GIRLS MAGAZINE

THE LAST TEXT

Volume 3, Issue 4, April 2024

THE LAST TEXT

Volume 3, Issue 4, April 2024

Letter from the Editor - 3

Nahui Garcia - 4-10

Ali Pinkney - 11-19

Lydia Rosenberg - 20-28

Vivian Sming - 29-36

GIRLS is a revised portfolio of interviews from a nationwide community of real, strong womxn. It's a magazine that is 100% all womxn, which is beautiful in its rarity - the magazine is a safe space FOR womxn ABOUT womxn. Created by Adrianne Ramsey, it serves as a content destination for multigenerational womxn. Read on for an engagement of feminist voices and a collaborative community for independent girls to discover, share, and connect. The usage of the terms "girls" and "womxn" refers to genderexpansive people (cis girls, trans girls, non-binary, non-conforming, gender queer, and any girl-identified person).

Front and Back Cover Image: Installation view of Artists’ Books as Prompts for Discourse at Center for Book Arts, October 6 - December 16, 2023. Photo by Oswaldo García

GIRLS first began in 2017, doubling as a final project in my senior year of college and a response to Donald Trump’s inauguration. Initially, the magazine had a heavy focus on politics. Looking back, the tone is sharp, direct. You can really feel that artists were anxious to make work about identity politics and the impact of timely events on society! We wanted change! We wanted to storm the streets! And in many ways, we’re still fighting, if not more Heightened geopolitical tensions, a looming presidential election, and concerns relating to our judicial systems has everyone on edge. I can’t believe we’re in for the third Trump presidential campaign in a row, as I write this, the jury was just selected in Trump’s hush money case - aka the first criminal trial of a U S president It would be remiss to act as if there aren’t troubling times ahead

GIRLS 20: The Last Text is a very special issue. Not only does it mark GIRLS’ seventh year anniversary, but it also signals a new beginning. This is the last issue of GIRLS Magazine! Even writing those words feels weird, but I feel strangely at peace with the decision The fact that this is the twentieth issue makes it even sweeter Interviewing 94 participants over 20 issues is an incredible milestone that I don’t take for granted. One of the greatest feelings is when someone you really want to interview agrees to talk to you. I’ve really appreciated learning about new people, discussing art, and expanding my thinking through interviewing, but it’s good to know when to take a break Interviewing is fun, but putting together a magazine on my own is a lot of work!

Fortunately, I’ve decided to evolve the company and produce a different type of content: printed books!

I’m excited to announce that GIRLS will launch a series of collaborative publications, each focusing on recent bodies of work from a single femme identifying artist By experimenting with various mediums – artist’s books, chapbooks, and zines – as sites for art and discourse, this inaugural series commits to providing a platform for experimental artists to document crucial moments in their practices and discuss the processes behind their work. The first publication will be a printed book about Disease Tour: Stage One (2024), a performance art film by multidisciplinary artist Xirin, who participated in GIRLS 5 This new work was featured in You’re Gonna Love Tomorrow, a group exhibition I recently curated for Fellows of Contemporary Art (FOCA) in Los Angeles. The book will feature stills from the film, writing from myself and Xirin, and a guest essay from Eve Arballo, who currently works at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York. In 2024-25, support for GIRLS is provided by Southern Exposure’s Alternative Exposure Grant program.

GIRLS 20: The Last Text features interviews from art writers and publishers, with intersections in curation and art making. Biggest thanks to Ali, Lydia, Nahui, and Vivian for participating in this issue and for allowing me to learn more about your practices! And thanks to all who have participated in, read, and supported GIRLS over the years – all the love means more to me than I can even explain.

Nahui Garcia is a writer and curator based in Los Angeles. In 2022, she earned her MA in Curatorial Studies and the Public Sphere from USC’s Roski School of Art and Design. Her thesis centered around two pioneers of Latin American feminist art: Mónica Mayer and Lotty Rosenfeld. Prior to Roski, Garcia worked as the Program Coordinator at Museo Nacional de Arte in Mexico City, where she organized panel discussions, workshops, and symposia on early 20th-century art. Garcia most recently worked as a Curatorial Assistant for Nour Mobarak’s exhibition Dafne Phono at JOAN Los Angeles and as the Development and Research Associate at Project X Foundation. In her work as an independent curator, Garcia is the 2023 recipient of the Fellows of Contemporary Art, Curator’s Lab.

Photo by and courtesy of Yuchi Ma

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in April 2024.

GM: What was your path to being a curator and arts writer?

NG: My professional journey into curation and arts writing began in 2018 at the Museo Nacional de Arte, where I assisted curator Alivé Piliado with the renovation of the museum’s permanent collection. I had recently completed USC Dornsife’s undergraduate art history program and felt a strong urge to return to Mexico, the country where I was born and spent most of my childhood. For my undergraduate thesis, I studied the portrayal of Indigenous and African subjects in eighteenth-century paintings, some of which were on display at the museum. I couldn’t think of a better place to be after undergrad. Shortly after joining the museum, I was offered and accepted the role of Program Coordinator. While I greatly enjoyed my time in the curatorial department, researching artists like Jose María Velasco, I didn't see myself as a curator yet. This was due to the lack of role models who shared similar backgrounds to mine or looked like me. This experience taught me that public programs could expand an exhibition without repeating the same discourse, creating different avenues for approaching an artist or work of art. In hindsight, I'm thankful for these experiences, as they motivated me to pursue the graduate program in Curatorial Practices at USC Roski. It was through these hands-on experiences that I was able to discern my career path.

