The promise of Waitangi to the world

TASTE MAKERS

Continuing a winemaking legacy WITH PRIDE Rainbow histories enter the List MARKING TIME When does graffiti become ‘heritage’?

The promise of Waitangi to the world

Continuing a winemaking legacy WITH PRIDE Rainbow histories enter the List MARKING TIME When does graffiti become ‘heritage’?

12 Origin story

How a Kiwi archaeologist helped unearth the secrets of Stonehenge

16 Taste makers

Award-winning wines are still being produced from the home of a winemaking pioneer

22 Keeping the faith

What’s new in the ongoing struggle to retain our historic churches?

30 Dream big

We visit a Nelson heritage restoration of epic proportions

34 The ongoing promise

Two kaitiaki reflect on their connections to the Waitangi National Trust estate

40 With pride

Recognising the queer histories of our historic places

8 Planting a legacy

The mana of Whakaotirangi, experimental gardener and scientist, continues to resonate

10 Captured in time

In Waiuta, tantalising clues to a once-thriving past remain

into the past

44 When in Waiuta

Tips for planning a visit to this historic West Coast former goldmining town

46 Leaving your mark

At what point does graffiti become ‘heritage’?

Reads reflecting our changing times

54 Our heritage, my vision

Jacqueline Leckie, on making our ‘invisible histories’ visible

As this magazine lands in your letterbox, you may be planning your big Kiwi summer road trip.

If that’s the case, make sure you take your Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga membership card with you. There are lots of places to visit and you are entitled to FREE entry with your membership card.

Actively visiting these places and introducing friends and family to them keeps them alive and loved.

And now there's a great new resource for you to discover heritage places to visit, stay and explore. It includes some fantastic itineraries and tours, plus much more.

Go to www.visitheritage.co.nz to start your journey.

NG Ā MIHI | THANK YOU

We are very grateful to all those supporters who have recently made donations. While many are kindly acknowledged below, more have chosen to give anonymously.

Mr Des and Mrs Yukito Hunt

Mr Colin and Mrs Barbara Hickling

Mr David and Mrs Dorothy Hinman

Miss Gaye Matthews

Mr S J and Mrs Pam Sedgley

Mr David Barlass and Mrs Julie Barlass

Dr David and Lesley Going

Mrs Frances Bell

Raumati • Summer 2021

Mr Alistair Aitken and Shona Smith

Mrs Alison Oertly

Mr Ian and Mrs Jenny Thomas

Mr David and Mrs Marilyn Ayers

Ms Elaine Hampton and Michael Hartley

Mr Francis and Mrs Annette Piggin

Mr Peter and Mrs Val Osborne

Mr Ross Twiname

Rosa-Jane French

Mr Peter and Mrs Betty Lamont

Mr Wayne Highet and Dale Morgan

Mr Cameron Moore

Mr John and Mrs Caroline Chapman

Dr John and Dr Anna Holmes

Mr Edmund and Mrs Catherine Brown

Miss Wendy Stuart

Mrs Beverley Eriksen

Lady Barbara Stewart

Mr Arnold and Mrs Marjorie Turner

Mr Jeff Downs

Mrs Avis Foote

Mrs Eleanor and Mrs E J Leckie

Heritage

Issue 163 Raumati • Summer 2021

ISSN 1175-9615 (Print)

ISSN 2253-5330 (Online)

Cover image: Nga wai hono i te po Paki by Erica Sinclair

Editor

Caitlin Sykes, Sugar Bag Publishing

Sub-editor

Trish Heketa, Sugar Bag Publishing

Art director

Amanda Trayes, Sugar Bag Publishing

Publisher

Heritage New Zealand magazine is published quarterly by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. The magazine had a circulation of 9,906 as at 30 June 2021.

The views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Advertising For advertising enquiries, please contact the Manager Publications.

Phone: (04) 470 8054

Email: advertising@heritage.org.nz

Subscriptions/Membership

Heritage New Zealand magazine is sent to all members of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. Call 0800 802 010 to find out more.

At Heritage New Zealand magazine we enjoy feedback about any of the articles in this issue or heritage-related matters.

Email: The Editor at heritagenz@gmail.com

Post: The Editor, c/- Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140

Feature articles: Note that articles are usually commissioned, so please contact the Editor for guidance regarding a story proposal before proceeding. All manuscripts accepted for publication in Heritage New Zealand magazine are subject to editing at the discretion of the Editor and Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Online: Subscription and advertising details can be found under the Resources section on the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga website www.heritage.org.nz

One of the most interesting aspects of heritage, to me, is the way it’s always changing and our perspectives on it are evolving.

That there’s always a currency, a new way to look at different aspects of the heritage world, is something that struck me when writing the profile in this issue of Andrew Brown.

While living and studying in the UK, the New Zealand archaeologist worked a number of stints on the Stones of Stonehenge Project.

Investigating the origins of the structure, which is sited on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, the project focused on its bluestones, which were quarried 230 kilometres away in Wales.

It’s one of the world’s most famed ancient monuments, and I think a sense of permanence is what shapes a large part of Stonehenge’s identity in many people’s minds.

However, the multi-year, multi-disciplinary project found evidence to support the theory that the stones were part of an earlier monument erected much closer to their source, and later disassembled and re-erected in Wiltshire.

“It was remodelled a number of times and the bluestones were always a part of it,” says Andy, in the story.

“When you start engaging with Stonehenge in that way, you see it much more as a living, changing monument.”

Margo White’s story on page 46 highlights how intent, content and authorship, as well as historic context and age, can all shape our perspectives on graffiti left at heritage places.

One of the areas explored in the story is the tradition of tradespeople leaving their marks hidden in buildings when undertaking work.

One such example is at Old St Paul’s in Wellington, where the names of not only the original carpenter, John McLaggan, and his team, but also those more recently involved with the church, are to be found

within its walls. In 2019 to 2020, while laying new foundations as part of earthquake strengthening work, the builders signed their names in the concrete.

“I wouldn’t encourage everyone who works on a building to leave a mark,” notes Tamara Patten, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Property Lead, Old St Paul’s, in the piece.

“But one of the things that makes working in heritage so wonderful is finding and telling the stories of people connected to a place, and this is a really nice story.”

Changes are also being made to the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero as part of the Rainbow List Project, featured in our story on page 40.

The project aims to recognise sites of significance to New Zealand’s queer communities that have previously gone unrecognised because of longstanding legal and social prejudices.

One of the listings so far updated is Wellington’s Thistle Inn – the setting for the thinly disguised romantic lesbian encounter described in the Katherine Mansfield story Leves Amores, which has long been known to scholars of queer histories. Another is 288 Cuba Street in the city, once home to Carmen’s Curios, owned by the transgender icon Carmen Rupe.

The project is an important opportunity to normalise queer history and ensure the List is diverse.

As Kerryn Pollock, Senior Heritage Assessment Advisor at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, who is leading the project, says, “There really is no excuse for us not to be telling these stories in the 21st century.”

Ngā mihi nui

Caitlin Sykes Editor

Heritage New Zealand magazine prides itself on its good-looking pages. John Bannan, of print firm Blue Star, shares how his role helps the magazine keep looking its best.

How long have you been connected with Heritage New Zealand magazine?

Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga has been a client of mine since 2012. During that time we’ve printed Heritage New Zealand magazine and the majority of the organisation’s brochure and stationery collateral. I handle the day-to-day running of the account and ensure all timings are met, the online ordering site is kept up to date and the print quality of any products produced is of the highest quality.

Blue Star has won a number of awards over the years for its work on Heritage New Zealand magazine. Which of those wins stands out for you?

Pride In Print is like the Academy Awards for the print industry.

It’s the pinnacle event at which print companies can showcase their work, so we’re proud to be considered the benchmark consistently for gold medals and awards won at this event.

The Autumn 2020 issue, for which we won gold at Pride In Print, was especially pleasing. The comments from the judges regarding the expertise shown in ensuring an accurate fit and the perfect match-up of imagery across pages were testament to the calibre of the tradespeople who work on the floor in the plant to create the publication. It's great to be able to tell the team that their workmanship has been rewarded in some way, and it makes us proud knowing that what we’re doing is of the highest quality.

Personally, what's a special heritage place for you?

Easily the Stone Store in Kerikeri. I visited there last summer and the fact that it’s the oldest surviving stone building in New Zealand and is still in such good condition just blows me away. It takes you back to yesteryear and how we used to live. That’s why I think Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, by keeping these important heritage buildings in the public eye, plays such an integral part in the fabric of New Zealand.

