ComparisonofPeraceticAcidandChlorineEffectivenessduring Fresh-CutVegetableProcessingatIndustrialScale

E.PETRI,1 R.VIRTO,1* M.MOTTURA,2 AND J.PARRA2

1R&D&IArea,CentroNacionaldeTecnologíaySeguridadAlimentaria(CNTA),CarreteraNA-134,Km.53,31570Navarra,Spain;and 2Productos CitrosolS.A.,PartidaAlameda,ParcelaC,46721Potries,Valencia,Spain

MS20-448:Received9November2020/Accepted16May2021/PublishedOnline20May2021

ABSTRACT

Thisstudywasconductedtocomparetheefficacyoftwosanitizingagents,chlorineandperaceticacid(PAA),inreducing spoilageandpathogenicmicroorganismsanddisinfectionby-productsinthewashingstageofthreetypesofminimally processedvegetables:iceberglettuce,carrots,andbabyleaves.Thesefresh-cutproductsareconsumeduncooked;thus,proper sanitationisessentialinpreventingfoodborneillnessoutbreaks.Thecomparisonwasdoneatindustrialscalewithequipment alreadyusedinthefresh-cutindustryandwithwashersdesignedandmanufacturedforthispurpose.Resultsshowedthatfor washingwaterhygieneand finalproductmicrobialquality,theuseofPAAorchlorinehadsimilarefficacy.Differentscenarios combiningPAA,chlorine,andwaterweretested,simulatingthecurrentindustrialprocessesforeachofthetestedvegetables. Overall,resultsconfirmedthattheuseofasanitizer,PAAorchlorine,inthewashingwateriseffectiveforthepreventionof cross-contaminationduringthewashingprocessandhenceforproducefoodsafety.For finalproductmicrobiologicalquality andshelflife,theuseofchlorineorPAAshowednosignificantdifferencesinlettuceorbabyleaves.Chlorinateddisinfection by-productsinprocessingwaterwerenotformedinsignificantamountswhenwashingwaterwastreatedwithPAAinall scenariosandforalltestedvegetables,whereaswashingwithchlorine(80mg/L)generatedimportantamountsof trihalomethanes,chlorates,andchlorites.Althoughchloratesandchloriteswerealwaysbelowtherecommendedlevelsorlegal limitsestablishedfordrinkingwater,trihalomethanesexceededthelegallimits.Forperchlorates,valueswerebelowthe quantificationlimitinallscenarios.OurresultsshowthatPAAisareliablealternativetochlorinedisinfectionstrategiesinthe fresh-cutindustry.

HIGHLIGHTS

PAAisanalternativeforreplacingchlorinateddisinfectantsinfresh-cutvegetables. PAAandchlorinehavesimilarantimicrobialeffectinindustrialvegetablewashings. PAAtreatmentgeneratesmuchlessDBPsinwashingwaterthanchlorinetreatment. Incontrasttochlorine,organicloaddoesnotaffectPAAeffectiveness. Atindustrialscale,asecondwashingstepmusthaveaneffectivesanitizerconcentration.

Keywords:Cross-contamination;Disinfectionby-products;Fresh-cutindustry;Microbiology;Peraceticacid;Washwater

Fresh-cutvegetablesaresusceptibletofoodborne pathogensiftheybecomecontaminated (8).Thus,during fresh-cutvegetableprocessing,acriticalareaofconcernis potentialpathogencross-contamination,especiallyduring washoperationswhenwashwaterisreusedandrecirculated inwashingsystemsfedcontinuouslywithfresh-cut vegetables (57).Therefore,additionalmeasurestocontrol thewaterquality,suchasdisinfectingthewashwater,are needed (8).

Chlorine-baseddisinfectantshavebeenwidelyusedin thefresh-cutindustrybecauseoftheirlowcostand sanitationefficacyinfoodprocessing.Oneofthemain concernsofitsuseisthereactivityofchlorinewithorganic

*Authorforcorrespondence.Tel: þ34948670159,Ext8020;Fax: þ34 948696127;E-mail:rvirto@cnta.es.

mattertogeneratedisinfectionby-products(DBPs)with potentialhealthhazards (8,30,37), resultinginadecrease initsefficacyininactivatingmicroorganisms (23,24,39) Insomecountries,includingGermany,Switzerland,The Netherlands,andBelgium,theuseofchlorineinfood processingisbanned (6,44,46);thus,thereisatrendto eliminatechlorinefromthedisinfectionprocess.Inrecent years,thefresh-cutindustryislookingforsustainable alternativestochlorine,suchasperaceticacid(PAA),which hassimilareffectivityandislesscontroversialintermsof itseffectonpublichealth (8)

PAAiscommerciallyavailableasamixturecontaining PAA,hydrogenperoxide(H2O2),andaceticacid.Itis consideredaveryefficientdisinfectantbecauseofitshigh oxidizingpotential (35,42,47,49).Manystudieshave alreadyshowntheefficacyofPAAonthepreventionof

1592

–

1602

https://doi.org/10.4315/JFP-20-448 Copyright ,InternationalAssociationforFoodProtection

cross-contaminationofseveralpathogensinfresh-cut producewashwater (7,8,29,44,52,53);however,most ofthesestudieshavebeenperformedatthelaboratory-scale level.AnotheradvantageofPAAisthatitisnoteasily consumedbyorganicmatterpresentintheprocesswater andwillnotgeneratechlorinatedDBPsorotherharmful DBPs (1,12,13,37) intheprocesswashwater.Becauseof thesefeaturesofmicrobialefficacyanddegradationinto harmlesssubstanceswithnotoxicityrisks,theU.S.Food andDrugAdministrationhasapproveditsuseinwashwater (withoutexceeding80mg/kg)duringtheprocessingof fruitsandvegetables (51).InEurope,PAA-basedformulations,aswellaschlorinateddisinfectants,mustbe consideredasaprocessingaidwhentheyareusedforthe disinfectionoffruitsandvegetables,becausebiocidesare notallowedtobeusedincontactwithfood.Commission Regulation(EC)No1333/2008onfoodadditivesprovides thedefinitionofprocessingaids;however,thereisno harmonizedEuropeanregulationonprocessingaids,and nationallegislationsareenforcedineachstatemember.In thissense,thePAAformulausedinthepresentstudy, CitrocidePLUS(ProductosCITROSOLS.A.,Valencia, Spain),hasobtainedapositivesafetyassessmentfromthe SpanishAgencyforFoodSafetyandNutritionforuseasa processingaidfordisinfectionofwashingwaterinseveral freshfruitsandvegetablesaswellasfresh-cutproduce. Likewise,chlorinateddisinfectantsalsohaveapositive assessmentinSpain.

Numerousstudieshaveassessedthemicrobialefficacy ofsanitizersintheprocessingwateroffresh-cutvegetables atlaboratoryscale,butthereisalackofpublishedstudies onthevalidationoftheirefficacyatindustrialscale(i.e., realscenarios[SCNs]).Inaddtion,mostresearchstudieson theevaluationofsanitizersonmicroorganismreductiondo notconsiderthepresenceoforganicmatterinthewash water (3,10).Infact,chlorinehasahighreactivitytoward organicmatterinthewashwater (55), andithastobedosed continuouslytomaintaintheresidualcomparedwithother sanitizers,suchasPAAthatreactsmoreslowly.

Inaddition,chlorine-baseddisinfectantsproduceseveralDBPsthatarepotentiallyharmfulforhumanhealth. Hypochlorite(HClO)reactswithorganicmatterinwater, formingtrihalomethanes(THMs).Undercertainconditions, THMsundergodisproportionationtoproducechlorideand chlorate,throughamechanismthatcanalsoproduce chloriteasanintermediate.Furthermore,HClOcanreact withthepreformedchloratetogiveperchlorate (17,32,45) On-siteHClOgenerationsystemscanalsoproduce,under typicalelectrolysisconditions,somechloratebydirect oxidationofchlorideorHClO (33).StudieshaveinvestigatedtheformationofDBPsinwashingwateroffresh-cut products (37,41,50,57);howevertherearenotmany studiesthathavebeenperformedunderrealindustrial conditions.

Theaimofthepresentstudywastodetermine,at industrialscale,theantimicrobialefficacyoftwosanitizing agents,chlorineandPAA,forreducingthemicrobialloadin washingwateraswellasintheproductitself.Wealso examinedhowbothsanitizersaffectthegenerationofDBPs aswellastheinfluenceoforganicmatterinthewashing

process.Thedatageneratedareusefulintermsofdecisionmakingprocessestoaidthefresh-cutindustryonchoosing analternativesanitizingagenttochlorine,basednotonlyon laboratoryexperimentsbutalsoontrialsperformedunder realoperationalconditionsatindustrialscale.

MATERIALSANDMETHODS

Plantmaterial. Threetypesoffresh-cutvegetableswere usedinindustrial-scaleexperiments:cuticeberglettuce(Lactuca sativa var.CapitataL.),peeledcarrots(Daucuscarota L.),and babyleaves(babygreenLollo[L.sativa var.Intybacea]andbaby greenBatavia[L.sativa var.Longifolia]).Allvegetablescame fromcommercialfarmsandwereprovidedbyVegaMayorS.L. (Navarra,Spain).Allproductswereharvested,cooleddown duringthe first2hafterharvesting,andstoredat3 6 18Cforat least8hbeforeprocessing.Iceberglettucewashanddecoredon siteandfedintothecuttingmachinetobecutrightbefore washing.Carrotsweresuppliedpeeled,andbabyleafvegetables weresuppliedaswholeindividualleaves.Theselectionofthese vegetablesfortheindustrialexperimentswasmademainlyonthe basisofthedifferencesintheirtissuemorphologyand compositionandtheireconomicrelevancewithinthefresh-cut industry.Thesethreevegetableswereconsideredthemost representativeofthefresh-cutvegetablesmarket.

Toconducttheexperiments,theprocessinglinewasfedfor ca.90minperwashingSCNwiththreedifferentbatches (replicates)fromeachvegetable.IneachSCN,atotalamountof 730kgoficeberglettuce(~243kgperbatch),320kgofcarrots (~106kgperbatch),and600kgofbabyleaves(~200kgper batch)werewashed.

Descriptionofexperimentalsetup. Trialswereperformed atVegaMayorS.L.fresh-cutindustry.Acommercialdouble-wash systemdesignedandmanufacturedbyKronenGmbH(Kehlam Rhein,Germany)andtherestoftheprocessingline(cutting machine,infeedconveyor,vibrationbelt,andcentrifuges)were assembledasshowninFigure1.Thiswashsystemconsistsoftwo separatewashing(W)tanks:W#1,the firstwashermodelGEWA AF(BinFig.1)withacapacityof1,200Lofwashingwater;and W#2,thesecondwashermodelGEWA3800PLUS(CinFig.1), holdingapproximately800Lofwater.Thecompleteprocessing linewasassembledinacoldroom,andalltrialswereperformedat 78Ctoreplicateindustrialconditions.Thefeedingratewas approximately10kg/minforiceberglettuce,3kg/minforcarrots, and6.5kg/minforbabyleaves.Arinsingstepwithchilledpotable water(3 6 18C)wasperformedafterthe finalwashingstep, beforecentrifugation.Finally,theproductswerepackedfollowing VegaMayorS.L.procedures.

Consideringtheabove-mentionedlinedesign,thewashing processforeachproductwasasfollows:

Iceberglettuce:(i)cutting,(ii)feeding,(iii)washingW#1tank, (iv)drainingbelt,(v)washingW#2tank,(vi)rinsing,(vii) vibrationbelt,and(viii)centrifugation

Babyleaves:(i)feeding,(ii)washingW#1tank,(iii)drainingbelt, (iv)washingW#2tank,(v)rinsing,(vi)vibrationbelt,and(vii) centrifugation

Carrots:(i)feeding,(ii)washingW#2tank,(iii)rinsing,(iv) vibrationbelt,and(v)centrifugation

Beforestartingeachtest,bothwashingtankswere filledwith chilledwater(3 6 18C)andasanitizer,thatis,chlorineorPAA. Withachlorine-basedsanitizer,chlorinationwascarriedoutby chlorinegasthatwaspumpedintothechilledwateratadoseof

J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9DISINFECTIONSTRATEGIESINFRESH-CUTINDUSTRY 1593

100ppmoffreechlorine(HClO/ClO;hereafterFC).Next,this chlorinatedwaterwasconductedtoadepositthatfedthewashing tanks(standardroutinechlorinationprocedureanddoseinVega MayorS.L.).Although,accordingtotheliterature,therecommendedminimalresidualconcentrationofFCis15to20ppm (22), atindustrialscale,thecommonpracticeatfresh-cut processingplantsistousehigherchlorineconcentrationsto maintainacertainlevelofFCavailableformicrobialinactivation (23), consideringthattheprogressiveaccumulationoforganic mattermakesitverydifficulttomaintainaproperconcentrationof FCunderindustrialconditions.

