Lucy Kim (born 1978, Seoul, South Korea; based in Cambridge, Massachusetts) is an interdisciplinary artist whose work embraces distortion as a tool to deconstruct how we see what we see. Mutant Optics is an exhibition of new works on paper that explore relationships between visual appearance, bioengineering, and the social and cultural construction of race and perception.

This work is the result of an experimental printing process in which Kim uses genetically modified bacteria cells that produce melanin directly on paper. The melanin Kim uses is the same black and brown pigment that plays a key role in the color of human skin, hair, and eyes. By using melanin and displacing it from the important biological and health functions of the body, Kim questions the ways in which the meaning and material of human appearance are subject to mutation in the social imagination, including the false myth of racial hierarchies.

The prints in the exhibition depict images of vanilla beans, flowers, and plants. Although the vernacular use of the word “vanilla” today often connotes banality and whiteness, the mass-market production and distribution of this spice are entangled with legacies of slavery and colonial extraction. Kim’s melanin prints confront these overlooked racial histories. One image depicts a lab-grown vanilla plantlet that scientists genetically modified to be albino, a process that visually reveals the success of experiments on other genes. The effect evokes whiteness as an engineered condition and the concept of nature as a product of human invention.

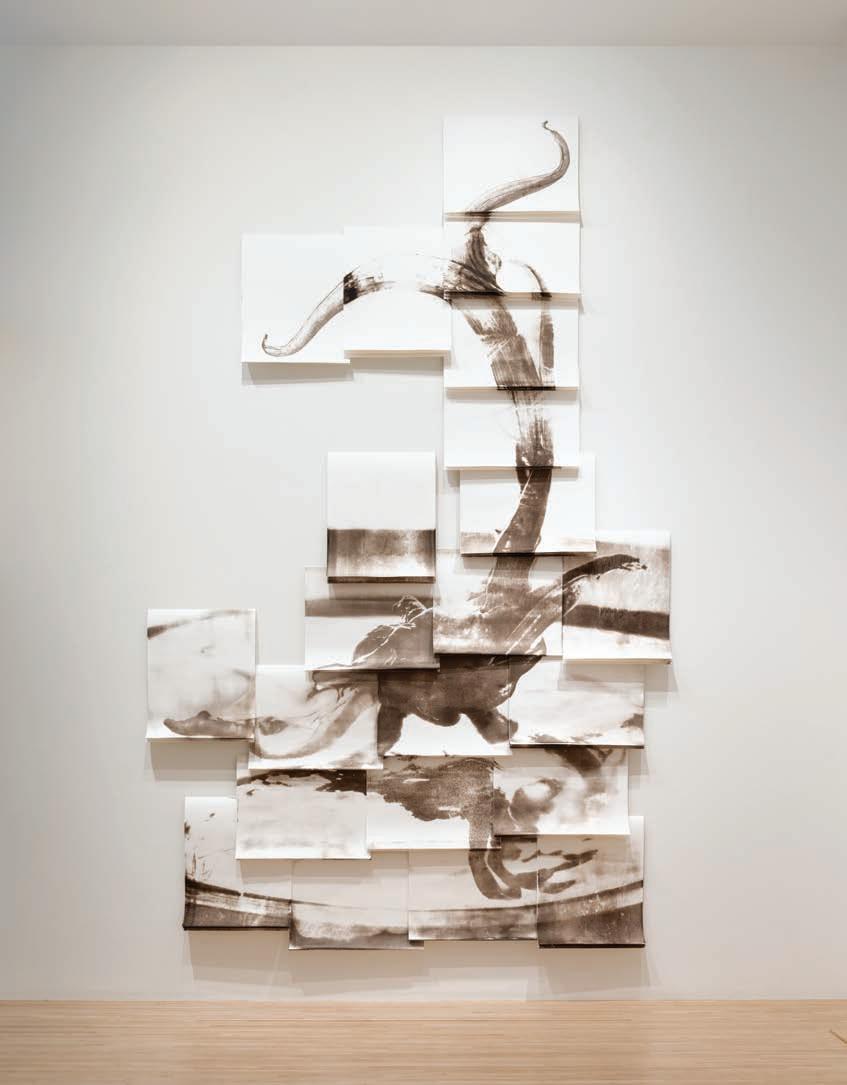

Kim created the sculptural installation of her prints in response to the double height of the Henry gallery, using scale and repetition to create glitches in recognition and legibility. Multiple prints of the same image vary in saturation and show the unpredictable outcome of a process using live cells, shifting the basis of sight from something predetermined to a contingent condition. With allusions to botanical illustration and related practices of biological classification to present-day scientific invention, Kim’s installation questions the neutrality of visual culture and knowledge production that mold the way we see and make meaning of others and ourselves.