Please contact Brendon Veale (below) if you would like to become a supporter.

Brendon Veale Manager Asset Funding 0800 HERITAGE (0800 437482) bveale@heritage.org.nz

Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Marketing Advisor

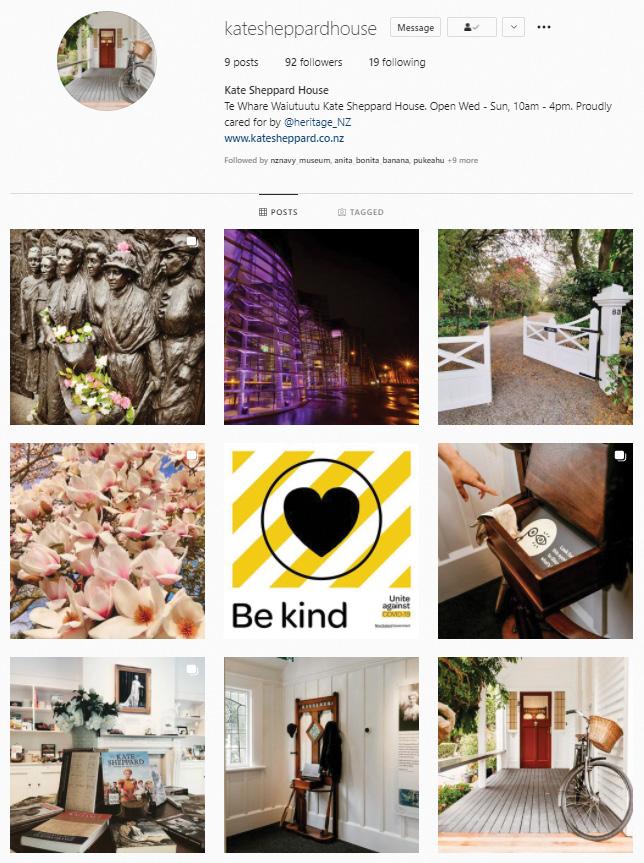

Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga proudly cares for more than 40 properties around the country, which means we need more than just one Facebook or Instagram channel to help us shine a light on our important heritage places online.

Many of the properties we care for have their own social media channels, which enable us to share their unique voices and stories, as well as more of the breadth of work we do as an organisation.

One of these properties is Te Whare Waiutuutu Kate Sheppard House, located in Christchurch. A reasonably new heritage property in the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga portfolio, the house is the former residence of leading New Zealand suffragist Kate Sheppard and her family.

Our social media channels for the house share insights into the life and times of Kate, as well as the regular events held at the house. On 19 September, for example, we celebrated Suffrage Day with an all-day event that included a morning tea at the house and visits to locations of importance to Kate Sheppard around Christchurch.

To ensure you stay up to date with what’s happening at the house and gain sneak peeks of what you can expect during a visit, follow Te Whare Waiutuutu Kate Sheppard House on both Facebook and Instagram:

Facebook: Facebook.com/katesheppardhouse

Instagram: Instagram.com/katesheppardhouse or @katesheppardhouse

For this issue you wrote a story about the massive restoration work in progress at The Gables in Nelson. What appealed to you about taking on the story?

I’m among the many hundreds of locals to have slowed down to look and wonder about The Gables when driving along Waimea West Road. My roots run deep in this region, and having grown up in an 1860s Nelson villa, I’m familiar with both the beauty and the pitfalls – the cold! – of living in these early homes.

I’ve long been fascinated by how the design of this home emerged, and, more recently, why anyone would be brave enough to take on its restoration. So when the chance came along to write about it, and therefore step inside, I didn’t hesitate to say “Yes!”.

What's something new you learned about the place in the course of working on the story?

While I knew it was the original Palmer family home, I didn’t connect that our former prime minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer was a member of the same family, and that he’d been part of earlier attempts to get a salvage effort going.

Also, it occurred to me while reading about how The Gables’ bricks were made, that it was possible an early ancestor of mine was involved. He was a London bricklayer who arrived in 1841 and lived on the Waimea Plains. He died a few years after The Gables was built and is buried in a plot at the nearby historic St Michael’s Church.

You're based in Nelson. What's a local heritage site that you'd recommend people visit, and why?

In terms of built heritage, I adore the quirkiness of Founders Heritage Park. It’s a faux village created from many of our early Nelson buildings shifted to the site, from where traditional artisans now make and sell their wares. The old Nelson Evening Mail Building is now a working museum of antique printing presses used for traditional printmaking.

For natural heritage, Pepin Island, which is the domain of local iwi Ngāti Tama, frequently beckons us. Part of the island was once the pā of the paramount chief of Ngāti Tama, Te Pūoho-o-te-rangi. The island itself is now privately owned and operated – open only to the general public on fundraising open days when thousands take to its slopes – and it overlooks a stunning public beach at Cable Bay.

Ngā Taonga i tēnei marama Heritage this month – subscribe now

Keep up to date by subscribing to our free e-newsletter

Ngā Taonga i tēnei marama Heritage this month Visit www.heritage.org.nz (‘Resources’ section) or email membership@heritage.org.nz to be included in the email list.

HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND POUHERE TAONGA DIRECTORY

National Office PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140 Antrim House 63 Boulcott Street Wellington 6011 (04) 472 4341

information@heritage.org.nz

Go to www.heritage.org.nz for details of offices and historic places around New Zealand that are cared for by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

In 2017 Sean Garwood shared his story about producing 16 oil paintings depicting aspects of Antarctic heritage, including the huts of Shackleton and Scott and the artefacts inside them.

The Nelson-based artist specialises in heritage subjects, and for a new exhibition –A Painted Voyage, documenting aspects of New Zealand’s maritime history – he’s captured more of our historic heritage, including this striking scene (above) of Queens Wharf in downtown Auckland.

Sean says he chose to include the Category 1 historic place in the exhibition because he felt its development was a milestone for New Zealand in its rise as a global trading nation.

The painting is set in 1904 for a number of reasons, he says, including that the best reference sources are from around this period. Rather than being copied

from a particular photograph, the painting is a mixture of several archival photographs that, although quite ‘grainy’, offered sufficient information with which to make preliminary drawings.

“I was very conscious that the vessels included in the painting were visiting Auckland during 1904,” says Sean, who had a career at sea before becoming a full-time artist.

“The early 1900s witnessed an increase in steam-driven vessels, and I wanted to include these alongside the majestic square-rigged sailing ships.

The famous Jessie Craig is berthed on the northern side of the wharf and a New Zealand Shipping Company vessel on the south side, which also indicate New Zealand’s strong maritime heritage.”

When carrying out research for the exhibition, Sean connected to the Alexander Turnbull Library online collections and numerous rare shipping books from private collections that depicted historic New Zealand port scenes.

He says the Queens Wharf painting captures a time when ships were household names, ship owners and captains were amongst society's elite, and shipping news was eagerly anticipated.

“As the painting progressed, it really did become apparent how close these magnificent, majestic sailing ships were to the town. They were close enough that people could stroll down to see these ships working their cargo; their bowsprits and jib booms towering over Queens Wharf, almost reaching the other side.”

For more information, visit www.seangarwood.co.nz

There was ‘The Shambles’ – once home to a gigantic orange fungus – and ‘Pink Flat the Door’, conceived as an experiment in cohabitating without rules.

But surely the most famous of Dunedin’s named student flats now has to be 660 Castle Street.

This flat is where arguably New Zealand’s biggest band – Six60 – formed while its members were University of Otago students, and from which the band takes its name.

And this year the mana and heritage of the flat were recognised when the band purchased it, with the aim of nurturing the next generation of performing arts talent within its walls.

In partnership with the University of Otago, the band is offering four $10,000 scholarships annually to performing arts students, plus the chance to live in the flat and be mentored by the band.

The house at 660 Castle Street was one of the named student flats featured in Scarfie Flats of Dunedin, written by Sarah Gallagher, a Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Heritage Advisor, along with Ian Chapman.

In the book, which featured in our Winter 2019 issue, Sarah details Six60’s deep connections to the house, which was originally built in 1923 as a Presbyterian Manse.

It paints a picture of how, despite it being a typical student flat (band member Eli Paewai recalls it was “ugly, draughty, run-down and stank”), the place was fundamental to the band’s genesis and identity.

