Hamilton Historical

Volume I, Issue 2: Spring 2022

Peer-reviewed by undergraduates for undergraduates

Celebrating rigorous studies in diverse fields of historical inquiry

Based out of Hamilton College in Clinton, NY

Peer-reviewed by undergraduates for undergraduates

Celebrating rigorous studies in diverse fields of historical inquiry

Based out of Hamilton College in Clinton, NY

Secondary Title

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Kathryn Biedermann

LAYOUT CZAR

Eric B. Cortés-Kopp

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

SENIOR EDITOR

Emma Tomlins Brian Seiter

PEER EDITORS

Elizabeth Atherton

Brooks Bradford

Carter Myers-Brown

Isabella Roselli

Quinn Brown Philip A. Chivily Erick Christian

Nick Fluty Liam Garcia-Quish Karen Hansen

Theodore Karavolas Timothy Murray Katie Rao

Emma Reilly Maddie Schink Casimir Zablotski

It is my pleasure to introduce our second issue! This issue marks our second year as a publication and my final issue as editor-in-chief. I am grateful to the history majors that make putting this publication together possible, and I would like to especially thank Eric Cortés-Kopp for all of his efforts in launching this publication and ensuring its future longevity. They have been integral to the team and this publication would not exist without them!

Again, we strove to publish a diverse range of content, criss-crossing geographies and time periods to provide critical windows into the past. We also opened up submissions to schools outside of Hamilton College and are proud to publish the work of two students from Scripps College and Kenyon College.

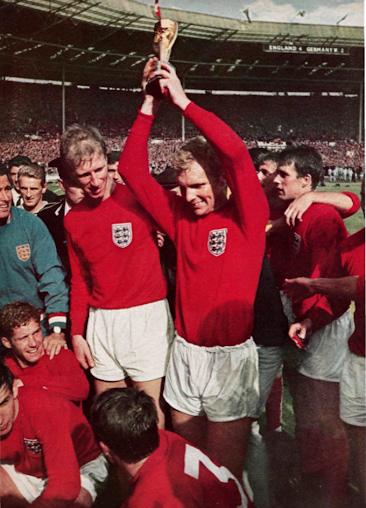

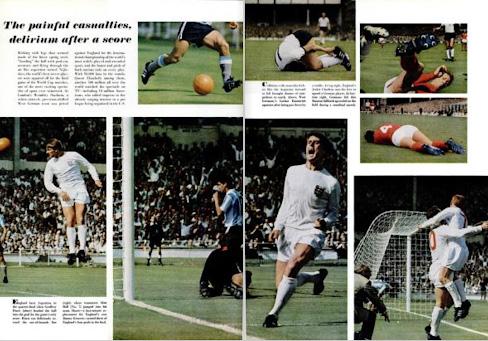

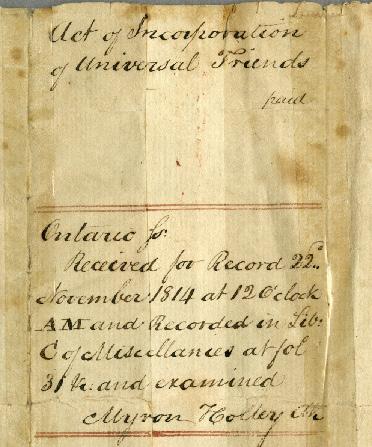

This issue begins in South Africa in the 1950s with photojournalism of apartheid and ends in settler-colonial California with the experiences of indigenous women in the San Francisco Bay Area, with stops in between covering identities of blackness in the early twentieth century in the sport of boxing, American chain gangs, English national identity and the FIFA World Cup of 1966, Russian Orthodox churches in America, and a radical communal society in Revolutionary America.

Thank you for reading and for supporting the Hamilton Historical.

Kindly,

Kathryn Editor-in-Chief, 2020-2022

Drum magazine is remembered as a revolutionary publication that transformed media representations of Black communites in apartheid South Africa, depicting Africans with culture and agency rather than just as victims of apartheid. Drum enabled Africans to become journalists in an industry that had been previously closed off to them, producing some of the most famous Black South African photographers. Although not created with political intent, Drum’s founders quickly realized that catering to Black audiences and depicting Black life in South Africa in the 1950s would be meaningless without addressing the realites of the National Party’s apartheid regime. Drum played a pivotal role in apartheid media coverage, exposing injustices faced by the Black population as well as covering events in the resistance movement. The magazine’s first story that gained widespread attention was an undercover piece exposing unethical working conditions on Bethal farms, setting the precedent of Drum as a publication that was unafraid to take a stance and speak for the African people. This was no easy feat under the strict censorship of the apartheid regime. Journalists often placed themselves in dangerous situations to investigate stories. Henry Nxumalo, for example, once got himself arrested to write the March 1954 exposé “Mr. Drum Goes to Jail.”1 Drum played a pivotal role in apartheid media coverage, exposing injustices faced by the Black population as well as covering events in the resistance movement.

Photography was an essential part of Drum, as the magazine was catered to a largely illiterate audience and inspired by the growing industry of photojournalism in post-war Europe and the United States. Jürgen Schadeberg led photography at Drum and trained several African staff members to become legendary photographers, such as Bob Gosani and Peter Magubane. Drum photographs utilized the international visual language of humanist photography to focus the narrative of

apartheid on the indiviuals it was impacting. This photographic style was a result of Western media influencing Drum, but also occurred because many Drum journalists and photographers needed their work to appeal to international audiences so they could sell their stories to British publications and make a livable wage. The magazine’s Sophiatown coverage also revealed how Drum used the capability of photographs to change in meaning depending on their audience to critique apartheid without becoming a target for government censorship.

Drum’s coverage of Bethal farms in 1952 and of the Sophiatown Removals in 1955 were examples of how the magazine utilized humanist photography to evoke sympathy for the African population without flattening them into victims, representing the persistence of their culture and communities even in the face of destruction.

Drum magazine was first published as The African Drum - a Magazine of Africa, for Africa in March 1951, the third year of South Africa’s Apartheid regime. Apartheid lasted from 1948 to 1994 and was a system of legislation that segregated and discriminated against non-white groups in South Africa. To suppress dissent, the National Party passed several laws that censored the press. The Bantu Administration act, which had been passed prior to apartheid in 1927, included Proclamation 400, which allows for the arrest of journalists who ‘subvert the authority of the state’ by publishing anything about poor conditions in the country.2 Notably, in 1950, a year before the magazine’s first publication, the Suppression of Communism Act was passed. The act defined communism very generally, including any activity promoting disorder or systemic change in South Africa’s industries, society, politics, or economy as well as the encouragement of white/nonwhite hostilities.3 In addition to banning individuals, the act allowed the State Presi-

1 Anthony Sampson, Drum: A Venture Into the New Africa (London: Collins, 1956), 194. 2 Sage Journals Staff, “South Africa’s Censorship Laws,” Sage Publications Inc, Vol. 4, Issue 2 (June 1, 1975), 38. 3 Britannica Editors, “Banning: South African Law,” Encyclopedia Britannica, May 1, 2017.dent to suppress any media publication they claimed to be communist.4

It was in this context of censorship and a white-dominated press that The African Drum, soon renamed Drum, was created. The paper was founded by British South African Jim Bailey and South African retired cricketer Robert Crisp, who were soon joined by Anthony Sampson, a newly graduated Englishman who moved to South Africa for his position at Drum. At first, the magazine did not sell, and Jim Bailey lost money monthly in publishing it. Henry Nxumalo, who would be later remembered as “Mr. Drum,” soon joined the staff as assistant editor, becoming the first Black African member of the staff.5 Nxumalo took Bailey, Crisp, and Sampson to African homes and clubs to hear their perspectives on Drum, indicating the magazine’s early intent to appeal to African audiences. As Job Rathebe, an African undertaker and boxing promoter, told the group, the main problem with Drum was that it was “what white men want Africans to be, not what they are.”6 Rathebe critiqued Drum’s ‘Know Yourselves’ section on tribal history - “we all know ourselves quite well enough… what we want, you see, is a paper which belongs to us… We want it to be our Drum, not a white man’s Drum.”7

To further appeal to African audiences, Drum hired an African editorial board. Crisp was replaced by Sampson as the magazine’s editor. As Sampson put it, this board was “to compensate for” the founding staff’s “whiteness.”8 Sampson aimed directly for an African audience that was not the European-educated elite by moving the magazine away from a dry European syntax to capture “the vigour of African speech.” This round of hires included Joe Rathbe, Dan “Sport” Twala, Dr. Alfred Xuma (former president of the African National Congress), Andy Anderson, Todd Matshikiza, and Arthur Maimane.9 Jürgen Schadeberg, a German photographer, was hired to ‘penetrate’ into African life and capture the realities of townships.

