The original edition of this publication was made possible by the support of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia University New York, New York

Copywright © 2023 by the Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York

All illustrations and layouts © 2023 URBAN Magazine

All photographs © 2023 URBAN Magazine

All rights reserved

URBAN MAGAZINE

Weedscapes: When Commercial Cannabis is Your Neighbor

Daniel C. Froehlich, MSUP

The Importance of Native Pollinators

Jonah Bregstone

NATURE

Land Imaginaries and Israel’s Educational Map

Lealla Solomon

16 — 19

NATURE

20 — 25

STREET

Saturday

Kurt Steinhouse

Playscapes

STREET 10 — 15 28 — 29

26 — 27

NATURE

Jim Lammers and Sabina Sethi-Unni TABLE OF CONTENTS URBAN VOL.33

IN-BETWEEN

New Paradigms of Residual Space

Douglas Woodward

IN-BETWEEN

The New American (Paradoxical) Escape Guide: Illustrated

Dakota Smith

ARCHITECTURE

FICTION-scape

Jaasiel Duarte-Terrazas

ARCHITECTURE

Regenerative Food Parks: A Proposal for the Akaki Territory

Elini Kalapoda

ARCHITECTURE

Airport Religious Spaces and Meditation Rooms

Kevin Costa

TABLE OF CONTENTS URBAN VOL.33

30 — 33 48 — 51 44 —47 40 — 43 34 — 39

HUMANS

Parallel Cityscapes: The Aesthetics of a Gentrifying Bushwick

Luke McNamara

Generations of Planning: An Interview

Eshti Sookram

HUMANS

Garażowa Alternatywa

Nikolas Michael

58 — 61

HUMANS

The Saturday Staycation

Ethan Floyd

Mish min Baris ana min Salaam: Centering Marginalized Identity as Political Speech in Contemporary Egyptian Rap

62 — 65

HUMANS

66 — 69

SOCIETY 52 — 57 70 — 75

Calvin Harrison TABLE OF CONTENTS URBAN VOL.33

SOCIETY

Queerscapes

Daniel Wexler

78 — 83

SOCIETY

Paper Estates

Jenna Dublin-Boc

84 — 85

SOCIETY

City and Desire

HaoChe Hung

INVISIBLE 86 — 87

The Digital Nomadic Footprint in Cincinnati

INVISIBLE

Crumbs in the CyberCity

Mia Winther-Tamaki

TABLE OF CONTENTS URBAN VOL.33

Olivia McCloy 76 — 77 88 — 91

VOL.

33

Letter from the Editors

We stand witness to the symphony of urbanism and planning — a dance of progress, hope, and innovation. Within the intricate tapestry of our cities, we are confronted with intricate issues like opposing views of land ownership, wounded geography suffering from the effects of climate change, and unjust, limited access to green space. But amid these challenges lies a beacon of hope — a collective determination to weave a future where harmony thrives, cities embrace their citizens with open arms, and sustainable solutions become our guiding star. Together, we shall transcend boundaries, blend facts with foresight, and venture towards an urban panorama that flourishes like never before.

In the spirit of exploration, we welcome you to SCAPES — an invitation to dive into the depths of spaces, places, and ideas. SCAPES is more than a theme; it's an open canvas where the imagination takes flight. As you embark on this journey, know that SCAPES allows for boundless interpretations. Be it through thoughtful essays, striking photography, or visionary designs, SCAPES invites you to defy conventions, redefine boundaries, and dream beyond the confines of reality. As you move through these pages, submissions are set within "scape" sub-layers including nature, the street, the in-between, architecture, humans, society, and the invisible, illustrating our contributor’s courageous expeditions through a breadth of urban stories.

As future planners, urbanists, and practitioners, the path ahead beckons with promise and potential. Collaboration shall be the compass guiding your steps, as you discover the strength of unity in forging new urban realities. Embrace innovation as your ally, for within its folds lies the power to unravel urban dilemmas. Yet, as you delve into this realm of endless imagination, remember the essence of humility and the art of listening. In the whispers of space around us, the city speaks its silent wisdom. Amidst the rush of progress, lend an ear to the stories of those who inhabit these urban landscapes, for their voices shall echo in your designs, shaping cities that nurture and inspire.

This issue would not be possible without the submissions of the twenty-one students, professionals, and creatives we are lucky to feature. As you read Vol. 33, we ask you to be willing to listen carefully and immerse yourself in the elegance and profound nuances between humans and space.

Kyliel, Eshti, Gabby, Rob, Olivia, Felipe, Ethan, Matt, Alyana, and Claudia LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Authored by Daniel C. Froehlich

WEEDSCAPES:

When Commercial Cannabis is Your Neighbor

If you celebrate Thanksgiving, you likely have an unknowing connection to the exurban corner of southeastern Massachusetts where I grew up. The area’s sandy soil and high water table are particularly amenable to cultivating cranberries, which grow on tight, crawling vines in low-lying, swampy depressions called bogs. The region produces a disproportionate amount of the global cranberry supply, and the industry commands a prominent place in the local economy and culture; my hometown’s master plan estimates that nearly 50 percent of the municipality’s land area is dedicated to cranberry agriculture (SRPEDD 2017). This becomes particularly obvious during the autumnal harvest: the bogs flooded with icy water, the submerged berries beaten off their vines with specialized machinery, the floating crop siphoned off the surface, all in a strange, mechanical-yet-pastoral ballet. The patchy seas of flaming crimson that result are etched into my memory as an integral element of my erstwhile agrarian landscape (Figure 1).

10

FIGURE 1 - Bright red patches of floating cranberries during the autumn harvest captured by Landsat imagery over southeastern Massachusetts (October 2022)

What was decidedly not part of that landscape, however, was commercial cannabis cultivation, though that cannot be said for many not-so-differently-situated communities in northern California (Figure 2). The Counties of Mendocino, Humboldt, and Trinity constitute the Emerald Triangle, an historic epicenter of cannabis cultivation described in one place as “the cannabis bread bread basket of the Pacific Northwest” (Lee 2012). Originally associated with the counterculture and backto-the-land movements emerging in the 1960’s, cannabis cultivation in the region became an increasingly lucrative economic activity with the collapse of the local timber and fishing industries and rising levels of drug enforcement in the decades following (Corva 2014). Experts agree that, though difficult to quantify, the Emerald Triangle’s legacy cannabis industry contributes billions of dollars annually to local economies otherwise lacking in opportunity (Short Gianotti et al. 2017).

California became the first American state to legalize medicaluse cannabis in 1996 through ballot initiative, doing so without benefit of a comprehensive, statewide regulatory framework and setting off a two- decade cannabis industry free-for-all known as the Green Rush. Not until 2018 did California finally establish such a system for both medical- and recreational-use cannabis, finally positioning local governments to directly regulate cannabis-related activities through their zoning and other police powers.

Recognizing the fundamental socioeconomic role cannabis cultivation plays for its communities, legacy growing jurisdictions drafted their local regulations to include special accommodations for pre-existing cultivators. In the ordinances it adopted starting in 2018, Mendocino County created a unique zoning mechanism allowing for the establishment of Cannabis Accommodation Combining Districts. Through a process functionally equivalent to a rezoning, neighborhoods with legacy cannabis cultivation could petition to have the special district overlaid on contiguous parcels of consenting property owners The combining district relaxed to 20 feet the otherwise required 100foot setbacks between cannabis grows and residential structures on separate parcels and the 50-foot setbacks from property lines; with a discretionary land use permit, the property line setback could be absolved altogether. The County enacted four such districts in December 2018, thereby creating neighborhoods where commercial cannabis cultivation could remain uniquely integrated into the local landscape.

Having spent a disquieting amount of time researching local cannabis land use regulations, I find this whole situation rather intriguing. So, using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) -based methods, I set out to investigate: what would be the impact onto legacy cannabis cultivation in these combineding districts if not for these special accommodations?

11

FIGURE 2 - Tiny perforations in the forest canopy consistent with legacy cannabis cultivation captured by Landsat imagery over Mendocino County, CA (September 2022)

My study area is the combineding district in Laytonville, a rural, residential neighborhood in north-central Mendocino County. Mendocino is a relatively data-poor jurisdiction, so I had to build my spatial datasets from scratch. I georeferenced and digitized planning department figures and maps to create parcel boundaries within the combining district; I then crossreferenced the parcels against the jurisdiction’s online property search applications. From there, I identified and digitized residential structures from readily-available aerial imagery and then examined that same imagery for evidence of cannabis cultivation on each parcel. A suspected grow site needed to conform to one of four typologies common to legacy cannabis cultivation in northern California to be included in the analysis (Figure 3). With my custom-

built datasets, I first calculated the 100foot, offsite residential structure buffer and then added the 50-foot property line buffer in order to quantify the reduction of usable area on each parcel (that is, the area not occupied by a residential structure) and the reduction in existing cultivation that would result from the otherwise required setbacks without the combining district (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3a - A suspected grow site needed to conform to one of four typologies (not mutually exclusive) common to legacy cannabis cultivation in northern California to be included in the analysis:

(a) regularly-spaced plants or ground disturbance within a perforation in the forest canopy; (b) regularly-spaced plants or ground disturbance within an enclosure for screening and/or security purposes; (c) a series of agricultural structures like greenhouses or hoophouses; (d) a smaller agricultural structure adjacent to regularlyspaced plants or ground disturbance.

