Thick as Mud

Cover Image: Sasha Wortzel, Sitting

Shiva [detail], 2020 Burmese Python skin, vegetable-tanned hide, aluminum, plastic. Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023.

Cover Image: Sasha Wortzel, Sitting

Shiva [detail], 2020 Burmese Python skin, vegetable-tanned hide, aluminum, plastic. Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023.

Diedrick Brackens

Ali Cherri

Christine Howard Sandoval

Candice Lin

Rose B. Simpson

Eve Tagny

Sasha Wortzel FEB

Thick as Mud explores how mud animates relationships between people and place through the work of eight contemporary artists. Across multiple geographies and a range of aesthetic approaches—from figurative clay sculpture to audio recordings of the swamp—these artists engage mud as a material or subject that shapes personal and collective histories, memory, and imagination. Each artist brings a distinct perspective to the theme, conjuring dynamics embedded in the landscape that include colonial and racialized forms of dispossession, cultural reclamation, narratives of self-actualization, and ecological loss and adaptation.

Mud moves through the exhibition as a metaphor as well as a tangible material. Both water and earth, mud exists in an in-between state. A medium that dissolves binaries, mud invites a blurring of past and present, personal and political, bodies and landscape, feeling and knowing. In various ways, the artworks in Thick as Mud move across these porous boundaries, disrupting linear narratives and dominant hierarchies that shape which places and stories matter.

Across the artworks, mud becomes an agent of time and transformation and a medium of decomposition and creation. As such, Thick as Mud tracks the afterlives of violence against people and the environment while also evoking the potential for regeneration. The exhibition is an invitation to ask what lives in the mud and to reconnect with the possibilities for knowing differently that this material holds.

— NINA BOZICNIKInstallation view of Thick as Mud, 2023. Foreground: Rose B. Simpson; Background: Diedrick Brackens.

born 1981, Polokwane, South Africa; lives in Johannesburg, South Africa

Dineo Seshee Bopape examines personal, collective, and planetary memory across a practice that includes video, sound, light, and elemental matter like soil, crystals, and herbs. She combines materials in alchemical ways, creating works that address the residual wounds of historical trauma inflicted by racial and colonial violence against people and the Earth.

