historic NEw england

The Little Miscellany at Cogswell’s Grant

Meet the new President and CEO, Vin Cipolla

Talking about slavery at Sayward-Wheeler House

Meet the new President and CEO, Vin Cipolla

Talking about slavery at Sayward-Wheeler House

These are exceptional times, globally, nationally, locally, and at the most personal levels. As we look ahead post-pandemic, we appreciate the support of those around us. At Historic New England, we are grateful for the long-standing leadership that so successfully navigated us through these last few months, and for the new leadership that will guide us into an exciting future.

We thank Carl R. Nold, who retired at the end of May after seventeen years as president and CEO. There was no time to wind down as he skillfully guided Historic New England during this extraordinarily difficult period. In his last months on the job, Carl played a tremendous role captaining Historic New England through

On June 1, Carl handed the reins to Vin Cipolla. We are delighted to welcome Vin as our new president and CEO. Vin’s appointment comes after a national search that attracted more than three hundred candidates who were eager to become a part

Vin has great passion for the work of Historic New England, with leadership experience in the arts, historic preservation, and environmental advocacy. He has served as chairman, president, and CEO at for-profit and nonprofit organizations in New York, Washington, D.C., Boston, and London. Born and brought up in Massachusetts, Vin is excited to lead an organization that he has greatly respected throughout his career. You’ll learn more about Vin in the first article of this issue.

Other articles in this issue show how we continue to use the expertise we have built over more than a century to address issues and topics of today. At Sayward-Wheeler House in York Harbor, Maine, we are discovering the previously untold stories of the enslaved. At Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, we explore LGBTQ history. Work by interns from Middlebury College in Vermont provides new information on the impact of climate change at several of our historic sites. We offer tips for becoming a citizen preservationist in your community, and give much-deserved visibility to modern architect

As always, we are most grateful for your support. As members, you are our partners in saving and sharing New England heritage

Historic New England recently appointed Vin Cipolla as president and CEO. An experienced leader in the arts, preservation, and environmental advocacy fields, he succeeds Carl R. Nold, who retired at the end of May. Below, Vin shares his thoughts on how Historic New England can best serve the public and why preservation is an essential part of the region’s future.

Historic New England strives to tell stories that are relevant to today’s audiences. What more can we do to save and share the history of all New Englanders?

Every story matters. And each story is interconnected with others. Within a community of even twenty individuals, there’s a multitude of stories, shared experiences, differences, influences, and endless possibilities for ideas, perspectives, and insights. Finding the common threads—the interconnectedness— as Historic New England does, helps make the importance of each

individual experience and story come alive.

There is extraordinary diversity in New England, and it’s essential we have a relationship with the full experience of our past, challenge ourselves to think about the completeness of how we interpret it, and how it can fully inform our way to a more just and equitable future. The range of media available today allows us to do this in many exciting ways, and we, like other organizations, will have to push ourselves to engage with audiences in new forms.

Why are outdoor experiences useful in helping people connect to their communities and to one another?

As a devoted and passionate hiker and walker, I’ve experienced in endless ways the deep and meaningful perspectives gained by physically experiencing a place at a slower pace and at eye level. It’s the only way to absorb the context of an environment, to get a sense of both its complexity and essence. To stop and start, to stare and wonder, to engage with sights and smells. To tune to its

rhythm—whether that tone is set by nature or spontaneous human interactions. Walking or hiking with others—one-on-one or in small groups—is the best way to share and grow ideas, open up thinking, and build lifelong bonds. Whether it’s a long hike along a wooded trail, walking a manicured landscape, traversing the streets of a dense urban neighborhood, or wandering by foot through small cities and towns, there’s no substitute for the benefits you receive from the slow, rich textures of these experiences. And conditions don’t have to be ideal, and it’s sometimes better if they are not! I once led a group of about fifteen through daylong torrential rain in Great Smoky National Park, when I was heading the National Park Foundation. We made it work. There were many laughs. And we had the best group conversation ever during our evening dinner about the park and why it matters so greatly to its local communities and should matter more to the broader public.

How can historic preservation offer solutions for some of today's challenges, including housing and the environment?

Both the philosophy and the principles of historic preservation provide a compelling road map for dealing with the critical planning issues we’re facing as a society. Reuse is the first tenet of sustainability. When a twenty-story building is demolished, it takes decades to resolve the waste. Preservation has lit the way for adapting the old for exciting new use, particularly in housing—from forgotten factories to former schools. And now, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s

a heightened awareness of the necessity of light and air and investing in a public realm that supports human needs, civility, and shared culture.

I led a campaign for many years to force the issue of overcrowding at Penn Station in New York City, crippled by toxic conditions long before this year’s pandemic. The former Penn Station, demolished in 1963, protected an open landscape of tracks and platforms. Once demolished, over 1,100 columns were dropped onto those platforms to support the new arena above. It became a station redesigned to accommodate 120,000 people a day, but, by 2020, it was serving over 600,000 passengers. By obliterating the dignity of the old Penn Station, its inherent conditions for sustainable use were also destroyed. It’s a striking contrast to the preservation of Grand Central Terminal, as its thoughtful original master plan and design have consistently supported evolving contemporary needs. The restoration of Union Station in Worcester [Massachusetts] not only saved an iconic and historic structure but helped spark a reimagining of its industrial neighborhood, including housing conversion, and the reknitting of the city center from the station to city hall. A core truth of historic preservation is reuse, making it a leading approach for sustainability and in climate solutions.

Nonprofit cultural organizations are facing challenges due to COVID-19. How does it feel to take on a new leadership role in this sector at this time?

It’s an unprecedented and challenging time for everyone,

every global citizen. We need to be there for our families and our communities, for one another, in every way we know how. Historic New England—its mission and vital work, its responsibility to the many communities it supports, its staff, volunteers, members and supporters, its long history of stewardship of our shared cultural heritage and advocacy for the region’s precious environmental resources—all of this must be there, be ready, and be even stronger when this pandemic ends. This is what New Englanders need and expect from us, what they are counting on from us, and it’s what we expect from ourselves. It’s a daunting time, which must be met with thoughtfulness and care, imagination, creativity, open communication, and total determination. I’m humbled and honored to share in this charge.

What are you looking forward to most about returning to work in New England?

We’ve been very blessed living in Southport, Connecticut, the last two-plus years, so I’ve had the opportunity to reconnect more directly with our region’s cherished landscape. There is nothing like the natural and built resources of our region. Thanks to Historic New England and other wonderful preservation organizations large and small, so much of what is distinctive has been protected. Of course, there is so much more work to do. I’m so excited to have the opportunity to focus on the priorities of our organization, advancing the conversation and our impact. And as a native son, there’s nothing like being home with fellow New Englanders!

by KRISTEN WEISS Cogswell’s Grant Site Manager

by KRISTEN WEISS Cogswell’s Grant Site Manager

COGSWELL’S GRANT IS full of stories—the story of an object, the story of an artist, the story of a house, the story of a family. Bert and Nina Little—the last owners of this eighteenth-century farmhouse

located in Essex, Massachusetts— collected stories with each antique they acquired. There is also the Little family’s story of life on a farm: summer picnics, classic cars, original plays produced by the kids in the barn, and raising pigs named

Hamlet and Ophelia.

Bertram K. Little was director of Historic New England (when it was called the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, or SPNEA) from 1947 to 1970. Nina Fletcher Little wrote

six books and more than 100 articles and exhibition catalogues. The folk art that the Littles collected, or “country arts” as Nina preferred to call them, represents the lives and stories of ordinary people: household objects decorated by their owners; portraits painted by local, self-taught artists; rugs of homemade designs hooked with fabric scraps.

In the foreword to the 1998 edition of Nina’s book, Little by Little: Six Decades of Collecting American Decorative Art, the couple’s children wrote: “Visitors to historic American houses or museums with collections arranged in period rooms often

conclude that although they may be nice places to visit, no one would want to live there. … We are sure that those of you who have had the pleasure of visiting our parents have found just the opposite. Although the houses in which we were raised and have enjoyed much of our lives were certainly different from those of most of our friends and neighbors, they gave off a feeling of warmth, of informality, and especially of home.”

These words are confirmed today at Cogswell’s Grant. As the rooms are not very large and are full of furniture and original hooked rugs, and because there are no ropes or barriers that keep visitors at a

