DETAILS

Warburg Institute card catalogue, 2021.

CATALOGUE

The Warburg Institute was organised around a unique cataloguing system that created thematic “places” around four overarching subjects (Image, Word, Orientation and Action), each to be given its own floor. These structures dictated the original position of all items in both the Bibliothek (library) and the Photothek (photographic archive). While its idiosyncratic system sometimes made books and images hard to find, it made the whole ensemble—in the words of the Institute’s first director, Fritz Saxl—“a body of living thought.”

It was only once the Institute’s new home in Woburn Square was built, in 1958, that there was room to match the intellectual with the architectural structure. The card catalogue still captures the mind of the Institute’s founder (and indeed, holds his head, sculpted in bronze by his wife Mary): each catalogue drawer relates to a spatial position somewhere in the building.

CLASSIFICATION BY FLOOR

Colour study looking at historic Warburg book cataloguing, translating into wayfinding colours for the renovated library floors, 2024.

HT Proposed Colours

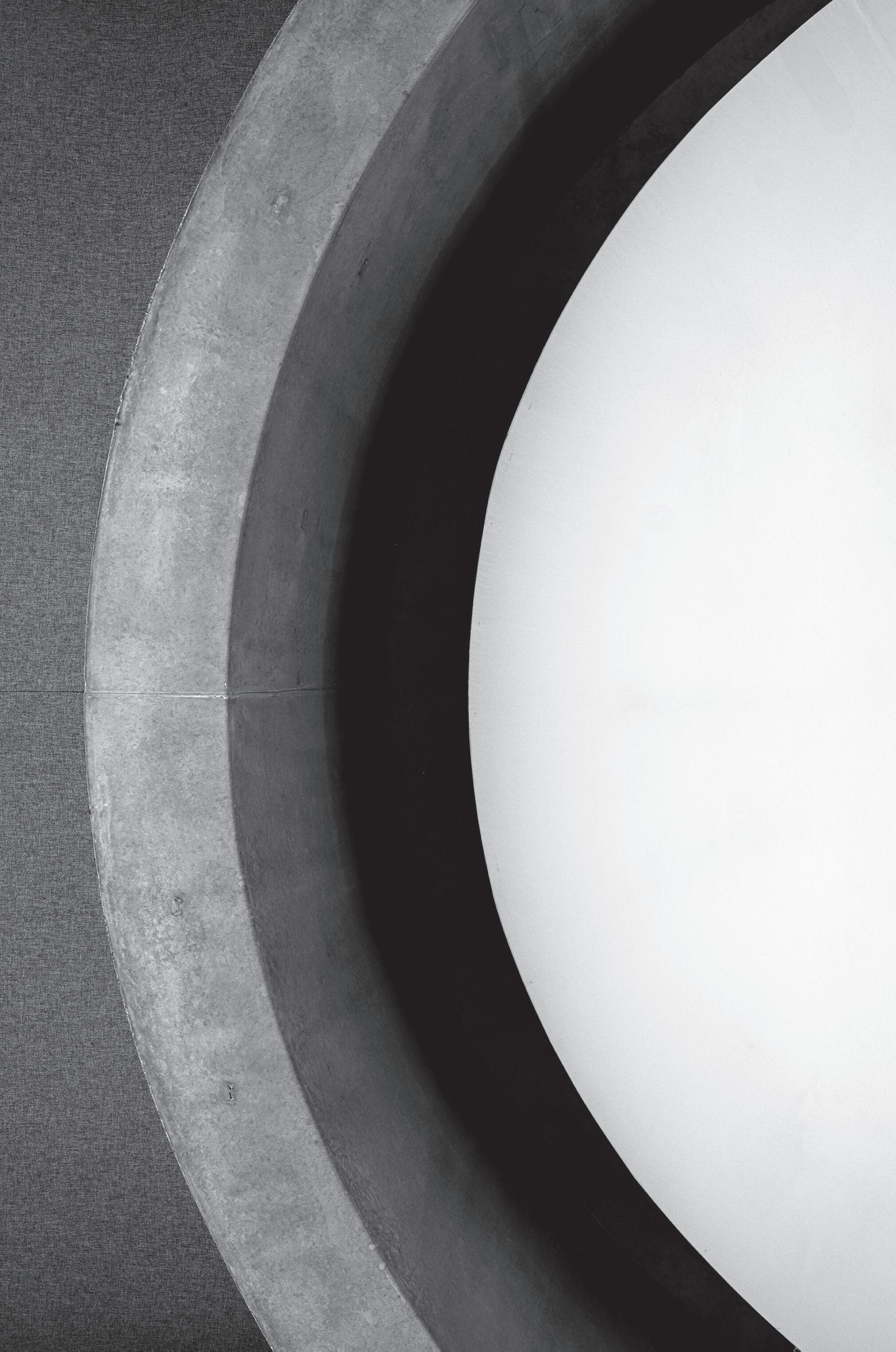

Ceiling and mezzanine to the Reading and Lecture Room, Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, ca. 1927.

CEILING

Working in a research library, you look down when you absorb information. You look up when you process it. Looking down, reading or writing, you encounter obscure texts or simply your laptop screen. Looking up, you encounter what?

