MISSION STATEMENT

The Health Humanities Journal of UNC-CH aims to inspire and facilitate interdisciplinary thinking and collaborative work while developing and embodying a variety of ideas that explore the interface between arts and healing. This publication allows for dialogue, meaning-making, and multiple representations of the human body, medicine, and illness.

To learn more about the publication or to submit, visit the following website: https://hhj.web.unc.edu.

DISCLAIMER

The Health Humanities Journal of UNC-CH adheres to legal and ethical guidelines set forth by the academic and health communities. All submitters maintain patient privacy and confidentially according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and The Health Humanities Journal of UNC-CH do not endorse or sponsor any of the viewpoints presented in this journal. The opinions presented in this journal are those of the corresponding authors. This publication is funded at least in part by Student Fees which were appropriated and disbursed by the Undergraduate Student Government at UNC-Chapel Hill.

SPONSORS

Spring 2024

The Health Humanities Journal

of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

exploring illness, caregiving, & medicine

Editor-in-Chief

Managing Editor

Art Director

Secretary Treasurer

Layout Editor

Marketing Co-Director

Undergraduate Editors

Editorial Team

Ryan Phillips (Class of 2024)

Tara Hinton (Class of 2025)

Anna Curtis (Class of 2026)

Roshni Arun (Class of 2026)

Iris Chang (Class of 2025)

Yan Zhu (Class of 2026)

Alicia Equan (Class of 2026)

Sabrina Shaw (Class of 2026)

Penelope Alberdi (Class of 2024)

Camilla Feeley (Class of 2024)

Rotem Olsha (Class of 2025)

Ash Chen (Class of 2025)

Aliyaa Pathan (Class of 2025)

Isabel Kakacek (Class of 2025)

Boatemaa Agyeman-Mensah (Class of 2025)

Gugma Vidal (Class of 2025)

Heidi Segars (Class of 2025)

Aaron Stepp (Class of 2026)

Izabella Counts (Class of 2026)

Naomi Lytle (Class of 2026)

Graduate Editors

Faculty Advisers

Olivia Davis (UNC School of Medicine: Class of 2025)

Jacqui Zanders (UNC School of Medicine: Class of 2025)

Jane F. Thrailkill, Ph.D. (Co-Director, HHIVE Lab | Department of English and Comparative Literature)

Kym Weed, Ph.D. (Co-Director, HHIVE Lab | Department of English and Comparative Literature)

Faculty Adviser’s Note

For It is a Tradition

Cutting into Jane Doe

Fractured Healing

Henry Ford Hospital, 1932

for the Black girls who sometimes con-

Ryan Phillips

Jane F. Thrailkill

Anmol Surpur

Christian Goodwin

Anonymous

Kate Stukenborg

Ashlynn Hoshiko Cooper

Jade Brower

As if it

Eight-Armed Rose

The Cradle

Postpartum Insomnia

Everything at Once

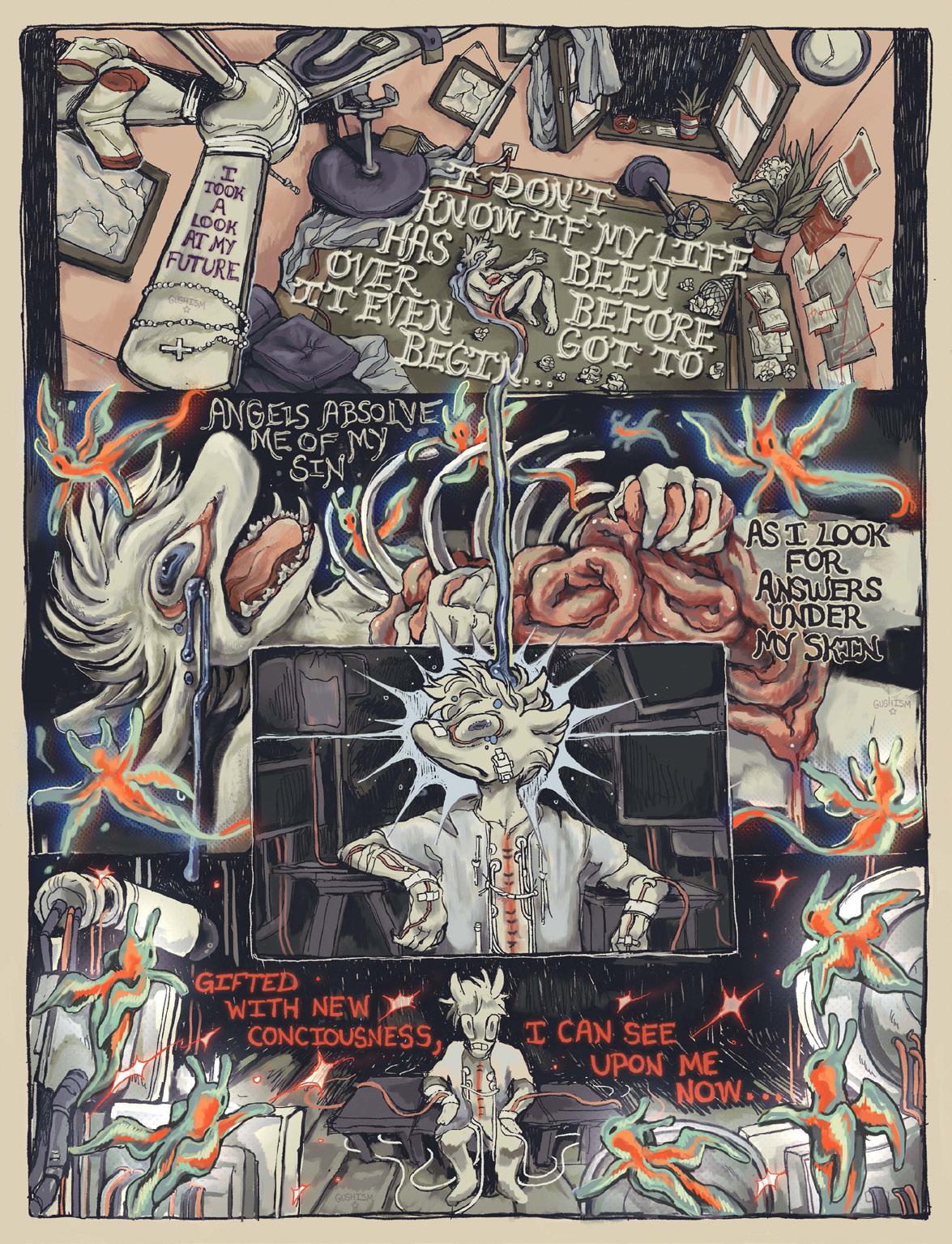

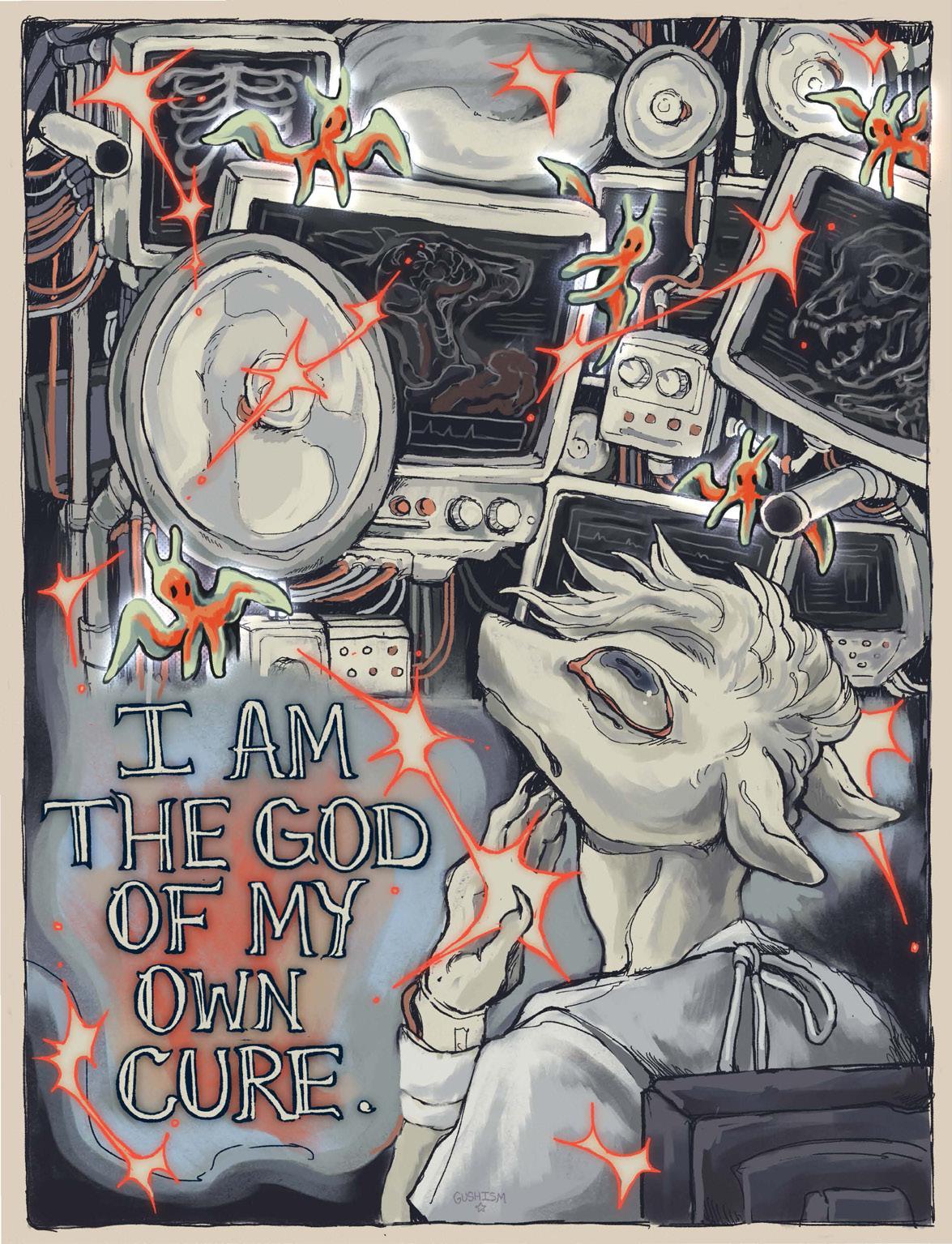

I Took a Look at My Future...

Saying Goodbye to Legends

I am no Soldier

Seeing “The Other” in the Psych Ward

Worry Worm

An Illness Narrative

Seven-Year Gap

Macy Crosser

Lasya Priya Kandukuri

Lasya Priya Kandukuri

Lasya Priya Kandukuri

Altonji

Kathryn Watkins

Anonymous

Mae Brockman

Celia Gibbs

Art

Table of Contents 6 8 10 12 14 16 19

by Anna Curtis

Editor’s Note

Soha Raja Anonymous Mya Webb Naomi Grace Christina 20 22 24 25 26 27 28 30 32 35 38 39 42 sider what they wish it was like

Living With Wasps

Day

were a Normal

Editor’s Note

Dear Reader,

Take a moment today to consider everything you share with your loved ones. The traits and gifts given and taken that float between friends, within families, and across generations. They may be quite specific: a love for your favorite team, a method of cleaning the dishes, an heirloom that’s always kept safe. They may also be more holistic: an intrinsic perspective on health, a way of showing love to a sibling, a vision of what it means to care for yourself.

