Looking ahead in wonder

Farewell lecture

Farewell lecture of Jan D. ten Thije, professor of Intercultural Communication at Utrecht University on Friday 10 June 2022.

Mr. Dean, Dear attendees, Welcome to my farewell lecture.

Over two years ago, I held my inaugural lecture in the auditorium of the Utrecht University Hall (Ten Thije 2020). It was a festive day and a wonderful start as Professor of Intercultural Communication. A month later, the corona epidemic broke out. I have heard from many that my inaugural lecture was their last academic event before the lockdown. Fortunately, we can now move about freely again. However, it was striking that I still received eight cancellations of people who had been struck by Covid; thus, we must remain careful. Because of corona, it was not possible to reserve the auditorium and the senate hall now, as there is a large backlog of inaugural lectures and promotions. That is why I have invited you to this great lecture hall on the Drift. That is also appropriate, as during the past twenty years, I have held many lectures, introductions, information sessions and conferences in this lecture hall. In 2017, we celebrated the 12.5 year anniversary of the master Intercultural Communication here. If the walls could speak, they would tell beautiful stories. I will try to recall a few of them today.

The format of my farewell lecture is as follows. I briefly explain where my love for the profession comes from. Then, I show how the five approaches I discussed in my inaugural lecture have been developed into two books. Next, I discuss examples from my intercultural teaching to show how relevant and inspiring the international classroom is. Not only for students, but also for teachers. Finally, I will show how the project luistertaal developed from a fun experiment in lectures to a guiding principle for the curriculum of language studies and a strategy for multilingual meetings. My closing words of thanks are in pictures. Looking back in wonder, therefore, automatically turns into looking ahead in wonder. Through this, this farewell lecture is an example of

what we call “decentring” in the master Intercultural Communication. This refers to the process in which researchers reflect on their studies by discussing a multitude of cultural perspectives that shape the research (Spencer-Oatey & Franklin 2009).

Looking back in wonder

One of the questions I was often asked by students and colleagues was: where did your interest and enthusiasm for intercultural communication come from? Two years were decisive.

In 1960-1961, my family - I was 5 years old at the time - went to America for a year. My father received a Fullbright scholarship to do research in Philadelphia at the university hospital. Here is the iconic photo of our

family on Liberty Island. I am the smallest boy in the front. It was an impressive - intercultural - year for me. It is always about details. As a small child, I remember visiting a supermarket with ..... shopping carts. We did not have those in the Netherlands yet; we had a grocer who served everyone from behind a counter. In the kitchen in Philadelphia, there was another - up and until then - unknown device, an automatic washing machine. Apparently, I sat in front of it for hours, watching the drum turn. I also went to kindergarten with what you would now call a linguistically and culturally diverse group of children. My first English sentence was, “Can you tell me the way to the bathroom?” It was the year of the election battle between Kennedy and Nixon.

The wonderment for the strange began then. (Interestingly enough, I never went back to America after that.)

The second crucial year was 1973-1974. I had graduated from the gymnasium, but I did not know what I wanted to do. In my family, it was customary to go to university, preferably to study Medicine, but I did not feel like it. I wanted to do something else. With school, we had made a trip to Berlin, and we also visited East Berlin on the other side of the Wall. I found that very interesting; so, I tried to arrange an internship in the GDR, but that proved impossible at the time.

Through intermediaries, I ended up in mental health care. I became a nurse at the Willem Arnts Foundation in Den Dolder, known to people in Utrecht at the time as the “madhouse”: a “single ticket Den Dolder” was a threat to anyone with deviant behaviour. Working withwhat was then called - “feeble-minded youngsters” of my own age was impressive and instructive. This is beautifully exemplified by a poster from that time. On a reflective surface that worked like a mirror, it was written in large letters:

“Ever met a normal person? And, how did you like it?”

That slogan has proved to be a common thread in my later life and work. I have interpreted ‘normal’ ever more broadly and it now covers many aspects of what is meant by diversity today.

In 1974, I was accepted at the University of Amsterdam to study Dutch Studies, and my academic career began.

As many of you know, I worked in Chemnitz from 1996 - 2002. In the GDR era, the city was called Karl Marx Stadt. I was appointed as Ober-Assistant Interkulturelle Kommunikation. This allowed me to deepen my interest in real socialism, which had emerged in 1973. After the Wiedervereinigung, of course, things looked very different. For me and my family, it was an extraordinary intercultural experience full of wonder. Not everything was rosy, by the way.

Working at a foreign university proved to be very instructive. The goal of scientific research and education is, of course, broadly similar to the goal in the Netherlands, but the way in which the path to that goal is shaped is different. The possibility of comparison created an important frame of reference for me to develop the Master Intercultural Communication in Utrecht.

Five approaches elaborated

In this farewell lecture, I want to show how wonder works out in different situations. It is useful to reflect upon changes in the characteristics of intercultural communication.

Before discussing some educational cases, I will briefly recall the five approaches that together define the playing field of Intercultural Communication. I explained them in detail in my inaugural lecture. They are the Contrastive approach, which involves comparing languages and cultures. The Cultural Representation approach, which is about researching image formation, the connection between self-image and the other-image. The Multilingualism approach focuses on research into how mutual understanding can arise in multilingual situations. The Interactive approach studies interpersonal - face to face - communication in multicultural and multilingual situations. Finally, there is the Transfer approach, which studies intercultural competence, training, education, counselling and advice. I used the term mediation in my inaugural lecture to explain the relationship between the five approaches.

Figure 2: Five approaches to Intercultural Communication (ten Thije 2020)

Today, I am proud to present, also on behalf of the other two editors, Roselinde Supheert and Gandolfo Cascio, two books in which the five approaches are elaborated. In figure 3, you can find the table of contents of the publication that Leiden-based Brill Publishers has published in print in 2022 (Supheert, Cascio & ten Thije 2022a,b).

