hayandforage.com

August/September 2023

The sexy one pg 12

Converting hayfields to pasture pg 14

A 2023 equipment rundown pg 26

Prioritize fall pasture care pg 27

hayandforage.com

August/September 2023

The sexy one pg 12

Converting hayfields to pasture pg 14

A 2023 equipment rundown pg 26

Prioritize fall pasture care pg 27

KUHN offers the most efficient and versatile range of fixed and variable chamber round balers available on the market.

These round balers ensure consistent, perfectly shaped round bales and produce exceptionally high bale densities even in the most demanding conditions.

No matter if you’re baling dry hay, corn stalks, high-density baleage or anything in between, KUHN round balers are ready to work for you.

Visit our website to locate a Dealer near you!

Apollo-Vale Enterprizes provides custom forage harvesting services to farmers in the Driftless Region of Wisconsin. Its owners, Ray and Holly Liska, also farm their own land, raise poultry, and are raising a young family.

MANAGING EDITOR Michael C. Rankin

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Amber M. Friedrichsen

ART DIRECTOR Todd Garrett

EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Jennifer L. Yurs

ONLINE MANAGER Patti J. Hurtgen

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING John R. Mansavage

ADVERTISING SALES

Kim E. Zilverberg kzilverberg@hayandforage.com

Jenna Zilverberg jzilverberg@hayandforage.com

ADVERTISING COORDINATOR

Patti J. Kressin pkressin@hayandforage.com

W.D. HOARD & SONS

PRESIDENT Brian V. Knox

EDITORIAL OFFICE

28 Milwaukee Ave. West, Fort Atkinson, WI, 53538

WEBSITE www.hayandforage.com

EMAIL info@hayandforage.com

PHONE 920-563-5551

Virtual fencing is being tested in the West to identify both its benefits and challenges.

20 NEW TECH TARGETS HIGHYIELD ALFALFA

26 A 2023 EQUIPMENT RUNDOWN

27

PRIORITIZE FALL PASTURE CARE

28

BE INCLUDED IN PREPARTUM DIETS 19 FORAGE AND RATION SAMPLING REVISITED

HESSTON BY MASSEY FERGUSON LAUNCHES NEW ROUND BALER LINE

This scene was a much more common one 50 years ago. These two central Michigan women were hard at work in late May putting up first-crop hay. There is no doubt many of our subscribers can recall their own experiences of “riding the flat rack.” Few other activities offer a greater opportunity to build muscles, a sense of balance, hay-stacking skills, and character.

Photo by Mike Rankin

IT WAS 1974 when the Burger King franchise broke out its “Have it your way” campaign. The slogan has been ditched, brought back, and modernized many times over the years and appeals to those customers who want to build their own Whopper. It doesn’t appeal to the person waiting in the drive-thru while the customer in front of them attempts to describe their preferred deviations from the standard-issue Whopper.

So, what does a Burger King slogan have to do with forage crops other than they sell foragederived hamburgers?

It recently occurred to me that no other farm enterprise embodies the “Have it your way” slogan more than that of forages. Legume and grass forages can be grazed, greenchopped, chopped for haylage, baled wet and wrapped, baled dry in large or small packages, or allowed to just grow for wildlife habitat. Forages can be stored in barns, silos, bunkers, piles, bags, plastic wrap, under tarps, or, in the case of large round bales, simply left outside. Within all of these options, there are even more opportunities to deviate with equipment, varieties, additives, grazing systems, cutting schedules, and handling. The plethora of production options that forage crops provide is unique to agriculture.

The “Have it your way” mantra hit me as I was contemplating what to put on the cover of this issue. Should it be the often-used harvesting photo of cutting, chopping, or baling? Perhaps corn silage would make a nice theme for the upcoming fall season. I’ve got some attention-getting grazing photos, maybe that’s the way to go.

Finally, an earlier summer trip to Michigan with editorial colleagues came to mind. As a passenger in the shotgun position, I recalled driving down yet another two-lane road to a planned farm visit. Off to the left, I spotted a couple of flat racks parked near the roadside and a cabless tractor in the distance with an experienced small square baler and flat rack in tow. “Pull in here!” I shouted as we rapidly approached the field entry.

Our driver made a quick left turn into the field at slightly less than road speed, putting seat belts and the durability of loosely set items to the test. Once everyone regained consciousness, I grabbed my camera and began trekking across

the field to the nearest windrow. There, I waited for the baler’s return run.

As the slow-moving baler and crew approached, I had a business card and camera in hand. In these situations, one never really knows if you’ll be greeted with a friendly smile or the muzzle end of a shotgun. This time, it was somewhere in the middle.

The farm-worn gentleman on the tractor didn’t look particularly pleased to stop the tractor. I held out my business card and asked if it would be okay if I took some photos. “Yeah, I guess so,” he said somewhat grudgingly. “But leave me out of it,” he added while pointing to the two women on the wagon who were stacking bales.

“Thanks!” I replied, as he put the tractor back in gear and opened up the throttle.

I didn’t talk to any of those subjects after that. I can’t tell you the women’s names because I don’t know them, but I’m sure someone who sees the cover might. At this point, I’d just like to publicly say thanks to them for stopping and giving me the opportunity to shoot a few photos without getting shot myself.

Although many who are reading this probably have memories of riding on a flat rack, you’ve likely moved on to one of the many forms of forage harvesting techniques that don’t allow for intimate relationships with every bale . . . or any bales. That’s understandable on many levels, but I’m also sure that my Michigan baler friend (well, almost) has good reasons for pulling a flat rack behind the baler. To him and all other Hay & Forage Grower readers, I simply say, “Have it your way!” •

Happy foraging,

Hay & Forage Grower would like to officially welcome Amber Friedrichsen to the role of associate editor. She joined the editorial team in May after graduating from Iowa State University with a double major in agricultural communication and agronomy. Friedrichsen grew up on a diversified farm near Clinton, Iowa, and is likely already familiar to many of our readers since she served as our editorial intern the previous two summers.

THE hills of Wisconsin’s Driftless Region were masked in a smoky haze from wildfires burning much farther north. Earlier that morning, it had rained. It wasn’t the best of hay drying days. Even so, by late morning, Ray called and said it was a “go.”

On this particular afternoon, 38-year-old Ray Liska was chopping alfalfa for Ocooch Dairy near Hillsboro, Wis. Chopping forage runs in the sixth-generation farmer’s blood. Between planting and harvesting their own crops, producing broiler chickens, and raising a family, Ray and his wife, Holly, own and operate a successful custom forage harvesting business called Apollo-Vale Enterprizes.

Liska grew up on a small Wisconsin

dairy farm, also near Hillsboro, but he was more interested in machinery than his father’s show cows. “When I was still young, my father suffered a stroke that resulted in right-side sight damage,” Ray recalled. “I started doing the harvesting with our pull-type chopper when I was about 12 years old because it was easier for me to look back at the header.”

Following high school, Liska attended technical college to study diesel and heavy equipment mechanics. One day while driving a dump truck during the summer, he noticed a self-propelled chopper in the field and decided that was what he wanted to do. In 2006, Liska bought his first truck and began hauling silage. He purchased a Miller Pro hay merger one year later and bought his first self-propelled chopper in 2010, which eventually caught on fire but not before logging 6,500 hours.

“Ray is passionate about chopping,” asserted Holly, a fourth-generation farmer who was also raised on a dairy farm. “Ray is jealous when someone else is out in the field and he isn’t. We can be in the middle of a deep conversation, and if Ray sees a silage truck on the road, I know the conversation is over. He will want to go and see where the action is taking place. ”

These days, Apollo-Vale Enterprizes is a full-service custom harvesting business that offers forage cutting, merging, chopping, trucking, and packing services. Harvesting alfalfa and corn silage comprise the large bulk of their business.

