historic NEw england

The Books that Planned the American Dream

Modeling Mid-century Suburbia in Rhode Island

Philip Rosenberg Antiques Dealer of Charles Street

Philip Rosenberg Antiques Dealer of Charles Street

I couldn’t be more honored to serve as Chair of Historic New England at this time of momentum, as dynamic new initiatives are propelling our organization in expansive, deeply meaningful, and exciting ways. Recovering New England’s Voices, our organization-wide historical research effort, is building, introducing, and sharing fully inclusive stories at our sites, and our bold new initiative to reimagine our collections storage facility in Haverhill, Massachusetts – to become the Historic New England Center for Preservation and Collections, a “living archive” for our members and the public – are just two of many initiatives underway to strengthen our public role and civic impact.

This issue of Historic New England magazine demonstrates the diversity and cross-disciplinary nature of our organization, including a section with highlights from the first Historic New England Summit, where more than 600 leading voices came together from preservation, conservation, education, the arts, and philanthropy to share information and experience. It was a thrilling event, fostering the importance of working together for enhanced livability and sustainability in our region. And this year, we’ll be holding our second annual Summit in Providence, Rhode Island, on November 2 and 3, and I look forward to seeing you all there.

Private citizens, committing time and resources, have been the drivers of the preservation movement from the beginning, and this was certainly true of Historic New England’s own founding as one of the nation's first preservation organizations led by William Sumner Appleton, a preservation catalyst ahead of his time. Strong, effective leadership is indeed a tradition at Historic New England. I want to thank my predecessor, David A. Martland, who held the position of Chair with great distinction for six years, successfully leading the organization during a time of both progress and pandemic, and onboarding our new President and CEO Vin Cipolla in the summer of 2020. Vin has brought vision, experience, and execution to our organization that is transforming our work at every level.

Dave and Vin, our trustees, advisors and council, dedicated staff, and all of you are the heart and energy of all the dynamic work underway, making a difference for our region and the communities we call home. In just a few days on March 11, we’ll celebrate the civic and philanthropic leadership of two members of our community who’ve been devoted to preservation and our region’s cultural fabric in truly profound ways – 2023 Historic New England Medal honorees Janina A. Longtine MD and Peter S. Lynch. I hope to see many of you at our extraordinary medal gala at Boston’s historic Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel.

Thank you for your commitment to Historic New England and to the history and health of our remarkable region. It’s your commitment and confidence in us that keep Historic New England at the forefront of preservation practice, innovation, outreach, and storytelling. I look forward to sharing our achievements and our story with you in the months to come.

Deborah L. Allinson Chair

Deborah L. Allinson Chair

HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership. To become a member, visit HistoricNewEngland.org or call 617-994-5910. Comments? Email Info@HistoricNewEngland.org. Historic New England is funded in part by the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

President and CEO: Vin Cipolla Executive Editor: Diane Viera Editorial Review Team: Lorna Condon, Senior Curator of Library and Archives; Erica Lome, Associate Curator Design: Julie Kelly Design

The inaugural Historic New England Summit, held October 13 and 14, 2022, attracted more than 600 participants via livestream and in person at historic Mechanics Hall in Worcester, Massachusetts. The conference convened a transdisciplinary audience from across the region and beyond to address timely issues and strengthen our collective network dedicated to creating more inclusive, sustainable, and livable communities. Here are takeaways from some of the outstanding leading voices who took to the Summit stage.

What does history mean to our present moment? Dr. Leo Lovemore, librarian for history, society, and culture at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, opened the Summit with their keynote “Forging a New Lens” by emphasizing our shared responsibility to critically assess “the lessons, values, assumptions, and stories that we have inherited.” Dr. Lovemore challenged the audience to act when those inherited stories fall short of the full truth, and described a year spent carefully piecing together lost histories as a Recovering New England’s Voices research scholar at Historic New England. Dr. Lovemore reflected, “By looking backward with a new lens, we are never losing something precious. We are widening our perspectives, our contexts, and our commitments to forging more just and livable futures for all.”

Catherine Algor, president of the Massachusetts Historical Society, guided the Summit’s first panel through a discussion of what it means to share inclusive history. President of the Roxbury (Mass.) Historical Society Byron Rushing advised, “You don’t pick the people, you pick the geography and within that geography, you decide to tell the history of all people, no matter what.” Bethany Groff Dorau, executive director of the Museum of Old Newbury (Mass.), argued that her institution “is, and should always be, the place that holds space for the memory of everyone in the community…examined, as much as we are able, with the same lens as everyone else.” And Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Massachusetts, described programming changes that allow audiences to reflect on current issues. “Because what sense does it make,” she asked, “if we only talk about the eighteenth century when the legacies of slavery are still impacting the same communities that we want to reach?” With eyes on inclusivity, justice, and telling the full story, these opening remarks set the tone for two days of imaginative and inspiring conversations.

In an inspiring presentation that reflected on more than two decades of service to the largest Latinx cultural organization in the United States, Kate Lear, chair of the Ballet Hispanico Board of Directors, affirmed “the vital role preservation plays in achieving healthy, harmonious, and uplifted communities.” Ms. Lear spoke eloquently of performing arts institutions as catalysts for individual and community transformation and described how Ballet Hispanico’s physical presence on Manhattan’s West Side opens literal and figurative doors. After completing ambitious new construction and renovating their historic headquarters, “we were able to provide so much more to our community. Each year, dozens of public symposia, panels, and performances of all kinds are held there…to educate and encourage discussion about equity, inclusion, and other issues of cultural and social relevance.”

Hartford, Connecticut, shares the built heritage of many post-industrial New England cities – historic mills, factories, and entire neighborhoods recall a manufacturing past that has long since departed and left communities to rebuild their economies and identities in its wake. Mayor Luke Bronin described the critical role these historic buildings and districts are playing in Hartford’s revitalization and illustrated their transformations, from a historic transit depot reimagined as Connecticut’s first food hall to a former North End factory that now houses dozens of small businesses and a new branch of the Hartford Public Library.

What’s next on the agenda? “We want to continue that strategy of putting historic preservation at the heart of economic development,” said Mayor Bronin, but he’s also pushing for solutions to save historic buildings that don’t have outsize investment appeal. Citing the city’s Deborah Chapel, a rare and early American example of an intact Jewish funerary structure and important site in Jewish American history, Mayor Bronin advised that some assets are worth preserving regardless of broader economic impact. “It takes a public commitment [to recognize] that the payoff may simply be the preservation of history.”

Dr. Ed Carr, director of the International Development, Community, and Environment Department at Clark University in Worcester, moderated what was perhaps the Summit’s most optimistic panel – a conversation propelled by the belief that historic preservation can and will meet the threats of climate change head-on. Joined by Erik Kramer, principal at Reed Hilderbrand Landscape Architects, and Andrew Kapinski, director of horticulture at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston, the panel explored the ways in which an essential question – what, exactly, are we trying to preserve? – is rapidly changing.

Citing the historical development of the Summit’s host city, Dr. Carr explained that the patterns of growth, economy, and culture embodied in a community’s built environment also depict the climate legacy that has led to our current moment of challenge. Transformation is inevitable, he argued, but we have a choice “between the transformations we select, and the transformations that are done to us by an environment that we changed.”

Mr. Kramer and Mr. Kapinski illustrated their efforts to navigate those decisions. Mr. Kramer highlighted his reimagining of the Tidal Basin in Washington, DC, with a design that engaged the question, “how do we use design not to fight, but to move forward?” Preservation, the panel argued, must not be rigidly defensive, but must embrace the transformational changes happening to the world and facilitate the continuation of experiences, communities, and shared cultural landscapes.

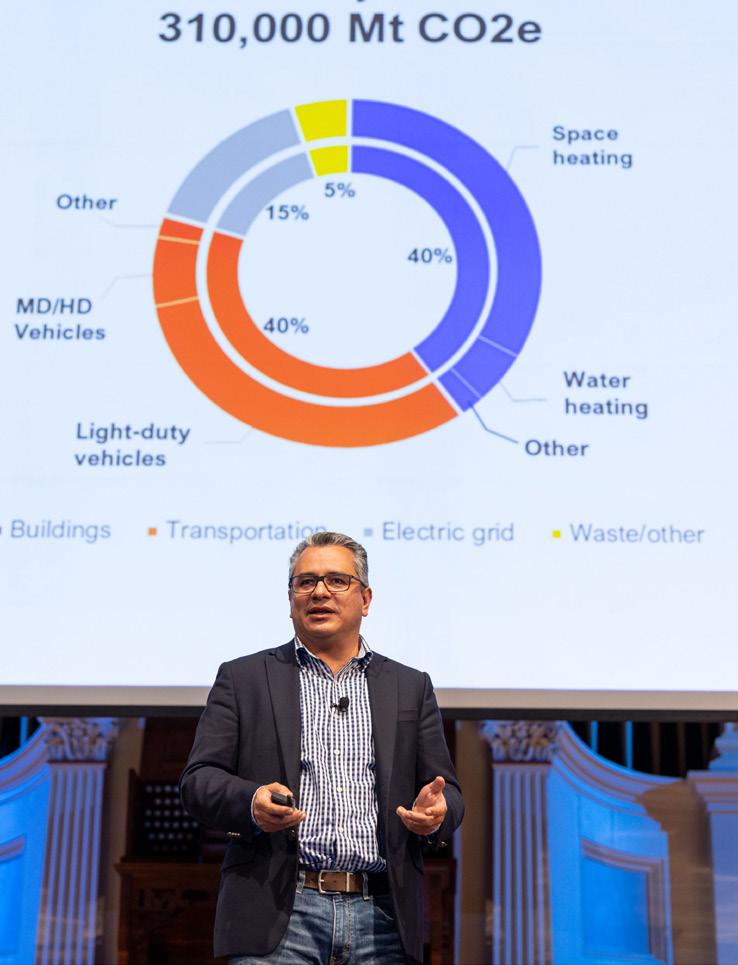

Following the panel, Dr. Luis Aguirre-Torres, former director of sustainability for the City of Ithaca, New York, discussed the ambitious Ithaca Green New Deal: the city’s plan to decarbonize by 2030. While his work has included detailed modeling of the city’s emissions and energy efficiency solutions, he argued that “climate change challenges are not all technical.” There is danger, he noted, “if you come in from the outside and say, ‘Here’s your problem, and here’s your solution.’ You’ve picked winners and losers.” In a final discussion among the panelists and Dr. Aguirre-Torres, the group concluded that climate action is not a zero-sum game. They envisioned a pluralized future in which people with diverse perspectives and expertise develop solutions grounded in a willingness to accept change. “When we look at history, we see that in moments of crisis…people do galvanize around change, and change happens in the landscapes around us,” said Mr. Kramer. “These are moments when we can do great things.”

Nick Redding, president and CEO of Preservation Maryland, and Sarah Turner, president of North Bennet Street School in Boston, shared the Summit stage to explore the nationwide status and local impacts of historic trades training in the United States. “Historic preservation trades are not a niche issue,” said Mr. Redding, illustrating his assertion with data from a new, first-of-its-kind study by Preservation Maryland and PlaceEconomics. Publicly unveiled at the Summit, the analysis concludes that historic rehabilitation is a large and growing segment of the construction industry, representing $85 billion in annual investment, and that the demand for trained workers is incredibly high. “Each year over the next decade,” he explained, “we’ll need 10,000 historic trades positions just to keep up…and in order to get there, we’ll need something like 20,000, almost 30,000 people going into training every year.”

