The availability and quality of inorganic mineral sources have become critical concerns in modern livestock nutrition. Poultry, swine, and cattle rely on essential minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, zinc, and copper to support growth, immune function, and overall productivity. However, fluctuating global supply chains, increasing costs, and environmental concerns regarding excessive mineral excretion have placed pressure on the industry to reassess mineral supplementation strategies.

Inorganic mineral sources, commonly used in animal diets, often face challenges related to bioavailability and absorption efficiency. Factors such as interactions with other dietary components, mineral antagonisms, and environmental losses can limit their effectiveness, reducing the return on investment for producers. The search for sustainable and highly bioavailable alternatives, such as organic trace minerals novel formulations, is gaining traction. These alternatives not only enhance nutrient utilization but also contribute to reducing mineral excretion, aligning with regulatory and environmental sustainability goals.

Join us as we navigate the complexities of animal nutrition and discover how innovation is shaping the future of feed formulation. Your livestock’s health and productivity depend on it!

Coordinator

EDITOR

COMMUNICATION GROUP AGRINEWS LLC

ADVERTISING

Luis Carrasco +(34) 605 09 05 13 lc@agrinews.es

Simone Dias +55 11 9 8585-2436 nutribr@grupoagrinews.com

Gustavo Quintana-Ospina +(1) 754 207 1272 g.quintana@agrinewsgroup.com

Producers and nutritionists must remain informed about the latest advancements in mineral supplementation to optimize feed efficiency and animal performance while mitigating risks associated with mineral deficiencies or excesses. this issue of NutriNews, we explore the barriers and opportunities in animal nutrition, discuss the latest trends on nutrition approaches for different species, weathers, and challenges, and provide insights from leading experts on sustainable supplementation strategies.

SALES DEPARTMENT

Gustavo Lander +(34) 664 66 06 05 int@grupoagrinews.com

Ivan Martos +(34) 664 66 06 02 im@grupoagrinews.com

CUSTOMER SUPPORT

Mercé Soler

EDITORIAL STAFF

Álvaro José Guzman

Gustavo Quintana

TECHNICAL DIRECTION

Dr. Edgar Oviedo (poultry)

info@grupoagrinews.com nutrinews.com grupoagrinews.com

Free distribution magazine AIMED AT VETERINARIANS AND TECHNICIANS

Subscription price 125$

nutriNews International

Legal Deposit B15281-2024

ISSN PRINTED VERSION 2938-8910

ISSN DIGITAL VERSION 2938-8929

Images: Noun Project / Freepik/Dreamstime

Gustavo Quintana-Ospina

Techincal Coordinator, nutriNews

Still using Choline Chloride in animal nutrition? Discover its risks and a superior natural alternative

Felipe Horta Product Manager Latam, Nuproxa Group

Edgar O. Oviedo-Rondón North Carolina State University

Ana C. B.Doi1 , Alana B. Serraglio2 , Vivian I. Vieira1 , Simone G. de Oliveira1,3

1Graduate program in Animal Science; 2Graduate program in Veterinary Sciences; 3Adjunct profesor; Parana Federal University, Curitiba/PR

Use of oxidized fats in swine feeding: benefits, risks and considerations Part I

Gerardo Ordaz Ochoa, Maria Alejandra Perez

Alvarado, Luis Humberto Lopez Hernandez

The National Research Center for Animal Physiology and Improvement, INIFAP, Mexico

Juan Gabriel Espino Independent Nutritionist

54

Smart Nutrition: Targeted Strategies to Combat Necrotic Enteritis in Broilers

M Naeem

Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Poultry Science, Auburn University

60

Navigating Poultry Nutrition in a Tropical Environment: Strategies Amid Unique Challenges

Tanika O’Connor-Dennie PhD, Managing Director | Consultant Animal Nutritionist specializing in tropical nutrition

68

Protein in Aquafeeds: Balancing Requirements, Sources, and Efficiency

Jairo Gonzalez School of Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences, Auburn University

Gustavo Quintana-Ospina. DVM. MS. Technical Coordinator nutriNews International

In modern animal nutrition, optimizing growth performance, feed efficiency, and overall health requires a precise balance of macro and micro minerals.

While macro minerals like calcium, phosphorus, and sodium often receive the most attention, micro minerals—also known as trace minerals—play an equally vital role in metabolic processes, immune function, and structural integrity in poultry, swine, and cattle.

These micro minerals, which include zinc, copper, manganese, selenium, iron, iodine, and cobalt, must be adequately supplied in animal diets to ensure optimal productivity and well-being.

Micro minerals are required in minute amounts, typically measured in parts per million (ppm), yet their deficiency or excess can significantly impact animal health and performance. Each trace mineral has specific biological functions, many of which involve enzymatic reactions, hormone regulation, and antioxidant activity.

Zinc (Zn): Essential for immune function, enzyme activation, and skin integrity.

Copper (Cu): Plays a key role in iron metabolism, connective tissue formation, and antioxidant defense.

Manganese (Mn): Important for bone formation, enzyme function, and energy metabolism.

Selenium (Se): Works in synergy with vitamin E to prevent oxidative stress and supports reproductive health.

Iron (Fe): Necessary for hemoglobin formation and oxygen transport in the blood.

Iodine (I): Crucial for thyroid hormone synthesis, which regulates metabolism.

Cobalt (Co): Primarily needed in ruminants for vitamin B12 synthesis by rumen microbes.

Poultry production systems demand precise nutrient formulations to maximize growth, egg production, and feed efficiency. Deficiencies in trace minerals can lead to various metabolic disorders and reduced performance.

Zinc is integral to over 300 enzymes involved in metabolic functions, immune response, and feather development. A deficiency in zinc can lead to poor feathering, reduced growth rates, and lower egg production in laying hens. Recent studies suggest that organic zinc sources, such as zinc proteinate or zinc chelate, improve bioavailability compared to inorganic sources like zinc sulfate.

Beyond growth and feathering, zinc plays a crucial role in skeletal development, enzyme function, and oxidative stress reduction in poultry. Research has shown that inadequate zinc levels can impair leg strength, making birds more susceptible to skeletal abnormalities, particularly in broiler production.

Proper supplementation strategies ensure that birds maintain strong bone structures and overall robustness throughout their lifecycle.

Copper serves as a cofactor for enzymes involved in iron metabolism and connective tissue synthesis. In poultry, dietary copper supplementation has been linked to improved feed conversion ratios and gut health. High doses of copper sulfate have also been used as an antimicrobial growth promoter in some production systems, but environmental concerns have led to stricter regulations on its usage.

In addition to its metabolic functions, copper has been recognized for its positive impact on cardiovascular health and enzyme activity in poultry. Studies indicate that copper supplementation enhances antioxidant enzyme activity, reducing oxidative damage and promoting better overall health. Careful formulation and the use of chelated copper sources can optimize its benefits while minimizing environmental concerns.

Manganese plays a crucial role in bone formation and eggshell quality. Deficiency in manganese can lead to perosis, a skeletal disorder causing deformities in leg bones and joint swelling in broilers. Ensuring adequate manganese intake helps prevent leg abnormalities and supports reproductive performance in breeders.

Manganese is also integral to reproductive efficiency in poultry, particularly in breeding programs. Research suggests that hens with sufficient manganese intake exhibit improved egg production, hatchability rates, and shell strength.

Proper supplementation is necessary to support both skeletal and reproductive health in modern poultry systems.

Selenium is vital for antioxidant defense mechanisms, working in conjunction with glutathione peroxidase to reduce oxidative stress. Selenium deficiency can cause exudative diathesis, muscular dystrophy, and reduced hatchability in breeder flocks. Organic selenium sources, such as selenium-enriched yeast, have been shown to enhance bioavailability and deposition in eggs.

Selenium also contributes to overall bird health by supporting immune function and disease resistance. Poultry under oxidative stress or facing disease challenges benefit from selenium supplementation, which enhances their resilience and productivity. Proper selenium levels help birds combat inflammation and maintain high performance, particularly under intensive production conditions.

Swine nutrition programs must address the specific trace mineral requirements of pigs at different production stages, from piglets to sows and finishing hogs.

Zinc is particularly important for piglets due to its role in immune function and skin integrity. Zinc oxide is commonly included in piglet diets to control postweaning diarrhea, though regulatory limitations on high inclusion levels are driving interest in more bioavailable organic zinc sources.

Additionally, zinc supports reproductive performance and hoof health in breeding sows and boars. Zinc deficiencies can result in reproductive failures, poor hoof integrity, and reduced litter sizes. Providing appropriate zinc levels ensures optimal fertility and overall herd productivity.

Copper is often included in swine diets not only for its essential metabolic functions but also as a growth promoter at pharmacological levels. However, excessive copper excretion can contribute to environmental pollution, necessitating more sustainable strategies such as using copper chelates for improved bioavailability.

