Holocaust Remembered Holocaust Remembered Vol. 12

Holocaust Remembered Holocaust Remembered Vol. 12

(As defined by the 1979 President Jimmy Carter’s Commission on the Holocaust)

“The Holocaust was the systematic bureaucratic annihilation of six million Jews by the Nazis and their collaborators as a central act of state, during the second World War. It was a crime unique in the annals of human history, different not only in the quantity of violence—the sheer number killed—but in its manner and purpose as a mass criminal enterprise organized by the state against defenseless civilian populations. The decision to kill every Jew everywhere in Europe: the definition of Jew as target for death transcended all boundaries…

The concept of annihilation of an entire people, as distinguished from their subjugation, was unprecedented; never before in human history had genocide been an all-pervasive government policy unaffected by territorial or economic advantage and unchecked by moral or religious constraints….

The Holocaust was not simply a throwback to medieval torture or archaic barbarism, but a thoroughly modern expression of bureaucratic organization, industrial management, scientific achievement, and technological sophistication. The entire apparatus of the German bureaucracy was marshaled in the service of the extermination process.

The Holocaust stands as a tragedy for Europe, for Western Civilization, and for all the world. We must remember the facts of the Holocaust and work to understand these facts.”

The Holocaust was an event contemporaneous in large part with World War II–but separate from it. In fact, the Final Solution often took precedence over the war effort–as trains, personnel and materials needed at the front were not allowed to be diverted from death camp assignments. On a very basic level, the Holocaust must be confronted in terms of a specific evil of antisemitism–a virulent hatred of the Jewish people and the Jewish faith. An immediate response to the Holocaust must be a commitment to combat prejudice whenever it might exist. The following articles will demonstrate how the Holocaust educational community is trying to uphold the commitment as outlined above.

BY LILLY FILLER, MD

Just when I thought that the events of October 7, 2023 were as bad as it could get for Israel, the Jewish people, and the world—more events in the world and at home occurred. The division within the United States worsened, the acrimony in discussions heightened and the political landscape seems to be tumbling out of control. The US is seemingly divided regardless of topics discussed, whether it is domestic or foreign, conservative or liberal, and what is right and wrong. Having just had the 2024 Presidential elections, half the nation is thrilled, the other half is “sitting shiva”. We thought we knew what was up, but found out it was down. And throughout all of this, antisemitism continues to rise to unprecedented levels.

As I prepare to publish this 12th Holocaust Remembered magazine, the first of this kind, I am having difficulty coming

to grips with the enormity of problems ahead. The one that interests me the most is the question that I asked “How do we teach the Holocaust in this complicated world?” I reached out to many colleagues to see what the magic bullet might be, but I don’t see an easy solution to this complex problem. Not only is the World divided, the United States divided, but the division is also seen in the Jewish communities around the states. We are struggling to understand the anger and hatred seen on college campuses, we find that we cannot converse civilly with one another about local, state and national solutions to the rise of antisemitism.

As Chair of the SC Council on the Holocaust, I work with a devoted group of appointed individuals from across the state who implement the mission expected of us from our state legislators. We are an apolitical entity, appointed by our

2 Who is Changing—Me or the Rest of the World? BY

LILLY FILLER, MD

4 “The Entire field of Holocaust Education, Remembrance, and Research is part of Yehuda’s legacy.” BY ANDREW SILOW-CARROLL

5 Yehuda Bauer (1926-2024): An Appreciation BY MICHAEL BERENBAUM, PHD

6 To Change a Mind, Start with the Heart BY LAUREN B. GRANITE, PHD

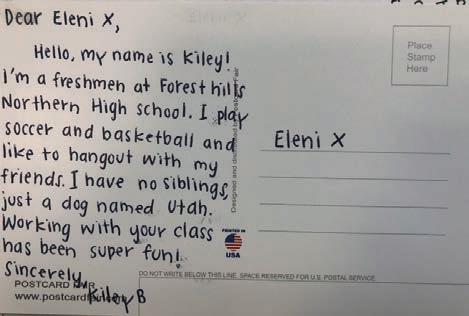

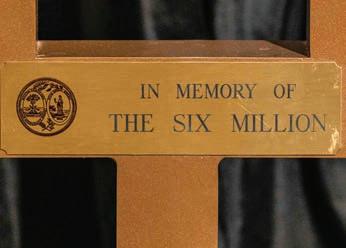

elected officials. The 12 person Council is tasked with providing Commemorative events statewide and to continue with educating teachers to be comfortable and knowledgeable about how to instruct our students. I do know that our Council members are committed to moving forward, digging deep in our souls and continuing with professional development for the teachers, programs for the students and Commemorative events for the entire community. We must not lose sight of the importance of Memory, memorializing the six million Jewish souls that were murdered by the Nazis, along with the five- six million others who perished. Hitler’s attempt to eliminate all Jews in the world was not successful, but we need to be vigilant to prevent this from ever happening again.

We lost a wonderful Scholar in October, 2024, Yehuda Bauer. Please note the

8 My Introduction to the Holocaust BY WILLIAM COX, EDD

10 Paul Pritcher, Holocaust Liberator BY EILEEN CHEPENIK

12 My Father’s Suitcase: The story of survival BY DEBORAH

TAUSSIG-BOEHNER

14 Writing the Aron Family Story BY PAT DIGEORGE, GRANDDAUGHTER

16 The Responsibility to Tell the Truth of What she Saw BY STACY STEELE

18 How and Why Should We Teach the Holocaust in 2025? BY NATANYA MILLER

Thank you to the SC Council on the Holocaust for full financial support in this project. Many of the Council members were contributors now and in the past.

I thank all the contributors to this edition for their willingness to provide ideas and options to improve the teaching of Holocaust Education. To our Survivors, Liberators and Eyewitnesses, to the individuals and families, we have the deepest respect and gratitude. You have spoken or written your story about a very difficult time in your life and for that we are deeply thankful. Only by hearing your life testimonies, can we continue to tell these stories and battle those that wish to “rewrite history”. We must Never Forget.

obituary from and the tribute from present day scholar Michael Berenbaum, that just scratches the surface of his impact to the Holocaust world. Additionally, at the end of this magazine, enjoy the article and photos of a magnificent event that was a Civic event, the 80th Commemoration of the Liberation of Auschwitz. It was powerful and beautiful! My mom Jadzia Stern (obm) always thought that if rain occurred around an important event, it represented the gentle tears of the Almighty encouraging us to continue to do this work. This is probably the last major Commemoration that will have

eye-witnesses testimonies and Holocaust Survivors available to speak.

This photo shown above is from 1987 when we had 10 survivors here in Columba and they commemorated this event. Sadly, they were taken by Father time, but are not forgotten. We remember them with steadfast love and warmth. They made this a better place in which to live. They experienced the horrors of the Shoah, but showed us all how resilient they were and how committed they were to teach us, their children, the Lessons of the Holocaust.

20 A Southern Campus in the Age of Antisemitism BY

F.K. SCHOEMAN, PHD

22 Supporting Holocaust Educators in a Complex World BY JEFF

EARGLE, PHD

24 The Impact of Holocaust Education Today BY JENNIFER GOSS

26 Despair and Devastation, Resilience and Resolve BY

KAREN SHAWN, PHD

28 Educating the Next Generation BY FRANK W BAKER

29 Fulfilling Holocaust Education’s Failed Promise BY BOAZ DVIR

This publication is being mailed to community and school libraries, synagogues and churches throughout our state, and to individuals interested in the facts and history of the Holocaust.