Those in-demand workers-in-training can be found at North Bennet Street School, where Ms. Turner emphasizes a curriculum that aligns with the real needs of community partners “so that our students are learning the very things they need for their work, [while] partnering with someone who has a problem to solve.” Partnerships, Mr. Redding agreed, are key for institutions thinking about offering trades training: “Think about how you can partner with existing programs and add that measure of excellence, instead of trying to do it all on your own.”

History education has suffered ill effects from years of “teaching to the test” and the increasing polarization of our political climate. Dr. Françoise Hamlin, associate professor of history and Africana studies at Brown University, engaged a panel of educators who are confronting these obstacles in their respective environments and identifying ways to improve outcomes for students – and society – in the years ahead. Claudia Wu, co-founder of the Center for Civic Engagement and Service at Newton North High School in Massachusetts, reasoned that “in order to participate and be part of our democracy, you need to understand history. You need to see history from multiple perspectives. You need to think about it, debate it, talk to people about it.” Kenann McKenzie, director of the Generous Listening and Dialogue Center at Tufts University, Medford, Massachusetts, underscored the importance of engaging different perspectives “and suspending judgment in the context of those conversations, so that we can truly demonstrate and model for our young people what civil civic engagement looks like.” Cultural institutions in the audience received a direct call to action: help students make connections between past and present to deepen their understanding of history and encourage active participation in community life.

Communities across New England celebrate the arts with annual festivals that bridge cultures, classes, and generations. Festivals are “one of the easiest and most approachable ways into the arts and culture world,” Lisa Simmons of the Massachusetts Cultural Council noted in her opening remarks, adding that “festivals are for everyone.” With panelists Chris Serkin, Anne-Marie Soulliere, and James Naughton, the Summit audience visited three of New England’s most historic summer festivals from the comfort of their seats in Mechanics Hall and via livestream.

Mr. Serkin, president and chair of the Marlboro Music Festival, described a symbiotic relationship between Marlboro, Vermont, and its seventy-one-year-old festival that has taken on new importance following the closure of Marlboro College. Ms. Soulliere, trustee of the Ellen Battell Stoeckel Estate, detailed the thoughtful stewardship of the estate that hosts America’s oldest active music festival, the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival in Norfolk, Connecticut. And Mr. Naughton, a Tony Award-winning actor, spoke of the immersive experience of participating in the Williamstown Theatre Festival in Williamstown, Massachusetts. A careful balance of what Mr. Serkin calls “progress without change” has cemented each gathering’s significance as a cultural, social, and economic anchor to its community, encouraging the participation and engagement of old and new audiences.

Following this final session, the Historic New England Summit closed with an outstanding performance of Dvorak’s "Piano Trio in E Minor, Op. 90" by acclaimed pianist Dr. Melvin Chen, accompanied by Norfolk Chamber Music Festival fellows Evan Johanson on violin and Cheng “Allen” Liang on cello.

Special presentations at the Summit showcased concepts from four internationally recognized design firms for the vibrant futures of two of Historic New England’s urban properties.

Brandon Haw, president and CEO of Brandon Haw Architecture; Eric Höweler, co-founder + partner of Höweler + Yoon; and Deborah Berke and Arthi Krishnamoorthy of Deborah Berke Partners unveiled their responses to a design provocation to transform Historic New England’s collections care campus in Haverhill, Massachusetts, into the Historic New England Center for Preservation and Collections, a community anchor, hub of creative innovation, center for exhibitions and curatorial expertise, and cultural catalyst for the continued revitalization of this great historic city.

Nader Tehrani, founding principal of NADAAA, and former dean of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at The Cooper Union in New York City, shared his concept for Historic New England’s Otis House property in Boston comprising the 1796 Otis mansion and two connected nineteenth-century row houses. Through collaboration and partnerships, the site will have a responsive future as an inclusive and welcoming community resource, and a gateway to Historic New England and the region’s history.

Katherine Hall Page is the award-winning author of the Faith Fairchild mysteries (Wm Morrow/Avon). The Body in the Web, the twenty-sixth, goes on sale in May. Page has also published a cookbook, Have Faith in Your Kitchen, Small Plates (short stories), and books for younger readers. She lives in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Through her love of books, Page shares a personal and creative perspective on the Codmans' relationship with their family library.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the vast majority of people jump at the opportunity to look around when they are inside the homes of others. Upon so doing, some are drawn to examine the furniture, perhaps the bibelots displayed, while other eyes are drawn to the artwork hanging on the walls. However, when I walk into a room, what I call “bibliovoyeurism” takes immediate hold as I scan the books on the shelves and displayed on coffee tables.

They are what most clearly reveal owners’ personalities and pastimes. In short, the clues are in the books.

Turning left from the entrance hall into the library at the Codman Estate in Lincoln, Massachusetts, we are given an immediate opportunity to imagine what the family was like: Ogden and Sarah Codman, and their children, Ogden Jr., Alice, Thomas, Bowdoin, Hugh, and Dorothy. In 1862, after a period of fifty-five years, the Codmans had regained possession of the home

that Ogden and Sarah named The Grange. It was Tom and Dorothy's summer retreat until 1952, when they moved back year-round to Lincoln after selling the townhouse at 5 Marlborough Street in Boston that they bought after their mother's death in 1922.

The townhouse was also within walking distance of Boston’s most notable bookstores: Goodspeed’s, Lauriat’s, and the Old Corner Bookstore. None of the Codman children had children. Dorothy, the youngest, inhabited The Grange the longest, and fulfilled eldest brother Ogden Jr.’s wish that the estate be left to Historic New England after her death.

Ogden Jr., an architect, interior designer, and author of The Decoration of Houses with fiction writer and fellow interior designer Edith Wharton, was quick to change what had been Ogden Sr.’s billiard room into the library, getting rid of the huge game table. And what a library it is!

The earlier books indicate the senior Codmans’ taste, that of a Boston Brahmin couple. This predilection continued in the next

generation to some extent. When the Marlborough Street house was sold, the books there probably would have been added to those at The Grange. Happily, this was a family that kept hold of treasured volumes.

That it was a Francophile family is immediately apparent from the yards of elaborate jewel-toned, leather-bound volumes in French shelved on the cases lining the walls: Essais de Montaigne, Memoires De Talleyrand, Lettres de La Marquise de Sevigne, Lesage’s Gil Blas, the complete works of Balzac, Daudet, Zola, and many more, both fiction and nonfiction. There is a reason for this. Following the catastrophic Boston Fire of 1872, which destroyed much of their real estate holdings, the family moved to Dinard in northern France, and remained there for twelve years. Yet, the bookcases also hold classic literary works in English that we would expect to find in this kind of household: Plutarch’s Lives, Allison’s History of Europe 1815-1852, Lamb’s Works, Burns poems, Edward Everett Hale’s James Russell Lowell and His Friends, and Letters of James Russell Lowell edited by Charles Eliot Norton.

What is wonderful about the library is that it was well used. The books are not for show but have obviously been read and there is an assortment of titles that a designer would have tossed. These include a number of cookery books, many in French, with plain paper covers to protect the original ones: Mrs. Beeton’s Dictionary of Every Day Cookery (1865), Maria Parloa’s New Cook Book (1885), La Cuisine Exotique Chez Soi (1931) by Charlotte Babette Catherine, Escoffier’s Ma Cuisine (1907), Brillat-Savarin’s Physiologie du Goût

(1825), Miss Leslie’s New Cookbook (an encyclopedic 1837 work that included 1,000 recipes—from fried chicken to Italian pork—adapted for American kitchens, utensils, and measurements). Among the more recent cookbooks is Coffee Cookery by Helmut Ripperger (1940). Aside from its claim to be the first devoted solely to coffee recipes, Ripperger’s coauthors were Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle, who would go on to greater fame in 1961 publishing Mastering the Art of French Cooking with Julia Child.

Clearly, the Codman household was a family with a fine palate, savoring a wide variety of cuisines. While in Lincoln, they would have enjoyed what the farm produced and, in the Boston dwelling, too, there must have been versatile cooks in the kitchen.

The library has been filled with light the times I’ve been in it and the furniture is perfect for curling up with a book, not just the Zola and Trollope tomes. There is a shelf of eight Reader’s Digest volumes from 1957–1962 that may have been Dorothy Codman’s. Was she drawn by the bestsellers Good Morning, Miss Dove (1950) by Frances Gray Patton? Or The Day Lincoln Was Shot (1955) by Jim Bishop? Another shelf has an assortment ranging from Gilbert Highet’s Poets in a Landscape to The Most of S. J. Perlman, a humorist—all books from her later days in the house.

Leaving the library for the drawing room—the 1799 Federal hall used as a ballroom and transformed into the pleasant spacious family gathering place in the 1860s—there are books with clues aplenty. American Gardens, edited by Guy Lowell (1902); Cyclopedia of American Horticulture

and

John R. Whiting’sA Treasury of American Gardens indicate a desire for a broad knowledge of gardening. The view from the windows of the beautiful results of this interest must have been extremely gratifying.

There are several guides covering the British card game whist, popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including American Whist (1890), as well as several copies of Hoyle’s Games. I picture the Codmans enjoying these parlor games—before there was screen time of all sorts—after dinner on a summer evening. The sense of leisure hours is also conveyed by the titles lined up on the tabletops as if someone had set them out as “to be read” or “reread,” among them: The Victor Book of The Opera, Richardson’s Clarissa, Sinclair Lewis’s The Man Who Knew Coolidge, and Radclyffe Hall’s The Master of the House

That this was a well-traveled family is revealed by a well-thumbed Inglese–Italiano dictionary and a large number of fiction and nonfiction unbound paper editions, mostly in French, some in English. These were sold with the intent that the purchaser would have the book bound in hardcover if desired. The bound Trollopes in the library are an example of that, with a few of the original paper Tauchnitz editions (the German publisher who pioneered the method) remaining. In pre-

Kindle days, the Codmans would have bought these books to read on trips abroad.

