is intended to introduce new collectors to the ways in which the history of the United States can be told through its mail. It is not intended to be a comprehensive look at our nation’s postal operations. Rather, it is my intention that this series of vignettes will inspire the reader to dig deeper on their own, through journals, books, and auction catalogues. I have done my best to select major milestones from the first four decades of the postage stamp’s existence, although if you were to ask another philatelist they might select completely different topics.

Before we begin we must define the term “postal history”, which is generally considered to be the study of rates, routes, and markings found on covers. I like to think of postal history as the investigative journalism of philately: How did the cover reach its destination? Who carried it along the way? When was it sent and when did it arrive? Where did it transit through? What do the different postmarks indicate? Once we can answer these questions, we can consider ourselves a postal historian.

For the purposes of this booklet I have chosen to examine postal history through the lens of adhesive postage stamps, as I believe the jump from stamps to covers is the most natural progression for a collector. Consider The Romance of Postal History, then, to be a bridge between the world of stamp collecting and the world of understanding and appreciating covers.

My goal is simple: to convince you, the reader, that postal history is American history. To explain how the post office grew and evolved to meet the demands of a changing world, and in return how innovations by the post office fundamentally changed the ways in which human beings communicate with one another. To portray stamp collecting as something more than merely mounting rows of stamps into an album. To bring the past to life through the unassuming pieces of mail that have survived all of these decades.

In short, I want to introduce you to the intrigue, the excitement—the romance—of postal history.

Charles Epting CEO of H.R. Harmer

To trace the history of postage stamps in America, we must first take a trip to Great Britain. In 1837, a teacher named Rowland Hill published a pamphlet titled “Post Office Reform its Importance and Practicability”, which advocated for a postal service accessible to all, rather than just the upper class. Hill believed that mail should be sent prepaid and that postage rates should be determined based on weight rather than distance, an idea which was successfully implemented in December of 1839 with the introduction of the Uniform Fourpenny Post. Under this new law, a half-ounce letter sent between any two points in the United Kingdom would cost 4d, regardless of distance. Just 36 days later, on January 10, 1840, this rate was further reduced to one penny for one-ounce letters, and on May 6 of that same year the world’s first adhesive stamp—the Penny Black—was introduced to the world. The influence of Rowland Hill and his postal reform cannot be overstated and paved the way for the proliferation of the post in the United States.

The world’s first adhesive stamp, the Penny Black (left), and contemporary Mulready lettersheets (right), marked the beginning of a new era in communication. Rowland Hill’s humble invention would have an unforetold impact on the entire globe.

The world’s first adhesive stamp, the Penny Black (left), and contemporary Mulready lettersheets (right), marked the beginning of a new era in communication. Rowland Hill’s humble invention would have an unforetold impact on the entire globe.

Itmay come as a surprise that the first postage stamps issued in the United States were not produced by the government, but rather by a private company. Disappointed with the efficiency (or lack thereof) of the United States post office, Henry Thomas Windsor and Alexander M. Greig founded the City Despatch Post in New York City in February 1842. Their business model of delivering mail within the city was so successful that by August of the same year the company was purchased by the government and reorganized as the carrier department of the New York City post office. The City Despatch Post’s stamps came just 21 months after Great Britain issued the world’s first stamps, and predate the issuance of stamps by the federal government by over five years.

The first postage stamps in America were issued by private companies, including New York’s City Despatch Post (left) and the Philadelphia Despatch Post (right). Private posts would continue to operate in competition (and sometimes harmony) with the government for decades.

Priorto 1845 postage rates in America were complex, confusing, expensive, and dependent on both weight and distance. Mirroring what Great Britain had done half a decade earlier, the Postal Act of 1845 overhauled the entire structure by standardizing and reducing rates to 5c for a half-ounce letter sent under 300 miles, or 10c for further distances. Not only did this reform make the mail accessible to more Americans, but it paved the way for postmasters to produce locally-recognized adhesive stamps or stamped envelopes for the prepayment of postage. The philosophy was twofold: stamps would not only make it easier for the public to send mail, but would increase revenue for local post offices. The Postmasters’ Provisionals, as collectors have termed them, were produced by at least 11 municipalities and represent some of the greatest rarities of American philately.

