7 minute read

Be My Guests

guests BE MY

Friends and celebrity revelers frequently came to call on A. Piatt Andrew at Red Roof, his home in Gloucester, Massachusetts

In the first guest book for his Gloucester, Massachusetts, home, Red Roof, noted economist and Bay State congressman A. Piatt Andrew (1873-1936) recorded his intention “to seize and hold, though it be ever so fragmentarily, suggestions of dear hours that pass.” Beginning this year, visitors to HistoricNewEngland. org may digitally “seize and hold” Andrew’s newly restored guest books themselves, thanks to the generosity of his great-great-niece by R. TRIPP EVANS Professor of the history of art and co-chair of the Department of Visual Art and History of Art at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts.

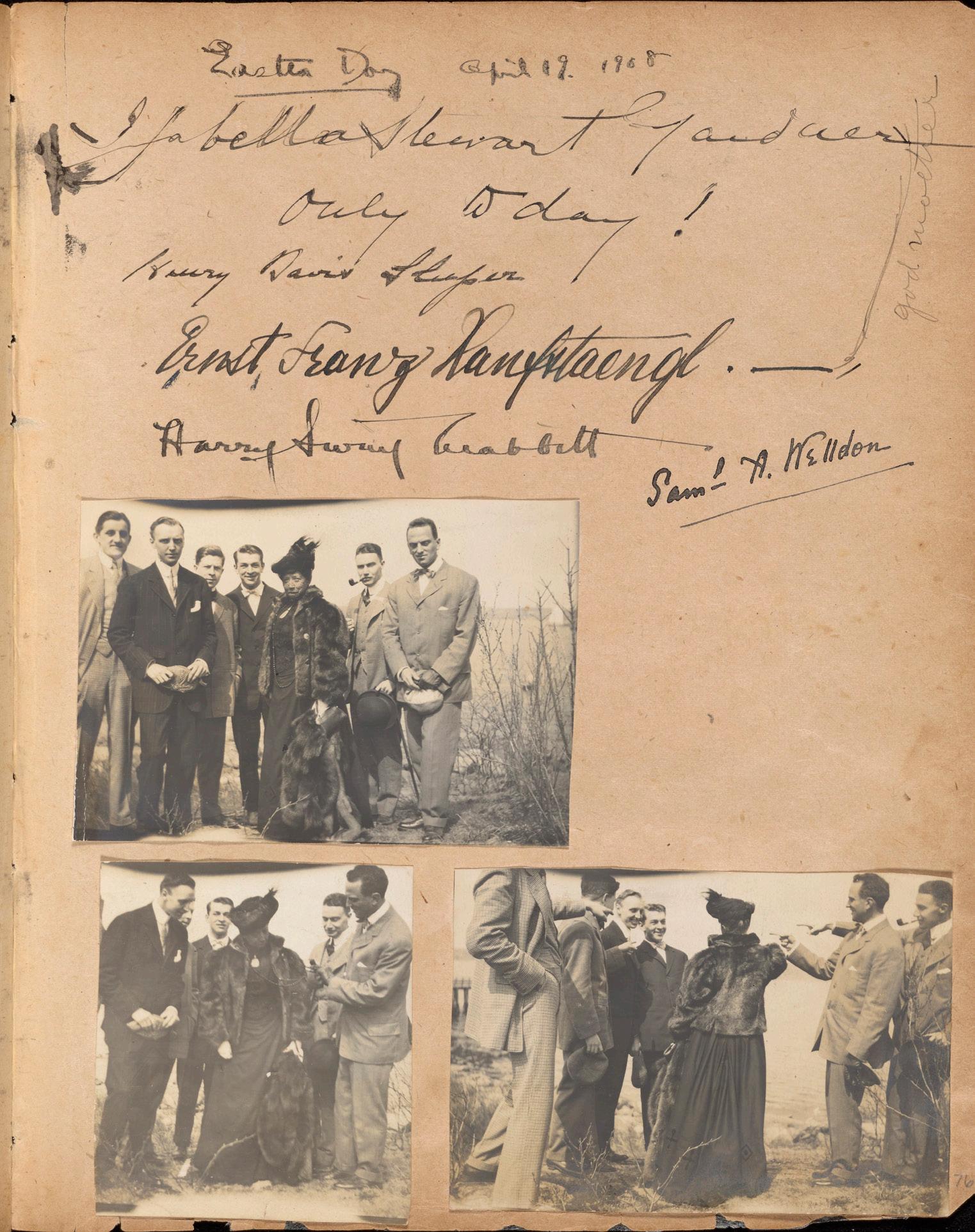

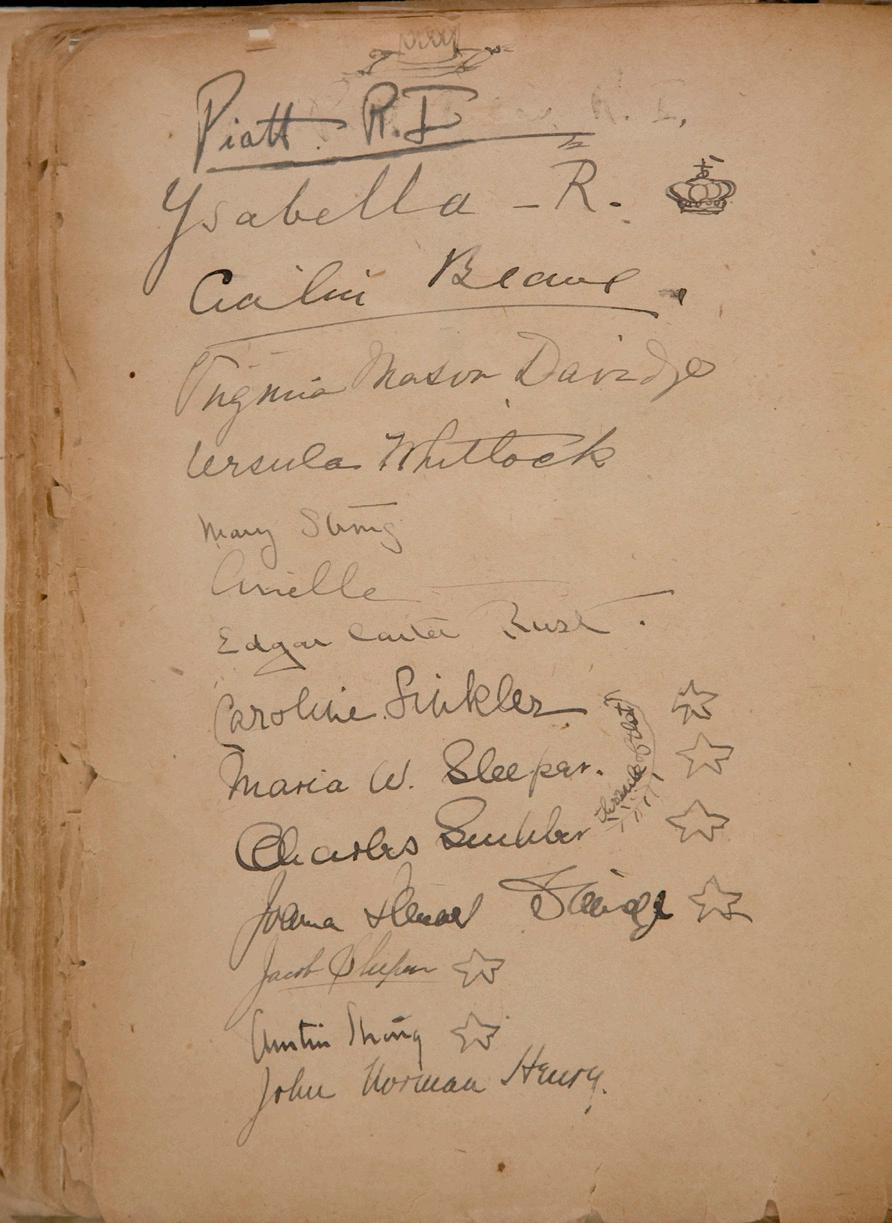

page 12 A. Piatt Andrew (far left) with four Harvard University students at Red Roof in May 1909: Joseph Husband (class of 1909), Crawford Burton (class of 1908), Candler Cobb (class of 1907), and Richard Eggleston