For nature to recover, we must make more space for it to thrive. This is why one of our major goals at Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust is to see at least 30% of land and sea protected and effectively managed for nature by 2030. To achieve this, we aim to secure more land ourselves, and also work in partnership with others to transform the way that land and sea is managed so it delivers for wildlife.

In this winter edition of Wild Life, we explore the many different ways it is possible to restore habitats. From opening up swathes of fen at Greywell Moors Nature Reserve to help the recovery of a nationally important wetland (page 8) to restoring vital chalkland in Winchester that could benefit one of Britain’s rarest butterflies (page 11).

On page 18, we introduce our partners and neighbours at our Wilder Nunwell rewilding site: a team of inspirational and pioneering regenerative farmers hoping to prove the wide-ranging advantages of nature-friendly farming.

Wild Life is the membership magazine for Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust.

Registered charity number 201081. Company limited by guarantee and registered in England and Wales No. 676313.

Website hiwwt.org.uk

● We manage over 60 nature reserves.

● We are supported by over 27,700 members and 1,200 volunteers.

Editor Jake Kendall-Ashton Designer Keely Docherty-Lee

Cover image Short-eared owl

© Donald Sutherland

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust is registered with the UK Fundraising Regulator. We aim to meet the highest standards in the way we fundraise.

We then dive into the world of conservation grazing on page 22 and show how livestock animals have an important role to play in habitat restoration on our nature reserves. By bringing a mix of native pony, sheep and cattle breeds onto our reserves to graze freely, it can kickstart landscape-scale conservation by enhancing soil health, improving water quality and increasing biodiversity.

As ever, none of these crucial nature recovery projects would be possible without the unwavering support of our loyal members and supporters. And in such challenging times for us all, we could not be more grateful than we are right now. Thank you.

Debbie Tann, Chief Executive Twi er@Debbie_Tann

Please pass on or recycle this magazine once you’ve finished with it.

You can change your contact preferences at any time by contacting Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust at:

Email membership@hiwwt.org.uk Telephone 01489 774400

Address Beechcroft House, Vicarage Lane, Curdridge, Hampshire SO32 2DP

For more information on our privacy policy visit hiwwt.org.uk/privacy-notice

The best of this season’s nature, including winter bird displays.

Restoring habitats at Greywell Moors and Hook Common nature reserves.

A round-up of the latest Trust news, successes and updates.

15 Give the gi of nature

Treat the nature lover in your life to a wildlife-themed gift this Christmas.

16 Team Wilder

We share the stories of local people taking action to protect nature.

Our latest rewilding reserve sits beside a regenerative farm start-up. We meet the three young visionaries behind it. 22

Introducing the Trust’s four-legged recruits who have an important role to play in landscape-scale restoration.

As intelligent as chimpanzees, these clever corvids are fascinating birds to watch. Here’s where to see them.

Garden writer Kate Bradbury gives tips for helping local wildlife even when our gardens have gone to sleep.

Jack Norris explains how a lifelong passion for agriculture is helping to benefit conservation on our reserves.

The best of the season’s wildlife and where to enjoy it.

Did you know Hampshire has one-third of Britain’s remaining lowland heathland, more than any other county?

Thanks to your support, we’ve been able to protect, restore and monitor internationally important lowland heathland habitats in Hampshire.

As summer fades so does the palate of our heaths. The heathers revert to their dun winter coats after the summer’s blaze of purple. As the days shorten, the bracken and grasses add rusty tones, punctuated by the clean white lines of birch.

Heathlands evolved when wild animals grazed across the landscape, long before they were replaced by people and their livestock. As little as 250 years ago heathlands were commonplace across Hampshire and the Island. Today, much of this wild landscape has disappeared; in fact, we have lost up to 85% of our heathland in the last 150 years.

This precious habitat is threatened by fragmentation and climate change, with more frequent and severe wildfires destroying huge swathes at a time. Thankfully, heathland strongholds exist in the New Forest and north Hampshire, and we are committed to restoring this internationally rare habitat, which is so crucial for wildlife.

Large grazing animals are an essential element of healthy heathland ecosystems and, though we cannot recreate the past, we can find contemporary ways to ensure that cattle and ponies help to restore our surviving heaths to good health. Find out more on page 22.

Hook Common and Bartley Heath

These two adjoining nature reserves in Hook are a fine example of expansive, open, wildlife-rich heathland. Read more on page 8.

Ancells Farm and Foxlease Meadows

Renowned for its variety of flora and fauna among important heathland, this nature reserve near Fleet was saved from development in the 1980s.

Even the briefest of winter walks brings an opportunity to enjoy wildlife.

Trees and shrubs are natural larders, carrying the bounty of summer into winter in their berries, hips and haws.

Resident blackbirds and thrushes are joined by relatives from the continent to enjoy this seasonal abundance. Redwings descend in vast flocks to gorge

themselves on holly and hawthorn berries and other hard fruits.

These visitors are not fussy about the habitat, they will take what they find, be it a country hedge, woodland holly or the landscaping of a council car park.

By spring, every twig will be picked clean and so the birds help the trees distribute their seed.

For nature detectives, winter is a wonderful time. Ground that’s covered in mud or snow is ideal for tracking signs of animals, as it acts like a fresh canvas for studying footprints either found in the wild or in your garden.

When attempting to identify which animal created a track, record the size, shape and the number of toe or claw marks in the print. Taking a photo will also help with identification when back at home.

The Wildlife Trusts website has some useful tips for decoding various animal tracks at wildlifetrusts.org/ how-identify/identify-tracks

Gardeners can support this food supply by choosing what we plant and how we prune.

We can all do our bit by encouraging the people who maintain public green spaces to be mindful of the simple needs of the natural world.

As well as footprints, animals leave other clues of their presence in the wild, such as dung, fur snags and their nests or dens.

It’s also possible to identify the presence of small rodents by examining any nuts they have nibbled. For example, a hazelnut chewed by a dormouse is distinguishable from one that a wood mouse or vole or squirrel has feasted on.

All you need now is a good animal tracks field guide, a magnifying glass and an inquisitive eye!

Animal footprints are much easier to identify in snow.Above: Nuts nibbled by dormice. URBAN FIELDCRAFT

A red squirrel’s rusty coat will brighten up the dullest of winter days. See them at Alverstone Mead on the Isle of Wight.

With its heart-shaped face and ghost-white feathers, the barn owl is one of the UK’s most recognisable birds of prey.

An old country name for this much-loved countryside bird is ‘hushwing’, which perfectly describes its silent, stealthy flight that helps it ambush unsuspecting prey.

Among several extraordinary adaptations this bird possesses, the trailing edge of its wing feathers are covered in soft, comb-like serrations that trap air and absorb noise.

Barn owls also have incredible eyesight specialised for hunting at night, camouflaged plumage and long legs, toes and talons for snaring prey lurking in deep grass.

