THE HEALTH HUMANITIES JOURNAL

UNC-Chapel Hill | FALL 2022

MISSION STATEMENT

The Health Humanities Journal of UNC-CH aims to inspire and facilitate interdisciplinary thinking and collaborative work while developing and embodying a variety of ideas that explore the interface between arts and healing. This publication allows for dialogue, meaning-making, and multiple representations of the human body, medicine, and illness.

To learn more about the publication or to submit, visit the following website: https://hhj.web.unc.edu.

DISCLAIMER

The Health Humanities Journal of UNC-CH adheres to legal and ethical guidelines set forth by the academic and health communities. All submitters maintain patient privacy and confidentially according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and The Health Humanities Journal of UNC-CH do not endorse or sponsor any of the viewpoints presented in this journal. The opinions presented in this journal are those of the corresponding authors.

SPONSORS

The Health Humanities Journal

of The University of North Carolina

Fall 2022 exploring illness, caregiving, & medicine

at

Chapel Hill

Editor-in-Chief | Design & Layout Editor

Managing Editor

Art Director

Treasurer | Editor Secretary | Editor

Marketing Director

Podcast Editor

Assistant Podcast Editor

Editorial Team

Iris Kang (Psychology: Class of 2023)

Miranda Almy (Medical Anthropology: Class of 2023)

Ellen Hu (Biostatistics, Mathematics: Class of 2023)

Malik Tiedt (Nutrition, Medical Anthropology: Class of 2023) Su-Ji Cho (Neuroscience, Psychology: Class of 2023)

Kamyrn Mcdonald (Psychology, Interdisciplinary Studies: Class of 2023)

Parker Savage (UNC School of Medicine: Class of 2024)

Kate Brown (Psychology: Class of 2023)

Website Editor Hannah Koceja (Psychology: Class of 2024)

Editors

Tess McGrinder (English: Class of 2023)

Penelope Alberdi (Psychology, Asian Studies: Class of 2024)

Iris Chang (English, Biology: Class of 2025)

Lydia Meltonlane (Psychology: Class of 2025) Rotem Olsha (Neuroscience: Class of 2025) Maura O’Sullivan (Psychology, Disability Studies: Class of 2025)

Graduate Editors

Cate Hendren (UNC School of Medicine: Class of 2023)

Olivia Davis (UNC School of Medicine: Class of 2025)

Anameeka Singh (UNC School of Medicine: Class of 2025) Jacqui Zanders (UNC School of Medicine: Class of 2025) Kaitlin Joshua (UNC Department of Sociology: Class of 2026)

Faculty Advisers

Jane F. Thrailkill, Ph.D. (Co-Director, HHIVE Lab | Department of English and Comparative Literature)

Kym Weed, Ph.D. (Co-Director, HHIVE Lab | Department of English and Comparative Literature)

Table of Contents

Editor's Note

crisis in calabash Small Cell Carcinoma Signing on to Psychoeducation

My Body Is Under A Constant State of Stress Kamala’s Mind: On the Wonder of Thoughts These days

Fear of Failure

His Appetite for Self Destruction— “We Eat, Love, and Die” The Panic Game valēte (Pandemic Blues) At the Table Open Heart Plath, and other Poems from the Psych Ward Cancer

I Hope I Never Wear a White Coat

Barriers to Providing More Equitable Student Health Services you could have killed yourself Shades of a Mind Just Like Mom

Iris Kang

Patricia Ndombe Amanda Jean Nemecek Christian Sodano Teresa Ruiz Vazquez Harini Sridhar Patricia Ndombe Ryan C. Higgins Aaron Hahn Kimberly Real Ariadne Tsoulouhas Sarah Ball Nathan Cannon Ash Chen Lai Jiang Joanmarie Lewandowki Madison Shaffer | Austin Geer

Patricia Ndombe Aaron Hahn A.H. Stepp

Art by Ellen Hu

6 8 10 11 12 14 16 17 19 20 22 24 26 27 30 32 33 36 38 40

Dear Reader,

Can you think back to the last time you had true rest?

Until recently, my go-to definition of “rest” was nothing short of Geronimo Stilton’s weekly wind-down: taking a “squeakalicious” pink bubble bath with a cheddar-frosted smoothie in hand. Under this main go-to were also things like huddling in a puffy comforter fresh out of the dryer, chugging vitamin C, and reading cartoons between classes.

But this semester, I’ve been pushed to ponder the true meaning of “rest.” In this productivity-driven world, we often picture bubble baths, retail therapy, and 2-hour naps—or, perhaps more appropriately, the 5-minute power nap—as modes of rest. Essentially, rest equals brief time away from academic and work obligations to get fueled for the next task. And I’ve largely agreed with this view. After all, who doesn’t want some time to unwind and give their body a wellearned trip of relaxation?

After overworking all throughout high school and college, I could feel the taxing effects on my physical health more acutely this semester. So, I resolved to get some rest. Long gone were the days of neglecting my health: I would aim to one day arrive at that place of recovered health.

So, I took on my go-to definitions of rest each day. And my health did improve quite a bit. But despite all these physical improvements, I still felt...drained. Internally—somewhere beyond the physical—I carried the perpetual baggage of exhaustion. And that got me thinking, “Are these naps and bubble baths really it?” To answer that question, I had to travel back in time and remember the last moments when I had actually felt at rest.

Ironically, the memories of when I felt truly rested were often the ones when my body felt most tired. What a paradox, right? These were things like playing Marco Polo with my elementary school buddies in the 110-degree Arizona heat (and getting cucumber face packs by our amused moms afterwards). Or taking in the emerald green view at the peak of Hanging Rock in my sweat-soaked T-shirt. And maybe most vividly, staying up until 1 AM, brazenly slapping cards down and hoping my friends wouldn’t call baloney sandwich on my plays. The next day, I would wake up feeling sluggish or with a giant red sunburn burgeon ing across my face. But, I felt...rested. “At peace” is the real word for it. There was always a tight ball of warmth deep in my soul that I never could find elsewhere. And no matter how many bubble baths I take or cheddar smoothies I drink, I don’t think I will be able to reach that same place.

6 Editor’s Note

So, I wonder: have we limited our definition of “rest” to the confines of our ev er-striving, output-oriented world? Bubble baths are great. Vitamin C and taking downtime to read cartoons are essential for maintaining health. But, what if rest isn’t goal-oriented?

The Fall 2022 issue, in many ways, is unlike previous editions that have graced the shelves of The Health Humanities Journal. An overwhelming majority of pieces focus on the mental arena of health, taking a front seat to the physical. Of ten, it’s not bodily ailments that have led these stories down a dark path, but it’s dealing with the pressures of the broken world that have led to burdened minds and, subsequently, a struggling physical body. Individuals struggle to make sense of how to cope with loss, panic, hardened institutions, and hopelessness. They are overworked, tired, and desperate for reprieve. And they all call us to ponder a central question: how do we tease apart the world’s “cures” for our exhaustion from the actual rest we seek?

