Nowhere Better Than This Place

Volume 3, Issue 2,

Volume 3, Issue 2,

Letter from the Editor - Page 3

Anna Sergeeva - Page 4

Christine Wong Yap - Page 12

jackie sumell - Page 20

Elena Ketelsen González - Page 29

GIRLS is a revised portfolio of interviews from a nationwide community of real, strong womxn. It's a magazine that is 100% all womxn, which is beautiful in its rarity - the magazine is a safe space FOR womxn ABOUT womxn. Created by Adrianne Ramsey, it serves as a content destination for multigenerational womxn. Read on for an engagement of feminist voices and a collaborative community for independent girls to discover, share, and connect. The usage of the terms "girls" and "womxn" refers to genderexpansive people (cis girls, trans girls, non-binary, non-conforming, gender queer, and any girl-identified person).

While art spaces have been able to operate regularly for about two years now, an important question that they had to ponder for over a year was, “How can we safely bring communities together again for in-person viewing?” The roles that community and space have played in our lives have definitely been upended due to the COVID-19 global pandemic, when public art took on greater meaning and importance. Art in the public sphere is one of the most important forums to provide healing, especially during fractured and scary times. Public art creates a sense of community by adding color, texture, and vibrancy to public spaces, thus giving us something to contemplate and talk about in our communities without demanding monetary exchange. So much of what we consider prized and sacred is behind closed doors, with what can amount to restricted access. Art in museums and galleries can hold a certain amount of criticism, but public art is outside and for all, and speaks to our needs to engage with our surroundings. It is for everyone to enjoy, discover, and share, whether it’s a community garden, a zine making workshop, or a postcard project. Art can be creating a connection with someone, encouraging them to step outside of their comfort zone, and participate in an impactful project; it is not solely mutable objects. By creating an issue that highlights art in the public sphere and social practice, I hope to showcase the intertwining's of art and human participation. While we have now settled into a “new normal”, the impacts of distance and seclusion and the temporary loss of social gatherings and community events will last for a while. I am curating an upcoming group exhibition, Rabbit Hole (August –September 2023), for the Berkeley Art Center that looks at how artists consider space, and am excited that there are more conversations about how artists utilize sites and maintain a sense of community within their practices. I would like to thank Anna, Christine, Elena, and jackie for participating in this issue and speaking at length about their creative contributions to social practice. GIRLS 18 takes its title from a diptych stack by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, with each stack containing an alternating line of text: “Somewhere better than this place / Nowhere better than this place”, thus speaking to the larger journey that we are all on: just trying to find our place in the world.

Anna Sergeeva is an artist who works with language as a medium. Her research is centered on form, origins and liminal spaces. She recently opened a bookstore called dear friend books in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. She has previously designed a typeface based on the work of a non-verbal painter, traveled across America asking youth what they would change as President, and initiated a collaborative artwork that has spread millions of compliments internationally. She graduated with a Master's in Library and Information Science from Pratt Institute. Her work has been covered in The New York Times, New York Magazine, San Francisco Chronicle, ABC News, and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in March 2023.

GM: What was your path to becoming an artist?

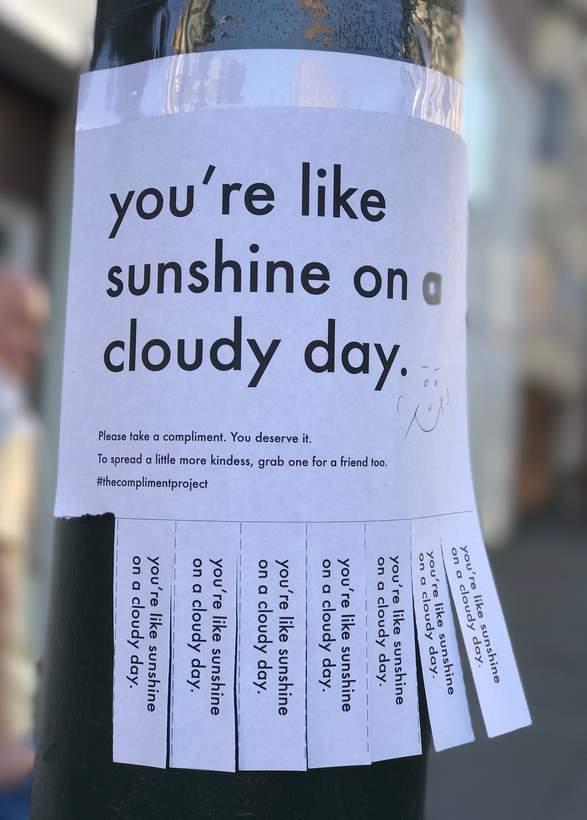

AS: On some level, perhaps, I was always an artist. I was living in San Francisco, working a tech job. It was a great company and team, but it didn’t feel perfectly aligned At the time, I did The Compliment Project, which got a lot of traction and became an inflection point for me. It was covered in The New York Times and other publications, and led to a book project with Chronicle Books that was published a year later. [These projects] led to more opportunities to focus on my practice, and the path continued

GM: Many of your projects embrace the concept of art in the public sphere – do you believe that society is receptive to public art, or are they still drawn to the institution?

AS: When I did a fellowship at YBCA, the question for my cohort was, “Where is the public imagination?” And so, we talked a lot about the concept of “Who is the public?” When you’re talking about the public, who are you actually talking about? What community are you engaging with? When you’re taking work out of the institution and asking these questions, there’s a lot of opportunity for magic to occur. That to me is really exciting – magic that can come into being when a sacred intention meets incredible attention to detail.

