By the time this issue arrives in your mailbox, the third annual Historic New England Summit will be just around the corner on November 14 and 15. Launched in 2022, the Summit brings together leaders in historic preservation, architecture, urban planning, conservation, arts and culture, public history, education—and so much more—for conversations about how current challenges and opportunities are shaping these fields. And this year, we couldn’t be more excited to be in the beautiful city of Portland, Maine, to host this two-day convening.

As the Summit has moved around the region—first hosted in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 2022 and Providence, Rhode Island, last year—the scope of these conversations has become stronger and more diverse. As we head to Maine this year, the character and pride-of-place found there echoes the vibrant voices and unique stories in this issue. Turn the following pages to learn more about the history of Pierce House in Dorchester, Massachusetts, and its role as a revitalized and thriving center for student learning. Hear how the League of Women for Community Service has adapted over the years to support and amplify the voices of Boston’s Black community. Take heart in the future of preservation through the eyes and enthusiasm of a new generation of leaders now emerging in the field. Get to know Ona Judge, who was born enslaved and escaped to freedom in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, through a contemporary artist’s portrait of this remarkable woman. And even learn about the tradition of craft distilling in Maine. There is much to discover and celebrate across this amazing region.

We continue to be energized and grateful for your support of the work and mission of Historic New England, and for the incredible contributions you each make to strengthen this place we call home. Please consider joining us for the Summit this year in Portland, and see what is in store for the future.

With gratitude,

Vin Cipolla President & CEO

HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership. To become a member, visit HistoricNewEngland.org or call (617) 227-3956. Comments? Email Magazine@HistoricNewEngland.org. Historic New England is funded in part by Mass Cultural Council.

President and CEO: Vin Cipolla Creative Director: Laura Sullivan Editor: Tracy Neumann

Associate Editor: Lorna Condon Editorial Board: Genevieve Burgett, Alissa Butler, Peter Gittleman, Erica Lome, and Jennifer Robinson Design: Julie Kelly Design

Cover Eastland Hotel, Portland, ca. 1940. Collections of Maine Historical Society/MaineToday Media.

As longtime members know, Historic New England began in 1910 as the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities— ours is the oldest and largest regional historic preservation organization in the United States. Over the past century, we’ve expanded our work beyond our beloved house museums and brick-andmortar preservation concerns. We hold the largest collection of New England artifacts in the world, and our archival collections are a vital resource for understanding life in New England from the seventeenth century to the present day. In Haverhill, Massachusetts, we're exploring new directions in community-based, sustainable development in legacy cities. Climate action and carbon neutrality are now central to our mission.

In short, preservation is evolving, and so are we. In 2022, in recognition of preservation’s new era, we held the inaugural Historic New England Summit to bring

together diverse voices from preservation and related fields. This annual event is now a highlight on our calendar, offering two days of engaging conversations about how modern challenges and opportunities are shaping our work in historic preservation, architecture, urban planning, conservation, arts and culture, museum studies, collections management, public history, and education.

This year’s Summit features keynote speakers from around the country, panel discussions, provocations, and opportunities to connect with others with similar interests. We invite you to join us on November 14 and 15 at the historic Westin Portland Harborview hotel in Portland, Maine, or tune in via Livestream from the comfort of your home or office. And read on to learn from three Maine-based Historic New England staff members why the Pine Tree State is an ideal location to hold conversations about creating livable places.

VICTORIA STANTON

Institutional Giving O cer

Lewiston, Maine

If you want to save the world, you might consider starting in Maine.

Maine’s small cities like Portland and, farther north on the I-95 corridor, Lewiston and Bangor, are auspicious places to test a variety of social and economic initiatives, models that can eventually be scaled for large populations.

ese communities have all the challenges and opportunities of larger cities, with a deeply interconnected and robust network of service providers, nonpro ts, and advocacy groups on the ground.

Already many funders are turning their attention to Maine’s coastal communities as bellwethers of climate change. Our cities continue to rally and respond to the arrival of immigrants and refugees from various African and Middle Eastern countries, which impacts the demographic and cultural landscape. Like many places in New England, a lack of a ordable housing has intensi ed homelessness and strained the constellation of support services. e rise of fentanyl is destroying the lives of many urban and rural Mainers alike.

At the same time, Maine is forward-looking and engaged. We have been quietly on the leading edge of emerging policy issues, from climate and conservation to marriage equality and ranked-choice voting. Our leaders in Augusta and Washington, D.C., are accessible and present in the community. (Don’t be surprised when you bump into your local legislator at the neighborhood barbecue.) Maine-based foundations are elevating entire communities through philanthropic investment.

It is tting that Maine’s state motto, Dirigo, translates from the Latin to “I lead.” For the philanthropic sector, Maine is a place to do just that.

JOIE GRANDBOIS

Sustainability Coordinator

Biddeford, Maine

The phrase “As Maine goes, so goes the nation” once referred to Maine’s state elections predicting the outcome of presidential contests, but today it is more applicable to sustainability and climate action planning. Maine has faced several climate-related challenges in the past few years with increased storm and flooding damage. One of Maine's most well-known industries, fishing, also faces difficulties due to the warming of the Gulf of Maine and its impact on the lobster fishery.

Maine didn’t adopt its climate action plan, Maine Won’t Wait, until 2019, but the state has already made great progress in achieving its climate goals. The latest progress report shows a 25 percent reduction in emissions and Maine met its goal of installing 100,000 heat pumps two years ahead of schedule. The state still has a way to go to meet some of its more ambitious 2030 goals, such as conserving 30 percent of Maine land and adding an additional 219,000 electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles (the 2024 update showed an increase of just over 12,000).

At the local level, 174 communities across the state participate in the Community Resilience Partnership program and have embarked on their own climate resilience planning. The City of Portland and neighboring South Portland, for example, jointly developed their One Climate Future plan to reduce their communities’ contributions to climate change and strengthen their ability to respond to climate hazards. With such progressive planning in place, Maine is well on its way to a more sustainable future.

KELLY WASSON Director of Human Resources

Gardiner, Maine

One of the things I appreciate most as both an HR professional and lifelong Mainer is seeing firsthand the quality of life gained from living in a place that combines the ability to pursue your professional goals while nurturing your community and savoring all that the culture around you has to offer. It’s a balance that is tough to match, and one that comes at an increasing cost. Maine has a shortage of workers, a challenge that can’t be remedied without affordable housing options. While Portland and surrounding communities have long led the charge in recognizing the critical role diversity plays in our economic and social futures, limited workforce housing options bring an added threat to Maine’s vulnerable heritage industries. As various initiatives work to address these issues, more Mainers are looking beyond their geographic confines toward remote work opportunities, offering better pay and more upward mobility to workers living in rural communities. The changing landscape of how we work has brought relocated Mainers home and equipped us with a better ability to welcome new Mainers through access to an expanding array of remote and hybrid employment opportunities.