GM: Why did you highlight the practices of Mónica Mayer and Lotty Rosenfeld for your master’s thesis?

NG: When I began my master's program at USC, I wanted to broaden my knowledge of Latin American art beyond the visual culture of the continent's colonial period. I had a keen interest in feminist art practices and text-based works, which steered me toward Mónica Mayer and Lotty Rosenfeld. In the 70s, Mayer began a project called En Tendedero (1979 - Ongoing), where women anonymously shared their experiences with sexual assault on pink slips of paper. These notes were then displayed on a clothesline within Mexico's Museum of Modern Art. Rosenfeld, a member of the Colectivo Acciones de Arte, wrote the slogan NO+ (1983 - Ongoing) on poster boards and walls to protest against Augusto Pinochet’s military coup in Chile. From my viewpoint, both of these works have had a lasting impact over the decades, which I find truly inspiring. For instance, NO+ has become a slogan frequently used in feminist protests across Latin America, demonstrating its adaptability beyond a dictatorship context for other causes. The more these two works are known and reproduced, the more they become enduring strategies of subversion. I find the concept of writing as a subversive tactic absolutely fascinating.

Installation view of In the depth of the mouth inhabits the light that takes shape at Fellows of Contemporary Art, January 28 – March 11, 2023. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber

Installation view of Minor Gaps Between at Human Resources, Los Angeles, January 20February 4, 2024. Photo: Andrew

GM: You’ve recently curated exhibitions that investigate language and translation through art. Could you speak about your experiences organizing these shows and how you came up with the themes?

NG: As a native Spanish speaker who learned English upon moving to the U S , my fascination with language is deeply personal. The author Jorge Luis Borges deeply influenced my views on this subject. I distinctly remember a 1968 interview, where Borges discussed the difference between reality and illusion. He argued that language has the power to transform and bring the fantastic into existence, treating words as mystical spells that can conjure reality. This perspective inspired in the depth of the mouth inhabits the light that takes shape, an exhibition I curated for Fellows of Contemporary Art (FOCA). I invited three talented artists, Jiayun Chen, Elizabeth Ibarra, and Yuchi Ma, to contribute. The three of them moved to the U.S. at different stages of their life and explored language from their unique perspectives as ESL speakers. This experience is emblematic of Los Angeles, a city predominantly comprised of immigrants, and a topic I am eager to delve further into. More recently, I curated the exhibition Minor Gaps Between at Human Resources. While not all of the participating artists explicitly focused on language, what united them is the shared desire to break free from the cyclic patterns that confine us, to find that gap in our reality from which we can escape into another. Language offers a path for transcending these limitations.

GM: You have written exhibition reviews for several publications, and contributed research to exhibitions at JOAN and MOCA. What draws you to a project, and how do you support?

NG: I am drawn to projects that expand my understanding of Latin American art and visual culture. During my time at JOAN, I supported artist Nour Mobarak in the development of the exhibition Daphne Phono, which gave me the chance to delve into complex languages, such as Silbo Gomero from the Canary Islands and Chatino from Chiapas. This was a truly rewarding experience, as it expanded my perception of language beyond English and Spanish. With MOCA, I researched and wrote about Mexican-American photorealist painters for an upcoming publication, set to be released toward the end of 2024, which I am quite excited about. This experience introduced me to artists outside of my usual sphere of knowledge. At the same time, I enjoy shining a light on the contemporary art scenes in Los Angeles and Mexico, often through exhibition reviews. When I choose an exhibition to write about, it’s really important for me to understand and convey the intention of the artist(s), while also developing my own opinion. While it may seem apparent, we inhabit a world where most concepts and ideas are viewed through a Western lens. I don’t want to repeat these patterns - I want to see the world how artists see it first.

GM: What are you working on now?

NG: I'm currently involved in research work for a publication with Carolina Caycedo, who will be exhibiting her work at the Vincent Price Art Museum as part of the Getty PST ART: Art & Science Collide initiative. Although the project is nearing completion, it has been an invaluable learning experience in understanding the extensive work required to put together a major exhibition. On a more personal level, I am currently focused on developing my writing skills as an art critic. This involves actively participating in writer's workshops, diligently noting observations from every show I attendregardless of whether I intend to write about them - and committing to a daily reading routine. Maybe that’s a bit manic on my part, but I enjoy being dedicated to my work and immersing myself fully in my pursuits.