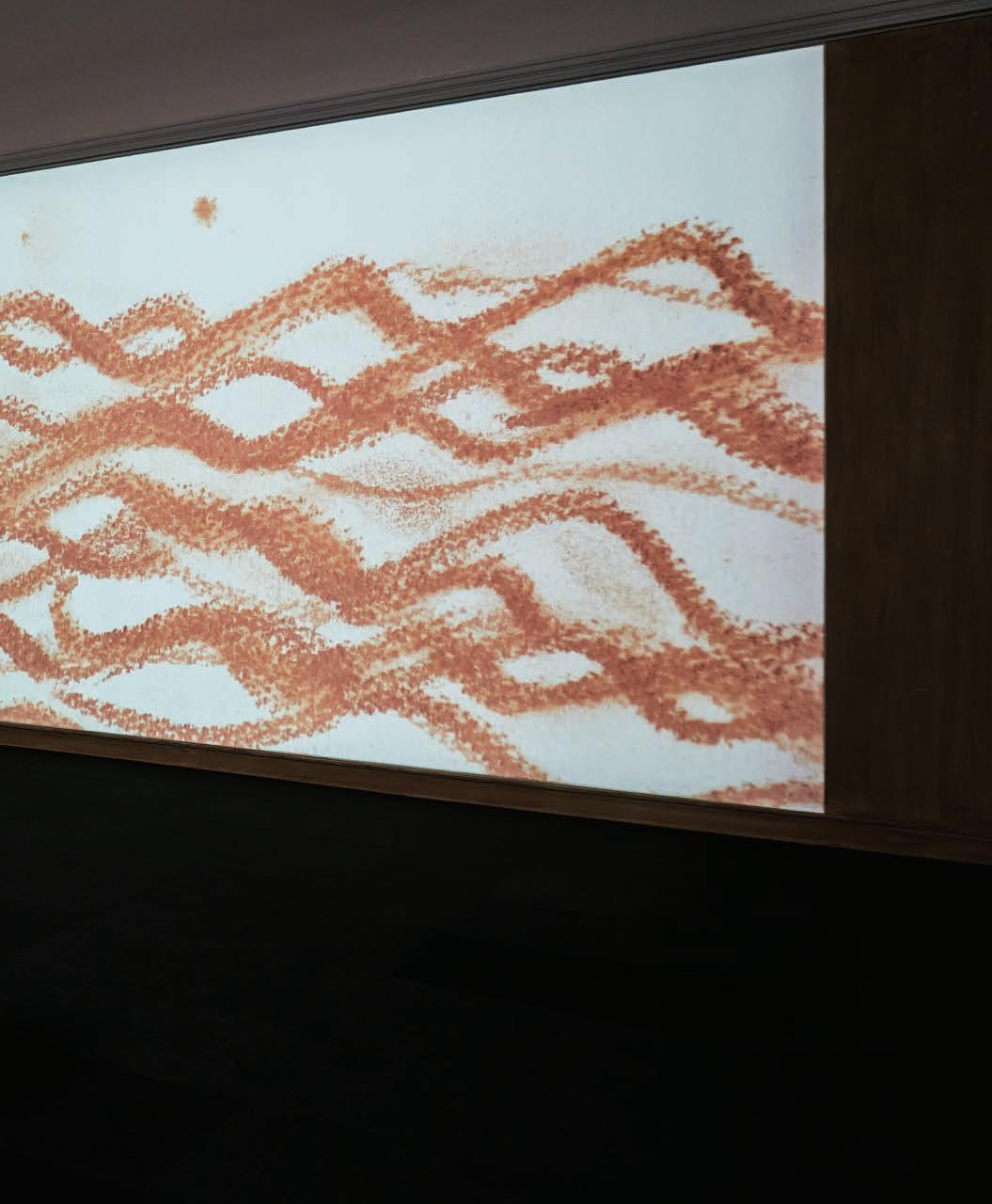

Bopape’s immersive installation, Master Harmoniser (ile aye, moya, là, ndokh), is an animated video and sound environment made from soil and water collected from places that played historical roles in the transatlantic slave trade: Virginia, Louisiana, Senegal, Ghana, and South Africa. Bopape’s dizzying animation conjures the memory of enslavement and forced migration that connects these dispersed places across time and geography.

The tactile, visual marks that comprise the animation are a response to widely circulated abolition-era images depicting the heavily scarred back of a formerly enslaved man in Louisiana,

known as either Peter or Gordon. Sounds of water, wind, human cries, and music accompany the imagery and amplify the dislocation, horror, and resistance that Peter’s story of enslavement and escape embodies. Bopape titled this work ile aye, moya, là, ndokh—the four elements (earth, wind, fire, and water) in four different African languages (Yoruba, Nguni/Sepedi, Ga, and Wolof, respectively)—conjuring the multivocal tongue spoken by the African diaspora and the relationship of ancestral memory to other potent, foundational life forces.

Mud from Pacific Northwest waterways covers the walls in the Henry installation, inviting viewers to recollect relationships between this region and global histories. The story of Charles Mitchell, an enslaved boy in Washington Territory who escaped to freedom in British Columbia in September 1860, appears as a footnote in the history of the Pacific Northwest, but is revelatory of the region’s entangled history with slavery, Black disenfranchisement, and resilience.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Master Harmoniser (ile aye, moya, là, ndokh), 2021. Digital animation (color, sound); 25:08 mins. Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Master Harmoniser (ile aye, moya, là, ndokh), 2021. Digital animation (color, sound); 25:08 mins. Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023.

born 1989, Mexia, Texas; lives in Los Angeles, California

Diedrick Brackens engages questions of history and identity through weaving. Brackens sees the loom as a “space of invention,” creating narrative textiles that draw on a global range of traditions from Flemish tapestry to Ghanaian kente cloth to American quilting.1 Brackens has created a uniquely hybrid visual language and personal mythology that speaks to his own identities as a queer, Black, Southern man. Working primarily with cotton, his work gestures toward the violent histories of slavery inextricably tied to this material in the United States, while his recuperation of cotton as a medium of personal expression is an act of self-determination and healing.

Catfish are a recurring motif in Brackens’s work. Catfish are muddwelling bottom feeders often perceived as dirty or undesirable whom Brackens recasts as exalted creatures that provide both psychic and physical nourishment. In his work, catfish

act as agents of transformation and spiritual transcendence. Catfish first appeared in his work as an allegorical figure for three young Black men who drowned in Lake Mexia in Texas while in police custody on Juneteenth 1981—a story of local racial violence often retold to Brackens by his mother and grandmother. Over time, catfish have taken on a broader meaning in Brackens’s work, serving as a symbol of Black Southern culture—catfish are a staple of much regional cuisine—and as a representation of Brackens himself and, more expansively, as a reference to the soul or ancestral spirits.

1The Mint Museum, “Diedrick Brackens: Ark of the Bulrushes,” YouTube video, 7:33 mins., July 5, 2022. https://youtu.be/bMDOcxD_AI4.