Jr., class of 1909). right Easter Sunday at Red Roof, April 19, 1908. The notoriously camera-shy Isabella Stewart Gardner—a frequent presence at Red Roof—is at the center of an admiring circle that included Andrew and guests Henry Davis Sleeper, Ernst Hanfstaengl, Samuel Welldon, and brothers Harry and Jack Mabbett. below Signatures of guests at a farewell costume party for Andrew on July 30, 1908, before his departure for Europe with the National Monetary Commission. Painter Cecilia Beaux hosted the party at her Gloucester studio. Andrew, who attended dressed as a Roman emperor, styled himself “Piatt R. I.,” for “Romanorum Imperatorem”); Gardner signed as “Ysabella”; her nickname on Eastern Point was “Y.” She added an “R” (for “Regina,” or “Queen”) along with a small crown to her signature.

guests and -nephew, Corinna T. Fisk and her brother, Piatt A. Gray. The Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, Massachusetts, conserved and digitized the Red Roof guest books. Compiled in two volumes spanning 1902-1930, the guest books not only constitute an extraordinary record of the period—poring over the inscriptions and the nearly 700 photographs is like entering the world of an Edward Gorey cartoon—but they also invite us into the inner circle of a man whose charisma still fairly leaps off the page.

When the twenty-nine-year-old Andrew built Red Roof in 1902, he had recently joined Harvard University’s economics faculty. A sanctuary from his Cambridge, Massachusetts, faculty apartment, Red Roof anchored a growing colony on Gloucester’s Eastern Point that soon included Beauport, the home of Andrew’s great friend, Henry Davis Sleeper. More than a summer home, Red Roof became a year-round retreat for an impressive rotation of guests—a collection of personalities who clearly were as drawn to the man as they were to his extraordinary house. The attraction is not difficult to understand. Beyond Andrew’s considerable intellectual gifts, he was an impressive athlete, a connoisseur of the arts, an indefatigable host, and a man blessed with movie-star good looks. It’s reasonable to assume that invitations to Red Roof were rarely declined.

