Welcome to the autumn issue of your Historic Scotland magazine, packed with stories and ideas that will have you heading for a property near you before you can say ‘neepie lantern’.

Joinusforatourlikenootheronpage18and discoverhowtakingadifferentviewcanunlockthe ‘evolution’ofoursitesandrevealpreviouslyunknown heritagethatneedsprotecting.

Inthethirdofoursensorytimetrips,onpage32,we experiencejourney’sendforafootsorebutawestruck medievalpilgrim.And,onpage26,wedelveintothe OldNorsesagas,wherethemistsparttorevealsome veryfamiliarplaces.I’malsodelightedtointroduce someofourCraftFellows,onpage40,whoseworkand skills–supportedbyyou,ourmembers–arecaringnot justforourpropertiesbutforotherheritagesitestoo.

You’ll also hear about ways to celebrate the Scots language this autumn, and there’s a trio of castles just perfect for seasonal adventures. Head to events on page 52 for plenty more to see and do over the next few months, including Halloween highlights. You can even start planning ahead for the festive season – it’s never too early!

CLAIREBOWIE Head of Membership & CRM

KELLYAPTER is an arts writer for The Scotsman and The List, and Editor at Creative Lives.

PAGE 18

This autumn our Great Big Living History Week sees properties across Scotland brought vividly to life by our re-enactors, from medieval knights to tuneful musicians. These fascinating characters will share tales of the past and whet your appetite for more. Turn to page 11 for further details.

TOMFAIRFAX is a researcher working on Icelandic sagas and medieval Scotland.

PAGE 26

HANNAHBROWN is an Interpretation Officer, who helps bring our sites to life for visitors.

PAGE 32

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT

SCOTLAND

Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH 0131 668 8600

historicenvironment.scot

Membership enquiries

0131 668 8999

members@hes.scot

Editorial enquiries

members@hes.scot

Head of Membership & CRM

Claire Bowie

Membership Marketing Manager

Julia Haase-Wilson

Editor Indira Mann

indira.mann@ thinkpublishing.co.uk

News Editor

Jonathan McIntosh

Design Matthew Ball

Managing Editors

Andrew Littlefield

Sian Campbell

Advertising Sales

Jamie Dawson jamie.dawson@ thinkpublishing.co.uk 0203 771 7201

Executive Director, Think John Innes

john.innes@thinkpublishing.co.uk

Think 65 Riding House Street London, W1W 7EH 020 3771 7200

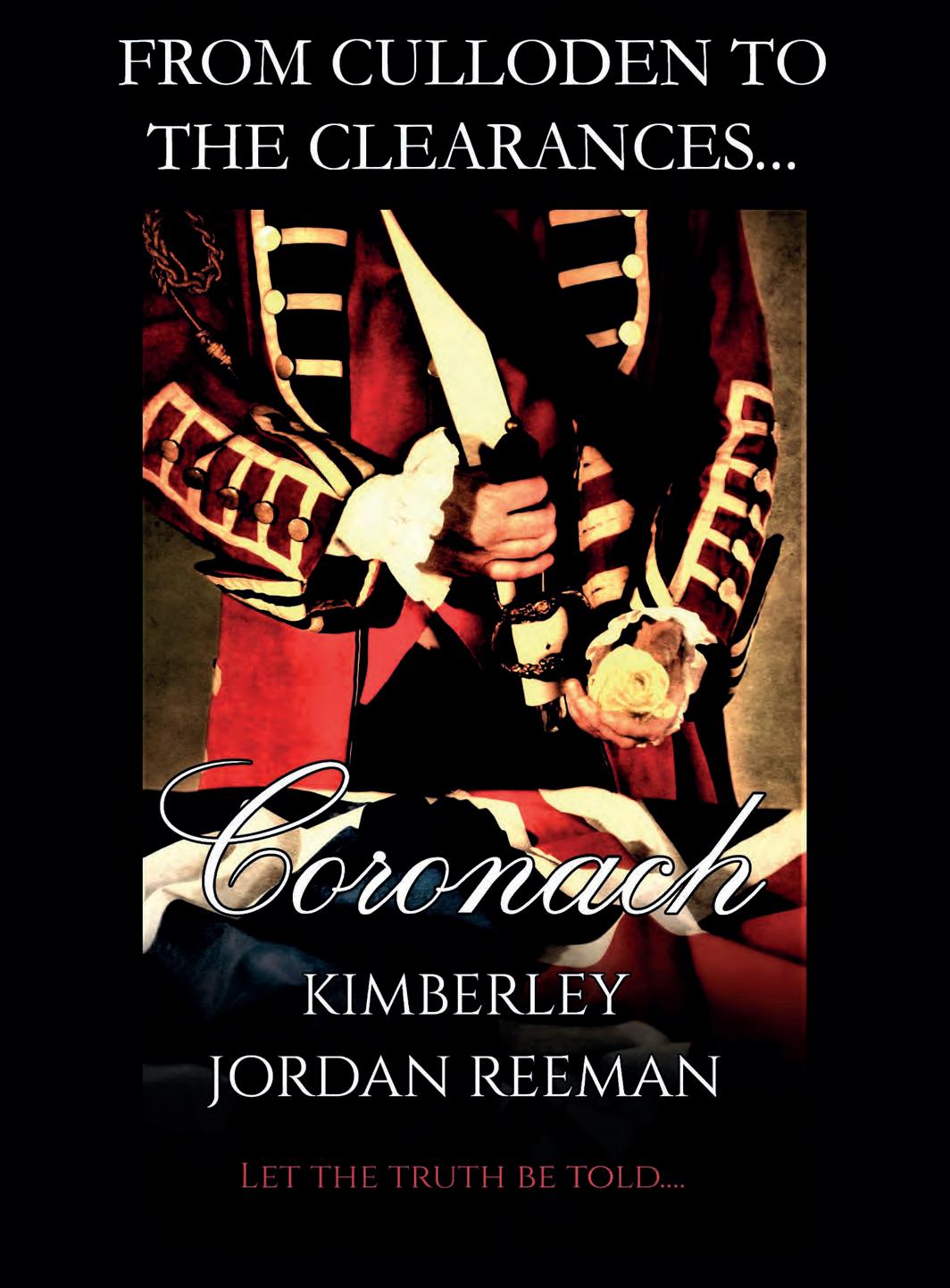

Cover images

Angus & Amelia Photography

Shutterstock

Photography

All images provided by Historic Environment Scotland unless otherwise stated. For access to images of Scotland and our properties, call 0131 668 8647/8785 or email images@hes.scot

Historic Scotland is published quarterly and printed on Galerie Brite Bulk, which is certified as coming from well managed forestry.

The views expressed in the magazine do not necessarily reflect those of Historic Environment Scotland. All information is correct at the time of going to press.

© Historic Environment Scotland. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or in whole is prohibited without prior agreement of the Membership and CRM Manager of Historic Environment Scotland.

Historic Environment Scotland (HES) is a Non Departmental Public Body established by the Historic Environment Scotland Act 2014. HES has assumed the property, rights, liabilities and obligations of Historic Scotland and RCAHMS.

Visit hes.scot/about-us

Scottish Charity No. SC045925.

On site with Craft Fellow Cat Hotchkiss as she helps rebuild the Crannog Centre

Follow the faithful to a medieval Mass in Glasgow Cathedral

13

18

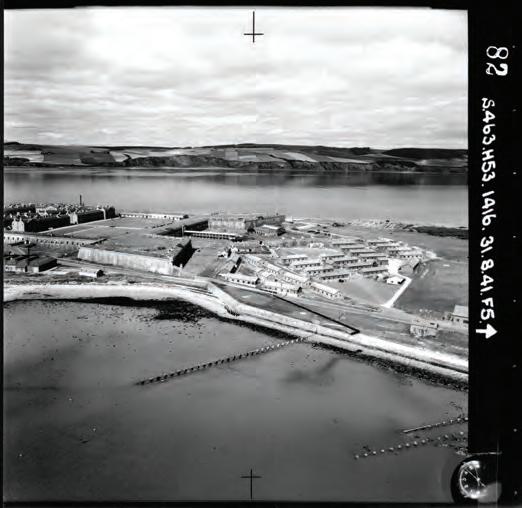

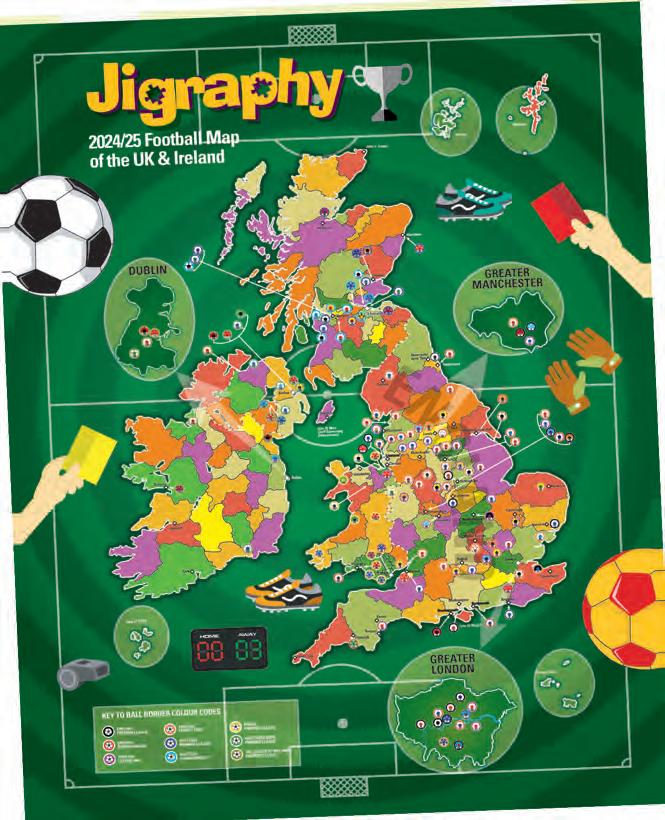

A bird’s eye view of Blackness Castle shows why it’s affectionately termed ‘the ship that never sailed’

