We’re delighted to announce the Portuguese Air Force now joins the Brazilian Air Force as a C-390 Millennium operator. The first Portuguese aircraft of the newly formed 506 Squadron is now in service at Beja Air Base, with four more aircraft to be added in the near future. A growing number of countries are choosing the C-390 Millennium (including Hungary, Netherlands, Austria, Czech Republic and South Korea) attracted by its unbeatable combination of technology, speed, performance and multi-mission capabilities. Hungary will take delivery of their first C-390 Millennium in 2024 – another milestone for an incredible aircraft that has already achieved 10,000 flight hours with the Brazilian Air Force. #C390UnbeatableCombination embraerds.com

Editor Simon Michell

Project Manager Group Captain Paul Sanger-Davies, Director of Defence Studies (RAF)

Editorial Director Barry Davies

Designer Ross Ellis

Managing Director Andrew Howard

Printed by Micropress

Front cover image: AS1 Natalie Adams (RAF)

Published by

Chantry House, Suite 10a High Street, Billericay, Essex CM12 9BQ United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 1277 655100

The battle above: integrating and assuring UK space capability into multi-domain operations

Major General Paul Tedman CBE, Commander of UK Space Command, highlights the urgent need to enhance the UK’s ability to ght in and from space

Deterrence is so much more than just a big stick Air Marshal (Retd) Greg Bagwell, President, Air & Space Power Association

Number 1 Group – integrating the front line

Air Vice-Marshal Mark Flewin, Air O cer Commanding Number 1 Group, highlights the progress that has been made to integrate the Forces under his command to make them more interoperable and enhance their ability to deter and defend

Ingo Gerhartz Chief

Air Vice-Marshal Jason Appleton, Air O cer Commanding Number 2 Group, explains how the Group has reorganised to achieve more integrated and interoperable capabilities in an ever-evolving world

42

46

Agile basing – always operating and ready to y and ght

Air Commodore Ady Portlock, Commander Air Bases, explains how the ability to deploy quickly to, and operate from, non-traditional operating bases improves the RAF’s resilience and exibility

Operational agility through Agile Combat Employment (ACE)

Number 11 Group’s Deputy Director of Operations, Air Commodore Lee Turner, on how the RAF, its allies and partners are focused on becoming ever more agile

FCAS/GCAP

Air Commodore Martin Lowe, FCAS Programme Director, on the status of the Programme following the integration of Japan into the tri-national project

72

Responding to the threat environment

BAE Systems’ Herman Claesen reveals the UK’s commitment to maintaining a sovereign Combat Air sector through the Global Combat Air Programme

49

Australian ACE

Group Captain Michael Sleeman and Group Captain Trav Hallen of the Royal Australian Air Force highlight the importance of embracing Agile Combat Employment in protecting mainland Australia and projecting air power across the Indo-Paci c

75

77

51

RAF Global Enablement

Air Commodore Jamie Thompson, the RAF’s Global Enablement Commander, outlines the high-readiness and globally facing capabilities that his organisation provides

53 The importance of international partnerships

Air Commodore Nikki Thomas, the RAF’s Air and Space Attaché in Washington, highlights the importance of the close cooperation between the UK and the US

80

GLOBAL STRATEGIC PARTNER PERSPECTIVE

General Hiroaki Uchikura

Chief of Sta , Japan Air Self-Defense Force

Group Captain John Butcher, Commander of the UK’s Lightning Force, explains the importance of enhancing integration and increasing interoperability with other F-35 eets worldwide

Wing Commander Sarah McDonnell, Commanding O cer of Number 8 Squadron, explains the Joint Vision Statement signed by the RAF, RAAF and USAF to coordinate E-7 Wedgetail capability development, testing, interoperability, operations and training

82

56

GLOBAL STRATEGIC PARTNER PERSPECTIVE

Major General Juha-Pekka Keränen Commander, Finnish Air Force

57 Air power lessons from current operations

Air Vice-Marshal Tom Burke, Commander of Number 11 Group, considers the impact of current operations for UK Air Defence

Group Captain James Bolton explains how

by

ISTAR in the 21st century

Wing Commander Keith Bissett, O cer Commanding Number 51 Squadron, explains how the RC-135W Rivet Joint aircraft collects vital intelligence for NATO and its allies, and how Number 54 Squadron achieves such a diverse training task to meet demand for niche skills

83

Keeping pace with and deterring our adversaries

Andy Start, Chief Executive O cer, DE&S, and the UK’s National Armaments Director

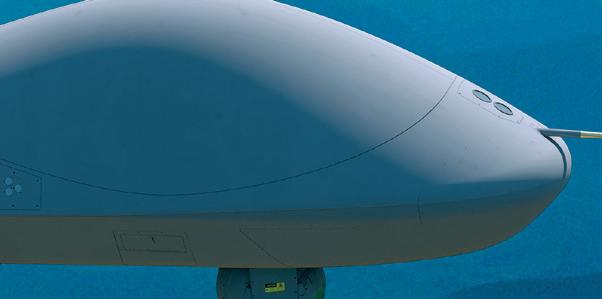

Protector arrives at RAF Waddington

Air Commodore Alex Hicks, Senior Responsible O cer for the Protector Programme, explains how the Test and Evaluation process will be carried out to ensure that the aircraft reaches its in-service date in 2024

86

Orcus – introducing C-UAS

Group Captain Gary Darby explains how the Orcus system ts into the UK’s future plans for counteruncrewed air systems integration and interoperability

88

Securing air dominance now and in the future

Chris Stevens, Group Head of Business Development for Air Dominance at MBDA, explains how MBDA’s air-to-air missiles are helping the NATO Alliance and others secure their skies

Enabling

Kevin

General

Cybersecurity in aviation

Air Vice-Marshal Alan Gillespie, Director of the Military Aviation Authority, explains the critical importance of new regulations to ensure that the Defence Air Environment monitors, assesses and mitigates the cyber threat to aircraft airworthiness and safety

106

Building the world’s best AI pilot

Mike ’Pako’ Benitez, Director of Product for Autonomy at Shield AI, reveals how the race to create arti cial intelligence (AI) pilots is already well underway

Building air autonomy

Air Commodore Christopher Melville, Head of the RAF’s Rapid Capabilities O ce, explains the operational roles of low-cost, high-performance ‘disposable’ swarming drones and how they will integrate with other frontline capabilities

Harnessing emerging technology

Cecil Buchanan, the RAF’s Chief Technology O cer, explains his approach to embracing and prioritising the spectrum of current emerging technologies

Digital transformation

Dr Arif Mustafa, the RAF’s rst Chief Digital and Information O cer, talks about how he has overseen the Force’s Digital Capabilities Modernisation and Transformation Programme

110

Celebrating a century of excellence – RAuxAF 100

Air Vice-Marshal Ranald Munro, Commandant of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAuxAF), describes the key activities taking place to celebrate its centenary

RAuxAF 100 – supporting the ISTAR vision

Group Captain Ryan Mannering and Squadron Leader Becky Kirk from the RAuxAF set out the RAF ISTAR Force’s vision for a more agile, responsive and exible approach to the employment of Reservists

Training – a vital part of RAF war ghting capability

Air Vice-Marshal Cab Townsend, Air O cer Commanding Number 22 Group, highlights how introducing innovation into its training pipeline will improve the RAF’s integration with other air arms

114

Next-generation recruitment and retention

The RAF’s Director People and Air Secretary, Air ViceMarshal Simon Edwards, highlights work to ensure the RAF maintains its e ectiveness through e cient and meticulous recruitment and retention

117

120

Cross-skilled aviators: the key to enhanced agility

Air Vice-Marshal Shaun Harris explains how the RAF is planning to cross-skill its aviators to ensure it can deliver ACE e ectively using the RAF Whole Force

The fast and the furious: an agile war ghting culture

Air Commodore Blythe Crawford highlights the urgency that is required for western nations to prepare for the eventuality of war

Babcock plays a critical role in international defence. In a world of significant geopolitical instability, national security has never been more important as defence requirements become increasingly complex to deliver.