Ceilings were important in all the Warburg Institute buildings. In the original institute in Hamburg, the most important space in the project received its own special ceiling treatment: the reading/lecture hall, elliptical in form, was covered by an elaborate ceiling with mouldings running around a central, decorative oculus. The 1957 scheme developed in London was true to the mid-century modernism of its architect, Charles Holden, creating an undisturbed plaster ceiling plane throughout the building, interrupted only by carefully placed light fittings and, in the stack rooms, by drop-cords to control illumination in separate sections of the collection. The Warburg Renaissance project re-emphasises the significance of three rooms on its public-facing ground floor, and, as in Hamburg, these receive special treatment in their ceilings. The new exhibition space and the renovated reading room use a Ligno acoustic timber system, producing a subtly textured surface and a pleasing rhythm. The new Reemtsma Auditorium, constructed within the building’s courtyard, echoes Warburg’s original ellipse in Hamburg, but imprints this onto a coffered concrete structure. These are locations where contemporary craftsmanship has been crucial. The tolerances in the exhibition room ceiling slats are less than 1mm; the lecture room concrete slab and reflecting disc were both formed on site.

Ceiling detail, Reemtsma Auditorium, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Adams, Holden & Pearson Architects, Setting out diagram of lighting points and drop switches in Stack Rooms, Warburg Institute, September. 1956 (detail).

CONDUIT + SLAB

As first constructed, the stack rooms between the first and fourth floors of the Warburg Institute on Woburn Square had drop cords hanging from the smooth plaster ceiling, located precisely at the ends of each shelf stack such that the books in each bay of the collection could be illuminated by a line of strip lights placed exactly over the centre of the aisle between the shelves. To achieve this, the exact layout of the shelving units, a modular system in steel, had to be defined as part of the detailed design process for the concrete floor slabs that covered each storey, and of the electrical layout of the conduit that was cast into them. A detail from the working drawings for the project reveals the trouble taken to achieve this: the drawing is intended for electricians and those who laid out the shuttering for the structure of in-situ concrete planks that covered each floor and the terracotta coffers that spanned between them. Bibliographic organisation reached far into the material make-up the building.

The Warburg Renaissance project restores the placement of shelves established in the 1958 building. In the 1990s, the stacks had been rotated 90 degrees, and carpet and under-floor heating introduced. All these moves were reversed in the 2024 renovation, with a return to linoleum and shorter runs of shelving, perpendicular (rather than parallel) to the perimeter wall, bringing views of windows and the natural light they allow throughout the floorplate. Exposed conduit carries new services across the surfaces of the original structure. The stack room ceilings provide a kind of tube-line map of the shelving beneath them.

Stack room, third floor, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Aby Warburg, “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne,” panel 7 displayed in the reading/lecture room at the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, ca. 1929.

DISPLAY

Aby Warburg had a strong sense of how research related to space. A principle contribution was to insist that the sharing of results was part of the research process itself. A library is not only an arsenal of books, but a public laboratory, a place where displaying your thinking plays an important role in developing it. The original Warburg Institute in Hamburg created one space for both activities: the reading room was at the same time a room for exhibitions and lectures. This pattern was reinscribed in the spaces designed for the Institute after its move to London in 1933 and continued with a series of ambitious photographic exhibitions after 1940 (displayed both at the Institute’s home in the Imperial Institute and sent as touring displays around the country). This function was lost entirely from the 1958 project at Woburn Square. The Warburg Renaissance project reinstates this combination of discovery, display and debate. On the ground floor, a dedicated exhibition area now serves to link the new lecture room, projecting into the building’s courtyard, to the newly renovated original reading room. The exhibition space is kept flexible. Suspended screens, modelled on Warburg’s original displays, allow for repeated reconfiguration.

Kythera Gallery, ground floor display area, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Matthew Hall & Co. Ltd, Warburg Institute Basement Drainage Layout, 1956 (detail).

DRAIN

All architectural projects, however esoteric, are conditioned by water, running in at the top as downpipes handle rain, and running out at the bottom as drains deal with waste. For the Warburg Institute on Woburn Square, Charles Holden’s office designed elaborate hoppers to deal with the oceans of rainwater that any London building can expect during its life; cast in lead they weigh around 40kg each. The Warburg Renaissance project was partly a detective story to understand the routes a multitude of drains took as they emerged from beneath the building and to ensure that they arrived at their appropriate destinations.

Adams Holden & Pearson Architects. Lead rainwater hopper, Warburg Institute, 1957.

Gerhard Langmaack, Setting out drawing for the elliptical reading room, Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, 1926.

DRAWING

Architectural projects leave records of all kinds of drawings. Sketches and initial proposals occupy shelves in architectural offices. Sometimes they enter museum collections as the work of architectural offices is archived in projects of disciplinary history. The Warburg Institute Archive shows another, usually lost, layer in this archaeology—dyelines of many drawings issued for sign-off during the 1950s project show mark-ups and discussions as clients and architects negotiated over details.

George Allan, Early design sketch showing ideas for a courtyard extension and ground floor, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2019.

David Bennett formwork sketch for downstand beams and ellipse, Warburg Lecture Theatre, 2020.

Construction photo of the Reading and Lecture Room, Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, ca. 1925.

