By Trang Vu

By Trang Vu

CONTENTS

Introduction

01. Historical Designer │Arne Jacobsen

Background and influences

Design Principles Philosophy

Key works

02. Contemporary Designer │Colvin & Moggridge

Background and influences

Design Principles

Key works

03. Similarities and Differences

04. Conclusion References

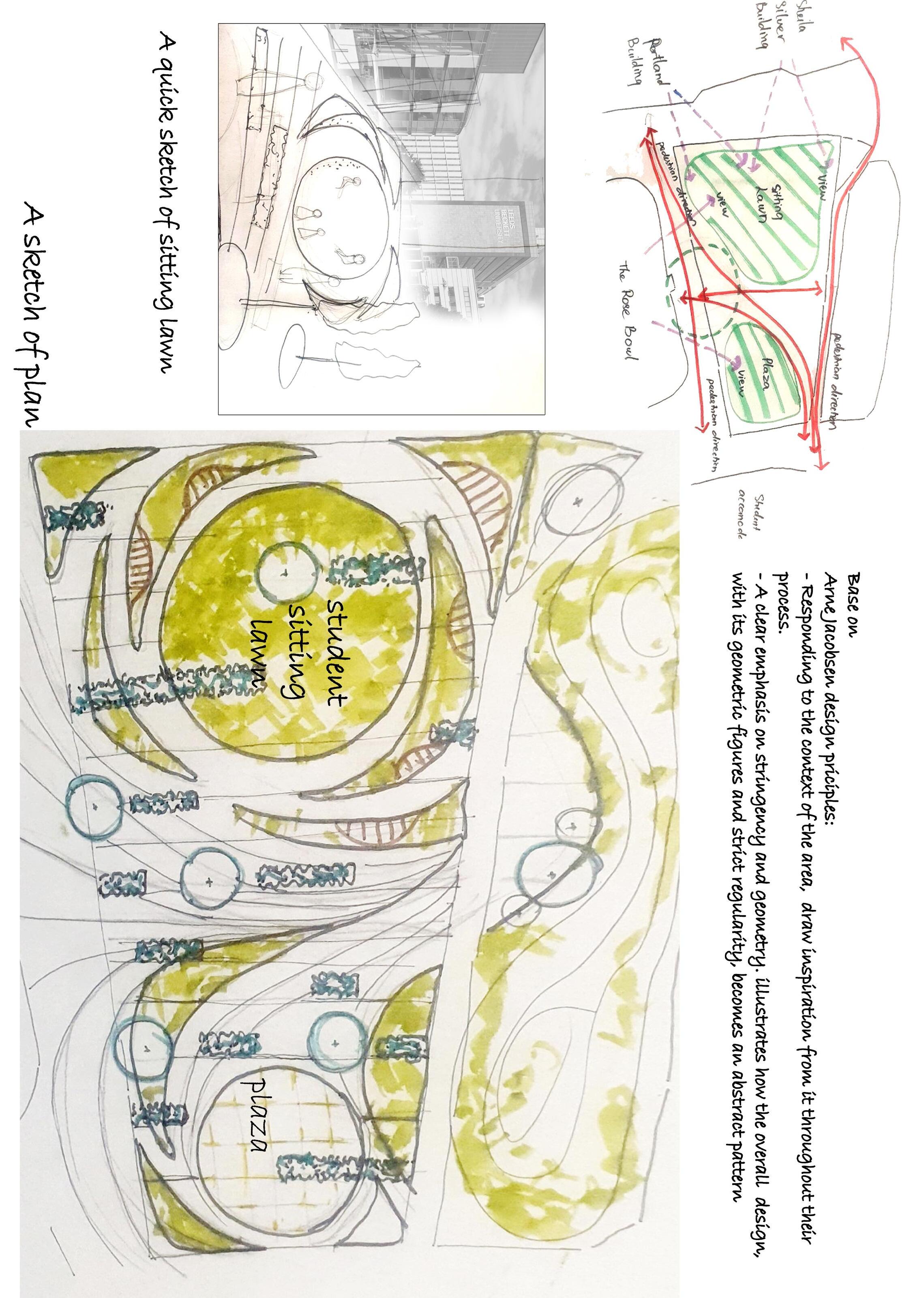

Sketches of Rose Bowl site

INTRODUCE

This report will aim to highlight key similarities and differences between an architect and a landscape practice from contrasting time periods. Firstly, exploring a historic designer, Arne Jacobsen and then later a contemporary firm, Colvin & Moggridge. By establishing information on each figure’s background, influences, description of key work, principles and design philosophy, the report seeks to provide means to enable a rich understanding of the impact which their interventions have had on the landscape, and on people who have experienced them. The report will then conclude by drawing similarities and differences between both the historic and contemporary designers and the lasting effects their interventions have had physically and perceptively.

Historical Landscape Designer Arne Jacobsen

1.1. Background

1.1.1 Danish architect Arne Jacobsen (19021971) is one of the most significant figures in Danish design history. A very young Arne Jacobsen started his training in the Copenhagen. Jacobsen was accepted at the Royal Danish Academy of Arts School of Architecture in 1924. This was a time of transition in architecture the war is over. New values and new ideals were being born. (Corral, 1991)

For six decades, Arne Jacobsen was at the forefront of Danish architecture and design. Working as both architect, furniture designer, industrial designer and landscape architect, he made contributions to the world of design that remain as significant today as they were in his lifetime. (arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

1.1.2. In this period, there were important events of 20th-century architecture that influenced him. Le Corbusier had published perhaps one of the most influential architectural books of the 20th Century, Vers une architecture - ‘Towards an Architecture’, in which he made a case for a new architecture for the evolving machine era. In the same year Walter Gropius had published Idee und Aufbau- ‘Ideas and Construction’, a proclamation of Bauhaus philosophy with regard to function, technique and aesthetics; ideas which Jacobsen would acknowledge in years to come as being profoundly influential in his approach. And yet, whilst Jacobsen’s tutors belonged to the first generation of Modernists, continuity of development and an evolutionary approach to teaching seems to have prevailed. Denmark’s architecture and building tradition, a tradition borne out of indigenous considerations, was a frame of reference Jacobsen was never to forget. (Arne Jacobsen 1902-1971,Astrid Bowron, Museum of Modern Art (Oxford, England), 2002)