GM: Projects such as The Compliment Project (2016), If I Were The President (2018), and YOU MATTER (2020), exemplified art as protest and how artists can use activations to engage with the public. What did these projects mean to you and what was the reaction to them?

AS: I did The Compliment Project right after the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. The rhetoric occurring in public space was filled with rage. I felt like I needed to do something that put a different message out there, a more tender message that was communal in spirit. There is an element of anonymity [to the project] – none of the posters have my name, Instagram handle, website, etc. on them. The project just caught on. It is not about protest or resistance, but rather about tenderness. You never really know how far the ripple can go, like a small stone that you throw If I Were The President was a continuation of that same idea, where the narrative of politics after the election was just so difficult to follow. It felt dehumanized. When I did If I Were The President, I traveled around the country, asking youth between 5 and 18 years old what they would change if they were the President of the United States. I went from San Francisco to Colorado, New Orleans, Tennessee, Ohio, and New York City. “What do we owe one another as human beings?” was really what I was asking YOU MATTER was done in partnership with the San Francisco Public Library, and drew from their community-generated Shades of San Francisco photography archive. The YOU MATTER activation launched right when COVID [lockdowns] began. It was supposed to be this puzzle and activity that you would do in the library, but then all the libraries closed, so the imagery was used to raise awareness for the [2020 U.S.] Census.

GM: You were commissioned by Yerba Buena Center for the Arts to create a public art project, which resulted in love @ first line (2021 – Ongoing). What was the inspiration for this project and how did you construct it?

AS: When YBCA reached out, they proposed this idea of using the entire building exterior as a canvas, with an interactive component in the lobby. It was meant to align with the Center reopening after a long COVID lockdown. Upon visiting the space at that time, that downtown area of San Francisco was very bare, slightly apocalyptic in a sense. It felt like a lot of responsibility to do something of that scale that could acknowledge this context, while also trying to provide something of value to the community So that led to this idea –in general, I always think that the only point is love. Every song is a love song, because what else is there to sing about? I was in this coding class at Pratt, where I completed my master’s degree, and I wrote a Python script that pulled all the first lines of all the love poems from The Poetry Foundation’s website, which is the oldest continuously running poetry publication in the English language I then wrote another script that pulled these lines into groupings of 2 or 3 lines to become their own unique stanzas. I did this searching for the magic of synchronicity. I then collaborated with the YBCA team and a group of translators to pick and manifest these magical groupings in the four official languages of San Francisco, which are English, Tagalog, Spanish, and Traditional Chinese Characters (spoken as Cantonese or Mandarin). All of the groupings that are around the YBCA façade are all unique. It’s not like there is one [grouping] in English that was translated into the other three languages If it was in Tagalog or Chinese, it was just in those languages. [The project] was about making something accessible while also playing with the notion of inaccessibility, which feels to me to capture the complexity of love, of art – not everyone is going to understand the piece, and that’s fine.

GM: love @ first line also includes a postcard component, which was included in We Are Close In Distance, the group exhibition that my MA cohort and myself co-curated at USC Roski's Mateo Gallery last fall. Could you talk about that element of the project?

AS: Besides the exterior space, it was always a core component to have an interactive activity that people could do in the [YBCA] lobby A selection of the different texts that were on the façade were also printed on postcards People could write a message on them to anyone anywhere in the world, and YBCA would stamp and mail them out every week. [This was] totally in touch with the idea that a lot of us remain far from the people we love, and that person could also be yourself. I think there’s this element of tenderness and connection, [which also applies to] sharing your own words of love, in its emotional resonance That ties into your previous question of what my path was to becoming an artist. I think that everyone can be an artist when faced with these opportunities to interact with art, being a part of it.

GM: When you learned about the exhibition’s title and thematics, what did you think? How do you feel it fits into love @ first line?

AS: In talking to you specifically about this exhibition in its beginning stages, there was a focus on longing. [That’s what] really stayed in my mind, this idea of love as longing. (Continued)

Sometimes we can feel far away from it, but that doesn’t mean that the desire and energy to connect isn’t there. I think what you guys were trying to put together in your show was in line with how I think of love and connection.

GM: Absolutely! One of the big reasons why I thought your project would fit in so well is because when we had initial talks about the exhibition's themes, we didn’t realize at the time [that we were influenced] by the COVID lockdowns and forced distance from people we love and care about. Touching one another was prohibited and we were scared to be around each other. There was so much distance, so how do we feel closeness within that? Receiving a letter in the mail can be very intimate, especially when you are forced to be apart. […] I also loved the interactive element of the postcards; it very much embodied relational aesthetics. (Laughs)

AS: When I talk about my practice, I always say that I work with language as a medium. With the postcards in particular, that element of handwriting is so special. Everyone’s handwriting is so intimate to them. You can say the same message in a text message or email, but the feeling of [a letter] is sculpturally and emotionally different when its letters formed by your hand. I love that component of it.

GM: Last year, you opened up a bookstore in Brooklyn, NY called dear friend books, which primarily stocks vintage books and art publications, sells tea and wine, and has an outdoor space for public events. Why did you decide to open a bookstore, and what do you hope to achieve with it?