Diedrick Brackens, maximum depth, 2020. Cotton and acrylic yarn. Courtesy of the artist and Various Small Fires, Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

born 1976, Beirut, Lebanon; lives in Paris, France

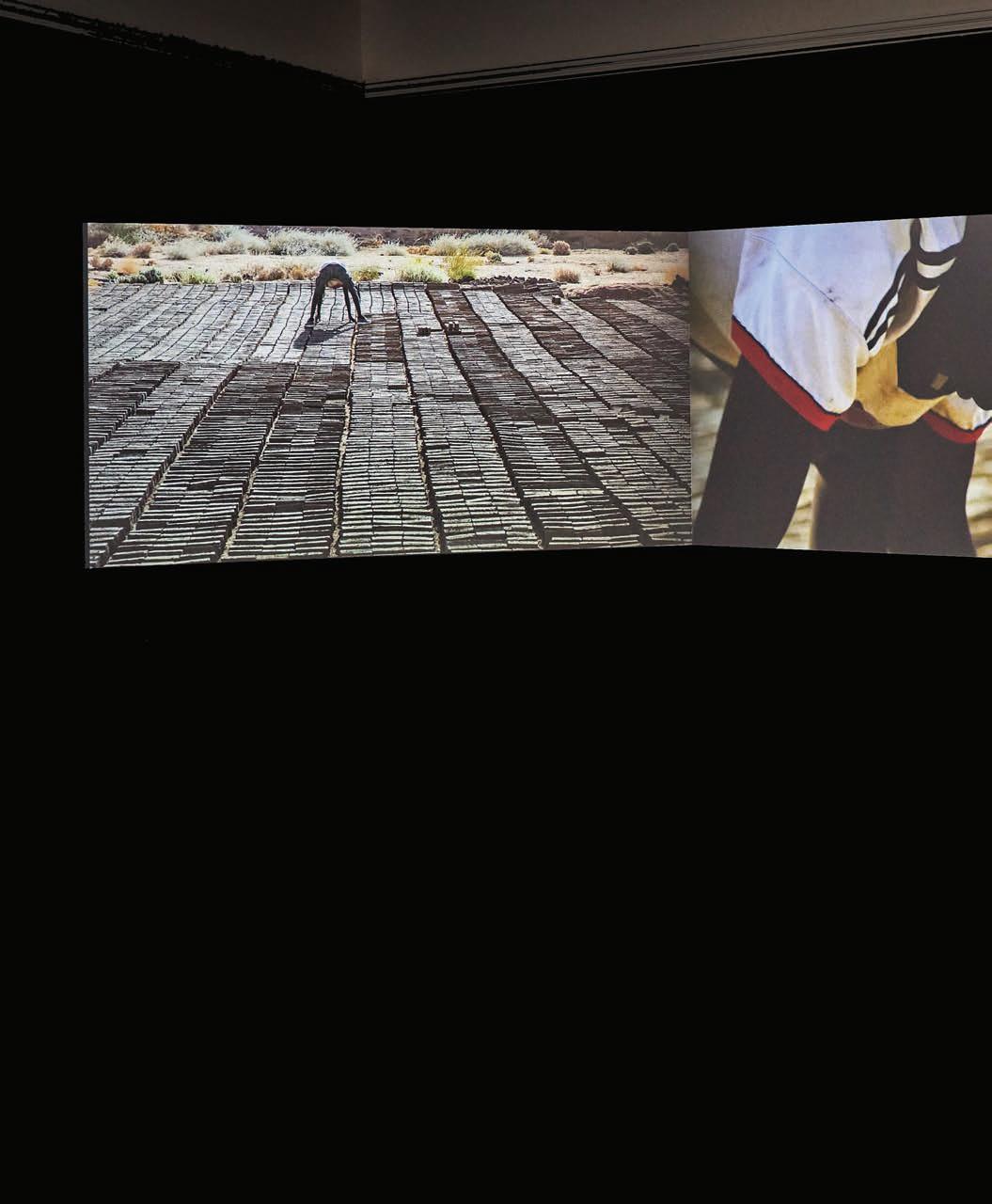

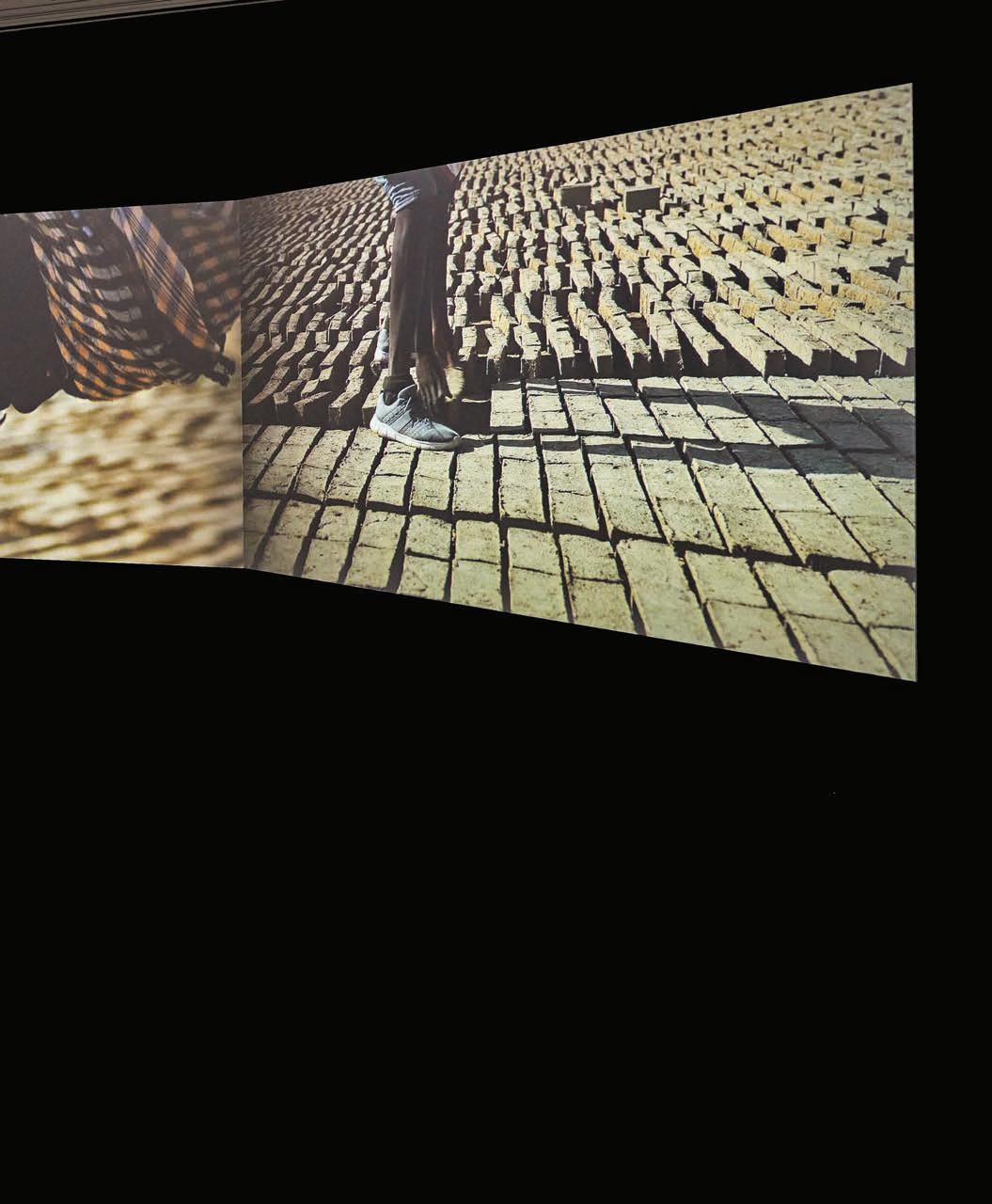

Ali Cherri’s work across film and sculpture investigates histories of nation-building, political ecologies of place, and legacies of trauma, especially in the context of the Arab world. In particular, Cherri challenges dominant narratives of social and cultural progress that often conceal harm against people and the environment.

Of Men and Gods and Mud is a threechannel video installation that traces the central role of mud and floods in creation myths from around the globe, and in the labor and lives of seasonal mud-brick workers in northern Sudan. In the film, Cherri attends to the way the construction of the Merowe Dam in the region has disrupted the Nile River’s natural flow and dramatically reshaped the local landscape, displacing many

people from the fertile Nile Valley to arid desert lands. In the past, annual flooding shaped the region through regular cycles that left fertile silt deposits in the path of receding waters. With the start of construction on the Merowe Dam in the early 2000s, this natural cycle ceased. The inundation of water buried local villages in unabated depths, and the river now flows at the command of political and economic

power. In the film, Cherri contrasts the forces of state and capital with the individual lives of regional laborers who, like the land, are subject to the authority of these forces.

Ali Cherri, Of Men and Gods and Mud, 2022. Three-channel video installation (color, sound); 18:30 mins. Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023.