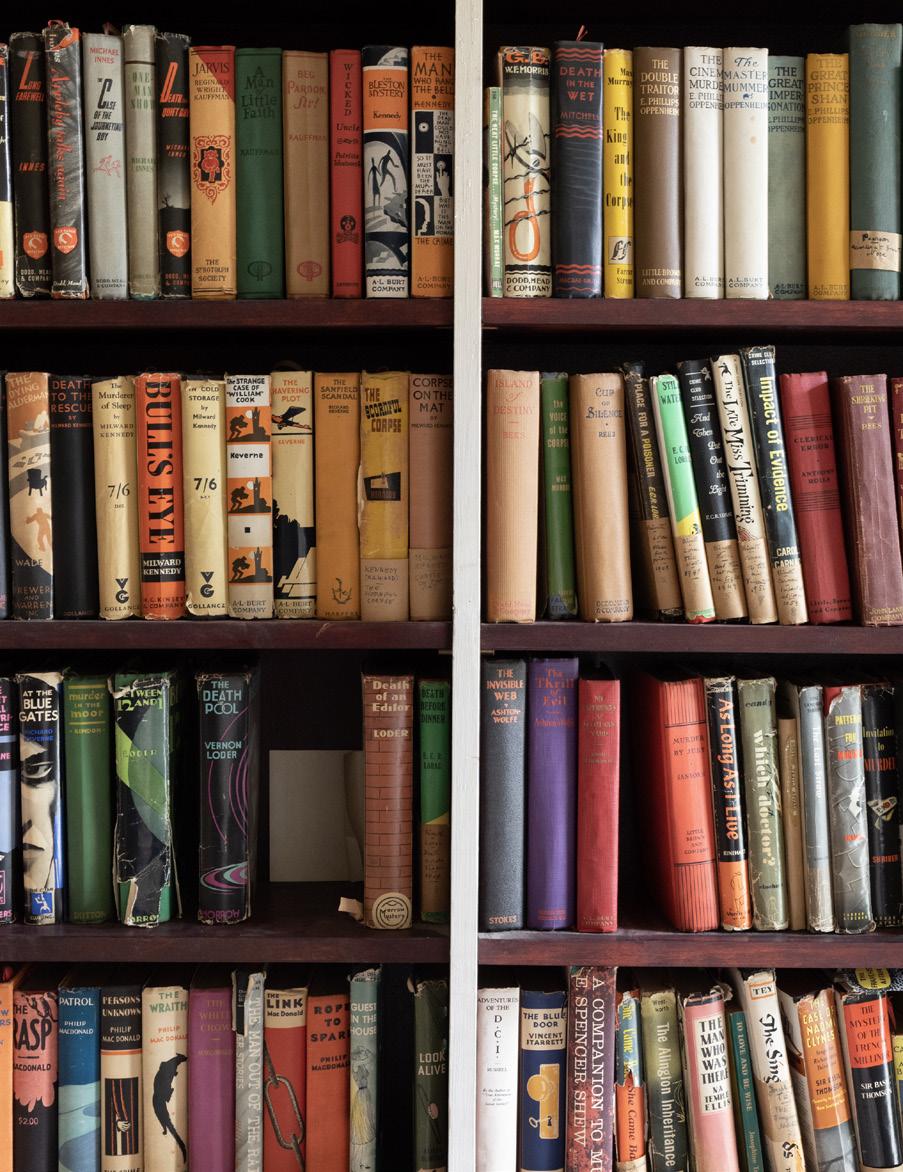

The drawing room is a beautiful place to linger, and by now this family has been revealed in some detail by their books—one devoted to pleasures of travel, the table, the garden, and intellectual pursuits— but an amazing clue awaits. A denouement. Not in the charming blue and white morning room (only a dozen horticultural books, including well-worn field guides, in a very narrow case behind a chair), nor the impressive Elizabethan-style dining room (wonderful china and art, no books), but located in an out-of-the way place: the domestic staff’s back stair. Behind the doors of simple hanging white-painted cabinets, of a type to hold various household objects, are shelves filled with hardcover crime fiction (pictured on page 8). Most are in the original book jackets, dating from the 1920s to the end of Dorothy Codman’s life in the late 1960s. For me, a reader and writer of mysteries, it was like looking into Ali Baba’s cave. Some of the cabinet doors are stuck shut and others are locked—making the

thought of the unknown contents tantalizing. I showed the some 160 titles I was able to photograph and list to Stephen Powell, owner of Bar Harbor/Mystery Cove Book Shop in Hulls Cove, Maine. He is a world-renowned authority on the genre and was able to fill in some of the blanks for me—authors I did not know.

Dorothy Codman shared her family’s love of French literature and the language, but when it came to her personal library, she was a devoted Anglophile, although I later learned there were some titles in French, notably Simenon’s Maigret series. Most of the titles are from the “Golden Age” of British crime writing (roughly 1920–1950). I recognized, among others, what must have been her favorites based on the number of titles: Philip MacDonald and E. Phillips Oppenheim—the James Pattersons of the time. There are sixteen titles by Anthony Gilbert, many in the series featuring the London lawyer and amateur detective Arthur Crook. This author’s name was a new one for me. And it was not the writer’s real identity; Anthony

Gilbert was Lucy Beatrice Malleson’s nom de plume. It was a joy to see many authors I enjoy: Josephine Tey, Patricia Wentworth, Ngaio Marsh, E. X. Ferrars, and Mary Roberts Rhinehart. The mysteries of Rhinehart, an American, were written in what came to be termed the “Had I But Known” narrative style, which was enormously popular. Many of the titles were adapted for the theater, film, and television. At the time of her death her books had sold over ten million copies. Then there is British novelist Patricia Wentworth, known for her amateur detective Miss Maud Silver, a retired schoolmistress of a certain age who gently steers Scotland Yard in the right direction. Rhinehart had a similar series with the protagonist Hilda Adams, a private duty nurse. Both are older main characters, women who go against type.

Murder is at the forefront, but there is humor as well in Dorothy Codman’s choices. And her choices reflect an insistence on good writing. All the authors were known for their expertise and there were many award winners among them. The books also convey a strong sense of place and inform period details.

When I asked Stephen Powell to engage in bibliovoyeurism and describe the reader of the collection, he responded, “I’d say Dorothy Codman was a welleducated lady with a preference for sophisticated puzzles over action and thrills.” We both agreed that she would have eagerly anticipated a new title from her favorite authors and ordered it from bookstores. The Concord Bookshop opened its doors in 1940 and may have been one.

Many of the books have small, handwritten paper labels on the base of the spines with the author, title, and a date—that of purchase it seems. I learned from Powell that in many cases, the jackets are worth more than the book with the jacket; pristine book covers, especially

Whist is a classic strategic English trick-taking card game popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A precursor to bridge— often mentioned in literature: Jules Verne, Jane Austen, Tolstoy, Colson Whitehead—whist variations abound.

those of certain cover artists, are rare. It is ironic that what some may have viewed as lesser literature is much more valuable than all the leatherbound sets elsewhere in the house and certainly more than the stacks of National Geographic issues.

There are books all over the house. Tantalizing! I am writing about what I could see, but I am sure this family read other British detective fiction—Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, and others. Tucked between the hardcovers there were a few Penguin paperbacks with green covers denoting the genre. More elsewhere?

Inevitably I became most interested in Dorothy Codman, the youngest in the family. Based on the books she read I have formed a picture of what I believe was a delightful woman, a kindred spirit. I learned that she collected Dennis the Menace comic strips, which debuted in 1951. Over tea I’d like to ask her why she was attracted by the energetic five-year-old who truly tries to help people, but always finds himself in trouble with an “All’s well that ends well” ending.

I came across an article, “Lincoln and the Codmans,” written by Lincoln resident Thomas Boylston Adams for Old-Time New England in 1981. He describes an encounter when his mother went to the house for help after her automobile broke down at the Codman front gate. She rang the doorbell and out “burst Dorothy Codman, profuse in greeting, overflowing with pleasure and hospitality.” Adams recalled visits with “all of us children, now quite grown up” that followed at Dorothy’s insistence. He goes on to describe a scene in late October 1940, when having proposed at a nearby location and been accepted, he and his fiancée, Ramelle Frost Cochrane, went to tell Dorothy, Hugh, and Tom their secret. “Their joy and happiness was as sincere as if it had been their own.”

I reread some of Dorothy’s books that I own, and my bibliovoyeurism became something much more. Whitman’s phrase, “Whoever you are holding me now in hand” came to mind as I felt a joyful connection with this particular booklover and her family, an invisible thread tying me to the twentieth, nineteenth, and even eighteenth centuries on the shelves of The Grange.

by ELIC WEITZEL

by ELIC WEITZEL

Elic Weitzel is an archaeologist and doctoral candidate at the University of Connecticut. He is fascinated by how people both adapt to and modify their environments, and his current research concerns the ecological consequences of European settlercolonialism in seventeenth-century New England. He has conducted archaeological fieldwork along the East Coast of the United States as well as in Eastern Europe.

In October 1637, Roger Williams—the founder of Rhode Island—wrote of a troubling rumor that had reached him: he heard that there was an Englishman living among the Mohegan Tribe in Connecticut.

In that day and age, such news was unprecedented, scandalous, and existentially threatening to European society. A white man, born and raised in England and recently arrived in North America, had left his own people and taken up with a Native tribe. To make matters worse, this man was not only living with the Mohegan, but he had married a Native woman and fathered a child. His name was William Baker.

Today, searching history books

Conjectural depiction titled “Roger Williams Seeking Refuge Among The Indians” from a 1902 American history book by Henry Davenport Northrop. After he was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635, the outspoken Puritan minister who advocated religious tolerance and believed that Indigenous peoples were the rightful owners of North American lands sheltered with the Wampanoag in the early part

for references to Baker produces little success. He is treated as no more than a minor footnote in the colonial history of New England, mentioned only in a series of five letters between Roger Williams and Governor John Winthrop from October 1637 to May 1638, and then never heard about again. I first encountered these mentions of William Baker while reading Roger Williams’s correspondences as part of my dissertation research several years ago. Given their age, all these letters are now in the public domain, so anyone can find digitized versions of them through a quick internet search. Though I was reading Williams’s letters while conducting research unrelated to cross-cultural adoption, I found Baker’s story fascinating. Yet I could find hardly any mention of the man’s existence in other sources.

What I have been able to find suggests that Baker most likely sailed to Plymouth Colony from England sometime in 1632. Beyond the letters of Roger Williams, little is known for certain about his life. There were two men named William Baker living in Plymouth, Massachusetts, by 1633

(and more William Bakers would arrive soon after), so it is difficult to ascertain who is who in colonial records. But in a letter from October 1637, Roger Williams says that when he himself lived in Plymouth between 1631 and 1633, he heard stories of our Baker’s “evil course that way with the Natives,” suggesting that even then, Baker already had a reputation for being a bit too close with Native folks.

In September 1633, the Plymouth colony established a trading post on the Connecticut River near the present-day town of Windsor, Connecticut, and Baker was one of the men sent there. Sometime in the ensuing four years, Baker’s life changed dramatically. As Williams tells us, by the autumn of 1637, Baker had left or been kicked out of the Windsor trading post and a Native woman had become pregnant with his child (though not necessarily in that order). He then settled down with a different Native woman and lived with her tribe, the Mohegan. Baker is said to have been able to speak the Mohegan language.

Three months later, in a second letter, Williams details additional activities of Baker. He writes that Baker has “turned Indian in nakedness and cutting of hair, and after many whoredoms, is there married.” Baker, who had arrived from England just a few years prior, was now living as a Native American man. He had learned to speak the language, fathered a child with one Native woman, married a second, and was now wearing his hair and dressing in the Mohegan style.

But why was Williams so

concerned about one Englishman residing with the Mohegan who had “turned Indian?” The problem was not that one Englishman left his own people for a life among a Native tribe, but that many did. Baker may have been one of the first, but within a few decades, he was far from alone in his preference to live his life with Native people. Many hundreds of European settlers either voluntarily joined Native tribes or refused to leave after being captured and adopted. Many of these accounts have been synthesized and analyzed by historians like Colin Calloway and James Axtell, who write that those renegade white settlers described a stronger sense of community, more social equality, and a general sense of greater freedom in Native cultures. To be sure, many white captives happily returned to their former lives, and some violently resisted capture and adoption. Hannah Duston, for example, was taken from her home in Haverhill, Massachusetts, during a raid in 1697 and reportedly watched her Native captors kill her infant. She then killed and scalped ten members of the Abenaki family—six of them children—who were holding her, another woman, and a boy before making her escape and collecting a bounty from the government of Massachusetts for the scalps. Yet many others, like the adopted Seneca woman Dehgewanus, originally named Mary Jemison, declined to leave their tribes even when free to return to colonial society. Some colonists are even known to have refused “rescue” from perceived Native captors, having to be bound like prisoners and returned to colonial settlements so that they wouldn’t flee back to their adoptive

Native communities.