AS: When the right words reach the right person at the right time, it opens a portal to the divine mind. Opening that portal allows for an inflection point in one’s spiritual, emotional, intellectual, and philosophical development. When you can do that for many people, that can spark a collective evolution of meaningful potential. The bookstore is much more about people than it is about books. For me, it’s about providing openings for beauty, inspiration, nourishment, and conversation. I see this place as a sculpture, a very communal one. Every single person that steps inside is a part of it.

GM: What are you currently working on in your own practice?

AS: A lot of my energy goes towards realizing the vision of the bookstore. I’ve been exploring the book as an object and sculptural form, how it’s being displayed on the shelves, how it’s being created, and what are ways that we can create books that are more communal instead of saying, “I’m the artist/editor and this is my vision.”

Christine Wong Yap is a visual artist and social practitioner working in community engagement, drawing, printmaking, publishing, and public art to explore well-being, belonging, and resilience. She has developed participatory research and public art projects with Times Square Arts, the Wellcome Trust, For Freedoms, the Othering and Belonging Institute, and more. At the start of 2023, she launched two solo exhibitions in San Francisco and led the first contemporary art project in the 172-year history of the San Francisco Chinese New Year Parade. Later this year she will publish a set of 12 zines in an international exchange between New York, Berlin, Tokyo, and Bangalore. After a decade of living in New York City, she lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in May 2023.

GM: Your practice is multidisciplinary and features social practice, drawing, printmaking, and publishing. What was your path to becoming an artist and utilizing these mediums?

CWY: I’ve always loved making art and couldn’t wait to leave my public high school to make art my primary focus. Thankfully I ended up at the California College of Arts, and in my freshman year a teacher had us try relief printmaking, and I was hooked I liked the mark-making, low-tech techniques, and democratic potential of woodcut printmaking. Now when I make prints it’s usually via letterpress printing, but I also see the zines and books that I publish to be in the same spirit of access, dissemination, and decentralization. I came to social practice a bit circuitously; in my 20s, I was a community-based artist and youth educator. In grad school at CCA, I realized that I don’t want to make art about me, so I made installation art for a bit, which gave way towards participatory projects. I didn’t study social practice, but one of my advisors was the late social practitioner, Ted Purves. Ted’s influence, and my experiences working with communities, shows up in my social practice work now. I’m happy that as an artist today, I can draw upon many skills, values, and experiences I gained from different day jobs as an art handler, artist assistant, community-based artist, graphic designer, etc.

GM: Many of your projects emphasize participatory methods in order to create site-specific public artworks. Do you believe that society is receptive to art in the public sphere, or are they still drawn to the institution?

CWY: Both. Society is receptive to art in the public sphere, but a lot of people tend to like what they like. This can lean towards familiar forms of visual communication, which are consumed in established ways. It can be a bit more work to explain a community-engaged, social practice process, and to ask the public to engage art in a different way. The institution is a draw. I remember seeing a class from an elementary school visit a museum, and I noticed that one student wore a suit. On one hand, it was so sweet that the kid’s family thought a museum visit was a special occasion. On the other hand, I believe museums are public resources which ought to be freely accessible, and everyone should feel welcome to visit them anytime – not just on special occasions organized by schools. Isn’t it strange to think that art or culture aren’t native to our public spaces? I’ve been working in San Francisco Chinatown and Manilatown, and it’s a really vibrant neighborhood where art and especially culture exist in public spaces. Partly because of urban density, and partly because organizations like the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco make it their mission to program beyond the walls of the gallery. Just walking down the street, you can encounter a lion dance rehearsal, hear various dialects, try cultural foods, see public art activations, and so on. Maybe we ought to be less receptive to the amount of public spaces given over to producing and consuming commodities, and normalize public spaces that support us in being who we are and sharing that with other people.

GM: You’ve opened two solo social practice exhibitions this year, Recognitions / 认 • 知 at CCA’s Campus Gallery and How Do I Keep Looking Up / Como Sigo Mirando Hacia Arriba / 仰望 at the Chinese Cultural Center of San Francisco Both projects highlighted migration and cartography – why was this important to you, and what did both projects mean to you?

CWY: I’m the daughter of immigrants whose migrations spanned China, Vietnam, Hong Kong, and the Dominican Republic. It’s easy for people to look at me and assume that me or my parents had a straightforward, middle-class migration from China, which disregards my family’s lived experiences of war, the threat of persecution during the Cultural Revolution, food insecurity, sacrifices, uncertainty, persistence, resilience, survival, and hard-won accomplishments, all of which contribute to intergenerational legacies that shape my identity and mindset. I’ve been exploring belonging for a few years, and working in hyper-local contexts allows me to gather more specific insights. San Francisco is one of the most expensive places to live in the U.S., and national publications’ “doom loop” narratives about this city typically center the concerns of the hyper-privileged rich and criminalize and other the hyper-vulnerable poor, while ignoring the working-class, immigrant residents who fight everyday to call this city home. I want to celebrate the people, cultures, and neighborhoods that give San Francisco vibrancy, diversity, texture, and humanity. These projects welcome newcomer youth and highlight working class women’s lives and resilience. They widen my world by building bridges that span local neighborhoods and countries of origin. There’s so much media attention on corporations that leave the city, and not nearly enough about the heartbreak caused by policies that separate families through immigration, displacement, and gentrification.

GM: You also recently completed a month-long residency at the Berkeley Art Center, Holding, which activated the gallery space with self-care workshops and zine production. What was the inspiration for this project and how did you construct it?