Ali Cherri, Of Men and Gods and Mud, 2022. Three-channel video installation (color, sound); 18:30 mins. Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023.

The Inca, the Maori, the Babylonians, the Egyptians, the Chinese, the Hindus, the Yoruba, the Sumerians. Seas and mountains and years apart and yet they all told the same story: man out of mud.

And, indeed, We created man from an extract of clay. Out of mud we first made. Out of mud we dreamed we were made. Then we forgot, or sought to forget, and declared ourselves the makers.

Candice Lin traces legacies of colonialism and diaspora through the history of physical materials, often making associative links across time, place, and subject. Swamp Fat is an installation of ceramic frogs, snakes, and lizards that contain solid perfume made from animal lard infused with the smell of rotting vermin. This work emerged from Lin’s investigations into cultural perceptions around contamination in relation to the construction of race and citizenship within the bayous of Louisiana in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Lin’s ceramic vessels are made of clay collected from near St. Malo, Louisiana, thought to be the site of the first Asian American settlement in the United States, and which was previously inhabited by escaped slaves and Indigenous peoples. Established by escaped Filipino indentured laborers in the mid-eighteenth century, St. Malo existed in the swamp, protected from the reach of government officials. Set atop ornate pedestals made from scagliola, a faux marble decoration popular in seventeenth-century Italian

architecture, Lin’s creaturely vessels honor the swamp and the community who made a life there beyond the restrictions of white society.