Ensuring those critical services are readily available, affordable and long-lasting is a vital task. And Babcock is built for that task.

Now more than ever, what we do matters.

KCB ADC, Chief of the Defence Sta

These are worrying times. In the past few years, the world has gone from being competitive to becoming openly contested and, in the case of Russia and Iran, is now openly combative. Antagonistic powers are challenging the international system. Long-simmering tensions are coming to the boil. And the shockwaves are being felt through food and energy markets and in the global economy.

As concerning as this might be, we should be con dent that the United Kingdom is safe. We are safe because we are a nuclear power, because we belong to the world’s strongest and most powerful defensive alliance – NATO – and, above all, because of the quality of our Armed Forces and the men and women who serve.

The Royal Air Force is at the heart of this. At home, the Quick Reaction Alert Typhoons provide the rst line of our defence, protecting our airspace 24/7/365; and, beyond our shores,

the past year has con rmed the critical importance of British air and space power in deterring our adversaries, defending our interests and contributing to global stability.

In Europe, RAF fast jets are contributing to the defence of NATO airspace. Our Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance capabilities provide situational awareness across the Alliance’s Eastern ank and the crucial Black Sea region, while the air mobility force is maintaining an essential airbridge to Ukraine, supplying lethal and non-lethal aid and transporting Ukrainian personnel to the United Kingdom for military training. We have also recently completed the initial ying training for the rst wave of Ukrainian F-16 pilots, whose skills and combat air capabilities will assist in pushing back the Russian aggressors.

In the Middle East, a decade of operations against ISIS in Iraq and Syria has proven the RAF to be our most lethal force.

This April and May we have used the precision and proportionality of our capabilities to strike targets in Yemen, which were threatening international shipping in the Red Sea. At the other end of the spectrum, the RAF has been instrumental in providing humanitarian aid to Gaza via a series of precision air drops. Most signi cant of all, the RAF joined partner nations to repel waves of missiles and drones launched from Iran against Israel, thus preventing the con ict with Hamas becoming a full-scale regional war.

At a global level, British involvement in international air and space power programmes, including Typhoon and F-35, is strengthening our domestic prosperity through the signi cant defence exports generated from our aerospace sector. In parallel, these programmes are enhancing our industrial resilience and augmenting our sovereign independence. The Global Combat Air Programme with our strategic partners Italy and Japan will provide an important vehicle to develop our next generation of technologists, whose expertise is growing to embrace increased levels of autonomy, arti cial intelligence and human-machine teaming.

Our close support to allies and partners, particularly Ukraine, has emphasised the necessity of innovating and rapidly iterating the way we operate and ght. We have recently launched the Defence Drone Strategy and the RAF Autonomous Collaborative Platform Strategy to develop an

array of uncrewed systems that will strengthen our future air power capabilities, especially our combat air mass.

Our aviators also play an essential role in the development of air and space power across NATO, ensuring our capabilities, particularly in Integrated Air and Missile Defence, are t for purpose and that we have the munitions and logistical support required to sustain high-intensity operations now and in the future. We are developing our fth-generation capabilities through the F-35 Lightning Force, operating jointly with the Royal Navy as part of the United Kingdom’s Carrier Strike capability. This year, they have been training and exercising with the Joint Expeditionary Force in the High North; next year, they deploy to the Indo-Paci c.

As the Space Domain becomes ever more central to our modern lives and to our defence and security, we are also continuing to invest in this capability and in the resilience of our space-based assets, working in close partnership with our key space allies, especially the US and Australia.

This spectrum of initiatives is enhancing and re ning our air and space power, ensuring it is more integrated, more agile and lethal, and better able to deter those who wish us harm.

I am grateful to the men and women of the Royal Air Force, for all that they do to protect the nation and help it prosper. As we mark the 75th anniversary of NATO, with the Summit in Washington this July, we should be reassured by their contribution to the security of Europe and stability in the world more broadly, and I commend Air & Space Power 2024 to you.

KCB ADC FREng, Chief of the Air Sta

Ready to y and ght

Welcome to this 2024 edition of Air and Space Power, the theme of which is Integrated and Interoperable Deterrence.

When we consider the multiple and multiplying threats facing us, we must use air and space power to deter aggression and to maintain our freedom, security and prosperity, utilising our world-class air and space forces. It is always preferable to deter con ict from happening, rather than having to deal with the consequences of con ict once it has started. A key aspect of deterrence is our proven ability to defend what we value, especially within the United Kingdom, as well as across our interests internationally.

Ultimately, we must be prepared to defeat those who choose to use aggression against us, wherever they are and whenever they try to harm us. For our air forces, that means we need to be ready to y and ght.

E ective deterrence is fundamentally about a ecting our potential adversaries’ decision calculus. We need to understand what they value and what will change their minds. Our adversaries must also understand our willingness and our ability to use air and space power to protect those things which are important to us.

To do this, we need credible capability. Air and space power have unique characteristics that can be used to deny our potential adversaries the ability to achieve their strategic aims. But, to be

most e ective, air and space power needs to be integrated with the other three operational domains – land, sea and cyberspace. Multi-domain operations o er the opportunity to overwhelm and outmanoeuvre our adversaries. By doing this alongside our allies, we enhance our credibility, capability and capacity. Interoperability adds to our strength and enhances our deterrent e ect.

Air and Space Power 2024 provides a timely overview of how well we are enhancing our integration and improving our interoperability to deter our adversaries. It sets out how the UK and its allies are delivering world-leading and worldbeating air and space power. This is set against the strategic backdrop of ongoing con icts in Ukraine and across the Middle East, as well as rising tensions in the Indo-Paci c. It considers the array of initiatives, which are in ight, to ensure we develop air and space capabilities that will make sure we remain ready for the challenges of the future.

Key to our future success will be the extent to which we can identify, embrace and operationalise emerging technologies as we iterate, innovate and evolve our air and space capabilities. In particular, this includes how quickly we can exploit emerging digital technologies and how e ectively we use autonomy and arti cial intelligence to enable future air and space war ghting concepts. It also covers how we develop, along with our key allies,

next-generation capabilities, including hypersonics to ensure that our ability to conduct long-range precision strike remains potent.

Most importantly, con ict remains very much a human endeavour and our success rests with the quality, innovative spirit and operational resilience of our personnel. This necessitates ensuring that we continue to attract, select, develop and prepare our aviators to face the signi cant challenges ahead. Our ability to utilise the vast range of talents and experience, which exists across our whole force, will be key to our long-term success.

I would especially wish to thank my fellow air chiefs for their key contributions to this leading air and space power publication. They highlight that we are stronger together, with the key source of our collective strength being in the quality of our relationships and how well we work together.

I hope that you nd this array of articles to be both interesting and thought-provoking. These contributions from our aviators, senior civil servants, allies and partners, and leaders across the aerospace industry demonstrate the breadth and the depth of our expertise. The combination of these ideas and initiatives will be essential in achieving integrated and interoperable deterrence. Together, we will be ready to deter those who wish us harm, to defend and, if necessary, to defeat aggression against us and to assist our allies and partners whenever and wherever they need us.

Leveraging the United Kingdom’s world-class defence and aerospace capabilities, the RAF’s Protector RG Mk1 will provide unmatched awareness and multi-domain integration. Together, we make Protector the most advanced and versatile remotely piloted aircraft system ever built.

