VOL. 18 NO. 1

IN THIS ISSUE

Marleen Peumans, David Geštakovski, Jacopo Mattiussi and Kostas Karagiannopoulos

Injection moulding technique with injectable composites: quick fix or long-lasting solution?

Robert E. Grover, Kenneth S. Serota

Treatment of compromised teeth: The usual suspects

Surina Sehgal

Medically compromised and vulnerable mouths

Clarence Tam

Anterior case with Clearfil Majesty™ ES-2 Premium

Wallid Boujemaa

Simple chords of shades for harmonious restorations

Meenakshi Lall

Management of stained fluorotic teeth

Vladimir S Todorovic, Inus Snyman, Andre W van Zyl

Masterclass in Implant Dentistry

Lateral window Sinus Floor Elevation technique

Linda Greenwall

Composite smile makeover: A case study

Rachel Derby and Julia Glancey

The process of the dentist and technician. A denture story

The clear choice for a beautiful smile

henryschein.com.au

04 Clinical Injection moulding technique with injectable composites: quick fix or long-lasting solution?

Marleen Peumans, David Geštakovski, Jacopo Mattiussi and Kostas Karagiannopoulos

12 Clinical

Treatment of compromised teeth: The usual suspects

Robert E. Grover, Kenneth S. Serota

20 Clinical Medically compromised and vulnerable mouths

Surina Sehgal

24 User Report

Anterior case with Clearfil Majesty™ ES-2 Premium

Clarence Tam

28 Clinical Simple chords of shades for harmonious restorations

Wallid Boujemaa

36 Clinical Management of stained fluorotic teeth

Meenakshi Lall

44 Masterclass in Implant Dentistry

Lateral window Sinus Floor Elevation technique

Vladimir S Todorovic, Inus Snyman, Andre W van Zyl

50 Clinical Composite smile makeover: A case study

Linda Greenwall

56 Clinical

The process of the dentist and technician. A denture story

Rachel Derby and Julia Glancey

62 Products

28 50 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 1 Contents Volume 18 No. 1 WEBINAR WEEK MONDAY 19 JUNE - THURSDAY 22 JUNE 1 CPD POINT PER WEBINAR READ MORE 4 44

Vinnies CEO Sleepout

The Vinnies CEO Sleepout takes place on a chilly winter night, known as one of the longest and coldest nights of the year. It is an annual event where numerous CEOs, business owners, community leaders, and government officials come together to spend the night outdoors. The purpose of this event is to show support for the homeless individuals and those at risk of homelessness in Australia.

While a single night may seem brief, its impact can be significant. Hence, Henry Schein’s executive team is enthusiastically joining this year’s sleepout. They will be sleeping outside alongside other participants, immersing themselves in an enlightening experience aimed at raising awareness and shedding light on the harsh realities faced by the homeless population.

In 2022, Mike Covey Henry Schein’s VP & Managing Director Dental ANZ participated in this event and was able to raise over $9,000 towards the cause. This money went towards providing emergency accommodation for families in crisis, keeping power on throughout the winter, and relocating a person sleeping rough to accommodation services.

The hope for this year is that we are again able to provide funds required to support those in need, whilst also raising awareness.

Vol. 18 No. 1

ISSN 2071-7962

PUBLISHING EDITOR

Ursula Jenkins

EDITOR

Dr Andre W van Zyl

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Prof Cecilia Goracci

Prof Simone Grandini

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EMERITUS

Prof Dr Marco Ferrari

EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Prof Paul V Abbott

Dr Marius Bredell

Prof Kurt-W Bütow

Prof Ji-hua Chen

Prof Ricardo Marins de Carvalho

Prof Carel L Davidson

Prof Massimo De Sanctis

Dr Carlo Ercoli

Prof Roberto Giorgetti

Dr Johan Hartshorne

Dr Patrick J Henry

Prof Dr Reinhard Hickel

Dr Sascha A Jovanovic

Dr Gerard Kugel

Prof Ian Meyers

Prof Maria Fidela de Lima Navarro

Prof Hien Ngo

Dr Hani Ounsi

Prof Antonella Polimeni

Prof Eric Reynolds

Prof Andre P Saadoun

Prof Errol Stein

Prof Lawrence Stephen

Prof Zrinka Tarle

Prof Franklin R Tay

Prof Manuel Toledano

Dr Bernard Touati

Prof Peet van der Vyver

Prof Laurence Walsh

Prof Fernando Zarone

International Dentistry - Australasian Edition is published by Modern Dentistry Media CC, 15 Martinique, Calderwood Rd, Johannesburg 2062, South Africa

Tel: +27 11 702-3195 • Fax: +27 (0)86-568-1116

E-mail: dentsa@iafrica.com

www.moderndentistrymedia.com

© COPYRIGHT. All rights reserved.

No editorial matter published in International Dentistry - Australasian Edition may be reproduced in any form or language without the written permission of the publishers. While every effort is made to ensure accurate reproduction, the authors, publishers and their employees or agents shall not be held responsible or in any way liable for errors, omissions or inaccuracies in the publication whether arising from negligence or otherwise or for any consequence arising therefrom.

Published in association with

2 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1

Mike Covey at the CEO Sleepout.

Injection moulding technique with injectable composites: quick fix or long-lasting solution?

Introduction

1 Professor Marleen Peumans (Belgium) graduated at the KUL (University of Leuven, Belgium) and is specialised in adhesive dentistry. Currently, she is head of the department of restorative dentistry of the same university.

2 Dr David Geštakovski (Croatia) graduated at University of Zagreb. After graduation he moved on short period of time to work in Dublin (Ireland). Nowadays he works in private dental office in Zagreb. He is member of Croatian Academy of Aesthetic Dental Medicine and European Society of Cosmetic Dentistry.

3 Dr Jacopo Mattiussi (Italy) graduated in Dentistry and Dental Prosthetics with honours at the University of Genoa. Currently, he is working in several dental practices in the conservative, prosthetic and endodontic field with a particular passion and attention for aesthetic and adhesive dentistry.

4 Dr Kostas Karagiannopoulos (United Kingdom) graduated at the Queen Mary University, whereafter he specialized in prosthodontics in King’s College (London, UK). Passionate about education and comprehensive dentistry, he is currently offering patient care in two specialist clinics near London and teaching training specialists at King’s College.

The injection moulding technique with injectable composites, which became known to dentists worldwide due to the work of Dr Douglas Terry, has become increasingly popular in the latest years.

It is a relatively simple procedure that makes it possible to obtain a predicable end result, even in complex situations, because the morphology can be determined in advance.

It is in part because of the development of suitable, high quality materials, such as G-ænial Universal Injectable and Exaclear that injection moulding is a reliable procedure. G-ænial Universal Injectable has the ideal consistency and mechanical properties and thus it is widely used for this technique.

Combined with the highly transparent Exaclear silicone, the technique has become approachable and easy to conduct. In the following overview, it is shown how the restorations that were made with this technique can stand the test of time.

Because of its high wear resistance, G-ænial Universal Injectable can also be used to restore occlusal surfaces. This is particularly useful in case of abrasion/erosions in the molar area and has the advantage that it can be used in a minimally invasive way. In these cases, careful planning is imperative to restore the function in a correct manner. Injection moulding is a valuable method for a correct restoration of a physiologic

CLINICAL 4 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Marleen Peumans,1 David Geštakovski,2 Jacopo Mattiussi3 and Kostas Karagiannopoulos4

Case 1: Restored occlusion after severe general wear by Professor Marleen Peumans, Belgium

Figure 1A: Worn occlusal surfaces and maxillary diastema before treatment. The colour of the teeth, discloses the loss of surface enamel, with the colour of the dentine clearly showing through.

occlusion with the aid of digital modelling techniques.

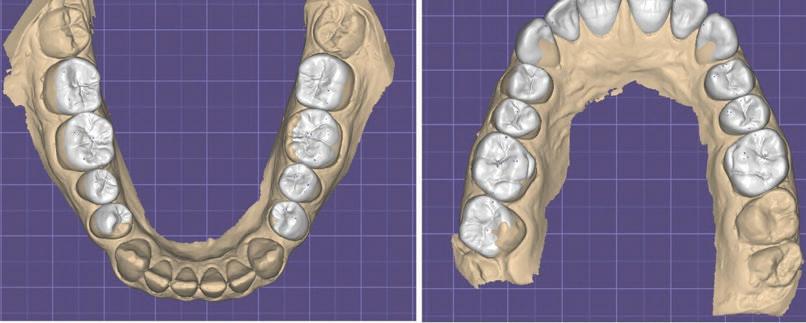

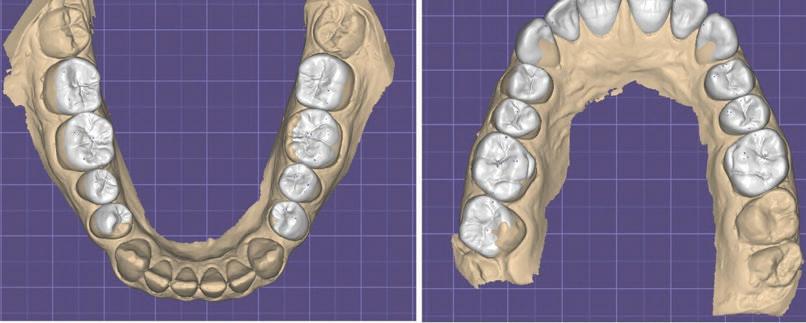

Two models were printed: one with every second tooth restored and another one with all teeth restored. Based on those, two transparent silicon indices were made (Exaclear, GC).