Ali Pinkney is a woman writer, educator, editor, and literary curator with an MA English Literature in the Field of Creative Writing from the University of Toronto (2023), an MA English Literature, and a BA Honours English Literature and Creative Writing from Concordia University (2021, 2017). Ali's literary training has been amplified by her participation in Filip Marinovich's Shakespearean Motley College based out of New York (2020 - Present) and through residencies with The Homeschool Hudson (2019) and The Banff Centre (2018). Her University of Toronto thesis work in experimental poetics was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research

Council Canada Graduate Scholarship and an Avie Bennett Award. Her research on Percy Bysshe Shelley and 19th century philosophies was supported by a fellowship with the Faculty of Arts & Sciences, her year's Steinberg Scholarship, and her year's David McKeen Award for top creative writing at Concordia University. In 2023, Ali served as the managing editor for Echolocation Magazine vol. 21, and curated "The Spirit is a Bone" for Metatron Press's Glyphöria. Ali works as a sessional instructional assistant at the University of Toronto, reads slush for Coach House Press, performs her work semi-frequently, and runs the poetry carnival Calliope with Marie Ségolène. She has taught at St George, UTM, UTSC, St Michael's College, Innis College, and Concordia University in a wide variety of subjects related to the literary arts, creative writing, and media studies. She was previously the assistant to the director of Concordia’s literary reading series, and a research assistant at both Concordia and McGill Universities. In May 2024, she will give two workshops on the relationship between abstraction and apotheosis in poetics as part of the programming for the triennial GTA2024 exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in T’karonto/Toronto.

Photo by Andrea Iya YoungThis interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in March 2024.

GM: You are an art writer, with a focus on experimental poetics – what led you to this career?

AP: The literary arts gelled as the career field of choice for me through two discreet inclusions. One was an inward cataclysmic minute that occurred during my initial office hour with my first mentor, Sina Queyras, at Concordia University in Tio’tia:ke/Montreal when I was nineteen. A month or so before that point, Sina had billed me as the featured undergraduate student to read my own poems at a prestigious event. Soon after, Sina had offered a place in Lemon Hound to publish a weird poem, called Oskorei, that I had written for their class that fused a critique of the Academy Awards with Norse myth I write of these points of context around the minute or so of significance in the office, because these were gestures from a unique authority figure that spawned my belief that there was something veritably distinctive in me, and these proofs allowed me to trust in a salience around Sina’s belief in me as a talent beyond the generically bestowed sense of belief a good professor will cascade to all. It was a cataclysmic moment as I was overcome with a vacuously abyssal sense that they could teach me something big and valuable. I did not know what yet, but this sense was strong enough that when I was in that chair, I was debating whether to turn down offers to the directorial theatre programmes I had prepared towards for years I recall also half-articulating to Sina my itch to flee to Iceland to verify a self-involved theory that some people were descendants of elves. That was the moment I knew I was going to veer course and stay in the creative writing programme instead of leaving to pursue my outdated dream. The meaning around me shifted, even though I was already in place. It was one of those moments that felt like an immense life-changing card was in play – because it was I experienced it as a releasing destruction of what I thought I was doing with my life, to clear the way for what I was doing. Now that I teach creative writing and literature to undergraduates at the University of Toronto, in T’karonto/Toronto, I experience the trapeze-privilege of being on the other side of the desk. Those late teenage years can be a very intense time in a person’s life. Being femme in the academy, I’m finding too can register with a very maman effect on students.

GM: That’s such a fascinating timeline – when did the second inclusion come to you?

AP: A couple years after the first I’m twenty-one, outside of a Safeway in Winnipeg, Manitoba I ran away that summer with the intention to elope! I am there so I can access the grocery store’s open Wi-Fi signal on my laptop, but am reading the introduction to a collection of works by Québec-born, France-expat writer Mavis Gallant. Some sentence or other inspires me, I cry tears of inspiration, feeling allied in my experiences through the text, and I sign the flyleaf of the book with a pledge that I will be a career poet, no matter what This flyleaf signing was inspired by another mentor I had, Trevor Ferguson, though he’d signed a Bible. In both these moments, you can see a sense of how seriously I took everything. If I could have lightened up, believe me, I would have!