This edition of The Health Humanities Journal of UNC-CH examines, celebrates, and pays tribute to all the traits and entities we inherit and the cycles that result. The pieces that follow acknowledge the ways that our distinguishing characteristics are often an amalgamation of the traits we’ve received from our forebears. The works span a wide range of topics, from self-reflection about the way a loved one’s health condition affects the bond we have with them to the scrutinization of the societal forces that draw us into the cycles we’ve experienced for generations. I want to emphasize here that the cycles and lineages we showcase in this edition are not merely familial. While many of the foundational relationships in our lives lie within our own families, our authors have chosen to explore avenues beyond these. Their pieces investigate the internal cycles that govern one’s own life, as well as the beliefs and memories we gain from our own lived experiences, often resulting in inheritance from those outside of our typical circles. The gradual shaping of self that defines our journeys can be whittled down to the gathering and sorting of all the different inheritances we reckon with across our lives, whether from loved ones or strangers, whether innate or developed over time.

Reading through the selections of this edition, I began to contemplate the roles I play in my own life in terms of perpetuating and breaking cycles, retaining and passing on the ideas I have inherited. There are numerous areas of my life where these thought processes are relevant, but the one I would like to highlight here is my role in this publication. Throughout the submission review process, I found myself considering not only the ontological roots of each piece’s ideas and approaches but also the internal foundations of myself that may lead to my liking or disliking of a piece. This brought me back to the notion of inheritance: What are the parts of me that resonate with this piece and where did they come from? What roots are the author drawing from that brought these experiences and perspectives to their life? Questions like these reverberated in my mind through the entire creative process, leading ultimately to the collection that lies before you.

6

Also on my mind as I write this note is the reality that this will be my final semester serving as Editor-in-Chief of the Health Humanities Journal. As bittersweet as it may be to say goodbye to this staff and this publication, I can hardly imagine a more fitting thematic focus for the end of my time here. The knowledge and understanding that I have inherited from those around me, whether the staff or the authors, have made me a better leader, writer, and person. As my time comes to a close, I think of the transition less as a process of inheritance, but as a snapshot of the ongoing cycles that encompass our communities. At the same time, this journal’s gradual development is, in many ways, a process of inheritance in and of itself. As I leave the organization, I also leave the ideas and practices that I encouraged while I was here, as did those who came before me, and as will those who follow.

I want to take the time to thank those who have made this edition of the journal possible through their guidance, knowledge, and support: our advisers, Dr. Jane Thrailkill and Dr. Kym Weed; our generous benefactors Honors Carolina, The Undergraduate Student Government, and Dr. Vincent Kopp; our authors, who have graced us with their words and images; and our staff, who form the backbone of our publication with their tireless devotion. In particular, I want to thank Tara Hinton and Iris Chang, who will take the lead in the next stage in the cycle of our journal’s development. I want to extend my congratulations to my fellow graduating editors, Penelope Alberdi and Camilla Feeley. Lastly, I want to thank you, Reader, the reason we are able to publish at all. It is my sincere hope that the writing and art ahead of you allow you to contextualize your role in the cycles around you, consider all you have inherited and will someday pass on, and perhaps resonate with the perspectives you witness within these pages.

-Ryan Phillips, Editor-in-Chief

7

Faculty Adviser’s Note:

The Wittenberg Project

At the end of March, I traveled to Wittenberg University, a small liberal arts college in Springfield, Ohio, to offer advice and share ideas as they design an interdisciplinary health humanities program. They had heard about HHIVE Lab; about UNC’s undergraduate minor in Literature, Medicine, and Culture; and about the Department of English and Comparative Literature’s MA program in health humanities. They reached out to me; I accepted the invitation, curious about what wisdom a large public university could offer to a small private college.

During my stay in Springfield, I talked about my experience working with colleagues to build a health humanities community and curriculum here at UNC. The Health Humanities Journal – the first of its kind, founded in 2016 by UNC student Manisha Mishra—was a particular point of pride. I explained that the HHJ speaks to a core value of our program: that students—undergrad, graduate, and professional—are not just learners but at the creative core of everything we do. I emphasized that collaborative inquiry, infused with a deep commitment to the humanities, is at the heart of our research studies, our community programs, and our innovative classes.

Faculty at Wittenberg also shared their story with me, and I pass it along to you. A cautionary tale about the challenges we face today in higher education, it is also a hopeful model for how an appreciation for both poetry and practice can cohere. It also shows how much a big university with a wavering commitment to a liberal arts education can learn from a small college.

Wittenberg University was founded in Springfield, Ohio, in 1845, and its liberal arts mission has sustained it for close to two centuries. With roughly 1,200 undergrads, the college embraces “the life of the mind” and the “wholeness of the person” – centering its curriculum on “the liberal arts as an education that develops the individual’s capacity to think, read, and communicate with precision, understanding, and imagination.”

Like many excellent small colleges across the United States, however, Wittenberg is under duress from growing expenses and declining enrollments. The anti-intellectualism of some lawmakers adds salt to these financial wounds. (In fact, during my time in Ohio, Birmingham Southern College closed its doors when the Alabama state legislature failed to pass legislation to help pay its bills.)

Wittenberg sits atop a hill in what was once a manufacturing center but in recent decades has seen businesses shuttered and jobs move overseas. The town of

8

~

Springfield, Ohio – like so many small cities across the U.S.—itself has economic woes.

Nonetheless, two “industries” continue to distinguish the town of Springfield: higher education and healthcare. Faculty at Wittenberg have taken stock of these remarkable resources. They see the interdisciplinary field of health humanities as way to weave together the scholarly and the practical: the life of the mind and the health of the body; the academics on the hill and the healthcare professionals in the clinics. Faculty in fields ranging from English and religious studies to nursing and neuroscience are connecting with clinicians and health administrators to create a robust program that includes new courses, research collaborations, and community partnerships.

Just last month the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded a competitive grant to support their ambitious project, which they’ve entitled “The Healing Humanities: Creating Healthy Pathways on Campus and in the Community.” The final goal of the project? “To make Wittenberg the first liberal arts school in Ohio to offer a certificate program in health humanities and equity.”

For my part, I am inspired by the ambition of the Wittenberg project, with its clarity about the power of the humanities and the beauty of clinical practice. Health humanities students see their study of the arts as integral to their career aspirations. In this issue of the HHJ, we see how poets, essayists, researchers, and artists weave these distinct threads into meaningful form. In the words of one of one contributor—who is also a nighttime caregiver to infirm elderly—poetry and practice intertwine: “In both my overnight and written work, I stretch and mold my muscle of empathy, the cornerstone of care.”

-Jane F. Thrailkill, Faculty Adviser

9

~

For It is a Tradition

Anmol Surpur

Week after week, bottle after bottle, my mother’s well-trained hands sat me down and parted my hair as she slowly poured the warm coconut oil down my scalp, my face grimaced as it seared to the touch. The warmth spread through my head, peace rolled over my mind and body as her hands tugged my unruly, unrelenting curls into sleek, shiny, dark braids that trailed down my back. My sister went next, and my mother last.

The royal blue bottle stands bright in its place on the dresser shelf, its worth and utility glistening in the light, for generations and generations. We stand in the mirror side by side, smiling, as we all look one and the same.

For it is a tradition.

Until the first strand of hair drifts onto the floor. And many more follow.

Week after week, My mother’s well-trained hands tighten around mine as the chemotherapy flows through her, her face grimacing with the pain, the chill of cancer ruminating among us. The sweet, buttery aroma that once filled my nose is masked by the cold, calculating scent of alcohol permeating the hospital room, the only warmth emanating from a cup of coffee that lays untouched in front of me,

As my sister’s tears glisten rolling down her face.

For it is a tradition.

At home, the coconut oil now cowers in darkness, dusty, untouched, frozen solid in the barren cold.

For it is a tradition.

10

We still stand in the mirror side by side, no longer looking one and the same,

But we smile nonetheless for the traditions that we will make our own.

—Anmol Surpur is a research technician at Columbia University Irving Medical Center from Union City, NJ.—

11

Cutting into Jane Doe

Christian Goodwin

I push through the heavy wooden door into the basement operating suite. The room is frigid. Important for the procedure, I’m told. The early winter sunset filters through the frosted single-pane windows. I watch the light dance to the unrelenting hum of the ventilation system. I get there early; I want time with the patient before our work begins. I scrub in. The unmistakable scent of Dial Gold permeates the air as I anxiously lather, watching the water hit the basin of the stainless-steel sink. Greasy streaks from the last procedure adorn the sides. I’ll add mine soon.

I find Jane lying silently on her steel operating table with our scalpels and forceps neatly arranged beside her. Her eyes are covered. I lean over and take her hand in mine. She has immaculate rose-colored glossy nails. Each nail reflects the whole room like a funhouse mirror, shining on the backdrop of her pale hands. Jane must have had them painted earlier this week. Was there a special occasion, or did she always keep her hands this neat?

I asked my instructor earlier that day what we knew about her. What is her past medical history? “We’re not allowed to know that sort of thing,” I was told. “It’s not really appropriate.” Does she have children, I wonder? Do they get together at the holidays? Does she drink dark coffee in the winter? Or eat fresh peaches in the summer? Does she wear pink sweaters to match her nails? Those are inappropriate questions too, I guess.

I gingerly hold Jane’s sun-spotted, bony fingers and thank her for being here. For a moment, I’m back at my grandmother’s bedside holding the same fingers. I should call my grandmother...

Suddenly, the heavy doors bang open and my fellow learners flood in. The quiet evaporates, replaced with the comfortable sounds of small talk. My team gradually drifts over to our table. As we inspect our tools and unfurl our rubber gloves, we share holiday plans and catch up on the weekend.

I pat Jane’s hand once more. It’s time for the ritual to begin.

A dozen Stryker saws whir to life in unison. I hold Jane’s shoulders in place and read from our flesh-caked instruction manual as a classmate

12

guides our saw. “Transect the sternum immediately below the level of the jugular notch,” I read aloud. “Cut through the ribs and soft tissue of the lateral walls along the midaxillary line until you have cut through all the ribs.” I count in my head as we snap each rib. One. Two. Three. Four. Five—I lose count as the saw flings more viscera onto the instruction manual. With the ribs rendered obsolete, we peel Jane’s chest back onto her stomach, revealing the treasure below.

I’m up next, tasked with hacking away at Jane’s side to clear away the fat. A passing instructor leans over my shoulder. “Don’t worry about being gentle here. There’s nothing important until you get past the ribs.” He takes out his own scalpel and demonstrates proper flaying technique, piling up the nuggets of fat and tissue in the formaldehyde pool below as he burrows through Jane’s body. “We don’t really need these pieces; you can toss them if you want,” he says with a wink.

Another instructor’s eyes light up as he passes by. “Do y’all know what this muscle is,” he asks, pointing towards a clump of muscle dangling from our patient’s side. My classmates and I exchange silent, wary glances. All I see is the pulled pork I cooked last week. “It’s the serratus anterior; that’s what gives boxers the power behind their punch,” pantomiming a right jab. Everyone at the table offers a forced chuckle, dutifully nodding our heads.