TakingintoaccountthatthetypicalpHlevelofuntreated waterinthisareaisaround6.8andthatchlorinegasdoesnot increasethepHofthewater,theconcentrationofactivechlorine (HClO,i.e.,FC)presentatthispHis80ppm.Tomaintainthe chlorinedoseat80ppmofFC,acontinuousrefreshmentwith chlorinatedwaterat80ppmwassetatarateof75%,representing 900L/hinW#1forlettuceandbabyleavesand600L/hinW#2 forcarrots.FCconcentrationwasmeasuredinSCN1before startingtowasheachproducetypeandattheendofeachbatch (ca.every30min),asdescribedunder “Microbialandphysicochemical(COD,THMs,chlorites,andchlorates)analyses.”

ThecommercialformulaCitrocidePLUSwasusedforPAA disinfection.PAAwasaddedautomatically,dosed,andmonitored usingtheproprietarysystemCitrocideFRESH-CUTSystem.This systemallowsacontinuouson-linePAAmeasurementandcontrol tomaintainaconsistentPAAconcentrationatalltimes;thus,in PAASCNs,nowaterrefreshmentwasset.

Consideringthewashingsystemwithtwowatertanks(W#1 andW#2),andthestandardindustrialprocessconditionsatVega MayorS.L.foreachproduct,threedifferentwashingSCNswere testedforIceberglettuceandbabyleavesandtwoSCNsfor carrots(Table1).

Samplecollection. Samplingoperationswererepeatedthree times,onetimeforeachbatch(batch1,batch2,andbatch3)at eachexperimentalSCN.Waterandproductsamplesweretakenat theendofeachbatch(ca.every30min)toassessthemicrobial populationandDBPsformationinwaterandinproduct.

Formicrobialanalyses,watersampleswerecollectedfrom W#1andW#2tanks;forchemicaloxygendemand(COD);andfor DBPsanalyses,watersamplesweretakenfromW#2tank.Allthe collectedwatersampleswerestoredat48Cuntiltheanalysis.

Vegetablesamplesweretakenbeforewashing(aftercutting iniceberglettuce,rawforbabyleaves,andpeeledforcarrots), afterwash1(exceptcarrots),afterwash2,andafterpackaging.

Allthecollectedsampleswerestoredat48Cuntilthe analysis,exceptforsamplestakenafterpackagingthatwerestored firstat48Cfor3daysandthenat88Cforsevenmoredays(shelflifetest:48Cforone-thirdand88Cfortwo-thirdsoftheirshelflife) andanalyzedondays0,3,6,and10.

Microbialandphysicochemical(COD,THMs,chlorites, andchlorates)analyses. Vegetablesamplepreparationconsisted ofplacingasubsampleof25gofproductintoasterileblenderbag (VWR,Spain)andaddingthediluent(0.1% [w/v]buffered peptonewater,Merck,Darmstadt,Germany)ina1:10proportion. Thissolutionwassubjectedtohomogenizationwiththeaidofa stomacher(Smasher,AESLaboratoire,bioMérieux,Inc.,Marcy l’Etoile,France)for60s.

Washwatersamplesweretakendirectly,withoutanyfurther preparation,fromthewashtankandtransferredintosterilebottles containingthespecificneutralizerforeachtreatment:sodium thiosulfateneutralizerforresidualchlorineandamixtureof peptone,meatextract,lecithin,sodiumchloride,andsodium thiosulfatetoneutralizePAA.Allthereagentsusedforthisstudy weresuppliedbyPanreacQuimicaSAU(Barcelona,Spain)and 3MEspaña(Madrid,Spain).Next,samplesweredilutedwhen needed,usingbufferedpeptonewater,asdescribedforvegetable samples.

Aerobicmesophiliccountsand Escherichiacoli determinationwerecalculatedusingavalidatedalternativemethod (automatedmostprobablenumber,TEMPOinstrument,bioMérieux,Inc.).Aerobicmesophilictempocardswereincubated48h at30 6 18C,whereas E.coli tempocardswereincubatedat42 6 18Cforwatersamplesandat37 6 18Cforproductsamplesfor24 hbeforecounting.Microbialcolonieswerecountedandare expressedaslogCFU/gforvegetablesandaslogCFU/100mLfor washingwater.Detectionof Listeriamonocytogenes and Salmonella, in25g,wasdeterminedbyenzyme-linked fluorescentassay

W#1W#2

Iceberglettuce,babyleavesSCN1Chlorine80ppmFC0

SCN2PAA80ppmPAA0

SCN3PAA080ppmPAA

CarrotsSCN1ChlorineNotapplicable80ppmFC

SCN2PAANotapplicable80ppmPAA

FIGURE1. Schematicrepresentationoftheindustrialwashing systematVegaMayorS.L.industry.A,Cuttingmachine;B,W#1 firstwashingtank(GEWAAF);C,W#2secondwashingtank (GEWA3800PLUS);D,rinsing;andE,centrifuges.

ProductSCNreferenceno.Sanitizer Sanitizerconcninwashingwater

TABLE1. Summaryofdifferentwashingscenarios(SCNs)testediniceberglettuce,babyleaves,andcarrotatanindustrialscale

1594 PETRIETAL. J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9

(VIDASimmunoanalyzer,bioMérieux,Inc.)afterincubationat 378Cfor30hand41.58Cfor24h,respectively.

Thechangesinqualityofthewashwaterweredeterminedas follows:CODwasdeterminedbythestandardphotometric methodbyusingaSpectroquantPHARO100photometer (Merck),andresultsareexpressedasmilligramsofO2 perliter. OtherparameterssuchasFC,pH,PAAconcentration,and temperatureweremeasuredinsitutomonitortheircorrectrange duringthedifferentSCNstested.FCwasmeasuredusingthe N,Ndiethyl- p -phenylenediaminecolorimetricmethod(model HI95711,HannaInstruments,Woonsocket,RI)withappropriate testkits,andPAAconcentrationsweremeasuredbyusingPAA teststripsandaphotometerreader(Quantofix,Macherey-Nagel, Düren,Germany);pHandtemperatureweredeterminedwitha multiparameterdevice(SerieHQ,Hach).

TheformationoftotalTHMs,thatis,chloroform,bromoform,bromodichloromethane,anddibromochloromethane,was measured.Thetrihalomethanesbothinwaterandinproducewere analyzedbygaschromatography

massspectrometryasdescribed previously (38).Forprocessingwater,10mLofwatersamples wasusedto fill20-mLglassvials;forvegetablesamples,2gof crushedvegetableswasmixedwith8mLofdistilledwaterin glassvials.Equilibrationwasachievedbyheatingthevialfor15 minat758C.HeadspaceTHMswerecollectedusingaG1888 headspacesampler(Agilent,Barcelona,Spain).Thesyringe assemblyunitwiththetransferlinewasloweredintothevial, suspendedintheheadspaceabovetheliquidlayerofthesamples. After15minofextraction,thetransferlinewasinjectedintothe gaschromatograph.SeparationwascarriedoutonanAgilent 6890Ngaschromatographequippedwitha5975Bmass spectrometricdetector(Agilent).TheTHMswereseparatedona CP-select624capillarycolumn(30mby0.25mm)withheliumas acarriergas.IdentificationofTHMswasbasedontheretention timeofstandardcompounds.EstimationofTHMquantitywas basedontheareasofthepeaksdetectedbymassspectrometry. Resultsareexpressedasmicrogramsperliter(water)or milligramsperkilogram(vegetables).

Chloritesandchlorates,forsamplesofprocesswater,were determinedbyionchromatography,accordingtostandardmethods (27).Resultsareexpressedasmicrogramsperliter.Regarding chloratesandperchlorates,forvegetablesamples,thedeterminationwascarriedoutviahigh-performanceliquidchromatography–tandemmassspectrometryandliquidchromatography–tandem massspectrometry,respectively,involvingsimultaneousextractionwithmethanol(QuickPolarPesticides-Method[QuPPeMethod]),accordingtoEuropeanUnion(EU)ReferenceLaboratoriesforresiduesofpesticides (5).Resultsareexpressedin milligramsperkilogram.TheQuPPe-Methodwasalsousedto measuretheperchloratesinprocesswashwater(resultsexpressed inmicrogramsperliter).

Statisticalanalysis. Ineachexperiment(product),eachbatch wastreatedasareplicateandwasstatisticallyanalyzedusingthe generallinearmodelprocedureofSPSS19(IBM,Madrid,Spain).

SignificantdifferenceswereanalyzedbyTukey’stest.Inallcases, thesignificancelevelwassetat P , 0.05.