— Nina Bozicnik, senior curator

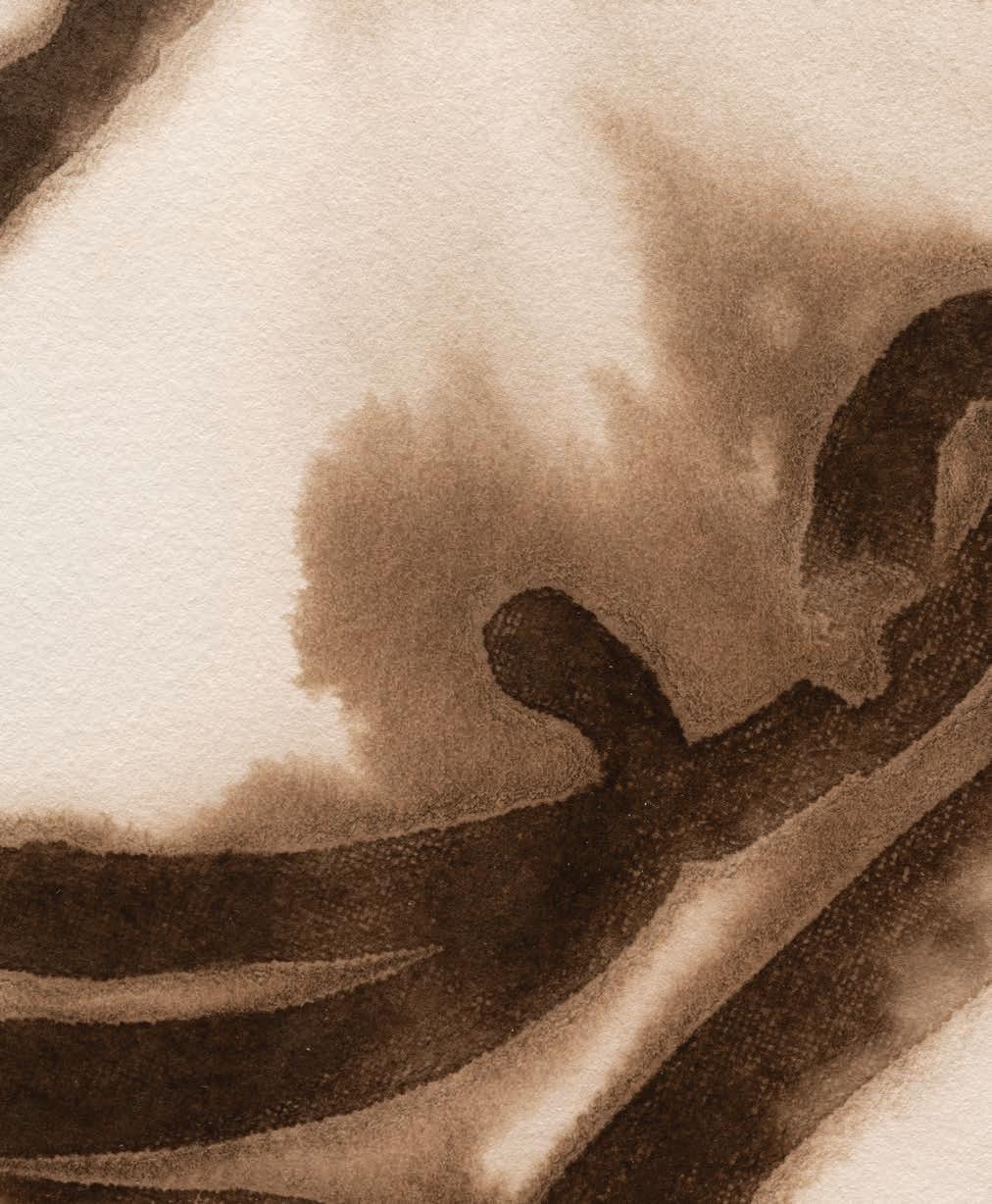

Cover and inside cover: Lucy Kim, Two Species, Three Patterns (Dried Vanilla Pods: V. Planifolia and V. Pompona) [detail]. 2024. Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, aluminum hardware.