If you wish to have a copy contact the SC Council on the Holocaust education @scholocaustcouncil .org . For all other questions check the SC Council on the Holocaust (SCCH) website: scholocaustcouncil .org

THE COVER

The Hall of Names at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

marcobrivio gallery / shutterstock com

30 “Are we prepared to teach the Holocaust?” BY TODD HENNESSY

32 What Makes For Effective Holocaust Education? BY HANNAH ROSENBAUM

34 The Status of Holocaust Education: Redefining Success BY SCOTT AUSPELMYER

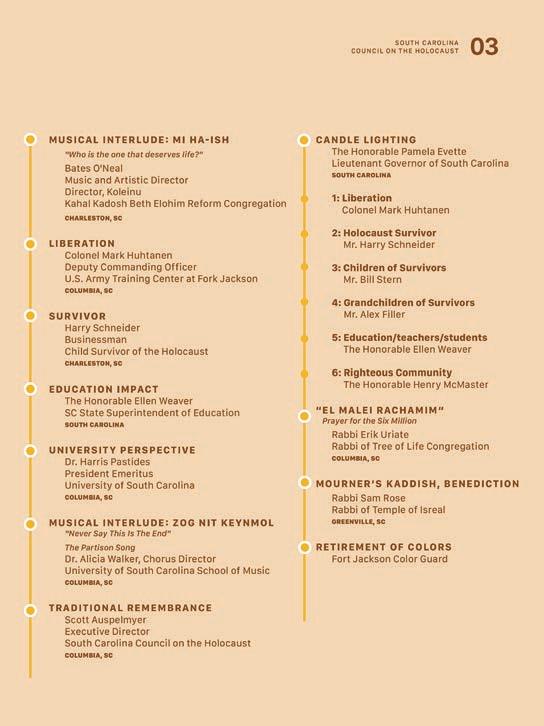

36 80th Commemoration of the Liberation of Auschwitz

39 International Holocaust Remembrance Day BY LILLY

FILLER, MD

BY ANDREW SILOW-CARROLL

“The Entire field of Holocaust Education, Remembrance, and Research is part of Yehuda’s legacy.”

An obituary for Yehuda Bauer, preeminent historian of the Holocaust, dies at 98

For his doctoral dissertation in history at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Yehuda Bauer focused on the British Mandate that before Israel’s independence controlled historic Palestine.

In a conversation with Abba Kovner, the poet who had led the resistance to Nazi rule in the Vilna ghetto, the young historian said he knew there was a larger story to tell but admitted that he was fearful of taking on a subject as monumental as the Holocaust.

Kovner convinced him that there was no more important event in Jewish history and that his fear of the subject was “a very good starting point.”

Over the next 60 years, Bauer, who died Friday at age 98, would go on to become perhaps the preeminent scholar of the Holocaust, chronicling in meticulous detail and pointed analysis the destruction of European Jewry, the unprecedented nature of the Shoah and the need to apply its lessons to prevent similar human catastrophes.

Kovner convinced him that there was no more important event in Jewish history and that his fear of the subject was “a very good starting point.”

BY MICHAEL BERENBAUM, PHD

Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies and Director of the Sigi Ziering Institute at the American Jewish University in Los Angeles, author and EmmyAward Filmmaker. Former Project Director overseeing the creation of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and former President and CEO of the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation. He is also a recipient of the 2024 “LIght of Remembrance” Award from the Auschwitz State Museum.

ATribute to Yehuda Bauer who died this week at the age of 98, productive to the very end, teaching to the very end, engaging in the most important issues of our time to the every end.

He was a scholar’s scholar and a teacher’s teacher. His knowledge was masterful. His ability to transmit what he knew even greater. Without simplifying the complexity of the information he presented, he was able to present it so clearly, so lucidly that one marveled at how one had previously regarded the issue as difficulty.

I learned about friendship by observing Yehuda Bauer. His partnership with Yisrael Gutman of blessed memory, with whom I worked closely on two books, was an example of that friendship, loyalty, camaraderie, respect, admiration, consideration, teamwork. Each was formidable in their own right; more formidable, more influential working together. And those of us who work in this field are acutely aware of the toll that it takes, and friendship is even more indispensable.

I learned about courage from Yehuda— courage and honesty. He said what he meant, he meant what he said. He spoke his mind, even when it made his audience uncomfortable.

I have experienced Yehuda Bauer as a critic, serious and pointed. I remember many a time in the early days of my work with the President’s Commission when his words were challenging, insistent that what he now calls the singularity of the Holocaust, its Jewish dimension be protected and not submerged. He challenged President Carter’s definition of 11 million based on Simon Wiesenthal’s invented but politically advantageous numbers, and was fearful of the false universalization of the Holocaust.

I had greater confidence that the Museum could adequately and accurately represent the totality of Nazi victims without negating, deemphasizing, or diluting the centrality of the Jews.

Yet, his voice became a voice of conscience and we were better off for his criticism, even for the fear of his criticism.

I learned and continued to learn about teaching from Yehuda. He expressed complex ideas with admirable clarity. He never believed that to be profound one had to be incomprehensible, or to be taken seriously one had to be obscure. He never spoke down to his students, but he was demanding. I took an undergraduate course with Yehuda at the Institute 59 years ago, when American students who spoke Hebrew could take mainstream courses. I barely remember

the subject or the syllabus .I do remember the exceptional teacher. And every time I heard him speak, whether to academics or a general audience, it is an event. I know I am in the presence of a master who has only gotten better with age, more liberated with age. His use of language, clarity of thought, breadth and depth knowledge, and use of the power of narrative are exceptional.

Most of all, I respect his values, Jewish values, humanistic values. He can be a denizen of many worlds, comfortable in many languages, at home in diverse cultures. His Jewish values inform and seek to enhance his humanistic values, and his humanistic values shape and even transform his Jewish values. He is comfortable with the tension between them when they clash: yet they dwell within him without tension but with fullness and wholeness. Within him, they become one.

It is perhaps important to note that despite the brilliance of Holocaust scholars in Israel and his many grateful there is no Israeli on the horizon who can quite fulfill his role in the world with such knowledge, such eloquence, such dignity, and respect.

His presence was a blessing, so too his memory!

SBY LAUREN B. GRANITE, PHD

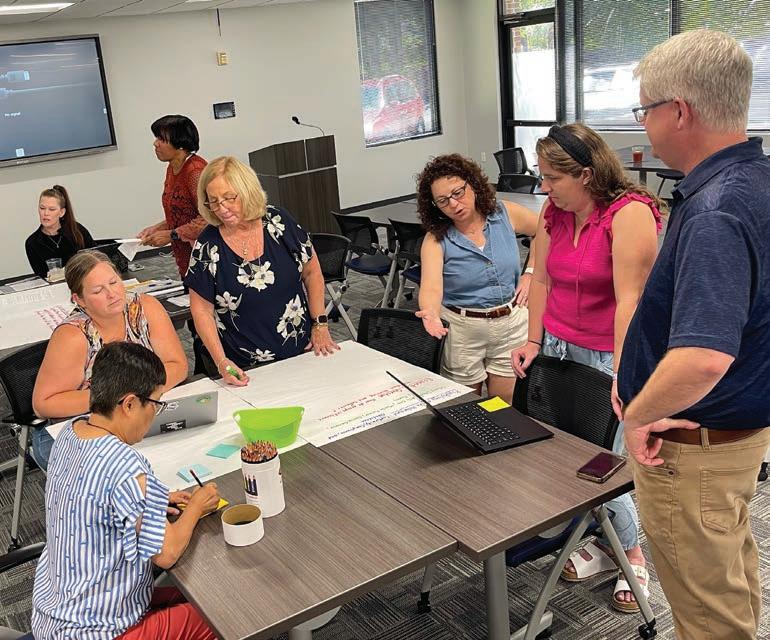

tories are universal and stories connect us all. That is why a 21st century student from rural South Carolina can relate to the story of a 20th century Jewish Slovakian girl who loved sports and vacations, overcame hardship, and rebuilt her life after devastating loss. In a world gripped by anger, fear, hateful rhetoric, and violence, connecting students to people their age in other countries—whether from 100 years ago through stories and photographs or today through cross-cultural projects—disrupts their assumptions about people who are different and teaches them that cultural gaps matter less than the common experiences of being human.

From 2000-2009, Centropa asked 1,230 elderly Jews in 15 Central and Eastern European countries to tell us their entire life stories as they shared the old family photographs that meant the most to them. Centropa digitized over 23,000 photos, creating a record of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe spanning the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire through the first decade of the 21st century. Using those photos, Centropa produces films—none longer than 30 minutes—each starting when the survivor was born and going to their senior years. Educators describe the power of learning the survivor’s entire life story:

“I believe in Centropa’s approach because it speaks to the larger truth that students must grasp to understand the Holocaust, namely that the victims were human beings. Students care for Centropa survivors because their stories begin with childhood memories and continue all the way into old age. They get to know the person, and, because of this, they care. To learn about the European Jews as victims only, without regard to the richness and complexity of their lives, tends to dehumanize their memory. This, of course, is antithetical to the goals of Holocaust education.”