“That’s where it all began,” lead guitarist Ji Fraser recounted to Sarah.

“It’s where I wrote my first song; it’s where we had our first practice together. It was the beginning of everything.”

The mana and legacy of Whakaotirangi, experimental gardener and scientist, continues to resonate in the landscape almost 700 years on

WORDS: DENISE IRVINE

When Whakaotirangi stepped ashore from the great waka Tainui at Kāwhia Harbour, she carried a kete of precious kūmara and taro tubers from her tropical Pacific homeland of Hawaiki.

Whakaotirangi was the principal wife of Hoturoa, captain of the waka Tainui, and she had safeguarded the tubers and some other plants on the long, eventful sea voyage.

She subsequently moved north from Kāwhia, over the hill to Aotea Harbour, where she established extensive gardens with the contents of her kete. The tranquil inlet she chose was named Hawaiki Iti, in honour of the homeland, and gardens were also planted at nearby Pākarikari.

Nearly 700 years later, the mana and legacy of Whakaotirangi, experimental gardener and scientist, resonate through the Aotea kaitiaki of Ngāti Patupō and Ngāti Te Wehi, and all Tainui descendants. In 2017, Whakaotirangi was selected as one of the 150 women celebrated by the Royal Society Te Apārangi for contributing to knowledge in Aotearoa New Zealand.

And earlier this year, Hawaiki Iti, her onceabundant Aotea garden, was recognised and listed as a wāhi tapu site with Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, acknowledging its cultural and spiritual importance to Māori.

Diane Bradshaw of Ngāti Te Wehi says Hawaiki Iti is central to Aotea Harbour’s unique identity in Aotearoa New Zealand.

“The ‘footprint’ of our ancestress Whakaotirangi, her life and culture, provides a direct connection to the tūpuna of the Tainui and Aotea waka. The adaptation of tropical food plants to our temperate climate must have been a major challenge, and this landscape retains her legacy today.”

Pita Te Ngaru of Ngāti Patupō describes Whakaotirangi as “the mother of a nation”: “If it wasn’t for her growing the kūmara and taro at Aotea, would we have survived as well as we did? In her small kete there may have been 10 kūmara tubers, and from these she created a massive garden and dished them [kūmara plants] out all over the place.”

Pita describes how Whakaotirangi would have known when it was the right time to plant.

“She would have looked at the bird life here, the sea, the bush, to judge the seasons.”

He says the soil at Aotea would have been very different from the soil in the tropical homeland. There would have been much experimentation by this

talented gardener and scientist, who generously shared her knowledge and plants across the Tainui rohe.

The descendants of Whakaotirangi cherish her legacy. They want her work to be celebrated and understood by generations to come. It is hoped that the wāhi tapu listing will play a part in this.

The application came after hui more than two years ago at Mōkai Kāinga marae, near Hawaiki Iti, led by kaumātua Nick Tuwhangai. It was supported by Ngāti Patupō and Ngāti Te Wehi representatives, including Pita Te Ngaru, Chris Tuaupiki, Polly Uerata, Maxine Moana-Tuwhangai and Diane Bradshaw.

The listing report was researched and written by Isaac McIvor, a PhD candidate in Te Pua Wānanga ki te Ao Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies at the University of Waikato. He worked in consultation with Xavier Forde, who was at that time Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga team leader for listing Māori heritage sites.

Isaac has whānau connections to Ngāti Patupō. He learned about Hawaiki Iti and he and Pita Te Ngaru talked about what a wāhi tapu listing might mean for it; the mahi grew from there.

The 56.7-hectare site encompasses the extensive Hawaiki Iti swamp and the Kowiwi Stream. These days it is hard to imagine the bountiful gardens of Whakaotirangi: there are remnant clumps of wildling taro, and other natural resources such as harakeke, raupō, wātakirihi and ponga fern. Of the legendary kūmara there is no trace.

There are also archaeological remains in the form of pā, storage pits, ovens and middens, indicating the communities the land once supported. Some links endure: Diane Bradshaw says Hawaiki Iti taro is a delicacy served annually at the poukai at Ookapu marae of Ngāti Te Wehi.

Hawaiki Iti has long been part of a privately owned farm and it has felt the impacts of farming activity, forestation and erosion. For local iwi and hapū, the wāhi tapu listing offers greater opportunities for the protection of, consultation on and commitment to the wellbeing of the whenua.

Pita is particularly concerned about the area’s water quality and the depletion of taro stocks. This has spurred his support for the listing. He says about three or four years ago – using an informal arrangement of harvesting by local whānau – he went to Hawaiki Iti with his cousin, Maxine Moana-Tuwhangai, to look for taro. There was not a lot to be found, in marked contrast to its abundance in the late 1970s when he had harvested it as a child for his grandmother.

“This land has been growing taro and other resources for almost 700 years, and it could be gone in five minutes. We’ve eaten the taro and the watākirihi; our mokopuna may only ever hear stories about it. I don’t want that to happen.

"We don’t want to buy the land back, or claim it back, we want to protect it. It is about exercising our kaitiakitanga, our guardianship.”

He says the aim is to work with the owner and see how whānau can clean up the blackberry, preserve the area, preserve what is left of the taro and talk to surrounding farmers about how everyone can work together to improve the water quality. A trust could be established to care for the wāhi tapu, he says.

hapū: sub-tribe

harakeke: flax

kaitiaki: guardians

kete: woven basket

mauri: life force, essence

poukai: a series of annual visits by the Māori King to Kiingitanga

marae

raupō: bullrush

rohe: region, territory

tūpuna: ancestors

wātakirihi: watercress

whenua: land

Pita recalls his grandfather, Te Huia Te Ngaru, telling him how Hawaiki Iti was named – the story passing through many generations.

Whakaotirangi was living separately from her husband Hoturoa, who was elsewhere with his junior wife. When Whakaotirangi planted her kūmara gardens at Aotea, she wanted to show the flourishing crops to Hoturoa, but she knew he wouldn’t come if she simply sent for him. So she asked their son to visit him, and to say that she was near death: “E Hotu, kua tata mate a Te Oti. Oh Hotu, Te Oti is about to pass away”.

Hoturoa felt aroha for Whakaotirangi, so he went to visit her. When he arrived, he looked out upon the land and saw the huge kūmara crop that his principal wife had created in his absence. Overcome with emotion, he fell to his knees. It rekindled his love of Whakaotirangi, and they resolved their difficulties. It was at this place that their mauri came together again. What Hoturoa saw reminded him of his tropical homeland and he named the area Hawaiki Iti – Small Hawaiki.

The dream now, in 2021, is to repopulate Hawaiki Iti with taro and teach younger generations how to replant it, sustain it and make it flourish again. And honour the legacy of the remarkable Whakaotirangi.

The photograph of Waiuta on the front cover of the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero report is a knockout.

It was taken on a cellphone by Robyn Burgess, Senior Heritage Advisor for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, while visiting the site of the former goldmining town in the Upper Grey Valley, which was built around one of New Zealand’s most successful quartz mines.

The photograph, below, shows the chimney and foundations of a bowling green pavilion that was constructed on top of a flattened mullock heap around 1931.

Framed by a vast sky and a layered hinterland, the image references both the isolation and the social infrastructure

of Waiuta, a recently listed Category 1 historic place and once a tight-knit community of 600 people, which is now touted as the West Coast’s best ghost town.

Thanks to an early miner and his camera, the power of photography to speak of places and people is highly pertinent in recounting the Waiuta story.

Czech immigrant Joseph (Jos) Divis came to New Zealand in 1909 following a period of mining in Germany, and over time made Waiuta his home. In his unofficial role as resident photographerminer, he recorded a visual legacy of daily life in Waiuta from 1910 to the mid-1930s, when the town was bustling with activity.

Sam Symonds, Greymouthbased DOC Senior Ranger, says

the Divis photographic record is invaluable.

“The huge collection of photos is a real blessing, and those taken underground are amazing gems. Men in tough conditions, shirts off, smiling at the camera. They would have been blinded by the flash for a few seconds and then gone straight back to work.”

That those gritty scenes below ground ended so abruptly in the winter of 1951 sets Waiuta apart from other old goldmining towns.

It was an unlikely scenario, given the buoyant backdrop of what became the West Coast’s largest-producing goldmine owned by heavyweight player, London-based Consolidated Goldfields, which made a substantial investment in the

WORDS: ANN WARNOCK

The fortunes of West Coast goldmining town Waiuta changed in an instant, but tantalising clues to its once-thriving past remain

local mining operations and the development of the town.