Opposite: Lucy Kim: Mutant Optics [installation view].

This project originated in 2015 when I was looking into making paint with melanin, the main pigment behind human skin, hair and eye color, and a signifier of race. I was specifically interested in eumelanin, the black/brown and most prevalent form of melanin, only to discover that it cost almost $400/gram in powdered form (it is now about $570/gram). I put the project on hold until 2018, when I was able to resume with funding and lab resources as an artist-in-residence at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. There, I learned that E. coli cells could be genetically modified to produce eumelanin. I began experimenting with a strain created by Dr. Guillermo Gosset and his research team at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, which he kindly shared with me. I initially sought to extract the melanin produced by the bacteria and simply print images with it, but I soon realized that there was something powerful about an image being produced through a living organism, showing signs of the imperfections and distortions inherent in living processes.

Over the course of several years, I developed a process for screen-printing live E. coli cells on paper so that the cells make melanin onto it over three days. When the live bacteria is printed onto paper, the microscopic cells respond to minute differences in moisture level, chemical composition, and texture across the paper’s surface. There is also evolutionary drift of the cells as they rapidly multiply, and this changes how much melanin each cell produces. Add in the inconsistencies of the human hand to this microscopic biological process, and the result is a unique print, even through a mechanical process like screen-printing.

The image is fixed when the cells are killed with ethanol and heat, so no live cells are present on these prints once they leave the lab. This also keeps the project in line with safety regulations. Despite its bad reputation, most E. coli strains are not dangerous, and in fact, some live in our bodies. The strains that I use for this project are genetically modified versions of commercial strains developed and sold for scientific research, and are safe to use in a BSL-1 lab (Biosafety Level 1). Out of the four biosafety levels, this is the lowest.

— Lucy Kim

Previous: Curing Vanilla (V. Planifolia Pods Drying) [detail]. 2024. Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets.

This spread: Two Species, Three Patterns (Dried Vanilla Pods: V. Planifolia and V. Pompona) [detail]. 2024. Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, aluminum hardware.

This spread: Two Species, Three Patterns (Dried Vanilla Pods: V. Planifolia and V. Pompona). 2024. Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, aluminum hardware.

Next page: White Vanilla (Gene Edited Albino Vanilla Plantlet) – 22 Part Composition. 2024. Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets.

By Jennifer Y. Chuong

It takes time to discern the full strangeness of Lucy Kim’s recent prints. Upon first encounter I was struck by the works’ grand scale, the curl and flip of overlapping sheets. Only upon closer examination did the smoky, somewhat uneven sepia printing—reminiscent of old and battered photographs—reveal its odd textures and markings. Surfaces shift in and out of familiarity: supple skin into rain-washed stone, creased vanilla bean pod into abstract stroke, glossy leaf into crawling pottery glaze into mesh window screen.

Much of the strangeness of Mutant Optics’ prints is borne out of the fact that they are made with a living ink. Rather than mixing a relatively inert pigment into a binder, Kim suspends genetically modified bacteria (specifically, a harmless strain of Escherichia coli, more commonly known as E. coli) in a growth medium she formulated for this purpose. Pressed through a silkscreen matrix, this “ink” deposits billions of bacteria across the surface of the paper where, over the course of three days, a hundred generations will grow, reproduce, and die, generating melanin as a stress response to the depletion of their initial sugar supply. The resulting images are thus shaped by the matrix but not wholly determined by it. Quirks of distribution and growth contribute their own layer of interpretation, altering the textures and forms of the original images. Ultimately, the prints are washed to clear away the dead E. coli cells, leaving the melanin as a trace of their brief lives.