Working with two silicone indices has the advantage that

the intraoral seating is more stable, there is greater control of excess material on adjacent teeth and a better emergence profile can be created.

Four models were made in total (two per jaw). One year after treatment, the surfaces still look smooth and shiny, without obvious occlusal wear facets.

CLINICAL INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 5

Figure 1B: Computer-aided design of the restored occlusion. The diastemata between the maxillary incisors were restored as well.

Figure 1C: The two 3D-printed models of the maxilla; in model 1, every other tooth was restored, while in model 2, all teeth were restored.

Fig. 1D: Injection moulding with G-ænial Universal Injectable in a transparent mould.

Figure 1E: Restored dentition after treatment.

Figure 1F: Close-up of the fourth quadrant. Top: before treatment; Middle: at baseline (after restoration); Bottom: one year after treatment.

In the presented case, six composite veneers were made on the upper incisors and canines with the injectable moulding technique.

After facial analysis, teeth were scanned and a digital ‘wax up’ was made.

Based on the wax up, an intraoral mock-up was done to check guidance, functional parameters, aesthetics, and phonics. To get long lasting results, function needs to be planned in a correct way.

Therefore, canines were included to obtain canine guidance in order to avoid potentially harmful contacts and forces on incisors, which may cause chipping of the

restorations. Because of the low lip line the patient’s gingiva was not visible in the forced smile so the asymmetry in the soft tissue around the central incisors was left as before.

In this case, the silicone indices (Exaclear) were again based on two different 3D-printed models, for the same reasons as mentioned in case 1 (vide supra).

Teeth were cleaned and etched, retraction cords were packed in the sulci to prevent crevicular fluid from flowing in field of work and to avoid subgingival flow of the injectable composite.

Adjacent teeth were isolated with Teflon tape and after the adhesive protocol (G-Premio BOND, GC), G-aenial

Universal Injectable (GC) was injected and polymerised directly onto the teeth.

A1 shade was used for the incisors, while the canines were done with A2. For finishing and polishing, a scalpel no. 12, Epitex strips (GC), a fine diamond polishing bur and silicone spirals were used.

Two years later, the restorations maintained high aesthetic quality, without chipping or marginal discolorations.

The beauty of this technique is its predictability and possibility to achieve great symmetry and marvellous primary, secondary, and tertiary morphology.

PEUMANS ET AL 6 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Figure 2A: Initial situation.

Case 2: Cost-effective aesthetic rehabilitation by Dr David Geštakovski, Croatia

Figure 2B: Checking the size of the injection holes in the silicon index (EXACLEAR, GC) on the first 3D-printed model.

Figure 2C: Result directly after treatment, showing nice shape and morphology. The gingival line was not modified since it was not visible during smiling.

2A

Figure 2D: Result after two years. The shape of the restorations was maintained, without chipping or marginal staining.

2B

Case 3: Interceptive restorative treatment of a full mandibular arch by Dr. Jacopo Mattiussi, Italy

In this case, G-ænial Universal Injectable was used to offer the patient a long-term temporary solution that did not hinder a more complex full-mouth rehabilitation in the future because the economic situation of the patient did not allow

such treatment at the moment.

In contrast to the previous cases, no CAD/CAM technique was used to make the design, but a traditional wax-up and bite registration were done.

Initial situation. The upper jaw was restored three years ago by means of a voluminous zirconia full-arch restoration of which the patient was not very satified. The lower jaw was highly chromatic in comparison, with a considerable amount of tartar, extensive destruction of the hard tissues and periodontal attachment loss.

The wax-up was made with the aim of increasing the DVO just enough to regularise the occlusal planes and curves, with obvious limitations dictated by the morphology of the upper maxillary rehabilitation.

The vertical dimension was slightly increased and occlusal planes and curves were regularised as much as the preexisting situation allowed it.

Here, only one clear silicone key was used to restore the entire lower arch was restored in a single session. The

lower are was restored per sextant. Old restorations were removed, cavity edges rounded and their surfaces sandblasted. The enamel was selectively etched before application of G-Premio Bond(GC).

Figure

result impresses in terms of aesthetics and the patient was very satisfied. It was ensured that the patient could clean all interdental spaces and at follow-up, healthy gingival tissues could be seen.

PEUMANS ET AL 8 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Figure 3B: Impression taking and facebow registration.

2B

Figure 3A:

3C: The

Figure 3D: Images taken two and a half months after treatment. Harmonised aesthetics, a normalised vertical dimension and excellent health of the soft tissues are evident from the observation.

Case 4: Treatment of localised wear of anterior teeth by Dr Kostas Karagiannopoulos, United Kingdom

A 45-year-old man presented complaining of the appearance of his front teeth. Severe localised tooth surface loss of multifactorial origin led to short clinical crowns.

Worn teeth in occlusion due to dentoalveolar compensation have the restorative disadvantage of lack of interocclusal space.

It was decided to proceed with additive composite

restorations to restore the affected teeth using the Dahl concept: this is a method of treating the localised wear of anterior teeth, without having to treat the posterior teeth. The latter are discluded and allowed to re-establish itself over time.

All primary disease was controlled prior to the restorative phase, including the intrinsic acid erosion.

PEUMANS ET AL INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 9

Figure 4D: At the 20-month follow-up, the occlusion was fully re-established. The high gloss retention of the six direct composite restorations was noteworthy, eliminating the need for repolishing.

Figure 4C: Immediate treatment result. The ability to replicate anatomic details and microtexture on the facial surface with the injection moulding technique combined with a fairly rigid stent exceeds that of all other direct composite techniques. Note the slight disclusion in the posterior area.

Figure 4B: Diagnostic wax-up on printed models.

Figure 4A: Pre-operative photographs.

Alternate technique

The alternate tooth technique was used to carry out the injection moulding technique. Once proximal and gingival excess was removed on all six restorations there was minimal finishing as the anatomy was wax-up driven and not freehand.

The final result exhibited good surface texture and lustre whilst anterior guidance was maintained.

At a follow-up appointment after 20 months, no chips, fractures or debondings were observed. The patient is a heavy smoker and sees the hygienist regularly.

Occlusal contacts were fully re-established on the posterior teeth after completion of the Dahl movements and the patient is now wearing an occlusal appliance at nights. Of note is the high gloss retention of the six direct composite restorations.

No further polishing was done on the facial surfaces during that 20 month period.

Conclusion

Injection moulding has a wide range of indications, from anterior to posterior, from interceptive to final restorations, for aesthetic as well as functional rehabilitations, without excessive requirements in terms of clinical skills.

The excellent strength and gloss retention of G-ænial Universal Injectable contribute to a maximum longevity for this type of treatment.

References:

1. Terry, DA. Restoring with Flowables. Quintessenz Publishing. 1st Edition 2017.

2. Terry DA, Powers JM. A predictable resin composite injection technique, Part I. Dent Today. 2014 Apr;33(4):96, 98-101.

3. Terry DA, Powers JM, Mehta D, Babu V. A predictable resin composite injection technique, part 2. Dent Today. 2014 Aug;33(8):12.

Reprinted with permission from GC Europe

PEUMANS ET AL 10 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

6b

Treatment of compromised teeth: The usual suspects

Introduction

The unceasing innovations and iterations in dental technologies and materials has taken the sophistication of treatment modalities to an historic level. However, when we are focused on the newness, the thrill of the outcome, we fail to pay attention to the purpose of the activity. Case in point; dental implants were initially considered the gold standard for compromised tooth replacement despite reports that endodontic therapies ensured functionality over time to be in the range of 91 percent to 97 percent.1 The newness became tarnished by reports that peri-implantitis and peri-mucositis showed a mean weighted prevalence rate of 43 percent across Europe and 22 percent across South and North America.2 A myriad of factors influences the initiation and progression of the disease, unfortunately, the treatment of peri-implant diseases is at best favorable in the short term with a high rate of persistent inflammation and recurrence.3 A study by Guarnieri et al4 showed that in chronic periodontal patients, active periodontal therapy followed by long-term regular periodontal maintenance was successful in keeping the majority of periodontally compromised teeth. In the same patients, a higher tendency for implant loss than tooth loss was found. This series of case reports will provide decision guide categories for best practices which facilitate retention of compromised teeth using endodontic therapies.