The issue of Drum that first brought it to wider public notice featured its exposé on Bethal, Bethal To-day, published on Drum’s first anniversary in March 1952. After hearing horror stories of the working conditions in Bethal, Drum sent Nxumalo undercover as a labourer to investigate the conditions of African farm workers and the farm’s recruiting methods. Bethal used a contract system that exploited Africans and forced them to work in unsafe conditions without government protection, or else be subjected to extensive punishment

4 Sage Journals Staff, “South Africa’s Censorship Laws,” 38.

5 Sampson, Drum: A Venture Into the New Africa, 17.

6 Ibid. 21.

7 Ibid, 21.

8 Ibid., 24.

9 Ibid., 24.

for breaking their contracts. Drum published an exposé attacking the Bethal farms and the contract system.10 Nxumalo conducted interviews with African workers that allowed them to share their stories of unsafe working conditions, flogging, and torture.

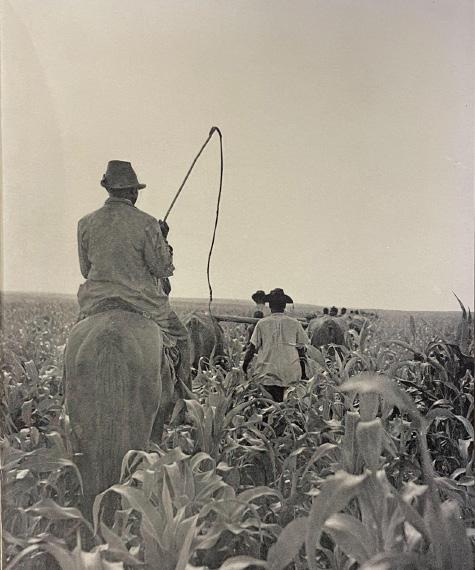

Schadeberg’s photographs accompanied Nxumalo’s exposé, showing Bethal compounds and farm laborers. (Figures 1, 2) The story featured a photograph of an African recruit signing a contract in the Johannesburg Pass Office, where Nxumalo, and Schadeburg following him, had gone undercover as a recruit to re-

10 Ibid., 42.

veal the corruption of the contract system.11 The Bethal story reached a wide audience and received backlash from Hans Strijdom, the Prime Minister of South Africa at the time. It also received some support, such as from the Rand Daily Mail.12 The story led to Senator Ballinger speaking on the labor issue in parliament on behalf of the Africans, and Hendrik Verword, the Minister of Na

the magazine more personable, and was praised for his bravery going undercover to speak up for the greater African public.18 Thus began Mr. Drum’s series of exposés on labor conditions in South Africa, and with it, Drum’s rapid growth in circulation among African readers.19 By 1953, Drum’s circulation in South Africa had reached 60,000.20 Drum had also received international recognition. In December of 1952, Time magazine noted that at “5¢ Life-size monthly, Drum has in less than three years become the leading spokesman for South Africa’s 9,000,000 Negro and coloured population.”21 The magazine’s growth required more staff, and Bailey and Sampson aimed to hire only Africans.22 Drum became its own world, an environment in which Africans had a professional, creative platform on which to collaborate (Figure 3).

tive Affairs, appointing a committee to report on working conditions in Bethal.13 The Institute of Race Relations also corroborated Drum’s account of Bethal, and the article spread knowledge among the public about the dangers of signing unknown contracts.14 Among Bethalians, Drum was being called ‘the emancipating magazine.’15 The intention of the founding staff of Drum was not to create a “narrow paper of protest.”16 However, as Sampson wrote, “without exposing the scandals of such importance to our readers’ lives, the paper would be incomplete and meaningless.”17 Nxumalo’s undercover experiences were shared under the pseudonym “Mr. Drum”, who became an important figure in establishing African readers’ trust in the publication. Mr. Drum made

11 Ibid., 47.

12 Ibid., 48.

13 Ibid., 48.

14 Ibid., 50.

15 Ibid., 49.

16 Ibid., 52.

17 Ibid., 52.

Drum is remembered as a revolutionary publication, which was true in the context of apartheid South Africa. Drum’s coverage of South African events was important in maintaining the culture and dignity of South Africans in the midst of apartheid. However, to achieve this goal, Drum utilized the pre-existing, conventional visual language of photojournalism that was developing in post-war Europe and the United States. The magazine initially adopted these aesthetic, humanistic elements for two reasons. Firstly, after Jim Bailey took over Drum in 1951, he thought that it would be more profitable to model the magazine on Life magazine, which dominated American markets at the time. Jürgen Schadeberg recalls that, at their first meeting together, Bailey told him, “‘I want Drum to become the Life magazine of Africa, and to do that it’s got to have images that work. Don’t forget that most of our market has difficulty reading.’”23 Sampson and Bailey were intent on creating an African newspaper ‘empire,’ inspired by William Randolph Hearst’s success in American magazines and newspapers.24 Secondly, the financial situation at Drum in the early 1950s forced its journalists and photographers to sell stories and images to British publications to earn a livable wage. Throughout his time at Drum, Schadeberg also took photographs for other newspapers to make ends meet. Sampson, too, was making most of his money from articles he sold to the London Observer. 25 The pay for the Black staff was even worse, despite the insistance of its founders that the Drum office was its ‘own world’ untouched by apart

18 Ibid., 51.

19 Ibid., 52.

20 Ibid., 53.

21 Time Staff, “The Press: South African Drumbeats,” Time, December 15 1952.

22 Sampson, 56.

23 Jürgen Schadeberg, The Way I See It: A Memoir (Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2017), 142.

24 Schadeberg, The Way I See It: A Memoir, 142.

25 Ibid., 151.

heid.

Regardless of how much of Drum’s humanist photography was initially inspired by economic incentives, the magazine’s focus on people remained a priority in both its written stories and visual imagery.26 Drum photography utilized portraiture to emphasize the humanity of Africans and spread awareness of the atrocities of apartheid, as seen in the magazine’s coverage of the destruction of Sophiatown. Sophiatown was a multiracial and socially active suburban township, and one of the oldest black areas in Johannesburg. It was deemed a ‘slum’ by the National Party Government.27 For the African public, it held great emotional and cultural significance, and it was home to one of the largest groups of organized African National Congress members.28 In 1951, the National Party announced plans to forcibly relocate the residents of several Black townships, including Sophiatown, to create a whites only area.29 Drum used photography to counter the National Party narrative of Sophiatown. African photographer Bob Gosani’s 1954 “Love Story” features a Black man and woman embracing underneath an apartheid sign that reads ‘native bus stop’ (Figure 4). “Love Story” forces the viewer to confront the realities of apartheid, as represented by the sign, and the humanity and culture of the Africans that persist despite it. Gosani is emphasizing the humanity and dignity of the couple rather than representing them as victims. The couple is well-dressed in European-style clothes, perhaps on their way to one of the 20 churches in the area that was set to be relocated. Drum published photographs such as this to portray Sophiatown’s rich culture and to counter the narrow view of the township

26 Nadya Bair, The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market, (California: University of California Press, July 2020).

27 Lodge, Tom, “The Destruction of Sophiatown.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 19, no. 1 (1981), 111.

28 Lodge, Tom, “The Destruction of Sophiatown.”, 111.

29 Ibid, 122.

as a ‘slum’.30

The focus on people and the use of humanitarian portraiture to give a voice to the South African public continued in Drum’s coverage of the forced removals in Sophiatown. The eviction was scheduled to take place on February 12, 1955 and the African National Congress planned to resist the removals. They intended to release their plan for protest on the day of the removal. However, the National Party banned all public meetings around Johannesburg on the 8th and unexpectedly began the removals the next day.31 Thus, there was no organized resistance when the 80 lorries and 2,000 armed police arrived to relocate the Sophiatown residents to their new homes in Meadowland.32

Schadeberg’s photographic coverage of events focused primarily on individuals, rather than on the demolition of buildings, to create empathy for the residents. In his historic image featuring the popular slogan of resistance, “We Won’t Move”, three men, again in Western-style suits and hats, play what appears to be a game of Morabaraba(Figure 5).33 Morabaraba is known as one of oldest African war strategy games, involving trying to capture the stones, that symbolize “cows,” of one’s opponent.34 Like Gosani’s “Love Story”, this is an image of apartheid, but primarily shows how South African people maintain their culture and dignity despite the oppressive regime.