L3Harris values its long-standing partnership with the Royal Air Force as we proudly support its missions with reconnaissance aircraft that demonstrate proven reliability and performance. The RC-135W Rivet Joint, under the Airseeker programme, offers near real-time on-scene intelligence collection, with analysis and dissemination capabilities. As the industry-leading provider of ISR and mission-critical solutions, L3Harris will continue to deliver and sustain the highest-performing tools to address our customers’ most sensitive missions in both traditional and rapid-response environments. L3Harris and the Royal Air Force — partnering on Airseeker since 2008.

Scan to learn more. L3Harris.com

The theme of this year’s RAF Air and Space Power publication – Integrated and Interoperable Deterrence – re ects an unwelcome realisation that the West now faces a sophisticated group of like-minded potential peer adversaries with an advanced set of military capabilities. Not since the height of the Cold War has NATO, its constituent Member Countries and strategic partners had to contemplate the possibility of a potentially not-too-distant con ict against an adversary that not only matches our capabilities, but in some areas exceeds them.

In his interview, Air Marshal Alan Marshall, underlines the undeniable truth that, to counter the growing threat, the West must be able to ght together as a single integrated entity across all the operational domains – land, sea, air, space and cyber. Not only that, it needs to embrace an evolved doctrine, one that sees agility and the ability to quickly disperse forces as the only way to counter the enhanced situational awareness that emanates from multi-domain intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, including the introduction of innumerable intelligence-gathering systems paired with ever-faster missile systems and a multitude

of attack drones. Russia’s use of ballistic, cruise and hypersonic missiles against Ukraine, combined with waves of kamikaze drones, serves up a warning that the West cannot ignore.

Readers will notice a common theme across many of the articles in this year’s publication, that of Agile Combat Employment (ACE). Events in Ukraine have spotlighted the urgent need for forces to be able to disperse dynamically across their operating areas, often to remote and austere locations. Air Commodore Ady Portlock’s article on ‘Agile Basing to Fly and Fight’, reveals the underlying concept of ACE within the homeland and how it can be achieved.

Air Commodore Lee Turner highlights how the RAF is developing its ACE capabilities alongside allies and partners for operations away from the home base. In addition, this year, we are extremely fortunate to have a contribution from Group Captain Michael Sleeman, Director of the Royal Australian Air Force’s Air & Space Power Centre, and Group Captain Trav Hallen, Director of Strategic Design Royal Australian Air Force Headquarters. They look at ACE from their antipodean perspective and highlight the

The Protector ISTAR RPAS will enter service with the Royal Air Force by the end of 2024 (PHOTO:

importance of embracing Agile Combat Employment in protecting mainland Australia and projecting air power across the Indo-Paci c, where the tyranny of distance adds formidable complications.

The UK’s new Space Commander, Major General Paul Tedman, highlights the vital role that space plays in day-to-day activities for commerce, society as a whole and especially Defence. He also points out that, between them, Russia and China are developing capabilities to contest the domain. As an example, in the short period from 2019 to 2021, the combined operational satellite eets of China and Russia grew by 70%. It is for this reason and others that Major General Tedman highlights a set of responses that the West should take to ensure it can keep up with developments in space.

Space is a vital domain when it comes to another key theme of the publication – Multi Domain Operations (MDO), which rely on the ability to integrate and interoperate and act as one across all the domains and alongside sister services and allies. As a baseline towards this MDO capability, Air Vice-Marshal Jason Appleton, explains how Number 2 Group has reorganised itself to achieve more integrated and interoperable capabilities and to become an MDO-centric organisation.

As ever, the RAF Air and Space Power publication tracks the progress of existing and future capability programmes, including RPAS (remotely piloted aircraft systems), ISTAR (intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance), and GCAP (Global Combat Air Programme). This year is no exception, as we hear from Air Commodore Alex Hicks how Protector’s test and evaluation process will be carried out to ensure that the replacement for Reaper reaches its in-service date in 2024.

An update on the E-7 Wedgetail airborne early warning and control aircraft is o ered up by the Commanding O cer of Number 8 Squadron, Wing Commander Sarah McDonnell, in which she details how the US, UK and Australia will pool their e orts to develop and sustain the capability over the coming years. As well as coverage of the Typhoon and F-35 fast jets, we also include a fascinating explanation from Air Commodore Martin Lowe, FCAS (Future Combat Air System) Programme Director, of how Japan’s recent membership of the Global Combat Air Programme will enhance the capability and strengthen the industrial and technological footprint to develop the system of systems that will be borne out of it.

Emerging technology, especially dual-use technology, is becoming an ever more important element in the ability to retain a technological edge over potential adversaries. Prototype warfare is now, once again, key to developing new capabilities to support existing weapon systems rapidly. This is not as easy as just buying a COTS (commercial o -the-shelf) drone and sending it into battle. Group Captain James Bolton highlights the challenges that this complex process involves.

To complement this, the RAF’s Chief Technology O cer, Cecil Buchanan, further describes the hurdles and pitfalls associated with bringing emerging technology from prototype to operational service. Also, as an acknowledgement of the future of air warfare, Mike ‘Pako’ Benitez from Shield AI, in his article ‘Building the World’s Best AI Pilot’, reveals how arti cial intelligence is being used to advance the development of Unmanned Combat Air Vehicles.

The demands of military aviation in the 21st century leave no room for compromise – or outdated solutions. With cutting-edge technology and unrivalled build quality, the EJ200, installed in the Eurofighter Typhoon, has proven time and again to be the best engine in its class. To find out more about our market-leading design and unique maintenance concept, visit us at www.eurojet.de

The EJ200: Why would you want anything less?

of Sta ,

In today’s era of Great Power Competition, no single nation can succeed alone. The character of war is changing, and the pace of change is unlike anything we’ve seen in our lifetime. This pace is de ned by the rapid advance of disruptive technology. As technology changes, potential adversaries adapt and seek to exploit the advancements, shifting the strategic environment. Warfare today privileges a few key attributes, but one of the most vital is agility.

We must solve for agility –adapting to the threat with a new kind of speed, power and balance. Like accomplished judo athletes remain on the balls of their feet to enable the most rapid reaction, adaptation and attack, so too can this concept apply to e ective modern warfare. While agility in and of itself provides a level of increased combat e ectiveness, collective agility can be a gamechanger. Collective agility is achieved when every member of the ghting coalition is synchronised, acting and reacting in concert. Through dynamic and e ective command and control, the entire force package can have superior situational awareness and demonstrate speed of recognition, decision and action needed to seize and maintain the initiative.

A single bird in the air or a sh in the ocean uses agility to e ectively navigate through their domain, but a ock of predatory Harris Hawks or a school of barracudas are a force to be reckoned with. Their collective agility

provides the movement and power to work together with tremendous e ect. Individual squadrons throughout many of our air forces achieve this level of synchronicity. The challenge is synchronising across larger, dissimilar units and, eventually, across air forces. Interoperability and a high level of integration are the building blocks of collective agility. The power of this capability was on full display on 13-14 April when Iran and its proxies launched more than 300 airborne weapons across the Middle East. Partner forces destroyed nearly all of them before they reached their targets. This coalition action highlights the e ectiveness of coordination and information sharing to mitigate threats.

The changing character of war requires that we move and think as one, and the events of last April were a glimpse into the future... a glimpse of the increased scope and scale of actions that will be the hallmarks of future warfare.

Integration starts with us. Common values like respect for sovereignty, liberty and the rule of law form the foundation of our relationships. These relationships translate into strategic real-time intelligence sharing and culminate in integrated battlespace activities. The multinational collaboration we’ve seen in support of Ukraine over the past 28 months is an example of what’s possible. The employment of standardised technology among NATO members and across multiple sectors of our industrial base are

promising rst steps. The rapid development of unmanned aerial systems, embodying bleeding-edge lessons learned from the battle eld, illustrates what can be done at speed and scale when our e orts are aligned. We must be integrated by design, and interoperable by necessity.