These people, like Baker, who chose to live as adoptees in Native American tribes, shook the foundation of European and American society. European colonialism and imperialism were (and are) predicated on the assumed superiority of European culture. It was taken as fact that everyone would be better off living as Europeans did, and that when given the chance, people would gladly become part of European civilization.

William Baker, however, was proof that life was not necessarily better in Europe or its colonies. Here was an Englishman who preferred to live with the very people whom the English were trying to “civilize,” whose cultures were deemed savage and inferior and whose souls were said to be in need of salvation. That an Englishman could leave European society for a life among a Native American tribe threatened to reveal the falseness and hypocrisy of European cultural superiority.

Accounts from this period highlight the confusion and alarm of European colonists in the face of this evidence against their presumed superiority. At a 1699 peace treaty signing in Albany, New York, nearly all of the French prisoners taken by the Iroquois during the preceding conflict refused to leave their Native captors. This occurrence was recorded as being far from unique, as the English also had trouble convincing their own people to return following time spent with Native groups. Benjamin Franklin commented on this same trend, writing that “when an Indian Child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our Customs, yet if he goes to see his relations … there is no perswading him ever to return.

But when white persons of either sex have been taken prisoners young by the Indians, and lived a while among them … they become disgusted with our manner of life … and take the first good Opportunity of escaping again into the Woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.”

To be sure, Native society was not some idyllic utopia. Generalizing across tribes is problematic, but practices such as entrenched gender inequality, forms of slavery, and sometimes brutal violence were often commonplace. In fact, violence was often how white settlers and others were adopted into Native tribes: through ceremonial torture. Yet it is telling that despite all of this, so many Europeans and Americans opted to reside with Native tribes nonetheless.

Sadly, according to the letters of Roger Williams, William Baker was not permitted to live in peace with his adopted tribe and new family. Williams’s October 1637 letter notes that Baker was pursued by the Colony of Connecticut for “uncleanliness” with a Native woman, which may indicate that Baker was forced to flee the Windsor trading post sometime between 1633 and 1637. In a letter from early 1638, Williams wrote that Uncas, the chief of the Mohegan, was ordered to return Baker to the English, but that Baker had “again escaped.” Reading between the lines, one must wonder whether Uncas had any intention of turning over his adopted compatriot. The English soldiers threatened death to any Native person who concealed Baker from them, but none came forward to turn him in.

Unfortunately, Baker’s luck would soon run out. In May 1638, Williams wrote that despite Uncas's attempt to hide Baker, Baker was captured by a contingent of English soldiers

and taken to Hartford, Connecticut. There, he was held as a prisoner and whipped “for his much uncleanness.”

In the wake of Baker’s capture and punishment, Williams revealed his fears that Baker was too “strongly affected” by his adoptive Native tribe and that Baker and the Mohegan were “studying revenge.” Williams’s worries reflect the political context of the time. The English had just won the Pequot War, and the few surviving members of the Pequot Tribe were mostly adopted by the Mohegan. Williams feared that the Mohegan and the Pequot survivors would rise together against the English with the help of Baker. To prevent this from occurring, Williams recommended the “prudent disposal and dispersion of the Pequots”—whom he blamed for concealing Baker—and that the Mohegan should not be trusted.

Nothing more is known of Baker following his capture and punishment at Hartford. Following the incident, Williams expressed his belief that Baker should be separated from his adoptive Native family and monitored for seditious tendencies. Perhaps this was Baker’s fate and he remained in Hartford or returned to Massachusetts Bay or even England. One might hope that instead, Baker found a way to escape the English and live out the rest of his life with his Mohegan family. We will probably never know, but the story of William Baker’s life as an adopted Mohegan man on the run from English “justice” provides great insights into the politics of seventeenth-century New England, the widespread appeal of a Native way of life, and the fears that English colonial leaders had about their subjects betraying their natal cultures to do as Baker did and be “turned Indian.”

Artifacts and archival materials are powerful steppingstones to understanding social history, and Historic New England's collections are at the heart of our site experiences, public programs, and research.

We are committed to growing our world-class collections to better reflect the diverse stories of those who lived, worked, and created in this region. Telling these holistic stories requires collaboration with new communities, artists, and makers with a wide range of backgrounds, racial identities, and cultural affiliations who can help us build collections that tell fuller stories about culture, taste, migration, trade, and labor in New England. Through this outreach we are building a collection that future generations will depend on to

understand New England’s full and inclusive history.

Senior Curator of Collections Nancy Carlisle, who retired at the end of 2022 after thirty-five years with Historic New England, has been a leading advocate for the expansion of our collections. To honor her work and commitment to collecting artifacts and archival materials that share the multitude of stories, the Nancy Carlisle Collections Acquisition and Care Fund has been established to support the purchase of objects from contemporary artists, crafters, makers, and communities to ensure our collections are expansive, inclusive, and accessible to everyone.

Please consider honoring Nancy and supporting this important work. To make a gift, visit www. HistoricNewEngland.org/Carlisle or send your gift to Nancy Carlisle Collections Acquisition and Care Fund, Historic New England, 151 Essex Street, Haverhill, MA 01832.

Interested in discovering more about Historic New England’s collections? Visit https://www. historicnewengland.org/explore/ collections-access/.

above Nancy Carlisle, retiring senior curator of collections, in artifact storage in the Historic New England Center for Preservation and Collections.

In the late nineteenth century, historian and philanthropist Jane Norton Wigglesworth Grew made a patchwork quilt to memorialize the lives of twenty different colonial women. Grew sewed the quilt with scraps of fabric that were previously owned by these women. The quilt offers us a window into the histories of the women whose lives are woven into its very fabric.

by MARINA NYEMarina Nye is a PhD candidate in history at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her dissertation explores the different forms of sartorial reuse and repurposing in eighteenth-century North America. She is an assistant curatorial researcher at the Autry Museum and a 2022-23 fellow at the Washington Library at Mount Vernon.

Grew was born into an affluent Boston family on November 11, 1836. As a child, she attended Professor Torrey’s private school for girls where she learned her love for needlework and history. Grew took a great interest in education and donated to schools in the

South. For twenty-four years Grew served as the director of the Elizabeth Peabody House Association which aided poor families in Boston. At the age of twenty-seven she married Henry Sturgis Grew, a successful mill owner and banker. Together they had six children. Their daughter Jane Norton Grew would go on to marry John Pierpont Morgan Jr., the son of the famous banker.

Jane Norton Wigglesworth Grew had a passion for her own colonial heritage. She was a proud member of the Massachusetts Society of Colonial Dames from 1899 until her death in 1920. She was also a member of the New England Historic Genealogical Society as her roots in the region could be traced back to the seventeenth century. As a part of her fascination with history, Grew actively preserved artifacts. Upon her death, her estate donated approximately 180 objects to Historic New England so they could be preserved for future generations. This patchwork quilt is among the donated items in the collection.

The quilt was a multigenerational project. Most of the fabric fragments were woven in the eighteenth century. Grew’s mother and grandmother, Henrietta May Goddard Wigglesworth (1805-1895) and Lucretia May Dana (1773-1866), likely acquired the fragments during their lifetime. Grew inherited the scraps and sewed them into the quilt.

The quilt held tremendous value to Grew. It reflected her deep interest in preserving American colonial heritage. Affluent nineteenth-century women like Grew made it

their mission to revive colonial traditions and stories in order to illuminate the achievements of their female ancestors. Grew replicated the colonial tradition of needlework while simultaneously recording the material histories of colonial women. The time required to sew the quilt also suggests its sentimental value. The various thread colors used (yellow, black, beige, green, and white) indicate that Grew worked on the quilt for multiple years. When a quilt features different thread colors, it often means that the seamstress worked on the quilt over a period of time and used whatever thread she had on hand. Finally, the quilt is in excellent condition. In the midnineteenth century, Grew displayed the patchwork quilt as upholstery on a pillow. However, the pillow was more often admired than used since the textile has very little wear and tear. It was a piece of material history that she mindfully preserved.

Why did Grew include these twenty women? The quilt pays homage to the legacy of prominent colonial New England women that she admired. Carefully pinned to each scrap of fabric is a piece of paper that details the fabric’s use, the year, and the woman who owned it. With this information, the quilt memorializes the women who once owned the fragments and offers a valuable glimpse into their lives. For example, multiple wedding dress fragments are incorporated into the quilt, such as the gowns worn by Madam Amory (Katherine Greene Amory), Mrs. Thomas Dennie (Sarah Bryant Dennie), and Mrs. Mansfield (first name unknown). The preservation of these wedding gown fragments suggests the significance of marriage to New England society. Beyond sentimental value, these fragments reflected a social achievement. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a prosperous marriage was crucial for affluent women like Amory, Dennie, and Mansfield.

The curtain fragments owned by Mrs. Samuel Appleton (Mary Lekain Gore Appleton) and Mrs. Joseph Tilden (Sarah Parker Tilden) suggest the central role fabric played in colonial life. Textiles were especially important to Appleton and Tilden because they came from prominent merchant families that sold fabric. Both families would have displayed these expensive curtains in their home as a demonstration of wealth. The Appletons even featured their curtains in a silhouette art piece. Both Tilden and Appleton preserved their expensive upholstery which suggests these objects were valuable to them.

In addition, Grew’s quilt pays tribute to women from famous revolutionary families, like Martha Washington and Dorothy Quincy Hancock (as their names appear on the quilt). Scraps previously owned by Washington and Hancock are woven into the quilt. Textiles owned by famous women held sentimental and monetary value because many Americans wanted a piece of America’s legacy through sartorial tokens. These materials were symbolic of the Revolution and the founding of the country.

Grew’s quilt also incorporates lesser-known female figures. Mrs. Samuel Bradlee’s (Mary Andrus) fragment was likely from a dress she wore during the later years of her life (1700-1796). All five of her children, David, Josiah, Thomas, Nathaniel, and Sarah played important roles in the country’s founding as participants in the Boston Tea Party. Her daughter, Sarah, was even dubbed as the mother of the Boston Tea Party. Bradlee’s dress was likely incorporated in the quilt to pay tribute to her maternal skill in raising republican children. The quilt serves as a memorial to the women who helped build the nation.

While the quilt names twenty different women, many other unnamed women were involved in

John Singleton Copley, Mrs. John Amory (Katherine Greene), about 1763. MFA, Boston.

its creation. Before the textiles formed a quilt, they passed through the hands of hundreds of unknown people. Spinners, weavers, seamstresses, and upholsters touched the fabric. Once the fabric was worn or displayed, it was sold, gifted, inherited, reused, or repurposed by other hands. It is impossible to determine how many people are interwoven into the story of the quilt. However, the quilt allows us a glimpse at the true reach of one object. Hundreds of people, artisans, merchants, consumers, and historians contributed to its existence.

Jane Norton Wigglesworth Grew created a patchwork quilt that memorialized colonial women’s achievements, values, and traditions in American history. In so doing, she recorded her identity and the history of prominent colonial women with a needle and a thread.

