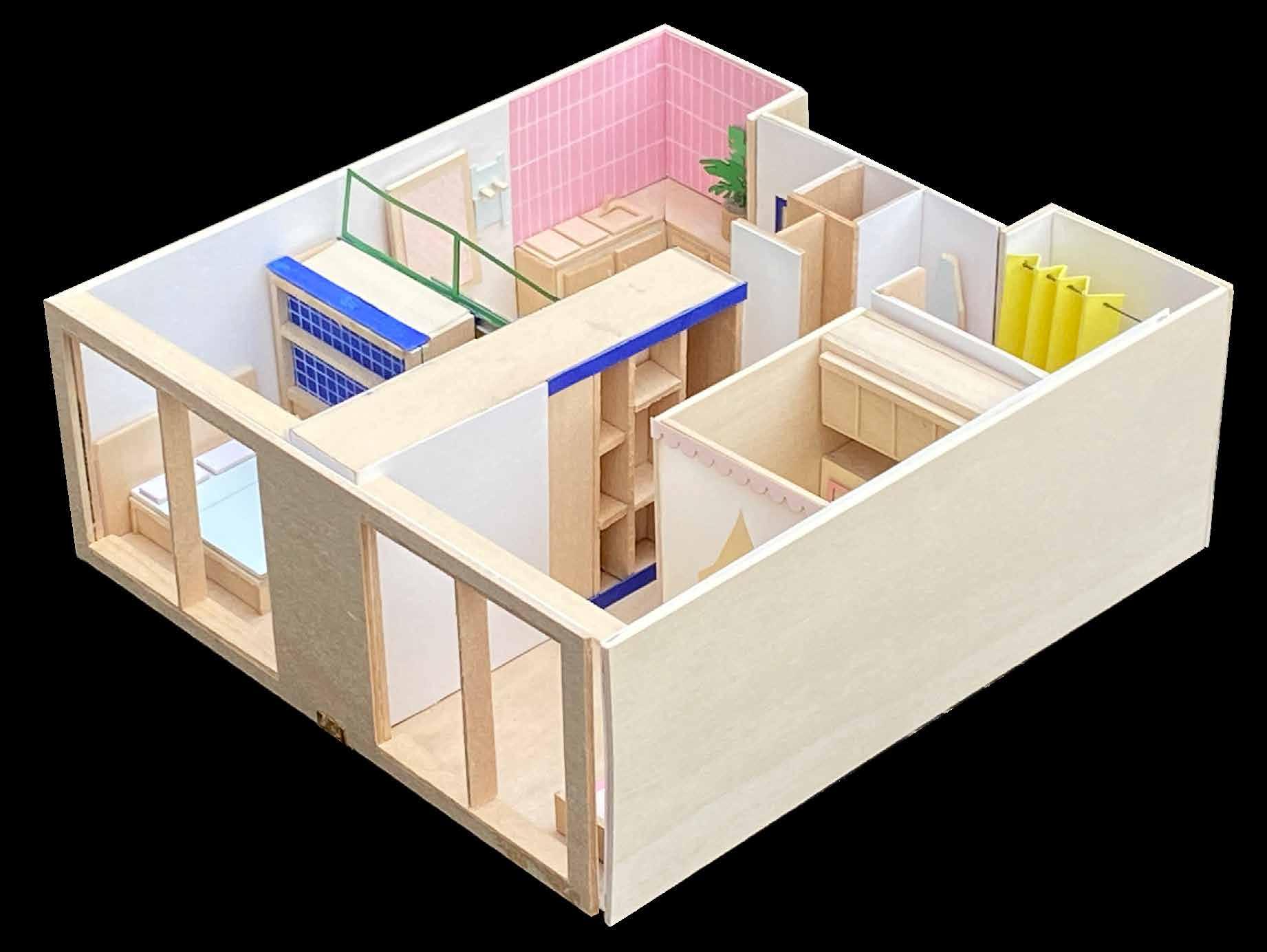

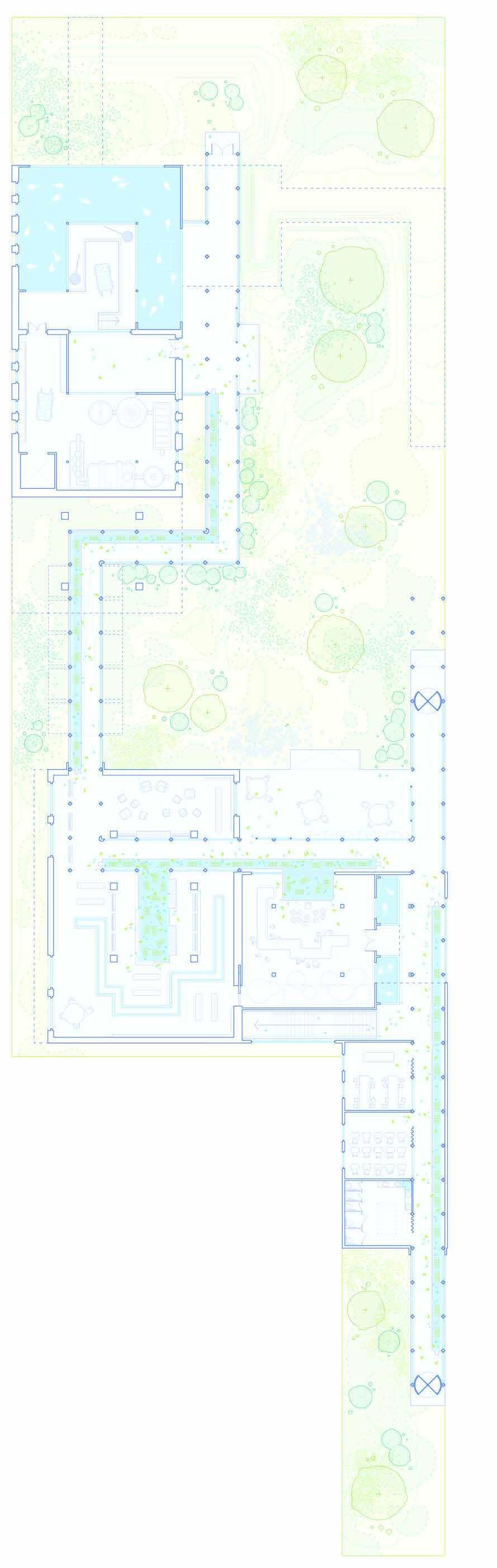

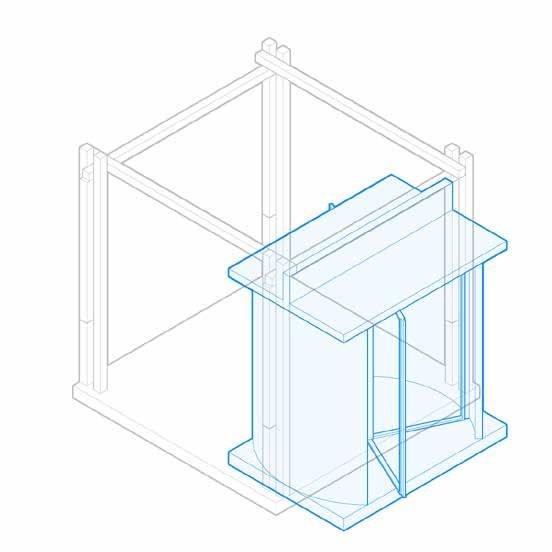

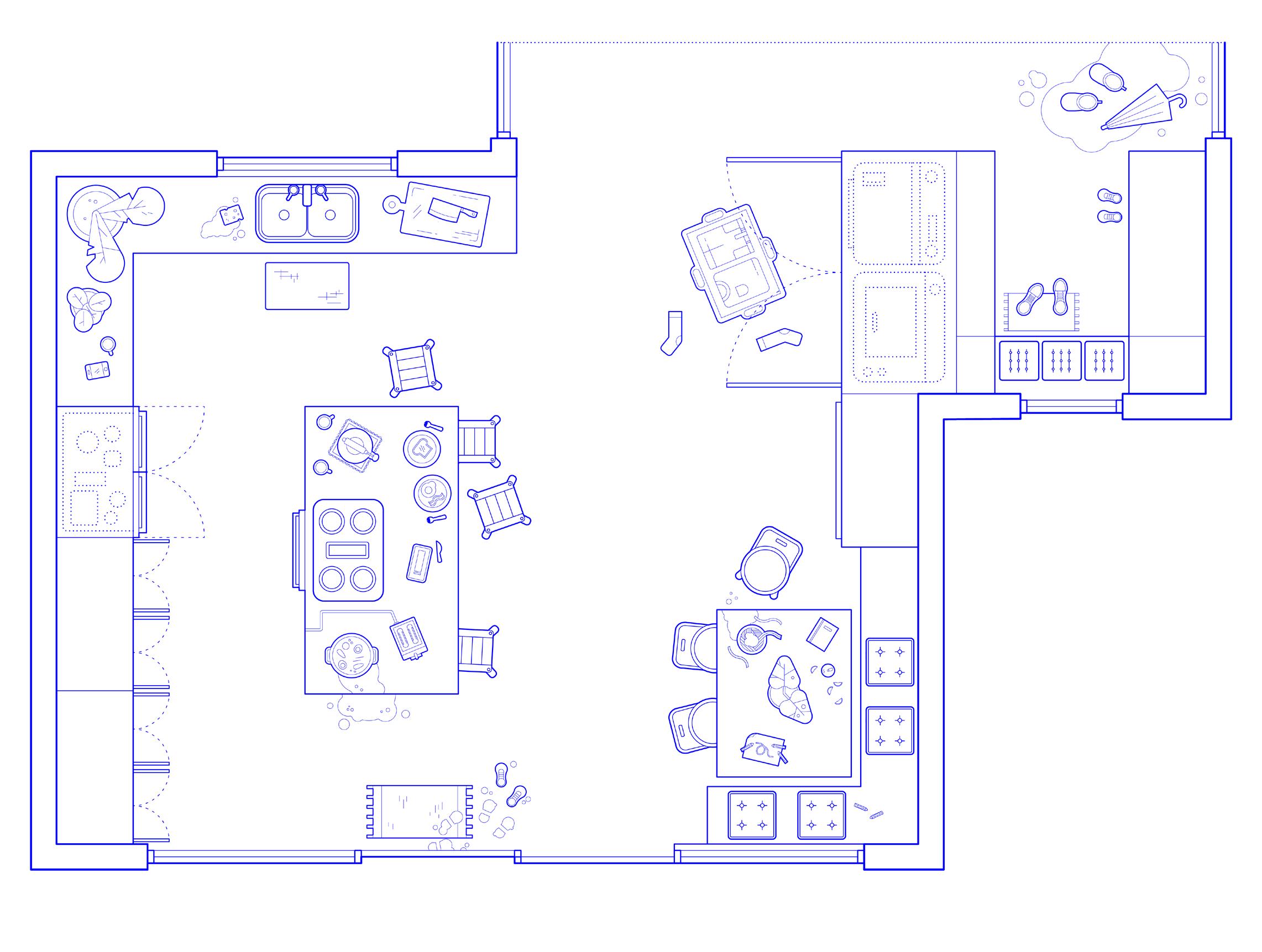

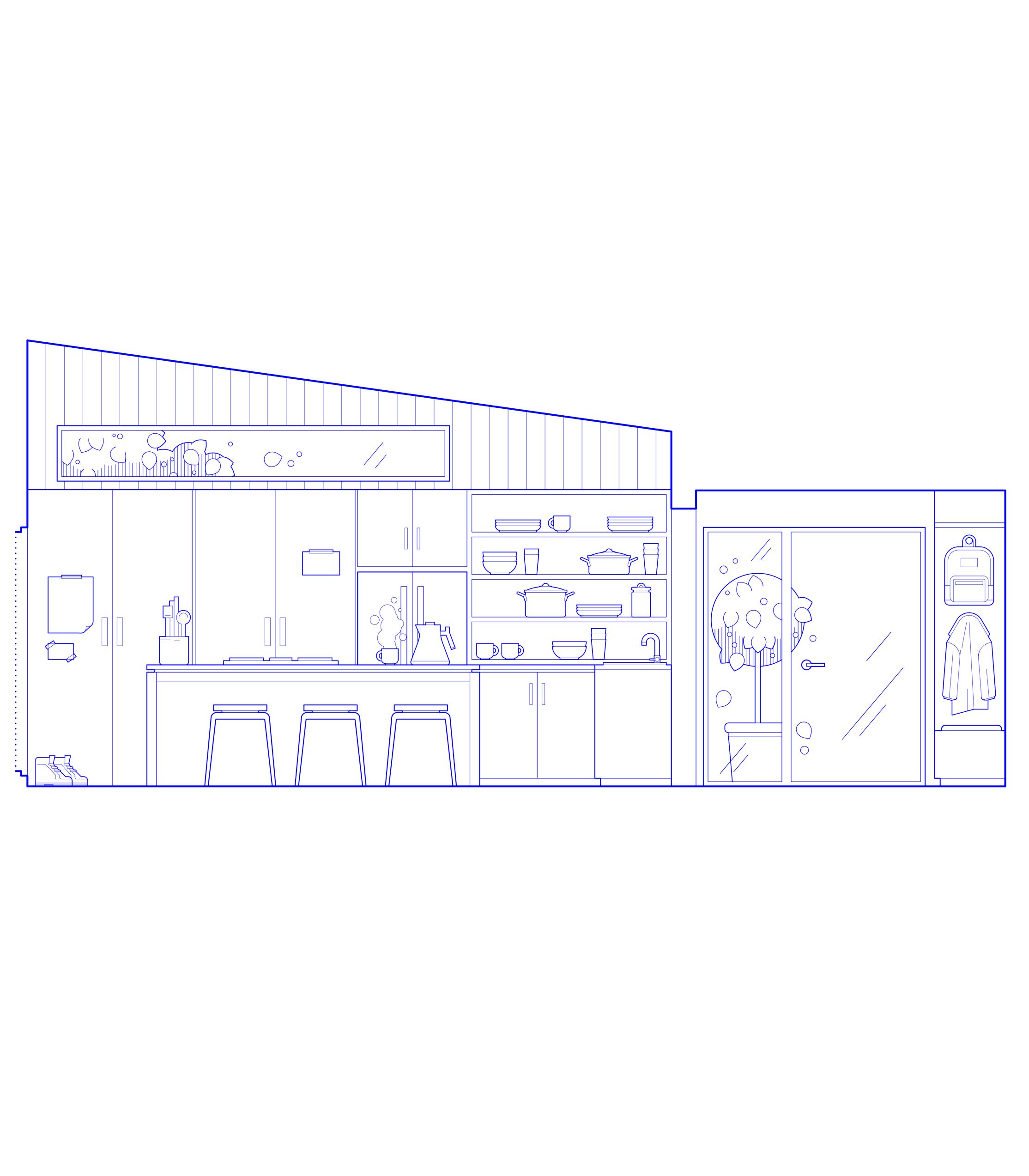

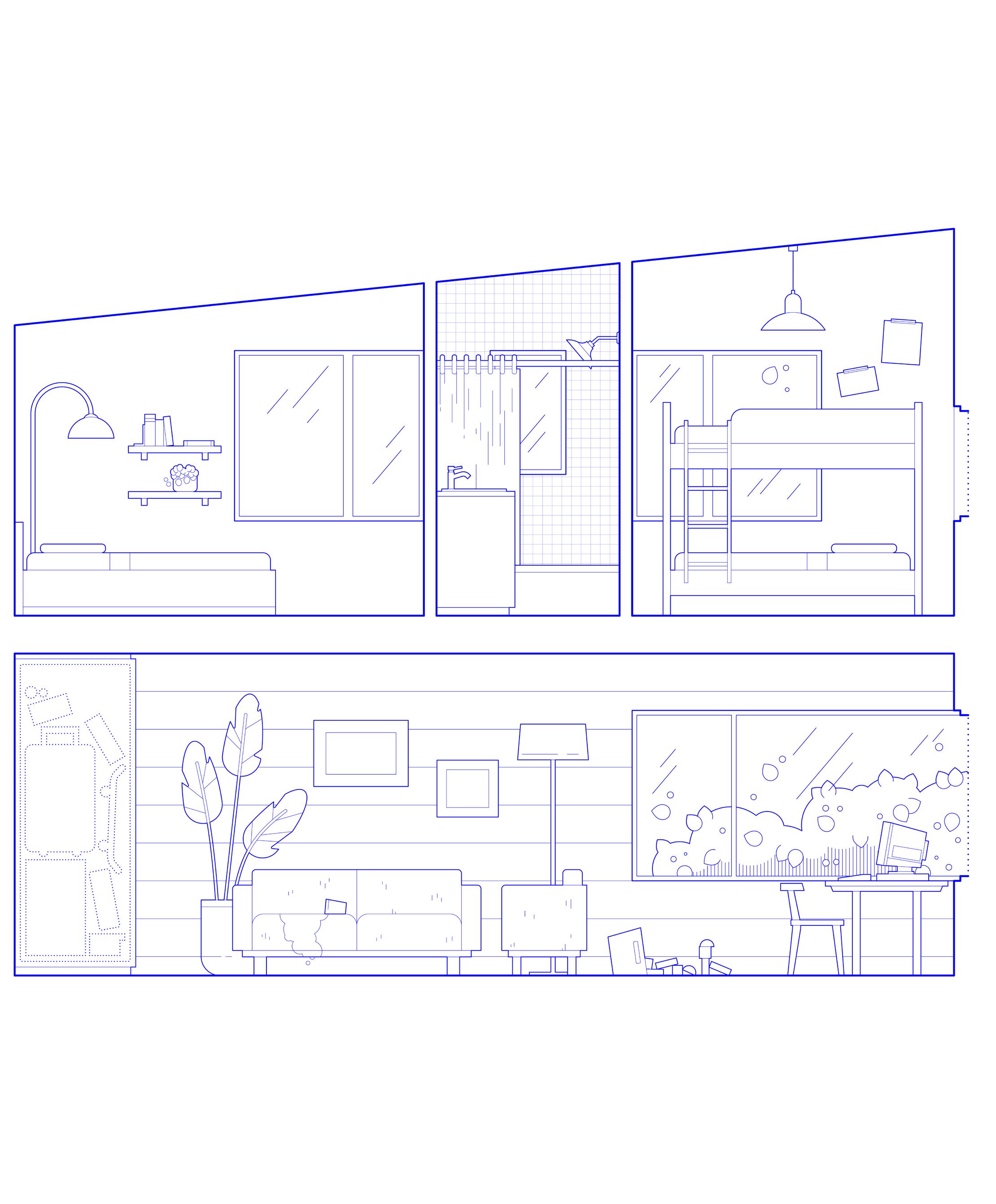

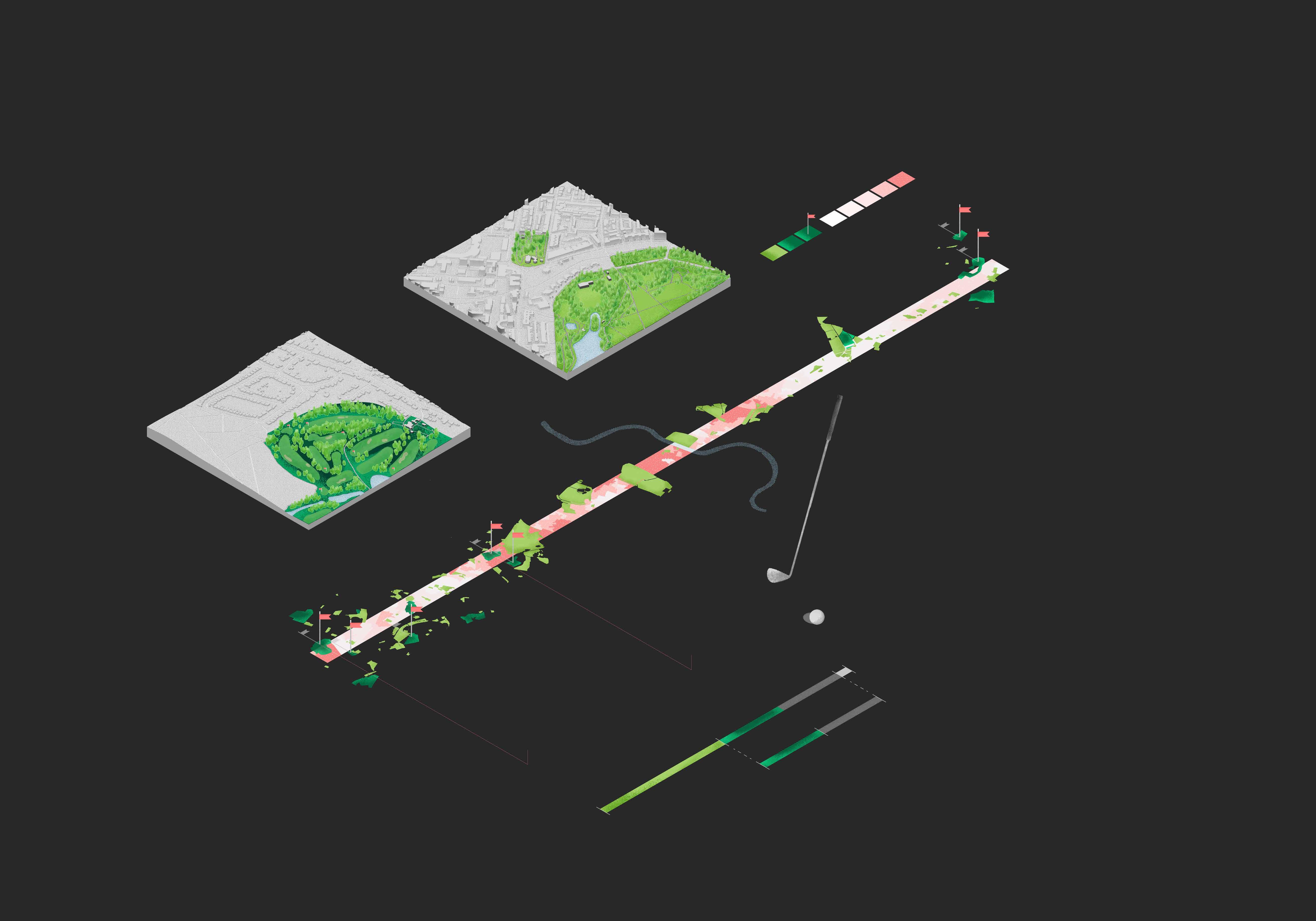

Challenged with sheltering two families under the same roof, this house was designed for the teachers at the Friends Center for Children. Space-saving techniques, generous storage, and everyday paths of travel were key considerations for the internal organization and furniture scale of the home.

The “ribbon” of circulation in this house divides the public and private zones, delineating what is “mine” and what is “ours.” The ribbon begins at the driveway, expanding for the car park, before funneling itself straight through the house. It is marked by a consistent covering, a flat green roof, which cuts through its shed siblings. It lets out twenty feet after it has entered, sloping down with the bedrock below to a backyard and fire pit.

In sharp contrast to the ordered interior, the wild landscape acknowledges the patch of forest which covered the plot before its development.

[ ELECTIVE WORK ] FALL 2022 — SPRING 2025

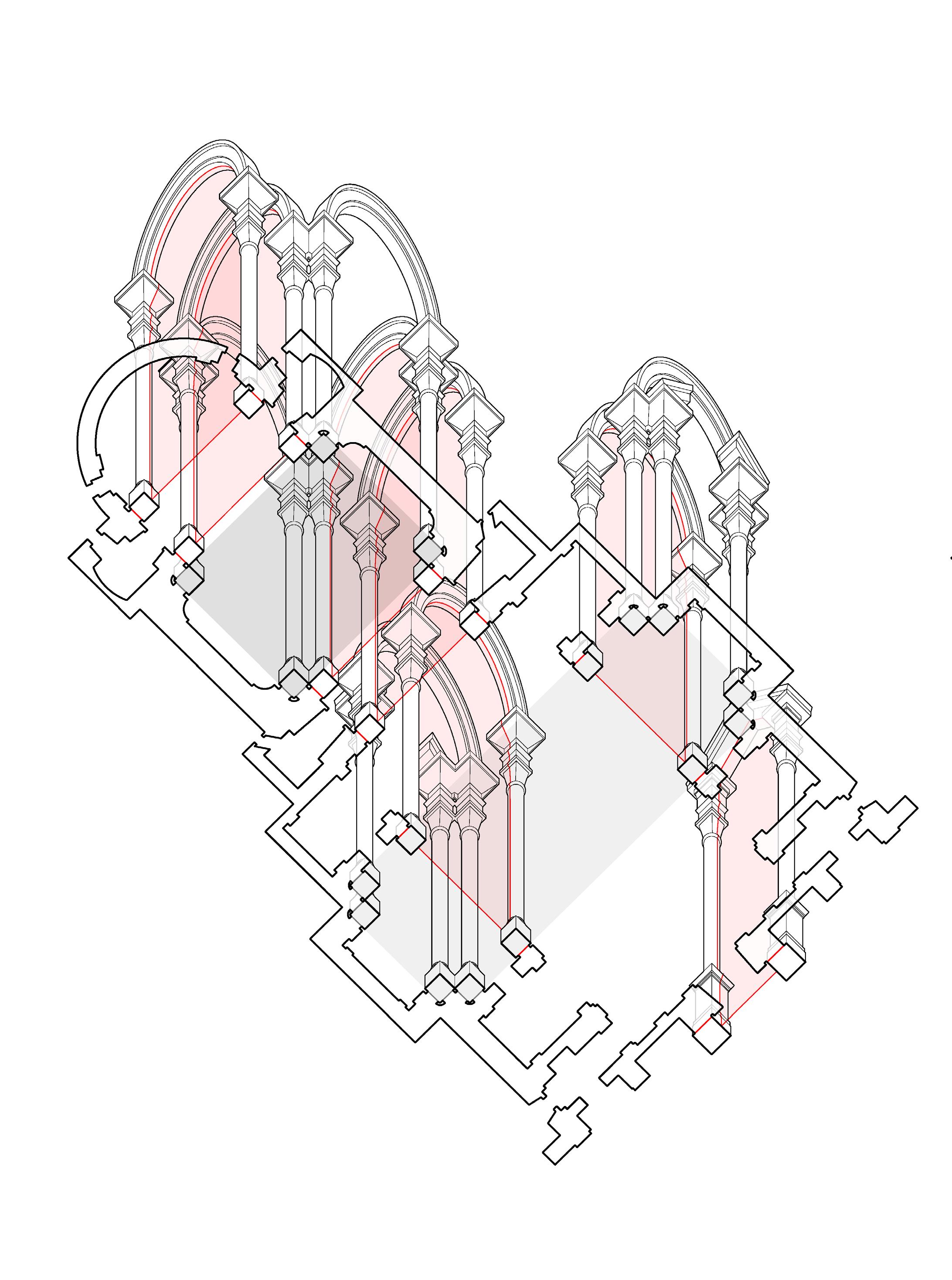

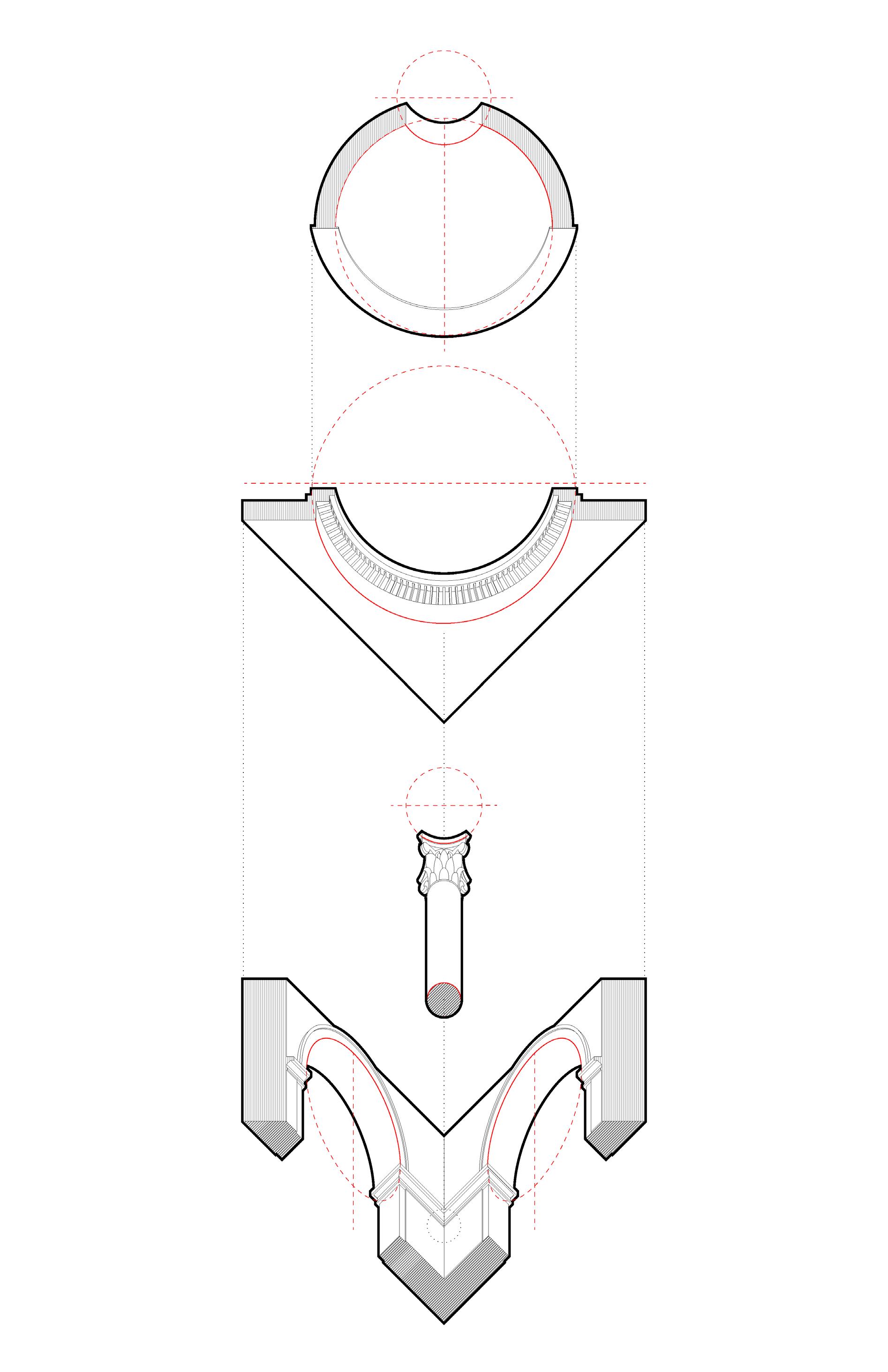

T.E.R. Precedent Study (Worofila)

