11 minute read

Mental Math of a Recovering Skeptic Erin Aslami

occur? We are thus dragged into the dangers of carte blanche: that pernicious strain of solipsism that arises out of a complete abandonment of the possibility of fxed truth. Ultimately, Erin demonstrates to us the way that relativism as a plurality of perspectives is itself productive of reality — that communication creates pathways out of that which appears undefned, that meaning arises only out of deliberate and shared work.

Carte blanche also contains a sense of loss. Something has been wiped away in order to create it: every new world arrives only after the dismantling of the previous. Thomas Mar Wee in “On the Ethics of Memory” will argue that no future-oriented work is unburdened from the past. Rather, we are ethically charged with bringing this past — its tragedy, its violence--with us into the new worlds we make. In this way, Thomas forces a confrontation of the rhetoric of carte blanche with historicity and mnemonics, offering refection on the ways that we can and should resist the narrative of the blank page.

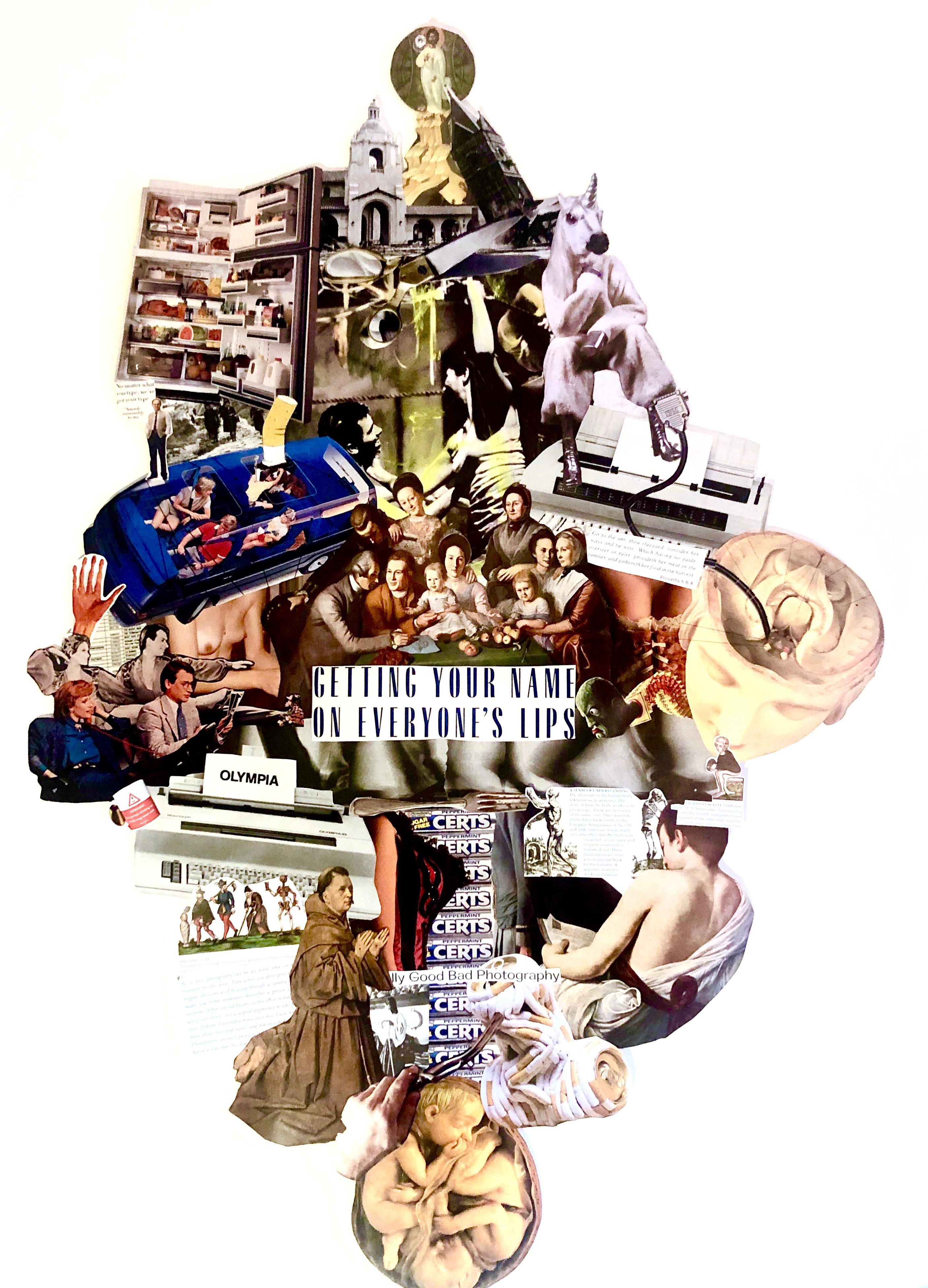

Advertisement

We then shift gears to another aspect of carte blanche: the way it responds to possibility and to virtuality, the way it allows us to navigate the varied and tenuous modes of the real. We ask ourselves: what is possible space, possible action? What is the virtual? How do we oppose these categories to that which is physical, or tangible? And what work can we do in the gaps in-between?

