what was mine is now ours

SPLITTING TO CONNECT: THE KLEINGARTENVEREIN ROLE IN DEFRAGMENTING THE GARDEN AND URBAN COMMUNITY

text & images by

Elisa Cordaro Giovanni Telve

in between community building repurposing

Fragmentation in urban landscapes originates from voids, and given different types of urban voids, different examples of fragmentation will emerge and different strategies for responding to them can be prepared. From this assumption, we've chosen to focus on those spaces that are perceived as voids by most citizens, while at the same time being very relevant to a very defined category in their urban experience: this type of void leads to social fragmentation, as the space acts as a connector for some and a barrier for others, with accessibility being one of the recurring themes throughout our study.

Our work then focuses on analysing how these spaces are perceived, what the threshold is that prevents some people from accessing them, and how flexible this threshold is, with the ultimate aim of

reconnecting these spaces for an overall more readable and liveable city. In our analysis of the empty spaces in the city of Munich, we've found a relevant theme in the allotment gardens (Kleingartenverein), because it's a typology of community space designed for and used by a specific category (the allotment garden tenants) and at the same time potentially open to a wider public, by working on thresholds, space typology and distribution reprogramming and space programme management.

Combining the needs of different communities with a critical analysis of space (method)

Our analysis then starts by collecting data on the presence of allotment gardens in Munich and selecting the relevant ones by overlaying

satellite view of a part of the NO17 garden Google Earth Pro, July 2023

caption of the image source of the image

satellite view of a part of the NO17 garden Google Earth Pro, July 2023

caption of the image source of the image

a map of the gardens with the development plan of Munich 2040, in order to recognise which ones will be critical in the development of the city, so that we can work on them.

We then chose the Nord Ost 17 garden because of its importance as a connecting point between planned green areas and because of its already existing openness, being vertically divided by an inner park with a playground and adjacent to a public park.