Inside the ceramic vessels, Lin’s wearable perfume emits an odor of rot, interrogating social fears of pestilence and impurity that have historically been associated with racialized bodies. The animal fat used to make the perfume conjures additional associations, including the Slaughterhouse Cases brought before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1873. Precipitated by the issue of animal waste polluting the Mississippi River, alongside questions of labor and property rights, the case ultimately resulted in a decision that severely restricted the Fourteenth Amendment, disempowering newly free Black Americans whom the amendment was originally intended to protect.

Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023. Christine Howard Sandoval.

Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023. Christine Howard Sandoval.

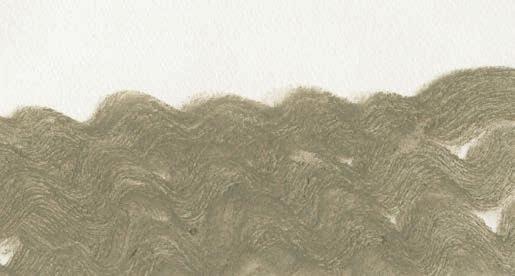

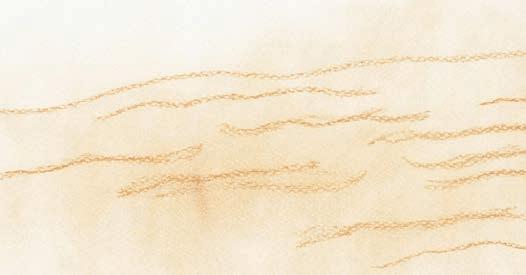

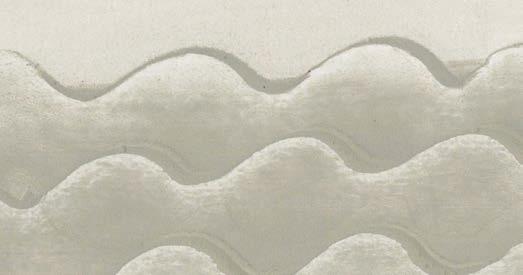

born 1975, Anaheim, California; lives in Vancouver, British Columbia

Christine Howard Sandoval investigates colonial histories of inhabitation and displacement through the lens of her own relationship to land, language, cultural memory, and architecture. Her recent body of work explores the historical uses of adobe, a desert building material made from clay, sand, and soil with close connections to her familial lineage. In the eighteenth century, Howard Sandoval’s paternal Chalon ancestors were forced from their homelands and confined to the Mission Soledad during Spanish attempts to Christianize and acculturate the Indigenous inhabitants of California. Subjugated Indigenous people built and maintained the mission using adobe, a technology introduced to the region by missionaries after their experiences with Native peoples of the Southwest. Howard Sandoval’s own use of adobe is a way to process the painful past of her paternal heritage, while also reconnecting to a material with deep ties to her maternal Hispanic ancestors from the Southwest.

In her drawings, Howard Sandoval renders the mission architecture in a simplified typology. This approach is a way to contend with the ubiquity of this architecture as uncontested symbols of California history. Using souvenir models of the missions to create her drawings, Sandoval recalls the requisite assignment of building a mission model that she and her fellow classmates completed as a part of California’s educational requirements. This educational assignment came with a total lack of tending to the colonial histories of the missions, effectively erasing Indigenous peoples from California state history. Through the embodied process of mixing and working with adobe, Howard Sandoval gives agency back to the Indigenous body, asserting a Native presence into California’s shared histories.

The companion video, Niniwas- to belong here, layers found texts and imagery with body camera footage of Howard Sandoval’s movement

through Mission Soledad, creating a form of embodied drawing through the landscape. Granted access to protected areas of the site, Howard Sandoval walks the mission grounds while tenderly touching the walls of the crumbling architecture and the artifacts of former inhabitants that she encounters there. One of these objects, a large cracked metate or stone tool used for processing grain and seed, inspired Howard Sandoval’s sculpture titled Split Metate, between two worlds, which pays homage to the memory of touch, labor, and life held in the original tool.

Christine Howard Sandoval, Niniwas- to belong here [still], 2022. Single-channel video (color, sound). Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023.

Rose B. Simpson’s work in clay draws from her Tewa ancestry as Santa Clara Pueblo and a deep matrilineal heritage of ceramic artistry. She adapts a millennia-old tradition of working with clay by inventing new techniques to make forms that respond to contemporary life and express her hopes for the world.