The business employs two full-time and three or four part-time workers, but additional help is also available

Ray Liska has been chopping forage since he was 12 years old. These days, he owns and operates a custom forage harvesting business along with his wife, Holly.

typically will merge at a slight angle to the way it was cut, which aids in picking the crop up off the ground.

With only one chopper, Liska can’t afford too many breakdowns. “If the chopper goes down for some reason, I have a pretty good gentlemen’s agreement with other harvesters in the area, and we will cover for each other,” the former president of the Wisconsin Custom Operators said. “I have rarely needed to call on someone else, but it’s good to know they’re available. It’s about 40 miles to our nearest dealer, so we do all of our maintenance and repairs in-house and try to keep parts in stock.

“I’ve never been married to new iron, but I do like to invest in the latest technology, which is sometimes only available on newer machines. Overall, though, our philosophy is to make a piece of machinery last by taking care of it,” he added.

customers depends on the individual farm. In some cases, he might be the one to make the call of when to start. For others, they want the hay knocked down every 28 days, regardless of growth stage.

For corn silage, Liska encourages the farm’s nutritionist to be on site to check the particle length and kernel processing early in the harvest process. This occurs even though he checks the feed daily himself. Liska said that he never has a kernel processing score below 80. “My feeling is that the nutritionist is the one who will work with the feed

during busy times such as corn silage harvest. “Labor has been a massive issue industry-wide, but we’ve been lucky and have always been able to find good employees locally,” Ray said.

Safety education has been one of Liska’s top priorities. He is heavily involved in the Wisconsin Custom Operators organization and their safety training program. All of his employees receive routine safety education,

When it’s time to hit the fields, alfalfa is mowed with a Claas triple mower. Swaths are brought together with two Oxbo mergers and chopped with a Claas Jaguar 970, which is equipped with a shredlage processor for corn silage.

“It’s definitely worth having two mergers on days when the hay is drying fast,” Ray explained. “My mower doesn’t have conditioning rolls, which saves fuel, offers less maintenance, and maneuvers easier. The downside is that the hay doesn’t always dry as fast in less than ideal conditions.” He also mentioned that the cut hay lays out in the same direction without conditioning rolls, so he

Liska also prioritizes taking care of his clients’ fields. All of the hauling units are equipped with flotation tires to minimize compaction and plant damage. His fleet includes four straight trucks; two forage boxes, which are used when conditions are excessively wet; and one semitractor-trailer. “There’s definitely evidence that the large-footprint tires make a difference even though they cost more and wear faster,” Ray asserted.

Liska services both dairy and beef operations. He likes to stay within a 25-mile radius but will go farther for the right job. The business has about a half dozen core farms that they harvest for every year, and then they will pick up additional farms as time allows.

Being in the Driftless Region, Liska said that you have to work harder to get feed harvested, as many fields are small with significant slope. “It helps that I’ve grown up here my whole life and I don’t know much different. It makes harvesting more expensive with the smaller, odd-shaped fields, but we are also diverse enough that there are rarely complete crop failures.”

Liska sees a push for higher forage diets on farms. “This makes timeliness of harvest really important, but the windows are narrow. Sometimes it’s too early to cut in the morning and by early afternoon, it’s too late,” he joked.

When Liska shows up to cut for his

and scrutinize my work, so I want them there. I want to have a relationship with the nutritionist. I learned this the hard way years ago when a nutritionist called me three or four months after harvest to complain about some aspect of the corn silage, and, by then, it was too late to do anything about it.”

Out of the harvest season, Liska keeps in communication with his customers regarding next season’s plans. The analytical custom operator also is interested in evaluating the job that was done the previous season in terms of forage quality, yields, and packing densities. From this information, he tries to improve the next year.

Liska charges his clients by the hour for each machine and truck, but there are different rates for hay crops and corn silage. “I’ve looked at using a per ton or per acre metric, but in such a diverse area with smaller fields, it would be difficult to charge that way,” he said. “Our efficiencies can change

dramatically within a few hours. That said, in the future, we may be able to incorporate an efficiency bonus whereby if we do better, then we can get paid more,” he noted.

“It has to be a symbiotic relationship between the farmer and us,” Holly added. “Depending on the customer, we only have so much control on the decisions that can be made. Ray is very much a data-driven guy, and he’s always trying to figure out a better way for both us and the farmer. But there are some customers who want to call all of the shots, so we can’t always control the forage quality or yield outcomes in those situations.”

Although running a custom harvesting business entails many long days during the growing season, Ray and Holly still find themselves with many other activities on their plates. They own several hundred acres of farmland near their home in Hillsboro where corn for silage, soybeans, and alfalfa is grown. This is land that the Liskas purchased from Ray’s parents.

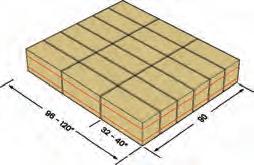

Liska sells his corn silage that is wrapped with an Orkel Dens-X compactor and sold as compacted silage bales. “It’s excellent quality feed that usually sells to smaller dairy and

beef producers who are just looking to supplement corn silage with what they are already feeding. We make 500 to 600 corn silage bales per year,” he noted. The alfalfa is either baled as dry hay or wrapped as baleage and then marketed. Since 2009, the Liskas also operate the family farm on his mother’s side in Cochrane, Wis., which is about two hours northwest of their home. There, they have two commercial chicken barns and grow 165 acres of corn and soybeans.

Ray and Holly, who were married in 2018 and share a strong Christian faith, have four children with a fifth due to be born shortly. Holly remains actively involved in the custom business by either working in the field or with business and employee management. She also homeschools their children.

To keep their business viable, both Ray and Holly are strong activists for regulation reform in the state. Holly has testified in front of the state legislature for issues such as getting the length of a farm service commercial driver’s license (CDL) extended to 210 days to better accommodate the length of the harvest season. Such a change would match the federal regulation.

The Liskas are also concerned about other regulations that impact agriculture, such as those that define agri-

cultural equipment and overreaching climate change policies that add to the cost of operating. “We feel burdened to ensure that our children have a good future in life and agriculture if they want it,” Holly said of her passion for regulation bird dogging.

Although Ray has a degree from the technical college, he attributes most of his success to the mentors he has had in his life. That includes his dad, other local farmers, and the relationships he has forged by being a member of the Wisconsin Custom Operators organization.

As for future plans, the Liskas are satisfied with looking for opportunities. “If the kids want to get involved someday, maybe their outlook will be different,” Holly surmised. “Both our 12-year-old boy and 14-year-old daughter are already involved in helping where they can, including the operation of equipment. If that interest continues into their young adult years, we’d like for them to work for someone else before they come back here permanently, though.”

Added Ray, “We, like every other farmer, are always looking for better ways to do things, improve efficiency, and make money. I always joke that someday the merger and chopper will be one machine.” In the meantime, the Liskas are just happy for the freedom to work and worship side by side as a family. •

CORN silage is a cornerstone of modern livestock nutrition, providing a highly nutritious and energy-dense feed option. Corn silage starch plays a critical role in meeting the energy requirements of livestock. Therefore, optimizing starch at harvest is essential for maximizing the nutritional value and performance of dairy and beef cattle.

Kernel processing is a pivotal component in unlocking the full potential of corn silage starch. Kernel processors break or crack the corn kernels at harvest, thereby enhancing starch accessibility during animal digestion. Proper kernel processing enables livestock to

more efficiently utilize starch, leading to improved nutrient utilization and animal performance.

Most modern forage harvesters are equipped with specialized processors that crush kernels between two abrasive steel cylinders. These rollers rotate at different speeds, which enhances kernel size reduction. The roller gap can be changed to adjust the aggressiveness of the processing during harvest. The cost of a gap that is too wide is lost starch out the back of the cow. Too narrow a gap might cost you extra time and fuel at harvest. Current guidelines suggest that a gap setting of 1 to 3 millimeters (mm) is optimal for most conditions.