The Riches of Intercultural Communication

Volume 1: Interactive, Contrastive and Cultural Representational Approaches

• Introduction: The Impact of (Non-)essentialism on Defining Intercultural Communication Jan D. ten Thije

PART 1 Interactive Approach

• Discourse-Pragmatic Description - Kristin Bührig and Jan D. ten Thije

• It’s Not All Black and White: Ethnic Self-categorization of Multiethnic Dutch Millennials - Naomi Kok Luìs

• Informal Interpreting in General Practice: Interpreters’ Roles Related to

Trust and Control - Rena Zendedel, Bas van den Putte, Julia van Weert, Maria van den Muijsenbergh and Barbara Schouten

• Gender Studies and Oral History Meet Intercultural CommunicationIzabella Agardi, Arla Gruda, Shu-Yi (Nina) Huang and Berteke Waaldijk

PART 2 Contrastive Approach

• Cultural Filters in Persuasive Texts: A Contrastive Study of the Dutch and Italian IKEA Catalogs - Jan D. ten Thije and Manuela Pinto

• An Analysis of Dutch and German Migration Discourses - Christoph Sauer

PART 3 Cultural Representational Approach

• Cultural Representation in Disney’s Cinderella and its Live-Action Adaptation - Azra Alagić and Roselinde Supheert

• Turkish Transformations Through Italian Eyes - Raniero Speelman

• Fading Romantic Archetypes: Representing Poland in Dutch National Press in 1990 and 2014 - Emmeline Besamusca and Daria van Kolck

Volume 2: Multilingual and Intercultural Competences Approaches

PART 4 Multilingual Approach

• Speaking Dutch in Indonesia: Language and Identity – Martin Everaert, Anne-France Pinget and Dorien Theuns

• The Effect of Migration on Identity: Sociolinguistic Research in a Plurilingual Setting - Elisa Candido

• The Impact of Bilingual Education on Written Language Development of Turkish-German Students’ L2 - Esin Gülbeyaz

• Linguistic Advantages of Bilingualism: The Acquisition of Dutch Pronominal Gender - Elena Tribushinina and Pim Mak

PART 5 Transfer / Intercultural Competence Approach

• Different Frames of Reference [The Thing about Dutch Windows] - Debbie Cole

• Education, Mobility and Higher Education: Fostering Mutual Knowledge through Peer Feedback - Emmanuelle Le Pichon-Vorstman and Michèle Ammouche-Kremers

• English & Cultural Diversity: A Website for Teaching English as a World Language - Bridget van de Grootevheen

• Turning International Experience into Intercultural Learning: Intercultural Ethnographies of Students Abroad - Jana Untiedt and Annelies Messelink

• The Intercultural Deskpad: A Reflection Tool to Enhance Intercultural Competences - Karen Schoutsen, Rosanne Severs and Jan D. ten Thije

Figure 3: Table of Contents of The Riches of Intercultural Communication. Retrieved on 5 September 2022. BRILL Publications – Leiden - https://brill.com/page/Contact/contact

The two volumes contain research by many colleagues who work at Utrecht University at the interface between the two research institutes with which Intercultural Communication is concerned, namely, the Institute for Languages Sciences and the Institute for Cultural Inquiry. Many chapters are written by or with ICC students and PhDs. The books contain articles first presented at the ICC anniversary of 2017, in this very hall.

I am not going to discuss the publication here, but I hope that this text will be able to play a role in further developing the non-essentialist approach to Intercultural Communication in Utrecht and elsewhere in the future. The title is “The Riches” for a reason; we want to emphasise that intercultural communication is about more than solving misunderstandings.

I will, however, briefly elaborate on the concept of the non-essentialist approach. I also talked about this in my inaugural lecture.

From essentialism to non-essentialism

• Intercultural communication is ALL communication between people with a different linguistic and cultural background

• There is ONLY intercultural communication if linguistic and cultural differences are RELEVANT for the course and the outcome of multicultural communication

• There is only intercultural communication if people, through REFLECTION on their own language use and culture, can come to a CHANGE in attitude, knowledge and skills regarding languages and cultures.

Figure 4: Definitions of Intercultural Communication (ten Thije 2020)

As is summarised in figure 4, the definitions of intercultural communication vary. It is about how you define intercultural communication. Can the communication between people with a different language and culture always be called intercultural? After all, that is the everyday definition of intercultural communication. In the ICC master and in the Riches-publication, we develop a more focused

definition that we call non-essentialist.

The process of the non-essentialist naming of communication as intercultural occurs in two steps. Communication can only be called intercultural if linguistic or cultural differences are relevant to the course and outcome of the interaction. A second step provides an even more focused definition: intercultural communication only occurs when people, through reflection on their own language use and culture, come to a change in attitude, knowledge and skills regarding languages and cultures.

In an essentialist view of intercultural communication, a simplification takes place. People are then assigned to a cultural group on the basis of a few - sometimes external - characteristics. On this basis, they are then assigned all kinds of characteristics. The Dutch are direct. Germans are hierarchical. Spaniards are always late.

A non-essentialist approach does not deny such cultural differences, but the attribution should not be done automatically. It is important that people are able to assess the relevance of linguistic and cultural differences in a given situation and reflect on the consequences for themselves and for others.

The discussion about essentialism and non-essentialism also has consequences for how one views diversity. This is a contemporary theme. Does diversity only have to do with the composition of the group or organisation in which you work?

In an essentialist approach, an organisation is diverse when people with different backgrounds or cultural identities work together. From a non-essentialist approach, this is too simple and may even promote stereotypes. It is, of course, important to recognise that cultural and linguistic diversity are also of great importance at the individual level. Many people combine multiple identities in their personalities. They speak and understand several languages, they have a large repertoire

of cultural knowledge and traditions (Cole & Meadows 2013, Nathan 2015).

Depending on the situation and the community in which you operate, one identity is more important than another. You make certain cultural customs and judgements relevant within the given situation. If you look at diversity this way, inclusion in a diverse team is not an automatic outcome, but a responsibility of everyone who can contribute differently in their own way. In her research on table discussions between international students - the so-called Erasmus 2.0 generationMesselink shows how self-identification and other-identification work in such super-diverse communities (Messelink & ten Thije 2012).