Postmasters’ Provisionals range from beautifully engraved stamps such as the St. Louis Bears (top left) to primitive and utilitarian creations like that of Boscawen, New Hampshire (bottom left). The most famous Provisional is the unique Alexandria, Virginia “Blue Boy” (right).

OnJuly 1, 1847, the first federal postage stamps of the United States were issued. A 5c stamp depicting the nation’s first Postmaster General, Benjamin Franklin, paid for a half-ounce letter being sent under 300 miles, and a 10c stamp of George Washington paid for the same letter sent over 300 miles. Their use was optional at first, as the idea of a postage stamp was not yet ingrained in the minds of the public. These two stamps remained in use for about four years before being replaced by a new series of stamps at the end of July, 1851. The designs of America’s first two postage stamps, produced by the firm of Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Edson, were adapted from banknotes of the time. To this day, both Franklin and Washington remain the two individuals who have appeared on more American stamps than anyone else.

The first federal United States postage stamps came in both a 5c denomination (left) and a 10c denomination for longer distances or heavier letters (right). Benjamin Franklin and George Washington have appeared on more American postage stamps than anyone else.

Postal reforms continued in the 1850s. At this time, letters could be sent with postage either prepaid by the buyer or paid by the recipient upon delivery. Concerned that service was being performed without compensation, the post office made it a priority to encourage the prepayment of postage by reducing the standard rate from 5c to 3c (mail sent collect was still charged 5c). This, combined with an increase in the distance a single-rate letter could be sent from 300 miles to 3,000 miles, meant that essentially the entire country was united under a uniform 3c postal rate. In 1855 the post office mandated that all mail be sent prepaid, while the following year they eliminated the option to pay for a letter with cash—solidifying postage stamps as the sole means of sending a letter.

As postage rates evolved, new stamps were required. This 3c stamp (left) was used July 1, 1851, the first day of the new rates. 5c stamps (center) were typically used on international mail, while 10c stamps (right) generally carried mail to and from California.

Althougheasy to take for granted today, the appearance of perforations marked a major step in the development of postage stamps. Experiments in Great Britain began in the late 1840s, but it was not until 1857 that the United States government issued perforated postage stamps. Primarily featuring the same designs as their predecessors, these stamps were much easier to separate and thereby saved postal clerks a considerable amount of time. Collectors have come to classify perforations according to the number of holes (or teeth) in a two-centimeter span. Today’s selfadhesive postage stamps have no practical need for perforations, although the tradition lives on through simulated die-cut perforations.

While early perforations were experiments created by private individuals (center), the federally first perforated postage stamps ranged in denomination from 1c (right) to 90c (left), with various values in between.

The Pony Express occupies a unique place in American popular culture, having appeared in numerous films and television shows. However, few realize that the Pony Express was a shortlived and expensive service inaccessible to the vast majority of Americans. When first introduced in April 1860, a letter carried via Pony Express cost $5—the equivalent of over $150 in 2022. By October 1861, the cheaper and faster transcontinental telegraph greatly reduced the need for such a service. Therefore, it is perhaps most important to view the Pony Express for the hope and promise it represented to an America on the brink of war—the potential for the rapid, year-round conveyance of mail from coast to coast. Despite its brief duration and the relatively small amount of mail carried by its riders across the American West, the Pony Express remains one of the most significant moments in the development of the American post office.

Of the approximately 250 Pony Express covers that exist today, these three are particularly significant: one carried on the first eastbound trip of the Pony Express (top right), one addressed to Abraham Lincoln (left), and one with a pro-Union patriotic illustration (bottom right).