Case Report One – Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) in endodontics

Perhaps the most important advantage of CBCT in endodontics is that it demonstrates anatomic features in 3D that intraoral, panoramic, and cephalometric images cannot. In addition, because reconstruction of CBCT data is performed natively using a personal computer, data can be reoriented in their true spatial relationships.5

2 Kenneth Serota, DDS, MMSc is an ambassador of the SlowDentistry Foundation, the Digital Dentistry Society (Canada) and the CleanImplant Foundation. He has practiced endodontics in Ontario for over 35 years.

In October of 2015, a 55-year-old male patient, previously seen for treatment in the office, self-referred for a second opinion regarding the recommended removal of a suspected fractured tooth in the maxillary right quadrant. He reported that a soft swelling had become apparent over the past week. Clinical examination noted fluctuant swelling between teeth #s 1.5 and 1.4, and a 12mm probe defect was detected along the mesial-buccal line angle of tooth #1.5.

The patient provided a periapical radiograph showing a mesial-proximal peri-

CLINICAL 12 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Robert E. Grover1, Kenneth S. Serota2

1 Robert Grover, DDS, is an Assistant Professor in Endodontics at the University of Virginia Department of Dentistry and the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Dentistry. He maintains a private practice in Endodontics in Staunton, Virginia.

sagittal slice of the CBCT volume shows the lateral lesion extending to the alveolar crest. Fig 1c. The axial slice of the CBCT volume shows the extent of the rarefaction adjacent to the mesial aspect of the root and the presence of an untreated palatal canal. Fig 1d. Selective treatment of the palatal canal was performed. Calcium hydroxide was inserted in the canal space. Fig 1e. The extrusion of the interim Ca(OH)2 medicament through the sulcular area of tooth #1.5 is evident. Fig 1f. A lateral branch of the root canal space containing the obturating medium is shown exiting into the interface of the middle and apical third of the root. Fig 1g. A periapical radiograph taken four years after treatment shows osseous regeneration and the reformation of the periodontal ligament. Fig Ih. The coronal slice of the CBCT volume shows the pre-operative PRRL. Fig 1i. The coronal slice of the CBCT volume taken four years after treatment shows the resolution of the PRRL

radicular radiolucency [PRRL] associated with tooth #1.5. (Fig. 1a) The sagittal slice of the CBCT volume [Carestream CS 9000, Carestream Dental, GA] shows the extent of the lesion. (Fig. 1b) The previous root canal therapy had detected and treated the buccal canal only. The axial slice shows an untreated palatal canal. (Fig. 1d) A fiber post placed in the buccal canal was used to retain the core. The patient was advised of the misdirected anchoring pin extending into the periodontal ligament [PDL]. With the patient’s consent, it was decided to selectively treat the palatal canal.

After an interim six-week period of calcium hydroxide therapy [Ca(OH)2, UltraCal™ XS, UPI, S. Jordan UT] (Figs. 1d, 1e),6 the root canal space was obturated using a warm vertical condensation technique. 7 The obturation media was expressed into a lateral branching portal of exit. (Fig. 1f) A four-year follow-up shows resolution of the lateral lesion. (Figs. 1g, 1h, i) The initial presumption of a fractured root was proven false suggesting that illusory conditions based on insufficient data acquisition are unreliable. The use of CBCT is an imperative in endodontic procedures of any kind provided ALORA principles are followed.

Case Report Two – Root amputation (Perio-Endo Lesion)

Root resective therapy is a treatment option for molars with advanced furcation involvement. In a study by Derks et al, mandibular molars after root resection showed a survival probability of almost 80% even 20 years after root resection.8

In October of 1998, a 39-year-old-male patient presented to the office complaining of “gum tenderness” in the mandibular right quadrant. Extensive bone loss was noted inter-proximally between teeth #’s 4.7 and 4.6, however, the periodontal status of the dentition in general was within normal limits. Pulp sensibility testing of the teeth in the mandibular right quadrant identified the pulp of tooth #4.6 to be necrotic. (Fig. 2a) It was explained to the patient that successful treatment of perio-endo lesions was in general questionable/unfavourable, dependent on the severity of bone loss, root trunk length, degree of root separation, the curvature of the root to be resected, the ability to eradicate the osseous defect, pulpal status, and the restorative and

With the patient’s consent,

root of tooth #4.6

oral hygiene procedures required.

CLINICAL INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 13

the distal

was

Figure1a. An area of peri-radicular rarefaction is evident along the mesial proximal aspect of tooth #1.5. Previous root canal therapy, a pin-retained post and core supporting a zirconia crown are noted. Fig 1b. The

resected and the overlying crown portion retained. (Fig. 2b) At some point after the amputation procedure, the referring dentist [RD] splinted teeth #’s 4.7 and 4.6 with a composite/ Ribbond bridge. Twenty-two years after the initial procedure, osseous regeneration and cortication in the furcal region are evident between teeth #’s 4.7 and 4.6. (Fig. 2c)

Advancements in strategies to maintain compromised teeth in concert with a greater understanding of risk factors associated with dental implants invite a reassessment of the benefits of strategic extraction of a tooth with a questionable prognosis or of limited strategic value.9 With the use of hard and soft tissue augmentation procedures, PRF (plasma rich fibrin), minimally invasive flap design and suturing techniques

in conjunction with surgical operating microscopes, it is unreasonable to sacrifice a tooth for an implant when this venerable treatment option shows favorable prognosis and success rates.10

Case Report Three – Resorptive Defect

Progressive internal resorption or those instances with perforations of the root can be distinguished from external resorption by varied radiographic techniques. In teeth with internal resorption, the radiolucent lesion “moves” with the canal when the radiographs are taken at different angles, while in external resorption the radiolucent lesion “moves” outside of the canal.11,12

In March of 1999, a 47-year-old female patient presented to the office with facial swelling; tooth #1.1 was tender to percussion. A periapical radiograph (Fig. 3a) of the maxillary anterior sextent showed large Class III and IV restorations. Tooth #1.1 exhibited peri-apical rarefaction. Tooth #2.1 showed internal resorption at the mid-root level. The patient reported that tooth #2.1 had been traumatized some 35 years prior. In the absence of CBCT imaging, it was assumed that the resorption perforated the facial aspect of the root and disrupted the overlying cortical bone.

Pulpal sensibility testing of the teeth in the anterior determined that tooth #1.1 was pulpless. The tooth was

GROVER / SEROTA

14 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Fig 2a: Loss of bone between teeth #’s 4.7 and 4.6 and the loss of the PDL around the apical region of the mesial and distal root are evident. Fig 2b: The distal root has been resected; the degree of bone loss appears to have increased. Fig 2c: A 22-year follow-up shows regeneration of the lost interproximal bone and cortication of the alveolar crest.

has been

MTA to

level of the resorptive defect as it demonstrates minimal root discolouration. Were the tooth be treated today, the choice of obturation material would be Endosequence BC putty [Brassler USA, Savannah, GA]. Fig. 3c. The PRRL associated with tooth #1.1 has resolved. The resorptive defect has been reduced in size, radiolucent deposits are evident within the resorptive crypt. Fig. 3d. The sagittal slice of the CBCT volume shows an intact cortical plate. The presence of calcified deposits is evident in the residual resorptive defect which has been significantly reduced.

endodontically treated and obturated using a warm vertical condensation technique. Tooth #2.1 was instrumented to the incisal level of the resorptive defect, and the canal sealed with white MTA.13 Figs 3a & 3b show the pre-operative and post-operative radiographs taken in 1999. (Figs. 3c & 3d) show the healing after 21 years. Currently, there is a trend towards the use of an injectable platelet-rich fibrin (i-PRF) regenerative approach to resolve internal resorptive defects that shows great potential for long-term healing.14

Case Report Four – Cracked Tooth

In a study of 2086 cracked teeth by Krell and Caplan,15 the most common teeth demonstrating fracture were mandibular second molars (36%) followed by mandibular first molars (27%) and maxillary first molars (18%). There were no statistically significant differences in success based on pulpal diagnosis (irreversible pulpitis, 85%; necrosis, 80%; previously treated, 74%), patients’ age, sex, year of treatment, tooth type, restorative material, or number of restored surfaces at the time of examination.

In July of 2014, a 45-year-old female patient presented to the office with a chief complaint of swelling in the distal papilla of tooth #1.4 for a period of 10 days. Clinical examination

revealed an occlusal amalgam restoration with a probeable seam in the distal marginal ridge [DMR]. The probe depths along the distal-buccal and lingual line angles of the tooth demonstrated an infrabony pocket of 8mm. The peri-apical radiograph taken showed a small amalgam restoration with a vertically angulated radiolucency interproximally between teeth #’s 1.4 and 1.5. (Figs. 4a & 4b) shows a fracture line extending into the mesial marginal ridge. The tooth was assessed for vitality with thermal and EPT tests which elicited no response.

