nutriNews International is starting the year with the right foot. All is set to make this year a good one. Scientific discoveries, new technologies and approaches, insights to better understand and manage the complex world of animal nutrition, many topics to share with you in this first edition for 2024.

New boundaries are to be conquered as we start exploring and understanding how enhancing resilience in pig nutrition offers advantages in farm management, animal welfare, and economic performance. With continued research and implementation, the future of pig farming can be more resilient, sustainable, and profitable.

The world of vitamins in modern production

In the intricate web of life, where every organism thrives on a delicate balance of nutrients, vitamins emerge as unsung heroes. These tiny organic compounds play pivotal roles in the conception, development, and sustainability of life. Vitamins are essential nutrients for livestock, playing critical roles in various physiological processes. They are crucial for growth, reproduction, and overall health, thus providing adequate vitamin levels is very important. It’s time to shine a spotlight on the profound impact vitamins have on poultry and swine production.

In the realm of livestock production, where efficiency and profitability are paramount, the formulation of diets stands as a cornerstone for success. It’s widely acknowledged that feed represents a significant portion, often 60-70%, of production costs. Yet, too often, once diets are formulated, there’s a common temptation to consider them complete and static. The reality is that nutrient content and ingredient prices are in constant flux. Changes in crop yields, market demands, and external factors influence ingredient availability and prices. Moreover, variations in nutrient levels within ingredients can occur, impacting diet consistency and animal performance. The question then arises: when should diets be reconsidered or reformulated? You can find some insights in this edition.

Digestible phosphorus is a critical nutrient in livestock nutrition, influencing growth, health, and environmental sustainability. By understanding the factors that affect phosphorus digestibility and implementing appropriate management practices, livestock producers can optimize phosphorus utilization in their animals’ diets, leading to improved performance and reduced environmental impact.

Enjoy reading about these and other interesting topics in this edition of nutriNews International.

Álvaro José Guzman

04 New

Abdelhacib Kihal DVM, MSc, PhD

22

Gwendolyn Jones PhD

16 Why

Gabriela Martinez Padilla PhD

Edgar O. Oviedo Rondón Prestage Department of Poultry Science, NC State University

Dr. med. vet. Volker Wilke

42

Advances in Poultry Nutrition IPS2024

Edgar Orlando Oviedo Rondón Prestage Department of Poultry Science, NC State University

50

Evaluation

Miguel Alberto Pérez Espinoza, Benjamín Fuente Martínez, Ezequiel Rosales Martínez CEIEPAv-FMVZ-UNAM and Center for Applied Research in Poultry Nutrition of Maringá.

59

The Importance of Vitamins in Modern Poultry Farming

Sérgio Gonçalves Mota and Geovana Rocha Placido

65

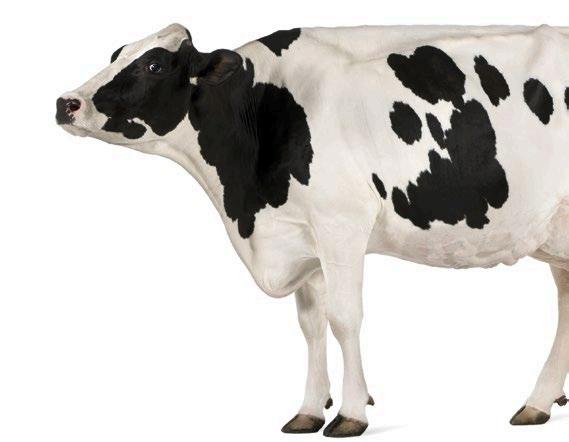

Amino acids in the feeding of cattle (Part 1)

Beatriz de Magalhães Ceron and Breno Luis Nery Garcia

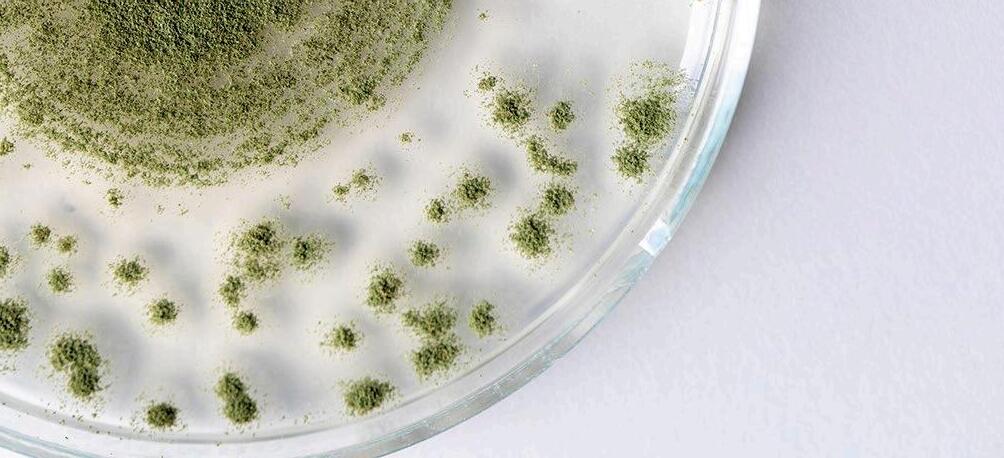

Mycotoxins pose a significant challenge to animal production, with their prevalence in raw materials or feed subject to variations related to changes in climatic conditions.

For instance, droughts or years with high rainfall impact the types of fungi that proliferate in certain regions (Moretti et al., 2019).

There are different methods to control the impact of mycotoxins on animal production, ranging from monitoring their presence in raw materials during pre-harvest and post-harvest stages to detoxifying animals exposed to them through contaminated diets.

Mycotoxin adsorbents are active in the gastrointestinal tract of animals, with mycotoxins binding to the adsorbent matrix through various physicochemical interactions.

The use of mycotoxin adsorbents (ADS) is widely recognized as an

There are different types of adsorbents, with the most common being clays, activated carbon (AC), and yeast cell wall (LEV). Their interlayer space, pores, and β-glucans represent their key adsorption factors, respectively (Jouany, 2007).

Clay

Interlayer space

Pores β-glucans

Yeast cell wall

Clay

Interlayer space

Pores β-glucans

Yeast cell wall

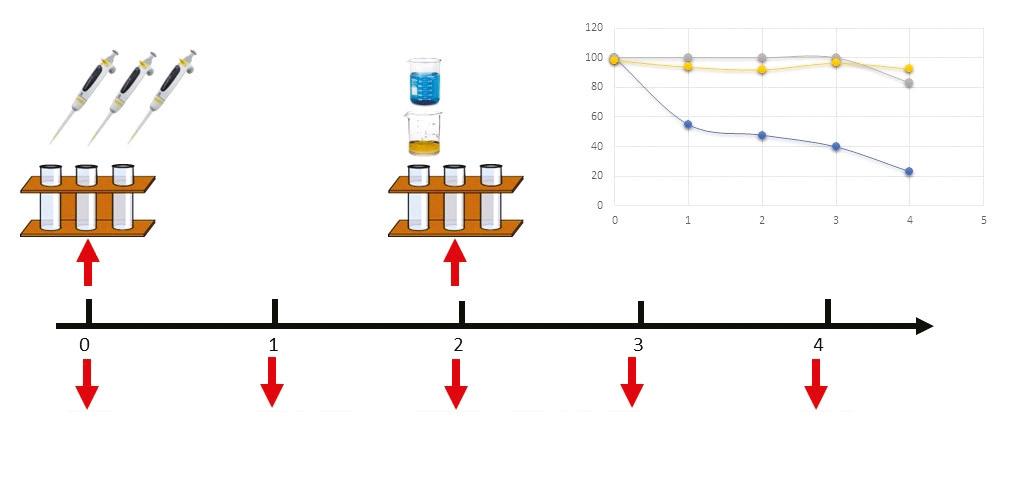

To determine the efficacy of mycotoxin adsorbents, in vitro tests are primarily used, allowing the evaluation of a large number of adsorbents and mycotoxins. These tests have the advantage of being rapid and cost-effective compared to in vivo tests.

However, there are many variations of in vitro tests that have been developed over the years, attempting to simulate the processes of the gastrointestinal tract of animals.

The problem with these methods is the high variability of the results of mycotoxin adsorption.

These protocols vary in complexity, from a simple test with distilled water and incubation at room temperature (Lemke et al., 2001) to more complex methods that simulate the processes of the animal gastrointestinal tract using different pH values and including gastrointestinal enzymes, or using gastric juice as the incubation medium (Avantaggiato et al., 2004; Gallo y Masoero, 2010).

Determining the adsorption capacity of mycotoxins in in vivo tests is essential to demonstrate the actual effectiveness of the product.

Unlike in vitro tests, in vivo tests replicate field conditions and the animal's response to the supplementation of adsorbents in the presence of mycotoxins in the diets.