And initially the good times rolled. Blackwater Mine, the first mineshaft at Waiuta, was fully operational by 1908, with gold being processed at the nearby gravity-fed and water-powered Snowy River Battery.

In the 1930s an adjacent shaft, Prohibition Mine – New Zealand’s deepest at nearly 900 metres (including 264 metres below sea level) – came into play.

The highly productive Prohibition Mine spurred advances in processing, and a modern ball mill (a type of grinder that was used to grind and blend ore), built close by, superseded the Snowy River Battery plant down the valley.

The leaps and bounds of Waiuta’s mining operation were mirrored in the life of the town.

Rudimentary housing became a permanent built environment with staff dwellings at so-called ‘Nob Hill’ and a large cluster of houses for miners and their families – one local road was even known as ‘Incubator Alley’.

Interestingly, Jos Divis’s photographs reveal that despite the strata of management and miners, the inhabitants of Waiuta mixed without social divide.

The township’s workforce came from the international mining community – including

Australians, British, Italians, Dalmatians and Danes – which meant the population was far from ordinary. So too were its abundant facilities – a swimming pool, bowling green, rugby field, whippet-racing track and tennis courts, plus sporting clubs, an enviable calendar of balls and picnics, and an ardent community atmosphere.

When Waiuta staged its jubilee in 1931, said to be the greatest event in its history, gold prices were rising and a sense of opportunity pervaded the town. Ironically, however, the story of Waiuta was already more than half over.

World War II recruitment triggered a decline in miner numbers, and the gold output from Waiuta plummeted to less than a third of its pre-war volume.

But despite the diminishing forces of war and yield, the end was still a shock.

In July 1951, when the original Blackwater Mine providing essential ventilation to underground workings suddenly collapsed, Consolidated Goldfields made a snap decision to close the mine.

One week it was a township, then three weeks later – with houses dismantled for timber or carted away and machinery sold, scrapped or abandoned – Waiuta had all but vanished.

By 1953 the town’s population stood at 14.

But Robyn says the place was not forgotten, and in the 1980s it became “an early draw for heritage tourism”.

The highly motivated group Friends of Waiuta, formed in 1985, now works in partnership with DOC to protect and promote the Waiuta site.

The ongoing restoration of several remaining cottages, historic-site clearance and ecology enhancement are on its trajectory.

A major decontamination programme in 2016 removed material containing arsenic – the result of gold extraction methods used at the Prohibition Mine site –from the area.

President of Friends of Waiuta Margaret Sadler, who lived in Waiuta until the age of four, says many of its members – some based overseas – are descendants of Waiuta miners. She says the group is propelled by “wanting to give others a window into this world”.

The recent commemorations marking the 70th year since the closure of the Blackwater Mine were, she says, “an emotional reunion”.

While only tantalising traces of the Waiuta way of life remain today, the town site continues to resonate.

“Waiuta has outstanding significance and value,” says Robyn. “Its historic mining and domestic features dotted around the valley might seem like a far cry from a bustling town within a noisy mine operation, but remarkably the former mine and town are still so readable, despite the loss of so many of the standing buildings.”

Beyond its physical presence in the isolated West Coast landscape, the poignancy of Waiuta endures.

Queensland-based Andrew Saunders, whose late father Alf started out in the Snowy River Battery in 1929 and moved to Australia when the mine closed, says, “Every time my father went back to New Zealand later in life, he visited Waiuta.

“I think it was the sudden way nearly everyone had to leave without any preparation for doing so – it left them with some longing for the place.”

In 2020 Waiuta became part of Tohu Whenua, a nationwide visitor programme that connects New Zealanders with their heritage and enhances a sense of national identity by promoting significant historical and cultural sites. To learn more about visiting Waiuta, read our domestic travel piece on page 44.

Andrew Brown has built a successful career immersed in New Zealand archaeology. So how did he get involved in the quest to unearth the secrets of the mysterious Stonehenge?

For Andrew (Andy) Brown, the opportunity to help uncover the secrets of one of the world’s most famous monuments started with a knock on his door.

Mike Parker Pearson, Stonehenge scholar and giant of the UK archaeology scene, is also famed for shouting students a beer. So when the University College London (UCL) Professor of British Later Prehistory called in to the Kiwi’s university office, the then-PhD student heeded the call and headed to the pub.

“We were having a beer and I said to Mike, ‘Do you have any digs on?’ because I’d been in the UK for more than a year and hadn’t done any digging, and really wanted to,” recalls Andy, now a Whangārei-based consultant archaeologist.

“He said, ‘Yeah, we’re going to Wales. Do you want to come?’”

That invitation led to Andy working a number of stints on the Stones of Stonehenge Project. Led by Mike and fellow project directors Colin Richards, Josh Pollard and Kate Welham, the project investigated the origins of the ancient monument and focused on its bluestones. It followed the Stonehenge Riverside Project – a major archaeological study of Stonehenge and its landscape, which ran from 2003 to 2009.

Stonehenge’s smaller bluestones (as opposed to its larger sarsens) originated in the Preseli Hills in Wales –around 230 kilometres away from where the monument stands today on Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire. The Stones of Stonehenge Project – which drew on experts from a wide range of fields – aimed to locate the quarries from which the bluestones had been sourced. It also sought evidence to support the theory that the stones were actually part of an earlier monument erected much closer to their source, and later disassembled and re-erected in Wiltshire.

“The findings of the project really showed Stonehenge in a different light,” says Andy. “It was remodelled a number of times and the bluestones were always a part of it. When you start engaging with Stonehenge in that way, you see it much more as a living, changing monument.”

Stonehenge’s place of origin is a world away from Andy’s own – and far from the focus of his career.

Although instilled with a passion for history by his parents during his childhood on a farm just outside

Hāwera, Andy can’t recall an ‘aha’ moment when he realised archaeology was his calling.

“When I went to uni, it was to study archaeology; it wasn’t with a sense that I was going to be an archaeologist. I’d never met anyone who was an archaeologist, and more than a few people said to me, ‘How are you going to get a job doing that?’”

It was in his honours year at the University of Otago, when he joined a research group led by Richard Walter and Chris Jacomb looking at the first century of Māori settlement, that a fire was really lit.

“We did a number of excavations of early sites. I was always just one of the team, and I found it cool looking at things like ovens; and it’s not just one object, you can see from its features how a village might have been laid out and how people were living in that space.”

That work proved a launching point for his academic career. For his master’s degree he looked at changes in material culture in early Māori settlements in Otago, then explored the topic more widely – looking across New Zealand and incorporating other factors like demography – during his PhD at UCL, which is among the top three universities globally for archaeology.

“One area of my master’s that really interested me was how you account for changes in material culture. One of my particular areas of interest was evolutionary theory – thinking about how artefacts change in a way that’s analogous to genetics, where some characteristics are selected for, and others piggyback or change in frequency through random processes.

“Stephen Shennan, a professor at UCL, is a thought leader in this space, so I thought I’d be cheeky and send him an email. He said he’d be interested in supervising, and that’s how my PhD started.”

Andy’s research continued during three years of postdoctoral study at Bournemouth University as a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow.

Work on the Stones of Stonehenge Project punctuated his time in the UK. Initially, while at UCL, he was involved in excavating two quarry sites – at Craig Rhos-y-felin and Carn Goedog in Wales – identified as sources of the bluestones.

Later, while at Bournemouth University, he helped supervise a large geophysical survey, led by Kate Welham, Professor of Archaeological Sciences, to identify possible original Stonehenge sites.

“The last year I was there we surveyed a site called Waun Mawn – a weather-beaten place on a Welsh hillside

– and we found some stone holes. The year after I left, they found more – and they’re fairly convinced that’s the location of the first erection of stones.”

In 2019 Andy returned to New Zealand from the UK. He now runs an archaeological consultancy, which, in association with Whakatāne-based archaeologist Lynda Walter, carries out projects spanning the upper North Island.

But connections made through the Stones of Stonehenge Project continue.

Josie Hagan joined the project as a first-year archaeology student of Kate Welham, and with an interest in New Zealand, she struck up a conversation with Andy at the pub after a day’s fieldwork.

The pair kept in touch, with Andy later supervising Josie’s undergraduate dissertation at Bournemouth University, where she investigated the suitability of using LIDAR, 3D laser scanning, to explore New Zealand archaeological sites.

