Paradeisos

Reconciling Man and natuRe dia 2017/2018 HoPeton Bartley

1st advisoR RogeR Bundschuh 2nd advisoR JoRis Fach

Table of Contents

introduction ...........................................................................................4 God‘s Garden............................................................................................7 Paradise.......................................................................................................9 ancient MesoPotaMian Gardens.......................................................23 nostalGic Man 32 develoPinG a ProGraM 47 site History and data 64 site drawinGs...........................................................................................74 BiBlioGraPHy.............................................................................................79

introduction

Given the perspective of the theological and scientific schol ars, man has two basic origins. The theological view denotes that man is created by a supernatural being, which places him within the Gar den of Eden among the trees and the animals1 the academic view denot ed by Darwin states that man evolved from the grass planes of the savannah2. These two, although completely different narratives, both have its origins set firmly in the natural environment. They both, either metaphorically or unerringly summarise man’s first interaction with nature. It was his home, his food, the source of his clothing and shelter. However, since the dawn of civilisation, the growth of cities has stagnated man’s relationship with nature within the urban environment. Needless to say, despite the intertwined history of man and nature, and man’s growth, the society on a whole has meandered away from its origin.

The estranged relationship between the growth of the city and the natural environment has so far frequently brought mankind misfortunes. This estrangement has somehow led society into thinking of nature and man as binary opposites, which consequently leads to a blatant disregard for the natural environment and by extension human health and development. Within our cities, nature has retreated itself, to the seldom appearing park or green patch in front a public building3. Despite the decline in natural elements within the city, individuals spend copious amounts of money to add little splashes of colour in front of their homes regardless of social or economic status4. It is immensely difficult to express the value of nature in strictly rational terms, as much of its virtue lay simply within the immateriality of its existence.

Throughout millennia, landscapes and fauna have been the subject of enthusiasm for songs, poems, stories and paintings5. These scenarios provide evi dence that nature is important in and of itself, rather than solely extrinsic reasons. Yet, one cannot deny the extrinsic value of nature to human lives and existence, and the pivotal role it plays in health and the comfort of living.

1 Gen. 2:4-25 Revised Standard Version

2 (Shreeve, Sunset on the Savannah 1996)

3(Kaplan 1989)

4(R. a. Kaplan 1989)

5(R. a. Kaplan 1989)

Hitherto, the development of the archetype of the city have seemingly isolated itself from that of the natural environment, the results of this has man ifested itself in a myriad of psychological, sociological and environmental ways, each having severe repercussions on how, or if mankind is able to continue de veloping as a race. Research in the United States of America shows that a century ago, the likeliness of someone suffering any major form of clinical depression was approximately 1 percent; however for the past century, those statistics have risen to approximately 19 percent. This tremendous spike denotes a 2000 percent increase in the rates of depression within only 100 years6. Research has purport ed that the risk of depression and other psychiatric ailments are a side effect of urban life7. Be as it may, studies have shown how green time can be an important remedy for reducing the effects of depression within affected patients8. Wolf (2010), also states that depression among patients were decreased by 71 percent when exposed to walking through vegetated areas, this was then compared to the 45 percent decrease for people who went on walks in a built environment. These findings therefore could be used to argue that being exposed to nature can greatly reduce the feelings of depression. Additional research also shows that in teraction with green spaces can lead to a reduction in dementia, attention deficit disorder, and improve cognitive performance9.

Consequent to these findings, it will be important to categorically access the role that nature plays throughout the course of human civilisation. It is par amount that one has an informed assessment of the pass before he makes any plans for the future. Subsequently, very specific topics will be studied in order to provide a narrative and logic for the presented architectural model. Firstly, an examination of the Edenic text and imagery will be undertaken to carefully understand its connection with the model of paradise; how it is represented, described and understood within antiquity. Secondly, an in-depth analysis of the

6 (Baber 2011)

7 (Dan Blazer, MD, PhD; Linda K. George, PhD; Richard Landerman, PhD 1985)

8 Wolf, Kathleen. 2018. “Mental Health :: Green Cities: Good Health”. Depts.Washington.Edu. https:// depts.washington.edu/hhwb/Thm_Mental.html. (accessed October 31, 2017)

9 (Wolf, Green Cities: Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

representation and socio-political importance of the garden typology in the first civilisations, specifically Mesopotamia. These models will be studied and anal ysed with keener attention being placed on specific case studies of the Hanging Gardens and specific royal gardens throughout the region. Lastly, an exploration of the biophilic relationship between man and the natural environment will be done. With the culmination of prior studies and the undertaking of this research, it is anticipated that a model which can intuitively be applied to developing an architectural language will be derived.

The importance of nature to humans is something that is well known, but has been rarely studied empirically10. This study will seek to analyse those av enues in an attempt to explore architecture as a restorative and medicinal art. The importance of the natural environment to humanity is existential, and human beings are 100 percent dependent on it for light, food and oxygen. Subsequent ly, empirical evidence has shown that the key to man’s contentment is found through his symbiosis with nature. It was here in the ‘natural realm’ that man was born, and it was here human bodies and brains evolved, and consequently where man belongs, and performs their best.

“Your deepest roots are in nature. No matter who you are, where you live, or what kind of life you lead, you remain irrevocably linked with the rest of creation.”

GOD‘S GARDEN

The Lord God planted a garden In the first white days of the world, And He set there an angel warden In a garment of light enfurled. So near to the peace of Heaven, That the hawk might nest with the wren, For there in the cool of the even God walked with the first of men. And I dream that these garden-closes With their shade and their sun-flecked sod And their lilies and bowers of roses, Were laid by the hand of God. The kiss of the sun for pardon, The song of the birds for mirth, One is nearer God‘s heart in a garden Than anywhere else on earth. For He broke it for us in a garden Under the olive-trees Where the angel of strength was the warden And the soul of the world found ease.

Paradise

The Garden of Eden is a long sought after treasure, countless people have dedicated their lives to find this earthly incarnate of paradise. Throughout the history of theology, man’s existence and origins have been linked exclusively to the Garden of Eden. However, much of this belief lends itself to the borrow ing of the ancient Mesopotamian religions11. Consequently, Paradise has been strongly linked to the concept of Eden. Throughout scriptural text, The Garden of Eden and Paradise are used synonymously.

“After Time had come into being and the holy seasons for growth and rest were finally known, holy Dilmun, the land of the living, the garden of the great gods and earthly paradise, located eastward in Eden, was the place where Ninhursag, the exalted lady, could be found”12

The Garden of Eden within in the ancient Mesopotamian mythology is called the garden of the Gods. In the quotation above, it is seen how it is used to illustrate an earthly home for the Sumerian Deities, and this is perhaps the first use of the word ‘Eden’. Consequently, the Mesopotamians saw the gardens as a holy place of significant theological importance. It was their belief that man originated; also from these gardens where he once lived among his creators in harmony13. Thus, these stories bore fruit to man’s thereafter fascination with the garden. Later this belief was passed over into Judaism, Christianity and the Islamic religions which begun to expand the description of the Garden of Eden. Within the Abrahamic religions, it can be observed how man has definitively coupled the ideology of the garden with paradisiacal nature.

“The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and keep it”. Genesis: 2: 15

11 (Buck, Paradise and Paradigm 1999) (Kvanvig 2011)

12 (Lyons 2018)

13 Sitchin, Zecharia. Genesis Revisited: Is Modern Science Catching Up with Ancient Knowledge?. Simon and Schuster, 2002.

Though this chapter, a wise advice is observed, that is, to work and keep the garden. The verse can be further scrutinised, to hypothesize that this could easily be some form of primordial instruction that would assure our survival.

Theologians believe that it was because of this mythological relation ship between God and the garden that resulted in the Garden of Eden, often being just called paradise. The Greeks borrowed the Persian word, paradeisos, for an enclosure, a garden, an orchard, and for paradise and later the Garden of Eden14. The English word, paradise is believed to derive from this Persian word, which literally translates to walled park15. For this reason, we can see the strong correlation and salience placed on the garden as a paradisiacal entity. Resultantly, scholarly writings have continually tried to decode the concept of the garden in Mesopotamian cultures. Mesopotamia is the birthing place of civilisation and so it would seem logical as to why that the romanticizing of the garden started here and was carried over into Middle Ages and then to modern days.

“And the Lord God had planted a paradise of pleasure” Genesis: 2:8

Subsequently, by the 17th century, the belief in the existence of the Gar den of Eden had begun to decline, and it was replaced by man’s nostalgia for a mythological paradise16. Paintings of this era showed Eden as a paradise of lush plants, animals, streams and of course, man.