To shed more light on the concordance of results from in vitro and in vivo studies, a network meta-analysis was conducted on data published in the literature from studies evaluating the effectiveness of different adsorbents in reducing the concentration of aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) and its transfer from feed to milk after challenging

Unfortunately, this diversity of experimental protocols has resulted in high variability in the results of the adsorption capacity of adsorbents (Kihal et al., 2022).

The key finding of this study was that the effectiveness of different sources of adsorbents [activated carbon (CA), bentonite, aluminosilicates (HSCAS), yeast cell wall (LEV), and a mixture of adsorbents (MIX)] significantly reduced the percentage of AFM1 in milk compared to the control.

These results confirm the effectiveness of adsorbents in adsorbing aflatoxins from in vitro assays, although the adsorption percentage in vivo was lower. Furthermore, the percentage reduction among different adsorbents in vivo was not different, demonstrating a similar effect among the different adsorbents.

It is important to note that the number of in vivo studies was lower than the number of in vitro studies included in this meta-analysis (28 versus 68 articles).

This difference may have an effect on the variability of results, leading to high variability between treatment comparisons.

In vivo studies, unlike in vitro tests, are complex, expensive, and challenging to implement:

They require the application of biosafety protocols to handle mycotoxins at the farm level.

The necessary facilities are not available in most research centers.

Additionally, similar to in vitro tests, in vivo studies must be conducted under experimental conditions to avoid misleading results.

Defining the adsorbent-to-mycotoxin ratio is a common challenge in both in vitro and in vivo studies since working with inappropriate proportions can either favor or unfavorably impact the mycotoxin adsorption results.

The way of contaminating the feed in experimental trails is also a key factor in assessing adsorption capacity.

For example, supplementing naturally contaminated feeds may affect the results compared to direct supplementation of pure AFB1 into the cow's rumen.

This is because naturally contaminated feed may contain different types of aflatoxins (AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, or AFG2) or other mycotoxins, resulting in synergy or competition phenomena due to binding to the tested adsorbent.

The raw material used for the fungus's development is very important, as fungi utilize nutrients from the contaminated grain for their growth. Using different types of grains can also affect the fungus's development and the production of mycotoxins.

Nevertheless, in vivo experiments are the best method to test the efficacy of adsorbents and allow for a deeper understanding of the products' performance in animals.

The review of the results from in vitro and in vivo studies of adsorbents (Kihal et al., 2023) confirmed that their aflatoxin adsorption capacity in vitro was similar to in vivo experiments, where different adsorbents (activated carbon, bentonite, and HSCAS) successfully reduced the AFM1 concentration in milk in a range of 26-45%.

26-45%

On the other hand, the LEV showed the lowest adsorption capacity in in vitro tests, which is consistent with in vivo tests where it was the least effective adsorbent in reducing the transfer of AFM1 in milk.

It should be noted that the use of adsorbents in vivo resulted in a lower adsorption capacity compared to in vitro results, with a decrease of more than 50% for CA, bentonite, and LEV, and a decrease of 67% for HSCAS.

In this regard, it is suggested that under in vivo conditions, the contents of the gastrointestinal tract (enzymes, nutrients, bacteria) interfere and compete with mycotoxins for adsorption sites on adsorbents, leading to an overall decrease in capacity. This contrasts with in vitro conditions where the incubation media contain fewer organic molecules.

WHAT IS

POTENTIAL OF MYCOTOXIN ADSORBENTS TO INTERFERE WITH THE ADSORPTION OF OTHER NUTRIENTS, AND WHICH IS THE BEST TOOL TO VERIFY IT, IN VITRO OR IN VIVO?

Recent studies in our laboratory have shown that the adsorption capacity of mycotoxin adsorbents is affected by:

The type of adsorbent

The mycotoxin

The characteristics of the incubation medium

(Kihal et al., 2022)

Additionally, this capacity could be altered by the interaction of nutrients present in the same environment with mycotoxins, both in vivo and in vitro

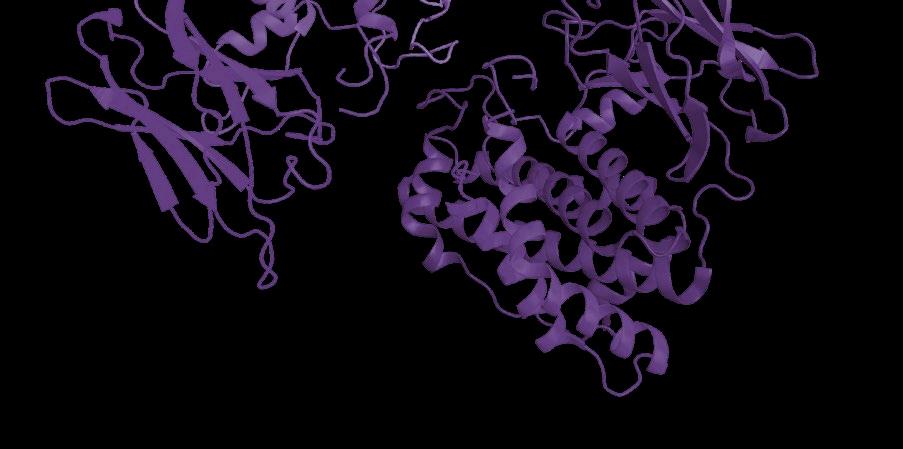

The adsorption mechanism of adsorbents is not selective to bind only to mycotoxins; they can also adsorb other molecules present in the animal's gastrointestinal tract, such as nutrients.

This ability to bind to nutrients is attributed to the physicochemical similarities of some nutrients with mycotoxins that allow for their interaction.

The ability of adsorbents to adsorb nutrients has been studied using in vitro models.

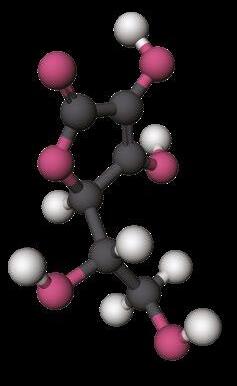

Kihal et al. (2020; 2021) studied the interaction of six different adsorbents with amino acids and vitamins.

The authors noted an adsorption range of 27-37% for amino acids, 25-58% for watersoluble vitamins, and 10-29% for fat-soluble vitamins.

Vekiru et al. (2007) also observed that activated carbon (CA) adsorbed a large proportion of vitamin B8 (78%) and B12 (99%), while bentonite had lower adsorption of vitamin B12 (47%).

Barrientos-Velázquez et al. (2016) reported that bentonite absorbed 34% of vitamin B1, and simultaneously, the adsorption of aflatoxins was reduced by 34%, indicating direct competition of other nutrients for adsorption sites.

Mortland et al. (1983) reported that smectite has the capacity to adsorb vitamin B2 (50%).

It has also been observed that bentonite and montmorillonite adsorb proteins in an in vitro model (Ralla et al., 2010; Barrientos-Velázquez et al., 2016).

The ability of adsorbents to adsorb minerals was also investigated in vitro by Tomasevic- Canovic et al. (2001) who observed a high capacity of bentonite to adsorb copper (56%) and cobalt (73%), while the adsorption of zinc (12%) and manganese (12%) was relatively low.

On the other hand, vitamins A, D, B3, B5, and B8, as well as the amino acids tryptophan and phenylalanine, were not adsorbed by bentonite and zeolite (Tomasevic-Canovic et al., 2001; Vekiru et al., 2007; Kihal et al., 2020).

These results were mainly attributed to the physicochemical properties of each nutrient.

The adsorption capacity of watersoluble vitamins was higher due to their low molecular weight and the presence of more than one hydroxyl or carbonyl group, ensuring stable adsorption with the adsorbents.

The adsorption of vitamin D was lower due to its higher molecular weight and the presence of different branches that hinder its entry into the adsorbent's adsorption sites.

GREATER ADSORPTION

Low Molecular Weight

Hydroxyl or Carbonyl groups

LOWER ADSORPTION

High Molecular Weight

Ramifications that obstruct access to adsorption sites.

Despite these results, there are technical challenges when applying these methods to some nutrients, as some of them are sensitive to environmental factors and may undergo alterations during incubation.

Kihal et al. (2021) observed that vitamin A disappeared from the incubation medium after 4 hours of incubation, making its assessment unfeasible, while vitamins D and E were more stable during the degradation kinetics and showed over 90% stability.

Díaz et al. (2004) pointed out that the results of in vitro tests should not be considered as final outcomes and suggested that in vivo studies should be conducted for more reliable results.

The bioavailability of nutrients in the presence of mycotoxin adsorbents has also been studied in vivo.

Briggs y Fox (1956) observed that supplementing chicken diets with 2-3% bentonite resulted in a vitamin A deficiency.

The zinc content also decreased in the bones of chickens after supplementation with 0.5 to 1% HSCAS in the diet (Chung et al., 1989).