We reach the end of our session and begin folding Jane back together like a slimy and pungent origami crane. “Does anyone know where this piece goes?” Our classmate holds up a piece of flesh for everyone to examine. We all shrug our shoulders as she sheepishly tucks it into the gaping hole we just dug. We all laugh. We have to. If we don’t, we might think about the person we just butchered.

Now Jane is gone. She’s been zipped into her airtight sleeping bag and wheeled back to her refrigerator to rest until the next dissection. The dissectors are back at the sink where we started, washing our hands of the work. Glancing down, I catch a reflection in my classmate’s painted nails, freshly cleaned and shimmering under the running water. I should call my grandmother.

Christian Goodwin is a fourth year student in UNC-Chapel Hill’s School of Medicine from Richmond, VA.

13

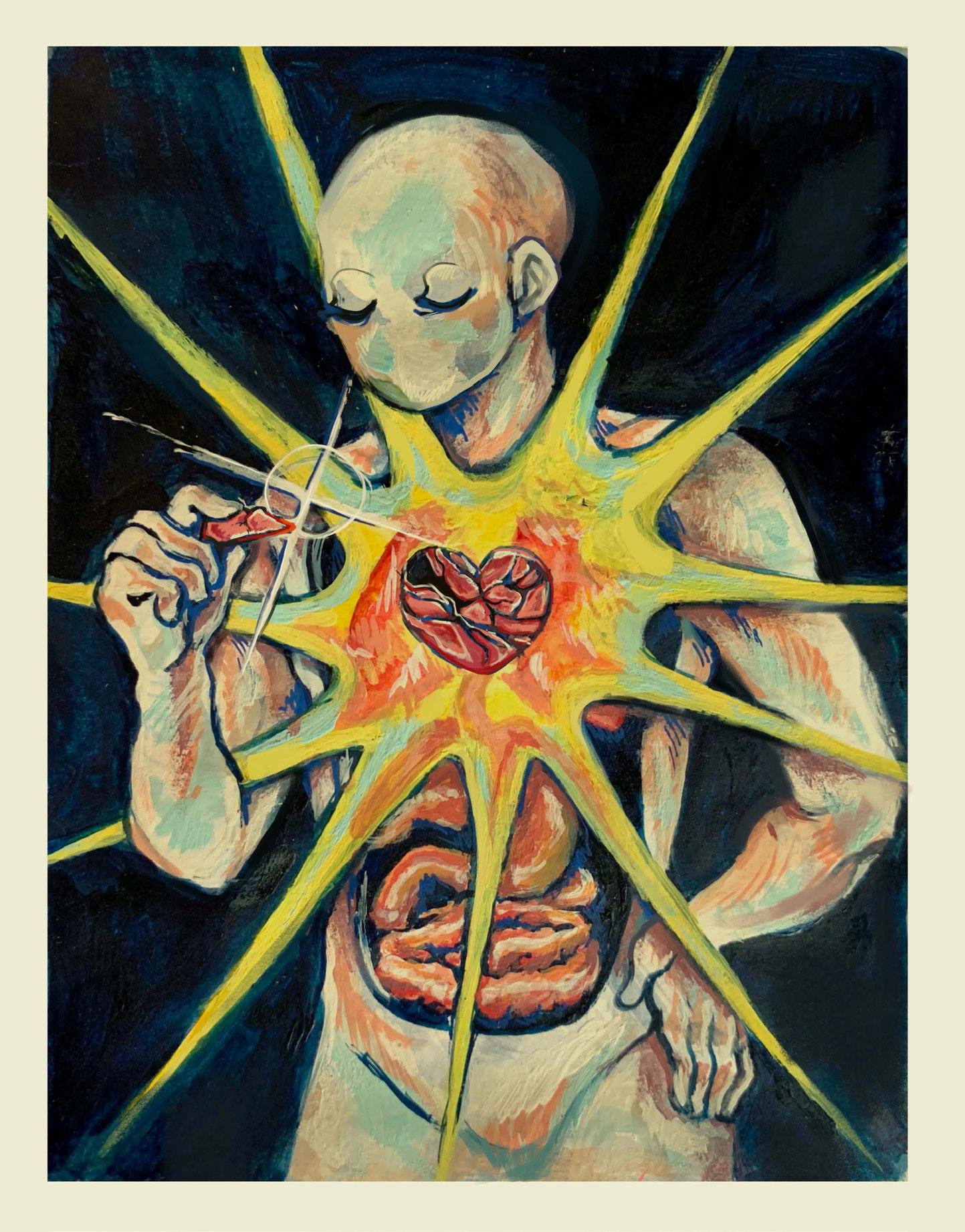

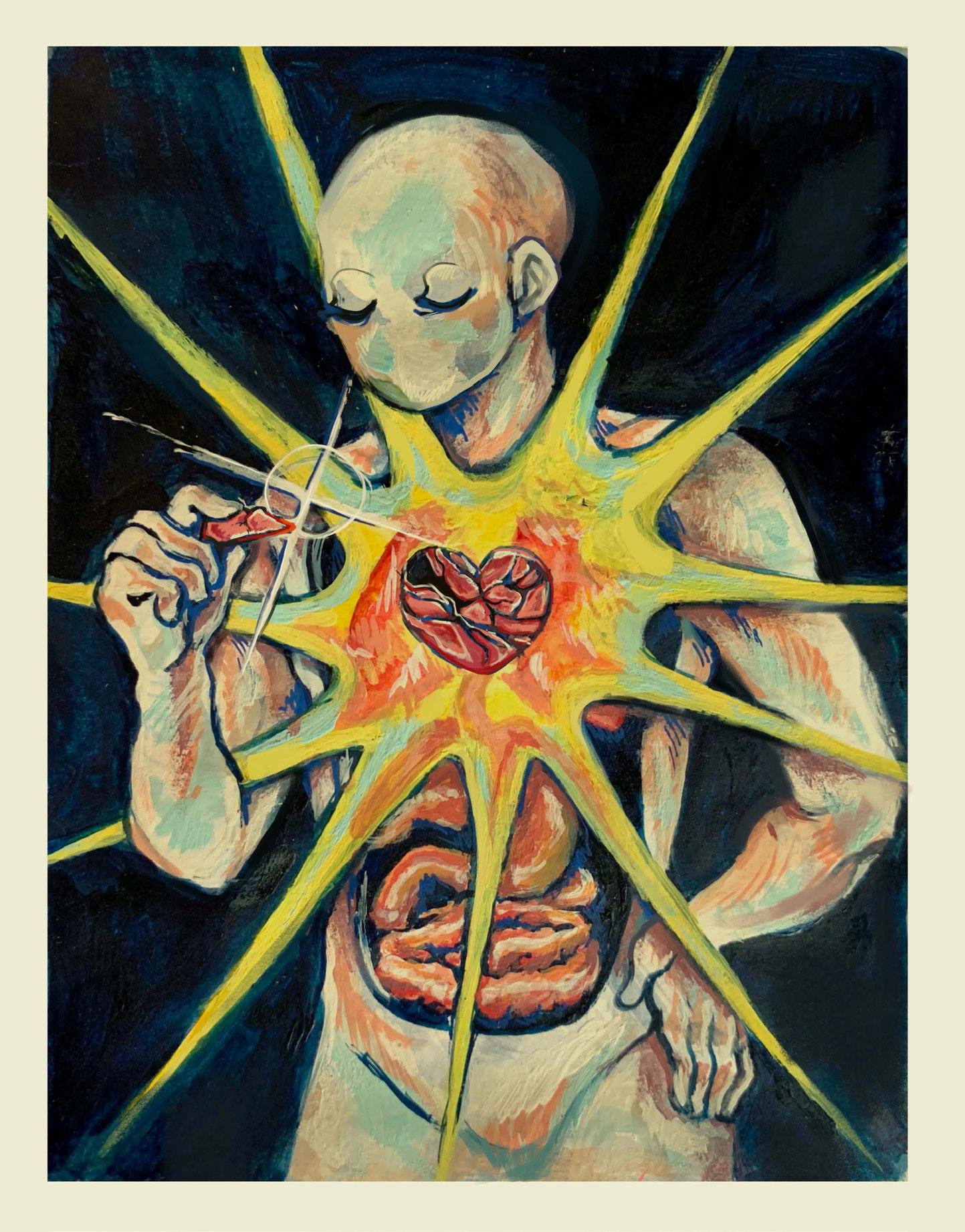

Fractured Healing Anonymous

14

For many individuals, recovery from physical or mental trauma is a lifelong challenge that often doesn’t progress linearly, like needing to pick up the fragments of what you once were and what you could be and find ways to piece them back together. I painted this piece with gouache a few years back to reflect on and portray the clarity that comes from putting yourself back together despite the odds.

My mother was in an accident in 2020 that has left her with lasting challenges that have deeply impacted her daily life. It still causes ripples of pain and sadness. In the height of a pandemic as a healthcare worker, my mom had already endured the emotional turmoil that comes with the uncertainty of holding other people’s well-being in your hands, though she has made incredible strides to provide strength to struggling families through her positions of leadership and community.

When the initial accident occurred, it was so difficult to look forward to the future without thoughts of pain and trauma. Her recovery was slow, and it certainly took a lot of strength and grit for her to get back on her feet My mom and her feats of bravery in health and experiences in the field of nursing and surgical practice have inspired me since I was young, and I look forward to exploring and sharing more of those one-of-a-kind stories.

15

Henry Ford Hospital, 1932

Kate Stukenborg

The first time I saw Frida Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital, I was surprised by my response: sadness like a muscle, strained by the weight of her portrait. The painting was done on a metal frame, cold and uncomfortable like Kahlo’s hospital bed. I have not touched the painting, of course, or even seen it in person. I can only imagine the discomfort, and I can only imagine so much.

In Kahlo’s depiction of her miscarriage, she’s a puppet of her own lost items, unable to reach the masters strung to her open stomach. There’s an orchid with its purple uterine folds drooping from a cut stem. Then, a snail curving its shelled body away from Frida’s face, dragging the slack slowly from a red umbilical ribbon. Above her, a piece of the broken body hangs in mid-air. If only her organs could be like the steel machine below them, strung to the stomach she is holding. If only the parts were interchangeable and made to fit each other, able to be repaired apart from each other. Her soft body must have envied it. The flat bone of the pelvis is below her, tissue and cells slightly but devastatingly misshaped. At the top is the lost child, still corded to mother Kahlo. The arms are raised and legs crossed as if they were trying to be small, trying to be comfortable inside her.

I can hardly imagine the hurt of it – hurt in the stomach, pulsing hurt. Maybe she felt it in the bottoms of her feet, where blood webs its way down the thin bedding. The first time I saw Henry Ford Hospital, I cried because I recognized—for the first time—the hurt of women who go through this. Before, I considered the loss more as a dashed hope than as a grief. I cried because I was wrong. I wondered what might be tied in red ribbon and thread to my Mama’s hurt, once-hollow stomach. I was afraid to ask her. I was afraid to know how much I had underestimated her suffering. I think: maybe I should apologize. For never having asked, for never having known. I wonder all of this as I look at Kahlo’s painting. I cry because I’m alive. I think: I should cry all the time because I’m alive, and always apologize. I should be safe for Mama, and always do my best to stay alive.