Their heart-shaped facial discs, meanwhile, help funnel sound into a pair of highly sensitive inner ears that allow the birds to detect tiny movements at ground level.

Winter can be a great time of year to look for barn owls as they often extend their hunting hours into daylight to find the extra food they need to get them through the colder months.

December to February is mating season for foxes. You may hear the harrowing night-time screeches of females, known as the vixen call.

Barn owls can be spotted gliding through farmland, grassland, marshes, fens and cattle-grazed coastal fields, and they will even hunt alongside busy main roads. Generally, the best time to see them is at dawn and dusk on still days.

Hockley Meadows Nature Reserve in Winchester, Arreton Down on the Isle of Wight and Farlington Marshes near Portsmouth are known to attract barn owls – the latter also hosts short-eared owls.

Always remember to watch and photograph birds responsibly by keeping a good distance from wildlife, leaving no trace, and keeping dogs on leads at all times when visiting nature reserves.

These characterful birds produce one of nature’s most remarkable phenomena: murmurations – and winter offers the best chance to see them. These breathtaking aerial stunts see a mass of birds swooping in unison, forming mesmerising shapes in the sky. Witness the spectacle at dusk at Blashford Lakes Nature Reserve.

Up to 25,000 of these striking geese make the 2,500-mile journey from Siberia to the Solent every winter, seeking food and warmer climes. Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve is one of the best places on the south coast to observe them.

As their name suggests, these birds’ distinguishing features are their bright orange-red legs. Redshank feed in shallow water around lakes, marshes, mudflats and coastal wetlands, and Testwood Lakes Nature Reserve is a successful breeding ground for these birds.

Masters of stealth, these predatory birds have evolved many impressive adaptations that make them expert hunters of small mammals.

is special pair of nature reserves in north Hampshire, situated either side of the M3 near Hook, are nationally important for their fen and heathland habitats. Significant conservation works are in motion to support nature’s recovery at both sites. A visit to either reserve o ers the chance to encounter rare and unique wildlife.

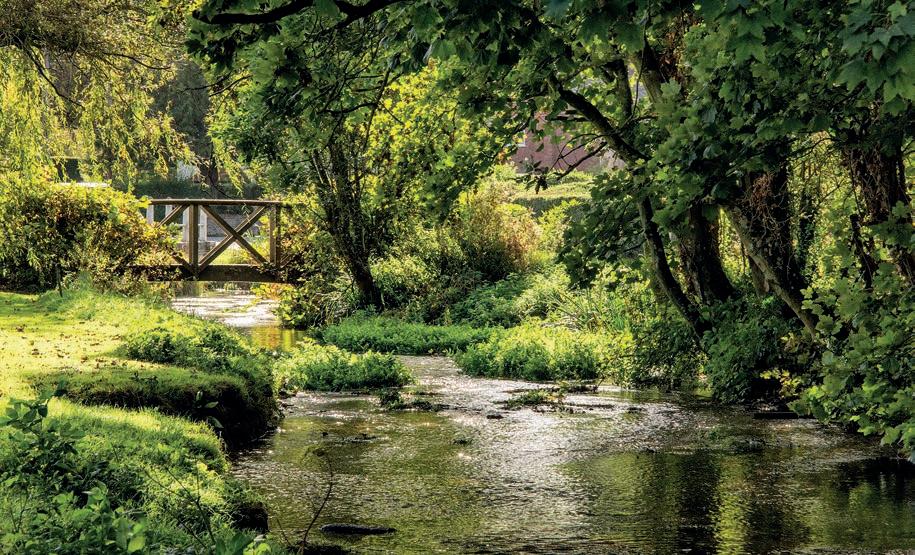

Located on the headwaters of the river Whitewater, the open fen meadows at Greywell Moors Nature Reserve offer nationally important wetland habitat to many species, especially insects and plants.

The fens are fed by a series of springs that form where cracks in the chalk bedrock allow water to bubble up from the aquifer below. These crystal-clear pools support a varied range of nationally scarce plants.

The Trust has recently undertaken extensive habitat restoration work at Greywell to open up even more of the fenland, while a pair of Exmoor ponies are currently free grazing the site to promote floral biodiversity.

In terms of wildlife at Greywell, recent invertebrate surveys found the reserve to be one of the most diverse in the country with a staggering 678 species identified. Incredibly, this represents an increase of over 20% in species diversity when compared to a similar survey carried out

in 2016 when around 550 species were recorded.

A wide range of pollinators are an important part of the site’s rich insect diversity, and Greywell Moors also boasts impressive plant diversity. In some parts of the reserve, it’s estimated there are up to 40 separate plant species per square metre.

Seven orchid species, including southern marsh orchid and marsh helleborine, have been recorded at the reserve in summer. Other flowering plants found at Greywell include hemp agrimony, purple and yellow loosestrife, and marsh valerian. From December, the reserve’s small pockets of woodland host fabulous displays of primroses.

Greywell Moors’ open fenland also attracts an array of birdlife. Stonechats make use of the reedbeds as a winter haven, while kingfishers have expanded their range into the reserve’s open waterways. Hobbies were reported in summer, probably attracted by the plentiful dragonflies by the water, while buzzards and kestrels often hunt among the wooded habitat.

Recent footage showing evidence of nearby otters also raise the hope these water-loving mammals could make use of the reserve in the future too.

Though winter may not present Greywell in its best light, the exquisite and varied fen habitats are sure to offer wildlife highlights year-round.

Comprising two adjoining nature reserves that are designated Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), Hook Common and Bartley Heath Nature Reserve offer a fantastic example of heathland restoration in action.

Lowland heathland is a precious, yet internationally rare, habitat and largescale declines have seen its coverage in the UK diminish by approximately 85% in the last 150 years.

Hampshire is home to a third of Britain’s remaining lowland heathland, and while the majority of that is found in the New Forest, the habitat also has a stronghold in the north of the county.

We’re using the services of native cattle and Exmoor ponies as part of a conservation grazing programme to help regenerate the heaths at Hook Common and Bartley Heath (find out more on page 22).

This has helped control the proliferation of invasive birch scrub and allowed the heather to regenerate, which has positive knock-on effects for various species.

The low-growing and nationally scarce marsh gentian – whose flowers offer a delightful splash of violet blue among the pinks and purples of the heather – can be spotted at Bartley Heath.

Meanwhile, stonechats – a bird often found in heaths – were seen displaying courtship behaviour at Hook Common

this year, a promising sign that’s not been observed at the reserve for a while.

As well as expanses of open heath, the two reserves also boast ancient wood pasture that, during autumn and winter, offer fantastic opportunities for finding fungi, followed by velvety bluebell carpets in spring.

Birds of prey including buzzards, red kites and kestrels use both sites as hunting grounds, while reptiles including adders, grass snakes, slow worms and common lizards, are present on warm, summer days.