4 - A

view of

setbacks that would be in play without the Cannabis Accommodation Combining District. The residential structure (A) on Parcel 1 casts a 100foot setback (B) on adjacent parcels. Parcel 1’s property line also casts a 50-foot setback (C) on adjacent parcels. The portion of Parcel 2 not controlled by the setbacks (D) represents the remaining usable area. The portion of the cannabis grow on Parcel 2 intersected by the setbacks (E) is eliminated, with a small portion of existing cultivation area remaining (F).

12

Daniel C. Froehlich, MSUP

3a 3b 3c 3d

FIGURE

schematic

the

Through this process, I identified 101 cannabis grows in the district, amounting to 16 acres of cultivation area. I was surprised to find that the residential structure setbacks alone had fairly little effect. They eliminated only about four percent of usable area on grow site parcels and only about one acre of existing cultivation area overall. However, factoring in the property line setbacks had substantial consequences. The full setbacks eliminated over 50 percent of both usable area and existing cultivation area. They rendered six grow site parcels fully undevelopable, with another 14 rendered severely constrained (Figure 5A), defined as containing less than 2,500 square feet of usable area (that is, the upper canopy area limit for the smallest state cultivation license type issued by the California Department of Cannabis Control). In terms of the existing cultivation area, as presently configured, the setbacks completely eliminated 21 grows and rendered an additional 46 severely constrained, with less than 2,500 square feet of cultivation area remaining (Figure 5B)

Weedscapes 13

In a hollow attempt at sophistication, I also ran multiple regression models to explore what factors most significantly constrained grow site parcels when accounting for the full setbacks. However, the characteristic that most often landed on top was the most intuitive one: parcel area. As parcel area decreases, the proportion of usable area lost to the setback restrictions increases. Though disappointingly straightforward, this is particularly important in the Laytonville combining district, which is dominated by small lots developed with single-family

and mobile homes. Among grow site parcels, those below the median area account for only 14 percent of the total area; however, they hold more than a third of the total existing cultivation area and over half that was eliminated by the setbacks (Figure 6). In other words, the smallest landholders in the combining district would bear a disproportionate loss of the cultivation area while also possessing the least capacity to

14

FIGURE 6 - The smallest grow site parcels account for less than one-fifth of total grow site parcel area but over half of the cultivation area eliminated by setbacks. They also hold but a tiny fraction (3.7%) of the remaining usable area on grow site parcels after accounting for the setbacks.

Indeed, Laytonville’s viability as a legacy growing community would be harshly stifled if not for the available setback reductions provided by the combining district. While this is exactly what I set out to demonstrate quantitatively, my most important finding, perhaps, is the simplest one. While the Laytonville district encompasses nearly three hundred parcels, only 35 percent of them host identified cannabis grows. Since owners had to consent to their properties being included in the district, this indicates that a majority of residents and property owners— though not necessarily involved with the cannabis industry themselves— were at least tolerant, if not outright supportive, of their grower-neighbors’ ability to continue cultivating in the era of liberalization. Laytonville, therefore, is a unique case study of a community’s efforts to utilize planning mechanisms in preserving its cultural and economic landscape. It is also a reminder to those working in the built environment disciplines that one group’s locally unwanted land use (LULU) may in fact be another’s hard-earned livelihood.

Though scarcely comparable, Laytonville may provide lessons for closer to home here in New York City. With the recent proliferation of illicit cannabis retail storefronts, commercial cannabis has begun to have an increasingly discernible impact on our urban environment (Figure 7). Despite what the streetscape might suggest, there are (as of this writing) only four recreational use establishments in NYC holding valid state cannabis retail licenses (OCM 2023), and, by all

accounts, the City appears to lack any comprehensive strategy for siting and regulating cannabis-related facilities, much like California jurisdictions during the Green Rush (Southall 2022). I venture not to offer solutions here, but I do pose some questions for planners and other government functionaries to consider. How do policymakers avoid “one-size-fits-all” cannabis controls that may not reflect every community’s values? What are the actual land use impacts of cannabis-related facilities, rather than the normative judgments held about people who grow, manufacture, sell, and use cannabis products? How can cannabis regulations balance public health, safety, and welfare while acknowledging and accounting for those groups most disadvantaged by historic prohibition?

New York State’s cannabis regulatory system is unique in that it prioritizes justice-involved applicants and non-profit organizations in the retail licensing process. NYC’s first legal recreational dispensary is operated by Housing Works, an advocacy group for homeless and low-income persons living with HIV/AIDS. Only time will tell how such a model will function and if it can meaningfully and equitably address the harm done by decades of cannabis prohibition. In the interim, though, you can take a trip to the East Village, contribute to a worthy cause, and contemplate your own landscape—rural, hyper-urban, or otherwise—from a new perspective.

Weedscapes 15

FIGURE 7 - An illicit cannabis retail storefront on Broadway in Morningside Heights representative of those that have proliferated across New York City since the summer of 2022 (April 2023).

Jonah works at the United States Geological Survey's Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab where he studies the relationship between native plants and pollinators.

Written by Jonah Bregstone

THE IMPORTANCE OF NATIVE POLLINATORS

Native pollinators provide vital pollination services to many ecosystems. In NYC, community gardens and other forms of urban agriculture are dependent on ‘wild’ bee populations for pollination (Matteson et al, 2017). In some studies, urban areas have been found to have a higher diversity and abundance of native pollinators than neighboring rural or ex-urban areas (Matteson et al, 2008). As human created environments (cities, highways, suburbs) cover more of the globe, it is important that ecosystems within the built environment be encouraged and conserved. Native pollinators are key to the creation and restoration of urban ecosystems. Planning for pollinators ensures the success of urban agriculture, increases biodiversity, and supports density (Bergmann, 2019).

Native pollinator populations are supported best by a network of foraging and habitat space. An ecological sink is formed when only an isolated patch of the urban environment is landscaped to support pollinators. This can lure a pollinator to visit an area in search of

foraging resources but it is not enough to support a sustained pollinator presence. One community garden, backyard or public space landscaped to encourage pollinators is not sufficient. Instead, a network must be created within an urban space. This idea is articulated in Sarah Bergmann’s Pollinator Pathways Project, which encourages communities to plan corridors of foraging and habitat resources to increase the abundance and diversity of pollinators.

The relationship between native pollinators and native plants is vital to many of the ecosystems in North America. Native Bees have spent millennia cultivating a symbiotic relationship with native plant species. This coevolution is seen in the positive correlation between the length of a pollinator's proboscis (mouthparts) and the length of the floral tube of native pollinating plants (Dohzono, 2008).

This deep relationship distinguishes native bees from non-native domesticated bees like the European Honey bee (Apis mellifera). Non-native

bees, while very effective at pollinating monocultural row crops, are not as effective at pollinating native plant species. Domesticated non-native bees are generalists and are able to thrive and spread in many ecosystems in North America. These bees often outcompete native species for habitat and foraging resources, depriving an ecosystem of pollination from native pollinators. Monitoring the abundance and diversity of native pollinators is key to ecosystem resiliency and preservation. Despite this importance, there is a dearth of information on the flower-preferences of native pollinators.

Methods and Data

The Native Bee Lab uses repeated photography in our non-lethal pollinator monitoring experiment. The lab retrofitts donated cell-phones turning them into deployable bee-monitoring cameras. The phones are placed in the Patuxent wildlife preserve to take repeated photos of individual pollen producing blooms. After a day of photo capture, the phones are collected and

16

the data is uploaded for future analysis. Metadata about the capture event, including weather, time and location are all recorded.

The research team records pollinator arrivals and approximate dwell times from the photos. Secondary analysis is completed by pollinator-ID specialists who attempt species-level classification

of the photographed insects. The pollinator arrivals are a heuristic for pollinator flower-preference. Once complete, this flower-preference analysis can be disseminated to gardeners, ecologists and urban planners. This data will ensure that future pollinator-focused landscaping is conscious of native pollinator flowerpreferences.

FIGURE 1 - A recycled phone takes timed photos of yellow-tickseed (Coreopsis). A shade has been placed over the phone to keep the device from heating up in the Maryland sun.

FIGURE 1 - A recycled phone takes timed photos of yellow-tickseed (Coreopsis). A shade has been placed over the phone to keep the device from heating up in the Maryland sun.

17

Modeling Native Pollinators

The histogram in Figure 3 shows the preliminary results of our data analysis. The ~67 hours of photo data collected over the summer has been grouped into three-minute increments and the number of arrivals for each three-minute increment calculated. These three-minute increments have then been normalized. The graph represents the percentage of time we observe x number of pollinator arrivals. This analysis shows that most observed increments were not uneventful. Roughly 91.5% of all three-minute windows did not record a single pollinator arrival.

