> query

36 Run This City

Sarah Mawdsley

40 Towards An Engineered-Timber Civic Realm

Kalapoda, Zhang, Hao, and Wu

48 Migratory Spaces in Northern Chile

Sebastián Salas & León Duval

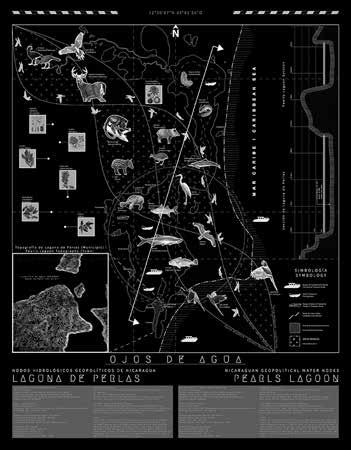

52 Ojos de Agua

Oscar M. Caballero

> query

36 Run This City

Sarah Mawdsley

Kalapoda, Zhang, Hao, and Wu

48 Migratory Spaces in Northern Chile

Sebastián Salas & León Duval

52 Ojos de Agua

Oscar M. Caballero

We are pleased to present to you the Spring 2022 issue of URBAN Magazine: Loading. For this issue, the URBAN editors envisioned the magazine as a vessel for the planning program’s pulse. How are students perceiving the current landscape of planning challenges, and themes? Instead of prescribing themes to our writers, we encouraged our contributors to simply speak.

Our talented writers returned to us diverse pieces, ranging from intimate reflections on the human experiences to essays unpacking informal housing in South America. Interesting, even without a prescribed theme, there is a clear thread that underpins these pieces. GSAPP planners are keenly interested in restoring humanity to planning practices.

As scholars and practitioners of the built environment, pressures mount to default to physical space as the primary measure of progress. Our writers are not as convinced. Aligning actions to our goals of equity, offering space for new perspectives to permeate, and promoting inclusivity must tether us as we look forward.

We know that you will enjoy these pieces as much as we enjoyed putting this issue together.

senior copy editor senior design editor senior publishing editor

POWERFUL

At times even the names of the inhabitants remain the same, and their voices’ accent, and also the features of the faces; but the gods who live beneath names and above places have gone off without a word and outsiders have settled in their place.

pandemic era. Debates have emerged which call into question the purpose of public space, its relationship to the propertied class, and the parameters of the “public” to which urban parks ostensibly serve.

Of the many societal norms smashed to bits during COVID-19’s peak in the summer of 2020, few were of greater interest to local planners, architects, and urban scholars than the dramatic transformation of parks and public spaces in New York City. For it was during the initial onset of COVID-19 that New Yorkers formed deeper, more intimate relationships with the city’s vast and impressive public park system. In the midst of government-imposed lockdowns and “shelter in place” mandates, public parks served as crucial green oases for New Yorkers -- the majority of whom lack backyards, let alone quaint getaway homes in the Hudson Valley or Cape Cod.

As New Yorkers of all backgrounds experienced this glorious reprieve from COVID-era gloom in the city’s parks, an aggressive backlash mounted on both the local and governmental level. With the growth in park usership, generally accepted legal standards about public drinking, noise amplification, and assembly became blurred amidst the rapid change of the

The unquestionable epicenter of public parks controversy in New York City has been Washington Square Park. During the summer of 2020, the storied agora of Greenwich Village, known for its tradition of countercultural protest, music, dance, performance art, and bohemianism, began to bloom with vibrancy as cooped-up New Yorkers flocked to it in droves. But, following the COVID-era influx of young, oftentimes black and brown New Yorkers from distant neighborhoods or the outer boroughs, residents of the park’s affluent, politically-connected surrounding neighborhood of Greenwich Village have worked with the Washington Square Park Conservancy and the NYPD to mitigate such liberated park usage in the name of public safety, health, and “quality-of-life.”

As planners, architects, and designers, such a conflict poses a critical question to all of us: do we plan with park users, or do we plan with those judging them over glasses of prosecco from the lofty stoops of nearby brownstones? (DE FREYTAS-TAMURA, 2021) . In this essay, I argue that given the considerable power of the latter group, it is imperative for us to ask how we can best address, dispel, and condemn the bad faith, politicized narratives used by the powerful to justify the criminalization of park users. Furthermore, I posit that such a concentrated attack on park users is, in effect, an attack on the foundational ideals of public space. Specifically, I argue that the belief that

interclass contact is a vital necessity for a functioning city, and that spaces which permit such contact should be democratically cultivated rather than micro-managed, surveilled, and policed by a handful of wealthy donors or nearby property owners.

New Yorkers have always cherished their local parks, but the COVID-19 pandemic redefined this storied relationship in a profound fashion. Parks became at once refuges from the mind-numbing monotony and loneliness of quarantine, rare spaces in which contact with others was permitted (albeit at a distance), and eventually, even rarer places in which people could experience collective joy during an unremittingly bleak moment in history.

Amid the otherwise harrowing memories I have of this era, I fondly recall being invigorated at the site of smiley, wellattended jazz concerts at the Prospect Park boathouse; cricket matches in the sprawling, tree-lined oval of Marine Park, the precious emerald pendant of southern Brooklyn; elegantly synchronized tai-chi courses in Seward Park on the Lower East Side – “the first permanent, municipally-built playground” in the United States (NYC Parks); and bustling basketball games on the courts of Riverside Park. While such activities were not uncommon prior to COVID-19, each of them seemed to have an added level of intensity and significance, as if New Yorkers were suddenly cherishing the social and physical connections that they had once taken for granted.

Nowhere was this energy more concentrated than at Washington Square Park. Prior to summer 2020, my mental image of the Square was one of the park at sundown, when it begins to look like a gorgeous mosaic of life as people pour in from all sides to play in the fountain, listen to local jazz quartets, read novels in the green spaces, line up for pondicherry dosas from Thiru Kumar’s legendary dosa cart, attempt skate tricks

on the base of the Garibaldi statue, and watch legendary street performers Tic and Tac do their act for naive and unsuspecting tourists. Particularly wonderful is that Gogurt purple azure that envelopes the park’s generous slice of sky before sundown.

That summer, it wasn’t that the park had been reinvented, but rather, it had been re-appreciated. The liveliness, color, and cacophony of noises continued, but in an exaggerated and exciting new format. There were simply more kids, more musicians, more performers, and a generally more palpable sense of mirth amongst all of them. Atop some of the most valuable land in the western hemisphere, young people from uptown, Queens, Brooklyn, and The Bronx had found an oasis of freedom in which they could reclaim their youth from the jaws of COVID (DE FREYTAS-TAMURA, 2021) .

From my early teenage hajjes to Greenwich Village, to my time as an undergraduate at a small college in the area, I’ve always admired how Washington Square Park acts as a highly accessible node of youth culture, transgression, and public expression amidst an aging, increasingly sterile neighborhood / NORC (Naturally Occurring Retirement Community). Much like its countercultural younger sibling of Berkeley, California, the rebellious, experimental environment that gave Greenwich Village its outsized reputation has gradually been reduced to a nostalgia brand, as successive waves of hypergentrification have rendered the neighborhood prohibitively expensive for all but the extraordinarily wealthy.