The photograph “We Won’t Move” was published in a February 1955 issue of Drum titled “What Will Happen to the Western Areas?”, referring to the West-

30 Ibid.,111.

31 Ibid,129.

32 Ibid. 129.

ern Areas of Johannesburg targeted by the evictions.35 This article published ANC statements in opposition to the removals and an interview with Elias Moretsele, the president of the Transvaal’s branch of the ANC.36 The article quoted the ANC: “‘The African people have rejected the removal scheme as a brutal and wicked plot to rob the African people of freehold rights and to resettle them in specified areas in tribal groups… If the Nationalists implement the removal scheme an extremely dangerous and explosive situation will arise.’”37 Moretsele was quoted speaking on behalf of the African population, explaining the grievances of property owners and tenants being relocated to the Meadowlands. He added: “‘People simply don’t want to be herded into camps like locations: it’s against a man’s dignity.” By publishing these statements, Drum actively contradicted the National Party narrative of slum clearance.

Despite its reputation as being the most unfiltered Black perspective on apartheid in South African media, Drum had financial interests in avoiding closure under censorship laws. “What Will Happen to the Western Areas?”, for example, did not make any political statements and did not otherwise call for action beyond the quotations from the ANC official statements and Moretsele’s interview. The “We Won’t Move” photograph, accompanying Drum’s story on the Sophiatown removals, was the main way in which the article encouraged resistance. “We won’t move” was one of the popular slogans of resistance to the Sophiatown evictions, and by publishing this image in the 1955 story Drum gave the Sophiatown residents a measure of control over the narrative about their relocations. This statement, emblazoned across the top of the article, immediately undermined the National party narrative that the relocation of Sophiatown residents to the Meadowlands was in their best interest.

Choosing graffiti as the main representation of the Sophiatown removals was also a symbolic act of resistance. Even after the last residents had been forcibly removed from their homes, their graffiti message, “We Won’t Move,” remained. The legacy of Sophiatown could not be demolished, and Drum chose an image of hope and fortitude to memorialize the Western Areas rather than displaying the failure of the ANC to face down the regime. As John Beaver Marks, president of the ANC, noted in 1955: “‘The slogan ‘we will not move’ laid itself open to a literal interpretation that people will physically resist removal. Yet again and again Congress leaders

35 Nicol has conflicting dates on when this article/image was published (February 1955 or February 1956), but the article was written in anticipation of the Sophiatown removals that happened in February 1955, so I believe it only makes sense to have been published in that same year.

36 Mike Nicol, A Good-Looking Corpse (Great Britain: Tortuga Publishing Limited, 1991), 229.

37 Mike Nicol, A Good-Looking Corpse, 228.

called for restraint and non-violence...Those on whom resistance depended were in doubt as to what exactly they were expected to do.”38 Benson Dyantyi, writing in Drum’s ode to Sophiatown four years later, referred to the graffiti as a reminder of this failure. “The signs that say ‘We Won’t Move’ stand as a mockery to people who thought they could defend their beloved homes.”39 In contrast, Schadeberg’s inclusion of men playing Morabaraba in front of the graffiti arguably emphasizes the resilience of the African people and their culture. The images published in “What Will Happen to the Western Areas?” revealed how Drum used the subjective nature of photographs to appeal to the African and international anti-apartheid movement without being silenced by the government. The “We Won’t Move” photograph is an example of how one image can have multivalent significance. Drum’s African readers would recognize Morabaraba as a game of strategy, and understand the photograph as an image of resistance. International audiences would not recognize the cultural context of the game, but would see this photograph as evidence of the inhumanity of the apartheid government and be outraged by it. The apartheid government discounted this photograph within the context of the article, which they did not view as a threat because it did not make any calls for resistance outside of the careful ANC quotations. The apartheid government also likely felt they were justified in the Sophiatown removals, and consequently did not recognize the image as the condemnation it was to an international audience.

Drum published a final photographic feature on Sophiatown in November 1959, entitled “Last Days of Sophiatown: Big machines and men with picks are beating down the last walls of Sof’town. Take a last look and say goodbye.”40 This feature, written by Benson Dyantyi, was an ode to the old Sophiatown. Dyantyi wrote of the violence and the gangs of Sophiatown, honoring specific community members by name, as well as the “respectable citizens” such as Dr. Xuma and J.R.Rathbe, both of whom had worked for Drum. 41 Notably, Dr. Xuma had served as president of the African National Congress from December 1940 to March 1950, so Dyantyi’s choice to use him as an example of the greatness of Sophiatown was politically poignant. While Dyantyi did not glamorize Sophiatown, he used language with clear emotional intent, referring to Sophiatown as a “she” who was being

38 Lodge, 130.

39 Benson Dyantyi, “Last Days of Sophiatown,” Drum Magazine, November 1959. https://www.baha.co.za/galleries/sophiatown.

40 Nicol, 234.

41 Bailey African History Archives, “Sophiatown”, BAHA.com, accessed November 2021.

“murdered” to evoke an intense reaction from his audience.42 The photographs in “Last Days of Sophiatown”, like Dyantyi’s prose, emphasize the humanity in Sophiatown and the community that is being demolished. Both the text and images of this feature gave faces and names to the displaced residents rather than lumping them together as a collective unit of anonymous victims. However, even Dyantyi’s emotional prose about Sophiatown, follows Drum’s careful example not to directly indict the Apartheid state, or call for any form of resistance. Notably, there was no mention of the national government. For example, Dyantyi wrote of Sophiatown: “she is being murdered.”43 Dyanti utilized the passive voice to focus on Sophiatown, rather than the implied subject that is carrying out the murder, the government. As Mike Nicols wrote of Drum investigative reporting, “the story is dry… But then behind it lays another story.”44 Drum spoke to the African people and encouraged resistance while being acutely aware of the eye of the censor.

The photographs in “Last Days of Sophiatown” were intended to evoke an emotional response against the Sophiatown evictions. Many of the photographs were portraits of children, meant to encourage empathy for the Sophiatown residents. In Figures 6 and 7, three children appear to be playing on the rusted body of a car. The little boy is climbing on top of the metal piece, peering curiously over the edge as though on a playground. He is completely barefoot, which may be representative of his lower class status and also adds to the articulated danger of the scene. The little girl in the foreground has her cheek resting on the rusted car piece, her face contorted in an open-mouthed expression of distress. She is wearing shoes and is properly clothed, as is the little girl in the back left of the photograph. The girl is also missing her right ring finger. Figure 8 appears to be a slightly different angle of the same shot, judging by the positioning of the little girl and the boy’s foot in the top right part of the frame. This shot is dramatically lit, highlighting the girl’s somber expression. Photographing children to evoke sympathy for a group of people is another example of Drum utilizing visual conventions of photojournalism. Humanitarian communication often “portray[s] children as the quintessential embodiment of human suffering.”45 Children are viewed as unequivocally sympathetic figures, used to represent innocence and humanity. These photographs would have been interpreted by Black South Africans and international audiences as deeply sympathetic and a call for resistance

against the government.

While Drum photographs fit into the international visual language of humanist photography, the context of the photographs is what makes them revolutionary. Drum gave Africans the skills and resources to tell their own stories, in a time when opportunities to learn and practice journalism were not open to them and Black voices were being actively oppressed by the government.46 Several of the greatest South African photographers were a result of Jürgen Schadeberg’s mentorship at Drum, such as Ernest Cole, Bob Gosani, Alf Kumalo and Peter Magubane.47 Photographing the realities of apartheid was a rebellious act in itself. Drum photographers and journalists faced threats of bans and imprisonment, constantly risking their own lives and freedom to expose the atrocities of apartheid.