As part of the U.S. Air Force’s plan to reoptimise for Great Power Competition, we are scaling training opportunities and expanding exercises to deepen interoperability. This summer, air forces from Germany, France and Spain participated in Paci c Skies 24, a series of exercises in Alaska, Hawaii, Japan, Australia and India. In the past six months alone, armed forces from a score of INDOPACOM nations trained with the United States during more than 60 unique exercises. These activities are the rst of many to come. We intend to expand the frequency and scale of our exercises, synchronising with our Allies and Partners not only within, but also across regions.

The character of war is changing, and we must change with it. Agility must extend beyond battle eld capabilities and permeate the very bres of our relationships, resulting in institutional – and, eventually –collective agility. This is our destination. We’ll know we’ve reached it when, just like the school of sh as it changes direction, our actions appear seamless, guided by our common goals and enabled by our collective agility.

The RAF’s Air and Space Commander, Air Marshal Allan Marshall, highlights to Simon Michell the importance of an integrated and interoperable Air and Space Force

Eective integration and interoperability are proven means of increasing the overall combat e ect that military forces can deliver. Bene ts include increased synergy, e ciency, agility and resilience, and it is an area where, for the most part, Western nations, allies and partners are more advanced and have advantage. The UK is no exception and, “alongside a proven ability to operate with a ‘Joint’ approach internally, has long been an enthusiastic champion of collaborating

with the defence forces of like-minded nations that share our policy aims,” a rms the RAF’s Air and Space Commander, Air Marshal Allan Marshall.

The pre-eminent alliance that underpins this drive for a cohesive multinational military capability is NATO. However, the UK is also involved in a range of other partnerships that enhance and deepen integration and interoperability, often using the baseline standards of the NATO Alliance. These include collaborations such as the Five Eyes intelligence-

Interoperability among NATO nations is highlighted by the ability to refuel each other’s aircraft in the air

(PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

An RAF Typhoon, French Air Force Rafale, USAF F-35A, RAF F-35B and a second French Air Force Rafale y together as part of Exercise Atlantic Trident in November 2023

(PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

sharing group of nations, the Anglo-French Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF), the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), which aligns the UK with Nordic and Baltic nations, the Five Powers Defence Arrangements, and numerous bilateral relationships. This level of international cooperation highlights that the UK already has a rm foundation for integration and interoperability, but the journey is far from over. With a clear imperative to maximise the deterrent e ect of forces and, by implication, their potency, the need to pursue further integration and interoperability is clear. “There is still a lot to do. In fact, it is an enduring process,” con rms Air Marshal Marshall, “but, there is no doubt that the western approach to military cooperation is the envy of the other major global powers, speci cally China and Russia, and it is an imperative that we retain our advantage.”

In terms of what the RAF is doing to enhance its Air and Space integration and interoperability, a key focus remains on air command and control (C2). Here, over recent years, the C2 of all air activity has been simpli ed and brought together at a central point within Number 11 Group and its Air Component Commander, and this construct is now well understood and established. “By doing so, not only have we been able to better integrate within the RAF, but also with our sister Services via Joint Headquarters, and wider with International partners.” As you would expect, the Space Command Space Operations Centre ful ls an equivalent role, linking into Joint Headquarters, as well as into the US-led Olympic Defender Programme and beyond.

Maximising the delity and timeliness of shared Air and Space awareness information is another important element. Here, in addition to introducing new intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities and embracing commercially available feeds, such as satellite imagery or open-source information, having the means and policy permissions to share swiftly and securely with partners is paramount. “Those who share the greatest amount of situational awareness, at the highest update rate, and have the policies and permissions to take collective action, have a signi cant advantage in con ict,” reveals Air Marshal Marshall.

Beyond C2 and Air and Space awareness, the ability to operate capabilities in an integrated manner is an evident requirement in order to maximise the overall mass and e ect that can be achieved. Here, the Air domain is well established, with the approach of Combined Air Operations having been in place for decades, allowing di erent platform types, multinational where required, to operate in a synergistic manner. This approach is routinely utilised on operations and practised during training across the globe – examples include the UK’s Cobra Warrior exercise series, Red Flag in the US, Desert Flag in the Middle East, Ramstein Flag in Europe and Pitch Black in Australia.

Alongside agreed tactics, procedures and C2, the interoperability achieved is underpinned by having the right connectivity between platforms and the wider C2 network to securely share orders, targets and situational awareness. Additionally, the ability to share airborne refuelling assets is key. “We have a good baseline for cooperation here and can rapidly deploy

and operate capabilities together across the globe for control of the air, strike, ISR or air mobility missions, but there is much more to be done to reach our full potential within NATO and other partnerships,” says Air Marshal Marshall. “We must keep exercising, pushing the boundaries of, and policies for, cooperation, and ensuring we have equipment that can operate as part of an integrated force, not in isolation.

“The proliferation of common platforms – such as Typhoon, F-35 and, potentially, E-7 – gives us some advantage in this area, but there remains much to be done, as we need to leverage all elements of multinational forces to deliver the greatest deterrent e ect and war ghting capability. An area for particular focus must be our ability to operate together within a contested electromagnetic environment, as the con ict in Ukraine has clearly demonstrated how challenging that environment is likely to be in the future.”

In addition to increased interoperability within C2, air/space awareness and air operations, many air forces are also, rightly, reviewing the resilience and survivability of their forces, not just in the air but also on the ground. This is exempli ed in the concept of Agile Combat Employment (ACE), which, while not a new concept, is swiftly gaining renewed traction in the UK, US, NATO and further a eld.

ACE, where aircraft launch, recover and are sustained from dispersed operating locations, often in coordination with allies and partners, enhances

resilience, complicates adversary planning and targeting, and broadens the options available to commanders. Here, in addition to having su cient sovereign enablers and deployable C2, the Air Marshal judges that international interoperability must be a priority. Common enablers along with permissions and training to support others’ platforms are key, to allow nations to use a wider range of operating locations for refuelling, rearming and servicing. “We are trying to make our enablers as generic as possible, so that these resources can be shared. Shared weapons stockpiles and/or permissions for carriage and use of others’ weapons o er signi cant bene ts.”

The ability to maintain, mission programme and even operate others’ assets can also add value; however, here the challenges are likely to be far greater in terms of policy and permissions, hence the priority should be at getting basic levels of interoperability assured as part of ACE, as this is where the greatest value can be added in the near term.

It is clear that Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, and uncertainty over China’s intentions in areas of the Indo Paci c, has increased the imperative to deepen integration and interoperability both within and among Air and Space Forces. Air Marshal Marshall insists, “Such is the opportunity that this cooperation o ers that we must invest in it to maximise the e ect that we can collectively deliver, to deter adversaries and, if necessary, prevail in con ict. Our Global Air & Space Chiefs Conference provides an excellent opportunity to further this ambition.”

F-35s from the RAF, Royal Australian Air Force, US Navy and US Marine Corps line up while on Exercise Northern Edge 2023 in the Gulf of Alaska (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

Nick Cha ey Chief Executive UK, Northrop Grumman Corporation

What does the changing global threat environment mean for the air domain?

I think few would disagree that the emerging threat from near peer adversaries is both substantial and rapidly evolving. Our adversaries have increasingly advanced air forces and weapons, capable of projecting power over extremely long ranges and at high speed.

The advent of hypersonic weapons, low-cost high-mass attacks, and nextgeneration stealth all demand far faster operational re exes than our forces have previously faced. And these threats exist on an ever-widening spectrum, blurring the lines between traditional warfare domains.