Yet, never before the summer of 2020 was this dynamic so crystalized, with the park emerging as a stage upon which the Lefebvrian right to the city was contested in a pitched battle between the city’s haves and have-nots. For, as we

learned during the Battle of Washington Square, it is amid the smothered, physically-but-not-spiritually preserved landscape of today’s hyper-gentrified Greenwich Village that Washington Square Park gains its true power and significance.

As is almost inevitable with any great change, particularly in a city as conservative (with a little “c”) as New York can be, there was vocal opposition. Citing concerns of drug use, trash, loud music, and “bizarre behavior,” residents of the Village - median household income: $164,860, more than twice the citywide average of $70,590 - began to voice their opposition to the new uses of the park (FURMAN CENTER, 2019) . Then, as wealthy white urbanites often do when they deem the use of public space improper, they called the police.

On November 7th, following a Black Lives Matter march and a celebration of Donald Trump’s defeat in the presidential election, the NYPD conducted a rare, militaristic curfew raid at Washington Square Park. Clad in riot gear, over 50 officers charged after park goers, swinging batons (including at a 19 year-old girl) and arresting a 23 year-old and a 25 year-old (OFFENHARTZ, 2020) . This raid would quickly prove to be the new normal, as the NYPD began conducting similar raids with increased frequency in the following months.

With the increased frequency of public demonstrations during the “George Floyd Rebellion,” combined with the massive uptick in park usage during this time, the NYPD perceived a blurring of the line between “public assembly” and “protest,” and took full advantage of this politically manufactured ambiguity to justify harsher, more brutal crackdowns. Sensing the increased media attention paid to issues of public safety, it was as if the NYPD chose Washington Square Park as the primary political theater in which it would publicly regain dominance over the

rowdy, newly liberated, and dissenting populace.

In one particularly loathsome instance of NYPD aggression, NYPD officers encircled and then brutally arrested several park-users in Washington Square during the June 2021 Queer Liberation March, a staple of the city’s yearly Pride celebrations. After surrounding the park with barricades and blasting warnings of unlawful assembly on their sound cannons, officers in riot gear menaced Pride attendees with their bikes and batons, ordering them to leave the park once the clock struck midnight. Eight attendees were arrested, and several were pepper-sprayed (YURCABA, 2021) . Given the obvious fact that NYC Pride began just blocks away at the Stonewall Inn in 1969, as queer people took up bricks against cops in a riotous, revolutionary protest of brutal, homophobic crackdowns on gay bars, the political implications of this onslaught are infuriatingly clear.

Tellingly, just eleven days before breaking up the Pride celebration, the NYPD held an emergency meeting in a nearby Greenwich Village church basement, asking community members to address their grievances about the supposed chaos in Washington Square, and express their thoughts about a new 10 p.m. curfew for the park. Though the town hall was advertised as public, hundreds of people on line were denied access. Gothamist reporter Jake Offenhartz, present at the meeting, noted the overwhelmingly old and white character of the attendees, also writing that “the majority of those who showed up to oppose the curfew were barred from entering because of capacity restrictions” (OFFENHARTZ, 2021) .

According to Dean Moses, a reporter for the local neighborhood news website The Villager, “most of the attendees inside were

older folk, while their more younger counterparts were left standing outside chanting ‘Let us in!’” (MOSES, 2021) .

Several sources, including The New York Times, corroborate the observation that this meeting highlighted the race, class, and age dynamics at play in the struggle over Washington Square Park (OFFENHARTZ, 2021; DE FREYTAS-TAMURA, 2021) . Gothamist even reported that, with some exceptions, older, white, more affluent Villagers overwhelmingly advocated for increased police presence.

One such man advocated for the confiscation of park users’ skateboards, adding “it will not be that traumatic for the snowflakes” (OFFENHARTZ, 2021) . Responding to a homeless man who complained of being brutalized by the NYPD in the park, and of the disproportionately white makeup of the meeting, a 59 year-old Union Square resident retorted by saying “The community was invited for a community meeting. He’s not part of the community. He’s a visitor to the park” (OFFENHARTZ, 2021) .

The question of which people constituted “members of the community” remained a thorny topic of debate throughout the town hall. When a 21-year-old street musician claimed that the NYPD had incited violence with their aggressive approach in Washington Square, he was booed and asked to finish his remarks in a noticeably shorter amount of time than other attendees. Speaking to the pro-curfew crowd, Manhattan Borough Parks Commissioner William Castro insisted “We are returning your park to you, local residents” (ROSNER & GARGNER, 2021) .

attendees – overwhelmingly black and brown people in their teens and early twenties – attested to the horrific police violence they had witnessed during the crackdowns in the park.

Following the town hall, this younger, outdoor contingent approached the exiting attendees and loudly made their claims to Washington Square. Now outside on a public street, outnumbered by the youths and unprotected by the police, the Villagers had to answer for themselves in the face of direct confrontation on a significantly more level playing field. Arguing against the tough-on-crime approach advocated during the meeting, Desmond Marrero, a 25-year-old Washington Square Park regular, spoke of the miraculous assemblages of life which recent events had permitted there. “I see gangstas and white people, the LGBT community and people dressed in suits all coming together and celebrating life,” said Marrero. “We don’t see that on the regular. The park just needs some understanding.” █

DE FREYTAS-TAMURA, K. (2021, June 18). Whose Park Is It? Residents and Revelers Clash Over Washington Square. The New York Times. History of playgrounds in Parks. NYC Parks. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/playgrounds

MOSES, D. (2021, June 17). Whose park is it anyway? inside the Washington Square Showdown pitting the young against the restless. amNewYork.

OFFENHARTZ, J. (2020, November 7). NYPD clears Washington Square Park with clubs and arrests during rare curfew sweep. Gothamist.

Outside, the significantly younger, significantly less white anti-curfew groups elected to conduct a counter-meeting on the sidewalk. Though the NYPD reportedly erected a barrier fence around this small, DIY gathering, its

OFFENHARTZ, J. (2021, June 17). West Village residents, NYPD call for permanent curfew in Washington Square Park. Gothamist.

ROSNER, E., & GARGER, K. (2021, June 16). Hundreds pack emergency meeting to address Washington Square Park chaos. New York Post.

My fondest memory of Beijing comes from the winter when I was sixteen, when my friend and I skated along the banks of Houhai, a lake to the north of the Forbidden City. I remember feeling the wind on my face with a sweet scent of sugar roasted chestnuts, rows of clay tile roofs flashing by like a wave as we skated through the gray, smoggy air of Beijing, listening to songs from jazz musicians melting into conversations from people fishing by the lake. Back then, it felt like home.