ADVANCED STUDIO

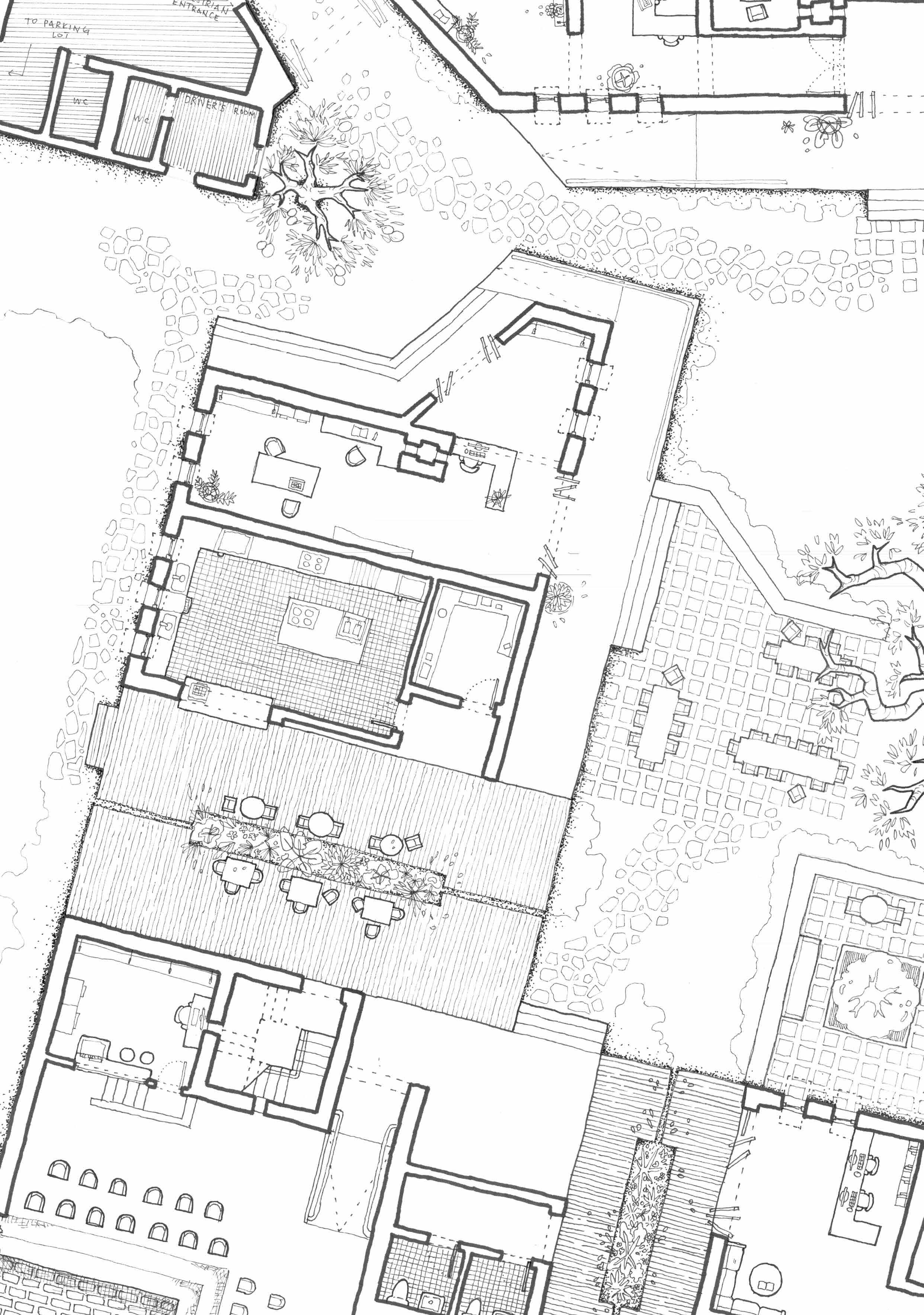

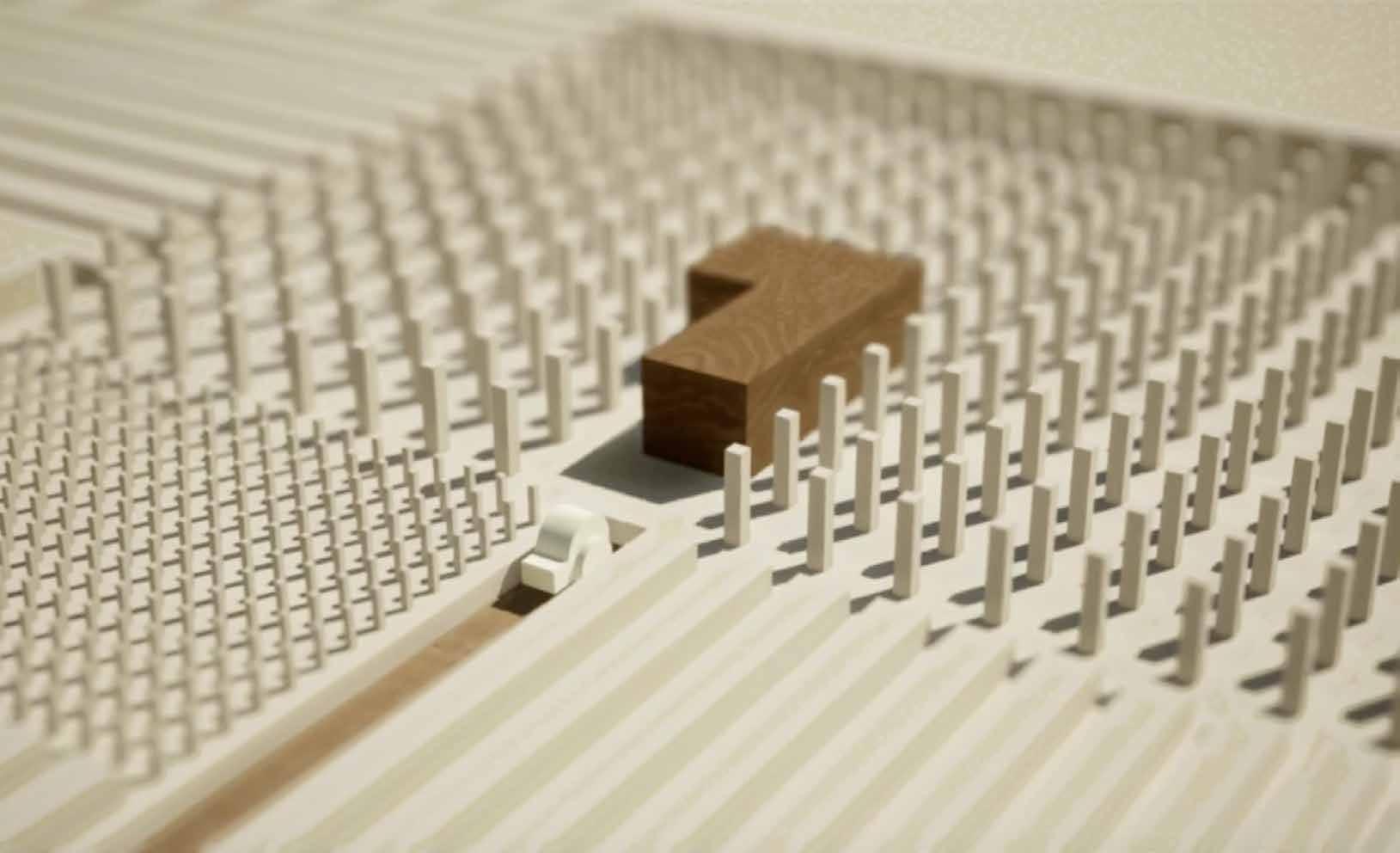

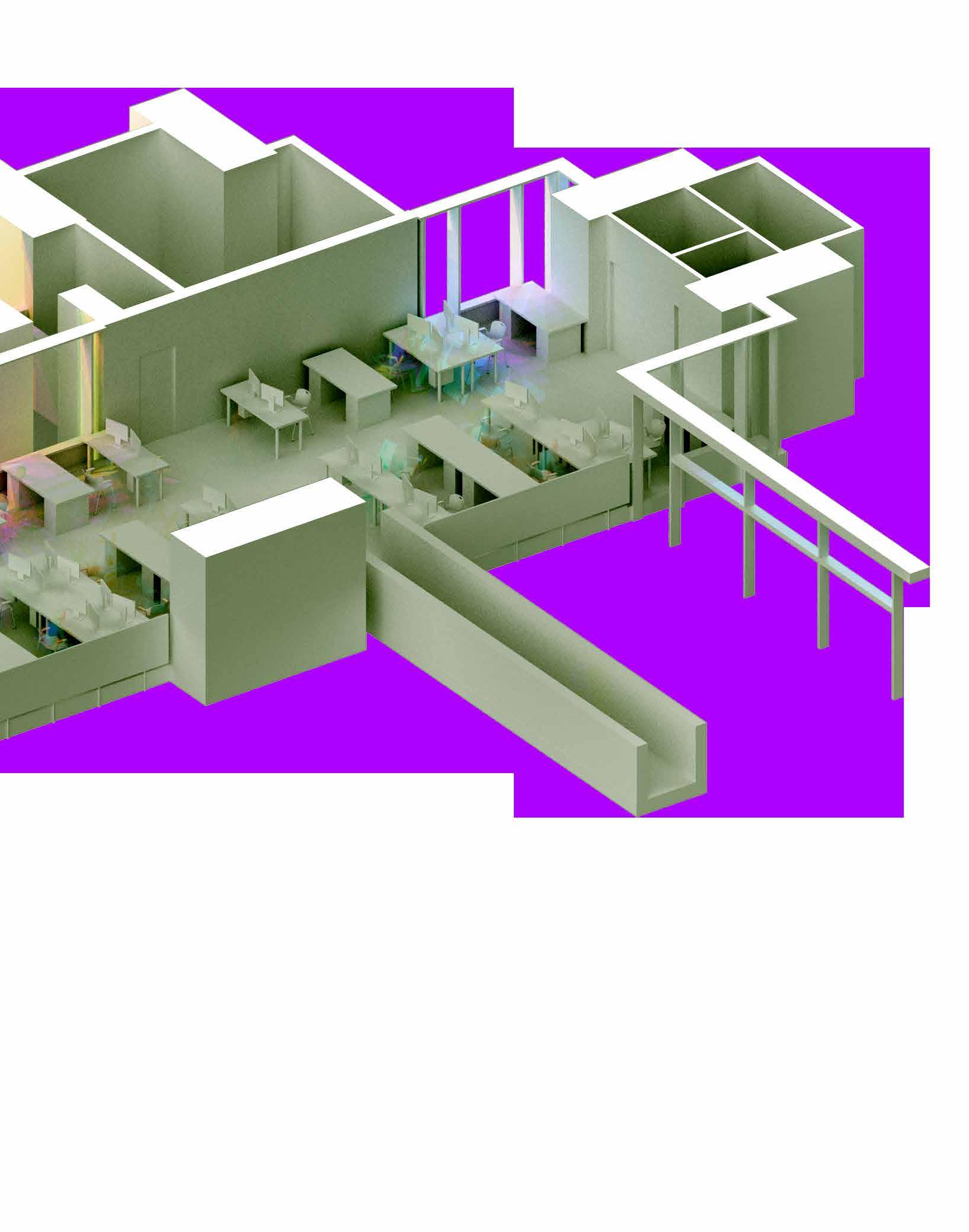

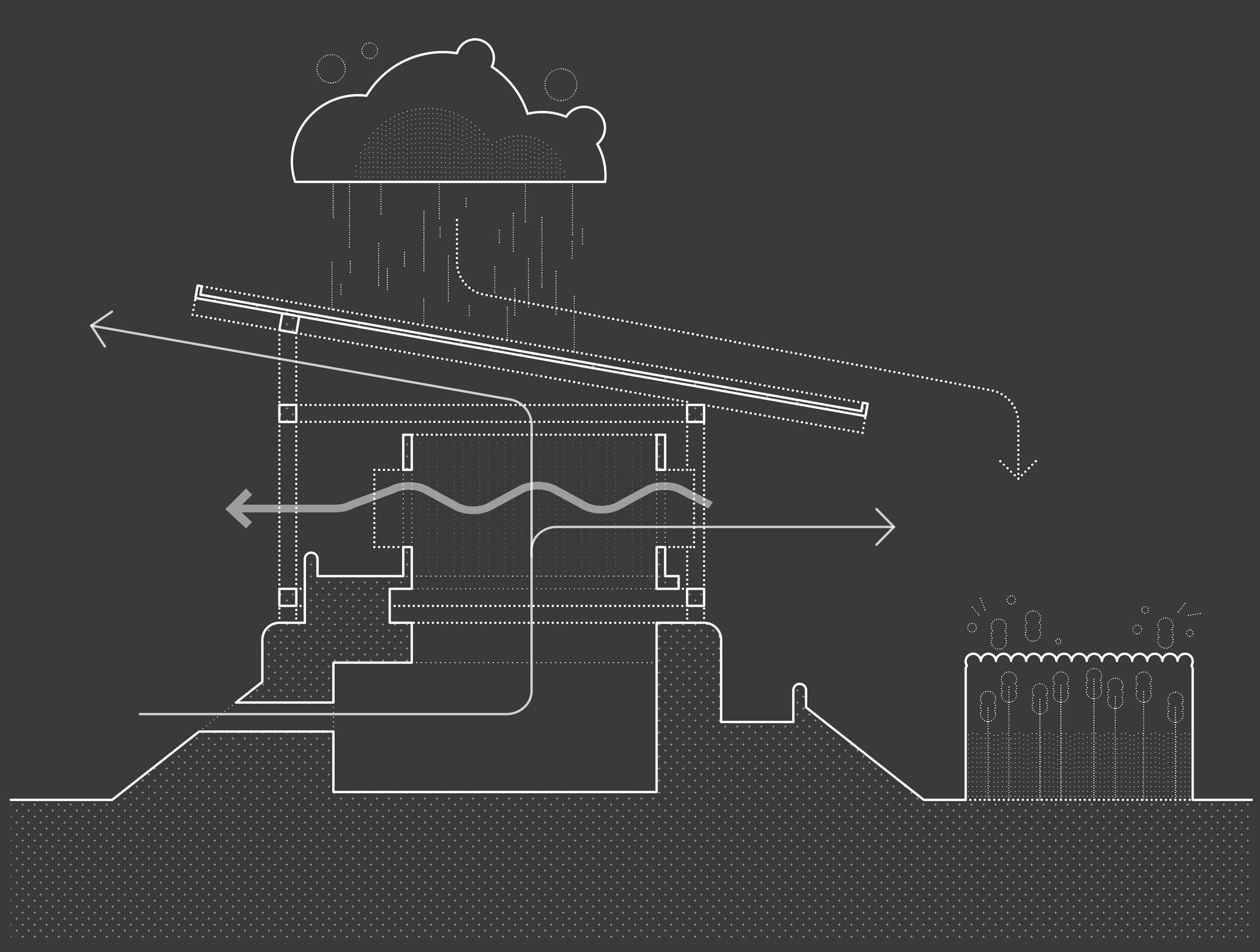

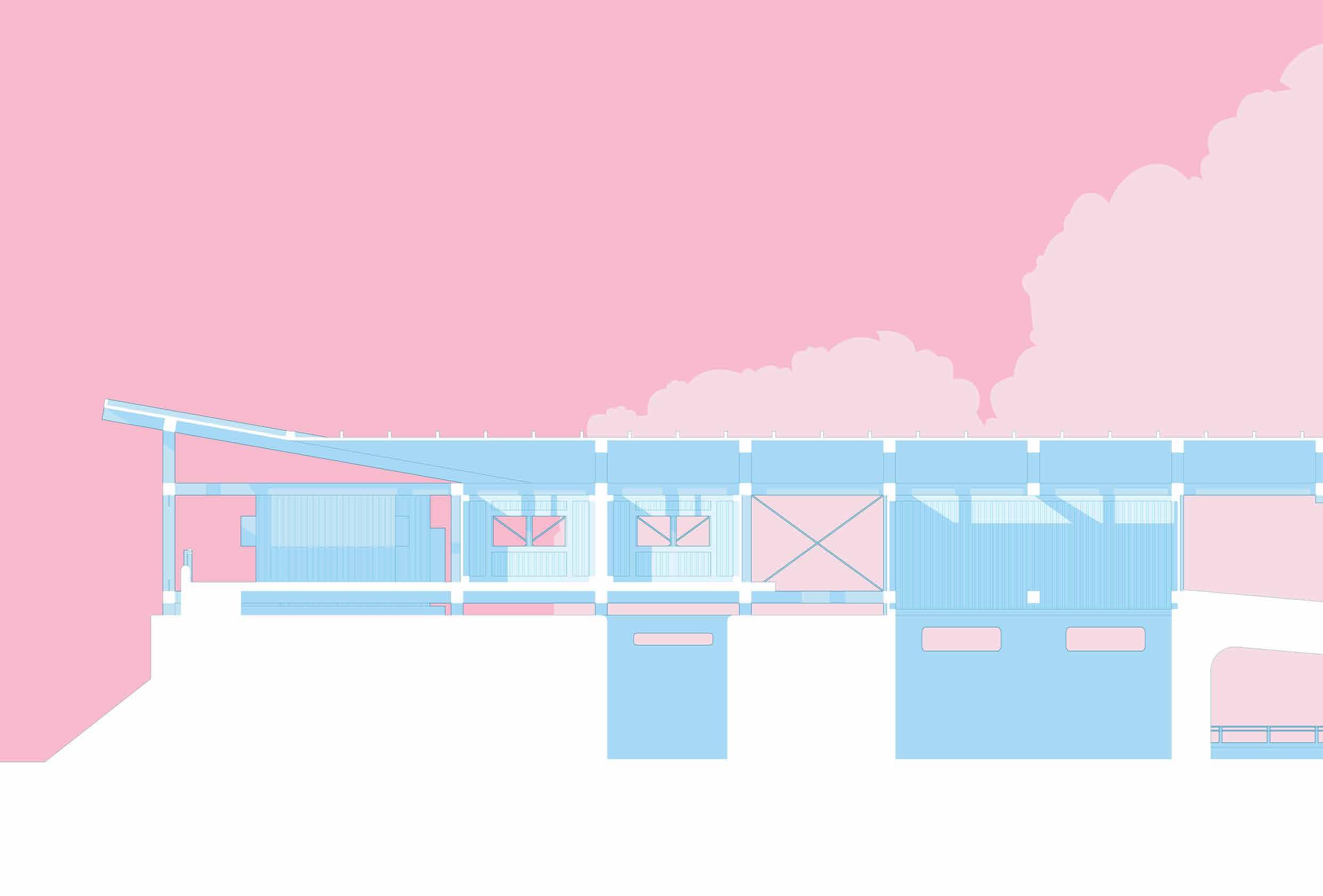

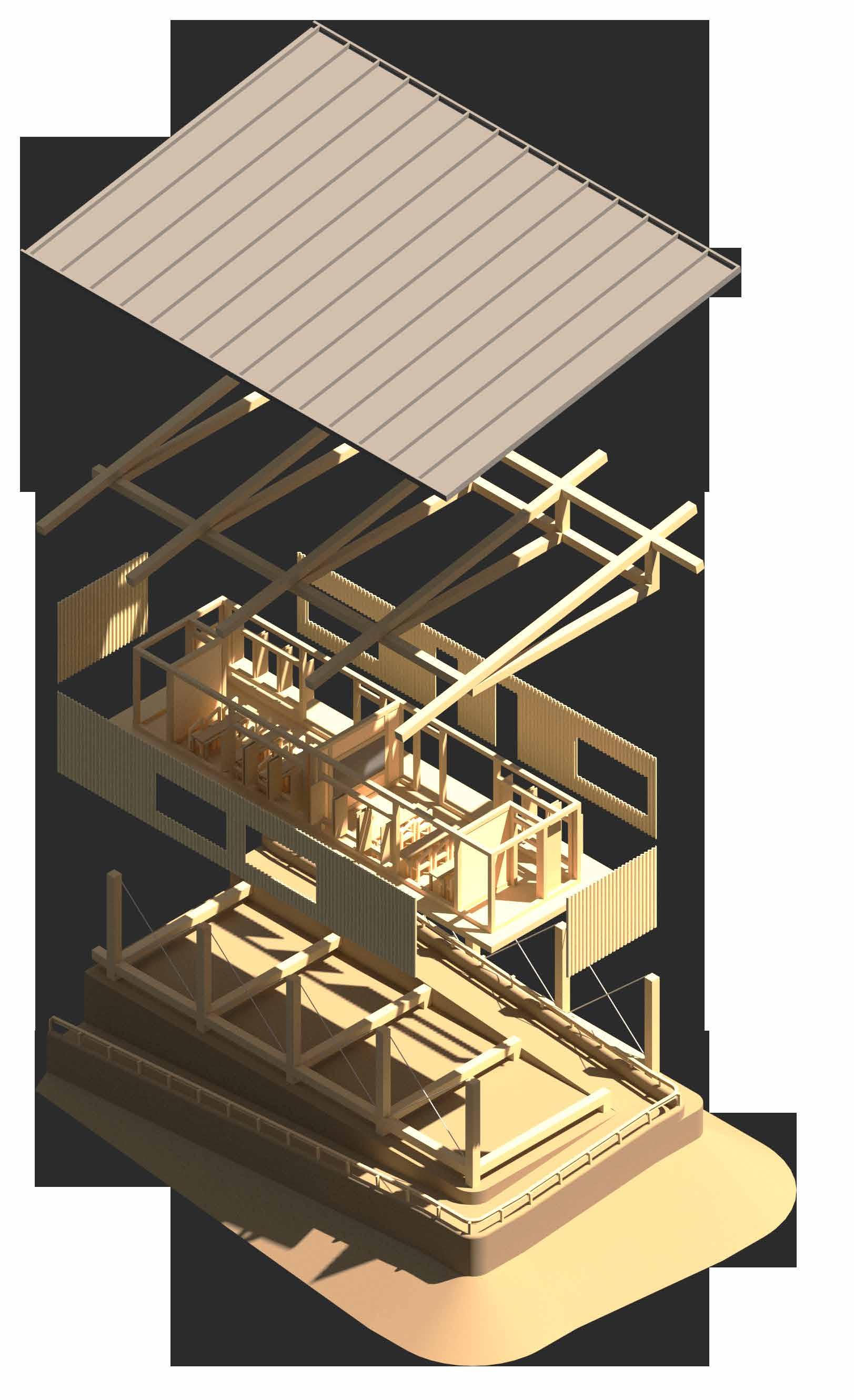

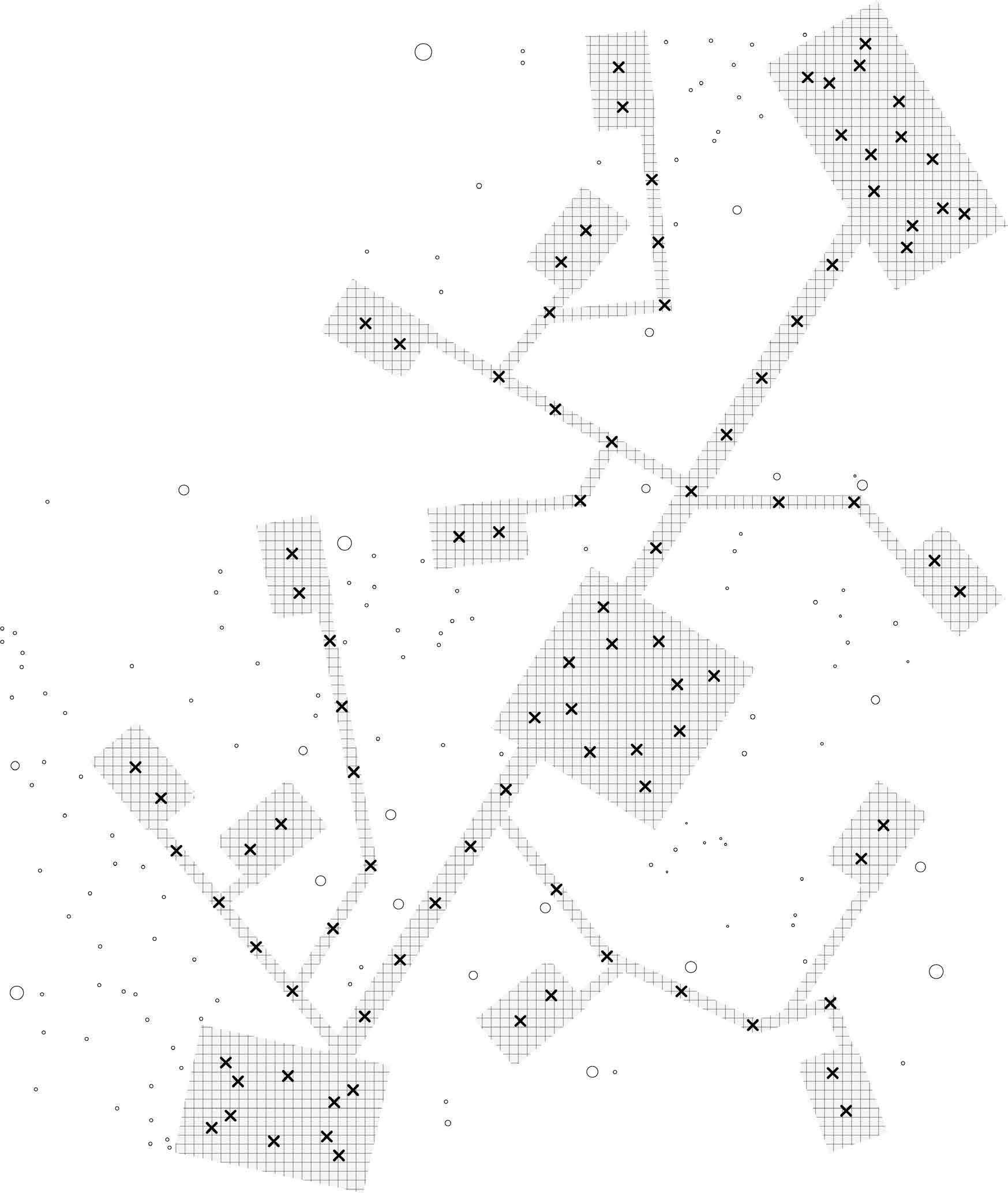

Tucked away in the agricultural district of Gaibandha, Bangladesh, this design is for a simple school building. The school embraces its large site allotment and modest spatial need by exaggerating the connections between its interior programs, spreading them out among the site to its maximum bounds.

