DREAMS of UTOPIA

Aspiration, ambition and the endless urge for betterment are all defining pillars of the human existence. Faced with growing turmoil and chaos, one of the most meaningful ways of facing the abyss can be the deliberate choice to be a bit more positive in imagining a better future, whether that’s for your local community, or the world at large. Similarly, even the simple act of setting goals, or seeing hopes manifest after enduring hard work can be incredibly fulfilling.

Whilst utopias are arguably never quite what they seem, and perfection never quite seems within reach, perhaps this shouldn’t stop us continuing to work towards the idealised visions in our head of a harbour of safety and prosperity. In this sense, this issue is an affirmation of the team’s desire to carve out a moment in time to stop and capture a sense of positivity in our work. This issue is our utopia.

It’s been an absolute joy producing this year’s collection of issues, and it feels fitting to end our tenures looking forwards at the society we want to live in, the people we want to be and the values we want to promote.

To our entire team, from the writers and editors to the production team and social media queens, thank you all for your hard work. It’s been a delight to work with all of you and we think that’s obvious from how amazing every issue has been. This is our last issue as the head editors of the magazine and we’ve been so happy to be a part of it. Although we are moving on now, I can assure you that the next team will be just as incredible as the current one. We hope you keep reading this fun little magazine, and never be afraid to get more involved from now!

FUAD KEHINDE- Editor-in-Chief

CATHERINE BOUCHARD- CoEditor-in-Chief

ANA NEGUT-Production Officer

NINA MUNRO- Events Coordinator

OLIVIA SWARTHOUT- Graphics Coordinator

DUNCAN HENDERSOM- Campus Editor

ERIN GRAHAM- Lifestyle Editor

RADOSLAV SERAFIMOV- Science Editor

SAMYUKTA VIDYASHANKAR- Politics Editor

LINA LEONHARD-Arts and Culture Editor

EVAN COLLEY- Showcase Editor

When You’re Smiling…leicester city and the Sensational Theatre of Sport - Evan CollEy

Positivity is All Around Us - Molly Burton

imitation is the highest form of flattery: an evolved utopia - ERIn GRAHAM

the fUTURe iS femAle? - lAUREn lIllEY

fencing Utopia: Borders in an ideal World?SElEn ShAH

Seeking idealism in Politics - RoChElle Chlala

Utopia ABroad- nInA MUnRo

The future Will not Be Built By Human HandsABI WHElAn A future Written in the stars - Zoë “ozzIe” GEMMEll

TcU: The Utopia of Taylor Swift’s cinematic Universe- ana neGU Ț Past futures - RADoSlAV SERAFIMoV

outopos- RICky Blake

Iremember it. It was an eight o’clock kick off, on a warm evening in late May. The sky had darkened to a fine clarity, and it seemed, for what felt like the first night since September of the year before, that the city had finally succumbed to the vacuous, paralysing silence of their own excitement. I remember sitting, perched on the edge of my sofa, doing nothing, refreshing the BBC Sport app, hoping, doing nothing, sitting, refreshing again, and again, and again; it was a strange sensation. Excitement (especially on such a grand scale as this) I often find promotes simultaneously some of the best and worst feelings one has in their emotional arsenal. Sitting there, with my little teenage heart pounding vehemently on my t-shirt sleeve, I recall feeling at once a phrase of euphoric intensity, and at the same time a deeply, deeply unsettling flush of all the anxieties which had been building steadily since the early chapters of the season.

Not only did it feel like the result of the night could impact the city, the country, but more importantly, could reshape sport as a whole. The story of Leicester City’s title winning season was no less than a classic tale of David vs. Goliath. In fact, more accurately in this case, it was a tale of David vs. Goliath vs. Goliath vs. Goliath vs. Goliath vs. Goliath. Cumulatively, Leicester’s title winning team cost approximately £54,000,000. Compared to the likes of Manchester City, who spent the same amount of money on central midfielder Kevin De Bruyne alone, it was safe to say that before the start of the season Leicester’s chances of victory were looking slim. As well as this, only the season before had they pulled off what was called ‘The Great Escape’, comfortably avoiding relegation after being stranded at the bottom of the table for a total of four and a half months. After all this, it seemed totally implausible to suggest that at the end of the season Leicester City would finish top. But against all odds - 5000/1 against to be precise - they did.

So what is it about this tale which seems to have taken history by the scruff of its neck? Is it the stereotypically British bias toward the underdog? Is it the fact that people could very easily see themselves in the metaphor of this great victory?

Is it the concentrated, scriptless drama of it all? Is it the giant fuck you to the immobilising iron clad chains of pay-to-win capitalism which so many people find themselves in constant contest with? I think it is all of this, and so much more, which makes this story one of such profound hope. Despite this story focussing centrally on the theme of sport, more specifically, the sport of football, it is not at all exclusive to fans of the beautiful game. Like most fictitious stories (though this was far from fictitious), we have in this story two things: one, a very obvious narrative structure, relating almost exactly to the typical dramatic procession of Freytag’s pyramid; and two, a relatable, overarching metaphor. And with this, I can only notice how similar the story of Leicester City’s success is to that of the theatrical arts. There was a steady rise in action, a dramatic climax, a victorious denouement, and an easily relatable meaning to it all; but what makes it all the more moving is that, as aforementioned, this extraordinary tale was not scripted. It was very, very much real, and so felt.

I will relate back to the image I cast earlier, about at once feeling the finest highs and the most dreaded lows, and will again claim that it is sport which so often, so efficiently, and so widely captures the emotions which make us all so very human. These can be pain or joy; boredom or excitement; anxiety or elation; but at the heart of it lies a very earnest reminder that sport, like theatre, art, or fiction, can very often evoke within us the very succinct feeling of what it is to be human. Perhaps you might think I am being overly romantic, and perhaps I am. You’d be hard pressed to find a Literature student who isn’t. But, despite this, I can safely say that the sensations which arise from such a dramatic victory, such a true, extraordinary drama, be them physical or emotional, are incomparable to anything I have experienced before, and I’m certain I will never find such a story of similarly grand proportions which is not that of fiction. And so lies my account of the longest, most fulfilling piece of theatre I have ever had the pleasure of spectating. There is a very good reason they call it the beautiful game. For it is beautiful.

by EVAN COLLEY“so lies my ac- count of the longest, most ful- filling piece of theatre I have ever had the pleasure of spec- tating. There is a very good reason they call it the beautiful game. For it is beautiful.”

how can we inject some psychedelia into our grey worlds?

I’ve always found myself saying that sad songs are the best songs, movies that get to you are always about the heavier issues in life, and that the headlines are always bad. Believing that looking for negative things in life puts you on a path of more negativity has never been easier than it is today. You don’t have to look very far to find something negative; whether that’s rising cases, rising sea levels or rising heartbreak in hopeless romantics. Negativity is a pandemic, and most people are almost fatally infected. What’s funny is that people, myself included, find the best ways to justify our gloom to others. We might say “it’s because it’s Monday”, or “January’s depressing anyway” or the best, and possibly most valid: “it’s easier”.