Through technology and ingenuity, the move to Maine is within better reach. And as a “kid from Maine”—a New England state not traditionally known for having a competitive edge in the talent marketplace— that is something transformative.

Critique of Prohibition postcard, ca. 1930. Collections of Maine Historical Society.

There cannot be good living where there is not good drinking – Benjamin Franklin

Life's Good Here – Portland, Maine, city motto

by DR ALISSA BUTLER Study Center Manager

Portland, Maine, is home to seven cra distilleries producing an array of locally cra ed spirits ranging from gin, rum, and vodka to whiskey, bourbon, and brandy. ese distilleries—Batson River Brewing & Distilling, Hardshore Distilling, Liquid Riot Bottling Co., Maine Cra Distilling, Sweetgrass Winery and Distillery, New England Distilling Co., and ree of Strong Spirits—are part of the twenty-member Maine Distillers Guild. ey not only produce spirits in Maine;

they do so using locally sourced ingredients, including malted barley, blueberries, apples, rye, buckwheat, potatoes, horseradish, pears, cranberries, herbs, botanicals, and maple syrup. Some even locally source Maine-made white oak barrels.

Historically, Maine primarily distilled rum, but the state’s residents enjoyed all kinds of alcohol, frequently. Between 1720 and 1820, the annual per capita consumption of alcohol rose from two gallons per person to ve. e fear of contaminated water,

along with the belief that alcoholic beverages were bene cial for health, contributed to their widespread consumption. Children were o en given rum to drink in the mornings “for their health,” and employers gave their laborers rum and beer to drink on the job and during their breaks. Even the Puritans drank in moderation. Age, sex, class, and race may not have limited alcohol consumption in the home or workplace, but in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, local governments controlled who could own taverns and who could imbibe in them. Typically, taverns admitted White men to drink alcohol socially. Municipalities granted tavern operating licenses to applicants “of good repute,” and so it was most o en White male merchants, doctors, and lawyers who received them. Some taverns and inns were owned and operated by widows, as it was one of the few socially acceptable ways they could earn a living. Historic New England’s Gedney House in Salem, Massachusetts, operated by widow Mary Gedney, is one such example.

In the early nineteenth century, Maine became a nexus for prohibition due to the e orts of Neal Dow, the "Father of Prohibition." As Portland’s mayor, Dow

championed the Maine Law of 1851, which prohibited the production and sale of alcohol more than sixty- ve years before the Eighteenth Amendment. e law included a clause allowing alcohol for medical purposes, which led to the Portland Rum Riot of 1855 when Dow's oversight of medicinal alcohol storage incited public outrage. Furious at his perceived hypocrisy, a crowd of somewhere between 1,000 to 3,000 people gathered to demand Dow's arrest and a search of the storage site. When the crowd became violent, Dow ordered the militia to re on his constituents, killing one man and wounding seven others.

A er the national repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the gradual elimination of Maine’s pre-Prohibition restrictions enabled alcohol production to resume in the state. Brewing and winemaking outpaced distilling, though, and the state’s rst distillery a er Prohibition wasn’t opened until 2003.

While still a comparatively young industry, contemporary distilling has thrived in Portland and in Maine. Spirits and cocktails are viewed as a cra . Many members of Maine Distillers Guild have opened their own bars and restaurants to share the (liquid) fruits of their labor. ey o er tastings, classes, and bespoke cocktails catering to the wide varieties of tastes and desired experiences of their customers. It seems that a er eighty years of prohibition and another seventy without a local distillery, Maine has enthusiastically embraced the cra . And Portland, once the heart of prohibition, has now become a hub for spirit enthusiasts.

T Confiscated liquor bottles, Portland, 1927. Collections of Maine Historical Society. L Grab a bottle of gin—try one from Maine or a local distillery—and make author Alissa Butler's favorite cocktail, named after her dog, Jim, who often mistakes the work "gin" for his name.

Built by the Minot family in 1683 and purchased by Thomas Pierce in 1696, Pierce House remained in the Pierce family for ten generations, until Historic New England purchased it in 1968. Historic New England later acquired many of the Pierce family papers, including an account book and a journal kept by Colonel Samuel Pierce in the 1700s.

Pierce’s journal and account book were the keys to transforming Pierce House from a sleepy house museum into a vibrant center for student learning. Pierce was “a regular guy”—a middle-class farmer, not a politician or general or

by CAROLIN COLLINS, Education Program Manager, and KATE HOOPER, Education Program Coordinator, Pierce House

wealthy merchant. His journal entries offer an eyewitness account of how events such as the Boston Tea Party and the Battles of Lexington and Concord were perceived by those living nearby and how the unrest and eventual war interrupted and shaped daily life. His account book records some of the ways he interacted with other area farmers and skilled tradespeople, bartering farm products, such as cider and meat, for manufactured goods, such as shoes and tools. We worked with classroom teachers to turn the information from these primary source documents into programs for elementary school students that are exciting, hands on, and grounded in history.

However, Pierce’s papers do not allow us to tell the full story of the community. Women are underrepresented in our programs, and free and enslaved Black and Indigenous people do not appear at all. By presenting a Dorchester where everyone is presumed to be White, we are leaving out vital parts of the community’s history and points of connection for students.

Most of the students who visit Pierce House for school programs attend Boston Public Schools, where approximately 15 percent of students are White and 70 percent are classified as low income by the Department of Education. We make programs economically accessible by providing bus transportation and free or reduced admission; we are working to make the first floor of Pierce House fully physically accessible; and our programs are, by design, interesting and engaging for students of different learning styles and abilities. Yet, our education program’s reliance on Pierce’s papers meant that these exceptionally diverse students were learning about a narrower set of experiences than we wanted to present.

In 2023, as part of Historic New England’s Recovering New England’s Voices initiative, we received an Expanding Massachusetts Stories grant from Mass

By presenting a Dorchester where everyone is presumed to be White, we are leaving out vital parts of the community’s history and points of connection for students.

Humanities. The grant enabled us to hire Dr. Paula Austin, Associate Professor of History and African American and Black Diaspora Studies at Boston University, to expand research into the Pierce family and surrounding community in Dorchester, looking specifically for information about enslaved and free Black residents from the time the house was built through the eighteenth century. Austin conducted research in Historic New England’s Pierce Family Papers and related collections held by the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The records of the First Parish Church of Dorchester proved to be a particularly rich primary source. For a time, Samuel Pierce recorded the births and deaths of the parish. In keeping with the custom of the time, White residents were referred to without any racial markers (“January 6 Died An Enfant Child of Mr. Philip Withington”), whereas Black and Indigenous people were marked as such (“November 16 Died A Negro Man of Mrs. Primer named Cato”). By cross-referencing the names in this document with Pierce’s journal and account book, we see a fuller picture of life in colonial Dorchester.

