11 minute read

False Freedom and a Forgotten Feminine: A 21st Century Hippie’s Reading of On the Road Emma James

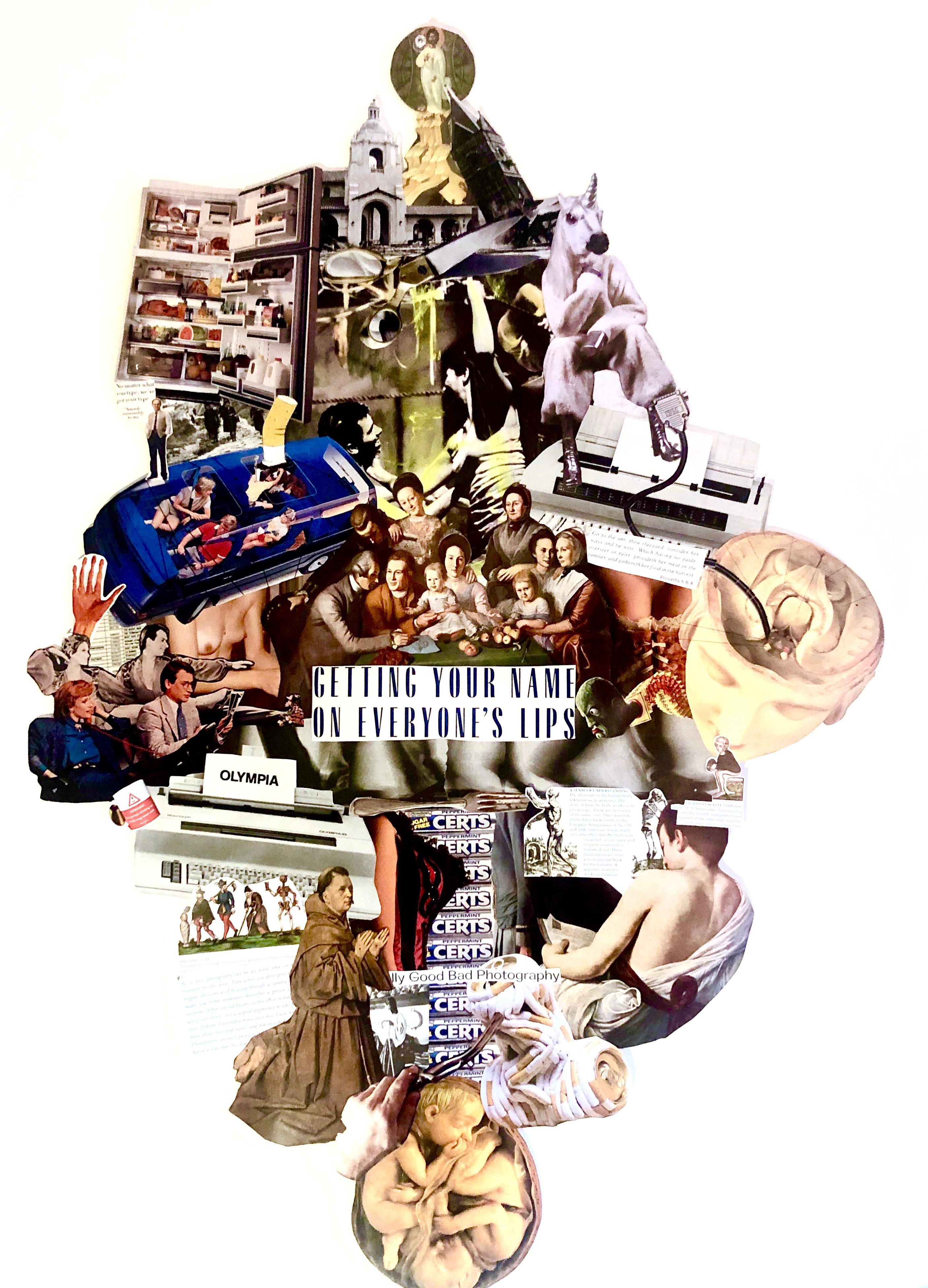

FALSE FREEDOM AND A FORGOTTEN FEMININE

Asynchronicity finds me attempting to write a hook on the beach in Mexico. All I’ve determined is that the flow knows neither mediocrity nor mercy.

Advertisement

Any “alternative” lifestyle is defined in opposition to the default—counterculture counters something. The default of my American youth was woven within financial recession and the structure of elite northeastern institutions. And while I’ll concede that my youth allowed more flexibility than others, with the privilege of skin tone, lack of religious constraints, etc., its structure carried the distinct feeling that “freedom” extended only as far material parameters allowed. Diminished was any sense of creativity or wonder, which were condemned as “childish” from childhood itself on. “Carte blanche” as it was presented to me was a check with thin margins.

But what of a different American narrative, one that embraces not the singular, prescribed, success-driven “Dream,” but rather the opposite? Somewhat forgotten or shunned by my contemporaries for its dated-ness is the classic American bildungsroman On the Road by Jack Kerouac, which I read early into my own travels last year.