ELLIPSE

Warburg’s institute in Hamburg used an ellipse as the basis for the plan of its reading and lecture room. The geometry had a significance that was both intellectual and personal. Warburg’s view of the world was bipolar: life’s trajectory was a path governed by the simultaneous effect of dark and light foci; the rational and the irrational; superstition and raciocination; discipline and errantry. In his studies of the history of astrology and astronomy, the ellipse brooded as the figure that would finally account for the vagaries of the apparent motion of the planets across the sky, substituting scientific visions of the universe for equally powerful religious or mythological ones. In the Warburg Renaissance project the ellipse is reimprinted into the geometry of the new lecture room, articulated in the ceiling structure in an echo of the reading and lecture room in Hamburg. Here the figure is rendered in polished concrete around a central false oculus.

Reemtsma Auditorium, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024

Reemtsma Auditorium, Aerial view of the elliptical concrete beam setting-out, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Sir Ernst Gombrich in front of the Warburg Institute’s main door. Photo: Pino Guidolotti, 1977.

ENTRANCE

The entrance to the Warburg Institute sits slightly awkwardly at one end of the least-public façade of the building, placed on Woburn Square according to a plan for a much larger, and never-to-be built structure of which the 1958 project formed a fragment. The original entrance sequence was slightly forbidding. Blank double doors, their style reflecting Holden’s other buildings for the University of London, were surmounted by the Institute’s emblem set in stone. Entering the main interior crabwise, visitors navigated a glazed screen to approach the window of an enclosed reception kiosk, where readers’ cards were shown, or admission applied for. The Warburg Renaissance Project subtly amends this sequence, redisposing its elements and opening up the interior space, while leaving the external arrangement intact. A new reception desk, echoing that of the original Holden scheme, provides a welcoming and inspiring point of arrival; visitors standing at it can see clean across the building, into the central courtyard/ light well, through the new lecture room, on across the reading room and out onto Torrington Place.

GHOSTS

Warburg famously called the study of art history “ghost stories for grown-ups,” and the architectural process of the Warburg Renaissance Project was one full of hauntings. Working on the new/old building has been an education in navigating the constant and surprising presence of the past, and indeed of past projections of the future. From its beginning the Warburg Institute was developed in relation to other structures, visible and invisible, to which its buildings referred. In Hamburg the institute occupied a gap-site beside Aby Warburg’s own home and made reference to the invisible life that went on within that apartment, hidden by a party wall, but accessible using a common lift. When an agreement was reached to construct a new building for the institute as part of London University after 1945, the Warburg was to be housed in a shared building with the Courtauld Institute of Art. The building in Bloomsbury is the built half of a much larger anticipated project to house both institutes; another imaginary structure looms alongside it. There is at least one human ghost present in the building, as well. The institute’s original librarian, Hans Meier, moved with the books to London. During intensive bombing on 17 April 1941, Meier’s home was hit and he was killed. His colleagues kept his ashes and—knowing how committed he was to the institute—mixed them into the foundations of the new building in Woburn Square some sixteen years later.

Construction photo, Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg,, Hamburg, ca. 1925.

Tereza Červeňová, from Nymph (London: Everyday Press, 2024), representing a photographic residency during the Warburg Renaissance Project.

