9 minute read

ancient MesoPotaMian Gardens

ancient MesoPotaMian Gardens

tHe Gardens of MesoPotaMia

Advertisement

The Mesopotamian civilisation was believed to be a direct follow up of man leaving the Garden of the Gods. Consequent to their nostalgia for their lost paradise, they sought to recreate earthly paradises throughout their entire cities.

Man first settled in civilisations approximately 5000BC. However, even in these early settlements, man still yearned for the green25. Ancient Mesopotamians romanticized the garden, it being the home of their gods. To the people living in these arid regions, the garden was an oasis of flourishing aromatic plants, sweet fruits and vegetables; it offered an area of lull within the otherwise inhospitable environment26. The region had very little rain and lay between the rivers of Tigris and Euphrates, there was very little choice but to use the available rivers to irrigate the lands thus providing the shade and vegetation needed to make the lands liveable and fertile27. As such, one who possessed the skills and knowledge to do so was of high importance, both politically and sexually, as he would represent the fate of their civilisation.

tHe royal Gardens

The Assyrian kings developed the idea of magnificent parks, the concept of their artificial paradises were substantial to their city planning programmes and the tradition was continued by all successive dynasties until the middle ages28 . Despite the extravagance of these gardens, not all gardens were privileged to this meticulous treatment; gardens along rivers and sides of roads were very simplistic.The royal gardens on the other hand boasted extravagance and ostentatiousness; it was comprised of high plant diversity, animals (lions, falcons), and pavilions, well terraced and in many cases artificial lakes29. Although, the main purpose of the royal gardens served for pleasure and relaxation, it also served as an economic means to provide the royal household with food.

25(Dalley 1993) 26(Novak 2002) 27(Novak 2002) 28(Novak 2002) 29(Dalley 1993)