In contrast, Afriyie-Gyawu (2004) and Pimpukdee et al. (2004) observed that the inclusion of 0.5% bentonite did not affect the concentration of vitamin A in the liver, and Chung et al. (1989) found that the inclusion of HSCAS did not affect the bioavailability of vitamin A, vitamin B2, and manganese in

Sulzberger et al. (2016) and Kihal et al. (2022), after supplementing dairy cows with 1.2% and 2% montmorillonite in the diet of dairy cows, also did not observe changes in the plasma concentration of vitamins A, D, E, B1, and B6.

Maki et al. (2016) supplemented HSCAS to dairy cows at 1.2% of the dry matter of the diet and did not observe negative effects on the bioavailability of vitamins A and B2 in milk.

These results might suggest that in vitro tests are not entirely reliable, and we should be very conservative when referring to

In addition to the factors limiting the specific interaction between adsorbents and mycotoxins, the adsorption mechanism of adsorbents is saturable and depends on the number of adsorption sites available for mycotoxins in the matrix.

For this reason, the adsorbent:mycotoxin ratio is an essential factor in in vitro tests where the adsorption capacity can be easily manipulated:

High concentration of adsorbent and Low concentration of mycotoxins: Incubating a high concentration of adsorbent with a low concentration of mycotoxins will result in a higher adsorption capacity of the tested adsorbents because there are more adsorption sites available than mycotoxins present in the medium.

Low concentration of adsorbent and High concentration of mycotoxins: Incubating a low dose of adsorbent with a high dose of mycotoxins will lead to a lower adsorption capacity due to the saturation of available adsorption sites on the adsorbents.

(Sulzberger et al., 2017)

Using the selected data for the in vitro adsorbent efficacy analysis, the adsorbent:mycotoxin ratios used in current techniques resulted in a very wide range of ratios regardless of the type of mycotoxin or adsorbent (1:0,00007 to 1:600 mg/μg, Table 1).

Mycotoxin2

1CA: Activated carbon; HSCAS = Hydrated sodium and calcium aluminosilicates; MMT = Montmorillonite; YEAST = Yeast cell wall.

2AFB1 = Aflatoxin B1; DON = Deoxynivalenol; FUM = Fumonisin; OTA = Ochratoxin A; T-2 = T-2 toxin; ZEN = Zearalenone.

It will be relevant to establish a standardized adsorbent:mycotoxin ratio to be used in in vitro tests in order to make fair comparisons.

The EFSA (2017) considers adsorbents to be safe and establishes high safety limits (20 kg/t of feed).

The currently recommended doses of adsorbents are generally established by the marketing companies of the adsorbents, which conduct in vitro tests using different inclusion doses of adsorbents.

This required dose differs depending on the type of adsorbent, as the chemical properties vary with the chemical composition and nature of the adsorbent. However, it should be possible to recommend a range of proportions to be followed during in vitro experiments.

Díaz et al. (2004) recommended a concentration of 1.2% of dry matter daily, equivalent to 300 g/day/cow, of adsorbent. However, the daily intake of mycotoxins is highly variable and depends on the type of mycotoxin.

Therefore, it is reasonable to propose an appropriate dosage related to the minimum toxic levels of each mycotoxin evaluated by the European Commission (EC, 2006, regarding raw materials).

To standardize an in vitro protocol, we propose using an adsorbent:mycotoxin ratio close to that found under field conditions.

To achieve this, the daily intake of adsorbents and mycotoxins must be determined.

The practical dosage of adsorbents should be considered based on what has proven effective for mycotoxin adsorption.

Since mycotoxicosis occurs in animals with high concentrations of mycotoxins, we propose using the minimum toxic concentration for each mycotoxin multiplied by 10 for in vitro tests.

Therefore, the daily intake will be 10 times higher than the minimum toxic limits, considering an average consumption for each animal species.

10 X MINIMUM TOXIC CONCENTRATION OF THE

This adsorbent-to-mycotoxin ratio (mg/μg) should allow evaluating the adsorbents' capacity to adsorb toxic levels of mycotoxins in an appropriate proportion.

A standardized procedure should also consider other aspects such as the characteristics and volume of the incubation media, duration, and pH, among others.

Finally, like any in vitro test, validation would be necessary.

However, it is very challenging to conduct in vivo tests to provide sufficient data for each adsorbent and each mycotoxin for the validation process, which increases the difficulty of developing a reliable and validated test.

The actual in vitro protocols used to evaluate adsorbents are designed as a detection method, primarily employed during product development because they provide quick and cost-effective information about the efficacy of the products.

However, this information is limited due to the high variability among methods and laboratories.

The current challenge is to develop a validated method that provides reliable results for different adsorbents and mycotoxins.

A validated method can also be used as a refinement procedure to replace in vivo studies, which are costly and complicated to apply.

Due to the variability in results and the limited available data, it is important to:

1. Standardize an in vitro method to evaluate the capacity of adsorbents to adsorb mycotoxins and other nutrients in vitro.

2. Validate the results with in vivo tests.

*References available upon request Original article from mycotoxinsite.com New approaches

Diet formulation is a critical part of a profitable pig production. It is generally accepted that feed represents between 60-70% of the production costs and impacts many facets of the business, including:

Purchasing ingredients

Quality control

Feed mill processes

Scheduling

Transportation and logistics

On-farm feed delivery

Equipment purchases

Business planning

Feed is the most important input for the production system and is a key driver of pig performance

That’s the reason why establishing nutrient specifications correctly for each production phase to achieve animal performance goals is a crucial step, accomplished through diet formulation

Changes in raw material prices

Availability of raw materials: for example, if there was a poor yield in the harvest of a certain ingredient like soybean hulls, it means the producer should plan to decrease the volume of this ingredient in the diets.

Once nutritional requirements are defined and diets are formulated, the tempting thought of “they’re done, and we can forget” may arise.

However, it is crucial to understand that the nutrient content and the price of ingredients are not static but are constantly changing.

Knowing this, we need to ask ourselves: Do I need to reformulate my diets?

There are many reasons to consider reformulating or updating diets. Some of these include:

Nutrient content:

this can be determined by conducting quality control analyses such as percentages of crude protein, fats, moisture percentage, among others.

Moreover, fluctuations in pork prices in the market affect profitability, and therefore, diet reformulation is required to adjust production costs and to maintain a sound margin.

An example of this is when pork prices are low, the profit margin is lower, so the inclusion of alternative ingredients, such as soybean oil, white fats (white grease), and some additives that help improve weight gain and feed conversion, may be affected.

There is yet another important question we must ask ourselves:

The process of changing diets takes time and will impact ingredient purchasing demands, so it is essential to establish a minimum threshold for diet cost reduction to avoid making changes too frequently.

Some systems update ingredient prices and raw material quality information, i.e., nutrient content, weekly, while others prefer to do it monthly.

Others, however, adopt an opportunistic approach and only change as needed or when significant changes occur in ingredient prices or quality. The latter approach is not technically correct; a more methodical approach adhering to a regular schedule probably captures the most savings.

Here are two examples to illustrate the potential cost savings that can be achieved when the price of an ingredient changes or when the nutrient content of a key ingredient changes. In both examples, the following base ingredient prices were used (in USD/ton):

Corn: $230

Soybean meal: $493

DDGS (Dried Distillers Grains with Solubles): $254

Wheat middlings: $249

Table 1 shows a comparison of diet costs when the price of DDGS increased from $254/ton to $325/ton.

The current diet cost increases significantly (around $6-8/ton) as the price of DDGS rises.

If diets were reformulated using the higher price of DDGS, some savings could be captured (approximately $0.18/pig).

Although this may seem like a small change, every penny counts. If you have an inventory of 100,000 pigs, the savings would amount to $18,000 due to the reformulation.

In this example, we used a soybean meal protein value of 45% for current diet costs.

If the protein in soybean meal changes, but we are not measuring it, the diets will remain unchanged.

However, even with a rudimentary quality control program to routinely measure nutrient levels in key ingredients, we have the opportunity to generate savings in the nutrient content of soybean meal and reformulate diets, saving several dollars per ton.

The total savings per pig is more than $1.13 or over $113,000 for 100,000 pigs. If this nutrient change were to occur in the opposite direction (i.e., 47% soybean meal protein, reduced to 45%) and we did not detect it, the diets would no longer meet the target nutrient levels for which they were originally formulated.

This would result in lower pig performance and, consequently, a longer time to reach market weight.

Additionally, more feed would be used due to poorer feed conversion, leading to lost income from lower daily gain and final weight.

These examples demonstrate the need to routinely monitor the nutrients in ingredients and reformulate diets to capture savings or meet nutrient requirements effectively and cost-efficiently A robust quality control program where nutrient levels of key ingredients (or those with the highest and most common inclusion in diets such as corn, soy, wheat, DDGS) are routinely measured along with periodic price updates is a critical first step in uncovering cost-saving opportunities.

This information can be used to update feed formulations at least once a month to ensure cost savings are captured.

Why should you keep your farm’s nutritional formulas up to date?

DOWNLOAD IN PDF

Resilience is a key characteristic for pigs to reach their production potential under commercial conditions. Advanced nutritional strategies could play a role in supporting resilience in pigs and new technologies are paving the way to better monitor improvements in resilience.