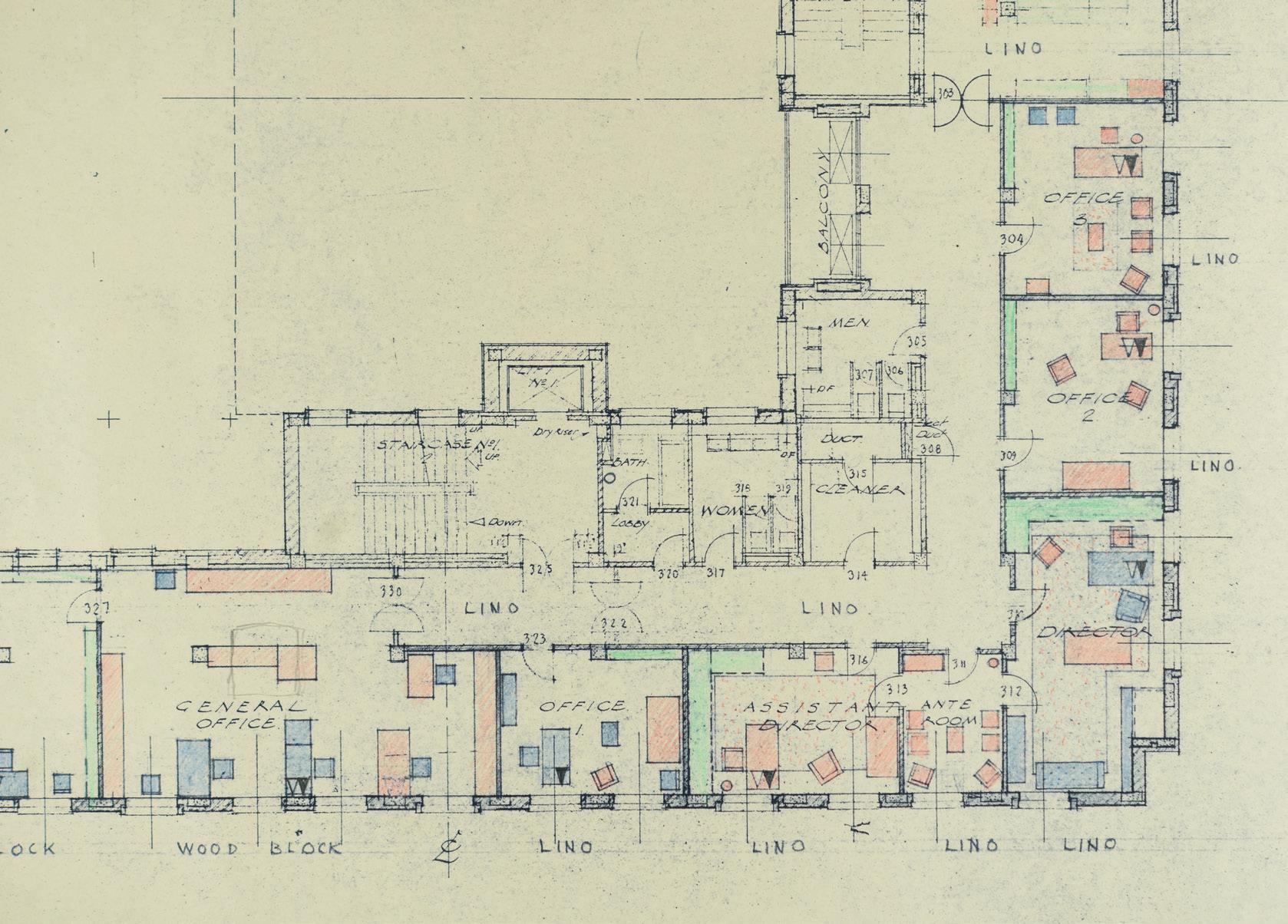

Adams Holden & Pearson Architects/Gertrud Bing. Marked up plan showing furniture location, room names and the “knuckle”, third floor, Warburg Institute, Woburn Square, ca. 1957.

KNUCKLE

Constructed as a fragment of a much larger project, the plan of the Warburg Institute stretches around its site like a right hand making the letter “C.” The building is entered from a space between thumb and first finger on its east façade; its finger tips enclose the reading room on the west side. A crucial point in this plan is the “knuckle” at the north-east corner. Here, the original project located the main riser for the building. Here now, services criss-cross, and the technologies required to run a library in 2024 are carried through a structure designed for the much simpler requirements of 1958. Invisible to visitors to the building, except as the location of a sharp left-hand swing into the exhibition area on the ground floor, and as the location of the toilets on the floors above, this knuckle was central to the successful execution of the new project. Understanding it, and the spatial planning of its contents, were key concerns.

The invisible “knuckle” as viewed from the small atrium, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

JOINERY

The 1958 Warburg Institute was given a sense of opulence by the quality of its joinery items, set against the other more utilitarian materials that made up the palette used by Charles Holden’s office for their London University buildings: linoleum floors, painted plaster finishes to walls and ceilings, and clinical white tiles in wet areas. The Warburg Renaissance project matches this high-quality 1950s joinery work, using sustainably sourced sapele timber to match the detailing of screens and doors in the original building, and to form acoustic panelling on the walls of the new Reemtsma Auditorium in its courtyard.

Reading Room, Warburg Institute, 1958.

Reading Room, Warburg Institute, 2024.