14 (Dalley 1993)

15 Dalley, Stephanie. “Ancient Mesopotamian gardens and the identification of the hanging gardens of Babylon resolved.” Garden History (1993): 1-13.

16 (Delumeau 2000)

Edenic imagery can be a truly stimulating to view, and by default lends itself to any infallibility credited to it. It portrays an individualistic interpretation of paradise based on the subjectivity of the artist, time and region; justly, this same infallibility lends itself to reflexivity17. The paradigm of paradise is deeply associated with semiology, and so it makes it all the more interesting to decipher the allegories of Edenic Imagery.

As seen in the early paintings of paradise, Eden is an evergreen oasis of lush plants and fauna. Within paradise, man cannot age, and there was no evil, at least not until Eve’s transgression18. The imagery of Eden has also shown the simplicity of paradise; it is not gold incrusted, nor does it have intricate orna mentations, however its paradisiacal value lies within its immateriality. The para dise as depicted by Edenic imagery is a simple referral of the intrinsic beauty and detail naturally existing within the world. Edenic imagery creates and interesting dialogue between the world of man and metaphoric paradise. Throughout most images of Eden, we constantly see water illustrated throughout and sometimes bearing as much significance to the image as the flora itself. This is as a result of, a great portion of fauna also existing within the water, as well as its vital relation ship with the existence of life.

According to the Old Testament, man, after consuming the apple, lo cated at the centre of the garden, became aware of his nakedness, and thus, banished into the world of the mortals, where he would now age and have to toil for his food and survival. These stories provide an allegory for the transition of man from his unaware state and place among nature19, into civilisation and knowledge. This represents the theological transition of man from the wild into prehistoric civilisation. Since then, man has sought to recreate paradise in his new world, the garden.

“Therefore the LORD God sent him forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from whence he was taken.” Genesis 3:23

17 Buck, Paradise and Paradigm, 1999

18 Gen. 3:6 King James Bible

19 Gen. 3:23 King James Version

In this painting from Cole, the Garden of Eden is pictured as an idyllic open space full of colours and vegetation. The lighting of a sunset creates a romantic and warm glow on the scene and colours of the water reflects a soft orange tint - not blue as typically seen in representation of water in art. The Garden of Eden is here represented as a forest, full of trees, plants and flowers, as to create a sense of peace and harmony of man with nature. Two human fig ures, Adam and Eve, are in the background of the scene and they appear only a little larger than blades of grass. The focus of the painter is on the river, where the attention to colours and details are at their finest. This painting, unlike most, does not put extreme focus on the humans, but instead on the garden; thus il lustrating a scene where Adam and Eve are as much a part of the garden as the trees and water. Around the water he concentrates all the visual elements that communicate the vitality and prosperity of the Garden of Eden. The precious stones gleam to show the wealth of Eden. The Garden of Eden is represented as a space full of life, where Mother Nature grows undisturbed and uncontrolled. This piece communicates vividly the homogeneity and prosperity of Paradise and the symbiosis with Adam and Eve.

11 The name of the first is the Pishon. It is the one that flowed around the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold.

12 And the gold of that land is good; bdellium and onyx stone are there.

13 The name of the second river is the Gihon. It is the one that flowed around the whole land of Cush.20

Breughel and Rubens artist illustrates a strong religious narrative of para dise, with the theological and biblical elements well exposed in the painting. Here, we see in contrast the representation of water as a blue hue, as opposed to the orange we saw in the work by Thomas Cole. The light is soft, and we can clearly see the human body juxtaposed against the dark hue of the trees. This composi tion of Eden appears far more anthropocentric, and the humans themselves are set right below a massive canopy. Successively, we can see the clusters of trees stretching the entire length of Eden. However, in this painting the focus is on the two human figures in the foreground, and nature is part of the background and becomes the scenography of the represented composition. Overall the light spread through the painting as to give a sense of joy and happiness, typical of paradisiacal views. The water, a strong iconic element in the creationist descrip tion of paradise, is here not of primary importance, instead the focus is Adam and Eve in the act of eating the apple. The refinement and accuracy with which the artist rendered flowers and plants shows the interest on communicating the beauty and perfection of the Garden of Eden.

Thomas Cole, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden 1828

This piece is a continuation of his previous painting “The Garden of Eden”. In this painting the similar type of stylistic emphasis is placed on the landscape. Here he shows a stark juxtaposition of Paradise and the world of man. On the right, we see lush various types of trees, well-lit and the ubiquitous involvement of water, unlike his other, which focused on the image, this com position focuses on the narrative. Interestingly, at first glance it is not so clear exactly where Adam and Eve are in the composition. However, based on the use of light our eyes are pulled towards them at the mouth of the portal separating paradise and the world of man. Contrasted by the lush of tropical vegetation on the right, the left is desolate and dystopian. Towards the bottom left we see a predator which represents the harshness and unpredictability our world. Looking at the bottom right, it appears to be the same river from his previous painting. Water is used here also as the element thrusting Adam and Eve out of the Gar den. This symbolically represents the power of water and its duality as both life giver, and a force of destruction.

water and eden

As seen in a majority of Edenic imagery and text, water is a crucial as pect of Paradise, not only as a means of giving life to the garden, but also as a holy symbol and point of respite21. In Thomas Cole’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden, he replaces the cherubim22 which drove Adam and Eve out of Paradise, with a gushing tsunami. In all other depictions of this act, it is a Cherubim who removes Adam and Eve from the garden; this therefore exemplifies water as a divine element capable of acting as a symbol of a higher power. According to both biblical and Mesopotamian theology, the Lord called for the water to rise and nourish the land, and consequently life was given to Eden. This text further denotes water’s purpose to the Eden model. Lastly, the placement of the four rivers in the bible helps create a datum point for the garden and is one of the very few geographic descriptions that are given in Genesis23.

“Enki (a Mesopotamian god) then summoned Utu.Together they brought a mist from the depths of the earth and watered the face of the ground. Then Enki created rivers of fertile sweet waters, and he also devised basins and cisterns to store the waters.”24

(Translation of Sumerian Text)

“but there went up a mist from the earth, and watered the whole face of the ground.”

Genesis:2:6

21 (Creagan, Water as blessing: recovering the symbolism of the Garden of Eden through Ezekielfor Chris tian theology – a theological investigation ,2012)

22(Gen. 3:24 Revised Standard Version)

23(Gen. 2:1-24 Revised Standard Version) 24 (Hagin n.d.)

ancient MesoPotaMian Gardens

ancient MesoPotaMian Gardens

tHe Gardens of MesoPotaMia

The Mesopotamian civilisation was believed to be a direct follow up of man leaving the Garden of the Gods. Consequent to their nostalgia for their lost paradise, they sought to recreate earthly paradises throughout their entire cities.

Man first settled in civilisations approximately 5000BC. However, even in these early settlements, man still yearned for the green25. Ancient Mesopo tamians romanticized the garden, it being the home of their gods. To the peo ple living in these arid regions, the garden was an oasis of flourishing aromatic plants, sweet fruits and vegetables; it offered an area of lull within the otherwise inhospitable environment26. The region had very little rain and lay between the rivers of Tigris and Euphrates, there was very little choice but to use the available rivers to irrigate the lands thus providing the shade and vegetation needed to make the lands liveable and fertile27. As such, one who possessed the skills and knowledge to do so was of high importance, both politically and sexually, as he would represent the fate of their civilisation.

tHe royal Gardens

The Assyrian kings developed the idea of magnificent parks, the concept of their artificial paradises were substantial to their city planning programmes and the tradition was continued by all successive dynasties until the middle ages28 Despite the extravagance of these gardens, not all gardens were privileged to this meticulous treatment; gardens along rivers and sides of roads were very simplistic.The royal gardens on the other hand boasted extravagance and os tentatiousness; it was comprised of high plant diversity, animals (lions, falcons), and pavilions, well terraced and in many cases artificial lakes29. Although, the main purpose of the royal gardens served for pleasure and relaxation, it also served as an economic means to provide the royal household with food.

25(Dalley 1993)

26(Novak 2002)

27(Novak 2002)

28(Novak 2002)

29(Dalley 1993)

The royal gardens was a place of absolute splendour and pleasure, however one of the most iconic installations were the Universal Gardens by Ti glath-Pileser (1114-1076BC) 30. According to his inscriptions, he brought plants from all over the world and decided to cultivate them within his specially de signed Garden. The result of this was other Kings attempting the same feat, and each time in even greater magnificence, one of which was Assur-Nasir-Apli II (883-859 BC). Assur-Nasir-Apli II’s garden was called Kiri-Risate “The Garden of Pleasure”, it consumed 25 km2, adorned with 41 different breeds of trees and wild animals to amaze the public. Since, his palace was to the west of the citadel, the rooms were allowed to open up to the Tigris and the Garden. As a result, the westernmost rooms were given access to a panorama terrace which later became a substantial aspect of Assyrian architecture31. This feature played an integral role in the future relationship of Mesopotamian architecture, and then successive dynasties and empires that wold try to assimilate a similar aesthetic.