While kernel processing makes starch accessible by exposing more kernel surface area, the digestibility of corn silage starch is the metric that determines how quickly accessible starch is degraded by microbes. The worst scenario is to have corn silage with large pieces of kernel that are low in digestibility. There are many factors that can impact starch digestibility and understanding them is important to optimizing starch digestibility and harnessing the full energy potential of corn silage.

Grain maturity: Harvesting corn silage at the ideal grain maturity stage is crucial for maximizing starch digestibility. As corn kernels mature, starch content rises, but its digestibil-

ity declines. By harvesting corn silage at the 1/2 to 3/4 milkline, a balance is struck between starch content and digestibility. Harvesting too late impairs digestibility, but harvesting too early lowers yield and whole-plant digestibility due to a lower starch concentration. Hybrid selection: Since kernel composition is largely genetic, the choice of corn hybrid significantly affects starch digestibility. More specifically, kernels that genetically express greater amounts of floury starch tend to be more digestible than kernels that produce the hard, vitreous starch characterized by flint corn. Advances in genetic selection have led to the development of hybrids with superior starch digestibility traits. Some of these hybrids even have a recessive trait that results in kernels that are completely composed of floury starch. The downside is that these hybrids tend to produce lower overall starch content as compared to conventional dent corn.

Moisture content and fermentation time: Plant moisture content at harvest is a critical factor influencing starch digestibility. Not only does it relate to kernel development, but adequate moisture is required for fermentation processes to occur that stabilize the silage for storage and feedout. These processes also have the effect of enhancing starch digestibility over time. Thus, silage that is overly dry or fed out within several months of harvest is more likely to suffer from poor starch digestibility. The optimal silage moisture content is around 65%.

The question of how to assess the quality of starch in silage has been highly debated over the years. The obvious gold standard is to feed the silage to cows and measure the actual starch utilization by the animal. While that works from a research standpoint, it isn’t too practical for the average farmer seeking to produce better feed.

Most farmers and nutritionists would have corn samples analyzed for 7-hour starch digestibility and perhaps kernel processing score. Measures of starch digestibility can be informative, but in vitro measures of starch often yield inconsistent results. Even the more precise assays available give an incomplete picture by failing to account for particle size. The current methods for determining the kernel processing score do

provide a measure for starch particle size, but this measure doesn’t account for differences in kernel composition.

A new metric for assessing the quality of silage starch was recently evaluated in a study at the Miner Institute in Chazy, N.Y. The assay has been termed “soluble starch” by the forage-testing lab that developed it, but it is really just a measure of the washout fraction of starch that easily moves out of the sample when water is added.

The exciting part about this new measure is that it appears to integrate both particle size and digestibility into a single number, providing an assessment that could correlate well with animal response. Our study results showed that soluble starch increased with fermentation time and was higher with a floury kernel type (Figure 1). This is the very same pattern that was observed with the starch digestion rate (Kd) measured in the study. Furthermore, a slight adjustment to the processor roller gap resulted in a measurable difference in soluble starch in unfermented samples.

Optimizing corn silage starch at

harvest is a vital consideration for maximizing the energy potential and nutritional value of corn silage. Effective kernel processing, which is achieved with modern equipment and proper adjustment, plays a pivotal role in enhancing starch availability. Alongside kernel processing, other factors such as grain maturity, hybrid selection, moisture content, and length of fermentation significantly impact starch digestibility.

Optimizing these factors leads to improved energy utilization, feed efficiency, and performance for animals on corn silage diets. Utilize the best indicators available to make informed decisions about starch quality. Harnessing the power of corn silage starch sets the stage for enhanced profitability and sustainability. •

IT’S the new “sexy” forage, also known as the cocktail mix; it’s mysterious, unknown, and risky. She is a femme fatale. Seductive, she draws her lover into a compromised relationship. Once she is planted, there are many promises — but no guarantees. Dramatic? Perhaps, but before you start dating this forage, be ready for a rocky relationship with highs and lows.

The cocktail mix moniker is, of course, unspecific. In the field, we think of a cocktail as a mix of warmand cool-season annual grasses and legumes. With such a generic, although alluring, name, it’s not surprising that cereal forages, clovers, sorghums, ryegrasses, and other species all come into play. By planting a mix, it is hoped to take advantage of various growing conditions. In some cases, yields in excess of 4 tons of dry matter per acre have proven to outperform alfalfa.

Following are some considerations that will help you better understand this new relationship and ensure that cocktail mixes meet your expectations.

■ Forage quality and yield: I have seen the Twitter post documenting a relative forage quality (RFQ) of 240 for a cocktail mix. There are four questions that must be asked regarding such a claim:

1. What was the cost per ton of dry matter? Lost in the discussion at times with various alternative forages is the actual cost. If five to six cuttings are harvested, the tractor and equipment are driven across the field five to six times. How does this influence the actual cost per ton of dry matter averaged across the year?

2. What was the yield? Regardless of whether you have an annual grass, alfalfa, or corn silage, there is always the balance of quality versus yield; you need a certain number of tons for forage (and fiber) to feed cows for an entire year.

3. Do you want to feed rocket fuel? Forage that is extremely high in quality can work in some diets, but it likely cannot be the sole forage; cows have a need for undigestible forage (undigestible neutral detergent fiber [uNDF]) to maintain proper rumen function.

4. Is this repeatable? One Twitter post from a random farmer doesn’t tell you if this will work on your farm with

your soil conditions in both a wet or dry year.

■ Seasonal flux: Most farms might have some fields planted to a cocktail mix while maintaining alfalfa in others — call it risk management or a lack of commitment to the relationship. This leads to a fundamental flaw in the system; namely, there becomes a lack of synchronicity between your alfalfa forage cuttings and the cocktail cuttings. How do you manage four cuttings of alfalfa and multiple cuttings of the cocktail mix? One strategy is to store the cocktail mix separately. On large dairies, bunker and pile space is at a premium; multiple cuts are then stored in front of other cuts, leading to more frequent changes in forage quality.

Storing cocktail forages separately in bales or bags can be an option, but this invariably leads to inconsistent feed coming out of storage. I think there are two reasonable options to help solve this issue. First, if possible, time the cuttings to coincide with your alfalfa and layer the forages in the bunker or pile, even though yield might be compromised slightly to sync cuttings.

Layering isn’t pretty, but it can be effective. Packing and more packing

is critical. If a quality facer is used, and the forage is pushed and “mixed” adequately with a bucket, a forage mix can be fed that is consistent day to day and will change slowly over a longer period of time. Cows (and nutritionists) thrive on consistency. If the same bunker of feed can be fed for four months, there is time to make small adjustments based on cow response. If forages are switched every four to six weeks, then there is a need to constantly “chase” the cow response. Second, if the feed is stored in bags or small piles, use this forage at a low feeding rate (less 5% of dry matter) to limit the effect of variability on the cow.

■ Allocation of forages: With cocktail mixes, there will certainly be times when the quality does not meet high-producing cow standards. Faroff dry cows and bred heifers can be a great place to allocate these forages. However, for farms without heifers, it is easy to become heavy on a forage that has a limited need.

■ Consistency: Most nutritionists are not in love with the sexy cocktail mix but rather prefer her bland looking sister — corn silage. While we argue with each other over brown midrib and conventional hybrids, we mostly enjoy the stability in the corn silage relationship because we generally know what to expect. Yields and quality vary with corn silage, too, but there is usually just one change a year. For the highest producing herds, consistency is often the common theme. Will a cocktail mix work in your system to maintain this consistency?

■ Harvest targets: Harvest targets for corn silage and alfalfa are well established. Alfalfa scissors clippings and fall dry-down reporting for corn silage have become standard practices in many areas. But what is the target for cocktail mix blends?