Andrew’s guest books sparkle with the names of

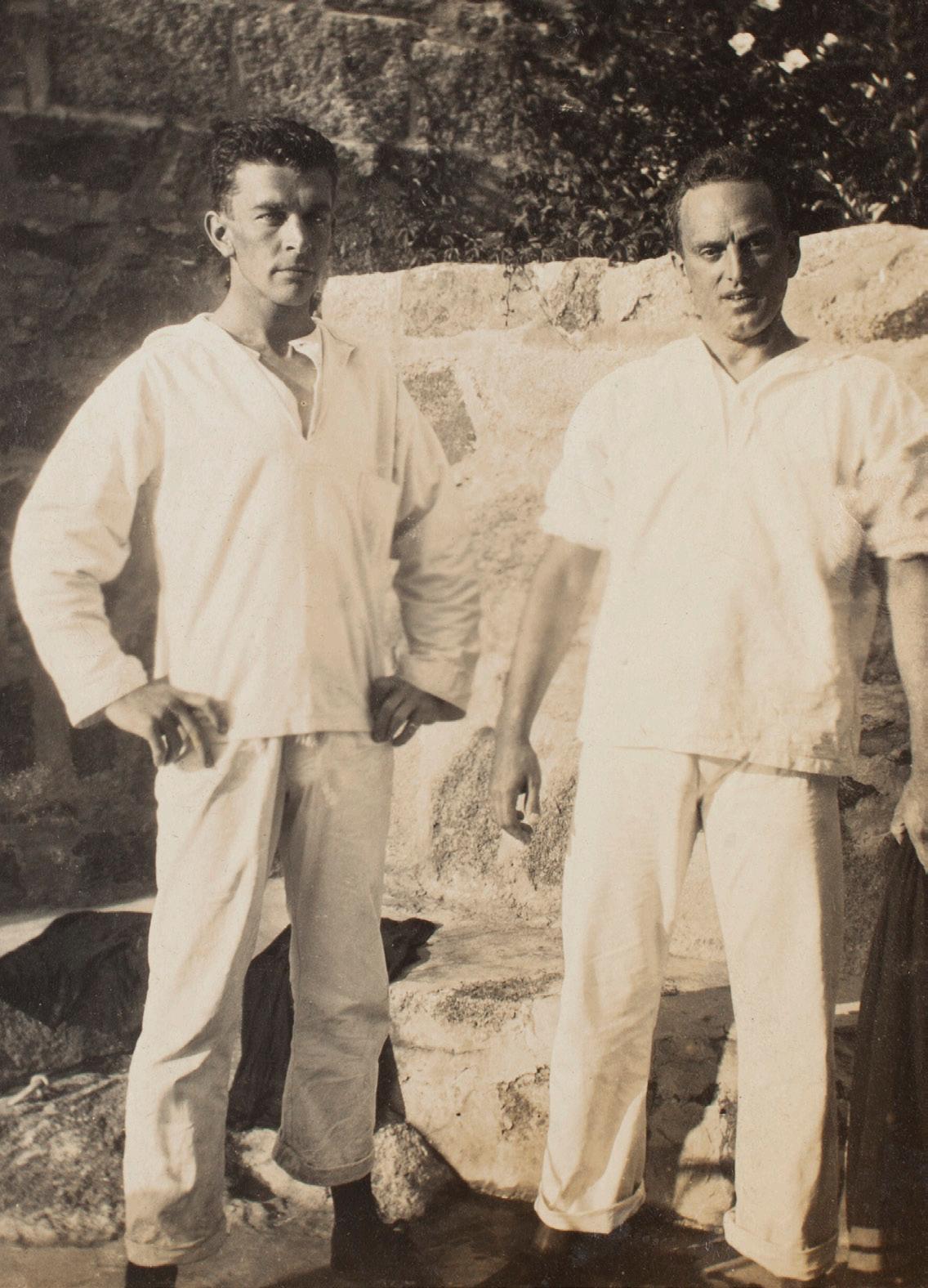

left From right, Edgar Rust (Harvard class of 1904), a fixture at Red Roof from 1906 until his marriage in 1909; Andrew; Louis Victor Allard, a Harvard French professor; and Andrew’s friend and next-door neighbor, Sleeper on July 30, 1908. below A swimming party at Red Roof on July 3, 1911. Andrew is at the far right and longtime companion Jack Mabbett is at the upper left. Also pictured are Adolphus Andrews, Willing Spencer, sisters Julia and Alys Meyer (center), and an unidentified woman. An avid swimmer and tennis player, Andrew hosted an energetic schedule of outdoor activities for his summer guests. page 15 Andrew and Mabbett posing in “pyjamas” at Red Roof in June 1911. Their eight-year relationship would end with Andrew’s departure for France at the start of World War 1.