30(Novak 2002)

31(Novak 2002)

tHe Garden of carnality

Within their society, the garden had a strong sexual connotation, that of fertility, and was often a place for romantic affairs to take place because of its cool and relaxing atmosphere32.The temple gardens, hence, because of its beauty and tranquillity, became the place for the marriage ceremonies between the King and the Priestess, and based on the love lyric of Nabu, one can deduce that also love making took place here33

The societal impact of the garden also affected the ideology of their monarchy; with one of the characteristics of a good ruler being that of a skilled gardener34. A thriving garden was the result of hard and relentless labour and thus, represented the characteristics of a perfect male specimen and ruler within their society35. The ability to make these arid lands fruitful became a symbol of virility. Thus, the sexual connotation of the garden became a source of much po etry and literature making it susceptible to metaphors involving the male and fe male reproductive system. The vulva therefore was often described as “well-wa tered lowland” which should be ploughed (a euphemism for the phallus)36. In a common erotic poem, a woman would sing;

“Do not dig [a canal], let me be your canal, do not plough [a field], let me be your field.

Farmer, do not search for a wet place, my precious sweet, let me be your wet place.”37

Consequent to these texts, it was revealed that within the Babylonian and Sumerian society, the male lover was often referred to as a gardener. 32 (Novak 2002) 33(Dalley 1993) 34 (Novak 2002) 35 (Novak 2002) 36 (Novak 2002) 37 (Novak 2002)

tHe courtyard Garden: utilitarian & intrinsic value

The Mesopotamians were passionate about recreating their version of paradise within their cities 38.The earliest case of the Mesopotamian gardens oc curred around the 4000BC39. The gardens were stated to be man’s refuge from the harsh coldness of the city as well as the dangers of the untamed nature40. As such, the internal courtyard became a safe place away from marauding pigs, thieving ragamuffins and the hot sun41. The Mesopotamians saw the garden as a utility, as well as an entity of its own intrinsic definitive importance. It became a place for brunch, as well as just a place of unparalleled holiness. Poetry was writ ten about their need and love for the green, as both a utilitarian purpose (catering to man’s basic needs of food shelter and clothing) and the immaterial aspects of plants on the society42.

In a popular Babylonian piece of literature, a tamarisk tree and date palm are personified having a discussion. They resultantly discuss and argue their importance to the garden, their use, and their share beauty, each rebutting by expressing more and more personal grandeur. This piece illustrates the share importance the society placed on flora.

38 (Dalley 1993) 39 (Dalley 1993) 40 (Dalley 1993) 41 (Dalley 1993) 42(Dalley 1993)

“The king plants a date-palm in his palace and fills up the space beside her with a tamarisk. Meals are enjoyed in the shade of the tamarisk, skilled men gather in the shade of the date-palm, the drum is beaten, men give praise, and the king rejoices in his palace.

The two trees, brother and sister, are quite different; the tamarisk and the palm-tree compete with each other. They argue and quarrel together. The tamarisk says: ‘I am much bigger!’ And the date-palm argues back, saying: ‘I am much better than you! You, O tamarisk, are a use less tree. What good are your branches? There’s no such thing as a tamarisk fruit! Now, my fruits grace the king’s table; the king himself eats them, and people say nice things about me. I make a surplus for the gardener, and he gives it to the queen; she, being a mother, nourishes her child upon the gifts of my strength, and the adults eat them too. My fruits are always in the presence of royalty’.

The tamarisk makes his voice heard; his speech is even more boastful. ‘My body is superior to yours! It’s much more beautiful than anything of yours. You are like a slavegirl who fetches and carries daily needs for her mistress’. He goes on to point out the king’s table, couch, and eating bowl are made from tama risk wood, that the king’s clothes are made using tools of tamarisk wood; likewise the temples of the gods are full of objects made from tamarisk. The date-palm counters by pointing out that her fruits are the central offering in the cult; once they have been taken from the tamarisk dish, the bowl is used to collect up the garbage”

case study: The Hanging Gardens of Babylon by

Nebuchadnezzar IIThere is much controversy around the ownership and location of the hanging gardens of Babylon, some of which claim it to have not been in Babylon whatsoever43. Nevertheless, all accounts describe it as an edifice of substantial size (large enough to be classified as a wonder of the world), adorned with lush sweet-smelling foliage44. Based on the writings of Berossus, the first recorded architectural integration of flora into the edifice (except for agricultural and or namental use) was the hanging gardens of Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar II, and so it seemed like a fitting place to start this study.

Nebuchadnezzar was purported to have reigned during 605-562 BC. Berossus’s writings were the first to attribute the hanging gardens to Nebuchad nezzar45. He purports that the gardens were designed and commissioned to be built for his wife, Amytis 46 . The story as portrayed by Berossus (290 BC) states that the King’s wife had grown depressed by the parched bareness of Babylon, and so had begun to miss the hilly forests of her homeland. This situation creates a perfect allegory of the modern day scenario; where people are equally thrusted into the stark desert of the city, absent the foliage of the natural environmentour evolutionary home47.

Consequent to Amytis’s despair, the king had an ingenious idea to build a replica of her homeland within the walls of Babylon. The Hanging gardens of Babylon was subsequently made of slopes to imitate the Amanus Mountains of north-west Syria and adorned with aromatic trees

The hanging gardens – in all accounts- are connected to a river for irri gation, the structural achievement of the hanging gardens were therefore a feat of engineering for its time, which also attributed the first envisioning of the Archimedean spiral and not the previously thought Archimedes48. This research

43(Dalley 1993)

44(Beaulieu 2006)

45(Dalley 1993)

46(Beaulieu 2006)

47(Beaulieu 2006)

48Dalley, Stephanie, ed. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the flood, Gilgamesh, and others. Oxford University Press, USA, 2000.

has also provided foresight, as to what kind of site to look for when designing my intervention, as irrigation will be an important factor. This case study also illustrates the psychological bond between man and nature. Amytis’s unhappiness mimics what we see today within our own societies; we have people who drive hours just to look at the mountains or forests, or people who spend thousands of dollars on adding greenhouses and greenery to the homes. Consequently, one cannot deny our primordial psychological linkage to the natural world.

nostalGic Man

As the study of ancient civilisations has shown (that of ancient Mes opotamia), from the beginning of civilisation and the first erection of the city walls49, man has recognised the need to create representations of the primordial world he has left behind. The question consequently is, why has man sought to reconstruct the world that he has so brazenly stepped out of? The answer for this goes far beyond that of basic nostalgia. Deeply embedded into our evolution, is the primordial instinct of our ancestors, for example, the slightest glimpse of an object which resembles a snake, triggers an instant fear response50. Likewise, one can deduce that the presence of plants has an equal impact on our psyche, as it once provided healing, refuge and nourishment for our ancestors.

Studies show that children in playgrounds were fonder of engaging in physical activities near trees and shrubs; as such interaction with nature in creased the capacity for imaginative play51. The natural environment, such as parks, can provide an interesting background and objects for children to engage in more immersive play52. Amidst older children, contact with the natural envi ronment has been proven to boost problem solving skills and encourage group decision making53. It has also been shown that human interaction with green spaces can greatly decrease stress levels. High stress levels proliferates the risk of many life-threatening diseases, as well as, one’s perception of his or her physical health54. Over 100 studies have elucidated the fact that stress reduction is a signif icant benefit of spending time in green spaces55

Secondly, in a study of depressed patients, 71 percent of patients real ised a decrease in their depression after going on outdoor walks within a natural

49 Dalley, Stephanie, ed. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the flood, Gilgamesh, and others. Oxford University Press, USA, 2000.

50 (Wolf, Green Cities: Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010, Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

51 Ibid.

52 (Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010, Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010) 53 Ibid.

54 (Wolf, Green Cities: Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

55(Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010, Wolf, Men tal Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

environment; this was contrasted by the 45 percent decrease within the sam ple group who went for walks indoors (artificial environments)56. Urban green spaces encourage exercise and engagement in physical activities which resultantly release endorphins in the brain, which help to combat depression and weight gain57. Moreover, green spaces are normally publicly accessible; hence, they offer a free and affordable means in which to engage in exercise and other outdoor activities58.