Recently a melancholic friend came to me to talk about their feelings. They were heavy and having a very trying morning, considering going back to sleep for the day. It’s hard not to agree with someone who’s feeling low, it’s hard not to simply say: “life’s a bitch”. But that morning, I knew my friend needed a lift and so I encouraged them to focus on the small everyday happinesses that they find. I listed a few to start my friend off, and it made me realise how little time I take to notice small goodness in my own life. I also couldn’t help but notice how easy I found it to list lots of reasons for that person to be happy today. This small moment of positivity in my otherwise negative mindset was so overwhelming, it nearly made me cry. As carefree children, many of us take little time to notice the badness in the world, content with a pretty flower or a cool looking car. I wondered, when did we stop seeing life as a fun adventure, and start seeing it as a dull inactive experience?

The most pressing question you might be asking is: how can we inject some psychedelia into our grey worlds? As I said, everywhere you look, negativity lies. Is there a way to become bad-blind? If you’ve ever struggled with mental health, you’ve probably heard the phrase “happiness is a choice” one time or another. Mostly, this sounds like an insulting putdown. However, when you think about it, perhaps there’s some truth to this positivity mantra. If you try to find good things in everything, it’s fairly likely that you will find even something small, but even small things grow. When you allow the beauty of life into your eyes, the possibilities are endless. For a lot of people, they might tell you that the good things appear meaningless in comparison to the bad. But I would argue that if you focus your energy hard enough, even the bad things may pale in comparison to a good laugh with a friend, or a really cold drink of lemonade on a hot day. If I asked you to think about your day so far, and write down all the small, good things you’ve seen, you’d have a page full of them.

I often think there’s something poetic about the fact that most comedians go on a stage and make jokes for an hour and a half about life’s most annoying problems. The best part is that everyone laughs. It’s almost an “F U” to the chaos law of entropy that we get together and laugh at our biggest annoyances - laughter really is the best medicine. If you asked me today, how I would work to include more positivity in life, I would tell you it all starts at home, inside yourself. Morrissey had it right: stop watching the news. It lives to depress you and if the news is that important, you’ll find out. Go through your day and find the goodness, rather than the negativity. Instead of being angry you missed the subway, be glad you get time to listen to an extra song before class starts. Instead of looking at the people having an argument on the street, look at the people cooing at a giggling baby. Instead of focusing on the sticky GUU floors, laugh with your friends and enjoy the time you have with them. Positivity is all around us, if we only remember to find it.

by Molly Burton

“If you asked me today, how I would work to in- clude more positivity in life, I would tell you it all starts at home, inside yourself.”photo credit: Danila Chertov via Pexels

“I believe ‘evolved’ utopia has a better ring to it: evolu- tion has worked in our favour thus far (dependingonyour persuasion) and it is the embodiment of improving and adapting to over- come setbacks, which sounds like the kind of world I would like to live in.”

Isthe very future itself just derivative of our past life? Does this mean evolution, rather than originality, is the way forward?

Many would say that something is new if it has never been done before, but what does ‘new’ mean to us in 2022? Does it even carry a meaning anymore? In the context of literature, fashion, and culture, many critics argue that humans simply cannot create things that have not been done before at this stage in our existence – we have been around for hundreds of thousands of years and quite frankly the world thinks we have done everything there is to do - but is that such a bad thing?

The way I see it, the idealised utopia is a collation of all the successful aspects of societies passed, even if they are a little modernised. *cue flying car*. A harmonious world free of violence and social class, where everyone is at peace with their life and the high quality it possesses. It is an evolved world by definition, therefore, is the fact that nothing is ‘new’ in this utopia really stunting the growth of society? After all, imitation is the highest form of flattery. I believe ‘evolved’ utopia has a better ring to it: evolution has worked in our favour thus far (depending on your persuasion) and it is the embodiment of improving and adapting to overcome setbacks, which sounds like the kind of world I would like to live in.

On a more contextual note, fashion is the perfect example of newness vs. evolved-ness. Fashion trends tend to recycle every 30 years on average. Every time they come back to the runway, they have been tweaked or slightly evolved to adapt and meet the demand of ever-evolving human activity. An extra pocket added to the iconic Chanel suit, custom designed to tightly hold a smartphone, a 2022-appropriate facemask lanyard hanging from the Versace blazer designed in 1988 illustrate that fashion is ever-evolving, not ever-inventing.

Everything we see on the runway is a combination of pre-existing objects collated to improve the human experience. In these wonderfully lethargic pandemic times, the surge of indoor-clothing sales and the merging of loungewear and streetwear is the personification of this evolution I am talking about. Considered a ‘new’ trend or a ‘new’ strain of streetwear, it is merely an example of adaptation within societies movements throughout the pandemic.

