7 minute read

Shaping the Vision

by CARL R. NOLD President and CEO

SHAPING VISION the

Leadership changes have been a catalyst for growth at Historic New England

As we look back at the 110-year-history of Historic New England, we see cycles at work. It falls to volunteer and staff leadership to identify a path to the future by which boards of trustees and other governance groups and senior staff can lead institutions into the future. Shaping a vision is their role, and effectively sharing that vision with the public and building support for it is their job. Historic New England founder William Sumner Appleton premiered a new vision for a preservation organization in 1910—not a single-focus group that would save just one threatened landmark, but a region-wide body capable of stepping up whenever and wherever needed to undertake the still-novel task of “preserving” a historic place.

Appleton drove the organization to develop philosophical and practical approaches to historic preservation where none existed in this country. He experimented with how to make it all work, putting some properties into use as museums, renting out others for commercial activities such as tearooms and antiques shops, and designating some to be occupied by resident overseers. The founder gradually moved the organization to its understanding that maintaining authenticity and original building fabric was far more important to the future than whatever restoration or reconstruction might be accomplished today. He wrote in 1930: “The more I work on these old houses the more I feel that the less of W. S. Appleton I put into them, the better it is.”

William Sumner Appleton died in 1947, still working, having acquired forty-five properties for the organization, as well as

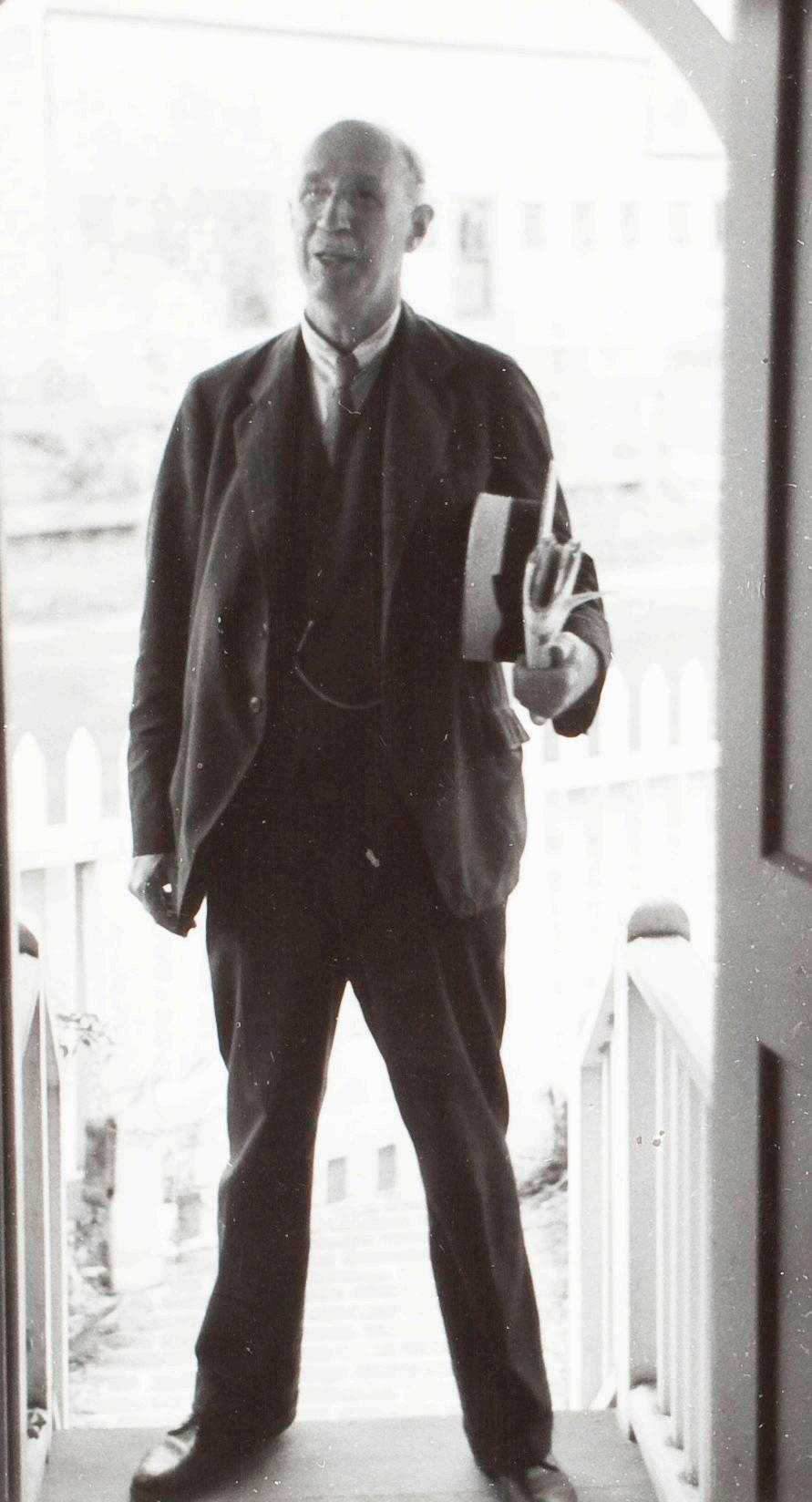

page 8 William Sumner Appleton in the doorway of a house on Nantucket in 1937. top Nina Fletcher Little and Bertram K. Little working on her book American Decorative Wall Painting 1700-1850 at their Cogswell’s Grant home in Essex, Massachusetts, now a Historic New England museum. above Nancy Coolidge (standing, left), Abbott Lowell Cummings (seated, right), and other staff members and trustees.