A series of former gravel pits at Bartley Heath are now ephemeral ponds that attract lots of dragonfly species plus a range of frogs, toads and newts, including great crested newts. Look out for frog and toad spawn in spring.

Careful restoration of the wildlife-rich habitats at these reserves will continue to support nature’s recovery; it’s fascinating to witness the return of the hum of life.

Location: Deptford Lane, Greywell, Hook, RG29 1BS

what3words reference: ///forklift.whips.scaffold

Parking: Park on the left-hand side of an approach drive to the pumping station on Deptford Lane. Please keep vehicle access to pumping station clear.

Nearest train stop: Hook (2 miles)

Nearest bus stop: Priors Corner, North Warnborough (1 mile)

Reserve size: 13 hectares

Getting around: Public footpath runs through the reserve. Take care when it’s muddy and please avoid the marshy areas as these are sensitive to trampling and can be dangerous to cross. Permit required if you wish to visit the northern part of the reserve.

Location: RG27 9JJ to Hook Cricket Club, for access to Hook Common what3words reference: ///vibes.paces.table (for Hook Cricket Club parking).

Parking: Park at Hook Cricket Club

Nearest train stop: Hook (0.3 miles)

Nearest bus stop: Station Road, Hook (0.3 miles)

Reserve size: 123 hectares

Getting around: Hook Common and Bartley Heath are open access land, and several public Rights of Way and many informal paths cross the site. Take care when it’s wet as the ground can become boggy, and please keep to the obvious paths during spring and summer to avoid disturbing rare ground-nesting birds. For Bartley Heath, there are several pedestrian access points on Griffin Way South and at the car park entrance (car park kept locked with a combination lock – get in touch for a permit if you wish to use this facility).

Acluster of endangered crayfish discovered at one of our nature reserves earlier this year are more widespread than we originally thought, according to the results of our ecological surveys.

The group of white-clawed crayfish – the UK’s only native crayfish species –were found by a team of Trust reserves officers and volunteers within a sanctuary area at Winnall Moors Nature Reserve in January.

Until then, it was thought the crustaceans had died out from the site in Winchester over 30 years ago after a deadly plague wiped out local populations.

Following the remarkable discovery, this summer we carried out four surveys to monitor the crayfish and attempt to determine their relative strength and distribution at the reserve.

To survey them, our expert ecologists check a series of artificial refuge traps

that had been deployed in the water to recreate the cosy shelters the crustaceans seek out.

The crayfish hide inside the submerged traps – essentially a row of connected plastic tubes of varying diameter –which makes it easy to check them for inhabitants.

Once a crayfish has been found, the ecologists record its sex, size, and any signs of damage or disease before returning it to the water – this crucial data helps estimate the strength of the population.

Between 17 and 20 crayfish were found during each survey. This included juveniles, which is a promising sign the group is established at the reserve, as well as an individual recorded in a distinct water channel from the original discovery.

Conservationists have worked for decades to recover the UK’s white-clawed crayfish populations. Nationally, their numbers have declined by at least 70%

Above: Examining a white-clawed crayfish at Winnall Moors

Examining a white-clawed cray sh at

since the 1970s due to pollution, habitat loss and the introduction of non-native crayfish and a disease called crayfish plague that’s carried by species from North America.

Over 10 years ago, the Trust embarked on an ambitious floodplain restoration programme, reconnecting relict water meadow carriers and improving river and stream habitat. This will have increased the amount of preferable habitat for white-clawed crayfish and hopefully contributed to their survival at Winnall Moors Nature Reserve.

Find out more about the Wildlife Trusts’ efforts to support the long-term survival of white-clawed crayfish at hiwwt.org. uk/southern-chalkstreams

Two former areas of nationally important chalkland in Hampshire are set for restoration, which could offer a boost to one of Britain’s rarest butterflies.

The pair of chalk downland sites near Winchester, either side of the M3 motorway, cover approximately 65 hectares.

One of the sites, at St Catherine’s Hill Nature Reserve, has been identified as a potential habitat for the rare, but recently resurgent, Duke of Burgundy butterfly, which is found only in England.

A feasibility study found the St Catherine’s Hill site could not only represent a suitable habitat for Duke of Burgundies but could act as a stepping stone to allow the species to expand its range.

During surveys, our ecologists also

found slow worms and grass snakes on-site, so any restoration work will be sensitive to these reptiles and ensure suitable habitat is retained.

Restoration work is scheduled to start in spring 2023 and is estimated to take 12 months to complete.

Once restored, we hope the sites will help create a larger and much-improved area of connected chalk grassland landscape, addressing the fragmentation and loss of this habitat caused by the construction of the M3 over 20 years ago.

The project will also develop better recreational opportunities for bird watching and allow for sustainable landscape management through conservation grazing.

It has been a bumper year for breeding birds across our nature reserves with several particularly exciting successes.

A pair of redshanks successfully bred at Testwood Lakes Nature Reserve in Southampton. This represents the first time these wading birds, whose numbers have declined significantly in the UK, have bred in the Test Valley for at least 20 years.

At Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve, we saw the best year on record for breeding avocets, with nine chicks either fledging or approaching fledging. Amazingly, this comes only three years after the birds started occupying the reserve.

We hope to see these striking birds’ numbers rise further over the next few years. Meanwhile, more than 26 lapwing chicks fledged at the Portsmouth reserve, and gulls also had an excellent year.

Senior reserves officer Chris Lycett said: “I’m extremely proud to see breeding wader numbers returning to historic levels at Farlington Marshes.

“It’s taken a lot of work to get the habitats here into the best condition for these birds and it couldn’t have happened

TOM MARSHALL

Redshank are named for their bright coloured legs.

The Trust would like to thank Highways England for their funding support through the Network for Nature Programme and making this chalkland restoration possible.

without the dedicated efforts from staff and volunteers.”

Elsewhere, numbers of visiting sand martins increased at Blashford Lakes Nature Reserve, while rare visitors, including a Siberian chiffchaff and a

Caspian gull, were spotted at the site.

In Romsey, at Fishlake Meadows Nature Reserve, we installed an osprey breeding platform in the hope of seeing these majestic birds of prey establish a nest.

Conservationist and TV presenter Megan McCubbin (right) has been named the new President for Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust, with Springwatch co-presenter Chris Packham becoming a Vice President.

The appointments were confirmed at the Trust’s recent Annual General Meeting on 5 November following the retirement of our previous President, John Collman.

Rising television star Megan, who grew up in Hampshire, said: “I am over the moon to be the next President for the Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust.

“I have so much admiration for the fundamental work that the charity carries out - from the reintroduction of key species to their community conservation projects.

“At this critical time, we need all hands on deck to help protect wildlife and their habitats. I cannot wait to get stuck into my new role helping to protect the environment across the two counties.”

well as her TV work, Megan is a passionate conservationist.