Through photos and stories illustrating the richness and complexity of prewar, wartime, and post-war Jewish life, Centropa’s stories challenge misconceptions about Jews learned at home, on social media, or simply because students’ only exposure to Jews is the Nazi propaganda they study. Long-lasting learning requires disrupting what we think we know, or, as Holocaust educator Paul Salmons writes, “having to reorder our categories and our understandings.” 1

Centropa’s first-

person narratives and photos re-order students’ understanding of Jews by illustrating illustrating that European Jews before the Holocaust were not monolithic: They were urban and rural; assimilated and religious; wealthy, middle class, and poor; Ashkenazi and Sephardi. In addition, the academic emphasis on the acquisition of knowledge often disregards the emotional, spiritual, and even physical ways people relate to the world. Changing minds often means starting with hearts. Stories and images appeal to learners of all ages because they reach below the intellect to evoke an emotional connection—as this Virginia teacher conveys:

“When I was looking at the Centropa website in my classroom today, students asked me what I was doing. They

Stories are universal and stories connect us all. That is why a 21st century student from rural South Carolina can relate to the story of a 20th century Jewish Slovakian girl...

immediately started asking questions and wanted to explore the website as well. The images sparked curiosity and connections. They saw people with friends and wanted to show me their pictures too. They wanted to know who the people were and how they got there.”

With Jewish students threatened on campus and a worldwide rise in antisemitic violence, there are few more powerful ways to fight dehumanizing forces than cultivating curiosity about people who are—or seem—different.

This is why each summer, Centropa brings 70 teachers from 16 countries and diverse backgrounds to Central Europe to learn with scholars, visit historic sites, and spend evening after evening talking to Holocaust educators from Los Angeles to Tel Aviv, Charleston to Kiev, Thessaloniki to Vilnius. They create lifelong friendships and push one another to think beyond their own worldviews as they discuss thorny issues of pedagogy, Holocaust history, and contemporary social issues. Then their students get to know one

another and study the Holocaust together via Internet and social media programs. Why does this make a difference? People connected to individuals in other countries are more attuned to what happens to peers who are no longer strangers. When the war in Ukraine started, Centropa’s American teachers sent books and raised money for their Ukrainian colleagues. After October 7, US classes spoke with Israeli students via Zoom to learn what life was like for them following the massacre. A North Carolina teacher reported her class “asked the most questions [about the massacres], has wanted to know every few days what is currently happening, and has wanted me to cover some of the background information.”

With global antisemitism mounting, Centropa is more committed than ever to using stories and programs to challenge what teachers and students think they already know about Jews and the Holocaust. And by giving them opportunities to learn first-hand from people in other cultures, we create connections and disrupt assumptions— a powerful combination for opening minds.

In 1980 in Reidville, SC my father introduced me to Art and Esther. They were a bit older than my parents and were joining us for dinner. Ten year old me was excited about meeting these new people. I wanted to show them around the house and show them the new Mercedes-Benz my dad recently purchased. I vividly remember the pride my dad had for this dream car. Likewise, being his “shadow” I too was filled with pride. When dinner was over, my parents began clearing the dishes and preparing dessert. I took it upon myself to show Art and Esther my dad’s new “German” car and I hurriedly led them into the garage.

As we entered the garage I remember opening the car and encouraging them to sit in the leather seats. I sensed that something was amiss. Although they never sat in the car, the couple tolerated me until we returned inside where my parents awaited. The rest of the evening passed without incident, albeit I knew something was wrong. When the couple left, I told my dad what had happened. He told me he would explain soon. A couple of days later, my dad told me that Art and Esther survived the Holocaust. He did his best to explain antisemitism and the Holocaust. On another evening Art and Esther returned to my home to share their story of survival and show me their Auschwitz tattoos. I have little memory of what was actually said that night but the sight of the tattoos was etched into my mind. It was this moment and these people that

I contemplated while visiting AuschwitzBirkenau, staring down the train tracks. This event began my journey studying the Holocaust.

Teaching the history of the Holocaust is a noble and necessary task for South Carolina teachers. However, it is a task that is fraught with potential misperceptions and misunderstandings. So much so that some new teachers may try to avoid the topic altogether. Where does a teacher begin when under the most generous pacing, SC standards allow teachers only a few days on the topic. From the death

BY WILLIAM COX, EDD

camps like Treblinka, to pogroms at Kielce, to the ghettos of Warsaw and Krakow, a teacher’s primary task is what is most important to teach about the Holocaust.

Fortunately, I was doubly blessed with a father that introduced me to survivors who shared their experience and I experienced a teacher fellowship with the S.C. Council on the Holocaust. Through the council’s fellowship program, I spent two years studying the Holocaust and how to teach it. The Fellowship’s culminating activity was a trip to Poland. The much anticipated educational trip was more

Teaching the history of the Holocaust is a noble and necessary task for South Carolina teachers. However, it is a task that is fraught with potential misperceptions and misunderstandings.

than I could have ever imagined or hoped for, and was a fitting capstone to the experience. However, the most important aspects of the fellowship were the more mundane experiences leading up to the trip. The collegial group of teachers that read together, studied together, and ultimately traveled together for two years

helped me grow in my understanding of the Holocaust and how to teach it more than I can state. This group of teachers read widely and deeply about the Holocaust. We covered topics from basic understandings of the Holocaust, to the origins and growth of antisemitism, to the different stages of the killings. We studied

these topics together, we discussed how to implement the lessons we had learned together, we emailed, text messaged, and shared files and lesson plans seemingly on a daily basis. This collegial cohort was from all areas of South Carolina and represented the varied population of the Palmetto state. Rich schools, poor schools, lowcountry schools, midlands schools, and upstate schools, were all represented by this group of amazingly talented teachers and scholars. In short, the Poland experience was but the final amazing moment in a two year endeavor that challenged me emotionally, intellectually, and professionally. The trip to Poland was a success because we were able to engage in deep scholarship and intensive civil discourse with diverse colleagues allowing us to then teach our similarly diverse school populations. Through this fellowship program, the SC Council on the Holocaust has a powerful and profound tool to combat antisemitism in our state and beyond.

As I write this, I am preparing to teach the Holocaust in my US History class and as I have done since I started my fellowship, I will begin our lesson tomorrow with the story of a 10-year old boy meeting Art and Esther. Now that I have completed my fellowship, I have become a teacher worthy of telling Art and Esther’s story. I am a teacher equipped to tell the story of the many survivors and the millions of murdered victims in the hopes that it will never happen again.

BY EILEEN CHEPENIK

During World War II, Paul Pritcher was a liberator of Mauthausen Concentration Camp in Austria. In the early 1990s he was interviewed for a project of SCETV and the SC Council on the Holocaust to document testimonies of Holocaust survivors and liberators. This article is based on that interview. You can access his interview, as well as other survivor and liberator interviews on the Council’s website: www.scholocaustcouncil.org/survivor.php.

Only a few years out of high school, Paul Pritcher, from Orangeburg County, SC, was working at the Charleston Naval Shipyard when he was drafted into the US Army in November 1943 to serve in World War II. After training at Forts Jackson in Columbia and Shelby in Mississippi, he was assigned to the 65th Infantry Division and shipped to Camp Lucky Strike in LeHavre, France, in January 1945. He was 23 years old.

Historical note: This was shortly after the Battle of the Bulge, which occurred in December 1944-January 1945. This was the largest and bloodiest single battle fought by the United States during the war and was a major turning point of the war.

As a jeep driver in the Recon (Reconnaissance) Troop, Pritcher’s job was to gather intelligence information and bring it back to his regiment. They went to various towns in southern Germany to determine if there were any enemy forces. Along the way they encountered

a number of POW camps and proceeded into Austria, eventually meeting up with Russian troops in Enns, Austria, outside of Linz.

Just outside of Linz they encountered Mauthausen Concentration Camp.

Historical Note: Mauthausen was a system of interconnected slave labor and extermination camps. Between 1938 and 1945, around 190,000 people were imprisoned there. At least 90,000 died.

In the SCETV interview, Pritcher described what he saw.

“There were bodies strewn all over the place, all over the grounds, some stacked like cord wood, stacked on carts to be carried away, possibly for mass burial. Some of the areas we saw were where they were supposed to be able to sleep.

Pritcher stayed with the Occupational Forces around Austria and Southern Germany until May 1946. When he got home to South Carolina, he returned to his job at the shipyard.