6 THE SCRIPT

Your guide to experiences at our properties this autumn

16 SPOTLIGHT

48 SHOP

52 EVENTS

Great days out for all 56 TIME TRIP

FEATURES

18 ABOVE AND BEYOND

How aerial views give new perspectives on our sites

26 WHAT’S THE STORY?

The Norse literature shedding light on our past

32 PILGRIM’S PROGRESS

Head back to a medieval Mass at Glasgow Cathedral

40 IN THE VERNACULAR

Meet the Craft Fellows keeping traditional buildings and skills alive

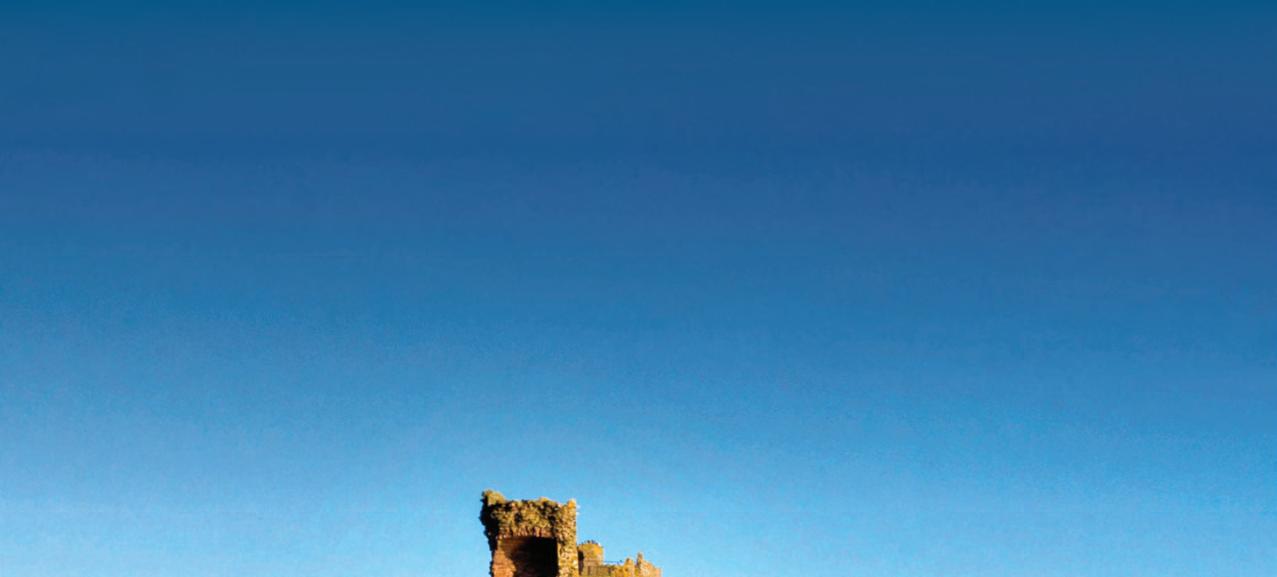

Perched high on a cliff edge commanding dramatic views of the Bass Rock and the Firth of Forth, these impressive ruins have withstood almost seven centuries of war and weather

This mighty medieval castle was built in the mid-1300s for William Douglas, who became 1st Earl of Douglas in 1358 after murdering his godfather, Sir William Douglas of Liddesdale. By the 1380s, the house of Douglas had split into two factions and Tantallon Castle passed to the junior line, the earls of Angus, known as the ‘Red Douglases’. It was then inherited by George Douglas, the Earl of Douglas’ illegitimate son. This family branch reigned over the castle for the following three centuries, fortifying it

for battle and having regular skirmishes with the Crown.

As a coastal fortress, Tantallon survived numerous sieges during its active duty, including attacks by James IV in 1491 and James V in 1528. However, it was eventually devastated by a bombardment unleashed by Oliver Cromwell’s troops in 1651. The castle’s ruins were never repaired and much later it served as inspiration for writers, such as Robert Louis Stevenson and Walter Scott.

Enjoy amazing views over the North Sea to Bass Rock and its seabird colonies. Look up at Tantallon’s impressive curtain wall –one of the best examples of 14th-century castle architecture in Scotland.

There’s currently no visitor access to the east tower and doocot.

Tantallon Castle is 250 metres from the visitor centre, along a pathway and over a timber bridge. There’s an adapted toilet 40m from the visitor centre. DOGS Visitors’ dogs are permitted, but must be kept on a lead at all times.

Situated 30 miles outside Edinburgh and under three miles from North Berwick. Travelling from Edinburgh by car takes 50 minutes. There’s a car park 400m from the visitor centre. Take a train from Edinburgh to North Berwick then walk five minutes to Beach Road to catch bus 120 (towards Dunbar).

The Engine Shed throws open its doors

Join our Doors Open Day Engine Shed sessions on Saturday 21 and Sunday 22 September to discover how our building conservation centre promotes traditional skills vital to maintaining Scotland’s built heritage.

This ‘behind the scenes’ event is being run as part of celebrations marking the 900th anniversary of the Royal Burgh of Stirling.

The two-hour sessions are completely free and take place on both days from 10am to 12pm and from 1pm to 3pm. Booking is essential.

For more information, see engineshed.scot/whats-on

SEE ALL EVENTS ON PAGE 55

Follow in royal footsteps during a special tour that’s only for members

As a Historic Scotland member, you’re invited to enjoy an exclusive tour of Holyrood Abbey on 15 September. You’ll be led by expert guides from the Royal Collection Trust, who’ll share their knowledge of this fascinating property –located in the grounds of Edinburgh’s Palace of

Holyroodhouse – and the role it played as a residence and final resting place for Scotland’s royalty. Starting at 11am and 3pm, tour tickets cost £5 and include a guided tour of the palace gardens. Advance booking is essential. Log in to book at hes.scot/member

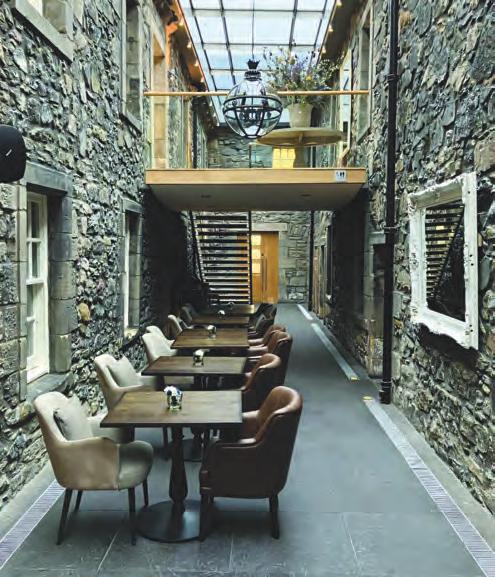

Tuck in to something tasty at Edinburgh Castle’s newly refurbished eatery

Treat yourself or someone special to coffee and cake or afternoon tea in Edinburgh Castle’s recently refurbished Tea Rooms. Historic Scotland members enjoy a 10% discount. Serving a delicious range of cakes, drinks and cocktails, the newly refreshed Atrium and bar are also great spots to unwind after enjoying the castle’s hustle and bustle. Book your afternoon tea at edinburghcastle.scot/ afternoon-tea

The Tea Rooms at

See autumn colours in full swing at these strongholds

DOUNE CASTLE

The grounds of this star of the silver and small screen offer a woodland walk that’s ablaze with autumnal hues.

Craigmillar Castle’s Halloween Shenanigans

Trinity House’s seafaring treasures reveal stories of Black history and global connections

Join Trinity House’s Black history tour on Friday 4 October, Friday 11 October or Friday 18 October to learn about the links between maritime Leith and Black history around the world. As you’re guided around the house, fascinating maritime collections will illustrate a range of these seldom-told stories. For times visit hes.scot/whats-on

Dress up in your best costume for Craigmillar Castle’s Halloween Shenanigans event on Saturday 26 and Sunday 27 October.

Running from 11am to 3pm, the event promises terrifying tales from our storyteller Ravina, and a selection of bone-rattling riddles and songs.

You can also join the Potion Maker’s Trail at Craigmillar Castle and other sites during October. See page 52 for more Halloween events

DUNSTAFFNAGE CASTLE

With beautiful broadleaved woodland surroundings and a view over the Firth of Lorn, you need to tick this fairytale fortress off your autumn must-visit list.

BLACKNESS CASTLE

From a royal residence and garrison to a state prison, Blackness Castle has played many roles. Today, its foreshore and mudflats are amazing spots to see overwintering birds preparing for the chillier months. Plan your next adventure at historyawaits.scot

created a digital

To mark the 437th anniversary of her death, we’ve made a digital 3D model of Mary Queen of Scots’ face. This model is based on a plaster cast taken from Mary’s tomb effigy at Westminster Abbey. Now displayed at Linlithgow Palace, reportedly this plaster cast was once owned by Sir Walter Scott.

Yueqian Wang, our Digital Innovation Trainee, developed the 3D model as part of her traineeship. This two-year training programme sees Yueqian work alongside our Digital Documentation and Innovation team, in partnership with National Trust for Scotland, to document in 3D the properties and objects in our collections.

This 3D documentation work uses new technologies

to widen public access while increasing understanding of Scotland’s history.

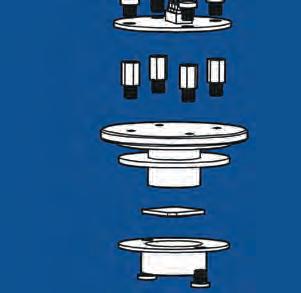

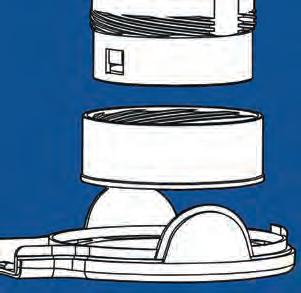

Using a wide range of learning resources from the Engine Shed, this 3D model was created via photogrammetry, a process whereby hundreds of

overlapping photographs are taken around the object and analysed by software to work out their relative position. These photographs are then used to create an accurate photorealistic 3D model.

“I’ve always been interested in sharing stories

Yueqian is our Digital Innovation Trainee

from history with a wider audience as well as the practical side of heritage conservation. Digital innovation is a perfect approach to working in both areas,” says Yueqian.

“The traineeship has given me the chance to work on fascinating projects, go on site visits across Scotland, see historic objects up close and learn how cutting-edge technology can be used in the heritage sector.”

See how this model was created at hes.scot/ mqs-model

Meet our Digital Documentation and Innovation Team at our Members’ Exclusive Event at the Engine Shed on Tuesday 26 November. More details on p55.

Join our community excavation at Dundonald Castle

We’ve partnered with Friends of Dundonald Castle and AOC Archaeology for another community excavation at the castle between 21 and 28 September.

The stone stronghold you see today was built around 1371 for King Robert II and sits on the site of two probable earlier castles. Evidence has also been found of an Iron Age or early medieval hillfort and roundhouses dating from around AD 500

to 1000, and the presence of imported pottery suggests the people here were part of a trade network extending from mainland Europe to Scotland.

We’re looking for volunteers to get involved in the Dundonald Castle dig to help give us a better understanding of the site’s story over the centuries. Taking part is free and all equipment is provided.

For more details, visit dundonaldcastle.org.uk

Become one of our Visitor Connector volunteers

Explore our properties this autumn and you might meet a Visitor Connector volunteer.