In each of these pieces, I was humbly taught that rest is more like a bubble of timeless peace rather than a path to the goal. So often, we are striving for the next best thing and thinking “If only I could get over to that ledge, I’ll be more content.” And this mindset has seeped into how we view rest. Rest is no longer a break from the world to take care of our inner health. It is more often than not a means of bandaging our bodies to perform better in our jobs, school, and greater society—a pitstop we occasionally fuel up at to arrive at the next destination. And we still end up carrying the heavy burden of exhaustion despite our efforts, understandably wondering why we feel like we’re running on empty.

I hope that as you read this issue, you will be reminded that rest might be in this very moment. Perhaps rest looks like soaking in the present and casting away worries about how to get better or achieve a physical destination. Perhaps we don’t need to rest to get somewhere: maybe that “somewhere” is here. And all we must do in our times of true rest is just be—no goals, destinations, or next best things. Just enjoying the scenery here.

Thank you to our sponsors for supporting these important conversations around health. A big thank you to Miranda, HHJ’s first mangaging editor: you have truly deepened my appreciation for the power of teamwork. I’d also like to recognize our advisers, Dr. Thrailkill and Dr. Weed, and the editorial staff for their unwav ering dedication and work in producing the best version of this journal we could have ever imagined. Lastly, thank you to the authors who have filled our pockets of wisdom with so much to reflect and ponder over. With this Fall 2022 issue, I hope you will find inspiration, exploration, and, ultimately, a call to rest.

- Iris Kang Editor-in-Chief

7

crisis in calabash

Patricia Ndombe

My long hair has lost its life, straight as straw. It straggles down my face in knots. My seared skin, shining. My head sways, too heavy for me. I am tired. someone scratches.

I crawl in, curl up against the curve of my calabash. A strong empty wind kicks me there. I rip the word away from me, throw it down. I crawl on my knees, collapse to cry for a straw bed for some straw breath, or a raw death to keep me here.

My calabash is caving in, surrendering to new cracks of light, new cracks of life. I can’t reconstruct. I am consumed. someone bites.

8

I crawl in my calabash, watch it decompose, steal a sliver of slight sour for more strength. I stand up, breathe for sacrifice, bury strength. I pick up the word, beg my throat to take and swallow it.

someone scratches. someone bites. someone calls me mom.

This poem borrows language from Yvonne Vera’s novel, Nehanda.

Poem Statement crisis in calabash centers around what it truly means to be a mother or a moth erly figure. It speaks of mortality, perseverance, cost, and sacrifice.

—Patricia

9

Ndombe is a second year graduate student in the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing program (with a focus in Poetry) at North Carolina State University from Knightdale, NC.—

Small Cell Carcinoma

Amanda Jean Nemecek

After your diagnosis, I turn to the primary sources because that’s all I know to do. With trembling hands, I name your disease— small words, dead language. No cure.

There is only treatment: drugs with names that sound like incantations, like final prayers offered up to our lady of the labs.

I track its path through blood and bronchi: its origin, its invasion. Your inevitable end. Metastasis; displacement. I lose my spot on the page.

“Knowledge is power,” except for right now, when I am left staring at stark words on a website, frantically searching for one last seed of hope.

Maybe if I know more, it will be better. You will be better. Maybe it will make this easier. Maybe it will help me accept that one whispered word.

—Amanda

10

Jean Nemecek is a first year medical student at the UNC School of Medicine from Raleigh, NC.—

Signing on to Psychoeducation

Christian Sodano

There’s an eerie air to first Zoom meetings. More, when prompted greetings reveal diagnoses we’re used to keeping behind closed doors.

Worse, when the ever-chipper hosts can’t read the breakout rooms of depressed adults who told themselves, after the last attempt, “No more.”

—Christian Sodano is a junior majoring in Neuroscience with a minor in Computer Science at UNC-Chapel Hill from Holly Springs, NC.—

11

My Body Is Under A Constant State of Stress

Teresa Ruiz Vazquez

“Stress is the nonspecific response of the body to any demand made upon it...In other words, in addition to their specific actions, all agents to which we are exposed also produce a nonspecific increase in the need to perform adaptive functions and thereby to re-establish normalcy. This is independent of the specific activity that caused the rise in requirements. The nonspecific demand for activity as such is the essence of stress...Complete freedom from stress is death” (pp. 27-28; 32) - Stress Without Distress, Book by Hans Selye1

The idea that stress is not always negative, that extremely pleasant experiences can provoke a similar stress process as extremely unpleasant ones, seems false.

My body is under a constant state of stress as I enter into my final year of undergrad and my looming future becomes less distant—my body refuses to feel pleasant. I massage the constant ache within my cranium as I spend too many hours switching between tabs that show different answers to the question of what should come next.

For me, the most fitting word for “pleasant stress” is relief—the complete removal of unpleasantness that comes with stress as I know it, a release of the tension that prevents my body from feeling relaxed.

Perhaps I should feel relieved. At the start of my freshman year, my femur was still healing from a near complete split after a car accident—my closest encounter to death and last moment of a carefree summer. Only a couple of months later, the open world shut down, reminding me of the fragility of peace. I was once again faced with the fear of death when my entire family became infected with a virus that had no cure. Recovery was painful, not because of the symptoms, but because of the physical manifestation of stress regarding the unknown: would we survive when hospitals had no oxygen, no beds, and no guaranteed protection against death?

We recovered, but the lingering stress of imagining a solitary death and the poten tial reduction to ash of my loved ones made my body curl into itself, repelling the touch of anything without sanitation. Isolation was my response to the constant stress of reinfection.

But I did not successfully avoid the hospital and its stigma of being an infection zone. My mother’s gallbladder stopped functioning, putting her body through 1 Selye, H. (1974). Stress Without Distress. Signet.

12

unbearable stress as she withered in pain while we rushed to the hospital, desper ate. In the cold November air, I guided my mother up a railing to the emergency department’s entrance, feeling her painful quivers. My own body replicated her movement, but I quivered with a different pain. I wondered what would happen if there were no beds, if my mother had to sit with her pain until her body could not take it anymore and stress made itself the perpetrator of my mother’s death. She survived, but recovery is not peaceful when the body is still fearful of relapse.

My own stress is heightened when I recognize that health is a state of being able to quickly deteriorate under the right circumstances and not always able to be con trolled.

What does it mean to be well? The state of normalcy that Hans Selye describes— the homeostasis the body attempts to replenish after stressful events that can be either pleasant or unpleasant—is a binary of how our body reacts to experiences that call for some form of bodily response. But for me, stress is not binary. It cannot be reduced to a finite beginning and ending, existing within a scale of extremely unpleasant to extremely pleasant. The experience of stress, depending on the per son, can render different outcomes.