page 3

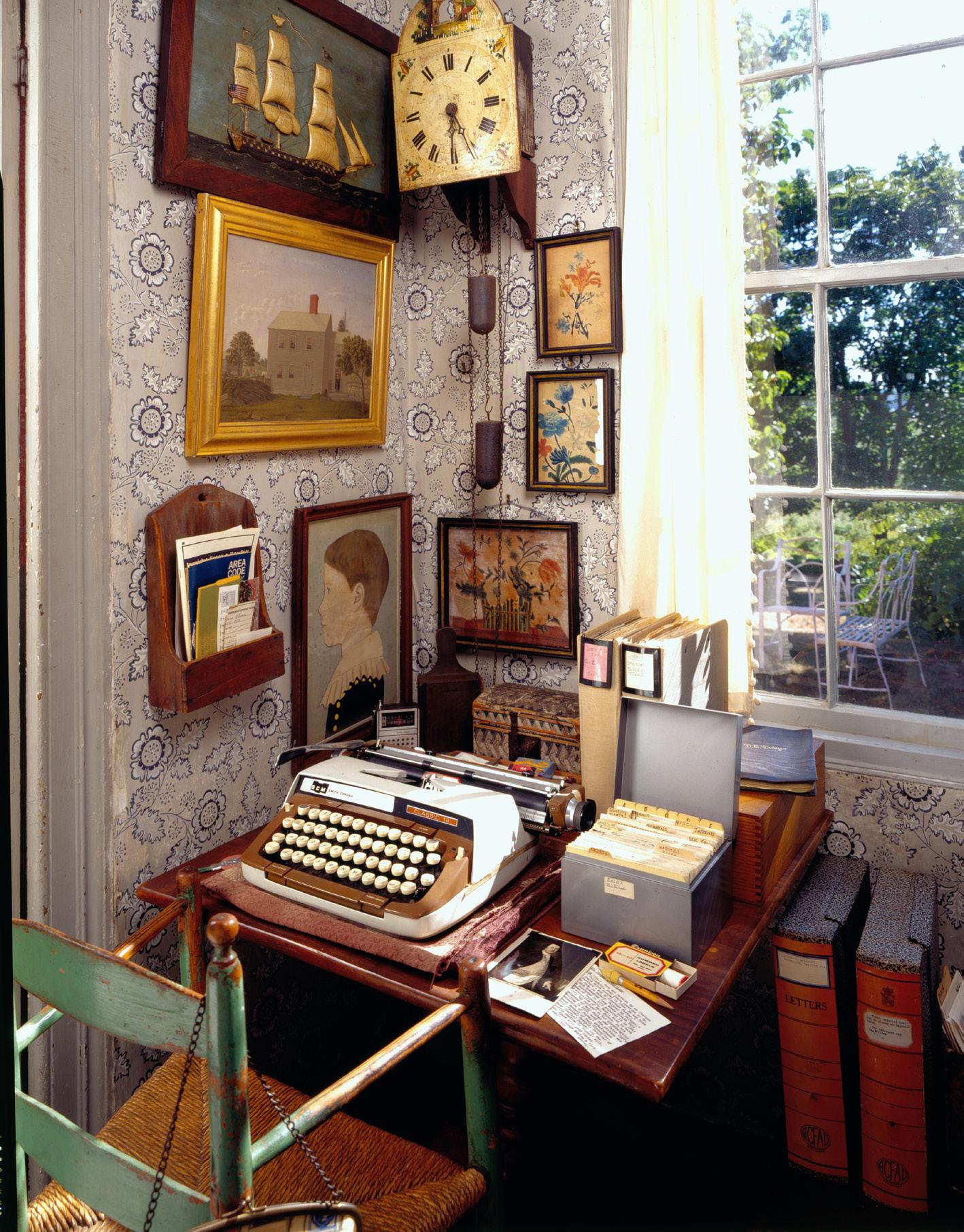

The Littles used nearly every conceivable space in their house to display their collected objects, even the attic. left Nina Little’s home office was a small space located off the sitting room in the farmhouse with a view of the terrace.

distance, tour groups are kept small to provide an intimate experience with the collections. Visitors often comment on how close they feel to the Littles, how at-home and comfortable the setting is. Bert and Nina were never interested in creating a sterile space that felt like a museum.

In 1925, when Nina Fletcher and Bertram K. Little wed, neither had any notion that they would become two of the most prominent collectors of American folk art and antiques in the nation. Bert had grown up on Chestnut Street in Salem, Massachusetts, surrounded by old buildings, old furniture, and stories of old times in this important colonial seaport community. Nina had been brought up in a house in Brookline, Massachusetts, built and furnished around the time of her birth in 1903. As a young married couple, they quickly gravitated toward the history, architecture, and antiques that would come to define their life together.

The young couple purchased a retreat cottage in the Massachusetts mill town of Hudson in Middlesex County, not far from Bert’s cousin Edna Little Greenwood. In their zeal to restore and furnish the c. 1825 house, they consulted Edna, a collector whose home, Time Stone Farm in nearby Marlborough, was full of early American artifacts. Edna’s passion for the stories behind everyday objects clearly influenced Bert and Nina as they followed her to auctions and sales and began their own collection.

In 1937, they decided to look for a larger summer home for their growing family, something more convenient to Boston and where they could emulate the atmosphere that Edna had created at Time Stone Farm. Essex provided the perfect location, with a 165-acre salt marsh farm and eighteenth-century buildings that were crying out for loving attention. In researching the history of the property, Nina discovered that the Town of Ipswich had granted the land to

John Cogswell in 1636. She named the property Cogswell’s Grant. “Our newly acquired farmhouse had dozed in the sun for two hundred years and had mercifully escaped the hand of the ubiquitous ‘restorer,’” Nina wrote in Little by Little

Their own restoration was carefully documented and extensively researched, and while they were very respectful of the remarkable surviving eighteenthcentury material in the house,

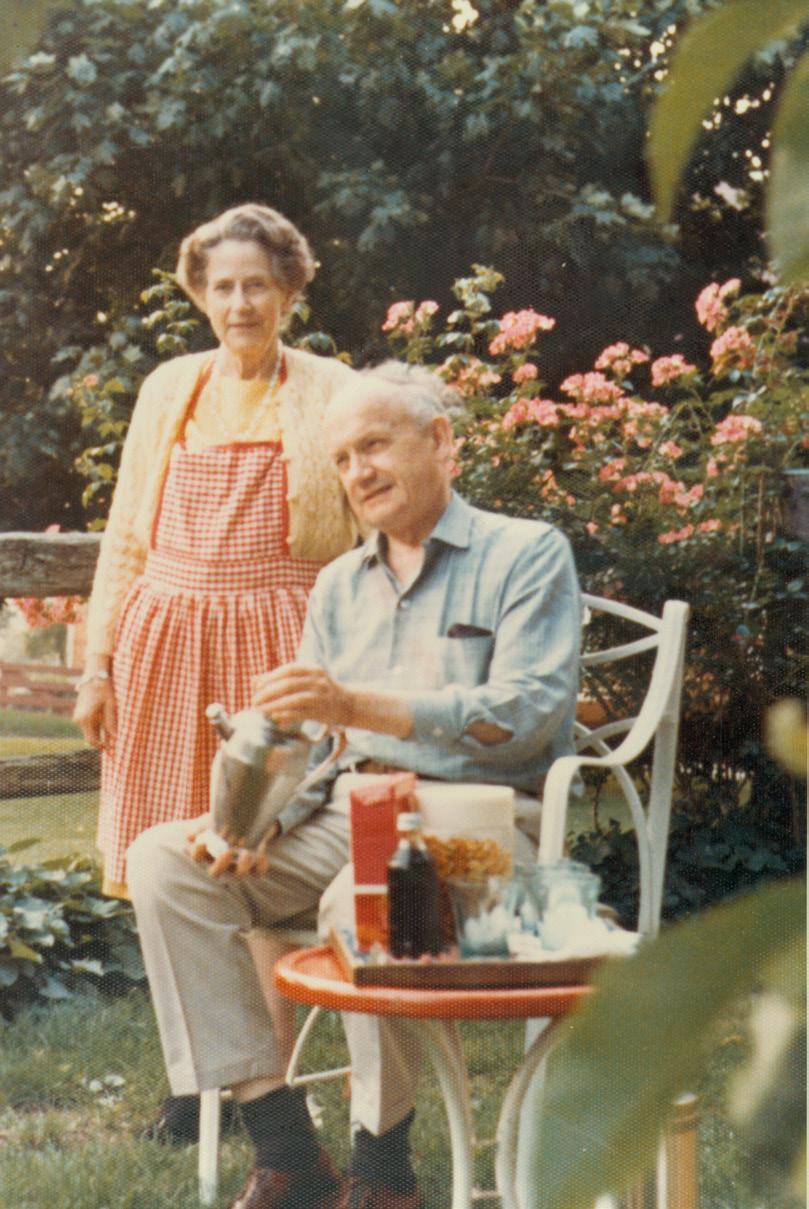

Nina and Bert Little on the terrace of their eighteenth-century home. below The upstairs guest room features a child’s bed. On the mantel is a set of carved wooden geese; the one at the far left is featured on the cover of this issue. Nina bought the set in 1962.

they installed electricity, plumbing, and upgraded bathrooms. The Littles also expanded the service wing of the farmhouse to include a large modern kitchen and more comfortable living quarters for the farm caretaker families who were an important part of life at Cogswell’s Grant.

A crucial part of the restoration was uncovering the secrets hidden under the painted white woodwork and trim throughout the house. Knowing that the paneled woodwork of the Georgian period was often decorated with landscape paintings or other scenes, the Littles invited Esther Stevens Brazer, a specialist in decorative painting, to help investigate. What they uncovered were samples of colorful graining and marbling. As it would have been extremely time consuming to remove the later paint from all the

woodwork, they hired Brazer to recreate the original paint schemes.

Paint decoration is not only an important part of the restoration of the farmhouse at Cogswell’s Grant, but it is also a critical aspect of the Littles’ collecting. In addition to her research on American decorative wall painting (which resulted in her book of the same name published in 1952), Nina was one of the first collectors in the twentieth century to appreciate painted furniture finishes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

At the time she and Bert were collecting, painted surfaces were not highly valued. If an early piece had a painted finish, which may have been added later to enliven it, the prevailing practice was to strip it off and “restore” the piece to its presumed original look. Nina and Bert cared about the whole history

Even though a previous owner may have altered an object, such as the finish given to this eighteenth-century table, the Littles believed that such modifications added to the history of a piece and that it should not be restored.

of an object and refrained from changing things whenever possible. About one eighteenth-century dressing table with a nineteenthcentury graining decoration and newer wooden drawer pulls (shown at left), she said: “A number of people have asked us why, such an early piece, that we didn’t take off this finish which, obviously, was not suitable to its origin, and replace the old brasses, but we never have even considered this because this finish has now been on there probably 130 or 140 years, and we like it, we think it’s interesting to see how the piece has developed.”

This appreciation for the history of an object and her desire to connect with the stories of the people behind the pieces came through in Nina’s extensive research of all her collections. Origins, purpose, maker, owner, subject matter; she considered all of them important to the full enjoyment and appreciation of that object. “Those who collect knowledge along with their teapots,” Nina said in an article in the July 1939 issue of The American Home magazine, “will seldom be downhearted and will never be bored.” Today, her detailed records provide us with in-depth information about objects in the house that we share with visitors.

Cogswell’s Grant is temporarily closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but you can experience the site through the wealth of records available online at HistoricNewEngland.org/ CogswellsCollection.

Little Women made a big splash when it hit theaters last December. Screenwriter and director Greta Gerwig’s new-fashioned adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s 1868 novel was filmed entirely in Massachusetts. And why not? The original story is set in a town Alcott based on her hometown of Concord, and Massachusetts offers competitive incentives to encourage filmmakers to

spend their production dollars in the Commonwealth.

An added bonus is that Massachusetts is steeped in history, providing location scouts with an abundance of options for filming. Historic New England’s Lyman Estate in Waltham (just twelve miles southeast of Concord) was one of several historic sites Gerwig chose for Little Women. In the pivotal scene when Jo March (played by

Saoirse Ronan) and Theodore “Laurie” Laurence (played by Timothée Chalamet) dance for the first time, the pair twirl their way around the Lyman mansion’s candlelit veranda as beautifully costumed dancers can be seen through the large windows waltzing in the ballroom.