Case study 1: Cinzano

The first case study is a Cinzano commercial, which I saw for the first time when I joined the Intercultural Communication programme at the Technical University Chemnitz in 1996. It illustrates one of the variants associated with the rich point in intercultural communication very well. A rich point revolves around the question of what you can do as a foreigner if you do not understand something. According to the

linguistic anthropologist Michael Agar (1994), there are four ways to respond: 1) wait until it is over, 2) do as the native do, 3) blame the other, or 4) start wondering. The last option is called the rich point.

I have used the Cinzano commercial a lot in my teaching. I always watched how students responded to the unexpected turn of events in the video. Based on how their reactions changed over the years, I noticed a shift in the evaluation of representations of transgressive behaviour. To be clear: nowadays I do not think the video can be used anymore, but you please watch it yourself.

For the discussion on (non)essentialism, it is interesting to analyse how the English businessman receives his Japanese partners and offers them a Cinzano as a welcome. He trips over a tiger’s head and accidentally throws the contents of his glass of Cinzano on the bosom of his female colleague, Melissa. The Japanese see this happen, hesitate for a moment, and then proceed to throw their Cinzano on her as well. Subsequently, the Englishman whispers in her ear, “I think they like you.” The question to students each time was how they interpreted this incident. This gave rise to all kinds of reflections, especially the final sentence, which was the subject of much discussion. How can the Englishman say that he thinks the Japanese like his colleague when they are doing something that would normally be considered highly offensive?

We came up with the following interpretation: in the video, the Japanese are confronted with an unexpected incident in a situation unknown to them. They choose the second option: “do as the natives do”. They copy the behaviour of the host. Apparently, the Englishman sees through the dilemma of the Japanese. From this perspective, he understands and appreciates their choice. He tries to save the situation his female colleague is in by saying “I think they like you”. Her facial expression shows that she does not agree.

After the discussion about the excerpt, I gave the students the task of putting themselves in the situation and writing a text in which

they had to express different perspectives, those of the Englishman, the Englishwoman, the Japanese, the Tiger, or Cinzano itself. The discussion of these texts always produced surprising insights into the way you can formulate different perspectives in language. After all, the ability to switch between different perspectives is crucial for mutual understanding in intercultural communication (Ten Thije 2006).

I will never forget one discussion I had with students. It was in 2001, when I was a visiting professor in Vienna. There were three Japanese students in my course at the time. Their reaction showed how valuable the so-called international classroom can be. When they saw the unexpected turn of events in the video, they did not laugh as students usually do. They were angry and - as the discussion revealed - offended. They explained that the three Japanese are stereotyped because of their collective, unreflective, and sexist behaviour. Austrian students actually agreed with them during the discussion. Since then, I have always included the reaction of the Japanese students in my lectures. It exemplifies how the self-identification of those involved influences the interpretation and judgement of cultural representations.

I have since discovered that this video is part of a series of 10 similar advertisements, in which the main characters are always played by the same two actors, Leonard Rossiter and Joan Collins. Each time, the contents of the glass of Cinzano land on the bosom of the woman. Both actors have become famous for this. This Cinzano series was also used in the preparation of the famous series Mad Men, in which Don Draper is a partner of the advertising agency Sterling Cooper on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. Mad Men is set in the 1960s. Anyone who can recall the very popular series will recognise the unequal gender relations that are also represented in the Cinzano advertisement, which were very normal in that time period. In retrospect, it is interesting to realise that the American year of my parents and I, as a child in their family, took place precisely during that time.

With such an art-historical interpretation, I would dare to show the video again as an example of historical research within the cultural representation approach. As an example in an Intercultural Communication lecture, however, I now consider it inappropriate. Discussions with students over the last decades have taught me that.

Case study 2: Saint Nicholas

The second case study is about Saint Nicholas. The racist nature of Zwarte Piet has been a recurring topic of discussion in the Intercultural Communication lectures. I have never published about it; therefore, it is interesting to reflect on it now. After all, our government recently admitted that institutional racism exists in the Netherlands. I will briefly discuss my own development, the societal racism discussion and finally, the way in which Zwarte Piet has played a role in intercultural communication education.

As a family, we were enthusiastic Saint Nicholas celebrators. And we still are. Poems and surprises are an annual creative highlight. To be

honest, when our children were little, Gerda and I also painted their faces black when they wanted to. We thought it was quite normal at the time. As a child, my face was also painted black.

The seed of awareness was planted when, in 1986, as education editor of the magazine Vernieuwing van Opvoeding en Onderwijs (Renewal of Parenting and Education), I collaborated with the magazine AFDRUK to produce a theme issue on anti-racism in education (Ten Thije 1986). The guest editors included Surinamese and Antillean staff members of the ABC, the Amsterdam School and Guidance Service. We had many discussions about racism and how education could play a role in fighting racism. During those discussions, they told me that they didn’t dare take the tram in Amsterdam in December, because they were invariably addressed and laughed at as Zwarte Piet. That is when the penny dropped for me for the first time. This was unacceptable. The celebration of Saint Nicholas did not stop in our family, but continued without Zwarte Piet.

More generally speaking, the figure of Zwarte Piet has deeply divided Dutch society during the past decade (Wekker 2016). A growing group of opponents and a stubborn group of supporters have emerged. The Saint Nicholas News, large retail chains like Hema, and many mayors have all played a role in the societal cultural revaluation of the phenomenon. This development could also be observed in student presentations throughout the years.

I would now like to draw special attention to the role of international students. They could not understand why there was so much fuss about this. For internationals, the rule was “If the N word is taboo, you don’t have to think long about Zwarte Piet”. As an Intercultural Communication teacher, I thought about how to make internationals experience and understand the impact of the discussion about Zwarte Piet in the Netherlands.

When I was invited on 5 December 2017 to give a guest lecture in the course Multilingualism and Mediation, my colleague Karen Schoutsen and I saw an opportunity. Would it not be possible for me to spend the first fifteen minutes of the lecture dressed up as Sinterklaas and explain this fierce social discussion? No sooner said than done.

At the start of the lecture, Karen excused me for being late because the train from Amsterdam had been delayed. A little later, someone knocked on the door and Saint Nicholas came in. Dutch students laughed heartily. Internationals looked at each other, not understanding. Karen welcomed me. I sat down and told the story of Saint Nicholas and tried to explain why he is so important to many Dutch people.