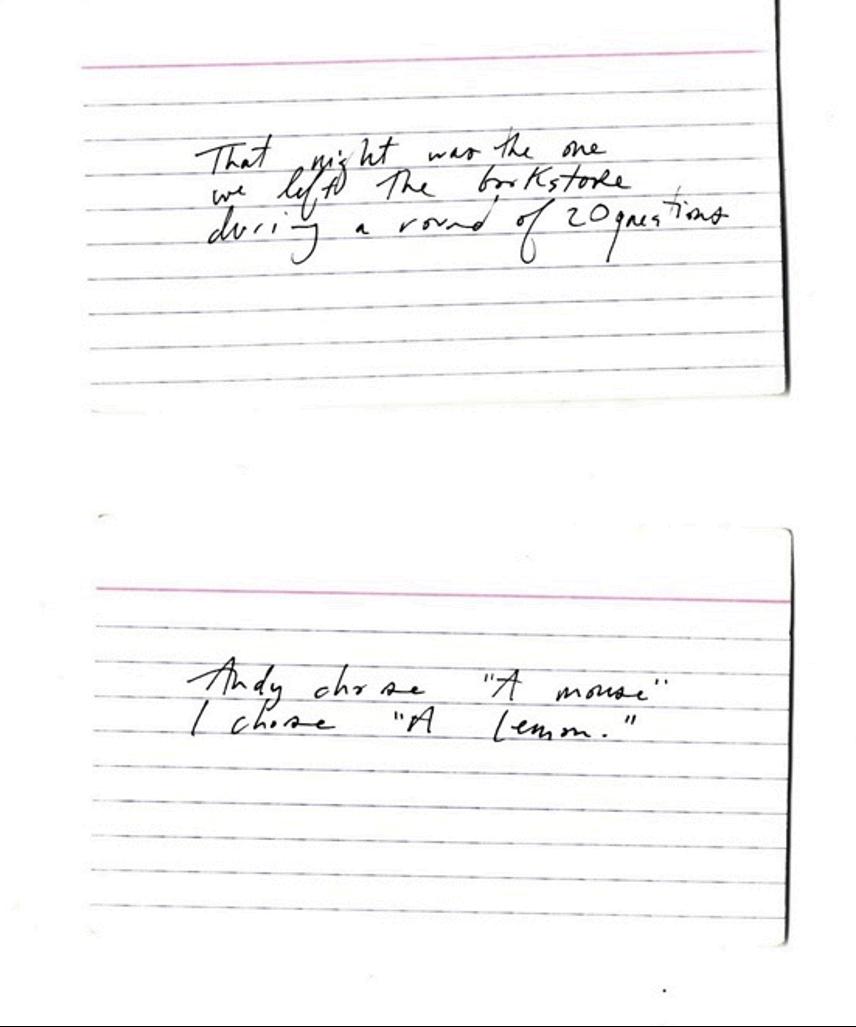

Excerpt from Ali Pinkney, Cue Cards

Project: Assiniboine, Nosedive, Fog (2012)

GM: In 2022, you co-founded Calliope, a traveling poetry carnival, alongside Marie Ségolène. How did this series come to fruition?

AP: Fine grapes! Have you ever tried a dark, vineyard grape off the vine? Unfathomable! Marie is one of the most stem-winding, spell-binding artists alive today. She’s a visionary who twists power out of intimate, vulnerable presence. Her work ethic bleeds an exacting and daring sense of life direct from her heart, wetting the soil of the bleeding edge of arts and culture in Montréal for many, many years. It has been this way since I met her in Sina’s poetry class in 2010. She was already running transgressive art collectives [that were] practicing in hotel rooms and shepherding together some of the most eclectic talents in Montréal into elegantly confected soirées, like holy lambs. Marie is a gifted curator who inspires that same raw power, vulnerability, and sense of play in others through what she brings to her own work Marie and I have collaborated on a variety of projects since we met That’s fourteen years and counting, and each has been a privilege. I love her. I love her performances. I love her poetry. So, Calliope erupted naturally out of a long-standing working relationship. God bless Marie Ségolène! I’m kind of the hermetical nerdy freak librarian sidekick of Calliope. My background in theatre and extensive time in books serves us well

GM: Calliope hosts readings, performances, and happenings – why is it important to feature an eclectic array of programming?

AP: The expectation for poetry to be shared in dive bars on Monday evenings or within lecture theatres backed by institutions is usually crotchety and lame, and even those events had kind of dried up in Montréal in 2022. We wanted to raise the standard of expectation so we could see poetry being shared in environments drenched in their own erotic, excessive, chthonian, Dionysian spirits Our readings aim to balance the highbrow world of gallery exhibition; extravagant, black tie, costume party dressing; and fine, elevated/atelier dining, with the quotidian accessibility of something written in eyeliner stick on a napkin on a dashboard and kissed – country radio blaring – scent of manure and hay through the window. It’s about what’s near to the wild heart, what’s urgent What I love most about the series is finding secret poets like baby horses, or uncovering people who have hidden their work away from the thousand eyes for many years, like older horses resigned to their stables. We really aim to have people of all ages reading. Not just the twenty-year-old latest-in-cohort from the creative writing programmes, or career writers whose names can be plucked from recent flyers and awards lists I think of our curatorial process as putting jumpers on a carousel for an evening – coming to Calliope should feel dizzying. We intentionally minimize the institutionalized presence in our hosting as part of our effort to make it all feel like entering a rotating theatrical fun house of poetics. When we experience the uncanny live, we are confronted with our capacity to inhabit the pure medium of relation in its complete plasticity Minimize mediation, I say! (Continued)

Performance documentation of Calliope at Espace LouLou (March 4, 2023)

Without integration into this dizzying fluid, this heated substrate, we are egg-hatched and lizardly, recalcitrant and plastered. Calliope is warm milk straight from the breast. I saw Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (1985) recently for the first time, and the white suited lovers have Calliope’s vibe. Referring to that couple would be the niche elevator pitch for the series.

GM: As both you and Marie are based in Canada – Toronto and Montréal, respectively – what do you hope Calliope contributes to the local arts and culture scene?