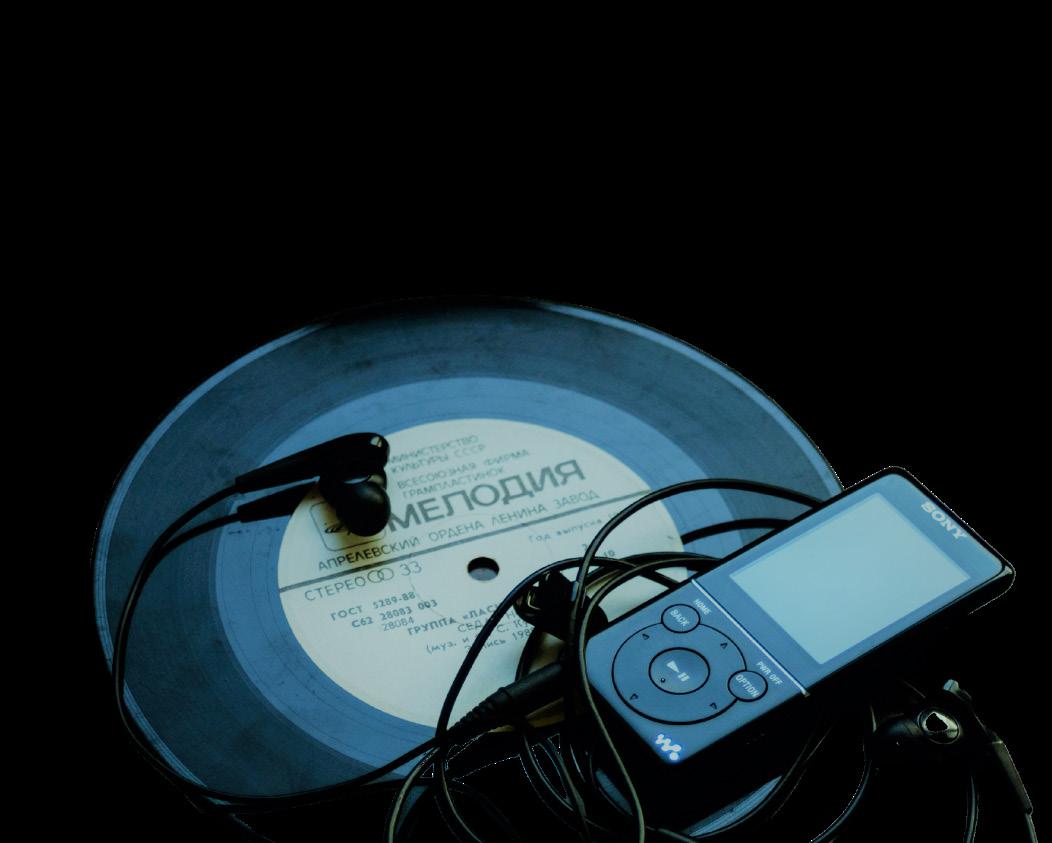

Clearly, evolution does not need to be anatomical to be considered progressive, but I am here to argue that evolution is not a cop-out for originality. Derivation is not avoidable and that should be celebrated – selecting and developing aspects of a more simplistic life gone-by is why we have the Romance languages, why migration and cross-cultural interaction began, and in turn why it adapted itself in tandem with the diversity the world was hurtling towards. Aspects of life we currently consider incredibly modern, like contactless bank cards and apple pay for example, will soon be obsolete in our utopia, considered the grand-parent of some form of all-encompassing eye-goggles that negated the need for the gadgets we consider state-of-the-art right now. It is an insane concept to comprehend as someone born in 2000, but it has already happened to the digital camera, the wired telephone, the DVD, the record player, and the flip phone, which have all faded into the abyss of Ebay, having become relics in our tiny little lifetime. Society is evolving fast, and it’s arguable that nothing that will come is ‘new’ when giving credit to the present world’s existence. When looking at utopia from this perspective, it creates hope for the future of the evolution of our lives – the survival of the fittest (metaphorically speaking) process is implicit but effective

by Erin Graham

When the tantalising phrase ‘world without men’ enters the chamber of utopian debate, what comes to mind is Wonder Woman and her homeland of Themyscira: invoking women, power, efficiency. Although I also think of a more anatomical world without men; AKA learning about hermaphrodites in fifth year biology and being incredibly intrigued by the concept. We all want to imagine a world without men and the immediate success and peace that would follow. However, what is the true reality of female utopia? Conflict? Redesigning patriarchy-centred systems? Health care and reproduction? The list goes on…

Although I simply cannot class myself as a woman in STEM, my understanding of sex and chromosomes is that we all start off as women and then the ‘male’ Y chromosome kicks in. Scientifically, the Y chromosome is unable to repair itself and there is actually a scientific hypothesis that men could possibly, eventually, die out, given falling sperm counts and male fertility rates. However, this won’t lead to the extinction of humanity. Science is a beautifully ever-evolving concept - there are ways. Scientific advances exist which allow two female mice to have a baby that possesses both their biology - interestingly, the offspring will always be female too.

However, this boundary-breaking science is all in reference to sex. The reality of the concept of gender is much more nuanced than this; I cannot picture a female utopia existing without the erasure of the spectrum of gender identities. Those who define themselves as non-binary have their existences consistently undermined, despite the fact that they bring a diversifying unique perspective to the world: in my opinion a nonbinary approach is arguably much more likely the solution to this polarised world than to create a female utopia.

Beyond the science however, a world without men would look radically different: the prison population would drop roughly 80% globally, the political landscape of the world would alter drastically and the need for birth control would become obsolete. It is incredibly likely that this ‘female utopia’ would follow hand in hand with a shift away from the nuclear family, maybe even with the creation of lesbian communes where everyone wears floaty dresses and children play without fear of a scary men coming along to murder them (cue every stereo-typical lesbian cult movie ever)

There is a lot to be said for real life female only communities; there are many women who feel infinitely safer in them, given the statistical-based gender of domestic abuse offenders. But, and it’s a big but, women aren’t inherently angelic creatures, incapable of committing evil, perpetrating stereotypes, or spreading hate. We are humans descended from animals, afterall. The majority of white women voted for Trump; Thatcher was just generally awful to everyone who wasn’t one of her cronies; and Indira Gandhi has a large role in the 1984 Sikh Genocide, to name a few notable ones. It isn’t the presence of men that stops us from obtaining a peaceful utopia, it’s the presence of evil, greed and bloodlust - to suggest women are absolved of these traits is just fundamentally false. Anyone who ever spent time in an all-girls school can attest to the fact that whilst women can often be more empathetic, they can also be mean!

When I dream of utopia, I dream of a world free from violence, hatred, and sadness. I dream of a world full of diversity, on a planet we look after and where anyone is free to celebrate their differences and talents. I don’t know if an all-female society, even the most progressive one, can ever realise a true utopia without leaving someone behind. The raging feminist in me wants to believe that this is something we can create, but true feminism is equality, not creating a closed off community that we claim to be female utopia.

“this boundary-breaking science is all in reference to sex. The reality of the concept of gender is much more nuanced than this”

My grandfather moved to the UK in 1960 as part of the Windrush generation. He left his family and set up life in England, having never met his son (my dad) and not speaking English, to pursue the migrant dream. This dream consisted of economic stability for his family and a hope that his children may live a life better than his own. Two generations later, this dream seems wildly different to my own. I’ve been allowed to dream of a future with infinite possibilities and never felt constrained by the economic status of my family. All of this is a result of the sacrifices that my grandfather made. However, not only did he contribute to improving my life or my father’s life, but he was also one of the half a million migrants who contributed to the economic recovery of the industrial sector in the UK. Despite all of this, my grandfather was met with a lot of hostility throughout his life in England. Many felt that he was taking employment opportunities away from British-born nationals or that he wasn’t entitled to the same protections offered by the state. More than 60 years later, this same story is repeated by many migrants searching for socio-economic stability.

In 2020, the United Nations estimated that there were around 281 million international migrants in the world, equating to around 3.6% of the global population. In January last year, the government introduced a points-based immigration system setting out requirements for anyone wanting to come to the UK to work. The promise of this system, as outlined in the Equality Impact Assessment, published by the Home Office, is to ensure ‘fair and consistent treatment of applicants, whatever their nationality.’ Despite this promise of a fairer immigration system in the UK, the skill-based selection process has been criticised for being an unfair and discriminatory system. Economist Tito Boeri in a study titled ‘Brain Drain and Brain Gain’ found that the sources of highly skilled immigrants are predominantly from developed European or Anglo countries. Although this doesn’t represent discrimination in the form of restrictions on certain countries or ethnic groups, by setting standards that fewer people from less developed countries can meet, this reinforces the disparities that exist in the world due to inequality in education systems, healthcare, and job opportunities. Points-based systems fail to account for the lack of opportunity in these countries and thus reduce the development opportunities for migrants.

Oscar Wilde famously wrote ‘a map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at.’ Describing Utopia can prove to be a difficult task, largely because it’s impossible to find a consensus on what Utopia would look like today.

The term first coined by Sir Thomas More in his book ‘Utopia’, defined it as an imaginary place or state in which everything is perfect, including the political, social, and legal system.

It feels a bit ridiculous asking what are the immigration laws in Utopia? At the risk of overgeneralisation, I think it’s fair to say no one imagines Utopia and thinks of a points-based immigration system. This is because borders aren’t problematised in Utopias. When I think of Utopia, I don’t imagine a place where man owns the land and can dictate who can live where.