Whether delivering tours, leading activities with crafts and handling collections or sharing stories of our sites, Visitor Connector volunteers are here to make your day as fun as possible. We encourage

the volunteers to use their knowledge and passion to engage with us and shape their individual volunteering activities. This way, we can match the interests of our volunteers with opportunities to share our sites’ stories. Visit our website to see the available Visitor Connector opportunities.

Lug in tae oor first Scots audio guide at

Fiona Davidson, Learning Officer, on ways to celebrate the Scots language this autumn

If you’re keen to find out more about the Scots language, here are three autumn highlights.

Our ‘David I: A Revolution’ exhibition marks the 900th anniversary of David I’s accession to the throne and features panels in both Scots and English. It explores David’s role in developing Scots as a language of the royal court.

The exhibition is at Stirling Castle until 28 September then heads to Edinburgh’s Central Library until 2 December. It is then at Dunfermline Abbey from 7 December until 8 February 2025.

Linlithgow Palace’s new audio guide lets you listen to tales of the property in modern Scots as well as English, while other sites now have new signage featuring Scots words.

To immerse yourself in the language, take part in #Scotstober, created by the Scots Language Centre. The online event invites you to respond to a different Scots word every day in October by sharing a story, photo or poem on social media. It’s a great way to learn!

For more inspiration on ways to learn with us, visit hes.scot/learn-play

Visit our Great Big Living History Week events this October holiday

Taking place at our properties throughout Scotland – including Aberdour Castle, Fort George, Dumbarton Castle and Melrose Abbey –our Great Big Living History Week is a great way to add some fun to the October school holidays.

From 12-20 October you’ll meet characters from different periods, learn about their connections to our properties and hear about events key to each site’s history.

At Urquhart Castle say hello to Mike the medieval knight as he adjusts to military life at the stronghold held by Robert I (the Bruce). At Craigmillar Castle you’ll meet the fictional character Lady Ælfwyn, who will talk about what life was like in the 11th-century court of Queen Margaret and King Malcolm III.

Come face-to-face with various historical characters

You can also help Ælfwyn record these memories on paper while learning how to make and write with a quill pen. Whichever characters you meet during our Great Big Living History Week, snap a selfie with them to remember your great big day out. Plan your October visits at hes.scot/events

Use the discount code COLCM24 at the checkout to get an extra 10% off.

Castle of Light is back to illuminate Edinburgh skyline

Edinburgh Castle will be lit up in dazzling fashion this festive season as Castle of Light returns to the iconic landmark for the fifth time.

On selected dates from 22 November to 4 January 2025, between 4.30pm and 9pm (last entry between 7.30pm7.45pm), visitors will be treated to a spectacular after-dark light and projection show.

See Edinburgh’s stories brought to life on the castle walls, meet Rex the loveable lion in the Great Hall, and grab a drink or snack from

our café or street food vendors. With an all-new show for 2024, get ready to ‘fire’ Mons Meg, walk in iconic footsteps, and make Castle of Light part of your festive plans! Historic Scotland members get an exclusive 10% discount on all ticket types.

Access Night is on 8 December, offering a quieter experience with fewer visitors and accessible tours to make the event enjoyable for all. More details will follow on our website.

To book, visit castleoflight.scot

with Ranger Gordon Smith

Rapidly growing gorse can be a problem for the Ranger Team, explains Gordon Smith

Autumn is a busy time in Holyrood Park. As swallows depart and summer ends, the Ranger Team dust off their tools and get to work. Our summer surveys are replaced by practical conservation, with our attention turned to managing gorse.

Gorse is a spiky evergreen shrub that covers large swathes of Holyrood Park. It’s so widespread that an area of the park is known as Whinny Hill – whin is a traditional name for gorse.

In the spring, gorse provides a safe nesting habitat for many different birds. Its early flowering is a welcome food source for bumblebees and other insects.

Although it peaks in April and May, gorse has a long flowering season. Remarkably, those famously bright yellow gorse flowers can often be found on the shrub throughout the year – hence the saying, “when gorse is out of bloom, kissing is out of season”.

Without intervention, this spiny shrub can dominate at the expense of other species.

Holyrood Park’s volcanic terrain is the perfect habitat for threatened mosses, such as Grimmiaanodon– in fact, it’s the only place it occurs in the UK. Unfortunately, gorse encroachment is a significant threat to this and other uncommon mosses. And so, armed with loppers and bow saws, Rangers and dedicated volunteers head out to tackle problematic areas of gorse at our sites.

This approach is also used to conserve spring sandwort, a delicate white flower that grows in rather inaccessible slopes and

Despite its many benefits, gorse poses certain challenges for the Ranger Team. It spreads rapidly, assisted by its exploding seed pods and impressive ability to colonise poor soils and rocky habitats.

gullies in Holyrood Park. Despite these challenging locations, Rangers and volunteers tackle the invading gorse to give this rare flower a chance.

Of course, it’s not only our keen volunteers who play their part in pruning this plant at our properties.

Throughout autumn we work with local schools and community groups who are keen to lend a hand and gain valuable practical experience. These brilliant groups help us create and maintain essential firebreaks in the dense gorse.

Unfortunately, Holyrood Park has experienced several wildfires, so creating firebreaks is vital. Ultimately, this collective approach helps keep Holyrood Park, its wildlife and visitors safe.

SUPER SNACKERS

Atrioofgorse-loving birdstospotatour propertiesthisseason

STONECHAT

Holyrood Park

Asthenamesuggests, thisrobin-sizedbirdis knownforitssharp, loudcallthatsounds liketwostonesbeing tappedtogether.

YELLOWHAMMER

Blackness Castle

Spotthisfarmlandbird –withitsstrikingly yellowheadand underparts,brownand blackstreakedback andchestnutrump–perchedatopbushes.

LONG-TAILED TIT

Stanley Mills

Equippedwithatail longerthanitsbody, thisblush,blackand white-plumedtit fliesinexcitableflocks ofabout20birds.

The dining room of Glamis Castle serves as a hospital ward during the First World War

November event explores the impact of two world wars on Scottish estates

Join us at John Sinclair House in Edinburgh this Remembrance Day to discover how Scotland’s country estate houses were used during the First World War and Second World War. Among the archivists sharing unique wartime stories will be Glamis Castle’s Ingrid Thomson, Mount Stuart’s Lynsey Nairn and Blair Castle’s Keren Guthrie, along with Inveraray Castle’s Head

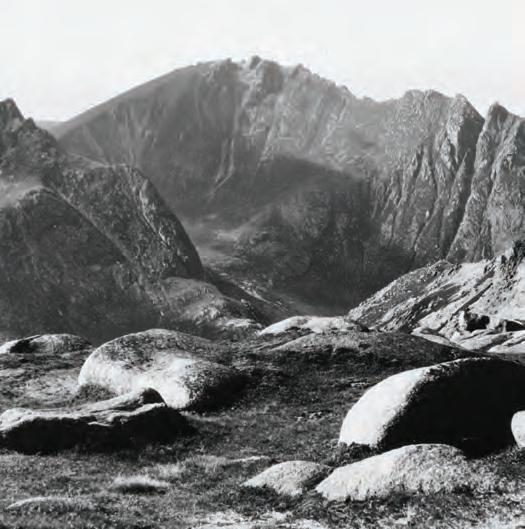

See Scotland from the sky

With an introduction by writer and broadcaster James Crawford, our new Above Scotland pocketbook provides views usually reserved for birdlife, including sumptuous aerial images of cathedrals, castles and lush countryside. It is available for £9.99 from our online shop, where Historic Scotland members enjoy a 20% discount. Get your copy at stor.scot. Turn to page 48 for member discount details

Guide Kenneth Whyte. You will hear how these and other residences were repurposed as auxiliary hospitals and convalescent homes for service men and women, and supported Loch Fyne’s Combined Operation Training Centre to bolster wartime efforts.

To reserve your free in-person or online space at 2pm on 11 November, email archives@hes.scot

Recuperating soldiers take part in a drama production at Glamis Castle

To celebrate the arrival of our secondever pocketbook, we’re giving away three copies of Above Scotland. Packed full of contemporary and archival aerial photography, you’ll be treated to a bird’s eye view of Scotland’s diverse and dramatic landscape. Correctly answer the following question to be in with a chance of winning.

ANSWER THIS QUESTION

How many images does our National Collection of Aerial Photography hold?

A. 300,000

B. 3 million

C. 30 million

UP FOR GRABS

Three copies of Above Scotland (RRP £9.99).

HOW TO ENTER

Submit your answer online at hes.scot/ member-comp by Thursday 3 October 2024. Terms and conditions can be found here too. This competition is open to UK residents only.

Last issue’s answer: Robert I (the Bruce) was born on 11 July 1274.

Lynsey Haworth, Collections Access Manager, on this recent donation now on show at Trinity House

Built on the River Clyde in 1835, the Pegasus paddle steamer operated between Leith and Hull. Just after midnight on 20 July 1843, the Pegasushit a rock off the Farne Islands and couldn’t be saved. Of the suspected 15 crew and 41 passengers on board, only six survived.

Recovered unclaimed items, including this Bible, were brought to Leith. The inside cover features a handwritten inscription stating it was recovered by divers from the shipwrecked steamer. It was bought by the donor’s grandmother at a charity shop sometime between 1945 and 1960.

Learn more about Scotland’s maritime heritage at hes.scot/trinity-house

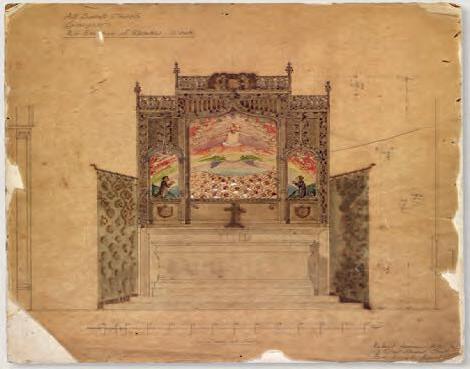

Phoebe Anna Traquair was renowned for her role in Scotland’s Arts and Crafts movement. When we acquired her design for the reredos – an ornamental screen or wall behind an altar –in Glasgow’s All Saints Episcopal Church, we

The National Collection of Aerial Photography website has been revamped

Elizabeth Hepher, Paper Conservator, on conserving a Phoebe Anna Traquair artwork

worked to conserve the precious artwork.

This 1920s design uses pencil, iron gall ink and watercolour on brown transparent paper, and is a rare example of Traquair’s collaboration with architect Sir Robert Lorimer.

Left: thin Japanese paper being used to repair a tear in the drawing Right: toned Japanese paper selected for repair of the lost areas

My assessment revealed the artwork to be very fragile. I repaired tears using thin Japanese paper and wheat starch paste adhesive, while filling losses with toned Japanese kozo paper. With the drawing conserved, we can paint a more detailed picture of Traquair’s impact. Find out about the women who shaped Scotland’s culture in our Makers and Creators online exhibition at hes.scot/women-makers

We’ve recently launched a new and innovative website for the National Collection of Aerial Photography (NCAP). Home to 30 million images of locations worldwide, some featuring in the recent Apple TV series Masters of the Air, NCAP is used internationally for many purposes, from planning disputes to explosive ordnance disposal.