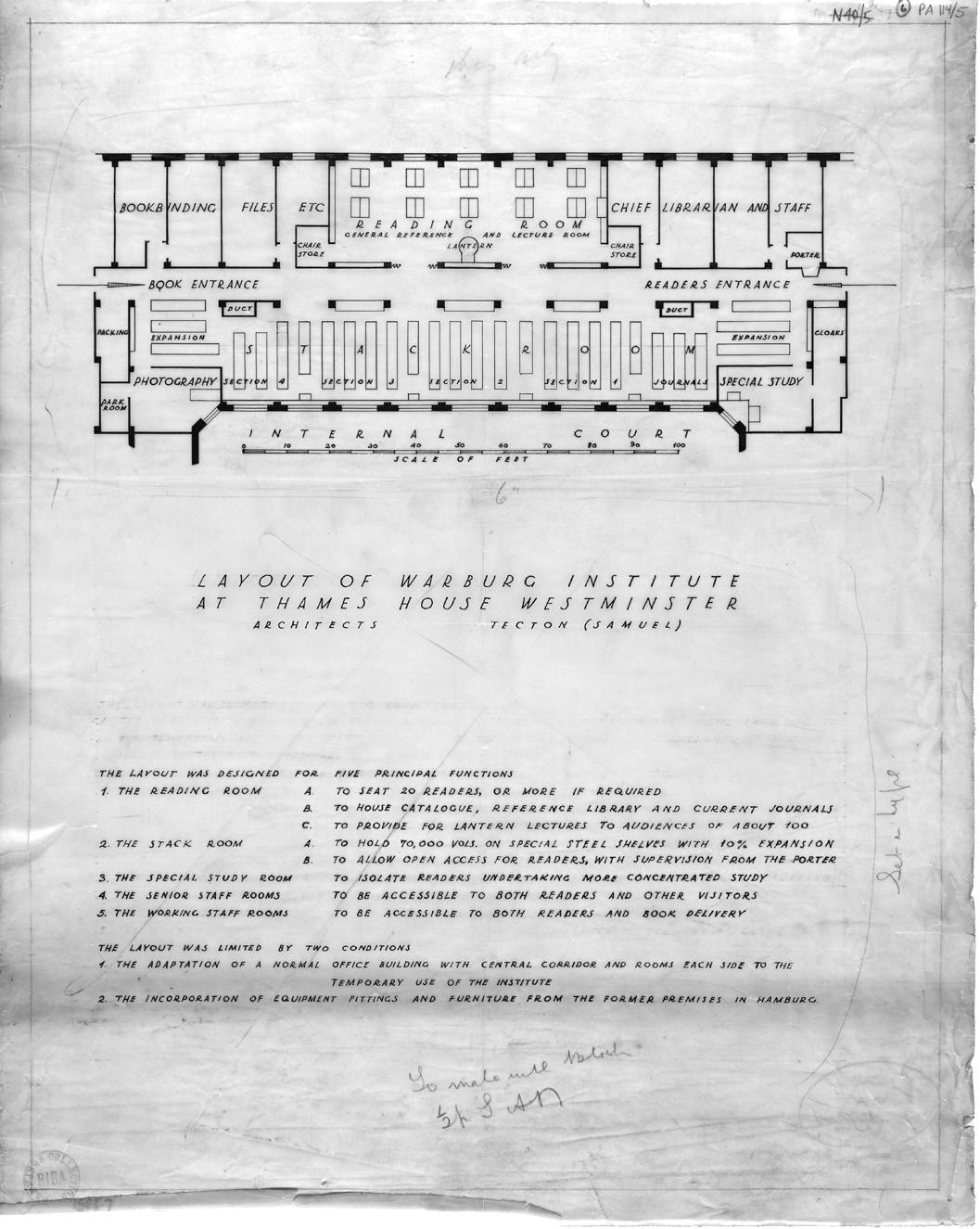

Tecton. Presentation plan, Warburg Institute, Thames House, 1934.

LIGHT WELL

A major intervention in the Warburg Renaissance project involves the construction of the new Reemtsma Auditorium (above) and Wohl Reading Room (below) in the courtyard of the 1958 building. The courtyard has a curious history. Its white tiles reveal the ghost of the unbuilt project of which the Warburg Institute forms a part—the courtyard was to have been entirely internal; the white tiles were to reflect light. But they also echo a detail in the institute’s first London home, the ground floor of the monumental Thames House building on the Millbank embankment. There, as at Woburn Square, readers using the stackrooms gazed out into a white tiled light well. In the 1958 building, the glazed tiles of the courtyard, thick pieces of ceramic 6×9×1", reveal the care and craftsmanship that characterise the original design. They coordinate exactly with the window openings, whose surrounds meet the grout lines between in the tiles in a perfect match. The structure of the Reemtsma Auditorium, placed carefully within this space, is surrounded by minimal glazed roof strips, allowing light to travel down to the Wohl Reading Room at the base. The internal windows of the lecture room allow clear views across the building. The white reflective tiles now fulfil their intended function.

Light well, view to first floor roof-lights, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

MATERIALS

Material selection for the 1958 and 2024 schemes for the Warburg Institute involved very different processes. Britain during the 1950s was affected by supply issues and economic austerity beginning in the years after World War II. Timber was still a product of Empire; the main joinery elements in the 1958 building are mahogany or sapele, sourced from somewhere among the British Protectorates. Almost all component manufacture was national; there was a limit on what could be obtained and the original building projects some sense of this sparseness. In 2024, materials can come from anywhere: the acoustic timber ceiling system on the ground floor is German, the coloured cork panels used for the floor in the Wohl Reading Room are Italian and the grey bricks lining the courtyard structure are Danish. As well as budget, limits on material choice must now be introduced by an awareness of the embodied energy costs associated with transport and production, an ethical response that Haworth Tomkins has been instrumental in developing across the building industry. In some cases, materials that were available in the 1950s are still logical and ethical to use: the Warburg Renaissance project uses linoleum for the stackroom floors as did the 1958 building. In other cases more care is needed. The choice of terrazzo for the reception desk was only made after a careful assessment of its CO2 footprint.

First floor stacks, Warburg Institute, Woburn Square, 1958.

Reception desk, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Wolf Netter & Jacobi “Lipman” shelving, Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, 1927.

METERAGE

Libraries that collect physical books are an infinitely extending worm of shelving. A crucial dimension and limit is the total length that all those volumes require. The Warburg Institute, like any other library, was acutely aware of this never-ending problem, in which success in collecting always leads to problems in space. So aware, in fact, that when the institute moved to London in 1933, its director, Fritz Saxl, required English manufacturers to produce metal stack shelving in one-metre instead of 3-foot modules, so that the spatial expansion could be calculated exactly. Henri Frankfort, who succeeded Saxl, provided for the architects of the 1958 building a plan diagram that specified both the module and the density of the shelving, which in turn became a basic controlling factor in the scheme developed for Woburn Square. The Warburg Renaissance Project expands the original shelving meterage by 40%, re-establishing the layout of the stacks that characterised the 1958 building, although increasing its density slightly (the aisles between the stacks are 850mm rather than 1050mm wide). Rollerracking was also introduced for the new Archive and Special Collections store. At a time when many libraries are reducing space for physical collections, the Warburg Renaissance project creates room for several decades of future growth.