There is perhaps no medium more charged than melanin, a biological pigment most well-known for its significant role in determining human skin color and its consequent contribution to the history of racialization and racial discrimination. As Kim puts it: “It’s hard to know that an image is made with melanin and not think of humans (and human appearance) and specifically race.”1 However, as I learned from the artist, melanin in its various forms is found in many organisms—mammals, birds, fish, insects, fungi, bacteria, and some plants—and it has many functions. Most commonly providing physical protection against a variety of stressors and threats, melanin can also contribute to species coloration (and therefore camouflage), surface durability, and thermoregulation.2

1. Pam DeBarros, “CFA Professor Lucy Kim Creates Images Using Genetically Modified E. coli That Produce Melanin,” October 8, 2023, YouTube video, 3:41, https://youtu.be/McWjtVcl238.

In meeting shared needs, melanin compresses the perceived vastness between organisms. Both humans and bacteria, it turns out, need protection from UV radiation. For all that melanin has been used to reify differences between human beings, then, it also offers proof of our commonality with a wide range of life-forms.

In this regard, it is significant that the primary subjects of Mutant Optics are not humans, but plants: specifically, vanilla orchids being cultivated at a research station in Florida for the purposes of developing a variety that can easily be grown in the United States. Tagged as research subjects, the plant material depicted in these images is both of nature and alien to it: one of several binaries (plant/human, organic/mechanical, control/chance, etc.) in and against which Mutant Optics works.

One lens through which we can understand both these binaries and their destabilization is that of the plantation. Organized around the large-scale, profit-oriented cultivation of a single crop, plantations have flattened the world by extracting species, transporting them great distances, and cultivating them in foreign environments. Among these displaced species are humans, both those who have moved by choice (the “owners”) and those who have been compelled to move through enslavement, indenture, and other forms of coercion. Forced labor, and the resulting race-based social system, made (and continues to make) plantations possible; and it is the ongoing dominance of plantation systems that has given rise to the Plantationocene as a proposed name for our epoch.3

2. Luz María Martínez, Alfredo Martinez, and Guillermo Gosset, “Production of Melanins with Recombinant Microorganisms,” Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 7 (2019), 2-3.

3. The term was first proposed by Donna Haraway in a 2014 conversation regarding the “still inchoate concept of Anthropocene.” Donna Haraway et al., “Anthropologists Are Talking—About the Anthropocene,” Ethnos 81, no. 3 (2016), 556. Subsequently, scholars have critiqued early formulations of the Plantationocene for underemphasizing the centrality of enslaved labor and racial politics in sustaining plantations. For a summary and extension of this critique, see Jane Davis, Alex A. Moulton, Levi Van Sant, and Brian Williams, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, ... Plantationocene?: A Manifesto for Ecological Justice in an Age of Global Crises,” Geography Compass 13, no. 5 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12438.

Though other forms of agricultural cultivation also contribute to social hierarchies and are attended by varying degrees of violence, anthropologist Anna Tsing argues that plantations are unique in that they “remove the love.”4 That is to say, because plantations rely upon forced labor, they must exert an unprecedented degree of control over both their crops and the humans that cultivate them; and in doing so, they suppress any sense of affection or affinity that might develop between people and their plants. By using melanin to print pictures of vanilla, Kim underscores both the fundamental relationship between plantations and race that undergirds the Plantationocene and the multispecies relationships that thread through it.

The scientific development of the species Kim has chosen to foreground in Mutant Optics also highlights the relationship between control and plantation order. In its careful cultivation of a gene-modified bacteria, Mutant Optics’ boutique process of printing with melanin partakes of the same plantation logic that undergirds the commercial cultivation of the vanilla orchid. The motivation behind the modification of E. coli to produce melanin was (of course) not aesthetic, but commercial: melanin is a “highvalue” compound that has potential industrial and medical uses.5 And like the cultivation of vanilla, this method of producing melanin requires forceful means. As mentioned above, melanin production is a starvation response on the part of the genetically modified bacteria. The modification itself involves a foreign gene being “shoved” into each microorganism. Because the gene also provides resistance to an antibiotic in the growth medium, the E. coli must retain it in order to survive.6 More generally, as with any process

4. Anna Tsing, “Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species,” Environmental Humanities 1, no. 1 (2012), 148.