Thomas Pierce was sixty-one years old when he purchased Pierce House and twenty acres of land. His age suggests he would have needed help farming, but we do not know whether he used hired hands, indentured servants, or enslaved people for farm labor. We do know that the Pierces’ neighbors owned slaves. Through our research, we are also learning more about free Black people in the community, including a man named

This work has allowed us to broaden our lens and expand our stories while keeping everything grounded in meticulous research and documented fact. Over the next year, we will adapt our school programs to incorporate this new information. Simultaneously, we will continue trying to find out as much as we can about the free and enslaved Black and Indigenous people of colonial Dorchester and the ways their lives intersected with the lives of the Pierce family.

Ongoing research on Black and Indigenous history related to Pierce House is part of Historic New England’s Recovering New England’s Voices (RNEV) initiative.

Preservation Carpentry Supervisor Omri Nassau removes temporary panels in preparation for the reinstallation of the restored stained-glass window.

The Pink House’s Mod Window

by LAURIE MASCIANDARO, Site Manager, Roseland Cottage

Every self-respecting Gothic Revival-style house should have an imposing window that emphasizes its connection with medieval church architecture and demonstrates why the Gothic Revival was originally known as the “pointed style.” Certainly, the window in Roseland Cottage’s conservatory qualifies. It is a favorite feature of everyone who visits the house, but its significance goes beyond its beauty: We believe it to be one of the first domestic uses of stained glass produced in the United States.

When Manhattan businessman Henry Bowen returned to his native Woodstock, Connecticut, to build his summer home, he spared no expense. Bowen's design sensibilities may reflect a bit of showmanship—the local boy who made a fortune in the big city wanted to bring a taste of the wider world to his beloved hometown. He built Roseland Cottage in the latest style, which today seems extreme compared to the sedate houses that surround it.

Roseland Cottage’s stained-glass window is an example of the unusual aesthetic choices that make Historic New England’s “pink house” unique. The most notable and noticeable design feature is, of course, the exterior paint color. In 1887, The New York Times

referred to it as “a brilliant crushed strawberry.” The window, too, surprises many visitors. Its colors and design are not what they expect to see in a house built in 1846; it seems a bit on the “mod” side, more 1960s than 1840s. Some have suggested that a lava lamp on the desk would be an appropriate addition.

Because the window is such an integral feature of Roseland Cottage and an important part of American architectural history, we were extremely concerned when gaps developed between the leading and the glass, and when other damage that had been stable for years appeared to be worsening. In 2023, portions of the window were removed and painstakingly repaired, and in June 2024, the restored window was reinstalled.

by MICHAELA NEIRO, Objects Conservator

Stained-glass conservator Diane Russo, Historic New England Preservation Carpentry Supervisor Omri Nassau, and I investigated the window to determine the least intrusive way to remove and repair its damaged glass elements. We began conservation work by setting up scaffolding inside and out to access the stained-glass panels. Omri and I worked from the inside to find the screws holding in the window frames. The large screws were originally covered over with plaster and decorative grain painting to hide them. After revealing and

removing them, the two most badly damaged panes were lifted out and packed for travel to Diane's studio.

Working on the scaffolding, we repaired multiple small cracks in the remaining glass with a clear adhesive. In addition to brilliantly colored glass, the panes contain shaped pieces of glass with grisaille finish, which coats the surface of the clear glass to make it look gray. Usually, the grisaille layer faces the interior, to protect the more delicate surface finish from weather and abrasion. However, in Roseland Cottage’s conservatory window, the grisaille layer faces the exterior and displays significant fading and scratches. To treat this damage, and to ensure that the color and opacity of the tinted adhesive matched the glass, communication was critical between conservators working on both sides of the window.

In the studio, Diane removed the leaded glass panels from their wood frames. She then cleaned and repaired

scratches and breaks in the glass and the lead. The most complex aspect of the project was creating new cut glass pieces to replace badly broken ones, and then matching the translucency and color of the original grisaille. This brownish-gray surface treatment had to be applied to the new glass and then heated at a high temperature in a kiln to make it permanent. Heating the glass also alters the color, so Diane conducted many tests to confirm that the color and opacity matched the original glass from both inside and out.

Now stabilized, we hope this beautiful window lasts at least another 175 years.

Eager to see the restored stained-glass window in person? Roseland Cottage’s final house tours of the season are on October 26 & 27. You can stroll the grounds and take in an exterior view of the window year-round.

by SUSAN GODSHALL and JACK TRIPP

Susan Godshall is a retired lawyer who enjoyed a career in municipal administrative law with a focus on New Haven’s economic development. Jack Tripp is currently a student at Harvard Divinity School, with his studies focusing on the religious experience in literature.

It might be reassuring to know that despite its Historic New England prize-winning outcome, writing e Builder Book was an experience in learnas-you-go. It began with a curious observation: For most historic buildings, the architect gets credit, but the builder is unknown. Who were these builders and cra speople? We wanted to recognize the men (and one woman) overlooked in the written record, since they built many iconic structures still lining the streets of New Haven, Connecticut.

The Builder Book: Carpenters, Masons and Contractors in Historic New Haven won the 2023 Honor Prize at the Historic New England Book Prize Awards. Co-authors Susan Godshall and Jack Tripp share how they found information about the colorful cast of characters who built New Haven and whose stories are often absent from architectural histories—and tips for how to research builders in your town.

A similar project may lie under the surface in your town; our experience o ers a head start in nding it. e secret is that local history is waiting to be unearthed, with just a bit of perseverance.

e keys to unlocking this secret are libraries and community archives, the treasure chests of history. Without these resources, we could not have written e Builder Book. We relied on the deep collections of the New Haven Museum, the New Haven Free Public Library, and the Institute Library.

Community archives hold all kinds of publications.

For example, city directories stretching back to 1840 o er addresses and death dates. Most nineteenthcentury newspapers covered land purchases, property tax data, and commissions for new houses and shops.

Local historians wrote huge tomes lled with biographies of city residents, providing snapshots of thousands of citizens. We found one collection written by Edward Atwater, History of the City of New Haven to the Present Time (1887), and discovered that he was the

Published by New Haven Preservation Trust in 2022, The Builder Book documents the stories of the artisans and craftspeople who built New Haven. Image courtesy of Yale University: Photographs (RU 608), Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

son of Elihu Atwater, a mason we were researching. It soon became clear that many of these people knew (or were related to) each other, a surprise that repeated itself throughout the research.

Our favorite source at the New Haven Museum is a scrapbook collection of around 150 volumes compiled by Arnold Guyot Dana in the early twentieth century. Dana was a hobbyist with a fixation on the built environment, a gift to those interested in the street-by-street growth of New Haven. He organized these volumes by address and filled them with reams of newspaper clippings, photographs, pages from books, and other paraphernalia, now scanned for public use. We could find the Chapel Street volume, for instance, turn to the page on No. 1032, and see the original Gaius F. Warner House, designed by Henry Austin in 1860, showing its Italianate facade and ornate portico before a later addition gave it a four-story commercial face.