There were bags of straw to be used as mattresses. There were very few live prisoners . . . we did not encounter any Nazis in the camp.”

“It’s hard to describe a condition that was so horrible,” Pritcher said in the interview. “My mind blocks it out. There were bodies that may not have starved to death but were on the verge of it. Unclothed. Skin and bones. They had sores all over them. It was a pitiful a sight.”

Pritcher’s group stayed in the camp only one day and returned to their base outside of Linz. He said he and his fellow

soldiers didn’t talk very much about what they saw, preferring instead to suppress the horrifying conditions they witnessed.

Pritcher also went to a POW camp in Ohrdruf. Like Mauthausen, the German guards had already fled, knowing the allies were coming.

“The biggest thing I saw when entering Ohrdruf were American soldiers standing by the wire begging for food. They saw American vehicles and knew we were coming to give them aid.”

“We only had two or three days of food for own consumption,” Pritcher said, “but we gave them everything. In less than an hour, we had nothing.”

Despite their hunger, the newly liberated prisoners shared everything, Pritcher said. For example, “we saw them share a chocolate bar that was about three inches long, enough for

one person, yet we saw 15 people eat from that one bar.”

Pritcher stayed with the Occupational Forces around Austria and Southern Germany until May 1946. When he got home to South Carolina, he returned to his job at the shipyard.

“When I got home, I was fed up with war and wanted to get it out of my mind as soon as possible,” Pritcher said. “Some of the memories have come back over the years. There are some things you can never forget.”

Pritcher passed away in 2003. His daughter, Paulette Wagener, recalls that he didn’t talk about the war to his children. “We knew he was in the war and that he liberated the camps” she said. They have seen his SCE-TV interview. Wagener once found photos her father had taken of bodies stacked like cord wood and emaciated POWs who looked like skeletons. After her father found out she had seen them, they disappeared. “I never saw them again,” she said. “He didn’t want his children to have that memory.”

BY DEBORAH TAUSSIG-BOEHNER

When my father, Vladimir Taussig, passed away in 1966, he left a suitcase filled with documents, photographs, letters, official reports, and other memorabilia. After I retired in 2012, I determined that it was time to understand its contents. As the intricate puzzle pieces of his life began to fit together, a complete picture emerged, and I realized his was a story that needed to be told. After 12 years of research, and collaborating with writer Lauren Housman, the story of my father, as well as his family, finally came together in our book, The Suitcase: The Life and Times of Captain X, which we dedicated to courage, decency, honesty, and tolerance.

The Suitcase is not only a story about my father’s remarkable, globe-trotting life, but also about the fate of his family who remained in Prague, as revealed by letters he received until 1941. These letters documented his family’s worsening plight as their world closed in on them. As time has passed and information has become more available, I learned details that my father would not have known: his brother’s job as an Aufbaukommando in Terezin, his mother’s death certificate from the same camp listing her death as “natural causes,” and the eventual transport of his brother and sister from Terezin to Auschwitz-II Birkenau. They did not survive.

My father’s experience with antisemitism was much more subtle and

insidious and speaks to the world-wide saturation of the sentiment.

Prior to a series of poor decisions that forced him to flee his native Prague for Shanghai in 1933, he was a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian Army and was transferred into the Czechoslovak Army after WWI when the democratic nation of Czechoslovakia was created. Though he lived in Shanghai when Czechoslovakia was occupied by Nazi Germany in 1939, my father was still considered to be in the Army Reserves, so he left his comfortable life and reported for duty with the Czech Army-in-Exile at the nearest open consulate.

Though he hoped to be sent to the front in France, he was ordered to return to Shanghai because there were “too many officers in France.” We now know, this was a convenient excuse because non-Jewish soldiers were refusing orders from Jewish officers and the top brass was concerned that the army presented as having a “highly Jewish character.”

Upon his return to Shanghai, he commenced carrying out orders from the Army-in-Exile: reporting back to the Czech officials from a “military point of view”, assisting

with the settlement of Czech Jewish refugees who arrived in Shanghai with nowhere else to flee; and recruiting and training those refugees to fight with the Army-in-Exile. He accomplished this by forming a Czech unit within the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, a multi-national local force. And yet, his frequent updates to the Army-in-Exile and requests to move his men to the front received no response.

He was Jewish, and, therefore, expendable. Only through his wit and determination did he persevere.

When he expressed frustrations with this silent treatment, British officials in Shanghai began to suspect that he may not be supportive of the Allied cause. A flurry of telegrams was exchanged between Shanghai officials and Government-in-Exile representatives in

London. All the while not only did the war rage in Europe, but there were also increasing tensions between the Chinese and Japanese. When my father had the opportunity to leave Shanghai prior to the inevitable Japanese occupation of the city, he received orders from the top Czech general instructing him to remain in place and await further instruction. Only later would my father come to understand, that the “supposedly democratic” (his words) Army- and Government-in-Exile for whom he had sacrificed time, money, and safety--training Allied troops right under the nose of the Japanese!--had an antisemitic bent. He was not supported as he followed their orders in Shanghai, nor was he supported upon his eventual arrival as a refugee in the UK, nor again upon his numerous later

attempts to emigrate to the States. He was Jewish, and, therefore, expendable. Only through his wit and determination did he persevere.

Eventually, through connections made in Shanghai, he secured a position as a propaganda speaker with the Ministry of Information, traveling throughout the UK and regaling audiences with his experiences in the Far East using various aliases including “Captain X,” Thus, the subtitle of our book, The Life and Times of Captain X.

In October 1941, my father received the last letter from his family in Prague. It advised him not to expect further letters. By then, they had been forcibly relocated on numerous occasions, eventually bound for Terezin.

The contents my father left inside his suitcase were a remarkable gift. Learning his story has been life-changing, and both Lauren and I encourage readers to explore select contents of the suitcase and learn more by visiting ReadTheSuitcase.com. Perhaps his message will do the same for you.

OBY PAT DIGEORGE, GRANDDAUGHTER

ur paternal grandfather

Israel Nathan Aron was born in 1886 in the shtetl of Rimshan, Lithuania. Israel was one of fourteen children, and his family’s fishery business prospered. In 1907, young Israel was ordered to join the Russian army, practically a death sentence for the Jews. He took the physical examination and passed, but before he could report for duty his mother bought tickets to America. Israel, soon known as I.N. Allen, settled in Nova Scotia where our father was born. Then after the depression, the family emigrated to the United States.

Years passed, and in the 1940s, I.N. was living in central Florida, where my parents joined him after World War II. The Allens raised five children in small-town Bartow. Regretfully, we never asked our grandfather about his early years in Eastern Europe, his parents, or his brothers and sisters. Certainly, there were no discussions about relatives who perished during World War II.

Then in 1980, fourteen years after the death of I.N., a letter arrived from Ramat Gan, Israel. It was written by

Dr. Menachem Mendel Leibavitch, the only surviving child of I.N.’s sister Leah Miriam. Dr. Leibavitch named who was “killed by the Germans” and who survived, adding addresses where possible.

When our mother died in 2007, we found a box filled with letters and photographs, all relating to our father’s side of the family. This is when using primarily online resources, I began to track down as many family members as possible.

Ancestry.com

With a free Ancestry.com account, I built an Aron family tree, beginning with the names in the 1980 letter.

In 2014 I discovered the Roswell, Georgia, Family History Center sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of LatterDay Saints. Similar centers exist all over the country. There, I was able to do more

When our mother died in 2007, we found a box filled with letters and photographs, all relating to our father’s side of the family.

extensive searches on Ancestry.com and found historical references for my grandfather. I added all this information to the online family tree.

Litvak Sig and Jewish Gen

These resources were invaluable as I identified family members. You can search for first name, last name, and city. Spellings vary so I had to search in many different ways.

Then in 2018, two things happened that accelerated our serious research. I paid for Ancestry.com’s World Explorer Membership, and my sister Kathy sent a sample of her DNA to 23 and Me. When her results were posted, she had hundreds of distant relatives. We messaged Natalya, a 2nd cousin, who answered immediately, “You need to speak to my aunt Sofia.”

Sofia is the granddaughter of I.N.’s sister Feiga. Their family survived the war in Soviet Russia, and Sofia had a treasure trove of Aron photographs, documents, and letters, written in Russian and Yiddish. Our goal was to find at least one member of each surviving family. One by one, this

happened and we began to communicate by way of Google Groups email.