In The New York Times’ “Anatomy of a Scene” YouTube interview, Gerwig breaks down the Lyman Estate scene in “How Little Women Throws a Dance Party.” After struggling to find a long hallway in which to film the dance, she explains, “I kept coming back to this location because I liked it, and then I came back at night and thought, ‘Oh, you could see the dancers through the window, and then see them outside as these figures having their little party on the porch.’”

Filming opportunities like this offer Historic New England national, and even international, visibility as well as location fees to support operations. In turn, filmmakers have access to authentic settings in which to tell their stories.

This is not the first time a Historic New England property has appeared on the big screen. Forty years before Ronan and Chalamet’s dance, The Europeans was filmed at Barrett House in New Ipswich, New Hampshire. The 1979 Merchant Ivory Productions film is based on the 1878 short novel by Henry James that was first published in The Atlantic Monthly as a serial.

Nominated for an Academy Award and a Golden Globe, The Europeans is the story of two destitute siblings (played by Lee Remick and Tim Woodward) who come to New England in the mid-nineteenth century to visit the Wentworths, their wealthy and somewhat stuffy uncle and cousins. Barrett House, a grand country mansion built c. 1800 that features lavish furnishings, French wallpaper, and a third-floor ballroom, provided the ideal setting for the Wentworths’ home.

Feature film production opportunities like Little Women and The Europeans are infrequent, but it’s quite common for Historic New England to work with filmmakers and television program creators on smallerscale projects. In 2008, a decade before Gerwig’s Little Women, the Lyman Estate and nearby Codman Estate in Lincoln were settings for the award-winning PBS American Masters documentary “Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind ‘Little Women’” that sheds light on Alcott’s personal and professional life. Although best known as the author of the Little Women trilogy and other young adult novels, Alcott also wrote prolifically in other genres under the pen name A. M. Barnard or sometimes anonymously. It wasn’t until the mid-

twentieth century that a pair of researchers and writers, Leona Rostenberg and Madeleine Stern, discovered Alcott’s pseudonym.

A contemporary of Alcott, poet Emily Dickinson, is the subject of Dickinson, the web television series that premiered on Apple TV+ last year. Dickinson and Alcott were born two years apart (in 1830 and 1832, respectively). Both were raised in New England and, through their writing, pushed the boundaries of women’s roles in the nineteenth century. Historic New England’s part in the Dickinson series hasn’t been as a filming location but as a resource for set design.

With hundreds of thousands of decorative arts items and photographs, Historic New England’s collection is an outstanding reference for set designers who are recreating period interiors. Through our rights and reproductions program, Historic New England has provided the makers of Dickinson with periodappropriate inspiration by sharing images of decorative objects from portraits, still life paintings, and landscape scenes, to nineteenth-century wallpapers.

Much as the Internet has changed the way viewers access programs like Dickinson, it has changed the way set designers access Historic New England. What was once an initial telephone inquiry to the curatorial staff is now more often an initial visit to HistoricNewEngland. org to search our digitized collection for resources.

Not all productions require historical settings or set design accuracy. In sharp contrast to these period films, the makers of Moonrise Kingdom contacted Historic New England when looking for open space. Filmed in part in the fields and meadow of Watson Farm in Jamestown, Rhode Island, Moonrise Kingdom is a coming-of-age story of two runaways, played by Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward. Watson Farm is the backdrop for the scene where the couple meets up before fleeing. Also starring Bruce Willis as the police captain, Moonrise Kingdom premiered at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival and received Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations.

Sprinkled among these larger productions are requests by makers of smaller local and regional documentaries, student films, and videos for colleague museums and other nonprofit organizations. Whether searching for a period-appropriate filming location, recreating historic interiors, or identifying the ideal landscape backdrop, filmmakers, program creators, and videographers have long relied on Historic New England. We welcome these opportunities to share our resources in often unexpected ways.

That chilly week in November 2018 was a memorable one at the Lyman Estate in Waltham, Massachusetts. The property, also known as The Vale, was the setting for a jubilant holiday party filmed for the latest adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s endearing Little Women. Sequences were shot in the east parlor, the ballroom, the hall, and on the veranda. The scene featuring Jo and Laurie dancing alone on the veranda has since become iconic. For many of our visitors and wedding couples, that is the pivotal moment in the movie.

The mansion was filled with every possible player, from 1860s food specialists, to lighting technicians, to the talented cast of performers led by Saoirse Ronan, Timothée Chalamet, and Emma Watson, to the star director, Greta Gerwig. Outside, there were makeup and hairdressing trailers, enormous lighting dollies, a huge catering tent, and cables and wires running in every direction. Historic New England had staff members on duty during the filming, representing different services within the organization: collections, property care, administration, and site management. The film staff invited us to dine in the catering tent with the cast and crew, and we got to see the scenes shot in real time on monitors.

by PATRICK MCNAMARA Functions ManagerThe movie crew makes late-night preparations outside the Lyman mansion to film the scene where Jo and Laurie dance exuberantly on the veranda. Photograph courtesy of Sony.

This is how Historic New England landed a “role” in the movie: I was at The Vale one afternoon in summer 2018 when three gentlemen stopped by, explaining that they were a preproduction team scouting movie locations. They did not mention the name of the movie or say who was involved; they left, saying they might be back in a couple of weeks and would let me know, but to please keep it hush-hush. Two weeks later I got a call asking if they could stop by that afternoon. They wanted to bring the director to see the Lyman Estate, and if she wasn’t interested, she would leave right away. The director they introduced was, of course, Greta Gerwig, and she stayed for a couple of hours. She was kind, affable, and unassuming. We all liked her very much.

On her second visit, Gerwig met Nicole Skarbek, the Lyman Estate’s functions coordinator, who was with a wedding tour in the mansion’s Blue Suite, showing photo albums to a future bride. Also looking at albums across the room was Gerwig, who graciously apologized for being in the bride’s way. The delighted bride recognized her immediately and said she was a big fan. During the ensuing conversation, Skarbek mentioned that she always suggests that wedding couples have their first dance on the veranda.

The bride, Jennie Levangie Brennan, recalled, “Greta Gerwig was lovely, and, together we looked at albums from past weddings. I like to think we talked each other into using the Lyman Estate, as my husband and I were married there in April 2019, and Greta filmed scenes for Little Women on the beautiful veranda.”

Updated tour gives a presence to the enslaved at Sayward-Wheeler House

One was called Prince, another answered to Cato. There was Dinah; she and Prince were married. And decades before those three, there was Boneto. Each was considered to be the property of a prominent resident of York, Maine.

Until now, these enslaved individuals received minor mention in Historic New England’s story of Sayward-Wheeler House (c. 1718) in York Harbor, Maine. The reason

for this goes to the heart of the challenge of drafting a new, inclusive story and reexamining how objects and narrative work together in recounting the past.

Historic New England’s updated narrative of Sayward-Wheeler House considers the home of wealthy merchant and judge Jonathan Sayward (1713-1797) through multiple points of view, substantively those of Prince and Cato, enslaved men who lived and worked at the house

in the late eighteenth century; Dinah; and Boneto, an Indigenous enslaved person held at the house in the early eighteenth century.

Sayward-Wheeler House, which Historic New England acquired in 1977, has long been prized for its collection, notably its nearly intact eighteenth-century parlor. The rooms and objects tell a particular story of a house passed down through one direct family line, from Jonathan Sayward’s father, Joseph,

to Elizabeth Cheever Wheeler (1862-1947), Jonathan’s great-great granddaughter.

Historic New England's previous narrative centered on Jonathan Sayward, a prestigious York resident who made his wealth primarily through shipping.

JerriAnne Boggis, executive director of New Hampshire Black Heritage Trail, a reviewer for the new presentation, noted that the fact that Sayward was a shipping merchant provides “a way in” to begin investigating other aspects of the narrative. “Do we know what he was shipping? It’s a way to talk about the transatlantic slave trade,” she said.

Sayward was involved in the fur trade with Canada and the timber trade with the West Indies. The latter was a major link in the transatlantic slave trade, connecting the economies of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. One leg of this triangular trade system was the Middle Passage, the forced transport of an estimated 12.5 million Africans to the so-called New World from the 1600s to the mid-1800s. In the West Indies, timber was needed for construction and fuel for the intense sugar production operations. New England merchants not only sold timber in the West Indies but also foodstuffs that plantation owners used to feed the enslaved population. In

exchange, New England merchants purchased sugar, molasses, and people. In countless deals, New Englanders also sold Indigenous people to slavers in the Caribbean.

A Loyalist during the Revolutionary War, Sayward’s political position offers a compelling narrative—that of an orderly man who foresaw potential disaster between the colonies and the crown—and a nuanced look at an era that is often oversimplified in its retelling.

Sayward’s story is supported by the diaries he kept from 1760 to 1797 and by the objects on view in the house. For example, in a May 1777 diary entry, Sayward recorded his anxiety—the Loyalist feared for his safety because of threats by patriot mobs. “I heard the Clock every Hour last night. Little or no Sleep,” he wrote. The finely crafted tall case clock of which he speaks still stands in a corner of the sitting room, where it has been since the 1770s.

The tall case clock, probably the most expensive piece in Sayward’s home, can be used to explore another aspect of colonial history. The case is made of mahogany. This was a popular wood for furniture making in the eighteenth century and many fashionable homes in the colonies had mahogany furnishings. Enslaved people were used to harvest this wood, under wretched

conditions, in the Caribbean and Central America.

The story of Sayward’s anxiety is told through his own words. But what were the personal experiences of Prince, Dinah, Cato, and Boneto?

Among the most difficult challenges encountered when exploring the lives of marginalized and disenfranchised people is the scarcity of information left by or about them. Primary sources, such as letters and diaries, written by people enslaved during the eighteenth century are rare; nothing penned by Prince, Dinah, Cato, or Boneto is currently known to exist. Likewise, biographical information such as places of origin and destination if they became free—is often difficult to find. Without consistent surnames, and in some cases, not even a first name, hope for finding leads is slim. While some enslaved people were allowed to keep their names, slave traders and owners most often renamed these people with tags that ranged from classical literature references to satirical monikers, such as Prince (ironically, African royalty were among the enslaved). Church records, land records and quitclaim deeds, and wills might offer some basic information, such as marriage and death dates, and when freedom might have been obtained, either

through manumission or other means.