As we dug deeper, we learned that in addition to being skilled workers, the people we featured were creative artisans, often using their own plans and designs. They were respected in the community, took leadership positions, and frequently held appointed and elected office. Discovering this aspect of the builders’ lives— that they welcomed civic responsibility—was a bonus, illuminating history in a way that bricks and mortar alone did not.

It was only after finding all the dates, addresses, anecdotes, and bits and pieces about wives and families that we could begin to create a narrative, turning a thousand random facts into twenty-three interesting stories. To vary them, we juxtaposed the relatively famous (Sidney Mason Stone) and the unknown (Ettore Frattari), the ancestral New Englander and the Italian immigrant.

The story of one of our favorite builders brings these themes together. Atwater Treat (1801-1882) was easy to research. He appears in the compiled biographies and in the Dana scrapbook, and New Haveners commemorated him beautifully upon his death. Like others, he received a vocational education and began learning carpentry as an apprentice when he was seventeen. He contributed to both residential and commercial buildings, including the Exchange (1832)—the first fully commercial structure in New Haven.

But what interested us most had little to do with his building experience. Treat embodied the civic

“ Local history is waiting to be unearthed, with just a bit of perseverance.

engagement of the time. Later in life he became a religious leader, founded libraries, helped to save the New Haven hospital from bankruptcy, advocated for abolition, and supported Black education and su rage.

Treat’s biography shows the extent to which these carpenters and masons could also be community builders. His obituary talks about his buildings “bearing witness by their own symmetry and solidity, to the beauty and strength of character of him who built them.” His life demonstrates the intention builders brought to both their vocations and their lives in public service.

Read a digital edition of e Builder Book at www.issuu.com/nhpt.

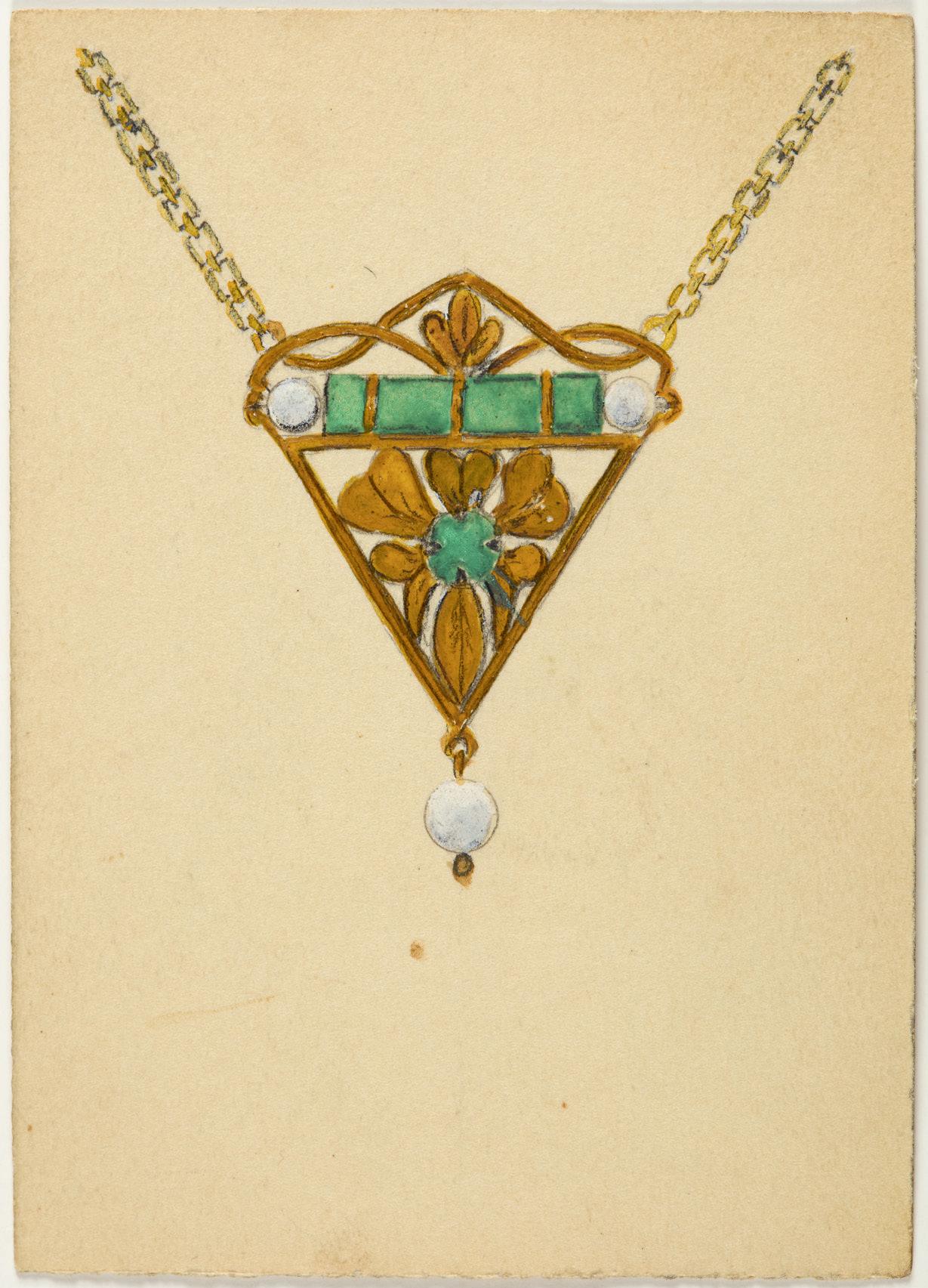

This fall, we installed a portrait of Ona Judge at Langdon House in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Judge will be familiar to those who have taken a tour of Langdon House as the "never caught" woman who was enslaved by George and Martha Washington and who selfemancipated by escaping to Portsmouth. Maine-based artist Maya Michaud created the portrait of Judge, drawing inspiration from Historic New England’s eighteenth-century costume collection and historical descriptions of Judge. We have already updated our Langdon House tours to talk about Cyrus Bruce, a formerly enslaved man who worked as the Langdons' majordomo, and other people who worked at the site. Michaud's portrait of Judge will facilitate a fuller interpretation of Portsmouth's Black history on our tours. This year, Study Center Research Fellow Timothy Hastings is conducting additional research on labor history in Portsmouth and at Langdon House to support ongoing changes to our site interpretation and further highlight contributions of those workers or community residents whose stories

Melissa Kershaw, Regional Site Administrator, Northern New England

Artist Statement

Maya Michaud | Maya Rose Artworks

Ona “Oney” Judge Staines was a courageous and resilient woman who sought to make her own destiny and pave the way toward her freedom. This portrait of Ona Judge, a former slave of George and Martha Washington, is a depiction of Ona in her twenties, following her escape to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where she was discovering her new way of life. This is my vision of her learning to take on the role of a free woman, where she develops a strong and confident stature while holding her head high. Her posture and ambiguous facial expression portray someone who has many secrets and stories yet to be revealed.