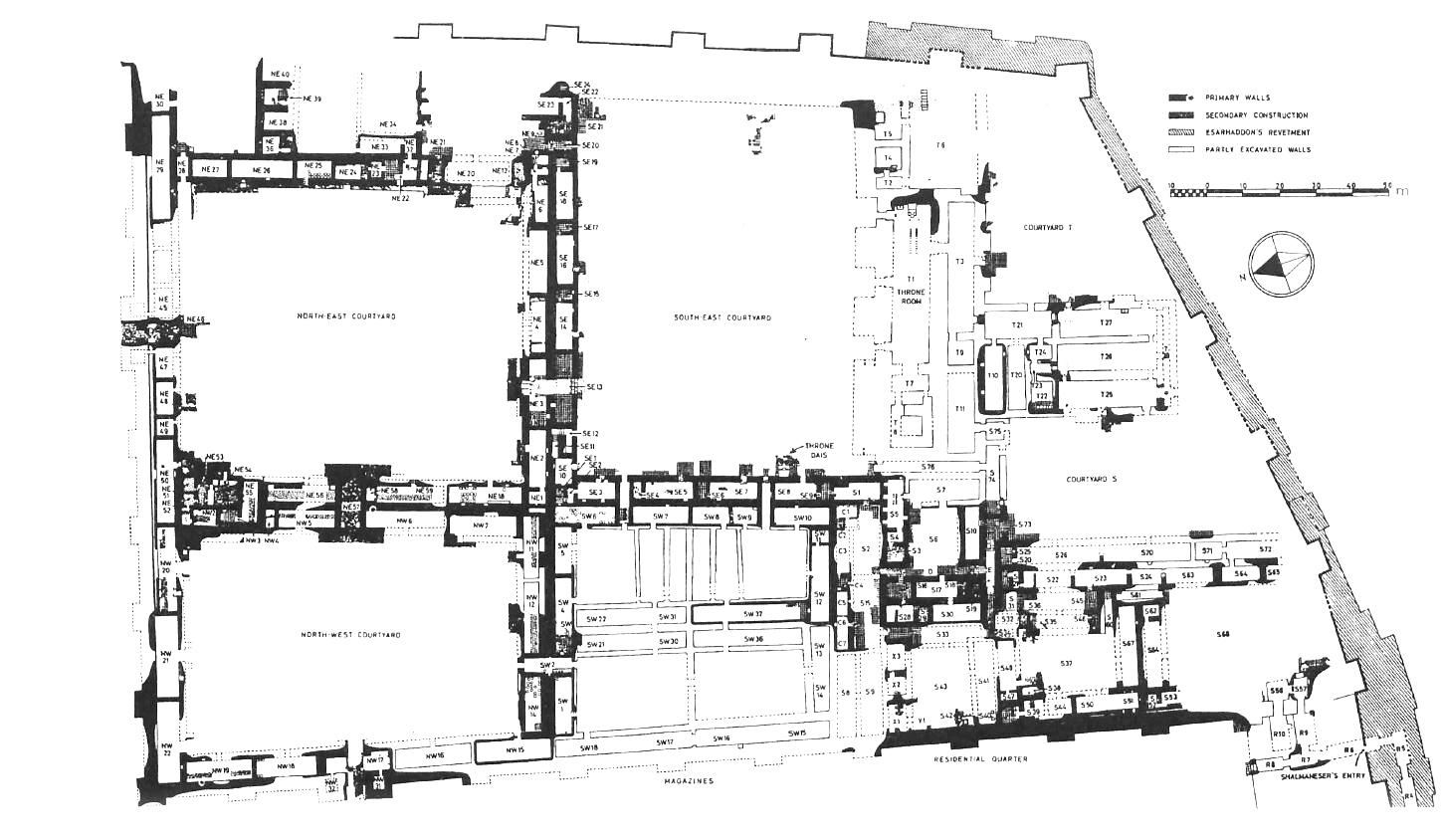

Floorplan of the palace of Shalmanesser III (858-824 BC) in Kalhu. [from Heinrich 1984: 114, Abb. 65]

The royal gardens was a place of absolute splendour and pleasure, however one of the most iconic installations were the Universal Gardens by Tiglath-Pileser (1114-1076BC) 30. According to his inscriptions, he brought plants from all over the world and decided to cultivate them within his specially designed Garden. The result of this was other Kings attempting the same feat, and each time in even greater magnificence, one of which was Assur-Nasir-Apli II (883-859 BC). Assur-Nasir-Apli II’s garden was called Kiri-Risate “The Garden of Pleasure”, it consumed 25 km2, adorned with 41 different breeds of trees and wild animals to amaze the public. Since, his palace was to the west of the citadel, the rooms were allowed to open up to the Tigris and the Garden. As a result, the westernmost rooms were given access to a panorama terrace which later became a substantial aspect of Assyrian architecture31. This feature played an integral role in the future relationship of Mesopotamian architecture, and then successive dynasties and empires that wold try to assimilate a similar aesthetic.

30(Novak 2002) 31(Novak 2002)

tHe Garden of carnality

Within their society, the garden had a strong sexual connotation, that of fertility, and was often a place for romantic affairs to take place because of its cool and relaxing atmosphere32.The temple gardens, hence, because of its beauty and tranquillity, became the place for the marriage ceremonies between the King and the Priestess, and based on the love lyric of Nabu, one can deduce that also love making took place here33 .

The societal impact of the garden also affected the ideology of their monarchy; with one of the characteristics of a good ruler being that of a skilled gardener34. A thriving garden was the result of hard and relentless labour and thus, represented the characteristics of a perfect male specimen and ruler within their society35. The ability to make these arid lands fruitful became a symbol of virility. Thus, the sexual connotation of the garden became a source of much poetry and literature making it susceptible to metaphors involving the male and female reproductive system. The vulva therefore was often described as “well-watered lowland” which should be ploughed (a euphemism for the phallus)36. In a common erotic poem, a woman would sing;

“Do not dig [a canal], let me be your canal,

do not plough [a field], let me be your field.

Farmer, do not search for a wet place, my

precious sweet, let me be your wet place.”37

Consequent to these texts, it was revealed that within the Babylonian and Sumerian society, the male lover was often referred to as a gardener.

32 (Novak 2002) 33(Dalley 1993) 34 (Novak 2002) 35 (Novak 2002) 36 (Novak 2002) 37 (Novak 2002)

H.Waldeck, Hängende Gärten der Semiramis

Nisroch, Assyrian God of fertility and Agriculture

tHe courtyard Garden: utilitarian & intrinsic value

The Mesopotamians were passionate about recreating their version of paradise within their cities 38.The earliest case of the Mesopotamian gardens occurred around the 4000BC39. The gardens were stated to be man’s refuge from the harsh coldness of the city as well as the dangers of the untamed nature40 . As such, the internal courtyard became a safe place away from marauding pigs, thieving ragamuffins and the hot sun41. The Mesopotamians saw the garden as a utility, as well as an entity of its own intrinsic definitive importance. It became a place for brunch, as well as just a place of unparalleled holiness. Poetry was written about their need and love for the green, as both a utilitarian purpose (catering to man’s basic needs of food shelter and clothing) and the immaterial aspects of plants on the society42 .

