7 minute read

Jesse Thomas and the Art Politique

A visual exploration of who is represented and who has the right to represent them

WORDS BY JOE GURBA

We live in a political time. Like never before, every facet of life has been politicised, or rather discovered in the political dimension it always occupied, depending on your view. Aesthetics is certainly no exception, its political charge stronger than ever as people outside of the formal arts’ community also begin to haggle over the role of visual representation. Nowhere is this laid more bare than in the question of public art, mostly so in the campaign to remove existing public art like the confederate statuary of the American South. Enter Jesse Thomas.

Jesse Thomas has lived and exhibited around the world and now teaches painting at the University of Alberta. Nevertheless, he still considers his native New Orleans home. He’s explored numerous topics in his paintings since graduating with a BFA from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1993 and an MFA from Washington University in Saint Louis in 2003, not least the intersection of the arts and power. In 2017, he completed a series of lithographs that sought to digest the inner turmoil of seeing landmarks and artifacts of his home removed and the outer turmoil of his nation grappling with the ongoing realities of racism. These were the four statues of Confederate Army generals that led forces to protect the Southern states’ right to own human beings.

As painful as it was to see landmarks removed that had become woven into the tapestry of the NOLA’s beautiful visual identity, Thomas recognized that the history they represent has not receded into an apolitical haze for everyone. As so many of NOLA’s 60% African-American residents made clear, the oppression these men fought to uphold remains a present and living reality But in so recognizing, the infinitely receding question of the line between representation and power opens to an abyss of questions about the role of the artist, especially the historical painter, and whether such an artist can still exist. And if so, who?

In the first three pieces, the familiar statues hang dream-like in the left of the visual plane, thereby drawing the eye to read the painting left to right like a poetic text. They seem to dangle aloof from an off-canvas crane, twirling precariously in all their implied heft. All five works swirl with visual references to so many instances of tension in representation, the teeth-baring battles, and in the quieter, glacial manufacture of imagery. ▶

The Politics of Representation begins with the labyrinthine bewilderment of deconstruction. The Jefferson Davis monument (the first and only president of the Confederate States during the Civil War) points left, as if to the past. Behind him is the recurring image of Donald Judd’s, ‘Untitled, 1967’, slotted wall from the MOMA, a famous example of pure formalism, almost trolling the viewer with the question of whether there’s any quarter for artists or can even the most rawly geometric exercise stand up to the question of power in representation. As in all three, this wall is a door to nowhere, but in the first lithograph a familiar silhouette looms, that of then-recently inaugurated Donald Trump, maneuvering to seize on the fear and anxiety that emerges from such all-encompassing deconstruction.