Circulation becomes the premiere feature, the building’s favorite space. The emphasis is on the travel between places, and the way circulation can distort and distend to become its own place. Sometimes doubling as social seating or outdoor reading space or lunch tables, it defies a purely circulatory designation.

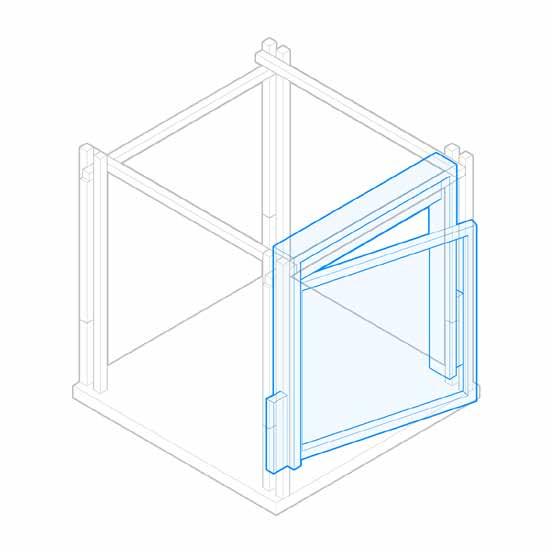

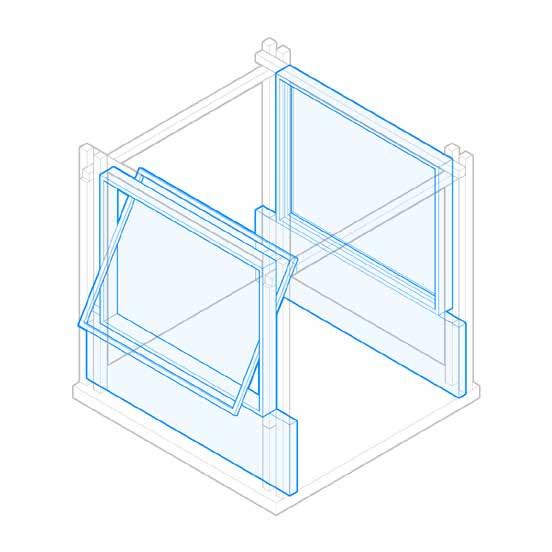

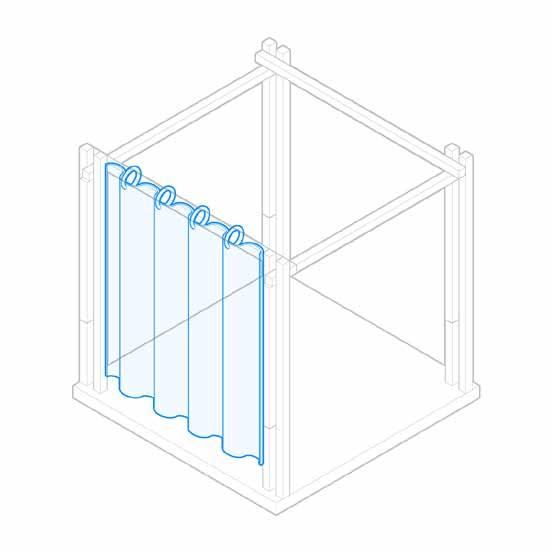

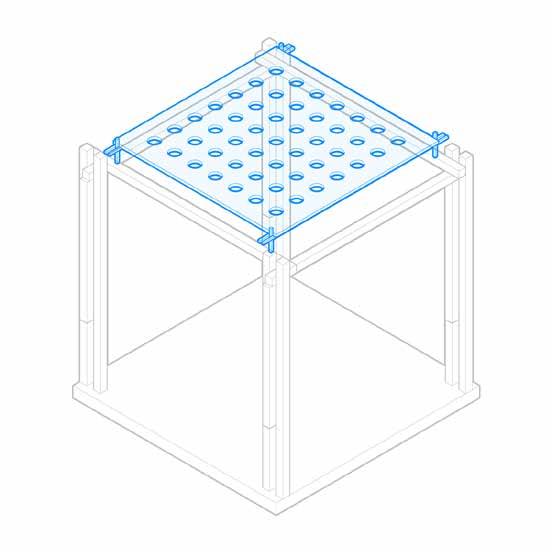

Materials for enclosure are sought out locally and used lightly, creating intimate breathable “indoor” spaces from wood and bamboo. Timber columns hold up the large, unifying roof, which directs rain away from classrooms and offices toward the growing fields in the interior courtyard.