RESULTSANDDISCUSSION

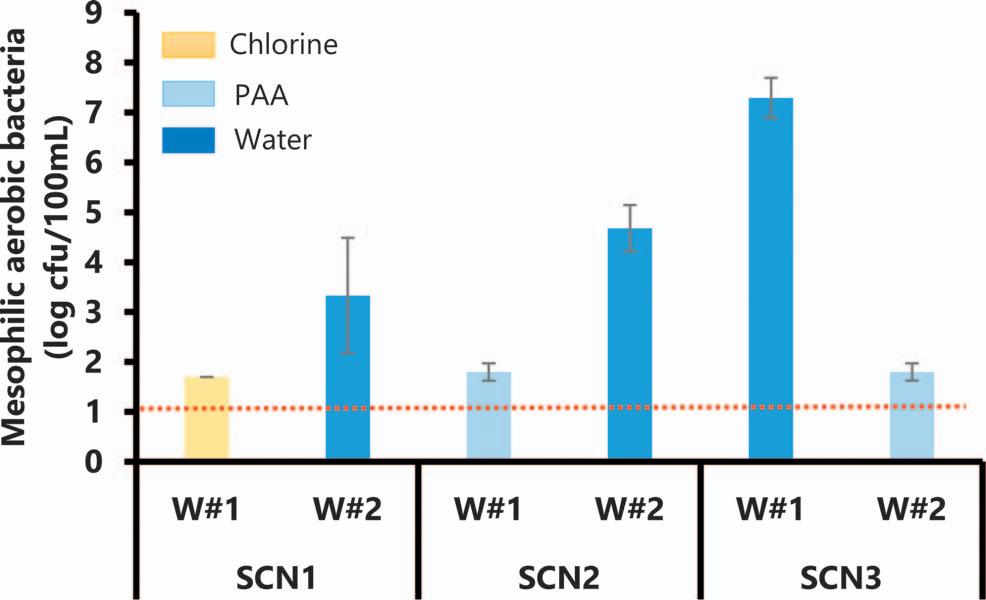

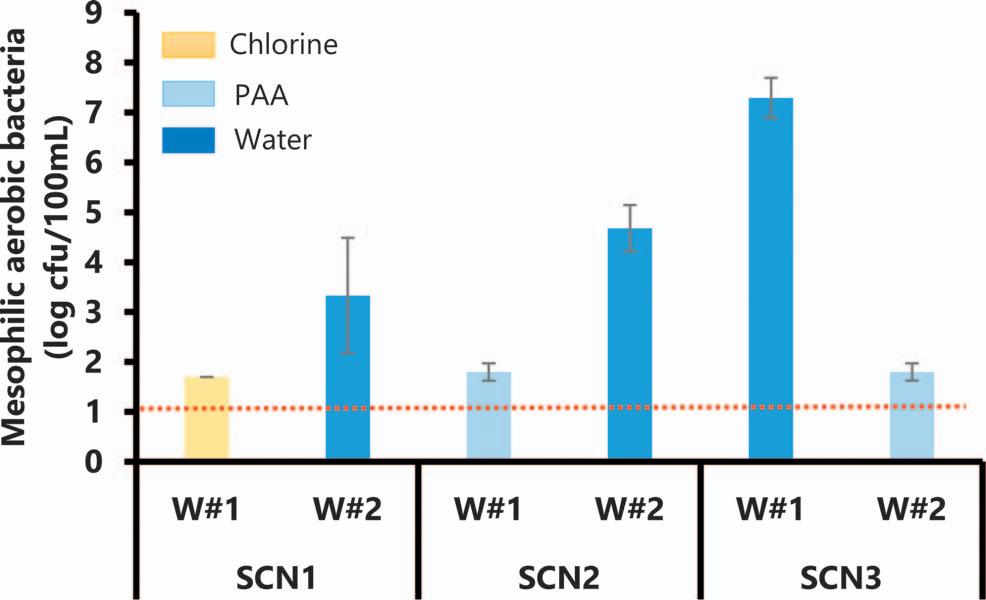

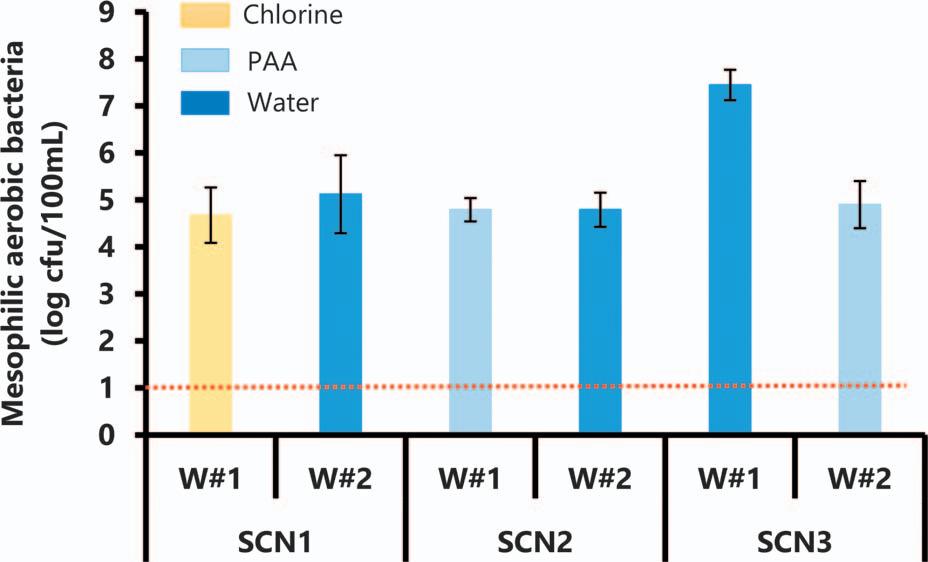

Impactofwashingtreatmentsonmicrobialloadof processwashwateroflettuceintestedSCNs. Theresults ofmicrobiologicalanalysescarriedoutonwashwaterof processedlettuceareshowninFigure2.Whencuticeberg lettucewaswashedinW#1onlywithwater(SCN3),

FIGURE2. Mesophilicaerobicbacteriacounts(logCFU/100 mL)intheprocesswashwateroficeberglettucebyusingchlorine orPAAasdisinfectants(reddashedline,limitofdetection; verticallines,SE).SCN1,W#1(80ppmofFC)plusW#2(water); SCN2,W#1(80ppmofPAA)plusW#2(water);SCN3,W#1 (water)plusW#2(80ppmofPAA).

microbialloadsignificantlyincreasedinthewashingwater. Bycontrast,whenadisinfectantwasaddedintotheW#1 tank(SCN1chlorineorSCN2PAA),themicrobialloadof processingwaterwassignificantlyreducedinthe first washer,asexpected.However,whenPAAwasaddedonly intheW#2tank(SCN3),themicrobialloadinthewashing waterofthesecondwasherwassimilartothatachieved addingthedisinfectantinthe firstwashingstep(SCN1or SCN2).

Notably,amicrobialtransferfromvegetablesto washingwaterwasobservedintheW#2tankofSCN1 andSCN2,whereintherewasabsenceofsanitizersinthe secondwashingstep.Thus,asindicatedbysomestudies (7, 21), thereisanopportunityforfurtherspreadandcrosscontaminationofthemicrobialloadfromwashingwaterto lettucewhennosanitizerisusedinasecondtank. Regardingpathogenicbacteria(E.coli,L.monocytogenes, and Salmonella spp.),inthisinstance,therewasabsenceof thesemicrobes(datanotshown)inallstudiedSCNs.

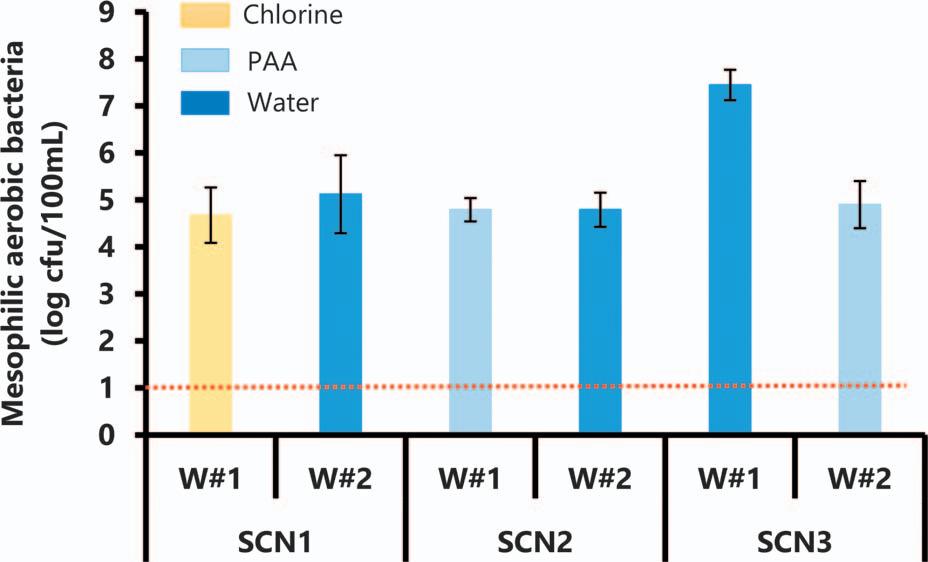

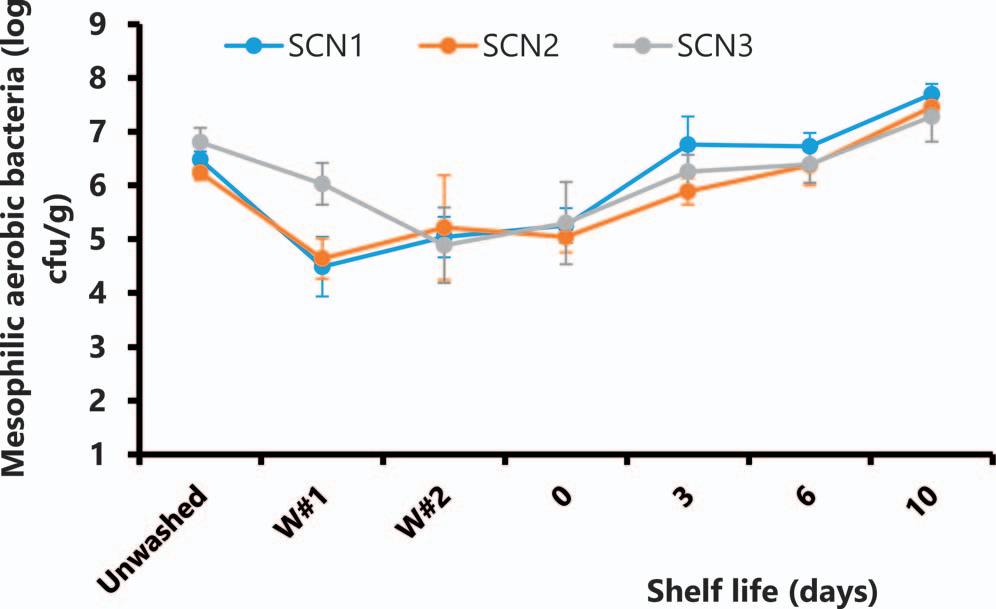

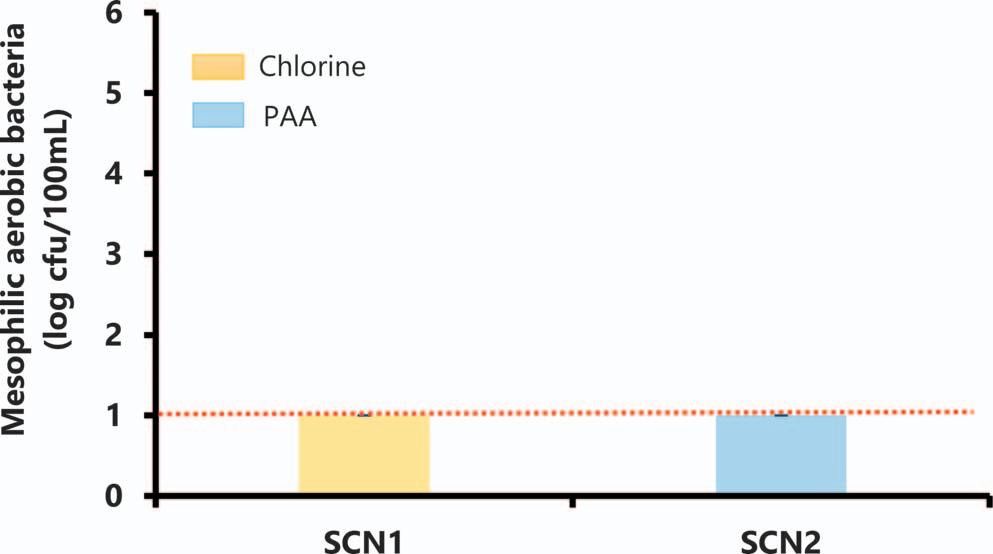

Impactofwashingtreatmentsonmicrobialloadof processwashwaterofbabyleavesintestedSCNs. The aerobicmesophilicloadofthethreetestedSCNsduringthe processingofbabyleavesisshowninFigure3.The maximummicrobialloadreachedwhennodisinfectantwas addedinW#1tankwassimilartothatobtainediniceberg lettuceinthesameconditions(SCN3),thatis,approximately7.5logCFU/100mLofwashingwater.Inaddition, microbialloadreductionwhenaddingthedisinfectantin anywasherwasalsoobservedinbabyleaves,butatalower levelthanobservediniceberglettuce(finalmicrobialload was ~1logcyclehigherthaninlettuce).Whencomparing thedifferentdisinfectantsamongSCNs,nosignificant differenceswereobservedbetweenaddingchlorineorPAA asthesanitizeragent.Asinpreviouscases, E.coli,L. monocytogenes, and Salmonella spp.werenotdetectedin thewashingwaterofthebabyleavesinanyoftheSCNs tested(datanotshown).

–

J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9DISINFECTIONSTRATEGIESINFRESH-CUTINDUSTRY 1595

FIGURE3. Mesophilicaerobicbacteriacounts(logCFU/100 mL)intheprocesswashwaterofbabyleavesbyusingchlorineor PAAasdisinfectants(reddashedline,limitofdetection;vertical lines,SE).SCN1,W#1(80ppmofFC)plusW#2(water);SCN2, W#1(80ppmofPAA)plusW#2(water);SCN3,W#1(water)plus W#2(80ppmofPAA).

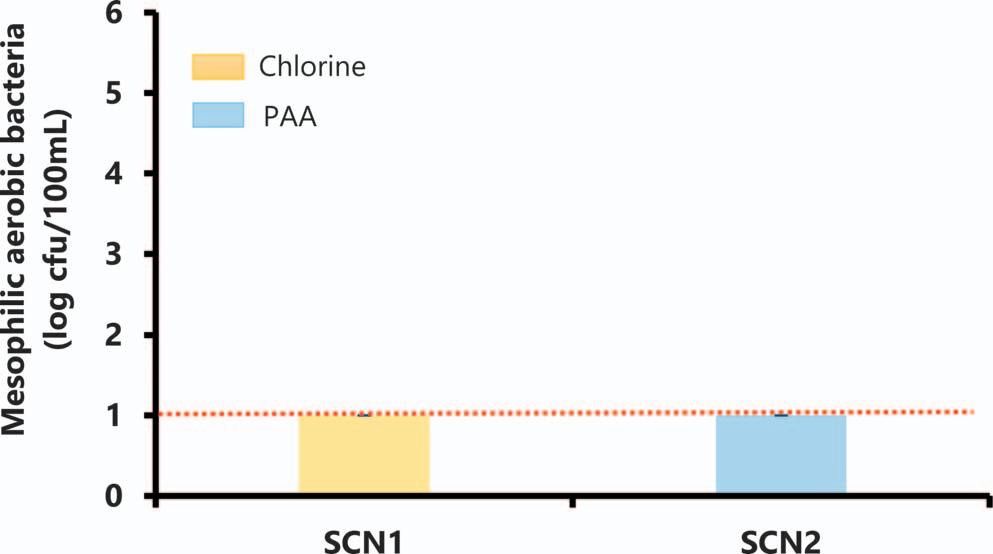

Impactofwashingtreatmentsonmicrobialloadof processwashwaterofcarrotintestedSCNs. Figure4 comparesthemesophilicaerobiccountsfoundinwashing watertreatedwithchlorineorPAAontheprocessingwash waterofcarrots.Mesophilicbacterialloadoftheprocess washingwaterwasexamined,anditwasrevealedthat similarlowcountswerereached(belowthethresholdof detectionof10CFU/mL)overa90-minprocessingperiod inthewashwaterofbothSCNsstudied.Nosignificant differences(P . 0.05)wereobservedinthemesophilic populationremaininginthewashtanksaftertreatmentwith chlorine(SCN1)andPAA(SCN2).