Beyond its traditional roles, copper also supports gut health and reduces pathogenic bacterial loads in the gastrointestinal tract. By enhancing digestive efficiency and nutrient absorption, optimized copper supplementation contributes to better feed conversion and growth performance in pigs.

Iron deficiency is a common concern in piglets, especially those reared in confined systems without access to soil, a natural iron source. Neonatal piglets require iron supplementation, often administered via injectable iron dextran, to prevent anemia and support optimal growth.

Iron also plays a crucial role in immune function and overall vitality in growing pigs. Ensuring adequate iron intake throughout different production stages helps optimize oxygen transport and metabolic function, reducing stress and improving overall resilience.

Selenium enhances immune function and reproductive performance in sows. Deficiencies can lead to reproductive failure and white muscle disease. Organic selenium sources are increasingly favored due to their superior absorption and retention in tissues.

Selenium’s antioxidant properties also aid in muscle development and recovery in finishing pigs. By reducing oxidative stress, selenium supports better growth rates, meat quality, and overall swine health, making it an essential component of a wellbalanced nutrition program.

In ruminants, micro minerals play a critical role in digestion, reproduction, and immune function. Unlike monogastric species, ruminants rely on microbial fermentation in the rumen to modify mineral availability.

Zinc supports hoof health, reproduction, and immune response in cattle. Deficiencies can lead to poor feed intake, impaired growth, and dermatitis. Supplementing with organic zinc improves absorption and reduces the risk of foot disorders like digital dermatitis in dairy cattle.

Zinc is also crucial for rumen microbial activity, enhancing fiber digestion and nutrient utilization. Proper zinc levels help maintain optimal rumen function, supporting both milk production in dairy cows and growth efficiency in beef cattle.

Copper is essential for enzyme activation and immune system function. Copper deficiency, often exacerbated by high dietary levels of sulfur and molybdenum, results in anemia, poor growth, and reduced fertility.

Chelated copper forms can enhance bioavailability and mitigate antagonistic effects. Additionally, copper influences nervous system function and red blood cell production, making it a vital mineral for maintaining overall health and metabolic efficiency in both beef and dairy cattle.

Selenium deficiency is a well-documented concern in cattle, leading to white muscle disease in calves and impaired fertility in cows. Selenium supplementation, either through mineral premixes or injectable forms, supports antioxidant defenses and reproductive efficiency.

In dairy cattle, selenium also plays a role in improving milk quality by reducing oxidative stress and supporting immune function, which helps prevent mastitis and other production-related diseases.

Cobalt is unique to ruminants as it is required for the microbial synthesis of vitamin B12, which is essential for energy metabolism. Deficiencies can cause reduced feed intake, poor growth, and anemia. Proper cobalt supplementation ensures optimal rumen function and overall productivity.

Cobalt also impacts metabolic efficiency by supporting gluconeogenesis, a key energy-generating process in ruminants that ensures steady energy availability for growth, lactation, and reproduction.

Micro minerals are essential components of livestock nutrition, playing critical roles in metabolism, immune function, and productivity. Proper supplementation and balanced mineral intake can significantly enhance animal health, growth, and reproductive efficiency.

With evolving regulations and environmental concerns, a strategic approach utilizing organic mineral sources and precision feeding is key to sustainable animal production.

Micro Minerals, Macro Impact: Enhancing Poultry, Swine, and Cattle Nutrition DOWNLOAD ON PDF

Edgar O. Oviedo Rondón

Prestage Department of Poultry Science, North Carolina State University

The utilization of synthetic and crystalline, or nonbound, amino acids is rapidly increasing in the feed industry due to interest in minimizing dietary crude protein and the inclusion of soybean meal or other products that may have a high environmental impact.

The feed amino acid market is estimated at 8.38 billion US dollars in 2025. It is expected to reach 10.71 billion US dollars by 2030, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 5%.

Non-bound amino acids accounted for 22.1% of the global feed additives market value in 2022.

The growing emphasis on precision animal nutrition has led to increased investment in research and development, resulting in more efficient amino acid formulations and application methods.

The development of new fermentation technologies and improved extraction methods have resulted in higher purity levels and better bioavailability of amino acids in animal feed.

These technological advancements have also reduced production costs, making amino acid supplementation more accessible.

Nowadays, not only lysine, methionine, threonine, valine, and tryptophan but also arginine, glutamine, and isoleucine are commonly included in feeds.

The sources of these amino acids are highly variable due to the form and concentration in which they are produced.

Their molecular formula can determine the nitrogen content of pure (100%) amino acids.

The historical conversion factor for calculating crude protein from the nitrogen percentage is 6.25. This is based upon a typical protein containing 16% nitrogen.

However, it has been shown that the 6.25 factor is incorrect for most all feed ingredients.

The nitrogen content on a 100% potency for 20 amino acids on a dry matter basis is shown in Table 1. It is typically not 16%, averaging only 14.74% if each amino acid monomer was only represented once in a given protein. So, the appropriate nitrogen correction factor for any given amino acid or protein is not 6.25.

The amino acid sources available in the poultry industry are not pure. All feed amino acids available vary in their final composition, and nutritionists should consider this variation in their formulation matrix.

Amino acids contain energy, and their specific value has been estimated or determined in experiments with poultry and swine.

Table 2 presents some values reported for 100% pure amino acids. However, feed amino acids may vary depending on the provider and concentration.

Source: www.researchgate.net

1100% pure (USP) amino acids on a dry matter basis. 2Reported as Cystine. 3Converted from hydrogen chloride form. 4Safety Margin: 0.5 SD = (Mean–0.5 x SD). 5Safety Margin: LCI = 95% lower confidence interval (Mean–1.96 x SD/SQRT(n)) NRC. 1994. Nutrient requirements of poultry. 9th rev. ed. Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, DC. INRA. 2004. Tables of composition and nutritional value of feed materials. Pages 297 in Sauvant, D., J. M. Perez, and G. Tran eds. Wageningen Academic Publishers The Netherlands & INRA Paris, France. CVB. 2023. Feed Table–Chemical composition and nutritional values of feedstuffs. Accessed Feb 7, 2025. https://www.cvbdiervoeding.nl/pagina/10081/downloads.aspx 709 pages. Rostagno, H. S., L. F. T. Albino, A. A. Calderano, M. I. Hannas, N. K. Sakomura, F. G. Perazzo, G. C. Rocha, A. Saraiva, M. L. Teixeira de Abreu, J. Luiz Genova, and F. de Castro Tavernari. 2024. Brazilian tables for poultry and swine. Composition of feedstuffs and nutritional requirements. 5th ed. Viçosa: UFV.

Table 2. N-corrected Apparent Metabolizable Energy (AMEn, kcal/kg) for 20 amino acids.1

Tables 3 and 4 summarize the nutrient and energy values reported by several suppliers for their diverse amino acid products.

Nutritionists should consider these differences to matrix each product correctly. The accuracy in these values may contribute to improving precision in feed formulation.

1Methionine Hydroxy-analogue. 2Digestible energy swine 4,699 kcal/kg. Sulfur 19%.. 3Dry matter 98.2%, phosphorus 0.13%, additional amino acids of the biomass: Methionine 0.08%, cysteine 0.04%, Methionine + Cystine 0.12%, Threonine 0.24%, Tryptophan 0.02%; Arginine 0.61%, Isoleucine 0.24%, Leucine 0.50%, Valine 0.33%. Digestible energy swine 4,230 kcal/kg and 18.07 MJ/kg. 4Digestibility 100.0%. 5Digestibility 100%, Digestible energy swine 4,030 kcal/kg or 16.9 MJ/kg. 6Digestibility 1005; Digestible energy swine 6,540 kcal/kg or 27.4 MJ/kg.

Table 3. Crude protein, digestible methionine equivalent, and energy content of amino acids distributed by Adisseo https://www. adisseo.com/en/, Evonik https://animal-nutrition.evonik.com/en/products-and-solutions/amino-acids and NOVUS International https://www.novusint.com/methionine/

Ana C. B.Doi1*; Alana B. Serraglio2*; Vivian I. Vieira1*; Simone G. de Oliveira3*

1Graduate program in Animal Science;

2Graduate program in Veterinary Sciences;

3Adjunct profesor; Parana Federal University, Curitiba/PR

On a global scale, according to the USDA (2024), the United States leads the ranking in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) production with 8,071 million tons, followed by Nigeria and Sudan.

Originating from Africa, sorghum is recognized for its nutritional properties, standing out for its remarkable adaptability to adverse climatic and soil conditions, greater tolerance to water stress, high energy value, and versatility as an ingredient in the feed of production animals (Nunes, 2005; Carvalho, 2010).