The treatment options were explained to the patient; 1) removal, 3-unit fixed bridge, 2) removal, soft and hard tissue augmentation, and implant retained restoration or 3) root canal therapy and restoration with cuspal protection. The patient was advised that option 3 had a questionable prognosis; however, for financial reasons, she chose to proceed with that option.

It should be noted that management of cracked tooth syndrome varies based on the severity of the symptoms and depth of tooth structure involved. Endodontic therapy was performed using a warm vertical condensation technique. (Fig. 4c) The access preparation was sealed with a flowable and hybrid composite restoration. The radiograph taken at

GROVER / SEROTA 16 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Figure 3a. The intraoral periapical radiograph reveals a PRRL at the root terminus of tooth #1.1. A large area of internal resorption is evident mid-root of tooth #2.1. The resorption has perforated the lateral aspect of the root causing disruption of the interproximal bone. Fig. 3b. A post-operative radiograph shows the endodontic treatment of #1.1. Tooth #2.1

sealed with white

the incisal

defect is evident along the distal proximal aspect of the root of tooth #1.5. Fig. 4b. Debris present in the [DMR] of the tooth #1.4 demonstrates a fracture line, however, there is no indication of cuspal separation. Removal of the amalgam revealed extension of the fracture into the cuspal stress plane of the buccal and axial line angle. Fig. 4c. The root canal space was obturated using a warm vertical condensation technique. Lateral branches of the root canal system are noted. The tooth was restored with a bonded composite restoration using the Bioclear Matrix System developed by Dr. David Clark, DDS [Tacoma, WA]. Fig. 4d. A post-operative peri-apical radiograph taken in 2020 shows osseous regeneration and reformation of the PDL in the infra-bony defect along the distal aspect of the root.

a six-year follow-up [2020] showed osseous regeneration in the interproximal area eliminating the periodontal defect. The treatment planning process demands the inclusion of a myriad of data pertaining to the status of the tooth and root structure. The Decision Guide of the American Association of Endodontics encourages the clinician to consider local and systemic case-specific issues, economics, the patient’s desires and needs, esthetics, potential adverse outcomes, and ethical factors. The treatment performed must reflect best practices for the patient’s needs [www.aae.org/treatment options.

References

1. Friedman, S.; Mor, C. The success of endodontic therapy –healing and functionality. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 32, 493503.

2. Dadresanfar, B.; Rotstein, I. Outcome of Endodontic Treatment: The Most Cited Publications. J. Endod. 2021, 22, S0099-2399.

3. Bhide, V. Regenerative Surgical Therapy for the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis: A Case Report. Oral Health, 2021.

4. Guarnieri, R.; Di Nardo, D.; Di Giorgio, G.; Miccoli, G.; Testarelli, L. Longevity of Teeth and Dental Implants in

GROVER / SEROTA

INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 17

Figure 4a. An 8mm infrabony

Patients Treated for Chronic Periodontitis Following Periodontal Maintenance Therapy in a Private Specialist Practice: A Retrospective Study with a 10-Year Follow-up. Int J. Perio. Rest. Dent. 2021, 41, 89-98.

5. Scarfe, W.C.; Levin, M.D.; Gane, D.; Farman, A.G. Use of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Endodontics. Int. J. Dent. 2009, 2009, 634567.

6. Schilder, H. Filling Root Canals in Three Dimensions. J. Endod. 2006, 32, 281-290.

7. Kim, D.; Kim, E. Antimicrobial effect of calcium hydroxide as an intracanal medicament in root canal treatment: a literature review – Part I. In vitro studies. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2014, 241252.

8. Derks, H.; Westheide, D.; Pfefferle, T.; Eichkholz, P.; Dannewitz, B. Retention of molars after root-resective therapy: a retrospective evaluation of up to 30 years. Clin. Oral. Invest. 2017, 22, 1327-1335.

9. Fu, J-H.; Wang H-L. Breaking the wave of peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000, 2020, 84, 145-160.

10. Alkahtany, M. Saving a Natural Tooth in the Implant Era: A Case Report on Noninvasive Surgical Root Amputation. J. Contemp. Dental Practice, 2021, 947-950.

11. Trope, T.; Chivian, N. “Root resorption,” in Pathways of the Pulp, S. T. Cohen and R. Burns, Eds., 1994, 486–512, C.V. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo, USA, 6th edition.

12. Kandalgaonkar, S.D.; Gharat, L.A.; Tupsakhare, S.D.; Gabhane, M.H. Invasive cervical resorption: a review. J. Int. Oral Health, 2013, 5, 124-130.

13. Jacobovitz, M.; de Lima, R.K.P. “Treatment of inflammatory internal root resorption with mineral trioxide aggregate: a case report,” Inter. Endod. J., 2008, 41, 905–912.

14. Pruthi, P.; Yadav, N.; Nawal, R.R.; Talwar, S. Novel use of PRF and PDT in the management of trauma induced root resorption and infrabony defect. J. Clin. Diag. Res., 2015, 9, ZD26-ZD28.

15. Krell, K.V.; Caplan, D.J. 12-month success of Cracked Teeth Treated with Orthograde Root Canal Therapy. Endod. 2018, 44, 543-548.0.

This article was originally published in Oral Health May 2022 and has been reprinted with permission. Grover RE, Serota KS. Treatment of Compromised Teeth: The Usual Suspects. Oral Health May 2022

GROVER / SEROTA 18 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Figure 4e

Ackuretta 1300 65 88 22 henryschein.com.au

Medically compromised and vulnerable mouths

Surina Sehgal1

When it comes to mouths, it’s not just the teeth that are sensitive. The soft tissues too can become sore or uncomfortable for a variety of reasons.

Patients with medically compromised mouths – and also those with aphthous ulcers, lichen planus or dry mouth – are more prone to soft tissue irritation. This is very uncomfortable for the patient.

Being vulnerable or medically compromised means that as healthcare professionals we should provide special care and consideration when providing treatment or health advice.

In this article, I’ll outline how mouths can become sensitive or vulnerable, how this links to oral health and what we, as dental professionals, can do to help.

Who is medically compromised/vulnerable?

Several medical conditions and drugs can affect teeth, gums and the soft tissues of the mouth, including, but not limited to:

• High blood pressure

• Heart disease

• Diabetes

• Kidney/lung disease

• Osteoporosis

• Rheumatoid arthritis

• Cancer patients

• Pregnancy

• Eating disorders

• Patients on several medications. These patients are more susceptible to developing cavities, periodontal disease and require specific attention to help prevent these oral diseases.

20 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

CLINICAL

1 Surina Sehgal, BDS Private Practice, London, UK

Oral health implications

One of the main ways that these diseases can affect oral health is through decreased salivary flow.

Salivary flow has a direct link to balanced oral health. A commonality in medically compromised patients is that they experience xerostomia (dry mouth) as a result of their illness or as a side effect of treatment/medication.

A dry mouth creates an ideal environment for pathogenic microorganisms to develop, live and multiply. This can further complicate patients’ health by increasing the risk of other inflammatory diseases.

There is strong research to show direct links between periodontal disease and systemic health (Steele, 2016).

With a decrease in salivary flow, there is an increase in pathogenic biofilm. This means more oral inflammation, which in turn links to gum disease, bone loss, tooth loss and caries.

In the medically compromised patient’s oral environment, natural remineralisation and protection are diminished due to reduced free salivary calcium and phosphate ions, as a result of decreased salivary production and flow (Gonzalez, 2014).

In addition to the risks to their oral health, these patients can experience significant discomfort and soreness. This is a result of reduced lubrication and moisture in the mouth.

Soft tissues conditions

Conditions specific to the mouth can also be a source of pain and discomfort for some patients.

The following conditions are commonly found in an intraoral examination.

Aphthous ulcers

This ulcer is the most common ulcerative condition of the oral mucosa. It presents as a painful punched out sore on oral mucous membranes. Twenty per cent of the population have one or more, at least occasionally.

They can be a manifestation of systemic disease. However, the exact reason why an aphthous ulcer develops is unclear.

Children are also susceptible to mouth ulcers. Research shows those who have a weakened immune system, several allergies, high stress environment, poor nutrition, and certain medication can play a part in the development of mouth ulcers.

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects 1-2% of the population. Oral lichen planus presents in

different forms: reticular, atrophic/erosive, plaque-like and sometimes is of mixed types.

Soft tissue irritation can have a detrimental impact on a patient’s oral hygiene. This is due to the discomfort of using a toothbrush or certain products in the mouth.

The goal of managing these oral soft tissue conditions is to ease symptoms for patients, and to recommend certain products that can help improve their oral hygiene experience.

How can dentists help?