The composition and lighting are seen throughout eighteenth and nineteenth century portraiture and are qualities that I wanted to convey in Ona’s painting. This is an expression of her life as both a former slave and her ability to fight for her freedom whose image can live on in the history of New England. The color palette of Ona’s portrait conveys a sense of peace and calmness that Ona brought to the people around her, with the warm glow behind her to represent a sense of light and hope that is present within her story of resilience and bravery. This glow that resonates from her and is surrounded by darkness is symbolic of a candle in the night, which shows how Ona is lighting her own path and being her own guide to freedom.

Ona’s portrait was created with vibrant acrylic paints and various newspaper articles. There are no known images of Ona. Her story has been passed on and shared through newspapers, which emphasize the importance of the written word in this painting. The written word is a form of storytelling that can live on through the ages and emulates the idea that Ona has stories about her life that are told and untold. All of the newspapers were chosen deliberately to convey who Ona might have been during her life and the experiences that she might have gone through. I portrayed her in eighteenth-century attire that is of higher quality in structure and design, but which has a worn-in appearance to show her hardships as a working-class woman. The red in her shawl portrays the sense of strength and sacrifice that came with her escape, as well as the feeling of love and loss for her family who she left behind. She has an incredible story of bravery and hardship that is inspiring to anyone who hears it.

A Community Grant from the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation made this commission possible. To learn more about Maine-based artist Maya Michaud and view her portfolio, visit sites.google.com/view/mayaroseartworks.

Artist Maya Michaud

Kalimah Redd Knight is president of League of Women for Community Service, Inc. (LWCS) and Senior Deputy Director of Media Relations at Tufts University. Redd Knight and LWCS won a 2022 Historic New England Prize for Collecting Works on Paper for their collection documenting Black and women’s history, which includes letters, books, and documents from prominent civil rights leaders and organizations, along with LWCS's own records.

Tell us a bit more about yourself—your day job, your educational and professional background, and how you came to your role with League of Women for Community Service (LWCS).

Growing up in Roxbury/Dorchester, Massachusetts, I was instilled with a deep appreciation for Boston's Black community. My parents, both educators, chose to raise my sister and me here, connected to my father's roots. After attending Boston Latin School, I ventured south to Hampton University, a transformative experience at a Historically Black College. My career path led me from newspaper reporting (including The Boston Globe) to public relations in higher education. For the past eight years, I've been at Tufts University, promoting faculty research and community engagement initiatives, including those focused on American history. This passion for public history aligns perfectly with my volunteer work with the LWCS. In 2004, my great-aunt, a longtime member, introduced me to LWCS. I served on the board until 2013. I rejoined the organization in spring 2021, and just completed my first two-year term as president.

For more than one hundred years, LWCS has provided a safe space and resources for Boston’s Black residents. How have your services evolved over time?

From its founding, the LWCS has been a champion for the community. The organization tackled social and educational needs through a wide range of programs,

always adapting to the times. During the Depression, LWCS housed the Welfare Department and provided school lunches. In the mid-twentieth century, it became a haven for Black women students and women from the South seeking safe lodging. Many of these women were not welcomed in their colleges' dormitories and lived at the League’s building. While recent activities have focused on scholarships and food drives, the future holds much more. The LWCS is actively partnering with organizations to share its story and inspire a new generation of changemakers.

In the Summer 2023 issue of this magazine, you wrote about LWCS’s award-winning collection, its first president, Maria Baldwin, and your $5 million capital campaign to restore the historic brownstone that has been LWCS’s home since 1920. What are your plans for the building?

LWCS's building at 558 Massachusetts Avenue itself is a landmark, intertwined with the Suffrage and Civil Rights Movements. Sadly, a lack of major maintenance has taken its toll. However, a recent renaissance is underway! The LWCS has a revitalized board and ambitious plans. It has a renewed governance plan that will culminate in strengthened fundraising and programming. Once fully restored, the headquarters will become a vibrant community hub. Imagine a space buzzing with educational and cultural programs, community and corporate events, and speaker series—a place for dialogue and collaboration. It will also feature a house museum

and office space for educational/community endeavors, all in celebration of the rich heritage of Boston's Black community, offering opportunities for all to connect with this enduring legacy.

How is the restoration coming along?

We're thrilled to announce a huge step forward in our restoration—an approximately $711,000 grant from the City of Boston Community Preservation Act (CPA) program. This is our largest grant award to date. These funds will be directed toward restoring the building's rear facade and bow area, including the brickwork, window frames, and installation of restored windows. This exciting development builds on the ongoing Phase 1, led by Spencer Preservation Group. Phase 1 focuses on revitalizing the front entry, facade, roof, and historic windows.

Have there been any new developments with your collection?

The archive and library offer a unique perspective on American history, seen through the lens of Black women who tirelessly fought for civil rights for all. We recently partnered with Harvard's prestigious Schlesinger Library to conserve and digitize a truly remarkable piece—a commemorative book featuring the first-hand accounts of the Civil War of Black soldiers of the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Regiments and the 5th Massachusetts

Cavalry. Schlesinger is currently digitizing the entire book and working with the LWCS to make this piece of history accessible to a wider audience.

What’s next for LWCS?

We're celebrating our 110th birthday in just five years! To mark this milestone, we're planning a comeback to maximize our impact in the community. LWCS has a rich history as a volunteer-driven organization. Despite a lean structure, we've made a significant difference. Now, we're setting our sights on strengthening our internal operations to ensure even greater future success. In short, we're going beyond bricks and mortar to focus on building a stronger foundation for the future.

How might our members get involved with LWCS or support your work?

We are in the process of relaunching the LWCS affiliated “Friends of the League” in 2025 and would love to invite individuals who care about historic preservation and Boston’s rich history and want to support the revitalization of this important organization and its historic sites to consider becoming a member of the “Friends.” Feel free to email us at info@lwcsboston. org for consideration. Of course, donations are always welcome! They allow us to tackle important preservation projects and care for our collections. Lastly, we encourage folks to stay connected with LWCS. Follow us on social media through “X” and Instagram at @LWCSBoston or visit our website at LWCSBoston.org to learn about upcoming events and activities. There are many ways to get involved!

Read about LWCS’s award-winning collections in our Summer 2023 issue, available online at issuu.com/historicnewengland.