What is extremely unpleasant for me is how I can become utterly subject to my body’s stress response. I struggle to function with the mentality that I am going to succumb to the pounding of my heart. I am afraid that my fight or flight response will cause me to fly away from situations that I know I can conquer.

Perhaps I have never felt stress as a state of extremely pleasantness because I am an individual carrying a legacy of hardship. As a society, we have better definitions for the body’s reaction to pleasantries. Pleasure and joy are experiences that invite the body to feel positivity; so, can stress really be a response of the body to any demand?

Selye suggests that the body’s only escape from stress is death. But my own ex periences with stress have intersected with my fear of death itself and its finality, followed by the ambiguity of falling apart when faced with unpleasant experiences. Yet, this is perhaps solely my own body’s reactions to the realities that have been forced upon me. Stress is the best word I can use to describe feeling like I am on a never-ending treadmill of uncertainty, one where I am unsure of how to establish normalcy because I am not sure my body has ever been in homeostasis. Often, it feels like it is just shy away from “I can be relaxed just in this moment because there is no imminent chance that something could go wrong.” The reality is that I contin ue to seek a state of normalcy. I wish to adapt to stress while navigating this world, when my heart threatens to pound out of my chest and a throbbing headache from deep in my cranium forms. To be well, for me, is embracing my versions of stress.

13

—Teresa Ruiz Vazquez is a senior majoring in English and Political Science with minors in Medicine, Literaure, & Culture and Latino/a Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill from Dobson, NC.—

Kamala’s Mind: On the Wonder of Thoughts

Harini Sridhar

They tell me that the body is a text, inscribed with narratives that exist across time and space. In a past life, I must have been Kamala, resting on a lotus in the murkiest of waters, with the power to see beauty in the things that repulse me.

Kamala and I are tantric goddesses. We embrace illness, our dark skin, and all castes. Our stories of rising from the ashes embody resilience; yet, they often go untold.

I ask her, what does it mean to be a woman, with a mind that wanders far? How curious is it for brilliance to coexist, with obsessive compulsive disorder, with bipolar disorder, with psychosis?

Sipping on tea with Kamala, we share a plate of petits écoliers, and my breath brings me back to a younger version of myself.

I am a thinking thing: a thinking, breathing, sensing, imagining thing. My thoughts love to play with their power, molding over time, to the judgment that surrounds me, overshadowing my liberated, sensual spirit. How am I supposed to sit with the misfortune, that I will never fully know when these thoughts will end, when all I want is control? I want to be nothing, to feel nothing. But for so long all I have wanted was simply to find who I am and to feel something.

14

In the middle of the night, I discover wide-awakeness. The suffering I open my eyes to resonates at a new frequency.

Kamala and I channel truth into our dance, our painting, and our poetry. I craft in disaster like the martyrs who came before me, from Kahlo to Kusama.

Kamala, you are my mind’s Wise guardian. My Emotional mind is under siege by deep sorrow and rage. Logic, facts, and reason colonize my Rational mind. Journeying with you means I am accompanied between the extremes.

As I lie here in this bed that is not my own, I see the beauty in becoming lost and then finding sound.

—Harini Sridhar is a second year medical student at the UNC School of Medicine from Chapel Hill, NC.—

15

These days

Patricia Ndombe

These days I’ve been reduced I eat of dreams of drugs of my own dust dirt and dander dancing drifting descending from my dingy hair Deliberately the hospice nurses haven’t bathed me haven’t changed my adult diaper much since I came but they needn’t bother

I don’t have the drive for it either I haven’t heard much from You these days but I’ll leave the door cracked open Come back to kiss me and bless my peppered hair my speckled scalp Don’t mind the smell Come back to whisper Well done My good and faithful servant Enter into the joy of Our lore I’ve called for my cremation

I’m sorry I couldn’t last forever for You You can find a new poet and let me go now I’m glad you came I’ll think of You as soot rises around me and I’ll ask one last time as I lie Was I the blackbody at the tip of your candlestick Was I the scent of permanence pooling by

This poem borrows language from Howl by Allen Ginsberg.

Poem Statement

These days questions and explores how to determine whether a life has been well lived. It converses with mortality, eudaimonia, regret, hope, and surrender.

—Patricia Ndombe is a second year graduate student in the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing program (with a focus in Poetry) at North Carolina State University from Knightdale, NC.—

16

Fear of Failure

Ryan C. Higgins

Tick . . . tick . . .

BOOM.

The explosion.

It was only inevitable. Months of anxiously mirroring his every move, hours spent meticulously preparing pre-visit notes, and late nights studying for every possible question that could be thrown my way would never suffice. And so, I stood there withstanding the barrage—frozen in my shoes, eyes to the floor, fists clenched underneath my white coat.

His arms flung up and his eyes rolled back as he scoffed, “the yolk sac!?” He stamped around laughing incredulously at my sheer naivety. Though I tried to direct my gaze downward, I could feel the eyes of the nurses as they sat glued to their desks, watching the events unravel before them.

Sensing a pause in his insults, I attempted to salvage the situation.

“I’m sorry, I will look it up.”

Here came the aftershock.

The verbal onslaught continued as he scolded me for “my generation’s” use of technology as a crutch. The fuse had already been lit. There was nothing I could do.

As I held back my emotions, I felt the flashbacks coming on.

Pouring down rain on a cold November night, I stood in the middle of the field. My white jersey clung to my stiff body as I took the verbal onslaught. Avoiding eye contact, I held back the tears. As the coach’s insults were hurled my way, each teammate watched in silence, too petrified to come to my defense.

17

“Is it the yolk sac?”

I didn’t blame them; we all knew the routine, even as 10 year old kids. We all knew the ramifications of one bad pass, one missed tackle, one wrong decision. Groomed through years of public humiliation, our success hinged on the man whose attacks reverberated across the field that night.

What has changed?

With 15 years of education, multiple 9-5 jobs, and countless sacrifices, I still remain glued to the floor in fear. Is this the recipe for success? Without countless years of psychological abuse from coaches, would I really have been able to play collegiate soccer? I would argue that the financial scholarships and structured framework that collegiate athletics provided paved the way for my pursuit of medical school. Is withstanding this doctor’s insults the key to my success?

Just as the childhood fear of my coach’s outbursts made me a better athlete, the fear of that physician’s humiliation made me a more knowledgeable medical stu dent. To this day, I will never forget alpha-fetoprotein is not only produced from the yolk sac, but also the liver.

But at what cost?

The improvements I made from enduring years of mistreatment as a young child were not driven by a motivation to succeed, but rather by the fear of failure. I will never forget those sleepless nights before game day, anxiously thinking of all the mistakes that could be made. As this mindset slowly chipped away at my self confidence throughout my childhood, it ultimately affected my love for the sport. Success on the field was no longer met with a sense of joy but instead, relief.