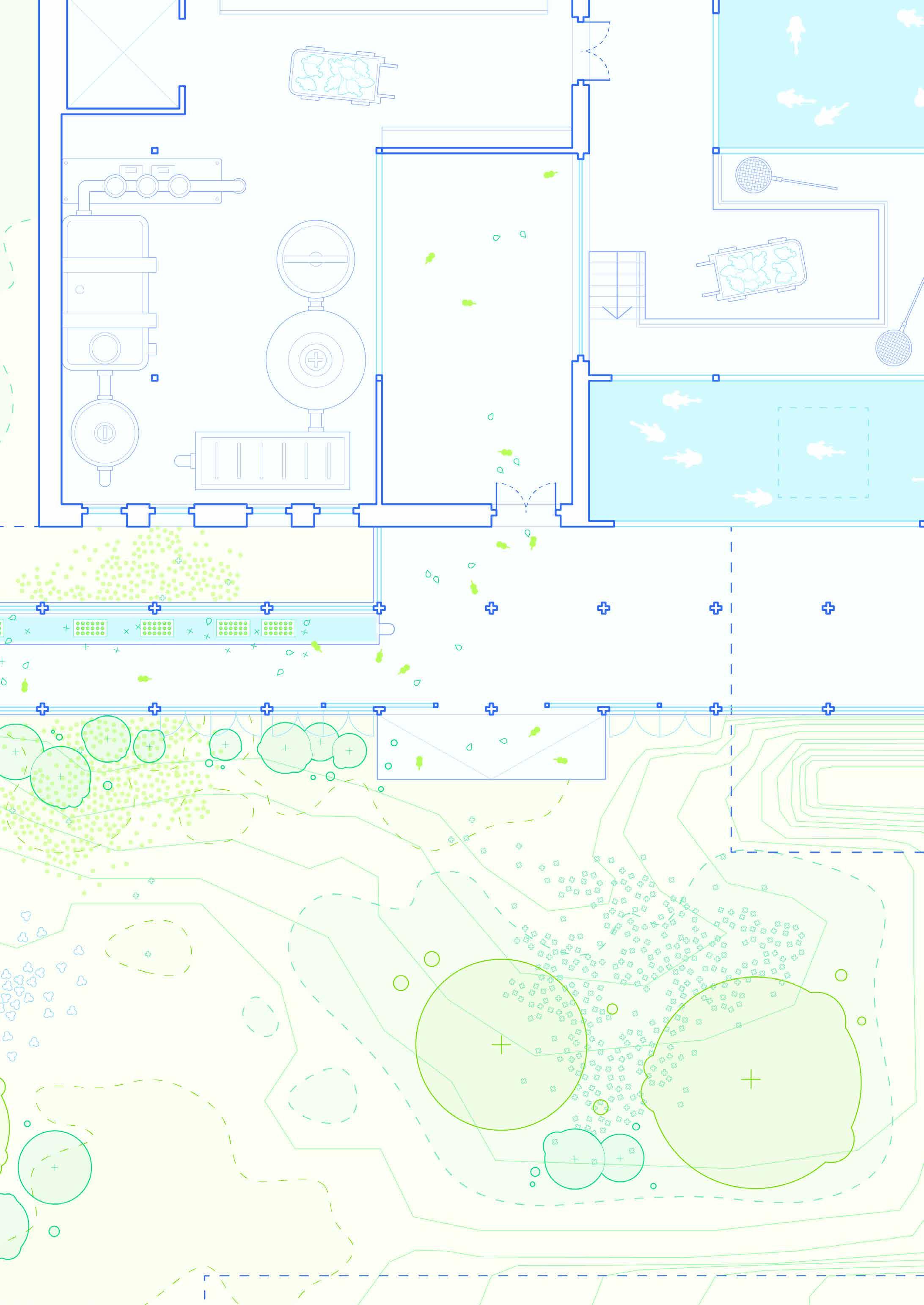

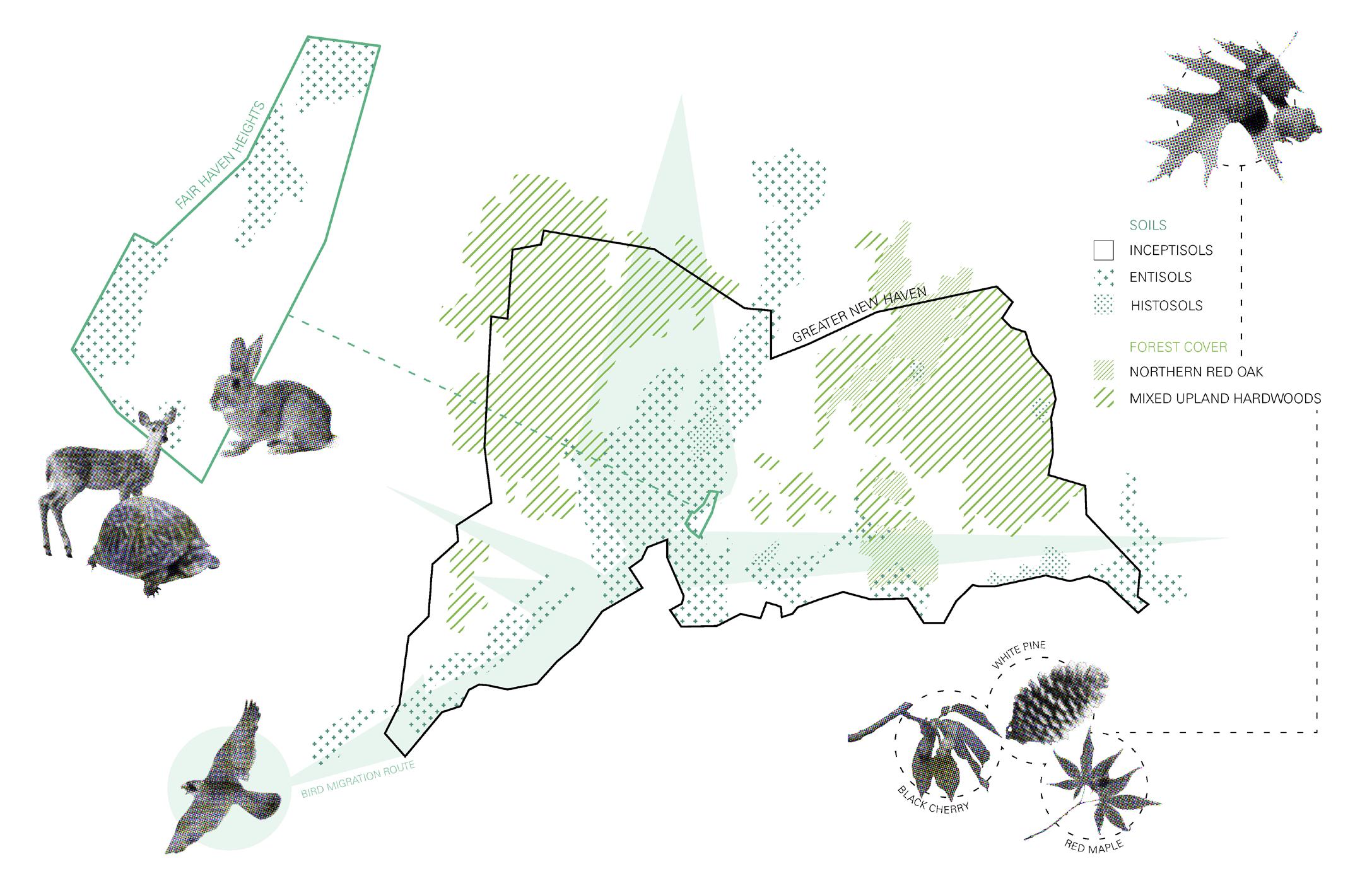

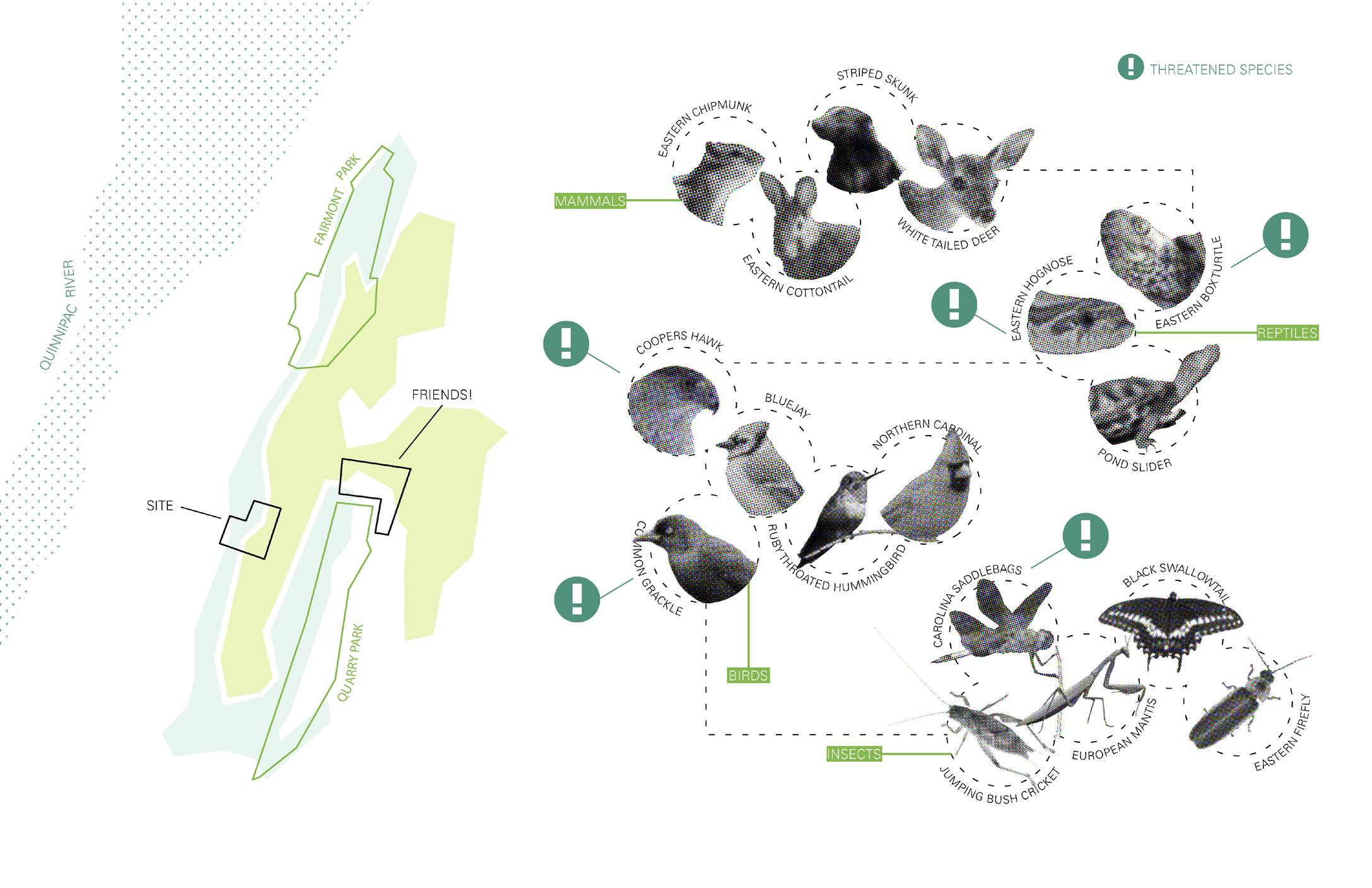

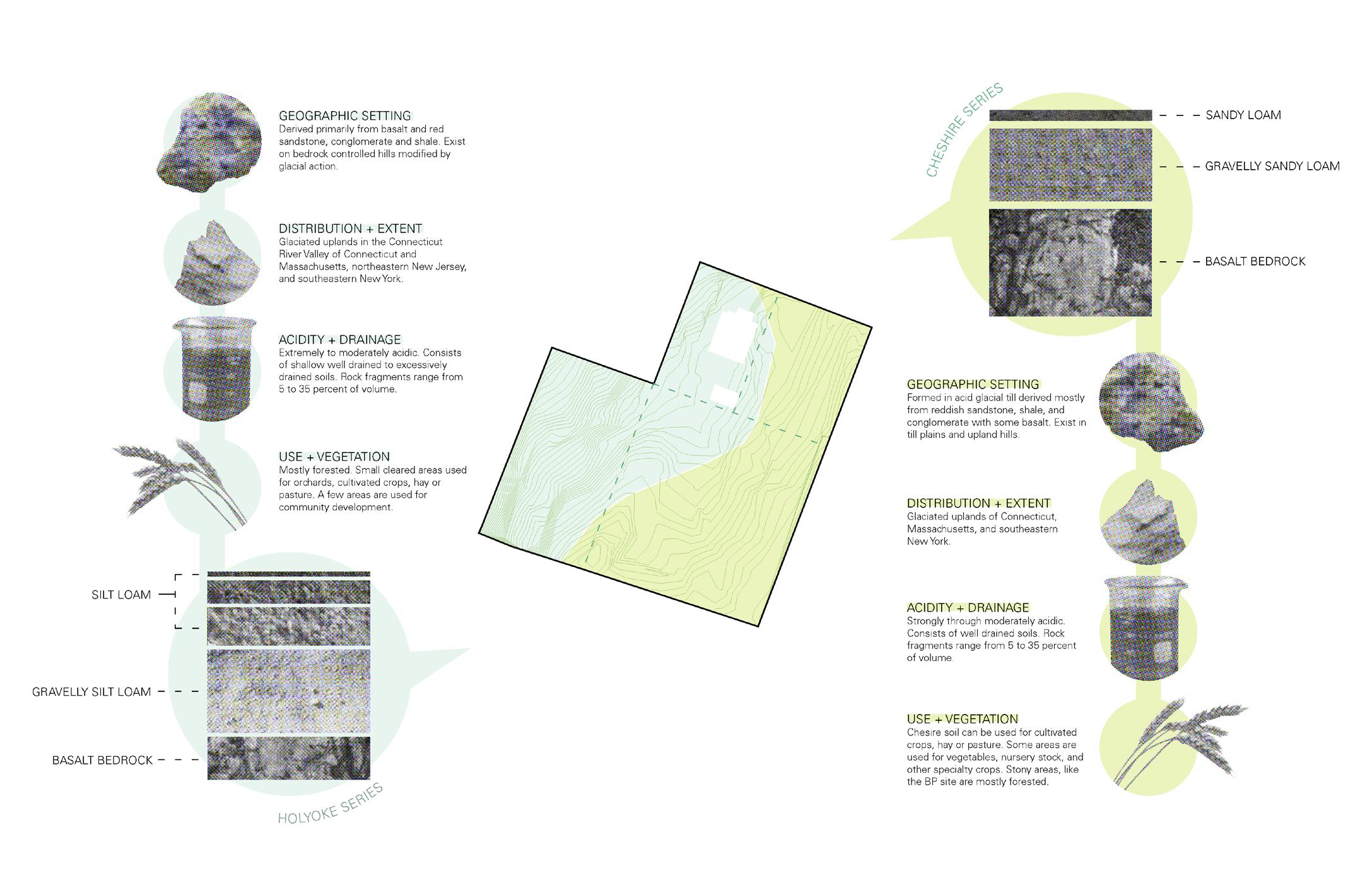

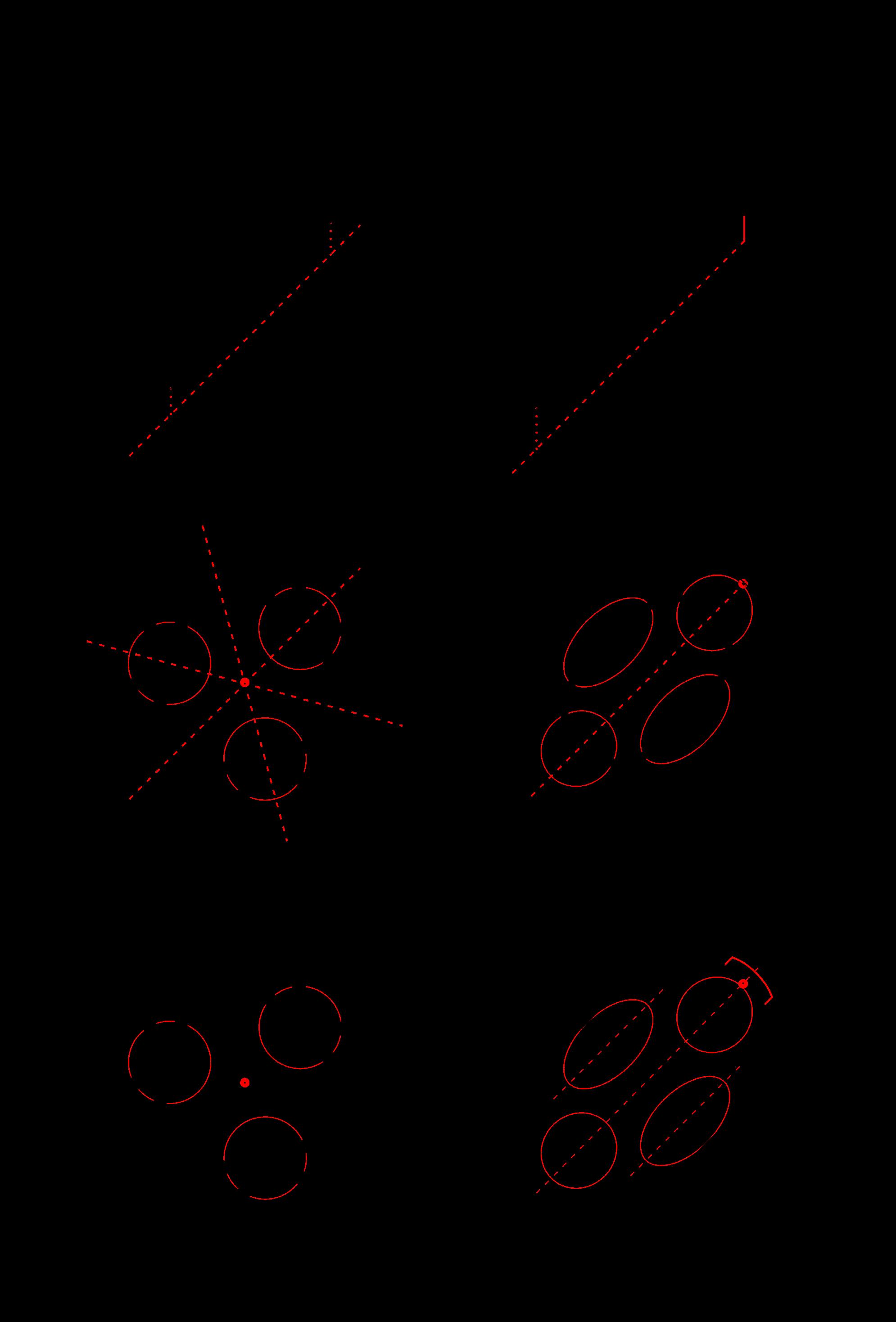

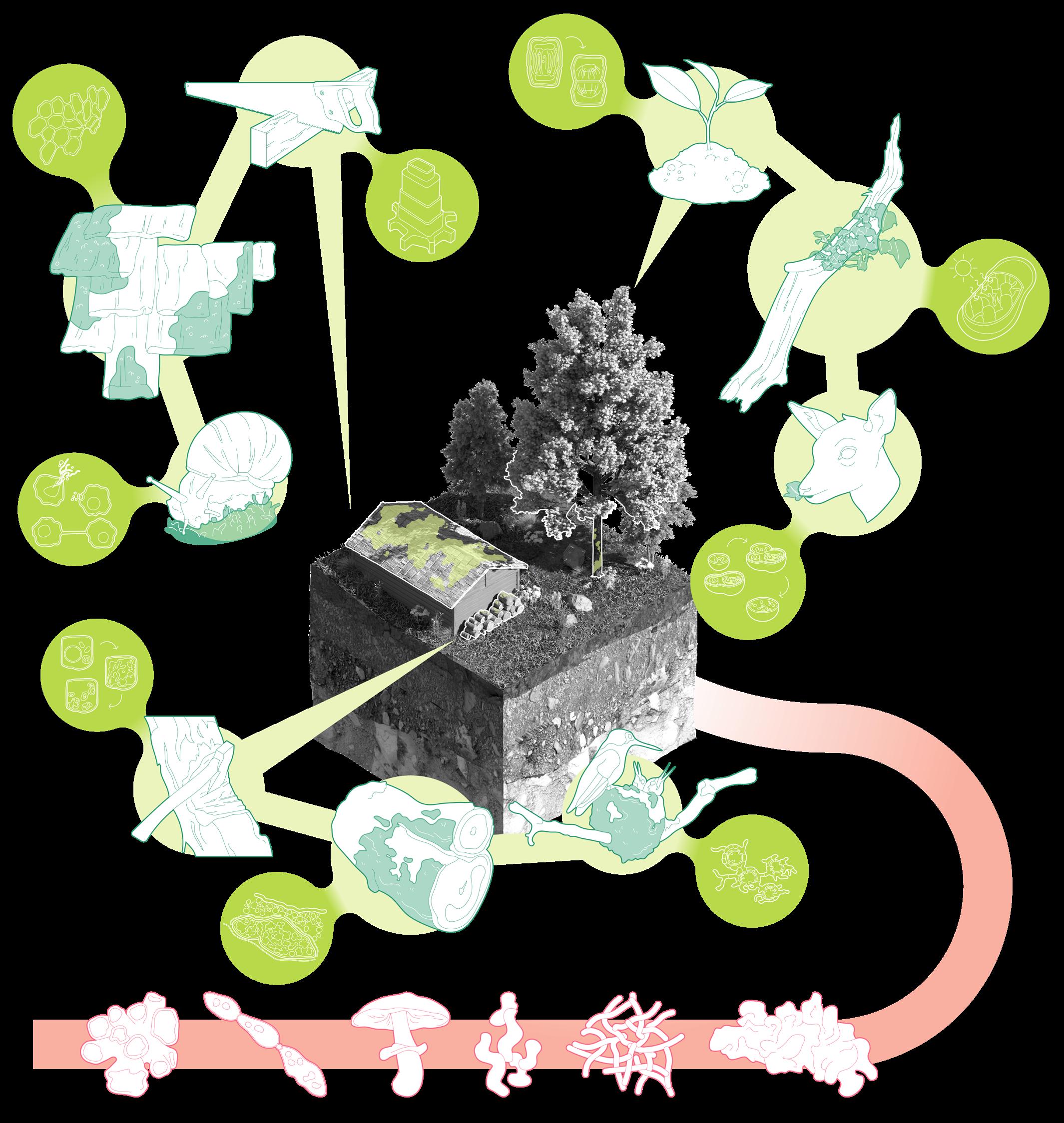

In Fair Haven Heights, Connecticut, there is a small forest making a last stand. The only remaining forested site in the neighborhood, this proposal acts somewhat in protest of the brief that created it, which asked that the site be developed for an intentional community to live on.

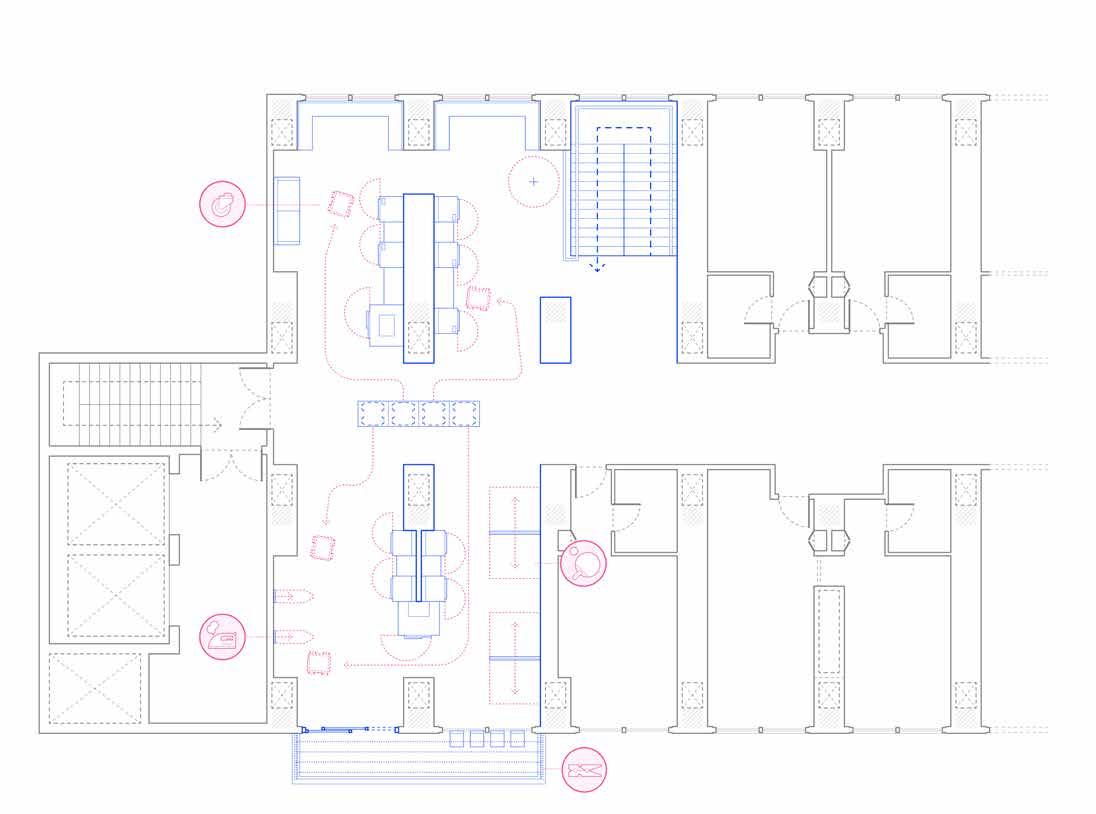

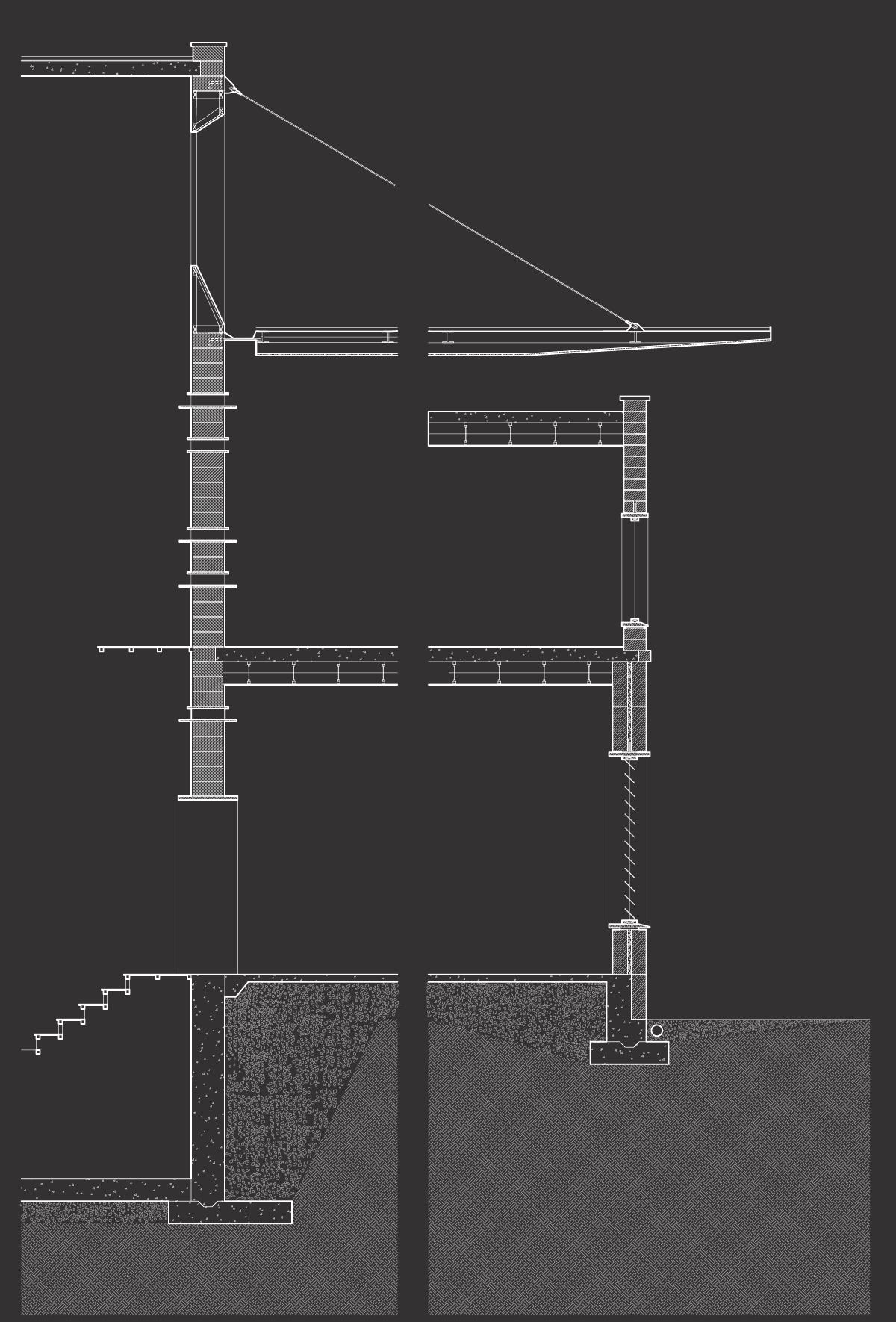

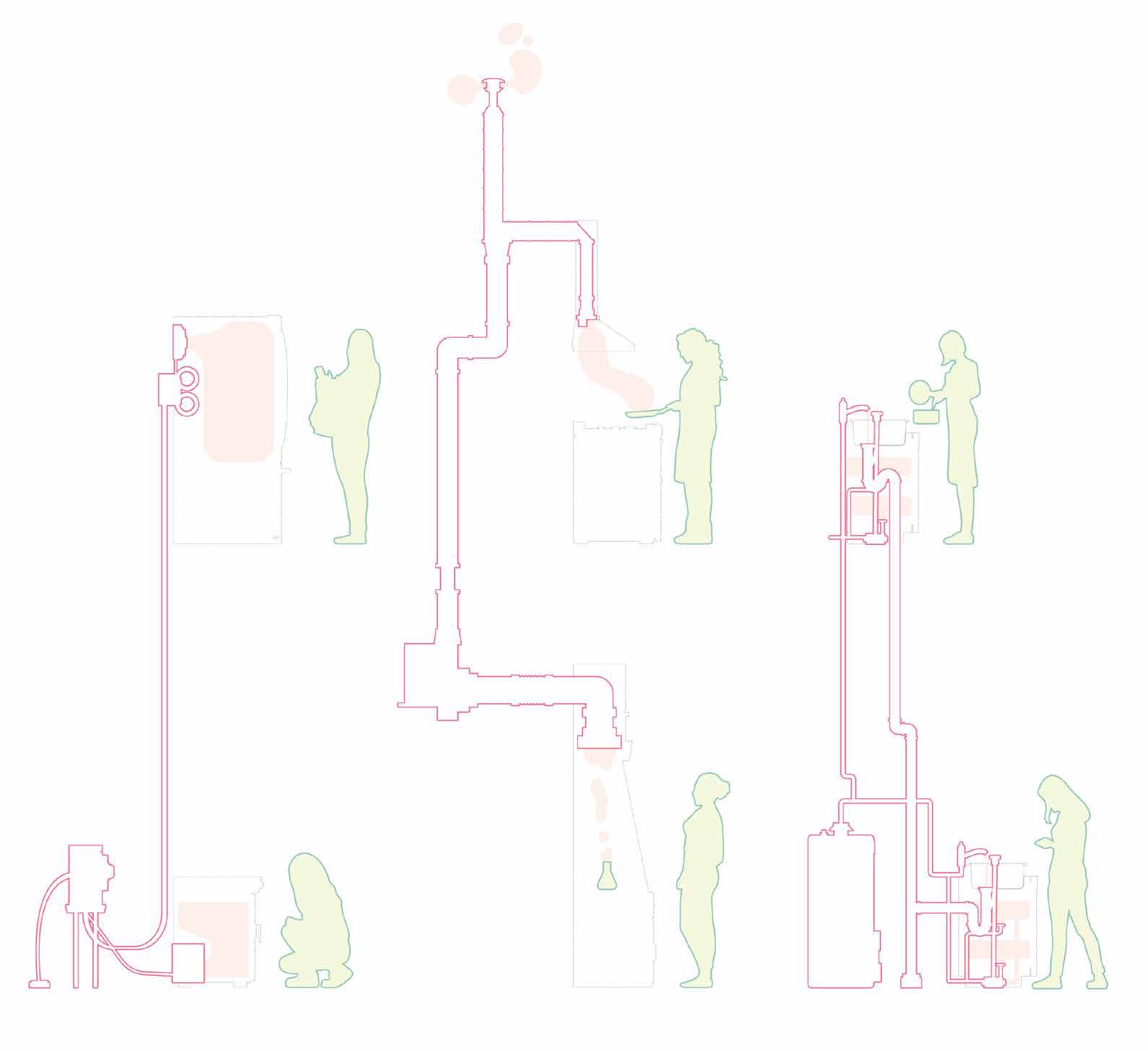

The building is imagined to be willfully impermanent, giving way to the natural processes of decay and recall which already consume many objects on site. First designed for a group of scientists (ornithologists, microbiologists, and arborists), the temporary residents will be focused on regrowing the site’s forest stronger than it was prior to their occupation of it.