The following project attempts to show how a seemingly oblique—nay, illustriously irrelevant—piece of cultural (or just cult) content could teach our COVIDcursed American crop to reclaim real freedom. Maybe, with the pandemic having unsteadied, at a societal level, novel might serve as a means to imagine a post-neoliberal American “hippie” renaissance.

Since during my travels I was not-so-se all-American transcendentalist hippie— after all, I sold my soul to the bean field that my current coming-of-age adventure was a synchronistic reenactment of the novel’s first part.

Having dropped out halfway through his four years at Columbia, Sal Paradise—the stand-in protagonist for Kerouac’s thinly veiled autobiography—is presented with a sudden opportunity to travel across the country with no plan beyond a faraway first stop. Friends he meets hook him up with work, but Sal’s peripatetic longings keep pulling him back on the road again after long; he soon meets a girl from Mexico in California with whom he works and falls in love. Upon realizing their paths don’t align, Sal retreats back to New York to visit a relative, and soon is again on the road.

Sal, however, does not face questions about age and other too-personal details, or curious slash predatory male authority figures, or the threat of trafficking, unlike I and other woman wanderers. While my own story was much colored by my identity as a young and not unattractive woman, women in On the Road are more or less obstacles in the plot.

In her book The Man of Reason: “Male” and “Female” in Western Philosophy, Australian philosopher Genevieve Lloyd Western argues that Western culture codifies mind and reason as masculine, and body and emotion as feminine. To identify the self with the rational mind is, then, to masculinize the self according to entrenched stereotypes. So of course Kerouac, with his Beat vibe, sets women as a backdrop presented only with respect to the inconveniences of romance past lust and babies past that. At best, a sympathetic enough character like Sal can’t keep up with his lover at physical labor and is saved financially by his aunt, and at worst his good friend Dean Moriarty carelessly abandons his fatherly duties for another flame. This American bildungsroman is one concerned only with the “irrational” mind and reason limited to principles of escapism—”I was surprised by how easy the act of leaving was, and how good it felt.”

But the transcendentalist Margaret Fuller imagines that within a female are two parts: the intellectual side, which she calls the Minerva, and the lyrical, the Muse. Towards the beginning of my travels, I, as transplant Jack Kerouac, was employing only my Minerva, for I realize now that I’d learned to ignore my Muse. That learned behavior, or lack thereof, probably dated back to the societal severance of my childhood, which I’d mark by the end of lighthearted “play” sometime during my late preteen years: my crossing of that blunt, vaguely biological line where child becomes woman, a role

demanding her compliance. But sometime on the river, my dormant Muse, a dimension inaccessible to Sal Paradise, was awoken in the form of the divine feminine. Though an appropriation of this term by performative new agey feminist star-folk is reason to cringe, the divine or sacred feminine traces its roots to Shaktism, a major Hindu sect, which recognizes metaphysical reality as feminine and worships the goddess Shakti, the personified creative cosmic energy whose true form, like Western philosophy’s God, is beyond human understanding. So, integrating this divine feminine energy implies recognizing and embracing the feminine not as an obstacle to creation, or even just its vessel, but the absolute driver of manifestation; and conceding that the empirical dimensions of the world, those which alone are recognized because Western conscience can document them, do not account for Lloyd’s body-emotion intuition: the Muse’s lyricality.

In praxis, awareness of the divine feminine deeper distinguishes two essential thematic staples of the American West: the pastoral and the sublime. The former references the supposed peaceful dominion of man over nature, through scenes of farm life and productive abundance. The latter, as particularized by Edmund Burke, inspires awe and can provide pleasure in a way different from aesthetic beauty, rendering them mutually exclusive. While the pastoral paints man as having wrangled the Wild West into a breadbasket for the towns back East, the sublime demonstrates the terrifying ultimate rule of nature over weak, shallow mankind.

The divine feminine, and its stark lack of portrayal in the novel, highlights that Sal Paradise, a young vagabond who frequently feels isolated and is never satisfied, did not demonstrate an ability to function in either a pastoral or a sublime setting. He cannot weather the reality of farm life past the pastoral, and does not yet reach the depth of the sublime in this novel. Through Fuller’s lens, we can conceptualize the pastoral as the reined Muse, the nurturing provider, or just maternal production—potential abundance were the land to be managed with more attunement to the earth—and the sublime as Minerva, the authoritarian mother, maternal strictness when no patriarch stands. But all Sal can do is flee. More

broadly, the freedom offered by the road to pursue happiness does not guarantee it: Sal and Dean, and all the rest, are chasing a fulfillment that never arrives, or if it does, fades as fast as the given night. In fact, that Sal (and Kerouac) behaves so wildly in opposition to the capitalist asset mindset, that he is so committed to possessions and any stability not possessing him, suggests that these forces do still rule him.

In his One-Dimensional Man, Herbert Marcuse expands on Marx’s indictment of capitalism, arguing that the worker is not just reduced to an object in the production machine, but that the worker sees himself as an extension of the products themselves. This object-extension condition raises new generations under capitalism to, in essence, love their shackles: unlike an oppressive overlord clearly identifiable as the enemy, commodities seem to be able to fulfill the want of authentic human attachment that capitalism has stolen.

