9 minute read

Freedom of the Present Moment Matthew Harper

FREEDOM OF THE PRESENT MOMENT

Our lives are forged through the decisions that we make every day. Some of these decisions we choose to eat for breakfast or what shirt we wear on a particular day. Other decisions, however, shape our lives in profound and meaningful ways. If someone decides to move from New York City to Rome, for example, they would situations, interacting with different people, and certainly speaking (and hence thinking) a different language than they would otherwise have been. Yet, no mat the ways our lives take course, these de the end of our lives, whenever that time may come, our existence will be marked precisely by these contingent facts.

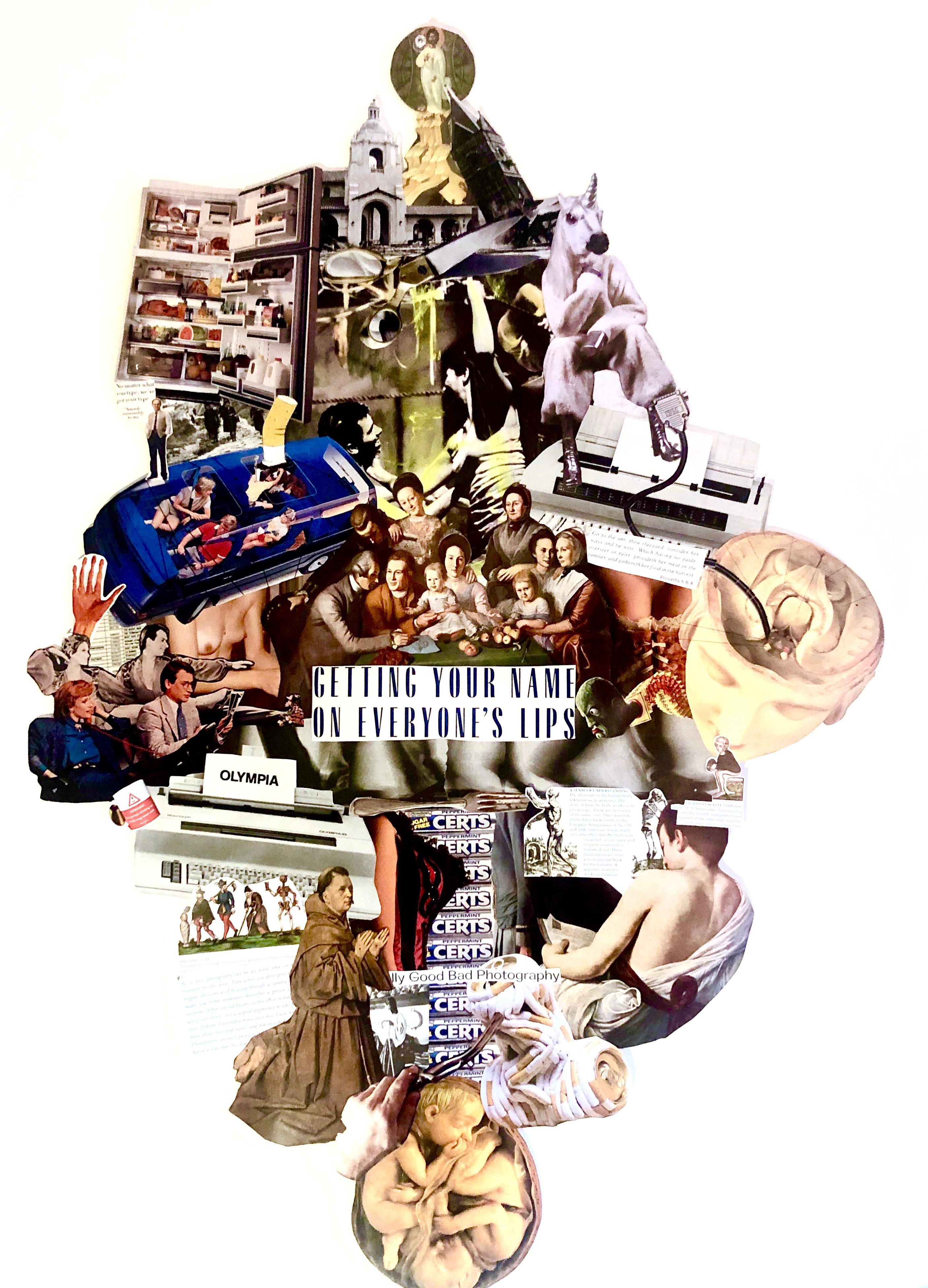

Advertisement

Metaphysically speaking, we can consider our lives in terms of possible worlds, i.e., ways in which the world could have been different. Indeed, we would all agree that the world need not have been the way it actually is. To illustrate, consider what you did yesterday. In that twenty-four hours, you may have gone for a walk in the park, started to read a new book, or spontaneously traveled to Europe. All of these options are strictly possible, even though you would be more likely to do some activities than others. In other words, there is a possible world for each possible way in which you could act, including combinations of such actions. In fact, there is a possible world in which you do all three of these options. Now, suppose that you actually went for a walk in the park yesterday. By acting in such a way, the possible world in which you had gone for a walk (which was previously merely possible) becomes the actual world. Of course, you are still able to read a new book or spontaneously go to Europe at some later point in time. However, with (i.e., yesterday), you cannot change your actions, since they occurred in the past. Hence, what were once possible worlds that you could bring about have now become worlds that would be impossible for you to bring about. It is impossible for you to act differently than you did yesterday.