Our new Air Photo Finder provides immediate access to high-quality geo-located images to find, view and buy. Visit ncap.org

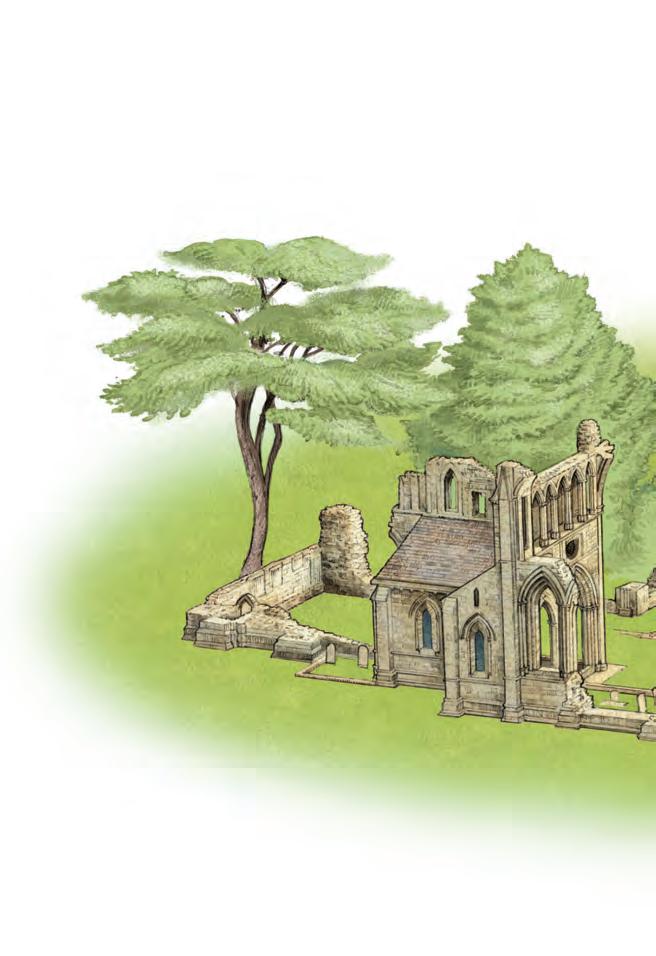

For a sense of the contemplative life of a medieval monk it’s worth a visit to these graceful ruins in the Borders

Situated on a bend in the River Tweed, Dryburgh Abbey was founded by Hugh de Morville, Lord of Lauderdale, as an act of noble piety typical of his time. The tranquil spot became home to a community of white-clad Premonstratensian canons, the first of six monasteries established by the order in Scotland. TheChronicleof Melroserecords their arrival on St Martin’s Day in 1150.

One of the most picturesque of the Scottish Border Abbeys, Dryburgh has links with several famous characters, not least as the burial place of author Sir Walter Scott. It is also the site of the venerable 900-year-old Dryburgh yew tree, which pre-dates the abbey itself.

Dryburgh Abbey’s location near the border with England resulted in several devastating

The Dryburgh yew tree begins its 900-year-old existence on what will become the site of Dryburgh Abbey.

attacks by English armies, beginning in 1322 when retreating English forces set fire to it. Most of what survives dates either to the early 1200s or to rebuilding following an attack by Richard II of England’s forces in 1385.

A sustained attack in 1544 was the final blow, however, from which the abbey never recovered. In 1786, David Steuart Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan, acquired the ivy-clad ruins of the site once owned by his ancestors. Over 40 years, he created a landscape in which the romantic ruins figured prominently, planting ornamental shrubs and a variety of parkland trees, which are still here.

1 PRESBYTERY

The church’s most sacred area at its east end housed the high altar. It would have been highly decorated, though little evidence survives.

2 NORTH TRANSEPT

The best-preserved part of the church is now the setting for the graves of Walter Scott and Field Marshal Earl Haig.

Nowadays, the abbey and its environs are important for wildlife, including three species of bat: the brown long-eared, Daubenton’s and the pipistrelle.

The abbey is founded by Hugh de Morville, Constable of Scotland and Lord of Lauderdale, as a symbol of noble patronage of church reform.

The Chronicle of Melrose records the arrival of the Premonstratensian order of canons on St Martin’s Day.

During the Wars of Independence with England, a retreating English force head for the abbey, perhaps to obtain provisions, but end up setting fire to it.

3 SOUTH TRANSEPT

The extant grand south gable of a structure that would have mirrored the north transept.

4 WARMING HOUSE

A heated chamber where canons could briefly warm themselves by a fire.

5 NOVICES’ DAY ROOM

Newly recruited canons would have undergone their training in this large space.

6 SOUTH RANGE

The remains of the refectory, or dining room, on the upper floor, with vaulted chambers below, which still stand.

7 PARLOUR

A small room once used by the canons now houses a display of finely carved masonry from the abbey.

1326

King Robert I (the Bruce) grants financial support and rebuilding of the abbey begins almost immediately. Reconstruction is on a grand scale.

8 CHAPTER HOUSE

The most important room of the cloister, the community met here each day for readings, news and also to confess any misdemeanours.

1385

During Richard II’s invasion of Scotland, the abbey is ‘devastated by hostile fire’, and Robert III and others provide funds for its rebuilding – including the west end of the church and west door.

9 NAVE

Lay people would attend services here, although little now survives apart from the pillar bases.

10 WEST DOOR

Rebuilt following the 1385 attack, this entrance way would have originally formed part of a grand façade.

11 GATEHOUSE

Added in the 1500s to provide a point of arrival to the commendator’s house.

1786

David Steuart Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan, acquires the abbey and creates an extensive designed landscape around the ruins, which includes ‘The Temple of Caledonian Fame’.

Viewed from above, it’s easy to see why Blackness Castle was affectionately termed ‘the ship that never sailed’. Pointing out towards the water, it resembles a vessel stranded on a rocky shore (indeed its three towers are called ‘stem’, ‘main mast’ and ‘stern’). Strategically positioned, it affords a commanding view over the Firth of Forth in both directions.

Originally built for the Crichtons, one of Scotland’s

most powerful families, this 15th-century castle has undergone many changes as a result of both war and restoration. The central tower within the courtyard dates from the 1400s, but Blackness changed from family home to garrison fortress and state prison when James II took it into crown ownership.

In the 1530s and 1540s, Blackness was strengthened. A defensive spur was added to the west of the castle and its walls

were almost quadrupled in thickness and increased in height. A century later, this refortification did not save the castle from Oliver Cromwell’s military onslaught of 1651.

The ancillary buildings just outside the curtain wall were part of a redevelopment in the 1870s when the castle became an ammunitions depot, as was the iron pier we see jutting out into the water. This is thought to have replaced a wooden jetty previously

used to welcome and launch boats. Major revisions carried out after the First World War saw the site reversed to its medieval status, including demolishing buildings and ripping up concrete floors.

While its appearance in the first series of Outlander brought international fame to Blackness Castle, the large mud flats surrounding it have been designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest for their habitat and wildlife value.

Standing in front of a castle or fort, we can appreciate the architecture, engineering and hard graft that went into its construction. Perhaps less obvious is why our predecessors chose that shape, and how the structure has evolved. Here, we look at seven historic sites with fascinating footprints and find out how aerial images can record and protect our past.

Stirling

Situated to the west of Stirling Castle, this geometrical earthwork was designed to be enjoyed from the rooms above it (and the ‘Ladies’ Lookout’ in particular), so it’s no surprise that it looks striking in aerial photographs.

This three-tiered octagonal stepped mound, which rises to three metres, lies next to a rectangular flat area. They are all that remain of the former royal gardens surrounding the castle, which brought fragrance and colour to its residents, with box hedges and raised flower beds.

The King’s Knot was remodelled in 1633 when King Charles I stayed

Another perspective on

at Stirling Castle. By 1842, it had fallen into disarray and Queen Victoria ordered a restoration.

Recent aerial photographs have revealed three concentric ditches beneath the King’s Knot. They could indicate an earlier medieval structure, the presence of a former Roman fort, or perhaps a much older prehistoric structure.

Dumfries and Galloway Caerlaverock Castle’s distinctive triangular shape (unique in Britain) looks even more magnificent from above. It’s unclear if the shape was chosen intentionally c.1277, or was informed by the bedrock beneath, but it certainly made attack harder.

The castle’s coastal position in Dumfries and Galloway allowed its residents to command the east-west route across the River Nith, which flows into the Solway Firth, potentially taxing travellers. Being sited near the border with England, the fortress would in theory be ready to rebuff English invasions, though these tended to occur on more eastern routes into Scotland.

A twin-towered gatehouse protected the northern approach, initially with arrow slits then upgraded in the 16th century to gun holes. The wide moat is quite a rare feature among Scottish castles, which often have dry ditches. Uneven grass out front conceals the remains of siege works and outer defences.

Despite this, Caerlaverock’s defences were no match for the Covenanters of 1640. The south wall and south-east tower were destroyed by artillery during the three-month siege, then further dismantled by the besiegers to avoid any future attempts at defence.

Q&A with Dave Cowley, Deputy Head of Heritage Research Service (Archaeological Survey)

How do aerial images help us to understand and care for our past?

Scotland’s landscapes are covered with the remains of archaeological sites, which are vulnerable to being destroyed if they are not on record to be considered during planning. It’s vital for us to survey them so the knowledge they give us about the past isn’t lost. The landscape is like a book; it can be read and understood. But it’s a book with lots of missing pages, so our team collects those pages for us to understand our past now, but also for people in the future.

Why is this bird’s eye view so effective at capturing our shifting landscapes?

The airborne perspective is very good at recording change. Compare an aerial photograph of Glasgow taken by the RAF in 1947 with today and it tells us an enormous amount about how our urban areas have transformed. It’s the same with rural and coastal areas.

If you’re trying to explain the impact of climate change on our coastlines, aerial imagery showing the ripping away of dunes over 50 years is incredibly powerful, and can help us think about what might happen in the future.

What kind of activity are you capturing from above?

In one image, we might see entrenchments that Roman legionaries built 2,000 years ago and we’ll also see the spaghetti lines of tracks left during Second World War tank training. They connect us to real people who have lived and died in these landscapes, and that’s what excites me about Scotland’s landscape – it’s got stories to tell.

The monuments you record are often buried. How can you spot them from above?