According to Wolf, specificity of plants and arrangement, play a crucial role in how one perceives and relates to natural spaces59. Due to the savannah hypothesis purported by Charles Darwin60, it is argued that people prefer open landscapes with scattered flora, much like the landscapes resembling that of the Africa, where most of our ontogenetic evolution occurred. Nevertheless, count er research has also shown that people who spent time in parks with a greater plant species diversity and richness scored higher on various measures of psy chological well-being, than individuals exposed to parks of lower biodiversity61.

56 Ibid.

57 (Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010, Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

58 Ibid.

59 (Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010, Wolf, Green Cities: Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

60 (Shreeve, Sunset on the Savannah 1996) 61(Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

HealinG

The psychological benefits of a human-nature connection are tremen dous; also, those specific psychological benefits also manifest themselves in phys ical ways, such as health. Kaplan states, through a study of six hospitals, the quality of view from patients’ windows were critical factors in the recovery of patients in physical medicine and rehabilitation62. Patients’ views with higher na ture content were purported by Kaplan to have a higher rate of recovery from ailments63.

In a second study of inmates within a prison, inmates who had a view onto the surrounding farmlands sought healthcare less frequently those inmates who had views of other sceneries64. These cases, according to Kaplan, carefully show the importance of an association to nature and its ability to enhance the natural human condition. Evidently, there is a clear and innate demand for the connection with nature as a basic need for humanity.

62 (R. a. Kaplan 1989) 63 (R. a. Kaplan 1989) 64 (R. a. Kaplan 1989)

tHe city

Consequent to our biological ontogenetic development, man remains bounded by genetic memory to be most happy and most efficient within environ ments which even subtly recalls man’s evolutionary home. Nonetheless, millennia of the development of civilisation have drifted man away from their presence among the natural environment into a realm of pure fabrication. Whilst living in a city has its obvious advantages, it also has its disadvantages. Such disadvantages portray themselves in a myriad of psychological, physiological, sociological and environmental ways. These disadvantages affect how and if man may continue to develop as a race. Research in the United States of America shows that in 1900, the average rate of clinical depression was approximately 1 percent; by 2000, that rate had risen to approximately 19 percent; this is a remarkable 2000 percent increase in only 100 years.

In another study, it revealed that depression and other psychological ailments are a side effect of urban life65. The study of 3291 adults in North Cal ifornia showed a higher level of depression within people living in urban areas. Essentially, depression puts the body under significant stress which resultantly raises probability of heart disease, obesity and a weakened immune system66. Also, the lack of healthy human interaction within the city may also lead to the

65 (Barber 2011) 66 (Baber 2011)

feeling of loneliness, which is a key contributor to depression67. The shifting from sustenance farming and caring for livestock has also contritely reduced the opportunities we have to act on our pervasive need of interacting with animals and plants68.

MeMoryThe awareness of the fact that memory is stored within man’s genetic code is a fairly new one. It surmises the theory that memories from ancestors are passed down for generations, which affects personality, mood, as well as pro clivities such as affinities and phobias. Genetic memory is resultantly the reason for humanities inherent compulsion to associate him with natural things. It is assumed that civilisation is approximately 5000-6000 years old69; however, in the chronology of man, and evolution, this is only small instance. Nevertheless, it begs one to ask the question, with enough time, will society be able to rewrite the millennia of memory which our ancestors have passed down?

Currently our society is developing along a line which seeks to distance itself greater and greater from nature. Consequently we see prevalence of tech nological nature in its replacement, some such forms are videos of natural things, natural scented candles among others.

Successively this brings us to the concept of urban memory. Urban memory is the history of amnesia within the people within the built environment, in terms of their response to natural stimuli; it is consequently an evolutionary defence mechanism to secure human survival70. Scientifically, this survival mech anism is called environmental generational amnesia71. This theory expresses the concern that by adapting gradually to the loss of nature within our environment and the inclusion of technological nature, for example, videos and pictures, we will consequently lower the baseline across generations for our kinship with na ture, that is, we will yearn less for the real or natural things72. Kellert and Kahn allegorically explain the concept of environmental generational amnesia as fol lows:

67 (Baber 2011)

68 (Baber 2011) 69 (Maisels 2001) 70 (Crimson 2005)

71 (J. R. Peter H. Kahn 2009 ) 72 (J. R. Peter H. Kahn 2009 )

“Imagine that your favourite food item is the only source of an es sential nutrient and that without it everyone suffers from low-grade asthma and increased stress. Now imagine a generation of people who grew up in a world where this food item does not exist. In such a world, it would seem likely that people would not feel deprived by the absence of this tasty food (it was never in their minds to begin with) and that they would accept low-grade asthma and increased stress as the normal human condition.”73

Accordingly, research has purported that environmental generational amnesia can be insidious, as it decreases ones awareness of the world around him74. In a study of children living in Houston, one of the most air polluted areas in the United States, it revealed that children were well aware of the concept of air pollution, but were completely unaware that their city was indeed polluted, as they had no other point of reference75. Contritely, this is a slippery slope, with each successive generation of degradation; people will continue to take their de graded environmental state as well as their reduced interaction with the natural environment as a normal, leading to a decline in awareness of the environmental problems76.

73 (S. R. Peter H. Kahn 2002) 74 (J. R. Peter H. Kahn 2009 ) 75 (J. R. Peter H. Kahn 2009 ) 76 (J. R. Peter H. Kahn 2009 )

At first glance, one might not realise the direct correlation between fa tigue and the urban environment, but on further inspection, it becomes rather clear. In order to understand the effect of the modern world on fatigue, it is crucial that one first understands the psychology of attention77. For the majority of human existence, information has been comparatively scarce. Nevertheless, this era has brought with it, a slew of information which regretfully leads to in formation overload, and inadvertently; it is attention that is now scarce78.

According to Kaplan (1992), there are two types of attention, involun tary attention and direct attention. Involuntary attention is invoked by something that is genuinley interesting in the environment. Such kinds of attention is simple and effortless; one does not have to exhaust any mental capacity in which to ac complish this level of attention. On the opposite end of the spectrum, is direct attention, which requires effort. Direct attention forces the individual to focus specifically and engage in higher mental processes, for example,problem solving and planning79. Direct attention therefore places the psyche under stress, for ex ample, when you tell a child to pay attention, he begins to focus explicitly on the stimulus. However, the problem with direct attention, is that, one’s ability to do so is limited80

77Kaplan, Stephen. “The restorative environment: Nature and human experience.” In Role of Horticulture in Human Well-being and Social Development: A National Symposium. Timber Press, Arlington, Virginia, pp. 134-142. 1992. 78 Ibid 79 Ibid

80 Kaplan, Stephen. “The restorative environment: Nature and human experience.” In Role of Horticulture in Human Well-being and Social Development: A National Symposium. Timber Press, Arlington, Virginia, pp. 134-142. 1992.

Nature, intriniscally captures our attention, it is filled with interesting stimuli (colors, shadows, smells and tastes)81. Consequently, nature inadvertently captures attention modestly, thus allowing direct-attention a chance to remple mish; resultantly lowering our psychological stressors82. Unlike the natural envi ronment, the city is filled with stimulants which capture the attention directly and dramatically; for example driving in traffic, inherently makes it less restorative and more stressful83. Consequently, it can be deduced that natural stimulants can be a cost effective way to engage one in Attention Restorative Therapy (ART)84. According to ART, engaging in activities or environments with intrinsically in teresting stimuli, such as watching the sunset, gives a cognitive recess and allows direct-attention functions to replenish85.Consequently, the theory asserts that af ter engaging or interacting with the natural environment, one would be able to better perform task that recquire direct attention86

environMental

Hitherto, urban environments despite its intentions to become more hospitable have slowly become climatically harsher87. Cementification and an ex cess of asphalted surfaces has led to a dramatic increase in the microclimate of urban areas; the heat island phenomenon88. Data shows that urban environments are typically 2-5 degrees warmer than surrounding rural areas89. Resultantly, peo ple use more energy for cooling which greater increases the carbon footprint of the city. The increase in temperature also results in an eradication of flora and fauna which can no longer exist under those temperatures.

Due to the higher rates of fuel consumption and industrialisation with in the city, air quality within the urban environment has become increasingly poor; PM10 levels are at an all-time high (PM10 is particle matter below 10 mi crometres)90.As declared by the Europe Commission, PM10 emission causes ap

81 Ibid

82 Berman, Marc G., John Jonides, and Stephen Kaplan. “The cognitive benefits of interacting with na ture.” Psychological science 19, no. 12 (2008): 1207-1212.

83 Berman, Marc G., John Jonides, and Stephen Kaplan. “The cognitive benefits of interacting with na ture.” Psychological science 19, no. 12 (2008): 1207-1212.