In the future this could help to demonstrate how optimizing nutrition for resilience can have further benefits for pig welfare and farm economics.

Studies have shown that pigs within a commercial grow-finish environment only achieve 70% of their growth potential compared to pigs reared in a less challenging research environment.

Resilience in livestock refers to the ability of animals to be minimally affected by stressors and quickly return to their optimal production level.

However, there are indications that this 30% gap in performance can be closed by increasing the capacity of pigs to cope and recover quickly from stressors.

Several disciplines in pig production, including genetics, veterinary sciences and nutrition are striving to find ways to positively influence resilience in pigs.

There are two reasons for that: In other words, breeding and managing for resilience in pigs could increase the potential for greater performance under commercial conditions than what is currently achieved. Furthermore, the potential benefits for animal welfare and farm economics are not to be neglected.

The capacity of the animal to be minimally affected by disturbances or to rapidly return to the state pertained before exposure to a disturbance (Berghof et al 2019)

On the one hand, developments such as the need to reduce the use of antibiotics, climate change, animal welfare concerns and a shortage in farm labour are increasing the need for resilient farm animals 1 2

On the other hand, continuous breeding for improved animal performance has been shown to reduce the resilience of farm animals

Short-term challenges to the pig can reduce its welfare. Therefore, managing and breeding the pig for improved adaptability and for resilience will contribute to higher welfare outcomes.

However, as Grosse and Mueller (2018) and others warn, it should not be seen as a substitute for good housing and good management practices in farm animal production systems.

Researchers suggest that the economic value of resilience can be based on labour costs associated with observing animals that show signs of disease or other problems.

A reduction in time spent on an animal with an alert will reduce costs associated with labour.

These could be visual signs or alerts generated by sensors or automatic feeding systems. Labour time is limited. As a result, farmers have a requirement for healthy and easyto-manage animals, especially when the number of animals per farm employee is increasing.

Quite often the first noticeable change in response to stressors is a reduction in feed intake.

However, there are also other reactions at a cellular and gut level of the pig, such as oxidative stress and inflammation that further reduce the energy available for growth and production as they increase the requirements for maintenance energy.

Ultimately, the pig´s capacity to adapt efficiently will determine the extent of those stress reactions, the recovery of the pig and the impact they have on productivity over time.

Considering that bioactive substances from herbs and spices have been proven to reduce oxidative stress and inflammatory responses at different production stages in pigs, they could also have the potential to support the adaptive capacity and resilience in pigs.

Many herbs and spices contain high levels of components with strong anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory power and new research methodologies are increasing the understanding of how those components can work alone and in concert at the cellular level in pigs.

However, further research trials are required to establish whether those type of components impact recognized production measurements for resilience in pigs on farms and can thus help to optimize diets for increased resilience in pigs.

Resilience affects the pigs’s response to changes in its production status (e.g. start of lactation or weaning) as well as challenges in its environment and diet. However, our ability to influence and improve resilience in pigs depends on knowing how to measure it in the field.

Measurements at a single time-point in response to a stressor tell us little about an animal’s resilience to a given stressor since by its definition resilience involves dynamic patterns of response and recovery. Therefore, repeated measurements over time are key to determine resilience in farm animals.

Several research groups have taken different approaches to measuring resilience in pigs.

For example, some are using behavioural data and others are using production data.

New technologies, such as automated feeding systems, sensors and computer vision are greatly facilitating the ability of producers to collect data from repeated individual measurements in pigs on farm.

This paves the way for successfully monitoring improvements in resilience in pigs under practical conditions.

What they all have in common is, that they are recording repeated observations to detect the number of fluctuations or deviations from an expected standard over time.

Genetic researchers in the US confirmed that fluctuations in feed intake or the duration at the feeder over time are indicators for resilience in growfinishing pigs and can be used as a heritable measure of general resilience in pigs.

In those trials the collection of the data on weight, feed intake and feeding behaviour in pigs was facilitated by automated feeding stations.

With an increasing number of pig farms investing into automatic feeding systems it could also be feasible to measure resilience under practical commercial conditions on pig farms.

Research so far has been applying new parameters and protocols to measure resilience for genetic selection programs.

Further research is required to evaluate promising nutritional strategies for their capability to enhance resilience in pigs effectively under commercial conditions using the recently established parameters and protocols.

This could potentially contribute to advancing diets from a cost-efficient perspective and further increase the potential to boost pig welfare, if pig diets can be optimized successfully to enhance resilience.

Optimizing pig nutrition for enhanced resilience DOWNLOAD ON PDF

Most recommendations for vitamins in swine nutrition are still based on studies conducted several decades ago.

there is a concern about whether current levels are adequate for modern pig genetics.

However, this topic raises some controversy because, in some cases, the information , and commercial may sometimes make the need to update recommendations less credible.

Nevertheless, several reasons suggest the need to review recommendations for vitamins and other nutrients for . The tendencies of vitamin use in the swine industry indicated that these levels are, in fact, adjusted across time.

In pigs, changes caused by genetic improvement geared to reducing the feed conversion ratio which have had the marked indirect effect of reducing voluntary ingestion over the last few decades (Culbertson et al., 2017; Soleimani and Gilbert, 2020).

Most vitamin recommendations for swine derived from different experiments are expressed in concentration per kilogram of feed.

These changes do not affect pigs with the same intensity during all productive phases, nor is the effect on both sexes the same. Weaning and the post-farrowing period or early lactation are critical in pigs.

There has been a marked increase in the productive capacity of the animals, ever approaching the physiological limit. As productivity increases, more attention should be paid to the supply of the different nutrients to avoid imbalances.

However, genetics continue to evolve (Culbertson et al., 2017; Lozada-Soto et al., 2022). We are on the threshold of a revolution thanks to the massive application of techniques based on molecular biology.

It will, therefore, be necessary to take the conditions for the optimization of feed formulation to the limit to maintain that rate of improvement in production.

With more scientific knowledge related to physiological and metabolic processes that affect pig production, health, welfare, and behavior, nutritional studies must consider other factors besides those strictly related to nutrient deficiencies or only productive response optimization.

These aspects include immune response capacity, breeder longevity, the viability of neonatal pigs, adaptation to environmental, dietary, and immunological stress, response to vaccinations, susceptibility to pathological problems, and the capacity to overcome disease or resilience.

Nowadays, the variability among pig individuals in a herd and not only the average values in any production parameter deserve ever-increasing attention in modern swine production for precision livestock nutrition.

The effects of vitamin levels on achieving precision nutrition have yet to be evaluated in sufficient depth.

Different response curves for the same vitamin can be expected according to the measured parameters: growth, resistance to disease, meat quality, reproductive ability, immune response, etc. (Lauridsen et al., 2021a, b; Lauridsen, 2022).

In the last few years, pork consumers have played a more active role in production and are becoming far more selective in their choices. For this reason, attention must be paid to their opinions and specific demands.

Thus, aspects like diversification of production, animal well-being, the content of potentially toxic compounds or residues, fortification of food with natural compounds, etc., acquire particular relevance.

Optimum vitamin nutrition in swine offers attractive alternatives that must be studied and applied appropriately.

During the past few years, conditions in production have been modernized significantly, with improved genetics, facilities, feed manufacturing and delivery, electronic sensors, etc. The technical revolution’s consequences call for optimizing nutrition and considering all the impacts of vitamins.

The costs of feed ingredients, including vitamins, used in pig diets are variable and, on many occasions, volatile.

Therefore, the vitamin levels should also help obtain optimum economic returns in each case. In general, technical processes and large-scale industrial production mean that the production of synthetic vitamins is more efficient.

So, the price of the vitamin supply is becoming proportionally lower than the other ingredients used in feed formulation.

Therefore, the dietary vitamin concentration that should match the economic optimum tends to become higher, ever approaching the recommended concentration for optimum production, health, welfare, and pork quality.

This fact demands special attention since only some commercial vitamin preparations or sources are of the same quality, and they are equally beneficial to the animals.

Some changes to feed guidelines, e.g., a ban on meals of animal origin, a ban on antibiotics, and other changes, are in place in several countries or will undoubtedly occur soon in many others, meaning that the entire production strategy should be reviewed.

This includes rethinking housing, vaccination plans, handling, etc., and entailing re-evaluation in economic terms of the supply of different micronutrients in different phases of the productive cycle.

Considering all these factors, this Optimum Vitamin Nutrition book looks at the study of vitamin requirements in swine nutrition in light of the latest discoveries for health and welfare.

Intensified production increases stress and subclinical disease-level conditions because of higher densities of animals in confined areas. Animal stress and disease conditions may increase the essential requirement for specific vitamins.

Several studies indicated that nutrient levels adequate for growth, feed efficiency, gestation, and lactation might not be sufficient for normal immunity and maximizing the animal’s resistance to disease.