The air domain, and supremacy of it, remains essential in dictating the dynamic of con icts. But achieving and maintaining that air supremacy is now harder than ever, and that di culty will only continue to increase. Against the near-peer threats of tomorrow, we should accept that air superiority will need to be locally targeted, agile and incisive, and operationally exible.

What capabilities do you see as a priority?

I think we need to look at a wide range of interconnected developments. We must, of course, continue to work hard to

develop and deliver the exquisite nextgeneration platforms. Sixth-generation aircraft, such as the B-21 Raider, and the development of advanced unmanned platforms can provide forces with powerful new capabilities and a decisive advantage for future con icts. This is an area where Northrop Grumman has a long and proud history.

As we have seen in Ukraine, modern air defence is extremely e ective in denying the reliable operation of all but the most advanced air platforms. Persisting in these denied environments requires capabilities that can continue to defeat radar, maintain stealth and utilise LPD/LPI communications. Future developments that leverage very high speed and altitude advantages could prove highly valuable. If we look left of launch, investing in advanced SEAD/DEAD capabilities is also essential. Solutions such AARGM-ER are designed to disable even the most advanced enemy air defences before they have a chance to attack our forces.

Linking capabilities across domains is also an increasingly critical force multiplier. For example, space-based assets are increasingly key di erentiators. The high delity, persistence and low latency of modern space-based ISR provides an ideal complement to long-range, long-endurance air C4ISR platforms like Triton. But space is also ever-more contested. Assuring our assets and monitoring adversary activity is already of paramount importance. Capabilities like DARC are vital to this mission.

Orchestrating this all-domain web of deployed forces and capabilities requires systems that are built from the ground up to be open and interoperable, linking every sensor and e ector into a common picture across services and allied forces. And it is that common picture that will allow rapid and e ective coordination of response to any threat,

while also intelligently managing munitions stockpiles. This is the philosophy behind our IBCS system, which continues to evolve both operationally and technically.

How can we accelerate from concept to execution?

I think a key takeaway is that much of the technology we need is available today. The real challenge is developing solutions for our customers that meet their speci c needs, while enabling allies to work together seamlessly. Key to this e ort is partnership. Modern capabilities rely on industry working together, and at Northrop Grumman we are committed to building these types of partnerships around the world – from national champions to innovative start-ups. Policy initiatives such as AUKUS hold real potential to further unlock a new age of collaboration among allied forces and the industrial base that supports them. Agility in procurement, deployment and improvement of capabilities is also an area I see growing in importance, ensuring our servicemen and women have the right tools when they need them. Employing a digital- rst mindset can help here. Digital engineering allows the rapid prototyping and deployment of new solutions and upgrades, with engineers able to test performance and integration before a single tool is lifted. The employment of advanced modelling and simulation technologies can also allow industry and customers to understand how a set of capabilities can work together to deliver e ect in a future real-world deployment. Finally, we must continue our progress towards truly open, extensible systems built for integration from day one. A resilient and adaptable web of systems – from seabed to space and among allied forces – will unlock the agility, redundancy and information advantage we require to defend against the threats of today and tomorrow.

Northrop Grumman’s Business Development Director, Paul Tremelling, reveals the pathway to achieving an integrated and interoperable air-defence capability

Sometimes not much changes, save for the nomenclature. Commencing on 13 June 1944, the United Kingdom came under concerted cruise missile attack. The British called the weapons ‘doodlebugs’. Approximately 10,000 V1 weapons were launched in a campaign that saw weapon use peak at hundreds per day. The weapon could be surface- and air-launched. Advances by allied land forces in Europe denied the enemy launch sites, and, as logistical targets became available to the enemy elsewhere, weapons were also launched at Antwerp.

Weapon-to-target matching was limited by accuracy, with the wunderwa e employed against cities. They were thought by enemy planners to

deliver a terrorising e ect. A layered defence system, previously used to defend against the crewed e orts of the Luftwa e earlier in the war, achieved some success. Defensive Counter Air ghters, cued by ground-based radar and dependent on voice communications, were able to destroy and disrupt weapons in ight. Anti-Aircraft Artillery, geographically de-con icted from friendly ghters, were also e ective, as were passive defences.

The weapon with no obvious counter was the infamous V2. A trajectory with an apogee of over 80km encompassed both air and space domains, its supersonic arrival and larger warhead setting it apart from its V-weapon stable mate. Allied forces thus employed a ‘left of launch’ methodology,

Interoperability is becoming increasingly important to allied forces’ ability to work together seamlessly

By using the IBCS system, Polish armed forces are able to connect sensors and air-defence weapon systems that were not initially designed to work together (PHOTO: U.S. ARMY)

with combined bomber raids mounted against targets such as Peenemunde and Wizernes. German forces responded by adopting an agile employment concept of moveable V2 launchers.

Then and now: the all-domain threat

While the parallels between then and now are stark, so are some key di erences. Chief among those di erences is that we must now consider a vast continuum of airborne threats across system size, e ective range, operating height and speed.

Modern-day Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) must be able to defend against the short-range, hand-launched drone and all the way up the capability continuum to the ballistic missile – and everything in between.

Here we see a blurring of domains: there has been discourse concerning the Air Littoral in an attempt to understand threats and responsibility in the very low altitudes. It has been observed that small, disposable drones could be viewed as land-domain weaponry, allowing employment of traditional munitions such as grenades with greater reach and accuracy, but with no fundamental di erence in operator or target set. Counter-UAS systems are sometimes thought to be distinct from Ground Based Air Defence, which in turn is

in some way dislocated from wider control-of-theair thinking. This all-domain mindset must also extend upwards to the space domain, increasingly capable and vital, but also increasingly contested.

The target set is now also as continuous as the threat. Enemy forces might well target critical national infrastructure, government, the defence industrial base and lines of supply. They might target purely military targets, such as bases and barracks, air and sea points of disembarkation and elded forces.

As ever, seeking to defend everything is impractical, and recent con icts have shown that threat nations do not necessarily think or act as we would. From an IAMD sense, this means that we should not expect threat actors to follow western doctrine. It also means that we should have a very hard think about what indicators and warnings would be available and what sensors, bearers and deciders would be available after the opening salvoes of a peer-on-peer con ict.

If we were to look at the threat problem in a slightly simplistic way, it could be broken into left of launch, in ight and right of impact. Industry can assist with all three to varying degrees, as the tasks might be characterised as: Understand and Deter; Sense-Decide-E ect; and Survive to Fight.

A truly signi cant challenge is scale. Even if pooled and coordinated, it is unlikely that defence spend across NATO, given the current status of forces and systems, will result in the ability to defend every metre of frontline and every kilometre of depth against a concerted strike. Therefore we have to prioritise and integrate as an alliance. If there is a single lesson to come out of recent con icts, it is that capabilities need to be interoperable with those of our allies.

This interoperability would have an enormous deterrent e ect. Fighting against a nodeless, redundant system is hard and the enemy knows it. Their worst-case scenario would be facing a true system of systems. It would: possess no obvious critical nodes to target; detect and identify threats immediately; self-heal on the loss of any sensor or e ector; and orchestrate assets and preserve magazine depth to defeat massed threats e ciently. It would manage the physical, information and electromagnetic landscapes to best e ect. In essence, it would ght back.

To achieve this means shifting towards a truly distributed command and control (C2) network, with sensors and e ectors decoupled from one another and, instead, ‘on the net’. Further integration of space-based capabilities is also essential, leveraged to

provide pre- and post-launch tracking of threats, force cueing, and a hyper-resilient layer of communication.

Naturally, the enemy will seek to destroy and disrupt interoperable systems. They will target the systems and interoperability itself, notably through the electromagnetic spectrum. The network itself will need to be resilient against cyber and electromagnetic attack. Technologies exist that can help and must be prioritised. Low probability of intercept/low probability of detection (LPI/LPD) techniques exist to deny the enemy easy access to our bearers. It is possible to use arti cial intelligence/ machine learning (AI/ML) to detect inhibitors, and nd ways around them – much as Cold War warriors would have done manually to avoid comms jamming.