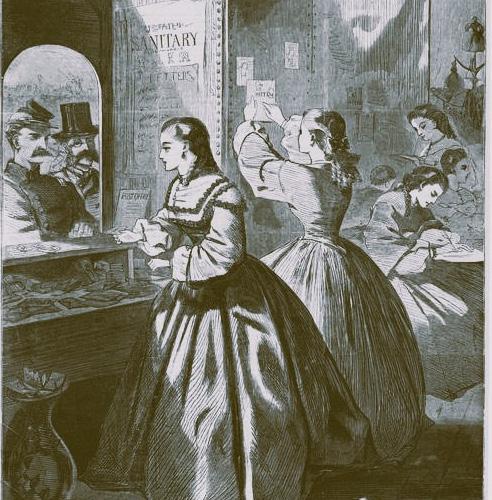

Theoutbreak of the Civil War presented the United States Post Office with an unexpected problem: postage stamps held by Southern post offices represented an asset which could, in theory, have been sold to individuals in the North and thereby advance the Confederate effort. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair ordered the production of new postage stamps in June of 1861 to replace those in use at the time. After a six-day window during which the public could exchange their old stamps for new ones, postmasters were instructed to no longer recognize the validity of any United States postage stamp produced prior to 1861. Despite confusion and logistical challenges, by the end of 1861 Blair’s scheme had been fully implemented. This was the last time United States stamps were demonetized, and all stamps printed from 1861 to the present day are valid for postage.

Attempts to use old postage stamps after the start of the Civil War were flagged by the post office, as seen here (left). A new stamp was required before the letter could be mailed. As the war raged on, both the North (right) and South (center) created decorative envelopes extolling their cause.

Beginningin the 1860s fears began to spread about the cleaning and reuse of cancelled postage stamps. Charles F. Steel, an employee of the National Bank Note Company, created and patented a device which would break the paper fibers of a stamp prior to use, thereby allowing cancelation ink to seep into the paper and discouraging criminal behavior. The embossed pattern produced by such a device is known as a “grill”. Beginning in 1867 and continuing for the next few years a number of different grilling devices were used, all of which have been classified by philatelists according to their size and orientation. By the early 1870s the practice was deemed to be more trouble than it was worth—but not before collectors were left with some of the rarest and most expensive varieties of American postage stamps.

The short lifespan of grilled stamps means that some higher denominations, such as this 90c on a cover to Peru (right), are exceedingly rare. More common grilled stamps can be found with fancy cancellations, such as this tombstone marking the impeachment of Andrew Johnson (left).

to 1869, all United States stamps bore a portrait of one of five men: Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, or Abraham Lincoln. All of that changed in 1869 with the issuance of the “Pictorial Issue”. Ranging from 1c to 90c, the obligatory portraits of Franklin and Washington were included, but so too were designs depicting a post rider on horseback, a locomotive, and the S.S. Adriatic (among others). The locomotive was particularly significant as 1869 also marked the completion of the transcontinental railroad in Utah which greatly expedited the carrying of mail from coast to coast. Public outcry against these unconventional stamps was swift, and after only about 13 months they were replaced by a more traditional series. Today, the Pictorial Issue is prized for both its beauty and its rarity.

The 3c Pictorial Issue depicts a locomotive and was released alongside the completion of the transcontinental railroad. This example (left) bears the popular “Shoo Fly” cancellation of Waterbury, Connecticut. Higher denominations such as the 12c (center) and 24c (right) were primarily used to foreign destinations.

As international communication became more widespread in the mid-19th Century, postal treaties were negotiated between various individual countries which resulted in a confusing and tangled web of rates, routes, and regulations. The cost to send a letter depended not just on what country it was going to, but also what ship it was carried aboard. Spearheaded by German Postmaster-General Heinrich von Stephan, the establishment of the General Postal Union (now the Universal Postal Union) in 1874 allowed for uniform flat rate postage for a letter to any other member country. The UPU predates the United Nations (which it would later become a part of) by over seven decades and was one of the first modern intergovernmental organizations. Since its founding the UPU has been based in Bern, Switzerland.

The creation of the UPU simplified of overseas postage rates, as can be seen on this cover to Italy (right) paying 11 times the standard 5c rate. The triple-rate cover to England (left) bears 15c United States postage and 3d postage for forwarding within the United Kingdom.