However, its inclusion in diets requires a careful analysis of variations in its composition, particularly concerning its high tannin content and anti-nutritional factors, which can negatively impact digestibility and animal performance (Selle et al., 2018).

From a nutritional perspective, practical recommendations suggest using 30% sorghum in diets for broilers during the starter phase and laying hens, and 35% in diets for finishing pigs.

There are various sorghum varieties, such as forage sorghum, sweet sorghum, broom sorghum, biomass sorghum, and grain sorghum, which are used to feed monogastric animals.

Grain Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) is a short-growing type of sorghum that produces a panicle at its upper end, where the grains are located. Grain sorghum crops vary in terms of grain yield, disease tolerance, vegetative cycle, and other agronomic characteristics (Melo et al., 2023).

Sorghum grains exhibit a wide range of colors, with the most common being white, bronze, and gray. Although the grains are generally spherical, their size and shape can vary (Nunes, 2000).

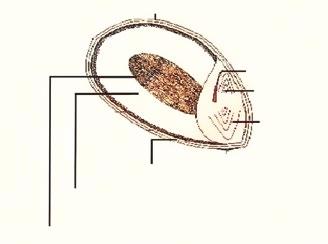

The sorghum grain consists of three main parts: Pericarp, endosperm, and germ (Figure 1). The relative proportion of these components varies, but in most cases, it is 6% pericarp, 84% endosperm, and 10% germ (Pereira Filho & Rodrigues, 2015).

Scutellum

Coleoptile

Germ

Seed coat

Vitreous endosperm

Floury endosperm

Figure 1. Structure of Sorghum grain. Source: Adapted from Nunes (2000)

The pericarp is composed of three layers: epicarp, mesocarp, and endocarp, and just beneath it lies the seed coat (tegument), the structure where tannins are located.

The germ consists of two tissues, the coleoptile and scutellum, which contain lipids, proteins, enzymes, and minerals.

Approximately 88% of starch granules and 80% of proteins are found in the endosperm, which consists of both floury and vitreous portions (Scramin, 2013; Pereira Filho & Rodrigues, 2015).

Additionally, starch granules are also deposited in the mesocarp, which explains the high starch content of this cereal (Nunes, 2000).

Sorghum is a cereal similar to corn; however, there are differences in their nutritional profiles (Gomes, 2020). This cereal exhibits significant genetic variability and variations in its proximate composition, as shown in Table 1.

Source: ¹ Rostagno et al., (2017); ² Martino et al., (2012); ³ Antunes et al., (2007); 4 López y Stumpf Junior, (2000).

As an energy-rich cereal, the starch content in sorghum represents the majority of the grain, with 70-80% consisting of amylopectin chains and 20-30% composed of amylose chains.

On average, sorghum contains 3% ether extract, 12% fiber, and 78% total digestible nutrients (Martino et al., 2012; Pereira Filho & Rodrigues, 2015).

In terms of energy utilization values, sorghum grain provides 3,204 kcal/kg of metabolizable energy for poultry and 3,358 kcal/kg for pigs, compared to corn, which offers 3,364 kcal/kg and 3,360 kcal/kg, respectively, as reported by Rostagno et al. (2017).

This demonstrates that sorghum is a viable energy-rich ingredient with the potential to substitute corn.

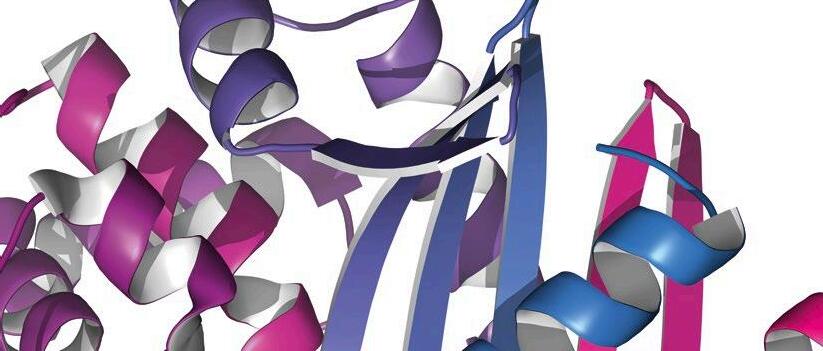

Among the protein content of the grain, kafirins are the most abundant and are stored within protein bodies, contributing to their stability and protection.

The vitreous endosperm portion of sorghum is thicker compared to the floury endosperm, which is primarily composed of proteins and non-starch polysaccharides. It is characterized by being dense, hard, and resistant to water penetration and enzymatic activity (Sapaterro et al., 2011).

Similar to zeins in corn, sorghum contains kafirins, which are prolamins, a group of storage proteins.

However, this protective structure can hinder the action of digestive enzymes, reducing protein digestibility (Belton et al., 2006). Additionally, kafirins form intra- and intermolecular disulfide bonds, which further complicate their breakdown (Abdelbost et al., 2023).

Figure 2 presents a characterization of the sorghum grain endosperm, allowing the identification of starch granules surrounded by prolamins, specifically kafirins.

Despite the nutritional importance of sorghum in animal feed, the presence of antinutritional components in the grain can negatively affect digestibility and nutrient absorption, directly influencing animal performance and health.

These compounds play a defensive role for the plant against birds and pathogens, as sorghum seeds lack physical protection, unlike corn husks, for example. (Magalhães et al., 2001).

However, despite the benefits these compounds provide during plant development, when included in monogastric animal diets, they can compromise digestibility, preventing the animal from fully expressing its performance potential.

The main antinutritional factors found in sorghum grain include phenolic compounds such as tannins and phytates, as well as cyanogenic glycosides and flavonoids (Marques et al., 2007; Lima Júnior et al., 2010; Selle et al., 2018).

It is well understood that plants absorb mineral nutrients from the soil and transfer them to the grain. However, the way these nutrients are stored often makes them unavailable to animals that lack specific enzymes to break the bonds within these macromolecules.

This is the case for phosphorus, which is stored in plants as phytic acid, also known as phytate. The total phosphorus content in sorghum seeds is 4.03 g/kg, of which 3.26 g/ kg is complexed with phytate, making it less bioavailable for monogastric animals.

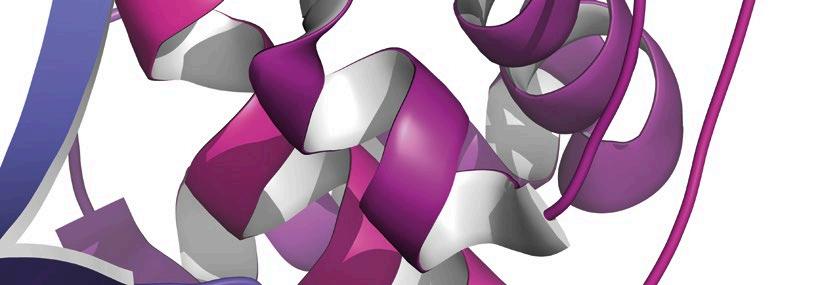

Additionally, phytic acid can hinder digestion by binding directly or indirectly to proteins, starch, and minerals such as calcium, iron, zinc, and copper (Rooney e Pflugfelder, 1986; Liu et al., 2013; Selle et al., 2018) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Structure of a phytate complexed with calcium ions (C₆H₆Ca₆O₂₄P₆). Source: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ compound/24495

Tannins are phenolic compounds that can interact with and form complexes with the storage proteins in sorghum grain. These compounds can be classified into two categories: Water-soluble tannins and Condensed tannins.

Among these, condensed tannins are the most prevalent and play a major role in the low digestibility of sorghum (Scramin, 2013). For monogastric animals, tannins have negative effects, as they bind to proteins, leading to a reduction in both palatability and digestibility of the grain (Pereira Filho & Rodrigues, 2015).

Sorghum grains are often contaminated by various fungi, leading to significant losses in terms of health, physical quality, and nutritional value.

During the deterioration process, these fungi can cause the degradation of essential components such as proteins, sugars, and carbohydrates.

Among the most important mycotoxins that can contaminate sorghum grains are: aflatoxins, zearalenone, fumonisins, T-2 toxin (Iamanaka et al., 2010).

It is important to recognize that the presence and concentration of these substances can vary significantly depending on the sorghum variety and the growing conditions to which the plant has been subjected.

Proper processing procedures, such as storage and grain milling, can help reduce the presence of some of these toxins, thereby promoting the quality and safety required for Brazilian animal nutrition.

It is evident that fluctuations in corn prices result in significant increases in production costs for sectors dependent on this cereal.

In this context, one option is to transition to alternative feed ingredients, such as sorghum, which can partially replace corn (Parreira Filho et al., 2020).