Similarly, as the space domain becomes an ever more important part of this new orchestra of capability, it is also more contested than ever before. Threat nations’ space assets are growing in scale and sophistication alongside our own. The defence of our assets in space, and the links between space and other domains, must be considered in concert with assets in all other domains.

From aspiration to execution: reality requires exibility

In terms of aspiration, the defence enterprise is in lock-step here. We have heard various defence seniors talk about interoperability and interchangeability. We have heard the battle cries ‘On the net or o the battle eld’ and even ‘Stop buying new stu and join up what I’ve already got’. At the same time, industry has developed the technologies that would deliver exactly this and both the deterrent and war ghting e ect that we seek. Indeed, at Northrop Grumman, our Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS) solution continues to prove that true integration is possible today –whether that be with new space-layer sensors, across allied nations, or with highly capable assets not traditionally associated with IAMD, such as the F-35. There must also be an acknowledgement of industrial realism. Given the necessity for governments to support local and national industry, it is unlikely that the Alliance will adopt a universal, ubiquitous NATO air defence radar, cueing an equally universal surface-to-air missile, using a universal C2 system. Therefore, we need to ensure that these indigenous capabilities that give their countries the freedom of action, modi cation and upgrade that they rightly demand are still able to integrate into a common operating framework. Indeed, the Ground-based Air Defence/Integrated Air and Missile Defence (GBAD/IAMD) contexts and requirements of the US Army and Polish Air Force di er in a great many ways – both are successfully powered by IBCS.

Industry will re ect the desires of the customer, and the customer should be demanding not only open but common systems to allow rapid development, upgrade and integration with future capabilities, both domestic and allied. Military procurements thus need to actively guard against closed, bespoke or proprietary technologies. The obvious bene ts of open systems should not be unpicked by having to choose between them.

The technology is ready now

It is, obviously, possible to share target tracks across tactical data links, such as Link-16. In purely technical terms, a British soldier or airman could, today, engage an enemy target received as a link track from an allied combatant and prosecute an attack. That ‘Engage on Remote’ capability has been possible for well over a decade.

Permissions-based systems following a publish/ subscribe model are a very viable solution. So long as individual nations are prepared to share the required data, this will work across an alliance. The joy of a digital architecture is that nations can still protect what they do not want to share: multi-level and cross-domain guards and gates can achieve both sharing and withholding. That is all to say: the obstacles to successful allied integration are not technical or industrial.

While the developing continuum of IAMD threats is truly vast, the worst thing to do seems to be to do nothing. Indeed every step forward made by the defence enterprise – uniformed, not in uniform or in industry – seems to contribute directly to IAMD. In 1944, the United Kingdom was part of a well-founded and determined alliance. That remains the case today. As nations and NATO evolve solutions, interoperability has to be the hill we die on.

Major General Paul Tedman CBE, Commander of UK Space Command, highlights the urgent need to enhance the UK’s ability to ght in and from space

The UK and Europe rely on a wide array of satellites to enable essential services, such as power networks

(IMAGE: SHUTTERSTOCK/ NICOELNINO)

“If you haven’t realised it yet, it’s all about space; space has emerged as our most essential war ghting domain.” Admiral Christopher Grady, US Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Sta – US/NATO Allied War ghter Talks, October 2023

Space is one the UK’s critical national infrastructure sectors. Economists report that circa 30% of the UK economy is enabled by space; Britons rely on about 40 satellites a day to navigate, communicate and transmit data. For example, Precision Navigation and Timing (PNT) services transmit timing signals for banking, farming and electrical power grids, as well as enabling communications across wireless internet and navigation services for rail, road and air.

A 2018 study, undertaken on behalf of the UK Government, highlighted that disruption to PNT services could cost the UK economy £1 billion a day.

Furthermore, as Admiral Grady reminds us, e ects delivered or enabled by space are also central to how we ght. Technological advances in sensing ( nd), decision-making (decide) and precision long-range attack (strike) enable dramatically faster, long-range, all-domain, precision engagements, conferring a strategic advantage over a peer adversary. We now live in an era of advanced engagements where, if it moves or emits, and is not under cover, it will likely be seen and targeted by space-based or -enabled capabilities. Even an unclassi ed review of evolving lessons from Ukraine demonstrates that, when maritime, land and air domain operations have largely ground to a stalemate, space-enabled advanced engagements have dominated.

Our adversaries also understand the importance of space and are actively developing capabilities to contest the domain. According to a US Defence Intelligence Agency report from 2022, between 2019 and 2021 the combined operational satellite eets of China and Russia grew by 70%.

As part of its emerging multi-domain precision warfare concept, China is deploying capabilities to enable a space-based kill web. On 27 July 2021, China tested the rst fractional orbital launch of an intercontinental ballistic missile with a hypersonic glide vehicle ying 40,000km in 100 minutes, demonstrating the greatest distance own and longest ight time of any Chinese weapons system to date. In October 2021, we saw a Shijian 21 satellite grapple a derelict PNT satellite, move it to the Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO) graveyard belt and return to GEO at extraordinary speeds – the counter space applicability is clear.

Three months before the invasion of Ukraine, Russia successfully tested the NUDOL Direct Assent – Anti-Satellite (ASAT) system against one its defunct PNT satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). The resultant 1,500 pieces of debris created a collision risk for all satellites in LEO.

We must conclude that China and Russia have weaponised space and demonstrated the will to use ASAT weapons. This evolving threat, coupled with space congestion (circa 9,000 orbiting satellites in 2024 rising to between 60,000-100,000 by 2030), and the absence of comprehensive space governance, treaties and arms-control measures, underscores the urgency for action to assure national security in the face of rapidly evolving threats.

If the ends are becoming clear, our constrained resources dictate that, regardless of necessity, there is no automatic recourse to greater means, and a trade-o that envisages fewer aircraft, ships and tanks but more satellites is likely unpalatable. A more imaginative blend of ways is required to bridge the gulf between aspirational sovereign capability and the resources available. Illustratively, the most salient elements of this approach could be:

First, ensuring that the public and policymakers are aware of our dependence on space and the threat to our way of life and way of war. Many in the UK understand that space is no longer an enabling operational capability, but a national strategic capability in its own right. Lord Hague wrote in The Times on 29 January 2023 that, “It is well understood that we need big investment in new areas of technology such as drones, sensors and space”. This understanding now needs to translate into policy and the means to deliver and assure space missions to a level commensurate

with the impact of their loss or degradation to our national security. The UK’s 2022 Integrated Review allocated £1.4 billion over 10 years to space capability, which, when added to existing funding, equates to less than 1% of defence’s annual spend.

Second, and closer to home in UK Defence, we must normalise the space domain and ensure its seamless integration into joint operations. Normalising space involves dispelling the mystique surrounding space operations and breaking down the barriers that impede comprehensive understanding and utilisation of space capabilities. This entails fostering a culture of space literacy among policymakers, military leaders and the public, wherein the signi cance of space to national security, economic prosperity and military operations is unequivocally recognised.

Third, and building on this normalisation, we must recognise that space is an inherently ‘Joint’ domain and that the traditional physical domains are increasingly dependent on it. This drives an imperative for an unprecedented level of tri-service cooperation and the need to provide a space frame of reference for our military leaders who have spent most of their careers considering sea, land and air domains.