84 (Marc G. Berman 2008)

85 (Marc G. Berman 2008)

86 (Marc G. Berman 2008) 87 (Perini 2012) 88 (Perini 2012) 89 (Perini 2012) 90 (Perini 2012)

proximately 350.000 (three hundred and fifty thousand) deaths yearly in Europe alone91. The growing effects of PM10 and smaller particles on the mortality rate and comfort of the city population is consequent to an inadequate amount of vegetation and green spaces92. Apart from the positive effects of vegetation on human wellbeing, it also plays a crucial role in environmental comfort. Plants absorb and reduce the quantity of CO2 and other pollutants in the air93. Perini purports, due to the growing difficulty in finding open spaces within cities, the building themselves can become a place in which plants can be integrated, resul tantly improving the quality of life, while reducing the effects of pollution and environmental damage94

BioPHilia

The human psyche is unequivocally linked to nature. Human beings pos sess an inexplicable proclivity to engage with natural things, and by so doing, it impacts on their health and well-being. This concept is referred to as, Biophil ia95. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, Biophilia is the “idea that humans possess an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life”96. It was coined by German-American psychoanalyst Eric Fromm; it in corporates the Greek word Bio “life” and philia “affinity”. The theory was later developed by Edward Wilson, who purported that that this affinity was subse

91 (Perini 2012) 92 (Perini 2012) 93 (Keenan 2013) 94 (Perini 2012) 95 (Mohawk Group 2016) 96 (Rogers 2016)

quent to the evolutionary and ontogenetic development of the Homo sapiens97.

Fundamentally, Wilson purports, individuals who had more availability to water and the natural resources were favoured for survival; hence their genes were passed on. Evidence for this he claims, can be seen in the ubiquitous fond ness people around different parts of the world feel for the natural environment. The most pervasive evidence for biophilia is Biophobia, which means the fear of nature98. This concept denotes man’s innate ability to react to elements of nature that have been generally a source of danger within the natural environment. Contrarily, this is a reaction to things that were throughout evolution, a threat to human beings, for example, Spiders, poisonous plants and sounds that resemble predators or dangers99.

BioPHilic desiGn

Biophilic design is the intentional endeavour of assimilating the essence of the natural environment into a transmuted architectural model. Studies in the theory Biophilia have created a paradigm shift which seeks to involve the natural elements into the built environment100. All through evolutionary history, human beings have developed their bodies and psyche in response to their evolutionary context(s); not the built environment in which we currently dwell101. Man’s evo lutionary context was influenced heavily by light, sound, odour, wind, weather, water, vegetation, animals, and landscapes. Biophilic design should consequently delineate the physiognomies, the genius loci and the immateriality of the natural environment102. When biophilic design is applied efficaciously, it results in an innumerable amount of benefits such as increased cognition, higher effectivity, better heart rates, lower depression and overall physical fitness103

In a study, it was proven that students who conducted classes in a class room with wooden desks and/or ceilings performed better as there was a de

97 (Mohawk Group 2016) 98 (Rogers 2016) 99 (Rogers 2016) 100 (Mohawk Group 2016) 101 (Mohawk Group 2016) 102 (Mohawk Group 2016) 103 (Mohawk Group 2016)

crease in heart rate, and hostility, higher levels of social interaction and an overall increase in productivity104. Therefore, biophilic design proves itself to be the next step in the evolution of the built environ, and by extension the city.

Biophilic design also has economic advantages, it has been shown to reduce absenteeism in the workplace and improve overall focus and productivity. Biophilia improves overall mood which equates a happier and healthier work force; whom are more willing to engage. Biophilic design also implements ART (Attention restorative Therapy) approaches to help reduce the direct stressors placed on the occupants within the office, for example, the sound of photocopy ing machines, printers and other exasperating stimuli. By improving ones mood in the work environment, resultantly reduces the rates of presenteeism, which is the states of being at work, but not mentally present or simply being ineffec tive105

Biophilic design ultimately enriches the built environment with spiritual ity and life, thus providing an atmosphere where people can connect on transcen dental level106. This imperceptible connection therefore, motivates responsibility and stewardship which will extend itself outside of the building and perhaps trigger a greater holistic appreciation for the natural environment. Biophilic de sign eclectically begins to reconcile man with his lost paradisiacal state.

104 (Mohawk Group 2016) 105 (Mohawk Group 2016) 106 (Mohawk Group 2016)

aPPlicaBility of BioPHilia

Biophilic Interventions can be costly; nevertheless, the long term effects of these interventions can be very fruitful for the success of the organisation. The costly start-up for a biophilic environment will be mitigated by its overall boost in productivity and lower turnover rates107. In an experiment conducted in Sacramento, researchers discovered that by simply orientating workstations toward windows, instead of having them facing away from it, increased overall productivity. Employees were able to make quick glances outside unto nearby tress and parks during work flow. This gave the staff the opportunity to replenish their cognitive processes, consequential to less mental fatigue and greater focus for longer periods of time. This intervention, although costing the company $1000 per person, due to its 6 percent increase in productivity, the company saw a return of $3000 per person108

infrastructure desiGn

Biophilia, as stated previously, is much more than the use of planters and natural looking wallpapers in the building, the greater the level of applica tion of biophilic design, the greater is the restorative reward109. Consequently, to achieve this, one must have specific infrastructural adaptations in order to apply high levels of success within the building. The objective therefore is to incorporate biophilic design holistically into the buildings infrastructural design to increase the nature-human experience110

Flooring is an essential aspect of biophilic design due to its architec tural size. According to an article published by Mohawk Group, an efficacious way of naturalising the floor element is by using dark tones, typically brown and black, as it gives the illusion of soil111. Given its contrast, it can modestly engage occupant’s interest throughout the day. Heraclitean motion is referred to as movement patterns which are associated with a calm and stable mind112. It is

107 (Mohawk Group 2016) 108 (Mohawk Group 2016) 109 (Mohawk Group 2016) 110 (Mohawk Group 2016) 111 (Mohawk Group 2016) 112 (Wolf, Green Cities: Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

an evolutionary consequence of particular weather patterns meaning danger or calm; hence, the movement of soft rhythmic shadows of trees, cumulus clouds, breeze, grass and light, tells our brain that “the weather is good today, relax”. Therefore, it can be of good merit to incorporate such features into the design to promote the feeling of safety and tranquillity, whilst improving productivity and focus within the building or work environment. Heraclitean mimicry can be done by using lighting or spatial design techniques which intrigue the forming of interesting shadows, or subtle rhythmic movement within the façade or edifice113 .

circadian liGHt

A properly lit environment can be Circadian Rhythm, which ultimately leads to an enhanced mood, improved neurological health, and improved alert ness114. Circadian Rhythm is classified as any biological process which happens over the course of 24 hours115. According to Wolf, increasing the use of natural and daylighting and reducing the use of artificial lighting can help streamline this process, resulting in a myriad of health benefits116 .

114 (Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010) 115 (The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica 2017) 116 (Wolf, Mental Health and Function - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health 2010)

The amalgamation of the data so far has led to three key points; the notion of an earthly paradise, environmental nostalgia and spatial exploration due to intricacy. Thus, by using these key points I have attempted to develop a program which rekindles the primordial and ubiquitous relation of man and nature. The goal is to develop an architectural discourse which elucidates the hy bridity with nature and the realm of man, the approach will seek to reconcile the deleterious relationship that man has with the natural environment, whilst inspir ing compatibility and co-dependency. The project should allegorically represent man’s reconciliation with nature.

The Sumerians thought that one was closer to God inside the garden, and that the gods themselves resided in the garden117. As such, it played an im portant role in the psychological archetype of the garden. Hence, this aspect of the program should focus on espousing the genius loci of the natural world. It must represent a state of absolute tranquillity and reverence. It should be ade quately forested. As depicted in most early depictions of the Garden of Eden or the Garden of the Gods, there must be the presence of water.

environMental nostalGia:

The program must explore the wellbeing aspect of nature. It must com bine the primordial intrinsic necessity of nature, with its utilitarian necessity. All spaces should be connected to a greenspace, natural light, natural air and visibility of the sun. Bright daylight can help support circadian rhythm, improve mood, thus improving productivity.

Subsequently, these following points were made in order to appease the essence of our primal instincts:

• Lighting or space design that mimics Heraclitean motion could be incorporated into building design to create calm

• Environments resembling various eco-systems may also be an interesting testing ground for people who may react better to particular vegetation.

• There should be clear visibility of the sun, or sky where possible to help align the body’s natural clock

• Exposure to a biodiverse selection of flora and fauna

sPatial exPloration:

Spatial exploration focuses on spatial intricacy. This must be achieved by the use of architectural and natural elements working synchronously. By doing so, an environment suitable for boosting creativity, work ethic, and productivity whilst encouraging the occupant’s natural curiosity, will be achieved. The spaces should encourage interesting shadows and forms, with layers transparencies and spatial depths.