Hybrid waxy sorghum is characterized by having 100% amylopectin in its starch composition (Zardo & Lima, 1999). Additionally, there are already tanninfree and phenolic compound-free varieties available on the market.

In poultry and swine diets, the complete replacement of corn can only be considered with the tannin-free sorghum variety.

The nutritional value of sorghum grain is significant and comparable to that of corn, which is why its use as a substitute for corn in diets for laying hens, broilers, and pigs is widely accepted (Fernandes et al., 2014).

Hybrid strains have improved the starch composition of sorghum, leading to better grain digestibility.

However, it is necessary to consider the structural differences in the bonds between carbohydrate and protein sources, as well as the storage of these complexes in sorghum grain.

The substitution of corn with sorghum grain could be a promising alternative for monogastric animals.

Primiparous sows, during lactation and post-weaning phases, fed with diets containing sorghum and corn, showed similar performance to those fed exclusively with corn, indicating that partial grain substitution is viable for production (Moreira et al., 2013).

On the other hand, studies with piglets and castrated males have demonstrated that sorghum can replace corn up to 100% in rations without negatively affecting animal performance or nutrient digestibility (Fernandes et al., 2014).

Likewise, this substitution can be carried out without causing negative impacts on poultry performance, broiler carcass yield, and egg quality in laying hens (Assuena et al., 2008; Rocha et al., 2008).

It is important to highlight that, like other grains, for use in poultry and pig nutrition, certain specifications are required, such as a moisture content of 13%, 3% crude fiber, 1.5% mineral matter, and up to 20 ppm of aflatoxin. Additionally, it must have a minimum crude protein value of 7% and 2% ether extract (Compêndio, 2017).

The digestibility of sorghum can vary depending on several factors, such as the sorghum variety, processing methods, the presence of other components in the diet, and the target animal.

In general, sorghum is known to have lower protein digestibility compared to other cereals such as wheat, rice, and corn. This is partly due to the presence of antinutritional factors, which can affect protein and other nutrient digestibility (Marques et al., 2007).

Additionally, the low digestibility of kafirins may also contribute to the overall low digestibility of sorghum (Belton et al., 2006).

Another influencing factor is the distribution of proteins surrounding the starch granules in the endosperm (Sapaterro et al., 2011). In the floury endosperm, there are larger granules surrounded by a discontinuous protein matrix with a lower amount of proteins.

In the vitreous endosperm, the granules are smaller, and the matrix is more continuous (Paes, 2006). The characterization of sorghum proteins may hinder access to starch granules and, consequently, reduce their digestibility.

It is important to note that sorghum digestibility can be optimized through processing techniques such as grinding and thermal treatments.

The reduction in particle diameter resulting from grinding has a positive impact on nutrient digestibility and animal performance (Leandro et al., 2001).

Cooking, for example, can enhance sorghum protein digestibility by inactivating antinutritional factors, promoting the breakdown of protein structures, and improving protein solubility (Nunes, 2000; Margier et al., 2018). Additionally, it can improve starch digestibility through granule gelatinization.

Supplementing sorghum-based diets with enzymes is also an effective strategy to enhance nutrient digestibility (Leite et al., 2011) and mitigate the effects of certain compounds present in the grain (Zanella, 1999; Barbosa et al., 2008).

The use of xylanases, cellulases, and glucanases can improve grain digestion and enhance animal performance, such as feed conversion efficiency in broilers during the starter phase (Leite et al., 2011). Furthermore, hybrid sorghum varieties have been developed to increase nutrient digestibility (Marques, 2007).

This material has explored various aspects related to the use of sorghum in animal nutrition, from its morphological characteristics and nutritional composition to its digestibility and application in monogastric animals.

By examining the digestibility of sorghum, it becomes possible to assess its viability as a source of energy and nutrients for swine and poultry.

Furthermore, the inclusion of sorghum in animal feed presents economic and environmental advantages, offering a cost-effective alternative to corn, particularly in regions where corn cultivation may be challenging.

However, it is crucial to consider the presence of anti-nutritional factors and toxins in the grain, which can negatively impact animal health and performance.

Mitigation strategies, such as selecting sorghum varieties with lower levels of these compounds, applying appropriate processing techniques, and using feed additives, are essential to ensuring the safe and effective utilization of sorghum in animal nutrition.

Unlocking the Potential of Sorghum in Poultry and Swine Nutrition DOWNLOAD IN PDF

Felipe Horta, MV, MSc

Product Manager Latam Nuproxa Group

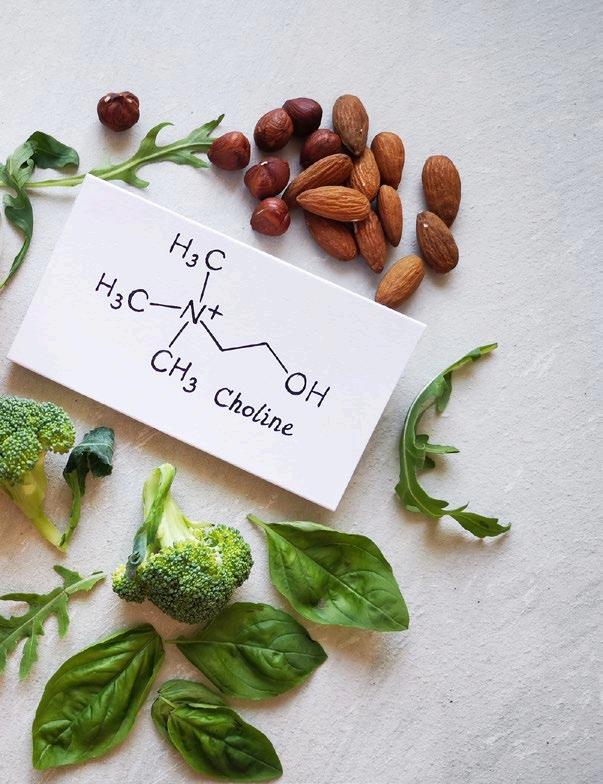

INTRODUCTION: THE CRITICAL ROLE OF CHOLINE IN ANIMAL NUTRITION

Choline is an essential nutrient that plays both nutritional and regulatory roles within the organism. It is a precursor for sphingomyelin, a component of animal cell membranes, particularly in the myelin sheath surrounding nerve cells, which is crucial for proper nerve function.

Another vital substance synthesized from choline is acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter involved in muscle control and various brain functions (Workel et al., 2004).

Additionally, choline serves as the precursor for phosphatidylcholine, a major constituent of cell membranes, and is involved in methylation processes, contributing to the recycling of methionine (Zeisel, 2004)

Beyond its basic nutritional roles, choline also plays a regulatory function, especially in energy metabolism and the utilization of fats (Moretti et al., 2020).

As a methyl group donor, choline participates in various biochemical processes, including the metabolism of fats, proteins, and DNA, and is involved in maintaining proper cell function and structure (Blusztajn et al., 2012; Obeid, 2013)).

Choline chloride is one of the most commonly used forms of choline in animal nutrition, available in different concentrations. Typically, choline chloride is found in concentrations of 50% or 60% in powdered form and 75% in liquid form.

However, it’s crucial to note that these percentages refer to the concentration of choline chloride, not pure choline, meaning that about 25% of choline chloride consists of chloride, not choline (National Research Council [NRC], 1994). This distinction is important when calculating the nutritional contribution to an animal’s diet.

Risks of excessive chloride: Chloride is an essential ion in the organism, maintaining osmotic balance and supporting enzymatic, nervous, and muscular system functions.

However, excessive chloride intake can result in metabolic disorders such as metabolic acidosis, tibial dyschondroplasia, and ascitic syndrome (Edwards, 1984; May et al., 1986).

Excess chloride can exacerbate these issues when combined with other chloride-rich ingredients such as Lysine HCl and common salt, leading nutritionists to adjust the formulations by using alternatives like sodium bicarbonate or potassium carbonate. These adjustments can increase feed costs.

The acceptable limits for chloride in poultry diets vary, with some authors recommending a maximum of 0.2% to 0.4% chloride, which could easily be exceeded by combining high-chloride ingredients, thereby posing risks to animal health (Leeson and Summers, 2001).

Vitamin stability and premix challenges:

Choline chloride can also affect the stability of other vitamins in animal feed (Whitehead, 2000). Research shows that vitamins A, E, and K3 can lose significant potency when stored in the presence of choline chloride (Singh et al., 2010).

For example, a study found that vitamin activity could drop by 39% to 80% over the course of a year, depending on the type of vitamin and the presence of choline chloride (Robinson and Mack, 1991).

This degradation can be particularly problematic in premixed feed, where consistent vitamin levels are crucial.

To mitigate this, some manufacturers either reduce storage time or include excess vitamins to compensate for the losses, although this can become economically unfeasible.