1 The different responses in an arable crop to the buried concentric ditches of this Iron Age fort are clearly visible in this aerial photograph

It depends where we’re looking. If it’s a lowland area, we rely on ‘crop marking’. A buried ditch which was dug around a settlement 2,000 years ago holds more moisture and the crops above it grow differently, they ripen more slowly, the leaves are bigger, and you can see all that on aerial photographs.

You use airborne laser scanning – why is it so powerful?

The laser scanner is mounted on an aircraft or UAV (unmanned aerial

2 This visualisation of laser scanning data of Burnswark in Dumfriesshire shows the outline of the Roman camp and Iron Age settlements

vehicle) and sends out thousands of pulses per second. As each pulse hits something, it bounces back to the sensor, and the time this takes is used to record the position of that feature.

It’s an amazing technique for looking at landscapes. In aerial photographs, the shadows and highlights that show things up are fixed by the sun. With models of the ground surface generated from airborne laser scanning, you can control the lighting and that allows us to look at sites and landscapes differently.

3 The scooped yard and roundhouse platforms of an Iron Age settlement are a new discovery from airborne laser scanning

That’s what excites me about Scotland’s landscape – it’s got stories to tell

When arrows were the weapon of choice, stone towers offered the ideal defence, allowing you to fire at the enemy yet avoid being a target. The arrival of guns and cannons posed a whole new threat for castles and forts, and different types of defence began to emerge.

Fort George was built with this in mind, using star-shaped ramparts to offer clear lines of sight, and earthen ditches and embankments to absorb the shock of low artillery fire. Looking down, angled bastions project out from the ramparts at the same height, leaving them far less vulnerable than tall towers.

Inspired by the European style of ‘trace Italienne’, the fort was commissioned by King George II’s government in a bid to control the Highlands after the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

With its geometric shape, defenders could cover all angles of possible attack.

Its designer, LieutenantGeneral William Skinner, carefully positioned Fort George on a peninsula jutting into the Moray Firth. The Jacobite army had scant naval support so the sea offered protection on three sides and, if the fort was besieged, supplies could arrive by sea. On the fourth side, which could be approached by land, Skinner built outworks.

It took 21 years and more than 1,000 workers to construct Fort George, by which time the Jacobite threat had dissipated and the fort became an army training base. The only major alteration since then came in 1859. Napoleon III’s threat of invasion resulted in a big upgrade of Britain’s coastal defences and most of the seaward-facing ramparts were replaced by indented turf parapets.

This remarkable site tells us so much about the changing nature of human dwellings over 4,000 years.

Jarlshof, meaning ‘Earl’s House’, was so-called by Walter Scott during a visit there in 1814. Little did he know that the house was just one of the treasures buried beneath wind-blown sand and turf. Excavations in the 1930s and 1950s revealed what we see today.

From above we can easily spot the curved buildings of Bronze Age and Iron Age dwellers;

the rectangular architecture favoured by Norse/viking families; and the square structures, much like our own, that here date back to the 16th and early 17th centuries.

Whether each occupant was aware of those who came before them is unknown, or how much has been washed away by coastal erosion, the harsh cut of nature so visible in an aerial photograph. But this favoured spot near the southernmost tip of Shetland’s mainland clearly had much to offer them all.

Angus

It’s no accident that Ardestie Earth House near Monifieth is located in the middle of arable farmland. Most likely built in the first two centuries AD, this ancient souterrain – an underground structure –was probably used to store food, such as eggs, meat and dairy, that would be consumed at a nearby settlement.

Discovered by accident in 1949, while the field above it was being ploughed, the Earth House was part of a complex of buildings. Its crescent shape is typical of Iron Age souterrains in this region (we assume

Orkney

The almost perfect circular shape of the Ring of Brodgar can be best appreciated from above, as can the even placement of each stone (with the exception of the ones adjacent to the causeway which, for some reason, are slightly closer together).

to wrap around or fit inside their circular houses), and the long trench lining is made up of small boulders and split flagstones. Recent theories suggest Ardestie Earth

Situated in Mainland, Orkney, between the Loch of Stenness and the Loch of Harray, the Ring of Brodgar is the largest stone circle in Scotland. Of the original 60 stones carved and carried by our Neolithic ancestors, 36 remain and 21 are still erect, some having been repositioned in the early 1900s.

What the circle was designed for is pure conjecture but its alignment with the sun, moon and stars suggests ceremonial use, in particular during the midsummer and midwinter solstices.

House was built during the Roman occupation of central and eastern Scotland to help meet the increased demand for agricultural produce. GET ALL THE DETAILS

Discover the people and places of the Icelandic sagas, a fascinating and evocative form of literature that continues to illuminate a culture whose influence is still felt across Scotland today

WORDS: TOM FAIRFAX

The word ‘saga’ gets used a great deal these days. Film series such as Marvel Studios’ The Infinity Saga and the Star Wars Skywalker Saga have made the word a mainstay of how we talk about stories in the modern era.

In medieval times the word had a similar meaning. In Old Norse, ‘saga’ meant ‘story’, and Icelandic saga compilers collected these stories to make long narratives that we now call the sagas. As with the modern series mentioned above, these stories were often linked in some way: one saga might happen in the same place as another, or feature the same people.

Many were about Icelanders living around the year 1000, such as Egils saga, while others were the biographies of Norwegian kings that continued into the 12th and 13th centuries, such as Sverris saga. They vary greatly in content, with some sagas being

The famous Lewis chessmen date to the time of saga star Harald Maddadarson

translations of other texts, such as Trójumanna saga, or ‘the saga of the men of Troy’, an Old Norse translation of Greek myths. By the 1200s, a thriving literary culture across the Nordic world produced huge numbers of these stories, some of which survive in medieval and early modern manuscripts.

Parts of Scotland belonged to this Nordic literary network too. The kingdom of Mann and the Isles features significantly in Hákonar saga, with King Hákon of Norway touring the Hebrides before the Battle of Largs in 1263. King Hákon died of an illness in Orkney in December of that year, at the Bishop’s Palace in Kirkwall.

The most important saga, as far as Scotland is concerned, is Orkneyinga saga. This text recalls the history of the earldom of Orkney from around 800 through to around 1200. Its author, or

By the 1200s, a thriving literary culture across the Nordic world produced huge numbers of these stories

Norse sagas suggest the Earl’s Bu in Orphir was the Queen Vic of its day

authors, are unknown, with the saga likely being the product of a collection of separate traditions. For example, its source for the life of Earl Thorfinn, based at the Brough of Birsay, was poetry written in the 11th century. As with many sagas, it is thought to have been compiled sometime around 1200 in Iceland, so its recollections of the early Viking Age are not exactly historical. In some cases, saga compilers were reliant on stories and folk tales passed down through generations for events that happened 400 years previously.

Orkneyinga saga can tell us a lot about parts of Scotland in the 12th century. In this period, Orkney was not a base for remote raiders but an integrated part of a Norse-Scottish

Duffus Castle, near Elgin, likely features in the Orkneyinga saga

Objects found in Scotland often point to Nordic connections

Artefacts now in the care of National Museums Scotland display Nordic design and craftwork, such as this brass brooch dated to AD 875-925, discovered on Islay.

borderland. Places that we would not think of as having a Norse past feature in the saga. It discusses the travels of Sveinn Ásleifarson, who had estates in Orkney and Caithness during the 1100s. He sailed around Scotland, mixing with the Scottish kings and their allies in places such as Edinburgh. The saga suggests Norse-speaking traders travelled to ‘Dufeyrar’, also visited by Sveinn and which can probably be identified as Duffus Castle, near Elgin. Norse-Scottish society was quite different to the one we associate with vikings. Evidence of this can be seen at the Earl’s Bu in Orphir. Orkneyinga saga describes how Earl Paul Hákonarson lived at this 12th-century complex. Here, we read about a very Christian way of life alongside food production and

Two oval brooches of gilt bronze with intricate zoomorphic designs and 44 glass beads were found in a viking grave group in Uig, the Isle of Lewis, and have been dated to around AD 900-1000.

Mousa Broch in Shetland is mentioned in two different sagas –Egils saga and Orkneyinga saga

feasting, and there is mention of an important viking pastime – drinking.

“There in Orphir was a big drinkinghall, and there was a door against the eastern gable on the south side, and an expensive church stood in front of the hall doors and to go to the church, [you went] downwards from the hall. But, when going into the hall, there was, on the left-hand side, a big flat stone, and further inwards were many large ale-casks, and opposite the outer-doors was the sitting room. Then when people came from evensong, people were allocated seats.” (Orkneyinga saga, chapter 66).

In the saga, a young Sveinn Ásleifarson arrives at Orphir in the first half of the 12th century and it isn’t long before he ends up in a drunken argument with another man called Sveinn. This ends in disaster with Ásleifarson killing his counterpart and running away to seek sanctuary with the Bishop of Orkney in Egilsay. This island had witnessed murder before, as Egilsay was where Earl Hákon had his cousin Earl Magnus (later St Magnus) killed.

These stories about relationships are much more approachable than standard histories. Although their language and culture are very different from ours, the humanity of the characters comes across. They make mistakes, have a sense of humour and react with emotion.

Interpersonal dramas lie at the heart of the sagas. While some showcase grand historical narratives, there’s always room for accounts of arguments, crimes and family issues. Some of the stories that entertained medieval Icelanders aren’t that different from scenes we’d find in a TV drama today. For example, a drunken argument ending in violence is something that wouldn’t look out of place in a soap opera.

The sagas also give us access to stories of Scots who we don’t hear about in standard Scottish histories. For example, in one saga, Margaret Hákonardóttir, the mother of Earl Harald, is captured by Erlend ‘the young’ and taken to Mousa Broch. Erlend had asked to marry Margaret but Harald refused this request. We are told that Harald intends to kill Erlend – but Erlend is prepared for this eventuality.

“Erlend got a company together, took [Margaret] away, out of the Orkney Islands, and took her north to Shetland, setting himself up in Mousa Broch ... But when Earl Harald came to Shetland, he set himself up around the broch and prevented all supplies [from reaching it]. But it was not easy to come and attack that place.” (Orkneyinga saga, chapter 93).

Some of the stories that entertained medieval Icelanders aren’t that different from scenes we’d find in a TV drama today

The sagas give us a lifelike insight into 12th and 13th-century Scotland, a land very different from the one we know now

Erlend then manipulates the situation to his advantage, reaching a settlement that appears to benefit both men: Erlend will marry Margaret and, in return, support Harald in his efforts to recover the earldom of Orkney. Afterwards, we are told that Erlend joins Harald in his journey to Norway that summer.

While we get Margaret’s story here, we don’t see it from her perspective. This account could be read as Margaret running away from her overbearing son to be with a man, but it might also be a story of sexual assault, with Margaret being abducted by Erlend for a forced marriage with political benefits for him. This shows us the limits of sagas for understanding the past. While the sagas give us plenty of intriguing stories, we only have access to the voices of certain characters.