Simpson’s figures are powerful agents of Indigenous survival in the wake of colonial violence against Native communities and the environment. Two of these figures, River Girl 1 and River Girl A, are immortal warriors that stand ready to accompany and protect each other through battle. Adorned with metal feathers that run down their backs like spikes, prayer beads for arms, and marked with a “+”—a recurring motif for the cardinal directions and journey of life in Simpson’s work—these figures don spiritual and physical armor for moving through an inhospitable world. Simpson made these embodiments of female presence and power in direct response to the epidemic of

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls that is taking place in the United States and Canada.1

Simpson’s figures are vessel forms built from layers of heavily worked clay. They exude a sense of strength through vulnerability, embodied in the properties of clay itself. Simpson approaches clay with almost spiritual intentions, saying, “The water in the clay is listening to my internal molecular water, so it’s going to respond and break [if I’m in an agitated state]… Whatever your intentions are, it listens and responds.”2 Understanding clay this way, Simpson treats her material as a living entity that requires humility, evoking a worldview of mutual relationship between the resources of the Earth and its human inhabitants.

12021 A + E: Clay, Place, and Cultural Survival with Rose B. Simpson,” Nevada Museum of Art, January 19, 2022, https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=4i-C7J_1N0c&t=2377s.

2Peter Relic, “Rose B. Simpson’s deFINE ‘Countdown,” SCADworks, February 26, 2021, https://www.scad.edu/blog/ rose-b-simpsons-define-countdown.

Installation views of Thick as Mud, 2023. Previous page and foreground: Rose B. Simpson; Background: Diedrick Brackens.

born 1986, Montréal, Québec; lives in Montréal, Québec

Eve Tagny’s work explores disrupted landscapes as sites of embodied memory. Her installation, The Carriers, brings together a selection of recent performance videos enacted within a rock quarry in Québec, the ruins of a Tuscan villa, and a construction site in a gentrifying area of Montréal. In these videos, Tagny and her collaborators perform ritual-like gestures in physical dialogue with the site itself. Bodies drape over excavated rocks at the quarry. Tagny’s own shoulder presses against a tree that has reclaimed the villa’s ruins. Hands touch a muddy stream at the construction site. These intimate gestures convey a recognition that gendered and racialized bodies, and the land, share wounds inflicted by the economic forces of extractive labor and property. In the case of the construction site, the presence of Black bodies is an act of resistance against

the ways gentrification erases the presence of racialized communities.

Tagny has set her videos within an environment of sculptural objects and architectural forms made from various construction materials, including cob—a building agent of mud and straw used in Tagny’s paternal, ancestral home of Cameroon and around the globe. Textiles installed in the space carry a residue of marks and stains of pigment made with earth and plants that Tagny collected from the construction site in Montréal and the grounds of the Tuscan villa. These textiles resonate as bodily surrogates that carry traces of history, forming tender evocations of the life that persists amid the trauma of extraction, which violates the land and the bodies of those who inhabit it.