CWY: I was inspired to create an international zine exchange and grassroots knowledge bank on belonging and mental health. The zine is called Kindling: Activities to Spark Joy and Belonging Gathered from Around the World, and it resulted from a social practice residency with Mindscapes, the Wellcome Trust’s cultural initiative exploring mental health To gather the content, I co-led 11 workshops in the four Mindscapes cities – New York City, Berlin, Tokyo, and Bengaluru, India – in 2022. Nearly 100 participants hand-drew 85 contributions; there are four zines, one for each city, and the set totals over 200 pages. It’s now available in English, and the German and Japanese translations are forthcoming The Self-Care Card Deck project is inspired by my interest in positive psychology, and my belief that we already know what we need to do to take care of ourselves, but it’s hard to practice it. It can be beneficial to have the time to reflect on self-care and be spurred to think more deeply about the ways we care for ourselves [That can be] through getting to know ourselves better, practicing self-acceptance or self-compassion, cultivating joy and wellbeing, and so on. (Continued)

The process of sharing something you’ve learned with others can also help you see the value of it

maybe you’ll savor it a little more the next time you do it, or find more meaning in it. I’ve also heard from participants that being part of the workshop, and simply having the time to engage in creative self-expression, is itself a form of self-care, when so much of life is stressful, outcome-driven, or productivity-oriented.

GM: Alive & Present: Cultural Belonging in S.F. Chinatown & Manila Town is a comic-zine project about migration and belonging. This project features both English and Chinese translations – how does this influence how you want the audience to interact with the work?

CWY: The bilingual nature is less about how the audience will interact than who the audience would be. The comic book is the result of a participatory research project about how arts and culture impact people’s senses of belonging in Chinatown and Manilatown. San Francisco Chinatown is a really special neighborhood, where immigrants and their descendants find a sense of identity-affirming comfort in the language and culture Compared to the rest of San Francisco, those residents have a higher median age and lower levels of income and education. Knowing this, we created a Chinese language so more locals can read it. I made it a comic book so it’s more friendly to language learners. While institutions sometimes look to artists for creative place-making, I think this project is more about creative placeknowing – recognizing the cultural assets that are already in place, reflecting that back to the community, and proclaiming them worthy of preservation and patronage. This is in the larger context of gentrification, which has squeezed so many working and middle-class families out of San Francisco, as well as the context of the peak-pandemic, in which Chinatown’s small businesses were hit with a double-whammy of lockdowns and anti-Asian xenophobia We gave out hundreds of copies to local residents through clinics, community organizations, and our storefront installation, and I hope it supported a sense of solidarity, pride, and connection in a moment of fear, anxiety, and disconnection.

GM: What are you currently working on in your practice?

CWY: I’m currently working on the German and Japanese translations of the Kindling zines. After the three shows, which opened in rapid succession between January and March, I have been working on restoring a healthier and more sustainable work-life balance, building community, reading, making things in the studio – including letterpress prints – and generally following my curiosity and personal growth.

Christine

with contributors, How I Keep Looking

, 2022–2023, social practice, community-engaged process, 16 banners marched in the Chinese New Year Parade, banners: 35 x 47 inches each.

Christine Wong Yap with contributors, Alive & Present: Cultural Belonging in S.F. Chinatown & Manilatown, 2020, community-engaged process, 56-page comic book available in English and Chinese, 8.5 x 7 inches.

jackie sumell is a prison abolitionist and multidisciplinary artist inspired most by the lives of everyday people. She has spent the last 2-decades working directly with incarcerated folx, most notably, her elders Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox. Her work, anchored at the intersection of abolition, social practice, and contemplative studies, has been exhibited extensively throughout the U.S. and Europe. She has been the recipient of multiple residencies and fellowships including, but not limited to a: 2021 Art Matters Fellowship & Joan Mitchell Studio Fellowship, 2020 Art 4 Justice Fellowship, S.O.U.R.C.E.

Fellowship and Creative Capital Grant, a 2019 A Blade of Grass Fellowship, MSU’s Critical Race Studies Fellowship, a 2018 Robert Rauschenberg Artist-asActivist Fellowship, Soros Justice Fellowship, Eyebeam Project Fellowship and a Schloss Solitude Residency Fellowship. sumell’s collaboration with Herman Wallace (a prisoner-of-consciousness and member of the “Angola 3”) was the subject of the Emmy Award-Winning documentary Herman's House (Best Artistic Documentary 2013). An ardent public speaker and organizer, sumell's work with Herman has positioned her at the forefront of the public campaign to end isolation in the United States, inviting us to imagine a landscape without prisons.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in June 2023.

GM: What was your path to becoming an artist?

js: My path to becoming an artist was similar to my path towards abolition, which was circuitous and unexpected. I studied sports medicine and physical therapy in undergrad; my mom was a nurse and my dad was a prosthetist, so they were both in healthcare and I figured that that was my direction too But I was a weird, dyslexic kid who would draw a lot and was very creative in many ways. I ended up as an artist after graduating from the College of Charleston and on my way to law school. I was experimenting with all these different programs, and I had an art teacher, Kathleen Anderson, who stepped in. She had heard that I was studying for the LSAT and I said that I thought I would be a good lawyer because “I’m pretty smart and a good debater, and there is a lot of injustice and wrongdoing.” I was super ignorant of what the law does, and she said, “I think you’re doing it because you want to be important and [this is] the wrong crowd to be important amongst.” She thought I should be an artist and recommended I get an MFA, as she had seen me teaching younger students and said that the terminal degree would allow me to teach at the collegiate level. We spent the next eight months working on a portfolio, which then took me to the on-ramp of becoming an artist.