National Archives records reveal that Prince, who died in 1789, was a veteran and that in 1838, Dinah had applied to receive his pension. The Prince Sayward Revolutionary War Pension file contains witness statements submitted in support of Dinah’s application. In one statement, Nathaniel Donnell described Prince as having been “bright and active.” Donnell had hired Prince for “labor” as a free man after 1783, when Prince returned to York after serving in the Continental Army, service for which he was manumitted.

The National Archives file contains other vital statistics, such as the fact that the couple wed in 1780, as recorded by the First Congregational Church in York. At the time of their marriage, Dinah can be placed as an enslaved “servant” of York tavern proprietor Robert Rose. A nineteenth-century source recounts residents’ knowledge of Dinah—that she was fond of children and would sing to them. Despite being approved to receive her husband’s army pension, Dinah Prince died in a York almshouse in 1845. She was 101 years old.

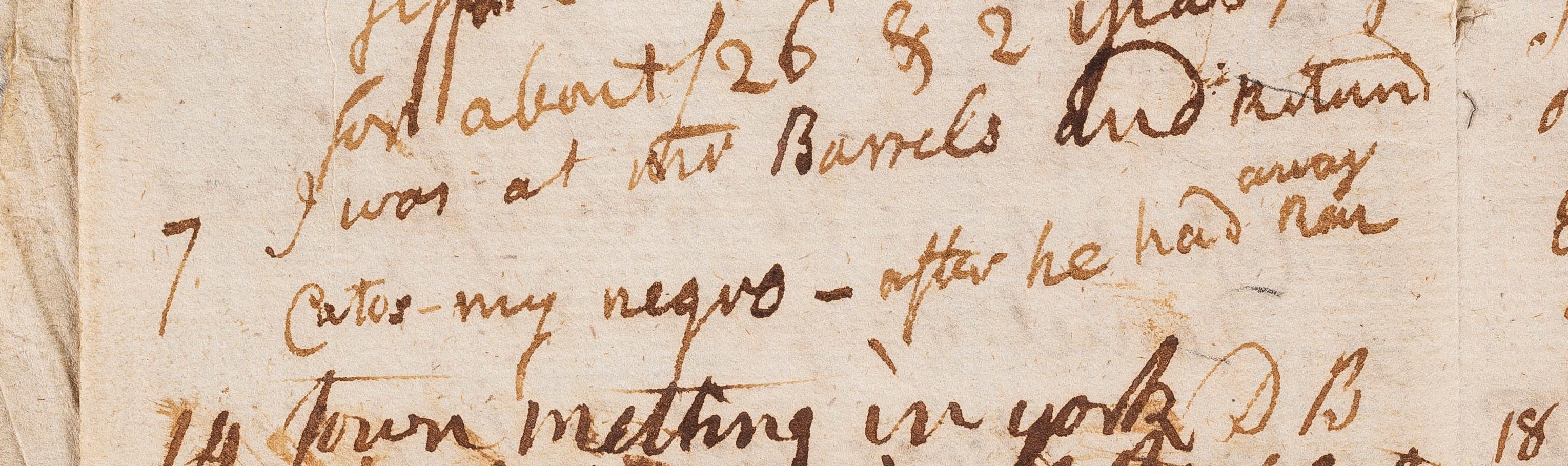

Cato, in source materials found to date, remains, as many of the enslaved of the era do, a figure who

appears only briefly in a moment of time. A diary entry Sayward wrote on March 7, 1769, reads: “I was at Mr. Barrels and Returned Cato—my negro—after he had run away.” Such information can prompt questions to fuel deeper research. “Mr. Barrel” is most certainly Sayward’s son-in-law, Nathaniel, who was married to his only child, Sally. The Barrells lived on a farm Sayward owned a few miles up the York River from his house. Had he “loaned” Cato out to Barrell? Had Cato run away before?

Escape was a common act of resistance that slaves employed. Others included work stoppage and sabotage. In a March 18, 1769, diary entry, Sayward wrote, “I lost one barrel of sugar by blacks dropping it overboard.” While this may not necessarily have been sabotage— it very well could have been an accident—that Sayward took the time to record the incident reveals his irritation.

It is known that Cato attained his freedom, again, from Sayward’s diary: “July 3, 1781: I sold Cato my negro his time for 275 Dollars.” It appears that Cato used the manumission provision of purchasing himself from Sayward.

There is a legal document on Prince’s manumission, signed by Sayward on April 9, 1781: I, Jonathan Sayward of York . . . for and in

The West Parlor at Sayward-Wheeler House. The portraits depict, from left, Jonathan Sayward; his first wife, Sarah Mitchell Sayward, who died in 1775; and Sally Sayward Barrell, the couple’s daughter. Photograph by Nicolas Hyacinthe.

consideration of thirty-six pounds lawful silver money to me in hand paid before the ensealing hereof by the Friends of Prince Sayward, a negro servant and slave, the receipt whereof I do hereby acknowledge I have remised released and discharged and to freedom and liberty set all my right title, claim, and service, whatever that I now have or ever had to or in the said Prince as my slave.”

As these examples show, even in indicating dramatic events in the lives of Cato and Prince, the story is still being driven by the white male enslaver.

In drafting narratives that take into account the perspectives of the enslaved, some clues exist in the material culture of the home. While the objects were Sayward’s property, they are a springboard for discourse. From a rare, single eighteenth-century wine glass to the tall case clock, a shift in perspective is needed. Who cleaned, dusted, and maintained the furnishings in the house? Asking more questions, Boggis said, is vital: “Where in the house did the enslaved sleep? Who was cooking the food? What did they make? Many were skilled laborers.”

As the stories of SaywardWheeler House unfold and their telling evolves, reexamining our perception—and preconceived notions—of objects will continue to be the key to recounting these toolong-unheard stories.

We look forward to welcoming visitors to Sayward-Wheeler House when the site reopens. In the meantime, we continue to research and better understand these untold stories.

If you own a historic house, being a Historic New England member at the Sustainer level and above gives you access to expert advice on caring for your home inside and out.

Senior Preservation Services Manager Leigh Schoberth will answer your questions on topics ranging from appropriate paint colors to how to evaluate a contractor’s proposal. This premium membership benefit is an opportunity to access the knowledge Historic New England staff has gathered from working with homeowners and historic properties across the region.

Historic houses present many

questions and issues, some of them perplexing and others fascinating. Weatherization and insulation, paint colors, and dating a house are frequent subjects homeowners ask us about. What energy-saving measures should I use that will not damage the historic fabric of my home? What are appropriate interior and exterior colors for a Colonial Revival or Victorian-era house? Should my floors be painted? Is my mantel original or a later addition? How do I date an architectural detail or style?

“You can do an Internet search and come up with ten different answers to a question,” Leigh said.

That can further complicate matters, but by consulting Leigh, you will get information that is specific to your home and situation.

Besides offering individualized assistance on technical and aesthetic questions, memberships at the Sustainer level and above come with several other benefits, including exclusive pop-up tours of privately owned historic houses and monthly newsletters tailored to owners of old homes. For more information on historic homeowner services memberships, visit historicnewengland.org/get-involved/ memberships/.

by SALLY ZIMMERMAN Retired Senior Preservation Services Manager

by SALLY ZIMMERMAN Retired Senior Preservation Services Manager

Last summer, three Middlebury College students spent June and July studying Historic New England’s properties in Newbury, Massachusetts, to identify and assess the current and future effects of climate change. Climate change, defined as a shift in global or regional climate patterns based on increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide produced by the use of fossil fuels, is already altering

many aspects of New England’s weather patterns.

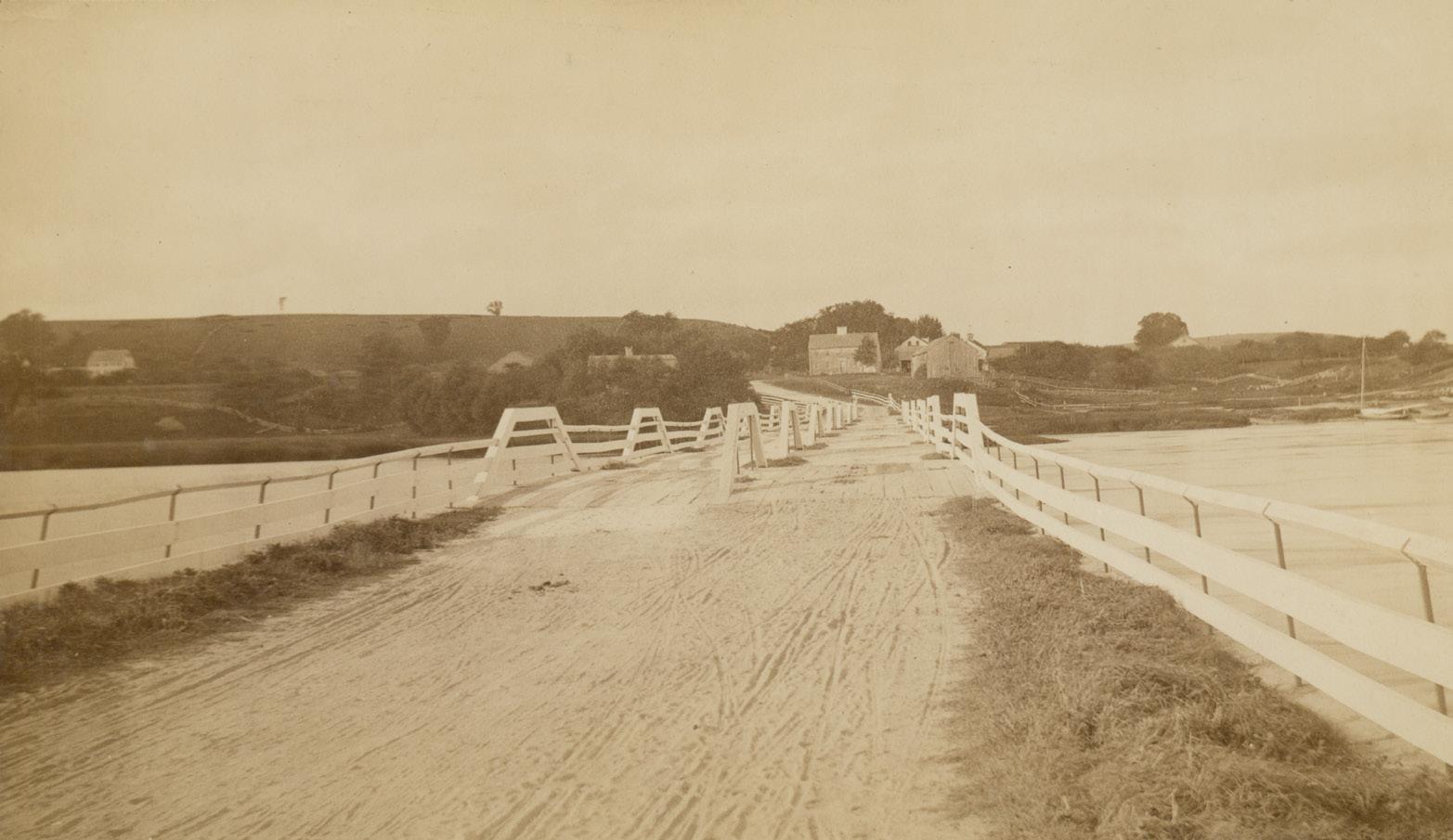

The town of Newbury, which fronts the Atlantic Ocean and is bounded north and south by the Merrimack and Parker rivers, is a bellwether for the shifting climate. It is also home to Historic New England’s largest concentration of museum sites, including the SpencerPeirce-Little Farm and the Coffin, Swett-Ilsley, and Dole-Little houses.