The Chief of Sta of the US Army (CSA) has grasped the importance of space. In January 2024, he co-signed the ‘Army Space Vision Supporting Multidomain Operations’, in which he states, “Successful operations in and through the space domain will be crucial to our success... simply put, we will be operating under constant surveillance and must invest in the knowledge and forces to counter threat space systems and enable our own systems... developing new space capabilities, organisations and trained professional soldiers to deliver e ects for Army manoeuvre forces is critical to multi-domain operations”. The CSA rightly highlights that failure to mitigate space threats upstream will create deterrence challenges across all domains and increase risk to the Joint Force.

Skynet 6 will enable UK Strategic Command and UK Space Command to deliver information advantage and superiority in both standing tasks and contingent operations (IMAGE: AIRBUS)

UK Space Command will need to work with its allies and partners to maximise joint capabilities

(PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

Denying, countering or limiting the e ects of adversary space systems will be critical to protecting terrestrial forces and winning advanced engagements. Accordingly, we must identify and exploit elded joint capability that could deliver non-traditional space e ects, and better understand where we need to be more competitive to deter and, if necessary, ght and win the battle above. Space is Joint, and Joint includes Space.

Fourth, international cooperation also plays a pivotal role in a ording us access to the space

and interoperability under the banner of its 2022 ‘overarching space policy’. This work is nascent, largely focused on information-sharing, coordination, doctrine and standardisation, and, therefore, represents an opportunity for early investment and in uence.

Fifth, we should learn from US experiences and take more risk to reform procurement processes and cooperate with commercial providers to develop a hybrid military and commercial architecture. Ministry of Defence procurement processes designed for 20th-century large capital programmes are not t for a digital 21st century, where space technology evolution can be measured in just months.

Although some space mission areas have assurance requirements that necessitate government ownership, many could be delivered by accessing dual-use commercial services. There will need to be further analysis to characterise the commercial space sector and the possible risks and limitations of employing the services on o er. However, there are numerous opportunities to incorporate commercial business practices and to generate demand signals within industry that will bring bene t. Procurement reform would allow UK space capability to accelerate, as well as build industrial resilience and capacity through growth of the UK sector, thus supporting the UK’s prosperity agenda.

“Denying, countering or limiting the e ects of adversary space systems will be critical to protecting terrestrial forces and winning advanced engagements”

capabilities of allies and partners. Given the transnational nature of space operations and the increasingly congested and contested space environment, collaboration with like-minded nations is imperative for enhancing deterrence, fortifying space resilience and countering adversarial actions.

AUKUS, with its stated aim of improving joint capabilities, technology transfer and interoperability, represents an existing framework to deepen and accelerate space cooperation, but, to date, explicit space cooperation has been omitted. Including space within AUKUS would bring much-needed emphasis to space collaboration and exploit a deep well of trust to enable classi ed information-sharing and reduce intellectual property and trade barriers.

Equally, the UK should take a leading role in NATO’s space development. NATO declared space an operational domain in 2019 and, subsequently, agreed to develop workstrands related to capability

In conclusion, barely 40 years after the rst powered ight, Field Marshal Montgomery was su ciently convinced of his army’s dependence on the air to state publicly, “If we lose the war in the air, we lose the war and we lose it quickly”. We are now at a similar in ection point in space that demands equivalent vision and contains opportunity and threat in equal measure.

Investment in sovereign space capability and exploring innovative ways to deliver capability are urgently necessary. E ectively framing our dependence on space, normalising the domain, exploiting extant joint capabilities, formalising mutual defence agreements and reforming procurement to develop a hybrid military/commercial architecture are all essential steps towards safeguarding the UK’s national security interests in space. We must act now if we are to deter and, if necessary, ght and win the battle above – it is no longer a choice.

Endurance: integrated deterrence

Over the past two decades, space capabilities have come to the forefront of US military operations, underpinning the Joint and Combined Force’s ability to perform all-domain command and control, long-range precision res, global movement and manoeuvre, persistent targeting, and missile defence. Our adversaries have recognised this synergy and are elding systems to challenge our advantages in the domain, while increasing their ability to utilise space for their own gain.

At the same time, we have seen the use of space increase at an astronomical rate. Space has become vital for not only global security, but for the worldwide economy and, unequivocally, our very way of life.

Collectively, these fundamental changes in the security environment have led to what I believe is a new era in space. This new era requires a new evaluation of how the U.S. Space Force is oriented to mitigate risks, respond to threats and deter our adversaries – one centred around a theory of success we call Competitive Endurance. It is a working theory of success, not victory, because it seeks to ensure our adversaries are never desperate enough or emboldened enough to pursue combat operations in space. This means space forces must have the ability to endure by sustaining a perpetual state of competition as the preferable condition to crisis or con ict.

At its core, Competitive Endurance is a theory of integrated deterrence –leveraging a combination of defensive measures, resilience-building e orts and credible space control capabilities to dissuade potential adversaries and maintain a favourable security environment. The goal is to ensure our Joint and Combined Forces can achieve space superiority when necessary, while also protecting the safety, stability, security and long-term sustainability of the space domain.

“Space has become vital for not only global security, but for the worldwide economy and... our very way of life”

Competitive Endurance has three core tenets:

– Avoid operational surprise: We must detect and pre-empt any changes in the operational environment that could compromise a safe, secure and stable space domain;

– Deny rst-mover advantage: We must make a rst strike in space impractical and self-

defeating, and thus discourage an adversary from taking such action in the rst place;

– Responsible counterspace campaigning: We must be able to conduct military activities in the space domain that enable us to protect our nation, the Joint Force and the Combined Force from space-enabled attack without generating hazardous, persistent debris.

This theory’s viability rests on our ability to build a coalition to uphold and strengthen a rules-based international order for space. Integral to the success of Competitive Endurance is a robust framework for international cooperation and coordination. Given the inherently global nature of space activities and the interconnectedness of space systems, collaboration among space-faring nations is indispensable for enhancing space situational awareness, promoting responsible behaviour and establishing norms of behaviour in space. Competitive Endurance represents a forward-looking approach to safeguarding interests and maintaining stability in the space domain. By integrating defensive measures, resilience-building e orts, credible space control capabilities and international cooperation, likeminded nations can e ectively deter aggression, mitigate risks and uphold the security and sustainability of space activities for future generations.

Air Marshal (Retd) Greg Bagwell, President of the Air & Space Power Association, considers the basic elements of deterrence in the context of a changing world

It is with more than a hint of irony that the theme of this year’s Global Air & Space Chiefs’ Conference is Deterrence, when all we see around us is how deterrence has failed or is failing. But that, of course, is the reason why this is such a vital theme at such a critical time. When seeking to deter an aggressor there are a few basic elements that one needs to consider:

Firstly, you need to have a very good understanding of what the mind, motivation, will and objectives of your opponent are – what we have learned recently to our and others’ cost is that our values and sense of fair play are not shared equally elsewhere. We have some clear-eyed thinking and some toughening up to do. Secondly, you need to identify and agree your own objectives and desired outcomes. Alliances such as NATO can be unbeatable when they are united, and it is especially pleasing to see Finland and Sweden join us here as NATO’s newest members; they have always been close friends and they will strengthen the Alliance immensely.

But while our diversity is our strength, it can also be our weakness. Consensus and clear signalling is vital, and we all have a duty to ensure that our political leadership understands their role is more than just allocating a certain percentage of GDP to defence, and so much more than their own personal or party ambition. National defence, of which deterrence is a vital part, is always a fundamental responsibility of governments, and not just something to worry about come election time or when the wolf comes knocking.

Present a credible counter

Lastly, you must have the tools to back up your words (more of that later); you need to present a credible counter to your opponent’s aims and an unshakeable willingness to meet your own. It is hard to know which of the three elements we have got the most wrong with regard to Ukraine; the honest truth is that we have failed at each one to varying degrees over a number of years and we now nd ourselves at a precipice.