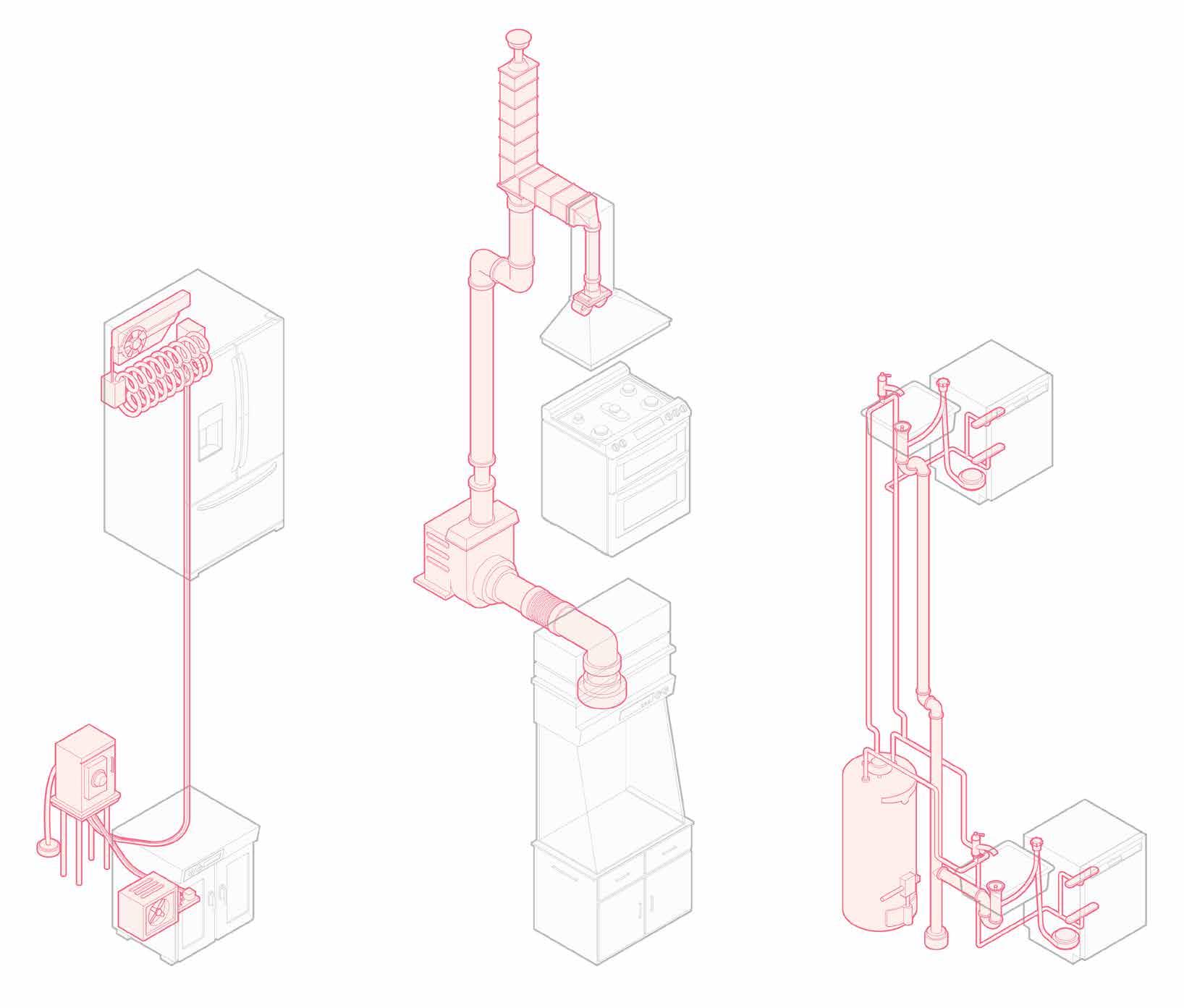

The architecture itself enforces their interests in connectivity and relationality, symbiosis and mutual care, in the way systems and organisms depend on one another. Kitchens bleed into lab space in transparent utility cores, letting the flow of air, water, and electricity move vertically between programs.

(PARTNER: BASEL HUSSEIN)