Houhai was once a flourishing dock in the Yuan Dynasty in the Thirteenth Century, where Jing-Hang Grand Canal met the commercial center of Khanbaliq, the then city of Beijing. After the fall of Imperial China, civilians populated the area and established residences and stores. In the early 2010s, it was buzzing with jazz bars, small cafes, and family-run shops. The neighborhood was known for the Siheyuans and Hutongs— traditional courtyard residences and the narrow alleys that connect them. We would skate through these seven-hundredyear-old streets, greeting the grandpa who sold candied hawberries by the alley entrance, stopping to pet the Labrador by the coffee shop with our favorite pastries and chat about our latest obsession with books with the owner, an avid reader. Finally, we would turn into a tiny restaurant in Xiao Ju’er Hutong, snuggling into the aroma of freshly fried Japanese croquettes. The owner would greet us with enthusiasm and recount his latest exploration in making delicious potato dishes.

Then I started college in the U.S.. One winter, upon returning home, I found those beloved shops all bricked up. I was only told later that many shops in the Hutongs had to close due to a city-wide planning effort for historic preservation—or rather, an organized city beautification movement to clean up the “Holes in the Wall.” The term referred to the converted storefronts along the walls in residences of Hutongs: built in the 80s and 90s, they were first allowed to encourage dislocated workers to establish their own small businesses in the city. Once bringing the neighborhood vibrance and economic vitality, they were now deemed “unauthorized structures” due to nonconforming use, undesirable aesthetics, and “safety hazards.”

Many shop owners — mostly migrant workers — had to leave the city as a result. As I stood in the once lively alley, facing a gray, solid, and utterly lifeless wall, I asked myself, for whom was the history preserved?

The question lingered in my mind as I worked on a preservation project after graduation during my internship in Beijing last year, where I surveyed historic courtyards to map existing conditions for later planning purposes. Some of these courtyards were first built in the 1600s for royal and noble families. However, their structures and residents have since changed: civilians moved into these royal residences after the Cultural Revolution, and

the 1976 Tangshan earthquake destroyed much of their original architecture. Today, these courtyards have been listed for historic preservation.

I feared that this “historical preservation” might become another project like the clearance of the “Holes in the Walls.” Perhaps the structures in these courtyards were indeed dilapidated, but the residents treated me with kindness: they showed me around the courtyards patiently to help me get all the information and measurements. A lady was even kind enough to give me her mosquito repellent seeing all the bites I was getting. However, when a school mom anxiously asked me what would happen to their self-built home, and when a teacher asked me when the government’s move-out notice would arrive, I could not give them a definitive answer. I wish I could assure them that there will be better housing and service planned for them, that their needs will be attended to, but I was not supposed to tell them anything more than that their courtyards were listed for preservation, and that I was just someone sent by the officials to survey the sites. Historic preservation for these residents meant clearance and relocation—having to leave the place they called home and separate from the communities they connected with for many generations. In preserving and restoring the city’s history, the histories of these people had to be moved elsewhere, but aren’t they also part of the history of this city?

Last winter, I once again set foot on the banks of Houhai, bringing my camera and hoping to capture some remnants of my fondest memory. Instead, I found a fully developed tourist district: franchise stores of cultural artifacts and milk tea chains, so organized as if pasted directly from another historical street redevelopment. The architectural features were so exquisitely restored that every storefront looked picture-ready and Instagrammable. The neighborhood was still more or less the way I remembered, but something had changed fundamentally: I didn’t know the people anymore.

I remember being waved away by a resident that day and her saying that there was nothing worth photographing here. It was an alienating experience from a place to which I was so deeply connected. The historic charm somehow felt commodified, the trust between its residents and visitors eroded and the bond between shop owners and customers destroyed.

For whom should history be preserved? I brought this question along with me as I began studying urban planning. As planners we often face the difficult decision of what to keep and what to forego, influencing the way history is preserved and written. And why is this important? I keep thinking about how I felt at home in Houhai, and what was so precious and nostalgic about it: it was the real human connection I formed with the people in my city. Houhai’s informality once allowed different layers of

history to coexist, so as a teen, I was able to make friends with people in different social groups in the city and listen to their stories. When the policy came about clearing the “Holes in the Walls,” I was thinking about these people I knew and how their lives would be impacted. When the City took away their history after the redevelopment, the human connection was lost, and my connection to the neighborhood was lost as well.

History is a collective narrative but at the same time a unique set of personal tales. In preserving diverse layers of history, we open channels on an individual level for spontaneous conversations to happen across different social groups, and in turn, foster understanding between them. Many challenges we face in planning today result from decades of barriers, assumptions and stereotypes which then fueled misunderstandings, resentments and fears between different groups. However, if we can be conscious about for whom we preserve the histories and be deliberate about creating opportunities for people to genuinely connect with others, we might be able to slowly break down these barriers, find the common grounds, and bridge the chasm between different groups. When more individuals in our society are seeing the perspectives of others, we can then build communities based on listening, understanding, and trust. I believe that the power of planning lies in the human connection in the encounters of our everyday life, which can then change our society profoundly. █

DOING THE JUSTICE OF THROUGH THE EFFORTS PROTECT THEIR CULTURAL THE WESTERN WORLD COULD

ULTIMATE GOAL OF THIS THE PURPOSE OF THESE HINDERED BY THE WESTERN

TO ORGANIZE AND CULTURAL "STYLE" FROM COULD HAVE BEEN THE THIS TEXT, HOWEVER, THESE TWO TEXTS IS WESTERN POWER. _

In this history of architecture, the use of “style” for the categorization of cultural buildings has often been misrepresented and inadequately appropriated by western scholars including orientalists. However, an effort to represent one’s own ethnic “style” or “stylizing” a cultural architecture as one the dependences of the culture could be impossible to be entirely free from the influence of Western domination power on the scholarship of the architectural establishment. (SAID, 1987) It could be interpreted as various definitions such as orientalism, just as the influence varies in degree on the work throughout history. This provocation will be illustrated through two exemplary texts Essays on the architecture of Hindus by Ram Raz and Pictorial history of Chinese architecture: a study of the development of its structural system and the evolution of its type by Liang Sicheng. These two texts are paragons of establishing an architectural style of a specific ethnicity in this case Hindu Indians and Chinese mainlanders by authors who have a part in the society.

The obvious fact is that both of the books are written in English by an author who originally speaks Indian and Chinese. This cooperative action to prove and establish their cultural “style” in English for the Western Scholarly work is an already underlying submission to western dominance in scholarship and western points of view – therefore could be inferred as an act of orientalism from the author themselves. Some could argue that Raz and Liang were rather guarding their own culture against misrepresentation by western scholars through their written

work to introduce the “style” from one who understands the culture. However, this requirement of needing to prove their existence to the western world and needing acknowledgments from western scholar society is already working on the playing field of influence. Only by presenting a book in English, the acceptable form of scholar organization, to a database of western scholarship, Raz and Liang was able to establish/guard their cultural architectural style and get global acknowledgment. This goes hand-in-hand with what Edward Said discusses in his book Orientalism, how baseline assumption that the western world is the only center of the world and the platform of the mainstream; and that if it doesn’t exist in there, it is not recognizable. The mere fact that the two texts are written in English contains a layer of orientalist influence.