Regardingpathogenicpopulation,analysesindicated absenceof E.coli,L.monocytogenes, and Salmonella spp. inthewashingwaterofprocessedcarrots(datanotshown) byusingchlorineorPAAasthedisinfectant.

Ingeneral,whennosanitizerisappliedtothewash water,itbecomescontaminated,therebyincreasingtherisk ofproducecross-contamination.Therefore,asanitizeragent shouldbeconsideredformaintainingacceptablewater microbialqualityduringthewashingprocess (7,21,22,26, 39,40,54)

.Forallfresh-cutproducewashed(iceberg lettuce,babyleaves,andcarrots),intermsofmicrobial efficacy,bothsanitizeragents(chlorineandPAA)showed similarantimicrobialactivityinthewashingwater, suggestingthatbothareusefulsanitizersforcrosscontaminationprevention.RegardingPAA,theseresults areconsistentwiththoseofmanyotherstudiesthatsupport PAA,aloneorinmixturewithotherdisinfectantsubstances, isareliablealternativetochlorine-basedsanitizerstoavoid cross-contaminationduringwashingprocessesoffresh-cut fruitsandvegetables (4,10,22,29,52–54).Althoughboth sanitizeragentsshowedsimilarantimicrobialefficacy, operationalconditionswhenchlorinewasusedwerevery differentregardingwaterrefreshment.Becausethereisa highchlorinedemandduetothepresenceoforganicloadin thewashwater,acontinuousrefreshmentisneededto maintainFCtargetlevels (22,50).Bycontrast,PAAisnot easilyconsumedbyorganicmatterpresentintheprocess water (1,12,37,43).Thisdifferenceleadstoanimportant

FIGURE4. Mesophilicaerobicbacteriacounts(logCFU/100 mL)intheprocesswashwaterofcarrotbyusingchlorineorPAA asdisinfectants(reddashedline,limitofdetection;verticallines, SE).SCN1,W#2(80ppmofFC);SCN2,W#2(80ppmofPAA).

reductioninwaterconsumptionwhenPAAisused,and henceareductioninenergyconsumption,consideringthat waterusedforwashingfresh-cutproducesiscoldwater, usuallybetween3and68C.

Nevertheless,becausetheuseofPAAasanalternative tochlorinefordisinfectionofwashwaterinfresh-cut producehasbeenintroducedrelativelyrecentlycompared withtheuseofchlorine,morestudiesareneeded.Inthis sense,whencomparingPAAwithchlorine,therearealso someresearcharticlesthatshowcontradictoryresults.A recentexample (28) providesscientificdataaboutthe potentialformationofviable,butnonculturablefoodborne pathogenswhenPAAisusedasawaterdisinfectant.This issuemustbeclarifiedbecauseitmighthavesignificant implicationsfortheapplication.Anotherrecentstudy (40) elucidatesimportantissuesregardingtheproperindustrial applicationofPAA,suchasPAAmonitorization,critical limits,andhygienicconditions,amongothers.Allthis informationmustbeconsideredtoimprovetheindustrial application.