Open borders have often been labelled as the utopian image. Author Teresa Hayter argued in the Feminist Review that border controls need to be abolished, ‘to protect immigrant workers from exploitation’ and ‘to enable them to organise and join trade unions’. Karl Marx echoed similar concerns in 1867, writing in a pamphlet called ‘On the Lausanne Congress’ that ‘in order to oppose their workers, the employers either bring in workers from abroad or transfer manufacture to countries where there is a cheap labour force.’ Marx went on to argue that for the working classes to succeed, ‘the national organisations must become international.’ This could be interpreted as a call for open borders.

However, fears over large quantities of individuals moving to wealthier countries and potentially overwhelming the resources available in these countries, are the predominant arguments advanced in opposition to open borders. Author and political writer Angela Nagle argued against open borders in an article published by American Affairs, reasoning that countries should prioritise native-born workers and meeting the needs of their own populations. Nagle discusses how high migration levels often detriment the native working classes and benefit the wealthy through the exploitation of migrant workers. This contrasts with the arguments made by Marx and Hayter, who suggest that open borders are the solution to the exploitation of migrant workers.

The vast majority of arguments against open borders relate to concerns over protecting nationals. Perhaps debates on border politics aren’t entirely centred around migration, but rather centre around xenophobia and the desire to shut off ‘outsiders’ that we view as less deserving of our state resources. Is this selfishness to protect ourselves and accumulate wealth, at the expense of the rest of the world driving us further away from achieving Utopia, or is it a necessary component of the self-preservation of states?

“Perhaps de- bates on border politics aren’t centredentirely around migration, but rather centre around xeno- phobia and the desire to shut off ‘outsiders’ that we view as less deserving of our state

The concept of utopia is usually literary or philosophical, yet rarely is it seen in a political dimension. The idea of utopia however, is the foundation for all political ideologies (I know this is a bit controversial). The concept of a world better for all people and that provides for all people as best as possible is the force behind what political parties try to achieve. However, as we know when we consider the nature of things, the ability to achieve this aim is impossible, and so parties settle for reaching a society where all are somewhat provided for, with some aims achieved.

Furthermore, the ability for any improvement or accountability to come into play is due to the pursuit of achieving this utopia. If any individual or group fails in its aims to make things better, then what is the point of being there? The pursuit and the closeness they can come to achieving anything at all is what keeps politics alive and what keeps parties fueled - well, that, and big bags of cash.

Yet, with this common outcome in mind, do we actually get anywhere close to achieving a utopian state? Simply put, no. However, I don’t think we need to - again, highly controversial. Firstly, the concept of utopia or a somewhat perfect world with provision being fair and just is either unattainable or unsustainable. The idea that humans could put aside key components of our nature like selfishness, over-ambition, and envy is ridiculously optimistic: with that failed moral high ground, a world where people are treated and exist equally cannot occur at a national or individual level. Additionally, the fallacy of utopia, as the nerds call it, would still be prevalent. There is no world without fault as once faults under the status quo (such as lying, thievery, etc.) cease, humans will instinctively find an issue in some other thing.

While it might seem depressing to look at human nature and see an inherent inability to achieve and maintain perfection, the truth is, without the constant out-of-reach promise of utopia, we would have no final outcome to grow, learn, develop towards. Without a goal we can never achieve, we have no incentive, politically, socially, however ‘elsely’, to keep reaching.

Moreover, the incorporation of an ideal world into politics also furthers the level of individualism constant in the field. Due to the subjectivity, even if along party lines, of the concept of ideal, it works in an individual’s favour to push a concept of idealism. The innumerable politicians claiming a better state, a progressed state under their ideas, all benefited from the belief placed in them to achieve that attainable utopia. While idealism may be good for the optimists, most of us want and need a government that can provide us with promises within their capability and competence, which is low as is. It then becomes clear that the idealism in politics is purely intentional, not as a genuine goal, but rather as a means of leaders to achieve power with no follow-up. While accountability and any sort of progress stems from the concept of utopia, its duality lies in that it allows for governments to create overly impossible visions of their society to distract from their inability to provide.

The alternative then? Perhaps a world that allows for all of us to develop as far as we can into our abilities. A world where resources aren’t defined by economic feasibility, but rather by necessity. A world which instead of using utopia as some place that can be vaguely achieved through a political ideology, can be found in the politics of community and a sense of belonging. Basically, localism but with a bit of spice. However, this is simply my opinion. A world where utopia is not a manipulated plaything for politicians to interpret how they please is extremely difficult to conceptualize. Society will always have its flaws regardless of the influence of politicians or overly idealistic ambitions.

The silver lining? We all have the individual capacity to create our own individualistic utopia, even if it is for the span of 10 minutes. The will and freedom we have, as well as experience allows us to develop likes, dislikes, loved ones, dreams (at least hopefully). Thus, very rarely is it that the political forces at play have an overwhelming role in pursuing those things. An exception being psycho-dictators, but we won’t talk about that. For us, as individuals with varying degrees of control over our lives, we have the power to pursue the best of our lives and surroundings. In the pursuit of that growth and that happiness, we achieve a utopia better than a false image of an unrealistic society. If anything can be drawn from this, don’t look to large powers and strict institutions for utopia, look within your own life to find the things that give you a glimpse of utopia.

Anyone who knows me knows that I made going abroad in third yearan integral part of my personality. If you haven’t heard me drop it into conversation, you probably haven’t spoken to me for more than about 3 minutes.

From having four designated playlists for reminiscing on my time spent abroad, numerous posters of my exchange destination up in my room, a scrapbook of pictures printed from my time abroad, and an ABBA obsession - my deep love for the time I spent in Stockholm, Sweden is pretty apparent.

Don’t get me wrong, it wasn’t all kanelbulle and Mamma Mia - there were some pretty difficult points too. On my first night, I attempted to cook in my little studio flat, only to find my oven was broken. I broke down in tears at the thought of having to go to the local supermarket and work out what I could eat without having to cook. I spent the next week trying, and failing, to find my feet - and even sent an email to the Go Abroad Team in Glasgow asking what would happen if I decided to pack up and return to Scotland. Definitely a rocky start if I ever saw one!

Soon, things quickly turned around once I started my courses. I am a person that craves routine, and as soon as I had a lecture/tutorial to attend that I could frame my day around (tragic, I know) things started to feel A LOT brighter. I spent my day down on campus meeting new people and having fika (a Swedish term for coffee break); and my evenings at the local Sportsbar watching football and drinking watered-down beer. These comforts soon became rituals. One of my friends even calculated that they had spent a total of £500 throughout the 6 months we spent in Sweden in the Sportsbar - for reference, a pint was £2.50…

Now, almost 2 years since Miss Rona sent us all packing 3 months early, I still get sad thinking about my time in Sweden and wishing I could relive it. I don’t see it as some perfect utopia that made all my dreams come true, but love it for all its faults and all its joy. I had initially thought that at an English-speaking university, in a cold climate, my experience in Sweden wouldn’t be dissimilar to the first two years I had enjoyed in Glasgow. I could not have been more wrong.