Doing the justice of their culture through the efforts to organize and protect their cultural “style” from the western world could have been the ultimate goal of this text, however, the purpose of these two texts is hindered by the western power. Essays on the architecture of Hindus was originally initiated by the British Royal Asiatic Society by Richard Clarke suggesting Raz seen in the preface of the book “…, Richard Clarke, Esq., for the accomplishment of this important and desirable object”. (RAZ, 1834) Not only being published through the British colonial publishing house, but the fact that this publication was suggested by the imperialist to the Raz is also evidence for the insertion of western influence on the body of his text. Although it could be proven that Raz had enough knowledge

on Hindu Architecture to be appointed because he had published “History of the architecture of the Hindoos”, the request to write a book to establish the “style” is an important one. (DRIVER, 2010) Figure 1 is an exemplary page in the books, where there is no trace of Indian language, but rather represented, as Raz referred it as to, “in the well-known language of Europe”. (RAZ, 1834)

Although the book A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture was published by MIT, an American Scholarship, Liang, as shown in figure 2, unapologetically included Chinese characters and names along with his representation – perhaps China not being colonized by Great Britain was a large reason, and it could also be that 150 years in between the work of Raz and Liang, there was a body of work by Edward Said on Orientalism. (DRIVER, 2010) However, if you consider the purpose of this Liang’s text closely, once again couldn’t completely remove the influence of the western colonial power. An article called the Sixth century in east Asian architecture states the motives of Liang’s work:

In China, the most famous architectural historian of that period, Lian Liang (1901-1972), also fit into this mold but with a different agenda. Western trained at a time when Banister Fletcher’s and James Fergusson’s textbooks offered students models of how a class tradition disseminated, Liang’s canon selected buildings from China and Japan that could be incorporated in to a framework of eminent structures designed for China’s imperial

or elite patterns. Thereby, Liang could present China as the point of origin of a classic tradition that diffused to Japan, just as Greek classicism had been the source of ancient Roman art.

(STEINHARDT, 2011)This desire to be the colonial power among East Asian countries through preemption of Asian “style” is based on the previous western colonialization of the east. Learned to think that one nation could hold “superior” power among, it is an imitation of the previous orientalist point of view once held by western power. (SAID, 1987)

It is inevitable that both of them are Indian and Chinese attempting to claim their cultural “style”, however it shells not be overlooked that both of them have so strong ties with the West that they are extremely used to the western world view of their own culture from their exposure more than layman in their culture. They both received heavy western education substantiated by their published work in fluent English and heavy connection with western elites or scholars. Raz on this scholarly work on architecture, he was a judge during the time of English colonization in India. Liang, a Yale-educated, goes on to bring modernistic (westernized) architectural pedagogue to China and later founded a school of architecture at Tsinghua University. Seeing both of their legacies, it is hard to say that they were "commoners." If placing them along with people from their nation on a spectrum scaling from traditional to westernized, there is no doubt that they will be skewed to one

extreme, westernized position. Two authors serve as almost a figure of westernized symbol in their community. With such exposure and constant relation, they could acquire existing undertone in their society of western environment. This bias occasionally shows in the introduction of the text when they make it clear that the text establishing their ethnic “style” cannot possibly capture every style that their cultures have. This statement can be understood as a more than realistic caveat that they cannot possibly capture every single cultural style of their nation, but also the caveat to discuss the truth that it is impossible to be fully free from the western influence as them being this medium representing their cultural style.

Although it does not diminish their effort to be a representative and guardian of their cultural architectural “style”, it should be recognized that there is the unremovable layer of westernized bias on their effort. In the two texts, the authors establish and claim their own cultural architecture to western scholarship. The various evidence discussed shows how it is impossible to be truly free from the influence of western dominance. Even this mere act of writing an essay on this topic might be a cooperative provocation to the influence of Western dominance and power on the scholarship of the architectural establishment. █

DRIVER, F. AND ASHMORE, S., 2010. "The Mobile Museum: Collecting and Circulating Indian Textiles in Victorian Britain," Indiana University Press,52(3),/pp.353-385.

LIANG, S. AND FAIRBANK, W., 1984. A pictorial history of Chinese architecture. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

RAZ, R., 1834. Essays on the , architecture of the Hindus. London: Oriental Translation Fund.

SAID, E., 1987. Orientalism. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

STEINHARDT, N., 2011. "The Sixth Century in East Asian Architecture," Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan, 41, pp.27-71.

EVEN THIS MERE ACT OF WRITING AN ESSAY ON THIS TOPIC MIGHT BE A COOPERATIVE PROVOCATION TO THE INFLUENCE OF WESTERN DOMINANCE AND POWER ON THE SCHOLARSHIP OF THE ARCHITECTURAL ESTABLISHMENT. _

LOW-INCOME OR WORKING-CLASS OF COLOR? HOW MANY COME

ROCKAWAY (QUEENS), MOTT

HARLEM, OR BROWNSVILLE

SIDE CHICAGO? WHAT ABOUT HOW MANY LIVED IN NYCHA

HOUSING OR HAVE FRIENDS THAT LIVE THERE?_

MOTT HAVEN (BRONX), BROWNSVILLE (BROOKLYN)? SOUTH ABOUT SOUTH LA?

NYCHA PUBLIC FRIENDS OR FAMILY

Matthew Shore | M.S.UP

Matthew Shore | M.S.UP

How many are undocumented?

How many have to work part-time jobs to pay rent while going to school because their families can’t afford to help them cover those expenses?

Similar questions should be asked of the faculty at this school.

How many faculty members come from disadvantaged communities of color?

How many have embedded relationships with communities of color in the City or elsewhere?

How many current Columbia GSAPP and Urban Planning students come from low-income or working-class communities of color?

How many come from Far Rockaway (Queens), Mott Haven (Bronx), Harlem, or Brownsville (Brooklyn)? South Side Chicago?

What about South LA?

How many lived in NYCHA public housing or have friends or family that live there?

How many went to inner-city public schools? How many had free lunches and metal detectors at their schools? SNAP?

Who has worked with community-based organizations that have been advocates for equity in disadvantaged communities of color?

In a program that, fortunately, goes to great lengths to critically think about planning, it’s surprising how complacent the program has been in regards to how our faculty members are not critically assessed. One faculty member admitted to not making equity a priority when creating and establishing a citywide sustainability plan for a mayor that held office for nearly twelve years. Another willingly used a loophole to bypass standard community input processes in order to expeditiously redevelop and gentrify a boulevard in a predominantly Black,

low-income community. The list goes on. Yet, we are committed to equitable urban planning!