AP: I’d like to think the effects of Calliope have started to occur, but I’m sure part of this sense is self-flattery. The other part is the overwhelming public feedback on the streets I’ve received after we host an event, as well as the turnouts. We have hosted six: Bon Service and Honey’s Brooklyn (2022), and Espace Loulou, No Gallery, M. LeBlanc, and Pangée (2023). For the two Montréal iterations I was present for, I’d stayed in Mile End with close friends. The days following the events, I was met with gushes about new senses of inspiration from people I ran into who’d gone, or seen, or heard, so that felt like a good sign, as if we have been revealing salamanders in the ecosystem’s depths. I do not think Marie and I have been alone in our thirst for elevated and femme poetry cultures, as I have seen a rash of new DIY events sporulating from around 2022 onwards that are more liberated in how frequently they may or may not occur. This was our ultimate hope with creating the series, so whether we helped to see an already-incoming revival of an exciting DIY poetry culture or not, I’d like to think we did. Calliope is a little different because it is fifty/fifty poets/performance artists, but each of these event series has something uniquely its own. Calliope’s uniqueness is the performance art in combination with the circus energy, the gallery spaces, the wines. It’s an immersive and highly curated experience of food, atmosphere, and fancy dressing; we travel like an old theatre troupe and curate the bill to create a sense of said troupe, meaning we have performers we bring with us from Montréal to New York, come back home again. Speaking from experiences running academic-oriented event series and performing my own work, repeating performers is radical/taboo in literary event hosting, and with good reason. But also, from my experience in the DIY culture from which Metatron sprang, repeat performers allow for a strong sense of community and familiarity. A scene emerges, and there’s a huge precedent for this in contemporary poetry. (Continued)

Performance documentation of Calliope at No Gallery (April 27, 2023)

I would argue that featured performers linked to a particular aesthetic and curation is healthy for the proliferation of a scene. I understand why series rightfully avoid this, and we believe in variety. Our programming and curation reflect this too, but I’ve also heard a lot of worries of seeming nepotistic while working on other boards. But what if the movement is a cultural production, and what if that performer is simply excellent and is prolific? Take them on the road, like a band! Something else that Calliope does in a vein that I think is vaguely radical is that we operate without a fixed schedule pattern. There’s a sense of freedom in that, and the events are announced as if they are surprises and roll through accordingly. I hope this sporadic energy shows others they can throw poetry parties without full schedules and formal funding – but I also hope we receive funding in the near future!

GM: Who are some authors/poets that inspire you to continue writing and researching?

AP: My current focal manuscript-in-production is Osedax. I believe that for me, it will be what The Besieged City (1949) was for Clarice Lispector, in that most found it indecipherable and highly architectural; she worked on it for twenty years or so. The Besieged City is currently my airless dove as I move through my Osedax. Hoa Nguyen inspired me to work on that manuscript, which was also my thesis, in a visceral way in its neonate stage, which let its contents surprise me and get gory. I’ve been in a careful scrubbing phase with it. […] At present, I am reading Middlemarch (1871) by George Eliot, and its sentences are filling me with sheer delight and remind me that the erudite way I write my literature will stimulate people like me who need a certain level of stimulation to feel something from a book.

Lydia Rosenberg (b. 1987, Pittsburgh, PA) received her M.F.A. in

Interdisciplinary Art from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Her work, primarily in sculpture, is concerned with the impact of language on our perception of the material world and the ways that narratives shape value systems. Recent exhibitions include Lamp Store, Here Gallery, Pittsburgh, PA (2023); Do this while I wait, Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh, PA (2023); ¿Cómo vivir de ahora en adelante? Getting as close as possible to the truth, Galería Barrios Bajos, Valdivia, Chile (2022); Spaghetti Restaurant, Basket Shop, Cincinnati, OH (2019); The Complete Subject, Napoleon Gallery, Philadelphia, PA (2019). Her recent exhibitions are part of an ongoing project of writing a novel-as-sculpture in which the text centers on objects and prompts the creation of installations and events which recreate and complicate the fiction. She is a co-founder of Anytime Dept. a now on pause artist-run exhibition project based in Cincinnati, OH.

Photo by Jared MillerThis interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in March 2024.

GM: What was your path to becoming an artist?

LR: I have always been moved by art and spent most of my childhood and early adolescence trying and quitting all the art forms, thanks to encouraging parents and an idealistic humanities focused phase in the funding of public education during the early 1990s. I’ve pretty much continued on that trajectory into adulthood. Between the schooling periods of my life and working jobs I happened into, I would try to imagine what useful work I could do in the world if I left the notion of needing to be an artist behind. Because of my art research, I knew I was interested in different things, so why not just become one of those things and have a more direct relationship to it all? I’ve finally started to see my art practice as this catch-all for my interests; that if I want to learn about something in the world and if I want to test some of what I am learning out, I can do that to a pretty high level of personal satisfaction through my artmaking. I could incorporate these subjects, learn about them, and apply that knowledge in experiments in the studio. I’ll never be a leading expert in any of the subjects I dip in and out of, but I can be an expert in my own discovery of them. Misunderstandings of what I learn create little pockets in my practice that seem to open up spaces for others to enter the work.