Ezequiel González offers a response in “Bodies on the Line,” where he uses both an exploration of instagram and refned psychoanalytic work to describe the “cyber-melancholic turn” enacted upon the digital body, which is generative of a “cyber playof-self”. Rishi Chhapolia’s interview with philosopher of mind and cognitive scientist David Chalmers continues this line of investigation, offering remarkable insight into problems of consciousness, ethics and AI, and the future of virtual reality. Finally, Matthew Harper’s “Freedom of the Present Moment” guides us through possible worlds theory and deposits us frmly at the present as an escape from the trappings of temporal anxiety.

What actually activates the dormant potential of the carte blanche is, of course, this ‘writing in.’ We must, then, look to language: to the way that inscription upon the blank surface transforms it, actualizes it, puts it to work; but also to the way that lan guage elides this fxity, oozes out of its own set regions of meaning.

In “Mathematics as a Language,” Aiden Sagerman displays his own triumphant carte blanche within the academy, offering an argument for approaching mathematics as a coherent linguistic structure so compelling it was accepted by Columbia’s Institute for Comparative Literature and Society. Contrarily, as opposed to arguing for what a language is, Mira Ward demonstrates the ways language slips out of its own boundaries in “Dissolution as Literary Genius.” Using both Elena Ferrante’s novels and her general cultural phenomenality, Mira embarks on questions of anonymity, identity, and the moments of slippage between the two.

Finally, Emma James plays us out with “False Freedom and a Forgotten Feminine,” in which she uses personal narrative to explore her own interactions with and ruminations upon carte blanche while living ‘on the road’. Juxtaposing lived experience with Kerouac’s famous text, Emma challenges us to consider the type of freedom we see the road as offering, the ways this has been commodifed, and what we can do about it. Her solution, ultimately, is to embrace a radical ‘freedom with’ which outpaces outdated and antisocial approaches to liberty such as the ‘freedom from’ or the ‘freedom to’.

It is this note that we would like to end on—the idea of community, of ‘freedom with,’ and of its antidotal properties to both philosophical and social or ethical woes.

It has been a challenging year. We at Gadfy have been truly moved by the continued enthusiasm for our work, even while occurring entirely online. We have been immensely fortunate to have added invaluable members to our editorial board this year —many of whom are freshmen, who chose to begin their college journey and include us in it at such an anxiety-inducing time as this. We would also like to seriously commend all of our contributors for having produced such thoughtful pieces of writing at a time when writing and research feels so very hard to do. It is our sincere hope that readers of this issue will, even more so than entering deep into philosophical contemplation, feel the warmth of a network of young thinkers who are asking vital questions and answering them in creative and collaborative ways, in spite of all current circumstances.

MENTAL MATH OF A RECOVERING

MENTAL MATH OF A Erin Aslami RECOVERING SKEPTIC

Magic is nothing less than perspective. What else can we call a refreshing arrangement of reality, a twist to refocus our vision of our world? Makeovers are magic; JeanPaul Sartre in Sketch for a Theory of the Emotions elevates transformative concepts such as remorse and ownership to magic. There is no thing that a thing is because of magic. Yet, magic harbors a foundational dependence on non-magical reality. I had always considered the realms of the magic and the mundane to be of separate natures. Perhaps they tracked and mapped onto each other, the magic embroidered into the mundane with a bright red thread. However, with magic defned in direct relation to the real, I have learned of the reliance of newer perspectives on their stable, supportive bases. A change depends on the original. We cannot, and should not, forget to witness what is natural to us. Isolating the magic would dissolve it. We would lose it all: that which is ordinary, magic, and both.

When was the last time a bit of speech left a questionable taste on your tongue? The last time human communication felt magical or unrealistic in its goal? Do you see that this relationship between the magical and the mundane parallels our understanding of others and ourselves? Without an original, there is no new. Without the mundane there is no magic. Without the self, there is no other. Self-contextualization is the groundwork for one’s contextualization of others. We must consider the importance of our natural perspectives when approaching unfamiliar ones. Magic does not exist without a base in reality. Not only would we not realize recognize

it, but also it would not conceptually exist, and it is similar for considering people and peoples distant to us.

Awareness of our positionality enables us to productively approach another. This is the case for religious, intellectual, cultural, political, and all other belief systems which entwine to create your perspective. I am thinking here of the uniquely human power to self-contextualize and the uniquely human task of upholding epistemic responsibility. To be epistemically responsible is to identify yourself as a knower among unknowns. It is to make your evaluation of knowledge— both frsthand and secondhand, new and established, active and dormant—an ongoing effort. Epistemic responsibility involves molding the natural process of observation into an intentional one, and it uses open-mindedness, endless curiosity, awareness of self, and a strong foundation in humility to do so.