For alfalfa, we often target 33% to 36% NDFom. For some grass blends, this is far too low. A high-quality grass with high fiber digestibility might have an NDFom of 42% to 44%. One option

is using a combination of aNDFom and uNDF240 (undigestible fiber) with a target of 48% to 52%. For example, alfalfa at 34% NDFom and 16% uNDF240 has a combined value of 50; grass forage at 44% NDFom and 7% uNDF240 would have a combined value of 51. Using the 48% to 52% combination parameter might be helpful in evaluating timing of harvest across multiple, variable fields. I’ve seen combined forage bunker silos with 40% NDFom and 10% uNDF240 that fed well.

Starting a relatively new relationship with a sexy forage can work, but keep your eyes wide open to the potential for variable yields and forage quality. •

ITALK with a lot of farmers and ranchers all across the country who are trying to transition away from hay dependence toward more dormant-season grazing. A common question I get is how to convert an alfalfa hayfield into a grazable pasture. Sometimes the field may still have quite a strong alfalfa stand while others may be fields in decline.

Grazing an alfalfa field is a pretty scary prospect for a lot of livestock producers. The fear of bloat is pervasive throughout our industry. I have long maintained that the fear of bloat costs cattle and sheep producers far more than the actual losses due to bloat. That is financially true on an industry-wide scale. It is not quite so true when you’re the one who walks out one morning to find fifty dead animals.

When bloat does occur, it is usually operator error. In other words, the bloat event was probably preventable if the manager had been paying more attention to what was going on. Stage of maturity, timing of the pasture move, frequency of moving, and severity of use are all factors that can set up a bloat event. There is also a strong animal genetic component. We can intentionally select for bloat resistance.

When we decide to convert an alfalfa field from hay to pasture, one of our first objectives is to get something else growing out there besides just alfalfa. As little as 15% grass component in an alfalfa field has been shown to reduce the occurrence of bloat. If alfalfa is the only legume in the pasture, my preference is that it

be less than 50% of the total biomass production. The remaining production should be from grass and high-tannin forbs that can substantially reduce the likelihood of bloat occurring even in bloat-susceptible herds.

A pure stand of alfalfa is made up of individual alfalfa plants that have strong crowns. Plants are generally spaced apart with open ground between the crowns. A healthy, productive alfalfa stand typically has four to seven mature plants per square foot. There is a lot of space in between plants where other species can have a chance to grow. With the advent of Roundup Ready alfalfa varieties, the possibility of later summer weed competition has already been minimized.

Timing of interseeding depends on your location. If you plan to interseed cool-season grasses, we generally plan for an August through early September seeding date. No-till drilling immediately following hay harvest has worked well for us in environments from Idaho to Missouri. Success rate is very high in irrigated environments. In the Intermountain region and the Northern Plains, we seed in mid-August with irrigation following the drilling. In the Midwest and eastern states, we are generally seeding the last week of August or first week of September and hope for rain.

The reason we do the late-summer seeding when putting grass into alfalfa is based on the respective growth habits of the different species. In the spring, alfalfa grows really well and is competitive. It is hard to get grass seedlings going while alfalfa is growing full tilt. In later summer, alfalfa is heading

for dormancy as days get shorter and nighttime temperatures dip. Cool-season grasses, on the other hand, want to grow in those same conditions.

If you live in a warmer environment and are considering interseeding warm-season grasses, then we use a spring-seeding strategy. Depending on location, interseed the warm-season grasses following either the first or second cutting of the alfalfa. In either case, cut the alfalfa in prebud or bud stage. This will somewhat weaken the alfalfa and slow recovery.

Once the interseeding is done and the grass seedlings emerge, it is still important to keep pressure on the alfalfa to minimize competition. A basic principle of grass-legume relationships is that short postgrazing residual favors legumes while taller residuals favor grass. Often, another potential alfalfa hay crop will regrow after the interseeding. Cutting this growth for hay is a good idea, but make sure to set the cutting height to be at least 4 inches. Six inches is even better because you are likely to be cutting above the tops of the grass seedlings at this height.

Alfalfa is far from being my favorite legume for grazing. What we have done when the alfalfa has faded to about 30% yield contribution is broadcast seed of various clovers and birdsfoot trefoil into the pasture. Alfalfa cannot be maintained in a stand through natural reseeding. All of the clovers, vetches, and trefoil can be maintained indefinitely through natural reseeding. At some point in the summer, a 65- to 80-day recovery period is needed for these legumes to make seed. We have maintained strong legume stands for more than 15 years with natural reseeding. •

JIM GERRISHThe author is a rancher, author, speaker, and consultant with over 40 years of experience in grazing management research, outreach, and practice. He has lived and grazed livestock in hot, humid Missouri and cold, dry Idaho.

CARBON is fundamental to all life. It forms the backbone structure of carbohydrates (composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen), which are the initial products from the miraculous process of photosynthesis. Energy from the sun is captured within chloroplasts of green plants using water taken up from the soil and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This starts the carbon cycle with the formation of sugars. These sugars or simple carbohydrates are transformed in plants to various complex carbohydrates, oils, proteins, and numerous other compounds specific to each plant group.

Animals and humans that consume these plants rely on the energy and phytochemicals embodied in these plant compounds for growth and daily maintenance. Soil microorganisms clean up the remaining carbon embodied in plant and animal residues to cycle carbon back to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. Of course, there are many variations and complexities in the carbon cycle along the way, but the basic pathway is a rather straightforward and simple process. Carbon is the common currency along all stages of this cycle.

Soil carbon in the eastern U.S. is primarily composed of organic carbon, which is carbon that was once living in plants and animals and has since been transformed by soil microorganisms feeding on these primary sources to form decomposition by-products of soil organic matter. Soil carbon in the western U.S. can also be composed of inorganic carbon from carbonates that precipitate with soil cations like calcium and magnesium.

Soil organic matter is composed mostly of carbon. In fact, carbon makes up 58% of soil organic matter while nitrogen makes up about 5% of soil organic matter. These two elements are often measured to determine the percentage of soil organic matter. The hundreds of billions of individual bacteria and fungi in a teaspoon of soil are composed of carbon.

The living component of soil may only compose 1% to 5% of total soil carbon.

The large nonliving component of soil contains most soil organic carbon. Nonliving components of soil carbon can be in small organic matter pieces called particulate organic matter, in dissolved organic matter that makes standing water turn the color of tea, in humic matter that is highly stable and doesn’t break down easily, and in various inert organic components such as charcoal following burning of plant biomass.

ammonium, iron, and aluminum. Soil carbon buffers against pH swings to keep acidity in a more acceptable range for plants. Soil organic matter complexes metals to enhance dissolution of minerals, enhances availability of phosphorus, helps inhibit the loss of micronutrients, and reduces toxicity of heavy metals. Soil organic matter alters biodegradability, activity, and persistence of pesticides.

Soil carbon in organic matter offers a reservoir of metabolic energy to drive biological processes. Soil organic matter is a source of organic nutrients that are slowly released to plants via microbial activity. Soil carbon can enhance and inhibit enzymes that transform plant-available nutrients. High soil carbon content provides ecosystem resilience, enhancing the ability to recover from various disturbances, such as drought, flooding, tillage, and fire.

Soil carbon is important to farmers, and it should be important to the public, because it is a vital determinant of ecosystem properties and an essential mediator of ecosystem processes and functions. This means that this relatively small component of soil provides many of the features of healthy soil needed to make it an excellent growing medium for forage crops and pastures, as well as to protect the environment and provide ecosystem stability. The mass of soil organic matter may compose from 1% to 10% of total soil weight, but this depends highly on climatic conditions, soil texture, landscape setting, and land management.

Carbon gives soil a dark color to absorb heat. Soil carbon has low solubility, ensuring that organic matter inputs are retained and not rapidly leached from the soil profile. Soil with high carbon content acts like a sponge to retain more water for plant growth, and it stabilizes soil structure to provide pore space for microorganisms and various soil critters.