Members of League of Women for Community Service, Inc., accepted the 2022 Historic New England Prize for Collecting Works on Paper at our first Summit in Worcester, Massachusetts. L to R: Jacquelyne Arrington, Clerk; Kalimah Redd Knight, President; Vin Cipolla, President and CEO, Historic New England; Jacqueline S. DeJean, former board member; and Adrienne R. Benton, Treasurer. Photograph by Kevin Trimmer.

Historic Wαpánahkəyak, a visual arts exhibition featuring works by Panawáhpskewi artist Lokotah Sanborn, was on view at Sarah Orne Jewett House Museum and Visitor Center in South Berwick, Maine, this past summer. "Wαpánahkəyak" translates to "the Dawnland"—the regions of northern New England, Canada's Maritimes provinces, Newfoundland, and Quebec south of the Saint Lawrence River. These are the Wabanaki Confederacy's homelands, currently consisting of five principle Tribal Nations: Panawáhpskek, Peskotomuhkatiyik, Mi'kmaq, Wolastoqiyik, and Abenaki.

Sanborn recontextualizes historic photographs of Indigenous Peoples taken as part of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century salvage anthropology, when Euro-American anthropologists sought to document the "vanishing" races and cultures of Indigenous North Americans whose lifeways were threatened by assimilation policies enacted by the United States and Canadian governments. Sanborn honors the subjects in these photographs by reimagining their likenesses in digital collages to illustrate Wapánahki cultural continuity, epistemology, oral history, and spirituality.

by DANIKAH CHARTIER

Danikah Chartier (Mi'kmaw) is the co-curator, with Lokotah Sanborn, of Historic Wαpánahkəyak . In 2023-2024, she was the Northern Region Indigenous Community Liaison and Researcher for Recovering New England’s Voices .

His oeuvre includes pieces that depict histories present within the narratives of Historic New England’s museums, such as land theft across Wαpánahkəyak and the deforestation, pollution, and damming of waterways driven by industrialization. Artist statements and interpretive texts displayed throughout the gallery

and marginalization. Decolonization challenges dominant colonial narratives and a rms Indigenous Peoples' rights to self-determination over their lands, cultures, and political and economic systems. Many of these goals are also re ected in Historic New England's Recovering New England's Voices (RNEV) initiative. RNEV uses research, art, storytelling, and technology to create spaces that amplify historically underrepresented voices. rough this work, we unearth neglected or suppressed stories and incorporate them into our tours and programs. Historic Wαpánahkəyak is an extension of our RNEV work and our commitment to support healing from past harm in icted upon marginalized communities. Visit the digital exhibition at HistoricNewEngland.org/Sanborn.

To view Lokotah Sanborn’s portfolio, visit lokotahsanborn.com. The exhibition and related programming were made possible by the generous support of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation and the Maine Community Foundation.

by DEXTER VINCENT

Last summer, Dexter Vincent, then a rising senior at Classical High School in Providence, Rhode Island, completed an internship with Historic New England’s Preservation Services Team. We asked him to reflect on his experience as an emerging preservationist.

One day I realized that every home

I’ve inhabited has been historic. Of all seventeen—among them a 1795 captain’s house, apartments in Second Empire houses, and Colonial Revival homes—the newest was an apartment in a 1920 brick sixplex in Providence, Rhode Island. My parents sought these homes for their beauty and affordability, and they provided a colorful backdrop for my childhood.

Legos and old atlases inspired my love of history, architecture, and urban planning. As I gained new perspective, I found intrigue in details of these familiar

homes. I sought to solve a mystery: What caused the Providence I experience to differ so dramatically from that former one—invisible now, but revealed in maps and pictures? What factors produce society’s many challenges—most of all climate change? Books—namely James Howard Kunstler’s The Geography of Nowhere and Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities—answered some of my questions, and in a semester-long research project I investigated the history of planning in Providence. I saw the wasteful destruction of homes and communities that American cities and towns visited upon themselves and wondered how to preserve what’s left.

I brought these questions to Historic New England when I began an internship in the summer of 2023. I shadowed Senior Preservation Services Manager Dylan Peacock on annual visits to private properties protected by Historic New England’s Preservation Easement Program. The sites varied from storied Georgians to stylish suburban Victorians and a bespoke modern villa. Dylan attentively decoded every detail—the hydrology of the site, the quality of past renovations, the fine ornamentation and features. I also accompanied Jennifer Robinson, Preservation Services Manager, Southern New England, to a gorgeous Georgian in Matunuck, Rhode Island, and a seaside ice cream stand after.

From these visits, I learned much about diagnosing maintenance issues, writing condition reports, and scouring archives. But the crowning moment of the internship was our visit to Haverhill, Massachusetts. There, Historic New England is transforming the Burgess and Lang buildings into a world-class museum

Student Union (PSU) Leadership Team. PSU is a youth-led nonprofit which empowers students to better their schools and communities. As co-director, I’ve joined with youth, climate, transit, and labor advocates to petition for state appropriations to Rhode Island’s under-funded transit system, RIPTA. I have also worked with preservationists in Providence to counter my school district’s “Newer and Fewer” policy, which prescribes school demolitions and closures. In February 2024, I co-authored, with the PSU Leadership Team, an op-

ed in The Providence Journal arguing to save Mount Pleasant High School, one such building considered for demolition. In March, I wrote an article for The Providence Eye on the school district’s plans, which might now include near-total renovation of the building. Preserving old school buildings and funding transit may seem to be disparate endeavors, but I consider them to be the same. In both cases, I advocate for less resource consumption in order to fight climate change.

This fall, I am attending Brown University, where I will study every facet of cities. I hope to apply my experiences with Historic New England, PSU, and The Providence Eye to design cities that conserve our limited historic resources and contribute to a healthy, stable planet.

by LAUREN SALEMO

Lauren Salemo is a junior at Northeastern University, majoring in journalism and environmental science. She spent her 2024 co-op semester working with Historic New England’s Marketing Team.

The 250th anniversary of the American Revolution is drawing near, and our region’s cultural institutions are already preparing exhibitions, educational activities, and public programs for 2026. In 2016, Congress established the bipartisan U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission to coordinate national commemorative efforts, and most state governments have also convened commissions that will provide guidance and resources for their communities—including all six New England states. As states, cities, and towns prepare to commemorate their own histories, Historic New England plans to take a regional view with its New England 250 initiative.

In Massachusetts, the MA250 Commission is developing an approach that invites people to participate in and promote the stories of underrepresented groups, including women, Indigenous communities, and people of color. In Concord, Massachusetts, the Concord Museum will unveil their exhibitions next April, since Paul Revere took his midnight ride in 1775.

Rhode Islanders also plan to kick off their recognition of the 250th earlier than other states— Rhode Island was the first colony to renounce allegiance to England, signing the Act of Renunciation on May 4, 1776. The RI250 commission has established a subcommittee to provide a framework for school curricula that integrates the state’s colonial history with its diverse voices. With the Liberty Tree Project, RI250 and Rhode Island Historical Society are partnering to plant thirty-nine red maple trees, one

for each of the state’s municipalities.