And when you nd yourself at that precipice it is at that time, and only then, when you know that your deterrence has failed. For so long, we convinced ourselves that a major

war in Europe was unthinkable. And not only have we miscalculated the strength or relevance of our deterrence, but also we have forgotten how to react when it fails.

Ever since Russia illegally invaded Ukraine, we have heard only about needing to de-escalate the con ict or, at the very least, avoid escalation. The problem is that we have sought to achieve that through our own restraint, rather than impose restraint on the opponent, other than some economic sanctions.

On the horns of a dilemma in Ukraine, we have sought solace in supplying arms and training at arm’s length, and even then we have limited supplies, delayed delivery and, after all that, applied restrictions on its use. I am fairly certain that was not the strongest signal of deterrence to an aggressor, who had no such limits. Even when we had signi cant evidence of failure and weakness of the aggressor, we failed to be ruthless enough to capitalise, and opportunities have been missed to cap or curtail the con ict.

We may be entirely uncomfortable and unfamiliar with a war of this nature, scale and brutality (at least this close to home), but we need to learn quickly and we need to learn well, so that we

“You must have the tools to back up your words; you need to present a credible counter to your opponent’s aims and an unshakeable willingness to meet your own”

With the expansion into space and cyberspace, the world has become more

can both restore the status quo ante and ensure that we don’t make the same mistakes again. Most importantly, we need to re-learn that deterrence is not binary – you don’t just set a red line and hope it’s not crossed. You may need to escalate to de-escalate, and we need to come to terms with the fact that this needs to address the spectre of nonconventional deterrence and the threat of their use, especially when malign actors have no compunction in doing so. Which brings me to my nal point – that of the need to have the tools to back up your words. We have all known that early identi cation of an emerging threat is critical if you wish to ramp-up production and capacity to meet a major threat – in the UK we used to use a 10-year rule. As interstate con ict has faded from memory and an increasing drive for

e ciency for many has reduced our mass, our stockpiles and contingency capacity and infrastructure, meaning that we nd ourselves more poorly prepared for the sort of threat we now face than we would wish.

So we have some deep thinking and questioning to do; those of us old enough will be in very familiar territory, but even in our day there were some rules of the game that meant everyone knew where they

“We need to re-learn that deterrence is not binary – you don’t just set a red line and hope it’s not crossed”

The good news is that NATO remains a strong and credible alliance, but it is under attack even before the guns start ring. We need to be hard-nosed and honest about where we have allowed our capability to atrophy, and equally honest about what can be done in the near term.

stood – those rules have gone and whether it is space, cyberspace, social or other media, the world has become a more complex and less predictable place. So yes, deterrence is more than just a big stick, but without one and the willingness to employ it, it is no deterrent at all.

Air Vice-Marshal Mark Flewin, Air O cer Commanding Number 1 Group, highlights the progress that has been made to integrate the Forces under his command to make them more interoperable and enhance their ability to deter and defend

The Air Mobility Force has been fully integrated into No 1 Group. Its A400M Atlas aircraft are seen here delivering humanitarian aid to Türkiye after the devastating earthquake in 2023 (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

“Peace is our aim and strength the only way of getting it.”

FSir Winston Churchill

or Number 1 Group (No 1 Gp), the past year has been a phenomenal period, in which the Group has concluded a signi cant transformation to bring true interoperability across the RAF’s front-line forces, all while consistently delivering decisive Air Power on operations and exercises across the globe. With the Air Mobility Force now fully embedded within the Group, all front-line force elements are now under a single coherent Command, seamlessly docking with No 2 Gp as the Global Enabler and No 11 Gp as the Global Air Component to meet the demands of today, while being prepared for the security challenges of tomorrow. With the Air Mobility, ISTAR and Combat Air Forces working alongside each other, ably

supported by the Air and Space Warfare Centre (ASWC), this new and unifying structure continues to ensure that the Group is geared and focused to support the RAF’s operational output. The result is a collegiate working environment that enables best use of collective resource and the sharing of best practice, resulting in a structural foundation that has optimised force generation, collective training, readiness and resilience. One of the most obvious bene ts of these changes is a Group that brings the Air Wings together by design, driving a shared understanding of issues and risks, thereby enhancing the RAF’s ability to collectively deter and defend. Central to this success, the ASWC has remained at the forefront of our war ghting thinking, embracing the lessons from current con icts, while maximising the exploitation of the Air and Space domains. The results speak for themselves: the ISTAR Force has delivered battle-winning intelligence

product and operational e ect, often side-by-side with the Combat Air Force on operations; and the Air Mobility Force has continued to provide UK Defence with the ability to rapidly deploy, sustain and recover, remaining fundamental to the timely delivery of Defence manoeuvre. The successful integration of these force elements has been further underlined by success on recent operations, including the proportionate intervention by the UK and US after Iranian-backed Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping, where the Combat Air Force, supported by the Air Mobility Force, successfully delivered a deterrent e ect in Yemen. Alongside the ISTAR Force providing essential situational awareness in the region, and the ASWC championing rapid capability development through the Prototype Warfare Team, this new structure has helped enhance our approach to operations over the past 12 months working seamlessly alongside No 11 Gp.

The Group has also continued to adapt to embrace new capabilities to enhance our ability to defend and deter, where examples in this past year are manifold, including: the rst ight of Protector in the UK; continued progress towards initial operating capability for the UK’s second F-35B Lightning Squadron – 809 Naval Air Squadron (NAS); rapid progression towards full operating capability for the P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft; growth across the Rivet Joint enterprise and its world-leading capabilities; continued and rapid expansion of A400M capabilities, including parachuting; while also preparing for the introduction to service of the E-7 Wedgetail and its next-generation Airborne Early Warning and Control capability.

As we consider the modern Air and Space Power arena, the operational environment is characterised by rapidly evolving threats and complex security challenges, demanding agile and decisive Air Power, supported by an operational mindset that is focused on ying and ghting. In this, Agile Combat Employment (ACE) remains at the heart of the Group’s ability to deter and defend, where No 1 Gp force elements are focused on being ready to ght from home or overseas.

Con ict, instability and insecurity across the globe, alongside unfortunate natural disasters, have seen aircraft across all force elements widely employed in the delivery of humanitarian aid and non-combatant evacuations. From earthquakes in Türkiye and Morocco, and ooding in Libya, to non-combatant evacuations from Sudan and Israel, the rapid and agile approach of No 1 Gp force elements has been a critical linchpin to support those in need. Furthermore, existing in-service capabilities continue to be enhanced, including the A400M’s record 22-hour ight to Guam as part of Exercise Mobility Guardian, and Typhoon’s successful operations from a public highway in Finland, highlighting the signi cant strides across the Group in support of the development of ACE.

Set against a context of competing demands across Defence and a backdrop of global instability, the integration of all front-line force elements has not only enhanced interoperability, but has also bolstered the RAF’s ability to deter and defend against emerging threats. By building upon the progress made thus far and embracing a culture of continuous improvement, the RAF’s force elements remain focused on delivering today, while preparing to deter and, if necessary, confront the challenges of tomorrow.

No 1 Group is making continued progress towards achieving initial operating capability of its second frontline squadron – 809 Naval Air Squadron (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

This year’s Chief of the Air Sta ’s Global Air and Space Chiefs’ Conference takes place in a time which calls on all of us to take a clear and decisive stand. Our decisions are going to determine our future for decades.

The strategic situation, rst and foremost, requires responsive armed forces. It is important to demonstrate and prove that we guarantee security for every inch of any NATO Member State.

Our bilateral cooperation is a leading example of how a trusting and integrated partnership strengthens the air power of the Transatlantic Alliance.

Together with the RAF, we have already implemented Combined Air Policing at NATO’s eastern ank. We have built up a combined contingent, developed synergies, conserved resources and signi cantly increased our interoperability and combined strike power.