As an Afro-Latinx student from the City who does not come from wealth, privilege or affluence, take it from me: GSAPP has not done its part to truly strive towards equity and raise underrepresented voices in urban planning and is, in fact, a major part of the problems we see in a city planning world that continues to be dictated by White people, rich people and highly educated yet ignorant people who do not truly understand or represent disadvantaged communities.

such work, therein lies the problem and the legacy you’ve established, GSAPP.

The audacity to talk about vulnerable urban communities in Ivory Towers when the near entirety of your students or faculty members don’t come from such places!

GSAPP must be very intentional about the faculty members it hires and of the ways in which its curriculum, workshops — EVERYTHING is designed.

Community engagement workshops should be administered by people with years of experience working in disadvantaged communities of color. Syllabi must be vetted rigorously to ensure that we’re not being subjected to the perspectives of mostly White, privileged, cisgender men and women. Social justice-oriented courses should, ideally, be taught by people of color who’ve made many years of genuinely positive planningrelated contributions for communities of color and who have lived experiences on matters pertaining to housing injustice, environmental racism, transportation inequity, etc. Despite multiple students and myself raising concerns about these issues to UP faculty, nothing has changed in a meaningful way and the same unacceptable excuses are repeatedly fed to us.

Networking events should be opportunities to uplift the work of practitioners of color working in communities of color with great need. If you don’t have a lot of alumni of color doing

The solutions are not easy and require meaningful coordination, but our self-acclaimed progressive school can and must take drastic action. Rest assured, until GSAPP and each of its academic degree programs, such as the MSUP program, reaches a day where at least 50% of its students are lowincome or working-class BIPOC students from disadvantaged communities of color then it is committing a major disservice to our cities and built environs.

GSAPP and the MSUP program must be proactive to the highest degree with recruiting low-income students of color. Recruit from CUNY and SUNY schools, Rutgers, UC schools and other public universities nationwide. Recruit from HBCUs. Establish pipeline BA or BS/MS programs with HBCUs and public universities for low-income BIPOC students who are studying the likes of urban studies/affairs, public policy, political science, anthropology, sociology, architecture, urban planning, environmental studies, etc.

Look around… Will this continue to be an endless cycle year after year?

Planning programs across this nation must ask this fundamental question.

NO OTHER TIME WOULD ON FDR OR DOWN FLATBUSH UP TO THE MANHATTAN BEING RELEGATED TO SIDEWALKS. WHAT IF IT DIDN'T TAKE INTERNATIONALLY KNOWN TO HAVE THIS EXPERIENCE?

TAKE AN KNOWN HALF MARATHON EXPERIENCE? _

I was running up FDR, the world was silent except for the sounds of hundreds of running shoes on the asphalt and heavy breathing. Running up the exit ramp onto 42nd Street everything changed. Suddenly I was running on one of the city’s most traversed streets, a street I would otherwise avoid even being on the sidewalk on. The crowd built as I put the UN behind me, growing as I passed Grand Central and the New York Public Library, decked out with homemade posters and cow bells. I am directed to Times Square where the crowds cheer for the runners so loud that I can hardly hear myself struggling for breath, but then it dawns on me, I’m running through Times Square. It seems so surreal, how many other opportunities exist to run through there besides the New York City Half Marathon? My time in Times Square however is limited; less than two miles to the finish now, so it's time to start racing. Up I go into Central Park for the finish, onto a road I’ve come to know well from training.

Running has given me the opportunity to connect with New York in a way that would not otherwise be possible. When I moved to West Harlem almost two years ago I had not only secured my first NYC apartment with a great Covid deal, but also gained access to some of the best running routes in the city. To the South, there was Central Park, which I could easily access without having to stop every block by running through Morningside Park. To the West, I could access Riverside Park and the Hudson River Bike Path, which extends all the way

down to the tip of Manhattan and all the way up to Canada. I could run for miles and miles without having to interact with cars for much more than a single block.

Running hasn’t always been this ideal though. Growing up I lived in a town without sidewalks, most of my runs were on the shoulder of roads where drivers flew by without much concern for pedestrians or cyclists that might be just around the bend. Not much was different when I went off to college either. My cross country and track teams would run from school almost everyday into town, dodging cars and dealing with complaints from drivers that we were being an obstruction. But it was worth it. By the end of my first season running at Roger Williams I knew the town like the back of my hand. I knew the road names and how to get anywhere. I’d seen the bay at sunset and sunrise, my campus grew beyond the rec center and the library. I got to see a part of Bristol that none of my classmates ever did.

In 2018 I moved to Berlin for the summer and for the first time I had to do my runs in a city. I was terrified. If it was so unsafe to run on the roads in small New England towns, how would it feel to run in Germany’s capital city? I started running in the morning to avoid people on the sidewalk and cars in the street. In the 30 minutes to an hour before the rest of the city woke up, the streets were mine to do with what I wanted. I would run by bakeries opening their doors and getting a whiff of the day’s fresh pastries. Other runners would go by and wave. Despite

never saying more than a hello to them in passing, they had become my community. Like when I first moved to Rhode Island, running gave me the opportunity to quickly explore and discover parts of my neighborhood I never would have been able to reach just by walking.

As running in cities became an exciting endeavor, I added specific runs to my bucket list. In July of 2018 I woke up before the sun, put on my running shoes, and made my way to the Eiffel Tower so that I could run around it as the sun rose. Unfortunately, the day was overcast so the views were underwhelming, but on the way there from my hostel I passed places I didn’t even know existed. When I was in college I would urge my cross country coach to let us do an international trip like some of the other teams did. He asked me, “but where would we go?” The thing is though, we could go anywhere. Running requires nothing more than a good pair of shoes and somewhere to go.

After I graduated and was no longer required to attend 5pm practice everyday, I took up running in the morning. I moved to New York a few months into the pandemic. People were still wary of public transit and it seemed like everyone had taken up running or cycling simply as a way to leave their apartment for just a little bit. My favorite runs were the ones where I could completely avoid cars and just be with other runners, but getting to run through the streets of New York without a car in sight was my absolute favorite. No other time would you be able to run on

FDR or down Flatbush Avenue right up to the Manhattan Bridge without being relegated to narrow and crowded sidewalks.

What if it didn’t take an internationally known half marathon to have this experience? What if this was possible every day?

Regularly the city shuts down city streets for races that last for hours. And the pandemic has shown New Yorkers that they don’t need to give their precious space over to cars. Over the past two years the City has created miles of open streets, which people love to run and bike along, but they’re ad hoc and few and far between. The city needs networks. Open streets need to not just be in every neighborhood, they need to connect every neighborhood. Imagine hundreds of miles of car free streets for uninterrupted runs, bicycle rides, and programming. Less cars on our streets are better for everyone, it makes them safer, makes them healthier, and emits less emissions.