GM: There are many parents that pressure their kids to have those 3-4 standard career paths – doctors, lawyers, politicians, etc. – when the reality is, there’s importance in everything.

js: When I told my mom that I was going to go to get an MFA, she was really disappointed because she wanted me to be a pilot, or a doctor She also wanted me to be married and have kids by the time I was 26 As soon as I got into Stanford, she was said, “I always knew you were going to be an artist!” (Laughs) It’s funny. But I will say that I did not believe in the value of art for a very long time, and found it to be superfluous – a practice of the privileged, something that wasn’t available to everybody, and therefore, in my mind, was wrong. As I grew into being the artist that I am becoming today – because it’s an infinite process – I started to realize that it’s a superpower. Being an artist is really incredibly brave, especially with projects like Herman’s House and Solitary Gardens. The reason that art is not funded and is the first programming to be cut from curricula is because of how powerful artists are. That is the position that I’m in now, 25 years later.

GM: A big emphasis on your practice is working with incarcerated individuals, such as the two decades you spent working with the Angola 3 – Robert King, Herman Wallace, and Albert Woodfox. What was your experience working with them?

js: All of my personal and political orientation is because of the Angola 3, Herman and Albert in particular. I live in Louisiana because of those men, and under no uncertain terms it was their great tutelage, patience, love, and permission that has really informed and made possible the work that I do today. I wouldn’t do this work if there wasn’t consent Now that Herman and Albert have joined the ancestors, this work is a way for me to thank them It’s not like I can just call them up anymore, or write them a letter. (Continued)

You’re asking what that was like, and it was really hard. It’s not easy going into prison, particularly Angola, twice a month, or living in Louisiana. The trajectory of what my MFA program wanted me to do is very different than where I landed, which was this space of incredible meaning and purpose, and there’s no tradeoff for that There’s no show, fellowship, or art award that I would ever trade for the love that I received from those men. This work isn’t just an expression of gratitude. I was advocating for abolition while I was in San Francisco, working and writing. It was 2005, Hurricane Katrina had just happened, social media was in its nascent stages, and one of my elders, Malik Rahim, put out this call and said, “You all call yourself activists, you better act!” (Laughs) And so I came to New Orleans for two weeks with a group of folks that I knew from organizing around the Angola 3, and seventeen years later, I’m still here.

js: I spent twelve years collaborating with Herman – mostly through writing, visits to the prison, phone calls – and designing his dream home. When Herman joined the ancestors, here I was in New Orleans, working on this project called The House That Herman Built. I was really unsure of what my next move was going to be. At that point, I had thousands of letters from Herman. I went back, read them, and realized how much Herman talked about plants and gardens [Herman spent] forty one years in concrete and steel I knew there was some way to uphold the life and legacy of that man through gardening, but I wasn’t a grower – I didn’t even like gardening at the time! (Laughs) It’s funny to think about it now because the relationship to the beloved natural world and gardening is such a big chunk of my life. Herman was in his twenty-ninth year of solitary confinement when I asked what house he dreamed of. He said that he could clearly see the gardens, filled with roses, and wished for guests to be able to smile and walk through gardens all year around It was the first thing he asked for, and I find that really remarkable and revolutionary – that this man that was condemned to concrete and steel found so much of his liberation in gardens. I visited my friend, Leo Gorman, who started this project called Grow Dat, and at the time it was basically a grassy field with a couple of raised beds. I was struck by the size of the garden bed, realizing that it was around the same size as Herman’s cell And then it was download after download of thinking about how to illustrate the inhumanity of solitary confinement and uphold the life and legacy of such a remarkable man, but not just leave things there. [I wanted to] be able to affect change in real time and do this through an abolitionist lens and lifestyle – and so that was the genesis of Solitary Gardens.

GM: You have had a long-standing collaboration with MoMA PS1, which resulted in Growing Abolition: jackie sumell and the Lower Eastside Girls Club (April – October 2022), as part of PS1’s Courtyard and the Life Between Buildings exhibition, and Freedom to Grow: The Lower Eastside Girls Club & jackie sumell (November 2022 – April 2023). What did both of these projects mean to you?

js: I was invited to speak on a panel at PS1 for the Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration exhibition, and I asked if I could speak with my friend, Mariame Kaba, about abolition. They agreed, so Mariame and I spoke to this open audience about the value of abolition, what it means to be an abolitionist, and how the plants actually teach us about abolition. (Continued)