The sagas are all about perspectives and, for the early Viking Age in Scotland, these perspectives are not historically sound. However, they do give us a

An inscription in Maeshowe was written by a woman called Hlíf – the only named female runecarver in Maeshowe and one of very few outside Scandinavia. The inscription reads: ‘Jerusalem-travellers broke [into] Orkahaugr [Maeshowe]. Hlif, the earl’s food-giver, carved.’

lifelike insight into 12th and 13thcentury Scotland, a land very different from the one we know now, with places such as Caithness, the Northern Isles and the Hebrides being a Norse-Scottish frontierland.

This Scotland is not lost forever. The stories of the people who lived there have survived for more than 800 years, and so have some of the sites featured in those stories. Visit the Earl’s Bu and

Visit three of the sites where storytelling merges with real lives

Maeshowe

Experience the place where, according to Orkneyinga saga, Earl Harald Maddadarson and his entourage sheltered during a hailstorm in the 12th century. Runic inscriptions show the Old Norse names of Orcadians from the 1100s.

Follow in the footsteps of King Magnus ‘bare-legs’ of Norway, who visited the shrine of St Columba at the end of the 11th century. This event features in several sagas, including Heimskringla, Morkinskinna and Fagrskinna.

imagine the sights, sounds and smells that Sveinn experienced at Orphir. Or go to Shetland to imagine how Margaret felt when she saw Mousa Broch for the first time.

There’s no better way to experience Norse Scotland than to pick up a saga translation at a bookshop, visit a place with it in hand and read the drama to which that site was witness. Maybe, after adventuring around Norse Scotland, you’ll have your own saga to tell.

Visit the home of Kolbein Hrúga, later known as Cubbie Roo, a Norse landholder in Orkney in the 12th century. According to Hákonar saga, a group of people hid here after murdering Earl Jón of Orkney in 1231.

impression of

have seen it

Glasgow Cathedral is still a major presence in the east end of Scotland’s biggest city

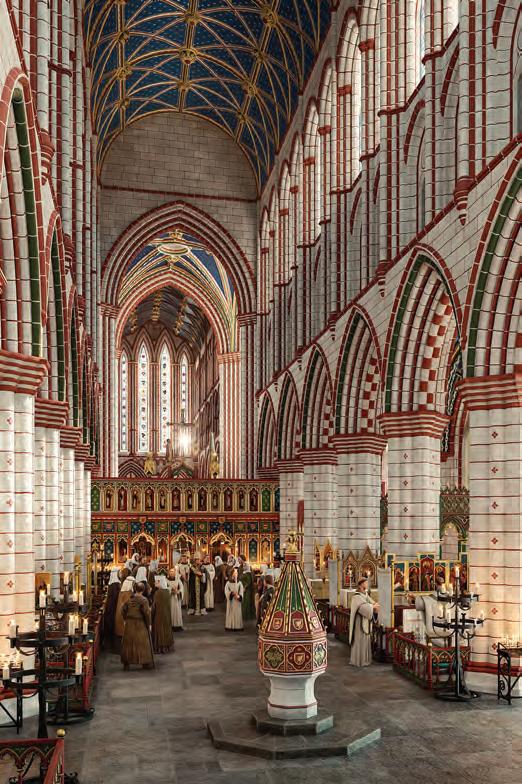

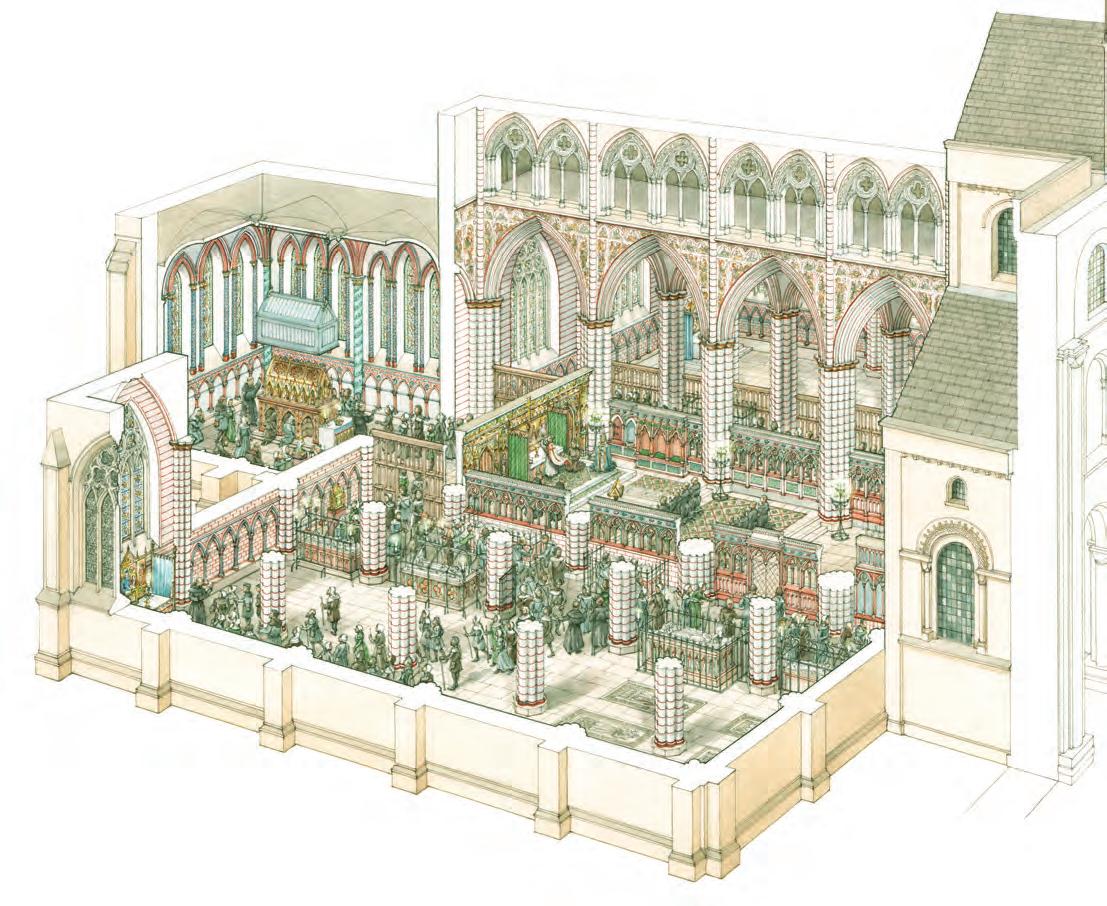

The third article in our sensory series takes us to a glittering Glasgow Cathedral in medieval times, where the faithful are flocking to a special feast day Mass

WORDS: HANNAH BROWN

Imagine travelling back in time to visit our properties in the past. How do you think they would look, sound and smell? What kind of people might you meet? In the Interpretation Team, we are always trying to explore these questions. Join me as I head back to medieval Glasgow.

As you approach the cathedral, it’s impossible not to be swept up by the sense of awe your fellow pilgrims feel as they see it for the first time. The massive stone structure towers above all other local buildings, with its spire reaching into the sky. It dominates the town that is growing in its shadow. As a pilgrim reaching the final destination

of your journey you will be exhausted, but the magnificence of the cathedral has boosted your energy reserves.

It will not be long until you reach the shrine of Saint Mungo (also known as Saint Kentigern) behind the choir and then the crypt containing the tomb that lies within.

This cathedral was built on the site where St Mungo was believed to have established a church around AD 600. Although we cannot be certain about this, it is thought that he was buried here around AD 612.

It wasn’t until many centuries later, in the 1100s, that the site of today’s cathedral was dedicated to

LET IT SHRINE

OPPOSITE PAGE

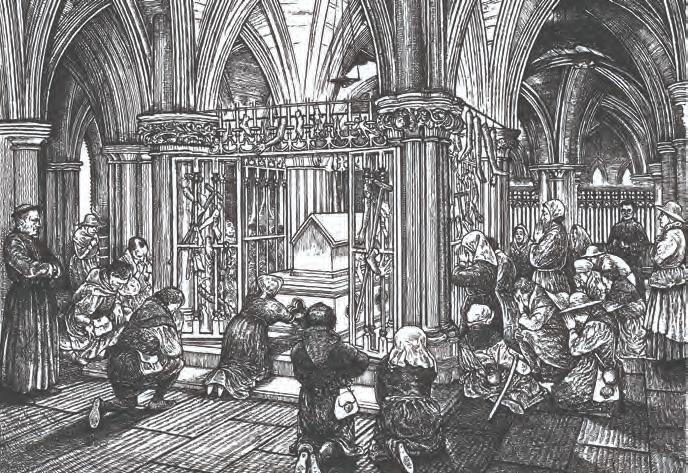

The shrine of St Mungo in Glasgow Cathedral mostly dates from the 13th century and still impresses visitors today

him. Then pilgrims began flocking here and a thriving city grew as the local traders took advantage of the resulting increased business.

Today, you are part of a throng of pilgrims who have walked many miles to honour their saint. Pilgrimage is a big part of medieval life. Most people are expected to make one at some point and for many people it is the furthest they will ever travel from home.

Medieval pilgrimage has more in common with modern tourism than you would think, allowing people a break from their usual daily routines and a chance to see new places. There are none of the luxuries of modern travel, though. Weary pilgrims travel miles on foot, with only the most basic of provisions, to pray to the saints for the avoidance of hell through salvation of the immortal soul, or to seek an intervention from the saint for a particular issue. The harder the pilgrimage, the greater the benefit to the soul. Hell is a very real concept, and the constant, supernatural intervention of God and the saints is what will spare people from the fiery pit at the end of life.

St Mungo, the ‘dear beloved’, was a missionary in Strathclyde. His sanctity was promoted by later bishops and his saintly cult was cultivated by the Scottish church. Stories about him were largely the creation of enthusiastic biographers writing hundreds of years after his death. Important saints were promoted by the church to bolster the faith of the believers. The offerings from pilgrims were a major source of funds for the church, so the cathedral developed around St Mungo’s tomb.

It is this tomb – with associated relics – that attracts the many pilgrims you are walking with today, who will follow a stage-managed route round the cathedral to get there. They will then pray for salvation, confess sins or seek cures.

The size and scale of the cathedral isn’t the only reason to feel overwhelmed as you reach your destination. Crowds mingle around the burgh, not just for the religious services but also for the markets and festivities taking place. The noise of excited pilgrims intermingles with the shouts of market sellers. You hear different accents from pilgrims who have travelled long distances. Music fills the air from the instruments that

Weary pilgrims travel miles on foot, with only the most basic of provisions, to pray to the saints

ACE OF BASE LEFT

These eight stones are thought to have formed two bays of the base of St Mungo’s tomb, and are on view at the cathedral

Pilgrims wore a heavy cloak and a wide-brimmed hat often decorated with badges acquired at shrines along the way, and carried a wooden staff and a small bag called a scrip. They travelled with very few personal possessions, relying on a network of religious houses and pious individuals for food and money.