This capitalist inertia towards “settling down” actually destabilizes the galavanting of ever-unstable Dean—around whom the plot (and presumably real life) is tethered—summoning him to finally take responsibility for his affairs, and leaves Sal adrift in abundant, aimless freedom.

Perhaps the commodified worker does not know what to even do with freedom, how to wield it, and how to lead a moderate life. Of course such an extreme condition would be born from the capitalist chains—Sal and his friends are a cultural reaction quickly shot down. In fact, analyzing the novel itself can devolve into pulling apart some endless Russian nesting doll, since it too exists within American culture... did the wide sale of this book actually inform on or just inform the chains of capitalism? How much sale of an anti-American dream did it sell? Maybe, rather than contributing to workers gaining consciousness of their chains, it was sold as a pipe dream never to be achieved and undesirable to be sought at all, if not playing into that same commodity game.

Perceived rule-breaking is so essential in the bildungsroman because American freedom is freedom from (vs. “with”) others. Fittingly, carte blanche is “at liberty,” often used to usher full discretion over how to manage a military attack: war is the opposite of collaboration. Again, this resistance-of position takes mass culture swallowing and monetizing even counterculture, any soldierly urgency at all. If we’re damned if we do and damned if we don’t, what substance has our freedom? What is our freedom? In his essay "Two Concepts of Liberty," twentieth century political philosopher Isaiah Berlin proposes two senses of freedom: positive, which concerns “the source of control or interference that can determine someone to do,” and negative, “the area within which [someone] is...left to do...what he is able to do without interference.” So by extension, the “desire to be governed by myself”

is different from the desire for action, and positive liberty, he says, is “to lead one prescribed form of life.” But therein lies a false binary: Berlin poses the individual against the aggregated other(s), where one might easily insist on the preposition “with,” or, with others in collaboration. Must the social creature become antisocial for an optimal existence, or “the good life”? It seems not. (I’ve worked on a few extreme off-grid homesteads, and can say with some confidence that no one is fully self-sufficient, not now and not ever.) So, how do we demilitarize—or, disentangle from the assumption of opposing interests and inevitable infliction of harm—the American connotations of "carte blanche" and, freedom itself? Thoreau's civil disobedience? Gandhi’s peaceful nonviolence?

No, the necessary answer to embrace the creative energy of and disarm the assumption of harm that carte blanche implies—the more simple and vastly more challenging root cause of these other symptoms—takes root in Zen Buddhism’s conception of freedom. We must realize that our impulse to think of freedom as from others is fear-based and encouraged by individualist cultures like our own. In fact, the ego’s tendency to escape into consumption and deeper alienation when confronted by opportunities to grow, as Sal experiences, exemplifies the very fear that a capitalist upbringing reinforces. Maybe the only freedom from we should be aiming to seek, if neither commodity nor escapism sustainably satiates the worker’s mind, is freedom FROM the mind itself. In The Way of Zen, philosopher Alan Watts describes liberation as “the recognition that life utterly defeats our efforts to control it”; returning to the apparent absurdity of life at large, more now than ever, we can transform what might be despair into “creative power,” or, I’d editorialize, the divine feminine, by “find[ing] freedom of action unimpeded by self-frustration and the anxiety inherent in trying to save and control the Self.” In a way, this Zen Buddhist conclusion—if the word conclusion were to be appropriate here—mimics the structure of Berlin’s negative freedom, but instead applies it internally. “To the Western mind,” Watts tries to translate, “the puzzle of Indian philosophy is that it has so much to say about what [liberation] is not” because emptiness must come first, before its value can be realized: “This is why Indian philosophy concentrates on negation, on liberating the mind from concepts of Truth. It proposes no idea, no description, of what is to fill the mind’s void because the idea would exclude the fact.” Zen’s approach begins with freedom from self-frustration and anxiety in order to achieve freedom of “the movements [emptiness] permits or the substance which it mediates and contains.” (Note that even in or with or for would be syntactically appropriate here.)

I will share two of Wood’s approximate

births and deaths; the region 'outside heard stated at large, “the cycle of suffering” perpetuated by ignorant desire. It cycles both through reincarnations, but also within one life, for example as Marcuse’s product-extension self-identification: consumption will never fulfill. tivity of the mind, poising itself upon an object or idea, especially when the mind has already fully worked upon the object or idea, and has come to a dead end or a paradox.” Roughly rephrased, it is a state of consciousness reached in meditation. Rather than being alienated from, subject to, or self-identified with any object, the “worker” (or the mind, or simply the “cogito,” thinking itself) might create freedom of [sic.] said object: freedom generated from but finally unconcerned with the object.

Then, perhaps rather than, as Keroac’s thankless Beat gang did (simply taking wherever they went), we vagabonds can liberate “carte blanche” itself from its false, militant conception of “freedom”— we can become free with one another and with the divine feminine that is completely absent in On the Road, through the creation of our own art and expression entirely disinterested in commodity (and/or absolute lack thereof).

It is now spring. I think I’ll go dig a hole.