FIGURE 3 (left) - A histogram of pollinator arrivals bucketed into three-minute increments.

FIGURE 3 (left) - A histogram of pollinator arrivals bucketed into three-minute increments.

18

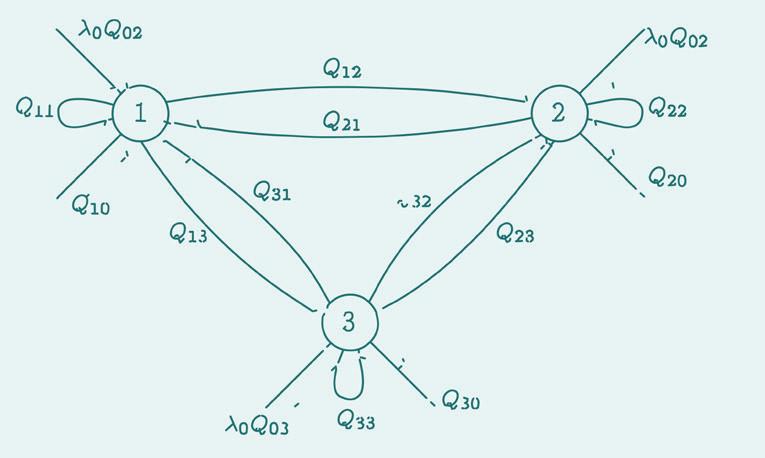

The arrival behavior can be modeled by the Poisson probability distribution. The Poisson distribution models success of a trial (i.e. arrival of a pollinator) over time. This distribution describes natural phenomena, including the rate of particles emitted by a radioactive source and the frequency of customers entering one’s local grocery store. The descriptive powers of the Poisson probability distribution underpin whole fields of mathematics.

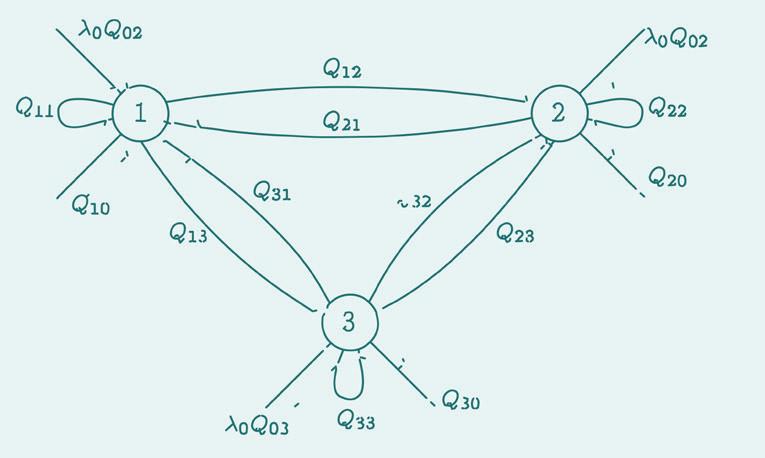

Using the Poisson process as a foundation, our team can model the environmental context for the observed pollination activity. The pollen producing flower is a resource with a queue. Competition for this resource can be measured with photo analysis. A network of such queues simulates the interactions between pollinators and different pollen-producing plants. This type of network is referred to as a stochastic processing network.

Stochastic processing networks model a range of systems from cloud computing resources to a simple traffic intersection. These networks abstract a system to just the factors that influence the system’s ability to meet service demands. Through this abstraction, stochastic processing networks become useful models of resourceutilization, including the resource of pollen and the utilization by pollinators in our study. Customers in need of processing, including pollinators in our ecological setting, traverse these networks and queue at processing

nodes. The customers are subject to stochastic arrival rates, processing times and the routing of the network (Williams). However, while a traditional stochastic processing network assumes that the resource is available all the time, in an ecological setting, the availability of the resource changes over time and in response to weather. To extend the traditional network and make it useful for our study, we must incorporate these covariates.

This model translates the physical relationships that native pollinators have with pollinating plants into the digital realm. The results of the study will be meaningful from both ecological and mathematical perspectives. This model will predict pollinator abundance and diversity for different landscaping strategies. These predictions will inform urban planners and urban gardeners who choose to proactively plant for native pollinators.

Next Steps

The Native Bee lab is completing analysis of the first year of data. Along with the photo data, the lab recorded ~21 hours of video which, when analyzed, contain the “true” counts of pollinator visitation. The team will measure the efficacy of the sampling method through the comparison of the photo data to the video. If there is alignment between the data sets, the team will have confidence in the monitoring method. If the datasets do not align, adjustments will be made to the frequency of photos in our methodology. Changing the frequency of photos must take into consideration the labor of analyzing photos and the cost of storing more photos.

Ultimately, the team would like to use this monitoring method on an entire metro-region. Our first-year analysis will document processes and resolve potential impediments to scale. The Native Bee lab specializes in pioneering monitoring methods that can be scaled into citizen-science projects. Through the lab’s vast network of volunteers and bee enthusiasts the monitoring experiment can be repeated with proper instruction and resources. By expanding data collection and aggregating photo monitoring from a wider group we can better inform our model and glean more information about the abundance and preferences of native pollinators.

Acknowledgements

It is important to acknowledge all of the guidance given by the team at the Native Bee lab including Sam Droege, Sydney Shumar and Claire Maffei. It is equally important to acknowledge all of the work done by our incredible team of interns Tashane Freckleton, Reyna Farley, Amelia Coriell, Dorcas Ogunbanwo and Osten Eschedor without whom this work would not be possible.

FIGURE 2 (left) - A honey bee lands on a burmarigold (bidens laevis). The flower is attached to a stake in order to keep the flower from moving during the capture period.

FIGURE 2 (left) - A honey bee lands on a burmarigold (bidens laevis). The flower is attached to a stake in order to keep the flower from moving during the capture period.

The Importance of Native Pollinators

19

FIGURE 4 - Stochastic Processing Network (Gallager)

Written by Lealla Solomon

LAND IMAGINARIES AND ISRAEL’S EDUCATIONAL MAP

Two recent articles focus on the relevance of the Green Line in the Israeli-Palestinian territory; In the first, Meron Rapaport reflects on the May 2021 wave of violence between Israeli and Palestinian forces while focusing on the character of The Green Line, arguing for its blurification and irrelevance in a reality of constant change, crossing and settlement building¹. In contrast, 40 miles away from the line Or Kashti writes to Haaretz about a recent scandal; the decision of Tel-Aviv's municipality to include the Green Line in educational maps. As Rapaport argues for a porous territory, bringing forward many forms of illegal tactics, governmental annexations, organized modern planning typologies, peace organization, police/settler, and Palestinian violence, Kashti's article focuses on the simplified view of a line, in the binary reality of depiction or erasure. The contrast between these two depicts the difference that will be argued in this article; between land ownership complexities and flattened imaginaries of land.

The complexity that Rapoport refers to is vividly depicted in Weizman's Hollow Land, where the continuous fury in the “wild frontier” between the ‘youth of the hill’, Palestinian civilians, IDF forces, and the armed Palestinian militants, constitute the chaos of the West Bank². He describes the frontiers of the Occupied Territories as elastic transformative borders, adding to Zvi Efrat's depiction of Israel's "borderline disorder" as a net that morphs and changes according to the situation at hand³, and strongly dismisses the idea

of a linear one⁴. The back-and-forth operation of setting up an outpost by settlers, who then clash with Palestinian farms, to only be combated by the IDF, to be combated by Palestinian militants, to then establish more outposts as punitive measures, forms the continuous fuzziness of the space. This is shown in a clear mapping (image 1) of the West Bank, where Weizman illustrates “an incessant sea dotted with multiplying archipelagos of externally alienated and internally homogenous ethnonational enclaves”⁵. This, which is elaborated thoroughly in Hollow Land, contributes to Rapaport's borderline claim and formulates the complex reality of the Israel- Palestinian territory.

In contrast to that, and in relevance to the second article, I must bring forward a personal story. Born and raised in a suburban town in the center of Israel, I grew up thinking that Palestine did not exist, it was a country in the past in when Israel was declared, just disappeared. It is not that I was explicitly told that or read about that, but it was the absence of Palestine from my education that formed its complete historical insignificance. The most generous and vivid proof of this absence, that can be historically traced, is the educational map, hung up in every class and refered

1 Meron Rapoport, “The Line Separating Israel From Palestine Has Been Erased—What Comes Next?,” August 10, 2022, https://www.thenation.com/article/ world/green-line-apartheid-equality/.

2 Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation, New edition (London New York: Verso, 2017), 3.

3 Zvi Efrat, The Object of Zionism: The Architecture of Israel, 3.

4 Weizman, Hollow Land, 6.

5 Weizman, 7.

21

IMAGE 3 (left): Photographed by Efi hoory, The Green; Line, Israel, 1964.