This concentration of historic sites provided the impetus for the Middlebury interns’ project: the second phase of a two-year effort on planning for climate resiliency. The three interns—Ben Johnson, Tenzin Dorjee, and Jonathan Fisher—looked at short- and long-term threats and ways of adapting the four properties to meet the coming climate challenges.

Johnson, an architectural

studies major, evaluated gutter and roof drainage at the four houses, using the gutter capacity formulas developed at Historic New England’s Maine properties. Geography majors Dorjee and Fisher researched data on invasive species and sea level and inundation threats. Among other tasks, Dorjee identified tree

species that are resilient to higher salinity groundwater, which threatens the root systems of traditional hardwoods such as maples. Fisher applied Geographic Information Systems (GIS) data to predict flooding and other risks at SpencerPeirce-Little Farm, the property most vulnerable to changing sea levels.

The work of our interns showed us that the threats and changes to our historic properties and landscapes are varied and in some cases, quite imminent. With the products of their research, Historic New England will be better able to plan for and adapt to the changes on the horizon.

An eighteenth-century barn tilting pathetically on its foundation as vines grow through the roof. A notice in the window of a nineteenth-century commercial building that the owner has applied for a demolition permit. There are so many forces working against preservation in towns across New England. What can concerned citizens do to preserve the history in their communities in the face of such challenges?

Gone are the days of members of determined women’s groups chaining themselves to buildings or staring down wrecking balls. Preservation in the twenty-first century requires planning and vision, and starts well in advance of construction vehicles arriving on site.

1. Understand the place: The first thing a community advocate needs to know about saving a historic place is why that place matters and to whom. Not all buildings are historically significant and some historic buildings deserve a more sensitive preservation approach than others. There are many sources available to research a property, starting with municipal tax assessors’ records, which detail who owns the property, the approximate square footage of buildings and land, and the property’s estimated value. Searching the local history section of the community library, the state’s historic resources inventory forms, and the National Register of Historic Places database may yield

information about the architectural and social history of the property and its historic value within the neighborhood. Online resources like Google Books and Ancestry.com can provide important background information about the memories, traditions, history, and beauty represented by an old building.

2. Build a team: Preservation advocacy does not occur in a vacuum, so it is important to build a team of support for any endeavor to save a historic place. Additional voices, expertise, and perspectives are critical to any successful preservation effort. Fellow advocates might include neighbors, community leaders (such as representatives of churches, nonprofit organizations, businesses, and schools), architects, developers, attorneys, real estate agents, and people with experience in finance and economic development. It’s important to establish a point person for the group who will coordinate everyone’s efforts and make sure that the group is speaking with one focused, consistent voice. It’s also important to recognize the capacity of the group to work on this issue and to manage expectations and responsibilities carefully.

3. Develop a vision: Community advocates need a clear vision for what “saving” a historic place means. This starts with a reality check: How imminent is the threat and what can realistically be achieved in the time available? Some properties may benefit from a short-term

solution—persuading the municipality to impose a delay on demolition, encouraging an owner to address deferred maintenance, or even purchasing the property. While these strategies will not address the ongoing preservation of the property, they will buy time while longer-term solutions are developed. More sustainable, long-term approaches might include protecting the property with a perpetual preservation easement, creating a local historic district, or developing adaptive use models that support the continued maintenance and use of the property in a sensitive way.

4. Communicate effectively: When building a case for preservation, community advocates must consider the audience they will try to persuade. While educating people about the history of a place is worthwhile, decisions on whether and how to preserve a place are often made based on economics and regulatory requirements, so advocates must focus on bringing practical solutions to the discussion and be flexible when confronted with opposing viewpoints.

Approaching a property owner, developer, or elected official with respect and seeking to understand their priorities and values will help facilitate an open dialogue and lead to the best chance of a successful outcome. Allies in statewide preservation advocacy organizations, the State Historic Preservation Office, the local historical commission, or elected officials may

After a multiyear community effort to save Clinton African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Great Barrington, in 2018 Preservation Massachusetts added the building to the listings in its Most Endangered Historic Resources Programs. While the designation is honorary, it can help to promote action and marshal opportunities for preservation aid. The listing gives greater exposure to the work of Clinton Church Restoration (CCR), a nonprofit established in 2016 by a group of community members. CCR’s initial campaign to raise $100,000 to buy the vacant church building, which had been placed on the market, exceeded that goal in just five months, enabling the group to purchase the property in May 2017.

The preservation of Clinton Church, a Shingle Style structure completed in 1887, is part of a growing nationwide movement to save African American historic places. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008. In addition to its architectural significance, Clinton Church is associated with Great Barrington native W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963), a sociologist, historian, author, civil rights activist, and one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. The first black person to receive a doctorate from Harvard University (in 1895), Du Bois is still regarded as a preeminent scholar.

CCR is well on the way toward fulfilling its mission to restore the property as a heritage site and visitor center that interprets Du Bois’s life and legacy, celebrates the history of African Americans in the Berkshires, and honors the story of the church and the work of its first female pastor, Rev. Esther Dozier, who served from 2000 to 2007.

Preservation Massachusetts, a nonprofit based in Plymouth, is a statewide advocacy and education organization dedicated to preserving the Commonwealth’s historic and cultural heritage.

–Dorothy A. Clark, Editorbe able to assist in refining an approach or overcoming obstacles.

5. Succeed (or fail) forward: Finally, whether or not a community advocate succeeds in saving a historic place, it is vital to recognize the awareness and momentum created by the effort and to use that momentum to help preserve other significant places in the community. This is the opportunity to lay the groundwork that the group wished was in place before the last challenge. Engage

in a survey of local resources to determine which merit preservation, document places that may become threatened, work with the municipality to strengthen local regulations, educate elected officials about the value of historic places, and build a coalition of engaged citizens to carry forward the charge. Because, ultimately, being a preservation advocate and saving historic resources is a task that is never finished.

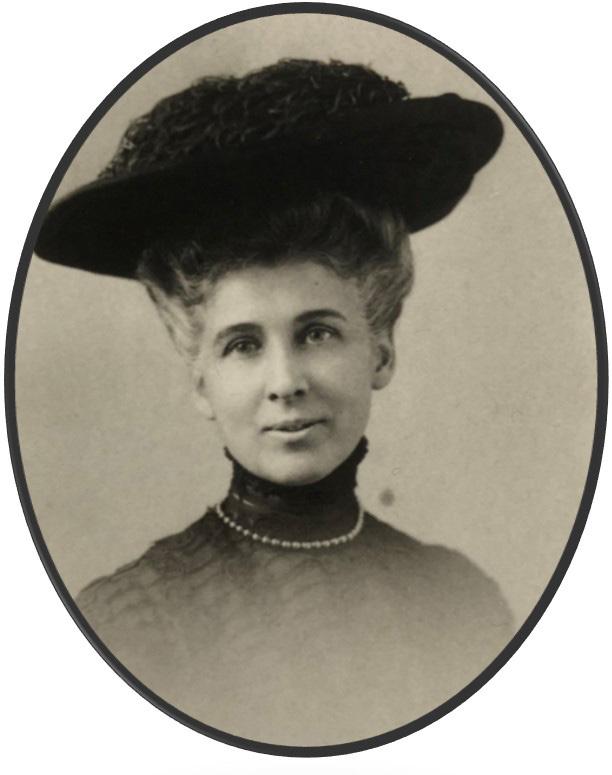

Visitors often marvel that Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, on Eastern Point in Gloucester, Massachusetts, feels like its owner just walked out and closed the door. The house is a magical

collection of decorated rooms preserved as Henry Davis Sleeper, an interior designer, created them in the early twentieth century. While we are grateful for this remarkably intact collection of original furniture, textiles, paint colors, and decorative

arts, we are equally frustrated because Sleeper’s personal papers did not survive. The lack of letters, diaries, and other documents makes it difficult to know much about his personal relationships and lifestyle.