Another significant issue with choline chloride is its hygroscopic nature. The compound readily absorbs moisture from the environment, which can lead to clumping and a reduction in volume.

This makes it challenging to produce stable premixes and complete feeds, and some manufacturers have stopped using choline chloride to avoid these problems, while others have added inert carriers to improve the flowability of the final product.

While this helps with the manufacturing process, it increases product volume, leading to higher storage and transportation costs (Bastianelli et al., 2004).

Given the limitations and challenges associated with choline chloride, several alternatives have been introduced to replace it or complement its use.

Among these alternatives, soy lecithin, betaines, and polyherbal products are the most notable.

Polyherbal products, which emerged around 20 years ago, are designed to replace choline chloride in animal feed.

These products, often derived from Ayurvedic medicine, typically consist of multiple plant species.

Ayurveda views health in a holistic way, treating the body with medicines

Polyherbals, unlike single-plant supplements, combine various plants to maximize the range of active compounds.

This diversity enhances the overall therapeutic effect while reducing the risk of toxicity due to the lower concentrations of individual active compounds (Tripathi and Mishra, 2007).

phosphatidylcholine (PC) as the main active compound. Phosphatidylcholine is already metabolically active, meaning it bypasses several metabolic steps required for choline chloride to be converted into its active form.

However, the lack of extraction or processing of active compounds means that contaminants (such as pesticides, mycotoxins, and other harmful substances) may be present in these products.

This necessitates stringent quality control during both the cultivation and manufacturing processes to ensure the safety and efficacy of the final product (Hassan et al., 2015).

Typically, these products contain between 0.5% and 3.2% phosphatidylcholine.

Although the concentration might seem low, it is important to note that phosphatidylcholine already plays an active role in energy metabolism, especially in the regulation of lipid utilization.

Phosphatidylcholine stimulates PPARα (Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha), a group of receptors that regulate energy metabolism, including fat oxidation (White et al., 2019).

This activation favors the use of dietary lipids as energy rather than storing them as body fat, which leads to improved weight gain and leaner carcasses. This is particularly beneficial in animal production, where lean meat is often a desired outcome (Casperson et al., 2012).

Another advantage of polyherbal products is that they do not contribute excess chloride to the diet, reducing the risk of chloride-induced metabolic disorders and improving electrolyte balance.

Moreover, these products do not degrade vitamins (Singh et al., 2010) and pigments, unlike choline chloride, allowing longer shelf life and reducing nutrient loss in stored feed (Mehri et al., 2014).

Selecting the right polyherbal product to replace choline chloride requires careful consideration of several factors:

It’s crucial to understand how the polyherbal product works at a biochemical level. Natural products often come with variability in their active compounds, and polyherbals are complex due to their combination of different plant species.

Research into the product’s MOA should be based on scientific evidence, ensuring that the claims made about the product’s effects are valid and reliable (Anwar et al., 2016).

Polyherbal products are also more environmentally friendly, as they are derived from plants rather than petroleum-based choline chloride. Additionally, their costs tend to be more stable and less prone to fluctuations based on petroleum prices, making them a more predictable option for feed formulation (Garg et al., 2018).

The main nutritional functions of choline in animals—acetylcholine synthesis, phospholipid formation, and methyl group donation—are relatively easily met through other dietary components, including methionine, serine, and betaine.

However, choline’s role in energy metabolism through phosphatidylcholine is more complex, and polyherbals that can effectively modulate energy distribution, reduce fat deposition, and improve energy efficiency in animals are highly valuable (Zhang et al., 2014).

A detailed technical file is essential when evaluating polyherbal products.

This file should include data from multiple experiments, ideally performed under various conditions, and backed by objective analyses that assess the product’s performance and efficacy.

It’s also important to consider the reputation and expertise of the institutions conducting these studies.

Given the potential for contamination in plant-based products, an efficient sanitization process is vital to ensure the microbiological safety of polyherbal products.

Common methods include gamma-ray irradiation and the application of organic acids, both of which help control bacterial and fungal contamination without compromising the product’s quality.

Polyherbal products, especially those derived from plants that have not undergone extensive processing, must adhere to strict quality control standards.

Look for certifications such as GMP+ and FAMI-Qs to ensure that the products have been produced in a safe, controlled, and compliant environment.

This also helps to ensure that the product meets legal and safety standards for animal feed (Kumar et al., 2017).

This text focuses from now forward on the evolution and benefits of Natu-B4™, a polyherbal product designed as a choline chloride replacement. First launched in 2003, Natu-B4™ was originally intended to replace pure choline chloride in animal feed.

Over the last 22 years, extensive studies have demonstrated not only its ability to replace choline chloride but also additional health and performance benefits.

The product combines several plants used in Ayurvedic medicine and provides choline in the form of phosphatidylcholine, along with other

Natu-B4™ has undergone more than 100 studies in over 10 species, revealing its optimal application and mechanisms of action.

Initially replacing choline chloride, it has now proven to provide multiple benefits, particularly in improving the bioavailability of nutrients, enhancing fat metabolism, and increasing energy efficiency (Kim et al., 2019).

Natu-B4™ is a non-hygroscopic powder that is stable at high temperatures and resistant to degradation by intestinal microbiota.

This stability allows it to maintain its efficacy in premixes, pelleted, and extruded feeds without affecting other nutrients (Singh et al., 2010).

Studies show that Natu-B4™ causes no vitamin loss compared to choline chloride, even under high-temperature conditions.

Natu-B4™ works by stimulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR-α), which regulate fatty acid metabolism and improve feed conversion (White et al., 2019).

PPAR-α activation enhances energy efficiency and reduces fat accumulation in the liver (Vázquez and Laguna, 2000; Panadero et al., 2008).

Studies have shown that Natu-B4™ supplementation in broiler chickens increases PPAR-α gene expression by 39% compared to choline chloride (White et al., 2019).

Numerous studies across different species have confirmed the benefits of Natu-B4™:

CHICKENS: A bioequivalence study found that 1 kg of Natu-B4™ is equivalent to 4.84 kg of 60% choline chloride, with similar productive yields and reduced liver fat (Farina et al., 2014).

PIGS: Natu-B4™ supplementation led to leaner carcasses with greater muscle depth and improved fatto-protein deposition (Gonzalez et al., 2021).

RUMINANTS: Studies in sheep and dairy cows indicated that Natu-B4™ can replace ruminally protected choline (RPC) products, enhancing milk production, reproductive health, and reducing liver fat (Cañada et al., 2018; Godinez-Cruz et al., 2015).

PETS: Natu-B4™ at the gene level demonstrated properties to prevent cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, cancer prevention, inflammatory and immune response, and behavior and cognitive processes in dogs (Mendoza-Martinez et al., 2022).

Natu-B4™ is FAMI-QS and ISO-certified, ensuring rigorous manufacturing and quality standards.

The product is sanitized for microbiological safety, and all raw materials undergo thorough contaminant monitoring.

It is also approved for use in organic feed (FiBL, 2025).

Polyherbal products stand out as the most comprehensive and cost-effective replacement.

They offer several advantages, including better metabolic outcomes, reduced chloride intake, improved energy efficiency, and reduced risks of contamination and nutrient degradation.

Still using Choline Chloride in animal nutrition? Discover its risks and a superior natural alternative DOWNLOAD ON PDF

With advancements in scientific knowledge and analytical techniques, polyherbal products can now be selected with greater confidence and reliability, making them an increasingly popular choice in animal feed formulations.

When choosing a choline chloride replacement, it is crucial to evaluate both the economic and functional benefits of the product.

Polyherbal products provide a more sustainable and reliable option for animal nutrition, benefiting both the animals’ health and the feed manufacturer’s bottom line.

Celebrating 22 years in 2025, Natu-B4™ remains a leader in herbal alternatives to choline chloride. Nuproxa Switzerland offers extensive application support and after-sales services to ensure optimal usage across Europe.

To learn more about Natu-B4™, contact Nuproxa www.nuproxa.ch

Gerardo Ordaz Ochoa, María Alejandra Pérez Alvarado, Luis Humberto López Hernández

The National Research Center for Animal Physiology and Improvement, INIFAP, Mexico

Fats and oils are essential components in pig diets. They provide energy, essential fatty acids, contribute to the sensory characteristics of feed, and influence meat quality (Chen et al., 2018).

However, when exposed to oxygen, light, and heat, fats can undergo oxidation, leading to changes in their chemical composition, flavor, and nutritional value (NouroozZadeh, 1999). This directly affects the composition of the diet, animal health, productive performance, and product quality.

Since pig nutrition is a critical aspect of swine production from both production and economic perspectives, there has been growing interest in recent years in using oxidized fats as ingredients in pig diets (Chen et al., 2018).

