18 minute read

HARDWOOD LOG PROCUREMENT

Inconsistent procurement practices can make log buying and selling less efficient.

APPALACHIAN HARDWOOD PROCUREMENT

Gauging regional log-buying practices

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is the second of a two-part series on hardwood mill practices in the Appalachian region, based on studies by the West Virginia University Appalachian Hardwood Center.

By Curt Hassler, Joe McNeel, Jordan Thompson

Seeking insights into log-buying in the region, researchers with the West Virginia University Appalachian Hardwood Center surveyed hardwood lumber mills across the Appalachian region to determine procurement strategies and identify common grading and scaling measurement protocols.

Part 1 of this series focused on how the hardwood industry, in the absence of a standardized industry-wide log grading system, conducts grading and scaling operations for hardwood logs in the Appalachian region. Part 2 focuses on the procurement strategies being utilized by these hardwood mills.

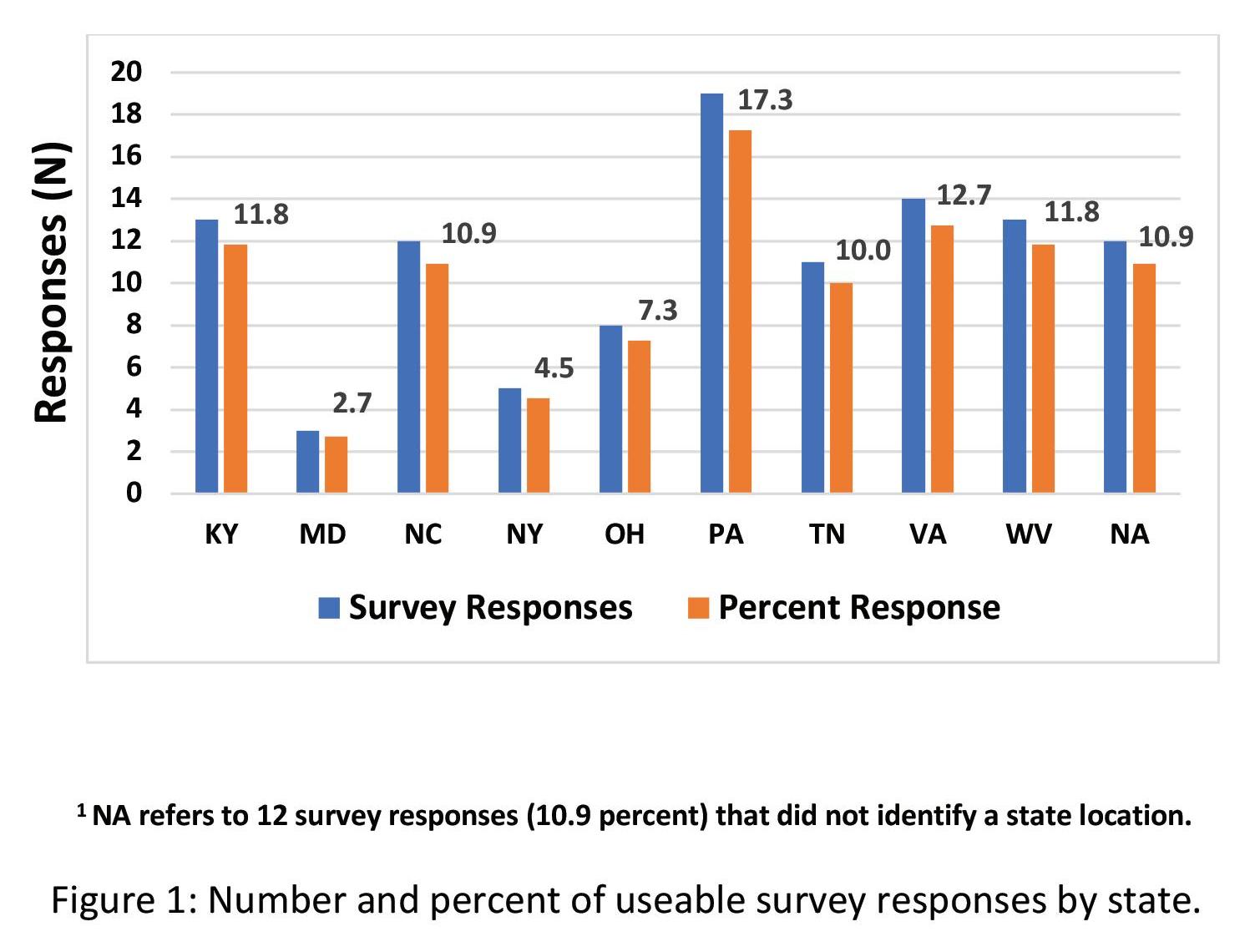

A total of 110 useable survey responses was received, out of an estimated 961 primary wood product producers that were sent surveys. Of the nine states surveyed, Pennsylvania had the greatest number of completed surveys (19) and represented 17% of the total number of responses. A total of 14 responses (13%) were provided by mills in Virginia, followed closely by Kentucky and West Virginia with 13 responses each (12%). Mills from these four states provided almost 60% of the total survey response (Fig. 1).