Up to this point in time, we could have all made different decisions, and in the future, we can make other choices than the ones that we will end up making. Indeed, it is entirely possible that we could live completely different lives than the ones that we are currently living. How would our lives be different if, for any given choice, we chose the other option? In fact, we often spend a great amount of time thinking about the ways in which our lives could be, would be, and even should be. In our daily lives, we quite frequently use our imagination to examine the possible worlds that are open to us. We wish to see how the world might be if some antecedent event (e.g., a decision) were to occur. We think about conversations that we had a few days ago and how we may have responded better. We think about future interactions and how they might play out. Some of us may even think, for

instance, about the particular circumstances of our death: who will be around us, where we will be, and what we will be thinking. From this present moment to the day we die, we can shape our lives in any number of ways. Certainly, what we do today will influence what we are able to do tomorrow. So, how should we decide between the options that are before us? A person’s life can be viewed, from their birth to their death, as the actualization of a particular possible world singled out of the many left unactualized. Which possible world should we pursue and which possible worlds should we reject?

In regards to our lives and the ways in which they may turn out, we are not particularly concerned with the trivial ways in which it may vary. Rather, we want to know the effects of major shifts in our possible worlds and more spe power to actualize. We often spend a great deal of time considering how we may change the actual world and our present circumstances within it to more beliefs, and ideas. Nonetheless, we are not always able to transform our desired possible world into the actual world. Decisions and the degree of freedom to our choices are sometimes (and perhaps often) not up to us. Indeed, we are quite limited by the circumstances of the world or by how other people’s decisions affect us. For example, we do not choose where, when, or to whom we are born. Yet, all of these contingent facts in early youth and beyond. Nonetheless, we each have the ability to affect change in the world, however large or small. If we indexed the possible worlds of the future in relation to how much our actions bring about change in our lives, as we look farther into the future, the differences in the states of affairs in these possible worlds increase. At the present moment, we are highly limited by where we are and what we are doing. However, as we view the possible worlds available to us further into the future, there is a greater set of possible worlds because more is possible. In order for these possible outcomes to happen, certain things must happen between now and that future point in time in order for that possible world to become the actual world.

Yet, every possible world of the future in relation to our lives has a temporal limit. Our existence is such that, no matter what we do, we will all grow old and die. Hence, every such possible world necessarily ends in our death. Despite this important truth of our existence, many people today choose to ignore our entwinement with time. For example, the mid-life crisis itself is an adverse response to the sudden realization that one has lived Indeed, if we have not come to that realization yet, there will certainly be a time where each of us (barring any unforeseen circumstances) realizes that not only have we lived a considerable portion of our lives so far but that we have less time to live. As time passes and we

arrive closer to death, the possible worlds that are open to us are decreasing in terms of diversity, because we are unable to affect as much change in the world and our individual circumstances as we did before. Naturally, we do not know when we will die.

In this way, we should take note of the possible worlds in which we die in the near future. It is entirely possible, metaphysically speaking, that any one of us dies tomorrow. The presence of those possible worlds in our ontology demonstrates an important (and perhaps obvious) truth: the future is not metaphysically guaranteed. We cannot, as a matter of fact, guarantee that we will be alive at any given future point in time.

We live each moment of our lives in the present. In the same fashion as Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am,” our immediate conscious experience of the present moment allows us to guarantee its existence. The past used to exist and the future will exist, but metaphysically they do not exist; only the present exists. Since we cannot guarantee the future nor change anything that has happened in the past, living presently can allow us to live more closely in accordance with the nature of reality. In The Sutra on Knowing the Better Way to Live Alone (Bhaddekaratta Sutta), the Buddha explains:

Do not pursue the past. Do not lose yourself in the future. The past no longer is. The future has not yet come. Looking deeply at life as it is in the very here and now, the practitioner dwells in stability and freedom. We must be diligent today. To wait till tomorrow is too late. Death comes unexpectedly. How can we bargain with it? The sage calls a person who dwells in mindfulness night and day, ‘the one who knows the better way to live alone.

Happiness resides in the present moment. We each have all that is necessary for happiness right now. It is true that we are limited in terms of our actions. There are moments when we have to do things where we would rather do something else. Yet, despite this limit on our possible worlds, we do have the complete freedom to think as we wish. No

matter the situation, we can take that moment as an opportunity to fully realize ourselves in the present. Living in the present moment means that we accept and embrace the fact that any possible world can become the actual world.

Yet, many people believe that their happiness is dependent on the occurrence of some possible event. We often tell ourselves that once we reach a certain goal or aspiration, only then will we be happy. Social discourse often revolves around acquiring money, power, and renown. In view of our metaphysics, these desires are sustained by the future—there is no point in earning money now (i.e., working) if it cannot be used later. Since the future is not guaranteed, it does not make sense that someone’s happiness should depend on unstable grounds (i.e., possible worlds of the future). If we accept that even a normatively bad possible world can become the possible world, then we can appreciate our life thus far, the beauty of the world around us, and our time in existence. Even if we die tomorrow and know it, the practice of living presently can allow us to, nonetheless, be happy and peaceful.

Our actions should reflect our mindset. In The Handbook (The Enchiridion), Epictetus writes, “Do not seek to have events happen as you want them to, but instead want them to happen as they do happen, and your life will go well.” Our lives can turn out in any number of ways. It is true that if we choose alternatively in regards to a significant decision, then we would have

different experiences and interactions. Nonetheless, upon making any decision, we must accept that they cannot be undone. In regards to time, there are certainly no make-ups: once time is spent, it is spent. We may be able to rectify our past wrongdoings, but those original actions will always have occurred. We should not be too focused with how our lives could have been, or can be, different—they are irrelevant for practical purposes. If we are overly concerned with how our lives ultimately end up turning out, we end up missing our lives. Each moment of our lives can and should be an opportunity for us to not only live more fully but to actualize our most important ideals and beliefs, whether in thought or action.