1 PLACEOFWORSHIP

Pilgrimsarriveattheirdestination,the elaborateshrinebuiltin1250tocontain StMargaret’sremains

ST MARGARET’S FAITHFUL

Our pilgrim may have continued on to another popular place of pilgrimage: Dunfermline Abbey. This illustration shows pilgrims visiting St Margaret’s Shrine c.1350. In her lifetime, Queen Margaret helped create a support network for pilgrims in Fife, including the Queen’s Ferry across the Forth.

2 FINDINGFOCUS

Amidthenoiseandbustle,monksfrom StMargaret’sBenedictineOrdersettheir mindstothebusinessofprayer

other pilgrims have brought with them, such as bagpipes, flutes and psalteries. There are also makeshift percussive instruments, including cooking pots, adding to the racket.

On a feast day such as today you would be allowed in the great West Door along with hundreds of other worshippers and pilgrims eager to receive blessings from contact with St Mungo’s relics. Despite the crowds you cannot help but gasp at the height of the roof and the splendid decoration. The riot of rich colours and sacred imagery is like nothing you’ve ever seen before.

It’s time to start walking the wellworn, one-way route, firstly to St Mungo’s Shrine behind the choir and then down to his tomb in the crypt. You join the crush of bodies, moving through the nave towards the choir. The route is

well defined, and you don’t have much chance to wander around before you’re pushed forward by other pilgrims eager for their own salvation.

The decoration adorning the cathedral is in stark contrast to the more restrained interior that we know today. The cathedral glitters with candles, and bold colours embellish the stonework, which is painted with complex patterns. The beautifully coloured stained glass in the windows sparkles and casts multicoloured, dancing shadows on the floor. Strain your neck upwards to take in the ceiling, painted blue with silver stars.

Fragments of tile and stained glass – such as these from St Andrews and Elgin – provide clues to Glasgow Cathedral’s medieval decorative elements.

The nave is lined with altars in small private chapels enclosed by wooden screens, and the sounds of devotion and prayers from other cathedral visitors can be heard as you move past.

The cathedral was designed to control the visibility of the relics and the movement of pilgrims. So, when you

reach the choir, you strain to try and see the breaking of the bread and the canons’ other official duties which are taking place behind screens. The space is magnificent, with beautiful stone carvings that take your breath away. Look up! Don’t miss the fine foliage carvings at the tops of the columns. Make sure you also take in the four narrow windows of the east window, rising all the way to the ceiling, guiding your eyes towards Heaven.

It’s said that St Mungo’s relics are ‘incorruptible’, meaning that they avoid the usual decomposition after death

Listen out for the clergy celebrating Mass behind the screens. The prayers and psalms being recited throughout this feast day, and the mysterious Latin, build the excitement of arriving at the shrine of St Mungo, which lies just behind the closed-off space of the choir. A brusque cathedral official, employed to control the crowds, cries at you to move on and you re-join the shuffling crowd before you get into any trouble.

You’re jostled by other pilgrims all eager to get as close to the shrine containing St Mungo’s relics as possible. On a feast day like today the metal gates around the tomb are opened, allowing you direct access. These gates are cluttered with ex-votos (small paintings or sculptures usually made to commemorate a miracle) and crutches left by those who are apparently healed or seeking a cure. The scent of incense, herbs and flowers is overwhelming.

You spot the beautifully made wooden box containing the relics and bow down to them. Then it is time to make your way down the stairs, following the crowds to reach the highlight of your

journey: the tomb of St Mungo. The first thing that strikes you is that the crypt is surprisingly bright, with not only candlelight but natural light from the windows. The experience is precisely stagemanaged and you can see the tomb glowing with carefully directed lighting.

You need a moment to take in the incredible vaulted ceiling, a feat of the medieval mason’s craft. It’s been designed to give the tomb an intimate atmosphere. You take in the smell of the incense, and the honeyed fragrance of the saint’s remains. It’s said that St Mungo’s relics are ‘incorruptible’ (meaning that they avoid the usual decomposition after death) and exude a floral or sweet aroma. The sweetness masks the less than pleasant smell of your fellow pilgrims’ bodies after their long journeys on foot. You could reach out and touch the stone, painted in bright colours and patterns and smooth against your hands from the work of the master masons who built it.

Chapel, which is dedicated to the Virgin Mary. There are more devotions at various other chapels before you have to leave the crypt behind and start ascending to the doors at the north end of the cathedral. Time to take a deep breath. The crush of bodies was starting to get claustrophobic and you’re glad to leave with one last look over your shoulder at the glittering interior.

You have just enough time to perform your devotions at the tomb before being carried with the crowd towards the Lady

Your visit to the cathedral has come to a close and you head out to the precinct, enjoying the fresh air. Do you continue on your pilgrimage journey? There are more shrines to visit. Or do you wait to come back to Glasgow for the next feast day?

Once back in the present day, you notice a family entering the cathedral and following the same route you took 900 years ago. The shrine and the relics are gone but the architecture still follows the plan of the medieval cathedral. They will be able to trace your steps round the choir and down the stairs to the crypt to find St Mungo’s tomb.

Discover what vernacular buildings can teach us about Scotland’s past and how we are helping to keep traditional craft skills alive for future generations while caring for our sites today

Scotland’s architectural heritage offers a window into the history and culture that’s shaped the country we know today. Vernacular buildings are one fascinating aspect of this treasure trove, each one acting like a time capsule for the traditional craft skills and social history intrinsic to their construction.

On the following pages, Jennifer Farquharson, Lead Technical Content Officer, and Amy Styles, Technical Conservation Skills Manager, detail how we’re helping to maintain vernacular buildings for future generations.

“I’d love to thatch with marram grass and bracken in the future”

Craft Fellow in thatching and dry stone walling I started my Craft Fellowship in January 2024, but I’ve been working with Master Thatcher and dry stone dyker Brian Wilson since early 2023. Recently I’ve worked with him on the Scottish Crannog Centre’s Iron Age village.

Thatching is one of Scotland’s oldest roofing methods. It involves weaving natural materials on a roof to help move water away from a building. It’s estimated Scotland has fewer than 250 thatched buildings left.

Historically, thatching was more popular in England, resulting in designs used for vernacular buildings being quite regimented. Scotland’s designs vary countrywide.

Vernacular buildings highlight the relationship between the built and natural environment, which I find beautiful. To create the highest quality heather thatching, for example, you need to know where the best materials are located. This deepens your appreciation of nature.

Whether helping to maintain vernacular architecture like the Blackhouse, Arnol, or informing the ecoconscious design of new buildings, thatching and dry stone dyking are incredibly environmentally friendly practices that industry should use more.

I’m training in the Scottish thatching style using locally sourced sustainable materials. The heather came from the Dùn Coillich community woodland and the reed from RSPB-managed River Tay reed beds.

Vernacular buildings are also important documents of the working class who constructed them. The skills I’m honing ensure that this history isn’t lost.

Being a Craft Fellow is fascinating and I’m incredibly grateful to work alongside so many knowledgeable people.

I’ve been working at the Scottish Crannog Centre since September 2023. Initially, I focused on roundwood timber framing – which involves using green wood – to create the centre’s Iron Age vernacular buildings. I then worked with dry stone walling expert Jim

Doherty to construct a roundhouse. I built a stone base and turf wall. The challenge lay in constructing the wall in a tight space underneath the thatch roof.

I joined thatching Craft Fellow Troy Holt and Master Thatcher Brian Wilson to gather heather

for an Iron Age building’s roof. It was educational seeing Troy and Brian’s meticulous thatching in action. I worked to a looser style of Iron Age vernacular reed thatching. Learning vernacular craft skills has been fascinating. They’re imbued with tradition and history, and they connect you to people who are knowledgeable about their cultural significance. Craft Fellowships are vital to ensuring traditional craft skills aren’t lost, and

they can teach us to maintain heritage and contemporary architecture more sustainably.

I’m looking forward to trying clay plastering, lime harling and slate roofing soon. Exploring so many vernacular crafts is one of my favourite aspects of the fellowship.

The team of dedicated and skilled workers at the Scottish

Finding easily accessible material was often a deciding factor on where and what to build

“Vernacular architecture is the link between a building, local materials and the people who created it,” says Jennifer Farquharson. “Whether used for domestic or agricultural reasons, many vernacular buildings played important roles in communities.”

These buildings come in many shapes and sizes. Encompassing farmsteads, smithies and tower houses, they have characteristics such as thatched roofs, dry stone walls and lime mortars.

In contemporary construction, materials from around the world can be delivered to a site. Although convenient, this approach can involve unsustainable practices that contribute to the climate crisis and building industry waste.

In contrast to Polite architecture –buildings with non-local styles for decorative effect – vernacular buildings were constructed using approaches rooted in place and purpose. Their designs were influenced by materials available locally and adapted to endure Scotland’s highly changeable climate.

“Historically, transporting goods was a difficult task. Finding easily accessible material was often a deciding factor on where and what to build. Whether stone, turf, thatching material or timber, having a nearby building supply was essential to creating these buildings,” explains Jennifer.

“Communities once had a deeper understanding of their environments. Those who built these vernacular structures often also lived in them and spent time growing and sourcing materials to care for them.”

This intimate knowledge of the natural environment shaped the vernacular heritage of communities throughout Scotland. Today, we help to care for a variety of these buildings.

The Isle of Lewis’s Blackhouse, Arnol, built between 1852 and 1895, was once home to a Hebridean crofting family. Now it is preserved almost exactly as the family left it in 1965.

Blackhouses have thick, dark stone walls, which gifted them their monikers. Typically, these buildings were divided into two sections – one for humans and the other for livestock – to provide extra warmth against the Hebridean climate.

Pitlochry’s Sunnybrae Cottage is another excellent example of Scottish vernacular architecture. Originally, its walls were made using turf, with the roof’s weight supported on curved timber pairs called crucks. Today, its thatched roof survives under a layer of corrugated iron.

These buildings stand as testament to the craftsmanship of those who built and maintained them. As time has passed and the practice of

traditional craft skills has waned, however, many vernacular buildings have fallen into disrepair.

“Almost one in five of Scotland’s buildings are traditionally constructed, with more than half requiring repair due to climate change and age,” explains Jennifer. “The demand for the skills to maintain them has only grown.”

To address this, we have been training individuals in traditional heritage crafting skills through our Craft Fellowship and Trainee Programme for more than 35 years. Traineeships last a year, and participants work with our expert teams in technical conservation, building materials, digital documentation, tackling climate change and more. Craft Fellows are hosted by external master craftspeople throughout Scotland for 12 to 18 months, learning traditional building skills, from stone carving to blacksmithing.