Photographed by Efi hoory, The Green Line, Israel, 1964.

to when necessary. The map (image 2) containing a topographical representation of hills and valleys is given a holistic character due to the contrasting depiction of its neighboring countries. Palestinian territories, in the most simplified way, are depicted by the same topographical representation, and thus, are imagined as part of Israel's land. A twelve- year length of observation, lead to complete ignorance of the land, which defined my military service, political opinions, and daily life. Recognizing this personal experience as a systemic arrangement, this story must be further historically explored, theorized, and situated in the larger picture of Israel's relation to land. The aim of this text will be to understand what is the work that the educational map does for Israel's relation to land, or in other words, how it enables land to be rendered possible as negotiable, extractive, ready to be conquered, demarcated, and controlled, and how it is part of a historical enterprise of land imagery. To center the discussion around land I will first give a capture of relevant theories of its possession in relation to its appropriation, resource establishment, and communication. Then I will dive into the historical events that led to the Jewish imagination of land, from the construction of the agrarian Jew to the establishment of the Green Line, and the political discourse that led to its current depiction. Finally, I will connect the dots between map-making, identity production, and relations to land, to reveal the implication of them on the current perception of land through the educational map.

Making Land

Recent work by historians has enabled the critique of historical processes of land

possession, such as the colonization of the New World, Africa, and more. They show us that they do not only entail the arrival on land and the wave of a flag, as depicted in many historical paintings and imagery but necessitate a fundamental structure of international law, institutions, cultural framework, acquisition processes, survey making and more. Land titling is a complex process, in which to be accepted by the relevant audience must be planned and structured in a national effort. The following synthetic view of theories of land possession will draw these processes into a framework that will tie large-scale land appropriations with their community's small scaled cultural meanings, claiming the intricacy and complexity of land possession, national identity, and culture.

In “Land-Appropriation as a Constitutive Process of International Law” Carl Schmitt, a figure of complex political history but one whose contribution to the thinking of territory in the 20th Century cannot be avoided, offers the important relationship between constitutive acts and constituted institutions in the historical European colonial acts of land appropriations.

To him land appropriation is possible with the aid of two terms of legal history; “those that proceed within a given order of international law, which readily receives the recognition of other peoples, and others, which uproot an existing spatial order and establish a new nomos of the whole spatial sphere of neighboring peoples”6. Thus, he differs between constitutive acts and constituted institutions; the constituted lies within the space of state legality,

22 Lealla Solomon

IMAGE 1 (below): Btselem and Eyal Weizman, Map of the West Bank, 2002.

where the origin of it is a mere fact in the functioning system and the constitutive, in relation, are the ones prior to the constituted, serve as the fundamental ground of legitimacy to other acts. In the delicate formation of land through appropriation, where the existing spacial order changes, constitutive acts set the legal foundations for future social relations in terms of land possibilities, and serve as the spacial boundary of neighboring acts.

While the constitutive act renders the land visible, it is not on its own enough to make the land work. Tania Murry Li, who is a current anthropologist in the realm of land, labor and capitalism, writes in her 2014 essay “What is land? Assembling a resource for global investment” about the global land rush about a series of following acts that could turn land into a productive object and draw its potential users' attention. To her, this process “requires regimes of exclusion that distinguish legitimate from illegitimate uses and users, and the inscribing of boundaries through devices such as fences, title deeds, laws, zones, regulations, landmarks, and storylines.”⁷ In other words, to make the land into a resource, a state not natural or internal to it, official institutionalized work has to be done. Official measuring of the land, material calculations, statistical picturing, marketing strategies, and more make practices on land thinkable, imagined, and relevant from a distance. They offer modernist legitimacy to a list of future land uses that transform the land into a productive and profitable resource for its potential future owners.

The combination of land appropriation, which involves changing theexisting

social arrangement, andtheprocess of rendering land as a resource, creates demand for it, which could lead to land ownership frictions between those who previously cared for the land and those who are now its legal possessors. In this situation, according to Carol M. Rose, a professor at Yale Law School who focuses on property, land use, and environmental law, communication of ownership is the key to continuous clear possession and the way to avoid forms of its loss. Thus, the clear act of the first appropriation is followed by a series of continuous acts that make visible its occupancy. To her “acts of possession” are “texts” which are “"read" by the relevant audience at the appropriate time,”⁸ and are “published” under useful circumstances. They are actions that have “interpretive communities” that can read the claim and give it significance within the cultural context. For example, acts such as agricultural work, front lawn manicuring, clearing out the mailbox, having lights on at night, and more, can be interpreted in an American suburb as common occupancy and will keep intruders away. In the entangled case of colonial appropriation, these acts are not only a matter of local culture but are definitive for colonial legitimacy and can normalize illegal events within the process of land grab.

These three, which differ in scale, time, space, and recurrence, form a process of exclusive land possession that is entangled with national law and culture. The combination of constitutive acts within an international legal framework, official work that renders land as a resource that drives up demand, and the constituted cultural communication that keeps the land possessed and owned, is bound

up with its national institutions. In the process of the emergence of a country, this does not only constitute the title of land ownership but produces a set of national cultural identities and practices that are parallel to it. Understanding the existence of these two processes will help, in the following pages, to analyze how in the process of colonizing the land of Israel a national culture of land emerged and reveal how and why this cultural history still exists fully today.

National Land and Identity

The previous example of land ownership complexity should not be taken as a given fact. Israeli citizens did not simply arrive in Palestine, they did not settle in the West Bank, the Golan Heights, or Tel-Aviv only because of mere individual will, and they did not always see the land as the one to be 'taken back'. According to Efrat, The Zionist movement was “a peculiarly deviceful architectural movement”9, which was in an operative “mode of space-planning, place-making, terrainmarking, land-grabbing, landscaping, facts- grounding, settlement-setting, rural-prototyping and urban-reforming”10, and involved politicians, architects, engineers, and other experts. While this large enterprise cannot be fully articulated in one paper, pinpointing

6 Carl Schmitt and G. L. Ulmen, The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum (New York: Telos Press, 2003), 82.

7 Tania Murray Li, “What Is Land? Assembling a Resource for Global Investment,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39, no. 4 (October 2014): 589.

8 Carol M Rose, “Possession as the Origin of Property,” 2022, 84.

9 Efrat, The Object of Zionism, 14.

10 Efrat, The Object of Zionism, 14.

23 Land Imaginaries and Israel’s Educational Map

three land-related historical strategies; the biblical back- to-land mythology and Zionist Jewish Autochthony, the strategic negotiable demarcation of land, and the land's cartographic public imagery could offer an explanation for the current educational enterprise of the imagination of Israel's land.

First, as I explained before, for land to be settled from afar, work has to be done to render it as a resource. In the "The Epos of Jewish Autochthony" in The Object of Zionism, Zvi Efrat comes to describe the important nature of the Jewish 'backto-land' ethos, rooted in the turn of the nineteenth century, as a luring approach for potential settlers. As Zionists argued for the need “to forgo urban areas for rural life on Palestine's moshavot”,11 they combined the land's cultivation potential with the Jewish biblical calling. Theodor Herzel in Old-New Land entailed a didactic narrative to settle the land where he “meticulously built an exhaustive and seductive mise-enscene of sumptuous landscapes inhabited by well-informed, happy farmers and creative urbanites.”12 The Zionist narrative produced an enterprise of architectural typologies, propaganda, fiction, literature, and preparation schemes, that rendered land barren and ready to become a resource to potential settlers. Thus, the work done to form the imaginary peasant utopia of Palestine was a calculated, wellthought Zionist venture that pushed the Jewish diaspora to see the land as a future possibility.

Aside from this production, land demarcation strategies turned out to be fruitful in rendering the occupied land negotiable and thus, available for possession. Its legal roots can be pinpointed to the 1945 Declaration of independence

when “David Ben-Gurion registered his opposition to drafting and announcing the borders of the imminent State”13 and insisted on waiting for the end of the war. This halt later transformed into an “openended project-a diplomatic, military, and colonial enterprise subject to ongoing negotiations”14, where possession of the land was subjected to physical existence on it. In other words, Rose's theory could not be more evident, where the one who speaks louder, with all the violence entailed in it, is the one who owns the land. Efrat describes this tactic as a net that morphs and changes according to the situation at hand, which later transformed into a continuing “openended project, a diplomatic, military, and colonial enterprise subject to ongoing negotiations”15.

Leading Israel's perception of land ownership, this strategy was used in a particular way in the border changes that occurred due to the 1967 war. Before it, the boundaries were almost identical to those of mandatory Palestine except for the addition of the Green Line which was drawn in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip according to the position of military presence at the time of the cease-fire16 (image 3). Now the 1967 war brought about the expansion of the territory that Israel controlled; according to Eyal Weizman, “Soldiers were deployed behind clear territorial boundaries of mountain and water: the Suez Canal, the Jordan River on the Jordanian front and the line of volcanic mounts about 40 kilometers into the Syrian Golan Heights”17. In this particular situation, Israel tripled its presence on land and erased the existence of the Green line, an action that required a supplementary constitutive system in order for it to be

accepted by international law. In other words, presence on land was not enough and another kind of work had to be done.