Biofilm removal and control is an essential part of oral health. In addition to regular dental hygiene visits and regular toothbrushing, interdental plaque removal is essential.

Carrying out topical fluoride treatment and recommending patients high fluoride treatments can aid in the prevention of caries.

Using specific oral care products is also important to protect the mouths of those who are medically compromised. One ingredient – sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) – should be avoided for those with sensitive/vulnerable mouths.

SLS is a foaming agent and there are studies to show this is a skin irritant for some (Branco et al, 2005; Oosterhaven, 2019). It can cause ‘tissue sloughing’ when the skin of the inner cheeks can peel, resulting in an irritated sensation (Green et al, 2019).

We can encourage patients to choose certain oral care products that are beneficial for oral health and take into consideration the oral soft tissues. Choosing SLS-free products is appropriate for sensitive mouths as it helps to avoid skin irritation.

As dental professionals, it is our duty to ensure we are tailoring our advice to a patient’s specific needs. We must take into account their medical history, their lifestyle and conditions, which will alter our oral health advice to them.

Further reading

Aphthous ulcers: www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/ default?id=aphthous-stomatitis-90-P01843

Lichen planus: dermnetnz.org/topics/oral-lichen-planus

This article first appeared in Clinical Dentistry and has been reprinted with permission. Sehgal S (2023) Medically compromised and vulnerable mouths. Clinical Dentistry 3(1): 74-75’

CLINICAL INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 21

Colgate Optic White Range

Colgate Optic White Light Up Dentist Exclusive Kit, Professional Take-Home Teeth Whitening Kit: Reveal your whiter, brighter smile with Colgate® Optic White® Light-Up Dentist Exclusive Kit. A Professional, Take-Home Teeth Whitening Kit with an LED Teeth Whitening Device, Whitening Serum Pen and 6% hydrogen peroxide, for dramatically whiter teeth in 5 days*.

*10 minutes a day for 5 days. Use as directed.

Colgate Optic White Light Up 10% Hydrogen Peroxide Dentist

Exclusive, Professional in-chair Whitening Kit: Our best in-office teeth whitening technology. Reveal your patient’s whiter, brighter smile with Colgate Optic White Light-Up In-Office Teeth Whitening Kit. A Professional Teeth Whitening Kit exclusive to dentists with an LED Teeth Whitening Device, Whitening Serum Pen containing 10% hydrogen peroxide, for dramatically whiter teeth in 1 visit*

*30 minutes treatment. Use as directed.

Colgate Optic White Light Up Dentist Exclusive Kit, Professional Take-Home Teeth Whitening Kit

Colgate Optic White Light Up 10% Hydrogen Peroxide Dentist Exclusive, Professional in-chair Whitening Kit

Colgate Optic White Light Up 6% Hydrogen Peroxide Dentist

Exclusive, Professional Take-Home Whitening Refill Pen: A Professional Teeth Whitening Pen exclusive to dentists. Whitening Serum Pen containing 6% hydrogen peroxide, for dramatically whiter teeth in 10 minutes a day for 10 days*.

*Use as directed. Use with Optic White Professional LED Teeth Whitening Device

Colgate Optic White Light Up 6% Hydrogen Peroxide Dentist Exclusive, Professional Take-Home Whitening Refill Pen

22 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

ADVERTORIAL

Anterior case with Clearfil Majesty™

ES-2 Premium

Case Background

A healthy systemically ASA I classified 30-year-old male presented to my service for esthetic options relative to tooth 2.1. This tooth had been impacted in a bike accident at 16 years of age in South Africa, where the individual high-sided and traumatized the tooth. Since then, it has progressed through specialist endodontist intervention 7 years prior.

Soft tissue clinical examination revealed a band of localized moderate marginal erythema affecting his upper anterior sextant, with no periodontal pockets of significance, with the likely etiology mouth breathing, for which nasal breathing was reinforced. Clinical dental examination revealed tooth 2.1 with significantly lower value than the contralateral teeth with visible margins of the old acid-etched bonded composite restoration on the MIDBP surfaces. There was an oblique crack affecting the distal marginal ridge extending centro-obliquely. A small enamel fracture was noted on the 11MI angle also. Radiographic examination revealed no apical rarefying osteitis and no caries affecting the teeth in view, however the distal marginal ridge incomplete fracture was visible and extended to a cervical level possibly violating the biologic width.

Restorative Procedure

Internal bleaching was discussed with the patient as a structure-conservative first option for lifting the chroma and value especially in the cervical aspect where the enamel volume is the thinnest and can range from less than 0.3-0.5mm6

The risks inherent to this procedure involve a 15.1% lifetime risk of External Cervical Resorption (ECR) and with internal bleaching an increased risk to 10.6% of teeth involved.1

The patient was anesthetized with 1.5 carpules of 2% Lignocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine via buccal and lingual infiltration as possible biologic width violation was possible as dissecting out the fracture line to recreate a well-bonded periphery for hermetic enclosure of the walking bleach. Rubber dam isolation was achieved initially but abandoned as the fracture line descended to a significant subgingival level distogingivally and thus required surgical access to be dissected out in its entirety.

USER

24 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Clarence Tam1

REPORT

1 Clarence Tam HBSc, DDS, FIADFE, AAACD Auckland, New Zealand

seconds before again blot dried to a moist dentin state before application of a single step 10-MDP-based selfetching adhesive, CLEARFIL™ UNIVERSAL BOND Quick.

Without waiting time after the application, the bond layer was air thinned and carrier evaporated before curing using a 2000mW/cm2 polywave curing light unit (Pencure 2000, J.Morita Corporation).

A pre-crimped Mylar matrix strip was placed to guide the freehand placement of the lingual shelf, a 0.3mm thick layer composed purely of A1E Enamel (CLEARFIL MAJESTY™ ES-2 Premium). Following this, the join line was occluded using two successive layers of shade of A1D Dentin (CLEARFIL MAJESTY™ ES-2 Premium) and the dentin mamelon incisal details characterized using a dental instrument.

Next, Blue Translucent effects were placed (CLEARFIL MAJESTY™ ES-2 Premium) on the proximoincisal corners to accentuate the opalescence of the enamel and a Trans shade was applied to the mid-incisal area. White tint was used to characterize the tips of the dentin mamelons before a final layer of A1E Enamel was sculpted to final form in preparation for finishing and polishing procedures.

Primary anatomy was completed focusing on incisal embrasures, cervical embrasures and line angles. Secondary anatomy characterized facial anatomy and lobe detail.

Final reassessment of the case shows excellent optical and functional integration of an esthetically complex case that would have been an equa challenge for an indirect approach however with greater reduction of tooth structure.

Rationale for Material Choice

An indirect approach using laminate porcelain restorations would have necessitated the removal of a minimal of 0.3mm of enamel cervically, which often is the maximal volume of the rigid enamel shell in the cervical third of upper anterior teeth1

This acts to compound negatively with the reduced flexural strength of a tooth that not only has previously been endodontically-treated but features existing palato-oblique fractures. Preservation of a maximal volume of tooth structure is key to preserving a maximal long-term prognosis.

Part of the preservation effort is not only macroscopic, but importantly on a microscopic level. By limiting the phosphoric acid etch’s effect on dentin and especially deep dentin, there is a maximal volume of hydroxyapatite crystal volume

remaining, which not only bolsters residual flexural strength but allows both super dentin and super enamel development through use of a 10-MDP-based acidic monomer, which has the ability to nanolayer calcium in pattern creating phenotypically a very acid-base-resistant layer, measuring 1000-1200nm in thickness.3, 4 The adhesive selected contains a novel amide monomer, which also increases both hydrophilicity and penetration potential relative to HEMA but is more resistant to hydrolytic degradation.2

CLEARFIL MAJESTY™ ES-2 Premium is the only VITA approved shade (VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Sackingen, Germany) composite system in the world. It features a buttery, no-slump, non-sticky consistency which is a remarkable benefit for universal applications but especially sculpted direct anterior cases. It features an excellent optical refraction index very similar to tooth structure.

Often, the filler to resin matrix in anterior composites leaves the composite sticky, with the subsequent need to use wetting resin (bis-GMA, TEGDMA) to handle the material, which can often dilute the intended chemistry and affect ultimate performance if not used sparingly.

CLEARFIL MAJESTY™ ES-2 Premium features a very unique Light Diffusion Technology (LDT) which allows applications in thinner layers to achieve the same degree of optical refraction as in other composite systems.

This translates to need for less tooth preparation, which is ideal from a responsible esthetics standpoint. With 15 shades in total, it is a slick and tech-smart armamentarium that will be able to tackle any challenge head on in your minimally-invasive daily practice.

References

1. Heithersay GS. Invasive cervical resorption following trauma. Aust Endod J. 1999 Aug;25(2):79-85. doi: 10.1111/ j.1747-4477.1999.tb00094.x. PMID: 11411085.