I love running in cities because it allows me to explore where I live, helps me build a sense of community, but I won’t live in West Harlem forever. If people don’t have access to parks and paths they’re not as likely to go for a run, because they don’t feel safe near cars, or they’re frustrated by stopping each block to let cars go. We give people back their streets though, and everything changes. █

THE IMPORTANCE OF VIBRANT SYSTEMS AND THE NEED INTEGRATION IN OUR IN ORDER TO LIVE, WORK OUR PHYSICAL, EMOTIONAL WELL-BEING ARE HIGHLIGHTED ONGOING COVID-19 HEALTH ESPECIALLY FOR COMMUNITIES ACCESS TO ADEQUATE

BY THE HEALTH CRISIS, COMMUNITIES THAT LACK RESOURCES. _

Eleni Stefania Kalapoda | M.S.AUD '20

Menghan Zhang | M.S.AUD '20

Tian Hao | M.S.AUD '20

Kuan-I Wu | M.S.AUD '20

Menghan Zhang (Meng), Eleni Stefania Kalapoda, Tian Hao, and Kuan-I Wu (Max) were students of the 2019-2020 M. Sc. In Architecture & Urban Design Program (GSAPP). Their collaboration is driven by a people-first approach, tailored to the diverse eco-social and economic urban contexts, ecologically restorative, and flexible to adapt to long-term future growth. They are currently practicing architectural and urban design and research in both the United States and Asia.

Global health pandemics or other environmental and socio-economic pressures are likely to become recurrent urban concerns due to the continuing repercussions, such as biodiversity loss, climate change and wildlife habitat fragmentation on the urban-rural interface, that the augmenting human population and the unsustainable global urban expansion pose to the ecological systems that sustain our life and support our well-being.

The importance of vibrant ecological systems and the need for their integration in our everyday planning (for instance more green balconies, park networks and linked outdoor green public spaces in both our shared urban settings and private

domestic spaces) in order to live, work and sustain our physical, emotional and economic well-being are highlighted by the ongoing COVID-19 health crisis, especially for communities that lack access to adequate resources.

Acknowledging the connection between COVID-19 cases and poorer communities, as well as the historic systemic environmental health inequities of low-income and Black neighborhoods that lack access to green spaces, this proposal harnesses the potential of urban forestry to a more central place in post-pandemic urban life and city structure.

The project mitigates the environmental and socio-economic pressures that a disruptive event, like a pandemic, poses on the urban setting and its inhabitants through transforming marginalized and vacant land into public amenities to immediately support the community’s health and wellbeing in times of crisis. It simultaneously keeps the economy alive by placing shared forest-plant based economic strategies in the spotlight as the main drivers for low-impact environmental growth, self-sufficiency, access to resources or goods that are otherwise scarce in times of crisis.

More specifically, the project aims to repurpose 2,000 acres of underperforming and marginalized land for shared timber farming in order to enact a more adequate synergistic relationship (socio-economically and environmentally) between the built space and the fragmented Hudson Valley’s forest.

2,000 ACRES OF UNDERPERFORMING AND MARGINALIZED LAND FOR SHARED TIMBER FARMING IN ORDER TO ENACT A MORE ADEQUATE SYNERGISTIC RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE BUILT SPACE AND THE FRAGMENTED HUDSON VALLEY'S FOREST._

In Hudson Valley, most of the trees are privately owned, growing on land at the fringe of urban development. Hudson Valley’s Wildland Urban Intermix land is currently underperforming environmentally and economically. It demonstrates the typical, unsustainable conditions present in contemporary rural American towns - large-scale, impervious surfaces that fragment the regional forest corridors, defunct industrial, commercial and transportation infrastructure demand innovative schemes for sustainable vegetative strategies and green infrastructure, as well as hyperactive development potential on the near future that threatens the biodiversity of the remaining Greenfields, tree-covered areas and accessible open green public spaces that are already significantly shrunk and ecologically undervalued due to the unregulated urban sprawl of the last decades.

The major economic engines of Hudson Valley, traditional building materials and farming, are currently unsustainable under the current context of Climate Change.or this project, the economies acknowledged as already obsolete. Following this urgent need for climate-responsive economic reform and taking into consideration the 2018 Timber Innovation Act and the forthcoming 2021 IBC Engineered Timber update that both harness the potential of mass timber building elements manufactured from sustainably managed-forests as a viable option for reducing the built space’s impact on the environment in the years to come, this project investigates the utilization of timber farming as a catalyst for environmentally and socioeconomically beneficial civic space design.

of researching, harvesting, manufacturing and retail, wasterecycling and branding for their timber product. By creating a shared collaborative infrastructure for local forest and small-timber-business owners and entrepreneurs, new social partnerships and equally-distributed amenities will be created, boosting local economies, while preserving the local and regional forest ecologies.

By sustaining long-term forest-plant-based economic development through this shared co-op system, Hudson Valley’s scaled-down timber industry will be funneled, while diverse communities will receive a more socially adequate distribution of profits. Composed by four entities, the Center for Resilient Forestry which is clustered with Wood Innovation Facilities, the Certification Centers, the Sawmill and Distribution Center with additional facilities for Recycling and Storage and Renewable Energy Generation, this project provides a lasting infrastructure that promotes a holistic framework for profitable and sustainable timber agroforestry that ensures the wellbeing of both the forest and its inhabitants. █

Tackling the large-scale U.S. monopoly of engineered-timber products, the project envisions a bottom-up timber economy - a vertically integrated, resilient timber supply chain - as a way to incentivize private landowners to sustainably manage their own forests, while directly accessing a shared infrastructure

THE FORMATION OF INFORMAL HAS ACCELERATED, AND SIGNIFICANT PRESSURES SOLUTIONS AND URBAN

VULNERABLE RESIDENTS UNDER EXTREME CONDITIONS. A LARGE PART OF THE

POPULATION CANNOT ACCESS HOUSING MARKET AND MUST HOUSING SOLUTIONS. _

THERE ARE

PRESSURES TO DEVELOP HOUSING INFRASTRUCTURE FOR AND MIGRANTS LIVING CONDITIONS. IMMIGRANT ACCESS THE FORMAL MUST RELY ON INFORMAL

The migration of refugees due to political and economic issues is not a recent phenomenon; in fact, it has always fueled the growth of cities. However, contemporary migrations present different patterns than those of the past. Globalization, climate crisis, political conflicts and technology have accelerated the pace and magnitude of migrations, impacting regions suddenly under intercultural clashing and significant social, political, and economic pressures on cities that receive new waves of migration. One of the most relevant and impactful migration processes of modern history has been the Venezuelan humanitarian and refugee crisis caused by a severe socio-political and economic crisis the country has faced for several years. More than 6.05 million Venezuelans have left their homes, most of them looking to settle in other Latin American and Caribbean countries.