Once again, I am met with the same situation: motivated by fear rather than success. Over the course of months spent at this physician’s hip, I found myself fixated on avoiding mistakes instead of celebrating patient wellbeing.

I am not alone with these thoughts. Countless stories from residents seem to echo mine as they detail the ruthless nature of their respective programs, de scribing some attending as being notoriously hard on residents. With the future painted in much of the same way as the present, I will inevitably face many more of these “tough” attendings. This leaves me with a choice: Do I want to be a physician groomed by the fear of these preceptors, motivated to succeed by the fear of failure? Or, do I want to be courageous enough to accept the inevitable mistakes I will make, the social and bureaucratic ramifications that may come, in pursuit of the ultimate success of my patients?

—Ryan C. Higgins is a fourth year medical student at Penn State College of Medicine from Issaquah, WA.—

18

His Appetite for Self-Destruction— “We Eat, Love, and Die”

Aaron Hahn

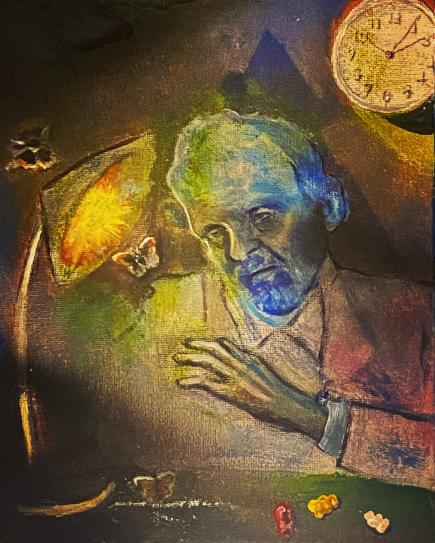

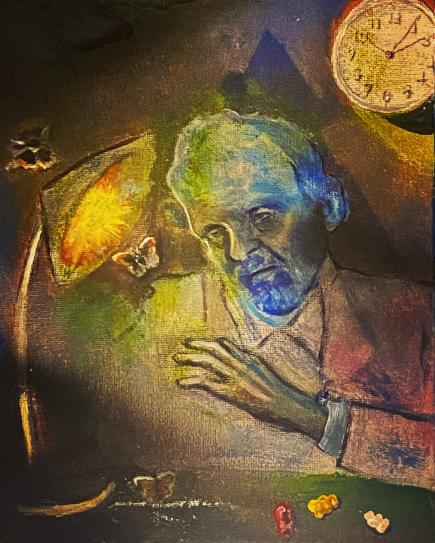

Addiction is a prevalent mental disorder that affects a person’s brain and behav ior, leading to the person’s inability to control his or her life. My painting uses the metaphor of moths to represent those who are blinded by their addiction to ill fated pleasure and love that ultimately destroy themselves. As the moths are reckless ly flying into the fire-like lamp on the desk at midnight, an old man stares at the suicidal insects, symbolizing his complex reflections on the tragic sequence. The colorful gummy bears on the desk hint at his penchant for unhealthy instant gratifi cation. The streak of white on the table further establishes that he might have been abusing substances. As his face is slowly fading into the ghastly blue of depression in strong contrast to his rosy suit jacket, the man realizes that he is all by himself in the lonely dismal room of melancholia. The continuum of this psychological machinery resonates with me like misfired shots at 3AM.

—Aaron Hahn is a graduate student studying Education at UNC-Chapel Hill from Seoul, South Korea.—

19

The Panic Game Kimberly Real

[Loading...]

Hello, player!

Welcome to The Panic Game.

Imagine you’re fine when suddenly you’re not.

Your log file loses capacity, and everything feels hot. There are tears in your eyes, but you can’t cry.

You feel like you’re choking, you’re sweating.

You’re breathing very fast, and you can’t manage to stop. Your heart is in your stomach, and your stomach is about to drop.

Nothing feels real until after you’re done. So, are you ready? Does this sound like fun?

[Loading...]

Greetings, player!

Let’s play again.

I’ve taken something from you. Something you’ll miss, like a friend. But, don’t panic.

You’ve got this, you’re doing great. If you can’t figure it out, there’s always sleep for an escape. Wait, you’re not doing well?

You feel like you’re falling? Well, it’s too late to quit, we’ve already started. Try to focus.

Do everything you can. Search your surroundings for clues until you feel better again. Quiet down. You’re being a bit loud, you know?

You seem okay, you seem fine. Do you want to play another round?

20

[Loading...]

Hi, player!

It’s been a while. I’m not going to tell you the rules, you’ll have to struggle to find them. You’re resourceful, you’ve got this. But, don’t take too long, don’t be obnoxious.

Look at me when I’m talking! Don’t you want to learn how to play?

Are you fine? Are you breathing okay? No? Calm down. Breathe. Stop crying. Not working? Then do it again.

This is pathetic, and you’ve ruined this now. My good time has been spoiled by your need to calm down. Is it really that hard?

In for 4. Hold for 7. Out for 8. In for 4. Hold for 7. Out for 8. In for 4. Hold for 7. Out for 8.

Oh! Look, you’re good now! It’s come to an end. When you’re free later, let’s do this again!

—Kimberly Real is a sophomore majoring in Biology and Exercise & Sport Science at UNC-Chapel Hill from Salisbury, NC.—

21

valēte (Pandemic Blues)

Ariadne Tsoulouhas

Window in the sky opens to flat-lipped saints

One tries to pull up a ladder but faints

Bare bodies roll at the gold-winged gates

Rivers run red, dry, ready to suffocate

A glittering goodbye on a pyre of dead weight

Stomach acid churns to swallow the sweat

Seeping out from the pores of an old man’s regret

Even though he says to himself, “I’m all set.”

Suffering halos seek sacred urgency

Led by misguided white light fervency

Black bullet pills crumble in distress

Dissolving and dancing in mourning undress

Delicate dreams die by deathless machines

The question of ends justifying means

Lying in wait for pristine vaccines

Leathery flesh split open for passage

Gives up the ghost to be rid of baggage.

Somber siren sings of St. Martin’s Land

Half-grown faces hidden in hypogeal sand

Beasts boiling blood for the red right hand

Astral catastrophe whispers to wind

Both hands bound with rope of fire dimmed

Whether bells toll on Earth or in the sky

Down below or beyond that known and why All is the same in this cosmic goodbye.

22

Poem

Statement valēte, or “farewell” in Latin, was written at the height of COVID-19, and I consider it a poetic time capsule of my pandemic experience. Throughout, I explore apocalyptic, religious, and folkloric themes, all in an effort to grapple with the world-shifting – at the time, seemingly world-ending – ramifications of the pandemic. The dystopia of quiet supermarkets, empty schools, and overflowing hospitals created a strange sort of collective anxiety – an anxiety about having to confront the vulnerabilities of one’s own body and about potential encounters with death (whether one’s own or that of loved ones). The piece also touches on police bru tality and the violent manipulation of bodies at the hands of the state; the preponderance of technology (Zoom and other mediums) at the advent of the pandemic, which put countless individuals’ dreams on hold; and the lives of blue collar and essential workers (who might not have had the luxury to quit their jobs or pursue other careers) which were jeopardized for the sake of the economy – their labor, often unfairly compensated, was seen as a means to an economic end.