I joined several Jewish Genealogy Facebook groups. One of I.N.’s sisters perished, but two children survived. A daughter married and emigrated to Australia. In 2019, I posted their names in the group “Tracing the Tribe - Jewish Genealogy on Facebook.” Four months later, I found this incredible comment: “Hi, you found us. My wife Karen is Tzvi’s daughter. PM me and I will fill you in more.” More names to add to our Google Group.

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, has a huge database of the names of those murdered. After the war, family members would submit pages of detailed testimony. I searched for Aron family members I knew had perished. In many cases, I discovered submissions for the same person by a surviving son, a nephew, or a cousin.

We found more than 99 close relatives who were murdered in the Holocaust ... Vilnius Ghetto, Klooga Estonia Forced

Labor Camp, Dachau, Lida, Częstochowa, Dolhinow Ghetto, Breslev, Salok, Stutthof concentration camp, and others.

Our Aron Family Google Group represents 9 of the 14 brothers and sisters. We deposited whatever documents, photographs, and letters we could find into Google Drive folders. Working together, it took a few years to put together a 112-page book of everything we knew about our shared family history.

One amazing resource was the online translated histories in JewishGen.org/ yizkor. The Yizkor books are stories written by survivors of the destroyed communities. I was able to find first-hand accounts of life in the home of my grandaunt Dvora and her family in Dolhinow during the months before they were murdered.

We are from the United States, Canada, Israel, Mexico, Brazil, France, Australia, Switzerland, and Lithuania. More than twenty times, the Aron Family has convened via Zoom for an hour or so to share our stories. Not only that, several have met in person in the United States, in Canada, and in Israel.

All the families collaborated and shared their stories, pictures, and documents. Few of us knew each other before this effort, and now we are miraculously and forever linked by the history of our ancestors, both tragic and joyful.

Ethel Stafford was interviewed in the early 1990’s for a project with SCETV and the SC Council on the Holocaust to document testimonies of Holocaust survivors and liberators. This articleis based on that interview. You can access the interview, as well as othersurvivor and liberator interviews on the Council’s website: www.scholocaustcouncil.org/survivor.php

Ethel J. Stafford was born on January 8, 1923, in St. Albans, New York, to a Norwegian father and Scottish mother. Growing up in a predominantly Scandinavian and German immigrant neighborhood, Stafford was exposed to diverse cultures from a young age. After completing her education at Andrew Jackson High School, she trained as a nurse at Cumberland Hospital in Brooklyn, graduating in January 1944. As World War II raged, she took on the role of an industrial nurse at Brewster Aeronautical Corporation, but her desire to serve led her to enlist in the U.S. Army later that year.

In June 1944, Stafford joined the 113th Evacuation Hospital, a mobile unit tasked with providing medical care close to the front lines. Her journey took her first to Great Britain, where she was stationed in Wales and England for several months. During her time there, she gained valuable experience at military hospitals. Soon after, Stafford’s unit was deployed to France, where they were part of

BY STACY STEELE

the Allied forces following the D-Day landings. They arrived in Normandy, and from there, Stafford’s unit moved across Europe, passing through France, the Netherlands, and Germany.

Stafford’s role in the war was pivotal as she served as an operating room nurse and later an operating room supervisor.

She described her grueling work, which involved long hours and the heavy responsibility of treating soldiers, often working 12 to 15 hours a day. Her unit cared for soldiers from American divisions, including the 102nd and 101st Airborne, as well as German prisoners of war. Despite the harsh circumstances of war, Stafford noted the professionalism and diligence of German prisoners under her care, reflecting a belief that, on an individual level, they were not much different from American soldiers.

However, it was Stafford’s experience at Gardelegen in Germany that would leave the most indelible mark on her. In April

Stafford reflected her disbelief that while Nazis meticulously cared for animals… the same care and humanity were utterly absent in their treatment of fellow human begins.

1945, Stafford’s unit arrived in the town of Gardelegen, where they encountered a horrific scene. The night before their arrival, Nazi forces had herded around 1,800 prisoners - primarily Polish and Dutch political prisoners and laborersinto a large barn, set it on fire, and locked the doors, ensuring that none could escape. Stafford described the shock of discovering the bodies, many of which were burned from the waist down. The scene was haunting, with evidence that

some prisoners had tried to claw their way out, only to meet a brutal end.

The stench, the brutality, and the sheer inhumanity of what Stafford saw at Gardelegen deeply affected her. She struggled to comprehend how anyone could perpetrate such cruelty, especially in a war that was nearing its end. As Stafford reflected on the event, she expressed disbelief that while the Nazis meticulously cared for animals - like the Lipizzan horses found nearby that were evacuated from Berlin - the same care and humanity were utterly absent in their treatment of fellow human beings. Stafford and her colleagues were tasked with overseeing the burial of the victims. German civilians from the town were forced to exhume the bodies and bury each one in individual graves. This was part of a broader effort by the Allied

forces to confront the local population with the atrocities that had been committed in their midst. However, Stafford noted that many Germans denied knowledge of the camp and the killings, a pattern she observed throughout her interactions with civilians during and after the war.

Stafford’s experience at Gardelegen stayed with her long after the war ended. Although she and her colleagues rarely spoke about what they had seen - partly out of the trauma and pain associated with it - Stafford felt a responsibility to ensure that the truth of what had happened was not forgotten. When her children were in high school, studying World War II, she shared her experiences with them, wanting to make sure they understood the reality of the Holocaust and the atrocities that occurred during the war.

For Stafford, it was crucial that future generations not fall into the trap of denial or indifference. She was acutely aware of the dangerous rhetoric that claimed the Holocaust was a fabrication, and she was determined that her children and grandchildren grow up knowing the truth. More than that, she wanted them to grow up in a world where people were respected for who they were, regardless of their race, religion, or background. Her experience during the war, especially at Gardelegen, shaped her belief in the importance of kindness, understanding, and respect for all people.

In a time marked by rising misinformation, a highly polarized society, and social media as the primary means of communication, the question of why and how to teach about the Holocaust is more pressing than ever. Research demonstrates that Holocaust education does make a difference, yet the impact is heavily influenced by how we teach it. With antisemitism alarmingly prevalent across the U.S., Holocaust education must go beyond recounting the tragic loss of six million Jewish lives.

Jewish Americans make up roughly 2.25% of the U.S. population, meaning many people may never meet a Jewish person. Effective Holocaust education can’t simply start with the events of September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. We must go deeper, providing background information on Judaism—teaching students what it means to be Jewish, and humanizing the Jewish people as individuals rather than historical figures. We also need to expand the narrative beyond the six million Jewish lives lost. While Jewish people bore the greatest brunt of the Holocaust, others—including gay men, political dissidents, Roma, and those who opposed fascism—were also

BY NATANYA MILLER

targeted. Limiting the conversation to one group risks fostering an “us versus them” mindset and overlooks the diverse identities within the Jewish community. We must teach students that Jews have been targets across history, even beyond the Holocaust, and reflect the range of Jewish identities. As a community, Jews must stand with all oppressed people. Many of us hold multiple identities - maybe we are women, identify as LGBTQIA+, a Jew of Color, or in an interfaith family. We cannot separate those

identities and only discuss our Jewishness. What about campuses? What is happening on our campuses is scary. There is no denying that. However, as with anything, we need to step back and understand that things are not always as they seem. We need to talk to the students who are on our campuses, and listen to them. Find out what they want and need. Combating antisemitism and hate starts with acknowledging the problem. We need to step away from social media, remove ourselves from echo chambers,

and engage in real, meaningful dialogue.

To do this, we must establish a common language. In any training or classroom, I begin with setting expectations and defining key terms. Shared understanding lays a foundation for respectful and productive conversations. Using precise language, rather than vague phrases or overused terms, helps convey complex ideas clearly and accurately.

For instance, what does a person mean when they say “Zionist” or “Zionism”? Are they referring to the concept of political Zionism or cultural Zionism? Are they in favor of a 2-state solution? So often we go into conversations with a preconceived notion of what the other person thinks, and we need to take the time to sit back and be open to hearing a different perspective and wait to respond.

When engaging in difficult conversations, a few principles can guide us:

1. Assume good intentions, even when it’s hard. Approaching others with an open mind often leads to better outcomes. The adage of catching

more flies with honey than vinegar is true. It isn’t always easy to see the person behind the comments, but it is important.