The adverse effect of environmental stress on a pig’s health, welfare, and performance cannot be overemphasized.

Environmental stressors can cause an upsurge in stress hormone secretion, negatively affecting growth and leading to severe mortality.

However, effective management techniques are crucial to raising healthy pigs and maximizing profits in the swine industry.

To enhance pigs’ adaptability under stress conditions, it is essential to understand the functions of different vitamins and the appropriate dosage in pig diets to alleviate stress.

Diseases or parasites affecting the gastrointestinal tract will reduce the intestinal absorption of vitamins from dietary sources and those synthesized by microorganisms.

If they cause diarrhea or vomiting, they decrease intestinal absorption and increase vitamin needs. Vitamin A deficiency is often seen in heavily parasitized animals that supposedly receive adequate vitamins (Bebravicius et al., 1987).

The synergistic effects of various vitamins and minerals could promote growth performance and reduce environmental stress in pigs (Liu et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2017).

Any disease that includes bleeding of the intestinal wall increases both vitamin loss and vitamin requirements for tissue regeneration. Likewise, a condition that causes a loss in appetite and feed intake increases the need for vitamins per unit of feed consumed to meet daily body needs.

Diseases that adversely affect the integrity of the intestinal wall may interfere with vitamin A conversion from carotene and increase the animal’s vitamin A needs.

The transformation of vitamin D to its functional forms in the liver and kidney would be affected by diseases of these organs (Arnold et al., 2015).

Mycotoxins are known to cause digestive disturbance, such as vomiting, diarrhea, and internal bleeding, and interfere with the absorption of dietary vitamins A, D, E, and K (Surai and Dvorska, 2005).

Mouldy corn containing mycotoxins have been associated with deficiencies of vitamin D (rickets) and vitamin E, even though these vitamins were supplemented at levels regarded as satisfactory (Van Heugten, 2000).

Vitamin C has been found to promote vitamin D metabolism and is also known to counter the effects of multiple stresses (Cantatore et al., 1991; DeLuca, 2014).

Heat stress depresses feed intake, immunity, sow livability, and reproductive performance in pigs (Horký et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2021).

Ascorbic acid supplementation has improved these traits (Sosnowska et al., 2011)

Ascorbic acid (250 mg/kg) can also alleviate nutritional stress.

Adenkola et al. (2009) showed that ascorbic acid modulates the body temperature of pigs by decreasing the maximum rectal temperature value and may alleviate the adverse effects of the thermal or transportation stress on the health and productivity of pigs during the cold-dry season or hot, dry season (Asala et al., 2010).

Although vitamin C is commonly associated with alleviating the effects of heat stress in pigs (Feng et al., 2021), there is evidence that combination with vitamin E can also play a vital role in minimizing the adverse effects of stress in growth, sow, and boar reproductive ability (Sahin et al., 2001; Horký et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016).

Selenium supplementation can also be combined with these antioxidant vitamins to improve their efficacy in coping with stress (Oldfield, 2003)

The apparent, direct effect of vitamins on gut microbiome had not received much attention until recent years in literature related to health and welfare.

In the past few years, several research reports have confirmed that almost all vitamins may directly improve the gut health of pigs during stressful periods like weaning.

Positive results have been observed when supplementing piglet or sow diets with β-carotenes (Li et al., 2021), lycopene (Meng et al., 2022), vitamin D (Zhang et al., 2020; 2021; Zhao et al., 2022), ascorbic acid (Trawińska et al., 2012), niacin (Liu et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2021), folic acid (Wang et al., 2021b), and choline (Qiu et al., 2021; Zhong et al., 2022).

All these vitamins can improve intestinal immunity, enhance gut antioxidant status (Xu et al., 2014), modulate gut microbial communities, and stimulate mucosa development and intestinal barrier functions in weaned piglets or sows, enhancing their health and welfare.

Vitamins for Swine Health, Welfare, and Productivity

This large body of scientific evidence supports the statement that vitamins are essential for health (Lauridsen et al., 2021a; Matte and Lauridse n, 2022).

Vitamins can enhance animal host and gut microbiota metabolism to obtain favorable outcomes for the health and growth of pigs (Stacchiotti et al., 2021).

In pigs, weaning could be the most critical period in life and where most of the genetic growth potential is at risk. Vitamins can support a more manageable transition during weaning.

The previous effects and many others are described with more details and data in this book that we recommend to our readers at NutriNews International.

References are available upon request

Dr. med. vet.

VolkerWilke Institute of Animal Nutrition, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation.

SUSTAINABLE PERFORMANCE WITH HYBRID RYE?

Opportunities for the use of rye in pig diets: What do recent studies tell us and how far can we go?

WHY

Rye was for many years a traditional cereal in the feeding of pigs in northern Europe. However, higher yields of wheat and corn have displaced it as a common ingredient in pig diets. But why is rye experiencing a renaissance now?

The search for sustainable and efficient livestock production has led to exploring alternative ingredients for feed that provide essential nutrients while minimizing environmental impact.

In recent years, rye has gained attention as a potential feed ingredient for fattening pigs due to its nutritional profile, environmental benefits, and profitability.

Today, the choice among different cereal varieties in pig feeding is not limited to maximizing energy and protein yield per hectare but rather finding the solution that best fits current conditions.

These are characterized by climate change (crops more tolerant to heat and drought), environmental impact (expenditure on fertilizers and pesticides), and advancements in genetic improvement (yield of new varieties).

As global attention intensifies on sustainable agriculture, hybrid rye offers several environmental advantages when used in pig feeding. It is a resilient crop that requires fewer chemical inputs, such as fertilizers and pesticides, compared to other cereals.

Its ability to grow in cold climates and poor soils makes it a valuable crop in rotation systems, as it promotes soil health and reduces the risk of erosion.

Additionally, rye can be an essential component of cover crop strategies, mitigating nutrient runoff and improving the overall sustainability of farms.

As a result, its growth has a relatively low carbon footprint (GFLI 2023). This factor could play a much more significant role and offer opportunities in the future regarding pig feeding.

Especially when it comes to foods with a “CO₂ footprint,” this may even offer market advantages.

In the context of climate change and the environmental impact of cereal cultivation, there are many arguments (efficiency in the use of limited resources such as water and phosphorus) in favor of rye. Wheat

432

In general, wheat and rye are characterized by different amounts of starch and crude fiber. The crude protein content of wheat is up to 35% higher than that of rye. However, it is worth noting that rye has the richest lysine amino acid profile. In diets for fattening pigs, this can offer the advantage that lower protein contents can be achieved without expecting a loss of performance due to the supplementation of individual amino acids.

Furthermore, rye is an excellent source of fiber, especially soluble fiber, which can positively influence the intestinal health of pigs.

Due to increased fermentation, higher concentrations of lactic acid and short-chain fatty acids in digestion could also have positive effects on animal health.

Although there are many characteristics that advocate for increased use of rye in swine feed, there are several parameters that are most interesting.

On one hand, there should be a high level of feed intake acceptance.

This should result in favorable daily gains and, therefore, preferably low feed conversion ratios.

Let’s look at some recent studies on the use of rye in fattening pigs.

The question might be, when to start with rye in younger animals. There is good news: rye can already be used in the feeding of weaned piglets. Early adaptation can bring advantages when using a rye-based diet in subsequent fattening periods.

Certainly, only small amounts should be used in the diets of these very young animals. However, a recent German study has also shown that even with a 48% switch from wheat to rye, no negative effects were found (ELLNER et al. 2021).

Additionally, a study from Illinois (MCGHEE et al. 2023) has demonstrated that up to 60% of corn can also be replaced by rye in the first 5 weeks post-weaning. Apart from a slight increase in feed conversion, no negative effects were found regarding gains and feed intake.

33-day trial (ELLNER et al. 2021)

In our own studies conducted at the Institute of Animal Nutrition, young fattening pigs (16-40 kg) were fed diets containing increasing proportions of rye (WILKE and KAMPHUES 2023).

Graph 1.

Graph 1.

As can be seen from these data, feed intake and weight gain were not affected by higher levels of hybrid rye in young animals.

However, with 46% rye in the diet, the feed conversion ratio increased in these young animals.

In Poland, there are also increasing studies on the use of rye in pig feeding. In a recently published study, not only the performance of the animals was analyzed but also the potential effects on carcass condition (LISIAK et al. 2023).

Animals from 29 kg to about 110 kg were fattened. Diets containing 20%, 40%, and 60% of rye were compared with a standard diet based on barley and wheat. Soybean meal was used as a protein source.

Table 2. Average daily feed intake (ADF), average daily weight gain (ADWG), and feed conversion ratio (FCR) in young fattening pigs (16 - 40 kg) fed rye-based diets (WILKE and KAMPHUES 2023).

Table 2. Average daily feed intake (ADF), average daily weight gain (ADWG), and feed conversion ratio (FCR) in young fattening pigs (16 - 40 kg) fed rye-based diets (WILKE and KAMPHUES 2023).