Meanwhile, New Forest-based Chris added: “I am delighted to join the superb Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust as a Vice President.

“In our current climate and ecological emergency, organisations such as the Wildlife Trusts are essential, and I am delighted to be part of it.”

early as 5.30am.

For one training session we held in Calshot in the New Forest, several particularly committed people had set their alarms for 3.30am to travel from Portsmouth!

We’re now very excited and grateful to have an amazing team of 30 Solent Seagrass Champions who are trained to survey seagrass meadows independently.

The Trust’s marine officer Ellie Parker said: “The data our brilliant volunteers collect when surveying seagrass and monitoring for flowering shoots is crucial in helping to inform the next stages of our restoration project.”

Alongside the surveys and training, we’ve also been busy sustainably collecting seagrass seeds from the Hampshire and Isle of Wight coastlines by wading and snorkelling.

Having planted over 40,000 seagrass seeds in the Solent in the past year and seen promising signs of new seedling growth, the Trust’s restoration project for this special habitat continues full steam ahead.

During the summer, we delivered a

series of early morning seagrass survey training sessions for teams of dedicated volunteers.

Because the ideal times to survey seagrass, morning low spring tides, were very early, volunteers were required to meet Trust staff on the shore as

These harvested seeds were then transferred to specialised aquariums at the University of Portsmouth in preparation for planting them out in the Solent’s harbours this winter.

We’ll make sure to update you with exciting progress updates.

Assistant reserves officer Ben Pickup completed the London Marathon in October, raising vital funds for Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust.

Ben, who primarily works at our Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve near Portsmouth, completed the race in a very respectable time of 3hr 40mins.

He managed to raise an impressive £1,683 for Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust, smashing his original target of £500, which was then raised to £1,000.

The 25-year-old said: “I’m super proud to have raised money for the Wildlife Trust – all the pain of training and then those 26.2 miles were worth it.

“Having grown up in Portsmouth, the Trust’s Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve was always a place where I had incredible encounters with wildlife, which fuelled my passion for nature and led me towards a career in conservation.

“I hope the money raised will go some way towards keeping our skies full of singing birds and buzzing bees, and our nature reserves free for people to enjoy and to inspire the next generation of conservationists.”

If you’d like to donate to Ben’s marathon effort for wildlife, his online fundraising page is still open at https:// tcslondonmarathon.enthuse.com/pf/ ben-pickup-f8c1a

Beavers have been granted legal protection in England, after the government passed new laws in July this year.

The legislation, which came into effect on October 1st, makes it illegal to deliberately kill, capture, injure or disturb beavers or damage their breeding sites or territories (unless under licence by Natural England).

Eurasian beavers are a native species throughout Britain and were once common before relentless hunting drove them to extinction by the 16th century. Thankfully, conservation efforts have allowed the species to make a remarkable recovery in Scotland and England.

This new legislation gives the beavers already thriving in England recognition as native animals, a status they’ve held in Scotland since 2019.

The Trust has expanded its workforce following the arrival of three Exmoor ponies, whose job description involves helping nature’s recovery.

The ponies – called Flam, Katrin and Doune – arrived in July and have initially been settling into life at the Trust at our College Copse Farm site near Hook. They’ll eventually join our other conservation grazing livestock on our nature reserves where, by grazing freely and selectively browsing certain plants,

they will encourage the development of a varied habitat structure and create the ideal conditions for a range of insects, birds, reptiles, mammals and plants to exist.

One possible destination for the trio is Wilder Nunwell, our new dedicated rewilding site on the Isle of Wight, where they could play a key role in boosting biodiversity.

Find out about the ponies and our wider conservation grazing strategy on page 22.

A pair of glossy ibis were spotted making a rare visit to Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve this summer.

The heron-like wading birds are very infrequent visitors to the UK, usually being found in extensive wetlands in warmer climes such as the Mediterranean.

Yet, assistant reserves officer Ben Pickup snapped the photo (above) through the lens of his binoculars as they fed in a stream on the site near Portsmouth in July.

Though still uncommon in the UK, these ibis are becoming increasingly frequent strays from southern Europe – perhaps a further indication of the effects of climate change.

When autumn approaches, it’s habitat restoration time for Watercress and Winterbournes.

The scheme’s 16 partners are working hard to protect, enhance, and celebrate seven precious chalk streams in Hampshire, with support from the

National Lottery Heritage Fund.

On the Pillhill Brook in Abbotts Ann, low water levels in the summer contribute to algal blooms and a decline in water crowfoot. We’re giving the channel a varied shape that should improve flow in all seasons.

A devoted Wildlife Trust supporter raised over £1,000 for nature after travelling from Norway to cycle around the Isle of Wight’s entire 70-mile coastline on his 60th birthday.

Jo Inge Svendsen, who lived in Arreton for 17 years before moving back to his homeland, returned to the island in June to celebrate his birthday with the fundraising event.

Jo said: “My family and I have very happy memories of living on the Isle of Wight. From the back of our house, we had beautiful views towards Arreton Down Nature Reserve.

“What better way of showing my

gratitude for this beautiful place than by taking some time to fundraise for the Trust and support the very important conservation work carried out by its staff and volunteers.”

The keen cyclist, who set out on his endurance ride at 6am and impressively completed the challenge in under six hours, raised £1,139 in total. Thanks so much, Jo!

If you’re interested in taking on a similar challenge or starting your own fundraiser, then please get in touch with our fundraising team at fundraising@hiwwt.org.uk

In Andover, we’re planning to disconnect a pond from the Upper Anton. Ponds that are connected to a stream often feed it excess sediment and nutrients. Once separated, the stream’s health will benefit and the pond will become a valuable wetland area.

On the Upper Test in Overton, we’re narrowing an overly wide channel that is overheating the stream and causing a build-up of sediment. Thinning nearby trees will also encourage plant growth, thereby curbing bank erosion.

Returning to Alresford for the next stage of our River Arle restoration, we’re managing trees using a coppicing technique called hinging that increases habitat diversity in the stream.

On the Cheriton Stream in Tichborne, we’re enhancing a rebuilt stream channel with woody material; this will provide habitat for wild fish and improve the flow. These restorations are crucial for boosting the health of our chalk streams, and the landowners also have a key role to play. We’re offering tailored group training to give them the additional skills needed to help these habitats thrive. You can express interest by emailing us at winterbournes@hiwwt.org.uk

Our 28,000 members and supporters are at the heart of Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust.

Thanks to you, we’ve had another successful year for wildlife on our nature reserves. We’ve seen breeding avocet at Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve, rediscovered a population of endangered white-clawed crayfish at Winnall Moors Nature Reserve and acquired new land on the Island at Alverstone Mead Nature Reserve and Wilder Nunwell.