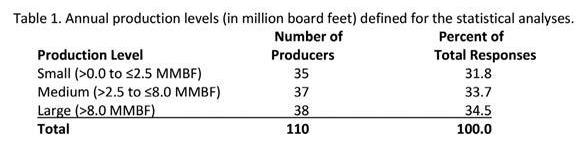

Responding mills provided annual production levels, ranging from 0.04 to 150MMBF with a mean of 9.9MMBF of production. Annual production information was classified into three groups to produce a uniform distribution of responses over three production levels for statistical analysis (Table 1). Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of mills by size and state.

Statistical analysis was used to determine if size of mill (production level) had any significance in grading, scaling or operational decisions. Where a statistically significant difference was determined the results are noted and briefly explained.

For the remainder of this article, the term total number of responses will refer to the number of useable responses to the survey question under discussion. While the 110 mill responses

Figure 1: Number and percent of useable survey responses by state. (NA refers to 12 survey responses (10.9%) that did not identify a state location.)

Table 1. Annual production levels (in million board feet) defined for the statistical analyses.

Figure 2: Distribution of survey responses from sawmills by state and annual production category.

that provided annual production levels were the basis for the analysis, certain questions were not answered by some respondents, therefore analyses were performed on the available responses to those questions.

PROCUREMENT STRATEGIES

Mills were asked if they purchase gatewood, which is defined as logs purchased from an independent logger or wood broker where the seller is responsible for the logging and transportation of the logs to the mill. Of the 108 responding mills, 94 (87%) indicated that buying gatewood is a normal log acquisition process across all production level classes. However, more small mills and fewer than expected large mills responded they did not purchase gatewood and fewer than expected large mills responded they did not purchase gatewood. Additionally, 44% of the responding sawmills reported they get 025% of their annual log supply in gatewood, while 56% reported that between 25% and 100% of their annual log supply came from gatewood.

Mills were asked if they grade logs harvested from their own stumpage tracts. The results suggest that just under 60% of responding mills do grade logs from their stumpage tracts, while 40% indicate that they do not grade logs harvested off their own tracts. Most mills use contract loggers to harvest their stumpage tracts and since these loggers are paid based on volume (and not value), there is less incentive to scale and grade these logs, as illustrated by the 40% that do not grade logs from their stumpage tracts.

In some cases, sawmills prefer to control the merchandising of logs, so they will purchase raw material as treelength stems, where the logs are hauled as treelength pieces (usually to a top diameter that reflects the minimum diameter accepted by the mill for sawing) and then bucked and merchandised at the mill. Of the mills responding, 82% indicated they did not purchase treelength stems. Of the 19 mills that reported purchasing treelength stems, 13 were from three states—Pennsylvania (6), Ohio (3) and Virginia (4). Twelve of the 19 mills purchasing treelength logs purchased less than 50% of their raw material in treelength form and the other seven mills purchased 50% or more, with two mills purchasing 100% of their logs as treelength stems.

When mills were asked if they had difficulty getting longer length logs, 77% of the 107 responding mills reported having no issues getting logs 14-16 ft. in length. The respondents were also asked if they were paying any premium for longer length logs. Of the 78 responding mills, almost 62% indicated that no premiums were being paid for long length logs, while the remaining 38% did pay a premium.

Traditionally, mills have differentiated between butt logs and upper logs when assigning prices. Of the mills sampled, over 50% indicated they do not pay differently for butts and upper logs with the same diameter and the same number of clear faces, even though butt logs generally contain a higher proportion of clear lumber than upper logs. Just over 49% of the responding mills indicated that they pay more for butt logs.

Straight through pricing is used by mills providing a set price per thousand board feet of logs delivered to the mill, based on a minimum scaling diameter and a minimum number of clear faces. For instance, the mill would pay the same price per MBF for logs with a 12 in. scaling diameter and up and having at least two clear faces. The mills were asked to indicate if they offer straight through pricing to loggers and 53% of the 107 responding mills indicated they did not, while almost 47% said they did. The advantage of straight-through pricing is that the log inspection process is expedited at the mill and is much easier for a logger to implement at the logging site. The downside is that pricing the logs is much more difficult because the mill must estimate the proportion of each grade of log (which can vary from tract to tract) and then base pricing on those proportions, which can have potential negative impacts on mill economics.