Regarding the performance of the animals, no negative effects were observed when increasing the amount of rye in the diets. The results also did not show any losses in carcass quality due to the forced use of rye.

The backfat thickness, lean meat content of the carcass, and that of the main cuts were not affected in the group fed hybrid rye-based diets compared to the control group fed barley and wheat.

There were also no observed changes in animals fed rye regarding most of the physical characteristics of the meat, not even in the basic chemical composition, cholesterol content, or sensory characteristics.

On the contrary, more favorable values for n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) were found, and therefore the ratio of n-6 to n-3 PUFA was better (LISIAK et al. 2023).

As can be seen, the use of rye offers advantages in pig feeding. In very young pigs, rather moderate amounts should be used, as otherwise an increase in the amount of feed required may occur. In the growing and finishing phase, however, significantly larger quantities can be used to achieve favorable gains.

Recommendations for the use of hybrid rye in fattening pig diets based on our own studies:

Table 3. Feed intake (kg, entire fattening period), average daily weight gain, and feed conversion ratio (FCR, kg/kg) in fattening pigs (29 - 110 kg) fed rye-based diets (LISIAK et al. 2023).

The International Poultry Scientific Forum is an annual gathering with worldwide impact where multiple research reports are presented. This year, 1,523 registered participants had the opportunity to receive original information in 210 oral presentations and 169 posters.

These presentations included diverse topics of poultry production, but almost half were related to nutrition.

Due to the limited space of this publication, only a few papers were selected to be highlighted within four key topics:

minerals, enzymes, evaluation of soybean meal quality, and feed formulation.

The objective is to use these research results to comment on some advances in understanding crucial aspects of practical poultry nutrition.

Calcium (Ca) is usually the cheapest nutrient in poultry diets. However, it significantly impacts nutrient utilization, gut health, bone mineralization, meat quality, and performance.

Calcium dietary concentration, particle size, and solubility are the main factors to observe in feed formulation and source selection.

A research project presented by Joseph Gulizia from Auburn University evaluated particle sizes (200 and 910 µm) together with three levels of Ca concentration under a necrotic enteritis challenge.

Three Ca levels (Adequate, Reduced, and Low) were created by a two-step 10-point reduction from the quoted Adequate Ca concentration for each phase (Starter: 0.95%; Grower: 0.85%; and Finisher: 0.75%).

The necrotic enteritis reduced body weight gain and increased feed conversion ratio but did not cause mortality.

The limestone particle size did not affect tibia mineralization.

The Ca level affected growth and FCR.

Better results were observed in chickens fed with adequate and reduced Ca levels than in Low.

The larger particle size (910 µm) improved the feed conversion ratio in the Caadequate group. However, the same parameter was increased when chickens were fed the Low-Ca diets.

The Low Ca-diets also had detrimental effects on tibia weight and strength.

Consequently, this study demonstrated that diets with adequate Ca or reduced 0.10% in each phase could support adequate performance under necrotic enteritis.

The same research group (Tabish et al.) also reported that Ca levels and particle size also affect the diversity of the intestinal microbiome in broilers after a subclinical necrotic enteritis challenge. Those gut microbial changes could partially explain some effects of high Ca levels previously reported on intestinal health.

There is an increased interest in using digestible Ca and P values in feed formulation to account for the significant variability of these minerals in the diverse sources available. However, the multiple factors that can affect digestibility values in sources of these minerals have limited the adoption of these values.

One partial solution can be the determination of standardized ileal digestibility (SID) values. These means to determine the basal endogenous losses (BEL) of these minerals to make a standardization. Lee et al. from Kyungpook National University in South Korea presented a project evaluating Ca and phosphorus’s SID.

A Ca-P-free diet was formulated to estimate the BEL of Ca and P. Three other semi-purified diets were prepared, each containing monocalcium phosphate (MCP), dicalcium phosphate (DCP), or monosodium phosphate (MSP), with limestone as the sole source of Ca, P, or both Ca and P.

These diets provided 4.21 g/kg of non-phytate P from MCP, DCP, or MSP, and the MSP with limestone diet included 7.5 g/kg of Ca. All diets included 5 g/kg of chromic oxide as an indigestible marker.

The BEL values for Ca and P were determined to be 58.98 and 66.37 mg/kg of dry matter intake, respectively.

The SIDs of MCP, DCP, and limestone were found to be 84.8%, 70.1%, and 52.6% for Ca, respectively.

Meanwhile, the SIDs of MCP, DCP, and MSP were 91.7%, 76.8%, and 94.4% for P, respectively.

Due to the variation in Ca digestibility observed, it is essential to start considering the application of these values in feed formulation. However, specific requirement values of digestible Ca and P for each phase are needed.

An interesting common belief shared by many nutritionists was addressed in the research conducted by Bowen et al. from West Virginia University.

Some nutritionists tend to accept that when birds access litter, they consume phosphorus; consequently, people may think that lower phytase concentrations could be required.

This idea is based on the observation that most phytase research has been conducted raising broilers in wire cages, but commercially built-up litter is more commonly used.

This study evaluated this issue by feeding chickens raised in wire cages or floor pens.

The diets evaluated included a nutritionally adequate positive control (PC; 0.90% calcium and 0.45% nonphytate phosphorus [nPP]) and a negative control (NC; 0.65% calcium and 0.20% nPP) pelleted diet.

Phytase was added to the NC diet at 250, 500, 1,000, 1,500, 2,000, and 2,500 FTU/kg.

Growth performance and tibia ash data were analyzed in a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a factorial arrangement of treatments.

In both housing systems, at least 1,500 FTU/kg were necessary to have body weight and tibia ash similar to the observed in chickens fed the PC diet at 21 days of age.

The values observed at this level of phytase were significantly higher than the body weight and bone ash values obtained with chickens fed the NC diet.

Consequently, the potential litter consumption does not significantly influence broiler performance or bone ash.

Dr. Nelson Ruiz is a professional who has contributed for several years to methods of evaluating soybean meal quality, the most common protein source for poultry.

This year, he presented another elegant paper describing a research project that determined that KOH protein solubility (protein that is solubilized in a potassium hydroxide solution) and trypsin inhibitor analyses are needed to determine soybean meal quality.

The search for the best methods to evaluate the processing and nutrient quality of soybean meal extracted by solvent is a concern worldwide for the feed industry.

Multiple analytical techniques have been developed for this purpose. Some of these methods are the urease index, KOH protein solubility (KOHPS), protein dispersibility index (PDI), trypsin inhibitor activity (TIA), reactive lysine, and the ratio of reactive lysine to total lysine.

However, each parameter provides only partial information of quality.

This particular project evaluated the relationship between KOHPS and TIA. The former measures overprocessing, and the latter is a parameter for both over and underprocessing.

The TIA has two analysis methods, and results can be expressed as

trypsin units inhibited (TUI) per mg of sample or

trypsin inhibited (TId) per g of sample.

The group led by Dr. Ruiz concluded that soybean meal that is adequately processed, especially not overprocessed, exhibited 80 to 85% KOHPS, which correlated with 0.88 digestible lysine coefficient or greater but could have variable TIA.

Some of these samples contained 3.5 to 5.33 TUI/mg (2.5 to 3.0 mg TId/g), and the field assessment in commercial broiler flocks indicated satisfactory performance.

However, some of these samples contained 6.4 to 12.82 TUI/mg (3.4 to 4.99 mg TId/g), which correlated with the observation in the field of rapid feed passage and poor zootechnical performance in broilers in diverse countries.

There was a high relationship (R2 = 0.956) between KOHPS and digestible lysine when TIA was below 5 TUI/mg (below 3.0 mg TId/g), indicating no interference in the relationship between KOHPS vs. digestible lysine due to TIA.

Nevertheless, when TIA was above 5 TUI/mg, this relationship was not significant, indicating that TIA must be addressed in feed formulation before defining the correct digestible lysine spec for soybean meal. These results indicated that the two parameters, KOHPS and TIA, are necessary.

Additionally, this group observed a positive relationship (R2 = 0.79; P < 0.05) between the AOCS enzymatic 2020 method (TUI/mg) and the EVONIK NIRS (TId/g) method (AminoNIR®).

The NIRS technology can facilitate a complete evaluation of soybean quality.

Feed formulation has been done with least-cost linear programming methods for many years. Nevertheless, many alternatives are available to optimize formulation by objectives, for maximum profit, to minimize nutrient excretion, to account for non-linear responses to levels of nutrients or enzyme activity, and

to deal with nutrient variability.

The formula provides a 50% probability of meeting the minimum nutrient specifications in linear programming. This is because linear programming assumes the nutrient profile is fixed, only uses average values, and ignores nutrient variability, which is assumed to have a normal distribution and a centered mean.

Commercial nutritionists use margins of safety either on nutrient constraints or nutrient means to deal with the uncertainty of meeting the nutrient specifications.