2. Be open and honest. Address offensive comments directly but constructively.

3 Ask questions. Instead of telling someone that their comment is harmful, ask them to explain what they mean. Often, when we have to slow down and explain ourselves we catch what we said and have the chance to do better.

4 Encourage questions; the only bad question is one that goes unasked. Better to ask questions and clear up misconceptions than to allow them to grow deeper.

5 . Interrupt harmful conversation. Be known as the person who is not ok with that type of rhetoric in your presence.

6 . Push back against stereotypes gently but firmly. For instance, if someone says, “So-and-so must be Jewish because they’re so cheap,” offer a counterexample that disrupts this stereotype.

While it may be tempting to share incidents of hate online, doing so can sometimes have the opposite effect, unintentionally amplifying hateful acts. Instead, we should focus on fostering real-world understanding and dialogue that addresses these issues directly and constructively.

Specializes

BY F.K. SCHOEMAN, PHD

On August 11, 2017, America watched aghast as White Supremacists marched through Charlottesville, Va., chanting Nazi slogans. Eventually, the chants turned into physical violence and one anti-Fascist protester was murdered and dozens injured by the end of that weekend.

A few days later, I entered the classroom of my Holocaust in Literature and Film seminar at the University of South Carolina, and for the first time in my career as a professor, I was seriously concerned for the safety of my 200 students and myself. There were some boys sitting in class wearing red MAGA hats, whose attitudes disrupted my lessons and whose body language was disrespectful. I was scared senseless. Because we know what the Neo Nazis mean when they chant “Jews will not replace us!”—they mean to kill us all.

In the summer of 2024, as I prepared for a new semester, I had a flashback to those days and to those fears. The protracted war Israel unleashed against Hamas, Hezbollah, and its inimical neighboring countries, in reaction to the heinous October 7 pogrom, awoke the antisemitic spirits of millions of people on American campuses and all over the world who, instead of merely protesting the politics of the Israeli government, took the unjustifiable position of attacking, vilifying, and ostracizing Jews as Jews—hence embracing an overtly antisemitic stance. They yelled at American Jews to “go back

to Israel” while simultaneously clamoring for the destruction of the State of Israel.

We know what the revolutionary leftleaning protesters mean when they chant “From the River to the Sea!”—they mean to kill all Israelis, and not to spare the Jews elsewhere either.

The cohort of students in my graduate seminar included newcomers from Nigeria, Bangladesh, India and France; half of the students were Christians, half were not, and there were no Jews among them. I was surprised so many students signed up for my Holocaust class. I wouldn’t have been shocked to hear that “in this climate” young people didn’t care anymore about the genocide of the Jews—past or prospective ones. Young idealists’ praiseworthy desire to side with and defend any victimized minority never seem to apply to the Jewish one. If October 7 demonstrated anything, it was that there is no mercy and no pity for the Jews.

I expected to enter a classroom where students wore hattahs around their necks, pepper-sprayed me, or disrupted my teaching with protest chants. But none of this happened. Not to me, not in my USC classroom. This is not to say that, tragically, Jewish faculty and students elsewhere have not experienced demonstrations of hatred, threats and physical attacks. On the one-year anniversary of the worst pogrom since WWII, the University of Maryland allowed Students for Justice in Palestine to hold an anti-Israel rally, thus coopting this date of mourning for the Jews to instead celebrate the murder of Jews.

My students surprised me with genuine curiosity and demonstrated great empathy for the Jewish plight, and horror upon learning of the brutal massacres throughout history that culminated with the genocide of 193945. A student asked me to explain what

Zionism is. Others wanted to know how one is allowed to critique Israel without crossing into antisemitism. I was grateful for the opportunity to discuss and explain. I pointed out that it is utterly legitimate to disagree on a political or ideological basis with the government of Israel. A position becomes antisemitic, I explained, when a double standard, not normally assigned to identical situations elsewhere, is applied to our judgment of the Jews as an ethnic, religious, or national group. One can oppose Benjamin

Netanyahu’s government and its actions; but lumping world Jewry into a hated category in light of what a government run by Jewish politicians does, or asking for the annihilation of an entire nation which happens, not coincidentally, to be Jewish, is no longer political discourse but antisemitic bigotry. My students were not antisemites. Perhaps I lucked out last semester. Or maybe geography is destiny. In the liberal milieus of Los Angeles and New York City, my Jewish colleagues experience a different reality from what my

southern location exposes me to. In South Carolina, thus far, the fascist revival is the most urgent problem Jews face.

On September 18, 2024, the institution where I teach allowed a group called “Uncensored America” to perform on our campus “The Roast of Cumala Harris,” featuring in the role of “roast-masters” the far-right Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes, and former Breitbart editor Milo Yiannopoulos. Our workplace became a zone of discomfort, terror, humiliation for women, Jews, and people of color. As per expectations, at the “roast”, Yiannopoulos spewed the vilest language, vented a hateful ideology, showed the photos of a selected group of faculty members intimidating them and characterizing many with racist, homophobic, misogynistic and antisemitic remarks. It was terrifying.

Antisemitism is as real today as it was in 1933. From both sides of the political spectrum, we hear a chorus of voices that more boldly than ever resort to old hateful tropes to fuel a desire in the masses to take action against the Jews, to punish them, to re-marginalize (if not eliminate) them.

The 2024 presidential election determined whether this nation could slip irremediably into a 1936-like situation. The answer disturbingly appears to be: Yes it can. Historically we have seen that while democracy is no shield against antisemitism, antisemitism is policy in Western dictatorships—it’s both their modus operandi and raison d’être.

In the end, though, Antisemitism is not a Jewish problem. It is an American problem. And therefore, it is the responsibility of this nation and its institutions of learning to align themselves with truth and justice and disavow pathological ideologies of hate that, unchecked, lead straight to totalitarianism.

Coming to the task of writing an article on Holocaust education prompts me to think about both the shifts in Holocaust education over the last decade and the challenges of supporting educators in our present time.

For many, the Holocaust was likely taught with a straightforward narrative: Hitler came to power. The Nuremberg laws were passed. The ghettos were created. Genocide occurred at killing centers such as Auschwitz. The Allied forces liberated camps and conducted the post-war Nuremberg trials.

While this narrative is not inaccurate, it lacks the complexity that Holocaust education currently encourages and that understanding the Holocaust demands.

Straightforward, easily digestible narratives often erase complexity. This is especially true of narratives around topics of persecution because the underlying bigotries and power dynamics that result in oppressive policies and actions can become ignored. Complexity, on the other hand, is needed in schools because students’ lives are not straightforward. Not only is complexity needed

to better understand a topic such as the Holocaust, but the transferable skills of complex thinking translate into students being better prepared to live and act in a complex world.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum defines the Holocaust as the “systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its allies and collaborators.” This definition encourages teachers and students to consider the nature and process of systematic oppression, the actions and inactions of a wide range of perpetrators, collaborators, and bystanders, and the underlying bigotries that made the Holocaust possible.

Teaching is not simply conveying facts to students. Good education develops

BY JEFF EARGLE, PHD

students as critical thinkers capable of civic engagement. Because of this, quality professional development for teachers must find a balance between content knowledge, methodology, and reflection.

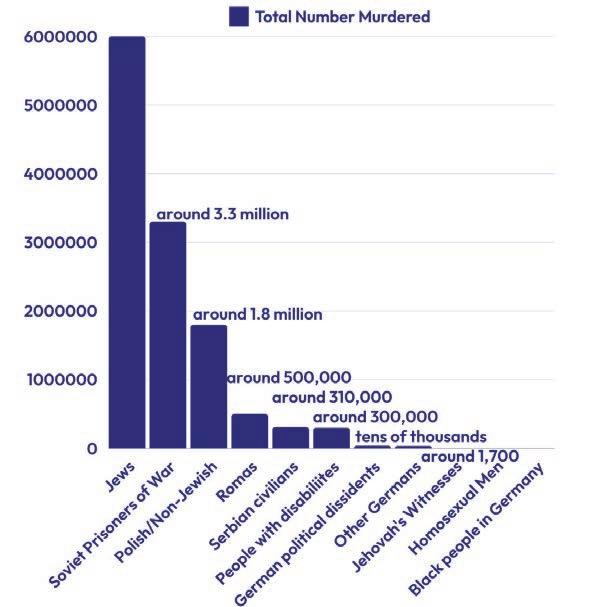

In my work, I partner with the South Carolina Council on the Holocaust to provide professional development for teachers. Each summer the Council, through the University of South Carolina, offers two courses for public and private school teachers. These courses are important in providing educators in our state with both content and pedagogical knowledge grounded in the latest research in Holocaust education.