23

—Ariadne Tsoulouhas is a second year PhD student in Religious Studies (Ancient Mediterranean Religions) at UNC-Chapel Hill from Cary, NC.—

At the Table Sarah Ball

The air feels heavier under that kitchen table light. The single-bulb fixture hangs low, threatening to crack our heads if we stand up too quickly after dinner.

The table shapeshifts on occasion; its offerings tend to oscillate between wrin kled newspapers and tablecloths dotted with dusted-off china. Only the New York Times makes it here; the local, crime-focused Poughkeepsie Journal—the ‘blood paper,’ as my mother likes to call it—is relegated to darker corners.

To sit at the table is to pause in its presence, to let eyes widen and focuses nar row. Its surface is chipped and charred, its sharp edges softened. We’ve wrapped presents and torn them open here, poured wine and pulled up chairs. When the oven broke, we languished here, cursing the Christmas dinner that remained raw for hours.

There is something purposeful about the way the chairs don’t quite fit under the table, the way their backs force occupants to sit up a little too straight. It is a liminal space, a sense of restlessness pervading its rituals.

It demands.

The light dims but does not extinguish, keeping plates illuminated, justifying stares. Shadows are not cast quite far enough to hide meals poked and prodded, flattened beyond recognition. Empty plates are cleared–full ones too. PediaSure is choked down under watchful eyes when dinner can’t be stomached, the dim mer now on low. You cannot just get up; you must eat.

For a long time, that table felt like an altar to which I could not kneel. I should have bowed my head and held the hands of my parents, thanked them for the blessings in front of me. I should have confessed and hoped to catch forgiveness like rainwater in my outstretched palms.

But my hands could not be held, as they were busy under the table, wringing opposite wrists to ensure that their diameters hadn’t widened. My head felt too heavy to bow, my knees too weak to kneel.

Someday the table would lose its prowess. It would be humiliating to come home from college for the first time and see how small it really was, the voices in my head laughing at the final punchline of so many of their sick jokes.

24

But until that day, I remained obstinate in my insistence that my behavior was only ever retaliation: the table had always struck me first. It was too severe, illuminating my every failure and insecurity. My resentment towards its rituals manifested itself deep in my abdomen, calcifying into something hateful and nauseating. This creature ignited a rage I had never seen in myself, an inconsol able anger towards the table, its food, and those who ate at it.

The creature hungered for emptiness, gurgled and groaned and screamed for nothing at all. For years I felt my best when I knew that I was hollow.

I found ways to avoid the table, taking up hobbies that bled into its holy hours. I was rewarded for my secret starvation with a persistently rancid taste in my mouth–something bitter and rotten. I began to stockpile mints to preserve some pride in my efforts.

Today I have forgiven that kitchen table. I have traced its wooden seams with trembling fingers, wondering if I brought upon so many of its wrinkles and knots. Children tend to do that, don’t they?

I still feel the ache for emptiness from time to time; I still keep mints in my back pack. I don’t chew them feverishly anymore, though. Instead, I close my eyes and let them shrink slowly, like little prayers dissolving on my tongue.

25

—Sarah Ball is a sophomore majoring in Health Policy & Management at UNC-Chapel Hill from Poughkeepsie, NY.—

Open Heart

Nathan Cannon

While admittedly visceral and gruesome at first glance, this still frame of an openheart double valve replacement surgery at Tenwek Hospital in Bomet, Kenya captures both rawness and grace. Our eyes are simultaneously drawn toward and repelled by the epicenter of this photo, which represents something starkly unnatural: an opened chest, beating heart, plastic tubing, and stainless steel retractors held by delicate, gloved hands. This life-saving procedure is frequently performed in rural Kenya, where many young adults have defective heart valves due to preventable childhood rheumatic fever. Tenwek hosts a resident training program in these procedures and has received international acclaim for their efforts to counter this disease in their community.

Picture obtained with patient consent.

—Nathan Cannon is a third year medical student at Penn State College of Medicine from Rochester, NY.—

26

Plath, and other Poems from the Psych Ward

Ash Chen

Content Warning: This piece contains references to suicide, self-harm, and psychiatric institutions. Reader discretion advised.

“Welcome to the Peanut Gallery,” grinned a thirteen-year-old girl over our hospital breakfasts as soon as she identified me as the newest arrival. This was her sixth stay at the adolescent psych ward, and her parents were sending her to a long-term facility after. It was my first and only stay, and I count myself one of the lucky ones; this respite from the pressures of polite society, a virtual senior year, and early college pulled me back far enough from the ledge until I learned to climb down myself. I was seventeen and driven to self-destruction, then driven to the ER by my best friend. It was a relatively short stay, one I had waited two days and a night in the freezing ER for. The staff grimly told me that every psych bed in the city’s hospitals was full, and the influx of pediatric patients since the pandemic had only worsened the strain on an already tenuous system. I made idle chatter with the nursing students in gray scrubs about the ransomware attack that hit our college last week, throwing my already shitty online classes into madness.

The psychiatrist laughed when I described my first suicide attempt, which I hadn’t even considered a real attempt. Granted, it is funny in hind sight—a sixteen-year-old who had never touched anything but a joint at the skate spot and the occasional sip of her mother’s wine —getting so fucked on Jack that she heaved her guts up before even opening the Tylenol. I’m sure it was even funnier to a doctor who deals with violent and abused adolescents battling more serious addictions than self-harm. The suicidal ones were the “tame” ones. The seven-year-old boy with explosive anger was more his interest that week. So I told myself, once again, that my pain was inconsequential next to all the pain that existed outside me. It must be true, because this time, the thought was backed up by an M.D.

I don’t find it funny anymore.

“You’re a cutter, I see,” were his first words to me as I perched on the edge of the plastic chair in front of his desk. He looked me in the eye a few times, but not as much as he looked at his computer monitor or at the wound that reopened when I stretched wrong. In the fifteen minutes we spoke, he called my mother and put her on speaker, explained in patronizing terms what was wrong with my head, upped my meds, and recommended she drug test me regularly. He didn’t see me again for the rest of my stay.

The nurses and social workers, at least, did their best. Group therapy was always stilted, our responses awkward and contrived, and the essential oils

27

and anger management worksheets did little for me. I talked to another ward veteran, the only patient my age—eighteen—on the pediatric side because he was still in high school. He confessed he hadn’t slept well until his roommate was dis charged, and understandably so—he’d threatened to suffocate him in his sleep.