Soil with a high carbon content enhances the cation exchange capacity that aids in the retention of cations like calcium, magnesium, potassium,

It is increasingly recognized that improved forage and grazing land management can significantly benefit the carbon status of a soil, thereby promoting greater soil health features and ecosystem resilience. Climate change threatens ecosystem process. Managing soils with greater soil carbon content will help farmers limit the negative consequences of climate change. Better forage management can be viewed as an effective adaptation strategy to climate change, but it’s also an important mitigation strategy when deployed over large areas — carbon in the atmosphere is transferred to fixed carbon stored in soil organic matter. In the next issue of Hay & Forage Grower, I’ll describe in more detail how land management can affect soil organic matter content. •

ALAN FRANZLUEBBERS

The author is a soil scientist with the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Raleigh, N.C.

MANAGING where herds and flocks graze is an age-old challenge of livestock husbandry. For more than 10,000 years, addressing this problem involved intensive herding or barriers made of sticks and stones. In the late 1860s, a major innovation involving a metal wire armed with sharp metal points known as “barbed wire” was introduced. In the 1930s, a wire carrying an electric charge to deter animals was patented and produced the “electric fence.”

Recently, a “virtual fence” with electric pulses delivered to the animals through collars they are wearing has been conjured to replace physical barriers and wires. The idea of fences that can be constructed in a few minutes on a computer interface, requiring no annual maintenance and applied on all types of terrain, has captured interest and skepticism among many ranchers. With a virtual fence, livestock managers draw pasture boundaries on a computer to produce a location reference map. Livestock wear an electronic band, chain, or collar around their neck and a sound is emitted when the animal approaches a virtual boundary based on their GPS location. An electric shock is delivered through the collar if the animal does not turn away from the boundary. Several companies now offer

GPS-based virtual fence systems, which are listed in the accompanying text box.

In the United States, Vence is the most widely available system, with on-ranch testing that started in 2019. Virtual fence has arrived, although there are still a few stones in the road to this becoming a future reality.

Though physical fences are necessary along property or unit boundaries, the ability to easily revise and move a virtual fence will provide unlimited opportunities for cross fencing to facilitate rotational grazing. Fences are also necessary to integrate livestock into crop systems to graze off cover crops, after-harvest residue, and failed crops.

In addition, targeted grazing practices for weed control or wildland fuel management to reduce wildfire could be accomplished with virtual fencing.

Building and maintaining fences is costly. Construction of new fence generally ranges from $1,000 to more than $10,000 per mile, depending on the type of fence and terrain. The time and expense to build new and maintain existing fences is a significant enterprise investment and has fueled interest in electronic virtual alternatives.

Fortunately, it is not difficult to get animals to respect virtual fences. Most animals require only a few electric pulses before learning the relevance of the audio warning and quickly turn

away to avoid an aversive electric stimulus. In research studies with 21 yearling bulls at the University of Idaho, we found that animals initially tested or disregarded a virtual boundary, but all animals were contained in a pen after just three days of experiencing a virtual gate (see Figure 1).

Protocols can also train animals in groups rather than individually, making the application of virtual fence to herds or flocks more feasible. Additionally, initial studies show little or no evidence of stress to animals while grazing a virtually fenced pasture. Plus, some systems allow ranchers to view animal locations and track animal health attributes such as heart rate and body temperature.

Virtual fence is a new technology that will undoubtedly become more effective and affordable in the years to come; however, results of initial on-the-ground applications revealed several challenges and shortcomings of virtual fence. The greatest source of failure in early tests was the loss of neck collar devices, with several applications on Western ranches reporting devices that fell off or failed on up to 30% of the herd.

Some collars may have been initially fitted and mounted too loosely, allowing the animal to rub or shake the collar off. Certain initial collar designs also failed because screws on the collar came loose and fell off or devices sustained damage from the animal or water. Most of these initial design flaws have been corrected, though loss or failure of collars is a continued concern.

Other challenges voiced by livestock producers include the time required to install and manage a virtual fence system. It takes considerable effort to prepare the devices for deployment and get collars attached appropriately to animals. Some devices also require an occasional battery change, which can require significant time, especially in larger herds. Finally, it was noted in early field applications that finding lost or damaged collars and replacing them on the animal was another considerable time investment.

Animal noncompliance is a persistent concern with virtual fences. Although most animals can be trained to respect virtual fences, a few animals do not respond appropriately to the sound or electrical stimulus. Even among well-trained and responsive

animals, a virtual boundary may become less effective as forage availability becomes limited compared to the other side of the virtual fence or when uncollared calves leave the virtual pasture and their mothers cross the boundary to be reunited.

Additionally, the currently available options of virtual fence are not cheap. The cost of virtual fence is highly dependent on the number of communication base stations required, the availability of cellular communication, the subscription fee or purchase price, the cost of batteries, and the expected product lifespan. It is difficult to generalize, but recent costs can vary from $75 to $300 per cow. Though the cost of virtual fence will undoubtedly come down with technological advances, it is currently not a low-cost fencing solution.

Much is yet to be learned to hone the idea of virtual fence into a highly efficacious system for grazing animals. We need to more fully understand how animals will respond to virtual fence depending on their breed, age, sex, or weight. Developing an effective and ethically appropriate virtual fence system will also require greater knowledge of visual or audio cues that best indicate a virtual boundary. We also need specific details on the contiguity between a warning sound, an aversive electoral stimulus, and the intensity of electrical stimulation needed to hasten animal learning.

Our research being conducted at the University of Idaho and Washington State University has focused on design-

ing a ruggedly simple and reliable device based on low-cost radio communication. We are examining aspects of animal physiology to reduce the level of electrical stimulation required to deter animals from crossing a virtual boundary. Our research indicates that lower levels of electrical stimulation are required to elicit an animal response when delivered to the ear compared to the neck or nose (see Figure 2). Therefore, we are pursuing all possible ways to lower the weight and energy requirement for animals to respect a virtual boundary. This includes examining training protocols and audio and visual cues to reduce the number of electrical stimulus events needed to effectively contain animals.

Consider also that it may be simpler, and require less energy, to keep animals out of areas rather than containing them in a virtual pasture. Virtual fence is a promising technology to keep livestock away from hay bales or stacks until they are needed as feed. Virtual fence has also been applied to reduce livestock grazing in ecologically important areas such as riparian zones or springs. It can also facilitate restoration and revegetation in forest regeneration sites, and more recently burned areas. Virtual exclusion zones could also reduce human-livestock conflicts by keeping livestock out of areas with high value to humans such as recreation sites and historically important or archaeological sites.

The path toward an effective virtual fence for grazinglands is being paved. As we learn more about animal behavior,

we will be better able to select and train animals to adapt and live within virtual pastures. Advances in battery and communication technologies will provide more effective and less expensive systems. Robust virtual fencing technology could, like barbed wire over a century ago, be a catalyst that transforms livestock operations and improves economic and environmental sustainability for ranchers across the globe.

Ongoing research is being conducted by Karen Launchbaugh (grazing behavior), Dev Shrestha (agricultural engineering), Jason Karl (rangeland technology), Katherine Lee, (agricultural economics), and Jim Sprinkle (animal science extension) from the University of Idaho; and by Gordon Murdoch (animal physiology), Tip Hudson (rangeland science extension), and J. Shanon Neibergs (agricultural economics) from Washington State University. •

Virtual fence vendors

Vence (vence.io)

eShepherd (bit.ly/HFG-gallagher)

NoFence (nofence.no/en/)

Halter (halterhq.com)

Corral (corraltech.com)

The author is a professor at the University of Idaho Rangeland Center in Moscow.