The core of my story as Saint Nicholas was as follows. Small children are told by their parents that Saint Nicholas exists, and hands out presents on 5 December. Children are deeply impressed. They put on their shoes and sing songs at home, at day care and at school. This means that in the weeks before Saint Nicholas, the Netherlands is divided into two cultural groups: children who believe in Sinterklaas and adults who do not believe but pretend Sinterklaas really exists. When children grow older, they discover - or are told - that Saint Nicholas does not exist.

Some children are really confused and angry that their parents have lied to them about Saint Nicholas. After that, most of them like to play the adults’ game for their little brothers, sisters or neighbourhood children.

The process that children go through can be described in terms of a “rite of passage”: children experience the transition from the group that believes in Saint Nicholas to the group that no longer believes. The cultural importance of Saint Nicholas is nicely characterised by this rite of passage. It makes it understandable why Sinterklaas is so deeply rooted in Dutch culture.

This interpretation may contribute to a solution for the discussion about Zwarte Piet. For the survival of the phenomenon of Saint Nicholas, we do not need Piet at all. The collective rite of passage of children is the core of the celebration and the justification for the continued existence of the Saint Nicholas holiday. The collective play for small children is far too much fun.

At the time, I explained the core of my existence as Saint Nicholas to locals and internationals. My story was met with interest.

For one international, my performance had a special impact. During my story, this Chinese student entered the lecture hall. She was late and freaked out when she saw me. She sat down and waited until the situation she did not understand at all “would pass by itself”. I finished my story and left as Saint Nicholas. A little later, I returned as the guest lecturer. I apologised for my delay and expressed great surprise when the students told me that Saint Nicholas had visited: “No, it wasn’t me.”

In the ensuing discussion, I asked the Dutch students who used to believe in Sinterklaas. They all raised their hands, to the amazement of the internationals. All in all, it was a great lecture, in which I also explained the five ICC approaches.

But the best thing happened afterwards. I left the classroom, and the

Chinese student came up behind me and whispered: “It was you, wasn’t it”. I looked at her and said, “Yes, you’re right”. I saw the relief in her eyes and realised that a small rite of passage had taken place here.

This Saint Nicholas discussion shows how inspiring the international classroom is for the development of intercultural competences. The different variants related to the Rich Point pass by as if by themselves. It is nice to see how the diversity of the group determines the common learning process. Internationals learn something different from locals, but they do learn it from each other.

The beauty of it is that if you, as a teacher, gear your teaching to social developments, you also learn all the time. And to reassure the Education Director: in my entire career at the UU, I have only once pretended to be Saint Nicholas.

Project: Luistertaal

In the second part of this farewell lecture, I would like to discuss with you some cases related to a research project I have been working on for years. For that, you can first watch a video (please see the link included with picture 6).

In 2019, I happened to watch a knowledge quiz on television in which students from different universities were competing. To my amazement, I saw the following clip, in which a question on luistertaal is being asked.

It is a hilarious fragment. One of the students immediately knows the answer to the question that is shown in picture 6. This amazes the quizmaster Harm Edens, who had never heard of the notion luistertaal. The student explains that a teacher - Jan ten Thije - of his educational programme Communication and Information Sciences (CIW) at Utrecht University researches luistertaal and often talks about

Picture 6: De Universiteitsstrijd, 29 September 2016, Season 1, Episode 14, semifinals Utrecht University against the University of Amsterdam, 20:10-20.14. Question: “What is the name of the form of communication in which you both continue to speak your own mother tongue?”: https://www.npostart.nl/de-universiteitsstrijd/29-09-2016/ VPWON_1259303?utm_medium=refferal&utm_source=tvblik

it enthusiastically. Laughter all around. The subsequent explanation of luistertaal by the quizmaster is perfect, including a stereotypical innuendo about the Dutch-German conversations in a large sand pit at the Dutch beach.

Of course, I find the fact that luistertaal made it into a question in a national quiz honourable. As a scientist, you might aspire to win the Nobel Prize or be rewarded with a Spinoza Prize. I am already very pleased that the concept of luistertaal, which I developed, is part of a national knowledge quiz. After all, not everyone can say that about the social impact of their research.

I would like to tell you how luistertaal originated in student education and, subsequently, contributed to national and international projects.

Luistertaal in lectures

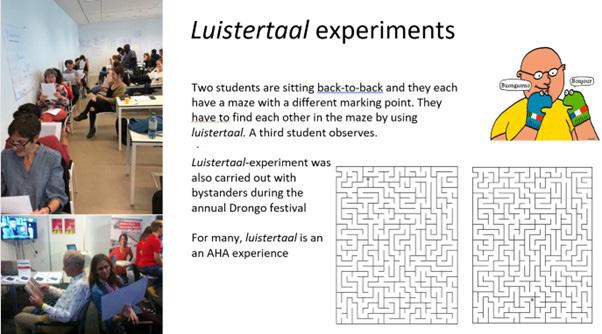

As you can see from the picture in figure 5, I have been experimenting with luistertaal in recent years with different new groups of students. Here, too, the linguistic diversity of the group was a prerequisite for the success of the learning process. We also did this experiment at the annual DRONGO festival on multilingualism. On the bottom left, you can see my esteemed colleague Debbie Cole with my former Linguistics teacher and later colleague René Appel. They are doing a luistertaal experiment similar to the students.

In the experiment, two people are given the same maze in which a point is marked in a different place. They have to find the other person’s point in the maze. Then, one leads the other through the maze to their own point. In doing so, they speak different languages and understand the other person’s language. They are seated with their backs to each other, because they are not allowed to use non-verbal communication. It is an exercise in luistertaal.

In my courses, I made an inventory of the receptive and productive skills of the participants in the experiment beforehand. Then I put together pairs, estimating which combinations might be successful and which might have difficulty understanding each other. The linguistic relationship between the two languages, the foreign language skills learned, the language attitude, and the exposure to and experience with luistertaal play a role.