“Where’d you get that nicotine patch?” I demanded at breakfast, looking at the square a nurse had stuck on his arm after watching us swallow our morn ing meds. I didn’t want Prozac—I wanted a Marlboro. He shrugged.

“I told them I was a smoker on my intake.” I later learned he preferred Lucky Strikes.

“I shouldn’t have lied about that,” I grumbled. The caffeine and nicotine withdrawals were threatening to split my skull open. He only nodded in agree ment and we swapped juices, my orange for his cranberry. After meals, they checked our trays, because they threw the ED patients in with the rest of us. My girlfriend at the time was recovering from anorexia, and I recalled how she told me a nurse once made her drink salad dressing so she wouldn’t be marked ‘non compliant.’

When I complained of the itchy paper scrubs, he explained that it was so any bleeding would be quickly identified. We filled out our therapy journals with colored markers (no sharps allowed) and modeled the good behavior he prom ised would get us out sooner. Good behavior, in this case, meant needing noth ing and wanting nothing. We chatted about our worried girlfriends we weren’t allowed to call and how it wasn’t working out for either of us, and offered one another adolescent dating advice. We were all instructed against exchanging per sonal or contact information. Of course, the morning he was discharged, I wrote my Instagram handle in red marker inside the journal he was taking with him. We broke up with our girlfriends, hooked up in my car a week later, then never spoke of it again; we only talked when we needed to process what happened between those white walls. The last I’d heard from him, he’d joined the military.

“I mean this in the best way possible, but I never want to see you again,” my favorite nurse had said as she hugged me on the way out. I swore she wouldn’t—not in this hospital, anyway. I’ve upheld that promise, but while that place may have protected me from myself for a short stint, it didn’t help. All it did was cost me my full ride to Amherst College and my chance at valedictorian. All it did was show me what the consequences are for being unwell.

I ran into these consequences again my freshman year when one of my best friends had to be walked to the campus health clinic following a rash of student suicides, where they refused to tell us if she was even safe. We met again that spring when my then-boyfriend was admitted to the same hospital that I was in; when I rushed home to visit, the psychiatrist had drugged him up so heavily that neither his mother nor I could recognize him. The doctors and nurses talk ed circles around him, never giving a straight answer, and tried to extend his stay when he became frustrated. My ex-girlfriend from that senior year was kicked

28

from a hospital’s ED program when her insurance stopped wanting to pay.

It took me months of therapy and self-reflection to understand what my experience and those of my friends’ meant in the overarching structure of mental health and treatment among college students. And yet, the conclusion I came to was both startling and entirely obvious at once—none of this was treatment; it was containment. Being called an addict to your face is not treatment. My psy chiatrist did not consider that if my meds were dosed properly, which he would have known by simply asking how I felt on them, I might not have felt the need to get high enough to keep me from opening my veins. No one considered that if mental health treatment for students was accessible, my friend might not have left her dream school. If my boyfriend wasn’t falsely accused of using drugs, if my girlfriend hadn’t had to fight her insurance company for her treatment...well, you see where I’m going with this.

What you don’t see is the Peanut Gallery restrained behind padded walls, threatened with involuntary holds. What you don’t see is the person inside the patient, under the paper scrubs and rubber-soled socks, behind the lies we learned to tell ourselves and our doctors to avoid this torture. What I wish we could see is more treatment and less of these errant institutional shortcomings. I want care to be available, and I want to be unafraid of it.

29

—Ash Chen is a sophomore majoring in English (concentration in Science, Medicine, & Literature) with a minor in Music at UNC-Chapel Hill from Charlotte, NC.—

Cancer Lai

Jiang

30

When does it stop?

Just a little over a decade ago, She was diagnosed with colon cancer. She has been compliant ever since, Taking many pills and giving up piquancy. Showing up to exams every year as if one day. But it ruined her thick puffy hair, Destroyed her ability to produce insulin, And now she has become hyperthyroidic.

Grandma is a devoted Buddhist, Never hurt an animal or ate beef or snail. One day she asked me, What wrong have I done, When will this punishment halt?

I had to tell her cancer can’t be cured, That her treatments can’t be paused. But not her not Buddha nor the doctors are at fault, Life goes on alongside those replication errors.

31

—Lai Jiang is a junior majoring in Biology at UNC-Chapel Hill from Michigan.—

I Hope I Never Wear a White Coat

Joanmarie Lewandowski

The question stuck with me throughout the month. Day in & day out, he arrived in a casual affair—never donning the prestige.

In he went, a fist bump followed by a confident but welcoming “What’s been going on?”

He listened as an old friend, asking about things beyond these four cramped walls. He was one you wanted to speak to.

When it came time for the work-up, he was exact. He used complicated words followed by relatable analogies. After the questions, he followed up with clear answers or a transparent “I’ll have to look that one up.” He was one you wanted to listen to.

In the hallways, he was as interested in his coworkers’ lives as he was in his patients’. He sought moments of small talk, only making requests when he had to. If everyone was busy, he would do it himself without complaint. He was one you wanted to work with.

In his office, he always had a story. A tale from residency about respect, loss, or achievement. Each one filled with a golden lesson. He was one you wanted to learn from.

I laugh at myself ironing my new white coat. So long I have awaited this crisp, bright cloak of honor. Now, I see it as a thin veil. Do you need a white coat to do these things?

I hope I never wear a white coat. I hope I don’t need to.

32

“I never wear a white coat. Why would I need to?”

—Joanmarie Lewandowski is a second year medical student at the UNC School of Medicine from Hendersonville, TN.—

Barriers to Providing

More Equitable Student Health Services: A Qualitative Analysis of Student Service Provision

Madison Shaffer & Austin Geer

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, ranked in the top 30 nation al universities, is often perceived as a “progressive island” of the South. However, there is a complex history of white supremacy, inequality, and oppression of people of color on its campus. Even though this institution attempts to promote equity and diversi ty, it is critical to reflect on how UNC’s history impacts today’s climate and culture. This historical context informs current structures and campus dynamics, including students’ perceptions and experience with health service provision. The literature has consistently demonstrated that students of color are less likely to seek help for mental health issues than their White university peers. UNC’s student health services hired us as health equity interns in the fall of 2021 to look into the experiences of Black, Indig enous and students of color (BIPOC) in accessing health services at UNC.

Taking into account the racialized history of UNC and the very public racial trauma of the last few years, we wanted to center the voices of BIPOC students and use their input to develop strategies for improving equitable access to health services at UNC. We intentionally centered core principles of equity in every step of our work. We grounded our project on the importance of understanding the structural, systemic, and historical factors that are the root causes of inequity. We also valued the perspec tives and knowledge of those most affected by inequity.