Beyond our reserves, we’ve been restoring precious seagrass habitats to help support biodiversity and provide a natural solution to climate change. We’ve also been working with thousands of individuals, schools, communities, and businesses to help make Hampshire and the Isle of Wight wilder.

Despite these successes, nature needs you now more than ever.

We know you love local wildlife as much as we do, and we simply couldn’t protect our precious wildlife and wild places without you.

Now we need your help to get even more people on nature’s side to tip the balance in favour of nature’s recovery. You can do even more to support wildlife by sharing the joy of local nature with your friends and loved ones this Christmas.

Whether they love long woodland walks, searching the sky for birds, or marvelling at marine life, treat someone to a year of discovery with Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust gift membership. With a membership pack to give this Christmas and then regular magazines and updates about our local wildlife throughout the year, it’s the perfect gift for any nature lover, starting at just £27.

For younger nature enthusiasts,

look no further than our Wildlife Watch membership. Membership is £18 and includes a Wildlife Watchers handbook with activities and information on UK wildlife; four magazines per year filled with news, puzzles, competitions and a free poster; a diary covering a year of local events for families and children; wildlife stickers; a Wildlife Watch awards information sheet; and a wild folder to keep it all in. Visit hiwwt.org.uk/shop to find out more.

Looking for something a bit different? How about a gift that helps restore one of our rarest habitats, supports increased biodiversity and helps combat climate change.

Over the next year, we want to plant an additional 2,000+ seagrass seed pods into Solent waters and we need your help. By sponsoring a seed pod for just £20, you’ll be helping us to restore, protect and monitor this precious marine habitat.

As part of the gift sponsorship, the gift recipient will receive a beautiful postcard to commemorate the part they have played in helping to restore seagrass in the Solent.

Plus, they can also sign up to exclusive updates and videos from the team so they can follow the journey of our seed pods.

Visit hiwwt.org.uk/sponsor-seagrassseed-pod to buy your gift today!

Parsonage Farm Nursery and Infant School, based in Farnborough, is one of our Wilder Schools committed to improving its school grounds for wildlife and outdoor learning.

Every school needs inspiring teachers, and at Parsonage Farm, Amanda Whittaker stepped up to the plate to create a buzz for wildlife among pupils.

Mrs Whittaker says: “Back in May, I organised a Science Week for our pupils aged three to seven years old. My aims were two-fold: to get the whole school on board with real, hands-on science and to find out the range of species in our grounds.

“Every afternoon for a week we went out to investigate and tally the species we found. We looked in the pond, in short

grass, long grass, on bird feeders, in the woods, under dried leaves and sticks, under wet leaves and sticks, in insect boxes and bee boxes, on trees and shrubs, and we set mammal runs for our nightly visitors.

“For a week I felt like the Pied Piper of Hampshire with children calling out to me: “Mrs Whittaker, look what I’ve found!”

“The buzz of the week was immeasurable. More importantly, that buzz hasn’t gone away. I have joking ‘complaints’ from teachers now

The Trust is working with lots of communities across Hampshire to make more space for nature as part of the Greening Campaign initiative.

Set up by a community interest company, the Greening Campaign aims to engage local groups in creating a more resilient and sustainable community.

In supporting communities to become wilder and better connected for nature, we can help tackle the biodiversity and climate crises and tip the balance in favour of nature’s recovery.

The ‘Eco Sway’ community in the New Forest are one of many who have

mapped out their local area – with the support of the Trust’s engagement officer, Craig Whitelock – to identify what habitats they already have, and which could be enhanced for wildlife.

The Sway community also asked local members (and their children!) to complete a bee postcard to share what activities they’ve been doing to help make space for nature.

The result was a wonderful tree decorated with a huge variety of wilder actions that had been completed by the community – from creating a hedgehog highway to planting pollinator-friendly plants and building a wildlife pond.

that children are not paying attention – because a tiny fly has just flown in through the window. My job here is done.”

Welcome to Team Wilder, where we share the stories of local people coming together to take action for wildlife.Amanda Whi aker, Wilder Schools Champion Pupils at Parsonage Farm Infant School searching for wildlife.

Hampshire Constabulary begun working with the Trust earlier this year to improve the grounds of their training headquarters for nature.

During the summer, our ecology team conducted a survey of the site with the aim of helping to map the habitats that already exist and providing some recommendations to enhance

biodiversity there.

The police support and training HQ is located among the grounds of Royal Victoria Country Park in Netley.

Currently, the site features areas of grassland and mixed woodland with a variety of mature trees, including oak, ash, beech, conifer, maple, hazel and cherry that have lots of potential for wildlife.

Emma is a PhD student at the University of Portsmouth whose research focuses on the carbon storage capacity of seagrass in the UK.

She began her doctorate studies in October 2020 and, during her first year, she joined her supervisor in working on the Solent Seagrass Restoration Project in partnership with the Trust.

Since then, Emma has been a key part of the project, including switching lab coat for mud shoes and waders to help collect over 20,000 seagrass seeds from the Solent’s coastline. She has also conducted biodiversity assessments of seagrass meadows in the Solent and been involved with the process of maturing seagrass seeds at the university’s Institute of Marine Sciences before planting them back out in designated restoration sites.

Recently, Emma presented her academic research to an international audience at the World Seagrass Conference 2022 in Maryland, United States. Her presentation included reporting on the work of the Solent Seagrass Restoration project.

The results from Emma’s research are

There is also good potential to create wildflower meadows that would enhance areas of open grassland, banks and verges. Through working with us, the police centre hopes to improve the space for nature on its grounds, while also making them more enjoyable for staff and aesthetically appealing for visitors to the country park.

promising in suggesting that some intertidal seagrass meadows, such as those at Farlington Marshes near Portsmouth, can have the potential for net gain carbon storage.

Learn more about our ongoing seagrass restoration project at hiwwt.org.uk/seagrass-restoration

Anyone can become part of Team Wilder. It doesn’t ma er whether you’re an individual, a local business, a school or a community group, as long as you are enthusiastic to help nature. If you’d like to find out how you can get involved, please email wilder@hiwwt.org.uk or visit our website for more information.

This spring, the Trust acquired over 350 acres of land on the Nunwell Estate near Brading on the Isle of Wight to become our second dedicated rewilding site.

Wilder Nunwell is a new type of nature reserve where we’re transforming former intensively managed land into new wildlife habitats as part of our Nature-based Solutions programme, helping wildlife to recover and thrive across the landscape.

What makes this new nature reserve especially fascinating is its location on the estate alongside Nunwell Home Farm, a trailblazing regenerative farm start-up founded in 2021.

Spearheaded by a team of three young, ambitious and entrepreneurial farmers, Nunwell Home Farm aims to prove it’s possible to simultaneously produce food and help nature.

Regenerative (or simply ‘regen’) farming is an agricultural approach that prioritises sustainability and environmental benefits, where soil and water are healthy, and biodiversity is enhanced.