GM: How did you discover art mediums that ultimately interested you?

LR: I grew up in Pittsburgh, going to museums a lot and doing student jobs and volunteering. I was exposed to a wide range of what art could be, between the Carnegie Museum of Art and its serious collections of the artistic canons, to the Andy Warhol Museum and the general Warhol legacy/infatuation that the city clings to, and of course, the Mattress Factory Museum, which must be where I initially discovered that art can really be almost anything I decided to go to art school for college and began with early interests in mythology and puppeteering. After undergrad, I worked retail and service industry jobs, did studio and project assistance for artists, ran a little artist-run conceptual/curatorial project with another artist friend, and tried to stop thinking about what I should make! But sure enough, a $80/month shared studio space opportunity that I had little intention of working in led to a body of work that led me straight to pursuing my MFA. [This further] led me to avoid making work again and running another artist-run curatorial/event collaborative project, which ultimately led me back to making my own work again I guess it's all just part of it, the stopping and starting. I will say that one of the main reasons I continue to work is because of the incredible artists I have met everywhere I have gone, who open up new worlds of ideas and possibilities for sustaining this sense of purpose and inspire me to see the endeavor as life-long and patient.

GM: Your work has been described as “an exploration of the interplay between language, narrative, and everyday objects ” What is it about the connection between linguistics and ready-mades that excites you?

LR: I like to think about what language is doing to our understanding of material experience and vice versa. I am enamored with instances of language failing to capture the totality of an experience and the ways that objects elude even our best attempts to describe them in words Language sits in this strange space of being and approximating, meaning that language (in this case, commonly agreed on systems of forms that represent processes and materials, sensations, etc.) is “real.” It’s kind of a living and evolving thing, which is trying to capture elements about life and the living through approximating or relating, often through the use of metaphor In college, I read Metaphors We Live By (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980), and it left a mark on my understanding of how language has developed as this companion to our understanding of physical phenomena. They cite numerous examples of metaphors that utilize spatial and container concepts to express physical phenomena, often relating to emotional responses that are built into the meaning of our words These ideas, [coupled with] learning about the history of literacy, mnemonic devices such as the well-studied memory palaces which taught orators to memorize a text by mapping it onto architectural sites, and using symbols in the architecture as anchors for the key points in the narration, all contributed to my curiosity about how these two modalities were working together and against each other, towards the goals of society [ ] I get a little stuck in art-form-as-discipline in spite of my entirely interdisciplinary education and community. I am someone who thinks a lot about what a sculpture is, so what is the distinction between art objects and non-art objects? [Marcel] Duchamp presented one of the problems of objects, which is that through value systems (of which language is a participating system), anything can be a symbol for anything However, as a self-identified sculptor, I have really been fascinated with how a sculpture is just another object that has a strange way of being both an artwork and a real thing in the world of real things. To me, sculptures don’t have the same suspension of reality that paintings or films can have They are bound by the physical laws of everything else, thus the process of making something three dimensional that is conceived in the imagination has to be built according to the physical rules of the world of material life. I think that’s such a strange endeavor to be involved in.

GM: In 2019, you began your novel-as-sculpture series, which has included interventions at numerous art spaces. Why did you begin this project?

LR: Before starting this project, I worked with texts I was already reading. I was interested in the impression that a powerfully resonant work of art can leave on a viewer, and similarly, with any kind of visual experience which generates that kind of sensation in a person. For example, after reading a poem that strikes a chord, how does your perception of your environment change? Phenomena like Baader-Meinhof, where you learn about something you weren't previously aware of and then start to see it everywhere, are similar to what I am interested in (Continued)

[…] In 2019, I was invited to be in a show in Cincinnati, where I was working as an adjunct and running a project space I had not been making or showing work since grad school, and I wanted to make some new work I was reading this lecture by Robert Creeley, Some Senses of the Commonplace, and thinking about the sculptures I was tinkering with. [They were] made up of little scraps of everyday life that I had been collecting for several years. I started to think about the book as an object, and the practice of working with readymades vs. the practice of sculpting objects that are copies of readymades What would it mean to make a novel as a sculpture? You would need a text first, then paper and printing technology, and some kind of binding structure. I started to write this novel, and I thought I would write it quickly, within a month, and just use whatever was there. I knew that I wanted it to center the lives of objects more so than developing characters Within a couple of days of the project, I started to recognize the idea as something that could be a kind of binding structure for my interest in language, objects, and perception, and decided to develop it as an ongoing project.

GM: When did you decide to incorporate audience participation into the project?