The journalism accomplished by Drum in the 1950s and the opportunities it granted young Africans to enter into the journalism industry were revolutionary in the context of apartheid South Africa. Drum utilized conventions of humanist photography to preserve the humanity and autonomy of African communities amidst a period of unprecedented oppression. Despite its messy inner workings, the magazine successfully became a platform for the culture and grievances of Black South Africans. The magazine’s stories consistently included first hand perspectives from local South Africans. Drum also reached and resonated with international communities, circulating Africa and creating connections with British publications that allowed for stories and photographs of the realities of apartheid to be shared globally. The magazine’s coverage of the Sophiatown removals is just one example of how Drum used photography to make statements indicting the apartheid government while escaping the censor. Photography allowed Drum to preserve and share the community and culture of Sophiatown, countering the National party’s narrative and exposing the inhumanity of the removals to a larger audience. The archives of Drum photography, collected by Jim Bailey with assistance from Jürgen Schadeberg, now provide visual documentation of the experiences of Black South Africans under apartheid. Drum photographs fit visually into the field of humanitarian photojournalism that it was created for, but the context of the risks Drum staff undertook to take and publish these images is what made the magazine legendary.

46 Peter Magubane, Magubane’s South Africa (New York: Random House Inc., 1978) 3.

47 Holland Cotter, “Capturing Apartheid’s Daily Indignity,” The New York Times, Published September 11 2014, Accessed December 2021. nytimes. com/2014/09/12/arts/design/what-ernest-coles-hidden-camera-revealed.html.

Meant to fund French author and anthropologist Marcel Grauile’s expedition to East Africa, a match was organized between Panama Al Brown and Roger Símende at the Cirque d’Hiver on April 15, 1931.1 Intellectuals such as Georges-Henri Rivíere, Paul Rivet, Michel Leiris, and Marcel Grauile sat in the front row. The stage, or spectacle, was finally set. Ten rounds of three minutes each to determine the winner. Before the bell, Al Brown addressed the crowd. “I am boxing,” he said, “to contribute to the success of the expedition and to increase the knowledge about and understanding of Africa.”2 Roaring applause followed. His opponent, Roger Símende, remarked, “I am boxing because I like the sport and also to earn money for my family.”3 Silence followed, and an uneasy tension filled the arena. The crowd braced with anticipation as these two fighters prepared themselves for battle. Brown’s biographer, Eduard Arroyo, recorded that the fight itself was “brief and indecisive.”4 At the end of the second round, Brown sent Símende to the canvas with a left-right-left combination. The third round barely lasted thirty seconds, as Símenda, still hurt, stumbled and could not get back up. In the midst of a roaring, chanting crowd, the referee declared Brown the winner via KO.5

The nature of the Panama Al Brown and Roger Símende boxing match encompasses a broader historiography of sports and race beginning at the end of the nineteenth century. Collective fears about the rising power of non-whites were often expressed through gendered metaphors of the body. As a result, competitive sports appeared to offer the perfect arena within which to disseminate the defensive physical stance of the white

1 Bennetta Jules-Rosette, “Introduction” and “An Uneasy Collaboration: The Dialogue between French Anthropology and Black Paris,” In Black Paris: The African Writers’ Landscape, 28.

2 Benetta Jules-Rosette, “Introduction” and “An Uneasy Collaboration,” 28.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., 29.

5 Ibid., 27.

man’s burden. More recently, scholars have researched how the transnational sporting industry of boxing encapsulated the growing struggles over the racial and imperial order. At its core, boxing involved unscripted, visceral hand to hand combat between two individuals who embodied race and nationhood in the eyes of their fans. Armed with no weapons except leather padding on their fists, boxers fought to outlast one another for the amusement, admiration, and admonishment of the public. The spectacle of boxing was a space of heightened white surveillance, where the black prizefighter was subverted of their identity and characterized by their physicality against the white man.

The 1938 rematch between black heavyweight G.I. Joe Louis and the German champion Max Schmeling elucidates the boxing spectacle as a space of heightened white surveillance. David Margolick researched this highly publicized heavyweight fight and illustrated how this spectacle reflected notions of nationhood and struggles over the racial order. Margolick sifted through newspapers detailing the lead-up to the Madison Square Garden event, one of which remarked: “Louis represents democracy in its purest form: the Negro boy who would be permitted to become a world champion without regard for race, creed, or color. Schmeling represents a country which does not recognize this idea and ideal.”6 Joe Louis had the chance to represent the ‘freedom’ of the United States and defeat the man endorsed by Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. On the contrary, Schmelling had the chance to prove Aryan superiority, embedded in the Nazi regime. This boxing bout, elevated to a global spectacle, therefore implicated both the future of race relations and the prestige of two powerful nations. Margolick contended, however, that Joe Louis’s purported identity in the boxing spectacle was riddled with contradictions and tensions. While Louis’s beatdown of Max Schmelling illustrated the resistance and superiority of

6 David Margolick, Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling, and a World on the Brink (New York, 2005): 7.American values over Nazi fascism, it likewise signified the emergence of the black race in the modern world, an uncomfortable thought for white Americans and Nazis alike. As he pummeled Schmelling’s body and face, writers and broadcasters began characterizing his black physicality and thus marked his black identity with racist tropes. For example, Hype Igoe of the Journal-American commented on the match: “‘I felt the punch!’ So terrifying was the sound–‘half human, half animal’–that some fans reached instinctively for their hates, as if Louis was about to come for them too.”7 Joe Louis was lauded as an American hero in his victory over Schmelling, but this image was largely still a façade. Racist tropes continued to mark his presence as he fought under white surveillance and analysis.

Lauren Rebecca Sklaroff expanded on the tensions of G.I. Joe Louis’s constructed identity through an analysis of media propagated by the War Department leading up to the 1938 rematch. Sklaroff contended that media such as posters, magazines, movies, and boxing exhibitions throughout American military bases were essential to the War Department’s careful construction of G.I. Joe Louis, which would reduce wartime tensions between black and white Americans without “press[ing] for structural change” or “alarming white Americans.”8 Sklaroff examined the “God’s side” poster, which was not only one of the most famous images of a black man in World War II, but also a “rare depiction of a black man in an aggressive pose.”9 At the time, the few posters featuring black soldiers stressed racial harmony and sacrifice, therefore downplaying suggestions of racial militancy. As an “established” war hero, then, G.I. Joe Louis transcended the “acceptable imagery of black men.”10 Representing a soldier prepared for combat–one of the strongest symbols of American masculinity–Louis was able to subvert embedded racial ideologies.11 In propagating this image to hundreds of cities, the government blurred the color line by featuring Joe Louis as detached from racial politics. Paradoxically, this visual detachment of G.I. Joe from racial politics indicated one of the War Department’s most politically suggestive stances. The “God’s Side” poster underpinned Sklaroff’s broader argument: although state officials manufactured portrayals of black inclusion in contradiction to the realities of American discrimination, they could not always control the meanings these symbols conveyed.

Charlene Regester accentuated Skarloff’s argument that manufactured portrayals of blackness could

7 Ibid., 298.

8 Lauren Rebecca Sklaroff, “Constructing G.I. Joe Louis: Cultural Solutions to the ‘Negro Problem’ during World War II,” Journal of American History, 959.

9 Ibid., 980.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

not be completely controlled by the producer through her research on the early twentieth century transformation of the black prizefighter in cinema. Regester utilized scholar Chris Holmlund’s argument that “blackness was already coded in terms of spectacle,” contending that the combination of the violent, combative nature of boxing and the savage, primitive tropes of black men reinforced the efficacy of African-American prizefighters as actors because their bodies became objects of both danger and desire.12 Yet while these African-American prizefighters served as marketable commodities for the profit of the movie industry, their presence often resonated within the identities of the black American community. Regester detailed G.I. Joe’s involvement in multiple films, such as The Spirit of Youth (1938), arguing that the white press and public reception of these spectacles differed from those of black Americans. While critics believed Louis, “as an actor, lacked sex appeal,” the black spectators identified with Louis, as he “battered a train of white opponents on screen…[who] were symbols of the white privilege and power that had been denied to blacks in the real world of the 1930s.”13 Regester concluded that cinema manufactured a spectacle of boxing beyond the sport which transformed the black prizefighter into figments of Hollywood’s imagination as objects of desire, danger, and derision. Regester therefore contended that black male spectators who gazed at black prizefighters could identify with the symbolic power these athletes possessed to combat the racism projected upon them as black males.