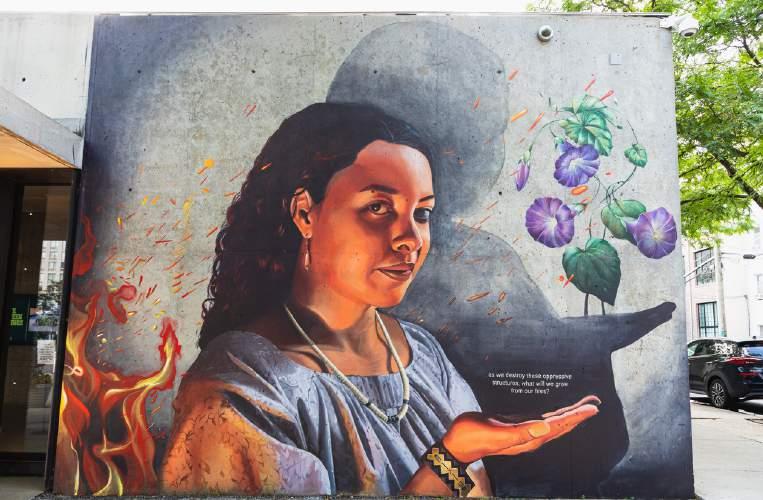

Through that presentation, two PS1 curators, Elena Ketelsen González and Jody Graf, said they wanted to work with me They embarked on this process of following wonder, curiosity, and learning; I often use this framework [to show that] the first ingredient in abolition is relationship. There’s no academia or theory that could ever replace the relationships that you build. The possibility of existing in a landscape without prisons is narrowed or impossible if you’re not actually building trust amongst community, and I think that PS1 really did that. They said, “Let’s spend 2 ½ years building, trusting, learning from each other, and jackie, who do you want to work with?” I was already working with the Lower East Side Girls Club and Kelly Webb; they had a Solitary Garden on their rooftop, and it was a very natural and sustainable fit for a massive institution like PS1. Elena was the one who asked, “How can we continue to grow this relationship?” That’s how Growing Abolition became Freedom to Grow. […] You know, I have been so busy that I haven’t had enough time to pause and reflect on how fucking remarkable it was. We transformed the entire courtyard, this brutalist architecture that looks like a prison yard, into a garden – and it was spectacular.

GM: In 2022, you published The Abolitionist’s Field Guide, which is an interactive workbook that emphasizes abolitionism through the lived experience of plants. What inspired you to create this book, and what do you hope its audience takes from it?

js: The book was made during the height of the COVID pandemic lockdown. It was a really exciting venture, to make a book that brought together my very isolated time in the garden and the lived experience of twenty years of prison abolition. My hope was to be able to share [moments such as] the way that the plants are talking to me, and create different points of access for folks who are abolition curious I really struggle with literacy, I’m dyslexic, and my reading comprehension has always been really low, but I’m hyper vigilant, intelligent, and my intuition is on point. There are all of these different ways of learning that the garden really upholds, and there’s a dominant academic language around abolition. I just don’t know if that’s for everyone, because I know it wasn’t for me I needed to live it, work it, and be in proximity to Herman and Albert in order to understand The Abolitionist’s Field Guide was really a part of providing more ways of inspiring wonder and curiosity, and accessing an abolitionist lifestyle and lens – not as a destination, but as a practice. Sometimes when I lecture, enough people will say, “I understand abolition for non-violent offenses.” But what happens when you insert the most hyperbolic, intense, unbelievable harm? I generally reflect that question back to folks by asking, “Was there anything you’re particularly good at?” Is there anything you’re good at, Adrianne?

GM: I’m very good at providing a platform for people to tell their own stories, whether that’s through GIRLS, exhibitions, or programming. To this day, one of my favorite companies is American Girl. I still have my American Girl doll and so many of the books – the Historical Character series, History Mysteries, and Girls of Many Lands series. Those were great ways for me to learn history and how gender roles evolved and changed over time What I love about that platform is that it tells all these stories from diverse girls I was always very engrossed in the books and learning in that way, so I cite AG as one of my sources in learning how to tell stories.

js: That’s beautiful! That illustrates where I’m going with this – you didn’t start off as a great storyteller. You had a curiosity, right? You followed it, and whether or not you were conscious of it, you were building your skill, reading, studying, and coming back to it again and again. Abolition is like that. You don’t necessarily start out with the most hyperbolic, violent offense or harm that someone inevitably will cause and has caused. You start off with the microaggressions, micro-harms, and then come back to it again and again, you practice, until you have a comprehensive way of responding to harm without causing more.

GM: Many of your projects embrace the concept of art in the public sphere – do you believe that society is receptive to public art, or are they still drawn to the institution?

js: Both the status quo and the institution relies on one another because the institution has made it such. Right? The institution, which is very much capitalist driven and rooted in practices of white supremacy, has said that they will determine what is valuable and what is art. They make those determinations based on how they can create more capital for themselves The arts are considered extra, disposable, or not necessarily important. When an institution says an object is important, it’s almost like The Emperor’s New Clothes. My artist homies are my deepest and most treasured homies. I am so grateful for all the ways I can see, feel, and experience the world with the lenses of liberation and freedom – because of the artists in my life. I’m not tethered to what bell hooks called “imperialist white supremacist capitalist hetero patriarchy.”

GM: What are you currently working on in your practice?

js: The Abolitionist Apothecary is in a space right now called The John Thompson Legacy Center. Part of the big picture ways we’re dreaming of are different collaborations and activations in this building in order to create a sustainable abolitionist diversion program. This summer, I’ll be working with Mel Chin to create a gathering surrounding social practice, and in the fall, I’m working with Tulane University’s Small Center to think about a design project at the Legacy Center. I’m also working with Rice and Colgate University about ways of activating plants and growing; we’ll be hosting the next iteration of the show that was at PS1 at Colgate. But I will say that in really listening to where I am in time and space, and making it to 50 this year – I don’t want to do this work forever but I promised to leave it in a space where it can sustain itself Big picture, I’m organizing the next five or ten years of my life around leaving this work in a place where people can come in and continue it. I am thinking about ways I can co-create through social practice, relationships, and an abolitionist lens. At some point I want to be able to step away, move a little bit slower and with a little less intensity.