This system came forward through deliberate decisions of Israel's security cabinet made after the 1967 war and took the shape of a national cartographic project, the new public map. First, on December 1967 a decision to erase the 1949 "Armistice Agreement's Green Line...from all atlases, maps, and textbooks”18 took place. Then, in representing the new picture of reality Menachem Begin ordered the map's colors to be those that portray reality as it is, and advocated for a cohesive

topographical representation; green for a valley and brown for the hills. The use of other colors, to him, “could highlight the two hypothetical things”19, a situation that he did not want to be on display. Finally, he suggested naming the map “Israel- The Ceasefire Lines from June 1967”. To him, adding the word ‘State’ to the name was not necessary, ‘Israel’ alone was a known concept as it is. Serving as a cartographic base for future public maps, these political decisions were crucial in Israel’s imagination of land.

According to To John Pickles in A history of spaces: cartographic reason, mapping, and the geo-coded world, maps have a significant role in providing “the very conditions of possibility for the worlds we inhabit and the subjects we become.” To him, maps do work; when they are read social spaces are produced, not vice versa. Henri Lefebre describes this production as a process where spaces exist but are

24

Lealla Solomon

then modified and reorganized by the state; they are “at once a precondition and a result of social superstructures.” Thus, it is important to understand that social imagination is not only defined by the division of class, or related to the means of production but is tied up with relations to land, where communities are imagined through territorial boundaries. In our case, the land was seized by war, but then was reorganized by the cartographic map, to only then be reproduced by the imagination of its audience. In this imagination, the land was reproduced as whole and empty, as a clean slate for modern architectural configuration.

Conclusions

These three depictions of land possession strategies differ in time, scale, and cultural conditions, but produce the same image of land; the first renders the land as a resource and uses historical production to legitimize ownership of land, the second uses international law and a strategy of physical presence, and the third uses constitutive cartographic imagery to showcase the availability of land and mark it in national institutions. Projected to a certain cultural audience, whether the Jewish diaspora coming back to their land, the 'state pioneer' ready to work the land or the growing child in today's hinterland, they showcase the same wholeness of Israel's land and produce a social order where land is historically legitimately owned, and absent from its previous order; from Palestinian culture and historical significance. Thus, it is not just a fifty shekel map sold in a bookstore and hung up in class, but a cultural systemic enterprise of a national imaginary of land.

So it is not surprising then that Eyal Weizman's map of cheese-like cartographies in Israel's land is not sold in every bookstore, or that the decision to showcase the Green Line in Tel- Aviv's schools produced such political backlash. The tremendous work that has been done to erase the Green Line and the holes from Israel's consciousness and to render the land as a continuous blank sheet of possibilities, has historical roots and evident political and economical significance. Such work entails the deployment of national resources, efficient use of international law, creative use of media, and the clever selection of what to represent and what to erase from the collective memory. Thus, a powerful enterprise as such cannot be dismissed with a single alternative.

In contrast, theories of possession of land can make us rethink how the establishment of a disciplined society is formed. How rendering land as visible, as possible for extraction and exploitation, can produce an army of ready-to-serve citizens; ready to fight for their land, for their right to settle, cultivate and even die for it. To us, the disciplined society, Israel is not a hollow land and never was, it is a continuous horizontal surface of the land, from sea to river, and from Eygpt to Lebanon. We see it as a resource, a blank biblical Jewish land of milk and honey, a land of heroic possibilities, as ready to serve us as we serve it. It is the homeland that was marketed and showcased to us in the turmoil of Jewish European persecution, won by us after the 1967 war, and declared by us through public imagery and physical presence. It is not a question of the binary existence of the Green Line, but of an enterprise of a disciplined society.

11. Efrat, 25.

12. Efrat, 27.

13. Efrat, 14.

14. Efrat, 3.

15. Efrat, 3.

16. Efrat, 3.

17. Weizman, Hollow Land, 11

18. Weizman, 15.

19. Adam Raz, “‘If we give them a map, they will see how big the areas are.’ This is how the green line is deleted,” Haaretz, accessed November 24, 2022, https://www.haaretz.co.il/ magazine/the-edge/2022-08-31/ty-article/. highlight/00000182-f327-d9fb-a1c7fbef5d800000.

25

IMAGE 2 (below): Avigdor Orgad, Map of Israel, 2015.

Land Imaginaries and Israel’s Educational Map

SATURDAY

26

Video by: Kurt Steinhouse

Video by: Kurt Steinhouse

TO WATCH

With footage taken outside the Stonewall Inn the night Biden won, this work explores a moment when revelry overtook the year’s despair and pandemic fever dreams gave way to hope.

SCAN

Written by Jim Lammers and Sabina Sethi Unni

PLAYSCAPES

Every time we attend a public meeting and a parent who shows up because they care about traffic on their block has dragged along their sniffling seven year old who ends up playing on their iPad at full volume and their parent has to inevitably leave the meeting 40 minutes early because their kid is dragging the sleeve of their sweater arm because it’s 8 pm and they haven’t had dinner yet and their science poster board is due tomorrow and they forgot to buy it, we feel terrible.

At their very best, public meetings are designed to keep kids out of the way: offering childcare or vouchers, intentionally held at times when parents don’t need to bring their children, or providing Zoom options. While these interventions are important in reducing the gendered division of childcare labor that prevents parents and women from attending more planning meetings, we want the sniffly seven year old to be a decision maker with agency in planning spaces.

As planners that work in public space activation for children, we see how kids are the most frequent and creative users of public space within the city. For everyone, but especially for children, public space usage subverts the confines of daily routines: more unstructured than the classroom, more communal than the schoolyard, more flexible than the backyard (or tiny bedroom shared with your two siblings). These public spaces, from playgrounds, to sidewalks, to open streets, to vacant lots, to random patches of grass, are spaces full of potential: potential for activity and expression, free of constant adult supervision, fostering independent individual growth, while simultaneously providing a space for building community and building relationships.

Public spaces are crucial to what makes being a kid a kid. But public spaces are never designed by children. When we think of public spaces for children, we often focus on playgrounds, soccer fields, baseball courts, parks, and gymnasiums. A new successful but underfunded (and in our opinion, unimaginative) city-wide initiative, Open Streets for Schools, has created the potential for outdoor public play spaces for children outside of or adjacent to their buildings. While this program is primarily created to reduce traffic fatalities and congestion at pick up and drop off, schools have adapted it for so much more: hosting outdoor classrooms, parades, holiday festivals, community events, vaccination clinics, and environmental justice workshops.

Sabina is an organizer for a nonprofit that tries to create new school streets in neighborhoods of color that lack open space, as most of the schools that have these are white, affluent, private, and in Manhattan. In doing so, she’s worked to apply for school streets and talked to teachers, administrators, PTA parents, CEC leaders, neighbors, elected officials, small business owners, and community boards, but not a single student other than the spontaneous passerby at tabling. In contrast, in a project with PS32 the Belmont School, in the Bronx, Jim is helping the school in building out their own version of a School Street as part of a larger vision of using the spaces in and surrounding their school as part of a “Community Fitness Hub.” Jim’s help in this project was to lead a community engagement process aimed at ensuring this space was built with the community and not for the community. This meant engaging kids in the design process, working with a class of rambunctious second graders through weekly workshops to learn their perspectives and gather their feedback and ideas, centering them as the

28

Public spaces are crucial to what makes being a kid a kid, but public spaces are never designed by children.

protagonist of the design process. These second graders show up to the workshops engaged and invested and full of energy and enthusiasm: with each workshop they continue to learn and grow with the project. Impressively, the students are retaining the concepts and already applying them to thinking about a reimagined space. While the students’ understanding of certain higher level terms and concepts like the logistics of street design and infrastructure delivery may not immediately be translated into formal planning terms (one student aptly described a “hub” as being a space for the Avengers to come

together to save the world), they provide sharp, creative, and tangible suggestions for the future of the project.

PLANNING WITH KIDS SHOULD BE FUN

Between running the workshops at PS32 and working with schools to apply for school streets, we’ve gathered several key takeaways in working with children and positioning them as design protagonists. We also think that these strategies are useful for planning with adults (make sessions exciting! Host them in lively spaces like breweries! Use movement based exercises!). We think that… 1

Planning meetings can be inclusive, important, empowering, radical, and still boring. This is not to say that kids aren't able to understand important concepts with gravity. But, in order to engage students, particularly under 12, we need to create engaging activities that kids find fun and exciting and will want to proactively participate in.

2PLANNING WITH KIDS SHOULD CENTER MOVEMENT AND PLAY

Moving by dancing, running, jumping, being silly and imitating animals, makes the experience fun and approachable. Aside from fun, movement is a tool in the design process that helps kids make connections between themselves and their environment, and tap into their embodied knowledge of place.