This adjustment can be applied on a per-nutrient basis as a percentage or some portion of nutrient standard deviation, generally only half. Since the nutrient values after adjustment remain fixed, the margin of safety is a linearized approximation used to fit into linear programming. Alternatively, nutritionists may use stochastic programming for feed formulation, allowing non-linear constraints. This method has been shown to account for nutrient variation and provides nutrients at specified confidence levels.

Several researchers and some feed formulation companies explored stochastic formulation in the 1990s and early 2000s. However, nutritionists never embraced this development. Probably, one significant limitation at that time was to have enough data on the complete nutrient composition of feedstuffs to apply it.

In the past decade, the number of analytical labs has increased, and NIRS has become a standard tool with more reliability than in its early stages 20 years ago.

Consequently, the amount of nutrient composition data has increased rapidly, and the feed industry is conscious of the variability in the diverse sources of primary feedstuffs like corn and soybean meal.

Caleb Marshall from North Carolina State University presented an exercise to evaluate the financial impact of using the nutrient variability information of soybean meals that vary by country of origin in the stochastic programming of broiler diets. This exercise was conducted with a spreadsheet developed in Excel.

Data from the Adisseo Precision Nutrition Evaluation System was used to characterize soybean meals from Argentina, Brazil, and the United States in two years that have considerable nutrient and energy content variability. Notably, increased soybean meal variability resulted in higher utilization of SBM, DDGS, and poultry fat to meet the minimum nutrient requirements.

Overall, stochastic programming achieved cheaper diet cost at a higher confidence in meeting nutrient specifications compared with a margin of safety at either 5% or using half of a standard deviation. Feed prices in stochastic programming can be reduced between $2.65 and $3.61 per ton compared to a margin of safety with half standard deviation.

The annual cost savings using stochastic programming could be between $896,372 and $658,000 for a company producing one million broilers per week. These calculations were made using parameters determined by AgriStats (The US Benchmarking Company), indicating that a $1/MT change in feed cost equals $282,077 per year in a broiler company of that size.

The main limitation to implementing stochastic feed formulation is the lack of commercial software with solvers able to do non-linear programming functions.

These and other topics will be expanded in the following issues of NutriNews International.

Miguel Alberto Pérez Espinoza, Benjamín Fuente Martínez, and Ezequiel Rosales Martínez

CEIEPAv-FMVZ-UNAM and Center for Applied Research in Poultry Nutrition S.A de C.V., Mexico

World population will exceed 9 billion people in the next 4 decades (Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO], 2014) with a concomitant 60% increase in food demand (Kebreab, 2016).

Poultry farming is important in generating high-quality, low-cost food for humans, and particularly, chicken eggs play a significant role; hence, numerous studies are aimed at determining the mineral requirements, especially calcium and phosphorus, in laying hens (Sanmiguel, 2016).

Phosphorus is the third most expensive component in a ration (Vallardi, 2002) and has environmental importance due to its excretion by birds. (Keshavarz, 2004).

Valdés 2011 in his work mentions that genetic selection has changed the characteristics of laying hens, which are more productive, with lower maintenance requirements, but also with low feed intake, so they consider that the calcium and phosphorus requirements need to be constantly reevaluated.

It is also worth noting that in Mexico and other egg producing countries, we still use available and non-digestible phosphorus values, this is due to various factors, the first being that recommendations in the literature still use available phosphorus from NRC Tables and second, we do not have information on the digestible phosphorus values in the ingredients we are using,

however, the concept of digestible phosphorus is beginning to appear in literature such as the Brazilian tables (Rostagno 2017), in the Hy-Line W80 2017 manual, and the nutritional needs in poultry farming FEDNA (Spanish Foundation for the Development of Animal Nutrition) Standards (2018)

The available phosphorus requirements for laying hens have been evaluated; however, studies to work with digestible phosphorus are scarce.

Pre-cecal digestibility (PC) is an established criterion for measuring the quality of certain nutrients in birds. Therefore, this criterion begins to take relevance since the values are not affected by post-ileal microbial activity, in addition to eliminating the effect of contamination by urinary excretion.

This is an advantage since urinary excretion is one of the most important regulators in P metabolism.

This criterion can be developed as an alternative tool for measuring P availability, as one of its advantages is its lower sensitivity to variation in dietary P, compared to other approaches.

To implement adequate Ca and P rations, it is necessary to know the digestibility of these minerals from the ingredients we use and that the bird requirements are expressed in the same terms. (Gómez 2013).

Avoiding deficiencies is the main objective of optimizing the P concentration in feed, but other aspects are becoming increasingly relevant.

On one hand, P accumulates in the soil and leaches if that concentration becomes too high, with negative consequences on surface waters, such as eutrophication

On the other hand, it is necessary to consider that global gross phosphate resources, which are essential for the production of feed P, are limited. (Rodehutscord, 2011).

Most phosphates are derived from phosphate rock, which is a nonrenewable resource, and current reserves could become scarce in 50 - 100 years. Maintaining P resources in the face of scarcity has been identified as one of the greatest challenges of sustainable food production. (Gómez 2013).

Given this background, the objective of this study was to evaluate the productive response of Hy-Line W 80 laying hens fed with different levels of digestible phosphorus and fixed levels of total calcium.

The study was conducted at the Center for Applied Research in Poultry Nutrition (CIANA), which is a commercial-type experimental farm, located in the state of Jalisco, Mexico.

800 Hy-Line W-80 hens at 36 weeks of age, with an average weight of 1,582 ± 85.7 g, were housed in California-style cages in a pyramidal form of 3 levels, with each cage capable of accommodating 5 birds, providing a space of 400cm2/bird, with a trough feeder (10 cm/bird) and nipple drinker.

The hens were distributed in a completely randomized design into 5 treatments with 8 replicates of 20 hens each.

All animals were provided with water and feed ad libitum.

Phase 1 diets (from 38 to 50 weeks of age) were formulated based on white maize, soybean meal, and canola meal according to the nutritional profiles calculated based on egg mass production and a feed intake of 108 g/bird/day.

The treatments were:

Diet with 0.254% digestible phosphorus (DP) and 4.1% total calcium (TC)

Diet with 0.292% DP and 4.1% TC

Diet with 0.328% DP and 4.1% TC

Diet with 0.365% DP and 4.1% TC

Diet with 0.402% DP and 4.1% TC

1 2 3 4 5

During the 12-week experimentation period, weekly productive parameters were recorded, and the following variables were determined:

Laying percentage,

Average egg weight (g),

Feed intake per bird per day (g),

Percentage of broken eggs, Dirty eggs,

Number and kg of eggs accumulated per housed hen, Egg mass per bird per day (g),

Weekly and cumulative feed conversion ratio (kg:kg),

Weekly and cumulative mortality.

At the beginning, middle, and end of the trial, 10 hens from each treatment were weighed to calculate weight gain.

Egg quality was evaluated at the middle and end of the trial using a DET 6000 texturometer from Nabel, with 6 eggs per replicate.

At the end of the trial, 2 hens per treatment were sacrificed to obtain tibias, both were cleaned of muscle tissue and refrigerated at 4°C for subsequent shipment to the laboratory.

Excreta were collected over a period of 12 hours, collection trays were placed under 4 replicates per treatment, and a 150 g sample was taken from each replicate.

They were then refrigerated at 4°C for shipment to the laboratory. Ash, minerals, and moisture determinations were performed in the animal systems laboratory.

Additionally, a simple linear regression was performed where X was the levels of digestible phosphorus included in the diet, and Y = response variable.

In the results obtained during the 12 weeks of experimentation from week 38 to 50 of the hens’ life, on weekly and cumulative productive parameters it is observed that laying percentage, egg weight, feed intake per bird per day, percentage of broken and dirty eggs, were not affected by different levels of digestible phosphorus and fixed levels of total calcium (P>0.05).

The number and kilograms of accumulated eggs were similar in the 5 treatments (P>0.05) perhaps because despite the different levels of digestible phosphorus and fixed levels of total calcium in the formulas, the hens meet their phosphorus and calcium needs including the lowest level of digestible phosphorus used in the study (0.254%).

Since there is no information on productive performance based on digestible phosphorus, the equivalence in available phosphorus was taken.

These results agree with those found by Acosta A, (2009) who mentions that the percentage of available phosphorus in the diet can be reduced to 0.25%, without observing an adverse effect on production. With the equivalence in digestible phosphorus of 0.254%, a similar productive performance was obtained as with the maximum value studied (0.402% digestible phosphorus).

Results of the percentage of broken eggs, which did not differ between the treatments used (P>0.05), similar results were obtained when measuring shell strength, where the values at the middle of the trial were between 5078.75 and 5462.70 g/cm2, and for the values at the end of the trial 5014.70 and 5440.40 g/cm2.

These values were above those mentioned for the age of Hy-Line W80 hens 2019.

This is because when mineral availability such as calcium, phosphorus is efficient, they make deposition in the protein matrix adequate to form a strong shell and therefore the shell breaking force is higher.