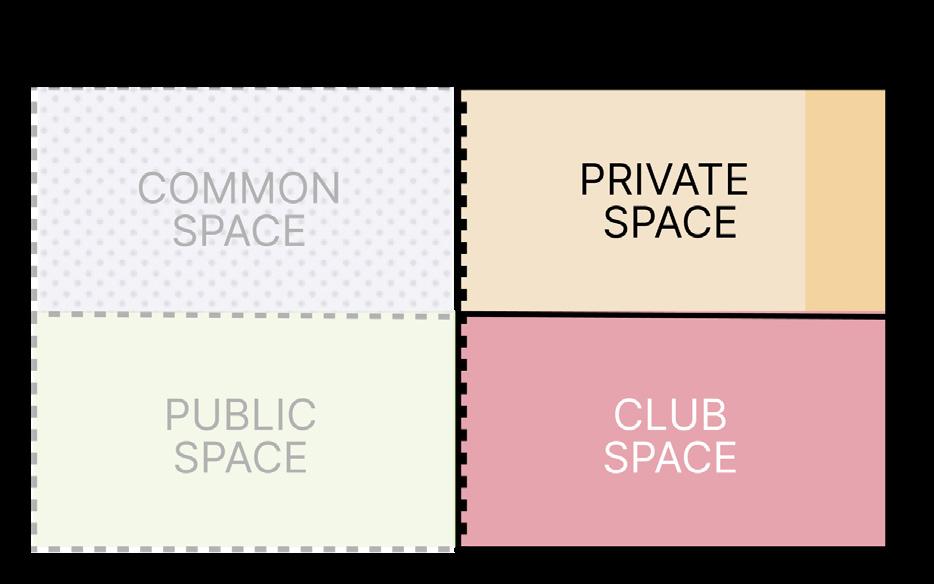

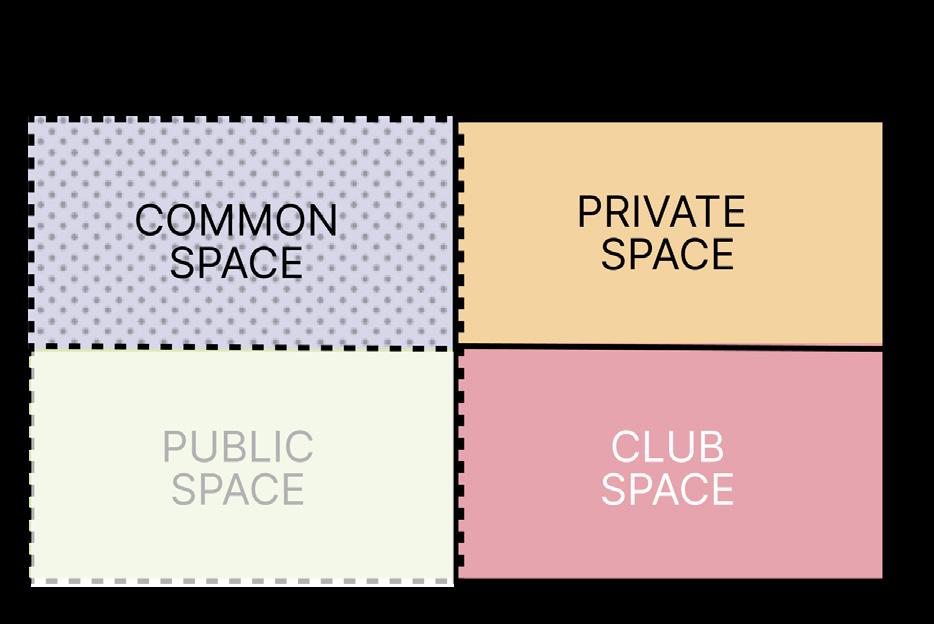

The analysis of the garden focuses on the ownership of land and on its accessibility, parameters that we'll show in the two maps. To analyse ownership, we read this space through the lens of the system defined by Dagmar Pelger by combining goods theory (Ostrom & Ostrom, 1977) and critical spatial theory (Lefebvre 1974, Federici 2004, Harvey 2012, De Cauter 2014): this perspective divides space into public, private, communal and club. We then defined as public the public park, as private the allotments themselves as well as the huts in them, as common the spaces shared by a few tenants, which are not yet present in NO17, and as club spaces the communally managed spaces that are accessible to everyone.

When analysing accessibility, we distinguished between public and private, and introduced the categories of semi-public and semi-private. We define semi-public spaces as public spaces that have no physical barrier separating them from public spaces, except for a visual barrier: the main example in our case is the NO17 park in the centre of the area, which is accessible just like the nearby public park, but which looks like it belongs only to the garden community - which takes care of it, but leaves it free for everyone to

vision

use. Semi-private spaces, on the other hand, are spaces whose accessibility depends on the decision of a group of people who own nearby spaces: in our example, these are the corridors between the allotments, which have a fence that can be closed or not, depending on the choice of the gardeners.

The analysis of the garden focuses on the ownership of land and on its accessibility

Once we had read this space through these lenses, we defined a method that included the gardeners' point of view, since they are a category that would be most affected by a possible development of our proposal.

The method we used then was to understand the gardeners' point of view on the accessibility of the spaces by conducting a long interview with Andreas, one of the gardeners who is partly responsible for the maintenance of the NO17 garden, as well as with Friedrich, who's been in charge of the garden and the link between the Verein and the Verband for the last fifteen years. Their point of view was fundamental in understanding what the main issues were in this Verein: we had then developed different strategies based on our analysis and interviews.

Reconnecting the community to defragment the city (approach)

When studying this case we started from the assumption that allotments are a void in public space, as perceived by those who don't have the possibility to rent one, so our initial focus was on defragmenting the city (and the neighbourhood in particular) by making the gardens more accessible. After more site visits and interviews, we understood that the city can't be defragmented by a fragmented

community, and that we need to work on having a strong community first in order to make it more accessible to a wider one, so we divided our actions on a timeline, showing how we plan to have more interactions and experiments with shared spaces within the Verein itself first, and only later open it up to a wider public when it is solid enough on its own.

Proposing new typologies for land redistribution (project)

We decided to focus on the redistribution of plots because most of them (104 out of 137)

are 400 square metre plots and gardeners on average only use half of them for gardening because they can't afford to take care of more. What also often happens is that tenants who have rented a plot for a long time develop emotional bonds that are eventually harder to maintain, as in order to continue renting the garden, tenants are asked to look after it, which becomes a difficult task as time goes on and gardeners get older.

So while some plots are underused by gardeners, there is a strong demand for allotments, with waiting lists of up to five years: our project is working to bring the

caption of the image source of the image

caption of the image source of the image

needs of these two parts closer together, to the benefit of the gardeners and the wider gardening community, as well as new potential tenants. (Can we talk about supply and demand?)

What we're proposing is a catalogue of typologies to redistribute land

So what we're proposing is a catalogue of typologies to redistribute land that can be implemented as a decision by the tenant who, with the approval of the association's board members, chooses to let his or her plot to be split or shared, according to the different possibilities we're offering.

We propose a range of options, from the simplest, dividing the 400 square metre plot into two equal parts to accommodate an additional tenant, to a second typology of two tenants with a garden in between, to a more