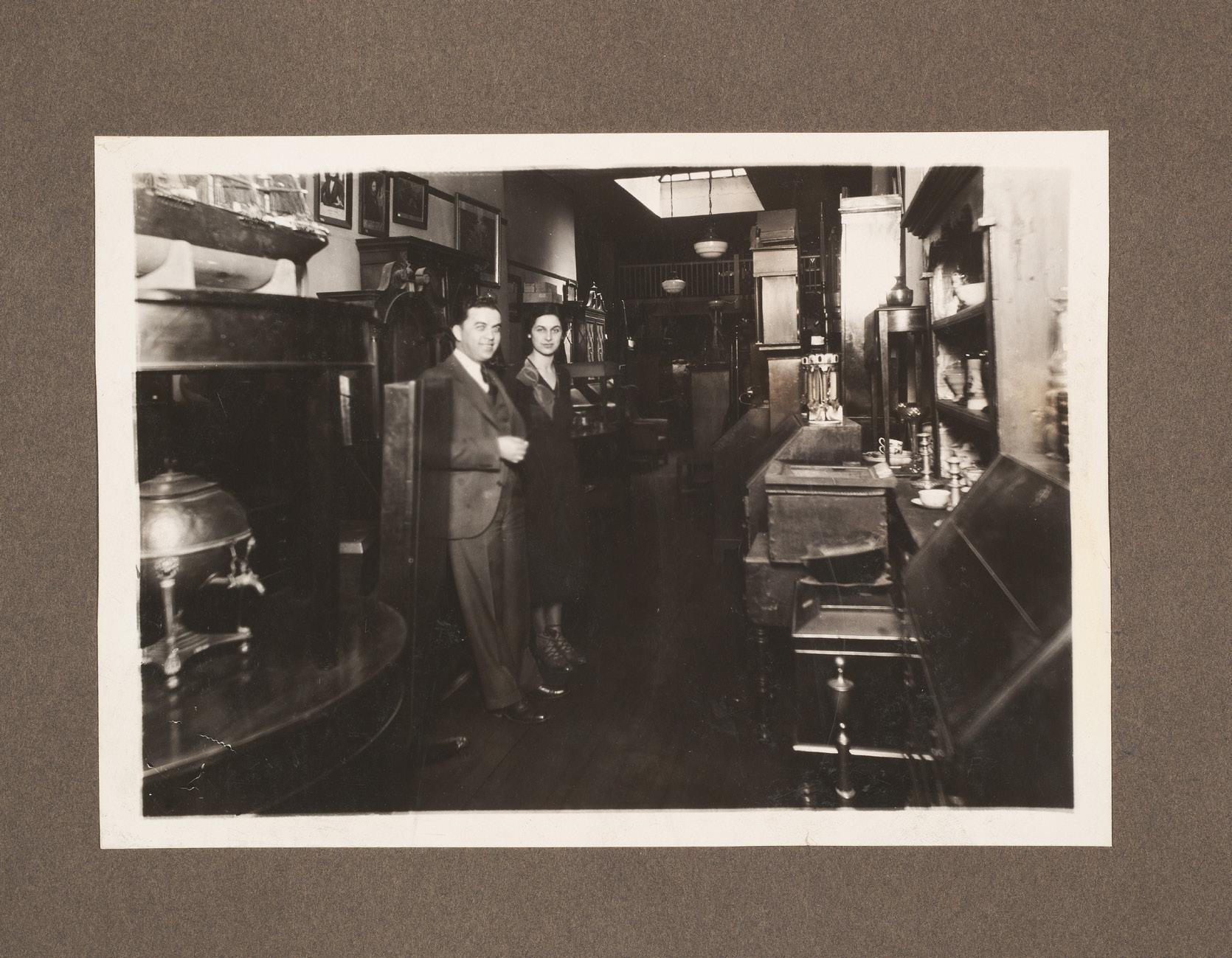

Jewish immigrant Philip Rosenberg brought vigor to the American antiques trade in the early twentieth century

isitors to Charles Street in Boston in the 1920s could find themselves at the center of America’s love affair with the past. Shop after shop offered

antiques, silver, and other decorative arts from the colonial period. In one of its earliest issues, The Magazine ANTIQUES featured Charles Street in its directory of Boston

antiques shops, informing readers that “Hundreds of New England families that have not yet parted with all their historic furniture let occasional pieces go, and collectors

continually reduce surplus or dispose of items of minor value in favor of rarer examples. The dealer seems an invaluable go-between in many of these transactions.” The majority of these “invaluable” Charles Street antiques dealers were Jewish immigrants from Europe, including Philip Rosenberg (1878-1951), proprietor of The New England Antique Shop. During the early twentieth century, Rosenberg made a name for himself in the antiques business as a buyer and dealer of, among other things, period furniture, hooked rugs, English ceramics, and Pennsylvania redware. His business earned a reputation for quality and excellence, as did Rosenberg himself. Historic New England recently acquired a gift of photographs, furniture design drawings, trade catalogues, and ephemera from The New England Antique Shop. This collection provides a glimpse into the broader contributions of Jewish immigrants to the American antiques trade.

A Russian-born, native Yiddish speaker, Rosenberg immigrated to the United States in the late nineteenth century. He was previously a peddler in Europe, as were many other Jewish immigrants who entered the antiques trade. Most had apprenticed as cabinetmakers before coming to America. Cabinetmaking, like tailoring or shoemaking, required a degree of skill to learn and execute, yet had flexible working hours and was ideal for the religiously observant. Cabinetmaking also offered a pathway to entrepreneurship, so that a trainee starting in a shop could reasonably accumulate enough capital to rent or buy their own shop and staff it with kinspeople. By the late nineteenth century, antisemitism in Europe had intensified and antiJewish riots (known as pogroms) swept the Russian Empire. These factors, among others, no doubt prompted Rosenberg and his family to go to America.

In Boston, Rosenberg encountered an industry in formation. The 1904 Boston Directory showed only three self-declared “antique” shops, but by 1918, the numbers had jumped to twenty-eight, and by 1924, forty-seven. The growing antiques market created demand for specialists who could evaluate, restore, and reproduce period furniture. Most American-born cabinetmakers lacked the training to execute certain types of work by hand, such as carving, inlay, and joinery; instead, they learned to operate furniture-making machinery. Skilled immigrant craftsmen filled those gaps in the trade, and many leveraged their experience to become prominent antiques dealers. Rosenberg probably drew on long-established Jewish occupational networks to secure his first job in America. By 1922, Rosenberg was working in the back of the shop of fellow Jewish immigrant Louis Palken (18831940), owner of The New England Antique Shop. Working in Palken’s shop introduced Rosenberg to collectors, who brought their finds to the craftsmen for repair. They would become Rosenberg’s first antiques buyers in 1926 when he and his business partner, Max Webber, took over the business.

The transition from handson cabinetmaker to dealer was increasingly common among Jewish entrepreneurs like Rosenberg. First-hand experience with woodworking allowed Rosenberg to oversee repairs, discern forgeries, and evaluate furniture based on construction techniques. His neighbors on Charles Street, including Israel Sack, a Lithuanianborn cabinetmaker-turned-dealer,

marketed themselves as well positioned to help buyers navigate the complex world of collecting and connoisseurship. As the new coowner of the business, Rosenberg continued to offer the same goods and services many had come to expect from the Charles Street shop: antiques and reproductions to order. Rosenberg traveled throughout New England to search for the former, knocking on doors and asking to look inside attics and barns for dusty, old furniture that could be transformed, with the help of a good cabinetmaker, into prized antiques.

Rosenberg’s stock was relatively modest in comparison to that of Israel Sack or Philip Flayderman, whose 1929 auction drew recordbreaking prices. They each acquired large groups of antiques from New England collectors at high prices, thereby inflating the market. This business practice worsened already trenchant nativism and antisemitism among their Yankee clients. Antiquarians like Walter Dyer, author of The Lure of the Antique (1910), believed the “birth and breeding” of the immigrant dealer made it impossible for the purveyor “to appreciate a single thing he owns, except as it represents cash.” However, these opinions did not stop collectors from working with Jewish dealers. While Rosenberg’s personal feelings on the matter went unrecorded, the American antiques trade gave many Jewish dealers both financial security and a sense of belonging to their adopted homeland. Some even became experts on American decorative arts and freely shared their knowledge with the public.

Rosenberg’s business flourished after he exhibited highlights from his

shop in New York City at the first International Antiques Exposition in 1930, where one reviewer commented, “To use a phrase of salesmanship, the American public is ‘sold’ on antiques.” Americans were also sold on reproductions. A high-quality copy was a perfectly acceptable option for affluent consumers looking for a wedding or retirement gift, or to fill a gap in an antique furniture suite. Less affluent consumers sought reproductions to emulate the interior design of early American households; these

consumers may not have had family heirlooms, but they could purchase an “heirloom of tomorrow.”

Rosenberg outsourced this work to the Irving Furniture Company, a mid-size firm in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Order forms show that Irving supplied colonial-style furniture to Rosenberg to sell in his shop, such as a pie-crust table, satinwood chairs, and magazine racks. Rosenberg was also involved in the production process, evidenced by several furniture design drawings in the collection.

One of these designs for a Chippendale-style chair (labeled “Set B”) includes a full-size rendering of the chair back. The designer paid deliberate attention to the details of the pierced splat and scrolled ears, no doubt inspired by genuine eighteenth-century examples—or perhaps by the antiques in Rosenberg’s shop. Yet, the chair itself has no direct eighteenth-century precedent. Early twentieth-century designers often combined elements of Chippendale or Hepplewhite furniture that educated consumers would recognize in their products. This was not a deceptive practice, but a pragmatic, cost-effective choice for both parties. The volume of orders Rosenberg placed (at least a dozen for each form and style) indicates a healthy market for highquality reproductions. Rosenberg could rely on this secondary trade

to supplement his business while he collected old New England furniture.

In addition to antique furniture, Rosenberg specialized in hooked rugs, a nineteenth-century form originally made by lower-income households using recycled textiles. Interest in hooked rugs was revived by needlework practitioners and antiques collectors in the 1920s, who enjoyed them for their whimsical, colorful designs. One of Rosenberg’s biggest customers was Henry Davis Sleeper, who bought many hooked rugs for himself and his interior design clients. Sleeper acquired more than fifty hooked rugs over his lifetime to decorate Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, his summer home in Gloucester, Massachusetts, which Historic New England now owns.

The 1930s represented the peak years of The New England Antique Shop. A dispute between Rosenberg

and Webber in 1945 ended their partnership; while Rosenberg continued to operate the business alone, he closed its doors in 1949; two years later, he died at the age of seventy-seven. The contents of the shop were put into storage for nearly seventy years before they were sold at auction.

Philip Rosenberg and the Jewish antiques dealers of Charles Street were more than just an immigrant success story; these new Americans profoundly shaped the antiques market, guiding how early American furniture and decorative arts were to be valued and understood. Now part of museum collections across the nation, including Historic New England’s collection, the treasures they collected and restored continue to inform how we think about American heritage.

From its founding in 1663 until 2020, Rhode Island's official name was the "State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations." Among those "plantations" - defined historically as large agricultural tracts that used slave labor to grow produce for profit - was Casey Farm in Saunderstown.