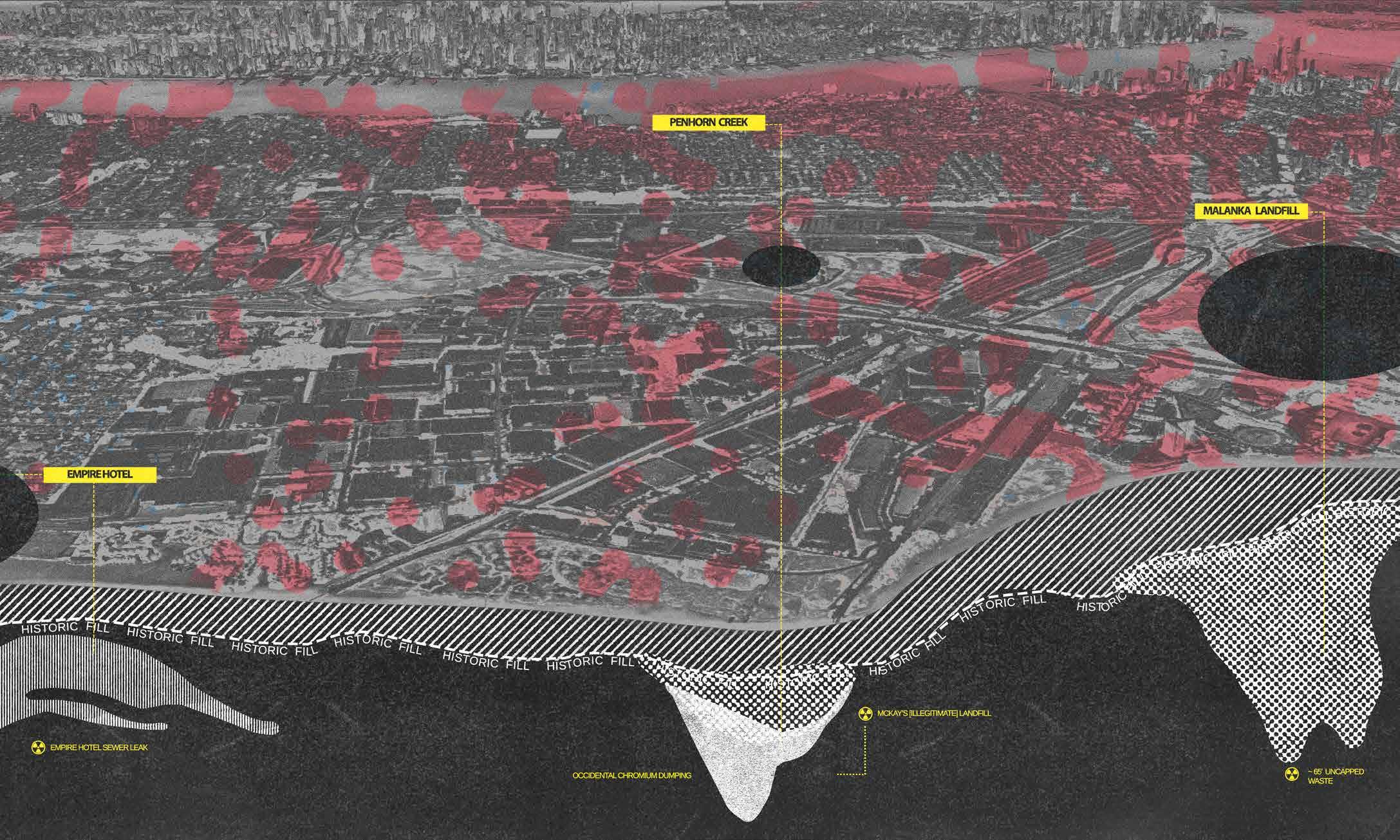

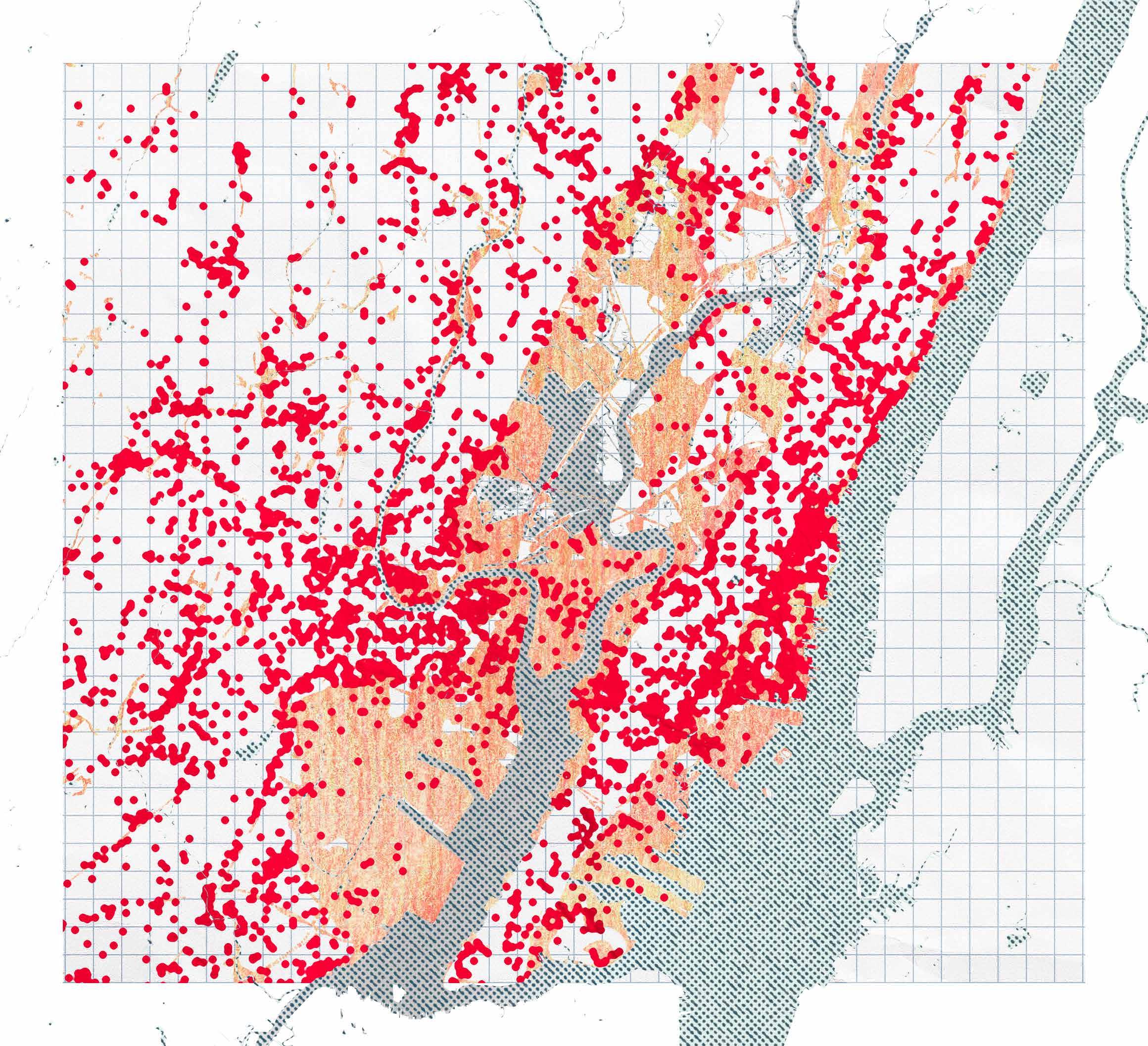

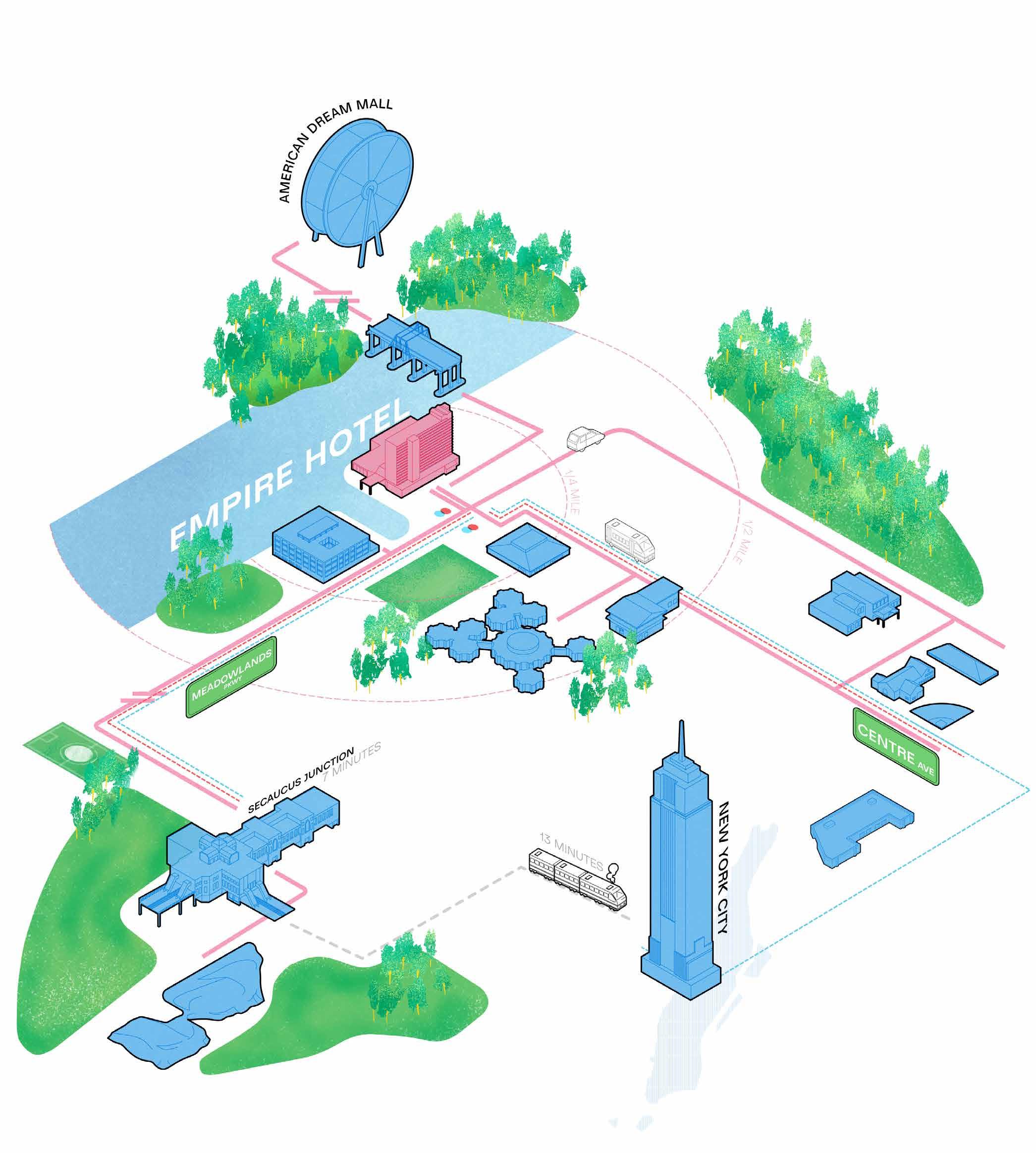

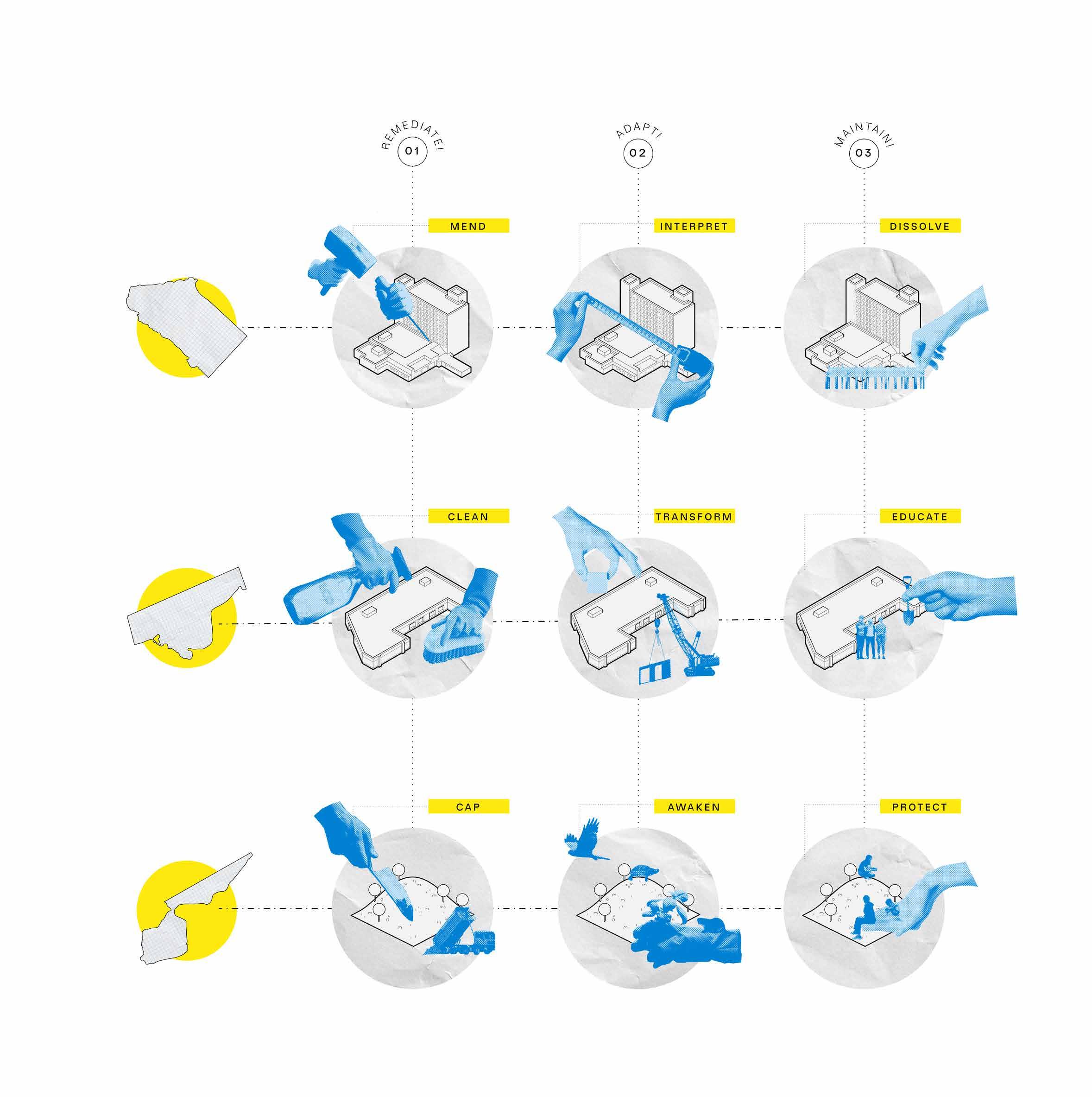

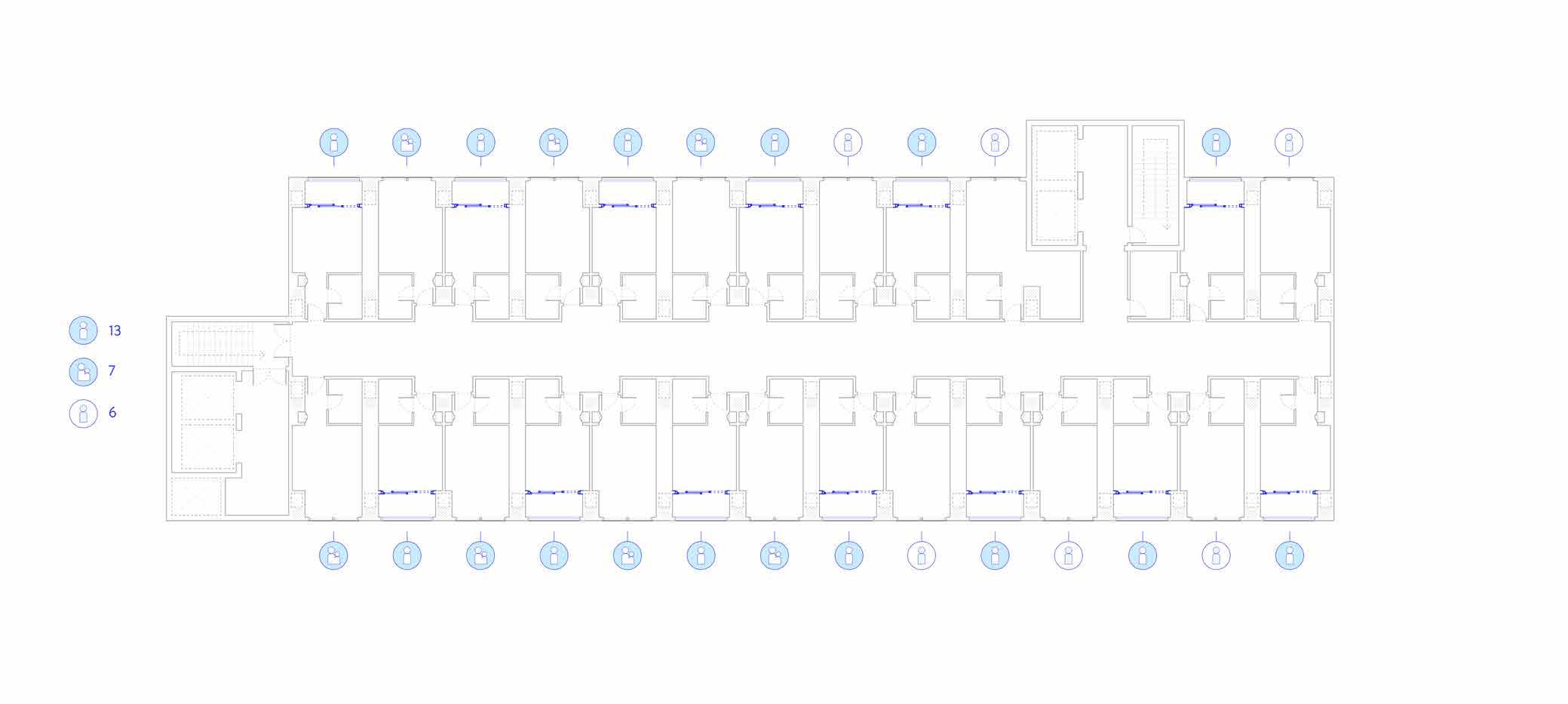

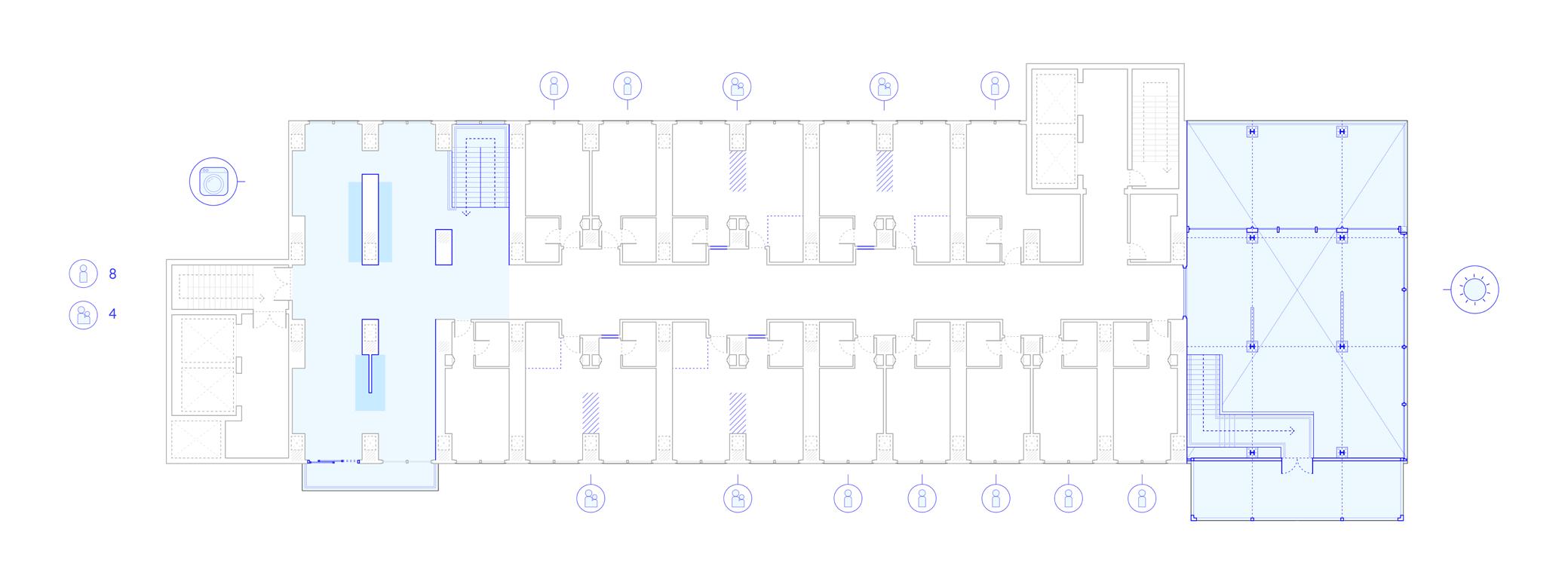

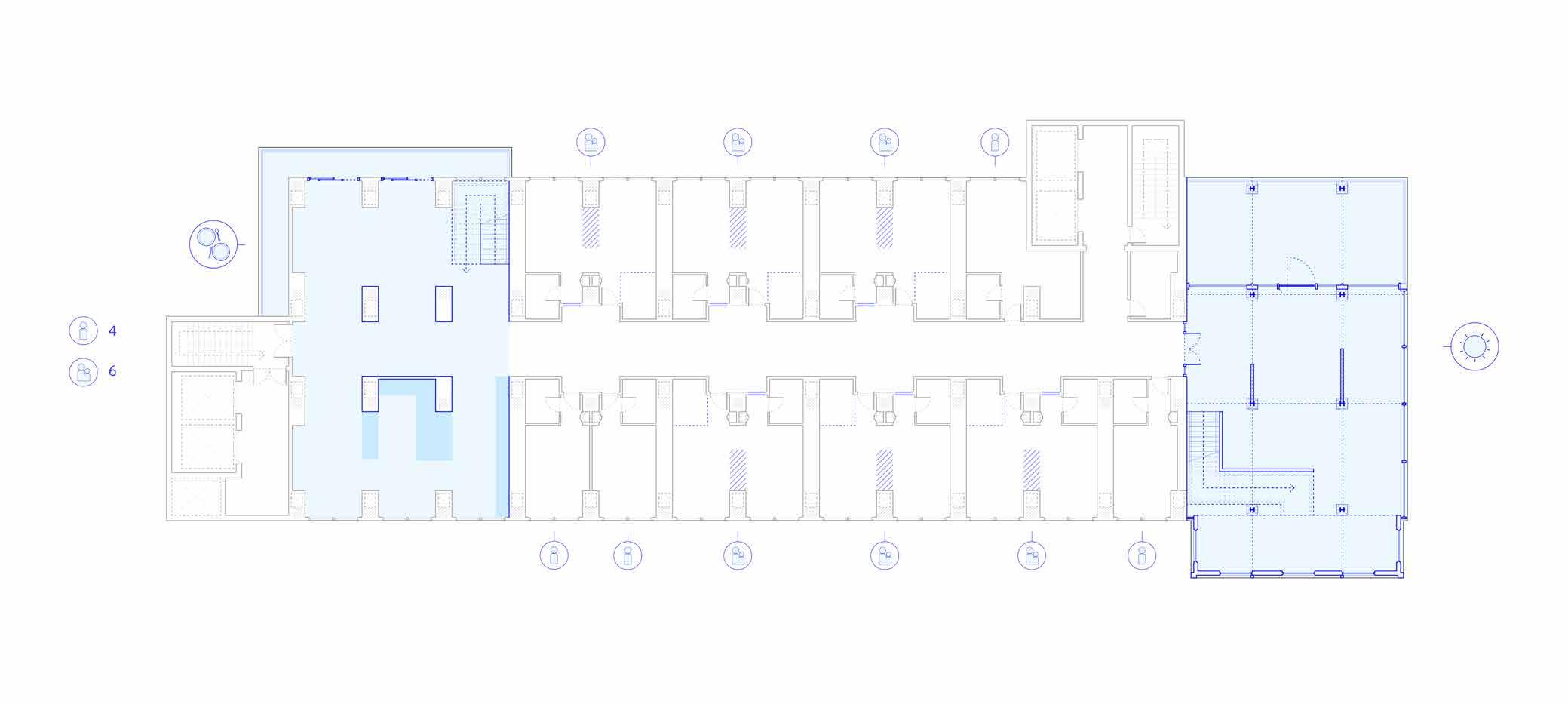

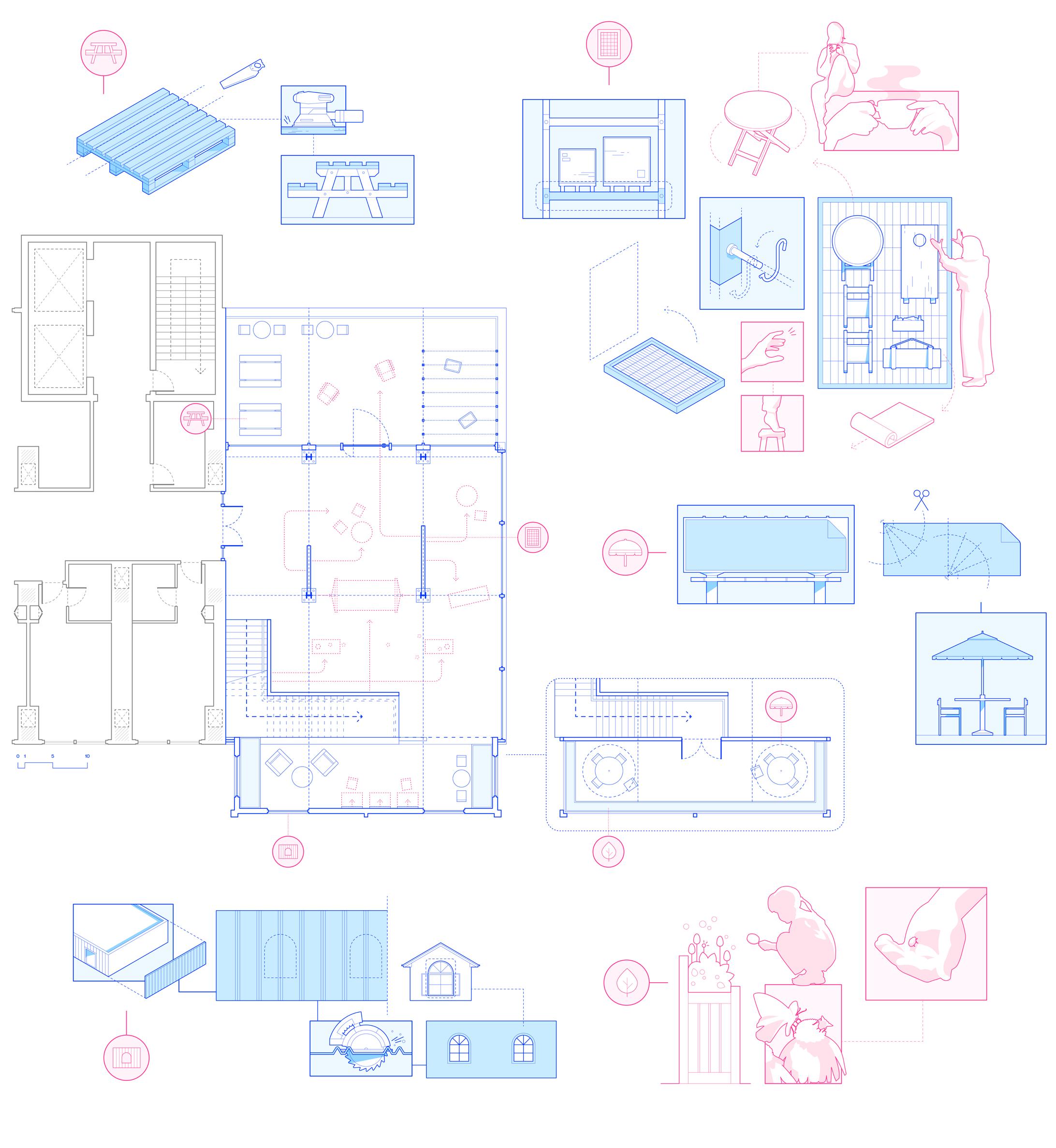

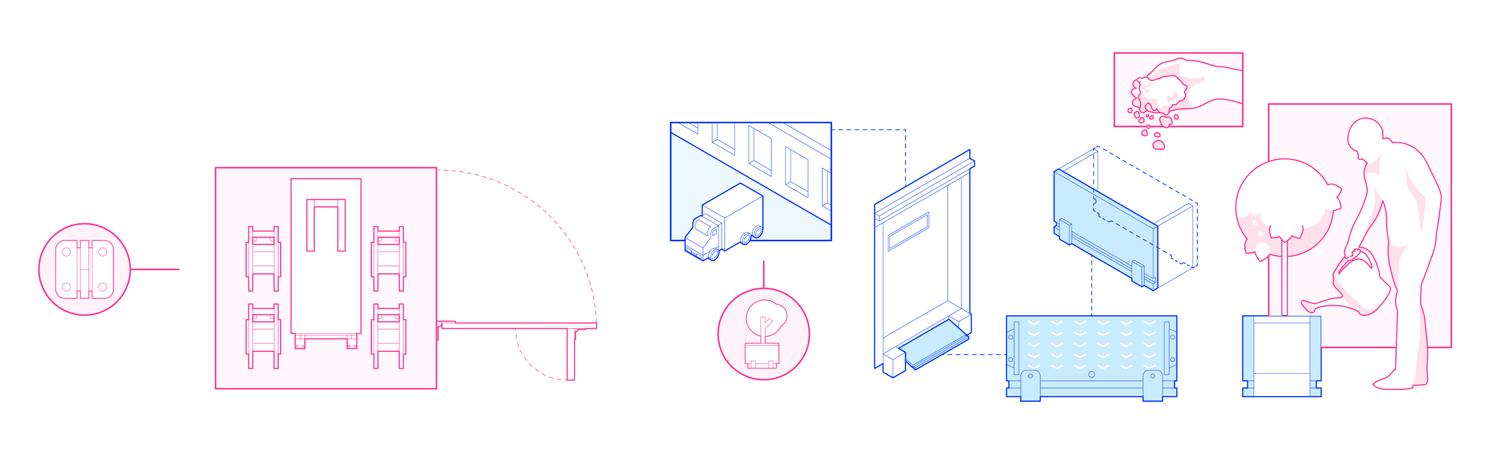

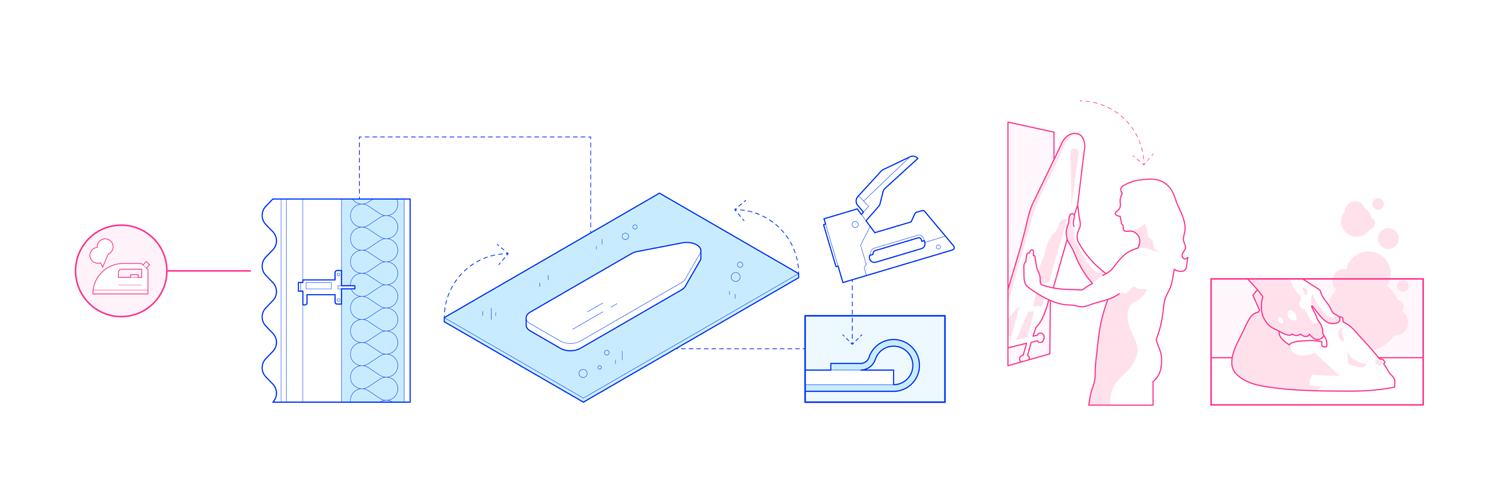

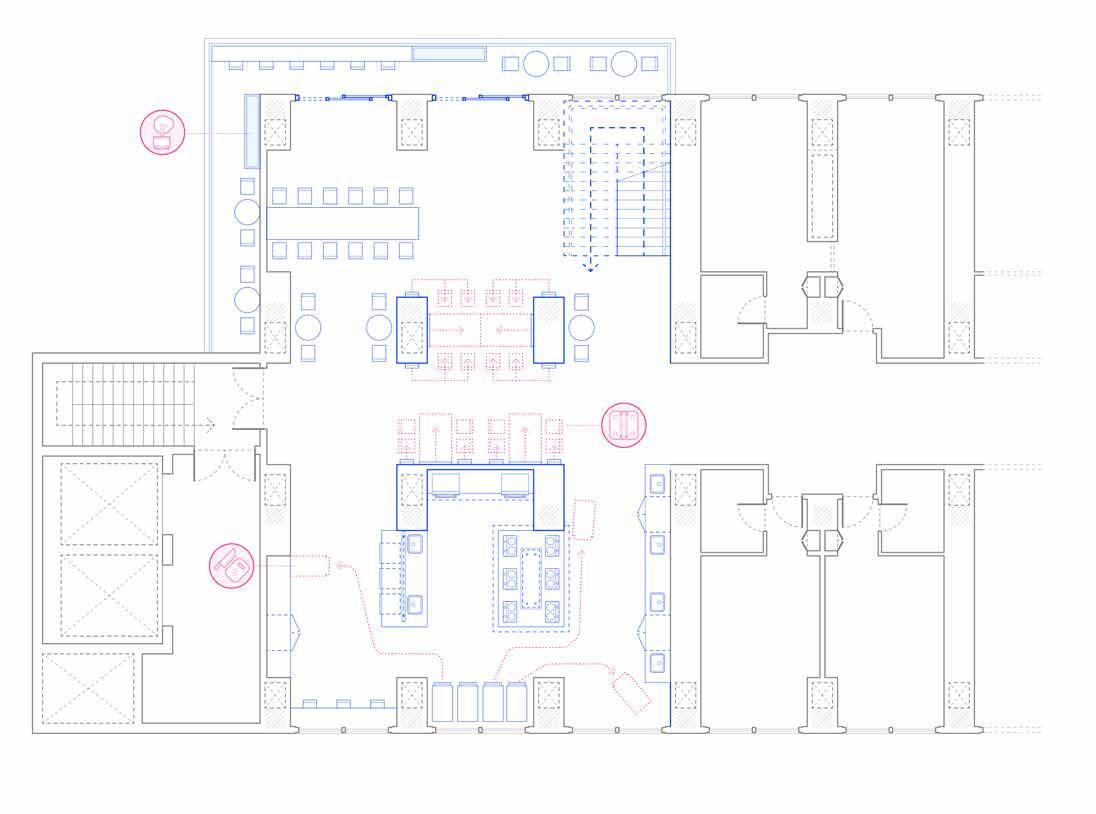

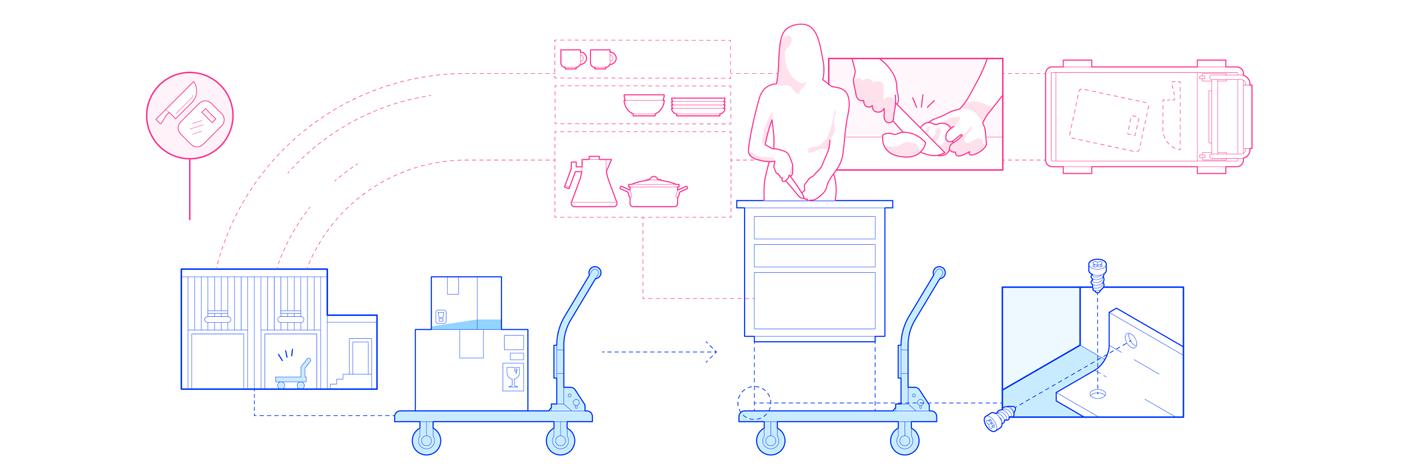

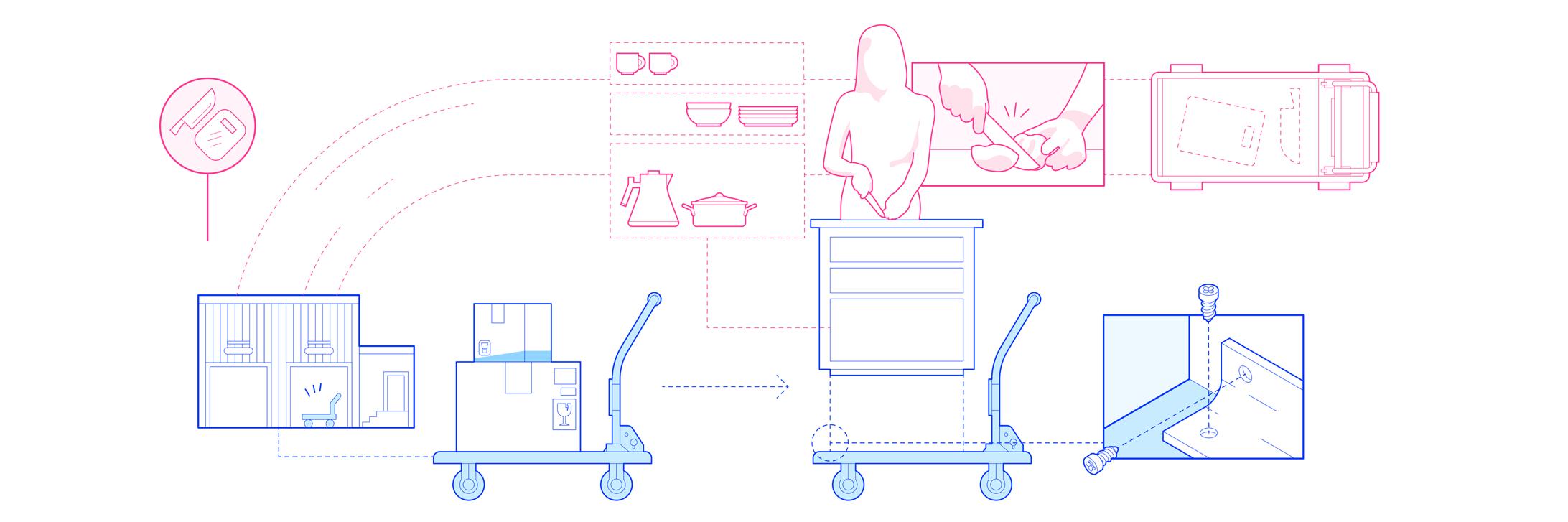

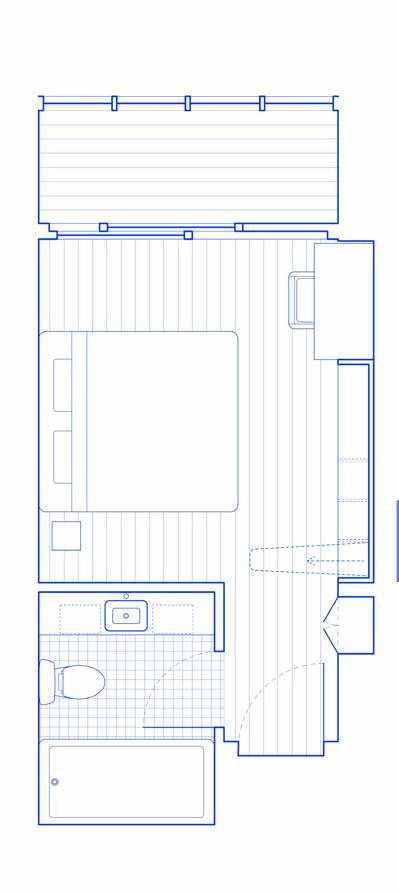

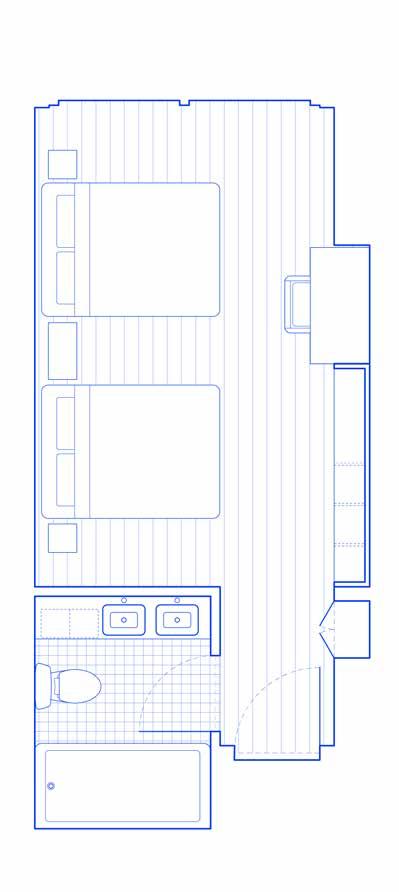