Previously, I had believed only a turn from our own assumed and accepted views could lead to a decontaminated window to witness another culture. Edward Said, founder of postcolonial studies and former professor of literature at Columbia, examines how the West perceives the East in his book Orientalism. He confrms our innate tendency to morph reality into our own visions; he writes, “it is perfectly natural for the human mind to resist the assault on it of untreated strangeness; therefore cultures have always been inclined to impose complete transformations on other cultures, receiving these other cultures not as they are but as, for the beneft of the receiver, they ought to be.”

Conceptualization is a necessary, inescapable, and terrifying aspect of our subjectivity, only, to my previous belief, holding us back. The blind who regain their eyesight remain sightless; without training in conceptual recognition and without outsourcing perception to other senses, people with recovered sight experience visual agnosia: an inability to process visual information. We have nothing but notions. Nothing is sensed and understood without interpretation. I believed our only hope to sense and understand the real was to suppress the instinct to cast perceptions into our own concepts. I held my breath and strived to betray the learned conceptions which had betrayed me and which reigned over the totality of my interpretive function. All that allowed me to do was withdraw.

I feared that carrying an intimacy with my personal background while approaching others would negate the entire process of accessing their integrity. How can we help but end up creating our own version of someone else, especially if our learning starts and ends tucked in the folds of our own grey matter? Despite this, I am currently convinced of the value of contextualizing oneself (and holding onto it) before studying others, and I have Edward Said and Charles Taylor to thank. I also have myself to thank. This was not my frst goaround with personal philosophical

rehabilitation. Ironically, it helps to draw on the emotional strength of others who also as high schoolers began their tottering philosophical journey as accidental skeptics.

Reality unravels, depending on who you ask. Every once in a while you will catch a skeptic (or create one). External-world skepticism is an enticing philosophical standpoint which breeds suspicion regarding our human capabilities to connect to and know about the world independent of our own minds. The status of what I call an accidental skeptic is not diffcult to attain, and often it involves taking popular epistemological ideas just a bit more seriously than feels right. Many of us have entertained whether we live in a simulation or if we are really acting out our everyday lives within the bounds of a dream. Those ponderings can root into uncertainties which become more real than the feeling of reality we experience as a person in a physical and mental environment.

My tumble into skepticism occurred after I let loose the innocent question of “is truth even true?” It became my greatest challenge and insult to interact with the outer world I began to doubt. Tim O’Brien in his war stories of The Things They Carried: a work of fction detailed the mental math required to accurately portray extreme experience like his time in Vietnam. Between what actually hap-pened, what seemed to happen, and what felt like had happened, he created the “happening truth” and “story truth,” begging us to consider how fction is truer than true. While this seems to be step towards effective communication and relaying personal narrative, I could not move past problematizing the issue he was actively solving: the question of which factors create our experience of reality, and how we can measure out the facts to speak clearly to a journalist, or sift them out to tell our loved ones what we personally experienced and how we will carry it.

So, if the presentation of the world is only ambiguous in its relationship to truth, how could I defne my own relationship to the world? Solipsistic and idealist thinkers occupy all spaces and times. The idealist Vijñānavāda Buddhist school asserts that all forms belong to cognition. Their dissenters claim the mind is like a crystal; cognition has a transparent nature and any appearance in the mind must be caused by an external object, like how a red thing behind a crystal “implants redness into the crystal”. The Vijñānavādin defends the non-existence of non-mental objects because of causal positive and negative concomitance: for instance, we have never seen an object alongside its cognition. “We do not see fre alongside but separate from smoke.”

I grew reluctantly proud of my ability to distrust what was around me and what I thought was around me. My senses became affictions, betrayals of perceptual functionality that I mourned and celebrated. Subjectivity corroded everything my eyes passed over. How could I ever

understand someone if we perceive a single object and see contradictory properties? The Vijñānavāda school argues that the existence of external objects would be “redundant.” I dulled my senses and tripped into my mind—into such a state of detachment from uncertain reality that it became strange to carry out physical, external procedures. My roommate told me, watching me struggle with our broken dishwasher, “You don’t really... interact with things around you.”

After a suffcient time-out in my skull, I strained to put my faith in reality, realizing my external-world skepticism was a form of faith in itself—the same form of faith I practiced as a willing external-world skeptic. I appreciated that while both accepting and rejecting reality are built on faith, only one begins a path towards what we can consider real. Tim O’Brien, as I see him now, was actually trying to tell me that living in my reality, which is both shared and subjective, is what would bring me closer to the real and the other. Learning to see through our own perspective, and encouraging it as it changes, always has been wise. A doctor can tell me I have perfect adjusted vision without seeing through my eyes. This mindset change was not, as ever, my own revelation, but in debt to the work of those aforementioned thinkers before me who anticipated my coming and the coming of many after me.

It was an encounter with one of Said’s imperatives that thwarted me from what I believed to be the higher endeavor of self-detachment: we “ought again to remember that all cultures impose corrections upon raw reality.” He challenged me to face subjectivity in full as something we must honor. On top of that, Charles Taylor seems to beg us in his tome A Secular Age to embrace the essential nature of our base perspec-