Some suggest it’s a novel, modern concept. Others argue it’s simply a return to traditional farming methods.

Either way, the rise of regen farming seems to be gathering pace and, with high-profile rewilding estates such as

Knepp and Wild Ken Hill now endorsing the practice, its future looks bright.

The Wildlife Trusts believe developing a regenerative approach to farming is key to reversing devastating declines in wildlife, tackling the effects of climate change, and providing good quality, sustainable food for people to eat.

Here, we meet the team behind the Nunwell Home Farm mission, discover what inspired them to start this new farming venture and find out why they’re trying to break the mould of intensive farming.

Our latest nature reserve, Wilder Nunwell, sits beside a new enterprising regenerative farm on the Isle of Wight. We introduce the people behind Nunwell Home Farm and explore how nature-friendly farming can be a reality.

Little more than a year ago, Francesca Cooper, her brother Christy Morley, and childhood best friend Hollie Fallick left behind established careers to take a leap of faith into the unknown.

They now sit at the helm of a pioneering regenerative farm start-up, fuelled by a passion to do better for the planet, and countless hours of research.

The trio assumed management of the 125-acre livestock farm in October 2021, rebranding it as Nunwell Home Farm in the process.

Previously, the site had been run as an intensive dairy farm and then latterly for beef. The new incumbents, however, are prioritising the environment.

“For us, regenerative farming puts soil

health and nature first,” says Hollie.

“We think it’s possible to farm and look after nature at the same time. Some people might say you can only either farm intensively or focus on rewilding, but we believe there’s an option somewhere between the two.”

The team of three grew up on smallholdings and Francesca previously worked as a rural surveyor but, with no direct experience in farming prior to getting the keys at Nunwell, she says they have devoted themselves to extensive research.

“We’ve all been reading books and watching YouTube videos about regenerative farming for so long, we

had so many ideas of what we could do,” she says.

“Putting those ideas into practice in our own context and then seeing how they work has been really exciting and interesting.”

In their short time in charge, the young farmers – aged between 25 and 33 – have already implemented several processes in line with regenerative principles.

This includes ‘mob grazing’ their herd of native Belted Galloways, a practice that mimics the migration of wild herbivores across the African savannah or North American plains.

The technique sees Nunwell’s entirely grass-fed cows regularly moved to fresh

pasture, with paddocks allowed to rest and recover behind them for long periods. This benefits the soil and plant root structure, making the land more resilient during extreme rain or drought.

The farm’s Berkshire-Tamworth cross pigs, meanwhile, are fed a diet of maize, field beans and wheat rather than soya, which is less sustainable as it’s often imported from South America where its production is heavily linked to deforestation.

Like all the animals at Nunwell Home Farm, the pigs live outside year-round. Their natural rooting behaviour – where they nuzzle the ground with their snouts looking for food – turns over the soil surface, which improves the seedbank in the grassland. This will create an ideal and diverse arable habitat for plants like hedge parsley and woundworts to grow. Again, this imitates the habits of wild boars, a keystone species.

The team’s next challenge is to produce soya-free eggs. They have experimented feeding hens with local soya-free mixes, but it had a detrimental effect on egg production.

A willingness to accept that failures like this are unavoidable, though, is part of the challenge.

“It’s important we learn that not everything we try will be perfect from the beginning but to be prepared to keep trialling other methods,” says Hollie

“There are no rules,” adds Francesca. “We are just adapting as we go.”

The chance to work closely with the Wildlife Trust, as landscape management neighbours, is something the Nunwell Home Farm team were incredibly excited about.

“Nature is hugely important to us. Wildlife and biodiversity are real markers that we’re doing the right thing,” says Hollie.

“On a day-to-day basis, it’s very hard to tell whether what you’re doing is working so it’s great to be partnering with wildlife experts who can help us identify the species we have here.”

The Trust’s rewilding plans for the adjacent Wilder Nunwell reserve include creating an area of woodland pasture and allowing scrub to regenerate and form hedgerows for wildlife.

We also hope to help boost the biodiversity of flora and fauna on the

reserve by introducing a mixture of free-grazing livestock onto the site.

There’s also potential to restore a wildflower meadow, and an area of chalkland, which could bring benefits for an array of species.

Launching headfirst into such a bold venture would seem a daunting prospect to many, but Francesca insists they aren’t reinventing the wheel, rather going back to traditional methods.

With more than a hint of avant-garde optimism in her voice, Hollie finishes by saying: “If we can prove, on this tiny piece of land here, that we can improve biodiversity and soil health, plus rewild and produce food, then we’re really getting onto something.”

Earlier this year, the Trust enlisted the services of 10 new staff members. Their job? To get their teeth stuck into some vital conservation work.

Quite literally, they are responsible for nibbling, browsing and grazing the land to encourage habitat restoration and help nature’s recovery.

The enthusiastic, yet semi-feral, new starters are a herd of Exmoor and New Forest ponies, and they have joined the conservation grazing team.

Their ‘CVs’ include thousands of years of relevant experience in improving and restoring areas of heathland, an internationally rare habitat that is found on many of our nature reserves.

The ponies join the Trust’s existing cohort of conservation grazing livestock, including native breeds of cattle and sheep.

Together, the livestock have an important role to play in conserving wilder spaces across our two counties.

Whether it’s by trampling rushes to open up fenland, selectively grazing to allow the regeneration of heather, or breaking up dense grasses to encourage floral diversity in chalkland, deploying livestock as ecosystem engineers can be hugely beneficial for wildlife.

In grazing freely on our nature reserves, they will selectively target different plants to eat, which, over time, allows a healthy and varied structure to form within the habitat.

This encourages biodiversity by helping to create the ideal conditions for a wide range of insects, birds, reptiles and plants to exist.

Read on to find out how we’re harnessing the potential of conservation grazing as a tool for supporting the recovery of local wildlife.

Conservation grazing is the use of livestock to manage land for wildlife.

It’s a natural and effective method that reflects traditional farming practices and mimics the impact that herds of wild, roaming large herbivores would have had.

At the Trust, we use a mix of different grazing animals, including ponies, cattle and sheep to enhance biodiversity at our nature reserves.

Here we explore the specific advantages each type of livestock can provide for nature.

In the past, the scraping and burrowing of wild rabbits would have helped maintain areas of open heathland.

However, drastic declines in the UK’s rabbit population due to diseases like myxomatosis have allowed woodland and scrub to encroach on lowland heath.

A major driver for introducing ponies onto our nature reserves is the restoration of lowland heathland – an internationally rare habitat –and the many species it supports.

The UK has 20% of the world’s remaining heathland, while Hampshire is home to a third of Britain’s lowland heathland, which is more than any other county.