Fat oxidation occurs through a complex series of chemical reactions involving the interaction of unsaturated fatty acids with oxygen molecules.

The process is accelerated by factors such as heat, light, and the presence of catalysts, including metals and enzymes.

Oxygen reacts with the double bonds of unsaturated fatty acids, leading to the formation of lipid hydroperoxides, which further decompose into aldehydes, ketones, and other volatile compounds (Frankel, 1980).

Fat oxidation results in the formation of various chemical compounds:

Hydroperoxides

Aldehydes

Ketones

Free radicals

These compounds can alter the aroma, and nutritional properties fats, leading to unpleasant flavors, rancidity, and a reduced shelf life.

Additionally, oxidation can decrease the nutritional quality of fats by reducing levels of essential fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins (Nourooz-Zadeh, 1999).

The use of oxidized fats in swine diets has been a topic of controversy. The literature includes both positive and negative findings regarding their application:

Reported benefits of oxidized fats in swine feeding include:

Energy source

Oxidized fats can serve as an alternative energy source in pig diets.

Despite the formation of oxidative byproducts, these fats retain a significant portion of their caloric value, providing pigs with energy for growth and maintenance (Gourle et al., 2020).

They can be cost-effective for pig producers, especially when fresh fat sources are expensive or in short supply.

However, incorporating oxidized fats into pig diets might compromise feed nutritional quality due to the chemical changes fats undergo during oxidation.

Oxidized fats, which may not be suitable for human consumption due to unpleasant flavors or rancidity, can be reused as feed ingredients for pigs. This reduces waste in the food industry and contributes to the sustainable use of resources (Gourle et al., 2020).

Risks associated with the use of oxidized fats in pig feeding include:

Oxidized fats may contain reduced levels of fat-soluble vitamins and antioxidants due to the oxidation process.

Pigs fed diets rich in oxidized fats may be at risk of nutrient deficiencies, particularly vitamin E, which plays a critical role in antioxidant defense and immune function (Nguyen et al., 2019).

Palatability and digestibility

Oxidized fats can impart unpleasant flavors and odors to feed, potentially affecting its palatability and consumption by pigs.

Oxidative byproducts can also hinder the digestion and absorption of fats, leading to reduced nutrient utilization and growth performance (Chen et al., 2018).

The consumption of oxidized fats has been linked to adverse health effects in animals, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and compromised immune function.

Pigs fed diets with high levels of oxidized fats may be more susceptible to oxidative damage and metabolic disorders (Jha & Berrocoso, 2016).

Oxidized fats exhibit distinct characteristics resulting from the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids.

The chemical changes during oxidation lead to the formation of volatile compounds that affect the taste, aroma, and nutritional properties of fats.

In swine feeding, the use of oxidized fats presents both opportunities and challenges for pig producers:

They offer a cost-effective energy source and contribute to waste reduction.

However, their inclusion in pig diets requires careful consideration due to their effects on nutritional quality, palatability, digestibility, and health risks.

Understanding the characteristics of oxidized fats is essential for ensuring feed quality and safety and for developing strategies to minimize oxidation-related issues.

The benefits and risks associated with the use of oxidized fats should be carefully balanced, and appropriate quality control measures must be implemented.

It is important to highlight that, regardless of the benefits and implications of using oxidized fats in the swine industry, limits on their inclusion in pig feed should be established to ensure product safety and quality.

Pig producers must comply with these regulations and continuously monitor fat quality to mitigate potential health risks for pigs.

Juan Gabriel Espino, Independent Nutritionist

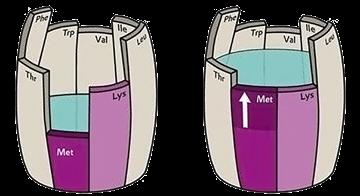

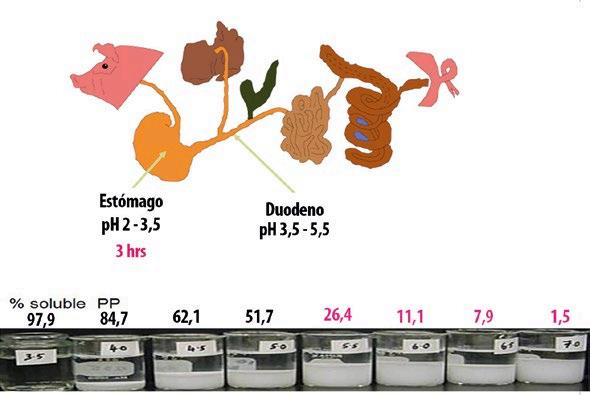

The release of phosphorus from phytate occurs through the sequential cleavage of phosphate groups from the inositol ring. It was believed that, regardless of the properties of phytases, the rate of phytate dephosphorylation is limited by the first cleavage of any phosphate group.

The position of the first phosphate group cleaved depends on the specificity of the phytase. The inhibition of dephosphorylation initiation is not related to the enzyme’s mechanism of action but rather to insufficient phytase activity or low substrate availability.

Non-ruminant animals do not efficiently digest phytate present in feed due to the low presence of endogenous enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT).

Analysis of transformations in the inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) inositol (I) reaction chain shows that the overall dephosphorylation of IP6 limits the removal of the phosphate group from I(1,2,5,6)P4 (the third reaction from the start of phytic acid phosphate bond hydrolysis).

Reduced nutrient availability in the presence of phytate is not due to phytase activity, but rather to phytate phosphorus anions (IP6-3) binding to positively charged metal ions, amino acids, and proteins..

Phytate is a form of phosphorus storage in plant seeds. As a result of phytase activation during seed germination, phytate releases inorganic phosphate (Pi) for use by growing plants.

The term phytate includes various substances defined by the presence of the phytic acid anion (PA).

Enzymes that cleave phytic acid are called myo-inositol hexakisphosphate 3- and 6-phosphohydrolases.

pH is a determining factor affecting the solubility of reaction products. Increasing the pH to 4-5 reduces the solubility of the resulting salts, except for magnesium phytate, which remains soluble at pH 7.5.

In solutions with a pH < 1.1, phytic acid has a neutral charge and remains weakly active. An increase in the pH of the medium to 2 leads to the ionization of three phosphate groups; a further increase in pH results in the loss of the remaining protons.

The phytic phosphorus anion is capable of retaining its negative charge in the gastrointestinal tract and reacting with cations.

In the stomach, lysine, histidine, and arginine, as well as proteins and polypeptides containing these amino acids, can form binary protein-IP6 complexes that inhibit protein digestion.

The binding of phytic acid to positively charged amino acids limits their absorption.

The most common and well-studied are histidine acid phytases, which differ in the carbon atom of the myo-inositol ring from which the first phosphate group is removed.

The subsequent removal of phosphate groups results in the release of phosphorus available for plants and animals and the formation of inositol esters with a lower number of soluble phosphates.

The solubility of isomers depends on the ratio of metal cations and the presence of free amino acids with chelating properties. It is believed that the first three stages of phytic acid dephosphorylation (IP6 IP4) play an important role in creating conditions for the complete hydrolysis of IP.

The negative charge of the phytic acid molecule and its ability to bind to other nutrients decrease as the number of phosphate groups is reduced.

Alkaline phosphatases and alkaline phytases also participate in the cleavage of isomers.

Recently, it has been established that when histidine acid phytase is included in the diet (500 units/ kg - 1000 units/kg), it increases the activity of endogenous alkaline phytase in the jejunum, an enzyme that breaks down insoluble divalent metal phytates.

The action of each type of phytase and its maximum activity depend on the pH of the medium.

On this basis, phytases are classified as acidic or alkaline. Acid phosphatases exhibit broad substrate specificity toward metal-free phytates, while alkaline phosphatases are specific to metal-bound phytic acid.

Figure 1. This figure illustrates the gastrointestinal tract of a pig, showing acidity levels in the stomach and duodenum, as well as the retention time of the food bolus in the stomach. The lower portion displays the in vitro solubility of phytate at different pH values.

The solubility of phytate is 97.9% when immersed in a suspension with an acidity of 3.5. This acidity level is reached when phytate is in the gastric portion of the gastrointestinal tract.

Acid phytases are highly effective in the stomach; therefore, it is essential to promote an adequate retention time of the food bolus. If acidity increases further, phytate precipitation can be observed, appearing as a whitish suspension.

In this test, we can observe that the insoluble state of phytate begins to appear at pH 4. In this protonated state, phytate starts binding minerals (Zn, Cu, Co, Mn), forming an insoluble phytate-mineral complex that is unavailable for absorption.

Proteins can also be affected by improperly solubilized phytate, leading to the formation of an insoluble phytate-mineral-protein complex that is unavailable for absorption by the pig.