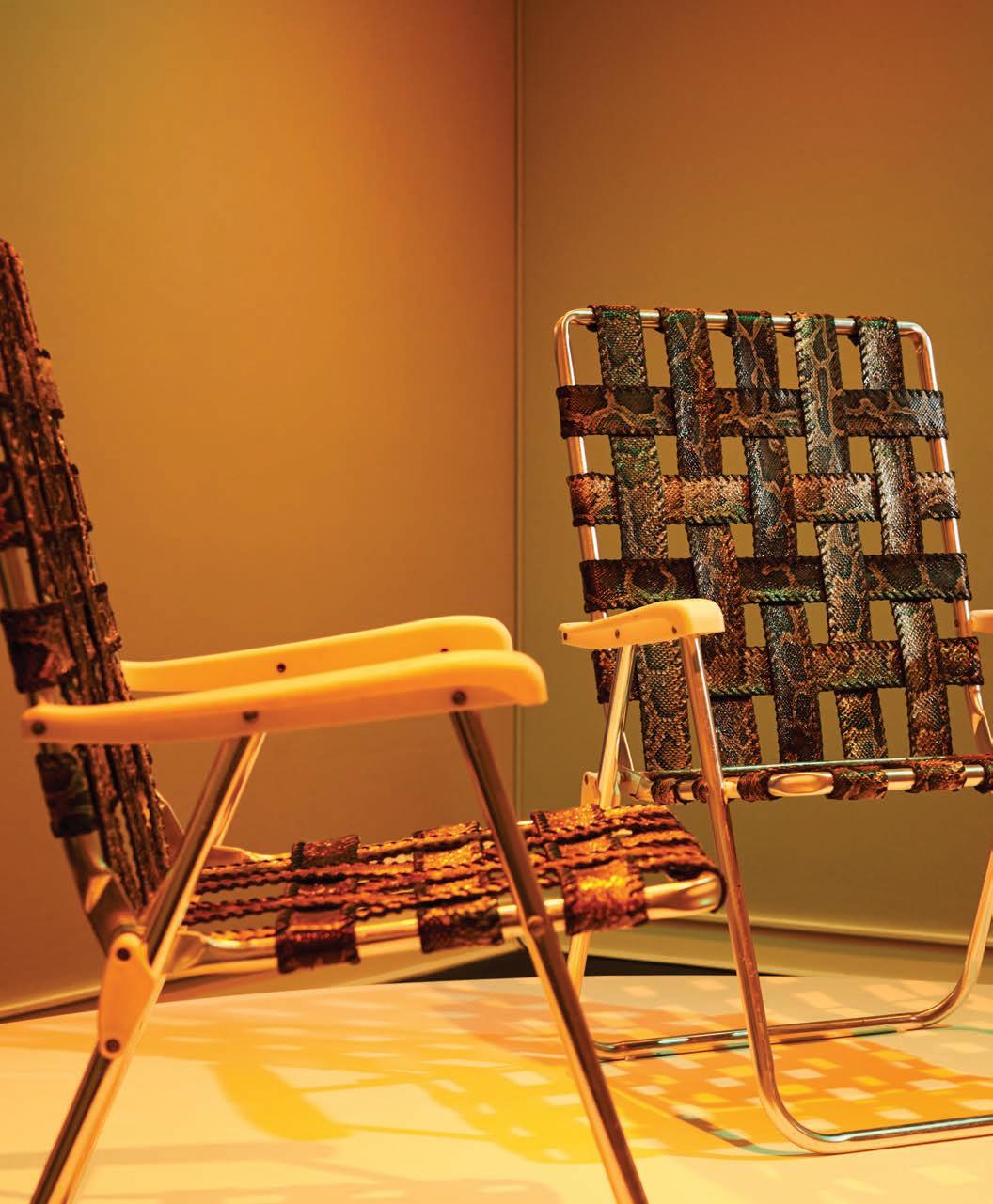

Sasha Wortzel, Sitting Shiva, 2020 Burmese Python skin, vegetable-tanned hide, aluminum, plastic. Installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023.

born 1983, Fort Myers, Florida; lives in Brooklyn, New York

Across film and expanded forms of cinema, Sasha Wortzel explores queer narratives and ecologies of place, with a particular focus on the social and environmental histories of South Florida, where she grew up. The tangled dynamics of desire and loss layered in that landscape form a through line in Wortzel’s work, animating the fallacies and harm of colonial conquest that reverberate across time.

Her installation for Thick as Mud is in dialogue with the changing environment of the Everglades and interdependent coastal communities. The central sculpture consists of two ordinary lawn chairs with the traditional nylon webbing replaced by the skin of Burmese python, a species that has ravaged local wildlife populations since its introduction to the area by the pet trade. Titled Sitting Shiva, a reference to the Jewish mourning ritual enacted at the time of someone’s death, Wortzel’s empty

chairs hold the memory of habitats and ways of life lost in the wake of the human-made environmental crisis. Wortzel’s reconfigured chairs interrupt traditional conceptions of a leisure lifestyle synonymous with the rapid development in South Florida, and make palpable the need for human populations to reorient their relationships to a changing environment.

Over the last century, efforts to drain the swamplands of the Everglades for agriculture and development have reengineered the workings of a vast ecosystem. In Wortzel’s installation, an immersive audio track of croaking frogs during a tropical storm resounds throughout the gallery calling forth the vitality and nourishment offered by the swamp and its waters. Wortzel makes present the life and death of an ecosystem to offer us an embodied meditation on how endings are also beginnings yet written.

Dineo Seshee Bopape (born 1981, Polokwane, South Africa; lives in Johannesburg, South Africa)

Master Harmoniser (ile aye, moya, là, ndokh), 2021

Digital animation, (color, sound); 25:08 mins. Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist & Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut/Hamburg

Diedrick Brackens (born 1989, Mexia, Texas; lives in Los Angeles, California)

maximum depth, 2020

Cotton and acrylic yarn

81 x 80 in. (205.74 x 203.2 cm)

Collection of Michael Sherman

Diedrick Brackens

mud bright sight, 2021

Cotton and acrylic yarn, polyester

sewing thread, sewing notions

43 x 40 1/2 in. (109.22 x 102.87 cm)

Collection of Suzanne McFayden

Diedrick Brackens stud double, 2019

Cotton and acrylic yarn

72 x 72 in. (182.88 x 182.88 cm)

Collection of Allison and Larry Berg

Ali Cherri (born 1976, Beirut, Lebanon; lives in Paris, France)

Of Men and Gods and Mud, 2022

Three-channel video installation (color, sound); 18:30 mins.

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Imane Farès

Christine Howard Sandoval (born 1975, Anaheim, California; lives in Vancouver, British Columbia)

Arch- A Passage Formed By A Curve, 2020

Adobe mud and graphite on paper

60 x 96 in. (152.4 x 243.84 cm)

Forge Project Collection, traditional lands of the Muh-he-con-ne-ok

Christine Howard Sandoval

The Fire, 2022

Adobe mud and graphite on paper

60 x 96 in. (152.4 x 243.84 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles

Christine Howard Sandoval

Niniwas- to belong here, 2022

Single-channel video (color, sound); 9:01 mins.