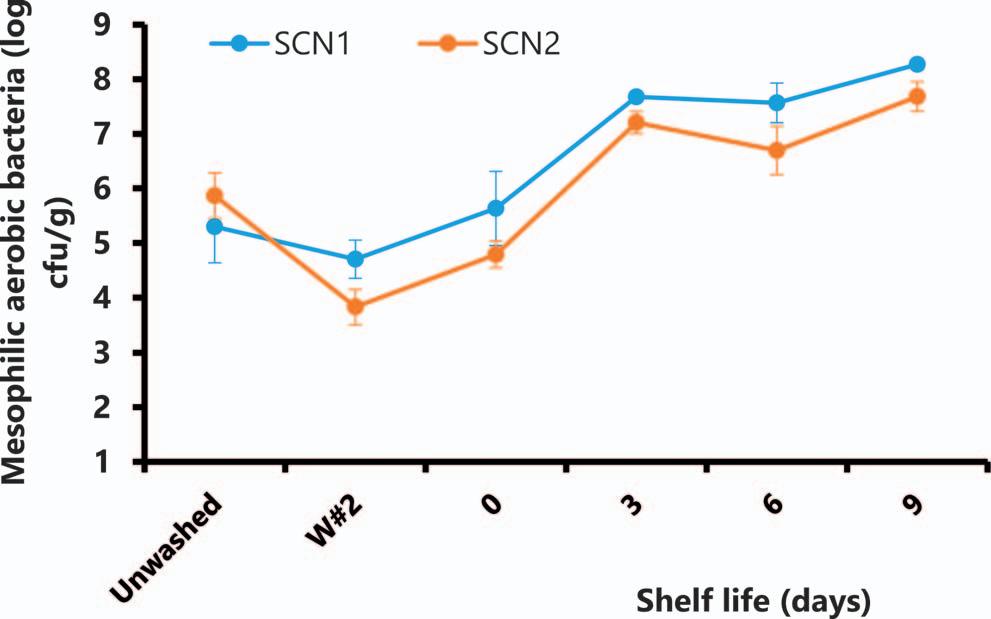

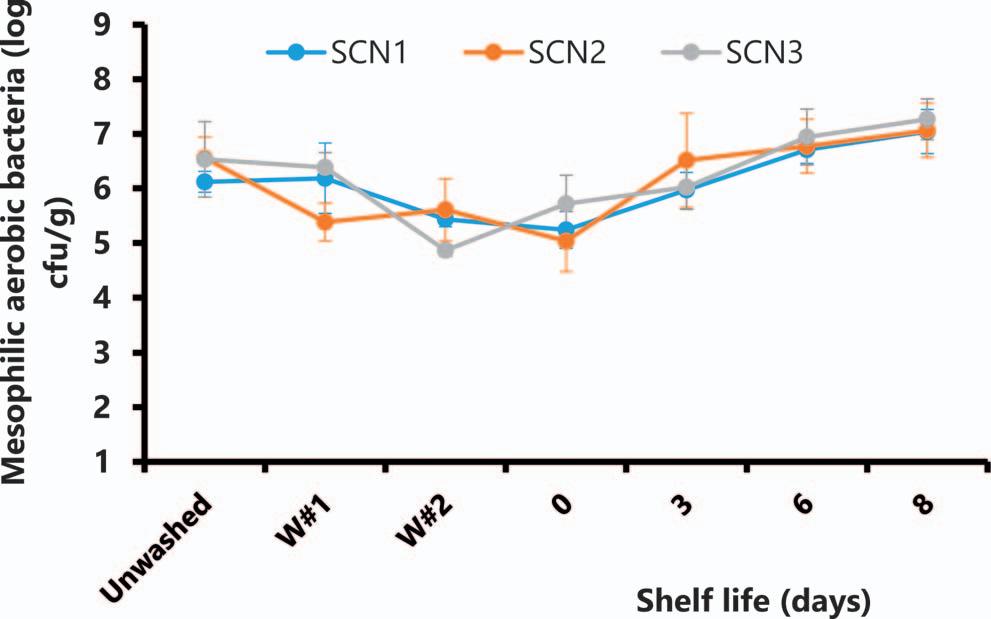

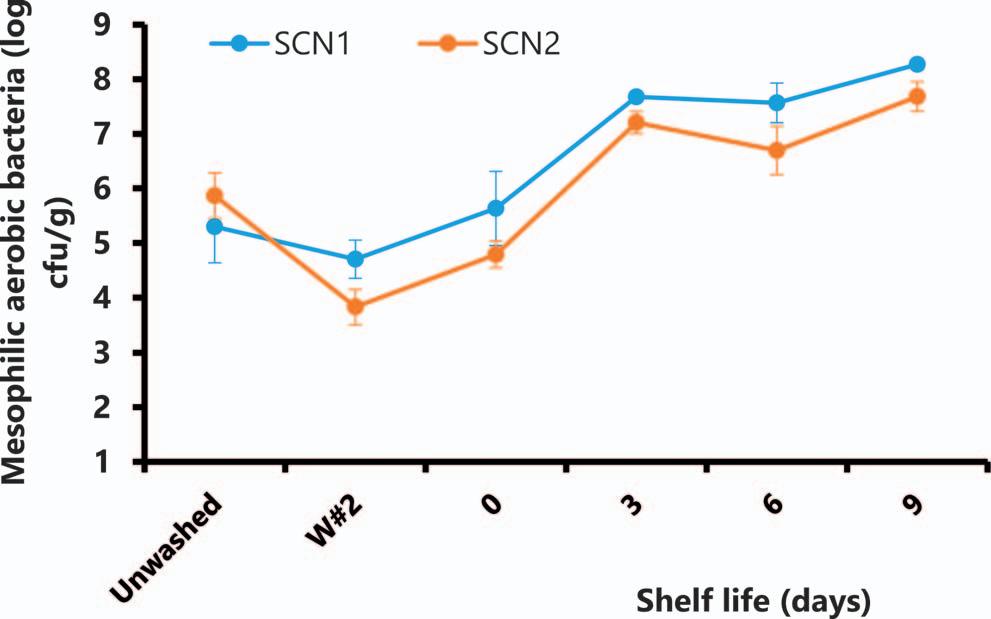

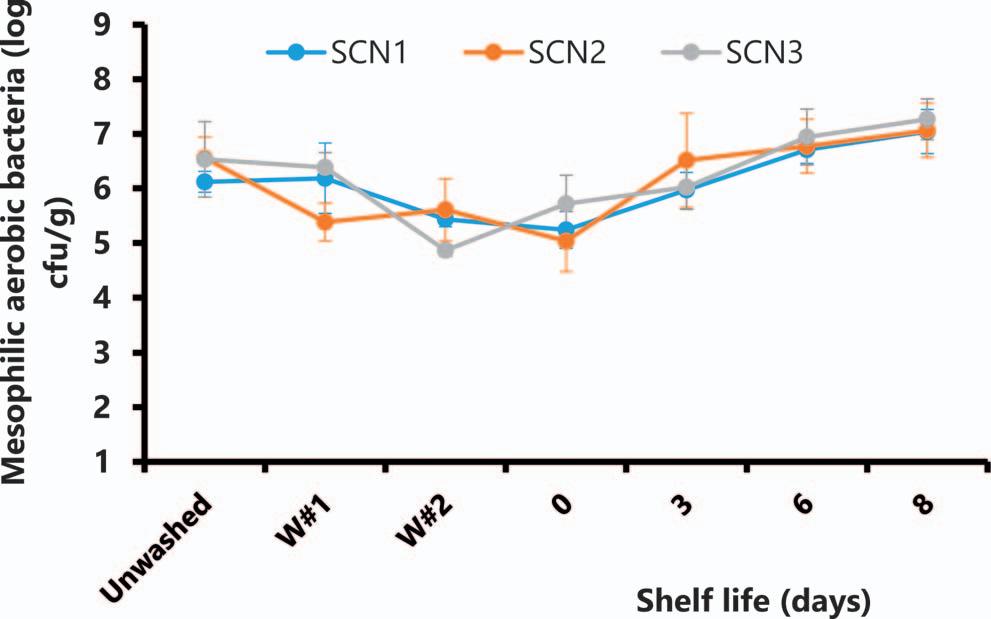

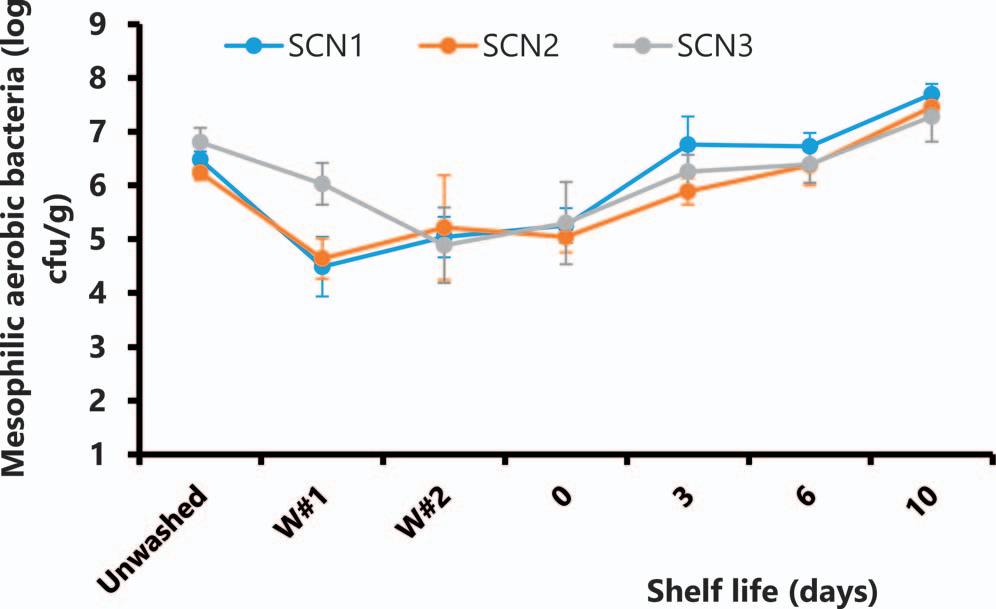

Impactofwashingtreatmentsonmicrobialloadof produceintestedSCNs. Theeffectofthesanitizing treatmentsontheinitialpopulationandsubsequentgrowth ofmicroorganismsoniceberglettuce,babyleaves,and carrotsduringshelflifeareshowninFigures5,6,and7, respectively.Theinitialmicrobialloadoniceberglettuce wasdeterminedimmediatelyaftershreddinginthecutting machinejustbeforewashing.Totalmesophilicloadin unwashedlettucesamplesvariesfrom6.23to6.80logCFU/ g.Atwo-stepwashingprocesswithadisinfectionagent, chlorineorPAA,reducedmesophilicbacterialcountsin lettucesamplesafterwashinginbothwashersatsimilar levels,withreductionsfrom1.45to1.47logCFU/g(Fig.5). Beuchatetal. (10) alsoreportednosignificantdifferences betweenmicrobialpopulationreductionsonlettucewhen treatedwithchlorine(100mg/L)andPAA(80mg/L). Similarinitialmesophilicloadwasdetectedinunwashed babyleaves;inthisproduct,aftertwowashingsteps,the reductionrangedfrom0.69to1.67logCFU/g.Incarrots, mesophilicloadinunwashedproductwas,onaverage,5.58

1596 PETRIETAL. J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9

FIGURE5. Effectofwashtreatmentsonthechangesof mesophilicaerobicpopulation(logCFU/g)infresh-cutlettuce samplesstoredat48Cforone-thirdand88Cfortwo-thirdsoftheir shelf-lifetest(eachsymbolisthemeanofthreereplications; verticallines,SE).SCN1,W#1(80ppmofFC)plusW#2(water); SCN2,W#1(80ppmofPAA)plusW#2(water);SCN3,W#1 (water)plusW#2(80ppmofPAA).

logCFU/g.Inthisproduct,themesophiliccountsincarrot sampleswerereducedby2.0logunitsafterasingle washingstepwithPAA,whereasthereductionofmicrobial loadachievedbyonewashwithchlorinatedwaterwas0.59 logCFU/g.Althoughthereisaninitialreductionof mesophiliccountsafterthewashing(twiceinlettuceand babyleavesandonceincarrots)duringstorage,microorganismsgrewrapidlyonthewashedproduce,reachingvery similarmicrobialloadafter6daysofstorage,regardlessof thetypeofSCNorproducttested.Theseresultswereinline withthosereportedpreviously (9,24)

Mostrecentliteratureregardingtheuseofsanitizers hasconcludedthatwashingwithwaterorwithdisinfectant solutionsreducesthenaturalmicrobialpopulationsonthe surfaceoftheproductbyonly1to2logunits (10,16,25, 26,44).Inourexperimentaltrials,wealsoobserveda vegetablemicrobialreductionof1to2logunits,butdespite

FIGURE7. Effectofwashtreatmentonthechangesofmesophilic aerobicpopulation(logCFU/g)incarrotsamplesstoredat48C forone-thirdand88Cfortwo-thirdsoftheshelf-lifetest(each symbolisthemeanofthreereplications;verticallines,SE).SCN1, W#2(80ppmofFC);SCN2,W#2(80ppmofPAA).

theinitialdifferences,thetotalmesophilicpopulationswere similarattheendoftheirshelflife,independentlyofthe sanitizerused.Therefore,theuseofsanitizingstrategiesis justifiedtomaintainthequalityofthewashingwaterand preventcross-contaminationduringthewashingstagerather thantoobtainamicrobialbenefitontheproduce,giventhe limitedefficacyshownintheseexperimentalresults.

Leafygreens,suchaslettuceorbabyleaves,isoneof thevegetablegroupsmostfrequentlylinkedtobacterial infections (31).However,regardingtheinvestigationof pathogenicmicroorganisms,suchas E.coli,L.monocytogenes, and Salmonella spp.,theywerenotdetectedinanyof theproducesamplesanalyzed(lettuce,babyleaves,carrots) inanyoftheSCNstestedinthisstudy(datanotshown),not evenintheunwashedproduct.

FIGURE6. Effectofwashtreatmentonthechangesofmesophilic aerobicpopulation(logCFU/g)inbabyleafsamplesstoredat48C forone-thirdand88Cfortwo-thirdsoftheirshelf-lifetest(each symbolisthemeanofthreereplications;verticallines,SE).SCN1, W#1(80ppmofFC)plusW#2(water);SCN2,W#1(80ppmof PAA)plusW#2(water);SCN3,W#1(water)plusW#2(80ppmof PAA).

ImpactofwashingtreatmentsonCODlevelof processwashwaterintestedSCNsforiceberglettuce, babyleaves,andcarrots. Figure8showsCODcontentof washwater(collectedfromW#2tank)ofthreeSCNstested inshreddediceberglettuceandinbabyleafvegetablesand ofthetwoSCNstestedinpeeledcarrots.Inlettuceandbaby leaves,whereatwo-washingstepprocesswasperformed, watersamplesforCODanalysisweretakenfromW#2tank becauseitrepresentsthelastwashbeforerinsing;therefore, thiswatermighthaveahigherinfluenceonproduct final quality.Ingeneral,andasexpected,anincreasingtrendof CODlevelswasobserved(Fig.8Athrough8C),as subsequentbatchespassedthroughthewashingtank.This increasecorrespondstotheamountofvegetablematerial washedand,consequently,theamountoftissueexudates releasedintothewater.Figure8Bshowsthatwashwater frombabyleavescontainedalowerconcentrationof organicmatterthaniceberglettuce(Fig.8A)inallSCNs tested.Wholebabyleafvegetableshadlessexudatethan shreddedlettuce,resultinginlowerCODlevelsinwash water.

ThehigherCODlevelsinSCN3(waterplusPAA)in cuticeberglettuceandbabyleavescomparedwithSCN2 (PAApluswater)forthesameproductsarebecausethe

J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9DISINFECTIONSTRATEGIESINFRESH-CUTINDUSTRY 1597

FIGURE8. Chemicaloxygendemand(COD)inprocesswater, measuredinW#2,duringdisinfectionof(A)iceberglettuce,(B) babyleafvegetables,and(C)carrots.Forlettuceandbabyleaves, SCNsareasfollows:SCN1,W#1(80ppmofFC)plusW#2 (water);SCN2,W#1(80ppmofPAA)plusW#2(water);SCN3, W#1(water)plusW#2(80ppmofPAA).Forcarrots,SCNsareas follows:SCN1,W#2(80ppmofFC);SCN2,W#2(80ppmof PAA).B1,batch1;B2,batch2;B3,batch3.CODcontribution duetothePAAdosing,byitself,isrepresentedbythedashedline (seeSupplementalMaterial).

PAA-baseddisinfectantCitrocidePLUSisdosedinthe W#2tankinSCN3,whereasinSCN2itisappliedinW#1 tank.CitrocidePLUSisastablemixtureofPAA–H2O2–aceticacid.ItisknownthatPAAdisinfectionincreasesthe organiccontentinwashingwater,mainlyduetothe presenceofaceticacid,whichisoneofthemain componentsinthecommercialformulationsofPAAas wellasoneofthemaindecompositionproductsofPAA. Aceticacidincreasestheorganiccontentinthewater (35) BecausewatersamplesforCODanalysisweretaken alwaysfromW#2,inSCN3theCODlevelisthesumofthe organicmattercomingfromtheproductwashedplusthe

organicacidscomingfromthedisinfectantappliedinthe samewasher,whereasinSCN2thecontributionoforganic acidsismuchlowerbecausetheyonlycomefromthe residualthatistransferredwiththeproductwashedfrom W#1tankintoW#2tank.Incarrots(Fig.8C),theresultsare similar.TheCODdeterminedinPAA-treatedwater(SCN2) washigherthantheCODlevelofchlorine-treatedwater (SCN1),duetothesumoforganicmattercomingfrom exudatesandfromorganicacidspresentinthecommercial PAAmixture.

ToquantifythecontributiontoCODcomingfromthe doseofthePAA-baseddisinfectantintothesystem,a simulationwasperformedapplyingdifferentdosesof CitrocidePLUSindistilledwaterandthenmeasuringthe CODlevelbyusingastandardphotometricmethod. BecausedifferentPAAformulationsleadtodifferent amountsofaceticacid,theformulaCitrocidePLUSwas usedinthisstudy.Resultsofthissimulationarepresentedin SupplementalFigureS1.Consideringthisstudy,an estimationoftheCODcontributionsduetoPAA-based disinfectionbyitselfarerepresentedasablackdashedline inFigure8.

Inthecomparisonbetweenthetwochemicalagents applied,chlorineandPAA,chlorinereactsrapidlywith organicmatter,decreasingitsdisinfectionefficacy.Consequently,acontinuousrefreshmentofthewashingtankswith freshchlorinatedwaterisneededtomaintainthetarget dose.Hence,thelowerlevelofCODinSCN1(Fig.8Band 8C)isduetoadilutioneffectproducedbythiscontinuous refreshmentwithchlorinatedwaterneededtoavoidthe rapiddepletionofFCconcentrationasvegetablesare dischargedintothewashtank.Bycontrast,PAAdisinfectionefficacyandPAAdemandarelessaffectedbythe presenceoforganicmatter,becauseacontinuouswater refreshmentisnotnecessary.

ToevaluatetheeffectivenessofchlorineandPAA treatmentsinthepresenceoforganicmatter,some laboratory-scaleexperimentsalsowereperformed,adding differentlevelsoforganicmattercomingfromshredded iceberglettuceinthewashingwater.Intheseexperiments, thechemicalswereappliedataconcentrationof50mg/L, andwemeasuredtheinactivationeffectafter1minof contactfor E.coli O157:H7and L.monocytogenes (Fig. S2).Inaddition,withthesameobjective,FCandPAA concentrationsweremonitoredduringthetrials,atlaboratoryscale,inwatersamplessupplementedwithorganic material(vegetablepuree)toreachCODlevelsthatcould representrealindustrialconditions(600mgO2/L).Results showedthatFCconcentrationwasdrasticallyreduced duringthe firstcontactseconds(from80ppmto ,5ppmin ,5min).Bycontrast,inthepresenceofthesameorganic mattercontent,PAAconcentration(also80ppm)wasstable (withouthardlyanymodifications)formorethan3days. TheresultsoftheseexperimentscanbeseeninFigureS3.