I know my Mama loves me with the grief of a lost one. I don’t feel guilty, mostly. She gives me what love she has, and it comes from many places, at

16

least half of which must be dark and sharp and difficult. I don’t think she has seen this painting. I want her to see it, but I don’t want to show her. I hope she comes across it herself and feels the bitter satisfaction of being understood.

I don’t think about the painting often, but the memory of it comes back to me one summer while I’m cooking lunch with my friend Melanie. Her presence is gentle and uncritical. She has the kind of warmth that makes people feel like they’ve known her for a long time or wonder if they’ve known her in another life.

She and I are cooking lunch for ten—asparagus and shrimp risotto, beet salad, pineapple pieces to eat after the meal. We chat while we peel, chop, and stir. Shared work like cooking can give the most meaningful conversations an air of casualness. Our eyes are trained on our busy knives and not on each other. We feel unobserved, and we’re much freer with our words. At the time, I’ve only known Melanie for a few days, but it’s easy to be honest while we peel onions and split half-frozen white asparagus. We don’t make eye contact. We’re both listening.

We talk about the things of women: marriage and menstrual cups and all the things that can go wrong with our female bodies. Melanie tells me about endometriosis; she talks about doctors who didn’t believe and didn’t help, stealing hope from her slowly. She talks into her cutting board about the mystery and the pain and the frustration. Then she tells me about her miscarriage, how devastating it was.

I’ve only known Melanie while she’s been pregnant, and she seems to carry it easily. She’s been standing for a while now without a break, and I hardly would’ve noticed the pregnant belly if it were not for the ultrasound on a table in her living room. I point it out later, not asking anything specific. She tells me about the ultrasound appointment, how nervous she was. I imagine a red ribbon—like the ones in Kahlo’s portrait – strung through the corner of the printed ultrasound and her stomach. This time, the ribbon is a symbol of the hope that grows out of grief; before we can say, “maybe it could be this way,” we say “it is not supposed to be this way.”

Mothers should not have to bear the grief of their own children. Mothers hope their children will have another day.

17

After an hour or so of talking, Melanie and I have spoken our mouths dry, so we fix water for the table and ourselves. We keep stirring the risotto so it doesn’t stick to the pot bottom. We toss pieces of beets in dressing, and we slice thick prisms of pineapple. Lunch guests start coming in and finding places at the long table. I take the big pot of risotto before Melanie can. I know Melanie will try to carry the pot if I don’t, despite being told not to lift anything heavy. She busies herself bringing pitchers of water to the table.

Over lunch, the group starts to talk about art, and what it means for art to be beautiful or ugly. I don’t know the exact question that gets the whole discussion started, but I remember that it feels choppy and a bit uncomfortable. We all have different definitions of beauty, and we can’t seem to get on the same page. Hoping to make the conversation easier, a few of us decide to share pieces of art that are meaningful to us.

I explain the first time I saw Kahlo’s sorrowful, beautiful portrait. Without wanting to take up too much time or offer up too many gory details, I explain the painting. I briefly describe the hospital bed, the displaced pieces of self, the pain she conveys. I don’t expect anyone to have seen it. Plenty of people have come across The Two Fridas or The Broken Column: a famous depiction of Kahlo’s spinal surgery. Henry Ford Hospital is relatively wellknown, too, but certainly not the first painting of Kahlo’s that someone would come across.

When I mention it, I notice a shift in Melanie’s face from across the table. She raises her eyes from her plate, and I hear her whisper “I love that painting” to no one in particular. When I finish talking, I smile in her direction. I know we are both thinking of the same red-ribboned grief, and I’m smiling because I have discovered another woman who knows the kind of love it allows.

Kate Stukenborg is a senior majoring in English and Interdisciplinary Studies in Education at UNC-Chapel Hill from Memphis, TN.

18

for the Black girls who sometimes consider what they wish it was like

Ashlynn Hoshiko Cooper

color me white with a silk chiffon bow: ask about my day, how the family’s doing; encourage me to join that club and take up that sport that you were once a part of and when I bid you goodbye color me white.

color me blue: hand me a pamphlet, give me a stern talking to about grease and play and gravity; tell me all the things you know I don’t do, prescribe me a pill or two and when I come back color me black.

19

Ashlynn Hoshiko Cooper is a junior majoring in Psychology and minoring in Health and Society at UNC-Chapel Hill from Gurnee, Il.

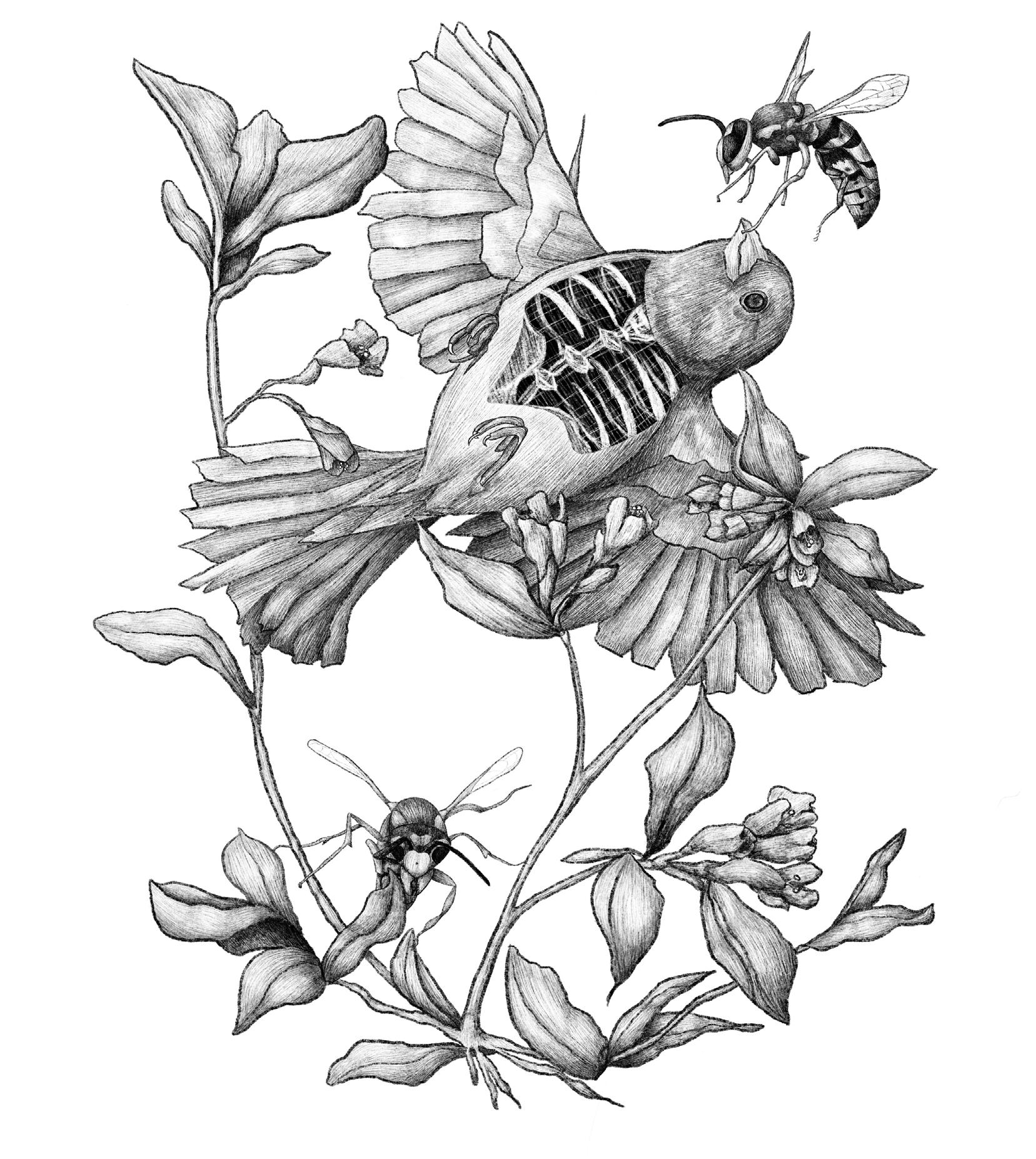

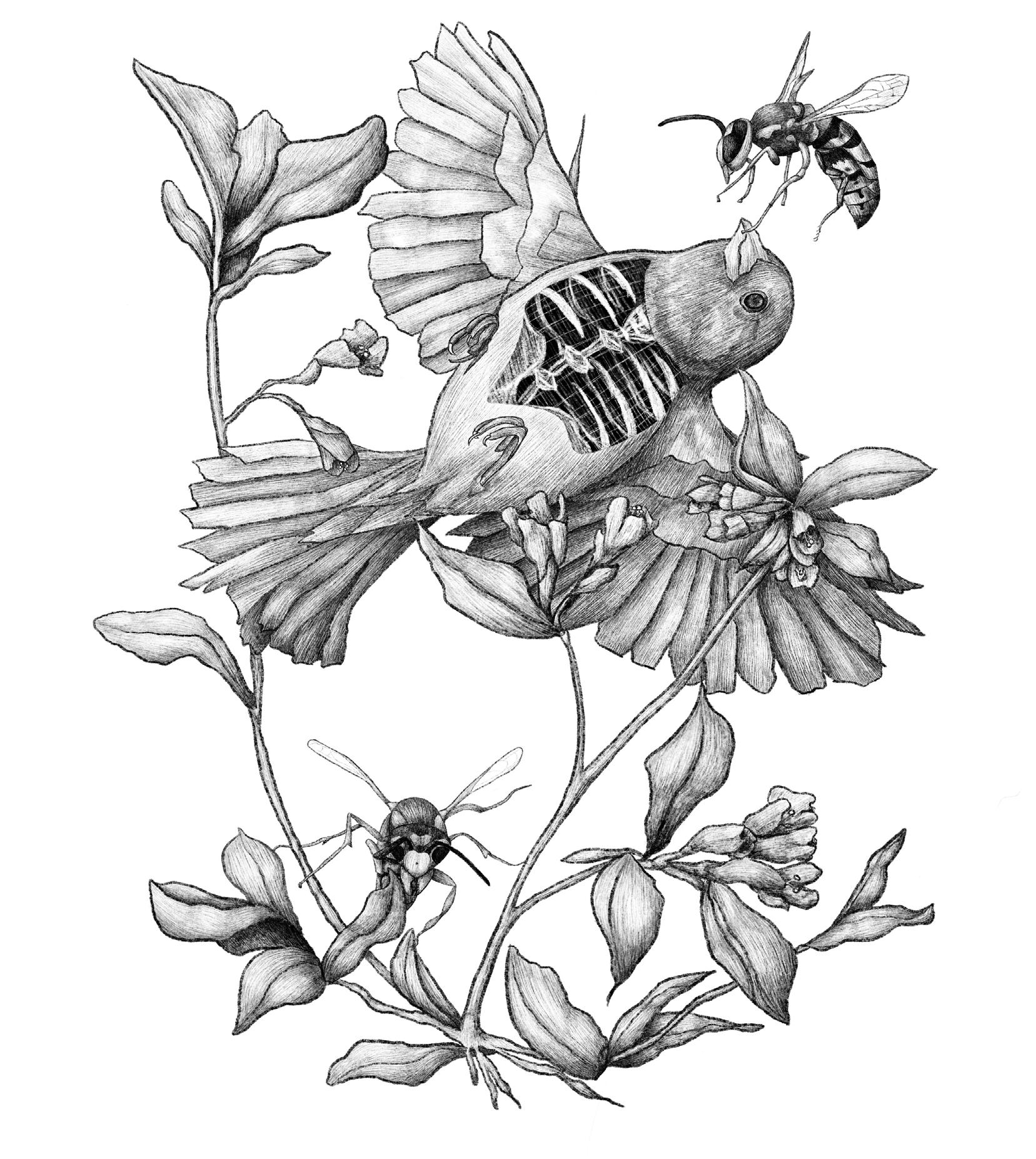

Living With Wasps

Jade Brower

20

The presented work is a reflection of depression after recovery, and how it functions as a third party in opposition to any reasonable self-interest. A sparrow, uplifting and lively by nature, serves as an embodiment of its viewer with human-like bones. While falling past the environment of flowering weigela, the wasps serve as their only company. The wasp’s guiding hand upon her beak ensures and demands commitment, despite its unassuming size.