Not only was it much darker, much pricier and much cleaner, it was also SO much more relaxed. My contact hours at university never topped more than 8 hours per week, and I only sat one exam (open-book) the entire time I was there. Seminars were more about discussion than preparation, and every essay I wrote, I was able to choose the subject. The teaching for me was also much more effective. There were no lectures, and no dreaded group projects. Instead, lecturers focused on group discussions within class, and individual work at home. This suited my personality (a little bit of a control-freak) down to a T. Upon returning to Glasgow for fourth year, I found myself shellshocked with how much I had acclimatised to this less pressurising, less competitive environment.

Of course I adore Glasgow (I’m still here, in my fifth year - about to sign up for another 2 years in our Dear Green Place), but I don’t think I would be quite as happy here if I had not embarked on my year abroad. My time in Sweden gave me an enhanced perspective on my life, and my rather cringy takeaway is now: you never know what you have got, until it is gone. That may seem dramatic, in light of the fact that Stockholm has not disappeared off the map - it is still very much there in all its expensive glory - but my experience as a student there is something I will likely never get to experience again. In March 2020, this was a particularly hard revelation, and I spent the first weeks of lockdown very much in a post-Sweden-slump that I thought I would experience until I could get back there. Instead of being grateful for the time I did have, I was angry with what I had lost.

Now, I sit typing this in our beloved library (that’s one thing I’ll give to Glasgow, the library in Stockholm was nowhere near as good), and I am so grateful and appreciative that I went abroad. No longer do I regret my choice to leave early and lockdown at home, I live in the moment for what I did achieve, and what I did enjoy while I was out there. The friends I made remain as close to me as they were when I saw them every day, and they are the kinds of friends I would never have made here in Glasgow. These friendships will stay with me forever (and also give me places to stay when I travel to the US, Australia and New Zealand), and the experience I had in living alone in a completely new country remains my biggest achievement.

At risk of turning this piece into some sort of life lesson/philosophy/jumble of soppiness, I would not change my experience abroad for the world. Moving abroad really tested my patience, tested my bank account and tested my liver (thanks to 7% Rekorderligs). However, it also enriched my studies (finally I could choose an area of law to write about that I was genuinely interested in), allowed me to see a total of seven new cities, encouraged my creativity, and left my heart so very full. If you are reading this and are on the fence about a year or semester abroad - please go. You’ll only regret it if you don’t try it.

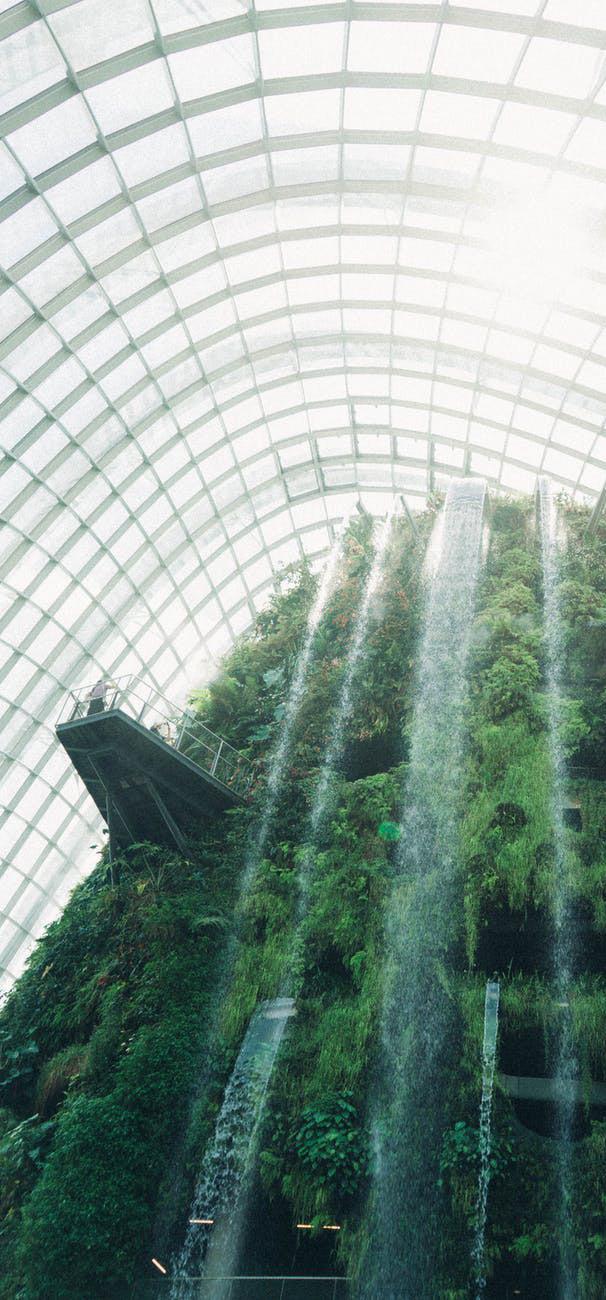

“I don’t see it as some utopiaperfect that made all my dreams come true, but love it for all its faults and all its joy.”Photo credit: Dinara G. via Pexels by Abi Whelan

Is anyone else terrified of the future? Or is that just me? I mean, not in an existential dread kind of way, more of an ‘Oh God, how am I going to get a degree that I can use if everything is just going to be robots?’ kind of way.

Automation can be a very useful tool for scientists. Algorithms can reduce processing times and overall can help to speed up what can otherwise be very lengthy tasks. Rather than wading through thousands of hours of calculations, and thousands of lines of data, a computer can sift through this and figure out the answer in just a few hours.

But that’s not all automation is good for. Imagine, a world where difficult, back-breaking labour can be carried out by machines. I’m sure you’d imagine that this is nothing but a good thing. In a sense, it can be. If we can take people out of dangerous work, that is certainly something worth doing. Just look at the robots that Boston Dynamics create – human-like robots designed to go where people can’t, and clear areas that would simply be too dangerous for us to enter.

Now, I don’t want to sound like the beginning of a ‘Black Mirror’ episode, but nothing is ever perfect, and technology rarely cooperates in the way it was meant to. No, I’m not suggesting that Boston Dynamics’ ‘Spot the Dog’ robot will suddenly start picking up kitchen knives and chasing you throughout your house. It’s something more insidious, and harder to detect. See, these systems are all created by humans. We build them. We design them. We make them. And we are not perfect.

Everything we build has bias. In everything we design, we leave a part of ourselves. And this means we leave a part of our bias. This is a problem we’re already trying to tackle. Apple’s first credit card outright rejected women because of a bias in an algorithm. But there are even more sinister examples than this. Predictive policing algorithms are already showing the systemic racism inherent in our societies by disproportionately targeting people of colour. Policing is something that should not be automated. We should not automate away our freedoms.

If you read about automation for even a minute, you’ll hear grand, sweeping stories about increased productivity, higher production rates, and better use of labour. But is that all? Is that all that we dream of for the future? A late-stage capitalist ‘utopia’ where everyone operates at their most productive at all times, all for their own benefit (or at least, that of their employer).