Fortunately, over the years,

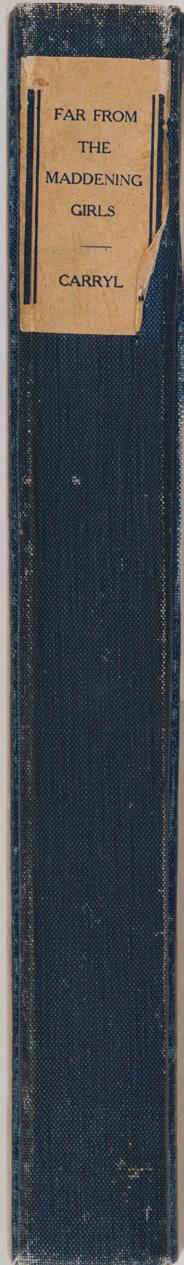

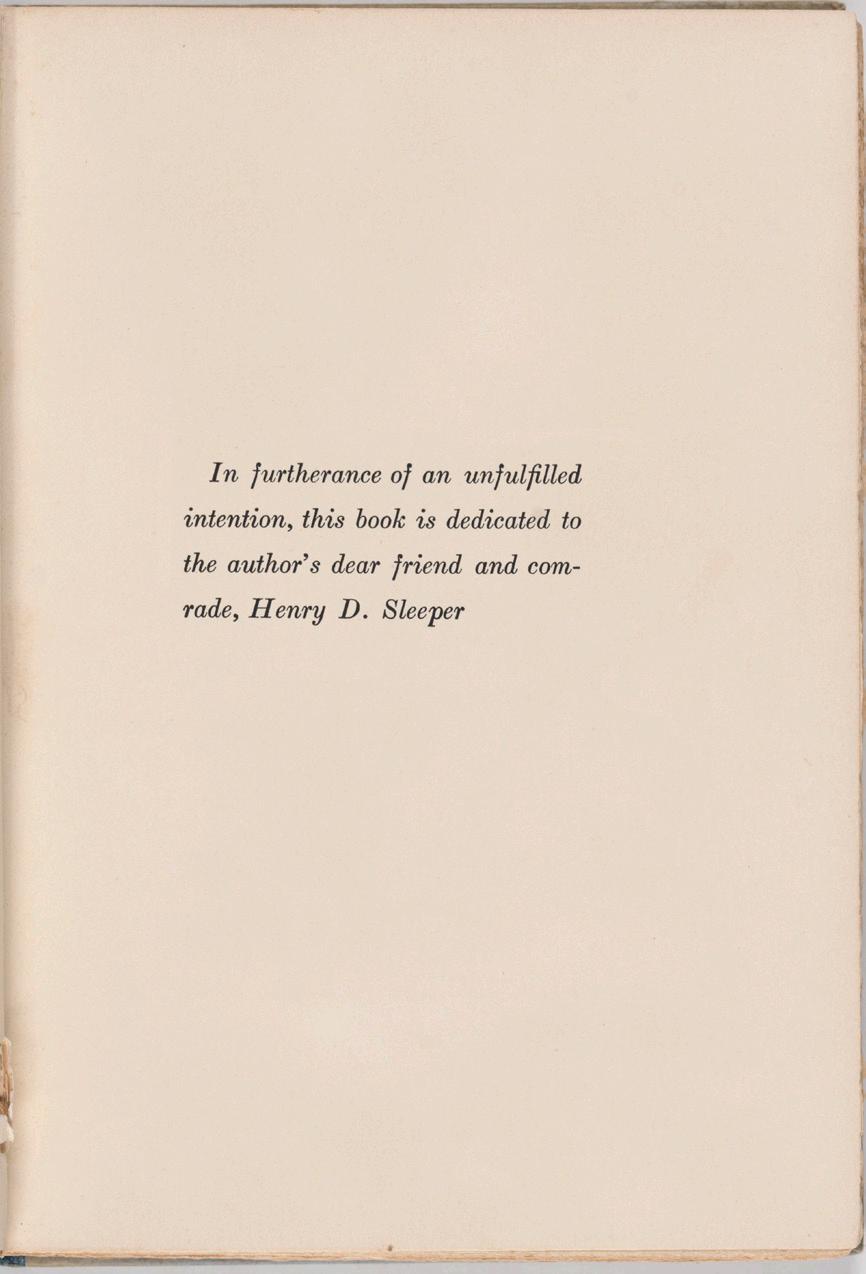

This nineteenth-century mourning-style collage has a place in the reading nook above Henry Davis Sleeper’s desk at Beauport. left Guy Wetmore Carryl (1873-1904), humorist, novelist, and poet, dedicated his posthumously published Far From the Maddening Girls to Sleeper. A New York Times review in December 1904 gave amused praise to Carryl’s novel, describing it as “like all his books, a lively tale.” The reviewer’s synopsis of this “readable” story: “A young bachelor, closely hugging his celibacy, built himself a spacious house a mile away from the nearest girl. But a mile, he discovered, possesses the elasticity of rubber, and can be stretched interminably or shortened correspondingly, according to—circumstances. …That mile and that girl prove too much for the young bachelor.”

letters and diaries left by Sleeper’s close friends have been found in private collections. These small treasures offer glimpses into the personal story of Sleeper, who was gay. Bit by bit, we are piecing together this oncehidden history and sharing it with visitors during the Beauport Pride Tour. These letters and diaries illustrate some of Sleeper’s closest friendships and reveal the deep affection within his close-knit group of friends.

In addition to readings from personal correspondence, the Beauport Pride Tour explores photographs, a book

continued on page 20

Summer is usually when we are most excited to welcome you to our historic homes and farms. A normal summer brings these places to life with tour groups from throughout New England and around the world.

With Historic New England sites temporarily closed due to COVID-19, these vibrant places are regrettably quiet. The list of canceled and postponed events is long, and the financial impact of unsold tickets and memberships is severe. We anticipate a loss of $3 million in revenue, roughly one quarter of our annual operating budget.

As a regional organization, we must follow guidelines from all six New England states in order to define what reopening looks like. We are also looking at federal and, in some cases, municipal guidelines as well as recommendations in the museum field for keeping visitors and staff safe. For the moment—or, at least, as this issue goes to print—it is impossible to say exactly when reopening will happen, so we are focused on planning how to do it in a way that is safe and worthwhile.

In the meantime, we continue to expand the number of online programs, including livestream events and online ordering for plant sales, available at HistoricNewEngland.org. Our education team is offering school and youth programs over Google Meet. The opening of our major exhibition, Artful Stories: Paintings from Historic New England, is rescheduled for fall, but you can explore the online exhibition at eustis.estate/location/artful-stories/. Our Collections Access database (HistoricNewEngland. org/collections) is an ever-growing trove of objects and archives, recently surpassing 200,000 records.

Several articles in this issue invite you to reconsider the stories at our historic sites: experiencing Sayward-Wheeler House in York, Maine, from the perspective of enslaved people; celebrating Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House in Gloucester, Massachusetts, as a rare historic house museum commemorating the life of a gay man in the early twentieth century; and discovering something new within the folk art collection at Cogswell’s Grant in Essex, Massachusetts. While you may not be able to experience these stories firsthand right now, you can be sure that our staff is working hard to expand the points of view represented in our historic buildings, landscapes, and collections.

Historic New England celebrates its 110th anniversary this year. You, our members, are the reason for this longevity. We thank you for continuing to support our mission even while the circumstances may prevent us from welcoming you in person. We miss you, and we can’t wait to see you again.

Sincerely,

Historic New England Staff and Volunteersdedication (on page 19), a 1930 coffee advertisement, and even a nineteenth-century mourning-style collage (on page 18), all of which offer clues about Sleeper’s social circle and the larger society.

What these items can never do is answer all of the questions visitors have about Sleeper’s private life. In many ways, the Beauport Pride Tour raises more questions than can be answered. The tour embraces these questions as a gateway to broader

discussions about the challenges of presenting LGBTQ history.

Missing or destroyed archival material is a common situation that many LGBTQ historians encounter. How do historians tell the stories of people whose lives were edited by the subjects themselves or by later generations? Defining terms of affection, which are very different today than they were 100 years ago, is another challenge. How does a modern reader give meaning to

historical texts that use words so differently? How can visitors use current language and identifying labels when describing historical figures?

These discussions are the heart of the Beauport Pride Tour. Sleeper’s story resonates with modernday visitors, who begin their own conversations and explorations of those people history has marginalized, including the LGBTQ community.

Beauport, the SleeperMcCann House in Gloucester, Massachusetts, has undertaken the exploration of LGBTQ history and hosts the specialty Beauport Pride Tour in collaboration with The History Project. Established in 1980, the Boston-based History Project is an independent organization that documents, preserves, and shares the history of LGBTQ communities in New England. It maintains one of the largest archives of LGBTQ history in the United States.

Henry Davis Sleeper (18781934) designed and built Beauport in 1907. The Arts and Crafts style house stands as the culmination of his life’s work and holds the largest collection of the objects he left upon his death. With so much of Sleeper’s personal life a mystery, the aim of the Beauport Pride Tour is to make known a history left out of the standard narrative of the past.

Historic New England’s partnership with The History Project has produced several presentations on figures in LGBTQ history. These

include a talk by Jane Goodrich, author of the biographical novel The House at Lobster Cove. Goodrich shared stories about the inspiration for her main character, George Nixon Black Jr. The heir to a real estate fortune, a philanthropist, and Boston’s biggest taxpayer in the late nineteenth century, Black is noted for the summer mansion he commissioned the architectural firm of Peabody and Stearns to design in Manchester-by-the-Sea,

Massachusetts, called Kragsyde.

The History Project has many ongoing events, exhibitions, and working projects—such as its crowdsourced digital archives of pictures, videos, and stories—along with a blog and an ever-growing collection dedicated to the reclamation of a hidden past. Visit historyproject.org to learn more.

–Hannah Soucy Guide, Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House

All of us at Historic New England are grateful for your steadfast support and commitment to our success. We couldn’t save and share New England’s history without you, and your generosity is more important than ever. Thank you for your trust and for standing with us during these extraordinary times.

What an adorable kid! The birth this past spring of a female goat at the Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm in Newbury, Massachusetts, was a delightful event that has captured the hearts of many Historic New England followers on Facebook and Instagram, as well as our staff. On March 14 at 8:00 in the morning, Halley, a Nigerian Dwarf goat, gave birth to Comet. Premature but healthy, Comet—like her name—has been a bright spot for many who have viewed her, Halley, and the other goats via livestream videos at historicnewengland.org/say-hello-to-comet/. Halley and two other goats, Ursa and Aries, came to Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm through our partnership with MSPCA, the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Your donation can help support animal care at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm. To give, please visit my.historicnewengland. org/donate/i/annual-fund and be sure to write “SPL animals” in the Order Notes field.

Century-old reading group passes down love of literature

by BETHANY GROFF DORAU Regional Site Administrator, North Shore

On September 8, 1939, fifty-three-yearold Eleanor (Little) Baker was on her way home to Nassau, New York, from her family’s summer retreat in Maine. Though she had wished to spend the day with her cousins at the venerable Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm in Newbury, Massachusetts, her family obligations in New York were pressing. Eleanor, daughter of

a leading banker in Newburyport, Massachusetts, had married at age thirty-six after years of adventure and service, and her youngest son, Charles (father of current Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker), was just eleven. Unwilling to let the day pass without comment, she took advantage of a smooth stretch of road to dash off a quick letter to her cousin Agnes and the other members of the SpencerPeirce-Little Reading Club, or R. C.

The Spencer-Peirce-Little Reading Club held a lively centennial gathering— with occasional input by a cat—in February 2019 at the home of member Patty Ward. The selected reading was Gone So Long by best-selling local author Andre Dubus III. Photograph courtesy of club member Amanda Ambrose.

as it was known. “I have tried to think of something terse and witty for you to read. … Alas!” Eleanor settled on a poem instead.