Depression does not define an individual, nor their environment, yet it is powerful enough to deceive people that it does. Wasps– having a generally alarming and unwanted presence– are a reminder of this. If reflecting externally, the face-to-face confrontation is still visible beyond the sparrow, as another wasp simply stares resting low in the leaves. This piece aims to build confidence in the internal acceptance of living with wasps.

21

Jade Brower is a freshman majoring in Art Management at Appalachian State University from Cary, NC.

As if it were a Normal Day

Macy Crosser

I pull my long hair back into a ponytail as I walk into the waiting room on the second floor. Children’s cartoons blare gibberish through the small room as I settle awkwardly into the scratchy chair. The colors on the wall scream at me. A child no older than three walks past me as I wait for my turn. I bet my dad can hear how hard my heart is beating from the chair next to me. She calls my name and I slowly stand up.

Silence envelops me as I walk into the all-too-familiar insulated cube. I sit in the lonesome chair, directly facing the wall. A puff of air shoots through my ear canal, and she puts the deformed headset behind my ears. I stare at the stuffed animal in a clear plastic box on the wall that is supposed to provide entertainment. The door shuts as she leaves, leaving me with only a stupid, childish fear and the ringing in my ears. The deafening silence pierces through me. I feel smaller even in this tiny cube, and I hug my knees toward my chest. I hardly notice when the beeping starts.

It’s been maybe two minutes of silence, but my sense of time is warped. Do I raise my hand? Did I hear a beep, or was it just a figment of my imagination? I can’t decipher the intentional high-pitched noises I need to pick out from the profound ringing. I regrettably decide to lift my hand, resigned to my cluelessness. I shut my eyes and wait for a lower beep to catch my attention and bring me back to reality.

After what might have been 10 minutes or 10 hours, the words begin. “Airplane. Baseball. Hotdog. Cowboy,” the recording says. I repeat these with confidence. The words become softer as they continue to play, and I squint my eyes. “Quilch. Muke. Sterm,” I repeat back with a wavering crack in my voice. My foot starts tapping. The little voice inside my head kicks itself for not identifying easy, elementary-level words. I anxiously squeeze my thumbs with clammy hands, the left harder than the right. My head pounds as unintelligible words spit back at me. I can’t keep up with the recording’s rapid pace.

I leave the booth with my chin low and my eyes lower. I tune her out as she relays the information from the charts; I hear bits and fragments of my results, but it’s nothing unfamiliar. “You can hear less than 50% of words at a basic conversational level,” she explains to me with a childlike tone. I shrug my shoulders carelessly, but my heart squeezes tightly inside my chest. I know why I’m here, but dread sears through me as she pulls out two small blondish brown-colored devices. My shoulders tense at the sight of them. I take a shuddering breath as she places the hearing aids in and around my ears.

22

I anxiously wait for an epiphany, expecting to be able to hear guardian angels from heaven. Instead, I was blasted with meaningless sound. “Is this what the normal world sounds like?” I ask myself. I sure hope not. My face grows warm as static and noise builds. My dad’s familiar voice sounds foreign and unrecognizable. Even my own voice is ghostly and hollowed out. I feel alienated from myself and dissociated from my senses. I want to rip the devices off immediately, but I decide against it for the sake of my parents’ insurance bill. Her smooth voice assures me that my brain will adjust with time. I wince with every syllable coming from her mouth as hot tears slide down my cheeks. She puts me through another round of perilous hearing tests, further bruising my dangerously low confidence. I let my hair down from its tight ponytail and walk out of the office in uncomfortable silence.

Two weeks later, I find myself watching cartoons again in the waiting room. My artificial ears amplify the TV volume even louder than it was before. I feel like a different person from the girl sitting in the same scratchy chair two weeks ago. I twist my ponytail around my fingers, and the call of my name breaks me away from the cartoons. She takes me into her office and asks me how I’ve been adjusting. Yes, I heard birds for the first time. No, I did not enjoy the experience. To my untrained ears, birdsong and the sound of screeching knives are one and the same. At this point, I am more focused on searching for words to explain the excruciating pain from the plastic manhandling my tiny ear canal. I was unaware that such small devices could inflict so much pain when they are supposed to help. It was like the hard receiver was expanding inside my ear, pushing farther than I could handle.

Frustration bubbles out of me. I whine like a child about the microphones screaming in my ear. All I wanted was to go to a movie theater and understand the dialogue. I wanted to be normal and have a normal conversation with my normal friends. I wanted to hear the fire alarm and the microwave. I exhale through my anger as static continues to mumble in my ears. My dad squeezes my trembling fingers as I breathe.

She fills my ear with a cold, fondant-like substance to refit my ear shape. She lets me play with the excess, and I squeeze it like playdough while I wait for it to harden. When the molds are done, I slip my artificial ears back on and gather myself as I walk out the door. This time, I can hear the cartoons loud and clear from the hallway. I exit the building as the howling wind whips my ponytail in my face. I slide into the passenger seat of my dad’s car as the engine roars, and head back to school as if it were a normal day.

Macy Crosser is a freshman majoring in Biology with minors in Chemistry and Medicine, Literature, and Culture at UNC-Chapel Hill from Kansas City, KS.

23

Eight-Armed Rose

Lasya Priya Kandukuri

Alzheimer’s! It’s a no brainer, Lisa says. And she laughs, and I laugh, and we are laughing together. We are falling over ourselves, despite the mountain on my chest because she dreams under spells and over rainbows, twisting her hair around a knuckle- a habit unforgotten even in sleep. Lisa searches the walls of her mind for words transcribed in tongues, decades held in candlelight under cruel shadows, a vigil for a language lost to its only speaker. Translated to the faithful in treasured remembrance, a lifetime entrusted to loved ones, trusting, when they tell you who you are and who all you have been, trusting, in their truth as your own. Undiluted, virgin truth, never untouched in love. Disobedient, slippery truth, running, turning the corner, catching at its shirt collar just beyond your grasp. Ghosts of memories haunting what’s missing.

Lisa knows all too well. In the mist she searches for what is lost under the rubble, the hunt fueled by the forgetting snapping at her heels, chasing the remembering that may never come. Caught between the two, the needle aligns itself north-south. Unearthed from below mirrors and magnetic fields, Lisa traverses the foundations of her fallen world, unfailing infallible, ever true in apocalypse.

Lasya Priya Kandukuri is a sophomore majoring in Neuroscience with minors in Chemistry and Creative Writing at UNC-Chapel Hill from Waxhaw, NC.

24

The Cradle

Lasya Priya Kandukuri

Aunt Lisa is a niece to me. I pat her back as she falls asleep, gently to the rhythm of her exhales just as my mother did for me. I brush the hair out of her eyes before saying goodnight. I ask her if she wants to blow her nose when she gets sniffly I press the soft tissue to her nostril. In the bathroom, we giggle over her tinkling. We wash our hands in ritual–hips bouncing, heads nodding–I direct her soapy palms under the water. And honestly, we can’t remember her birthday or her zodiac even when we go through all twelve months and all four seasons. We guess at the ends of her sentences, Question-marked, after the third or fourth word, but to Luna, Lisa sings her mother’s lullaby two verses in full, plants a kiss behind her fluffy ear before she begins, and again and again and again as she ends. Waking from a deep sleep, Lisa tells me that her mom isn’t doing–isn’t doing too well. I wipe the tears from the petal-thin skin beneath her eyes, and rock her back into sweet dreams.

Lasya Priya Kandukuri is a sophomore majoring in Neuroscience with minors in Chemistry and Creative Writing at UNC-Chapel

25

Hill from Waxhaw, NC.

Postpartum Insomnia

Lasya Priya Kandukuri

How long until the newly mothered learn again a full night’s sleep?

How long will it take Marc?

Made mother to his newborn wife, her diagnosis a childbirth, rebirth at 59 penetrating what was once pure, perforating the linings in permanent implantation, tearing large in laceration a gaping hole, in the place of new life, sucking away hers.

Marc cares for her as he would a child, the child he never had. loving, deep-seated–taxing, strenuous caring. Saying the right things, doing the right things, meaning the best things because anything less than best would be wrong. Keeping her fed, dressed and dressed well, tending to her sleep, even in his sleep disturbed by her discomfort. Waiting on her hand and foot and heart and, water for her throat, food for her belly, napkin for her nostril, tissues folded into fourths.

How long until the newly mothered learn patience? How long did it take Marc?

Newborn mother of 9 years and counting, love, the epidural that calms his overworked heart, love, in his veins keeping his watchful eye awake, love, the pacifier, the powerful, the patient, in love, Marc gives his wife her dignity in dementia, and in dementia, Marc mothers her, lays down his life in her love.

Lasya Priya Kandukuri is a sophomore majoring in Neuroscience with minors in Chemistry and Creative Writing at UNC-Chapel Hill from Waxhaw, NC.

26

Everything at Once

Soha Raja

I feel like a child, staring through a plastic kaleidoscope at the gift shop of a half-decent museum. But at the end of the tube I find abstract, shifting colorsand, centered, my own face staring back at me. Split. Broken. Multiplied.

My kaleidoscopic face is looking at me – she’s crying – she’s saying: It’s probably a stroke. Strokes are bad. The aftermath lasts forever. They just moved into a new house. Are they going to have to move again? Will he need more medicine now? Will he remember us? Will he even come home? If he doesn’t come home, then what? I should’ve called him more. The colors shift quickly, and I see my own face morphing into something new.

The kaleidoscope twists, I hear it click, and it settles onto its new axis. I focus on my face again, centered amongst the color. Her worried eyes scream at me. You have an exam. It’s a big exam. Step 1. You have to take it. You need to pass. What if you fly to Florida and study there? You’ll have to rearrange your schedule. Maybe do less practice questions. What if you can’t study anymore? You’ll have to put this off. What if the stress is too much? What if you never take this test? What if your plans end here too? I take a step back. I remove this prismatic barrel from my eye and hold this kaleidoscope, this children’s toy, in my hand. I need my most raw senses to carry me forward.

But I cannot register what is most important right now. I cannot predict what will be most important tomorrow. I do not know how to add myself into this shifting equation. I feel selfish for needing to squeeze in my own problems. He’s probably so scared right now. He can’t move. My family is scared. I can hear them force their unsteady voices into a pretend, monotone stability. It’s just one test, right?