LR: For a long time, I felt my practice was missing a couple of elements. The first was an outlet for my own writing. My earlier work dealt so much with other people’s texts, weaving together resonant themes, but this work felt sometimes more like curating and illustrating a set of interesting ideas, rather than generating a network to map the ideas onto each other using my voice as the connective thread. The second was, for lack of a better word, a practice that functioned more like a world within which I could explore freely disparate interests and modes of working/making that could be inherently connected through the framework of that world. I started this inquiry in 2019 and am still very much in the middle of thinking about it The premise is that the text is where I generate the context and concept for the sculptures, installations, and events. It is a real piece of writing that is in several formats/drafts, some of which are released to be read while others are kept internal. Eventually, there will be a finished, bound text. The sculptures, installations, and events are written back into the text so that it is initially an imaginative laboratory and a record of the material/physical reality While there are characters, their narratives are incongruous and are made up of amalgamations of my own life, stories of friends, and stories/histories I have read. The main function of each character is to introduce the scenario in which the objects/sculptures are invented. It's been really exciting to work sequentially and to have this developing vision as a whole.

GM: As part of the latest iteration of this series, you turned Labor is a Medium, a project space in Santa Rosa, into a mail room. Why was this the new setting of choice?

LR: I was so excited to get to make that work for Labor is a Medium (LiaM), run by artists Daniel and Emily Glendening, who are friends from Portland, OR. That project came at a point when I had just finished two solo exhibitions that amounted to two new chapters of the novel project as sculptural installations, and I needed to spend some time collecting and structuring the work. (Continued)

Lydia Rosenberg, Incomplete Objects, 2023, Santa Rosa CA. Photo by Perry Doane, courtesy of Labor is a Medium

In 2019, I did the first two projects, The complete subject, at a space in Philadelphia, where I made several hundred lemon sculptures [that were] made to be models of written descriptions of lemons in still life paintings. Later that year, I made the first iteration of Spaghetti Restaurant at BasketShop gallery in Cincinnati, a project I intend to revisit at irregular intervals as the larger novel-as-sculpture continues Then in 2023, I did a project at Mattress Factory Museum, Do this while I wait, and later that year Lamp Store at Here gallery in Pittsburgh. Each exhibition has been a new opportunity to consider the project from different angles, so when I had this project come up with LiaM, I needed to have it be something that helped me tackle this sort of early survey of the project at that moment. […] During 2023, I also started a new job working at a library with historical publications and relearned the story of how early books were often printed serially to lower the cost burden for both the customer/subscriber and the publisher. When I saw some of these early serially printed works at my job, it reminded me of an artist whose work I had cataloged for a collector I previously worked for in Cincinnati, Mail Art participant David Zack. I was fascinated by his serial mail-art subscriber-specific Correspondence Novel By building off of my own developing serial process and these historical anchor points, I decided that the gallery/garage space would be the mailroom at the publishing house that was going to be delivering these serial teaser chapters to various readers or editors.

GM: How did you decide the final exhibition design?

LR: I was inspired by Daniel Glendening’s drawings of artworks and thought I could make a drawing of documentation of the four chapters as a title page to the chapters themselves. I was thinking about courtroom sketches and how that could apply to exhibition documentation. Each of the four previous exhibitions became a drawing affixed to a comically large envelope. Then, for each week of the LiaM exhibition, the chapter text was added as a transparent layer on top of the drawings Anyone who signed up for the mailing list would receive some version of that chapter text via post. It gave me these short and strict deadlines to explore different forms in the texts themselves, and to externalize some of the writing, which had been mostly out of view until that time. I wanted people to return the chapters to me with edits, but no one really did that. I think it's still too early in the process for coherent criticism. That was really the first time I shared the writing component publicly outside of some very early experiments with the first project

GM: Do you think that your novel-as-sculpture will always be a continuous project?

LR: I was just speaking to a friend about this and we agreed that it could be a project as long as it needs to be My vision for it is much larger; I don’t feel its winding down at all, but nothing is forever I would like to finish it one day, as I really want the satisfaction of the bound book at the end. Plus, there is an endless storage unit containing all of the material stuff of the chapters that are made. I can see it becoming a little bit administratively complicated, and I find that interesting. I’d love to see it all together – all of the objects, ephemera, and the book itself -- someday in one space

Vivian Sming (she/they) is an artist-publisher who experiments with books as art, discourse, exhibition, and archive. Since 2017, Sming has published a wide range of artists’ books through their studio Sming Sming Books. They work in close collaboration with artists whose works and ideas inform design, material, and printing choices. Sming is committed to promoting critical discourse, advancing cultural equity, and creating alternative sites of knowledge production through publications and public programs. Their books are publicly accessible in over 150 libraries worldwide, and have been featured in aperture, Art in America, BOMB Magazine, Hyperallergic, and The New York Times. Sming Sming Books has received Printed Matter’s Shannon Michael Cane Memorial Award, a San Francisco Art Book Fair Publishing Grant, and Southern Exposure’s Alternative Exposure Grant. Sming holds a BA in Art from UCLA and an MFA from CalArts. They were previously a Fellow at YBCA, Curatorial Fellow at the Letterform Archive, and Guest Curator for the Vancouver Art Book Fair’s programs. Sming is currently the Associate Director of Academic and Public Programs at Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University.

Photo by ThreeThis interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It took place in March 2024.