I’m aware that this is an incredibly cynical view. But, the future needs to be built by human hands. A Python script can’t make decisions the way we can. It can’t make ethical decisions. It’s nothing more than a few lines of code, how can it have the necessary morality to build the future?

The future shouldn’t be built by unthinking, unfeeling, biased machines. It needs to be built by artists and musicians, scientists and engineers. The future needs to be built carefully. It needs to be built by us, not for us.

“A Python script can’t make decisions the way we can. It can’t make ethical decisions. It’s nothing more than a few lines of code, how can it have the necessary morality to build the future?”

It’s always important for us to take a break from the troublesome menagerie of everyday life and allow our minds to find peace in our own utopias. For a fair number of us, this breakaway from the hubbub is achieved by marvelling at the glowing cosmos overhead, sequestered away from the scorch of artificial light. After all, it is only here that we may identify the graceful form of Cetus diving beneath the hooves of Taurus and Aeries, while Corvus’ wings rise elegantly over the Hydra towards the goblet of Crater.

However, reading a sky chart is not necessary to hold a deep reverence for this dark blanket studded with opportunity as each distant twinkle is, in truth, a sun to its own system. The galaxy that we reside within is as vast as it is astonishing, with the asterisms cast upon our atmosphere scattered like marbles throughout space. Even still, that which is visible to our own eyes pale in comparison to the millions upon millions of distant stars and nebulas swirling both within and outwith our galaxy. After all, the Milky Way alone is over one-hundred thousand light years in diameter. As one can imagine, it’s difficult not to feel tiny or insignificant in comparison. Yet, this has not dissuaded scientific minds from exploring the endless possibilities hidden within our own starfield. With the Mars colonisation mission giving rise to revolutionary new interplanetary settlement technology, these distant solar bodies are looking increasingly comparable to our own sun.

With over one hundred thousand million stars to choose from within the Milky Way, it certainly seems inevitable that we would encounter one with a planet within a habitable zone: wherein the surface is neither too cold nor too hot to sustain life. Though, fascinatingly, the star that may host our new colonies may look completely foreign to the Sun we have now, as an ageing star fluctuates wildly in temperature and size, adjusting the habitable zone. For example, when the Sun ages and evolves from a yellow dwarf into a red giant, this region will shift to encompass the likes of Jupiter and Saturn.

Though, naturally, not all planets that fall within the habitable zone are truly habitable. Gas giants such as Jupiter - which both lack a solid surface and contain wildly volatile conditions - make for poor survival choices. Additionally, there are a strict set of survivability rules that apply to terrestrial planets, with those “tidally locked” being excluded. In these cases, the rotation speed of the planet falls in sync with the revolution of the star; resulting in one half of the planet being roasted by sustained light, while the other is left in freezing darkness. Mercury is a partially tidally locked planet within our own system, leading surface temperatures to reach highs of over four hundred degrees Celsius. Further survival prerequisites include fluid water, a circular orbit, and consistent conditions to sustain organic life.

When applying these rules to the approximately one-hundred billion planets swirling around our galaxy, this number is roughly cut by 60%. However, when narrowing this margin down to environments which could distinctly support our own life, this number is cut down to anywhere between six billion to three-hundred million - a meagre 6% at most - of the original planetary numbers.

Yet, even after identification, the issue of even reaching these scattered star bodies is an exceptionally prevalent one. After all, one planet that astrophysicists have positively identified to be earth-like in structure, Kepler-452b, would take our current fastest spacecraft approximately twenty-six million years to reach.

Thus, with all this information combined, one may be left wondering why we expend so much energy chasing these curious specs. When the golden string’s path is billions of miles long, is it even worth fighting the odds to follow it? And, as humanity stands face-to-face with the final hurdle of the Great Filter, we are left asking: why even search for a new Earth if we can barely care for the one beneath our feet?

Fierce criticism levied against the search for a habitable planet often builds to this point – only further bolstered by the rising impact of climate change over the decades. However, when considering the global budgets attributed to fighting climate change ($632 billion) and interplanetary research ($92 billion), a grand disparity can be seen. Furthermore, even if the latter was redirected to the former, it would be a drop in the bucket compared to the true cost of climate remediation. And even still, this makes no mention of cosmic events that may render Earth uninhabitable regardless of our own actions, such as solar flares, meteorite impacts, supernovas, and gamma-ray bursts.

It is important to keep in mind that these two desires are not mutually exclusive wants. We can tackle our own planet’s climate while also scanning the cosmos for our next home - both goals can co-exist, though, only if each is measured in their approach.

“When the golden string’s path is billions of miles long, is it even worth fighting the odds to follow it?”Shlomo Shalev via Unsplash

Throughout her career, singer-songwriter Taylor Swift has put out numerous projects which have not only established Swift as one of the most impactful pop artists of the 21st century, but have also created an intricate cinematic universe. To describe Swift’s body of work as a cinematic universe is to perceive her musical universe as a number of interconnected narratives. For many fans, the escapist utopia of Taylor Swift’s cinematic universe resembles pop culture’s most beloved fantasy worlds. The lyrics, characters, visuals, and motifs in Swift’s work arguably construct a unified narrative about a young woman’s place in the world.

The artist manages to fulfil the specific fantasy of being able to communicate exactly what you wish to communicate using the perfect words and having the rest of the world take your side (as perfectly pointed out by Dana Schwartz, @DanaSchwartzzz on Twitter). Whether it’s expressing your love for the friends in your life, voicing your frustration with misogynistic double standards, or letting your ex-lovers know the specific ways in which they hurt you, the catalogue offers numerous lyrical masterpieces for you to channel these feelings. Through Taylor’s words, the listener comprehends their hidden emotions as if someone were to read their diary out loud. The TCU won’t offer a disconnected narrative: rather than individualising experiences, Swift creates a unified dreamscape of interconnected stories. This form of semi-biographical storytelling constantly references itself, returns to storylines and circles back to its central motifs.

In the TCU, the antiheroine materialises as a sum of multiple individuals, since Swift embraces multiple personas throughout her musical and personal journey. Starting out with a girl-next-door image attached to her country roots, Swift grows and develops into multiple Taylor personas connected to her specific eras in music. The invisible girl from earlier albums contrasts the pop star from her later work who is finally able to address her critics. The edgier Taylor who takes inspiration from having her Reputation tarnished parallels, the introspective Taylor behind Folklore.

Swift initially enjoys conveying an idealised notion of love starring traditional romantic heroes (“Romeo, take me/ Somewhere we could be alone”). Later on, as the artist shifts to pop, Swift’s lyrics manage to fulfil the modern female fantasy of reducing men with social status to immature nobodies. The fairy-tale prince becomes a pretentious, undesirable indie music enjoyer. Through this new approach, Taylor effectively shifts the power imbalance in the aftermath of her painful, high-profile breakups.

g-you//dreams

Swift no longer manifests her happy ending but purposefully throws herself into non-sustainable affairs with bad boy personas “I should just tell you to leave, ‘cause I / Know exactly where it leads, but I/ Watch us go ‘round and ‘round each time”.