Sklaroff and Regester’s research illuminated how G.I. Joe Louis’s carefully manufactured figure unintentionally became a symbol of promise for black Americans. Unlike some white people, “who viewed the fights in the context of Louis’s rise to boxing stardom, many black individuals saw themselves and their futures in [G.I. Joe].”14 Although Louis and his manufactured symbol did not directly address discrimination or segregation, he still represented hope and pride in the communities of black Americans hoping to rise from their oppression. His figure likewise alluded to a global diaspora of black prizefighters whose racial identities were created and subverted in these heavily monitored white spectacles of boxing.

Another one of these boxers whose racial identity was manufactured by white spectators was the Senegalese boxer Battling Siki. The French media’s characterization of Siki’s boxing abilities, particularly in his match against the white Frenchman Georges Carpentier,

12 Charlene Regester, 2003, “From the Gridiron and the Boxing Ring to the Cinema Screen: The African-American Athlete in Pre-1950 Cinema,” Culture, Sport, Society 6 (2/3): 270-271.

13 Ibid., 282.

14 Ibid., 970.

illustrated the tensions of Siki’s ontology: an inversion and perversion of the natural man, and an abstraction of the colonial Other. The press labeled Siki as the “dark child-savage of the jungle.”15 Carpentier, the “idol of France, with his dazzling white skin,” was expected to “[turn] Siki from a swaggering figure into a badly scared coloured boy.”16 Louis Golding described Siki’s style as “big, strong, and ugly, there was a terrific power in those long, pendulous arms of his which could be unleashed with devastating effect when he was roused. Skill and science were beyond the scope of his limited intelligence, but many a slogger has risen to the heights of the game.”17 Vergani likewise recounted that Siki’s aggression illustrated “the primeval savagery of his race, dormant since the dark and distant centuries.”18 Although Siki rose to brief prominence in France after defeating Georges Carpentier, the manner in which he was described and marked illustrates a clear subversion of his identity in the surveilled spectacle of boxing. His very popularity hinged on his performance of the masculine aesthetics of black primitivism, and he accentuated his exotic physicality and sexuality to entertain white Parisian fans. As the ‘dark child-savage of the jungle,’ then, Siki acted as a proxy for the French to clarify their own knowledge of empire, imperialism, and colonialism.

Siki was one of many black prizefighters who inspired French sports enthusiasts to publicly reflect on their own conceptions of race, manhood, and the positioning of Western empire in the modern world. Theresa Runstedtler specifically examined the exploits of African American boxers in France during the early 1900s as a window into the transnational struggle over the terms of race and modernity. Runstedtler focused on the experiences of famed black American heavyweights such as Sam McVea, Joe Jeannette, and world champion Jack Johnson who ventured across the ocean for economic mobility and personal freedom. Public speculations of these heavyweights took the form of boxing exhibitions, posters, and newspapers, which elevated boxing as a spectacle in which the black prizefighter was analyzed and objectified. Rundstedtler argued that while these black heavyweights were stripped of their identity in order to satisfy French fascinations, they likewise articulated their own definitions of the New Negro and critiqued the backwardness of white supremacy.

The heavyweight trilogy between Sam McVea and Joe Jeannette illuminated the consumption of blackness as a means to regenerate white French-hood, and the French imperial nation. Parisian spectators seemed

15 Gerald Early, 1988, “Battling Siki: The Boxer as Natural Man,” The Massachusetts Review, No. 3: 457.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid., 455.

18 Ibid., 458.

to “revel in the African American competitors’ imagined brutality to their own effete and effeminate modernity.”19 Caricatures of the two fighters leading up to their first match emphasized that they possessed an unrivaled, animalistic strength. One cartoon reduced them both to white eyes and lips against a black background, and others feature the same markers of savagery, including, “dragging knuckles, exaggerated lips, jutting jawbones, and overhanging foreheads.”20 Moreover, one popular French cartoonist depicted McVea as a menacing gorilla. Parisian intellectuals and spectators emphasized their blackness in order to construct the spectacle between the two prizefighters: a test of blackness against blackness, which sportswriters promised would “be more gruesome than any other fight in the capital.”21 Runstedtler argued that Parisian reactions to the fight exposed racist, simian assumptions about the viciousness of African combat. The first fight, ending by a decision rather than a knockout, caused outrage by French spectators who felt robbed of their dramatic, exotic expectations. McVea and Jeannette were both removed of their humanity, and seen as objects showcasing the limits and extremities of blackness–masculine strength, endurance, and aggression–for the fascination and entertainment of the Parisian gaze.

The second McVea-Jeannette fight evinced the vehemence of these racist assumptions and characterizations undermining the Parisian ‘celebration’ of black prizefighters. To ensure a definitive result, the fight promoters arranged a “match au finish,” for a purse of 30,000 francs. Guaranteed to test the limits of black physicality, “the fight could only end in knockout or submission, rather than by referee’s decision.”22 Evidently, McVea and Jeannette delivered, treating the audience with an action-packed match which continued for forty-nine rounds until a “battered” McVea threw in the towel.23 French sportswriter Georges Dupuy remarked, “the rematch...was not only the most beautiful we have ever seen in France but perhaps the most terrible and the most savage in the history of boxing throughout the world.”24 Despite McVea and Jeannette both being marked by signifiers of blackness in the build-up to both fights, the French press accentuated Jeannette’s biraciality after his victory in order to display the triumph of “white civilization” over “black savagery.” For example, Dunoyer de Segonzac declared, “I admired Joe Jeannette, the ‘yellow’ black, a learned boxer, more scientific than

20 Ibid., 66.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid., 67.

23 Ibid., 68.

24 Ibid.

his pure black brothers.”25 Another Parisian sportswriter had juxtaposed Jeanette, the “Greek athlete,” with McVea, “the eldest son of a grand barbarian king.”26 French writer Tristan Bernard argued that McVea’s submission had exemplified the “lack of perseverance in the [black] race,” as McVea’s inability to go in for the kill stemmed from “a certain timidity” and the “habit of subservience also characteristic of African people.”27 The deliberate interpretations of McVea and Jeannette’s blackness, evinced by anthropological critiques and analysis, bolstered the notion that the black man–regardless of his physical superiority–still needed the guidance of white civilization. Therefore, the amazing physical feats of African American prizefighters in these constructed spectacles supported the French mission civilisatrice

African American pugilists still managed to use the French public’s cultural embrace of black masculinity to launch a transnational critique of the white man’s burden, regardless of the inherent dehumanization by the French in these boxing spectacles. Their special access to the foreign press and to performance venues enabled them to forward their own protests of the racial and imperial status quo.28 For example, the French sporting weekly La vie au grand air (Life in the Great Outdoors) provided its first installment of Jack Johnson’s life story in January 1911, titled, “Ma vie et mes combats” (“My Life and Battles”), which continued for five months.29 Johnson’s memoirs exemplified that his transnational career and working-class origins enabled him to develop a particular critique of Western modernity.30 His narrative criticized white American negrophobia while alluding to the global contours of white supremacy through his transatlantic experience. Moreover, Johnson refashioned the negative legacy of black slavery into a story of triumph. Thus, Johnson’s detailing of his ancestral history legitimized black history and questioned justifications for the white man’s burden. Even though he attained the financial trappings of sport success and celebrity status, he continued to identify with the urban culture of the black proletariat. His experiences spoke explicitly to the challenges of working class African Americans, casting them as agents in the fight against the color line.31 Runstedtler affirmed Johnson’s memoirs as a quintessential text of African American exile and protest, where he defined not only his own identity, but also the identities of the transnational black diaspora.

In applying Runstedtler’s research to the work done by other scholars, one can explicitly see the emerging counterculture of blackness in the very spaces where black prizefighters were subverted of their identities. As the historian Davarian Baldwin argued, black boxers ‘became ironic positions of strength in the creation of New Negro consciousness’ not only in the United States but across the African diaspora. In particular, black sporting participation ‘exalted personality, sexuality, and the physical exterior as the expression of new race consciousness,’ one that was decidedly masculine, militant, and anti-bourgeois.32

Furthermore, one can see how this emerging counterculture not only forced white reflection of the global color line, but also exposed the diminishing power of white nations and empires. Despite the state’s effort to commodify G.I. Joe Louis as a black American patriot, they could not control the fluidity of his symbolism. In some ways, Louis was reconciling the double consciousness W.E.B Du Bois had described: the tension of possessing both black and American identity.33 His elevation to the global spectacle of boxing exposed the inconsistency of blackness and Americanness, and the legitimacy of black ancestry in the United States. While this construction was an effort to propagate particular notions of blackness, it was likewise public affirmation that black people could not be ignored as American citizens. Fighting for the United States as a black American, then, Louis’s symbol of black patriotism urged some white Americans to question the orthodoxy of white nationalism.