The proportion of the immigrant population in Chile, with respect to the total of all Latin American countries, increased the most between 2016 and 2019, going from 2.15% to 8%. The formation of informal settlements has accelerated, and there are significant pressures to develop housing solutions and urban infrastructure for vulnerable residents and migrants living under extreme conditions. A large part of the immigrant population cannot access the formal housing market and must rely on informal housing solutions. This situation has caused an increase in irregular or self-built houses, temporary

shelters, and homelessness, where migrant families in extreme circumstances are sleeping in public open spaces, parks, and bus stations, among others. Between 2011 and 2019, the percentage of foreign heads of households residing in informal settlements increased from 1.2% to 30%, and it is estimated that 27% of households living in informal settlements today have foreign nationality. The Tarapaca Region in the North of Chile has the most dramatic situation, with 72% of foreign heads of household residing in informal settlements ( CES, 2021). Addressing the increasing housing deficit, neighborhood deterioration, and social-spatial segregation of migrants arriving in Chile has become a national priority (CNDU, 2021).

At a different dimension and scale, migration has also impacted rural areas and the local indigenous communities living in the Chilean border territory between Bolivia, Perú, and Argentina. Rapid migration through border villages located in the northern desert of Chile has impacted indigenous communities struggling to maintain their identity, cultural heritage, and customs while adapting themselves to cohabitate in a shared space with the globalized urban culture. The rapid proliferation of migrant populations in border villages and the effects of unbalanced and informal urbanization are generating the loss of land rich in natural, and agricultural resources as well as cultural heritage. Unplanned urbanization of the rural may cause irreversible cultural and environmental impacts, such as the dismemberment of the ecological mosaic, fragmentation of biodiversity corridors, and overload of municipal services, without internalizing the social and environmental costs of hidden suburbanization and informal settlements. █

ANINAT, ISABEL, AND RODRIGO VERGARA (ED.). Inmigración en Chile, Una Mirada Multidimensional. Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP), and Fondo de Cultura Económica (FCE), 2019.

ARAVENA, FRANCISCO. “La crisis de la inmigración ilegal y la violencia en el norte.” La Tercera. Last modified September 28, 2021. https://www.latercera.com/podcast/noticia/lacrisis-de-la-inmigracion-ilegal-y-la-violencia-en-el-norte/ MADZ7GSORVENTFW7WLESTZIJHA/

CES, TECHO, FUNDACIÓN VIVIENDA, “Catastro Nacional de Campamentos 2020-2021. Informe Ejecutivo.” (March 2021). https://ceschile.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Informe%20 Ejecutivo_Catastro%20Campamentos%202020-2021.pdf

CRUZ, TEDDY, AND FONNA FORMAN. “Unwalling Citizenship.” e-flux, (November 2020). https://www.e-flux.com/ architecture/at-the-border/358908/unwalling-citizenship/ CRUZ, TEDDY, AND FONNA FORMAN. “Unwalling Citizenship.” The Avery Review, issue 2, (January 20, 2017): 65-76.

CONSEJO NACIONAL DE DESARROLLO URBANO (CNDU), PNUD, “Propuestas para la regeneración urbana de las ciudades chilenas. Primer Informe CNDU 2021” (2021). https:// cndu.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/PROPUESTAS-PARALA-REGENERACION-URBANA-DE-LAS-CIUDADES-CHILENASCNDU.pdf

CONTRERAS, DANTE, AND SEBASTIAN GALLARDO. The Effects Of Mass Migration On Natives’ Wages. Evidence From Chile. Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), 2020.

IMILAN, WALTER, FRANCISCA MÁRQUEZ, AND CAROLINA STEFONI (ED.). Rutas Migrantes En Chile: Habitar, Festejar Y Trabajar: Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado, 2015.

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICAS (INE). “Censos de Población y Vivienda: Censo 2017.”, accessed April 5, 2022, https://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/sociales/censosde-poblacion-y-vivienda/informacion-historica-censo-depoblacion-y-vivienda

ROJAS, JORGE. Nosotros No Estamos Acá: Crónicas De Migrantes En Chile. Editorial Catalonia, 2021.

ROJAS PEDEMONTE, NICOLAS, AND JOSÉ TOMÁS VICUÑA UNDURRAGA. Migración En Chile: Evidencia Y Mitos De Una Nueva Realidad. LOM Ediciones, 2019.

ORIGINAL PHOTOS BY MATIAS DELACROIX FOR ASSOCIATED PRESS, PROVIDED BY THE AUTHORS | @ MATIASDELACROIXIT IS BECAUSE OF THIS INTERSECTIONALITY OF THESE RESOURCES ARE NODES THAT DEFINE A TERRITORIAL DYNAMICS.

ARE GEOPOLITICAL A LARGE PART OF OUR DYNAMICS. _

“Ojos de agua'' are natural resources rich in flora and fauna with unique geographic, geological and hydrological properties. They also represent unspoken powerful geopolitical nodes that have shaped our demography, history, economy, and both urban & rural memory. In recent years, these natural resources have become a testament of government mismanagement, territorial displacement, pollution and economic segregation. The current socio-political situation in Nicaragua comprises many of these individual issues. Therefore, understanding the neglect and decline of our natural resources is necessary to build the foundations of future mobilization to raise awareness and develop equitable resources management plans for Nicaraguan communities.

The history of Nicaragua is changing abruptly. Unfortunately, the current regime has diminished, impoverished and even distorted most of the national academic resources. The injection of propaganda by the Sandinista political party led by Daniel Ortega and under the yoke of Rosario Murillo, has completely infected any state resource in Nicaragua. In each logo, in each government website, on the streets, on buildings, in schools where children are indoctrinated and especially on television channels, we have been saturated by “Danielista” propaganda, as a method of clinging to power and establishing a dictatorial dynamic on information platforms. The censored media coverage by government forces have tried to keep issues of territorial relevance hidden from the public eye. Until today, the monopoly of projects along the shores of water resources keeps gentrifying rural communities and diverting attention to the importance of preserving natural resources.

Nicaragua has an inherent relationship with water. Although there is no exact translation of the Nahuatl language, different versions opt for translations such as: "land surrounded by water" or "Here by the water." The Pacific Ocean represents the western border and the Atlantic Ocean the eastern border of the

country. The Nicaraguan territory has two great lakes (Cocibolca and Xolotlán), around 30 recognized lagoons of which at least 11 are of volcanic origin. Coastal lagoons, bays and an artificial lake are other hydrological resources of the country.

Each “ojo de agua” in Nicaragua is an agent of change and highly determinant in shaping the communities around them. The relationship with the water resources of urban and rural centers define part of the cultural identity and relationship with nature. Much of the attraction and uniqueness of the volcanic lagoons across Nicaragua, consist in their endemic properties that have made the flora and fauna evolve in unprecedented ways. This effect extends to human dynamics and is reflected by seeing aerial views of the urban developments around these hydrological resources. Unfortunately, the gentrification in areas surrounding lakes and lagoons has led to misguided solutions like privatization of land, use of lagoons and lakes as human waste landfills.

This problem is intertwined with the Nicaraguan government’s deployment of propaganda that subverts plans to privatize natural lands under the guise of tourism that should be conserved and open to the public.