SPEC SHEET ANALYSIS

Specification sheets are used by mills to show how they assess sawlog value, particularly to potential log suppliers. Mills often make specification sheets available to the public, detailing their log grades and associated pricing. Respondents were asked if their log specification sheets are publicly available, with the most common response being “No” with 63 responses. A statistically significant relationship existed between level of production and whether wood product producers have a publicly available specification sheet, with more of the high production mills likely to have a publicly available written specification sheet.

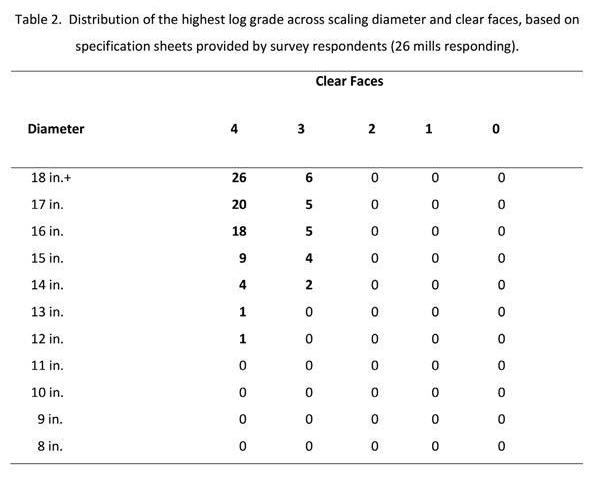

With each survey, participants were asked to provide specification sheets that described their current log grading and pricing matrix, by log grade and species. A total of 26 specification sheets were returned with the survey. These documents generally specified log grade based on clear faces/sides and scaling diameter. An analysis of these specification sheets was made to determine if there was any consistency among and between the responding mills relative to the actual grading processes defined in each specification sheet. The analysis focused on the highest and second highest log grades, excluding veneer grades. The individual mill log grades were used to populate a matrix based on the number of clear faces and scaling diameter.

The matrix was constructed for five clear faces (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4) and 11 scaling diameter classes (eight inches to 18+ inches in 1 in. increments). For example, if the highest log grade specified by a mill included four clear faces and a scaling diameter of 17+ inches, then two cells of the matrix received one frequency count (four clear faces and 17 inches scaling di-

ameter and four clear faces and 18+ inches scaling diameter). In this way, the variability in how the two highest log grades were categorized by responding mills could be evaluated. This process was completed for each specification sheet and the results are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2 illustrates the range of scaling diameters and clear faces for the highest log grade, as defined on the specification sheets. The highest log grade can start at 12 inches diameter with four clear faces or 14 inches diameter with three clear faces. Thus, any log with a small end diameter greater than 12 inches and four clear faces or 14 inches and three clear faces was valued the same per MBF as a log with a diameter of 18 inches and four clear faces, even though the yield of high quality boards is generally greater in larger diameter classes and with Grade variability and overlap between grades contributes to uncertainty of overall log value.increasing number of clear faces. Interestingly, all 26 specification sheets indicated that logs 18+ and four clear faces fit into their highest log grade. Also, high proportions of the 26 sheets showed that 17 in., four clear face (77%) and 16 in., four clear face (69%) logs also qualified for the highest log grade. The same process was applied to the second highest grade as detailed in the individual mill specification sheets, with the results displayed in Table 3. The most common combination of diameters and clear faces is 15 inches and four clear faces. The second highest log grade has a large diameter range and can contain a wide range of clear faces, from two to four. This second highest log grade is quite variable and makes the possibility for fair and consistent pricing impossible due to the variability of the log characteristics that qualify. Where a grade could start at 13 in. diameter and only have two clear faces, the exact same grade at another mill could apply to a log 17 in. diameter and four clear faces.

This analysis of these specification sheets revealed a significant degree of variability in how mills categorize their two highest log grades, with substantial overlap between those log Table 2. Distribution of the highest log grade across scaling diamegrades. There are at least two perspectives to this variability and ter and clear faces, based on specification sheets provided by survey respondents (26 mills responding). overlapping grades. First, from the mill’s perspective of maximizing the production of the highest grade lumber (i.e., Selects & Better) at the lowest possible price, it does not make sense to assign their highest grade log (and their highest price per MBF) to smaller diameter logs with four clear faces (12 inches to 15 inches in Table 2) or logs with three clear faces (14 inches to 18+ inches in Figure 3). Those logs will not produce the volume of high-grade lumber that large, four clear-sided logs will. From the log supplier perspective, there is an obvious advantage to supplying a mill that will accept a 12 in. log with 4 clear faces for the same price as an 18+ in. log with four clear faces. On the other hand, the log supplier is at a disadvantage if the mill is buying 17 in., four clear face logs as a second level sawlog and paying a lower price.