CLINICAL hypocalcemia, also known as milk fever or periparturient paresis, is a metabolic disease that affects dairy cattle productivity and welfare. This disease occurs around calving when the mammary gland draws calcium from the blood for colostrum secretion immediately after calving. In many cases, the draw of calcium from the blood is sudden; its replenishment to normal levels is not quick enough, and clinical signs like wobbly gait, recumbency, or both occur. Clinical hypocalcemia is a concern for the dairy industry given it can reduce milk production and enhance the risks of other periparturient disorders like metritis, ketosis, and displaced abomasum.

One of the few approaches for preventing hypocalcemia is feeding acidogenic products during the prepartum period. Starting to feed acidogenic products about three weeks before the expected calving date decreases the dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD), which induces a metabolic acidosis that stimulates calcium metabolism. Reducing the DCAD to negative values implies that the chemical equivalents of cations like sodium and potassium are less than the chemical equivalents of anions like chloride and sulfur. We primarily want lower concentrations of sodium and potassium and greater concentrations of chloride and sulfur in the diet.

Obtaining a desired negative DCAD in prepartum diets can be challenging depending on the forages included, and this challenge mainly relies on the concentration of potassium in the forage. Potassium is the fourth most abundant element in feeds and forages after carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen, which are the main elements in proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. Grass hay typically has lower concentrations of potassium than alfalfa hay, so nutritionists commonly avoid including alfalfa hay in prepartum diets. But should they?

The National Alfalfa and Forage Alliance (NAFA) funded a research project

through its Alfalfa Checkoff program in which we challenged the concept of avoiding alfalfa hay when feeding dairy cows in the prepartum period. We hypothesized that prepartum diets containing alfalfa hay can be fed with similar results to feeding prepartum diets containing grass hay.

Under this hypothesis, we performed a feeding trial in which we fed 79 dry cows prepartum diets containing either grass hay or alfalfa hay in combination with either calcium chloride or polyhalite as acidogenic products. The diet containing grass hay and calcium chloride is commonly fed at the Virginia Tech Dairy Complex and served as a control diet.

We bought and imported the alfalfa hay from the Great Plains, whereas we produced the mixed grass hay on-site at Virginia Tech. All diets contained a DCAD of -190 mEq/kg dry matter (DM) or less, which we considered quite acidic. Cows receiving prepartum diets containing alfalfa hay consumed similar amounts of DM to cows consuming prepartum diets containing grass hay.

To determine the effect of feeding prepartum diets with negative DCAD, we measured the pH of animals’ urine before and after feeding the acidogenic diets. The first observation was feeding all diets substantially reduced urinary pH. A second observation was cows consuming alfalfa hay had the lowest urinary pH values. These two observations indicate that we successfully acidified the urine of the cows regardless of the type of hay included in the diet.

To evaluate the effect of the diets on hypocalcemia, we sampled animals’ blood and measured its calcium concentration every week during the prepartum period, at calving, and on Days 1, 2, and 3 postcalving. In all cases, the concentration of calcium in blood did not differ, indicating that hay type did not affect hypocalcemia.

A final observation was only one of the 79 cows developed hypocalcemia. This cow consumed a diet containing alfalfa hay, but this observation is not

significant based on the size of the experiment. Moreover, 12 of the 79 cows had asymptomatic hypocalcemia (plasma calcium concentrations <5.5 mg/dL) at least once between Days 0 and 3 after calving, although no associations existed between diets and the frequency of hypocalcemia.

Based on these results, including alfalfa hay in prepartum diets did not harm cattle. In fact, even though the alfalfa hay had a greater concentration of potassium than the grass hay (2.5% and 1.9%, respectively), the alfalfa hay had a DCAD similar to that of the grass hay (292 mEq/kg of DM and 290 mEq/kg of DM, respectively).

According to the National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), the DCAD for mature legume hay is 387 mEq/kg of DM and 187 mEq/kg of DM for mature grass hay, which agrees with our original hypothesis of observing a much higher DCAD for alfalfa hay than for grass hay. However, in our study, the DCAD of the alfalfa hay was lower than expected and the DCAD of the grass hay was higher than expected.

Beyond the alfalfa hay versus grass hay debate, we learned a few key concepts in this study. The most relevant is rather than the type of forage, the DCAD of a specific forage is critical to determine if it is appropriate to include in prepartum diets. Forage analyses are necessary for this decision. The other takeaway is that the DCAD of the forage might be affected by soil fertility, fertilization choices, or both, although more research is warranted in this •

THINK about picking out a person or two in the stands at a baseball game and expecting them to be representative of the entire crowd that day. This probably seems a bit outlandish, and it should. We readily recognize that one or two people, either for good or for bad, do not represent the crowd at large in appearance, beliefs, or opinions. However, I’ve used this metaphor in the past to explain the challenges we face in forage and ration sampling.

Dairy and beef farms harvest, store, and feed forage and rations by the tens of thousands of pounds. Collecting a 1 pound composite forage sample and expecting this to appropriately represent 20,000 pounds of feed is challenging to say the least. This isn’t to suggest that feed sampling and testing is useless, but we need to be cognizant of what a single sample represents. Then we can proceed accordingly with an improved statistical understanding and approach to nutritional or quality data and expectations.

Thanks to research from Bill Weiss and Norm St-Pierre at The Ohio State University, we have a concrete understanding of the factors that contribute variance to feed sampling. Their recommendations include additional sample repetitions when getting into new feeds, yet few practice their advice. Single samples don’t get the job done and need to be interpreted with caution.

Building upon these findings, a team of researchers I helped assemble at the University of Wisconsin and Rock River Laboratory found that a majority of sampling variance is tied to the farm. In fact, the sampling variance is 10 to over 60 times greater at the farm relative to the lab.

What’s the practical take home point? The feed testing laboratory technician contributes relatively little variation to results and far more variation comes from sampling at the farm.

Back to the point raised above: This doesn’t mean that sampling is useless; however, we need basic statistical training to improve the way we make decisions or spend money tied to feed or

ration testing.

Last year at the High Plains Dairy Conference in Texas, I brought a scope and rifle metaphor into an invited seminar I gave discussing hidden nutrition and economic opportunities. I contend that determining your feed moisture or nutritional value is like sighting in a rifle with a new scope. Experience shows that mounting the scope on the rifle, taking a single shot, and then making adjustments to zero in the scope will lead to erroneous adjustments. Now think of feed sampling like single rifle shots with a newly mounted scope.

Single samples — even composites — are just one estimate of what the feed’s true value is in terms of moisture or quality. As described above, sampling variance at the farm and laboratory contribute a bit of variation to single samples. There is no way to eliminate these variance factors just like there is no way to shoot a perfect single shot and then adjust your scope. We readily recognize that three to five shots are needed to sort out a pattern, and only then can we proceed to adjust the scope to zero. Feed testing is no different. Multiple samples or observations need to be accounted for to represent the population of feed analysis results more accurately.

Nutritionists often integrate several sample results when making decisions; however, these results sometimes span weeks to months. In adopting the approach here, the three to five observations should be made over a reasonable period of time relative to

the decisions at hand. For some, this time period is week to week, but for others, it’s monthly or quarterly.

Stopping short of a course in statistics, understand that your feed quality can be thought of as a population, just like the population of people at a stadium described above. The population of feed quality may be defined by a truckload, a lot of hay bales, or 10,000 tons of feed under plastic. The feed quality population may also be defined by a week’s worth of feed or a ration fed to a pen or herd. This is a different concept for us to think about, but the population needs to be defined. Then, with the population in mind, we can recommend an appropriate sampling scheme to accurately characterize the population.

The recommended sampling approach to define the feed moisture or quality “population” is no different than sighting in your new scope. I recommend three to five observations to accurately get a handle on your feed’s value. This may mean several samples from a lot of hay, or several samples collected over a meaningful period of time while feeding out a forage (for example, two to four weeks).