Ojos de agua are constellations that attract to their orbit a unique ecosystem, migratory animal species, human settlements, investments, tourism, international agents, political incentives, economic impacts, etc. It is because of this intersectionality of forces that these resources are geopolitical nodes that define a large part of our territorial dynamics.

Tourism in Apoyo Lagoon has been a two-sided story, a smokescreen that has been marketed as great works of progress by the Nicaraguan governments. The tourist monopoly in Apoyo Lagoon has been marketed as something that stabilizes the country's economy when it has actually only privatized

lands that should not be private; especially after considering that the natural areas around this lagoon were established as a natural reserve in 1991. Therefore, the projects carried out in natural areas of Nicaragua cannot continue to be approved by local authorities under the argument that they provide “jobs” for the community.

The privatization of land in the Natural Reserve Apoyo Lagoon has only profited a very low percentage of the population. Owners of restaurants, hostels and private residences on the slopes of the reserve mostly belong to a specific sector of Nicaragua with a high social or foreign stratum or in some cases from close relationships with government forces. The real outcome of these unlawful activities is evident in the journey to the lagoon where communities are withdrawn from the lagoon. There is a high contrast between these communities that also have economic and infrastructural limitations and many of the new luxurious constructions on the shore and slope of the lagoon that, precisely because of their high cost, become inaccessible for most of the Nicaraguan population. A natural reserve should not be privatized and instead should be able to breathe from private tourism to open its resources to the communities around it.

The lack of regulations has directly influenced the architectural development of the area in which we see a clear social pyramidal hierarchy in the buildings that have populated the lagoon in previous decades and the native constructions with limited resources that have been relegated to adjacent areas. Despite some initiatives in past years to build public spaces in the area, there is much work to be done to balance the amount of private property that continues to appropriate the immediate shore of the Lagoon. It is also important to consider a plan for public accessibility from urban centers to the shore of the Lagoon. Due to the lack of infrastructural plans and public spaces that are accessible and dignified, the population who want to visit

the lagoon are conditioned to go to one of these private touristic places, since they have better conditions to enjoy this natural resource or sneak between informal trails to reach to a shore that has been appropriated by all these businesses around the Lagoon. As Nicaraguans we should be able to enjoy our own tourism at its best, a tourism that is suitable for everyone.

Generations born in Nicaragua for the last few decades understand that our “Ojos de agua” are slowly dying. The excitement of visiting these incredible natural gifts reaches a

bittersweet end once you learn that because of the wrongful urban planning conducted by Nicaraguan Governments. We are losing part of the greatness of our land. This problem is now systemic, deep-rooted in our culture and lifestyle. The OrtegaMurillo regime uses their propaganda to present an intention of change. They have carried out what looks like projects that are meant to save some of these resources like the Sanitation Project in Lake Xolotlán (2012) and the Oxygenation Project in Tiscapa Lagoon (2019).

The failure of these projects quickly became evident, precipitated by misguided leadership. There cannot be a plan

to sanitize our water resources without a transformation in the planning of our urban settlements or the wrongful rainwater urban infrastructure with sewers that continue to pollute these resources. Finally and perhaps most importantly, we cannot save our lakes and lagoons if we don’t change our human culture. This last item is problematic for the current regime because it involves education. In order to create real change in our country we need to empower our communities with access to good free education. The Ortega-Murillo regime is aware of this and that’s precisely why they have hacked and infected the education system with propaganda. There cannot be a significant change in Nicaragua, if the population doesn't

change their mindset. What is the purpose of cleaning the lakes and lagoons? If the lack of education and proper infrastructure keeps polluting them? Each element is interconnected. The problem is that empowering the Nicaraguan population would mean the end of their dictatorship. █

2. LARA, RAFAEL. “Managua y sus cinco lagunas en peligro”. El Nuevo Diario, 09 de octubre, 2016. <https://www.elnuevodiario. com.ni/nacionales/406804-managua-sus-cinco-lagunas-peligro/>

3. GUEVARA, KAREN & CLARET, JEANETTE. ““Causas y consecuencias de la contaminación en el lago de Nicaragua”. UNAN Managua, Enero, 2015.

4. NAVARRO, ÁLVARO. “Laguna de Apoyo: el santuario tropical”. Confidencial, 23 de Marzo, 2016. <https://confidencial.com.ni/ laguna-apoyo-santuario-tropical/>

5. LAGUNA DE APOYO, el mejor destino turístico, más cerca de Managua. Confidencial, 20 de Marzo, 2016. <https://confidencial. com.ni/la-laguna-apoyo-mejor-destino-turistico-mas-cerca-managua/>

6. LAGUNA DE PERLAS. Travel Guide de Nicaragua.<http://travelguidenicaragua.com/destinos/area-atlantico/laguna-de-perlas/>

7. LAGUNA DE PERLAS. Vianica. <https://vianica.com/sp/atractivo/180/laguna-de-perla>

8. BARRIOS, ORLANDO. Contaminación en Laguna de Masaya no se detiene. El Nuevo Diario, 25 de Enero, 2017. <https://www. elnuevodiario.com.ni/nacionales/416720-contaminacion-laguna-masaya-no-se-detiene/>

9. LAGUNA DE PERLAS. EcuRed. <https://www.ecured.cu/Laguna_de_Perlas_(Nicaragua)>

10. RESERVA NATURAL DE WAWASHANG. Vianica. <https://vianica. com/sp/atractivo/97/reserva-natural-de-wawashang>

11. TÓRREZ, CINTHYA. “Le tomarán el pulso al saneamiento del lado Xolotlán. La Prensa, 27 de Junio, 2017. <https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2017/06/27/nacionales/2253052-le-tomaran-el-pulso-al-saneamiento-del-lago-xolotlan>

12. Canal interoceánico en Nicaragua: ¿cortina de humo o plan secreto?. DW. <https://www.dw.com/es/canal-interoce%C3%A1nico-en-nicaragua-cortina-de-humo-o-plan-secreto/a-50059308>

13. LOBO, TOMÁS. Canal de Nicaragua, el viejo sueño interoceánico que se resiste a morir. El País Costa Rica, 10 de Julio, 2020. <https://www.elpais.cr/2020/07/10/canal-de-nicaragua-el-viejo-sueno-interoceanico-que-se-resiste-a-morir/>

1. GONZÁLEZ, MAURICIO. “Contaminación asfixia a la laguna de Tiscapa”. El Nuevo Diario, 25 de enero, 2018.<https://www. elnuevodiario.com.ni/nacionales/453778-contaminacion-asfixia-laguna-tiscapa/>

14. MONCADA, ROY & SILVA, JOSÉ. El gran canal de Nicaragua, el megaproyecto que quedó en papel. La Prensa, 19 de Diciembre, 2019. <https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2019/12/19/nacionales/2623304-el-gran-canal-de-nicaragua-el-megaproyecto-quequedo-en-papel>