5. V.H. Lagunas-Muñoz, N. Cabrera-Valladares, F. Bolívar, G. Gosset and A. Martínez, “Optimum Melanin Production Using Recombinant Escherichia coli,” Journal of Applied Microbiology 101, no. 5 (2006), 1002.

6. Lucy Kim, conversation with author, 30 April 2024. The antibiotic is not always successful. As cells grow on top of one another, the uppermost layer can sometimes escape contact with the medium, allowing those bacteria to kick out the foreign, melanin-producing gene without negative repercussion. It is events like these that contribute to the prints’ irregularities.

involving the culture of a specific microorganism, control is key. The preparation of the living ink must be conducted with sterilized equipment and gloved hands, and the concentration and cleanliness of each batch of ink has to be carefully monitored: dilution or contamination of the solution is likely to result in an illegible image. Once the ink has been screened onto the paper, the prints are placed in an incubator, which provides the warm, stable environment that the E. coli needs to flourish. Over the past several years, Kim has worked assiduously to develop a process and environment that will produce as much as melanin as possible.

At the same time that it references and even partakes of plantation logic, Mutant Optics undermines it. If printmaking is often understood as a medium of reproduction, these works are emphatically the product of chance and variation. Large, unmarked areas, like the dark surround of Hands Pollinating Vanilla Flowers (Edmond Albius Method), give the bacteria free reign to reproduce as they will (allowing for differences in ink application, which Kim deliberately introduces) (pp. 17-18), but their agency is also manifest in the demarcated portions of the images, where the replication of the bacteria sometimes does and sometimes does not result in the expected image.