2. Kuno Y, Hosaka K, Nakajima M, Ikeda M, Klein Junior CA, Foxton RM, Tagami J. Incorporation of a hydrophilic amide monomer into a one-step self-etch adhesive to increase dentin bond strength: Effect of application time. Dent Mater J. 2019 Dec 1;38(6):892-899. doi: 10.4012/ dmj.2018-286. Epub 2019 Aug 1. PMID: 31366768.

3. Nikaido T, Takagaki T, Sato T, Burrow MF, Tagami J. The concept of super enamel formation -Relationship between

TAM

26 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

chemical interaction and enamel acid-base resistant zone at the self-etch adhesive/enamel interface. Dent Mater J. 2020 Aug 2;39(4):534-538. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2020-165. Epub 2020 Jul 4. PMID: 32624553.

4. Nikaido, T., Takagaki, T., Sato, T., Burrow, M. F., & Tagami, J.(2021). Fluoride-Releasing Self-Etch Adhesives Create Thick ABRZ at the Interface. BioMed research international, 2021, 9731280. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9731280

5. Topcu, F. T., Erdemir, U., Ozel, E., Tiryaki, M., Oktay, E. A., & Yildiz, E. (2017). Influence of Bleaching Regimen

and Time Elapsed on Microtensile Bond Strength of Resin Composite to Enamel. Contemporary clinical dentistry, 8(3), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.4103/ccd.ccd_234_17

6. Yu H, Zhao Y, Li J, Luo T, Gao J, Liu H, Liu W, Liu F, Zhao K, Liu F, Ma C, Setz JM, Liang S, Fan L, Gao S, Zhu Z, Shen J, Wang J, Zhu Z, Zhou X. Minimal invasive microscopic tooth preparation in esthetic restoration: a specialist consensus. Int J Oral Sci. 2019 Oct 2;11(3):31. doi: 10.1038/s41368-019-0057-y. PMID: 31575850; PMCID: PMC6802612.

TAM

Simple chords of shades for harmonious restorations

Wallid Boujemaa1

Composite restorations set the rhythm of the daily life of our dental practices. Whether they are the final goal of a rehabilitation or an intermediate stage of the treatment plan, their implementation must be easy and reproducible. In anterior areas, the shape, colour and occlusal condition must be rigorously studied to achieve the desired aesthetic and functional requirements. In terms of posterior teeth, direct restorations will have to fulfill two major goals, biological and functional. While aesthetics are not to be left behind, respect for cusp morphology will certainly be of greater importance.

For more than a decade, composite resins have been used to fulfill these specifications. Their simplicity of application, their mechanical resistance, their polishing abilities and their optical properties allow them to integrate perfectly with natural tissues over time. Among these materials, GC’s G-ænial range has proven itself for 10 years. Its youngest member G-ænial A’CHORD, has just been born and seems as promising as the former version. With a smaller number of shades, it can cover the same situations as its predecessor, with a markedly improved consistency and surface condition after polishing. The two cases presented here are examples of the possible applications of this material in a successful way.

Case 1: Anterior restorations using monochromatic & multi-shade techniques

A 40-year-old patient, in good general health, attended an emergency consultation. She had fallen on her coffee table, which caused a fracture from the mesial angle up to the middle third of tooth 21. The tooth responded positively to the pulp sensitivity test. Given the colour and textural characterisations to be reproduced, a stratification session was scheduled. The patient also wanted to improve the aesthetics of her smile by having the apparent black triangles between teeth 21 and 22 reduced. An impression for wax-up and a temporary restoration using a composite in single-mass technique are carried out during the emergency consultation. Periodontal remediation and endodontic treatment of the 11, which was necrotized following the trauma, were performed prior to the composite stratification session.

CLINICAL 28 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1

1 Wallid Boujemaa Lecturer, University of Bordeaux. Private practice, Ondres, France

CLINICAL INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 29

3

Fig. 3: Initial retro-alveolar X-ray.

4 5

Fig. 4 and 5: Shade selection using the composite button technique, with and without polarizing filters.

6 7 8

Fig. 6: The wax-up allowing the creation of a palatal silicone key.

Fig. 7: Teeth isolation with a rubber dam Fig. 8: Enamel etching using 37% orthophosphoric acid for 10 seconds.

9 10 11

Fig. 9: Application of G-Premio BOND universal adhesive(GC).

Fig. 10 and 11: Creation of the palatal enamel shell using the Junior Enamel shade JE (G-ænial A’CHORD, GC).

1 2

Fig. 1 and 2: Initial situation.

BOUJEMAA 30 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1

15 16 17

Fig. 15: Modeling of dentin mamelons using the A2 shade (G-ænial A’CHORD).

Fig. 16: Application of superficial enamel, shade JE.

Fig. 17: The distal cavity is blocked with a CORE shade of medium opacity A2.

18 19 20

Fig. 18: Use of a impregnated with an unfilled resin (Modeling Liquid, GC) brush making it easier to sculpt and adjust the composite.

Fig. 19: Macro-anatomy management with a red flame bur.

Fig. 20: Pre-polishing with the pink silicone disc Diacomp TwistPlus® (EVE).

21 22

Fig. 21: Polishing with a beige silicone disc Diacomp TwistPlus® (EVE).

Fig. 22: Surface condition after finishing and polishing.

12 13 14

Fig. 12 and 13: Elaboration of the mesial surface with an enamel shade using a proximal matrix (LumiContrast® Polydentia).

Fig. 14: Modeling of the dentin core in opaque dentine shade AO2 (G-ænial A’CHORD GC).

BOUJEMAA 32 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1

23 24 25

Fig. 23 and 24: Reduction of the black triangle with a shade of medium opacity A2.

26 27 28

Fig. 25: Immediate post-operative situation.

29 30

Fig. 26: Post-operative X-ray.

31 32

Fig. 27 to 32: Post-operative situation at one week.

A 15-year-old patient, in general good health, presented herself for a check-up. She reported localised sensitivity to

sweet on tooth 36. The tooth responded positively to the pulp sensitivity test, and displayed an occlusal composite without morphology. Clinical and radiographic examinations revealed the presence of secondary caries under the composite,

BOUJEMAA INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 33

Case 2: Posterior restoration using a cusp by cusp approach

1

Fig. 1: Initial situation.

3 4

Fig. 2: Pre-operative retroalveolar X-ray.

Fig. 3: Isolation of the tooth under rubber dam.

Fig. 4: Composite removal.

5 6 7

Fig. 5: The caries removal is carried out in a centripetal way.

Fig. 6: Etching using 37% ortho phosphoric acid for 10 seconds. This is eliminated with an abundant rinse.

Fig. 7: Application of G-Premio BOND® (GC) universal bonding. This is applied and rubbed vigorously on dental surfaces, then dried strongly before light-curing.

8 9 10 11

Fig. 8 and 9: Application of a 2-mm composite layer on the surface of the cavity, using an injectable composite (G-ænial Universal Injectable® A2, GC).

2

Fig. 10-11: G-ænial A’CHORD composite® A2 (GC) is easily shaped to create the cusps.

which showed micro-leakage at the margins. A session was scheduled to remove the composite and determine if a simple renewal of the composite with a direct technique was possible. At this stage, the cavity was disinfected with 2% chlorhexidine solution to reduce the bacterial load during caries removal, which could have lead to pulp exposure. After cleaning, the

cavity was shaped. The pulpal wall appeared to be located away from the pulp chamber (0.5 mm). The thickness of the remaining walls enabled us to opt for a direct composite restoration.

Reprinted with permission from GC get connected

BOUJEMAA 34 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1

12 13 14 15

Fig. 12-13: The other cusps are built cusp-by-cusp in the same manner, creating the occlusal anatomy.

Fig. 14: The use of a composite stain (Brown Modifier®, Essentia Modifier Kit, GC) makes it possible to assess the morphology and ensure that there are no gaps.

Fig. 15: 40-second photopolymerization on each side under glycerin gel (AirBarrier® GC).

16 17 18

Fig. 16 and 17: Polishing with silicon wheels (Soft Lex®3M).

Fig. 18: Immediate post-operative situation under rubber dam.

20 21

Fig. 19: Post-operative retroalveolar X-ray.

Fig. 21: Post-operative situation at one month. Sensitivities are gone.

19

Fig. 20: Immediate postoperative situation.

Management of stained fluorotic teeth

Meenakshi Lall1

Introduction

Dental fluorosis is a condition that affects the enamel, caused by overexposure to fluoride during tooth formation. Recommended intake of fluoride for primary prevention of caries is reported to be 0.05-0.07mgF/Kg/day (Warren, Levy and Kanellis, 2001). When the concentration is more than 1.5-4mg/L, as the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends, dental fluorosis occurs. Hypermineralised and hypomineralised areas appear in the enamel that is being formed, resulting in whitish opaque discolourations ranging from yellow to brown with or without porosities in the enamel surface (Pendrys and Stamm, 1990; Celik, Yildiz and Yazkan, 2013).