Althoughchlorineiscommonlyappliedasadisinfectantinprocessingwashwatertopreventcross-contamination (8), theseresultssupportthatincreasinglevelsof organicmaterialinthewashingwaterdecreasethe disinfectionefficacyofchlorine,whereasPAAdisinfection

1598 PETRIETAL. J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9

efficacyremainsconstantindependentlyoftheorganic materialexistinginthewashwater.Organicsolublesreact rapidlywithchlorineanddecreasetheFCconcentration and,consequently,itsdisinfectioneffectiveness (18)

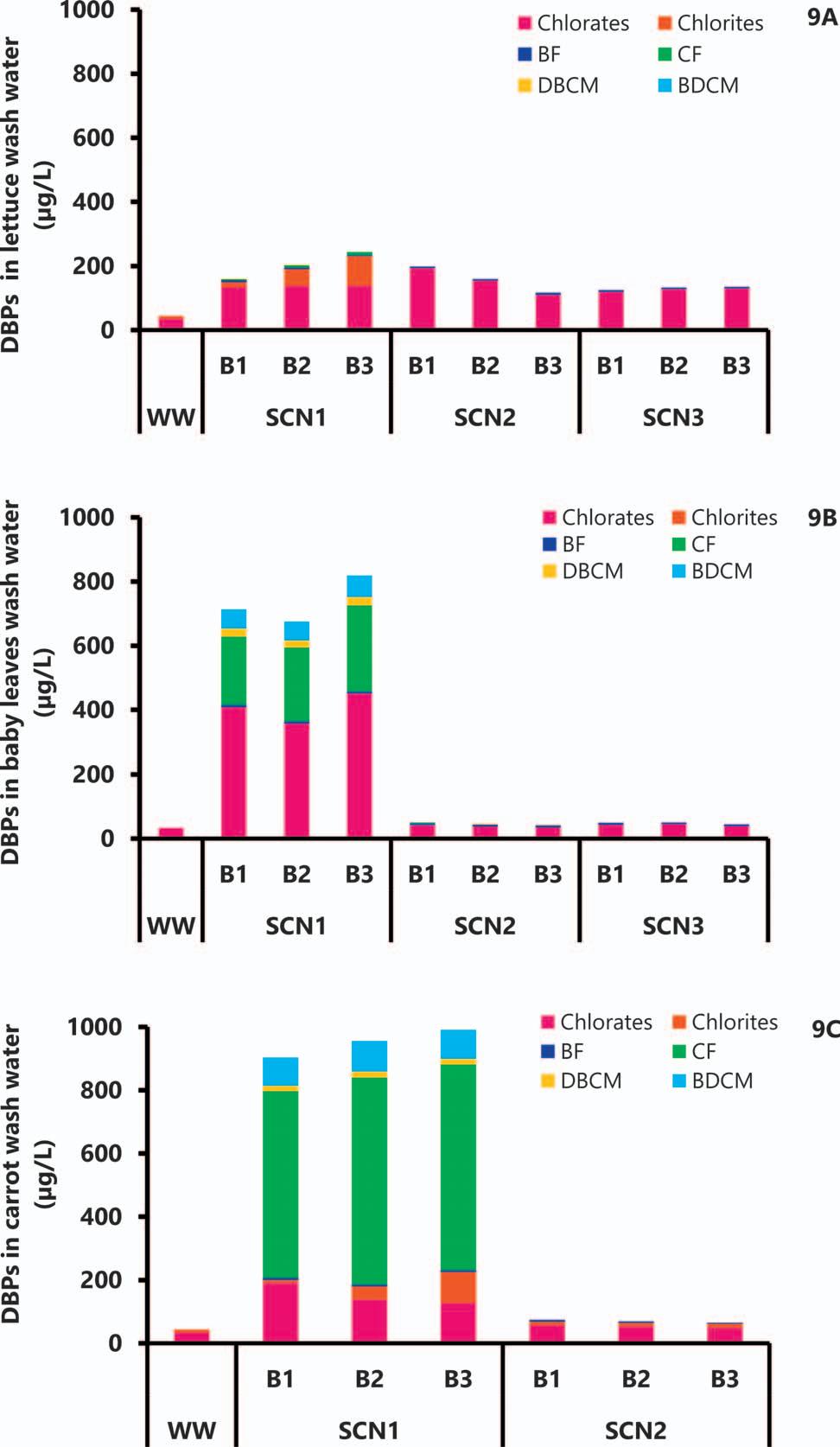

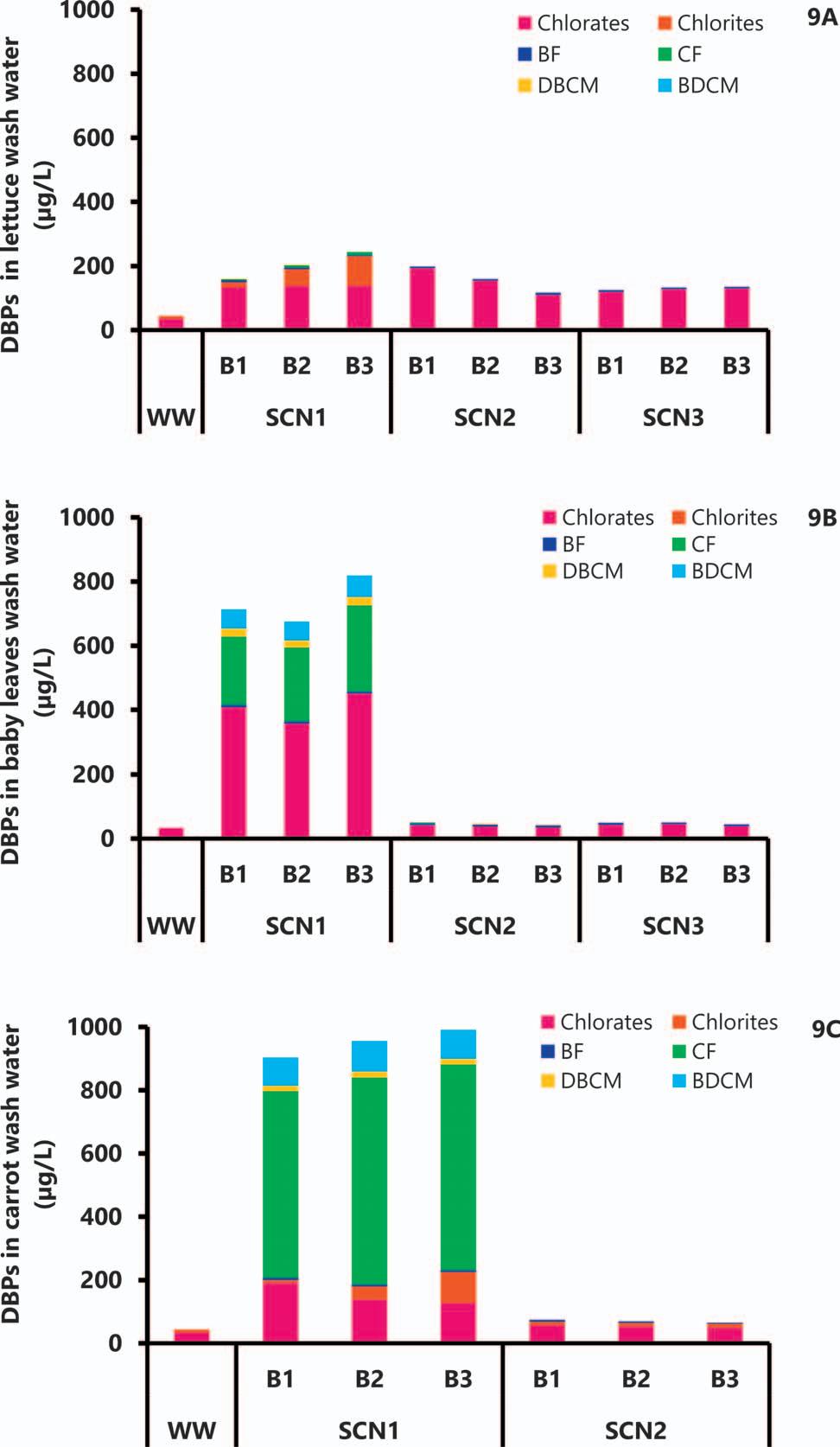

ImpactofwashingtreatmentsonDBPsgeneration inprocesswashwaterandinproduceatdifferenttested SCNsforiceberglettuce,babyleaves,andcarrots. The generationofDBPsinwashingwaterandpresenceinthe finalproductwerealsoevaluated.Thewaterusedinthe washersingeneralinthefresh-cutindustry,andspecifically inVegaMayorS.L.plant,ispotabletapwater(WW). BecauseWWisusuallychlorinated,itwasimportantto determinethebackgroundlevelsofDBPsinthiswater.The resultsofDBPsanalysisinWWareshownintheleft-most columnofeachproductinFigure9Athrough9C.

FortheanalysisofDBPsinwashwater,watersamples inallSCNswerealwaystakenfromW#2tankattheendof thewashingprocess.Figure9Athrough9Cshowsthe resultsoftheDBPsfoundinwashwateroflettuce,baby leaves,andcarrots,respectively,inthedifferentSCNs tested.Washingwith80mg/Lchlorine(SCN1)generated importantconcentrationsofchlorinatedDBPsinthe washingwaterinallproductsstudied.Bycontrast,andas expected,SCN2andSCN3whereinPAAwasusedas disinfectantdidnotshowsignificantamountsofchlorinated DBPs,exceptforabackgroundlevelofchloratecoming fromWW.Inaddition,iniceberglettuce,thisbackground levelwassignificantlyhigherthanthelevelinWW.This higherlevelmustnecessarilycomefromtheproduce, becausePAAisnotasourceofchlorine.Accordingto Kaufmann-Horlacheretal. (34), leafyandfruitingvegetablesareparticularlynoteworthyforbeingeasilycontaminatedwithchlorateresiduesinthe field,forexample,dueto irrigationwithchlorinatedwaterorunauthorizedapplicationofherbicides,andthismayresultinapotentialtransfer towashingwater.Thissituationalsocouldexplainthe presenceofchloratesinPAA-treatedwatersamples.

RegardingtheconcentrationofDBPsinwater (50), the onlyguidelinethatcanbeusedasareferencevalueisthat fordrinkingwater.Consideringthis,anddespitethechlorite andchloratevaluesmeasuredinallproducts,allwater samplescomingfromdifferentSCNscompliedwiththe levelrecommendedforchlorites(800to1,000 μg/L)and withthechlorateguidelinelevel(700 μg/L)fordrinking waterquality (58) .Bycontrast,forTHMstheEU establishesthemaximumlevelinhumandrinkingwater as100 μg/L (14,58), andthislimitisonly80 μg/Linthe UnitedStates (14).Accordingtotheselevels,allwater samplescomingfromSCN1inbabyleavesandcarrots exceededtheTHMsconcentration,evenafterwashingonly onebatchofproduce.Bycontrast,whenthesetwoproducts werewashedwithPAAasdisinfectant,theTHMsformation was,asexpected,negligibleandalwaysfarbelowthe above-mentionedlimits.Inlettuce,THMsformationwas verylowinallthreeSCNs.Forperchlorates,allSCNs’ valueswerebelowthelimitofquantification.

WhenchlorinewasusedassanitizernotonlytheDBPs amountsbutalsotheirprofilesweredifferentforeach

FIGURE9. Concentrationsofdisinfectionby-products(DBPs)in theW#2washingwaterattheendofeachofthethreebatches washed(B1,B2,andB3)of(A)iceberglettuceprocessing,(B) babyleafvegetables,and(C)carrotsandintapwater.WW,basic levelsintapwater;SCN1,disinfectionwithchlorineinW#1and waterinW#2inicebergandbabyleavesandchlorineinW#2for carrots;SCN2,disinfectionwithPAAinW#1andwaterinW#2for icebergandbabyleavesandPAAinW#2forcarrots;SCN3, disinfectionwithwaterinW#1andPAAinW#2.BF,bromoform; CF,chloroform;DBCM,dibromochloromethane;BDCM,bromodichloromethane.

productwashed,andagrowingtrendinDBPsmeasuredin waterwasobservedovertime.ThisincreaseinDBPswas observeddespitethecontinuousrefreshmentperformedin SCN1.