The land now called Rhode Island is the homeland of the Narragansett, Wampanoag, Niantic, and Nipmuc people. Casey Farm is located on the homeland of the Narragansett people. Early colonizers soon found that the rocky soil of this region was not the best for raising crops, so they turned to raising livestock and to the sea to make a living. By 1750, the date we believe the farmhouse was built, 19 percent of those in the Casey Farm region were enslaved people of African and Indigenous descent - far more than in the rest of the state and any other northern colony. Most Rhode Island plantations, including Casey Farm, produced wool, mutton, and cheese, which were exported through the key city of Newport, principally to the Caribbean. Besides supporting themselves, slaveholders in the West Indies used Rhode Island products to feed and clothe the people they enslaved on sugar plantations. People in bondage who were forced to labor on farms, in households, and in businesses formed the backbone of Rhode Island’s economy.

Taking a step toward a more equitable and truthful telling of the history of the lands and properties it stewards, last year on Juneteenth (the federal holiday enacted in 2021 to mark the effective end of

slavery in the United States on June 19, 1865), Historic New England dedicated a Rhode Island Slave History Medallion (RISHM) at Casey Farm. The medallion honors the peoples whom European colonialism made victims of centuries of oppression, dispossession, and enslavement to ensure the longterm sustainability of the farm and the profits of their subjugators. The medallion stands as a marker of Historic New England’s long overdue efforts to acknowledge these facts in ways more tangible and lasting than gallery labels or site tours.

RISHM founder and CEO Charles Roberts says RISHM was formed in 2017 "to raise public awareness of Rhode Island's dominant role in the institution of slavery, to commemorate the lives of the enslaved, and open a dialogue for racial understanding and healing."

Historic New England began a partnership with our neighbors at the Narrow River Preservation Association who believed that Casey Farm, as the only intact former

plantation and one that is open to the public, should be the site of a Rhode Island Slave History Medallion. The marker would lead people to RISHM’s website (rishm.org) to discover as much information as we can provide about the history of slavery associated with the property and the region. We learned that we needed to ground our interpretation with more in-depth research.

We knew that English colonizers initially forced Indigenous people into slavery when they went to war against the Pequot and then the Wampanoag and Narragansett peoples between the 1630s and 1670s; enslavement was the price of their defeat. In the eighteenth century, Newport became the major importation center and auction block in the country for human cargo from Africa. The docks of Newport were where Silas Casey (1734–1814) purchased three enslaved Africans. They were called Ezekiel, Walter, and Moses.

Through research in Historic New England’s archives and many other

sources, an expanded story emerged. Hannah Francis, a research scholar in our Recovering New England Voices initiative, found more facts and provided context for the lives of these three men. She found that the legacy of enslavement by the family that owned Casey Farm extended through the centuries and controlled the lives of fifteen people. Four were named in records: Phillis, Peter, and Betty and her baby, Jeffrey.

Casey Farm’s Rhode Island Slave History Medallion is dedicated to Ezekiel, Walter, Moses, Phillis, Peter, Betty, and Jeffrey. They were bonded to the Morey/Coggeshall/ Casey family, along with numerous unnamed and unrecorded people who worked these lands. We still benefit from the labor forced from them, labor tied to racism and oppression, even as we strive to enlighten ourselves and our visitors and work toward inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility within and through Historic New England. Partnering with Black, Indigenous, and other people of color

via organizations and individuals, we are on a journey toward decolonizing our museum gallery and outdoor spaces.

With guidance from our partner nonprofits, we made connections with speakers, performers, and food providers to plan last year’s Juneteenth celebration that acknowledged the practice of slavery and commemorated the lives of those held in bondage. The medallion was cast in bronze and is set in a granite post on Casey Farm’s front lawn. Every visitor who comes for a tour, for a children’s education program, for the farmers market, or most any other reason, sees the marker, bringing facts to light about all the people whose lives contributed to the survival and success of this place, and our research continues to recover even more of this history.

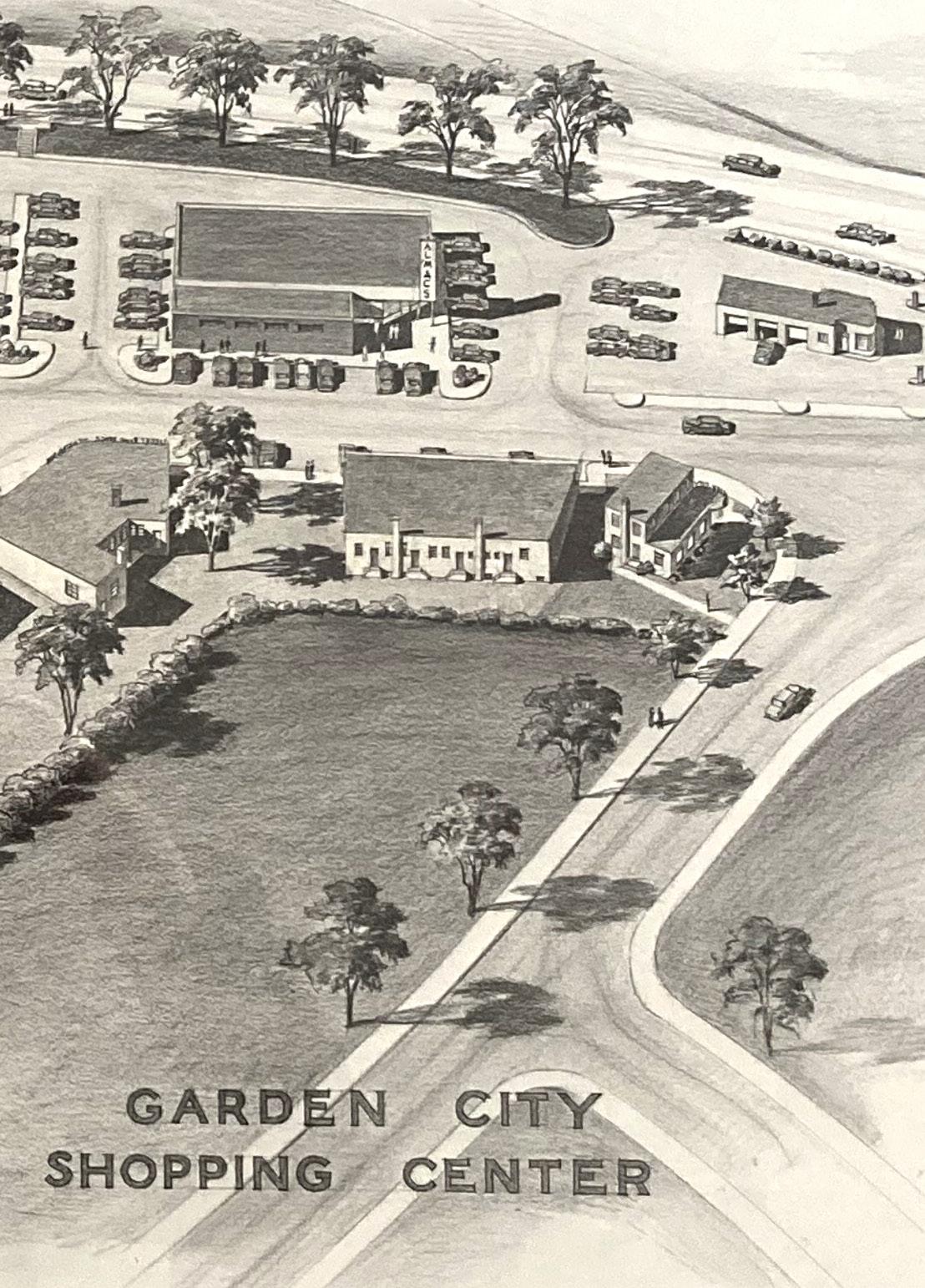

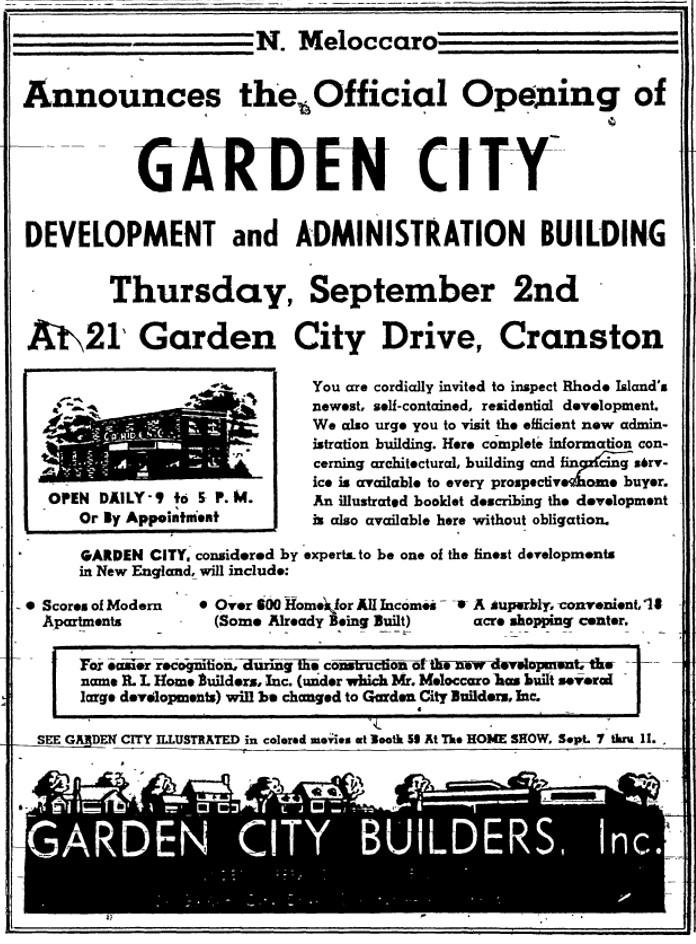

America’s landscape was transformed by post-World War II development. However, despite the ubiquity of construction from this period, relatively little research has been done to understand its context and design – particularly in New England. In this article, Jennifer Robinson, a Cranston, Rhode Island, native, introduces us to Garden City in Cranston, currently the subject of an indepth survey being conducted by The Public Archaeology Lab (PAL). The survey, which is the first of its kind for a mid-century Rhode Island development, will be released in 2023, and its findings will be included in the summer issue of Historic New England magazine.

When asked to define a stereotypical New England house, most people probably have a similar image in mind. The iconography of New England is well established

and fixed in the American psyche; postcard racks are filled with images of rural eighteenth-century farmsteads, historic seaside streets, and clapboarded mill villages. However, despite these common visualizations, it is interesting to

consider that the majority of homes in New England were built after World War II. In Rhode Island, for example, approximately seventy percent of extant housing was built after 1940. The built environment of postwar America is defined by a

widespread ambition to construct single-family homes for a burgeoning middle class, and in Cranston, Rhode Island, the state’s second-largest city, this trend is evidenced in many housing developments. Its most comprehensively designed plat, however, is Garden City, which began construction in 1946. It was introduced in the Cranston Herald as a “City within a City” – one that would include a ready-made “Main Street,” complete with pharmacy, luncheonette, salon, supermarket, hardware store, and specialty shops, along with a church and school.