It’s beautiful seeing the students at PS32 gain a stronger understanding, awareness, and connection to the built environment around them. It’s creating a more informed project, but embracing the co-design process also empowers students to become urban planners (experts) in their own worlds. Are you designing something for kids? Why not design a process with them instead! Try co-creating a community

3

PLANNING WITH KIDS SHOULD BE IN THIRD SPACES

Instead of confining design meetings to the classroom, pick a space that is fun and different from their traditional learning environment (even if it’s just a different classroom than math class). It’s also important to balance finding a space that students have ownership of, where trust can be built, and where they feel comfortable.

4

PLANNING WITH KIDS SHOULD SPEAK THEIR LANGUAGE

Instead of confining design meetings to the classroom, pick a space that is fun and different from their traditional learning environment (even if it’s just a different classroom than math class). It’s also important to balance finding a space that students have ownership of, where trust can be built, and where they feel comfortable.

visioning performance on the street, playing design charades, writing songs that’ll get stuck in their head, designing coloring books that they’ll take home to their parents, making a board game together, sending them on disposable camera scavenger hunts, taking them into the neighborhood and walking/running/ jumping/screaming around the block - all focused on asking them what they want…

29

If a city has a memory, then the legacy of discarded infrastructural works forms an important part of that memory.

-

Han

Meyer, City & Port

Tramlines and slagheaps, pieces of machinery

That was and still is, my ideal scenery.

- W.H. Auden, “Letter to Lord Byron”

[The design of the High Line was inspired by] the melancholy unruly beauty of this post-industrial ruin.

- Liz Diller

Written by Douglas Woodward

NEW PARADIGMS OF RESIDUAL SPACE

During a brief pause in the intensity of the pandemic in the summer of 2021, Sybil Wa and I led a workshop on the topic of New Paradigms of Residual Space

Bringing together a cohort of students from many of GSAPP’s disciplines: planners, architects, urban designers, real estate students, and curators¹, we took advantage of New York City’s recently enhanced ferry service to visit spaces along the East River routes in East Harlem, Brooklyn, the Upper East Side, and other neighborhoods. For residual spaces in all of these places, the group devised solutions to activate neglected areas and to create new public spaces within and below existing infrastructure, both abandoned and working. They devised these schemes in collaboration, showing the strength of using the most important of GSAPP’s resources—its human capital.

But what is residual space? In her introduction to the Jephcott and

Shorter translation of Walter Benjamin’s Einbahnstrasse (One Way Street), Susan Sontag mused about Benjamin’s Berlin reminiscences as “fragments of an opus that could be called À la recherche des espaces perdus².” Since Benjamin’s study of the spaces of Paris and Berlin, the taxonomy of lost spaces in the city has continued to produce a bewildering array of descriptive terms and examples.

Referred to most commonly in the design and planning literature as “terrains vagues,³ after its coinage in Ignacio Sola Morales’ brilliant 1995 essay, “Terrain Vague,”⁴ the common thread of these widely diverse interstitial spaces is a mis- en- scène that is visually reminiscent of the imagerepertoire of Japanese shonen manga urbanism, Italian neo-realist cinema of the 1950s, and Piranesi’s Carceri, all images dense with an articulate gloom, what Junichiro Tanizaki in his book on

1 The group included a brilliant mix of GSAPP students from different disciplines: Zakios Meghrouni-Brown, Yoo Jin Lee, Yuqi Tian, Dhania Yasmin, Alfonso Jose Larrain, Andrew Magnus, Mariana Kazumi, Majima Ueda, Max Goldner, and Sori Han.

2 Sontag, Susan, from Walter Benjamin, One Way Street and Other Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott & Kingsley Shorter, NLB (London, 1979), p. 13.

3 The terminology and naming conventions describing these spaces is revealing in its mostly negative associations. The spaces have been called “derelict land,” “zero panorama,” empty settings,” “dead spots,” “relingos,” “vacant land,” “wasteland,” “il vuoto” (the void), “urban sinks,” “el space,” “dead zones,” “transgressive zones,” “creuze,” “caruggi,” “superfluous landscapes,” “neutral zones,” “in-between spaces,” “counter sites,” “blank areas,” and “SLOAPs” (Spaces Left Over after Planning). See Patrick Baron, At the Edge of the Pale, for a longer, annotated list with sources.

4 Ignasi de Sola-Morales Rubio, “Terrian Vague” in “Anyplace,” (Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1995) pp. 118-123.

5 Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, trans, Gregory Starr. Sora Books (2017, Tokyo), p.72

30

shadows has called “visible darkness.”⁵

In 2015, working with the Design Trust for Public Space (DTPS) and the NYC Department of Transportation, a group of DTPS Fellows (Chat Travieso—now at GSAPP, Susannah Drake, Neil Donnelly, and Douglas Woodward) co-authored a publication on New York City’s 666 miles of elevated infrastructure that included plans and policy direction for creating public designs in the spaces beneath.⁶

The Under the Elevated project, and a subsequent follow-up the next year with a different group of fellows, resulted in the establishment of a program at DOT that funded designs for what DOT’s head of Urban Design, Neil Gagliardi, called “El-spaces.” An evocative essay in the book by Tom Campanella, a scholar from Cornell, captured both the history and the poetry of these spaces, mainly in a paen to the old elevated train system in New York and the dappled, theatrical spaces it created underneath.

Although my research focus has been primarily on terrains vagues (or el space) beneath elevated infrastructure, typologically these spaces are

multi-spatial in size, configuration, and location. For instance, the Geistbahnhofe (ghost train stations) of Berlin are perfect terrains vagues. We have one of our own here in New York that I wonder how many people know about though they may pass it every day: the phantom 91st Street station on the West Side IRT train line, closed in 1959, whose darkened platforms and ads from ‘50s can still be glimpsed fleetingly from the windows on the #1 between the 86th and 96th Street stations.

The idea that prompted the Under the Elevated project was conversations I had with Liz Diller from Diller, Scofido + Renfro, and work we commissioned Moed, de Armas & Shannon to do on spaces beneath the High Line, which seemed perfect for seasonal use.

There were thirty spaces beneath the High Line and they matched well with the scale of the smaller traditional great European arcades in the geometrical enclosure beneath the train bed. Unfortunately, the West Chelsea area was an exceptionally hot area for redevelopment, and within a year,

90% of the spaces had been acquired by private developers, making the continuous complementary path to the High Line above impossible to design.

31

FIGURE 1 (left) - The High Line juxtaposed with famous arcades; drawing adapted from Arcades, by Johann F. Geist

6 Douglas Woodward; Travieso, Chat; Donnelly, Neil.Under the Elevated, New York City Department of Transportation and Design Trust for Public Space, 2015.

7 Robert Venturi, Complexity & Contradiction in Architecture, Museum of Modern Art Papers on Architecture, (New York, 1966), p.80

A Joint Architecture/UP studio to Genoa, Italy, with Richard Plunz, uncovered a whole new set of narrow, uncanny, ancient, interconnected pathways in the historical center called caruggi and creuze which tied the neighborhood together both physically and socially. The City also studied ways to create public space underneath the Sopraelevata, a longer version of the Boulevard Périphérique or Périph of Paris. The great architect and urban theoretician, Robert Venturi, pointed out in his 1966 book, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, that Residual Spaces are not unknown in our cities. I am thinking of the open spaces under our highways and the buffer spaces around them. Instead of acknowledging and exploiting these characteristic kinds of space, we make them into parking lots of feeble patches of grass—no-man’s lands between the scale of the region and the locality.⁷

And this is a problem we found under most elevated infrastructure: it was often parking, and that was hard to negotiate to move, and when it was able to be moved, the new design for simplicity’s sake often simply used the cliché of converting space beneath the bridge abutment into a skate park, and rarely considered more complex and interesting spaces that could be created.

Finally, let me mention several excellent GSAPP-driven works that have been accomplished or begun in several of these spaces.

First, an award-winning submission for activating spaces in a redesign of the Brooklyn Bridge (“Do Look Down”) by a team of Shannon Hui (’24), Kwans Kim, and Yujin Kim. And forthcoming, a design for this year’s Venice Biennale of a corridor (a frequent typology for terrains vagues) by a team that includes Sarah Abdallah (’23), Michelle Chen (’23), and Aroosa Ajani (’24), along with colleagues from Architecture and RED, under the direction of James Orlando (Faculty) a co-designer of those Astro Boy-like big Red Rubber Boots that are all over the Internet), and Patrice Derrington, head of the RED program and the motive force behind the Biennale effort.

All the cities I’ve visited and many I’ve investigated have some version of terrains vagues, neglected areas that have been used as pop-ups for boxing matches, meeting places for covens, or, famously, as in Paris, areas beneath bridges and bridge supports where clochards slept in bad weather. My interest has grown in nooks and crannies that will support pop-up uses and occasionality—the property of uses that happen and then disappear. These spaces are ideally suited to just that kind of rhythm-the alternation of celebration and neglect.