GenerationofDBPsinthewashwaterdependsmainly onthedisinfectionagentandotherfactorssuchasthe applicationconditionsorthereactivityoftheorganicmatter comingfromthewashingproduce (41).RegardingTHMs, resultsobtainedwithchlorineSCNsarereasonablebecause dilutedHClOiswellknowntobeveryreactivewithorganic matterreleasedfromtissueexudates,whichaccelerates chlorinedepletion (48) andhencetheformationofTHMs. Bycontrast,chlorates,perchlorates,andchloritesare

J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9DISINFECTIONSTRATEGIESINFRESH-CUTINDUSTRY 1599

directlyrelatedwiththeself-degradationofHClOunder certainconditions,asdescribedintheintroduction.Itisalso wellknown(2,27,32)thatformationofchloratesby disproportionationofHClO(FC)isstronglyfavoredathigh concentrationofHClO(aswellaslong-timestorage,close toneutralpH,andhightemperature);forthisreason,in practice,chloratesareabundantwhenstockconcentrated sodiumhypochloriteisusedasthesourceofHClOandhas beenpreviouslystoredunderinadequateconditionsorfor longperiods.Consideringthis,thesignificantamountsof chloritesfoundintheSCN1oflettuceandcarrotsandthe importantincreaseinchloratesinSCN1ofbabyleavesand carrotsseemunexpected,asweusedinsituchlorination withchlorinegas.However,aslongasHClOispresentin thesolution,disproportionationisfeasibletoagreateror lesserextentdependingontheconditions,sowedonot find itunusualtoobservemicrogramperliterconcentrationsof chloratesandchloritesinourexperiments,because chlorinationwithchlorinegasinstantlyproducesHClOin water (32).Itisimportanttoremarkthatwhenchlorination isperformedbyusingaconcentratedHClOsolution,the mostfavoredconditions,chlorateconcentrationsinthe milligramperliterlevelareusuallyobserved (50), whereas inourlessfavoredconditions,dilutedHClO,weonly observedmicrogramperliterlevels.Nevertheless,we considertheseresultsrelevantbecausetheypointoutthat evenunderlessfavoredconditions,chlorates(andchlorites) canstillbeproducedinconcentrationsclosetothelegal limitswhenusinginsitu–generateddilutedHClO(from chlorinegas)andnotonlywhenusingstockconcentrated storedsolutions.

Whenthe finalproductwasanalyzedforthedifferent DBPs,nomeasurableamountsofchlorates,perchlorates, andTHMswerefoundwithanySCNforanyofthestudied products.AlthoughsignificantamountsofchlorinatedDBPs werefoundinwatersamplesofchlorinetreatments,after thecompletewashingprocessthelevelsofDBPsonall productswerebelowthelimitofquantification,indicating thattherewasnotransferofDBPsfromwashwaterto final productafterwashing,rinsing,andcentrifugating.The absenceofDBPsonfresh-cutproductalsowasobservedin otherstudies (11,36,38).However,thetransferratiosof DBPsfromwashwatertoproducearenotwellcharacterized (50), andtheyarelikelytobeaffectedbydifferent factorslinkedtoproduceitselfaswellastheprocess (19).

Someauthors (24) observedatransferfromchlorinated washwatertobabyspinachof4%,andothers (38) reported 15% transferofTHMsinfresh-cutlettucewashedwith chlorinatedwater.Inrelationtochlorateresidueson produce (20), transfercanbeapproximately10% from washingwatertofresh-cutlettuce.Consideringthese transferratescitedinliteratureandaccordingtothe obtainedlevelsofchloratesinourstudy,evenintheworst situationinSCN1,chloratelevelinallproducestudied wouldbebelowthelimitapplicableincarrot(0.15mg/kg) andinleafvegetables,includinglettuceandsalads(0.70 mg/kg)definedbythenewEUregulationonmaximum residuelevelsforchlorateinoronfoodproducts (15).For THMs,consideringtheworstSCN,thatwouldbe15%

transferfromwatertoproduce,andSCN1incarrotswhere thesumofTHMsinwaterwasapproximately0.750mg/L, thetheoreticalamountofTHMsremainingincarrotswould beapproximately0.1mg/kg.However,produceanalyses showedinallcasesthatTHMsconcentrationsinproduce, lettuce,babyleaves,andcarrotswerebelowthelimitof detection(8 μg/kg).Theseresultsledtotheconclusionthat, intermsofoccurrenceofDBPs,theuseofchlorine-based sanitizersmightnothaveimpactinthe finalproductwhen thedescribedindustrialwashingprocessisfollowed. However,theformationandaccumulationoftheseDBPs inthewashingwaterhavebeenlinkedtoanincrease chemicalriskinready-to-eatvegetables (17,37,41,50), andanydisruptionormalfunctioninthewashingprocess, thatis,waterrefreshmentalteration,incorrectrinsing,or centrifugating,mightleadtoproducecontaminationwith DBPs.Furthermore,evenwhenthefoodsafetyrisk regardingDBPscouldbehypotheticallycontrolled,the generationofTHMs,chlorates,andchloritesinvolvesan importantenvironmentalproblemwhenchlorinatedwash waterhastobepoured (37,56)

Insummary,theresultsofthisstudyshowthattheuse ofPAAat80ppminthewashingwateroffresh-cuticeberg lettuce,babyleaves,andprocessedcarrotsrepresentsa reliablealternativeforthefresh-cutindustrytoreplacethe useofchlorinatedsanitizers.Regardingwashingwater hygiene,similarresultswereobtainedwhenprocesswash waterwasPAAtreatedorchlorinetreatedinallexperiments carriedoutatindustrialscale.Whenconsidering final productquality,barelyanydifferenceswereobservedwhen usingchlorineorPAAasawatersanitizer.

Moreover,asdemonstratedherein,theuseofasanitizer (PAAorchlorine)inthewashingwaterofminimally processedvegetablesiseffectiveforthegoodmaintenance ofitsmicrobialqualityandforthepreventionofcrosscontaminationduringthewashingprocess.Whenno sanitizerisused,forexample,intheW#2tankinSCN1 orSCN2iniceberglettuceandinbabyleaves,thereisan opportunityforfurtherspreadofthemicrobialloadfromthe washingwatertothevegetables.Therefore,asanitizeragent shouldbeconsideredinatleasttheW #2tankfor maintainingacceptablewaterqualityduringthecomplete process.However,andaccordingtopreviousstudies,itis highlyrecommendedthattomaintainwashwaterunder hygienicconditions,sanitizershouldbeappliedinany singlestepofthewashingprocess.

RegardingthepotentialformationofDBPsinprocessingwater,evenwithchloriteandchlorateconcentrations belowtherecommendedlevelsorlegallimitsestablished forwater,ourresultsrevealedthatchorinetreatments producedimportantconcentrationsofTHMs,chlorates,and chlorites,whereasPAAtreatment,asexpected,didnot generatesignificantamountsofchlorinatedDBPsinwater. Inaddition,whenchlorineisused,thereisaprogressive trendtoaccumulateandincreasethetotalamountofDBPs inwaterasthewashingprocessmovesforward,evenwhen acontinuouswaterrefreshmentisperformed.Moreover,it shouldbetakenintoaccountthatthepresentassayswere performedinatimeframeof1.5hperSCN,whereas

1600 PETRIETAL. J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9

industrialwashingcyclesmaylastupto8h.Underthese conditions,DBPsaccumulationwouldincreaseconsiderably.Whenprocessedproductswereanalyzedforthe differentDBPs,noby-productsweredetectedinanysample orforanydisinfectantused.Presumably,thisisbecause afterwashing,productisrinsedwithWWandcentrifugedto eliminatetheexcesswater,sotheseprocesseseliminateor reducesignificantlytheamountofDBPsthatremainonthe product.Despitethis,weshowwithourexperimentsthat theuseofPAAasawaterdisinfectantavoidsformationof chlorinatedDBPsinwaterandthereforethepotentialriskof productcontaminationandtheenvironmentalimpactofthe effluentscomingfromthewashingprocess.

AlthoughthesuitabilityofPAAassubstituteof chlorinehasbeenprovenfromthemicrobiologicalpoint ofview,aswellastheformationofDBPs,itshouldbe mentionedthattheuseofPAAinthewashingprocess increasestheorganicmattercontent(COD)ofthewash waterduemainlytothecontributionoftheaceticacid presentinthePAAformulations.However,thisincreaseon CODlevelsdoesnotaffectPAAdisinfectionefficacy, whereaschlorineefficacyishighlydependentonthe organicmattercontentinthewashingwater,making necessaryahigherwaterrefreshmentandthereforeahigher rateofwaterconsumption.Thiswouldbeaclear disadvantageofchlorine-baseddisinfectantscomparedwith PAA-baseddisinfectants.Inaddition,largerwaterconsumptionleadstohigherenergyneededtocooldownthe refreshmentwater.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ThisresearchhasbeenfacilitatedbyEurostars(cofundedbyEureka membercountriesandtheEUHorizon2020Frameworkprogramme) undergrantagreementE!11112aqUAFRESH(Combinedstrategiesforthe optimizationofwateruseinthefresh-cutprocessingindustry).

SUPPLEMENTALMATERIAL

Supplementalmaterialassociatedwiththisarticlecanbe foundonlineat:https://doi.org/10.4315/JFP-20-448.s1

REFERENCES

1.Acero,J.L.,F.J.Benitez,F.J.Real,andG.Roldan.2010.Kinetics ofaqueouschlorinationofsomepharmaceuticalsandtheir eliminationfromwatermatrices. WaterRes.44:4158–4170.

2.Adam,L.C.,andG.Gordon.1999.Hypochloriteiondecomposition: effectsoftemperature,ionicstrength,andchlorideion. Inorg.Chem 38:1299–1304.

3.Allende,A.,M.V.Selma,F.López-Gálvez,R.Villaescusa,andM.I. Gil.2008.Roleofcommercialsanitizersandwashingsystemson epiphyticmicroorganismsandsensoryqualityoffresh-cutescarole andlettuce. PostharvestBiol.Technol.49:155–163.

4.Alvaro,J.E.,S.Moreno,F.Dianez,M.Santos,G.Carrasco,andM. Urrestarazu.2009.Effectsofperaceticaciddisinfectantonthe postharvestofsomefreshvegetables. J.FoodEng.95:11–15.

5.Anastassiades,M.,D.I.Kolberg,D.Mack,I.Sigalova,D.Roux,D. Fugel,andD.Dork.2013.Quickmethodfortheanalysisofresidues ofnumeroushighlypolarpesticidesinfoodsofplantorigininvolving simultaneousextractionwithmethanolandLC-MS/MSdetermination(QuPPe-method). Eurl-Srm 1:434.

6.Bachelli,M.,R.Amaral,andB.Benedetti.2014.Alternative sanitizationmethodsforminimallyprocessedlettuceincomparison tosodiumhypochlorite. Braz.J.Microbiol.44:673–678.

7.Banach,J.L.,I.Sampers,S.VanHaute,andH.J.vanderFels-Klerx. 2015.Effectofdisinfectantsonpreventingthecross-contamination ofpathogensinfreshproducewashingwater. Int.J.Environ.Res. PublicHealth 12:8658–8677.

8.Banach,J.L.,H.vanBokhorst-vandeVeen,L.S.vanOverbeek,P. S.vanderZouwen,M.H.Zwietering,andH.J.vanderFels-Klerx. 2020.Effectivenessofaperaceticacidsolutionon Escherichiacoli reductionduringfresh-cutlettuceprocessingatthelaboratoryand industrialscales. Int.J.FoodMicrobiol.321:108537.

9.Baur,S.,R.Klaiber,H.Wei,W.P.Hammes,andR.Carle.2005. Effectoftemperatureandchlorinationofpre-washingwateronshelflifeandphysiologicalpropertiesofready-to-useiceberglettuce. Innov.FoodSci.Emerg.Technol.6:171–182.

10.Beuchat,L.R.,B.B.Adler,andM.M.Lang.2004.Efficacyof chlorineandaperoxyaceticacidsanitizerinkillingListeria monocytogenesonicebergandRomainelettuceusingsimulated commercialprocessingconditions. J.FoodProt.67:1238–1242.

11.CommitteeonToxicityofChemicalsinFood.2006.COTStatement onacommercialsurveyinvestigatingtheoccurrenceofdisinfectants anddisinfectionby-productsinpreparedsalads.Availableat:https:// cot.food.gov.uk/sites/default/ fi les/cot/cotstatementwashaids200614. pdf.Accessed7May2021.

12.Dell’Erba,A.,D.Falsanisi,L.Liberti,M.Notarnicola,andD. Santoro.2007.Disinfectionby-productsformationduringwastewaterdisinfectionwithperaceticacid. Desalination 215:177–186.