The idea of building a planned community from scratch is not strictly a mid-twentieth-century concept; a previous generation had grappled with the negative impacts of industrialization by envisioning green, spacious suburbs separated from cities. The so-called “garden city movement,” espoused by Ebenezer Howard in Britain during the late 1800s, is one example of this type of aspirational city planning. During the post-World War II era in the United States, however, suburban planning was taken to new extremes, and in many ways, Garden City shares many of the tropes of national postwar development. It received funding from the land planning

division of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and its winding, serpentine streets are in alignment with FHA directives. Houses are neatly set back from concrete curbs, with manicured lawns and picture windows. And the lack of racial diversity in its first homebuyers is also indicative of broader national trends – that of movement away from city centers to suburbia, with the availability of cars, infrastructure, and postwar capital leading the way.

Because of the ubiquity of New England developments of this kind, and their proximity to the recent past, it might be easy to dismiss Garden City as another clichéd housing tract. However, there are deeper and more nuanced stories yet to be uncovered in these communities that may, at first glance, seem to have identical trajectories. With the release of the 1950 US Census in April 2022, for example, a clearer picture of Garden City’s first residents is now accessible for the first time. A cursory survey revealed that a significant portion of early homebuyers were first- and second-generation immigrants from Italy, Czechoslovakia, Ireland, Austria, Russia, Greece, Romania, Lithuania, Poland, Turkey, and Sweden. Although not an entirely unique phenomenon in housing developments nationwide, the influx of new immigrants into postwar suburban developments has often been overlooked. Emerging research into this trend, in books such as Houses for a New World (Barbara Miller Lane, Princeton University Press, 2015), has begun to unpack demography that has been traditionally oversimplified.

In addition, an astounding range of occupations found in the 1950 Census reflects the availability of homeownership to a wider audience than one might expect. Jewelry factory workers, bus drivers, and US Navy personnel could purchase homes adjacent to those of doctors, retail managers, engineers, and bankers. A modest house on Garden City’s Poplar Drive could be purchased for about $9,600 in 1950 – now shocking to consider when the same house, in 2022, was sold for $395,000. Local newspaper listings from the 1950s indicate a strong sense of community, with myriad clubs, organizations, and charity groups meeting in the development’s shared recreation hall.

Perhaps most interestingly, the mastermind behind Garden City’s particular vision of suburbia was

Nazzareno Meloccaro, himself a first-generation Italian immigrant. Born in Pontecorvo, Italy, in 1903, Meloccaro arrived in Providence, Rhode Island, at the age of seventeen, and in the 1920s, began working in the construction industry. By 1931, while living in Cranston, he became a US citizen, and by the late 1940s, he had procured 233 open acres just over two miles from Cranston City Hall –a landscape characterized by farmland as well as a coal and graphite mine.

Meloccaro was joined by a local engineer, Peter Cipolla, who conceptualized Garden City’s plat layout and was responsible for its survey drawings. Additionally,

Meloccaro hired Adolph Otto Kurze, a son of German immigrants, as the housing development’s chief architect. The first structures to be built were apartments – ninety-four units hailed in the Cranston Herald (1950) as "…miniature replicas of the large apartment houses found in New-York City." These were followed by single-family homes, built both on speculation and to order by union laborers in a variety of styles and price ranges. There were modest ranches and Cape Cods, colonials, and split-levels which were, as a whole, relatively distinctive in scope. Kurze was clearly attempting to avoid the repetition of other famous

developments such as Levittown, New York, often derided by national critics for its mind-numbing uniformity.

It is unclear whether Meloccaro was working from a specific model, but a 2019 interview with Kenneth Kurze, Adolph Kurze’s son, revealed that Melocarro’s team conducted reconnaissance in the 1940s at other housing developments, including in the suburbs of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Kurze learned about construction techniques and site layout during this trip. Interestingly, there is a suburb in the Pittsburgh area also called Garden City –indicating a possible connection, at least in name, between these two locations.

Simultaneous to Kurze’s house design, an unknown architect was drawing up plans for a commercial center that would provide retail and service amenities to the neighborhood. Unified commercial and residential development was a concept that was already being explored before World War II; developments like Country Club Plaza (1922) in Kansas City, Missouri, often cited as America’s first suburban shopping center, contained an architecturally unified design with space for ample parking. On the west coast in particular, development of automobile-oriented shopping centers in the post-World War II period reached a crescendo and served as models for similar designs throughout the country.

What makes Garden City stand out, particularly in New England, is its effort to cohesively integrate its Main Street with housing. Many New England housing developments certainly were built in proximity to commerce – the so-called “strip mall” being a prime example of this type

of automobile-driven development. However, Garden City’s approach is considered the first of its kind for Rhode Island, and the neighborhood, along with its accompanying lines of storefronts, quickly became a realm of its own. Prestigious Providence department stores, including Gladdings (c. 1954) and the Outlet Company (1962), built satellite stores in the outdoor shopping center; residents and visitors could access businesses from either neighborhood streets, or a newly expanded four-lane highway on New London Avenue.

Now, nearly eighty years from its inception, Garden City has retained

its function as both a community and a commercial hub. There also is an intact sense of place, despite the recent demolition of the plat’s original 1952 elementary school, and a gradual shift from locally owned service businesses and shops to largely national retail chains. Although the material composition of house exteriors has been altered significantly – wood cladding replaced by vinyl siding, wood sash changed to vinyl windows – an essential integrity of form and scale remains relatively stable. Vistas down Begonia, Lawnacre, and Juniper drives would still be recognizable to Nazzareno

Meloccaro and his colleagues, with the exception of now-mature trees.

Despite its intactness, like many other developments of this type, Garden City lacked an indepth survey to understand its historic significance in the context of twentieth-century planning, social history, demography, and architecture. The findings of the 2022 survey are nearly compiled, and Historic New England looks forward to sharing new details in the next issue of Historic New England magazine.

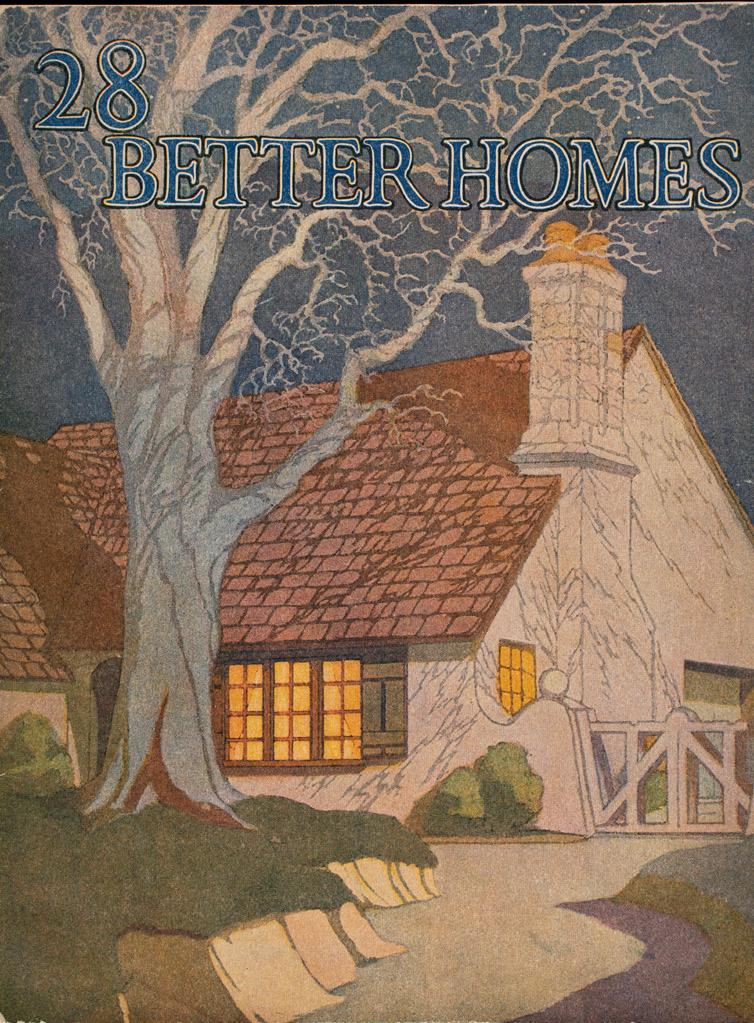

Richard Cheek's extraordinary collection of plan books illustrates the myriad house types and styles available to Americans in the twentieth century.

by LORNA CONDON Senior Curator of Library and Archives

Home ownership is a key element of the American Dream. From the beginning of the twentieth century, the expanding national economy made home ownership achievable for many Americans. To address the demand for houses, architects, publishers, and department stores began producing house plan books for a wide range of house types and styles. These plan books, which were available through the mail or at lumber yards, had an enormous influence on American domestic architecture and life, providing as they did prescriptions for the design and construction of millions of homes. The illustrations reproduced on the following pages are from just a few of the titles in the Richard Cheek Architectural Plan Book Collection at Historic New England. Dating from the 1900s to the 1970s, the images - from bungalows to ranch houses - depict the richness and variety of American twentieth-century domestic design.

As an architectural photographer specializing in recording the visual history of American architecture, Richard Cheek began collecting domestic design books as a means of educating himself about the buildings he was photographing. In the past fifty-five years, Cheek carefully and systematically assembled one of the finest collections of domestic plan books in the country. It served as the basis for the exhibition Selling the Dwelling: The Books That Built America’s Houses, 1775 to 2000 and its accompanying catalogue at the Grolier Club in New York City in 2013-14. Cheek is now in the process of donating much of his collection to Historic New England.

The Aladdin Company of Bay City, Michigan, began producing ready-cut house kits in the early twentieth century and marketing them to the public through mail-order catalogues. The kits were shipped to the customers, and then the houses were assembled onsite by the homeowner or a local builder. According to the company’s 1921 catalogue (left), these “Built in a Day” homes could be found “in thousands of cities and towns throughout the country.” The Sunshine bungalow (above) presented in a foldout, colored design in a 1919 catalogue is described as “distinctly American in character. …It radiates that sweet, simple home atmosphere everyone wishes to secure in their home. Could a more fitting name than ‘Sunshine’ be given to this home?”