Connecticut’s 250th commemorations center around tourism, public engagement, inclusive storytelling, and history and preservation education at historic sites. Connecticut has received a grant from the National Park Service for new interpretation related to the semiquincentennial at state-owned sites. At Henry Whit eld House in Guilford, for example, the commission plans to highlight a little-known story of the Indigenous woman who brokered the sale of the house. e grant also supports new interpretation at Veits’ Tavern in East Granby, where revolutionists convened. Calling attention to these “community spaces where people go and share ideas. . . and put that in today’s contemporary context,” Deputy State Historic Preservation O cer Cathy Labadia said, encourages the public to ask questions about freedom, civics, and government.

Vermont’s State Historic Preservation O cer Laura Trieschmann notes that even though her state was not a colony during the Revolution, its inhabitants still contributed to the war e ort. “Passion and patriotism didn’t stop at any border,” she said. Vermont’s semiquincentennial commission aims to have all 252 cities, towns, and villages sign a 250th resolution. e commission encourages ongoing thoughtful re ection, Trieschmann explained, “to make us better Vermonters, better New Englanders, neighbors, Americans.”

Maine and New Hampshire have also established semiquincentennial commissions; neither state has yet made their plans public.

Historic New England’s New England 250 plans involve developing a more inclusive history of the region’s inhabitants and their relationship to revolution. In September, the Study Center welcomed Recovering New England’s Voices Research Scholar Dr. David Naumac, who is documenting previously untold stories of New Englanders during and a er the Revolution. Curator Erica Lome is planning an exhibition, Myth and Memory: Stories of the Revolution, which will open in 2026. We are planning educational programs and events related to our sites and their communities, as well. e last time we had a national remembrance of the American Revolution was 1976, when bicentennial commemorations were meant to create a unifying moment following the divisiveness of the 1960s and the early 1970s. Steven Bellavia, an instructor at Emporia

State University in Emporia, Kansas, has extensively studied the bicentennial in the context of the Cold War. “It work[ed] really well for unifying and paving over cracks,” Bellavia said, because the bicentennial reinvigorated the Founding Fathers’ perception of American exceptionalism.

Today, however, Americans are more aware that, while the Revolution was a de ning moment for some groups, it was not a turning point for all. Across New England, commissions, organizations, and museums are recentering the narrative from well-known gures to everyday people, and “those stories really matter because that’s who we are,” Trieschmann said. “ e 250th should be what historic preservation is always about,” according to Labadia. “ at it is honoring the places of the past, preserving those places for future generations, looking at them through contemporary lenses, and informing or grounding who we are as individuals, as a community, and how we can move forward.”

This mural in a home in West Boxford, Massachusetts, is attributed to Rufus Porter. The scene includes many of Porter’s signature elements, such as a water scene and a tower-like structure on a hill. Photograph courtesy of Center for Painted Wall Preservation.

by MARGARET GAERTNER

Margaret Gaertner is a historic building consultant in Portland, Maine, who serves as the present Vice President of the Center for Painted Wall Preservation’s board and the Chair of CPWP’s Virtual Museum Committee.

The Center for Painted Wall Preservation (CPWP) was formed in 2016 to research, document, and preserve decoratively painted plaster walls and to raise awareness of this threatened vernacular art form. CPWP records stenciled, muraled, and freehand brush-painted plaster walls created between 1790 and 1860 throughout New England and in upstate New York.

New England’s early painted walls are vulnerable to destruction and loss. A frozen pipe, a leaking toilet, or vibrations from heavy trucks can be catastrophic. While some painted rooms are protected in museums, most are

privately owned and their futures are determined by the property owner.

For the past year, CPWP has been working to launch the Virtual Museum of Painted Walls. CPWP’s Virtual Museum, supported with a Dean F. Failey Grant from the Decorative Arts Trust, is a critical tool for bringing attention to and increasing appreciation of this rare and endangered art form, and for documenting these walls for future generations.

To initiate our Virtual Museum, CPWP’s board and advisors identified the best surviving examples and commissioned New York-based company Virtually Real

Solutions to create high-quality scans of the spaces. Each room was scanned using Matterport, a threedimensional image capture platform. The result is an immersive view of a historic interior that allows visitors to move freely through the rooms and to zoom in on various elements of the wall decoration. This format gives visitors the feeling of being in the space and enhances their understanding of the interior beyond what a still photograph can convey.

Visitors to the Virtual Museum can tour, study, and compare twenty examples of historic painted rooms in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and New York. While the noted muralists Rufus Porter;

his nephew, Jonathan D. Poor; and New Hampshire stencil artist Moses Eaton are represented in the Virtual Museum, visitors will also be able to view the works of lesser-known artists including Orison Wood, a Maine muralist whose surviving work is found near Auburn, and John Avery, whose works are concentrated near Deerfield, New Hampshire. Many rooms were not signed, and the works of anonymous artists are also included in the Virtual Museum.

While seeing painted walls in person is the best way to appreciate this art form, most of these walls are in private homes in remote locations. Open houses and tours are rare events, and prospective visitors need transportation, disposable income, and a flexible schedule to attend. Once there, stoops at the entry doors and steep and narrow interior stairs are barriers to those with limited mobility. The Virtual Museum allows all guests to view and learn about painted walls.

Historic New England awarded a Community Preservation Grant to the Center for Painted Wall Preservation in 2019. Visit CPWP’s Virtual Museum at www.pwpcenter.org/virtual-museum.

Bottom Left The only way to ensure the long-term preservation of painted walls in private homes like this one in Lyme, New Hampshire, is through preservation easements. Several homes protected through Historic New England’s Preservation Easement Program feature painted walls. Photograph by Carl Lindberg, courtesy of Center for Painted Wall Preservation. Bottom Right Moses Eaton's stencil kit is part of Historic New England’s collection.

Senior Curator of Library and Archives Lorna Condon and Curator Erica Lome share updates about recent acquisitions to Historic New England’s collections.

Sheepscott Community Church

Samuel M. Green (1910-1995)

Newcastle, Maine, 1974

Oil on board, 4’ x 5’

Gift of David Haake, 2023

Samuel M. Green (1910-1995) was an accomplished painter who attended Harvard University and taught art at Wesleyan University starting in 1948. While primarily known for his fine arts instruction, Green had a lifelong fascination with New England’s built environment and especially the architecture of Maine. During his youth, he made etchings of Maine homes and townscapes for the Works Progress Administration. He continued to document historic structures in his time as a professor using watercolor and oil paint. When he retired in 1974, Green made this painting of the Sheepscott Community Church (ca. 1868) in Newcastle, Maine. In Green’s simple yet arresting composition, the church appears frozen in time and larger than life. Devoid of human subjects, the eye is drawn instead to the stark beauty of the building itself, from the unique tripartite windows to the tall spire of the steeple that crests the tree line.