The office, in the eyes of many has always had a strictly utilitarian pur pose, that is, we go to work, we earn money, and we go home. This example illustrates the typical day for a person of the 21st century. If one were to take a stroll down any metropolitan city, he would see scores of people melancholily making their way to work every morning, and back home every evening. This has become a flavourless cycle within our everyday lives.

Many countries still have exhausting work hours where people are locked up within clustered and sterile offices for hours on end. The United States of America has an average working week of 40 hours, whilst its European com parisons, United Kingdom, Germany and France, favour a 35-hour week shift. This data results show that North Americans spends approximately 25 percent of their 7 day week, within the office whilst its European comparisons spend approximately 20 percent. This data does not take into consideration the time spent in commuting to and from work, which is an added time taken from each individual’s day.

Research shows that we spend accumulatively an approximation of 90 percent of our day within a building118. Most of this time, we come in contact with very little of the natural environment, and we get very little opportunities to sit back, appreciate and explore the world we have around us. Our biophilic pro clivity implores us to interact with the biosphere, and by so doing, my research has persistently elucidated the fact that this will without a doubt, improve our mental and physical health by reducing the toxicity of the urban stimulus.

Consequent to studies, as well as the utilitarian approach people have towards the office, it appears as the most suited place to begin this intervention. The aim is therefore to combine the utility of the office structure with the spir ituality and immateriality of the natural environment. The question now is how one can use these theories to develop an architecture language which will effec tually reconcile man with the biosphere, whilst improving the overall quality of life within the urban environ.

This proposal must utilise the park space of the site efficaciously; so that nothing is taken away from the community. Hence, the building must give back, equivalently what it has taken. It must metamorphose the existing green-park into an architype of a more sophisticated social and aesthetic value. This project takes the physical and virtual connection to the outdoor environment and trans lates it into every publicly usable space and floor within the edifice, resultantly reconciling itself with what it has taken from the public.

The proposals must use biophilic design principles to create a work en vironment that improves the work output of its occupants while reducing the effects of the everyday psychological stressors. There must also be 24/7 perme ability of the public spaces available in the edifice.