to the

and

as

National

(1913) and

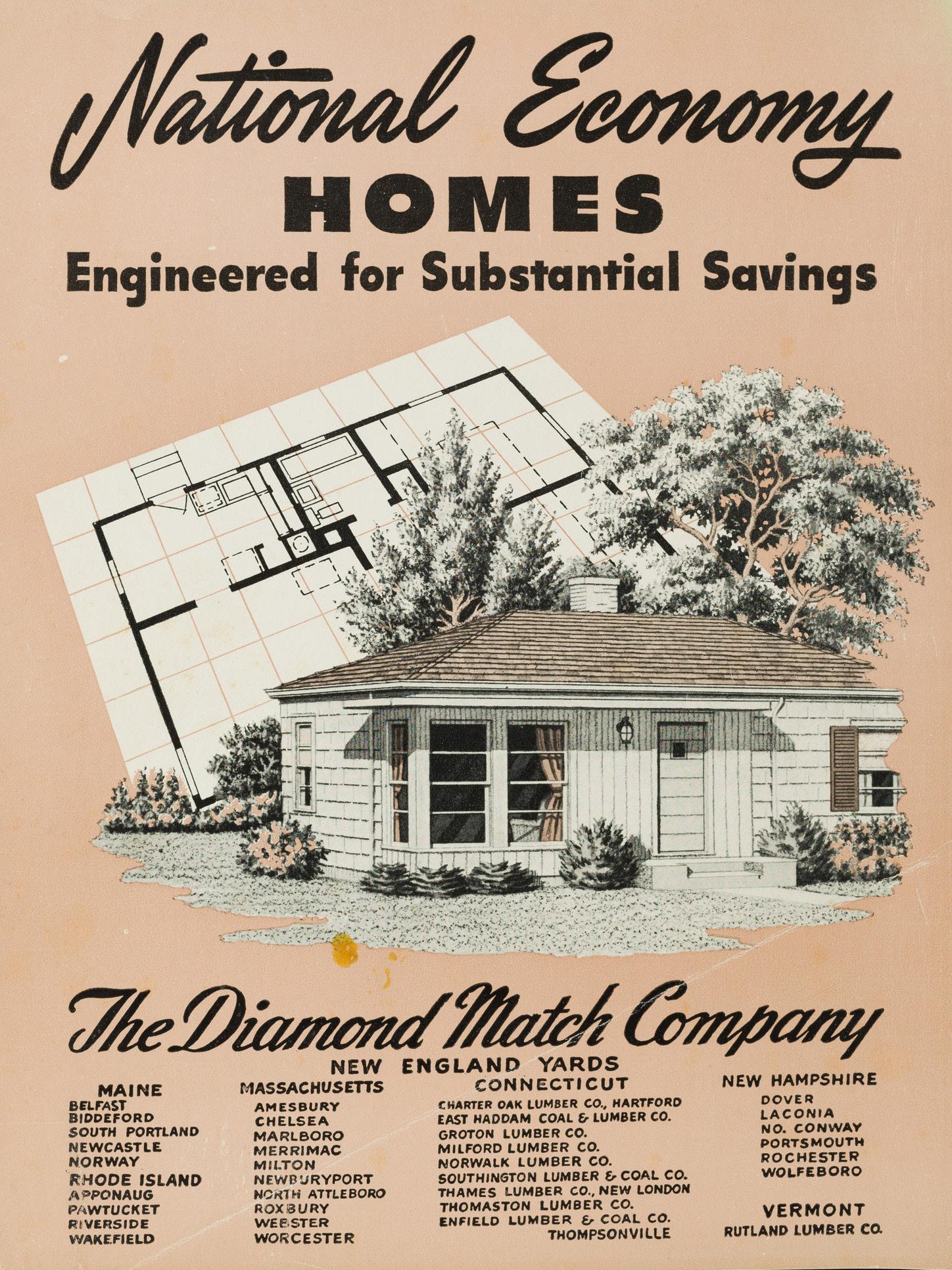

CLOCKWISE Small Homes of Charm (1931) includes plans for houses designed by architects from across the country, ranging from a Cotswold cottage or a Western prairie home to a New England colonial or a French cottage. The cover depicts an idealized stucco English residence with its harmonized materials and landscaping. The Mayflower, the Ponce de Leon, the Concord, and the Rio Verde are the names of just some of the homes offered in Better Homes at Lower Cost (1930). Standard Homes Company of Washington, DC, sold complete working plans for the architect-designed houses at a cost of $20 and promised to deliver them within twenty-four to forty-eight hours. The preface to Popular Cape Cod Colonial Homes (1940s) states, “We are dedicating this book to the popularity of the Cape Cod Home. Born in a setting of economy yet with good taste and a natural symmetrical design, it has kept its attractiveness throughout the years and to-day it is the most popular home in America.” Published in 1949, National Economy Homes provided designs for houses that included all the essentials for good living at low cost. The cover could be custom printed to include the name of only one of the affiliated lumber yards.

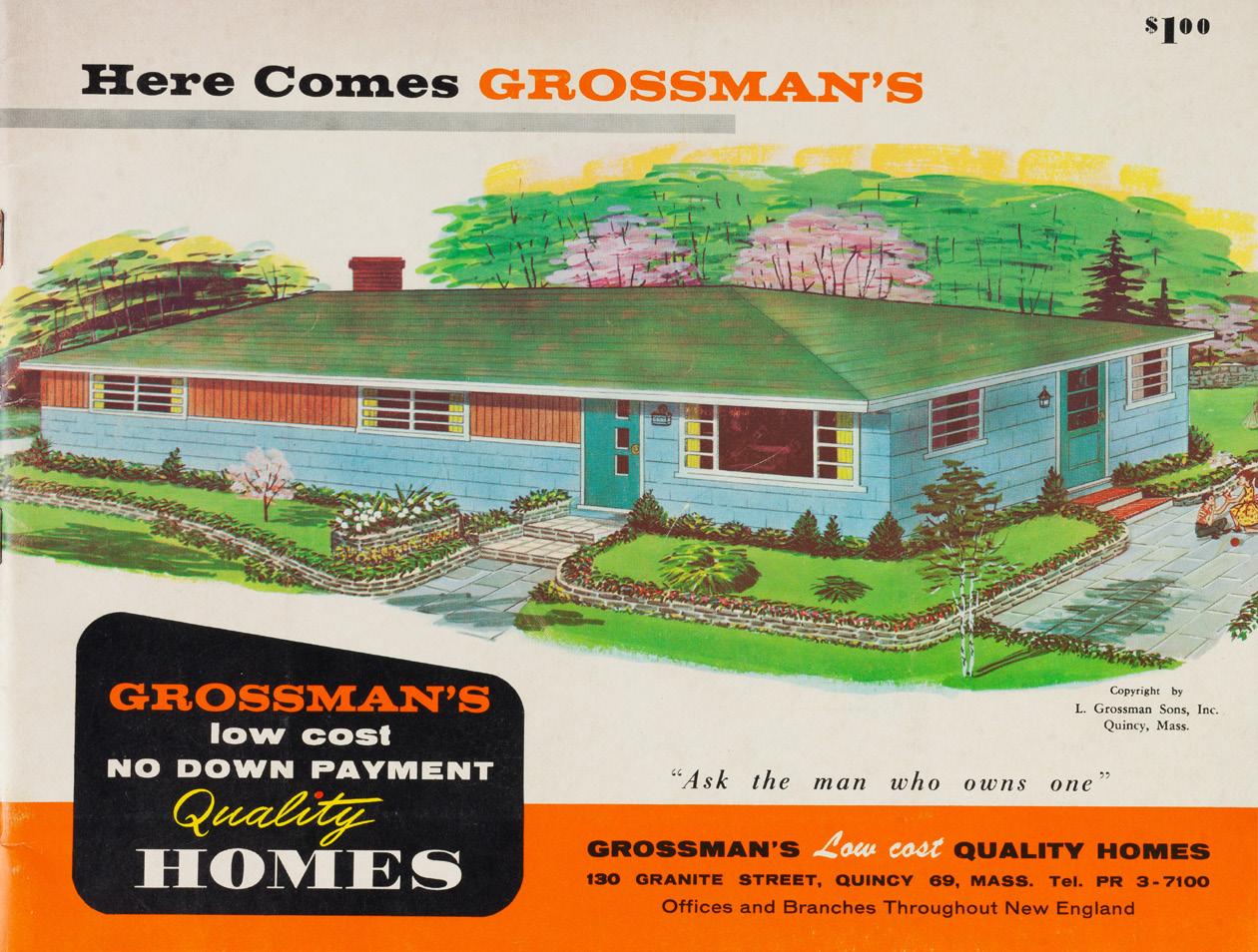

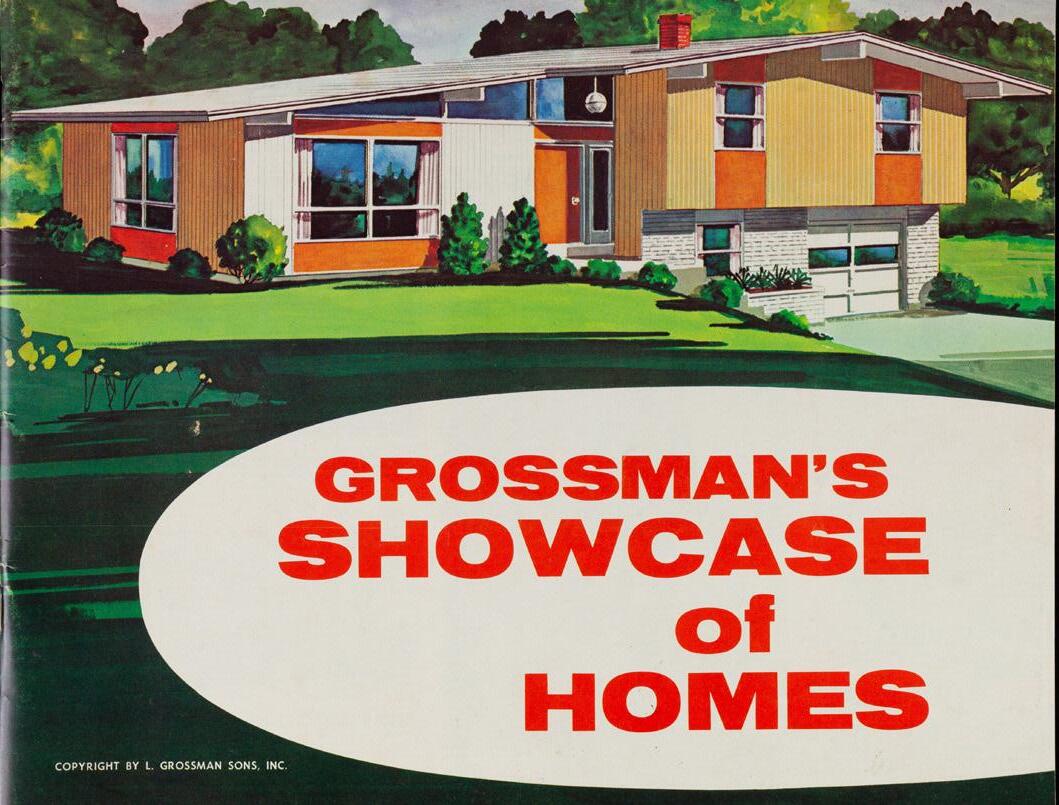

The Grossman Company, sellers of lumber and building materials, began in Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1897 and eventually grew to include branches throughout New England and New York. It also expanded into the home building industry. The plan book (above) from c. 1964 showcases the "Ivy" on its cover. This tri-level home featured cathedral-style ceilings throughout, three bedrooms, two modern bathrooms, and a spacious living room. The plan book includes numerous testimonials from customers throughout New England and New York.

The ranch house, which was available in many different styles, was the suburban residence of choice for returning veterans after World War II. Grossman's offered a rather plain version with a side door to the driveway (bottom left), but a greater variety of modern ranch houses was presented by the Franklin County Lumber Company in Greenfield, Massachusetts, in a plan book prepared by the National Plan Service in 1956. According to this catalogue,"as the homebuyer’s number one modern living choice, the ranch home continues to enjoy the unparalleled popularity gained throughout the years. The factors contributing to its popular acceptance are many. As a result of practical one-story planning, the typical ranch house provides the ultimate in efficiency and livability. It features long, low, rambling lines, a generous use of glass for an abundance of sunlight and ventilation, plus eye appeal that is perfect for town or country." The house shown on the cover is described as "a modern trend exterior with open-plan interior."