The experiment has always been appreciated. The two participants are captivated by the difficult maze, as you can see. A third person observes how the students tackle it. Sometimes, I made recordings of the pairs and students and then analysed their transcripts to find multilingual patterns. Because it was about their own experiences with luistertaal, the students were often even more motivated to work on it. Of course, I also explain to the students that this experiment is learning-based research that does not meet all the criteria of experimental interaction research, such as performed by Daria Bahtina, who developed luistertaal between Russian and Estonian participants in her research (Bahtina-Jantsikene 2013).

For many students, the experiment is their first experience with luistertaal. It turns out to be an AHA experience when they find out that they can communicate with someone who speaks a different language, and still understand each other. Other students say afterwards that they realise that they use this form of multilingual communication at home, for example, to talk to their grandparents, who speak another language that they can understand but do not speak.

These students are happy that they can now use the word Luistertaal or Lingua Receptiva as an international term for a linguistic phenomenon that was already part of their everyday reality, but of which they did not know that it had a commonly accepted name (Rehbein et al 2012; ten Thije et al 2017).

This awareness of multilingualism is a broader phenomenon with a historical background. In Europe, since the 19th century, national states

have been established on the principle of one country, one culture, one language. This is also how it works at school nowadays, with the different languages being taught in different school subjects. Fortunately, more and more attention is being paid to multilingualism, which children bring with them from outside their school and which can play a role in making themselves understood at school. Multilingualism appears to be a fruitful strategy for learning to use a language via another language.

Figure 6: Publications of the Dutch Language Union on Luistertaal: https://taalunie.org/ dossiers/63/luistertaal

I am, therefore, very pleased about the cooperation with the Dutch Language Union, which has embraced the concept of luistertaal for a number of years. The Dutch Language Union is interested in exploring how multilingualism can play a role in helping children and adults to learn the Dutch language, both in the Netherlands and in Flanders. In doing so, the Dutch Language Union emphasises that luistertaal is not the only solution, but one of the strategies people employ to communicate multilingually. In 2016, together with colleagues from the Dutch Language Union, we wrote a position paper for the European Commission and, later, two reports presenting practices and examples of luistertaal. I have always found the cooperation with Mieke Smits, Kevin de Coninck and Kris van der Poel, now secretary of the Dutch Language Union, to be very inspiring. Within Utrecht University, Stefan Sudhoff, Emmy Gulikers, Karen Schoutsen and Kimberly Naber were involved.

It is important to point out that there is a direct relationship between the luistertaal experiments I just discussed and the cooperation with social organisations such as the Dutch Language Union. Education and research are thus concretely linked and strengthen each other. Various Intercultural Communication students have written internship reports or theses for the Dutch Language Union in recent years. Thus, valorisation works both ways.

Future of education in modern foreign languages

Via the Dutch Language Union, I arrive at the role that multilingualism can play in the future for language studies. After all, through the masters Intercultural Communication, I have worked a great deal with the departments at Utrecht University that provide the bachelor’s programmes in the modern languages French, German, Spanish, Italian and English, as well as the degree programmes in Dutch Studies and in Communication and Information Sciences (CIW). After all, those are the preparatory programmes for the ICC master’s programme. As you have been able to read in the newspapers for years, the departments of small modern languages are facing issues because too few students opt for these programmes. There is also less interest in Dutch Studies. When I myself started studying Dutch at the University of Amsterdam in 1974, I was one of three hundred first-year students. Nowadays, there are no more than 50 first-year students in Dutch Studies, and the number for the other modern languages is even lower. That is a big problem, which the Ministry has also recognised. Due to the reduced student enrolment, there are also too few subject teachers who can teach the languages in question in secondary education. However, there is a lot of interest in courses such as Communication and Information Sciences (CIW) and Media Studies. Something needs to change in the set-up and structure of the degree programmes for language studies. That is clear. The big question is just: how.

Perspectiefnummer Meertalige perspectief voor de Nederlandse Taalbeheersing

• Meertalig perspectief voor de Nederlandse taalbeheersing, Jan D. ten Thije

• Meertaligheid in Interactie-onderzoek, Tom Koole (Groningen)

• Weg met Non-nativeness, Margot van Mulken (Nijmegen)

• Meertaligheid en tekst- en cultuurverklaring: de toekomst van het schoolvak Nederlands, Els Stronks (Utrecht)

• Doe normaal in meer dan één taal! Marije Michel (Groningen)

• Een examen in meertaligheid: Een reactie op de reacties van collega’s, Jan D. ten Thije

Figure 7: Perspective issue of Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing on multilingualism (2022)

Fortunately, in recent years, several initiatives have been developed by the European Commission to spark the interest of prospective students in language programmes (Berthoud & Gajo 2020). In the Netherlands, you can think of the proposals of curriculum.nu (2019). Multilingualism and intercultural communication are mentioned as a common denominator under which language programmes could work together. The Ministry of Education and Science is prepared to free a lot of money to promote cooperation between universities. To this end, universities must draw up a sector plan in which new solutions are proposed to attract more students.

I was honoured when the editors of the Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing invited me to write the opening article for a theme issue on the Perspectives on Taalbeheersing (Perspectives on Communication and Discourse Studies) in our Time.

Unsurprisingly, I have tried to elaborate on the concept of receptive

multilingualism or luistertaal as one of the common grounds for the renewal of language programmes. Through multilingualism, modern languages can also learn from and collaborate with linguists and communication scholars. This may also account for new perspectives in the labour market. For those who wish to read the details of my argument, I refer to this theme issue (Ten Thije 2022). There, you will also find interesting reactions from colleagues (please see figure 7).

Project Multilingualism and Participation

That brings me to the third part of the luistertaal project. With this, I mean the Multilingualism and Participation - or M&M project - about which we had a wonderful colloquium on 10 June 2022. I would like to give you the gist as a conclusion to my speech. After my formal retirement in November 2021, I was specially appointed by the Executive Board to bring this project to a successful conclusion.

My dissertation, which I published together with Tom Koole in 1994, dealt with intercultural meetings in educational consultancy organisations. The M&M project is concerned with multilingual meetings. That completes a circle. At the time, the research dealt with team meetings between colleagues with a Dutch, Turkish, Moroccan or Surinamese/Antillean background in Dutch. The colleagues with a migration background had to get used to the Dutch language and Dutch meeting culture and the endless polderen (compromising) that is common here. Reaching a common consensus is very important. This is also evident in the M&M project.