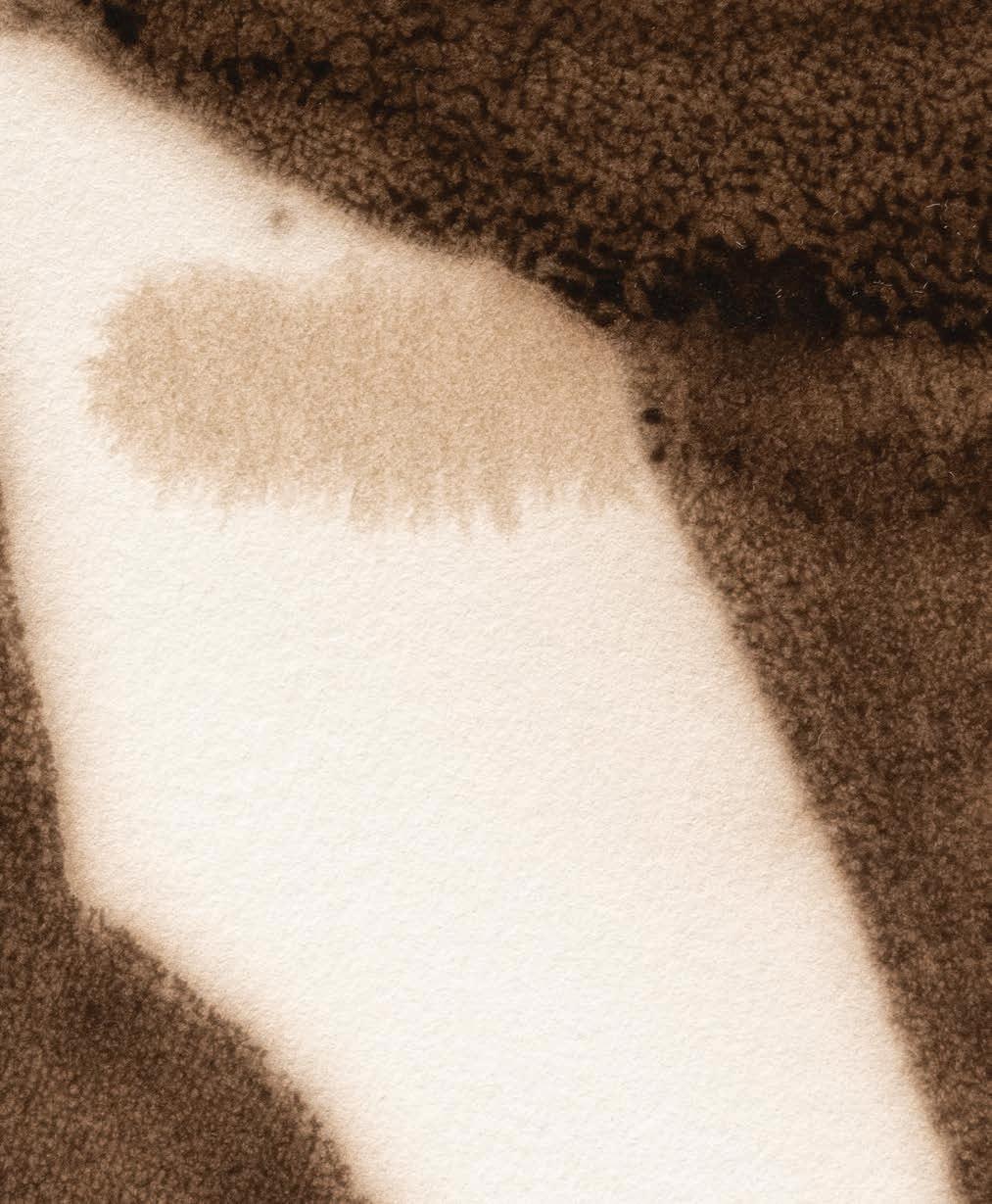

Mutant Optics is thus an expression of both Kim’s agency and that of the genetically modified E. coli. Moreover, the intimate process of working with these microorganisms has led the artist to a richer understanding of their actions as not merely resistance or waywardness, but also expressions of inclination and even emotion. As Kim observed in a striking formulation: “it loves anything with flowers in it.”7 This affection is evident in the bacteria’s rendering of crinkled petals and the delicate, creeping line of the flower’s edge in Hands Pollinating Vanilla Flowers (Edmond Albius Method) (p. 19). Conversely, it plays badly with mechanical patterns, like the perforated drying screen of Curing Vanilla (V. Planifolia Pods Drying). Rather than reproducing the holes with the consistently dark tone of the original photograph (pp. 5, 22), the E. coli persistently render them in uneven midtones, with areas of light that introduce a sense of glare or optical distortion. As a result, the bacteria transform the source image into something more dynamic

7. Ibid.

and organic—something, perhaps, more like a flower. And while one might seek to draw a line between these regions of order and disorder, mechanicity and organicity, the works refuse it. In a representative instance of Tagged Vanilla Pods, large, gridded holes merge into small, irregular bubbles (p. 21). Though the two areas look distinct, it’s impossible to draw a line between them, as the intermediary holes look both like diminutions of the mechanical pattern and enlargements of the organic arrangement.

Beyond the variation that attends any interaction with an independent and therefore unpredictable agent, Kim has refrained from trying to perfect her process. Self-identifying as a “bad scientist,” the artist is committed to riding a thin line in which control and chance are, ultimately, inseparable. In doing so, she has pried open a space where she, and by extension we, can cultivate a relationship—of curiosity, of interest, even, perhaps, of affection—with the multiple species, both known and unknown, who are involved in the making of her work. Ultimately, Mutant Optics asks what it might mean for us to recover love in the plantation—or better yet, how love might help us work towards means beyond it.

Jennifer Y. Chuong is assistant professor of art history at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Her research centers on the art and material culture of the eighteenth-century British transatlantic world, particularly its intersection with histories of race and environment.

Previous: Hands Pollinating Vanilla Flowers (Edmond Albius Method). 2024. Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets.

Opposite and below: Hands Pollinating Vanilla Flowers (Edmond Albius Method) [detail]. 2024.

Tagged Vanilla Pods. 2024. Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets.

Opposite: Tagged Vanilla Pods [detail]. 2024.

Curing Vanilla (V. Planifolia Pods Drying). 2024. Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets.