Jane and Richard Nylander

outstanding archival and artifact collections that prioritized documentation and explanation over aesthetics and financial value. Bertram K. Little followed Appleton. He continued the focus on property acquisition as a primary means of preservation and began building an organization to fulfill the many duties that his predecessor largely handled alone. Scholarship expanded, and collections and architectural expertise were acquired through new hires and building networks with like-minded organizations. Prestige and national leadership accrued. When preservation took to the national stage in the 1960s, practices modeled at Historic New England were integrated into national preservation policy. During Little’s tenure, collections growth continued in accordance with Appleton’s vision, increasing the number of properties stewarded along with the filling of barns and attics with objects.

As Historic New England entered the 1970s, the burden of caring for its real estate and artifacts tempered the organization’s capacity for the risks that come with preservation advocacy and hands-on interventions. Abbott Lowell Cummings, who was a scholar and a preservationist, acted in both those realms. Author of the classic book on colonial architecture, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725, his work included collaborating on the first analysis of Boston’s Quincy Market for possible rehabilitation and fighting the destruction of the city’s West End—and indeed, Otis House—by urban renewal efforts. Spinoff projects of most of those tasks, however, were adopted by newly forming state and local preservation organizations in the region.

Historic New England’s vision in the 1980s was of necessity one of stabilization. The organization, a sprawling champion of American preservation, was faltering under the demands of too many properties, too few dollars and staff, and too many needs for itself and New England. Nancy Coolidge was charged with implementing a vision for success, one that included the creation of alternative methods for protecting New England’s treasures. The Preservation Easement Program was created to permanently protect, with ongoing oversight, historic properties that were returned to private ownership and local tax rolls. Educational programs were expanded. Collections were more sharply focused, with objects that were outside the consistent theme of New England home life transferred to other organizations by sale or gift, as with Shaker holdings and a collection of fire engines. Also, collections storage was centralized in Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Special efforts were made to grow endowments to support

programs and to increase earned revenue. It was a controversial time of change, but essential to a reenvisioning that had to address financial and physical sustainability for the organization.

The success of the Coolidge years opened the door to fully professional museum practices, bringing a higher standard of care to buildings and objects. Under the leadership of Jane Nylander, the museum role of the organization was more fully defined and implemented. A marketing function was added to the staff to build visibility. Nylander emphasized the importance of sharing research and restarted the longtime scholarly journal Old-Time New England. Realizing that the organization could reach a broader audience through publication, she replaced the journal with Historic New England magazine, targeted to public members as well as scholars.

To make the collections more accessible, the staff began developing traveling exhibitions and explored options for creating museum space in Boston. This included a test of modern offices and public gallery space at One Bowdoin Square, near Otis House. The economic crash that followed 9/11 turned the country and the nonprofit world on end. Endowments dropped dramatically, budgets were slashed, plans and programs were shelved.

Facing these new realities, the Board of Trustees took hold of ideas that were percolating as part of the new museum vision and began thinking differently about the future. Nylander retired in 2002, and I joined the organization in spring 2003. The concept of a new single-building museum was shelved in favor of strengthening the historic site network and being a more public-focused institution.

This required a much-broadened definition of who the organization intends to serve, opening the door fully to the general public and “everyone’s history.” The most visible change was the rebranding as Historic New England in 2004, intended to be more welcoming and more readily identifiable to all than the often-used acronym SPNEA.

Program changes were also essential to establishing wider public appeal. A series of national traveling exhibitions was tested, then regional exhibitions, and ultimately a focus confirmed on exhibitions inside and outside the historic houses. Educational programs were doubled in size thanks to generous grant funding and opening new locations. Family-friendly programs were established at sites. Partnerships connected the organization to people who valued the land, or saw the connections between historic preservation and community good, as with a program to shelter abused animals in conjunction with the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

The organization’s centennial in 2010 was a catalyst for building more public visibility and access. The celebration focused on the future, with the centerpiece exhibition at the 2010 Winter Antiques Show in New York City creating national attention. The initiative 100 Years, 100 Communities presented programs around New England, including fifty locales that were new to the organization. The centennial provided the impetus for fulfilling a vision of greater use of collections by supporting the online Collections Access program that makes hundreds of thousands of records and images available worldwide. The vision of being a more public institution continues, with records set steadily over the last decade for attendance, membership, and school programs.

Now, in its 110th year, Historic New England is ready to welcome a new president and reevaluate its vision. Some of the elements driving this new assessment are increasingly diverse audiences, changing interests in and perceptions of American history, and a growing emphasis on protection of land and water resources. Other factors include the challenges of increasing costs and care of centuries-old buildings, as well as sea level rise and other environmental threats. Are there too many properties to be sustainable, or are there not enough to tell diverse stories of New England life? What role should the organization play in defining new methods, such as use of contemporary materials in historic buildings? How do we improve physical and intellectual access to historic places without altering their character? Can earned income be increased without damaging the sense of place that is so valued at the properties?

Some may think of preservation organizations as unchanging. However, history shows that this organization, founded by antiquarians in 1910, has evolved constantly. Today it can continue to build on a century of accomplishment to find new ways to respond to such questions as it works to save and share New England heritage.