The introduction of Exmoor and New Forest ponies to the Trust’s nature reserves is being overseen by Jayne Chapman, our Senior Nature Recovery Manager.

She says: “Having roamed heathland landscapes for millennia, Exmoor and New Forest ponies are perfectly adapted for maintaining this special habitat.

“Firstly, they are selective grazers and will switch their diet according to the season, which encourages floral diversity.

“The ponies’ teeth are adapted to allow them to graze coarse vegetation like gorse, bramble and thistles that could otherwise overwhelm the heathland landscape.”

Their small, sharp hooves create bare ground and vital edge habitat in heathland, which can support rare invertebrates, birds and low-growing plants.

Another advantage of these semi-feral ponies is they are extremely hardy thanks to a supremely efficient double-layered winter coat that allows them to withstand harsh weather. They also avoid close contact with people, so co-exist well alongside visitors.

Having these charismatic equines on our nature reserves also supports the conservation of two rare, native pony breeds, especially Exmoors which are Britain’s oldest native pony breed.

The Trust currently has New Forest ponies grazing at Hook Common Nature Reserve, plus Exmoors at Greywell Moors. We also have ponies at our Blashford Lakes, Roydon Woods and Winnall Moors nature reserves.

Cattle can be very effective ecosystem engineers when used as part of conservation grazing programmes. Cattle are like bulldozers. They bash through scrub and trample the ground, which removes tall, coarse vegetation and creates bare ground in which wildflower seeds can establish, like cowslip.

Their grazing technique differs from ponies too. Rather than using their teeth, cows pull up plants and grasses with their tongues, which leaves the grass and vegetation slightly longer than when grazed by sheep or ponies. This creates a varied mosaic of plant species and micro habitats for invertebrates.

A wonderful illustration of the benefits of free grazing cattle can be seen at our Hockley Meadows Nature Reserve near Winchester.

Here, a small herd of native British Whites are creating areas of open water meadow beside a tributary of the river Itchen. In turn, this is providing ideal habitat for the rare southern damselfly, an endangered species that only exists in several isolated pockets of the UK.

As well as British Whites, the Trust uses other native cattle breeds across its reserves, including Belted Galloways and Shetlands.

By grazing on grasses that would otherwise become tall, dense and tussocky, sheep encourage a variety of low growing plants to establish within a landscape.

This can lead to amazing benefits for wildlife, especially butterflies in chalkland habitats.

For example, on chalk grassland, sheep promote the growth of horseshoe vetch, which is the sole foodplant for chalkhill blue and Adonis blue caterpillars.

There is, in fact, an extraordinary association between sheep and Adonis blue butterflies. This rare and protected butterfly lays its eggs on horseshoe vetch growing in short, grazed turf. The butterfly’s larvae are then tended by ants, which are attracted by secretions of honeydew. The ants will protect the larvae from predators and parasites until the adult Adonis blue emerges. Without the sheep’s grazing that provides ideal conditions for horseshoe vetch to grow, this complex web of symbiotic relationships would fall apart.

The Trust currently has approximately 230 free-grazing Shetland and Whitefaced Woodland sheep on selected reserves.

Ultimately, successful conservation grazing is about getting the right breeds, in the right numbers, on the right sites – plus, a good dose of expert livestock management.

A one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t

The Trust currently has approximately 200 free-grazing native sheep on selected reserves.

exist. It’s important to carefully consider the habitat, wildlife, climatic conditions and conservation aims at each nature reserve before making any decision to introduce grazing livestock.

Showing our commitment to successfully implementing our conservation grazing projects, we’ve expanded our grazing team to help manage our livestock.

Over time, we look forward to seeing the beneficial impacts these animals will bring to local wildlife and the recovery of nature. For now, happy grazing.

avens are the largest members of the crow family, as big as a buzzard. They were once found across the UK, but persecution reduced them to small populations in the north and west. Fortunately, ravens have made an incredible comeback and can be seen more widely again, though they are still rarer in the east of England and Scotland. They’re often encountered in uplands and on coastal cliffs. You can tell a raven from a crow by its heavier bill, thicker neck, and hoarse, cronking call. In flight, they have a distinctively diamondshaped tail. On winter evenings, ravens gather in communal roosts that can include hundreds of birds. These are often young ravens, as breeding pairs are busy holding their nesting territory. Look out for their tumbling, acrobatic display flights in late winter and early spring.

We’d love to know how your search went. Please tweet us your best photos! @wildlifetrusts

1 Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

Ravens are known to set up home at this expansive coastal nature reserve near Portsmouth. A birder’s hotspot, this reserve comes to life in winter with internationally important populations of wading birds and wildfowl making use of the wetland habitats. Where: PO6 1UN

2 Arreton Down Nature Reserve, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

This exceptionally rich chalk grassland reserve, with panoramic views over the Eastern Yar Valley on the Isle of Wight, hosts ravens throughout the year. The corvids will nest on the down, which is also home to a huge variety of plant and insect species. Where: PO30 3AA

3 Lymington and Keyhaven Marshes Nature Reserve, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

Another vast coastal reserve – our largest nature reserve – that is a draw for ravens with its wildlife-rich saltmarshes and mudflats. Look out for their elaborate courtship displays in late winter as the corvids attempt to attract a mate. Where: SO41 3SE

4 Bouldnor Forest Nature Reserve, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

With a mix of pine forest, heathland, coastal cliffs and seagrass beds, this Isle of Wight reserve is home to a sparkling abundance of wildlife. Among the many birds that visit Bouldnor Forest, including crossbills and goldcrests, ravens build nests here in late winter through to early spring. Where: PO41 0XJ

5 Silent Valley, Gwent Wildlife Trust

An ancient woodland sanctuary in the South Wales Valleys. With panoramic views across the Ebbw Valley, there’s plenty of sky to scan for the distinctive silhouette of a raven. The nature reserve also boasts Britain’s highest beech wood! Where: Ebbw Vale, NP23 7RX

6 Blacka Moor, Sheffield & Rotherham Wildlife Trust

Ravens are a common sight on this spectacular stretch of moorland and woodland, part of the internationally important wild landscape of the Eastern Peak District Moors. As you search for ravens, keep an eye out for the more easily spotted red deer — the UK’s largest land mammal. Where: Near Sheffield, S11 7TY

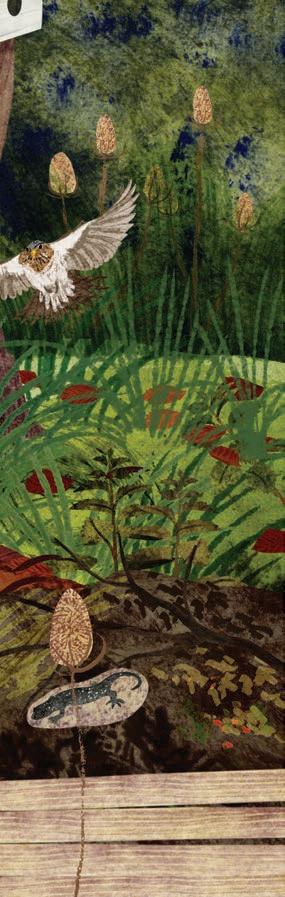

Our gardens all but go to sleep in winter, as plants become dormant and most species are overwintering, but there are still ways to help your garden wildlife.