Increasing the phytase content in feed to 1500 FTU/kg ensured maximum cleavage of IP6, while a further increase in enzyme content to 3000 FTU/kg had no additional effect on hydrolysis.

in vitro studies conducted with the free substrate (sodium phytate), whose availability was not restricted by the cellular structure of feed components, confirmed that the dephosphorylation of IP4 is the limiting step in the sequential dephosphorylation pathway of the original IP6.

The accumulation of I(1,2,5,6)P4 suggests that its conversion represents a “bottleneck” reaction in the sequential dephosphorylation pathway from IP6 to IP1.

The decrease in the concentration of I(1,2,3,4,6)P5, which retains the phosphate group on the sixth carbon atom in the presence of 6-phytase, indicates that multiple factors may activate alkaline phosphatases and/ or inhibit 6-phytase.

Studies on the metabolite groups of IP6 in pig feces confirmed the assumption that the catabolism of IP6, which occurs as a chain of successive dephosphorylation reactions, slows down at the level of I(1,2,4,6)P4.

Based on various studies, we can conclude that in in vitro experiments, where substrate availability for the enzyme was not restricted, IP6 suffered complete hydrolysis, and its conversion to I(1,2,4,5,6)P5 (i.e., the cleavage of the first phosphate group) was not the limiting step in the sequential dephosphorylation pathway from IP6 IP2. Instead, the process was inhibited at the dephosphorylation stage of I(1,2,5,6) P4.

The cell walls of cereal grains are composed of cellulose and hemicelluloses, primarily arabinoxylans, with small amounts of β-glucans and mannans.

Monogastric animals lack enzymes capable of hydrolyzing these cell wall polysaccharides, which means that part of the intracellular content of cereal cells remains physically inaccessible to phytases.

The addition of carbohydrases to feed facilitates the breakdown of the cell wall and the formation of channels through which water and enzymes can enter the cells, ensuring the digestion of proteins, starch, and phytate.

When cellulase was added to the feed, phosphorus and protein availability increased by 30.4% and 21.8%, respectively.

Due to the activity of exogenous proteases, phosphorus release increased by 15%, while protein release increased by 14.5%.

The size of phytase molecules is sufficient for them to penetrate plant cell walls through natural pores and catalyze the dephosphorylation of phytate inside the cells.

Bacterial phytases typically have smaller molecules than fungal enzymes. This suggests that the higher efficiency of bacterial phytases may be due to their smaller molecular size, which facilitates their access to substrates.

An important factor in phytase activity is the dissolution of phytate, which allows it to spread beyond plant cells and become available for enzymatic action.

In pigs, feed remains in the acidic environment of the stomach for a longer period than in poultry, leading to a higher amount of soluble phytate. This explains why pigs utilize phosphorus more efficiently than poultry.

The incomplete cleavage of phytate from natural feed in vivo can be explained by the limited availability of enzymes for the substrate, with the dephosphorylation of IP4 being the limiting step.

The same pattern was observed under other experimental conditions using phytases from Escherichia coli, Aspergillus niger, and Buttiauxella sp.

Numerous research papers have demonstrated that phytases have an extra-phosphoric effect, increasing the digestibility of proteins and other nutrients.

However, these conclusions were based on a misinterpretation of results from studies on nutrient utilization, where the physiological process of digestion was mistakenly equated with the processes of amino acid absorption and nitrogen metabolism.

The extra-phosphoric effect of phytases is understood as an increase in the availability of nutrients other than phosphorus during digestion, meaning it is a manifestation of an effect not directly related to the biochemical function of phytases.

Phytases cannot directly affect protein digestibility; instead, they increase the availability of already digested amino acids by preventing their binding to phosphates. This occurs as a result of the reduction in phosphate concentration due to its cleavage.

Therefore, the concept of the extra-phosphoric effect of phytases is not entirely accurate, as phytase has only one effect.

Other consequences, although associated with the addition of exogenous phytases to feed, result from their effect on phytate. These effects are indirect and arise due to the reduction in the concentration of reactive IP6-4 anions.

Phytate has a significant impact on piglet nutrition, leading to considerable weight gain losses if it is not efficiently inactivated by phytases.

Piglets have a reduced ability to produce stomach acidity since their diet is primarily based on carbohydrates (lactose). As a result, a substantial amount of insoluble substrate may remain in the gastrointestinal tract.

One strategy to help piglets efficiently solubilize phytate is the application of superdosing phytase.

Superdosing phytase ensures proper phytate solubilization, preventing adverse effects on piglet growth.

Phytate digestion depends on two main factors: the presence of sufficient amounts of phytase and the availability of phytate for enzymatic action

1

The first issue can be addressed by adding adequate amounts of exogenous phytases to the feed in appropriate proportions.

2

The second issue is overcome by improving the overall digestibility of the feed.

3

In specific cases, carbohydrases can be added to the feed, as these enzymes break down cell membranes, facilitating access for hydrolases to the nutrients within the cytoplasm.

The cleavage of the first phosphate group by 3- or 6-phytases leads to the formation of IP metabolites, including I(1,2,4,5,6)P5 and I(1,2,3,4,5)P5. Compared to IP6, these metabolites bind nutrients less efficiently, but I(1,2,4,5,6)P5 forms stronger complexes with proteins than I(1,2,3,4,5)P5.

Additionally, I(1,2,4,5,6)P5 serves as a precursor to I(1,2,5,6)P4, which inhibits the later stages of IP hydrolysis. This supports the preference for 6-phytases. The extra-phosphoric effect of phytases—meaning their impact beyond phosphohydrolase activity—manifests as an increase in the availability of microelements, macroelements, and amino acids.

Phytases do not have proteolytic or amylolytic activity, meaning the common claim in popular literature that phytases enhance protein and starch digestibility is incorrect.

The secrets behind a phytase DOWNLOAD IT IN PDF

M Naeem

Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Poultry Science, Auburn University

Enteritis, particularly necrotic enteritis caused by Clostridium

perfringens, a naturally occurring bacterium in chickens’ guts, is a significant challenge in broiler production.

Under certain conditions, this bacterium multiplies rapidly and releases toxins that damage the intestinal lining, leading to inflammation, necrosis (death of tissue), and severe disruption of gut health leading to substantial economic losses to poultry producers.

The small intestine, particularly the jejunum and ileum, is the primary site of infection and necrosis. The disease has both acute and subclinical forms, each presenting unique challenges for poultry production and management.

Acute Necrotic Enteritis: This is characterized by sudden mortality, often with minimal preceding signs. Mortality rates can be high in severe outbreaks.

Subclinical Necrotic Enteritis: This leads to chronic damage to the gut, resulting in poor growth performance, reduced feed conversion efficiency, and increased susceptibility to other diseases.

Acute Form: Sudden death of affected birds without significant prior symptoms, lethargy, depression, and reduced feed intake may occur before death in some cases.

Subclinical Form: Poor weight gain, wet litter due to increased diarrhoea, reduced feed conversion ratio (FCR).

Effective control requires a multifaceted approach, with nutrition playing a pivotal role.

Below, we explore key nutritional strategies to prevent and manage enteritis, focusing on maintaining gut health and reducing the proliferation of pathogens.

The foundation of controlling enteritis lies in optimizing feed formulation.

Diets should be carefully balanced to reduce substrates that encourage pathogenic bacterial growth.

Excess crude protein, particularly from indigestible sources, can serve as a food source for C. perfringens.

By lowering crude protein levels and supplementing with synthetic amino acids, nutrient digestibility is enhanced, and gut fermentation of undigested protein is minimized.

Similarly, using highly digestible carbohydrates prevents excessive fermentation in the gut, maintaining a stable microbial environment and reducing the risk of dysbiosis (an imbalance in the microorganisms that live in the body, known as the microbiome).

Probiotics, which are beneficial microorganisms, can play a critical role in controlling enteritis by balancing the gut microbiota.

By competing for nutrients and adhesion sites, probiotics such as Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., and Bacillus spp. inhibit the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria.

Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that selectively promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria. Common examples include:

Mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS),

Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS),

Xylo-oligosaccharides (XOS),

Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS),

Beta-glucans

These compounds support gut health by fostering a microbial environment that suppresses pathogens like C. perfringens.

Additionally, they enhance gut barrier integrity and stimulate the immune response. Regular supplementation of probiotics in broiler diets not only improves gut health but also promotes overall performance, making it a cornerstone strategy in enteritis management.

Prebiotics also enhance the gut’s structural integrity by stimulating the production of mucus and short-

4

Enzymes play a vital role in improving nutrient digestibility and reducing the availability of substrates that pathogenic bacteria can utilize.

Enzymes such as xylanase, protease, and phytase break down non-starch polysaccharides, undigested proteins, and phytates, respectively.