Looking at Siki’s triumph through the lens of Runstedtler’s research, then, one can see this match as a metaphor for the unravelling of white imperial control. Although Siki’s triumph over Georges Carpentier piqued French admiration and fascination, his performance nonetheless exposed underlying Parisian and global concerns about the growing powers of black Americans and African colonial subjects. One French columnist warned against showing the Siki-Carpentier fight in the colonies. Additionally, a columnist for the Literary Digest dubbed Siki “a dark cloud on the horizon,” declaring, “the prestige of the white race, in danger now as never before in recent history... is threatened by the victory of ‘Battling Siki.’”34 Siki’s defeat of Carpentier even led French officials to oppose the proposals allowing black soldiers to serve as officers in white French regiments.

The white reaction to Siki’s win over Carpentier foreshadowed the attempts by France, the UK, and the

32 Ibid., 62.

United States to completely ban him from boxing. His flamboyant lifestyle and relations with white women, afforded by his performance in the boxing ring, set off a chain reaction of white efforts to undermine him. Effectively embittered by Carpentier’s fall, French boxing officials saw their chance to stop the Senegalese fighter after he was caught in a minor tussle with boxer Maurice Prunier’s manager, Fernand Cuny. The French Boxing Federation (FBB) slapped Siki with a nine-month suspension and stripped him of his French light heavyweight title.35 To make matters worse, exaggerated tales of Siki’s allegedly criminal ways flooded the French press, as Parisian journalists accused him of, “selling drugs in Montmartre and fraternizing with an underage French girl.”36 Siki’s ban extended to other countries, with the British Home Office, the New York State Boxing Commission, and Italian boxing clubs soon prohibiting Siki from fighting on their soil.

However, in the very spectacle in which Siki was objectified, degraded, and eventually repudiated, Siki emerged as a transnational symbol of nonwhite resistance. The Senegalese parliamentarian Blaise Diagne brought Siki’s case in front of his white colleagues in the French Chamber of Deputies.37 Diagne declared, “These men who are as French as you are, though they are of different color, have a right to the same justice as you,” and cautioned his fellow deputies about the “danger of giving the impression that France had two unequal forms of justice–one for white Frenchmen, and one for colored subjects.”38 Among black Americans, Siki’s struggles also sparked protests and conversations about racial prejudice. As one black reporter exclaimed, “Siki stirred up no racial feeling when he fought with shot and shell against the Boche [German soldiers] when England’s back was against the wall.”39 Marcus Garvey likewise took issue with Siki’s plight, arguing that his predicament validated the Universal Negro Improvement Association’s (UNIA) international platform: “We have always held to the opinion that there was absolutely no difference between the Englishman and the Frenchman and the American when it comes to the race.”40 Claude McKay similarly took issue with Siki’s treatment and critiqued the conservative nationalist agenda of the black bourgeoisie in the United States and France. “The black intelligentsia of America looks upon France as the foremost cultured nation of the world,” McKay noted, “the single great country where all citizens enjoy equal rights before the law, without re-

35 Ibid., 247.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid., 249.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid., 250.

spect to race or skin color.”41 McKay maintained that the white backlash against black prizefighters such as Siki was ultimately about the need to maintain a compliant black workforce. In situating Runstedtler’s work with the story of Battling Siki, one can see the emergence of black counterculture stemming from the spectacle of boxing, albeit a heavily white monitored space. Furthermore, this black counterculture recognized the treatment of Siki by the French, British, and the United States, thereby exposing the extent of imperial control and the myths of racial toleration.

Runstedtler’s research likewise exposes the imperial undercurrents behind the East African expedition’s boxing spectacle. Al Brown and Roger Símende essentially participated in a primitive ritual, one which glorified exoticism and dramatized blackness for the purpose of financial gain. Not only did these black men have to fight for their place in the ring, but they were also viewed as anthropological specimens. This expedition thus provided useful justifications for the exclusion of people of color from mainstream politics and society, as “fitness” for citizenship became rooted in a muscular, white, male ideal.42 The accepted ideal remained that of the “superior” white male body, even if this racial fiction could not always be sustained in the ring.43 The boxing spectacle, particularly with Brown vs. Símende, therefore, functioned as an example of justifying colonial control. Without rules and restrictions, the black man would become too unruly and powerful to command. Brown and Símende, uprooted from their identities, were thus passive objects in the advancement of the white French mission civilisatrice, and representative of the white fear of unraveling imperial control.

While not explicitly “political,” black boxers embodied a New Negro masculinity which emerged from the spectacle of the boxing ring and radically critiqued white supremacy and exposed the continuous atrocities of imperial control. Joe Louis, although constructed as an apolitical figure of black nationalism, became highly politicized by Americans as he blurred the color line. His defeat over Schmelling, and by extension the ideologies of the Third Reich, prompted white Americans to question the orthodoxy of white supremacy while likewise garnering the hope and support of the black American community. Battling Siki, while marked with racist tropes in the ring and faced with corrupt expulsion from the sport, became a symbol of transnational black resistance in the United States and colonial Africa after beating the Frenchman Georges Culvier. Joe Jeanette and Sam McVea exposed the extent of the French

41 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

fascination with the brutality of the black body. After enduring the fights for the appraisal of French fans, they quickly discovered the limits of French racial tolerance. Although their physical performance of “primitive black manhood” made them international celebrities, they refused to allow this limited version of blackness to define them.44 Instead, Sam McVea, Joe Jeanette, and many other black prizefighters used their ambivalent position to forward an explicit critique of the global color line. Even as white officials tried eradicating the black global vision inspired by boxing’s rebel sojourners, the vision had already influenced the ideas of activists throughout the black diaspora. A black counterculture, one which peaked during the New Negro movement, manifested in the white-supremacist boxing spectacles showcasing the brutal fighting abilities of black prizefighters. Regardless of how these black prizefighters were characterized by the white press, or unsuccessfully controlled by the War Department, their highly publicized travels assisted in the New Negro’s fight with the global color line.

In June 1912, penal reformer E. Stagg Whitin published “Convicts and Road Building” in an issue of the periodical Southern Good Roads. In this article, Whitin wrote of the “good roads movement,” and how it had become identified as “the movement to take the prisoner out of the cell, the prison factory and the mine to work him in the fresh air and sunshine.” This so-called good roads movement advocated “that bad men on bad roads make good roads,” and consequently that “good roads make good men.”1 Within a few sentences, Whitin captured the fundamental idea that drove much of the South to use convict labor on public roads. Around the turn of the twentieth century, this use of convict labor produced sprawling state highways. The driving force behind this application of convict labor was the Good Roads Movement, which marketed convict roadwork not only as an efficient means of public development, but also as a humanitarian penal reform. The impact of the Good Roads Movement, however, was not penal rehabilitation, but rather the successful rallying of enough social and political capital to stimulate public development. As a so-called progressive movement, it did not overcome the cruelty and abuse of the southern penal system, focusing more on development rather than reform. The movement’s penal reforms perpetuated a state of subservience among African Americans in a post-bellum nation, becoming a functional replacement for slavery in the modern age. Before the Good Roads Movement, however, prisoners worked under the convict leasing system.