Fluorosis staining of anterior teeth constitutes an aesthetic problem among affected people. In addition, it has been found to have a psychological impact and adverse impact on academic performance. Thus, conservative aesthetic management of dental fluorosis not only improves smiles but also greatly enhances the self-esteem of the affected individuals.

Contemporary aesthetic procedures allow these teeth to be restored to give them the appearance of healthy teeth in the most minimalistic invasive manner.

This case report aims to highlight a three-treatment combination for aesthetic correction of severe fluorotic teeth. It also discusses the advantages, drawbacks of various treatment choices and apprise the clinician of the appropriate aesthetic conservative management protocol for dental fluorosis with diverse clinical appearance.

Case study

A 43-year-old female patient attended the practice concerned with the aesthetics of her teeth. She had a complaint of chipping, which had been repaired by different dentists.

The patient reported that the teeth had been discoloured for many years. She was unable to recollect when they first started to discolour, but reported that the discolouration had increased over time.

The patient reported no pain or discomfort and she was not aware that she had severe fluorosis. We used Thylstrup-Fejerskov (TF) index for scoring fluorosis. Intraoral examination revealed brownish discolouration of enamel with all maxillary and mandibular incisors, canines and premolars.

The pattern of discolouration was bilateral and symmetrical. The surfaces of some of these teeth were pitted.

Discolouration was more prominent on maxillary teeth compared to mandibular

CLINICAL 36 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

1 Meenakshi Lall BDS MSC MFDS AD EUNDEM RCS (ENG)

Associate dentist in Stourcote Dental Practice, Private Practice iStourbridge, UK.

teeth (Figure 1).

Pulp sensibility testing of the discoloured teeth was carried out using cold test and electric pulp testing, which indicated normal pulp with all these teeth.

The medical history was non-contributory.

Treatment planning process

In the past, enamel microabrasion and vital bleaching were the preferred treatment for mildly or moderately fluorosed teeth without enamel defects, (Price et al, 2003; Limeback, Vieira and Lawrence, 2006). While fluorosed teeth with enamel defects or severe fluorosis were traditionally restored with laminate veneers or crowns (Habbu et al, 2011; AlJazairy, 2001).

However, the more recent trend is toward minimal intervention dentistry. Since restorative intervention is often the starting point of a long series of re-restorations, commonly leading to crowns and implants, irrespective of how well the first restoration was prepared, minimally invasive techniques (enamel microabrasion and vital bleaching) may be the first option, even though the more traditional restorative techniques result in a satisfactory aesthetic appearance for many patients.

Several treatment strategies are proposed for dental fluorosis, depending on the severity and extent of the disease.

The most frequently reported are microabrasion and/or macroabrasion, dental bleaching, composite restorations, veneers, and prosthetic crowns.

Resin infiltration has also shown promising results. This approach meets the concept of minimally invasive restorative dentistry and allows us to reach satisfying results avoiding unnecessary tissue removal.

Procedure

In this case, complexities and challenges presented throughout treatment.

The patient was not aware of her fluorosis. However, thorough discussion of her social history helped me to diagnose her condition (Tahir and Rasheed, 2013).

The patient was a heavy smoker and consumed a lot of fizzy drinks. These factors would negatively impact the outcome of the treatment. It was important that the patient understood this, so we shared photographic/comparative results, which helped gain her compliance and achieve positive change.

For this case, since the restorative intervention is a starting point of long series of re-restoration, we opted for minimal invasive procedures and the patient was warned about the possible compromised results.

We began treatment with a five-week course of home-

CLINICAL INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 37

Figure 1: Initial situation. According to the TF index score, the maxillary and mandibular teeth were classed as ‘severe’

Figure 2: Mapping (pink = Icon; green = Venus Pearl)

Figures 3A, 3B and 3C: Shade taking Venus Pearl and Diamond composite

based tooth whitening with 10% carbamide peroxide and a cycle of microabrasion (Figures 4b and 4d). In the future, I will opt for a longer bleaching regime for better results.

A fine grit diamond bur helped in removing darker stains and smoothing of enamel loss. After two weeks microabrasion with 6.6% hydrochloric acid (Opalustre), we saw a lightening of the brown stains (Figure 4c).

We performed the microabrasion according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Rubber dam was applied, and gingival margins sealed with Oraseal Caulking material. The slurry was applied in 1-3mm thickness on the upper front teeth for 60 seconds using rubber prophy cups (Opalcups). The teeth were rinsed with water.

A study by Ahmed and Murbay (2016) found that 120 seconds of microabrasive treatment reduces approximately 10% (200µm) of the enamel thickness.

It helps to remove discoloured enamel and change

enamel optical characteristics, turning it into a lustrous, shiny and glass-like surface, which may reflect and refract light.

Composite shade matching also presented a challenge, as the patient had different values and chroma of teeth. Moreover, the patient’s enamel has less translucency.

I used Venus Pearl composite A1 shade in interproximal, buccal and incisal areas and A2 shade in cervical areas, since it was the nearest match and has good aesthetic quality (Figure 3).

All old, stained composite fillings were removed. Resin infiltration (Icon) and change of old composite was performed according to manufacturer instructions.

Bonding to composite after resin infiltration does not require an additional adhesive step. If, after the infiltrant final light-curing, there is no contamination of the operatory field, composite increments may be directly applied onto the infiltrated surfaces. The depth of resin infiltration is about 60µm (Davila

LALL

38 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

et al, 1975) (Figures 5a to 5c).

Figure 4A: White opaque areas, brown discolouration with surface porosities on enamel

Figure 4B: Two-week home-based bleaching with 10% carbamide peroxide for six to eight hours at night

Figure 4C: Microabrasion with Opalustre 6.6% HCL

Figure 4D: Three-week home-based bleaching with 10% carbamide peroxide for six to eight hours at night

Figure 4E: Icon smooth surface and composite restorations

Figure 4F: Occlusion adjusted (especially UL3) and finishing

Figures 5A, 5B and 5C: Old composite filling removed Icon infiltration

Occlusion was managed through silicone putty, as the anterior guidance was likely to change in the treatment process. In cases non-responsive to resin infiltration, this treatment shows a very good example of resin infiltration and composite resin option for the cases of enamel defects and severe fluorosis. This opens the possibilities that aim for a highly aesthetic outcome with a minimally invasive approach.

Treatment stages

Pre-treatment

Figure 4a shows the pre-treatment presentation with white opaque areas, and brown discolouration with surface porosities on the enamel.

Home-based bleaching

Two-week home-based bleaching with 10% carbamide peroxide (Boutique) was carried out for six to eight hours at night. Notice the minimal changes in brown discolouration (Figure 4b).

Microabrasion

We then performed one cycle of microabrasion with Opalustre (6.6% hydrochloric acid). This resulted in a nonhomogenous colour, and thinner enamel (Figure 4c).

Home-based bleaching

Vital home-based bleaching with 10% carbamide peroxide (Pola Night) was undertaken for six to eight hours a night for three weeks to remove brown discolouration, and lighten adjacent enamel to change perception of white opaque areas. This created a homogenous colour of teeth surface (Figure 4d).

Icon smooth surface and composite restorations

One week after Icon and composite restorations (Figure 4e), the occlusion was adjusted (especially UL3) and finished (Figure 4f).

Icon resin infiltration

The old composite filling was removed with a coarse diamond bur. An LED UV torch was used to distinguish between old composite and tooth surface. Next, the following steps using Icon infiltration were undertaken:

•Etch for two minutes, rub with a microbrush and rinse for 30 seconds. Dentine is protected with application of glycerine (Figure 5a)

•Icon-Dry. Let it sit for 30 seconds and thereby carry out visual inspection, dry with oil- and water-free air. If white patch disappears, do not repeat etch cycle. However, if white patch is visible then repeat etch cycle. The etch cycle can be repeated three times. The preview showed an even chromaticity (Figure 5b)

•Apply Icon-Infiltrant. Let it sit for three minutes, maintain wet lesion surface with occasional twist of syringe. Disperse with air, and floss. Light-cure for 40 seconds. Replace applicator tip. Apply Icon-Infiltrant, let it sit for one minute. Remove excess and floss. Light-cure for 40 seconds and polish. According to studies, Icon can penetrate to depth of 60 micrometre (Skucha-Nowak, 2015)

•Polish with Compoglaze (Figure 6).

Reflection

Figures 7a to 7f demonstrate the various treatment stages of this case.

Overall, the patient was pleasantly surprised with the outcome (Figure 7f), reporting that the treatment has helped her to gain social confidence. As the treating clinician, I am also satisfied with the result.

Although the patient accepted the least invasive approach to manage her upper arch for UR4 to UL4, she declined treatment for the lower arch.