Her interest in New Zealand archaeology piqued, Josie has since moved here, undertaking archaeology work for Lynda, and now doing her master’s degree at the University of Otago. Due to finish in March 2022, her project is combining cultural mapping with traditional archaeological methods at a land block just south of Gisborne, exploring how this can support the aspirations of the Māori landowners.

“As undergraduates, we don’t study New Zealand archaeology in the UK, so there was a lot to get my head around when I did my dissertation. But having Andy as my supervisor was brilliant, because he’s just so passionate about New Zealand archaeology,” says Josie.

“Now that I’m here, I feel like it’s a dream come true. It’s been a steep learning curve, but I can’t believe I’m actually here, that I have this job in archaeology, and how different my life is from two years ago.”

Likewise for Andy, the passion for the work continues.

“It’s such a cool job, and a good fit for my personality,” he explains. “You’re always in different situations and get to talk to everyone from CEOs to digger operators, explaining what you want to do and why.

“The nature of the job means you’re also often outside, digging and exploring. Then there’s the discovery aspect, where you’re right on the edge, interpreting something tactile that’s right in front of you.”

There are so many great places that I’ve had the privilege to go to and work at over the years, but in the end my favourite heritage place has to be somewhere in my turangawaewae – south Taranaki.

The place has so many layers of history, with sites from throughout the pre-European period, the New Zealand Wars and beyond into the agricultural period when so many, now disused, dairy factories sprang up.

The site I’d single out is Camp Waihi, south of Normanby and near where I grew up. The camp was the headquarters of the armed constabulary during the conflict with Tītokowaru; the redoubt’s ditches have been ploughed but are still just visible in the paddock. It is marked by a small, often overgrown cairn made of river boulders. On the ground below is the soldiers’ cemetery associated with the camp where many of the casualties from Te Ngutu o te Manu are buried alongside more recent burials.

Right next to the cemetery is Pikituroa Pā, which has a number of storage pits circled by a deep defensive ditch. Little is known about Māori occupation of the site, but its defences were re-used for a redoubt prior to the construction of Camp Waihi. What I love about this place is that it has all these aspects of history interacting within such a small area. n

Findings from the Stonehenge Riverside Project and the Stones of Stonehenge Project form the basis of the Secrets of Stonehenge exhibition, which opens in December at Auckland Museum.

The exhibition – a collaboration between English Heritage, the National Trust, The Salisbury Museum and the Wiltshire Museum – features more than 300 ancient artefacts and shines a light on the cuttingedge research that has led to a new understanding of where, when, why and how Stonehenge was built.

As part of the exhibition programme, Auckland Museum is delivering a series of talks that will include presentations from UK-based Stonehenge experts, as well as Andy Brown – who’ll share more of his story of involvement with the Stones of Stonehenge Project – and Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Chief Executive Andrew Coleman. For more information, visit www.aucklandmuseum.com

Winemakers at an historic Te Kauwhata winery are proud to follow in the footsteps of the man credited with inspiring viticulturists in New Zealand 120 years ago

Invivo winemaker Rob Cameron is not given to ostentation and hyperbole. He abhors wine snobs and the pretension that sometimes accompanies wine tasting. But put him in a dimly lit, cobweb-festooned room not much bigger than a double garage, where wines dating back more than half a century are having a lie-down, and he is in raptures.

“It’s like a library of wines,” he says, lifting from a rack a dusty Müller-Thurgau – a sweetish white wine popular in New Zealand in the 1960s. The contents would now be undrinkable, not only because of age, but also because New Zealanders’ tastes have matured. But Rob likes that it still has a place in the cellar.

In another room – a fermenting house dating back to 1903–4 – are huge concrete vats, the material of choice for European winemakers centuries before stainless steel tanks took over with their whizzy temperaturecontrol systems. In a third room – a vast, cool storehouse with lofty kauri ceilings – Rob’s smile broadens.

“My favourite place,” he says.

The room, which was the original wine cellar, is stacked with oval-shaped French oak barrels made from 200-year-old trees, some obtained as part of reparations from Germany after World War I.

“Each [barrel] tells a different story,” says the winemaker. He knows their provenance but remains in awe of their magic.

“They may look the same, but the results will still surprise you.”

It is in this cellar that Rob most feels the presence of his predecessor, the legendary and flamboyantly named 19th-century viticultural scientist Romeo Bragato – the man credited with assessing and inspiring the establishment of viticulture in New Zealand more than 120 years ago.

Bragato was based here for six years from 1902, often arriving late at night during the harvest with a supper of crackers, sardines, pickled olives and claret to oversee the mash.

He once wrote, “It is a fact beyond contention that – in wine-drinking countries – the people are amongst the most sober, contented and industrious on the face of the earth.” Rob thinks they would have got on well.

A Category 1 historic place, the winery occupies a small site on the edge of Te Kauwhata, formerly known as Wairangi (corrected to Waerenga in 1897), a European-style settlement established around a railway station in the 1870s.

1 Rob Cameron says Invivo’s winery is like a library of wines, recording New Zealanders’ maturing wine tastes through the decades.

2 The cellar is a dimly lit space that lays out the story of winemaking through the decades.

3 The winery complex on the outskirts of Te Kauwhata, where 19th-century viticulturist Romeo Bragato worked his early magic.

It is just four kilometres from Rangiriri, the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the Waikato Wars, in which British troops seized more than 400,000 hectares of prized and productive Waikato land. In 1893 the Ministry of Agriculture established the Waerenga Experimental Station to test the suitability of the clay soils for crops, including vines.

When Bragato first came to New Zealand in 1895, he was a long way from home. According to information available on the Waikato District Council website, Bragato was born in 1858 on an Adriatic Island then known as Lussin Piccilo – at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – and now known as Mali Losinj in Croatia. His parents were Italian, and he studied at the Royal School of Oenology in Conegliano in the province of Treviso, Italy.

Bragato was overseeing the establishment of the wine industry in Victoria, Australia, when New Zealand premier Richard Seddon, under intense pressure from farmer settlers who wanted to develop a wine industry, invited him here.

After Victoria’s state government agreed he could take leave, Bragato arrived in Bluff and made his way north, immediately identifying the potential for viticulture in areas that are today

“Each barrel tells a different story. They may look the same, but the results will still surprise you”

New Zealand’s leading wine-producing regions: Central Otago, Canterbury, Marlborough, Wairarapa (Martinborough), Hawke’s Bay and Auckland. He also visited the Waerenga station where grapes were then grown by the government pomologist, WJ Palmer.

Enthused by what he saw, in 1902 he accepted a position as the government viticulturist for the New Zealand Department of Agriculture, and set about improving the research station, including overseeing the construction of the Mediterranean-style concrete fermenting house and cellar, roofed with red tiles.

A further cellar was added later.

Bragato’s passion and enterprise (he introduced American rootstocks resistant to the pest phylloxera, which had destroyed French vineyards in the 1870s) were quickly recognised locally and internationally. While production methods were crude by today’s standards (the grapes were rubbed off stalks with wooden graters), the results were award winning.

In 1908, six wines were entered in the FrancoBritish wine exhibition. Five won gold medals. The path to success seemed assured.

But by 1908 the government and growers had become nervous. The New Zealand Temperance Union had gained traction and there was uncertainty about the industry’s future. Vineyard planting slowed and the viticulture division of the Department of Agriculture was disbanded.

Bragato’s bold ideas for expanding the wine industry languished in a dusty government drawer. Disillusioned, he left New Zealand for Canada. The research station remained in government hands until 1992 when it was sold into private ownership including – from 2003 – to Rongopai Wines.

Four years later it was bought by BAA Holdings, and subsequently occupied by TK Vintners and Bottlers, which had a connection with longstanding winemakers, the Babich family.

When the winery came up for lease in 2016, Rob Cameron was delighted.

“Bragato was a legend. The winery’s history sat well with our values. We want to carry on its legacy as a top winemaker.”

Rob and his business partner Tim Lightbourne are from different backgrounds, but like a good wine, their blend of skills has been successful. Rob’s family are winemakers at Mangawhai Heads. He was a consultant winemaker in Europe, but always intended to return to New Zealand to expand the family winery.

Tim has a commercial background and an entrepreneurial head. When they met for a drink at a bar in Fulham, London, in 2007, the idea of a winery with a difference was hatched. They decided not to invest in more grapes; “Others can do that better,” said Tim.