View through library stacks, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Aby Warburg and Fritz Saxl, Diorama model of the tomb of Seti I. Picture exhibition on Astronomy and Astrology, Hamburg Planetarium, 1930.

Charles Holden’s original model for the University of London Bloomsbury masterplan, 1950.

MODELS

Haworth Tompkins use large scale physical models as a central part of their design process, a method developed from their work on theatre buildings and the use of 1:25 set models to plan theatre productions. The potency of architectural models was also of significance to Aby Warburg and his early collaborators. For an exhibition on the history of astronomy and astrology, constructed in the Hamburg Planetarium that Warburg was instrumental in commissioning during the 1920s, peep-show dioramas were created showing interiors that themselves modelled the system of the cosmos. Like Haworth Tompkins’ “Great Model” of the Warburg Renaissance project, or indeed Adams Holden & Pearson's model of the Bloomsbury masterplan for the University of London, these allow a public to project themselves into another time and place, using architectural means to do so.

Ellie Sampson, 1:25 Great Model for the Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Ellie Sampson, study model showing courtyard extension massing, 2019.

inscribed over the inner entrance doors, Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, 1927.

Mnemosyne

MNEMOSYNE

Mnemosyne. Memory. Past in present. The research themes of the Warburg Institute and the institute’s continuing involvement with architectural commissioning have always been intimately linked. In the original institute building in Hamburg, “Mnemosyne” was inscribed over the entrance door in a script designed by the city architect of Hamburg, Fritz Schumacher. As the 1958 project for the institute’s London home neared completion, the director, Gertrud Bing, insisted that the name of that presiding deity (Mnemosyne was the goddess of remembrance in ancient Greece) be reinscribed on the screen that separated entrance vestibule from main reception area. Visitors entered one building about memory via the memory of another. In the Warburg Renaissance project, Mnemosyne moves further into the plan of the Warburg Institute. The inscription is now placed immediately next to the frieze of the Nine Muses, over the doorway that takes visitors from the lobby into the exhibition space. This placement creates a kind of family reunion: Mnemosyne was the mother (with Zeus) of the classical muses of all arts and sciences.

Mnemosyne and her daughters, the Nine Muses, Warburg Renaissance Project, London, 2024.

Entrance to the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek

Warburg, Hamburg, 1927.

NEW BRICK

The Warburg Institute has always commissioned brick buildings. The Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in Hamburg was designed in a tradition of expressionist brickwork used in the city during the early years of the twentieth century, its façade combining references to the industrial architecture of warehouses with features familiar from suburban Jugend villas. (This system of expression also inspired Charles Holden, later architect of the London Warburg Institute, who travelled to Hamburg to study its brick expressionism in 1930). In their brief to Holden, the University of London decreed that the London institute was to be “red brick with stone dressings.” In both cases the brick used was local, London and Hamburg sharing a winding river-valley location surrounded by the clay beds that the geology of such locations produce. The Warburg Renaissance Project continues this tradition of brick construction in its only area of new exterior façade. The south elevation of the Reemtsma Auditorium uses a Petersen brick, perforated in places as a brise-soleil to its windows. In 2024 the brick comes from further afield, from Broager in Denmark. But the bond repeats that on the main façades of the 1958 building, and its dove-grey tone coordinates with the hues of the surrounding light well tiles and the original concrete surrounds to the courtyard windows.

Perforated brickwork screen to window in the Reemstma Auditorium, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Haworth Tompkins, Working drawing setting out the brick coursing to the new courtyard façade, Warburg Renaissance Project. The main “English Garden Wall Bond” is animated with areas of “hit and miss” brickwork and recessed perpends.

RADIATOR

One of the most complex issues in architectural re-use is how to meet current requirements relating to climatic control and energy consumption in buildings developed before those requirements were in place. Often there is a minimum or a maximum strategy to be adopted: significant alteration in terms of mechanical systems, additional insulation or upgrades to elements such as windows, versus minimal alteration. The Warburg Renaissance project takes the minimal approach. The building remains naturally ventilated except in new-build areas and locations such as the exhibition area, where some mechanical back-up is essential to meet museum conservation requirements. Secondary glazing to the original single-glazed windows is added internally. One area that required careful thought was the heating strategy. The 1958 project was heated and cooled through water pipes cast into the underside of the floor slabs, producing radiant panels in the ceilings intended to control the temperature on the floors below them. In replacing this system (which no longer functioned) with more conventional radiator units beneath the windows, the team had to negotiate the fact that the windowsills across the various floors of the building change level. A small essay in component selection ensued, finding elements that fitted the varying heights, were aesthetically acceptable, and which provided sufficient power.

Construction photo, Warburg Institute, ca. 1955, showing build-up of floor slab structure accommodating heating pipes and radiant panels.

Views along the external walls reveal the extensive run of new radiators, broken by French windows and secluded study tables, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Collection of Lord Lee of Fareham displayed in the Courtauld Galleries above the Warburg Institute, ca. 1960.