The M&M project consults with participation bodies in which Dutch and international council members confer with each other. The big question now is how these participatory bodies - such as the university council, but also faculty councils or education committees - deal with multilingualism.

When two international students were elected to the University Council two years ago, the UU Executive Board explicitly chose not to switch to English like many other universities, but to try out and support multilingualism and the use of luistertaal between Dutch and English (Naber & Ten Thije 2020). At the same time, the Executive Board had set up a committee to develop a formal language policy. The core of the new language policy is that UU is a bilingual university, in which the use of both English and Dutch in education and participation is facilitated. On 23 May 2022, the University Council approved this new language policy (Universiteit Utrecht 2022).

With this, Utrecht is leading the way in the Netherlands in the discussion about the implementation of the upcoming legislation on Language and Accessibility.

Project Multilingualism and Participation (2019-2022)

• Toolkit and workshops on multilingual meetings (Naber 2021)

• Receptive Dutch Course aimed at participatory bodies (B1-C1)

• Choice model language policy (which policy fits which situation?) (Groothoff et al 2022)

• Best Practices multilingualism (briefing of interpreters, translation protocol (Van der Bijl 2022), list of keywords, etc.)

Figure 8: Results of the project Multilingualism and Participation

The M&M project tried to develop many new insights on the applicability of luistertaal in university participatory bodies. The project members were Kimberley Mulder, Frederike Groothoff, Stefan Sudhoff, Trenton Hagar, Saskia Spee, Kimberly Naber (project coordinator), Annick van der Bijl, Bridget van de Grootevheen (interpreter) and Jan D. ten Thije (project leader).

We soon found out that the internationals needed an interpreter in order to participate (Van der Bijl 2022). It was also necessary to make the Dutch council members explicitly aware of their role in ensuring mutual understanding. To this end, we developed a workshop and a toolkit for multilingual meetings (Naber 2021).

Course Multilingual meetings – Receptive Dutch for employee and student representatives

Theme 1 Employee and student representation, how does it work?

Theme 2 The education and examination regulations (OER)

Thema 3 Diversity and Inclusion

Theme 4 Language policy

Theme 5 Working at the university

Theme 6 Finances and repetition

Figure 9: Information project Multilingualism and Participation via link: https://www.uu.nl/ organisatie/bestuur-en-organisatie/medezeggenschap/meertaligheid-in-de-medezeggenschap

Finally, we developed a receptive Dutch course for employee and student representatives based on authentic material from U-council meetings. It is very interesting to see how insight into the functioning of the council and learning receptive Dutch go hand in hand. To be clear: the teacher in this course speaks Dutch, the course is in Dutch, but the students answer in English. This does not mean that they never speak Dutch and sometimes, they would like to, but the aim is to be able to understand Dutch receptively at a high level.

It is clear that Utrecht University, by opting for a bilingual language policy and facilitating bilingual Dutch-English meetings, is taking a different course than many other universities that have opted for English only. It also became clear in the research of the M&M project that different faculties make different choices. The language solution depends on the needs and possibilities of those involved.

This is exactly what the research on luistertaal shows in other contexts (Backus et al 2013; ten Thije 2018; Gulikers et al 2021). Luistertaal is not the solution: it is a solution that exists alongside other solutions. It is important that language users themselves are aware of the different possibilities and can, in each meeting, choose the form of multilingualism that best meets the competences of the people involved at that given instance. In doing so, it is important that the university and the Board of Directors wholeheartedly propagate their choice for bilingualism, so

that everyone feels responsible for inclusiveness within the multilingual academic community.

Looking back over the past ten years, it is interesting to note that the concept of ‘luistertaal’ has developed from a strategy in the border region between Dutch and German colleagues (Beerkens 2013) - or in a pit on the Dutch beach - to becoming a part of the bilingual language policy of Utrecht University, among others, and is now also mentioned in publications by the Foundation for Curriculum Development (2017; 2018) and Curriculum.nu (2019).

Luistertaal is seen as a concept that can provide interesting cross-links between traditionally separate school subjects in secondary education.

In the field of education, more and more voices are heard calling for a different interpretation of the traditional final examination in modern languages and Dutch. When you take a different perspective, you see a different element of reality. It is about looking ahead in wonder.

In the luistertaal project, I have shown that I strive in my teaching and research to make a positive contribution to improving the world by moving towards more justice with respect for linguistic and cultural diversity. Other recent examples of cooperation with social organisations can be found in the publication of Beerkens et al (2020), in which the fruitful collaboration between ICC master students and policy makers, businesses, educational institutions and non-profit organisations is described. A final example is the cooperation with the Regioplan in The Hague, in which a field research into information transfer of the Central Agency for the reception of Asylum Seekers (COA) to asylum seekers was done (Mack, et al 2021).

Setting up such intercultural and multilingual research was by no means always easy, and I have clearly experienced pushback. But I have also learned from my experiences in different countries and universities to think in small steps, and to see how these small steps fit into a larger whole and into a broader vision. Decentring has appeared to be a

permanent process. That puts matters into perspective and encourages. It is what keeps you going. The collaboration with students, alumni, and colleagues has constantly inspired me to connect science with societal practices.

Recently, we submitted a new project to NWO Open Competition as a follow-up to the M&M project (De Graaff 2022). This proposal has been reviewed as excellent and will start in January 2023. That also feels as the icing on the cake of my work: what a successful quiz question can lead to. As an emeritus, I hope to be able to supervise PHDs in research areas such as luistertaal, multilingualism, and intercultural communication, which are close to my heart. Furthermore, I wish students, alumni, colleagues - teachers, support staff and policy makers - great success in shaping the important changes that will be made in order to align academia with the multilingual and culturally diverse society, with all the paradoxes and conflicts that will be faced in that process.

Acknowledgements

Finally, I would like to thank all professors, colleagues, support staff, students, alumni, friends, and family for the cooperation and support I have enjoyed throughout my career. I would like to thank the colleagues who have nominated me as professor with the Executive Board. I cannot mention all the names here.