Elena Ketelsen González is an Assistant Curator at MoMA PS1, where she has worked to organize activations of Homeroom, a space dedicated to collaborative projects with artists, organizations, and activists. Previously, she held programming positions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of the City of New York, and was the founder of La Salita, a curatorial project dedicated to researching and collaborating with artists working from Latin America and its diasporas. She frequently contributes writing to print and online publications, and often presents and lectures at universities and other institutions.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in June 2023.

GM: What was your path to your current career, as well as your job at MoMA PS1?

EKG: I was born in San José, Costa Rica, and migrated to Southern California at a young age, going back and forth between the two until I went to college. In Costa Rica, there were so many artists in my family, and my mom used to take me to see their student work at the University of Costa Rica. I would also spend time with my aunt at the art center where she gave classes, organizing and cleaning materials, and helping around the studio in exchange for lessons In California, I grew up in a working-class immigrant neighborhood, where my father was always involved in grassroots organizing around education and the environment. As a young child, he would take me with him when he worked the census, and I would help translate. It wasn’t until I was in undergrad and obtained a work-study job at the University art gallery that I learned for the first time what a curator did, and I remember being so excited that I could spend time with art and the public as a career. After college, I was recruited by Teach for America to teach in a dual-language program at a public school in East Harlem, and I jumped at the opportunity because they offered to pay for me to relocate to NYC and fund my master’s degree. I taught in the DOE for 4 years before finding my way back to museums, where I worked as a freelance educator for a few years before getting a full-time job in the Education Department of the Whitney Museum. That was incredible because I got to see how a large institution operates while being immersed in their history of American art. While there I built a program called Tours for Immigrant Families, where I worked with community organizations to bring in Spanish-speaking families to experience the museum Marcela Guerrero had just been hired and curated her first show, Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay, and I was starting my independent curatorial project La Salita. Seeing Marcela in this role was critical because it made me believe I could get there too. From there, I went to Gracie Mansion, where I was a curatorial assistant and program manager, and then I came to PS1 as a Fellow, where I am now an Assistant Curator. I moved around a lot and learned everything I could at each place to get to where I am now. I also knew when it was time to leave a place where I wasn’t being valued, which is difficult to do as a junior-level museum worker. PS1 is the first place where I’ve been able to hit my stride and see a future for myself

GM: You recently organized Freedom to Grow: The Lower Eastside Girls Club & jackie sumell (November 2022 –April 2023) and Malikah (May – October 2023) as part of PS1’s Homeroom initiative. What was your experience working on both of these shows, as well as organizing programs and exhibitions for Homeroom?

EKG: Homeroom is really the place where all my worlds come together – community organizing, radical pedagogy, and working with art and artists. I feel so lucky to have this space to experiment within MoMA PS1, a site of radical experimentation since the 1970’s as an alternative art space housed in a former school building I co-organized Freedom to Grow with my colleague Jody Graf, who concurrently organized a show called Life Between Buildings, which looked at how artists took up the space and politics of interstitial spaces in New York City. (Continued)

We worked with the artist jackie sumell and young people from the Lower East Side Girls Club for over 2 years, with the result of that collaboration culminating in the Homeroom exhibition. That was such a successful collaboration because we implemented abolitionist frameworks of collaboration and consensus-building in our curatorial model, and the result was an exhibition that celebrated the process as much as the product and was in conversation with an intergenerational group of artists and communities across Queens and NYC. I co-organized Malikah with Rana Abdelhamid, an amazing community leader in Astoria, Queens. We had 12 women from Little Egypt, Queens in residence for 8 months working on how to tell their migration stories through oral histories, photo archives, and portraits commissioned by Sandy Ismail. The methodology for Homeroom centers on collaborative curation, where groups often relegated to recipients of knowledge rather than makers become active participants in the telling of their histories, with me as the liaison between them and the institution. Recently, we had a huge Open House event where Malikah hosted performances and activities. At the same time, there was an Art21 screening of Daniel Lind Ramos’ exhibition, a talk by renowned anti-colonial thinker Silvia Rivera Cusicancui, and a performance by the avant-garde ensemble Standing on the Corner. It was a powerful moment of seeing this intersectional and intergenerational work come together throughout all of PS1 in a way that challenges traditional models of exhibition-making and public programming, as well as bringing together a diverse group of artists and audiences in celebration of each other.

GM: MoMA PS1 recently announced that you will be curating Leslie Martinez’s first museum exhibition in New York. What will the exhibition be about, and what has your experience been curating the show?

EKG: Leslie Martinez is an incredible artist whose work I have been following for a few years, hoping we would collaborate. They create sculptural paintings that explore place and ancestry in relation to labor and the handmade, drawing on formal legacies of abstraction, as well as generational practices of survival and sustenance learned from their family. The show will be spread across 3 galleries, so we have the opportunity to show various aspects of Leslie’s practice. One room will have work selected from the past 3 years that focuses on their process and recent material breakthroughs, while the other 2 spaces will feature works that are imagined specifically for these spaces. I am really excited because Leslie is working on a large-scale installation that will be unlike anything you’ve ever seen from them before, thanks to PS1 being a space for artists to experiment, along with the care and magic that is our exhibition team. Leslie spent 15 years in NYC before returning to Texas, so this show marks a homecoming for them in many ways, for which they are working on a monumental gesture. I’ve often heard people talk about my work with artists as one of “taking up space” in spaces where their presence was notably lacking I love thinking about how so many practices, from public programs to painting, can achieve this. How can a formal exploration of material and abstraction also be political? This is a conversation Leslie and I keep having, and I look forward to people seeing how that comes through in the show

GM: Over the course of its history, MoMA PS1 has a big emphasis on artist activations and interventions. Do you believe that society is receptive to art that highlights community engagement?