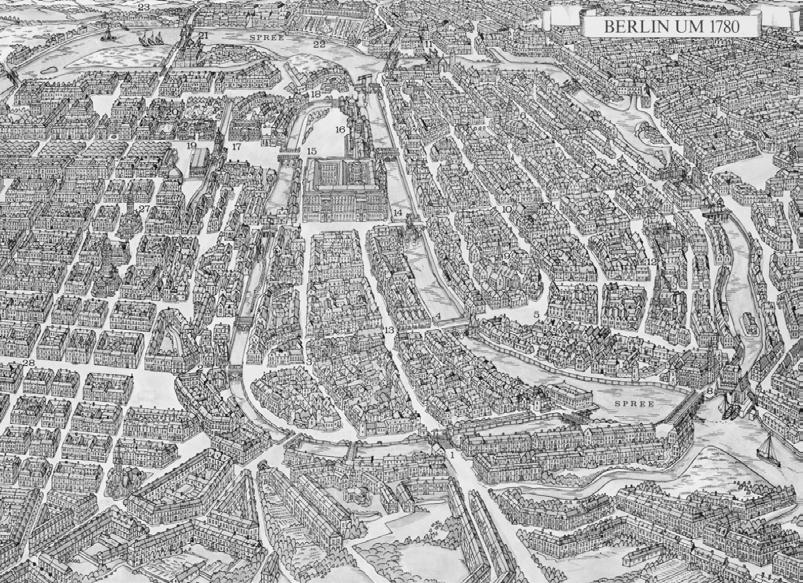

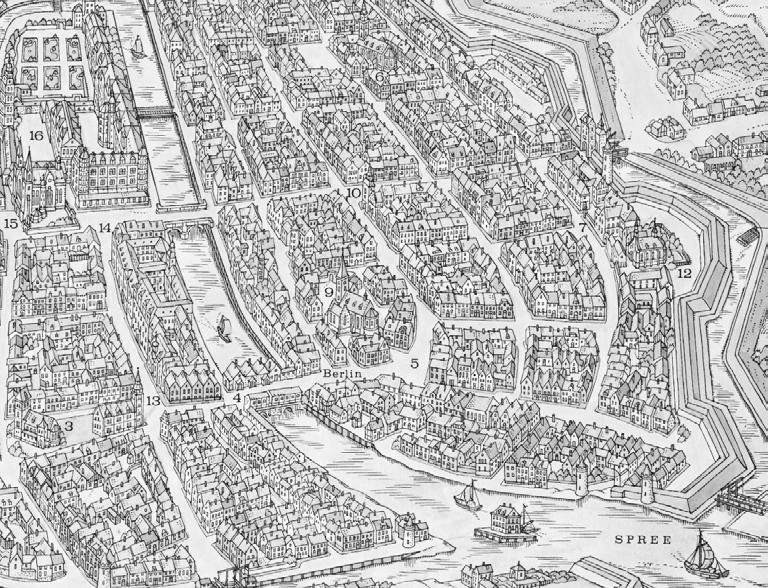

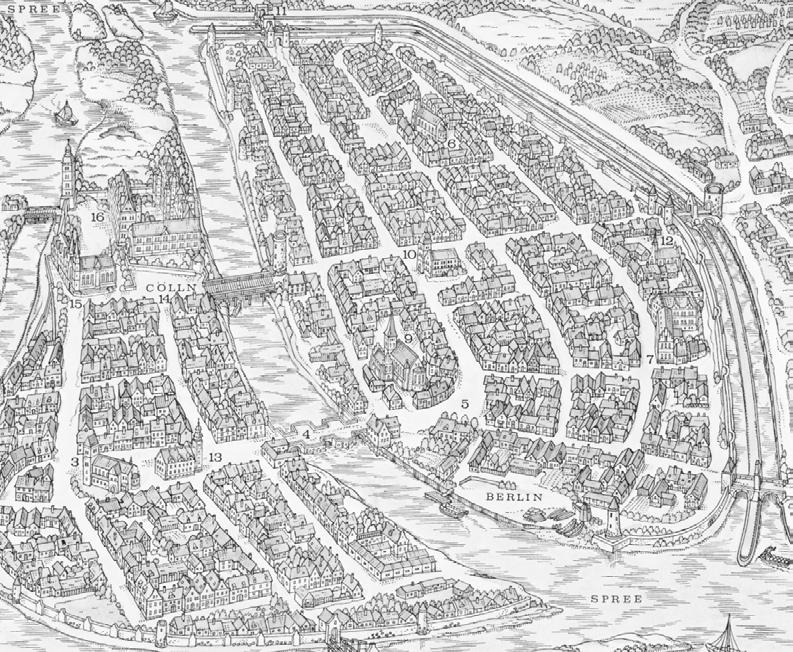

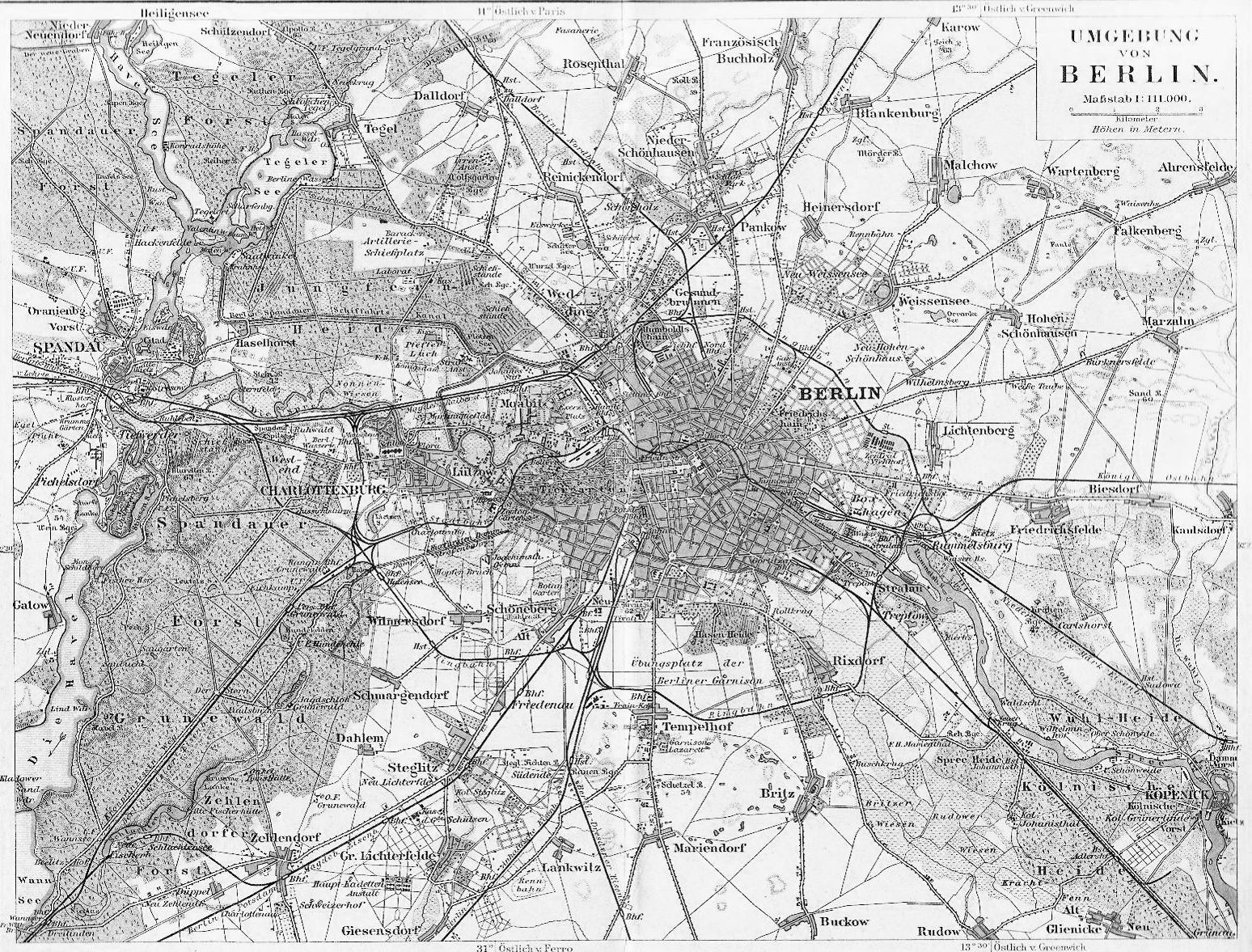

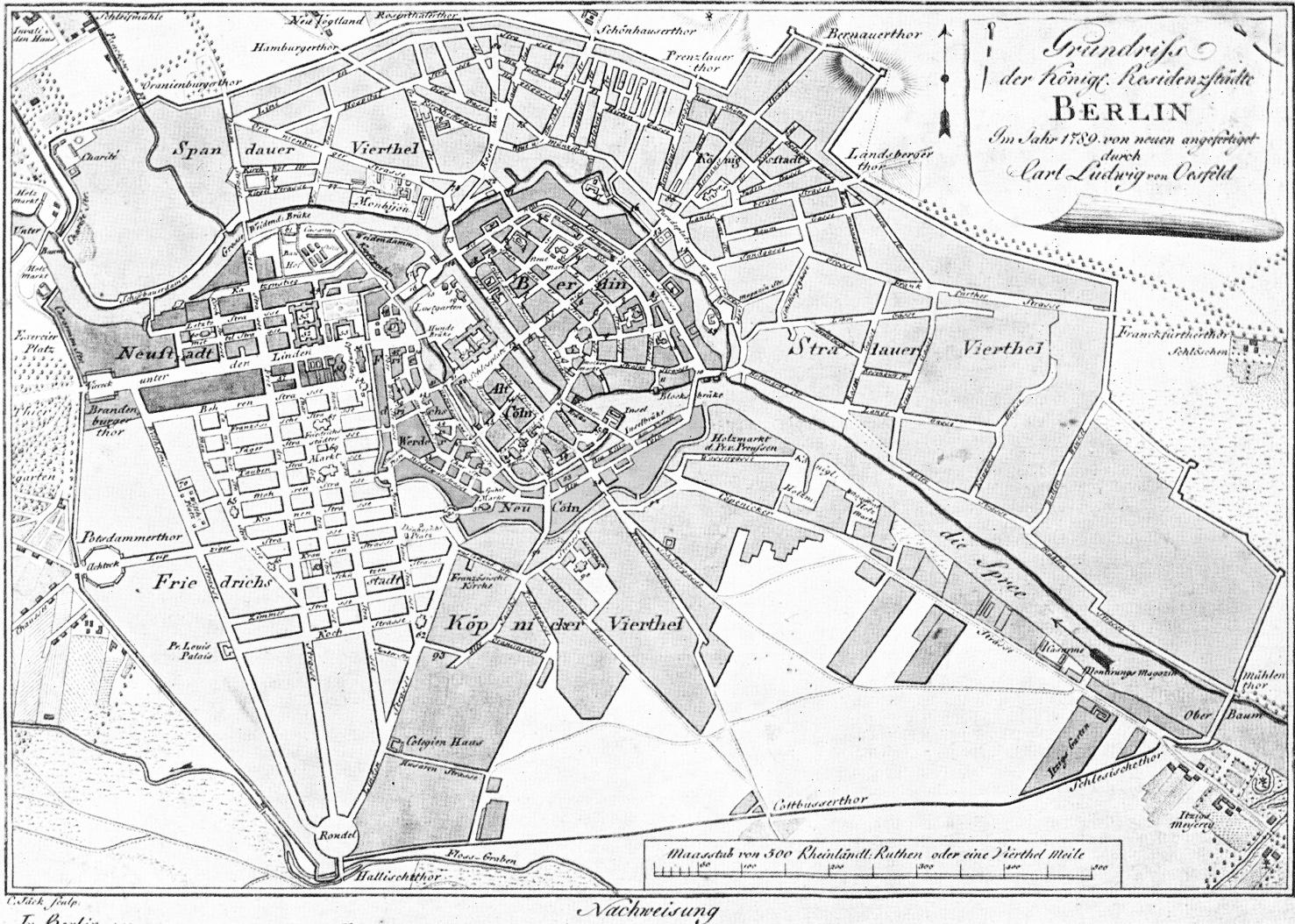

Sectional Elevation looking from Markisches Ufer

Sectional Elevation looking from Markisches Ufer