White Vanilla (Gene Edited Albino Vanilla Plantlet) –22 Part Composition, 2024

Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets

246 x 156 in. (624.8 x 396.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist

Hands Pollinating Vanilla Flowers (Edmond Albius Method), 2024

Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets

163 1/5 x 124 4/5 in. (414.5 x 317 cm)

Courtesy of the artist

Two Species, Three Patterns (Dried Vanilla Pods: V. Planifolia and V. Pompona), 2024

Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, aluminum hardware

71 x 348 in. (180.3 x 883.9 cm)

Courtesy of the artist

Curing Vanilla (V. Planifolia Pods Drying), 2024

Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets

66 x 28 in. (167.6 x 71.1 cm)

Courtesy of the artist

Tagged Vanilla Pods, 2024

Melanin produced by genetically modified E. coli cells on paper, powder-coated aluminum brackets

61 1/2 x 79 in. (156.2 x 200.7 cm)

Courtesy of the artist

Lucy Kim is based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is a recipient of a 2024 Howard Foundation Fellowship in the Emerging Arts and a 2022 Creative Capital Award for her project printing images with bacteria that has been genetically modified to produce melanin. Kim is also a recipient of the Brother Thomas Fellowship, Mass Cultural Council Grant, ICA Boston James and Audrey Foster Prize, Artadia Award, MacDowell Fellowship, and Hermitage Fellowship. From 2018 to 2021, she was an artist-in-residence at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and she is the Fall 2024 Leslie and Brad Bucher Artistin-Residence at the Moody Center for the Arts at Rice University. Kim has exhibited her work at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Institute of Fine Arts at New York University; deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, Massachusetts; Tufts University Art Gallery, Medford, Massachusetts; Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore, Sarasota Springs, New York; Brooklyn Academy of Music; among others. She is an associate professor of art at Boston University, where she works with students and scientist colleagues to further develop her experimental process using melanin.

Lucy Kim would like to acknowledge the people and institutions whose generous support have made this project possible:

Boston University Biology Department

Boston University School of Visual Arts

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Artist-in-Residence Program

Creative Capital

Brother Thomas Fellowship

Dr. Guillermo Gosset and his research team (UNAM, Mexico)

Dr. Chip Celenza (Boston University Biology Department)

Dr. Sam Myers (formerly at the Broad Institute, now at the La Jolla Institute, CA)

Maria Brym (formerly at the University of Florida, now at the USDA)

Dr. Xingbo Wu (University of Florida, Tropical Research and Education Center)

Abby Fenn (former student, now the artist’s studio manager)

All the incredible Boston University students who have been involved in this project: Xian Boles, Mason Burns, Abby Fenn, Brianna Howard, Allison Huang, Eli Ibarra, Rylee Malone, Jaylynn McCurdy, Sanjana Prudhvi, Bridgette Reilly, Allison Suarez, and Xingpei Zhang

Emeka Alams

Maisea Bailey

Erin Baldner

Tanja Baumann

Erika Bentley

Holland

Emily Blanche

Sarah Borders

Nina Bozicnik

Margarita BurnettThomas

Paula Castillo

Em Chan

Harold Churchill III

Troy Coalman

Madeleine Craig

Jeff Deveaux

Orlando Francisco

Trevor Goosen

Garrett Keese

Danielle Khleang

Claire Kenny

Laura Kinney

Salah Kornas

Catalina Lane

Kris Lewis

Summer Li

Emma Rowley

Markie Mickelson

Stephanie Mohr

Shamim M. Momin

Silas Morrow

John Mullen

Alicia Murillo

Grant Pattison

David Smith

Sage Sommer

Phil Steyh

Stephanie Sun

Corinne Wheeler

Vivian Wick

Eric Zimmerman

TEXT

Nina Bozicnik

Jennifer Y. Chuong

Lucy Kim

DESIGN

Emeka Alams

Summer Li

PHOTOGRAPHY

Jueqian Fang

Lucy Kim: Mutant Optics is organized by Nina Bozicnik, senior curator, with Em Chan, curatorial assistant. Generous support is provided by the Imaginative Project Award and a grant from the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation. New work by Kim is funded with support from Creative Capital.

All Henry exhibitions are the collective work of staff across museum departments.

© 2024 Henry Art Gallery henryart.org