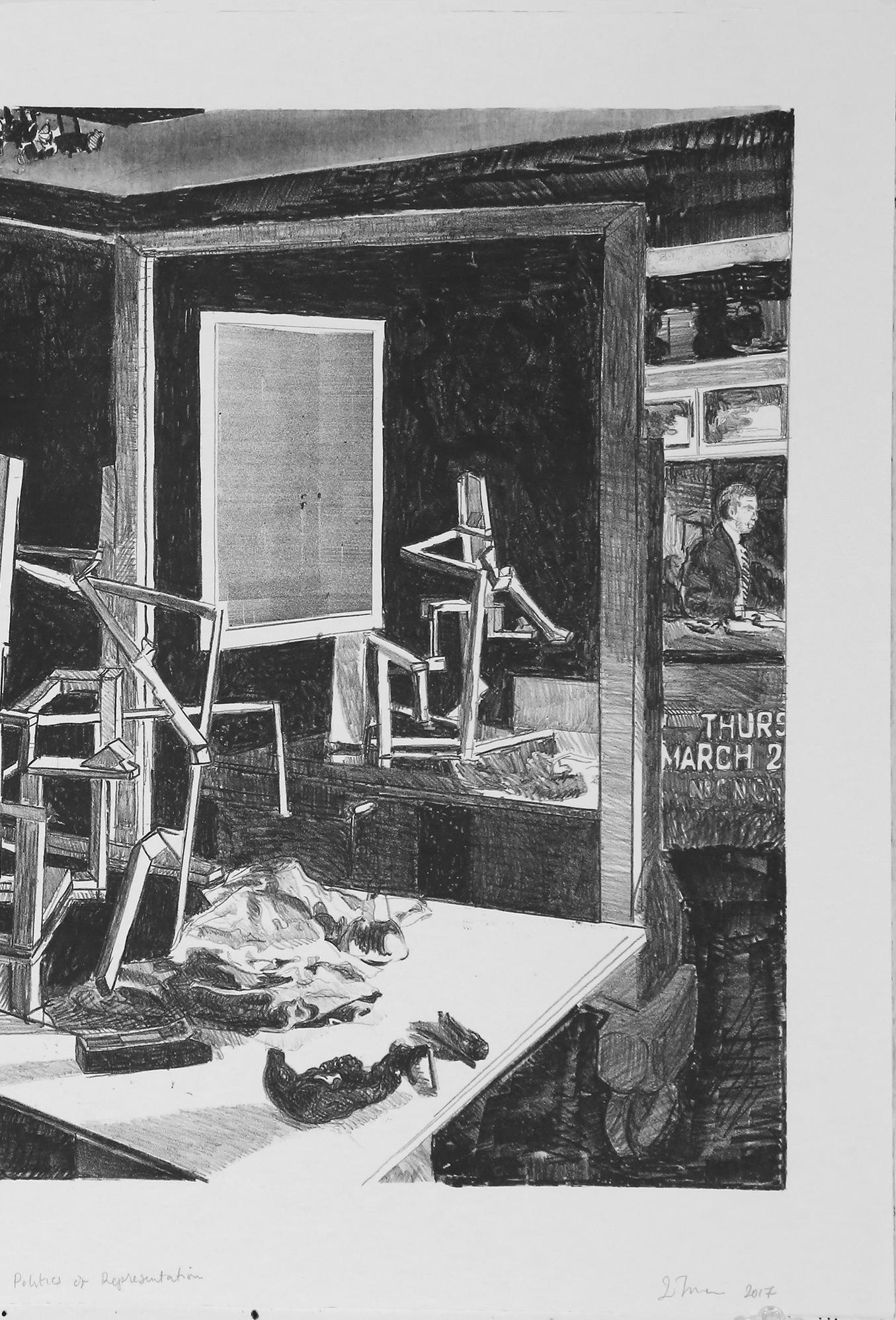

On the stage sits a chaos of tacked together pieces and discarded rags confusingly mirrored every which way, refusing to yield to the straightforward comforts of interpretation. Where once a monument stood taken for

granted, rarely considered in it’s full context, a chasm has suddenly opened in the floor of certainty. From every station of society, people scramble to respond. And on the far right begins a recurring image of the news anchor, trying to make sense of it all, trying to maintain an ever-deteriorating pretense to objectivity. ▶

The Politics of Representation

Next, The Politics of Aesthetics lithograph carries us further into the fray. The infamous image of Paul Ryan weightlifting in TIME Magazine occupies center stage, taking on a profound new meaning. We can read in this an assertion of meaning from the political right. Their clumsy reassertion of meaning offers reprieve from the nausea of guilt and moral uncertainty. Ironically, this serves only to advance the power of the unscrupulous who would capitalize on this anxiety, a justification for a memorialized one-sided history. The irony lies in that these justifications are facsimiles of those originally offered by the Confederate States as NOLA’s Confederate General PG Beauregard dangles to the left.

In the foreground, a defiant philosopher stares directly at the viewer, Jacques Ranciere, who penned the essay, The Politics of Aesthetics, instrumental in the deconstructive turn in art

criticism that created this new battleground for meaning. We’re taunted further by two easter egg paintings behind Paul Ryan. On the left, Gerhard Richter’s photo-realism painting ‘Dead’, showing a West German communist insurrectionist from

the Baader-Meinhof Gang. Her death in prison was heavily contested. Did she commit suicide as the official line went? Or had she been surreptitiously murdered by the state? The painting

The Politics of Aesthetics re-established a defensible form of art historical

painting that had evaded the 20th century critiques of art’s place in capturing history. By depicting a photograph from the newspaper, Richter problematized the line between art being disallowed from representing history while the media’s role in representing history could go on unchecked. No longer is this the case.

On the right hangs Dana Schutz’s painting ‘Open Casket’, a photo-based depiction of Emmett Till, just as Richter had done in ‘Dead’. The story of Emmett Till is painful to recount and I hope is already familiar to the reader. This fourteen year old boy who was black was brutally murdered by two men who were white. His mother, Mamie Till’s, insistence that her son’s funeral be held

open-casket resulted in widespread circulation of the close-up photos in the media, shocking America into a moral consciousness that laid the

foundations for the civil rights movement. Dana Schutz’s painting in 2016 was an attempt at allyship, but as a white woman, the painting was ultimately censored in a firestorm of debate in the shifting landscape of identity politique, further fracturing the place of the artist to represent the political. She could not stand on the same ground Richter had in ‘Dead’, despite her best intentions. Together these symbols awake a host of difficult questions. ▶

Finally, we witness Vehicles of Understanding, together with General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate forces, who surveys the wreckage as if taking final account of the battlefield, aborted works of art littering the stage, a luminous TV blathering in the center, a fractured depiction of a monumental sculpture, and a distant news anchor with their back turned to it all. ▶