EKG: It’s funny because I often see my work framed as community engagement, which is such a loaded term. Whenever an institution uses the term “community” without defining it, I know what they mean

BIPOC and/or the working-class. But community engagement operates at every level of the museum –the workers are a community, artists have their communities that intersect with others, and then there is the neighborhood, the borough, the city, and global networks. None of these are monolithic. I would argue that PS1 has always foregrounded community engagement, because when Alanna Heiss took over the building in the seventies with a group of artists that were living and working there, that was a community! I see my role as one that works to expand the definition of who gets to be in that community, and in what capacity What happens when you give a group of young people from Queens the same resources you would offer an international artist having a solo exhibition? The results are undeniable, and we can see a huge culture shift when that work gets recontextualized – not as community engagement, but as a part of this incredible lineage of artist activations and interventions. As to whether society is ready for that or not is not a question that interests me, as dominant culture has never welcomed work that questions its authority. So many people are held by the work we are doing collectively, and that is the who and what I am invested in – everybody else will catch up eventually.

GM: In 2019, you founded La Salita, which is described as “a curatorial project and long-term investigation dedicated to researching and exhibiting contemporary practices of artists working across Latin America and its diaspora.” Why did you begin this project and what have been some of its highlights over the years?

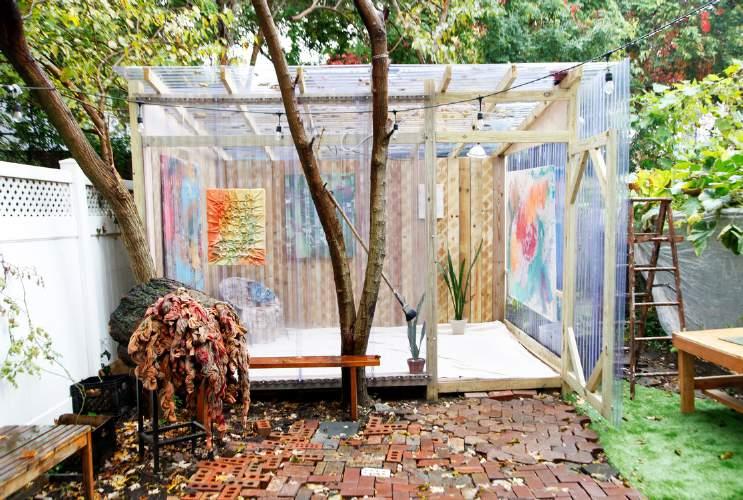

EKG: I founded La Salita out of a desire to create a space in which we – intergenerational artists and curators working in the borderland space between NYC, Latin America, and the Caribbean –could create exhibitions, gather, and think and write critically about our work from our own positions and contexts. In every museum I had worked in until that point, we were always positioned as marginal, despite that not being how we perceived ourselves when in community At the time, I was living in a space that worked well for exhibitions and gathering, so in 2019 I took a chance and started programming it. We hosted 7 exhibitions before the pandemic, as well as programs like Eva Mayhabal Davis’ El Salón. The last show before the pandemic, and before I left that living space, is one I will never forget: it was a great exhibition that we inaugurated with an El Salón potluck that turned into an absolute dance party. We didn’t know it would be the last in the space, and people still tell me today how special that moment of gathering was. (Continued)

During the pandemic, I collaborated with Amor Fuego in San Juan, Puerto Rico to host a solo exhibition with Camille Rouzaud that included works they created while in San Juan, New York, and later in France, while waiting for approval of the O1 visa. In late 2020, I curated a show of Cassandra Mayela and Basie Allen’s works in their backyard studio, which was built by Basie Allen and is still one of my favorite projects I have ever worked on. I love showing work in places that weren’t intended to be exhibition spaces; it is a fun challenge and opens up conversations about the material realities of the way artists make work and the long history of artists making and showing work in alternative spaces across NYC.

GM: Do you have any upcoming plans for La Salita?

EKG: I am really focused on bringing that La Salita energy to my work at MoMA PS1, and utilizing the means available to me to open up the museum. I am still in close contact with many of the artists who showed through La Salita; I will always champion their work and look forward to collaborating with them in many contexts in the future. With La Salita, we were all operating from scarcity to create moments that felt plentiful. While there was something beautiful about that, I want to be very honest – the reality is it wasn’t sustainable. I founded La Salita in part due to the systemic exclusion of artists and practices I was passionate about in all the museums I had worked in. Now I am in a position where I can work with others to create the conditions for these practices to thrive over time, and I very much want to lean into that abundance. I saw La Salita as a curatorial project within the legacy of alternative art spaces in NYC, for which PS1 was always a blueprint to me – I wouldn’t be at PS1 if not for the experience and relationships I built through my independent curatorial practice, so I see my institutional work as a continuation of all of that thinking. I also don’t see any of this as linear – La Salita will always be there. It is life-long work, and it is very present in all the work I do.