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist and parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles

Christine Howard Sandoval

Pillars- An Act of Decompression, 2020

Adobe mud and graphite on paper

60 x 96 in. (152.4 x 243.84 cm)

Forge Project Collection, traditional lands of the Muh-he-con-ne-ok

Christine Howard Sandoval

Split Metate, between two worlds, 2022

Adobe mud, tape, wood, steel

60 x 60 x 30 in. (152.4 x 152.4 x 76.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles

Candice Lin (born 1979, Concord, Massachusetts; lives in Los Angeles, California)

Swamp Fat, 2021

Scagliola, ceramic, clay, earth, mortar, lard infused with custom scent

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly Gallery. Commissioned by Prospect New Orleans for P.5.

Rose B. Simpson (born 1983, Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico; lives in Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico)

Frère 1, 2019

Ceramic, leather, steel, beads

55 x 11 1/2 x 22 in. (139.7 x 29.21 x 55.88 cm)

Collection of Lucy Sun and Warren Felson

Rose B. Simpson

Frère A, 2019

Ceramic, leather, steel, beads

54 x 11 x 20 1/2 in. (137.16 x 27.94 x 52.07 cm)

Collection of Wayee Chu and Ethan Beard

Rose B. Simpson

Protector A, 2020

Ceramic, metal, mixed media

16 x 8 x 6 in. (40.64 x 20.32 x 15.24 cm)

Collection of Lorna Meyer

Rose B. Simpson

River Girl 1, 2019

Ceramic, glaze, steel, leather, rope

43 x 14 x 14 1/2 in. (109.22 x 35.56 x 36.83 cm)

Private collection

Rose B. Simpson

River Girl A, 2019

Ceramic, glaze, steel, leather, rope

43 1/2 x 14 1/2 x 13 1/2 in.

(110.49 x 36.83 x 34.29 cm)

Collection of Tad Freese and Brook Hartzell

Rose B. Simpson

Mother A, 2019

Ceramic, glaze, leather, string, steel hardware

28 1/2 x 10 x 11 1/2 in. (72.39 x 25.4 x 29.21 cm)

Collection of Stanlee Gatti

Eve Tagny (born 1986, Montréal, Québec; lives in Montréal, Québec)

The Carriers, 2023

Site-specific installation

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist and Cooper Cole, Toronto

Installation Includes:

Shelters of ancient grains, 2022

Single-channel video (color), 16:30 mins.

Dimensions variable

Mnemonic Gesture, 2020

Inkjet print

28 x 24 in. (71.1 x 61 cm)

Summer [Gestures to reignite

fossilized landscapes], 2020

Single-channel video (color, sound); 1:02:04 hrs.

Dimensions variable

Unadorned Landscapes, 2022

Single-channel video (color); 10:28 mins.

Dimensions variable

Sasha Wortzel (born 1983, Fort Myers, Florida; lives in Brooklyn, New York)

Sitting Shiva, 2020

Burmese Python skin, vegetabletanned hide, aluminum, plastic

23 x 36 in. (58.42 x 91.44 cm)

Courtesy of the artist

Sasha Wortzel

Tropical Storm, 2023

Audio; 15:16 mins.

Courtesy of the artist

Thick as Mud is organized by Nina Bozicnik, Curator.

Lead support for this exhibition is provided by generous gifts from David and Catherine Eaton Skinner and William True. Additional support is provided by Jessica Silverman, Jack Shainman Gallery, Stanlee R. Gatti, and Lorna Meyer Calas and Dennis Calas. Media sponsorship generously provided by The Seattle Times. Hospitality sponsorship provided by Graduate Seattle.

Nina Bozicnik

Adam Monohon

Mariah Ribeiro

TEAM HENRY

Sophia Anderson

Maisea Bailey

Erin Baldner

Tanja Baumann

Emily Blanche

Nina Bozicnik

Margarita Burnett-Thomas

Kat Carter

Harold Churchill III

Fiona Clark

Hannah Hunt Corpuz

Madeleine Craig

Jeff Deveaux

Stephanie Eistetter

Stephanie Fink

Orlando Francisco

Aliyah Baruso

All images by Jonathan Vanderweit unless otherwise noted.

Nan Garrison

Trevor Goosen

Drea Harper

Claire Kenny

Rachel Ann Kessler

Danielle Khleang

Laura Kinney

JeeSook Kutz

Tony Lasley

Rebecca Lawler

Summer Li

Sophia Marciniak

Markie Mickelson

Shamim M. Momin

Adam Monohon

Alicia Murillo

Tricia Pearson

Nick Pironio

Rubina Postma

Ann Poulson

Emma Rowley

Bob Rini

David Smith

Sage Sommer

Phil Steyh

Tiffany Turpin

Lena Whittle

Vivian Wick

Sylvia Wolf

Eric Zimmerman