I hear muffled breathing that does not belong to me, and conversations between others that I am not a part of. I shake my head to clear my mind from the vibrant colors that spoke to me just moments ago. I blink. It’s blurry, but I’ve been crying. I remember I’m on the phone. I feel its cold screen against my wet cheek.

“Don’t worry,” I say, “it’ll be okay.” It’ll be okay. He’ll be okay. You’ll take the test. We’ll all be okay.

I don’t know which version of me is at my lips, speaking my voice. I am willing myself to believe her. I am trying to be everything at once. I need all of me, healed, whole and unified to make it forward.

—Soha Raja is a fourth year student in UNC-Chapel Hill’s School of Medicine from Chapel Hill, NC.—

27

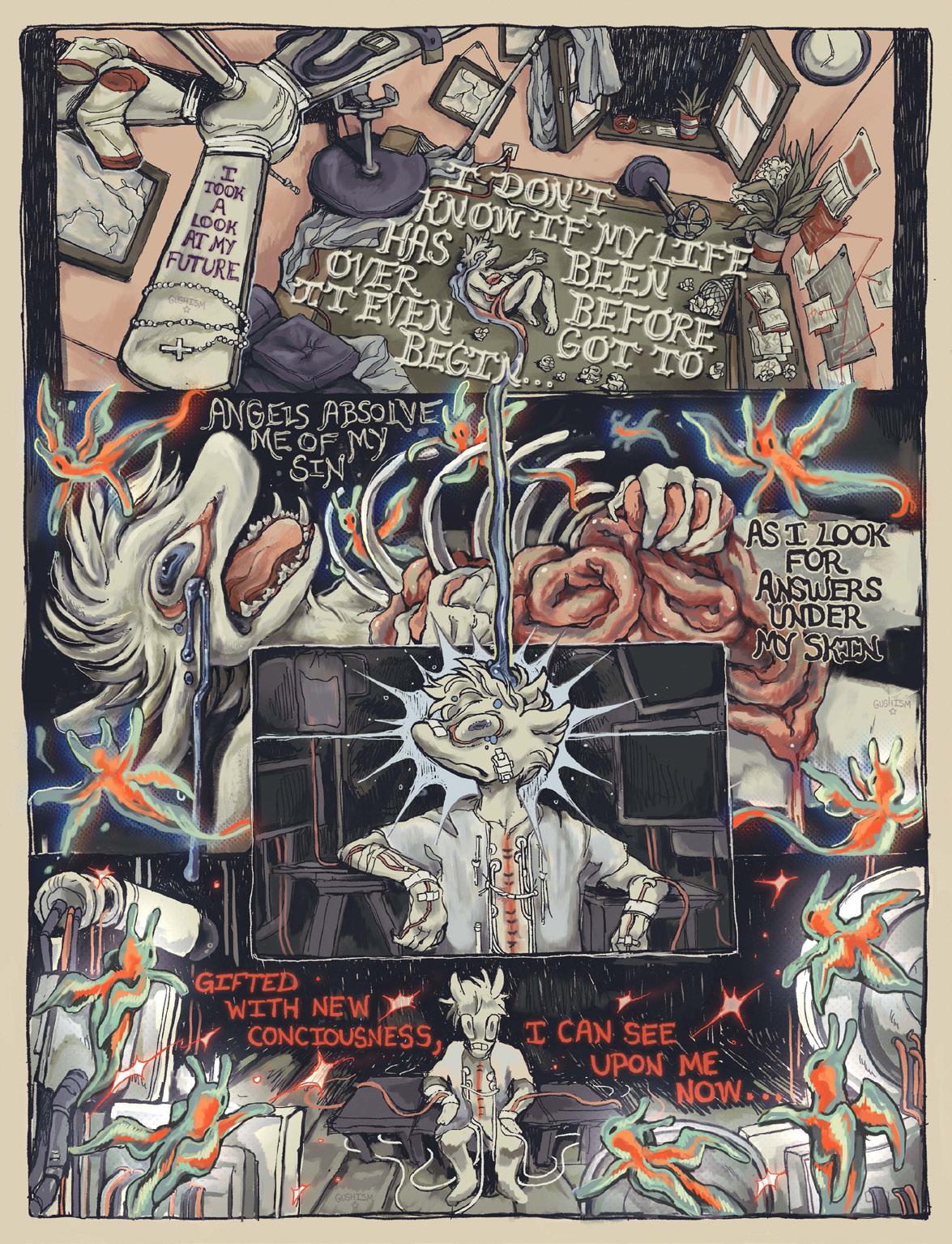

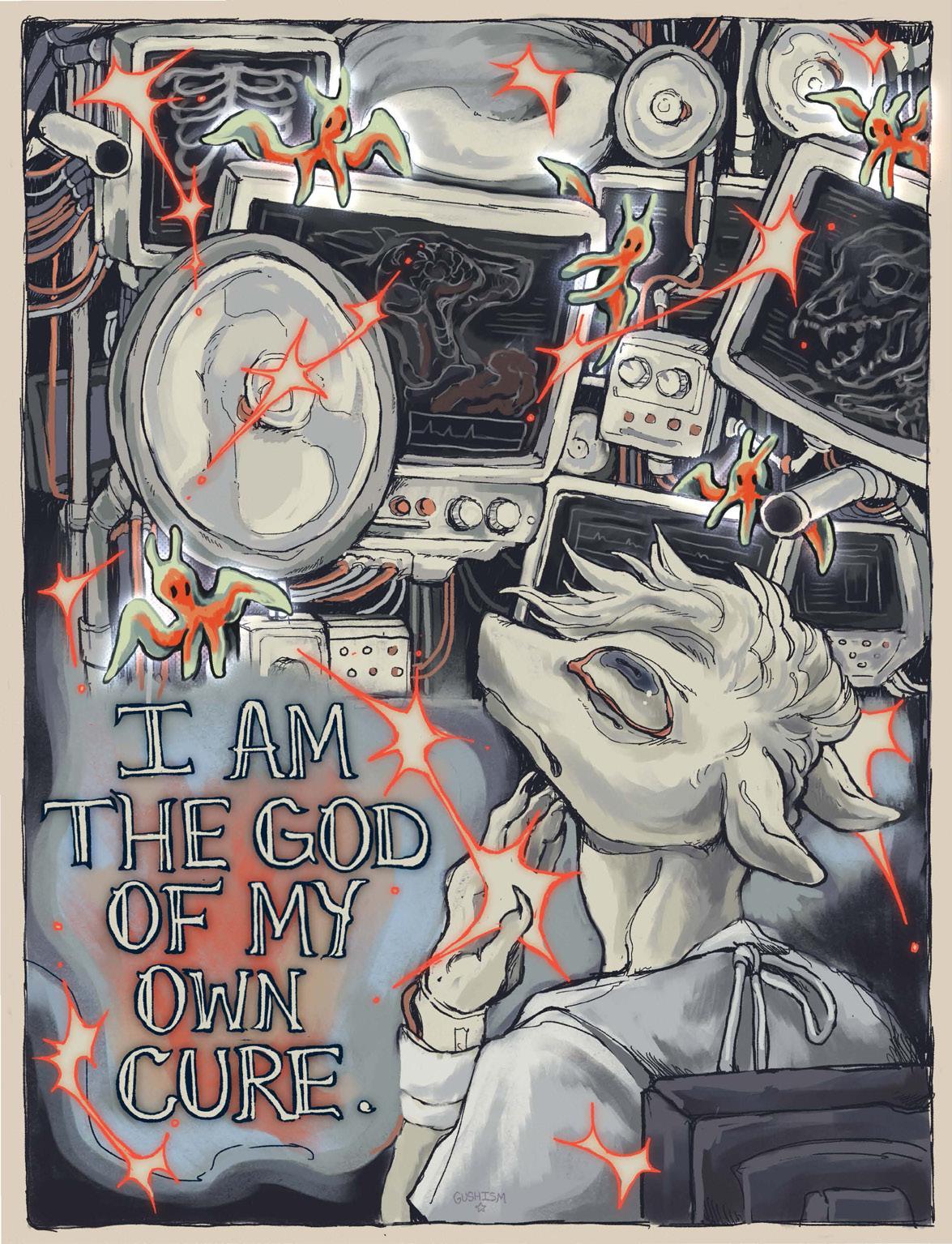

I Took a Look at My Future...

Anonymous

I made this comic after being hospitalized from my OCD and manic depression. The piece explores the moments of hyper-awareness and self-actualization that came with these experiences.

I’ve struggled with intense obsessions and compulsions from the onslaught of mixed signals from my own brain, and it led me down an ugly path of self-destruction roughly two years ago. Fueled by phobias and unwanted thoughts, I reached a breaking point. Nothing in the world made sense, and simply existing felt like a threat against my own brain. My skin felt too tight, the rooms kept changing sizes, people weren’t real, the pungent smell of rot haunted me everywhere, and there was always a feeling of bugs and bacteria crawling all over my body.

28

However, in these moments of chaotic brain activity and aggressive obsessions, there were rare moments where I could grasp at logic and ground myself. In those moments, the flittering ideas of logic and growth felt like angels gifting me these thoughts and dancing amongst my synapses. I realized that I’m the only person who can change how I think and rationalize fear, I’m the only person who can see the things I see so vividly and bring them into fruition, and I’m the only person who can bring change upon myself.

Having so much power in self-autonomy never felt like an option for me due to how my conditions warped my perception of my abilities to function and be an individual, but in those moments of helplessness in the sterile rooms of the hospital, I took hold of myself and the things I can do and have not loosened my grip since.

29

Saying Goodbye to Legends

Mya Webb

I said goodbye a long time ago. Not on the day you died, but many days before.

The first day came after I knocked on your door. Your feet dragged slow and your hands wrung knotty–Each knot tied with a purpose. Just like your legs. Millions of steps, planted with intention. Used to the very end.

That’s why they took your car...

Then put you in that unfamiliar bed…

You hated it, but those knots were holding you down.

The second day came when I saw you in that colorless room. A white smile, a red lip, a sparkling set of eyes. You, alone, shined brighter than that place. But you had to stay.

So the goodbyes became more frequent–Not in days we shared, But sprinkles in moments we felt.

I said goodbye when I brought you that poundcake you like. I gave a goodbye when I dressed you for Christmas dinner. I waved goodbye when your words became jumbled. I whispered goodbye when your eyes couldn’t focus. I cried a goodbye when we shared a long embrace.

There was never a goodbye in return, But your goodbyes were heard.

30

You said goodbye when you flashed a smile at me from your room. You gave a goodbye with every thank you. You waved me goodbye with every giggle. You whispered goodbye when finishing that cake. And I pray there was never a tear shed at the end of your days.

Our goodbyes were moments without words. Still, flickers of love illuminate in my mind. You, and your radiance, forever frozen in time. Fitting, for it meant that you, a Legend, Could never actually die.

31

Mya Webb is a fourth year student in UNC-Chapel Hill’s School of Medicine from Durham, NC.

I am no Soldier

Naomi Grace Christina Altonji

Do you have any relatives that have or had breast cancer? Yes No

Yes, I tick what seems like the 100th box on the 100th piece of paperwork I’ve had to fill out this morning. Each box reassures me more of what the doctor’s diagnosis is going to be.