This variability in defining log grade and subsequently log value inevitably produces uncertainty when trying to develop consistent values for hardwood logs and creates confusion for log sellers as they try to maximize the value of their logs. On the other end, this situation creates profitability issues for the mill in its quest to maximize production of higher grade lumber.

Such variability also indicates a lack of thorough knowledge Table 3. Distribution of the second highest log grade across scaling about the lumber grade yields that a mill can expect to produce diameter and clear faces, based on specification sheets provide by from logs of a given size and quality. Most importantly, it illus- survey respondents (26 mills responding).

trates why a standardized system for log grading and scaling is needed by the hardwood industry.

MILLING COSTS

As the price of raw material fluctuates, it has become more important to understand the real cost to operate sawmills. When respondents were asked if they knew the cost to operate their mill per hour, 75% of the 105 responding mills reported they did.

Respondents were then asked if they knew the sawing cost per MBF by species. Of the 103 responding mills, 65% responded they knew the sawing cost per MBF by species. Interestingly, 22 responding mills—more than 20%— stated that they did not know either their hourly costs or costs per MBF by species and presumably are not currently tracking those costs.

One must assume these mills at least know their overall cost per MBF, since that should be readily calculated from total annual mill costs and total annual production. Not knowing cost per hour and cost per MBF by species places a mill at a competitive disadvantage with mills that do know these costs, particularly when establishing log prices.

SUMMARY

The factors reported and analyzed from this survey confirm that the art and science of hardwood log grading and scaling, as well as log procurement strategies, are as variable as there are mills engaged in the manufacture of hardwood lumber. This has led sawmills to purchase raw material on a variety of platforms, leaving the industry and log suppliers in an environment where it is difficult or nearly impossible to make intelligent, economic decisions about where to sell their logs. A cornucopia of grading, scaling and procurement protocols among hardwood sawmills is not serving the overall best interests of the hardwood industry.

The specification sheet analysis suggests that there is little consistency in the prices received for logs of the same diameter and clear faces across, among and between hardwood mills, in part due to a limited understanding of the yield of grade lumber from various sizes and grades of logs by the sawmills buying those logs. Without this information, sawmills can’t define the yield for a specific log and thus can’t ascertain an accurate value or purchase price.

Based on survey responses, more than 65% of surveyed mills would support a standardized hardwood log grading and scaling system. A standardized log grading and scaling system could eliminate much of the uncertainty about hardwood log pricing and procurement practices, as well as accrue benefits and transparency to landowners, loggers, and mills. TP

Joe McNeel is Director of the West Virginia University Appalachian Hardwood Center (WVU AHC); Curt Hassler is a research professor at WVU AHC; and Jordan Thompson is a procurement forester for Millwood Lumber in Gnadenhutten, Ohio.

EACOM PLANS CDK INSTALLATION

EACOM Timber Corp. announced an investment of $8.9 million to equip its Elk Lake, Ontario sawmill with a new, state-of-the art continuous dry kiln (CDK). EACOM didn’t reveal the supplier, though in 2017 EACOM installed a Wellons CDK at its Timmins sawmill. The new CDK is expected to be fully operational by early fall.

“This significant investment in Elk Lake is a testament not only to EACOM’s commitment to technological innovation and being best-inclass, but also to our longterm vision for this region. Built over 50 years ago, this mill has thrived alongside the community thanks to sustainable forestry practices, and now, with this latest addition, we are confident it will be an important partner for many more years to come,” comments EACOM President and CEO Kevin Edgson.

In addition to being more energy efficient, the new system will eliminate the use of both diesel fuel and propane, which are currently being used as part of the energy mix for heating the buildings onsite and two kilns. Going forward, all building heat and the new CDK will be exclusively powered by direct fired natural gas.

The Elk Lake sawmill is an economic driver for the town and surrounding area, supporting more than 140 workers directly, a further 210 jobs in woodlands operations, and hundreds more via vendors, contractors and transporters. Since 2016, EACOM has invested nearly $100 million across its nine facilities. GREENFIRST BUYS RAYONIER MILLS

GreenFirst Forest Products Inc. reports it has entered into an agreement to acquire a port folio of sawmills and a paper mill from Rayonier A.M. Canada G.P. and Rayonier A.M. Canada Industries Inc., each a subsidiary of Rayonier Advanced Materials Inc.