Boogie-Down Booth by Chat

Boogie-Down Booth by Chat

32

Travieso from the Under the Elevated Project

Douglas Woodward

7 Robert Venturi, Complexity & Contradiction in Architecture, Museum of Modern Art Papers on Architecture, (New York, 1966), p.80

Secret Raves, Boxing, Covens— Residual Spaces Attract Uses that Find It Difficult To Be Accommodated Informally

From Summer Workshop, GSAPP: New Residual Spaces

Boxing Match Beneath Manhattan Bridge Overpass in DUMBO

From Summer Workshop, GSAPP: New Residual Spaces

Boxing Match Beneath Manhattan Bridge Overpass in DUMBO

33

A Japanese Sculpture Studio Beneath a Highway—the Noise of the Traffic Cancels Out the Toolwork

New Paradigms of Residual Space

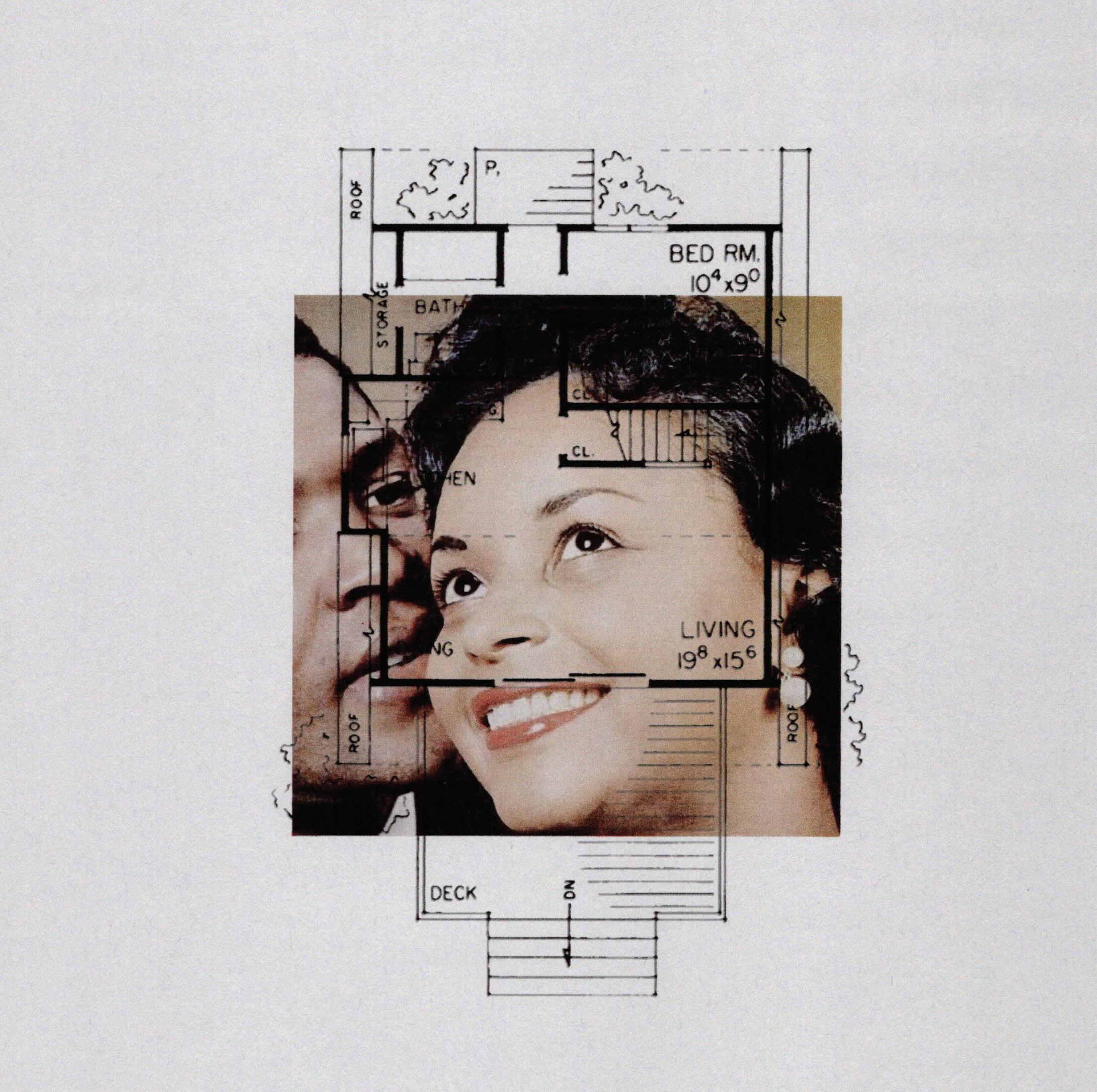

THE NEW AMERICAN (PARADOXICAL) ESCAPE GUIDE: ILLUSTRATED

The New American (Paradoxical) Escape Guide: Illustrated was written for the purpose of helping individuals find freedom from the worldly plights they deem too hard to swallow. This document gives answers to the question american citizens face when deciding which side of the fence to stand on. Should I stay or should I go?, occurs when any form of woe ensues. Deal with the situation or avoid it - run, hide? Choosing the latter is the decision to escape - leaving one place for another; physically, mentally, metaphorically, spiritually, etc. What will it be, Red Pill or Blue Pill?

The following excerpt contains Escapes #49 - #53, of the 99.

Words and photographs by Dakota Smith

34

#49 Escape Intolerance

a

Sick and tired of everyone calling you crazy? Leave those intolerant people behind - surround yourself with like minded individuals that don't have a single contrasting opinion.

b

You're not wrong, they are. Go out into the world and liberate all confined to their misguided thinking. Persistence and tenacity are key when imposing your ideology.

35

#50 Escape Reality

a

Take a step outside yourself and enter the ether - an altered state. Avoid the mundane or situations that weigh the most on the mind, with; music, recreational drugs, books, prescription drugs, writing, psychedelic drugs, quilting, street drugs, etc. Run, attempt to hide from the inevitable.

b

Why leave when the answer is right outside your front door? There's NOTHING a little fresh air and sunshine can't cure. Our ancestors didn't have the technology or luxuries we do today; look how they

36

Dakota Smith

The New American (Paradoxical) Escape Guide: Illustrated

#51 Escape Poverty

a

Sellout - making money for you and your boss is a lot more important than any sum of the little things in life. Working 90% of your life allows you to be completely and utterly free for that last 10%.

b

Make that hobby of yours full-time or even pursue that niche degree you've always dreamt about. Take out that student loan for tens of thousands of dollars. Banks would never loan you the money if you couldn't pay it back. If you do what you love, you'll never work a day in your life.

37

#52 Escape Falsehood

WAKE UP - don't you see through all of these lies?

Your source can't be trusted because my source, that doesn't have a source, says your source is not reliable because they do not agree with the information your source gets from their source.

b

Would the government or media really lie or cover up information to protect the assets of a few and not act in a manner that is in the best interest of the people?

38

a

Dakota Smith

#53 Escape Climate

Are you doing enough to keep your carbon footprint down? Handle your footprint like the impressive corporations do. Use monetary assets to limit monitoring, or purchase commodities like carbon offset credits to disguise the smog.

a

We have reached, and surpassed, the point of no return. It's only a matter of time until it's all underwater and boiling. Pack it up and find the coldest place to live - that will be the last to go.

truth lies somewhere in the middle…

39 The New American (Paradoxical) Escape Guide: Illustrated

b

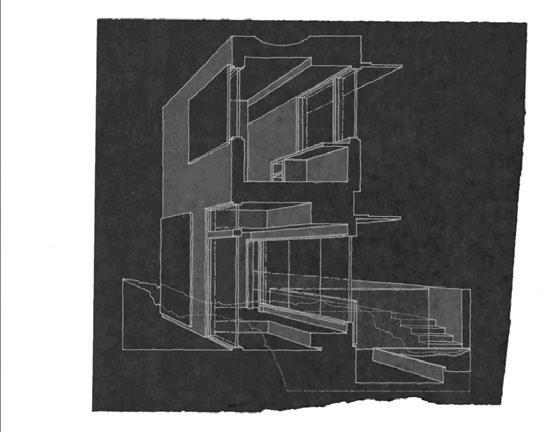

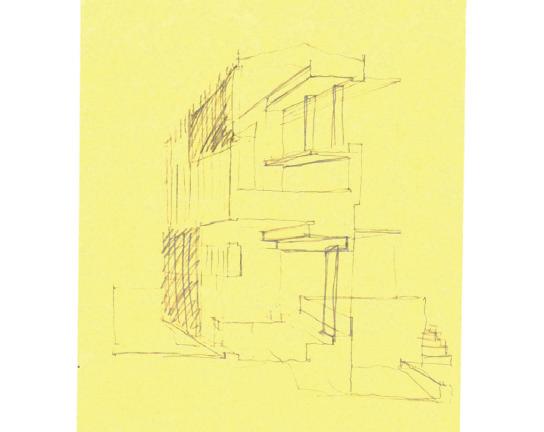

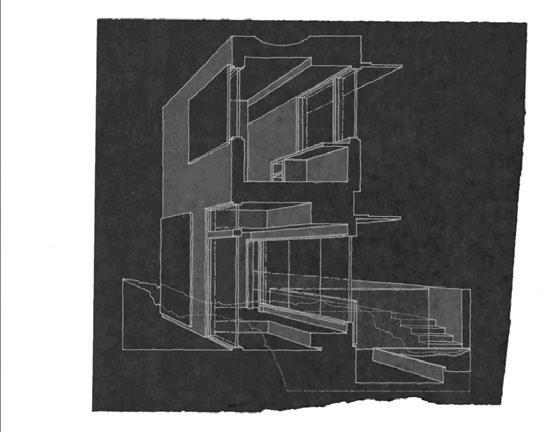

In the fall of 2020, I naively began contemplating the current state of architecture and its various conditions— conditions which, through drawing, stood out and struck me as odd, backwards even, to the architecture which I had studied and came to appreciate. This piece will be framed by studies in drawing and the subsequent internal monologues I had between then and now.