In 2008 they launched Invivo, which means ‘in life’, at the winery in Mangawhai. Eight years later they moved the business to Te Kauwhata.

1 Some of the wines stored are now undrinkable, but they still have their place at the complex.

2 The original buildings still house remnants of winemaking from earlier times.

3 The distilling equipment includes a large copper still, which was used to make brandy in the 1950s.

4 Huge concrete vats, painted red, stand in contrast to the stainless steel vats installed when technology advanced.

To learn more about Invivo, view our video story here: www.youtube.com/ HeritageNewZealand PouhereTaonga

Their grapes are imported from other New Zealand regions. Rob does the alchemy; Tim does the pitch.

They have partnered with Irish television presenter Graham Norton (“He’s a great guy; loves our wine,” says Rob) and US actress Sarah Jessica Parker. Those names are on their brands and have helped gain the attention of UK and US markets.

Demand has now outstripped supply given a poor growing season last year, plus Covid-19-related supply issues. Despite this, Invivo is expanding, with plans for an extension to the winery in consultation with Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

The winery contains many of the original fixtures, including the red-painted concrete wine vats, the still tower, distilling equipment and the oak barrels. There is a large copper still, which was used to make brandy in the 1950s.

In his listing report for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, Senior Heritage Assessment Advisor Martin Jones says many elements of the complex, listed as Te Kauwhata Winery, are rare or unique in New Zealand.

“The complex is a reminder of government leadership in agricultural science and is the only

substantial remnant of the experimental farm established in the 1890s.”

It is also a reminder of the journey of winemaking in New Zealand. The gold medals won by the station during Bragato’s tenure were extraordinary for a young country still learning the techniques of winemaking. But the growth of the industry and the standard of wines have increased beyond perhaps even Bragato’s dreams.

Rob says in his lifetime New Zealand’s winemaking reputation has become incontrovertibly established and admired, not only in Old World wine regions that have traditions dating back hundreds of years but also around the world.

“It would be unusual not to find a New Zealand sauvignon blanc or pinot noir on the wine list of a top restaurant in the UK and US,” he says.

This year, Invivo and its partners won three gold medals and two trophies at the 2021 New York International Wine Awards. Romeo Bragato would have been impressed.

And while that dusty Müller-Thurgau may no longer appeal to today’s tastes, it’s still a sweet reminder of just how far we have come.

WORDS: MATT PHILP

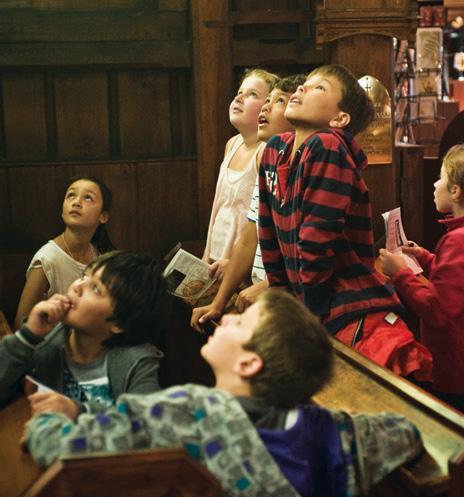

Up and down the country, our historic churches are under threat. And while some communities are finding innovative ways to retain them, heritage losses are also mounting

If you want a snapshot of the perilous state of New Zealand’s historic churches, you only have to consult crowdsourcing site Givealittle.

“Our church is seriously in need of support from all who care about her,” implores the Givealittle page for the 144-year-old St Clement’s Church in the Far North, citing a repair estimate of $350,000.

Another page, for the 1906 St Paul’s Church in the Waipara district, outlines a $2 million quake-repair project to save that local landmark. In Hokitika, meanwhile, the friends of the town’s neoclassical St Mary’s Church recently ran a Givealittle campaign to raise funds for a second engineering opinion on a $7.12 million quake-strengthening estimate. The list goes on.

In Autumn 2012, Heritage New Zealand magazine ran an article called ‘Saving grace’, which pointed to dwindling congregations and ageing buildings with a growing maintenance load as among the reasons for churches being sold off or demolished. The late Stewart Harvey, then chair of the New Zealand Historic Cemeteries Conservation Trust, described it as a quietly unfolding New Zealand tragedy.

2

“Quite a lot of these little country churches that are part of our history are being lost forever,” he said.

“They are sold off as holiday homes and sometimes moved off site, and the big tragedy of it is that everything inside the church goes – the pews, the plaques on the wall, the church furniture...”

Since then we’ve seen the advent of Givealittle and other crowdfunding sites, and some successful campaigns to restore high-profile churches. On the other hand, the challenges have also mounted, with the advent of more onerous earthquake-related standards and insurance companies’ growing reluctance to cover heritage buildings. The buildings and parishioners haven’t got any younger either.

Faced with all this, church authorities are increasingly making hard-nosed decisions to rationalise their property portfolios. The Catholic Archdiocese of Wellington, for example, last year announced the closure of two churches in rural Marlborough following a review of Mass numbers and other factors.

It’s a curate’s egg, in other words, with both wins and losses. But there are certainly signs that, rather than leaving it to congregants or divine intervention, some communities are stepping up to save their landmark

2

churches, which are often the finest examples of built heritage in smaller towns and have meaning beyond their religious roles.

Bill Edwards, Area Manager Northland for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, says he is seeing diverse approaches to the problem.

“One approach involves doing up a church and it continuing as a place of worship. A good example of that would be St Gabriel’s in Pawarenga.

“In some churches where the congregations have disappeared, they’ve been repurposed. An example there would be in Rawene, where we’ve been involved with the National Heritage Preservation Incentive Fund for a church that has been repurposed as an artists’ retreat.

“There’s a Catholic church called St Xavier’s that has been moved near Russell and has been repurposed as a place of celebration for marriages and so on. It’s still associated with ceremony and significance, just not in a religious framework.”

Bill also gives the example of the circa 1860 St James’ Church at McLeod Bay, Whangārei Heads. When the Presbyterian Church signalled it wanted to sell St James’, locals formed a trust and raised $40,000 to buy the land and building. It has subsequently been turned into a

multi-denominational place of worship, and is available to the public for marriages, funerals and other ceremonies.

At Te Kōpuru, near Dargaville, the Category 2-listed 1902 Anglican St Peter’s Church was recently restored using $162,000 from the Provincial Growth Fund. The Chair of St Peter’s Church, Viv Biddles, says the alternative of raising the sum required locally in a community such as hers wasn’t realistic.

“I put a quiz on once a year and we have the odd potluck dinner in the hall, but if you make $1,500 from a fundraiser, you’re doing really well,” she says, adding that the restoration of the church “has given our community a lot of pride and mana”.

Another success story is St David’s Memorial Church, on Khyber Pass Road in Auckland (see ‘Art and minds’, Heritage New Zealand magazine, Winter 2020). Built in 1927 as a memorial to World War I soldiers, the church was put up for sale earlier this year by the Presbyterian Church Property Trustees, which cited as the reason declining attendance and the prohibitive cost of some required earthquake strengthening.

After an initial national campaign raised $1 million by selling bronze quatrefoils gifted by artist Max Gimblett, subsequent fundraising efforts from the sale

1 Viv Biddles (right) and Kaye Welch, who spent considerable time organising the funding required for the restoration of St Peter’s Church at Te Kōpuru, near Dargaville.

IMAGE: JESS BURGES

2 A structural engineer’s report has put the cost of repairing St Clement’s Church in the Far North at $350,000.

IMAGE: LENNOX GOODHUE WIKITERA

3 The newly restored interior of St Peter’s Church.

IMAGE: JESS BURGES

of commemorative pins designed by jewellery artist Warwick Freeman and through donations, community charity The Friends of St David’s Trust is now in the process of purchasing the church (from the successful buyer of the wider St David’s site) and intends to restore the church and repurpose it as a music centre.

Paul Baragwanath, the group’s founder, says St David’s needn’t have been threatened at all, and that church organisations are being too hasty in quitting their buildings. They need to think more creatively about repurposing them for ongoing roles, he says, lamenting the loss of such “sacred spaces” to private development.

“When a church changes from being a civic space to being a private dwelling or office space, that’s a major loss for society,” he remarks.

“It’s important to have these spaces where human beings can connect and be uplifted and sustained. You can’t underestimate the importance of it for a healthy society.”

There’s something of that thinking in Anna Miles’ and Michael Simpson’s approach to the little 152-year-old church they own in Kakanui – albeit on a humbler scale.