Under this system, state governments leased out prisoners to private employers as workers, who labored under the supervision of armed prison guards. In exchange, state governments received hundreds of thousands of dollars from private contractors leasing convicts. Convict leasing appealed to southern states

most impacted by the Civil War. The war decimated many southern prisons, and with no money to erect new penitentiaries, leasing was an attractive option.2 Furthermore, to the state and society, convict leasing was convenient. It transferred responsibility for thousands of prisoners from the state to private entities. Leasing generated millions in revenue for state and local coffers, funded public infrastructure like roads and bridges, and lowered taxes for the average citizen.3

Leasing also worked as a system of racial domination and control in a post-slavery society. A number of trends developed during the age of convict leasing: longer sentences translated into a larger convict population, the number of people sentenced rose drastically, and prisoners became almost entirely black. Convict leasing even incorporated elements of slavery. Convicts leased in Alabama and Texas, for example, were classified by their level of labor, such as “full,” medium,” and “dead” laborers. Slaves were classified under a similar system. However, unlike slavery, convict leasing offered no proprietary protection.4 Reports of poor food, abysmal sanitation, brutal labor, and inhumane punishment defined life on the chain gang. In 1920, black convicts working on a North Carolina chain gang wrote to the governor that they were “beat up like dogs” and that their overseers “work us hard and half feed us [and] beat us with shovel and stick.” In North Carolina’s Johnston County, Wiley Woodard, a black convict, wrote to the state’s commissioner of public welfare. Woodward said that although he had “made a mistake” on the job, it did “not call for the management of this camp to treat me and my race as dogs,” and that his camp kept convicts “at the point of a gun and threats of [the] lash.” A critic of North Carolina’s chain gangs wrote to the governor stating that although

1 E. Stagg Whitin, “Convicts and Road Building,” Southern Good Roads, June 1912, 16, https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p249901coll37/ id/13775. 2 Christopher Adamson, “Punishment after Slavery: Southern State Penal Systems, 1865-1890,” in Social Systems 30, no. 5 (June 1983): 556. 3 David M. Oshinsky, “Worse Than Slavery”: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 57. 4 Matthew J. Mancini, “Race, Economics, and the Abandonment of Convict Leasing,” The Journal of Negro History 63, no. 4 (October 1978): 343-345.“the State may be getting some good roads out of this system,” the chain gang must be abolished as it “savors too much of slavery times.”5 Like slaves, convicts labored under inhumane conditions and received brutal punishment. Unlike slaves, however, convicts were cheap and plentiful.

They were also lucrative. In his 1880 book The State of Prisons and of Child-Saving Institutions in the Civilized World, prison reform advocate Enoch Cobb Wines reported that — for states without convict leasing — roughly half of penal administration costs were paid by prison-generated income. Taxpayers paid the rest.6 In comparison, states with convict leasing generated more than three-times worth of income over costs. Convict leasing also provided businessmen with the labor to build railroads, chop timber, and amass profits. Convict leasing allowed states to maintain control over emancipated African Americans and was a significant source of wealth to businessmen and politicians. For half a century, these two mutually reinforcing factors fended off multiple attempts to abolish the system.7

Convict leasing in the South faded towards the end of the nineteenth century. The railroad boom transitioned into a period of consolidation in the North, and not expansion in the South. This eliminated the need for a large convict labor source to work the railroads. The depression of 1893 further hampered the viability of convict labor in major business ventures. The price of leased convicts also rose drastically. In 1907, for example, a lessee in Georgia paid roughly $100 per year in upkeep, in addition to the price as stated in the leasing contract. The total cost came out to be roughly $670 every year, or two dollars every day. This was similar to the price of free labor.8 The rising costs of leased convict labor was caused by the rising prices of key commodities. Between 1890 and 1910, the Wholesale Price Index for goods produced by convict leasing like farm products and building materials rose from 50.4 to 74.8, and 46.8 to 55.3, respectively.9 The value of convict-leased labor would have increased in accordance with the rising costs of its produced commodities. Furthermore, the legalization of subleasing after 1899 likely exposed the system to forces of the free market. This increased the pressure

to pay costs close to the going rate for free labor.10

As convict leasing struggled to turn a profit, there was a growing appreciation for the cost-effectiveness of “chain gangs.” A brutal form of forced labor, chain gangs — composed of mostly African American convicts — were constantly chained together while working, eating, and sleeping.11 Southerners valued chain gangs more at the same time that convict leasing fell out of favor with businessmen. The abolition of leasing left a vacuum to fill, and chain gangs offered an attractive replacement. The South again filled a vacuum originally left by the abolition of slavery — first with convict leasing, then with chain gangs.12 A key difference, however, was the ideological force driving chain gangs. Coming from the abolition of convict leasing — and during the Progressive Movement — chain gangs were conceived as a reform that demonstrated penal humanitarianism, but also economic modernization.

The American Progressive Movement was multifaceted. Activists ranging from suffragettes fighting for the right to vote to trustbusters wanting to regulate monopoly and competition all fell under the banner of American progressivism. The movement was tied together by a belief in using state power to enact social, political, and economic change. This opposed conservatives, who tended to discredit using state power, for example, on behalf of workers, small business, and the poor. Conservatives instead preached a philosophy of Social Darwinism, asserting that people were subject to the same laws of natural selection as plants and animals. Therefore, they believed in survival of the fittest for society. In short, social darwinism. Progressives, comparatively, committed themselves to generalized political action untethered to any single cause, driven by a robust sense of morality, and the belief that human effort could make positive change.13 “Anyone who has a serious appreciation of the immensely complex problems of our present-day life,” wrote noted progressive Theodore Roosevelt in a 1901 edition of McClure’s magazine, “and of those kinds of benevolent effort which...we group under the name of philanthropy, must realize the infinite diversity there is in the field of social work.”14 Roosevelt further elaborated that “no hard-and-fast rule can be laid down as to

5 Convicts to Governor, March 7, 1920; Wiley Woodard to Kate Burr Johnson, August 10, 1925; Urban A Woodbury to Governor Bickett, February 8, 1920, in “Good Roads and Chain Gangs in the Progressive South: ‘The Negro Convict is a Slave,’ by Alex Lichtenstein. Journal of Southern History 59, no. 1 (February 1993): 92.

6 Enoch C. Wines, The State of Prisons and of Child-Saving Institutions in the Civilized World (Cambridge: University PressL: John Wilson & Son, 1880), 94.

7 Mancini, “Race, Economics, and the Abandonment of Convict Leasing,” 339.

8 Mancini, “Race, Economics, and the Abandonment of Convict Leasing,” 348.

9 U.S. Department of Commerce, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, Part 1 (September 1975), 200.

10 In regard to convict leasing, subleasing was when a leaseholder gave their lease to another party with the permission of the original holder. Mancini, “Race, Economics, and the Abandonment of Convict Leasing,” 352.

11 Jaron Browne, “Rooted in Slavery: Prison Labor Exploitation,” Race, Poverty & the Environment 17, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 79-80.

12 Mancini, “Race, Economics, and the Abandonment of Convict Leasing,” 349.

13 Glen Gendzel, “What the Progressives Had in Common,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 10, no. 3 (July 2011): 331-334.

14 Theodore Roosevelt, “Reform Through Social Work,” in McClure’s Magazine, March 1901, 448.

the way in which such work must be done.”15 To create change and reform society, Progressives wanted to wield state power in the name of the public good, and not just what was good for big, private business.16

In the South, progressivism behaved differently. Southern progressivism exalted business. The coming of Southern progressivism was heralded by a few changes in the social landscape that took place by the end of the nineteenth century. This included the rise of industrialization, urbanization, and the growth of a new middle class made up of business organizations and other professional groups. This diversified the South’s economy, and induced a new spirit of commercialism that exalted business like never before. The people and institutions with influence and authority shifted from the countryside to towns and cities. This urban environment produced a new middle class of merchants, bankers, lawyers, technicians, and others.17 These professionals came together in trade associations, bankers’ groups, and chambers of commerce. Apart from elevating standards within their professions, these groups also turned towards collective action in the name of reform, and — in the case of race relations — control. These ideas of reform and control were firmly rooted in regional progress. Accordingly, Southern progressivism expressed itself in the desire for economic development and rehabilitation of the region. These desires were encapsulated in the “New South” creed, a vision for regional development that deemed economic progress capable of resolving the South’s socio-economic distress.18 This vision for a New South, however, would lead Southern progressives to provide African Americans with a modernized version of paternalism — referring to the infringement on the rights and personal autonomy of an individual under the guise of benevolence — and racial control in a post-emancipation society.19

Progress in the South largely meant improved schools and churches, real estate, and booming industry.20 Southern psychologist Lyle H. Lanier commented that this idea of business progressivism was reinforced by a barrage of “newspapers, magazines, radios, billboards, and other agencies for controlling public opinion,” and that it did not take much to learn “that progress

usually turns out to mean business.”21 This ideology of business progressivism asserted that prosperity could be achieved through spending and development. This desire for growth led to popular crusades in education, public health, the treatment of criminals, and good roads.22 In the South, North Carolina led this movement for business progressivism. During this period, North Carolina developed the leading southern state university, expanded its education and public health services, and embarked on the most ambitious highway expansion program in the region. By 1928, the North Carolina State Highway Commission had spent more than $150 million dollars on a state road system of over seven thousand miles. The state ended the decade eleventh in the nation in terms of total mileage of surfaced roads.23 This expansion of state roads originated with the “Good Roads Movement,” a wave of southern business progressivism that, in the words of Georgia governor Joseph Brown, meant “the closer binding of the common interests of the farmer and the merchant” towards the common goal of an expanded highway system.24 Around the twentieth-century, there was much to gain with good roads. The creation of the first American gas-powered automobile in 1893 promised significant revenue to those with roads. Gasoline and automobile taxes became a source of income to states.25 By 1928, for example, revenue from gasoline and automobile taxes had covered the costs of North Carolina’s $150 million dollar highway expenditures.26 Before southern states like North Carolina could achieve such a lucrative highway system, they needed a robust source of labor. Conscripted labor would not suffice.