artists, collectors, politicians, socialites, academics, and Boston Brahmins. Scores of pages document visits by Andrew’s friends, among them Sleeper, the painter Cecilia Beaux, and Isabella Stewart Gardner, whose flamboyant signatures occupy more real estate than any other (under one, Gardner writes, “Oh, how they spoiled me!”). In addition to Red Roof’s regulars, the guest books feature cameo appearances by artist John Singer Sargent; financier and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr., a scion of the notable family; first lady Helen Herron Taft; theater and film actor H. B. Warner; and art historian Bernard Berenson. Other noteworthy signatures include those of Alice Roosevelt Longworth, writer, socialite, and Theodore Roosevelt’s eldest child; U.S. Senator Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island; and Maria Longworth Nichols, founder of Rookwood Pottery in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Although Red Roof attracted a wide circle of Andrew’s peers, Harvard undergraduates and recent alumni dominate its early guest lists. Over nine days in April 1904, to cite a particularly hectic—if emblematic—example of these parties, Andrew hosted a rotating group of thirteen Harvard men at his five-bedroom home. Handsome, athletic, boisterous, and openly affectionate with their host, these young men (including a twenty-one-yearold Franklin Delano Roosevelt) clearly

claimed “Doc” Andrew as one of their own. Mugging for the camera and posing for self-proclaimed Red Roof sports teams, they penned locker-room nicknames for one another like “Stink Foot” and “Wooly Bottom” (Andrew’s moniker was “Smut”).

The worlds these guest books summon, from the elegance of al fresco luncheons to the high spirits of a costume party (Andrew appears dressed as Pope Leo XIII and a Roman emperor), all hold an undercurrent of mystery. We are left to wonder, for example, at the complicated bonds between Andrew and his inner circle. The otherwise formidable Gardner and Beaux, who were Andrew’s senior by decades, appear playful and even flirtatious in his company. For his part, Sleeper—four years younger than Andrew, and possibly his most ardent acolyte—often looks strangely ill at ease in the photographs. As a lifelong, eminently eligible bachelor, Andrew seems to have both attracted and confounded those who knew him.

At best, the guest books offer an incomplete view of Andrew’s own romantic interests. His demonstrative attitude toward male guests might suggest same-sex desire to modern viewers, yet we must place these images within their period context: a time when affectionate friendships between men were far more easily expressed. In at least two cases, however, Andrew appears to have developed intense, likely romantic relationships with younger men. Edgar Carter Rust (Harvard class of 1904) first visited Red Roof at a house party in June 1904, and by the following month he was accompanying Andrew on an extended European tour. Rust is rarely missing from the guest book’s pages in 1904-1905; from July to September 1905 he spent twenty-two nights at Red Roof as Andrew’s sole guest. His nickname, recorded in September 1904, was “Stallion.”

Rust’s successor, James (“Jack”) Fiske Mabbett (Harvard class of 1908), first came to Red Roof during the fall of his senior year. As with Rust, his appearance within larger parties led to sustained periods as a single guest; indeed, during the spring and summer of 1908, Mabbett spent so many nights with Andrew that his father ordered him home to Plymouth, Massachusetts— an event that coincided with Andrew’s resignation from Harvard to join the National Monetary Commission in Europe. In the winter of 1908-1909 Mabbett reunited with Andrew, continuing as his regular guest for the next six years.

The First World War would forever alter the

worlds of Red Roof. In 1915 Andrew sailed to France to establish the American Field Service, a wartime commitment that resulted in a four-year gap in the guest book entries. Within two years of his return, he would enter Congress to represent Massachusetts’ Sixth District and serve in that position for the next fifteen years. The distractions of Andrew’s new life in Washington are reflected in the changed character of the guest books: photographs appear more rarely, and soon disappear entirely, and house parties occur less regularly and feature larger gatherings of onetime-only guests. The intimacy of Red Roof’s early years appears to have been yet another war casualty.

The guest book entries ceased altogether six years before Andrew’s unexpected death from influenza in 1936, at the age of sixty-three. Inside the back cover of the final volume he tipped in a poem by Anne Hathaway titled “Red Roof”; in these lines Andrew appears as “the geni of the place” and his home is a “shrine… undimmed through all the wasting woeful years.” The poem’s refrain presciently evokes both Andrew’s premature death and the short-lived “golden age” of prewar Red Roof:

The greater the charm, the sooner it passes. The sooner it passes, the greater the charm.