Sectional Elevation from Spree River

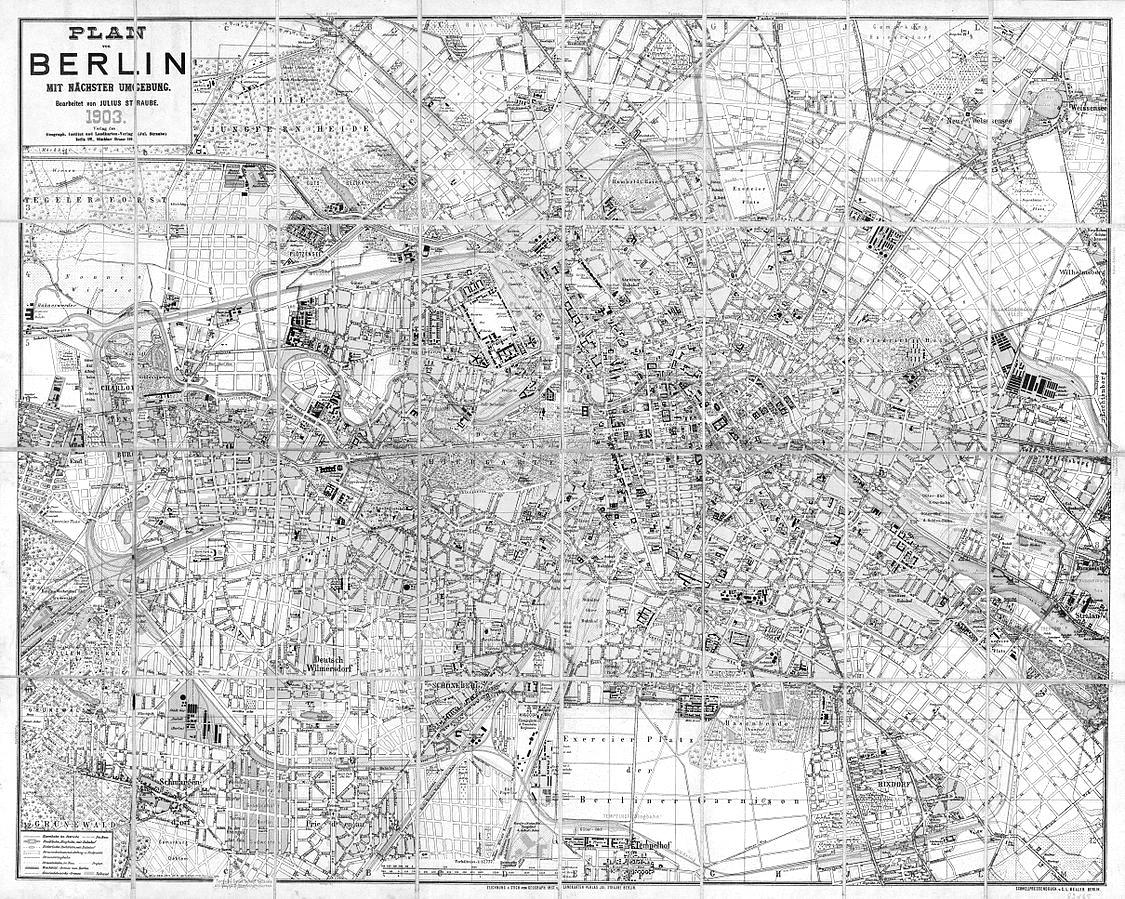

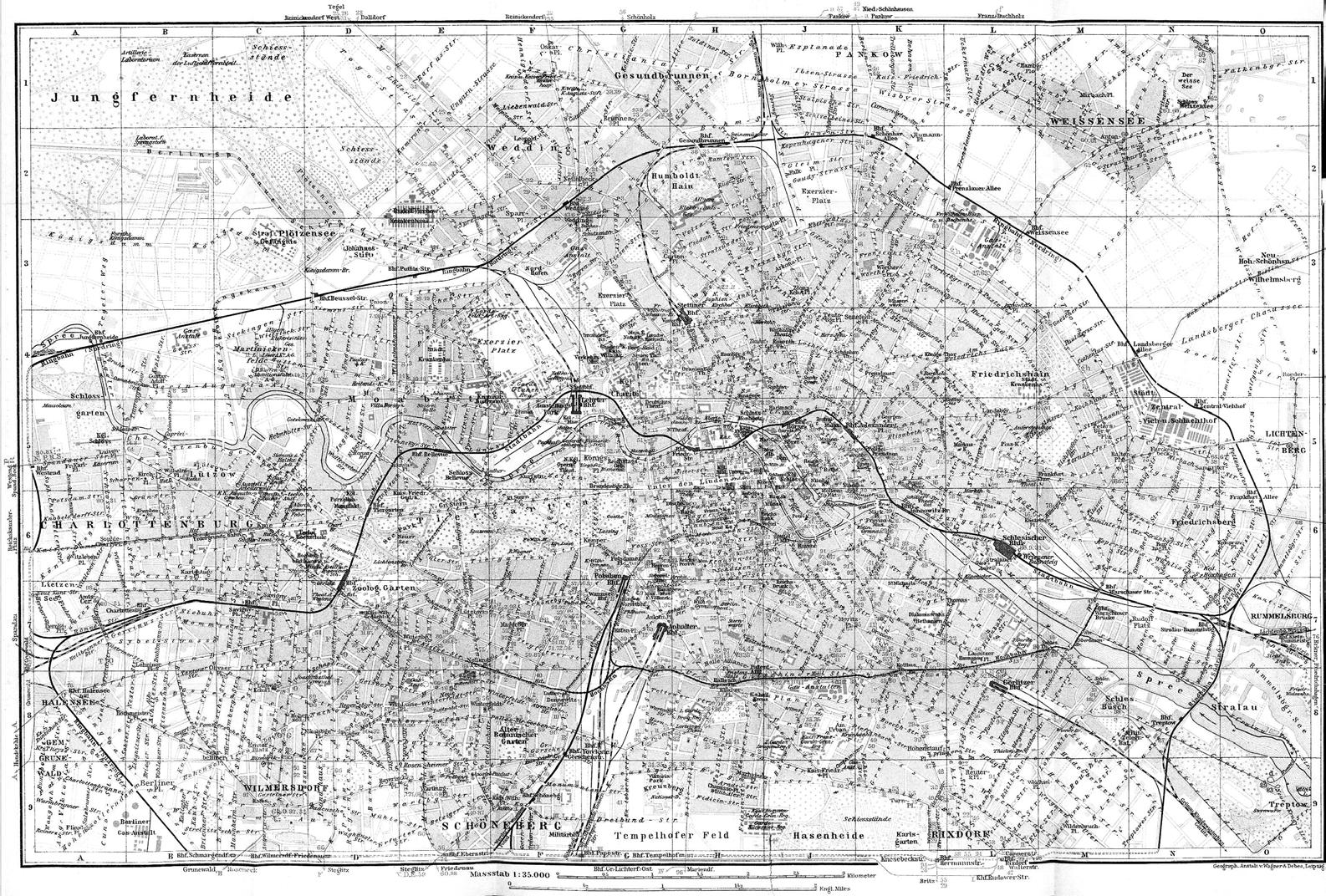

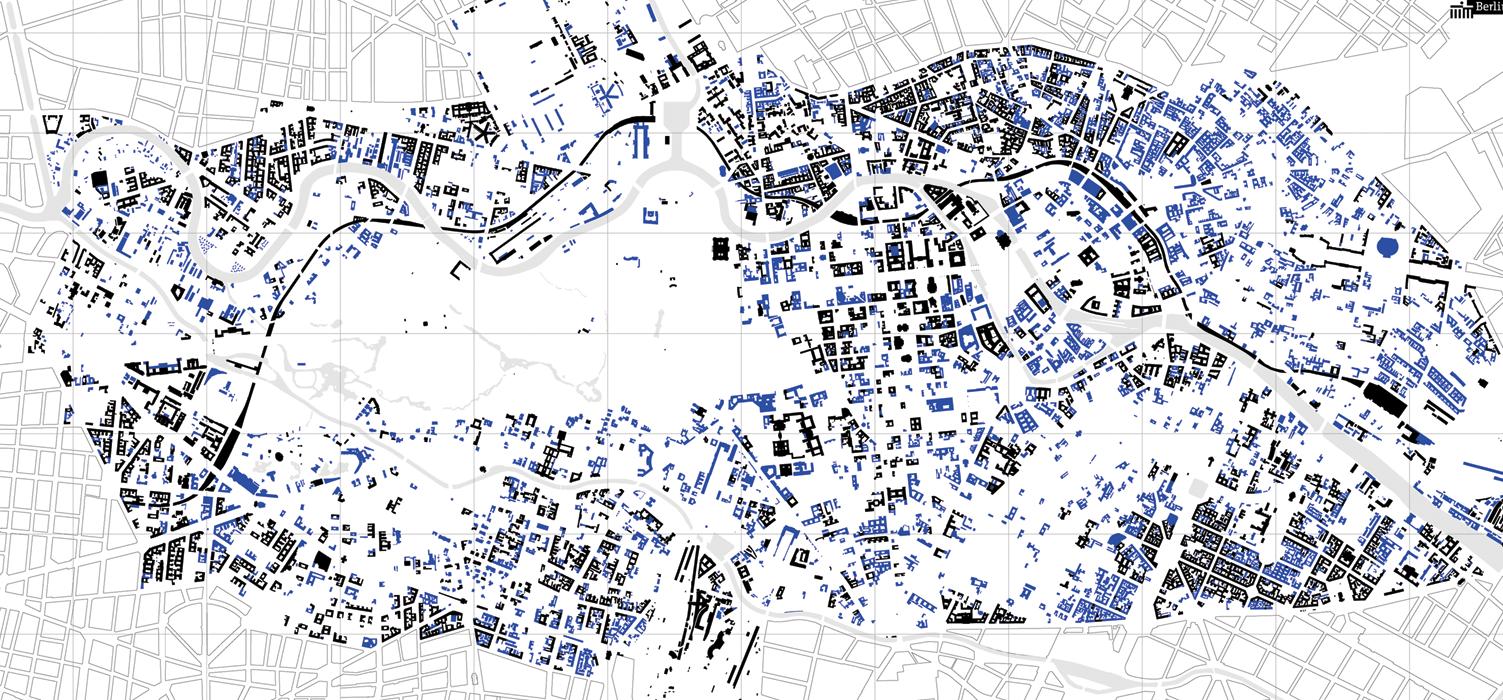

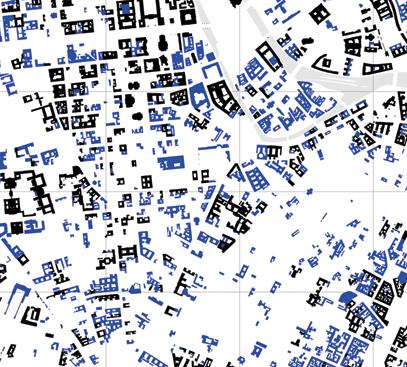

site dRawings

Sectional Elevation from Spree River

site dRawings