Take this topic up with your nutritionist or hay broker to chart out a strategy. Forward thinking dairy and beef feeders are locking into this approach, recognizing sizable swings in moisture or nutritional value that have been previously covered up due to insufficient nutrition data.

In closing, build upon your current sampling program to include more observations over time prior to making high-value decisions. Interpret single sample results with caution, recognizing one analysis is just like sighting in a new scope with a single shot. •

JOHN GOESERHay & Forage Grower is featuring results of research projects funded through the Alfalfa Checkoff, officially named the U.S. Alfalfa Farmer Research Initiative, administered by National Alfalfa & Forage Alliance (NAFA). The checkoff program facilitates farmer-funded research.

THE use of genomic and phenomic technologies in alfalfa breeding programs could help enhance alfalfa yield, said Charlie Brummer, Center of Plant Breeding Director at the University of California (UC)-Davis.

Genetic markers, genomic predictions, drone-based sensors, and different statistical tools were used in his work to maximize alfalfa yield, funded by the Alfalfa Checkoff. Genetic markers were used to screen plants “so we could see which ones were the best at making great progeny (half-sib families), then cross them for a better estimate or idea of what’s going to be a good, high-yielding cultivar,” Brummer said.

He experimented with 200 half-sib families from UC-Davis breeding populations in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, each year evaluating them for vigor and yield. By 2021, individual plants and half-sib families were identified with high biomass yield to produce experimental cultivars.

“We’ve made progress. We know all the steps of the process, and we’ve applied them all to our current breeding,” Brummer said. “Now it’s a matter of producing seed to document the changes that we think happened, and seeing the gain that we think we’ve made in terms of yield.”

This summer, plants are being intercrossed, then evaluated in the next year under full and deficit irrigation and saline and nonsaline irrigation. “It will still take a couple of years after we get the seed of populations until we get trial results,” Brummer pointed out. “Everything looks favorable that we are able to improve yield, and that

these technologies can be applied to commercial breeding programs. But it’s going to be incremental yield gains; it’s not going to be an immediate 10% jump,” he added.

Brummer hopes the research will also help speed up the alfalfa breeding process. He explained, “We used a whole suite of technologies, including genetic markers for whole genome analysis to predict yield and drones to estimate yields remotely rather than having to harvest plots, plus better statistical techniques to analyze data more robustly.”

1. Individual plants and half-sib families with high biomass yield were identified to form new experimental cultivars. Populations selected for vigor from spaced plant trials will be compared with those selected for yield from sward trials. DNA marker data for two populations will be used for marker-only selection in early 2022.

2. Collecting data using multispectral and hyperspectral cameras (on drones) in 2019, 2020, and 2021 was useful for predicting yield in certain harvests. In other harvests, especially in the spring of the first year when all plots looked good or when yield variation among families was small, the relationship between drone data and actual yield was moderate. Predicting yields in some harvests, for example by measuring one replication with a harvester and predicting other replications without taking yield measurements, could expand the number of families or populations evaluated at a given time. Because breeding is a numbers game, evaluating more families should result in better genetic gain for yield.

only

yield data

Figures: Brummer’s research shows drone-based predicted yields (right) can closely compare to actual measured yields (left), suggesting the value of using drones to speed data collection of some harvests.

Drones worked well in collecting data. “The time savings and money savings in flying drones rather than harvesting hundreds and hundreds of plots is fantastic,” Brummer said. The challenge is figuring out how to process the data in a streamlined way.

“We need to better understand how the plant grows and how we could potentially modify it and think about modifications that could lead to higher

yield,” Brummer said. “With drones or other types of sensors where you could possibly get real-time data all day long, what does that tell us? Could we use all those data to potentially change our evaluations and our selections from what we do now? That’s a challenge,” he asserted.

Another challenge is the crop itself, Brummer noted. “Working on a perennial crop takes time; it’s hard to do

Alfalfa Partners - S&W

Alforex Seeds

America’s Alfalfa Channel

CROPLAN

DEKALB

Dyna-Gro

Fontanelle Hybrids

Forage First

FS Brand Alfalfa

experiments on a yearly basis or even over a couple of years. It takes time to do experiments in breeding, develop new populations, then test them, so things don’t move as fast as any of us would like,” he said.

Brummer also pointed out that this research wouldn’t exist without grower checkoff funding, “It’s hugely important to those of us in the public sector to have that source of funding.” •

Gold Country Seed

Hubner Seed

Innvictis Seed Solutions

Jung Seed Genetics

Kruger Seeds

Latham Hi-Tech Seeds

Legacy Seeds

Lewis Hybrids

NEXGROW

Pioneer

Prairie Creek Seed

Rea Hybrids

Specialty Stewart

Stone Seed

W-L Alfalfas

IF YOU are familiar with the television series, “Extreme Makeover: Home Edition,” you will recall how every episode begins with a team of carpenters, painters, and plumbers gutting a dilapidated house from the inside out. Fast forward to the end of the show and the host yells “Move! That! Bus!” into a megaphone to reveal a new version of the old home with updated roofing, siding, flooring, and furniture.

In 2018, Nick and Annie Rodgers found themselves starring in their own version of the show when they acquired

a 70-acre farm in Montrose, Mich. Instead of using a hammer and nails to repair a ramshackled building, though, the Rodgerses used livestock as their tool to transform the degraded cropland into productive pastures.

When Nick and Annie met, neither of them had much farming experience. He grew up participating in rodeos and later served in the U.S. Army, and she had a background in business and sold real estate. Even so, the couple envisioned having a small herd of beef cattle and growing alfalfa, so they jumped at the chance to purchase their property when it went up for sale.

The farm was previously used to grow

corn and soybeans, but it had become unkempt over time. The Rodgerses found piles of trash, pieces of scrap metal, and the occasional vehicle battery hiding among the weeds, not to mention a heap of tires buried under a thicket of grape vines. They spent the first few months on the property picking up debris and eventually prepared the seedbed to plant alfalfa in the spring of 2019. Their dream of harvesting high-quality hay was almost a reality until they encountered some unruly rain.

“After we drilled the alfalfa — and just as it was starting to come up — we got 4 1/2 inches of rain in less than 18 hours,” Annie shook her head, still in

disbelief. “Everything floated away or died. We were just like, ‘What are we going to do now?’”

The answer came to them while they were watching a documentary about regenerative agriculture. “That started us down a rabbit hole of looking into grazing rather than making hay, which we didn’t have any more money to put toward inputs for anyway,” Annie said.

What started out as an economic decision evolved into an environmental one as the couple shifted their mindset to adaptive grazing and holistic management. They attended pasture walks, enrolled in grazing schools, and continued to watch videos and listen to podcasts about regenerative agriculture to pinpoint the practices they wanted to pursue.

Today, Red Leg Farms encompasses roughly 130 acres of owned and rented land, including several pastures in various stages of renovation. The Rodgerses have established a robust mix of grasses and legumes in their fields for their sheep and cattle, and their colorful cowherd is just as diverse as their forage base. They strive to share their story with others by hosting pasture walks of their own, and they sell beef and lamb direct-to-consumer, giving customers an inside look at how food gets from farm to table.

The Rodgerses admit their first attempt at grazing livestock was somewhat of a failure. After their alfalfa seedlings washed away, Nick broadcast seeded orchardgrass and perennial ryegrass in the field. He also planted some cover crops to protect patches of bare soil.

The couple experimented with bale grazing that winter. They made temporary paddocks by driving T-posts into the ground and adorning them with aluminum wire — a tedious routine they engaged in nearly every day. Then they set out large square bales and scattered hay by hand. “I felt like a flower girl at a wedding,” Annie laughed from under a wide-brimmed hat. “If you looked at the field from above, it probably looked like a checkerboard with flakes of forage spread around.”

To alleviate some of this manual labor, the Rodgerses bought step-in posts and polywire to make creating temporary paddocks less of a chore. They also invested in equipment to move and unroll large round bales.

