3 minute read

HISTORY

The Fort Zarah Treaty 1866

By Linda McCaffery MA

Research and Collections Specialist Barton County Historical Society

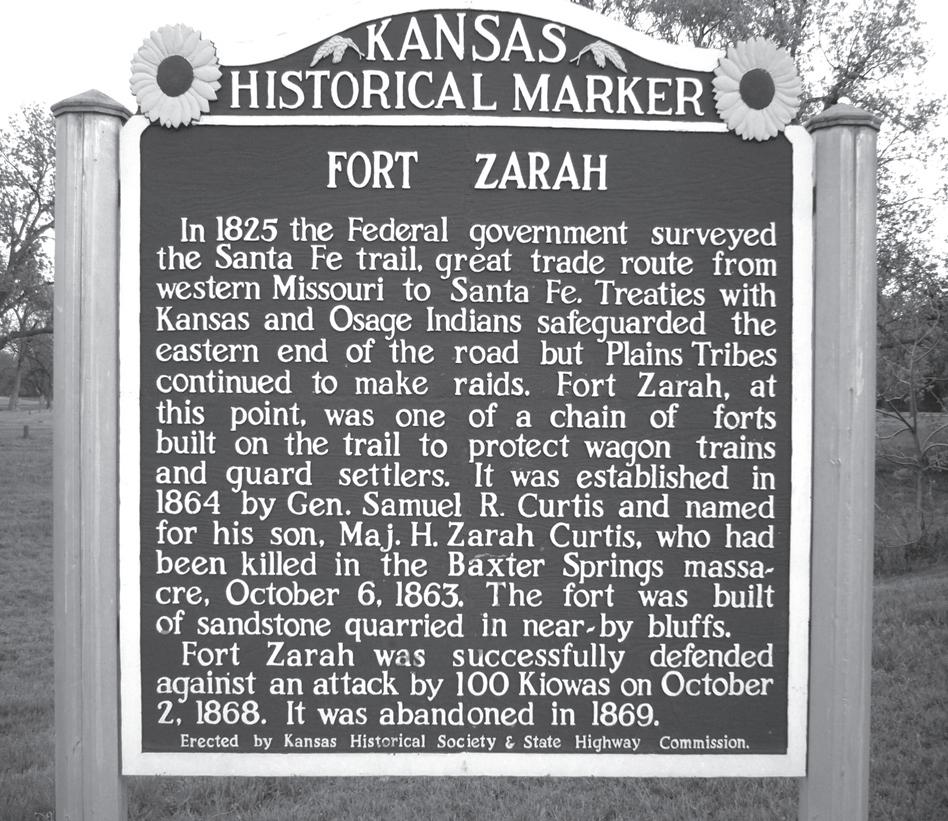

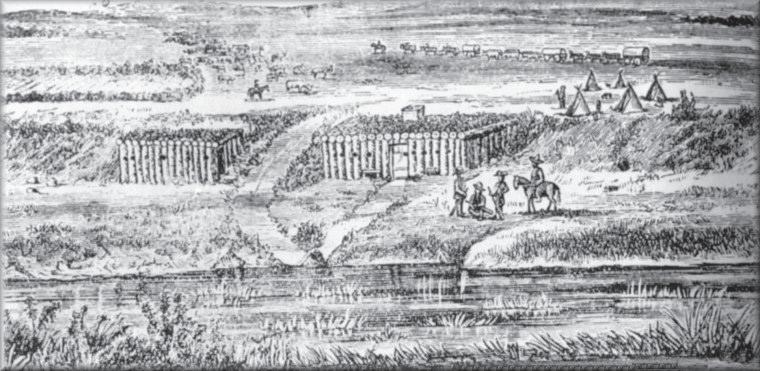

There is a little-known state park between Great Bend and Ellinwood. The fi rst thing one sees as they enter the park is an historic marker describing a sandstone fort located just east of the location, Fort Zarah. The fort existed only fi ve years, 1864-1869, yet it bore witness to both the Civil War and Indian Wars. It was built to protect the strategic crossing of Walnut Creek on the Santa Fe Trail. Today, the site looks like any other wheat fi eld, empty and lonely, but in 1866 the location was buzzing with activity.

During February and March an estimated 4000 members of Southern Cheyenne, “Arapahoe, Kiowa, Comanche, and Plains Apache camped near the fort awaiting supplies or annuities promised in the Fort Lyons and Little Arkansas Peace Treaties. Peace had not been the outcome of either treaty, in fact, one of the most tragic events in American history, The Sand Creek Massacre, had occurred just fi fteen months earlier. Brutality was not limited to the Whites, warrior societies raided along the Smoky Hill River and Santa Fe Trails resulting in many persons killed or captured. With the construction of the Kansas Pacifi c (Union Pacifi c) and the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroads reaching further west, tribes would be forced to cede lands upon which the tracks were constructed and ensure the safety of the construction crews.

COURTESY PHOTOS of santafetrailresearch.com Fort Zarah Paint. (Above) Fort Zarah Treaty 1866 marker.

Runners brought the news to scattered bands of the coming council and annuities’ distribution. In charge of the negotiations was Major Ned Wynkoop, although he had tried to prevent the Sand Creek Massacre, his name would forever be associated with the tragedy. Two other men attending the council: William Bent and Black Kettle, had also tried to prevent the massacre. As with Wynkoop, both men sincerely wanted peace and understood tribal culture. One vital understanding was, one leader or chief did not speak for the entire tribe. Therefore, one or two signatures was basically useless.

Unfortunately, several other members of the council, not only lacked experience, were incompetent or in the case of I.C. Taylor, Indian Agent from Fort Larned, was drunk the entire time. To make the diffi cult situation even worse the quality of the annuity goods was deplorable. Much of the food was rotten and the poor quality of the clothing made much of it unusable.

Another important misunderstanding of the post-Civil War era is, the tremendous debt that the United State Government owed. Amounts promised in treaty negotiations, often were not fully funded. The monies were often further depleted by the greed of Indian Agents.

FORT ZARAH 1864

Wynkoop knew this task would be diffi cult as he was asking the tribes to vacate traditional hunting grounds between the Platte and Arkansas Rivers. These rights had been guaranteed upon a year earlier by some civilian or peace chiefs, however the warrior societies such as the Cheyenne and Arapaho Dog Soldiers had not attended, nor agreed to the plan.

On March 1, Peace Chiefs Black Kettle and Poor Bear met with Wynkoop. Also in attendance were two leaders of the soldier societies, Medicine Arrows and Big Head. Wynkoop reminded the assembly of the importance of peace with the United States Government and Military, which resulted in a signed agreement. However, peace did not follow the attempts to end confl ict. Military defeat, disease and the extermination of the American Bison brought the tribes no alternative but bow to the superior power.

“They made us many promises, more than I can remember. But they kept but one - They promised to take our land ... and they took it.” - Chief Red Cloud, Oglala Lakota Sioux