Dear Reading Club, of thee I sing May twenty years before you fling New books as worthy as the old New arguments, new gossip bold New gals (perhaps), cakes manifold, And tea by gallons, hot or cold. Eleanor’s letter was one of a half dozen to arrive at the farm

These women were held together by their love of books and lifelong ties of friendship and family.

addressed to Agnes Little and bearing the regrets, fond hopes, and deep affection of the sender upon the occasion of the Reading Club’s twentieth anniversary. The writers varied widely in age and represented every point on the political spectrum. Bea Fisher, fourteen years Eleanor’s junior and a card-carrying Communist and pacifist, wrote from Brooklyn, New York, where she complained about having to buy her Daily Worker newspaper from the back of the cart. “In conservative Newburyport do you even know that paper?” she teased. “[I] try to understand why men continue to dance around this planet throwing bombs at one another and why Germany has no butter and the United States throws milk in the gutters. Vive la liberté!”

As Bea marched in the streets, fellow member Helen Hale Welch, who lived in town, was present for the anniversary celebration. Her granddaughter Beth Welch remembered her as “ultraconservative.”

Whatever their disagreements (there are frequent mentions of “dust-ups,” arguments, and debates) these women were held together by their love of books and lifelong ties of friendship and family. The core members of the Reading Club were Agnes, Margaret, and Amelia Little, the last generation of the Little family to live at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm; and their cousins; childhood friends; and neighbors.

Every Monday, beginning on September 8, 1919, the group gathered at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm or occasionally at the home of

another member. Each took turns reading aloud to the group, while the others tended to their work. During World War II, they rolled bandages and knitted hats and scarves for soldiers in addition to their usual mending, knitting, and sewing. Although they were warm, funny, and unguarded with each other, these women were serious about their book selections.

The group was guided in its early years by Eliza Little, born in 1861, an intelligent, powerful woman who had taken on the care of three of her nieces after their parents died. Though Eliza’s formal education ended when she was sixteen, she was fiercely protective of her family and her young charges were sent to college and encouraged to pursue intellectual and professional endeavors. Agnes, who graduated from Smith College, was a high school math teacher in Newburyport; Amelia and Margaret taught at private schools.

These were not women who read trifling books. They chose biographies (Thomas Jefferson, Mary Baker Eddy, Herman Melville, Queen Victoria, among them), philosophy (A Preface to Morals, The Story of Philosophy), politics (Democracy in Crisis, Red Bread), history (Eminent Victorians, The Flowering of New England 1815-1865), science (Microbe Hunters), the arts (Of Men and Music), and fiction (The Marble Faun). Refreshments were served— tea, sandwiches, and a “sweet,” with a winking mention of sherry on occasion.

As life changed for many of these women, with husbands, children,

careers, and travels calling them away, they returned when they could and always sent letters to Agnes, the unofficial secretary of the group. Agnes collected cards and letters sent on the twentieth anniversary of the group in 1939, and the fortieth in 1959. Letters from absent members were read aloud, toasts given, and poems recited.

Though the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the Reading Club is mentioned in several archival documents, the cards and letters that undoubtedly accompanied the event do not seem to have been saved. Agnes Little, who had retired from teaching, was slipping slowly into the dementia that would mark her last decade. By 1982, Amelia was the last living Little at the farm, though her younger cousins, members of the Reading Club like Nancy Noyes, remained regular visitors. Other surviving members of the club sent Amelia their best wishes on her ninetieth birthday.

Eleanor Little Baker died in 1983 at ninety-six; Amelia followed in 1986, leaving Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm to Historic New England as intended by the family. The Reading Club, with its legacy of humor, friendship, and rigorous discussion, lay dormant.

In 2001, struck by the humor, intelligence, and camaraderie evidenced in the Reading Club records that passed to Historic New England along with the property, the farm’s site manager, Maggie Redfern, and future regional site administrator, Bethany Groff Dorau, revived the Reading Club. One of the first to join was Doris Noyes, granddaughter-in-law of original

Reading Club member Nancy Noyes. Soon after, Beth Welch, the granddaughter of the irascible Helen Hale Welch, signed up.

For the last nineteen years, like the original group, this incarnation of the Reading Club has been filled with laughter, friendship, and even the occasional “dust-up” as women (men are not excluded but females make up the group for now) from different generations and economic, professional, and political backgrounds meet to discuss books that range from the academically rigorous to the imaginative and literary. One big change: the group meets monthly rather than weekly and has shifted from reading aloud to reading individually and gathering to discuss. Books are about New England or by New England authors,

top left Reading Club founding member Eleanor (Little) Baker (1886-1983), in the dark uniform. above Eliza Adams Little (1861-1954). center top Amelia Worth Little (1892-1986). center bottom Agnes Lawrence Little (18961982). bottom left Margaret Bradley Little (1888-1967). Amelia, Agnes, and Margaret were Eliza’s nieces and the last generation of the family to live at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm.

and fiction, nonfiction, short stories, and books from 1919 are read in rotation. The books are recorded by one member and rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with the only criterion being each individual’s subjective assessment of the book in terms of interest, literary quality, and relevance.

The Reading Club spent its centennial year in rigorous study, researching the lives of its original members in archives and libraries and through the memories of their families. Doris Noyes represented the group at the closing ceremony of the 2019 Newburyport Literary Festival, as representatives of book clubs across the world shared their experiences. In September, the century was crowned with a party at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm for

current and past members and their families, featuring food and drinks from Little family menus and recipes. The occasion was also recognized with citations from the governor, the Legislature, and the Town of Newbury. Though a century is certainly significant, Eleanor Little Baker, ever the poet, envisioned an eternal meeting in her fortieth anniversary letter to the group: On Mondays up in heaven, we Shall still continue our R. C. Indeed, now in its 101st year, the R. C. continues. On March 25, amid the social distancing public health practice instituted to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, nine Reading Club members held their first virtual meeting. The book for the month was Olive, Again by Elizabeth Strout, a novel set in Maine.

Six years before Walter Gropius built his famed modern residence in Lincoln, Massachusetts, Boston-based architect Eleanor Raymond (1887-1989) had already brought the sleek look of twentieth-century living to several houses she designed in suburban Boston. One of the most notable was the International Style residence Raymond built for her sister, Rachel, in Belmont in 1931. Raymond’s inspiration came from Gropius’s Bauhaus design school in Weimar, Germany, which she had visited in 1930.

Before taking that trip, however, Raymond had been designing homes that incorporated the old and the

new, offering an architectural mashup of traditional New England building features and contemporary European ideas. Several of her projects combine Colonial Revival and the International Style, introducing regional modernism to New England.

Raymond is also known for the Dover Sun House (1948) in Dover, Massachusetts, the first residence ever to use solar radiation as its source of energy. Raymond and Massachusetts Institute of Technology engineer Maria Telkes collaborated on this early sustainable design experiment. Amelia Peabody, a sculptor who was a client of Raymond, provided the funding. Despite its historic

significance, the Dover Sun House was demolished in about 2010. Several other works by Raymond suffered that fate, too, despite protests by preservationists.

The photographs here are from the Eleanor Raymond Photographic Collection, which James E. (Jack) Robinson, an architect who specialized in campus planning, bequeathed to Historic New England. Raymond and Robinson shared a studio at 100 Memorial Drive in Cambridge, Massachusetts; she gave him her personal collection of photographs documenting her work from 1919-1940. Robinson also bequeathed his architectural library to Historic New England.

–Dorothy A. Clark, Editor

First called “The Art Society of Wellesley College,” Tau Zeta Epsilon was established to further the scholarly study of arts. Raymond, a 1909 Wellesley graduate, was one of three alumnae who developed the plans. The other two were Helen Baxter Perrin and Esther Parsons, both members of the class of 1923. Arthur Shurcliff, a consulting landscape architect, reviewed the site and plans. An English cottage that recalls the architectural tradition of the rural Cotswolds region in south central England, the house features

slate shingles and brick exterior walls.

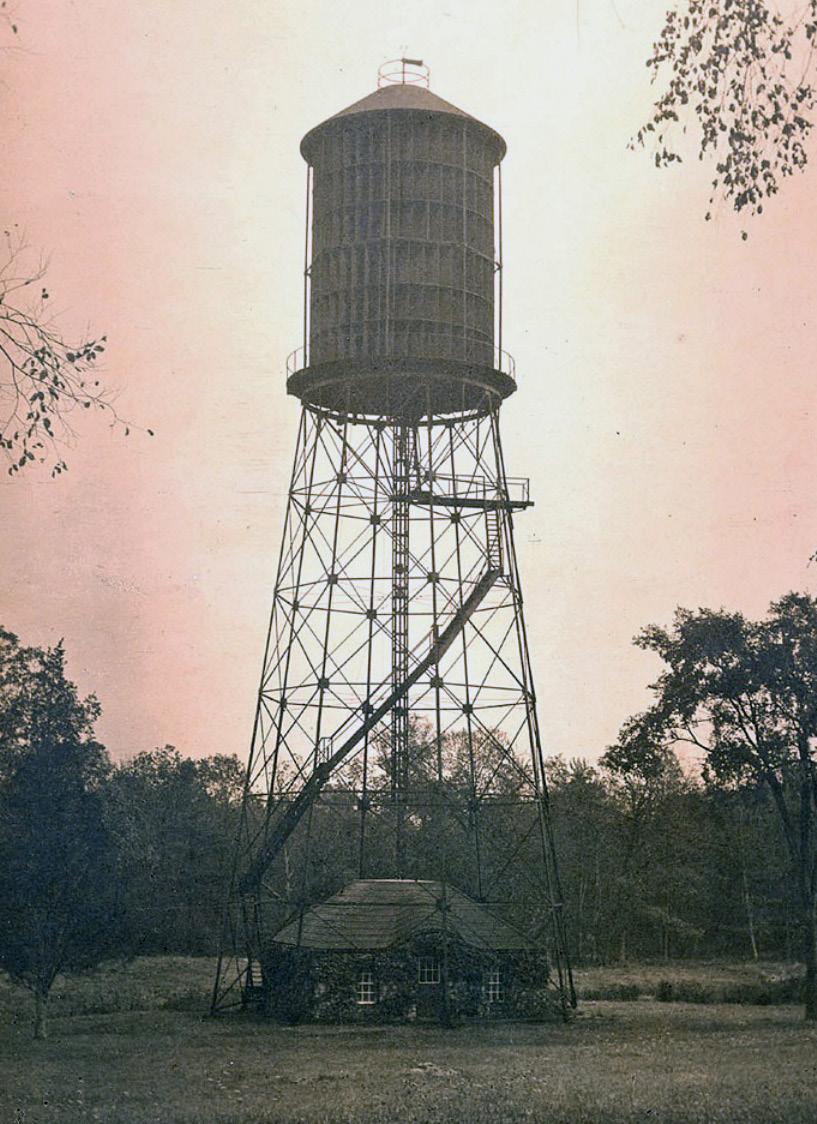

Next to the ice pond at the Eustis Estate in Milton, Massachusetts, is a building that seems as if it was transported from a fairy tale. The cottage-like structure of colored stone catches the eye of many visitors, who then peer into the windows. Intrigued explorers take note of the date—1902—inscribed in stones across the facade. It is almost impossible not to wonder what purpose this lodge-like edifice served. Astonishingly, it once housed a technological marvel that powered this grand estate.