“Traditionally, people would’ve been trained by family members or via word of mouth on how to look after vernacular buildings. But with these skills becoming less commonplace and many traditional craftspeople nearing retirement, they need to be passed on,” says Amy Styles.

“We’re making this happen by linking Craft Fellows to experts that can train them in traditional crafts through their experience, knowledge and skills.”

Almost one in five of Scotland’s buildings are traditionally constructed, with more than half requiring repair due to climate change and age. The demand for the skills to maintain them has only grown

Before starting my Craft Fellowship in September 2023, I worked in the construction industry as a labourer and roughcast plasterer. I applied for a Craft Fellowship because I’m interested in maintaining heritage skills for future generations. The skills I’d gained so far were a natural fit.

I’ve been working with Edinburgh-based stonemasons and plasterers LimeRich. They use traditional techniques and cutting-

edge machinery to apply lime-based render and plaster on historical and residential buildings harmed by improper maintenance or age.

Travelling to Scotland’s historic sites and meeting individuals who know the stories behind these buildings has been amazing.

their environments. They also have very low carbon footprints as they use local and easily accessible materials.

Unique to each pocket of Scotland, vernacular buildings reflect the people who once lived in them and

Adopting the ecoconscious approach to vernacular craft skills encourages a way of thinking about construction that’s more sympathetic to the environment.

It’s vital that traditional craft skills aren’t lost as we find new ways to better care for Scotland’s historic buildings.

Craft Fellows have been involved in many fascinating projects. Recently, several of them have been learning thatching, dry stone walling and working with turf and round timber to recreate the Scottish Crannog Centre’s Iron Age village in Perthshire.

Crannogs were artificial islands with timber-built dwellings that were constructed in lochs and rivers, and they appear to be unique to Scotland and Ireland. On your next trip to Linlithgow Palace, visit Linlithgow Loch to see Cormorant Island and the Rickle – now treecovered, these are thought to be the remains of crannogs built 2,500 years ago, which were used as dwellings until the early 18th century.

Practical skills aren’t the only talents that Craft Fellows develop. “They learn about business skills, project management, applying for jobs and networking with other craftspeople,” explains Amy. “The ultimate goal of the Craft Fellowship and Trainee Programme is to keep traditional building skills alive so they can help safeguard the architecture intrinsic to Scotland’s cultural and built heritage.”

The traditional skills that Craft Fellows develop can not only be used to look after vernacular buildings but also to maintain other sites we care for

The Craft Fellowship and Trainee Programme is possible thanks to Historic Scotland members.

“We wouldn’t be able to upskill Craft Fellows and Trainees to care for our built environment without our members,” says Amy. “Their support helps us invest in the skills that ensure the properties they love visiting can be enjoyed and maintained using the traditional skills learned by our Craft Fellows for a long time to come.”

While it’s vital that traditional craft skills aren’t lost to time, it is clear that there is so much more that can be learned from vernacular building methods.

“The traditional skills that Craft Fellows develop can not only be used to look after vernacular buildings but

also to maintain other sites we care for, such as Melrose Abbey and Stirling Castle,” says Jennifer.

“Aligning with our commitment to Scotland’s net zero target for 2045, the sustainable methods used to create vernacular buildings can also teach us how to reduce the embodied carbon linked to building conservation and construction.”

From enduring symbols of Gaelic culture such as the Blackhouse, Arnol, to the whitewashed walls of Sunnybrae Cottage, Scotland’s vernacular architecture provides a glimpse into the building lessons of the past. By channelling the ethos of Craft Fellows and Trainees, we can promote construction approaches that champion longterm sustainability and better utilise local resources – practices that are vital to tackling climate change today and in the future.

● Discover more about our Craft Fellowships and find resources on the materials and traditional skills used in vernacular architecture at our building conservation centre, the Engine Shed. Visit engineshed.scot

ISLAND LIFE AT LINLITHGOW

● Fancy crannog-spotting at Linlithgow Loch? Download our handy map and guide at hes.scot/linlithgow-peel-map to locate the Rickle and Cormorant islands, the remains of crannogs.

Drawn from the vibrant tapestry of Scotland’s landscapes and heritage, the colours of this tartan pay homage to the iconic bracken fern, which blankets the landscape

The tartan’s rich hues, capturing the essence of Scotland’s breathtaking scenery and historical legacy, infuse any setting with a sense of natural beauty and tranquillity.

Let these shades transport you to the rolling hills and ancient forests of Scotland.

Designed by Prickly Thistle in the Highland town of Dingwall, Bracken tartan is woven by expert weavers Lochcarron of Scotland.

Our Bracken collection has been designed and made exclusively for Historic Scotland using 100% Scottish wool.

The 750th anniversary of the birth of Robert I (the Bruce) this July has been commemorated with two new collections, which are available at Dunfermline Abbey and Palace. Both collections are designed by Scottish artist Allistair J. Burt, and each symbolises a moment in Scottish history.

In the north transept of Dunfermline Abbey, you’ll find the King Robert the Bruce Memorial Window. Its upper lights depict Christ in the centre, with the saints Ninian and Andrew on his right and Columba and Fillan on his left – each of whom have a special place in Scotland’s history – while Bruce features directly below.

Taking inspiration from the shapes and blue hues of the window, this small collection consists of a mug, greeting cards, journal, cosmetic bag, lavender heart, bookmark and glasses case.

Robert the Bruce Collection

If you’re looking for something a little quirkier, the Robert the Bruce Collection is just that. It features a larger range of items, including a tote bag, pin badge set, keyring, mugs and greeting cards.

1 Mug £13

2 Keyring £12

3 Greeting cards £3.25 each Tote bag £12

Pin badge set £5.25

Re-enactors highlight life in a bygone age

Enjoy history brought to life at sites across the nation this autumn

VARIOUS SITES

Our living history re-enactors are back for the autumn break at sites across Scotland. Meet intriguing characters from history, from a knight at Urquhart Castle to a medieval musician at Aberdour. Our re-enactors will be on hand to tell you all about the era they are from, and to pose for photos!

l Sat 12-Sun 20 Oct, during site opening hours.

VARIOUS SITES

This fun trail for children of all ages is back by popular demand for another year. Find the different plants scattered across the various properties to free them from enchantments.

l Tues 1 Oct-Sun 3 Nov.

STIRLING CASTLE, CRAIGMILLAR CASTLE, URQUHART CASTLE

Join us at one of three castles taking part in some

Halloween fun. Urquhart Castle and Stirling Castle have all manner of creepy delights planned, while Ravina the Storyteller and the Master of Owls are ready to welcome you at Craigmillar Castle for riddles, songs and perhaps some magic.

l Stirling Castle Sat 26 and Sun 27 Oct, 11am-3pm.

l Urquhart Castle Fri 25 and Sat 26 Oct, 10am-4pm.

l Craigmillar Castle Sat 26 and Sun 27 Oct, 11am-3pm.

TRINITY HOUSE

Our resident storyteller shares tales of mysterious ships, superstitions and strange vanishings. The experience includes a twilight tour of Trinity House, and the lantern-lit 16th-century vaults. Earlier tours are suitable for children and later ones for ages 12+ only. Members get a 10% discount.

l Thurs 24 and Fri 25 Oct, 4pm-5.30pm, 7pm-8.30pm.

EDINBURGH CASTLE

Now in its fifth year, one of Scotland’s largest projection shows returns to Edinburgh Castle for the festive season. Discover the iconic site after dark and enjoy unmissable immersive displays and interactive installations. There will also be delicious food and drink to enjoy, either from vendors on the esplanade or from the café. The event’s Access Night will take place on Sun 8 Dec to make sure everyone can enjoy it.

l Various dates from Fri 22 Nov to Sat 4 Jan, 4.30pm-9pm (last entry 7.30pm-7.45pm). Access Night is on Sun 8 Dec. Tickets must be booked in advance. 10% member discount and a 10% early bird offer valid until 30 Sept (use discount code COLCM24). Book at castleoflight.scot

EDINBURGH CASTLE

Make this Christmas special with afternoon tea at the Tea Rooms and

enjoy a dining experience fit for royalty. This package includes afternoon tea for one person and entrance to the castle. Pre-booking is required.

l Dates between Mon 2 Dec-Sun 5 Jan 2025, 11am, 11.30am, 12pm, 12.30pm, 1pm, 1.30pm, 2pm, 2.30pm.

STIRLING CASTLE

Enjoy a regal dining experience in the Great Hall. This package includes an afternoon tea for one person and entrance to the castle. Prebooking required; prices available online.

l Sat 7 and Sun 8 Dec, Sat 14 and Sun 15 Dec, 1pm.

Christmas Fair

STIRLING CASTLE

A Christmas Carol STIRLING CASTLE

Chapterhouse Theatre Company brings you Charles Dickens’ timeless tale of hope and redemption as miserly Ebenezer Scrooge learns the true meaning of Christmas. With dazzling musical sequences and authentic period costuming, this production is the perfect festive treat. 10% member discount.

l Thurs 19-Sun 22 Dec, 6.15pm for a 7pm start. BSL interpretation on Sat 21 and Sun 22 shows.

Traditional Christmas at Trinity House

TRINITY HOUSE

Stock up in the splendour of the Great Hall, with stalls showcasing the best of local and Scottish brands, crafts and fine food and drink. Enjoy music from a brass band and tuck into mince pies and mulled wine.

l Tues 3 Dec, 6pm-9pm (last entry 8.15pm).

Step back in time as we celebrate a Georgian Christmas. Dive into Leith’s maritime history and explore this elegant house and its outstanding nautical treasures. Take part in festive activities for all ages, including drop-in crafts and the chance to handle real and replica objects.

l Fri 6 Dec, 12pm-4pm.

Maritime Leith’s Black History

TRINITY HOUSE

Tour Trinity House and discover stories that link maritime Leith with Black history around the world.

10% discount for members.

l Fri 4 Oct, Fri 11 Oct & Fri 18 Oct, 1pm-2pm, 3pm-4pm.

Make your own peg doll

EDINBURGH CASTLE

Be inspired by Mary Queen of Scots’ collection of dolls and the fashion in her times to design an outfit for your own peg doll in this drop-in workshop. Castle tickets

must be booked in advance.

l Sat 12-Tues 15 Oct, 11am-4pm.

STIRLING CASTLE

Join us for an unforgettable experience as you delve into the rich tradition of weaving in Scotland. This event offers a unique opportunity to meet a master weaver and learn about the intricate weft and fascinating history of this ancient craft. Prices available online.

l Sat 23 Nov, 10am, 11am, 1pm, 3.30pm.

Face-to-face with the past

Ranger walks

VARIOUS PROPERTIES

Doors Open Day – 900th Burgh Celebration

THE ENGINE SHED