Contrary to what M. Skřivan (2010) mentions where both high levels of available phosphorus (0.41%) and low levels (0.2%) tend to decrease shell quality, which was not observed in this experiment.

This suggests that the current recommended digestible phosphorus level of 0.36% by the Hy-Line W80 manual for laying hens aged 35 to 55 weeks could be reduced to values close to 0.25%, without altering productive indicators. This can be attributed to the greater capacity of laying hens to utilize phosphorus.

In the internal egg quality, no differences were found between the Haugh units of the different treatments (p>0.05).

The results of the excreta analysis (percentage of moisture, Ca, and P) of hens fed with different levels of digestible phosphorus and fixed levels of total calcium showed no difference (p>0.05), indicating that the levels of digestible phosphorus did not influence the total phosphorus excreted, additionally considering that the reduction of phosphorus excretion is important for lower environmental contamination.

From the results obtained under the experimental conditions used, it can be concluded that a concentration of digestible phosphorus ranging from 0.254% to 0.402%, with a total calcium concentration of 4.1% in the feed, in diets for Hy-Line W80 hens aged 38 to 50 weeks, is suitable for maintaining the performance of laying hens without affecting their calcium and phosphorus reserves in bone marrow and without compromising egg quality.

The results of the analysis of ash content, phosphorus, and calcium in the tibias of hens fed with different levels of digestible phosphorus did not show differences between the treatments (p>0.05).

Keshavarz (2000), Gordon and Roland (1997), and Sohail and Roland (2000) reported similar results to those obtained in the present study regarding the percentage of ash in bones with low-phosphorus diets.

The phosphorus content in the bone was not affected by the level of digestible phosphorus in the diet. In the same context, the amount of calcium also showed no change (p>0.05).

Therefore, there would be an economic advantage in using a diet with low concentrations of digestible phosphorus over higher concentrations.

Results tables and references available upon request

Sérgio Gonçalves Mota1, Geovana Rocha Placido2

1Postgraduate Student in the Food Technology program at IF Goiano - Rio Verde Campus

2Professor in the Postgraduate Program in Food Technology at IF Goiano - Rio Verde Campus

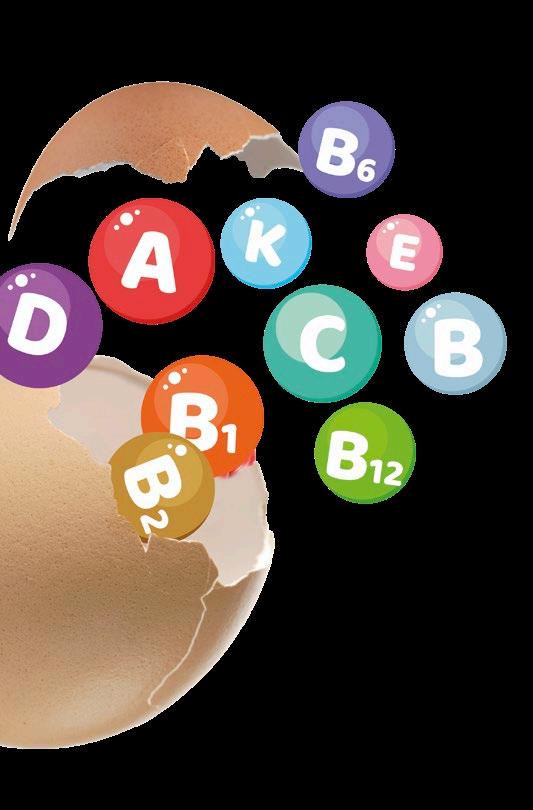

Vitamins constitute crucial organic compounds that birds cannot synthesize themselves, making their inclusion in the diet essential. These compounds act as catalysts for chemical reactions, playing a vital role in facilitating important biochemical processes.

Provitamins, such as carotenoids (provitamin A) and sterols (provitamin D), are substances that the body can convert into vitamins.

Based on their solubility, vitamins are classified as:

Fat-soluble vitamins:

These vitamins dissolve in fat, which is a crucial property that enables their organic storage.

Vitamins A, D, E, and K are part of this group.

Fat-soluble vitamins:

Vitamin A (Retinol/Beta-Carotene)

Growth and tissue development

Antioxidant activity, Reproductive functions, Epithelial integrity

Crucial for the development of vision

Water-soluble vitamins:

This group of vitamins has the proberty of being water soluble, and they include vitamin C and the B complex. Unlike fat soluble vitamins, they cannot be stored in the organism. Hence they are quickly absobed and excreted.

Vitamin K

One of its main functions is to catalyze the synthesis of blood coagulation factors, which takes place in the liver. It plays a role in the production of prothrombin, which combined with calcium, has a coagulant e ect.

Furthermore, it is essential for maintaining bone health.

It plays a role in development, promoting the strength of bones, muscles, and nerves. A D E K

Vitamin D

It participates in the absorption of calcium and phosphorus.

Vitamin E (also known as Tocopherol)

Antioxidant action, protects cells from damage caused by free radicals.

CVitamin C

It has antioxidant action, promotes healing, and plays a role in the development and maintenance of tissues, including the bone matrix, cartilage, collagen, and connective tissue.

The B-complex consists of eight vitamins, which are:

Thiamine (B1)

Responsible for releasing energy from carbohydrates, fats, and alcohol.

Fundamental neuroprotective activity.

Niacin (B3)

Required for energy production in cells.

Contributes to enzyme functions involved in fatty acid metabolism, tissue respiration, and toxin removal.

Pyridoxine (B6)

Ribo avin (B2)

Provides energy for the growth of young birds as well as for the recovery and maintenance of tissues.

It plays an important role in the central nervous system, participates in lipid metabolism, in the structure of phosphorylase, and in the transport of amino acids through the cell membrane.

Biotin (B8)

Folate (B9) Folic acid

B2 B8 B12 B5

It participates in the Krebs cycle producing energy through lipid synthesis, and the excretion of protein waste.

B3 B9

Pantothenic Acid (B5)

Transformation of energy from fats, proteins, and carbohydrates into essential substances such as hormones and fatty acids.

Acts as a coenzyme in carbohydrate metabolism, maintains immune system function, works alongside vitamin B12. It is involved in the synthesis of DNA and RNA, and participates in the formation and maturation of blood cells.

Cobalamin (B12)

Acts as a coenzyme in amino acid metabolism and in the formation of the heme portion of hemoglobin; essential for DNA and RNA synthesis; participates in the formation of red blood cells.

Managing bird temperatures is a key obstacle in tropical poultry farming. Elevated ambient temperatures during growth and fattening phases lead to a series of responses encompassed under the condition referred to as heat stress.

Feed consumption

A ects muscle synthesis

Excretion of important minerals for the organism

Several biological mechanisms alleviate heat stress, including panting, sweating, and vasodilation. When heat stress prevails, there is a decrease in both feed consumption and bird activity (as shown in Figure 1).

Nutrient digestibility

Birds spend more time drinking water, resting, and panting. Their ability to control temperature is diminished, especially due to their high body temperature (between 41 and 42 ºC) and the lack of sweating mechanisms, which are present in other animal species.

Heat stress can also reduce nutrient digestibility, fat deposition, and muscle formation in birds.

Water consumption

Activity level

Decreases vitamin concentrations

Furthermore, it can trigger respiratory alkalosis and hinder the immune function of broiler flocks. But how does this relate to vitamins?

Heat stress also results in a reduction in the body’s levels of antioxidant vitamins, including vitamins C, A, and E. It also increases the excretion of vital minerals crucial for plasma composition and tissue development, leading to cell damage.

Figure 1: Effects of heat stress on poultry productionVitamin C, also recognized as L-ascorbic acid, is a robust antioxidant typically produced in the liver and kidneys of birds.

Various literature recommendations suggest supplementing vitamin C to alleviate the effects of heat stress, assuming that during such conditions, the demand for this vitamin may exceed its organic synthesis capacity.

The role of vitamin C is linked to the synthesis of white blood cells and, as a result, it positively impacts bird health.

Incorporating ascorbic acid into the diet can enhance carcass characteristics, ensure the formation of blood components, and, most importantly, mitigate the adverse effects on the growth of chickens reared under heat stress.

Research has demonstrated that adding vitamin C to the diet improves feed consumption, average daily weight gain, and feed conversion.

Vitamin E, as a significant fat-soluble antioxidant, provides protection against oxidative stress.

It cannot be synthesized by birds and relies entirely on dietary supplementation. According to the NRC (1994), the recommended dietary vitamin E content for broiler breeders is 6 mg/kg.

In addition to its role as an antioxidant, vitamin E plays a vital role in broiler breeder productivity, egg quality, hatchability, and, most notably, the quality of hatched chicks.

Vitamin E mitigates ovarian aging resulting from oxidative stress, which is responsible for the reduced productivity of older laying hens.

Studies indicate that dietary supplementation in broiler breeders has positive effects on increasing the antioxidant capacity of egg yolks and enhancing embryo and chick development.