To conclude, I would like to show you some pictures of key figures from the past years. To start, you can see in picture 7 the closing meeting of the master visitation in 2019. Visitations are crucial at the university. This is when it is assessed whether you are allowed to continue. Hundreds of hours are spent on preparation, mostly on top of regular tasks. The output and student evaluations all must be in order. In my career, I have experienced this a few times. Fortunately, ICC always did fine with an excellent output of around 90 percent after one or two years, as you can see in the Figure 10.

Figure

For the future of the ICC master, it is crucial that Christopher Jenks has been appointed the new professor of Intercultural Communication from August 2022. The chair, which I held for the first time, will thus be continued, which is gratifying. Moreover, the new professor will have their department together with the professor of Translation Studies, Haidee Kotze. This is also very important for the much-needed continuity in personnel policy. I have made a strong case for this during the recent years. It is good that the new department is now being set up. It means we can look forward to the next master visitation with confidence.

Picture 8: Education coordinators Department Languages, Literature and Communication. Picture: Jan ten Thije

I would like to thank one important group of colleagues in this administrative process. You can see them in picture 8. When I entered the room for the results of the visitation, three colleagues were already there. They were Marloes Herijgers, Marion Vonk and Hanna Muis. At the time, they were the Education Coordinators responsible for supporting the master’s. They were very motivated and were waiting anxiously for the outcome. They laughed a lot when I made a remark about this.

At this point, I would like to thank not only these three colleagues but also all the other non-teaching staff. I am thinking of colleagues from the Graduation Office, the Management Coordinators, the Examination Office, the education administration, the Research Support Office, the study advisors, the reception, the technical service, and the IT service desk. In my pursuit of innovation in education and research, I have received support from all of you in the day-to-day organisation of the master’s programme and my research.

The following picture was taken at my farewell to my immediate colleagues of the master Intercultural Communication. That was a year ago, and all online by necessity. What is striking when I look at the photo now, is that of these 17 colleagues, five have left because their contract expired. Fortunately, two others were given permanent contracts. With an own department and a new professor, there will be more continuity.

For those of you who were wondering today what beautiful shoes Jan is wearing today, I can tell you that my ICC colleagues gave me these on my farewell (see picture 9). I wear them with very good memories in mind.

Picture 10 shows the annual group photos of the ICC students taken outside in the garden in front of this building. I had these pictures put up on the closet in my office. We had a fantastic event with ICC alumni before this farewell lecture, and I also received hundreds of positive responses via LinkedIn. Many thanks for the inspiring contacts. I hope this farewell lecture illustrates how important your diversity has

been for my teaching, but also for the research and its social valorisation. You contribute to the fact that diversity actually makes society more inclusive.

Finally, I would like to thank the people who have helped to organise today’s festive event. They are Annick van der Bijl, Debbie Cole, Frederike Groothoff, Jacqueline van Lier, Naomi Kok Luis, Kimberley Mulder, Kimberly Naber, Karen Schoutsen, Pim ten Thije, Ralph Vermeulen and Rena Zendedel.

The last picture shows my loved ones in the environment that has allowed me to rest and recharge my batteries throughout my life. Otherwise, I would not be standing here so healthy. The love of Ot, Koos and Anouk, of Pim and Margot, and of Gerda in particular was my daily motor.

Picture 11: Ten Thije family

Many thanks for your attention.

All the best to you!

References

Agar, M. (1994). Language Shock, Understanding the Culture of Conversation. New York: Harper Collins.

Bahtina-Jantsikene, D. (2013). Lingua Receptiva in Estonian-Russian communication. LOT Number: 338. Utrecht University.

Backus, A., Gorter, D., Knapp, K., Schjerve-Rindler, R., Swanenberg, J., Thije, J.D. ten, and Vetter, E. (2013). Inclusive Multilingualism: Concept, Modes and Implications. European Journal of Applied Linguistics 1 (2), 179–215.

Beerkens, R. (2010). Receptive multilingualism as a language mode in the DutchGerman border area. Münster: Waxmann Verlag.

Beerkens, R., Le Pichon-Vorstman, E., Supheert, R., and Thije, J.D. ten (eds.) (2020). Enhancing intercultural communication in organizations: insights from project advisers. New York and London: Routledge.

Berthoud, A.-C. and Gajo, L. (2020). The Multilingual Challenge for the Construction and Transmission of Scientific Knowledge, Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bijl, A. van der (2022). Analysis and Evaluation of Interpreted Utrecht University Council Meetings. Internship report Intercultural Communication. Utrecht University.

Cole, D. and Meadows, B. (2013). Avoiding the essentialist trap in intercultural education. Using critical discourse analysis to read nationalist ideologies in the language classroom. In F. Dervin & A.J. Liddicoat (eds.). Linguistics for Intercultural Education, 29-47. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Curriculum.nu (2019). Leergebied Engels /MVT. Voorstel voor de basis van de herziening van de kerndoelen en eindtermen van de leraren en schoolleiders uit het ontwikkelteam Engels / Moderne Vreemde Talen. Accessed at 21 december 2021 op: https://www.curriculum.nu/ voorstellen/engels-mvt/ Graaff, R. de (2022). Getting to the CoRe: a Communicative Receptive approach to language learning and mutual understanding in multilingual academic contexts Open Competitieaanvraag 2022.

Groothoff, F. Mulder, K., Naber, K., Hagar, T., and Thije, J.D. ten (2022). How to be inclusive without excluding others? Medezeggenschap & Meertaligheid op de Universiteit Utrecht (luistertaal/lingua receptiva) Eindrapport van het Project Meertaligheid en Medezeggenschap. Universiteit Utrecht.

Gulikers, E., Thije, J.D. ten en Smits, M. (2021) Luistertaal-etalage. De potentie van Luistertaal in onderwijs, professionalisering en samenwerkingsverbanden Inventarisatie en beschrijving. Den Haag: De Nederlandse Taalunie & Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht.

KNAW (2017). Nederlands en/of Engels, Taalkeuze met beleid in het Nederlands hoger onderwijs, Amsterdam: KNAW.