SLADE

The post-war building for the Warburg Institute was to have been much larger and was to have also housed a non-identical twin, the Courtauld Institute of Art (founded one year before the Warburg arrived in London and similarly associated with London University). The histories of these two organisations are linked. Samuel Courtauld, who made the endowment that established the Courtauld, supported the Warburg Institute as well; the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, now in its 86th year, remains one of the most respected in its field. When plans for a combined institutional building were abandoned in the late 1950s, one aspect of the twinning was kept. From Gordon Square, one can see that the top storey of the Warburg Institute provides a set of top-lit spaces directly under a collection of roof glazing. These were designed to house the art collection bequeathed to the University by Lord Lee of Fareham, also a key supporter of the initiative to create a common centre for art-historical research in London. The terms of his bequest, which provided much of the funding for the new building, were that a combined home for the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes should house his paintings and Warburg’s library. The library occupied the lower five storeys. Lee’s collection, donated to the Courtauld Institute, occupied the top level—accessed through a separate ground level entrance with a dedicated goods lift. By 1990, these spaces had been taken over by the Slade School of Art and since then have provided generations of art students with a hidden eyrie in the heart of the city. The Warburg Renaissance project, in collaboration with the Slade School, included the renovation of these neglected spaces, reinstating daylighting to the studioss and providing a much-needed boost to this space for artistic practice.

Renovated studios, Slade School of Art within the Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

Spiral service stair, Kulturwissenschaftliche

Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, 1927.

STAIR

As a vertically organised building, the Warburg Institute is mortgaged to the quality of its staircases, a condition that also characterised the four-level library in its first articulation. Where the Institute’s original home in Hamburg contained a steel spiral stair linking stack rooms and reading room, in the Woburn Square building the staircases provided casual meeting-places for staff and housed art works central to the institute’s identity. Because they are constructed in very high-quality materials, these spaces have required very little restoration in the Warburg Renaissance Project. Outside the building more alterations were needed. Replacing a defunct fire stair on the west elevation of the internal courtyard, an opportunity arose for light-footed structural engineering. The reconstructed stair cantilevers out before the courtyard lecture room, its weight taken on a single steel column, leaving the landings free from visual obstructions.

Escape stair, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

WINDOW

At its completion in 1958, the Warburg Institute project received indifferent reviews from the architectural critics of the time. Writing in the Manchester Guardian , Nicholas Pevsner compared the building to a telephone exchange. These reservations reflect the low-key, aesthetically conservative and apparently standardised quality of its three free façades. There is something of the Giles Gilbert-Scott telephone box about the building’s window proportions; repetition dominates the façades, while a pared-down classical scheme of brickwork relief and white concrete string-course banding reduces its effect.

In detail, however, a bespoke quality shines through this utilitarian composition, a quality that appears more valuable in the 2020s than it did in the 1950s. A final area of subtle enjoyment for the project team came as they examined the familiar profile of the W20 window-sections used throughout the 1950s building. While this system, in its standardised form, uses metal beading to retain windowpanes, the Warburg Institute uses a subtle variation that slightly softens the industrial lines of the system. Here, metal angles are replaced with hardwood glazing beads with minimally radiused corners on their ¾" section. The effect is almost invisible but introduces a mnemonical depth into the experience. The windows distil into their design a family of previous glazed openings through which Warburg Institute readers have observed the world, from the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in Hamburg, constructed during the 1920s, through the heavy neoclassical façades of Thames House on Millbank in London, where the Institute was based during the 1930s, to the eclectic and monumental windows of the Imperial Institute in Kensington, in which the plans for the building on Woburn Square came to fruition during the 1940s.

In the Warburg Renaissance project these softened W20 windows are retained, cleaned and repainted. In this case, renaissance comes through the simple touch of routine building maintenance. Elsewhere, in new elements such as the lecture room and associated glazed roof to its surrounding light well, high-quality contemporary window systems have been used, to maximise sightlines and to sympathise with the aesthetic that binds the new and the original parts of the building together. For the first time, window openings on opposite sides of the building provide interior views that stretch from one façade to the other, connecting staff, students and readers with the trees and traffic outside.

Warburg Institute, Woburn Square. Detail of window system from the 1958 project.

Reemtsma Auditorium window detail, Warburg Renaissance Project, 2024.

folloWI ng spreaD: “A relief of the Nine Muses in Coade stone after a classical sarcophagus dismantled from the façade of No. 1, Gordon Square will be preserved and let into the entrance wall.”

Gertrud Bing, Warburg Institute Annual Report for 1955–1956.

T he bu I l DI ng as W e foun D IT was extremely original; much of the 1950s fabric was intact and apart from a small infill extension at the rear, the building had been untouched since the Warburg took occupation in 1958.

Charles Holden, the architect of the building, used a pared back modern classical style that reflects some of the neo-Georgian work of Hubert Lidbetter at Friends House nearby, and elements of Grey Wornum’s more extreme stripped classical style at the RIBA headquarters, but also echoes an interest at the time in England in north European architects such as Asplund.

As an institution, the Warburg has retained the feeling of the bespoke, inherited from the original foundations in Hamburg, with a genuine and personal attention to detail. In some areas the Institute has stood still and the fabric, which has changed very little, contains all the authenticity and mild idiosyncrasies of a historic institution.