The RA Lawson-designed church featured in the ‘Saving grace’ story as one at risk of closing, being beset by rot and with a tiny congregation unable to pay for repairs. It limped on until Anna and Michael, owners of a horse-breeding operation at nearby Waimate and lovers of heritage, bought it in 2019.

They didn’t have any firm plan, according to Michael. “We just thought we could save it, so we should try. The building needs life in it. We hope that if we restore it and don’t carve it up, we’ll secure its future to be used for things like weddings, or gigs and exhibitions, or if the church wants to hold a service. It’s keeping all the options open.”

They’ve been doing the restoration work themselves at weekends and in other spare moments, initially focused on fixing the roof to keep out rain and birds and tackling areas of rot. New weatherboards will go on this summer.

“When we’re there we open the big double doors at the front and make it welcoming for people to come in,” says Anna, who adds that they plan to nominate the building for heritage listing.

“We’ve talked to so many people who’ve shared their ties with the building, and through that we’ve realised how important the church is to them – we’re just the stewards of it for the moment.”

The rescue at Kakanui is a good news story, as are the others mentioned previously. But there are at least as many losses in the ledger – churches sold or bowled to the dismay not only of congregants but often of their communities.

2

In some cases church owners are being challenged on their calls. In Dunedin, for example, the announcement in 2019 of parish plans to demolish the nearly 100-year-old Highgate Presbyterian Church sparked a petition from residents, an appeal by parishioners and the commissioning by campaigners of a new seismic assessment of the building.

we would not have been able to undertake the postquake work we have,” he says.

However, apart from the various quake-recovery funds, which have now closed, no new funding avenues of any significance have arisen since 2012. Meanwhile, seismic strengthening deadlines are looming, says Gavin, adding that under current rules the CPT can’t access government funding for that work.

1 New weatherboards are about to go on at Kakanui.

2 New owners of the Kakanui church Anna Miles and Michael Simpson: “We just thought we could save it, so we should try.”

3 The roof of the church has been bird- and weatherproofed ahead of a larger restoration.

IMAGERY: MIKE HEYDON

There’s certainly an argument to be made that in some cases owners are being too hasty. But that only goes so far. In ‘Saving grace’, the then assembly executive secretary of the Presbyterian Church pointed out that Dunedin’s magnificent First Church was arguably of national significance, certainly of huge historic significance to Dunedin, yet the cost of its upkeep was falling entirely on the shoulders of a small congregation. Some high-profile churches, such as Auckland’s St Matthew-in-the-City, have generated income by hiring out spaces for corporate events, but that’s not an option for everyone.

Funding church restoration and seismic strengthening is a major challenge, says Gavin Holley, General Manager of the Church Property Trustees (CPT), the body that manages the assets of the Anglican Diocese of Christchurch.

After the Canterbury earthquakes, the CPT repaired and in many cases restored 34 earthquake-damaged, heritage-listed churches and halls, supported by funding sources such as the Christchurch Earthquake Heritage Buildings Trust and Christchurch City Council heritage funding.

“We also remain incredibly grateful to the Lottery Environment and Heritage Committee, without which

“The biggest challenge, however, is that earthquake [natural disaster] insurance is unaffordable for all but a few of our churches.”

In Wellington, where 25 Catholic churches have been deemed earthquake risks, the prominently located 1908 St Gerard’s Church and Monastery in Mt Victoria closed its doors this year after the owners failed to raise the estimated $10 million to get it strengthened.

Felicity Wong, Chair of Historic Places Wellington, says there’s been some talk recently that the iconic building above Oriental Parade could be turned into a hotel. While that’s certainly better than losing it, it’s not ideal.

“What we have to grapple with is how we repurpose buildings that were built by the public for [public] purposes,” says Felicity, who believes public money should be used in the case of St Gerard’s.

That doesn’t go for all threatened churches, however.

“I think it’s a question of focusing on the ones that are really iconic, putting our eggs in fewer baskets, and then trying to broaden out the usage,” she says.

“That means collaboration between the religious orders and communities, so we can find modern, vital purposes beyond the religious constraints of these buildings.”

My friends live in an old Norwegian house on Rakiura/Stewart Island. On one of my trips to Rakiura, I rented a kayak to explore the history of Kaipipi Shipyard (often referred to as ‘the Whalers’ Base’) at Paterson Inlet.

Founded in 1923, the Kaipipi Shipyard was a repair base for Norway's Rosshavet (Ross Sea) Whaling Company, while also providing a base for the whalers who operated in the Antarctic waters.

TECHNICAL DATA

Camera: Sony Alpha A55V

Exposure: 1/50sec at f/11

Focal Length: 12mm (x1.5)

Lens: Sigma 10–20mm F3.5

A little over four years ago, a Nelson couple took on a heritage restoration of epic proportions. Now, more than halfway through the project – undertaken largely by themselves – we check in on progress at The Gables

WORDS: TRACY NEAL • IMAGERY: VIRGINIA WOOLF

It had once been a grand home. More recently, however, The Gables had stood as a crumbling monument to the dreams and ambitions of Nelson’s early European settlers.

The 400-square-metre brick-and-plaster building, sited beneath the rolling hills of Waimea West, near Nelson, was certainly on its last legs when Keith and Lorraine Davis first noticed it in 2005, while on holiday from the UK.

Says Keith: “Every time we went down Waimea West Road, we’d always slow down – much like everyone else who slows down to take a look at this house.”

But it was less the building’s decayed state and more its distinctly British bones that caught the couple’s attention.

The Gables – built from bricks that were dug, prepared and then fired on the site – is modelled on a home in Suffolk, England, from where the original owner, John Palmer, came. The entrepreneur arrived in Nelson on the barque Phoebe in March 1843, building The Gables in 1865 as a family home and later operating it as a store and accommodation house and as a base for his carrying business.

Alison Dangerfield, Central Region Area Manager for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, says the distinctive building, believed to have been designed by James Thorn, who signed the specifications for the building, is one of only a few of its style in New Zealand.

Chasing the dream

That holiday in 2005 convinced the Davises to move to New Zealand. They returned to the UK, sold up their building industry businesses, and farewelled the stress of busy lives. They admit it was a gamble.

Keith’s multiple gas-fitter qualifications weren’t recognised by New Zealand authorities, but a job offer on his arrival got them over the residency line.

They bought in to the Kiwi dream – initially in the form of a property in the Motueka area and a holiday home in the Marlborough Sounds – but the dream was not complete.

One day in September 2017, on another slow drive past The Gables, Keith noticed a small ‘For sale’ sign on the building, and within days it was theirs.

“I think the house drew us here,” says Lorraine, a firm believer that the spirits of long-dead former occupants beckoned them to the building. She and Keith suspect these spirits are manifested in the silent coloured orbs that occasionally bounce around rooms as they work.

A neighbouring bungalow bought by Keith’s father served as a base while they began the rebuild, which was delayed by a decline in the health of Keith’s father, and his subsequent death.

The bungalow was then sold, and Keith and Lorraine moved into The Gables in January 2020. The house had no bathroom and no running water, and rats were living in nests throughout its decaying scrim and sarking walls and ceilings.

“I’ve since taken six rats’ nests out of the roof of one room – I had six dustbins full of rat crap and more than a century’s worth of dust to deal with,” says Keith.

Alongside his experience as a gas service engineer, Keith trained in many other aspects of the construction trade and has undertaken most of the work himself. He has approached the colossal renovation “gable by gable” from a 60-page plan he drafted near the beginning of the process.

“The way I look at it, each room is really its own house. In simple terms, it’s segmented into six boxes downstairs and six upstairs, with a staircase and hallways.”

The east-facing lean-to, which now houses a stylish kitchen and living area complete with a butler’s pantry and laundry, was the first section of the house made habitable.

1 The Gables’ long-sealed doorways have been reopened to reveal an original, well-worn wooden staircase that once led to the maids’ quarters.

2 Owners and restorers Keith and Lorraine Davis outside the cedar-clad lean-to, which houses a new kitchen and living area.

The cedar-clad weatherboard exterior now offsets white joinery made in the original, traditional colonial style. The rest of the home’s plaster exterior has been freshly painted in the heritage colour ‘Butter Yellow’.

Keith says a major milestone has been redoing the floors. Records show that although the base runners were mataī, borer had destroyed the floors, which were made largely of kahikatea, and poor ventilation at ground level had caused wet rot.