When planning the courses, we consider three things. First, we focus on the process and complexity of the

Holocaust. Second, we give voice to the victims of the Holocaust. Third, we place the needs of teachers and students at the forefront of our planning.

In the six years of this partnership, I have observed several reasons why teachers are interested in taking the courses.

To begin with, teachers express an interest in learning about ageappropriate content, methods, and resources for the purpose of quality curriculum development. Additionally, they understand that teaching and learning about the Holocaust is important for teaching students to be aware of both human rights issues and civic responsibilities.

At the same time, teachers enter the courses confronted with a range of challenges. Some of these challenges are typical of any topic. For example, making decisions on how much time to devote to the Holocaust in a history or English class is a common challenge for teachers.

Additionally, there is a constantly evolving awareness and reconsideration of what material is appropriate for the classroom. Likewise, there is a greater focus on the victim-centered perspectives when it comes to topics of oppression, to include the Holocaust.

However, in the present time teachers enter the course seeking guidance and support on how to navigate the current sociopolitical context. For example, with the increased level of antisemitism, to include Holocaust distortion and trivialization, teachers have legitimate concerns about what they can discuss in class. This is compounded by our current politics which, by redefining complex topics as divisive, is marked by book challenges and other limitations placed on the curriculum that can affect Holocaust education.

These challenges prompts important questions from teachers for me as a facilitator of professional development.

The questions around the curriculum highlight the ongoing importance of quality professional development in Holocaust education. For me, that means providing teachers with an opportunity to engage in conversations in an academic, research-centered, and factbased environment that also has a practical understanding of the challenges they face. It means acknowledging teachers as skilled, knowledgeable, and professional educators capable of appropriate curricular decision-making and capable of guiding students through learning about the Holocaust and other complex and tragic events. Finally, it means embracing opportunities to study the Holocaust through a variety of disciplinary lenses. For example, integrating Holocaust education into geography, psychology, or biology courses in accurate and appropriate ways supports teaching the complexity of Holocaust.

While the current sociopolitical context seems to be moving the curriculum away from complexity, teaching the dangers of “systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder” demands complexity.

Fortunately, teachers working to provide students with an accurate Holocaust education have organizations offering support and guidance for teaching in a complex world.

TBY JENNIFER GOSS

eaching about the Holocaust has always been a complicated endeavor. It is not uncommon to hear educators are reluctant to teach about this subject because they do not feel that they possess appropriate content knowledge or they have concerns about the subject’s magnitude and its impact on students. October 7 brought an additional dimension to the equationeducator concern over teaching about the Holocaust amid the ongoing conflict between Israel and Hamas and the vicious cycle of media portrayal and rising antisemitism that surrounds it.

It is tempting for educators to turn away from tough topics in times of crisis but it is our job as members of the field to give them the tools and confidence to push forward. Since October 7, there has been much internal reflection on what is wrong with Holocaust education. Time and time again, my colleagues and I have encouraged reflection on this topic to instead think about what we are doing right and how we can do it better. Holocaust education is not perfect, but over the course of the past two decades, it has become a core part of the educational requirements in thirty states in the United States. It is also taught by dedicated individuals in the other twenty states and collectively, these lessons are making a difference.

How do we know this? There are plenty of anecdotal accounts from students in U.S. classrooms to attest to this fact. Recently,

Sara S., a New York student, shared with our team that she saw a marked difference in educator response to antisemitic incidents in her school. Educators who had received professional development and/ or were committed to teaching about the Holocaust effectively, dealt with incidents of antisemitism in their own classrooms in a more authoritative manner than other educators in her school who had not. Stories like Sara’s are not uncommon. Of course, anecdotal data is not the bucket we typically reach into to make informed decisions. Fortunately, there is plenty of quantitative and qualitative data from structured studies that we can also explore. In 2020, Echoes & Reflections released a survey of 1500 U.S. college and university students that showed that “positive outcomes of Holocaust education

not only reflect gains in historical knowledge but also manifest in cultivating more empathetic, tolerant, and engaged students more generally.”

Specifically, the survey found that college students who experienced Holocaust education in high school:

• Report having greater knowledge about the Holocaust than their peers and understand its value.

• Have more pluralistic attitudes and are more open to differing viewpoints.

• Report a greater willingness to challenge intolerant behavior in others.

• Show higher critical thinking skills and greater sense of social responsibility and civic efficacy if they watched survivor testimony as part of their experience.

While these findings demonstrate to reluctant educators the importance of including this subject in their classrooms, they do not address the issue of rising antisemitism. Even prior to the tragedy of October 7, antisemitism has been on the rise in the U.S. and in the greater world community. There are a variety of factors that feed into this rise; however, that

would merit an entirely separate piece. Instead, it is worth noting that there are a variety of ways in which we can combat antisemitism, including through Holocaust education. In March 2023, the Center on Antisemitism Research at ADL released findings from a survey of a nationally representative sample of 4,000 Americans performed in late 2022. The purpose of

this survey was to, “better understand attitudes toward Jews and Israel.”

The survey “suggests a direct relationship between deficiencies in Holocaust education and heightened prejudicial, antisemitic beliefs. Our findings reveal that believing in antisemitic tropes strongly correlated with a lack of knowledge about Jews, Judaism, and the Holocaust.”

Therefore, one can see a connection between individuals who learn about the Holocaust and those who are much less likely to possess antisemitic belief systems in adulthood. One of the most effective ways to build awareness and knowledge about the Holocaust is through education of secondary students nationwide. Holocaust education should not be the only vehicle to combat antisemitism but it is one that is already part of many classrooms and therefore, can provide a crucial foundation.

This brings us to the present—first, it is imperative that we continue our work to teach about the Holocaust in a complicated world. It also brings us to a point of reflection. In what ways are we doing this well? How can we improve classroom practices to further combat antisemitism and hatred? How can we make effective practices a part of every classroom? By working together to grapple with these questions, we can take the solid understandings we already possess related to Holocaust education and truly create a better world for all.

BY KAREN SHAWN, PHD

Holocaust education is in the spotlight during these turbulent times. Recordhigh antisemitism infects the globe, and the misconception abounds that teaching about the Shoah should, by definition, lessen, if not eliminate, this plague. Educating about the Holocaust, however, is not the cure for antisemitism, a disease for which there seems to be no remedy. It has been with us for centuries, sometimes festering in dark, hidden places, sometimes crawling up from tunnels, as it is today, discharging its toxicity openly in countries worldwide. Antisemitism throughout the ages, its causes, and its results require serious study. This subject is multi-layered, difficult, painful to learn and to teach, and one cannot understand the Holocaust without at least a general understanding of Jew-hatred, its root cause. But learning about the Holocaust has no innate power to stop this scourge of antisemitism and, currently, of anti-Zionism.

October 7th and its aftermath have made teaching about the Shoah even more complicated. Is this most recent assault another Holocaust? To help us explore this question, director Dr. Shay Pilnik and I, of Yeshiva University’s Fish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, designed a three-credit summer study course for our graduate students. Fifteen of us spent 10 days in Israel in July 2024 visiting Holocaust museums and centers to learn how educators there are

teaching about the Holocaust in light of October 7th. We stayed in hotels where Israeli families have been living for many months because their homes were either destroyed by Hamas terrorists or, if in the north, are in grave danger daily of being destroyed by rockets from Hezbollah. In Tel Aviv’s Hostage Square, we stood silently by the long Shabbat table set and waiting for the hostages kidnapped and held by Hamas to come home. We visited Har Herzl, paying our respects at the graves of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers who lost their lives establishing and then defending the State

of Israel, and we mourned those fighters killed on October 7th and in this past year defending Israel against terrorists. We traveled south and witnessed the devastation and destruction of Kibbutz Kfar Aza, one of some 60 kibbutzim attacked by Hamas marauders [Fig. 1].

We visited the site of the Supernova Music Festival, where the killers slaughtered some 340 revelers and kidnapped others [Fig. 2].