We evaluated staff and student perceptions of Campus Health, Counseling and Psychiatric Services (CAPS), Student Wellness, peer support services, and other programs such as the center for student success. To assess staff and students’ percep tions, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 12 staff and 21 students. The interviews included questions such as: “What do you think UNC could do to connect better, engage with, and support BIPOC students?” and “How would you describe the current state of BIPOC students’ wellbeing on campus?” Rigorous notes were taken during interviews, and we conducted a thematic analysis to inform our conclusions and recommendations. We also reviewed relevant Campus Health and CAPS policy through an equity lens and discussed how it could evolve to fit health equity values better. Underlying all this work was a critical reflection on the historical context, in cluding recent events such as the “Silent Sam” protests in 2018 and the highly publi cized racial trauma.

Our interviews revealed a demand for meaningful and intentional system ic improvement. Campus health staff said that they saw a balanced mix of students pre-pandemic, but within the last year-and-a-half, they have noticed an increase in BI

33

POC students seeking care. They cited the competitive academic culture of UNC, the current political environment, pandemic isolation, and racial trauma as factors that make the BIPOC student population more vulnerable and marginalized on campus. Staff from CAPS and campus health emphasized a need for increased collaboration between services; updated staff training; and further connection with diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging efforts on campus. CAPS staff, specifically, called to increase the diversity of service providers; add more identity-based therapy groups; and im prove outreach and engagement with the student body.

Undergraduate and graduate students identified the many misconceptions and noted a lack of transparency surrounding health services. Students felt distrust towards the health services, partially due to a lack of intentional communication and perceived representation within the service providers. Students had no free time to go to campus health due to packed class schedules and coursework. On weekends, the days when students would most likely have free time, there was a weekend charge for services. Every additional fee is a hurdle for students accessing care when it’s needed, particularly for students struggling with service accessibility and with limited finan cial resources. There were commonly held misconceptions about campus health and CAPS services that became barriers to access, such as therapy session limits and the cost of services. Students wanted intentional education materials that debunked these misconceptions and clarified what to expect from a visit to campus health or CAPS. They also felt they had been asked many times, through surveys, and hadn’t seen their suggestions applied. They called for increased communication around changes and updates made to service policies.

After reflecting on the themes from our interviews, we submitted a list of short-term and long-term recommendations to leadership within health services, all of which required cooperation and coordination between services, a plan with action able steps, funding, and the support of university leadership. The short-term recom mendations included editing the patient satisfaction survey; abolishing the weekend service charge; implementing updated and culturally-competent staff training, and building intentional communication campaigns to address student misconceptions. Long-term recommendations involve diversifying administrative oversight of services; improving staff recruitment; creating a multicultural health space in Campus Health; providing equitable pay for staff; and collaborating with campus services for a more efficient and effective student experience.

As health equity interns, we made evidence-based, long-term changes to UNC’s student health services that we hope will increase equity and accessibility. Campus health allowed us to update the patient satisfaction survey to include demo graphic information. This allows campus health to disaggregate the data by self-iden tified race/ethnicity, enabling the health services to identify disparities in student engagement and service satisfaction.

34

After we presented our findings to the campus health leadership board, they eliminated the $50-weekend health service access charge (see image). We had highlighted this charge as an inequitable financial barrier for marginalized student populations and believe this policy change will increase accessibility for students. We developed a brief presentation, laying out our process and findings, and our work was accepted to the 2022 American College Health Association annual conference. We presented our work to stakeholders in student health services across the country and won an award for prominent student voices in health. We will continue to work towards the long-term recommendations, but we know that these changes require campus-wide buy-in and continued student advocacy.

Ultimately, UNC-Chapel Hill is an institution with a very complex history for people of color. It is imperative to keep working to promote diversity, equity, inclu sion, and belonging in all spaces, especially regarding health services. To implement effective long-term change, we need continued equity-centered assessment of student health services, including Campus Health and CAPS. We will also need to apply this lens to the University at large, and take the time to have intentional conversations about UNC’s past and our collective goals for the future.

Additionally, as we both approach graduation, we are inspired and proud to know that there are many students at UNC who will continue this fight. The journey for equity is long from over, and we must continue to persevere to ensure better out comes for future generations of Carolina students.

—Madison Shaffer is a second year MPH student (concentration in Health Equity, Social Justice, & Human Rights) at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health from Silver Spring, MD.—

—Austin Geer is a senior majoring in Biochemistry and Neuroscience with a minor in Biology at UNC-Chapel Hill from Anderson, SC.—

35

you could have killed yourself

Patricia Ndombe

I.

I’ve never been afraid to hold a worm. If I hadn’t caught the sight of it, I would’ve sliced the poor thing in half with my bike on the corner of Varsity & Crest.

Something like a savior complex seeps in as I toss my bike to the curb and cup the bulbous brown thing in my hands.

The many ridges along the worm feel wonderful as they glide over the cracked canyons of my palms. It grows restless and sticks its head up to the sky between my hands, stretching to peek over my thumbs. Such a rebellious little thing, I say. You could’ve hurt yourself.

II.

I’ve never been afraid to hold a bleeding boy. If I had gone any faster, I would’ve crushed the poor kid with my car on the corner of Varsity & Crest.

My savior complex jumps in again as I toss myself out of my new Civic and cup the battered, Black boy in my hands.

The many fractures to his skull feel tender as they glide over the cracked canyons of my palms. He grows still but tilts his head up to the sky above my face. He must ache to stand and run away. Such a rebellious little thing, I say. You could’ve killed yourself.

36

III.

The boy will live, but nothing more, I’m told in my padded cell. They tell me I’m here because I ran over the boy on purpose— because the cars nowadays are elite, and you can always slam on the breaks if they go too fast.

When I’m told the boy has started to gulp down semi-solids, I decide to starve on and off for a while. I revisit the day I crushed him to punish my superego until I hear he’s somewhat amble in a motor chair.

The nurses tell me that if I had waited to eat any longer, I wouldn’t have been able to stomach anything else.

I watch them stick me with some IVs, prepare dinner. Such a rebellious little thing, they tell me. You could have killed yourself.

I chuckle, let them save me just this once.

Poem Statement you could have killed yourself speaks on Black generational trauma, violence, self-harm, self-deprivation, and the cyclical struggle of having a savior complex.