Until the 1890s, every U.S. state used an American ad aptation of the corvée — a French word referring to a system of temporary unpaid labor — to supply workers for public infrastructure, and especially roads. Appearing as “road duty” in law books, the corvée system functioned as a tax of labor, not money.27 In 1883, North Carolina legislated that overseers supervising roadwork “shall have power to call out all the hands” they required, and that these conscripted free laborers would “be liable to all the penalties and punishments

21 Lyle H. Lanier, “A Critique of the Philosophy of Progress,” in I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition, ed. Louis Decimus Rubin (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 123.

22 Tindall, A History of the South, 225.

15 Ibid., 454.

16 Gendzel, “What the Progressives Had in Common,” 333.

17 Grantham, “The Contours of Southern Progressivism,” American Historical Review 86, no. 5 (December 1981): 1036.

18 Ibid., 1037-1038.

19 Ibid., 1048.

20 George B. Tindall, A History of the South, vol. 10, The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967), 223.

23 Ibid., 226-227.

24 Henry B. Varner, “Good Roads Notes Gathered Here and There,” Southern Good Roads, March 1910, 17, https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/ p249901coll37/id/13802.

25 Peter Wallenstein, Blue Laws and Black Codes: Conflict, Courts and Change in Twentieth-Century Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 16.

26 Tindall, A History of the South, 226-227.

27 Wallenstein, Blue Laws and Black Codes, 22.

now imposed by law for failure to perform road duty.”28 State judiciaries rejected claims that “road duty” was involuntary servitude. They asserted that statute labor was simply another public duty, like serving on a jury.29 But this conscription service, while cheap, often resulted in poorly built roads. Speaking to the North Carolina Good Roads Convention in 1902, William R. Cox, a former Confederate general, decried this “antebellum style of working the public highways” for being as ineffective as “were the old militia ‘musters’ to the development of actual soldiers.”30 A massive expansion of state highways required a more reliable labor force. In 1887, North Carolina law books listed an act “to provide for the working of certain convicts upon the public roads of the State.” Under this act, convicts whose sentences were imprisonment in county jails or the state penitentiary could be sentenced to “hard labor upon the public roads” by county judges.31 Cox declared that there was legislation “in our State which already enables us to use convict labor,” and that he believed “it should be more widely used than it is at the present time.”32

The 1887 law came as a result of growing calls to replace the South’s old system of conscripting free men to work the roads. In 1901, geologist Joseph A. Holmes published “Road Building with Convict Labor in the Southern States,” a study sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Holmes reported on chain gang practices throughout the South and suggested that they exerted a positive influence on convicts. Holmes wrote that a prisoner who “has injured a community through the commision of crime” should be made to “benefit the community which he has injured.” He said that “the belief prevails that perhaps the best way in which a criminal can benefit the community he has injured is in helping to improve its public highways.”33 But Homes’ report stood out for its suggestion that “this out-of-door work not only improves the physical health of the convicts” but that also their work on the roads “improved their general character and prepared them for better citizenship.”34 Holmes declared that chain gangs would improve not just society, but also convicts as well. Rather

28 North Carolina General Assembly, Laws and Resolutions of the State of North Carolina, Passed by the General Assembly at its Session of 1883 (Raleigh, 1883), 190.

29 Wallenstein, Blue Laws and Black Codes, 22.

30 William R. Cox, “Good Roads and their Relation to Country Life,” in Proceedings of the North Carolina Good Roads Convention, ed. J.A. Holmes (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1903), 36.

31 North Carolina General Assembly, Laws and Resolutions of the State of North Carolina, Passed by the General Assembly at its Session of 1883 (Raleigh, 1887), 354-355.

32 William R. Cox, “Good Roads,” 36.

33 J.A. Holmes, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Road Building with Convict Labor in the Southern States, (1901), 319.

34 Ibid., 326.

than continue this campaign for chain gangs, however, Holmes accepted a position at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis to direct its mines and metallurgy department. This humanitarian conception of chain gangs would be further pitched as progressive reform by Holmes’ colleague, mineralogist and northern progressive Joseph Hyde Pratt.35 As an automobile owner and real estate investor, Pratt saw value in a grand state highway system. To construct such a system, Pratt needed capital, civil engineers, and more labor than could be provided by the counties’ supply of convicts. Pratt’s plan required state support and control of all major road construction. To garner such support, Pratt drew on Holmes’ assertion that roadwork helped convicts rehabilitate themselves, and he began the campaign for “good roads and good men.”36

Pratt did not invent the concept of using convict labor on roads. He rather emphasized that convict road crews could be a method of penal reform. This idea grew in popularity. In 1907, penal reformer Charles R. Henderson published a report describing outdoor penal reforms in England, Australia, and Switzerland. Henderson stated that outdoor work — like farming and canal building — was “excellent for the health of the prisoners” because nature itself kept “the atmosphere free from all contagion” and germs.37 In 1908, periodical editor Samuel Barrows published an article entitled “Convict Road Building,” which described the experiences of eighty convicts working on Colorado highway. Barrows stated that the number of escapes had dropped, indicating that “as soon as this outdoor life, living in tents, had improved their physical and mental condition, the desire to escape almost entirely disappeared.”38

To take advantage of the popularity of outdoor penal labor, Pratt embarked on a campaign to market the chain gang as a vehicle of penal rehabilitation. He went on the speaking circuit, presenting papers and delivering presentations throughout the South. He presented a paper on convict labor for roadwork before the national Good Roads Association conference in St. Louis, Missouri, and at the Southern Commercial Congress in Atlanta, Georgia in 1910 and 1911, respectively. Pratt then spoke about the benefits of state control over public roads at the National Good Roads Congress two months later in Birmingham, Alabama. Then, at the sixty-third annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., Pratt delivered a

36 Ibid.,133.

presentation titled “Convict Labor in Highway Construction.” In this address, Pratt gave the moral and economic rationale for “good roads and good men.”39

Pratt stated two principles, that a convict should “compensate society for his crime,” and that a convict should “be in better condition physically and morally at the end of his sentence” before returning to society. He advocated for rehabilitation through labor that benefited communities, and questioned what labor “will be for the best interest of the state and the convict himself” in order for all to benefit. Pratt refuted the idea that any convict labor “that is in direct competition with free labor,” citing the potential for conflict. He rejected methods like convict leasing on the grounds that “the work is largely in the interest of individuals and private corporations.”40 He asserted that a convict can best be employed “in the construction of public roads,” which are “a public necessity” and belong “to all the people of the state.” According to Pratt, the roads produced by convict labor “ [do] not have to be disposed of in competition with products made by free labor.”41 He compared road work to other industries, like manufacturing, where convict labor works in competition with free labor. Pratt declared that “friction has been caused, and still exists, between the private operators of coal mines and the state,” a reference to the mine worker protests of the early 1890s. Pratt asserted that public roads were an alternative that benefited the state, communities, and — through a “healthful occupation” — the convict.42

Pratt praised outdoor work “where the air is pure” and there is “plenty of good drinking water.” He stated that in such conditions “the health of the convict who is employed in road construction and living in the convict camps is better than that of those in any other form of work.”43 Pratt also introduced the idea of an “honor system when the convicts are employed in working public roads.” He believed that very few convicts “are entirely devoid of a sense of honor,” and that the state should “try to bring out and develop this spark of honor” to achieve greater success on the roads. Pratt concluded his presentation with calls to give “a certain per diem” to convicts for their work, and to “commute so many days per month” that convicts worked as a reward for good behavior.44 He reiterated his points in an editorial published in the October 1910 edition of Southern Good Roads, writing that it “is necessary to consider the moral and physical health of the prisoner while he is paying

39 Ireland, “Prison Reform,” 140.