Hedgehogs and amphibians may be tucked beneath a large pile of leaves or in your compost heap, while insects may be sheltering beneath tree bark, in the folds of spent leaves and

seedheads, or amongst leaf litter. Avoid disturbing these habitats until mid-spring as any interruptions could cost valuable energy that isn’t easy to replenish at this time of year; insects may also be vulnerable to fungal diseases if exposed to damp conditions. Indeed, the best thing you can do for most wildlife at this time of year is to not

garden at all! Leave plants in borders to rot down into themselves, avoid clearing leaf litter from your garden’s edges (but do sweep leaves off paths and the lawn), and leave habitats such as log piles and compost heaps intact. If you have a meadow or other area of long grass, leave a ‘buffer zone’ uncut throughout winter, so caterpillars, beetles and other invertebrates can shelter in the thatch.

Of course, not all animals hibernate. Birds battle through the short days and cold nights, searching for food that’s often hard to come by. If you have fruit trees, like crab apples, let windfall fruit remain on the ground so thrushes such as redwings

Kate Bradbury is passionate about wildlifefriendly gardening and the author of Wildlife Gardening for Everyone and Everything in association with The Wildlife Trusts.and fieldfares can help themselves. If the ground isn’t frozen, you can add to your collection of fruit and berrying trees. Now’s the time to buy bare-root trees and shrubs — hawthorn, rowan, holly, apples, crab apples, and pyracantha all produce fruit loved by birds, while birches and alder, along with plants such as Verbena bonariensis, lavender and teasels, offer seeds for a wide range of smaller species.

Filling supplementary feeders benefits smaller species like tits, which need to feed almost constantly in the daylight hours. Calorie-rich food such as fat balls, sunflower hearts and peanuts gives them the energy they need to shiver to keep warm at night. Leave scraps of seed at the back of borders for ground-feeding species like wrens. And don’t forget water — not only do bird baths provide drinking water, but by regularly topping up your bird bath

you will also help birds to clean their feathers and regulate their temperature, vital on cold winter nights.

Do make sure you keep bird baths and feeders clean, as the number and variety of birds visiting them can spread diseases. Regular cleaning can help keep your garden birds healthy.

Get more wildlife-friendly gardening tips at wildlifetrusts.org/gardening

Senior estates manager Jack is responsible for managing the Trust’s successful conservation grazing operation. Here, he explains how growing up in the Peak District sparked a passion for wildlife and agriculture and why his role perfectly combines both to benefit nature.

I’ve wanted to be involved in agriculture my whole life; I like the physicality of it.

I grew up in the Peak District and though I didn’t grow up on a farm, all of my friends and neighbours had farms, so I used to help out a lot. When I was 11 years old, I bought my first two sheep –a pair of rare breed Hebrideans – and my flock grew from there. Eventually, I went on to own a flock of 200 Lleyn and Texel sheep.

Before joining the Trust, I studied for a degree in agriculture at the University of Nottingham, and then worked on a 7,000-acre organic estate in the Cotswolds as a shepherd, where I was responsible for looking after 2,500 breeding ewes and 300 cattle.

I’ve worked for the Trust for nine years now in all, over two separate spells. I was initially employed as the first stockman at a time when the grazing

team comprised of just one part-time farm manager, myself and 13 cows. In comparison, today we have five full-time members of staff in the grazing team and, of course, a lot more animals to look after.

My role now largely focuses on coordinating the conservation grazing operation for the Trust. I have to work out which of our livestock animals are grazing where and when. We have around 250 cattle and 200 sheep and over 60 different

sites that they could graze on, so there is lots of logistical planning involved.

It’s important for me to liaise with our reserves officers as they have the ecological knowledge of our reserves and know what the ideal scenario is for achieving conservation goals. From those conversations, I will then devise a year-round plan that fits into our livestock breeding programme and animal health.

Conservation grazing is vital for delivering our conservation objectives at the Trust. When you have landscapescale projects, the impact of grazing animals is so important, and this couldn’t be replicated with machinery – it would come at a huge financial and carbon cost and would also be less efficient. Another benefit is that livestock animals help create a more robust ecosystem that supports all trophic levels.

My favourite part of my job is lambing and calving season – when it’s going well. There’s something very special

about bringing new lives into the world, especially if there’s a problem – like a calf or lamb getting stuck during birth or supporting an inexperienced mother –and you can solve it. It’s very rewarding to know you’ve saved a life. Of course, on the flip side, when things don’t go to plan and you lose an animal it can get quite emotional because you care about them and are so invested in their welfare.

I also really enjoy working for the Wildlife Trust because it brings a feeling that you’re actively benefitting conservation and wildlife. And though I’m not saying how we manage livestock is how all farmers should do it, I hope what we do can act as a demonstration of successful landscape-scale conservation.

One of the biggest challenges in my role, I would say, is the logistics of making sure we comply with various schemes and government regulations. A lot of what we do is governed by TB testing, for instance, and the labour involved with

that is phenomenal. And with the Trust having so many nature reserves where our livestock can graze, it can be like having 60 farms to think about at once.

The future of conservation grazing and wildlife-friendly farming hangs in the balance depending on what the government decides for the future of agricultural environment schemes. It is worrying times because if they abandoned funding for active conservation on farms and bring back area-based payments, which are paid irrespective of food production or conservation value, it would significantly affect operations like ours. We would need to raise additional funding from our supporters to ensure we can continue our conservation grazing programme. However, if the government is genuinely committed to conservation, then I see conservation grazing has a good future with lots of opportunities.”

Getting to know individual animals, like this Hereford bull, is key to Jack’s role.

“With the Trust having so many nature reserves where our livestock can graze, it can be like having 60 farms to think about at once.”

If you’re looking to treat the nature lover in your life, the gift of membership to Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust could be the perfect present. It truly is the gift that keeps on giving!

Whether they enjoy the brilliance of birds, the marvel of marine life or the intrigue of insects, there is so much wildlife to discover all year round across our two counties.

The recipient of your gifted membership will receive: ✱ A welcome pack to open for Christmas (if ordered by December 16) ✱ Our 200-page nature reserve guidebook ✱ Three issues per year of our member magazine

Family members also receive junior membership, which includes the regular Wildlife Watch magazine for kids.

Membership starts from £27 per year. The support from your gift helps us to protect wildlife and wild places, while bringing your loved one a year of unforgettable memories. Contact our membership team on 01489 774408 or visit