Nick buys late-maturity, first-cutting hay from to ensure reseeding from bale grazing is successful, and he works with several sellers so not all of his hay comes from the same farm. Results from a long-term monitoring study with the Noble Research Institute and Michigan State University show one of the pastures at Red Leg Farms contains 17 different forage species.

“I want to get as many different species of plants out there as I can possibly get,” Nick said. “We have some clover, teff grass, bromegrass, orchardgrass, Kentucky bluegrass — the list is a mile long. It has all been replanted with hay.”

Livestock begin to strip graze pastures in the spring, starting with the 70-acre area at the Rodgerses’ home farm. Then Nick and Annie parade the

animals across the road to a 22-acre field in the early stages of renovation that they lease from a neighbor before rotating the sheep and cattle through three other rented pastures that are all within a few miles.

Nick allots livestock new forage every day, but he monitors plant growth to determine how far to move the polywire forward. He also assesses pasture conditions to pace grazing rotations. One rotation takes 30 to 35 days at the start of the season when grass growth is rapid, whereas the same rotation will last about 90 days in the summer to prevent cattle from overgrazing when it is hot and dry.

Access to mineral supplements is key to balance forage consumption, and Nick strategically situates mineral tubs in pastures to influence grazing behavior. For example, placing a tub on the side of the field opposite from the waterer encourages more grazing traffic throughout the field and results in a better distribution of manure.

The couple currently moves a portable water cart for their livestock from pasture to pasture, refilling it every three days. They plan on installing a permanent water system using a pressurized underground waterline someday.

Red Leg Farms is home to several cattle breeds, including Scottish Highland, South Poll, Hereford, and British White Park. A flock of hair sheep also graze alongside the cattle, serving as the clean-up crew for less desirable forage species. The Rodgerses aim to maintain a stocking density of 35 animal units, which equates to approximately 25 cattle plus 20 to 30 sheep.

Despite the eclectic group of grazing animals, Nick and Annie built their brand on the backs of their Scottish Highland cattle. The distinctive features of this breed — long, wavy hair and a broad set of horns — are depicted in their business logo, which they believe stands out to customers and generates greater interest in their meat sales.

One consequence of the charming characteristics of Scottish Highland cattle is that their horns are too wide to fit in some processing facilities. This made it more difficult to find locker space, so the Rodgerses resolved to introduce different breeds to their herd to keep up with demand. They also

started breeding their Scottish Highland cows to South Poll bulls since some of the offspring do not have horns.

Red Leg Farms sell cuts of lamb and freezer beef in halves and wholes. Sheep and cattle are 100% grass-fed and grass-finished, and the Rodgerses advertise that they do not administer preventative treatment to their livestock. They believe these attributes attract a niche market of health-conscious consumers who are willing to pay higher prices for their products.

“Our customers choose to buy from us even though it might be more expensive because they know our animals were raised with lower inputs,” Annie asserted. “If an animal gets sick, we will treat it, but then it will be marketed differently.”

In addition to communicating what’s in their products, Nick and Annie like to show customers what’s on their farm. When people come to pick up orders, the couple invite them on a walking tour of the property to explain the forage system, the grazing rotation, and the positive effects their management has on their animals and their land.

“For as much as we want people to be educated about how we graze livestock, I also want people to know where their food comes from. That has really made the difference for me,” Annie said.

The goal of regenerative agriculture is to rehabilitate farming systems by engaging in practices that improve soil health, encourage biodiversity, and benefit the environment overall. Little did Nick know before he and Annie established Red Leg Farms that repairing pastures and caring for livestock would be a form of recovery for himself, too.

Nick was medically retired from the Army after serving in combat and being diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. When he and Annie set out to start farming, he thought raising cattle in a feedlot and making hay would be a good way to get back on his feet. Rather, he found a greater purpose in life by looking through a more regenerative lens.

“Taking care of the animals, watching the ground, and improving my grasses, forage quality, and plant diversity has really been good for my mental health and well-being,” Nick said, reflecting on the positive change.

The couple have an overwhelming sense of gratitude for farming that they want others to experience as well. Although renovating their own pastures is an ongoing endeavor, they are training to become associate educators with the Savory Institute. The organization’s mission is to regenerate the world’s grasslands through holistic management, and after realizing the advantages of this approach for themselves, the couple want to support beginning graziers who are doing the same.

“One of the things that we have made a priority is teaching others about why or how to think differently about their own operations,” Annie said. “Finishing our training and becoming educators will hopefully help us do that.”

On the next episode of “Extreme Makeover: Pasture Edition,” you might find the Rodgerses somewhere other than Montrose. They are open to the idea of raising livestock in a more brittle environment one day to expand their expertise in adaptive grazing. Whether that be on arid rangeland out West or in a completely different country, Nick and Annie are eager to apply their newfound knowledge wherever they can. •

The Rodgerses constantly seek opportunities to become better graziers and share their knowledge with others.

Forage growers across the country are invited to participate in the 2023 World Forage Analysis Superbowl. Awardwinning samples will be displayed during Trade Show hours in the Trade Center at World Dairy Expo in Madison, Wisconsin, October 3 - 6. Winners will be announced during the Brevant seeds Forage Superbowl Luncheon on Wednesday, October 4.

Contest rules and entry forms are available at foragesuperbowl.org, by calling Dairyland Laboratories at (920) 336-4521 or by contacting the sponsors listed below.

Learn more about the six Dairy Forage Seminars hosted at WDE, Wednesday - Friday, by visiting the WFAS website.

$26,000+ in cash prizes made possible by these generous sponsors:

Entries Due Harvest Year Category

August 242023

August 242023

August 242023

August 242023

August 242023

Crop/plant/sample specifications

Dairy Hay >75% legume; grown by active dairy producers

Commercial Hay >75% legume; commercially grown and sold in large lots off the farm

Grass Hay >75% grass

All hay samples: Must be from a bale, any type or size; use of a preservative or desiccant is allowed.

Baleage Any mixture of grass/legumes Baleage: Must be processed and wrapped as baleage and show signs of fermentation.

Alfalfa Haylage ≥75% legume

August 242023

Mix/Grass Hlg <75% legume

All silage samples: Must be ensiled in a normal preservation process and show signs of fermentation. Use of a preservative is allowed. Additives affecting fiber content or any other adulteration will disqualify the sample.

Samples analyzed for (expressed on a dry matter basis):

Hay, Baleage, Haylage: Dry matter, crude protein, acid detergent fiber (ADF), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), neutral detergent fiber digestibility (NDFD), relative forage quality (RFQ) and milk per ton.

[RFQ is a ranking of forage quality based on NDFD and should not be confused with or compared to Relative Feed Value (RFV).]

SUMMER seems to pass by faster and faster each year. For the most part, it’s because I work too much and can never seem to slow down. I think we all have a certain time of year that seems to go by at a faster rate and another that drags on and on. During the busy season, or the ones that fly by, it’s especially hard to take time to plan ahead. So, to make sure you don’t fall too far behind, you have to plan even further ahead during the “slower” months.

How does this relate to equipment?

Some aspects of the equipment business have returned to pre-COVID levels while others still remain with a backlog. Most smaller tractors — under 100 horsepower (hp) — are beginning to show up on time with regularity. Thus, this segment on the used equipment side will start to regain some strength in numbers and will eventually start to bring down the used equipment values due to a plentiful supply.

If you are looking for a used raking tractor this year, you can be patient and continue to monitor the market to find one that’s reasonably priced. This is something we haven’t been able to say for a few years.

The 100 to 200 hp tractor group is in better shape in terms of inventory level than it was a year ago, although not by much. Some of the lower horsepower units are becoming more plentiful, but for the most part, you can expect a lead time

of eight or more months for this category. With the new equipment being slow to come in, the used equipment hasn’t seen much change in value or availability.