FICTION-SCAPE

Drawings by Jaasiel Duarte-Terrazas

Drawings by Jaasiel Duarte-Terrazas

Drawing, like other forms of thinking and expression, afforded me a chance to contemplate certain attitudes toward the building culture of our time—a culture in which the everyday person becomes entangled. Architectural sections in particular led me to conclusions which began to inform my practice, if I may call it that. The topic of this paper concerns just one of these conclusions, which is that the architectural section, as fiction-scape, is dually radical and canonical in its critique of architecture and urbanism. It affords a radical expression of a fictional reality directly contradicting our own, thus the fictionscape nomenclature, while at the same time remaining canonical in its persistent delegation as the preeminent “architect’s drawing.” Sadly though, architects have malapportioned the section to that-thing-which-thecomputer-spits-out. Where the tool allowed for abstract thinking in search of new fiction-scapes, it is now only an abstract notion itself. Aside from the hegemony of starchitects drafting bizarre buildings—unbeknownst to them and purely as a means to an end— seldom is the section’s realm of fiction in contest with the reality that afflicts our cities; nor does it ever appear to be indebted to the human body and human appropriateness. I will share some things I wrote about tension, thickness, and opportunities for life’s activities, just to provide an idea of what I was thinking and how I came to this

tensions

Architecting, designing—whatever you want to call it—is informed by one’s understanding of habit, ritual, and movement. Why, we should ask ourselves, do our spaces have no opinion toward people and the ways we can move? It appears we amble aimlessly or strictly from point A to point B. A perspectival dimension to a section drawing encouraged me to make a verdict about such things as light and shadow. The section asked me to define what is here and what is out there and especially all the things in between, finding comfort in things which were ambiguous. In contrast, spatial ambiguity is made uncommon and discordant by today's building culture which values speed, plainness, and monotony. As I draw, it is apparent that the spaces I inhabit and the streets I walk disregard mystery and are too honest. It sounds harsh but it’s the reality in many cities. The notion of tension is important because it acknowledges a good friction—one that motivates movement and participation; this led me to some other questions. I wondered why architects don’t talk about curtains much. They imply and define space like a screen but are malleable and bend to the force of wind; positive characteristics, I think. Further, they are ambiguous in form which intrigues and obscures, inviting touch. Perhaps in their unpredictability, the curtain is too much of a liability and requires a strenuous orchestration of movement between things. This is all purely analogy of course, but you see how a section drawing anticipates the conscious crafting of tension and friction, encouraging more meaningful

41

thickness

The section recalls that things can have thickness. Without it, where is compression and relief? Where is concavity and convection—fluctuation? The delineation of a wall has more left to inspire in a section than simply the separation between this and that space. When churned out of a computer, as is common now, the section neglects considerations sensitive to scale and humanness. So I ask, is the invitation to carve a seat or a place to rest too laborious and intrusive? Is it so perverse as to think a surface could inspire any bit of imagination? Moreover, where else do you explore the relationship of things to the street if not in section? Thickness takes only two lines and

the conscious comfortability that stuff happens between them – and that space in between can invite different forms of interface. On another note, architects spend a considerable amount of time attempting to find the right “products”, resulting in stale and flimsy architecture. In this sense, we inhabit buildings which are at once full and empty—full of stuff and empty of meaning. It can feel as though we move through this and that product, over that thing, next to that other thing, without ever framing our experience within the space and participating with it. In regards to these questions and observations, I accepted that there ought to be thickness and so I had to

42

opportunities for life's activities

I stated briefly that the section signals an invitation to question the validity of things, in turn evaluating the potential habits and behaviors of other people. In that time when the pencil touches paper, opportunities are infinite. The straight line is invoked to turn a number of times before feeling right. Hypothetical scenarios and scripts of daily routines should inform these decisions so that simply drawing a wall or barrier no longer fulfills the designer’s duty. As I draw, I recognize that I possess a stubborn refusal to ignore the number of invitations dispatched to a drawer. Why should I not petition for light from above, a bench here or there where one can feel the weight of a surface against their back—or even, a descent toward the dimly lit to then find refuge in sunbathed space further along? Naively, and I mean this in a positive sense, each opportunity can be scrutinized. The section is fiction, remember, and it can be revised, adjusted, and calibrated until the feeling is appropriate. On a final note, before I wrap this up,there is of course that matter of appropriateness informed by a myriad of factors outside of the designers control. I am speaking about things of budget, material availability, and the proximity to the right craftspeople; the things that when in limited availability dissuade critical exploration. To that I say that unless it is drawn and evaluated, can you really be sure of the proper fitting of space in relation to people and to other buildings. And unless you demonstrate to others to believe as you do by bringing forward a new fiction-scape, that which is proper will be dismissed.

What I find so wonderful as I draw is that it's precisely in the milieu between pencil and paper—through the creation of thickness, tension, and opportunities for life’s activities—that I can encounter a fiction suitable for the beginning of a radical new taste for space—space that is saturated with human sensitivity. I hope this doesn’t sound funny, but it's like a conversation where you go back and forth, building upon what was said before and perhaps reiterating until the content of a sentence is fully seasoned and articulate. I find this analogy interesting because language is particularly human and we all participate in its fluid state and tailor it to our feelings, thoughts, and experiences. All of these are suitable forms of being in space. Additionally, it is through drawing that the architect can exercise similar empathy and be mindful of the body in space. The architectural section imparted a critique of the building traditions and patterns that so many loathe by simply offering a means to contradict them. And as lessons on how designers and planners can have more agency in defining the direction of the built environment, it is not a stretch to say that a fiction-scape is a good place to start.

43

[conclusion] Fiction-scape

Regenerative Food Park envisions stormwater management landscapes and new urbanism typologies that promote new integrated living experiences. These experiences synthesize ecological restoration with sustainable domestic affairs, socio-economic relationships, and connected, productive ecologies for improved livelihoods and well-being for all indigenous residents. As the backbone of the proposal, eco-urban infrastructural typologies are proposed that retain clean water and remediate agro-contaminated soils, thus securing sanitation provision and stormwater regulation while envisioning sustainable integrated agro-based living futures.

Submission by Elini Kalapoda

Regenerative Food Parks: A Proposal for the Akaki Territory

[Project Statement]

The problems the Akaki Territory (focus area) faces are mainly due to spatial, environmental, and socio-economic factors such as overcrowding caused by migration, poor water quality because of sewage pollution in rivers near settlements, and displacement from a long-lasting development policy)

The project envisions a new co-op scheme to sustain and implement a new land-occupying framework that restores the indigenous community's water-based ecologies, economies, and cultural practices. Promoting a mutually beneficial framework of touristic development that enables both the local ecologies and the

people (city government and the indigenous residents) to co-exist in the territory creates a more integrated living and thriving future. By doing so, the augmented displacement strategy and relocation scheme to high-density public housing clusters that the government proposal suggests will be reversed. This new land-occupying framework takes the form of a new public space plan (Low ground, Middle ground, and High ground strategy) along the riverbed that integrates agriculture, waste-water recycling, flood adaptation, and informality to leverage ecourban infrastructural typologies that promote equitable socio-economic and environmental futures for the Akaki’s indigenous community.

One of the main goals of this new

public space plan is to create a series of interconnected hydraulic buffers and topographic adjustments (spines that are vacant territories, agricultural terraces, water retention and processing ponds adjustment to safe ground bands for new settlement provision) that will make it possible to see the process of wastewater treatment while providing multi-functional public spaces. These spaces can serve as integrated socio-economic and environmental opportunities for residents in Addis Ababa.

The hierarchies of these topographic manipulations and hydraulic buffers are based on their proximity to either the bottom or the peak of the river valley. The lower part of these hierarchical topographic manipulations involves a

44