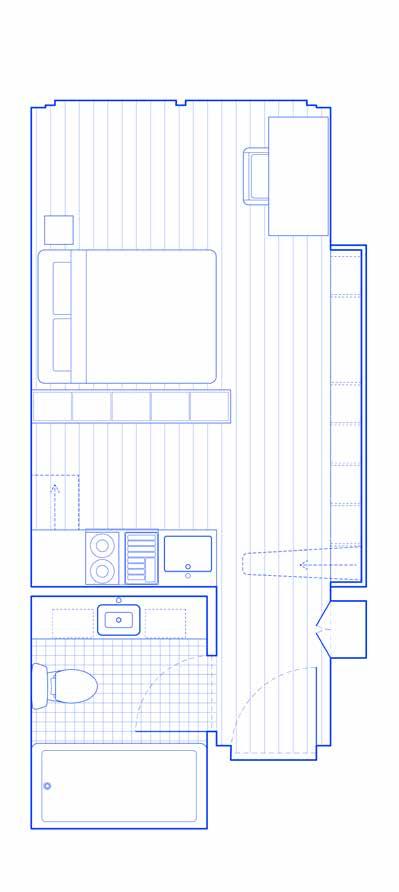

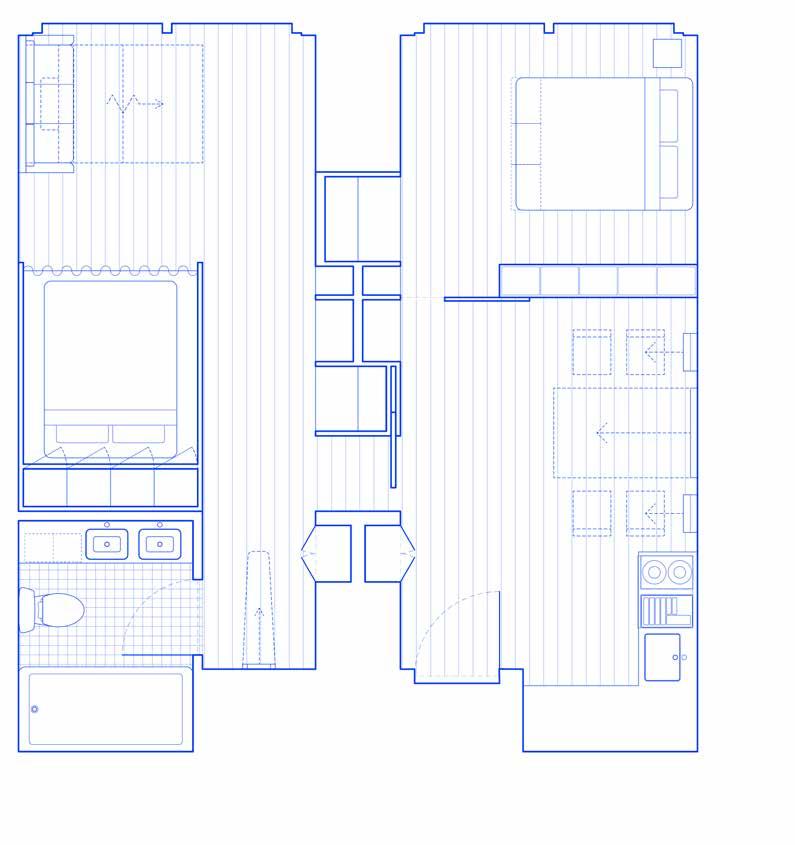

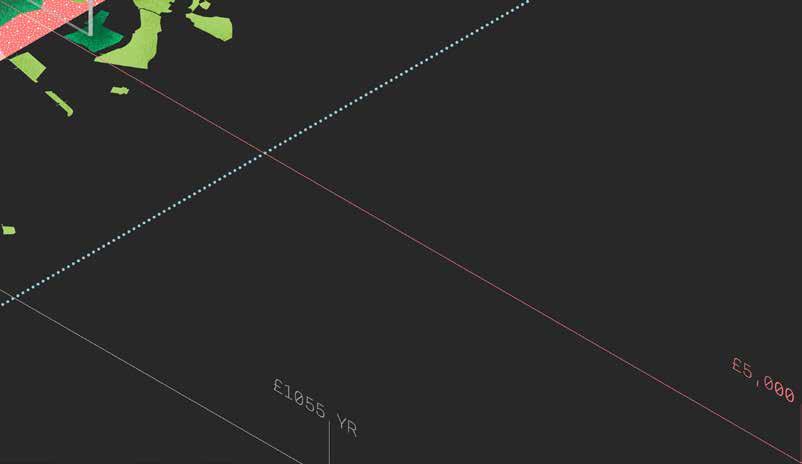

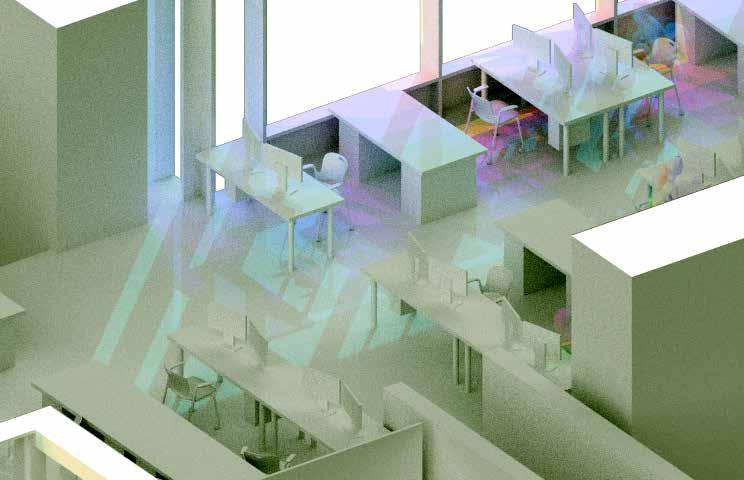

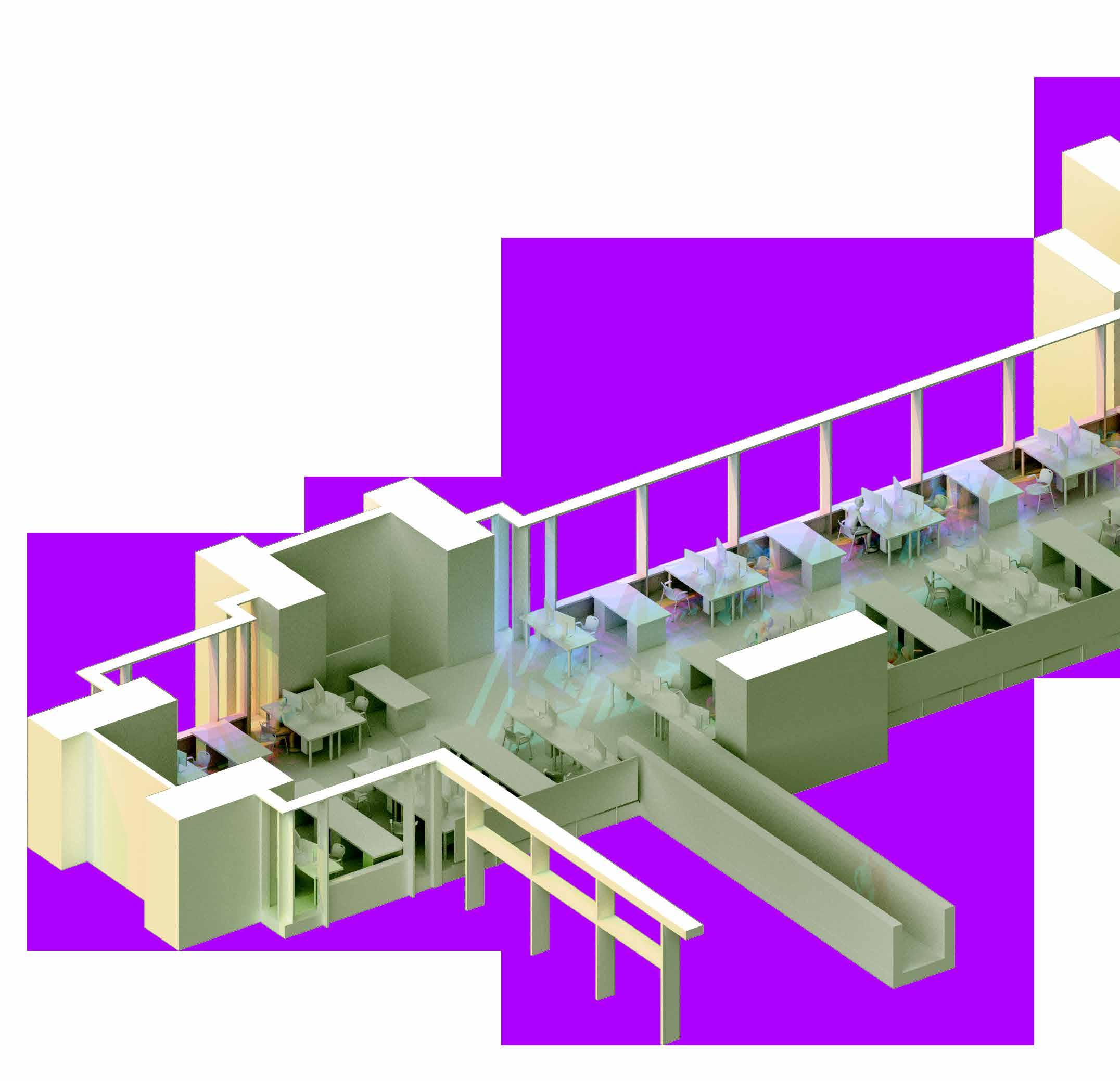

This project presents an adaptive reuse of the abandoned Empire Hotel in Secaucus, NJ. With half its suites converted into temporary affordable housing, the project acts as a polemic against the recent amendments to city building codes on temporary lodging in hotels.

At an urban scale, the housing plays a starting role in a greater pilot program meant to provide remedial services to New Jersey’s brownfields. It will serve as housing for a new environmental workforce, creating jobs through federal grants and the administrative support of environmental N.G.O.s.

The environmental focus of the hotel’s occupants is carried through the architectural expression of its renovation. Drawing on the ‘field’ of abandoned and disused warehouses in the city, furniture and facade alike are fashioned out of the ejected scraps of the warehouse landscape. Working with a coalition of clients at all scales, the project looks to the task of housing people and healing land not as mutually exclusive processes, but as shared program.