13.Du,P.,W.Liu,H.Cao,H.Zhao,andC.-H.Huang.2018.Oxidation ofaminoacidsbyperaceticacid:reactionkinetics,pathwaysand theoreticalcalculations. WaterRes.1:100002.

14.EuropeanUnion.1998.CouncilDirective98/83/ECof3November 1998onthequalityofwaterintendedforhumanconsumption. Off.J. Eur.Union L330:32–54.

15.EuropeanUnion.2020.CommissionRegulation(EU)2020/749of4 June2020amendingAnnexIIItoRegulation(EC)No396/2005of theEuropeanParliamentandoftheCouncilasregardsmaximum residuelevelsforchlorateinoroncertainproducts. Off.J.Eur. Union L70:1–16.

16.Fan,X.,R.Huang,andH.Chen.2017.ApplicationofultravioletC technologyforsurfacedecontaminationoffreshproduce. Trends FoodSci.Technol.70:9–19.

17.Gadelha,J.R.,A.Allende,F.López-Gálvez,P.Fernández,M.I.Gil, andJ.A.Egea.2019.Chemicalrisksassociatedwithready-to-eat vegetables:quantitativeanalysistoestimateformationand/or accumulationofdisinfectionbyproductsduringwashing. EFSAJ 17(Suppl.2):e170913.

18.Garg,N.,J.J.Churey,andD.F.Splitstoesser.1990.Effectof processingconditionsonthemicrofloraoffresh-cutvegetable. J. FoodProt.53:701–703.

19.Garrido,Y.,A.Marín,J.A.Tudela,A.Allende,andM.I.Gil.2019. Chlorateuptakeduringwashingisinfluencedbyproducttypeandcut piecesize,aswellaswashingtimeandwashwatercontent. PostharvestBiol.Technol.151:45–52.

20.Gil,M.I.,A.Marín,S.Andujar,andA.Allende.2016.Should chlorateresiduesbeofconcerninfresh-cutsalads? FoodControl 60:416–421.

21.Gil,M.I.,M.V.Selma,F.López-Gálvez,andA.Allende.2009. Fresh-cutproductsanitationandwashwaterdisinfection:problems andsolutions. Int.J.FoodMicrobiol.134:37–45.

22.Gombas,D.,Y.Luo,J.Brennan,G.Shergill,R.Petran,R.Walsh,H. Hau,K.Khurana,B.Zomorodi,J.Rosen,R.Varley,andK.Deng. 2017.Guidelinestovalidatecontrolofcross-contaminationduring washingoffresh-cutleafyvegetables. J.FoodProt.80:312–330.

23.Gómez-López,V.M.,A.S.Lannoo,M.I.Gil,andA.Allende.2014. Minimumfreechlorineresiduallevelrequiredfortheinactivationof Escherichiacoli O157:H7andtrihalomethanegenerationduring dynamicwashingoffresh-cutspinach. FoodControl 42:132–138.

24.Gómez-López,V.M.,A.Marín,M.S.Medina-Martínez,M.I.Gil, andA.Allende.2013.Generationoftrihalomethaneswithchlorinebasedsanitizersandimpactonmicrobial,nutritionalandsensory qualityofbabyspinach. PostharvestBiol.Technol.85:210–217.

J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9DISINFECTIONSTRATEGIESINFRESH-CUTINDUSTRY 1601

25.Gómez-López,V.M.,P.Ragaert,V.Jeyachchandran,J.Debevere, andF.Devlieghere.2008.Shelf-lifeofminimallyprocessedlettuce andcabbagetreatedwithgaseouschlorinedioxideandcysteine. Int. J.FoodMicrobiol.121:74

83.

26.González,R.J.,Y.Luo,S.Ruiz-Cruz,andJ.L.McEvoy.2004. Efficacyofsanitizerstoinactivate Escherichiacoli O157:H7on fresh-cutcarrotshredsundersimulatedprocesswaterconditions. J. FoodProt.67:2375–2380.

27.Gordon,G.,L.Adam,andB.Bubnis.1995.Minimizingchlorateion formation. J.Am.WaterWorksAssoc.87:97–106.

28.Gu,G.,S.Bolten,J.Mowery,Y.Luo,C.Gulbronson,andX.Nou. 2020.Susceptibilityoffoodbornepathogenstosanitizersinproduce rinsewaterandpotentialinductionofviablebutnon-culturablestate. FoodControl 112:107138.

29.Hilgren,J.A.,andJ.D.Salverda.2006.Antimicrobialefficacyofa peroxyacetic/octanoicacidmixtureinfresh-cut-vegetableprocess waters. J.FoodSci.65:1376–1379.

30.Hrudey,S.E.2009.Chlorinationdisinfectionby-products,public healthrisktradeoffsandme. WaterRes.43:2057–2092.

31.Jay-Russell,M.T.,A.F.Hake,Y.Bengson,A.Thiptara,andT. Nguyen.2014.Prevalenceandcharacterizationof Escherichiacoli and Salmonella strainsisolatedfromstraydogandcoyotefecesina majorleafygreensproductionregionattheUnitedStates-Mexico border. PLoSONE 9:e113433.

32.Jolley,R.L.,andJ.H.Carpenter.1982.Aqueouschemistryof chlorine:chemistry,analysisandenvironmentalfateofreactive oxidantspecies.Technicalreport.OakRidgeNationalLaboratory, OakRidge,TN.

33.JungJung,Y.,K.W.Baek,B.S.Oh,andJ.-W.Kang.2010.An investigationoftheformationofchlorateandperchlorateduring electrolysisusingPt/Tielectrodes:theeffectsofpHandreactive oxygenspeciesandtheresultsofkineticstudies. WaterRes 44:5345

5355.

34.Kaufmann-Horlacher,I.,D.StroherKolberg,C.Wildgrube,A. Benkenstein,E.Scherbaum,andM.Anastassiades.2014.Chlorate residuesinplant-basedfood. Eurl-Srm 116.

35.Kitis,M.2004.Disinfectionofwastewaterwithperaceticacid:a review. Environ.Int.30:47

55.

36.Klaiber,R.G.,S.Baur,G.Wolf,W.P.Hammes,andR.Carle.2005. Qualityofminimallyprocessedcarrotsasaffectedbywarmwater washingandchlorination. Innov.FoodSci.Emerg.Technol.6:351–362.

37.Lee,W.N.,andC.H.Huang.2019.Formationofdisinfection byproductsinwashwaterandlettucebywashingwithsodium hypochloriteandperaceticacidsanitizers. FoodChem.1:100003.

38.López-Gálvez,F.,A.Allende,P.Truchado,A.Martínez-Sánchez,J. A.Tudela,M.V.Selma,andM.I.Gil.2010.Suitabilityofaqueous chlorinedioxideversussodiumhypochloriteasaneffectivesanitizer forpreservingqualityoffresh-cutlettucewhileavoidingby-product formation. PostharvestBiol.Technol.55:53–60.

39.López-Gálvez,F.,M.I.Gil,P.Truchado,M.V.Selma,andA. Allende.2010.Cross-contaminationoffresh-cutlettuceafterashorttermexposureduringpre-washingcannotbecontrolledafter subsequentwashingwithchlorinedioxideorsodiumhypochlorite.

FoodMicrobiol.27:199

204.

40.López-Gálvez,F.,G.D.Posada-Izquierdo,M.V.Selma,F.PérezRodríguez,J.Gobet,M.I.Gil,andA.Allende.2012.Electrochemicaldisinfection:anefficienttreatmenttoinactivate Escherichiacoli

O157:H7inprocesswashwatercontainingorganicmatter. Food Microbiol.30:146–156.

41.Marín,A.,J.A.Tudela,Y.Garrido,S.Albolafio,N.Hernández,S. Andújar,A.Allende,andM.I.Gil.2020.Chlorinatedwashwater andpHregulatorsaffectchlorinegasemissionanddisinfectionbyproducts. Innov.FoodSci.Emerg.Technol.66:102533.

42.Martín-Espada,M.C.,A.D’ors,M.C.Bartolomé,M.Pereira,andS. Sánchez-Fortún.2014.Peraceticaciddisinfectantefficacyagainst Pseudomonasaeruginosa biofilmsonpolystyrenesurfacesand comparisonbetweenmethodstomeasureit. LWT-FoodSci. Technol.56:58–61.

43.Penghui,D.,W.Liu,H.Cao,H.Zhao,andC.-H.Huang.2018. Oxidationofaminoacidsbyperaceticacid:reactionkinetics, pathwaysandtheoreticalcalculations. WaterRes.1:100002.

44.Petri,E.,M.Rodríguez,andS.GarcíadelaTorre.2015.Evaluation ofcombineddisinfectionmethodsforreducing Escherichiacoli O157:H7populationonfresh-cutvegetables. Int.J.Environ.Res. PublicHealth 12:8678–8690.

45.Stanford,B.D.,A.N.Pisarenko,S.A.Snyder,andG.Gordon.2011. Perchlorate,bromate,andchlorateinhypochloritesolutions: guidelinesforutilities. J.Am.WaterWorksAssoc.103:71–83.

46.Stead,R.2004.Timetoreplacechlorinewithnature’sapproachand reapthemarketingandenvironmentalbenefitstharareavailable. CampdenChorleywoodFoodResearchAssociation,Gloucestershire, UK.

47.Sudhaus,N.,H.Nagengast,M.C.Pina-Pérez,A.Martínez,andG. Klein.2014.Effectivenessofaperaceticacid-baseddisinfectant againstsporesof Bacilluscereus underdifferentenvironmental conditions. FoodControl 39:1–7.

48.Suslow,T.1997.Postharvestchlorination.Basicpropertiesandkey pointsforeffectivedisinfection.DivisionofAgricultureandNatural Resources,UniversityofCalifornia.

49.TeroLuukkonen,S.P.2016.Peracidsinwatertreatment:acritical review. Crit.Rev.Environ.Sci.Technol.47:1–39.

50.Tudela,J.A.,F.López-Gálvez,A.Allende,N.Hernández,S. Andújar,A.Marín,Y.Garrido,andM.I.Gil.2019.Operational limitsofsodiumhypochloritefordifferentfreshproducewashwater basedonmicrobialinactivationanddisinfectionby-products(DBPs). FoodControl 104:300–307.

51.U.S.FoodandDrugAministration.2012.CodeofFederal Regulation.Title21 Foodanddrugs Chemicalsusedinwashing ortoassistinthepeelingoffruitsandvegetables,Sec.173.315.U.S. FoodandDrugAdministration,Washington,DC.

52.Vandekinderen,I.,J.Camp,B.Meulenaer,K.Veramme,Q.Denon, P.Ragaert,andF.Devlieghere.2007.Theeffectofthedecontaminationprocessonthemicrobialandnutritionalqualityoffresh-cut vegetables. ActaHortic.746:173–180.

53.Vandekinderen,I.,F.Devlieghere,B.DeMeulenaer,P.Ragaert,and J.VanCamp.2009.Optimizationandevaluationofadecontaminationstepwithperoxyaceticacidforfresh-cutproduce. Food Microbiol.26:882–888.

54.VanHaute,S.,F.López-Gálvez,V.M.Gómez-López,M.Eriksson, F.Devlieghere,A.Allende,andI.Sampers.2015.Methodologyfor modelingthedisinfectionefficiencyoffresh-cutleafyvegetables washwaterappliedonperaceticacidcombinedwithlacticacid. Int. J.FoodMicrobiol.208:102–113.

55.Virto,R.,P.Mañas,I.Álvarez,S.Condon,andJ.Raso.2005. Membranedamageandmicrobialinactivationbychlorineinthe absenceandpresenceofachlorine-demandingsubstrate. Appl. Environ.Microbiol.71:5022–5028.

56.Watson,K.,G.Shaw,F.D.L.Leusch,andN.L.Knight.2012. Chlorinedisinfectionby-productsinwastewatereffluent:bioassaybasedassessmentoftoxicologicalimpact. WaterRes.46:6069–6083.

57.Weng,S.C.,Y.Luo,J.Li,B.Zhou,J.G.Jacangelo,andK.J. Schwab.2016.Assessmentandspeciationofchlorinedemandin fresh-cutproducewashwater. FoodControl 60:543–551.

58.WorldHealthOrganization.2017.Guidelinesfordrinkingwater quality,4thed.WorldHealthOrganization,Geneva.

–

–

–

–

1602 PETRIETAL. J.FoodProt.,Vol.84,No.9