We stood, aghast, at what has become an impromptu car memorial, where many hundreds of cars, burnt, bullet-ridden, or machine-gunned almost beyond

“I know, though, that October 7th and its aftermath have made teaching about the Holocaust ever more complex.”

recognition, rest in silent testimony to the brutality of Hamas, who gleefully destroyed the cars and their terrified occupants as they tried to flee to safety [Fig. 3].

Clearly, education about the Holocaust did not prevent this most recent atrocity against the Jews. In fact, Mein Kampf was found in a terrorist hideout.

In speaking with Israelis, we learned that many maintain that October 7th was not another Holocaust. We have a

state now, and Israel has a world-class army and air force; during the Shoah, Jews had no haven and no defense. However, we learned as well that some survivors of October 7th, as well as some of the hostages who have been rescued, report that the devastating trauma they experienced felt to them like a Holocaust. We respect and accept those feelings.

We do not yet have the language to accurately describe what happened on

that day and in the aftermath, so we fell back on familiar words as we studied previous hate-fueled murders of Jews. We understood that we must offer an open, listening heart to October 7th survivors and to the hostages who have survived, receive their experiences, and believe them; they must not wait, as Shoah survivors waited, to have their voices heard. We applauded the multitude of Israeli individuals and institutions that offer ongoing physical, psychological, social, and financial help and support to them and their families, as well as to injured soldiers.

Because the war continues as of this writing, I draw no conclusions about if or how these two events will be related and examined in American classrooms. I know, though, that October 7th and its aftermath have made teaching about the Holocaust ever more complex. The Fish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies offers an Advanced Certificate in Holocaust education, a 12-credit program designed for middle and high school educators. Engaging with peers and world-class professors can guide and support us in our struggle to find appropriate and thoughtful ways to teach it in these fraught times.

Today’s “digital natives” may be able to code, play videogames, and text nimbly, but that does not mean they are media literate.

For 25 years I have traveled the state, advising educators and students how to use critical thinking AND critical viewing skills to better understand the mediated world in which we live.

Critical viewing skills is a phrase I first learned about 30 years ago. I was surprised when teachers I witnessed misused video in the classroom by not engaging students in previewing questions, introducing vocabulary and post viewing understanding.

In 2025, visual literacy (“the ability to read, write and create visual images”) becomes even more important. I would add the word QUESTION to this definition. Why is visual literacy important? Because we live in a world of deepfakes (videos), artificial intelligence and constantly altered images. Seeing is no longer believing.

I was invited to conduct a visual literacy lesson during one of the South Carolina Council of the Holocaust’s summer teacher workshops. I introduced an image, without a caption, and invited educators to consider just the image. What could they infer from just the photo itself? I also encouraged them to consider questions like:

• what do I know or NOT know?

• where can I go to get reliable

information that I can verify?

Are today’s students prepared to read and understand visual images? We would probably find this kind of instruction in an arts classroom, but what about history?

The social media many young people attend to is highly visual and many of them may already have been exposed to antisemitic memes.

A meme is defined as “an image, video, piece of text, etc., typically humorous in nature, that is copied and spread rapidly by internet users, often with slight variations.”

Many may recall the propaganda posters utilized by the Nazis against the Jews during WWII.

They contained stereotypes and exaggerated images of Jews. Today’s educators may use these images as examples of propaganda-- challenging students to deconstruct the image and its possible effect on the population at the time.

Today’s memes are similar. “The Happy Merchant” is an antisemitic meme depicting a drawing of a Jewish man with heavily stereotyped facial features who is greedily rubbing his hands together.”

“There are about seven antisemitic tropes that we see being packaged and repackaged consistently in social media spaces-- blood libel, global domination, power and conspiracy, replacement theory, disease and filth, deicide charge, wealth and greed, Holocaust denial, and distortion.” https://www.facinghistory.

BY FRANK W BAKER

org/resource-library/deconstructingantisemitic-memes

Visual literacy skills can be powerful and effective ways for students to counteract what they consume online. But the big question is: are today’s teachers prepared to help students understand the memes and tropes they may be seeing online?

Like media literacy, visual literacy skills involve not only studying the message but also questioning it. Teachers would be wise to engage students in questions like:

• what’s going on in the image?*

• what message or emotion might the creator be attempting to convey?

• what is the historical/social context to which the image is being used and how does it make you feel?

• how might people different from me, react to this image differently?

• What can students do if they encounter memes/tropes? Facing History advises:

• Don’t share them. Instead, slow down, analyze and question them.

T here will always be bad actors spreading messages of hate. It’s up to parents and educators to ensure 21st century students have the knowledge, skills and ability to think critically about all media.

BY BOAZ DVIR

Afew years ago, I screened a rough cut of one of my documentaries, Cojot, at a major university. The nonfiction film, which I’ve since retitled To Kill a Nazi, tells the story of a Holocaust survivor, Michel Cojot, who set out to assassinate his father’s executioner, Gestapo Commander Klaus Barbie. After the program, two freshmen approached me saying they’d “never heard of this.”

Few people are familiar with Cojot’s story, I told them in a reassuring voice. That’s why I made the documentary. The freshmen shook their heads, noting they’d “never heard about any of this.” They were talking about the Holocaust.

The interaction confirmed what I’d long suspected: Holocaust education has failed to deliver on its most basic objective—raising awareness about the Nazis’ systemic murder of 6 millions Jews and millions of others. Young Americans, according to polls, lack “basic knowledge” about the Holocaust. Two-thirds of them lowball the number of Hitler’s Jewish victims.

This, despite the fact that Holocaust education has been part of the American educational system for half a century high-, middle- and elementary schools around the U.S. have taught the Holocaust since the 1970s. Twenty-six states mandate its instruction. Many of the 24 other states run councils and commissions to help teachers tackle this topic.

Holocaust education was expected to do more than simply disseminate historical facts. It was supposed to uproot antisemitism and other forms of hate. But on this front, too, it has disappointed. K-12 schools’ reported antisemitic incidents jumped 50 percent in 2022 over the previous, record-breaking year. And that was before the Israel-Hamas War, which led to a 140 percent increase in 2023. Islamophobia, meanwhile, rose 216 percent in the month following Oct. 7, 2023.

Yet, as the grandson of Holocaust survivors who has explored this topic in a variety of ways over the years, I continue to believe Holocaust education can achieve its lofty goals. That’s why I created Penn State University’s Holocaust, Genocide and Human Rights Education Initiative. We provide research-based, intensive, nonpartisan professional development (PD) to K-12 educators on how to get at the underlying causes of the Holocaust through a variety of difficult topics.

Our participants come from an array of disciplines and roles. They obtain the confidence to teach difficult topics in responsible, effective ways by coming up with guiding questions, seeking credible sources, gathering and examining data, reviewing the findings with their peers and scholars, and creating classroom application plans. The students conjure up their own compelling questions and figure out the answers for themselves through their own learning journeys.

In the process, the students develop critical thinking, fact-finding, active listening, and civic discourse skills. They gain agency, empathy, and insight into how democracies prosper and falter.

The Initiative’s pedagogy is made up of five components. At its core is practitioner inquiry/action research, a well-established PD tool that enables K-12 educators to study and advance their practice. Around it are four lenses: trauma-informed, which guides teachers on the usage of age-inappropriate content and helps them deal with trauma among their students; apolitical educational equity, which says every student counts; asset-based, which steers clear of education’s default deficit orientation and highlights the teachers and students’ strengths; and contextual responsiveness, which helps teachers meet their students where they are.

Our research shows this approach is working. So far, we’ve published three papers in peer-reviewed journals, including the top-ranked Journal of Teacher Education. Some of the experts who’ve reviewed our methodologies, data, and results have described our approach as “novel, innovative and widely needed.”

Based on our findings, we feel optimistic that a national adoption of this approach would fulfill Holocaust education’s great promise.

“Are

DBY TODD HENNESSY

oes this come from hours of instruction while completing a degree?

If so, which degree? Is it our familiarity with numerous and varied survivor testimonies? If so, which testimonies? It may be the number of books or publications we have read, but then, which ones? Or, was it that unexplainable sensation of walking along the same path as those who experienced it while at a site dedicated to the memory of what took place there?

How many victims do we name? By name. Not number.

Can we recognize significant dates and their cause-and-effect relationships within the narrative’s timeline? How comfortable are we with the geography of the

Holocaust, not just the cities and borders but the historical regions, the physical features, and the human interaction that defined the landscape centuries before?