GM: Before I talk about your publishing career, I wanted to highlight that you are an artist! Why did you become an artist and what is the core of your practice?

VS: I don’t get asked this question a lot, so thanks for asking! I initially gravitated towards art because it was really the only thing I could do. I wasn’t interested in anything else and had a hard time in school. I wasn’t particularly great at making art, but it kept me going. My mind was, and still is, always preoccupied. When I got to college, I realized that through art, I could channel that thinking into something productive. I definitely relate to artists who create art out of necessity, for one’s own mental stability and survival.

GM: You’ve often referred to looking at the book as a form, an archive, and sculpture. Why is the physical structure of such interest to you?

VS: It’s the immaterial aspects of the book’s physical form that is of interest to me. I’m drawn to sound, performance, dance, and time-based works. With the book form specifically, there’s a way to capture or replicate some of that ephemeral nature into this very immediate form. Having this physical form is one way of slowing down in relation to the experience of being oversaturated by the Internet. I talk a lot about what a book can perform, as an artwork performs. It’s not necessarily that kind of informational, content-driven, post-after-post way of understanding material, but something that’s tangible and directly relates to the body.

GM: How did Sming Sming Books begin?

VS: Before Sming Sming, I was involved in a lot of other publishing projects. Alongside my friends Páll Haukur and Alice Wang, I started nonsensical, which was an annual journal of art writings by visual artists. With Heisue Chung-Matheu, I created another publication, from shore to sea, that featured interviews and photo-based works. I learned a lot from those experiences - what to do and what definitely not to do. By learning and failing and learning again, I was able to bring that knowledge into Sming Sming.

Installation view of Artists’ Books as Prompts for Discourse at Center for Book Arts, October 6 - December 16, 2023. Photo by

GM: What does a collaboration between you and the artist/author generally look like, and how do you decide who you’d like to work with?

VS: It’s totally a case-by-case basis! When I first started, I reached out to artists that I loved who did not have books of their work. From there, friends and other artists started reaching out with their ideas. When I reach out to someone, it can take a lot longer because they may not have had a book idea already, so we have to generate that. Whereas when people reach out to me, they usually have a specific book idea in mind. I start by asking artists to first gather all of the materials and artwork within the book. From there, we generate ideas, inspiration, and related material. We narrow it down from there, based on what is possible or what the desired outcome is for the book. There are some artists where the sequencing is already finalized, but for others, I’m creating that with them. Some artists trust me to do whatever I want, but there’s usually still a lot of back and forth. It really just depends on what that particular artist needs.

GM: You’ve recently worked an exhibition for the Center for Book Arts and a collaborative bookshop with Heesoo Kwon, a participating artist in the Bay Area Now 9 Triennial at YBCA. How did these projects come to fruition?

VS: As a form, the book is an antithesis to the exhibition space – or rather, the book is already its own contained exhibition, so it’s funny to put the book back into the gallery space. I don’t know that it always works! But I’ve been excited to think about how books can exist spatially in a gallery. With the Center for Book Arts exhibition, I created an installation on one of the walls as a reader in progress. I attempted to look up everywhere the books I’ve published had ended up –in essays, as examples in dissertations, or citations in blogs. I tried to trace the thread of the life of each book. When Heesoo Kwon and I started working together, it was initially for a book that encompassed her project Leymusoom, which is a feminist autobiographical religion. Heesoo creates what she calls “digital utopias” that reimagine archival materials to free her ancestors from patriarchal systems. She had this opportunity at YBCA at the same time, so we decided to fold the book project in. We created an installation in the form of a religious giftshop that sells postcards, prayer books, bookmarks, and bibles.

Heesoo Kwon, Leymusoom Giftshop, 2023. Courtesy of Sming Sming Books

GM: You wear many hats – your artistic practice, publishing house, and new job as Associate Director of Academic and Public Programs at the Cantor Art Center. How do you stay balanced?

VS: I always ask myself, “How am I doing this?” (Laughs) I don’t have an answer for how to best manage multiple jobs and projects. I’ve been (jokingly) reprimanded before for saying this by people who know hard I work, but I am actually very lazy and don’t have a lot of discipline! I love taking breaks and doing nothing. (Laughs) When I think about how I balance it all, at the core, it is about prioritizing and not being a perfectionist. I still care a lot about quality and have a level of standard for my work, but I’ll let it go at a certain point. Books are ultimately handmade. It can seem like they’re made by machines, but they’re not. Even at a large printer, there are people every step of the way who are setting up files, trimming, gluing, or binding, and because of that, there’s always something that’s going to happen. I’ve had to ask myself many times, “Do I need to reprint this book, or is it fine? Is this error going to compromise the work?” There’s an environmental impact to having to fix something. Most of the time, I will notice something, acknowledge it, let it go, and move on. I take this learning with me to work as well. Everyone makes mistakes. It’s about focusing on the things that truly matter. The lack of perfectionism helps drive new projects forward. The final thing I would say is that I give myself a lot of leeway. I let myself work at the pace that I can. My life is pretty chaotic at times, but I’m making it work.

THE LAST TEXT