GreenFirst is acquiring the asssets for US$140 million plus the value of the inventory on hand at the time of closing, reflecting an aggregate purchase price of approximately US$214 million.

The properties include six lumber mills—which are located in Chapleau, Cochrane, Hearst and Kapuskasing in Ontario and in Béarn and La Sarre in Québec—as well as a newsprint mill in Kapuskasing. The sawmills have a combined annual production capacity of 755MMBF. The newsprint mill has an annual production capacity of 205,000 MT/year. Collectively, the purchased assets rank as a top 10 producer of lumber in Canada, the company reports. GreenFirst states it will have rights to access approximately 3.29 million m3 of guaranteed fiber supply across Ontario and Québec as part of the deal.

The acquired operations will be led by Rick Doman, one of GreenFirst’s newly appointed directors and an industry veteran with more than 40 years of experience in the lumber industry, who was the founder and previously the president and CEO of Eacom Timber.

GreenFirst believes this acquisition will substantially increase its footprint in the lumber industry following its purchase and investment ➤ 46

43 ➤ in a sawmill in Kenora, Ontario. GreenFirst, previously known as Itasca, purchased the idled Kenora sawmill in October 2020

Doman, incoming CEO of GreenFirst, comments, “As we have done previously with EACOM on the carve-out of saw mill assets of Domtar, our experienced team looks forward to working with the dedicated employees of RYAM to optimize the sawmill assets with a singular focus on maximizing lumber production.”

Closing is anticipated to occur in the second half of 2021.

HOMAG ANNOUNCES IN-HOUSE EXPANSION

The HOMAG Group has launched the largest investment program in its corporate history. Over the next three years, 60-80 million Euro will be invested in the modernization of the main location in Schopfloch, Germany. HOMAG is investing a further 15 million Euro in a new plant in Poland.

A customer center, modern office buildings, a modern dining hall and a logistics center are to be built in Schopfloch. There are also plans to build a new logistics center connected to the site. The goals are a high availability of spare parts as well as lean and efficient logistics processes for supplying the plant and customers.

New buildings are also to be constructed in Poland, where the HOMAG Group already employs 700.

The HOMAG Group is a world leading provider of integrated solutions for production in the woodworking industry and woodworking shops. Its 14 production sites, 20 Group-owned sales and service companies and 60 exclusive sales partners worldwide are supported by a workforce of 7,000 employees. The HOMAG Group has been majorityowned by the Dürr Group since 2014.

MARCH HOUSING HIT HIGH NOTE

U.S. housing starts soared in March 2021, with both single-family and multifamily starts contributing to the boom, according to the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development monthly new residential construction report.

Combined starts in March were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 1.739 million, a whopping 19.4% above February and 37% above March a year ago when the pandemic struck.

Single-family starts in March were at an annual rate of 1.238 million, 15.3% above February and nearly 41% above March 2020. Multi-family starts were 477,000 in March, a 30% jump over February and 27% above March 2020.

Housing starts had dipped in January and February, following four consecutive months of growth to round out 2020.

U.S. housing building permits were 1.766 million in March, 2.7% above February and 30.2% over March 2020. Single-family permits were 1.199 in March, 4.6% above February and 35.6% over March 2020.

LOGGERS WORK FOR LOG A LOAD

Earlier this year, Minnesota loggers and others worked a timber sale north of Duluth that’s expected to net roughly $25,000 for the Log A Load for Kids program and Gillette Children’s Specialty Healthcare through the Children’s Miracle Network.

The harvest was organized by Tom McCabe of McCabe Forest Products and aided by multiple other companies in January and February. “It was a team effort,” McCabe says. “It’s been fun organizing the whole thing. It’s a great cause and we’re glad to help out the kids.”

The sale included 250 cords of aspen, pine, birch, maple, balsam and spruce. Waste Wood Recyclers handled felling and slashing, Watters Excavating provided delimbing, and Rick Olson did the skidding.

Several companies hauled the wood, including Demenge Trucking and Forest Products, Al’s Excavating, Kimball’s Enterprise, Shermer Logging, Rieger Trucking, McCabe Forest Products, Jerry Donek and Chuck Van Dorn. Mills taking the timber included Hedstrom Lumber, Louisiana Pacific, Sappi, UPM Blandin and Lester River Sawmill.

www.timberprocessing.com