Vehicles of Understanding

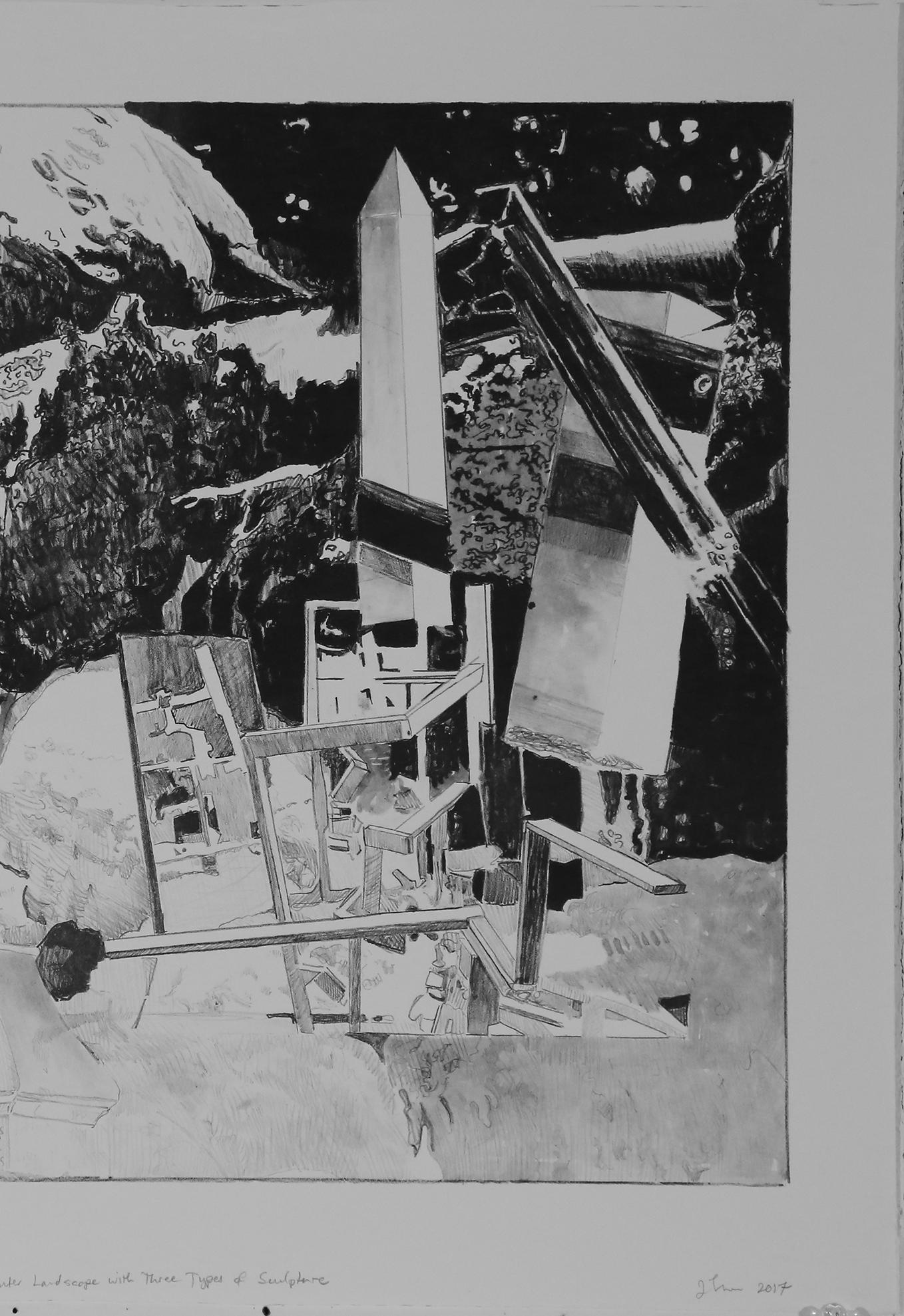

With the conceptual groundwork established in these first three lithographs; the final two, Winter Landscape and Horse’s Mouth can offer the viewer several endless explorations that I think it best not to narrate here. Instead, I leave them to you, the viewer, to ponder and interpret as you see fit, and encourage fortitude resisted knee jerk conclusions but rather to dwell boldly in the grey space that a lithograph creates by its very nature. ▶

Winter Landscape

These lithographs linger so uncomfortably over these perilous questions of who has the right to represent anything. They push back against ever more radical propositions that some artists need not be in the

conversation at all. From a litany of symbols and references, these works create a matrix of emergent meaning from which the viewer can draw forth their own questions. Perhaps these are questions that have not occurred to them. Perhaps questions that feel dangerous to ask. Perhaps questions that need to be asked. www.scottgallery.com/artists/jesse-thomas

Horse’s Mouth