A mature Taylor Swift also circles back to old perspectives. After 2017, the songwriter re-embraces notions of triumphant love and sings to a soulmate figure inspired by her real-life relationship. However, the vulnerable maturity present in her more recent lyrical explorations of love tells the story an imperfect partnership. The narrator takes an active role in making a relationship work by navigating its ups and downs and recognizing that she has “never been a natural”. Swift not only expands the TCU through lyrical emotional growth but also by re-visiting eras in her album re-recordings. The cerebral dreamworld of Red (Taylor’s Version) expands the Universe by adding Swift-like nuances and context. A keychain protesting the patriarchy and the image of the first fall of snow now add to the aesthetics of heartbreak, which have always been a specialty of Swift’s. Her focus on the aesthetic sphere paints a utopian image of a young woman navigating heartbreak as if she were an indie film protagonist. Even the uglier aspects of love and loss are portrayed in a magical light— Swift watches the train representing her relationship run off its tracks.

The TCU also contains the POVs of a multitude of narrators outside of Swift’s experience. Perhaps the most obvious example is Folklore’s “Teenage Love Triangle”. The storyline in this collection of songs is narrated by different characters, both female and male, at different points in time. What inspired this article is actually one of the songs contained in the “Teenage Love Triangle”: Cardigan. Taylor uses the voice of Betty, the female protagonist, who reminisces about a lost love. The narrator’s love interest ends up living up to her idealised image of him and ultimately returns to her in hopes of rekindling their relationship. In this utopian reality, the possibility of changing an unhappy ending is palpable. Romantic love is once again given a chance as the protagonists merely need to reconnect by “kissing in cars and downtown bars”. Personally, while listening to this album during one of the many Covid-19 lockdowns, I perceived the lyrics as a reminder of a life before the events of 2020, a time when we might have been able to kiss in cars and downtown bars. In this context of isolation and monotony, the newer additions to Swift’s body of work provided a unique form of escapism.

“Love is so short, forgetting is so long” is a Pablo Neruda line quoted by Taylor in the liner notes to her album Red. I can only be thankful that forgetting is so long, for it has given Taylor time to create this universe.

“In this context of isolation and monotony, the newer additions to Swift’s body of work provided a unique form of escapism.”

Ana Neguț

To be human is to dream. Of a better world, a kinder tomorrow. One that better reflects what we perceive to be right and beautiful about the world, and abandons the failings of the current age to rot shamefully in the crevices of history. The issue with this is, of course, that not all dreams are the same. Lyman Tower Sargent argues that utopias are an inherently contradictory concept, as no society is homogenous, so to dream of a perfect world where all people are united is to dream of an impossibility. But is he right? An exploration into the history of utopias can perhaps yield some answers.

The conception of utopia is as old as society itself. While the term was first coined by an Englishman in 1516, and translating literally to “no place” (despite possibly being meant to evoke the idea of a “good place” as both Greek pronunciations are the same), the oldest recorded utopian proposal is likely Plato’s Republic. And here already we see an unexpected image of what a perfect world might be – one where societal class still exists and is enforced by a powerful state which goes to great lengths to deceive and control its people — a state ruled by philosopher kings reared from the crib for the position, a city capable in politics and war, but one which actively shuns the arts. Is this really a “good place”? To Plato – yes! The point seems to become abundantly clear, that our beliefs of what a perfect world would vary greatly and are thus incompatible with each other. But perhaps this is an outlier. Do trends emerge in utopian conceptions over time that might overrule such strange and terrible flukes?

The answer seems to be yes. What are the characteristics that you think a perfect society should possess? Perhaps it needs to be small, devoid of all the stresses of big city life? Or maybe focused on nature, rural and peaceful, symbiotic with the environment? Or communal, focused on ensuring the good of all is met through collective effort and sharing of resources? And of course, it seems only natural that a utopian society should be non-aggressive.

Even if their way of life is the best one, to spread it to others through conquest would be wrong and to open oneself up to the influence of external forces would risk tipping the carefully balanced scales of a perfect, little world. I do not know if these are the things you would have envisioned a perfect society as being, but many of our species seem to have done so throughout the ages. These themes of naturalism, communal living and localism, if not even outright isolationism, have emerged through many narratives. The beautiful garden of Eden, the hidden Peach Blossom Spring, the communal Datong of Chinese myth, or the utopias envisioned and begun by 19th century settlers of North America.

On the opposite end of the utopian spectrum we have the maximalists – those throughout history that have believed that a utopian world is one of plenty. The Buddhist Ketumati is conceived of as a city full of palaces made of gems where hunger does not exist and none must partake in cultivation. The same concept of indulgent, nigh sinful, plenty is found in the Medieval German concept of Schlaraffenland, where food abounds and one can feast carelessly from dawn till dusk without suffering any harm. A more muted, but just as greedy conception of joy can be seen in the idea of Shangri-La, a hidden valley of eternal joy where one ages incredibly slowly.

The two main types of utopia described above seem to be motivated by different ideals – the first is more humble, but also more achievable: it is a guide to perfection. The second is bolder; it is a dream, a goal to aim for, even if it is unattainable. Utopias have been conceived of in other ways too –as technologically driven wonders, or gender-based worlds where only one gender persists after the fall of the other. They have been used to explore humanity, to drive our dreams to an extreme and envision a good place based on any one of a number of ideologies. Each utopia is a reflection of a dream – a desire motivated by a belief in what must be done to solve the issues of a certain age. To dream is to be human. But no two humans have the same dream. Some dream boldly, of worlds of machinery and glory, others humbly, of villages of community and kindness. No utopia ever arises to hold us all, for no place will be a good place to us all. So remember, it does not hurt to dream – it only hurts to assume that others dream as we do.

“To dream is to be human. But no two humans have the same dream.”

Iam sure that when you first opened this edition of G-You and saw the theme Utopia, images of a paradise land and longing for that perfect society enveloped you. I believe that this utopia is in everyone, and it is something that we all want to try to shape society into. Many will have chosen to come to university and get a degree to help civilisation stride the great distance to Utopia. I want to argue that despite this being a place where most, if not all, would like to be, it is a place we cannot ever reach, certainly not in this earthly realm and not as a whole. There are as many desired utopias as there are people, thus any one utopia could never satisfy more than one individual.

Utopia the word is made of two elements; Outopos, meaning nowhere, and Edopus, meaning the good place. It is because of the latter element that the former exists; because a good place, like the one in Utopia cannot exist for everyone - it is nowhere, so to say. Whenever the notion of a ‘Utopian Society’ is discussed, I, ever the contrarian rationalist, must challenge why this society could never work practically, but also more importantly why it can never be good. Despite everyone having this picture of Utopia, every Utopia is unique to the person who imagined it: an individual with their own wants and ideals. Something that would be a cornerstone in your utopia, dear reader, could be outright banned in mine. For a Utopia to work at a societal level would require consensus that everyone behave in a certain manner, but the laws and values could never be agreed upon by everyone. In an attempt to create a utopia, it is often the vision of one authoritarian individual that society takes (or certainly that is how it has worked in the past). Thus, this society would only be one person’s ideal of Utopia and therefore not utopian, because everyone’s Edopus is subjective.

In Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’, to create the ‘perfect society’ labour is strictly divided amongst the population, the people live their lives in the open and clothing is plain and uniform. All the cities look the same, there is no private property and no freedom of movement. Even in the fictional land of Utopia it is acknowledged that to obtain ‘perfection’ individualism must be removed, which is totalitarian in nature. Looking back through history we can see instances where such policies above have been implemented in order to control society into coherence and submission. For instance, during the ‘Great Leap Forward’ in Mao’s China, people were forced to work the land and were issued drab uniforms for everyday wear. This is a perfect example that to control society realistically, individualism has to be stomped out. (As somebody who likes to express themselves through clothing, such a policy would certainly not be in my utopia). When in the past such policies have been used, they were not welcomed by members of society, with insubordination resulting in extreme punishments; going as far as death, slavery, and an overarching destruction of freedom itself. Whilst it may be possible to have a society where there are strict rules on labour, clothing, and a lack of privacy and private property (indeed there have been such places), that society would cease to be Edopus. Even if the policies were the most egalitarian and benevolent with freedom of expression, movement and privacy permitted, this would mean that people would be free to pursue their own Utopia and therefore not the Utopia of their benevolent leader. That is why draconian punishments have always gone hand in hand with attempts to form a Utopian society.

To conclude, a paradox emerges with any practical attempt to create a Utopian society. Given the two parts of the definition, Outopus and Edopus, an all-encompassing good place free from pain and suffering, want and need cannot exist. I believe it is pointless striving with any realistic expectations to make our reality perfect because there is a natural incoherence with perfection and reality. Utopia is consigned to be an unrealistic nowhere place. However, as I said at the beginning, utopia does exist, although it is confined within our individual selves. We should use ideas from our own ideal Utopias and strive to influence society, through reform, to be more of a good place – of course, remembering that a Morean utopia is not realistic.

“there is a natural incoherence with perfection and reality. Utopia is consigned to be an unrealistic nowhere place.”

//from Greek ou “not” + topos “place”Photo Credit: Aron Visuals via Pexels Photo Credit:

From the standpoint of mundanity, I always knew to draw five lines. A square for the house and a triangle for the roof in red crayon because I didn’t know any better. In the old city, my little houses were praised. Big green ticks on the skeleton houses I drew so well and A’s on their pointy little hats. Well done. What a pretty picture. Excellent. The old city is the barebones of my identity, there I learned about the skeleton houses and their hats, the thick green sharpie lines that surround the empty squares built parks and gardens, and greyish lead pencil shone in metallic looming rectangles that towered over it all. What a pretty picture. Well done. Blue crayon clouds on the paper. Wax, lead, ink. Triangle, square, house. Well done. The old city. It’s yours. It’s yours because you drew it. Stick your name at the top of the paper. Put it in your clearly labelled book-bag, take it home. Why did you crinkle it! Keep it flat! Keep it perfect! What’s wrong with you? Oh what a pretty picture. Well done. Wax house, lead pavement, sharpie trees. Crinkled paper. What a shame. How disappointing. Crinkles, why would you put those there? Who would want that now it’s ruined? Hide it. Move it somewhere no one can see. That was mine. The old city that was mine because I drew it. It belonged to me, hidden in my diary folded in half…that was mine.

The old city has been folded up. Sitting in that diary for 19 years, the paper sticks to the wax and the sharpie is no longer green and the pencil fades like a scar. That fabricated picture in its purest form was truly that. A picture. And so I hid it. I did what I was told. No one likes crinkled paper. I used to love it in the old city. It was colourful and loud and big. It sparkled for me when I poured the glitter. I poured glitter because it was mine. And then I picked it up and it all fell apart bee caws beacose big elephants- B E C A U S E. the glue was too wet and the glitter was too thick and the wax wasn’t sticky enough and it was ruined I ruined it and and the crinkles

The skeleton house was harder to conceal, the red ink of the square and the triangle roof bled over time. I hid what I could. But the ink ran and stained my fingers. And I was told to wash my face because no one wanted to see the fingerprints it left. It was my fault after all, the ink was running because of me and the fingerprints on my face tainted my skin like blooming flowers: pink, purple, red, for days on end. The old city got dark because of my crinkles. It wasn’t pretty anymore. It was so dark.

I didn’t draw after that. My skeleton house was all that’s left, it felt better empty. You could see out of all four lines when it was. I put the glitter away because when it toppled over, the bottle was full of sand. The glue hardened into a thick white brick and my sharpies lost their caps. The old city withered away, and the skeleton house stayed. The darkness stayed. The knowledge of home that I absorbed in my youth was always something I was in search of. I ran from the skeleton house. I ran from the staining red lines. The finger print marks are here, but the lines are in the old city. Folded up in that diary somewhere in the skeleton house with the glue brick and the sand bottle.

The darkness lifted the day I found paint. In an European “we sell everything you would ever need!” shop in the middle of Glasgow on a weather warning day in September, a little set of tubed paints reminded me of the picture. Except despite the pour and the wind, the canvas I also bought did not crinkle. The paint did not run. It was protected by the cellophane and the scarf I wrapped it in, the act of sacrificing my cold neck for the paint I shoved in the back panel of my backpack was fulfilling. Unlike the folded picture that I was told to hide, the wooden frame had a backbone. Paint had screw on caps to protect it where school crayons were set to break me like a promise.

In the white walls of my rented room the wooden structures of canvas protected me and insulated my melting broken crayons. Ageing paintbrushes allowed me to reinvent the stony blankness, there was room to move, to make mistakes with the safety net of white paint and another day to try again. Colours beyond red and blue and green, tone without shape but tone that shaped a home that was evocative and full of life containing a skeleton house that was allowed to breathe. That was allowed to live. Glasgow is the first city I call home, confined to a subway map in thick acrylic on this wooden stretch of canvas. It’s safe and it’s real, a crayon fantasy turned true that I found in my corner of the world. The skeleton house was still inside this rising hurricane of colour. Of course, the lead pencil is still there. Underneath the fullness of the canvas, there are still two shapes. A triangle and a square. But this new city, and this new paint, and this stretched and mounted canvas, will not be reduced to five lines.

by Francesca Lorelei“Glasgow is the

first city I call

home, confined to

a subway map in

thick acrylic

on this wooden stretch of can -

vas. It’s safe

and it’s real,

a crayon fanta -

sy turned true

that I found

in my corner

of the world.”Photo Credit: Mincho Kavaldzhiev via Unsplash

website: https://www.gyoumagazine.co.uk/

facebook: @thegyoumagazine instagram: @gyoumagazine

G-You is produced with the support of the Glasgow University Union’s Board of Management.

Thank

G-You is produced, written and designed by students of the University of Glasgow.We welcome writers of all backgrounds and experience levels and encourage any ineterested student writers to get in touch with their ideas.