This reduces intestinal irritation and minimizes nutrient residues that could fuel bacterial overgrowth.

Incorporating enzymes in broiler diets not only prevents enteritis but also enhances overall feed efficiency and growth performance.

Organic acids are another effective nutritional intervention for controlling enteritis. By lowering the pH of the gastrointestinal tract, organic acids such as formic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid create an unfavourable environment for pathogens.

7

Butyric acid, in particular, has additional benefits as it directly supports gut epithelial health and repair. Regular supplementation of organic acids in feed or water can significantly reduce the risk of enteritis and improve gut functionality.

Essential oils and phytogenics are natural antimicrobial agents that can support gut health. Oregano oil, thyme oil, and garlic extract are well known for their antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. These compounds inhibit the growth of C. perfringens and other harmful microorganisms while promoting a healthy gut microbial balance.

Their inclusion in broiler diets provides a natural and sustainable alternative to traditional antibiotics to control the pathogens’ load.

Dietary fiber, both soluble and insoluble, plays a critical role in maintaining gut health. Insoluble fibers, such as wheat bran and cellulose, promote gut motility and prevent the accumulation of harmful bacteria.

Soluble fibers, like pectin and beet pulp, undergo fermentation to produce short-chain fatty acids that nourish the gut lining and inhibit pathogens.

A balanced inclusion of dietary fiber in broiler diets prevents intestinal dysbiosis and supports overall gut integrity.

Ensuring the hygiene of feed ingredients is crucial in preventing enteritis.

Contaminated feed can introduce pathogens and mycotoxins that compromise gut health.

Using heat-treated feed or pelleting can significantly reduce microbial load.

Proper storage practices, such as keeping feed dry and free from pests, also help minimize contamination. High feed hygiene standards are an essential component of a comprehensive enteritis control strategy.

Immunomodulators, such as beta-glucans and nucleotides, enhance the bird’s natural immune response. Beta-glucans, derived from yeast cell walls, stimulate macrophages and other immune cells, enabling them to combat pathogens effectively.

Nucleotides, which are building blocks of DNA and RNA, support rapid cell turnover and repair in the gut lining.

By strengthening the immune

While each of these strategies is effective individually, their synergistic application yields the best results.

For example, combining probiotics with organic acids and dietary fiber creates a multi-layered defence against enteritis.

It is also important to tailor these strategies to the specific needs of the flock, considering factors such as age, health status, and environmental conditions.

Additionally, routine monitoring of gut health and pathogen load ensures that nutritional interventions remain effective, and adjustments can be made as needed.

Enteritis remains a significant challenge in broiler production, but it can be effectively managed through well-designed nutritional strategies.

By focusing on gut health, nutrient digestibility, and pathogen suppression, poultry producers can reduce the incidence and severity of this condition.

The integration of feed optimization, probiotics, prebiotics, enzymes, organic acids, and other supportive measures ensures a holistic approach to enteritis control.

Combined with strong management practices and regular monitoring, these nutritional interventions not only improve bird health and performance but also enhance the sustainability and profitability of broiler production.

Tanika O’Connor-Dennie, PhD

Managing Director | Consultant Animal

Nutritionist specializing in tropical nutrition

It is easy to romanticize the Caribbean’s climate—until you try to raise livestock in it. For poultry producers, heat stress is not a seasonal inconvenience; it is a yearround opponent.

Unlike temperate regions that experience predictable cycles of summer and winter, we contend with constant high temperatures and humidity. In Jamaica, the two primary rainy seasons—May and October— bring a predictable cascade of issues: reduced average daily gains, gut health challenges, and an increase in flushing requirements.

Added to this is the unique logistical, cultural and regulatory environment that Caribbean poultry producers operate in.

Regulatory frameworks in CARICOM lean towards the European Union model, meaning some antibiotics are not as readily available for commercial animal production, indeed some integrators have even moved to full ABF operations.

To add another layer of complexity, feed ingredients cost over 30% more than in the USA or Brazil. As small players in the global market, we often have little choice but to accept what is available—whether or not it truly meets our needs.

This reality has forced us to be adaptive. We do not have the luxury of trial and error on a grand scale, nor can we afford to wait years for solutions. Instead, we have become early adopters of technologies that, in larger markets, would have been cautiously integrated over time.

Suppliers quickly realized that advanced enzymes, organic minerals, amino acids, pre- and probiotics, and phytogenic compounds would gain traction in the Caribbean—provided they were backed by solid science. These are not mere enhancements; they are essential components of our nutrition strategies.

Rather than being reactionary to heat stress problems the key lies in pre-emptive action, For example before the spring and summer months approach, start making incremental dietary adjustments; adapting diets and management strategies before the challenges arise.

Indeed, because formulation does not happen in a vacuum as nutritionists, we must be aware of the role the physical environment plays. For example, in Jamaica, we have high bauxite soil. Why is this important? Because these soils are high in minerals that act as antagonists to other minerals, making the form of the minerals we use in our diet critical.

Indeed, I usually recommend a combination of inorganic and organic minerals in mineral premixes and as alternatives to antibiotics.

Think of managing heat stress like hosting an unwelcome guest—one that overstays its welcome and refuses to be ignored. But with the right strategies, it becomes less of a battle and more of a carefully orchestrated dance.

Heat stress affects feed intake and digestion, so seasonal tweaks are critical. Electrolytes and organic acids and mineral oils help to control bacterial overgrowth and reduce gut inflammation. Adjusting nutrient density before birds exhibit signs of stress prevents cascading performance losses.

Additionally, the use of ionophore or bioshuttle programme to control coccidiosis that occurs due to the high moisture levels that results from birds flushing due to high water intake.

Imported mineral premixes are not always compatible with our environmental conditions. Water sources in many Caribbean territories, particularly in limestone-rich areas, contain high levels of calcium. This alters mineral availability, requiring careful recalibration of trace mineral ratios to maintain optimal bird performance.

Now, let us dive into another critical issue: mineral selection. The Caribbean’s soils—whether the high bauxite soils of Jamaica or other volcanic types in the region—are unique. They are high in certain minerals like iron and aluminum, which can create antagonisms with essential nutrients such as copper, zinc, and manganese.

The tricky part is that we do not source these minerals locally. Instead, we purchase premixes from companies based in the USA and Europe. These suppliers often use formulas that work well in their own regions, but they do not always account for our soil’s idiosyncrasies.

Because we are a small market, these premix companies tend to impose what works for them, assuming one size fits all. They overlook the fact that our highmineral soils can disrupt the delicate balance of mineral uptake in poultry. For example, high levels of iron in Jamaican soils can reduce copper absorption— essential for haemoglobin formation and enzyme function—while aluminium may interfere with the uptake of calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium.

When premixes are designed without these local factors in mind, our birds can end up with imbalances that hurt their growth and overall health.

This is not just an academic issue. The misalignment between imported mineral mixes and our soil conditions means that onthe-ground adjustments become essential. We often have to finetune the levels of added minerals and sometimes even adjust the Ca:digestible P ratios to counteract the natural antagonists present in our environment. It is a constant balancing act, and one that underscores just how unique our situation is.

Maintaining a proper mineral balance is critical for optimizing poultry health and productivity. Disruptions caused by mineral antagonism can lead to poor growth, compromised immune function, skeletal deformities, reduced egg quality, and metabolic imbalances.

Proper dietary formulation, monitoring mineral interactions, and adjusting supplementation strategies are essential to mitigating these risks and ensuring optimal poultry performance.

Heat stress mitigation is not confined to the feed mill. Lighting schedules, ventilation adjustments, and hydration strategies play a vital role. Hydration is particularly critical—probiotic-enhanced hydration products help maintain gut integrity and mitigate the impact of heat stress.

Former sugarcane fields, for instance, present a challenge due to residual nitrites in the soil. This becomes an issue after heavy rains or when there is a drought and there is a heavy reliance on well or irrigation water heavy in Total Dissolved Solids (TDS).

Knowledge of this possible water contamination means careful water management and the selection of the right water additives that will not encourage bacterial growth in the waterline. It also means water acidification to boost the sanitation power of chlorination and the flushing of waterlines throughout the day.

Nutritional interventions for heat stress must be both science-driven and economically viable. It is tempting to focus on formulation costs alone, but in a vertically integrated system, the goal is not just a better feed conversion ratio (FCR)—it is maximizing revenue per kilogram of meat produced.

While the list of nutrient interventions that have proven effective in reducing the impact of heat stress, here are some strategies have proven effective:

Maintaining water balance is critical in high temperatures. Betaine, in particular, has shown promise in reducing heat-induced dehydration by improving cellular water retention.

Heat stress alters amino acid metabolism, with methionine and arginine playing crucial roles in stress tolerance. Strategic adjustments help maintain immune function and overall resilience.