To my right is the stack of brochures that the receptionist handed me with an oddly wide smile for the waiting room of an oncology center. All of them are different shades of pink, with that same damn pink ribbon stamped on the front. The top brochure has a picturesque family on it, a mother, father, and a son, all holding each other with candid, cancer-free smiles. Maybe it is meant to be an implicit promise? Something to look forward to? An inspiration to fight? I don’t know, I don’t care. All of it is just a well-choreographed dance around the topic at hand, indicated by the small white text at the bottom of the page: Treatment Plans for Metastatic Breast Cancer.

Well, page 2 will definitely kill me. Page 4 will kill me just a bit slower. Page 7? Doubt I will make it off the table.

I sigh.

Death is still death no matter what pretty shade of pink you paint it.

I slump back into the cold couch. Holding myself upright is getting more and more tiring nowadays. The tumor in my chest weighs down my frail body like an anchor; its existence is beginning to outweigh mine. I’m sure

32

Chemotherapy ………………………………………………………….. 2 Radiotherapy ……………………………………………………………. 4 Hormone Therapy ………………………………………………………. 5 Lumpectomy………………………………………………………………7 Mastectomy ……………………………………………………………… 9

that is supposed to make me panic in some way. But the twiddling thumbs, shaking legs, and nauseating stomach pain that should accompany me on a day like this packed up and left long ago.

An awkward silence has consumed the waiting room. Even in the Novant Health Breast Cancer Institute, cancer is still a taboo. The all-beige tables, seating and hardwood floors do little to boost morale, nor the plethora of posters covering the walls. Splatters of pink and ribbons and more happy families who have never met a cancer patient in their lives. Pink. So much pink. The amount of pink around me is nauseating like the oncologists forced rose-colored glasses over my eyes in a futile attempt to tell me everything is perfectly fine.

I wonder if they know cancer is spelled the same even in pink, I think.

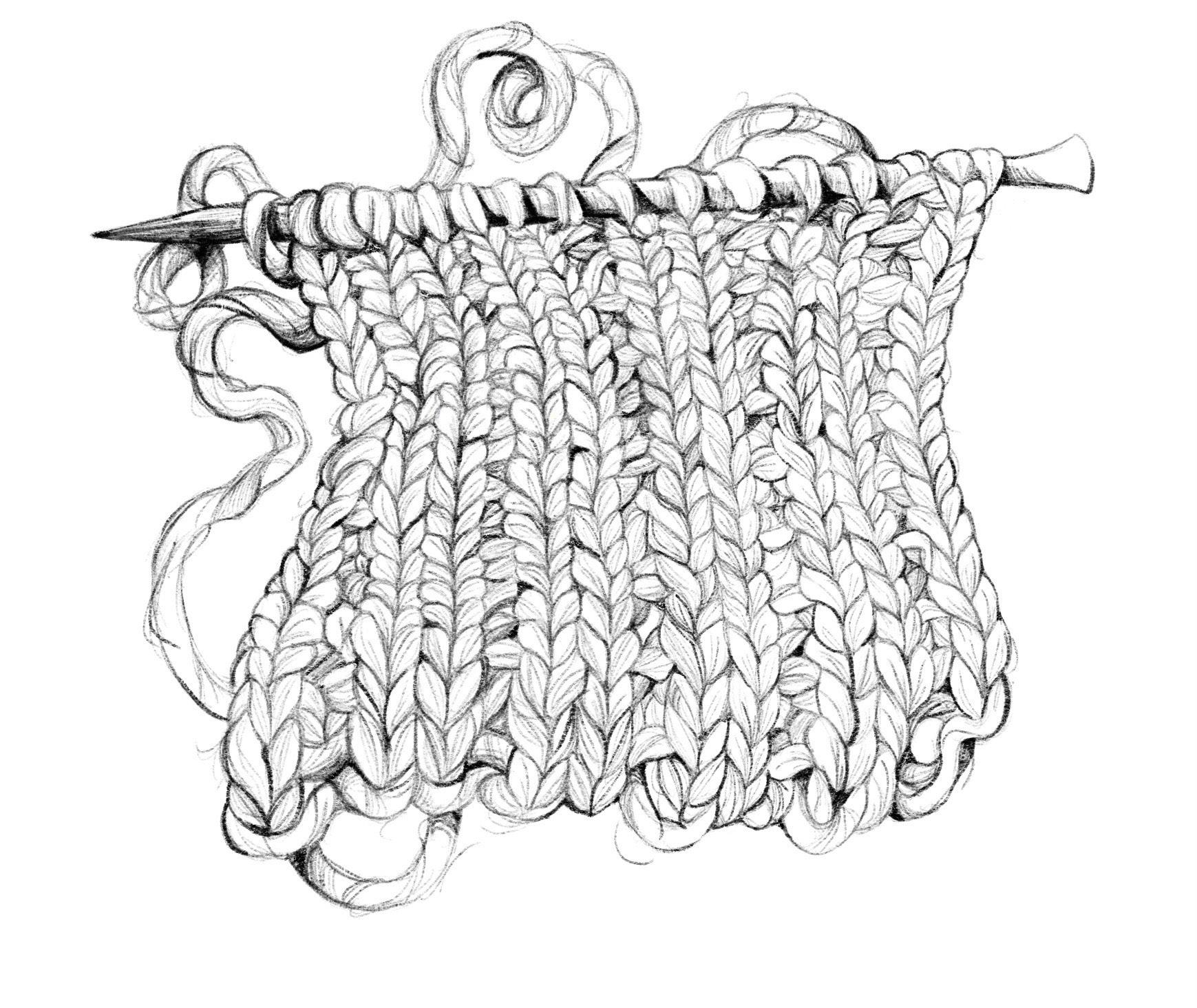

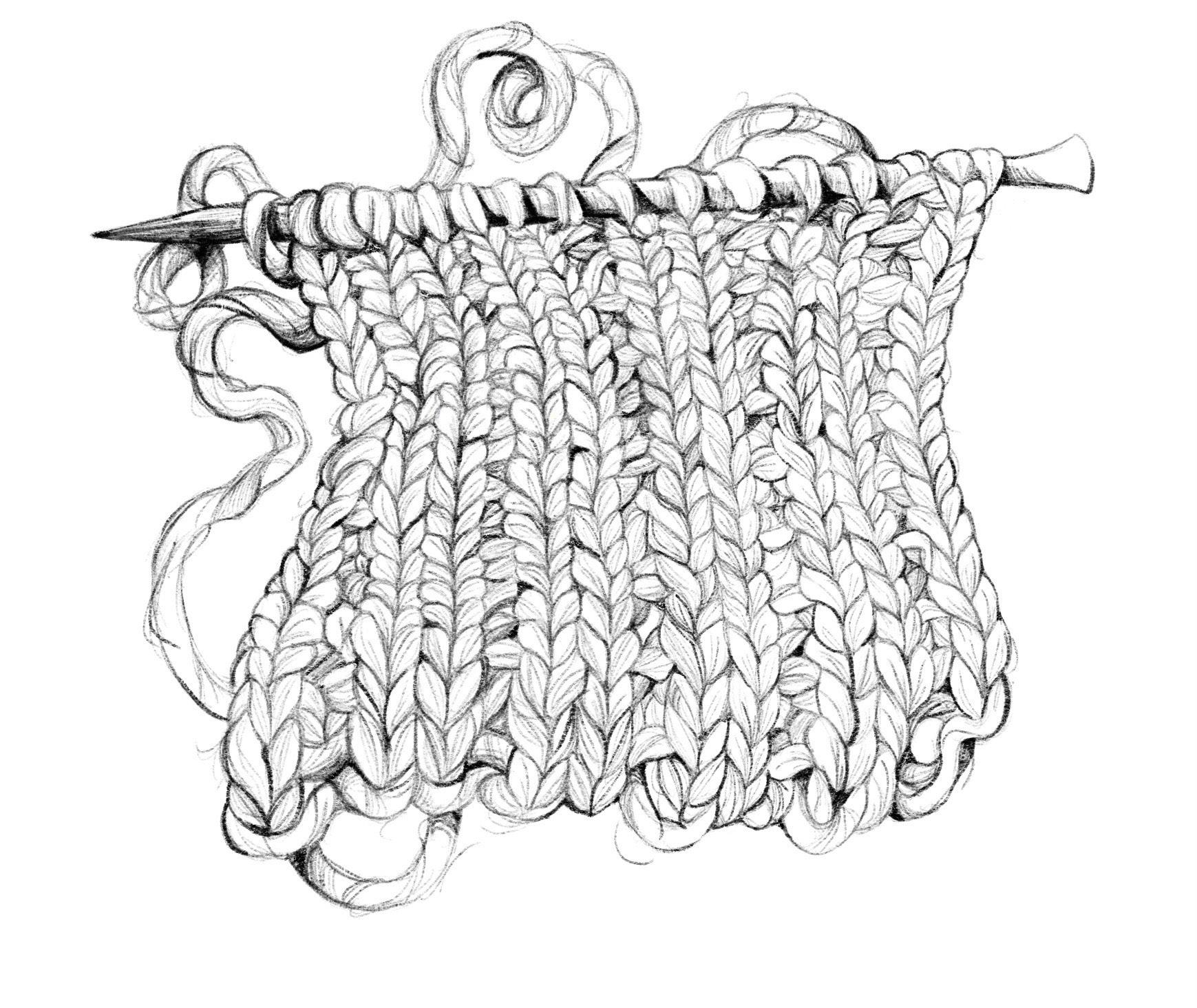

An older woman sits across from me; she is maybe in her mid-60s. She is smart, bringing something to do—unlike me, whose only entertainment is critiquing the interior decorations of this waiting room. She knits what looks to be a scarf. My mother has been trying to teach me to knit, but I can’t quite get the hang of it. I examine her hands as she loops the yarn around her knitting needle. She is slow, not with the concentration of a

33

novice, but with the lack of energy to go any faster. Her veins are dark blue and her skin is dry, splitting where her fingers meet her palm. She and I are wearing the same shade of red nail polish.

But it is not her hands that strike me. Nor is it the pink bandana, wrapped around her head, that makes me hyper-aware of the way my curls feel against my neck. It is her eyes. I’m sure her eyes have seen a million of those damn pink ribbons stapled on shirts. I’m sure she has been told by a million people how strong she is, how much of a fighter she is, and how God gave her the toughest battle as one of His strongest soldiers. This woman is no soldier. The look in her eyes is not that of a warrior prepared to fight. Her eyes are tired, defeated, and in pain.

Looking at her feels like looking into the future. Ironic, I don’t think I will make it to her age. As I see her, I see what is coming for me.

“Naomi Altonji.”

The solemn silence of the room is suddenly broken. The nurse who calls my name is wearing that same receptionist smile.

“We’re ready for you now! You can come on back this way.”

The woman averts her gaze away from her knitting and locks onto me. When she sees how young I am, her eyes become a tearful, convoluted mixture of shock, pity, and fear—a maternal fear. That fear a mother has when they let their child try something on their own for the first time; knowing that they are going to fall, that it is going to hurt but that they have to let them go anyway. The few seconds I meet her eyes feel like a lifetime. Right now she knows me better than anyone else.