In a popular Babylonian piece of literature, a tamarisk tree and date palm are personified having a discussion. They resultantly discuss and argue their importance to the garden, their use, and their share beauty, each rebutting by expressing more and more personal grandeur. This piece illustrates the share importance the society placed on flora.

Babylonian stone relief of ruler being tended to by his servants within palace courtyard

38 (Dalley 1993) 39 (Dalley 1993) 40 (Dalley 1993) 41 (Dalley 1993) 42(Dalley 1993)

“The king plants a date-palm in his palace and fills up the space beside her with a tamarisk. Meals are enjoyed in the shade of the tamarisk, skilled men gather in the shade of the date-palm, the drum is beaten, men give praise, and the king rejoices in his palace.

The two trees, brother and sister, are quite different; the tamarisk and the palm-tree compete with each other. They argue and quarrel together. The tamarisk says: ‘I am much bigger!’ And the date-palm argues back, saying: ‘I am much better than you! You, O tamarisk, are a useless tree. What good are your branches? There’s no such thing as a tamarisk fruit! Now, my fruits grace the king’s table; the king himself eats them, and people say nice things about me. I make a surplus for the gardener, and he gives it to the queen; she, being a mother, nourishes her child upon the gifts of my strength, and the adults eat them too. My fruits are always in the presence of royalty’.

The tamarisk makes his voice heard; his speech is even more boastful. ‘My body is superior to yours! It’s much more beautiful than anything of yours. You are like a slavegirl who fetches and carries daily needs for her mistress’. He goes on to point out the king’s table, couch, and eating bowl are made from tamarisk wood, that the king’s clothes are made using tools of tamarisk wood; likewise the temples of the gods are full of objects made from tamarisk. The date-palm counters by pointing out that her fruits are the central offering in the cult; once they have been taken from the tamarisk dish, the bowl is used to collect up the garbage”

Extract from Stephannie Dalley, 2002

Palace Garrden, Terry Ball

case study:

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

by Nebuchadnezzar II

There is much controversy around the ownership and location of the hanging gardens of Babylon, some of which claim it to have not been in Babylon whatsoever43. Nevertheless, all accounts describe it as an edifice of substantial size (large enough to be classified as a wonder of the world), adorned with lush sweet-smelling foliage44. Based on the writings of Berossus, the first recorded architectural integration of flora into the edifice (except for agricultural and ornamental use) was the hanging gardens of Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar II, and so it seemed like a fitting place to start this study.

Nebuchadnezzar was purported to have reigned during 605-562 BC. Berossus’s writings were the first to attribute the hanging gardens to Nebuchadnezzar45. He purports that the gardens were designed and commissioned to be built for his wife, Amytis 46 . The story as portrayed by Berossus (290 BC) states that the King’s wife had grown depressed by the parched bareness of Babylon, and so had begun to miss the hilly forests of her homeland. This situation creates a perfect allegory of the modern day scenario; where people are equally thrusted into the stark desert of the city, absent the foliage of the natural environment- our evolutionary home47 .

Consequent to Amytis’s despair, the king had an ingenious idea to build a replica of her homeland within the walls of Babylon. The Hanging gardens of Babylon was subsequently made of slopes to imitate the Amanus Mountains of north-west Syria and adorned with aromatic trees.

The hanging gardens – in all accounts- are connected to a river for irrigation, the structural achievement of the hanging gardens were therefore a feat of engineering for its time, which also attributed the first envisioning of the Archimedean spiral and not the previously thought Archimedes48. This research

43(Dalley 1993) 44(Beaulieu 2006) 45(Dalley 1993) 46(Beaulieu 2006) 47(Beaulieu 2006) 48Dalley, Stephanie, ed. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the flood, Gilgamesh, and others. Oxford University Press, USA, 2000.

Painting of Hanging Garden Of Babylon, painter uknown

has also provided foresight, as to what kind of site to look for when designing my intervention, as irrigation will be an important factor. This case study also illustrates the psychological bond between man and nature. Amytis’s unhappiness mimics what we see today within our own societies; we have people who drive hours just to look at the mountains or forests, or people who spend thousands of dollars on adding greenhouses and greenery to the homes. Consequently, one cannot deny our primordial psychological linkage to the natural world.

Painting of Hanging Garden Of Babylon, painter uknown