In others, advances in new technologies have made specific demands on the architecture, which have not always been successfully resolved. The top floor of the building originally contained the Courtauld Institute of Art, now the Slade School of Fine Art, under a series of sloping rooflights, and this also formed part of our project scope.

Interestingly, the building was quite poorly received upon completion and was seen to be of a low architectural standard by the architectural press. Time has been a kinder critic and today the building is seen as an intact example of its period, and is considered by those that use it to be easy and comfortable to work in.

The building was generally in good repair and worked well as a library and study centre. It was clear to me that its strength lay in the quality of its originality; it was period correct, and what was needed was an inventive ‘refresh’ rather than radical change.

The opportunities appeared to lie in bringing the programme of the Warburg as a teaching institution into focus and to update the building to support this in ways that respected its inherent qualities and strengths. It lacked

some key facilities such as an adequate lecture theatre and space for exhibitions, gatherings and display, and it needed to adapt to accommodate different technologies, teaching and research methods that had developed since it came into being. Renaissance (or rebirth) became the title for the project and perfectly captured the essence of the challenge.

Whilst I knew that we needed to somehow preserve the building’s key characteristics, we also needed to celebrate the Warburg as a cultural institution and an extra layer of cultural amplification came through conversations with Warburg Director Bill Sherman. He shared with us the history of the Institute, the relevance of the ellipse in the original building in Hamburg and the German concept of Denkraum—space for ideas and exchange.

These themes informed key concepts in our physical designs, with the intention of using the new interventions to stitch together the existing spaces and improve circulation flow in the public areas of the building. Our main addition was a new lecture space with an elliptical roof form and a Special Collections study area below it in the central courtyard, and a general de-silting of the lower floors. The perimeter, previously a closed office corridor, was opened with a new gallery space creating a more generous route to the main reading room, making the activities within the building more visible and welcoming from the street.

We have tried to create a series of spaces that serve the Warburg’s traditional vocation of facilitating knowledge, encounter and exchange, and to express this in the architecture, with a material language that resonates with the original qualities of Holden’s design. We collected a selection of image fragments including an original copper ticket holder by Holden and an abstract model of one of his seminal tube station designs for London Underground, that acted as reference points for us to create proposals that work with the building’s mid-century classical modernism.

Graham Haworth Co-founder, Haworth Tompkins.

The Warburg Renaissance

Rebuilding the Institute

eDIT ors

Tim Anstey, Bill Sherman, Dan Tassell

D e T a I l D es C r I p TI on T e XT s

Tim Anstey

C oor DI na TI on Dawn Hepburn

p ubl I she D by

Haworth Tompkins Architects

110 Golden Lane, London eC1y 0T l

The Warburg Institute

Woburn Square, London WC1h 0 ab

September 2024

Des I gn

Oliver Long and Scout Curlewis

p r I n TI ng

Pureprint

I sbn

123-4-5678-9012-3

Image C re DIT s

Archive Nicholas Chinardet: p. 9 (right)

Archive Uwe Fleckner: p. 52 (top)

Christopher Lu: p. 21

Courtauld Institute: p. 60

Fred Haworth: pp. 6, 7, 11, 12, 20, 21, 24, 27, 29, 37 (top), 39, 43, 45, 47, 49, 51, 55, 57, 59, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67

Hamburgisches Architekturarchiv: p. 34

Haworth Tompkins: pp. 33, 37 (bottom), 53

Matt Crossick: p. 30

Pino Guidolotti: p. 38

RIBA Drawings Collection: pp. 10, 44

Tereza Červeňová: p. 41

University of London: pp. 32, 52 (bottom)

Warburg Institute Archive: pp. 9 (left), 10 (right), 24, 26, 28, 30, 36, 40, 42, 44, 48, 50, 54, 56, 62

h I s T or IC al resear C h

Oslo School of Architecture and Design

“Warburg Models” Project

Cl I en T

The University of London and the Warburg Institute

a r C h IT e CT

Haworth Tompkins

sT ru CT ural e ng I neer

Price & Myers

s erv IC es e ng I neer

Skelly & Couch

p roje CT m anager & Cos T Consul T an T

Artelia

p roje CT managemen T

University of London Estates Division

m a I n C on T ra CT or

Quinn Heritage

p roje CT T eam

Warburg Institute: Bill Sherman, Madisson Brown, Peter Lin, Giles Mandelbrote, Clare Lappin

University of London: Andrew Beach, David Byron, Emel Kus, Kevin Roberts, Lee Winters, Melissa Styron

Haworth Tompkins: Dan Tassell, Elizabeth Flower, Ellie Sampson, Graham Haworth, Harriet Mulcahy, Hugo Braddick, Jonathan Rees, Laura Haylock, Nigel Hetherington, Toby Johnson

Price & Myers:

Gemma Carey, James Stevenson, Paul Batty, Yousef Azizi

Skelly & Couch: Julie Arneson, Julian Cottrill, Tristan Couch

Artelia: Conor Coley, Fion Tsen, James Illsley, Simon Cash

Quinn Heritage: Alex Butt, Andrew Williams, Gary Shead, Ian Lock, Ionut Alexa, Paul Marston, Pip White, Rob Davies, Simon Eddison