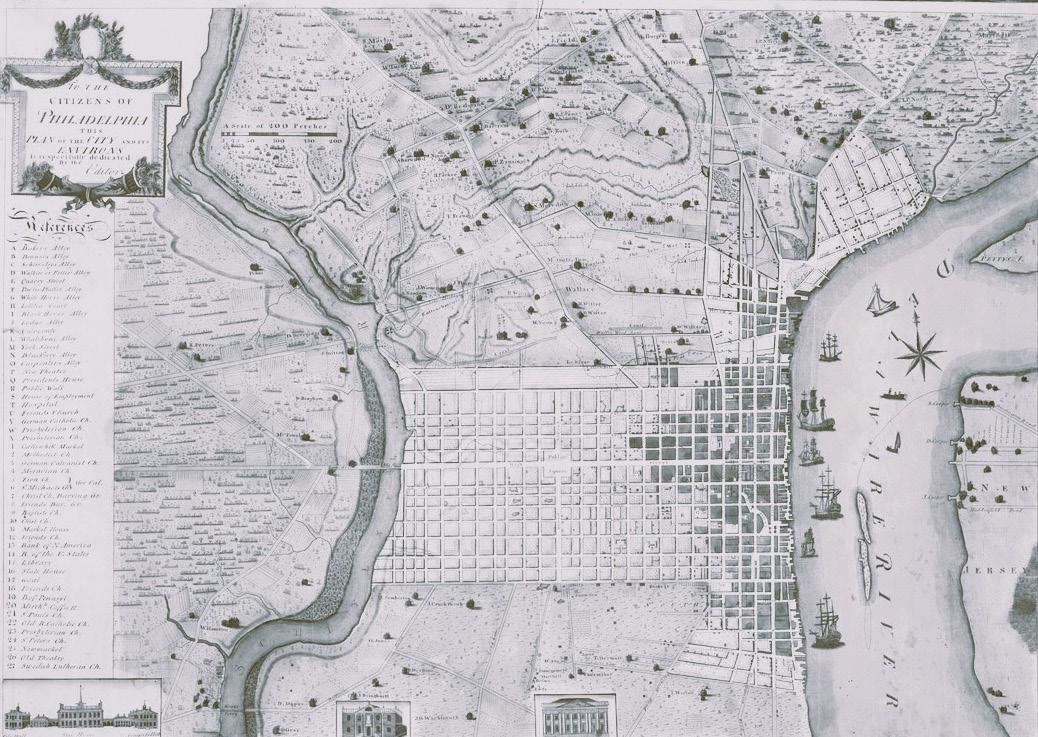

The twelve vignettes presented in this booklet are merely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to postal history. We didn’t touch on the ways in which mail was carried during the colonial era (far left), the time the postal service enacted a tax to repay debts after the War of 1812 (middle left), the express mail service that predated the Pony Express by over two decades (middle right), or the first transatlantic steamships (far right). One could fill entire volumes on these and countless other topics, as many before me have. But every journey must start somewhere, and I hope that the stories we’ve explored have kindled an interest to learn more about our nation’s postal past.

For those who are interested in learning more about American postal history, there are a number of wonderful societies and publications. We invite you to visit the organizations listed here to find out more about the research they are conducting that continues to shed new light on our philatelic past.

H.R. Harmer very quickly became synonymous with high-quality philatelic auctions in our namesake’s native Great Britain. By 1940 it was time for the company to branch out, and a satellite office was opened across the Atlantic in New York City.

H.R. Harmer first rose to prominence in the United States when our firm was selected to sell the collection of the late President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. These auctions were front-page news even in the non-philatelic press, as never before had the stamp collection of such a beloved public figure been made available to collectors.

Over the coming decades, H.R. Harmer would go on to sell two of the most comprehensive and valuable collections ever to cross the auction block—those of Alfred H. Caspary and Alfred F. Lichtenstein, both of which would set new highwater marks in the industry. And, since 2019, H.R. Harmer has been selling the collection of German businessman Erivan Haub—a series of auctions which has once again placed H.R. Harmer at the forefront of the philatelic world.

Today, led by a young and enthusiastic team, H.R. Harmer is still dedicated to providing collectors with the same professional service and philatelic expertise that our company was founded upon all those decades ago.

Alison Sullivan Office Manager & Philatelist

Charles Epting President & CEO

Alison Sullivan Office Manager & Philatelist

Charles Epting President & CEO