37

—Patricia Ndombe is a second year graduate student in the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing program (with a focus in Poetry) at North Carolina State University from Knightdale, NC.—

I

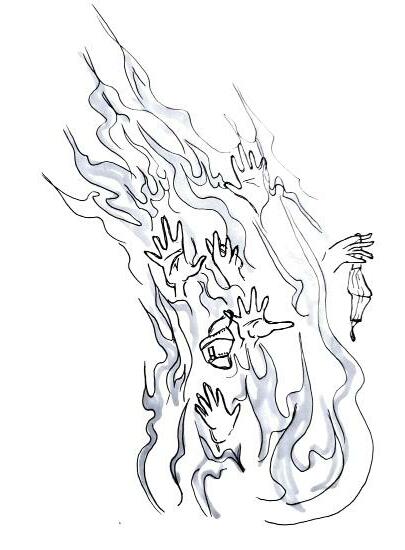

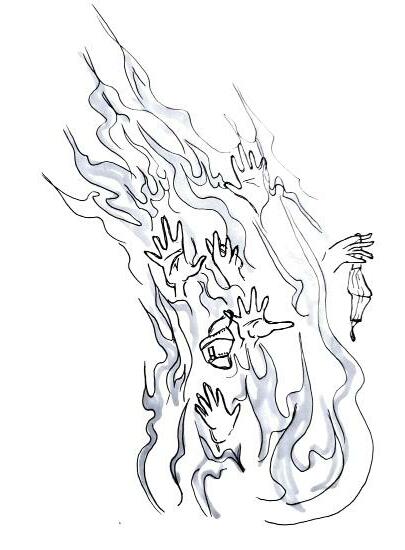

Shades of a Mind Aaron Hahn

The island left her. Still lingered, on her indented pillow, endless waves of a resting sea. I am working with the patient in this ward between her thoughts and death — the attempts and pauses. Her mind meanders like a swarm of ghosts gyred around time — the irreversible universe, where she is a burning star.

II

In singing, she saw the blue. You are here even when I’m not here. You love me even when you know I can’t. You are here. Who else can you be?

III

The sounds of turned paths and burning leaves fade away behind the walk Untangling her long and curly hair. Less is more to arrive — She knows. IV

“Remember that day?” The voice came to her. She became deaf to songs. But I have no permission to enter her stream of feelings on a stormy day.

V

What appeared in the mirror Was a body of silvery water With rose petals unfurled like sails When she remembered the touch. VI

Who’s there? Something elbowed her on her last birthday and she looked back. VII Night let out a strangled gasp, Spattering the inmate With snapshots of judgments. VIII

How could she say every end is a gift? They kiss her and whisper, “You are free.” “You are free to run out of this box and open — Open another one.” O-ver. Everything went to zero. No problem at hand; Just walk away — they all preach.

IX

The wind whispers — let go of your clothes and close your eyes. Unveil the clouds to face a naked mind. Even skin is too heavy. Let go of clutter. Mind alone aloud like a cactus on Venus.

X

Fate awaits while the devil allures. She sleeps in between them and dreams — of flying away. Crawling out in hazy clouds, she gropes for the light switch. Cleaning the mess, she spends hours or days and stops right before her toes Though the real clutter begins there. She spends hours or days, cleaning her glasses, not her eyes, not her mind — She cries; She yells; She begs; And she waits in the dark, cutting her hair.

38

39

—Aaron Hahn is a graduate student studying Education at UNC-Chapel Hill from Seoul, South Korea.—

Just Like Mom

A.H. Stepp

What does a love of sushi and vacations to secluded beaches have in common? Nothing—unless you were to talk about similarities between me and my mother. Growing up, it was an endless stream of comments from women who “knew me when I was *signals height with hand gestures* this tall” and family members who could not believe the resemblance in our upbeat body movements, our bright smiles, or even our noses which my grandfather fervently claims are from our Sephardic roots. I loved it this way too.

I was her firstborn son—a label I carried with pride as it solidified the special relationship I had with my mom, my strongest cheerleader, toughest critic, and best friend. I was just like mom. However, in the back of my mind, I began to believe that I was not just like mom.

Did she focus on the meticulous pattern of each tile in her school hallways when she was five, avoiding every tile that did not match the exact shade of blue or or ange she preferred? Did she ever get nervous about a lack of symmetry in certain rooms by the time she was seven? Did she notice an off-centered doorway that would then offset the rest of her day? Did she ever deal with intrusive thoughts by the time she was nine? Did she sit and tap her fingers against her wood veneer desk in her blue, softly lit room at 8:03 pm as she waited for her parents to get home, hoping they didn’t crash their car or have a medical emergency or eat something poisonous or any other idea that her irrational mind could conjure up like a fairytale potion?

Because I did.

Before long, nine turned into thirteen and thirteen into fifteen when I heard the words leave my therapist’s mouth: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. It was humiliating knowing that I could not sleep comfortably because I did not properly close my bedroom door to make its satisfying ‘click’ sound. Or that I could not leave the oven until it was turned off seven separate times, searing the neon-glowing of the 375° and the repetitive beeping noise into my brain like a branding stamp unto neuron-fibered leather.

40

However, even in this mental chaos I called my own, I had my mom with me—my strongest cheerleader, toughest critic, and best friend. She was always a beacon of strength in my life, providing clarity and hope in my battles while simultaneously serving as my role model. Even in difficult moments, she never seemed to falter. Yet, I still believed this irrationality was unique to me. That it was a personali ty flaw only I would know. By the time I was sixteen, life felt like a dark void; a room painted with the darkest, purest shade of black known to mankind with one tenant: me.

Sixteen quickly turned into seventeen and before I knew it, I was pack ing my things for a new stage of my life: college. In the process, I found myself rummaging through my house, trying to find as many useful knick-knacks I could stuff in my bag and take to my new home an hour, twelve minutes and for ty-three seconds away. As I began organizing items into “keep” or “stay” piles, I came across a small mahogany bookshelf in my parents’ bedroom filled with old music books and family heirlooms. While rummaging through these books, a list of poems and notes fell out from the back of the shelf and onto the carpet below, just within arms’ reach to continue my nosy journey. My heart began to beat slower after picking up a poem off the floor. I felt my heart sink to the bottom of my chest, like an anvil in quicksand. My hands began to shake as I read lines of my mother’s poems dated to June of 2004. The initial drop in heart rate quickly turned into a rapid heartbeat that raced quicker and quicker as I examined each line.

I feel lost. I am in a desert. Alone. With each stanza, I felt my mother’s despair pulsate through me. I pro cessed each meticulous description of her life and felt her trauma as she ex plained life without her mother who died of cancer when she was five and losing my older brother in childbirth. With each letter, I could feel my heart and mind explode in synchrony as she described her experiences with washing her hands until they began cracking and bruising and bleeding. Speeding back home from her job to make sure the curling iron was unplugged for the seventh time. Sitting, tapping her fingers at 11:00 pm on our black kitchen countertops in our

41

dark kitchen waiting for me or my siblings to get home just to make sure we didn’t crash our car or have a medical emergency or eat something poisonous or any other idea that her irrational mind could conjure up like a fairytale po tion.

As I sat on the floor of my parent’s bedroom, crying, processing the piece of my mother’s life that I just discovered, I found something new. I found that in my dark room, with the deepest, purest shade of black known to mankind, I was holding a hand. Maybe, I am not alone. Maybe, she understands what I have been through more than anyone else.

I guess I really am just like mom.

—A.H. Stepp is a freshman majoring in English (concentration in Science, Medicine, & Literature) with minors in Spanish and Chemistry at UNC-Chapel Hill from High Point, NC.—

42