He says the challenges have been less about the physical work than higher-than-expected costs – and finding an expert who can craft the classical Egg and Dart plaster cornices to the standard required.

“It’s a traditional English build so it didn’t frighten us at all. I knew all the floors upstairs and down were knackered when we bought it. I knew all we’d have was an east wall and a west wall, and a couple of internal walls holding them together.”

The grandson of the building’s original owner, a Nelson businessman and horticulturist also named John Palmer, still farms part of the original land at Waimea West. He says he is delighted to see this significant and important restoration going ahead.

“To see someone doing this is just fantastic. There wasn’t the capacity within the family to do it, but Keith is doing a tremendous job.”

John says he and his cousin, former prime minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer, who had earlier investigated ways to salvage the building, had calculated restoration costs at several million dollars.

The restoration of the Category 1 building has been supported by two grants from the National Heritage

Preservation Incentive Fund, which provides incentives to encourage the conservation of privately owned heritage places recognised on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero.

Alison Dangerfield says the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Board, which allocates the funding, did not place onerous requirements on the rebuild. The aim was to achieve the best possible outcome and the grants were given as a helping hand.

When the Davises took ownership of The Gables, its north and south exterior walls had bulged and were close to collapse. Keith says the north wall had pulled away from the building by 75mm, and the south wall by 50mm, most likely due to the weight of the original slate roof.

1 Keith approached the renovation from a 60-page plan he drafted.

2 Each room is being stripped and relined.

3 The Gables is now freshly painted in heritage colour Butter Yellow.

4 A stylish new kitchen is a central feature of the lean-to.

5 One of several newly renovated lounges.

6 With its dormer attic interior, an upstairs master bedroom is reminiscent of a cosy English cottage.

7 Keith has expertly tiled the ensuite bathrooms that will complete each bedroom renovation.

“A project involving a building of this age and complexity is huge and involves so many processes.”

She says the building is well known throughout the NelsonTasman region and there is a high level of enthusiasm for its revival. “It will be a joy to look at once it is completed.”

Keith says that is likely still a couple of years away. The home has been reroofed, work on the north gable is almost finished, and the focus is now on the south gable before moving on to the middle gable.

He credits Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga for guiding the process in a way that respects not only the cultural necessity to preserve our heritage but also the couple’s own capabilities and knowledge as renovators in a foreign land.

Keith and Lorraine envisage The Gables again becoming a family home, but they are also thinking ahead to its potential use as accommodation.

While they haven’t once regretted taking on the project, Lorraine admits that the dust, which still manages to seep through sealed doorways cloaked in sheets, can be trying.

Keith says he is enjoying being occupied by the project, but when it gets a bit much they pack up and go fishing. His single piece of advice to anyone thinking of taking on a similar project is to make sure you have either the expertise to do most of it yourself or seriously deep pockets.

The final stage of what will likely be a five-year project will be landscaping, after which The Gables – and its ghosts –can rest easy.

David Vanstone, who owned The Gables from 2000 to 2003, had secured the walls with six tie rods running the length of the building. One of Keith’s first jobs was to remove the failing walls and rebuild them in concrete block, plastered over, with outlines etched into them to replicate the original ashlar masonry.

The floors downstairs are being rebuilt with hardfill and overlaid with reinforced concrete, insulation and a floating timber floor of imported oak. Tradespeople have been employed to help with the concrete flooring and some of the building work.

Each room is stripped back to accommodate electrical cabling and insulation before being relined in GIB plasterboard.

Upstairs, the floors are being entirely rebuilt before work can commence on the ceilings and walls.

Custom-made wooden joinery has replaced many of the rotten window frames. Keith says it was a major mission, but made easier by the expertise of their joiner, who is familiar with the irregularities of old houses.

The installation of new services required oversight by iwi and an archaeologist. The property required new drains, rainwater tanks and a septic field of a size suitable for a property with six bedrooms, each with an ensuite, or a 12-person home.

Long-sealed doorways have also been reopened to let in more light to the building’s core, and to showcase a well-worn wooden staircase that once led upstairs to the maids’ quarters. n

In the lead-up to Waitangi Day 2022, two of those charged with overseeing one of our most important historic sites reflect on their connections to the Waitangi National Trust estate

WORDS: CAITLIN SYKES • IMAGERY: ERICA SINCLAIR AND JESS BURGES

Nga wai hono i te po Paki, Waitangi National Trust board member since 2020

Commemorations for New Zealand’s national day are known to start early. But for Nga wai hono i te po Paki, a particularly memorable Waitangi Day started earlier than most.

“It was 2009, when I was around 12 years old, and I remember getting up at what felt like 3am a day or two before Waitangi Day and heading down to Tūrangawaewae Marae for karakia and to prepare the waka taua,” she recalls.

“It was my father’s first visit to Waitangi after being anointed King, and six waka taua, more than 200 paddlers, and more than four busloads of us travelled from Waikato to Waitangi alongside him. It was a huge kaupapa – unforgettable.”

The daughter of the Māori King, Kiingi Tūheitia Pōtatau Te Wherowhero VII, Nga wai is the most recent appointee to the Waitangi National Trust Board, but

her connections to it stretch back generations and beyond its origins.

She picks up the thread of connection in the 1850s with the formation of the Kiingitanga itself, a movement founded on a principle, amongst others, of kotahitanga – to unite iwi across the motu. When the trust was established in 1932, the Māori King was among its first members, and the board position now held by Nga wai – representing the Māori people living south of Auckland in the North Island – went on to be occupied alternately by members of the kāhui ariki and the Te Heuheu lineage.

“I feel this is an important role, and it represents a lot of people. I’m using it as an opportunity to learn and create different ways of connecting people – much like our tīpuna and absolutely aligned with that notion of kotahitanga.”

While helping to direct the care and preservation of one of the nation’s most important historic sites is part of her role on the Waitangi National Trust Board, Nga wai says heritage preservation is a strong theme running through her wider mahi.

Her main day job is overseeing the Kiingitanga collection, which contains more than 3,000 taonga.

“We have taiaha, patu, whāriki, korowai, diaries dating back to the 1800s, chandeliers, gifts from across the Pacific – it’s a vast array. These taonga contain significant kōrero and heritage that pertains not only to Waikato but also across the motu and the wider Pacific, and we want to capture and share that.”

She and her partner also own a business that offers tours of the Waikato Wars battle site of Rangiriri, which they have run for more than three years. And she is a highly experienced kapa haka tutor.

“I’m very involved in my culture and my heritage. It’s how I’ve been brought up, it’s who I am, and it’s how I choose to live.”

At 25 years old, Nga wai is the youngest member of the Waitangi National Trust Board. She says she’s grateful for the support she’s received as its newest member, but that her youth is also an asset.

“My hope is that I can bring the views of my generation to the board and that future focus will influence the board’s decisions in how we care for the land.

“Prior to coming into this position, I really didn’t know much about what the Waitangi National Trust did, or that there was this huge estate at Waitangi that belongs to the nation. So I’d really like to look at how we can raise the profile of the trust and its kaupapa, particularly among my generation, because it’s a nationwide kaupapa, and an important one.”

While a Covid-19 scare meant she wasn’t able to travel to the Waitangi Day 2021 commemorations, Nga wai says she’s hoping to be there in 2022.

“I definitely see myself participating in all the traditional events of Waitangi Day, and immersing myself in the experience. I’ve been brought up surrounded by my culture, I thrive on it, it’s who I am, so being involved in the day will be another way for me to recharge my batteries.”

member since 2016 and chair since 2018

The vast body of water surrounding the Waitangi National Trust estate is but a trickle where the Taumarere catchment begins at Mōtatau, the home of Pita Tipene.

But the small Northland community has very close connections, explains Pita, to Te Pitowhenua/the Waitangi Treaty Grounds and particularly one of its most iconic buildings –Te Whare Rūnanga.

In the years leading up to the 1940 centenary of the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi, the MP for Northern Māori Tau Hēnare, of Mōtatau, and Minister of Māori Affairs Sir Apirana Ngata proposed the construction of Te Whare Rūnanga as one of the contributions to the centenary commemorations.

Te Whare Rūnanga was to stand next to the Treaty House as a tangible symbol of partnership and nationhood.

“Those leaders asked our Ngāti Hine people to mobilise and provide the timber, so people like my dad, Kohekohe Tipene, set about the task. There are even photos of my dad pit-sawing the timber,” says Pita.