“Right this way, we’re going to take good care of you!” the nurse interrupts in her customer service voice, ushering me down a cold sterile hallway, away from my friend. Her string of well-rehearsed, superficial niceties begins to fade into a continuous ringing in my ear. Everything around me starts to blur as I haul my exhausted body closer and closer to my sealed fate. This is a fight I will not win, for God knows I am no soldier.

—Naomi Grace Christina Altonji is a freshman majoring in Biomedical Engineering at UNC-Chapel Hill from Charlotte, NC.—

34

Seeing “The Other” in the Psych Ward

Kathryn Watkins

I found myself thinking about the power of diagnoses as stigmatizing labels while the psychiatric resident and I interviewed Ms. M. The resident took notes as Ms. M described pacing up and down the hall yesterday. Ms. M’s flat affect, downcast gaze, and occasionally tearful eyes betrayed her admission diagnosis: Major depressive disorder, chronic, recurrent. After all, she was admitted to our geriatric psychiatry ward for intentionally overdosing on 114 Prozac tablets. For the past week, she had mostly stayed in her room, huddled in the fetal position on her bed. During our interview, she admitted that she had started pacing to “preserve her strength”. As the resident typed, I noticed her write, “Possible somatic delusions related to losing all her strength if she stops pacing hours a day.” At first glance, the resident’s note was a competent summary of what Ms. M had laid out for us. I was struck by the note, however, because Ms. M’s statement seemed rational to me, consistent with her persistent negative outlook stemming from her melancholia. I could imagine myself catching up with friends over coffee or calling my parents on the phone saying something similar about wanting to stay active. In fact, I had experienced a similar resting agitation when studying for Step 1, a major medical accreditation exam. After a long day of staring at a screen, my muscles yearned for a good run. If I were in Ms. M’s place, wouldn’t I also seem delusional? The only thing protecting me was a seat on the doctors’ side of the table.

The psych resident’s automatic mental leap to label Ms. M’s movements as pathological stems from a common, often unconscious phenomenon in medicine: “medicalization of the other.” Originally coined by medical anthropologists, the phrase succinctly captures how easy it is to label someone or something as pathological if we do not easily identify with them. As doctors, it can be thrilling to “discover” a medical or psychiatric sign, symptom, or diagnosis. These “discoveries” allow us to then develop a treatment plan and start trying to “fix” whatever we deem abnormal. It gives us a purpose and justifies our grueling training. But, calling something abnormal confers automatic stigma and creates a hierarchical relationship between the patient, who is the pathology embodied, and the doctor, who is the judge, jury, and executioner all in one.

35

Recognizing that the empathy I felt for Ms. M could blind me to a potential real, treatable issue, I tried to see things from the resident’s point of view. Ms. M’s new activity was a dramatic departure from her baseline of lying in bed all day. When she paced, she walked with her head down, frowning, appearing driven by some inner compulsion. She walked back and forth down a short hallway for hours without talking to anyone. She remained adamant in our daily interviews that she had no will to live and wished to die immediately, yet she voiced consistent concern about losing strength. In every interview, she catastrophized about the course of her future and her familial relationships. It seemed she could imagine nothing positive happening to her anymore. Maybe the pacing was an inner compulsion driven by one of her negative, delusional ideas of failing health and failing relationships. Or perhaps the true etiology had nothing to do with her negative thoughts at all.

As her medical team, the resident, attending, and I agreed that her pacing was likely a delusional complication of her depressive state but decided to cover our bases by ordering a TSH, a thyroid test. To our surprise, her TSH returned elevated. Ms. M had received medical and psychiatric care for a week in a highly-regarded medical institution and no one had thought to look for medical causes of her symptoms since she had a history of depression and suicidal attempts. The level of her thyroid hormones indicated that she probably had poor thyroid function, which can cause, among other things, muscle stiffness, depression, and cognitive slowing. We increased her thyroid medication and continued her psychiatric regimen. She continued to receive ECT (electro-convulsive therapy, a highly effective short-term treatment for suicidality) three times weekly, and we gradually increased her low-dose depression medications. Gradually, Ms. M began to receive visitors and returned to reading, one of her favorite former hobbies, even asking the medical team for recommendations. The resident and I gave her reading assignments about patients who had successfully recovered from depressive episodes as well the romantic novels she preferred. Her pacing decreased in frequency and duration as she spent more time reading and having long visits with family. At the time of discharge, she remained depressed but no longer suicidal, having gained the hope that she would be accepted by her friends and family upon returning home. She made more eye contact and walked with a leisurely pace. Staff reported that she still circled the halls at nighttime but was redirectable. No one on the medical team knew exactly why she walked, but it could have been her thy-

36

roid problem all along that tipped a melancholic, anxious woman over the edge into a depressed, suicidal pacer with stiff muscles. Medicalization is what led her medical team to initially label her as delusional before we had all the puzzle pieces in place. Medicalization turned walking into a pathology. Right before leaving, she told me, “I have to stay strong for my family. They care about me so much. That is why I walk.”

—Kathryn Watkins is a fourth year student in UNC-Chapel Hill’s School of Medicine from Winston-Salem, NC.—

37

Worry Worm Anonymous

Have you ever wanted to take your brain straight out of your head and get to the bottom of what is causing all of your worries? I made this sculpture to do exactly that, and the Worry Worm has become a great symbol of overcoming anxiety for myself and my friends. Making something with my hands rather than creating images through drawing opened avenues for both making new work and providing a creative outlet that, ironically enough, soothes my brain.

I keep the Worry Worm on shelf display in my studio. When I begin to get worked up and knocked off track of doing things I want and need to do, it’s a stark reminder that anxiety is simply a very colorful intruder in my head. I’ve received multiple comments from peers, such as “How’d you get a scan of my brain?” and “Oh, so that’s what’s been causing all my problems!” and these sorts of responses, despite how brief and comical they are, bring me so much joy and motivation. It’s very heartWORMing for me to see how this piece has resonated with so many people in wholesome and humorous ways!

38

An Illness Narrative

Mae Brockman

It is winter and the air is stale. Lying in bed, John observes his right hand. His fingers tremble, as though rolling an invisible pill between his forefinger and thumb. For months, his body has carried a deep knowledge that something is wrong. When writing patient notes, his handwriting is collapsed and cramped. When his wife says, smell this, all he smells is air. On weekends, John drives to the mountains to spend hours on the peaks. With his worsening pain, his legs disobey him and he veers off course. He loses stamina in the frigid Pennsylvania air and has to clock out early.

John wonders if this is how aging is supposed to feel. He visits a chronic pain specialist who notes that his muscles are abnormally stiff and recommends he see a neurologist. John lies silently as an MRI whirs around him. The next day, he drives to LabCorp, and vials of his blood are drawn and packaged. When he returns to the office, the neurologist tells him he has Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by dysfunction of the substantia nigra region of the brain, which produces dopamine. Dopamine is essential for pleasure, movement, and cognition (Schmidt 2006, 63). In Parkinson’s disease, however, dopamine production is stalled. By the time the disease presents, the damage is permanent. No treatments to cure Parkinson’s exist. Symptoms can be managed using levodopa, a precursor compound of dopamine. As Parkinson’s disease progresses, however, the impact of levodopa plummets (Schmidt 2006, 63).

For decades, John worked as a nurse practitioner. When the reality of the diagnosis settles over him, John thinks of the Parkinson’s patients he cared for. They spoke so softly that he had to lean forward to hear what they were saying. They moved slowly and deliberately, with rigid faces. On each visit, he would watch their symptoms worsen. There was little he could do to relieve their pain.

For seventeen years, John and his wife, Sandra, have lived in a condo in Norristown. Their apartment is near an elementary school and has large windows that overlook a creek. The walls are lined with hundreds of books.

39

John has complete collections of the Beat Poets and William Burroughs, and he and Sandra are happy to spend any day blissfully immersed in reading.

When John receives his Parkinson’s diagnosis, he immediately retires from his work. He and Sandra apply to a nearby retirement community. They have too many books to fit into their one-bedroom apartment at the retirement community and no children to give them to. John creates an eBay account and starts uploading images of the books, listing them as “free.” It pains him to watch the artifacts of his life shift into someone else’s.

At the retirement community, there is a shared understanding that everyone suffers. Friends and family members pass and new illnesses develop. Residents have learned to live with pain. Each day, John observes Parkinson’s patients in the late stages of their illness. They are wheelchair-bound and seem lethargic and distant. The patients require aides who feed and clothe them. “It’s more the anticipation at this point than anything else,” John explains. “I think it’s made me a sadder but wiser person.” He knows that not all Parkinson’s patients progress to the final stages of the disease, most often because they die of something else. John hopes this is the case for him.

Although John considers himself to be in the early stages of Parkinson’s, he has noticed changes. Sometimes, traveling along the narrow hallway of his apartment, an invisible force seizes him and he freezes. Buttons are nearly impossible. Packaging defeats him; opening a chocolate bar, he uses his teeth to tear the shiny plastic. Walking along the community trails, he notices his steps becoming smaller. He winces and forces his legs to return to his normal gait, like a toy soldier.

John remembers when he was young and he hiked the Appalachian trail. The nights were cold, and he carried his belongings on his back. He watched the foliage change, and hung his food from trees to deter bears. Health meant the absence of pain. He spent days without any distractions and adapted to fill what was missing. “Now,” John says, “health means adjusting to your situation and learning how to play the cards that you’re dealt. And doing the best you can at finding some serenity.” He adds, “And finding someone good to love.”

40

Every morning, John waits for Sandra, who helps him roll and button the sleeves of his shirt. John can feel his body coming undone, the synapses of his mind unraveling, but he knows he can depend on his wife. She has been an endless source of comfort as he faces the precarity of his illness. “They always tell you when you’re diagnosed, that you don’t know how fast it’s going to progress. You just don’t know.” He pauses. “But I know that in the meantime, I will do the best that I can.”

All original names have been changed to protect the identity of the subject.

References

Anonymous (retired nurse practitioner) in discussion with the author, December 2023.

Schmidt, Konrad, and Wolfgang Oertel. “Fighting Parkinson’s.” Scientific American Mind 17, no. 1 (2006): 64-69. doi:10.1038/scientificamer icanmind0206-64.

—Mae Brockman is a freshman majoring in English on the pre-medical track at UNCChapel Hill from Philadelphia, PA.—

41

Seven-Year Gap

Celia Gibbs

My little brother loves me more now that I’m gone, mini mother turned sister again with distance and time and our Mother’s healing tracked by bills. He loves me more since he met his girlfriend, their middle school love a sweet and secret thing until he told me.

We’re the children of a deacon and a cancer survivor, those who must be more moral to come so close to God and death and to make it through with a story to share.

My brother’s thirteen-year-old heart is a ripening peach, as easy to bruise as my shins and thin skin. Before, when home meant together and I was still taller and our mother rested from bodily malfunction and our father’s face sagged with the weight of the world and hospital debt, when the fighting got too loud he’d sleep in my bed, mashing his little-boy-hot-head into my pillow until my fingers rubbed his eyes to sleep.

He says he loves me more, more than what I’m not sure. When I turned eighteen he left me to spend the day alone, his true blue chipped by the sharp edge of a hurting heart anticipating the leaving.

I am sure that we’ll never be this close again.

—Celia Gibbs is a junior majoring in Creative Writing and minoring in Writing for the Screen and Stage at UNC-Chapel Hill from Tuxedo, NC.—

42