KNAW (2018). Talen voor Nederland, Amsterdam: KNAW. Koole, T. & Thije, J.D. ten (1994). The Construction of Intercultural Discourse. Team discussions of educational advisers. Amsterdam and Atlanta: RODOPI. Mack, A., Klaver, J., Ljujic, V., Versteegt, I. en Thije, J.D. ten (2021). Eindrapportage Informatieoverdracht COA. Den Haag, Regioplan, Universiteit Utrecht en Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum. Accessed at 5 september 2022: https://repository.wodc.nl/bitstream/ handle/20.500.12832/3145/3159-informatieoverdracht-coa-volledigetekst.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Messelink, A. and Thije, J.D. ten (2012). Unity in Super-diversity: European capacity and intercultural inquisitiveness of the Erasmus generation 2.0. Dutch Journal for Applied Linguistics (DuJAL) 1(1), 81-10. Naber, K. (2021). Toolkit Meertalig Vergaderen. Kennisbank op Intranet Universiteit Utrecht. Accessed at 5 september 2022: https://intranet. uu.nl/kennisbank/toolkit-meertalig-vergaderen

Naber, K. en Thije, J.D. ten (2020). Waarom er voor het Nederlands EN het Engels plek moet zijn in de U-Raad, DUB, maart 2021. Accessed at 8 september 2022: https://www.dub.uu.nl/en/opinion/why-thereshould-be-place-both-english-and-dutch-university-council

Nathan, G. (2015). A non-essentialist model of culture: Implications of identity, agency and structure within multinational/ multicultural organizations. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management Vol. 15(1), 101–124.

Rehbein, J., Thije, J.D. ten, and Verschik, A. (2012). Lingua Receptiva (LaRa) – Introductory remarks on the quintessence of Receptive Multilingualism. Special Issue on “Lingua Receptiva”. The International Journal of Bilingualism 16 (3), 248-264.

Spencer-Oatey, H. and Franklin, P. (2009). Intercultural Interaction. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Intercultural Communication. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Supheert, R., Cascio, G. and Thije, J.D. ten (eds.) (2023a) The Riches of Intercultural Communication (Vol. 1) Interactive, Contrastive and Cultural Representational Approaches. Leiden: Brill.

Supheert, R., Cascio, G. and Thije, J.D. ten (eds.) (2023b) The Riches of Intercultural Communication (Vol. 2) Multilingual and Intercultural Competences Approaches. Leiden: Brill.

Thije, J.D. ten (1986). Anti-racisme en onderwijs. Themanummer: Afdruk / Vernieuwing van Opvoeding, Onderwijs en Maatschappij, 45(5), 1-64.

Thije, J.D. ten (2006). The notion of perspective’ and ‘perspectivising’ in intercultural communication research. In K. Bührig & J.D. ten Thije, (eds.). Beyond Misunderstanding. The linguistic analysis of intercultural communication, 97-153. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Thije, J.D. ten (2018). Receptive multilingualism. In D. Singleton & L. Aronin (eds.). Twelve Lectures on Multilingualism, 327-363. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Thije, J.D. ten (2020). Intercultural Communication as Mediation. Inaugural lecture Utrecht University. Accessed at 5 september 2022: https://issuu.com/ humanitiesuu/docs/oratie-jan-ten-thije_2020_en_totaal

Thije, J.D. ten (2022). Meertalig perspectief voor de Nederlandse taalbeheersing. Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing, 44/1, 3-24.

Thije, J.D. ten, Gooskens, Ch., Daems, F., Cornips, L., & Smits, M. (2017). Lingua receptiva: Position paper on the European Commission’s Skills Agenda. European Journal for Applied Linguistics (EuJAL), 5(1), 141-146.

Thije, J.D. ten, Gulikers, E. & Schoutsen, K. (2020). Het gebruik van Luistertaal in de praktijk. Een onderzoek naar meertaligheid in de bouw, de gezondheidszorg en het onderwijs in Nederland en Vlaanderen. Den Haag: De Nederlandse Taalunie en Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht.

Universiteit Utrecht (2021). Meertaligheid in de medezeggenschap. Accessed at 21 december 2021 op https://www.uu.nl/organisatie/bestuur-en-organisa tie/medezeggenschap/meertaligheid-in-de-medezeggenschap Universiteit Utrecht (2022). Taalbeleid Universiteit Utrecht. Utrecht Universiteit. Accessed at 5 september 2022: https://www.uu.nl/sites/default/files/ Language%20Policy%20Utrecht%20University.pdf

Wekker, G. (2016). Witte onschuld. Paradoxen van kolonialisme en ras. Amsterdam: AUP.

Curriculum vitae

Jan D. ten Thije is professor emeritus Intercultural Communication at the Department of Languages, Literature and Communication & and the Utrecht Institute for Language Studies Utrecht University.

He was previously attached to the Institut für Interkulturelle Kommunikation of the Chemnitz University of Technology (19962002) as a ‘Hochschuldozent’, as a visiting professor at the Institut für Angewandte Sprachwissenschaft of the University of Vienna (2001) and as a lecturer/researcher at the Institute for General Linguistics of the University of Amsterdam (1994-1996).

He studied Dutch Language and Literature and General Linguistics at the University of Amsterdam and obtained his PhD at the Utrecht University (1994) on research into intercultural communication in educational advisory institutions.

His interest and expertise lies in the field of institutional and intercultural communication in multicultural and international organisations, lingua receptiva, (receptive) multilingualism, intercultural training, language education and functional pragmatics

He coordinated the Master’s programme in Intercultural Communication at the Department of Languages, Literature and Communication at Utrecht University in period of 2006 - 2019.

Jan D. ten Thije is editor of the European Journal of Applied Linguistics (EuJAL) published by Mouton de Gruyter and series editor of the Utrecht Studies in Language and Communication (USLC) published by Brill Publications, Leiden.

More information: www.jantenthije.eu www.luistertaal.nl

Copyright: Jan D. ten Thije, 2022 Translated by Annick van der Bijl Design: Communication & Marketing, Faculteit of Humanities, Utrecht University

Portrait photo: Ralph Vermeulen