Also, at the follow-up appointment, after Icon and composite fillings, the patient felt high points on UR3 and UL3. While achieving her comfort, the anatomy of her canines was compromised.

In relation to the patient’s oral health benefits, the least invasive approach to manage UR4 to UL4 enabled retention of her natural teeth structure.

The pits and fracture lines have been covered and strengthened through removal of the fluorosed surface via microabrasion and application of Icon and composite.

Also, during the microabrasion and whitening stages of treatment, the patient stopped smoking and vaping completely.

LALL 40 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Figure 6: Polishing

As a result of this treatment, the patient is now more likely to remain motivated for maintaining her oral hygiene, reducing early onset of staining and caries.

Aesthetically, the impact of fluorosis has been overcome through the process of bleaching, microabrasion and Icon.

Furthermore, fracture lines, pits and caries have been covered using Icon and matching composites. This process has provided a homogeneous colour to her teeth. There is an evenness of the enamel edges of UR4 to UL4, thereby improving the patient’s smile line.

To maintain the outcome achieved, the patient needs to keep good oral hygiene. She will have to attend regular appointments with the dentist and dental hygienist and will also need an annual appointment to manage risk/impact of composite staining and chipping.

In addition, the patient was encouraged to significantly reduce or cease consuming fizzy drinks as well as remaining committed to the smoking and vape cessation.

For this case, there is a good prognosis of five to seven years (Bårdsen, 1999), provided oral health instruction is followed, along with routine dental appointments as stated above.

The restorations completed for this patient can lead to a variety of complications, including:

• General fracturing or fracture through grinding

• Cervical abrasion

• Staining of composite.

Nonetheless, poor diet, excessive fizzy drink consumption, poor oral hygiene (including poor toothbrushing) and grinding are likely to act as modes of failure for her

LALL INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL. 18, NO. 1 41

Figure 7A: Pre-treatment

Figure 7B: Two-week whitening

Figure 7C: One cycle of microabrasion

Figure 7D: Three-week whitening

Figure 7E: Resin infiltration and composite resinFigure 7F: After one-week

restorations. Therefore, this treatment requires continuous maintenance from both the dentist as well as the patient.

References

Ahmed KE, Murbay S (2016) Survival rates of anterior composites in managing tooth wear: systematic review. J Oral Rehabil 43(2): 145-53

Al-Jazairy Y (2001) Management of fluorosed teeth using porcelain laminate veneers: A six-year recall case report. Saudi Dent J 13: 106-11

Bårdsen A (1999) ‘Risk periods’ associated with the development of dental fluorosis in maxillary permanent central incisors: a meta-analysis. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 57(5): 247-56

Celik EU, Yildiz G, Yazkan B (2013) Clinical evaluation of enamel microabrasion for the aesthetic management of mildto-severe dental fluorosis [clinical trial]. J Esthet Rest Dent 25(6): 422-430

Davila JM, Buonocore MG, Greeley CB, Provenza DV (1975) Adhesive penetration in human artificial and natural white spots. J Dent Res 54(5): 999-1008

Habbu N, Joshi N, Ramamoorthi M, Mabrukar V (2011) Esthetic management of dental fluorosis. Int J Dent Clin 3(2): 80-1

Limeback H, Vieira AP, Lawrence H (2006) Improving

esthetically objectionable human enamel fluorosis with a simple microabrasion technique. Eur J Oral Sci 114(Suppl 1): 123-126

Pendrys DG, Stamm JW (1990) Relationship of total fluoride intake to beneficial effects and enamel fluorosis. J Dent Res 69: 529-538

Price RB, Loney RW, Doyle MG, Moulding MB (2003) An evaluation of a technique to remove stains from teeth using microabrasion. J Am Dent Assoc 134(8): 1066-71

Rodrigues MC, Mondelli RF, Oliveira GU, Franco EB, Baseggio W, Wang L (2013) Minimal alterations on the enamel surface by micro-abrasion: in vitro roughness and wear assessments. J Appl Oral Sci 21(2): 112-117

Skucha-Nowak M (2015) Attempt to assess the infiltration of enamel made with experimental preparation using a scanning electron microscope. Open Med (Wars) 10(1): 238-248

Tahir MA, Rasheed H (2013) Fluoride in the drinking water of Pakistan and the possible risk of crippling fluorosis. Drink Water Eng Sci 6(1): 17-23

Warren JJ, Levy SM, Kanellis MJ (2001) Prevalence of dental fluorosis in primary dentition. J Public Health Dent 61(2): 87-91

This article first appeared in Clinical Dentistry and has been reprinted with permission. Lall M (2023) Management of stained fluorotic teeth. Clinical Dentistry 3(3): 33-36

LALL

42 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

ENTER A NEW ERA OF MILLING

The innovative milling machine for digital dental technology in the practice lab and laboratory. Optimise your digital workflow, enjoy maximum freedom and achieve perfect results with optimum efficiency.

• 5 Axis

• 1 Disc

• 6 Blocks

• 17 Tools

• Dry Mill

• No compressed air needed

• For Composites, Zirconia, PMMA, CoCr

WATCH VIDEO

E5

1300 65 88 22 henry schein.com.au

Masterclass in Clinical Practice

Implant Dentistry with

Dr

Vladimir S Todorovic1

Dr Inus Snyman2

Dr Andre W van Zyl3

Lateral window Sinus Floor Elevation technique

Introduction

Insufficient bone below the maxillary sinuses in the posterior maxilla is a common finding in dental implant treatment. Reasons for loss of available bone in the posterior maxilla can be from traumatic extractions, pneumatisized sinuses and loss of alveolar bone due to periodontitis.

Over the past five decades sinus floor elevation procedures to increase this available bone have evolved from being an extreme procedure performed by a select few specialists, to a reliable procedure being performed daily by specialists and experienced dentists alike.

The original procedure to establish bone within the sinus floor for implant placement was described and published by Boyne and James as well as Tatum.1,2 Since then it has been refined and made easier by the introduction of specialized instruments and grafting materials.

It must be stressed though that sinus floor elevation (SFE) procedures should only be done by clinicians with surgical training as well as experience in performing these procedures. Knowledge of the sinus anatomy, nerve and arterial supply as well as using CBCT technology is essential in performing successful SFE procedures. The reader is referred to our Masterclass in International Dentistry - African Edition, Vol 12 No 6, Maxillary Sinus Anatomy: Essential knowledge for sinus floor elevation (SFE).3

One stage versus two stage placement protocol

Scan to see video

1 Vladimir S Todorovic, PhD

Research Associate, School of Dental Medicine, University of Belgrade, Serbia

Private practice, Belgrade, Serbia

2 Inus Snyman

BChD, PDD (Implantology), PGDipDent (Oral Surgery), PGDipDent (Implantology), MChD, FCD(SA) OMP

Private Practice, Stellenbosch, South Africa

3 Andre W. van Zyl

MChD (Oral Medicine & Periodontics)

Private Practice, Hermanus, South Africa

Today’s patients demand surgical procedures with less trauma, shorter treatment time and possibly without compromising the success rate. Having this in mind, a one stage (simultaneous) approach would be a preferred one (see video). The procedure implies that both sinus floor elevation and implant placement is done during the same session. It can be considered only if the primary implant stability is achievable. It is well known that primary implant stability is influenced by several factors – residual alveolar ridge dimensions, bone quality (density), implant macro-design and the site preparation technique. However, sufficient sub-antral residual alveolar ridge height is the most important criterion and the threshold of ≥5 mm was traditionally declared for considering a simultaneous implant placement (ITI Treatment Guide, Volume 5). However, implant success has been reported in residual alveolar bone height as low as 3 mm.4,5 Also, we are aware that quality of bone in the posterior maxilla is poor and might be enhanced by certain techniques, such as bone condensing, either by application of osteotomes or under-preparation of implant sites. Additionally, primary implant stability could be improved by using tapered macro-designed implants.

Whenever it is anticipated that adequate primary implant stability cannot be attained, a decision for staged approach should be made. Depending on the maxillary sinus anatomy, extent of augmentation and choice of grafting material, the healing period can vary from 3 – 12 months. For single-tooth gaps with favourable narrow sinus anatomy and predominantly autologous bone graft using a 3–4 months healing time should be sufficient. In cases with so-called “eggshell” sinus floor, augmented with bone substitute only, a total healing period of 9-12 months is needed before implant installation.

44 INTERNATIONAL DENTISTRY AUSTRALASIAN EDITION VOL.18, NO. 1

Figure 5: The groove is checked easily with a light scraping of a periodontal probe which will identify where the bone is not yet fully removed. Light pressure on the central bone disc will also show movement inward if bone is fully prepared (see video)

Figure 3: Instead of drilling bone away, harvesting over the site of window is done with a bone scraper. This creates a large surface to volume bone graft that can be mixed with the bone filler