W. E. C. Eustis, a Harvard-trained metallurgical engineer, wanted his estate in the countryside south of Boston to have the most advanced technologies available. The house had gas lighting when it was built in 1878, which was unusual for a home so far from the center of the city. Eustis’s interest in technology kept pace with the rapid advancements

in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the house was updated accordingly.

Electric lighting was one of the wonders of the Gilded Age, a time of major industrialization and economic growth in the United States that lasted from about the end of the Civil War (1865) to the beginning of World War I (1914). Thomas Edison invented the incandescent light bulb in 1879; by 1882, he had formed the Edison Electric Illuminating Company, which opened the first electric power station in New York City to provide service to a handful of wealthy clients.

These innovations paved the way for efficiently delivering electricity in major cities across the country and it rapidly moved from an exciting novelty to an essential part of daily life. That was not the case for rural areas, however, where hooking into an electrical grid wasn’t always an option. But this did not deter Eustis.

In about 1894 he installed what the trade publication The Electrical World called a “windmill lighting plant” on the property, noting that it was “the second largest installation of this character in America.” Technically, it was a wind turbine, though most historical sources refer to it as a windmill. The difference is that windmills transform wind energy directly into mechanical energy for immediate use, such as pumping water. Wind turbines change the wind’s energy into electricity to be used to power electrical equipment. It can also be stored in batteries or transmitted over power lines.

Many visitors to the Eustis Estate are surprised to learn of the windmill, thinking of those power generators as a more modern alternative energy source. Where would W. E. C. Eustis have gotten this idea?

Windmills have generated power for centuries to pump water or mill

grain, as their name implies. The first windmill for generating electricity didn’t come on the scene until 1887, when Professor James Blythe built one to power his home in Glasgow, Scotland. By the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, there were enough competing companies to set up a display of dozens of windmills whirling away on the fairgrounds. Quickly, their popularity spread across the American landscape and an estimated six million windmills were installed on farms in the last decade of the nineteenth century.

By 1902, Eustis was ready to upgrade his system, designing a new stone powerhouse and an even larger wind turbine to tower over it. He worked with landscape engineer Ernest Bowditch (who designed the grounds of the estate) to create a pump system to use this wind power to move water around the estate and farm.

Manning Johnson worked as the landscape gardener on the estate from 1904 to 1917 and was responsible for the wind-driven power generator. His son Paul described this in his memoir, One Man’s Story: “I was very interested in watching Dad’s work in the windmill. He would check it twice a day to change instrument charts and to see that everything was working fine. The mill would pump water and charge the batteries in the basement of the big house. At one time, it supplied the electricity needed for all purposes.”

In the historic photographs, the cylindrical turbine dwarfs the stone building and appears at first glance to be a water tower. Yet this unusual design is not a solid barrel as it seems, but contained slats all the way around that let in wind from every direction. This highly efficient

exterior concealed the wooden blades inside that rotated within the frame and turned a shaft that extended down into the powerhouse building below.

Inside the building was the generator, though little remains but the imprints on the floor. This most likely operated using direct current and the electricity ran out of the building through overhead wires to the mansion. There, in the basement, rows and rows of glass jar batteries were charged to power the house whenever needed. These huge jars weighed about thirty pounds each and were filled with zinc and acid with anodes sitting in the fluid.

The wind at the top of the hill in Milton certainly was a plentiful resource, though Johnson’s memoir mentions another detail that could explain the choice to stick with a windmill. “The wind would usually handle the generating of electricity and the pumping of water, but in calm weather, Dad would start the

huge gas engine to supplement the wind. It would fire once a second and exhaust outside the building. The engine could be heard half a mile away.”

The windmill helped preserve the idyllic calm of the landscape at the base of the Blue Hills until the estate could be connected with municipal electric utilities in the 1920s. According to the family, it was still in operation after that and powering Eustis’s library until his death in 1932. He apparently considered his system more reliable than the electric company. By sheer coincidence, the windmill was dismantled shortly before the Hurricane of 1938 and the equipment inside the powerhouse was removed about twenty years ago.

page 28 W. E. C. Eustis designed this wind turbine (alternately called a windmill) and powerhouse and had it installed on the grounds of his estate in Milton, Massachusetts, in 1902. below Eustis in his automobile in front of the mansion with the wind turbine towering in the distance.

Historic New England’s Community Preservation Grant, awarded in 2016, was a huge impetus in helping to raise the necessary funds to complete the first phase in restoring the 1937 Root District Schoolhouse in Norwich, Vermont. A “Standard School” built according to the specifications of the Vermont Department of Education, the building served students until 1945. In 1952, the Root District Game Club became the owner and steward of the property. By 2011, the club could no longer offer the schoolhouse as a community gathering place because of its deteriorating foundation.

Thanks to grants from Historic New England, the Jack and Dorothy Byrne Foundation, and the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation as well as vigorous fundraising by the Root District Game Club, now a 501(c)3 organization, funding was cobbled together for a new foundation for the historic building.

It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2013.

Last summer, the schoolhouse was jacked up off its crumbling foundation and supported on cribbing while the site was excavated and concrete was poured. The schoolhouse was placed back down on a new solid concrete base with greatly enhanced drainage to prevent future foundation issues. The finishing touches, including the porch and basement door, were completed in early fall 2019.

In order to acquire an occupancy permit, the Root District Game Club is working to complete several essential projects required by the state, including an access ramp, an accessible parking space, a new electrical system, and fire protection. Once these projects are completed, the building will be open to the community on a seasonal basis. Future projects such as window restoration, driveway and parking improvements, bathroom renovations, and heating installation will come in a third phase and are dependent on continued support from donors.

In addition to restoring the building for community use, the Root District Game Club works with partners to preserve the memories of Norwich’s schoolhouses. In 2019, the Norwich Historical Society compiled an exhibition on Norwich’s one-room schools, including

a hands-on schoolroom for visitors to try out the desks, write on slates, and look through old schoolbooks. In 2015, the Root District Game Club collaborated with Historic New England on a documentary about the history of Norwich’s oneroom schoolhouses. Ten students who attended Norwich one-room schoolhouses in the 1930s and 1940s were interviewed and dozens of historic photos were identified for use in the documentary titled Back to School: Lessons from Norwich’s One-Room Schoolhouses. The documentary is available at historicnewengland.org/explore/ everyones-history.

—Patricia Spellman Root District Game ClubCommunity Preservation Grants demonstrate Historic New England’s belief that collaboration among organizations devoted to preservation and cultural heritage will strengthen all efforts and raise the visibility and importance of preservation throughout the region. Endowed by the Herbert and Louise Whitney Fund for Preservation, the grant program supports conservation, preservation, restoration, education, research, public accessibility to collections, and exhibitions. Visit HistoricNewEngland.org/communitypreservation-grants for information about applying for a 2020 Community Preservation Grant.

In preparation for its 2021 national conference to be held in Plymouth, Massachusetts, the Vernacular Architecture Forum (VAF) sponsored dendrochronology testing last fall at several houses south of Boston, including a National Historic Landmark that is protected in Historic New England’s Preservation Easement Program. This technology could answer the question about the age of the privately owned General Benjamin Lincoln House in Hingham.

Dendrochronology is the study of the growth of tree rings. Also called tree-ring dating, it is the scientific method of using tree-ring growth to date and interpret the past. Dendrochronology is used in climate studies, archaeology, and other disciplines to determine the age of materials and artifacts made of wood.

Some sections of the Lincoln House reportedly date to the 1630s, which means it could be one of the oldest wood frame structures in the United States. The house was the birthplace and principal residence of Benjamin Lincoln (1733-1810), a Revolutionary War leader who attained the rank of major general in the Continental Army. Expanded in several stages during the eighteenth century, the Lincoln House is widely believed to still have seventeenthcentury materials.

Specialists tested floor joists in an area of the attic that appears to be part of the earliest section of the house. They also tested some hidden areas of framing with “waney edged” wood, sawn planks cut so close to the outside of the log that they lack a square edge and retain some bark. The findings will be presented at next year’s national conference.

The VAF, which is based in Annapolis, Maryland, takes a multidisciplinary approach to the study and preservation of vernacular, or ordinary, buildings, from traditional domestic and agricultural buildings to twentieth-century suburban houses.

Documentary films in Historic New England’s Everyone’s History series are available for free viewing on our website. The series consists of shortform movies, made in partnership with local organizations, that present slices of community life in the region during the twentieth century. Visit historicnewengland.org/explore/ everyones-history to watch the titles listed below.

Rooted: Cultivating Community in the Vermont Grange explores the social, economic, political, and agricultural influence of the National Grange on Vermont’s rural communities for more than a century and a half.

We Are Haverhill: Changing Faces of Haverhill’s Neighborhoods looks at the changing demographics of Haverhill, Massachusetts, with an emphasis on the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Woolworth’s: Remembering Haverhill’s Shopping District also focuses on Haverhill and tells the story of Woolworth’s five-and-dime variety store as well as other former downtown shops.

The Haymarket Project depicts the centuries-old history of Boston’s open-air market and the wideranging cross-section of cultures that converge there.

Back to School: Lessons from Norwich’s One-Room Schoolhouses explores the effort to preserve two remaining schoolhouses in Norwich, Vermont, featuring the last generation of students to attend these institutions.