Historic New England has long collected paintings, photography, and other visual art documenting New England’s built environment. This painting particularly compliments our important acquisition of architectural photographer Steve Rosenthal's images of New England meetinghouses and churches.

by DAVID ACHENBACH, Lead Guide, Browne House

It’s a landmark year for Browne House in Watertown, Massachusetts—2024 marks its 100th anniversary as a museum. Built between 1694 and 1701, Browne House features rare surviving architectural elements from the late seventeenth century.

Browne House is important in the history of historic preservation for its role in the establishment of a “scientific” approach within what was at the time an emerging discipline. In a near ruinous state when Historic New England founder William Sumner Appleton acquired it in 1919, the house was painstakingly brought back to life in what is generally considered the first fully documented building restoration in the United States.

Preservationists may be familiar with Appleton’s restoration methodology, but the way he funded the emerging science of preservation is less well known. To pay the bills, Appleton rented out Historic New England properties for commercial and residential uses. And so it came to pass that Browne House, like several other Historic New England properties (most prominently, Swett-Ilsley House in Newbury, Massachusetts), operated as a tea room for several years.

houses, barns, and mills. Tea rooms were primarily women-owned businesses, often combined with gift shops or activities oriented to a female clientele, such as

fortune-telling or mahjong. In the 1910s and 1920s, in fact, women’s magazines frequently published articles explaining the economics of running a tea room.

We don’t know what drew Celestia Lapham and Susie Burnham to the trade, but both women served as museum curators and tea room hostesses at Browne House in the 1920s. In 1924—the year Browne House opened as a museum—the Watertown Sun reported that Lapham, who lived at Browne House with her widowed mother, planned to serve food downstairs with the upstairs “reserved for mah-jong and other fastidious festivities.” In 1927, The Boston Globe reported Burnham served “a lunch of dainty sandwiches, fruit cake and coffee” at a meeting of the Colonial Wars Society, “while a cozy glow was cast upon the scene by a crackling fire.”

Today, Browne House still operates as a museum, but guides wouldn’t dare risk lighting even a small fire in the enormous fireplace. And while you can’t get a sandwich, dainty or otherwise, you can see how an eighteenth-century farming family lived and learn about the evolution of the “science” of preservation.

Browne House is closed for the season, but we invite you to visit in 2025. To learn more about William Sumner Appleton’s scientific restoration techniques, read “The Abraham Browne House: A Preservation Icon” in our Winter 2005/Spring 2006 issue, available online at issuu.com/historicnewengland.

A Dinner in Support of the Historic New England Fund and the Annual Presentation of The Historic New England Medal Recognizing a Lifetime of Cultural and Preservation Philanthropy 2025 Recipients

F. Warren McFarlan

Anthony D. Pell

Save the Date

Sylvia Quarles Simmons

Past Historic New England Medal Recipients

Ann and Graham Gund & Kristin and Roger Servison – 2024

Janina A. Longtine MD & Peter S. Lynch – 2023

Lillie Johnson & Elizabeth “Biddy” Owens – 2022

Saturday, March 15, 2025 6:00 PM

Fairmont Copley Plaza Bo on, Massachusetts

As our major fundraising event of the year, we hope you will consider sponsoring or attending the Historic New England Medal Gala. For more information about the benefits of being a sponsor and for additional information, please visit HistoricNewEngland.org/Gala, call (617) 994-5934, or email Events@HistoricNewEngland.org.

In each issue, we ask a Historic New England staff member to share their unique perspective on history, preservation, and sandwiches.

A er Bruce Blanchard nished his BFA in Historic Preservation at Savannah College of Art and Design, he returned to his hometown, Newburyport, Massachusetts. He saw a job posting for a preservation carpenter on a local crew. Bruce had worked as a carpenter a er leaving the U.S. Air Force and before beginning his preservation program, so the job seemed like a good t. His rst assignment was working at Spencer-PeirceLittle Farm in Newbury in 1986; in 1993, Bruce joined Historic New England’s Property Care team. Historic New England’s philosophy of retaining as much historic fabric as possible and replacing materials in kind is, to Bruce, “true preservation.” If he’s not kayaking, camping, or exploring the Abruzzo region of Italy, you may run into Bruce around town when you visit our sites in South Berwick, Maine. Bruce retired from Historic New England in May a er thirty-eight years of service, but he can’t seem to quit us—he and his wife, Cynthia Mariano, recently moved into Eastman House, next door to Sarah Orne Jewett House. Read on to nd out what the self-proclaimed “Bauhaus fanatic” wishes he could take home from work and what he orders at Newburyport institution e Grog.

1. What’s your astrological sign?

Capricorn

2. Which Historic New England site would make the best setting for a reality TV show?

None of them!

3. If you could have one thing from our collection in your home, what would it be?

Gropius’s Bauhaus desk

4. If you were an architectural style, what would you be? Cra sman

5. What are your three favorite books? Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, You Can’t Go Home Again, e Prince of Tides

6. Coffee or tea? Co ee!

To

Bruce Blanchard, recently retired Facilities Technician, Piscataqua Region. Photograph by Nick Jones.

7. Hardwoods or carpet? Hardwood

8. Do you compost? Yes

9. If you could meet anybody, dead or alive, who would it be?

Richard Alpert

10. If you could buy a new property for Historic New England, what would it be?

A Cra sman bungalow

11. Define preservation in three words: “Keeping it real.”

12. What’s the best sandwich? Mushroom Swiss Burger

13. Which season is the best? Spring

151

by NORA ELLEN CARLESON Associate Curator of Collections

Elizabeth Pratt Stetson of Plainfield, Massachusetts, began the quilt shown here around 1860, but never finished it. Stetson died in 1863, leaving the entirety of the quilt backless and the means of its construction visible: small paper templates used to cut out and reinforce each piece of fabric.

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century quilters often used paper scraps as templates to cut individual fabric pieces. They would then sew together a selection of pieces to create what is called a block. From there, they sewed together multiple blocks to create a quilt. Finally, they applied a fabric backing that completely hid the paper within. Because of Stetson’s quilt’s visible paper templates, it is remarkable as a document that offers something finished quilts cannot—the remnants of everyday life in New England patched together to create a beautiful pattern.

This piece is exceptional due to the rarity of finding a quilt in this state and the information we can learn from transcribing its paper pieces. Looking closely at the paper templates, we can partially reconstruct individual documents. Some pieces show accounting for labor and goods. Other documents show someone practicing their penmanship. Yet others appear to be personal correspondence on topics ranging from someone’s death to purchasing goods.

Stetson’s descendants donated this quilt to Historic New England 160 years after she began it. We look forward to the research and educational opportunities this new acquisition offers.