1.2. A timeline of Arne Jacobsen’s career.

1.2.1. 1930s-1940s The Modernist

Early in his career he was involved in bringing modernism to Denmark and shaping a particular Danish functionalist expression that combined new architectural and design ideas with the Danish craft tradition and grasp of material qualities. Around 1930, this was manifested in works of architecture such as House of the Future (with Flemming Lassen, 1929), the housing development Bellavista (1934), Bellevue Theatre (1936) corporate facilities for Novo Terapeutisk Laboratorium (1937) and the paint shop Stelling House (1937). (arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

A few years later, in 1942, Arne Jacobsen completed two city halls (Aarhus City Hall and Rudersdal Town Hall). In both buildings the architects created a comprehensive total design of the interior dominated by soft shapes with wood, brass and leather as the main materials. The details from new tand old works of architecture and the abundance and diversity of nature were a rich source of fascination and inspiration to him. The inspiration from wild nature is most directly recognizable in the textile patterns he created during the 1940s, but many of his furniture designs too show the influence of nature in their free, organic shapes. (arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

1.2.2. 1950s A passion for botany

Arne Jacobsen had a lifelong passion for botany and his private garden functioned as both a refuge and a laboratory. Here, he spent countless hours tending to the plants and studying their appearance. His plant studies were an important source of inspiration.

Arne Jacobsen’s pronounced sensibility to the surrounding landscape was reflected in his works of architecture. For private clients he created detailed garden plans and several of his large, public projects also included artistic garden and landscape designs. Projects such as the Munkegaard School (1957) and St. Catherine’s College in Oxford clearly reflect Arne Jacobsen’s ambition of framing the rich diversity of nature in overarching lines, figures and patterns and creating a close interplay of architecture and nature. (arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

1.2.3. 1960s International breakthrough

After the Second World War, Arne Jacobsen made a name for himself both in Denmark and around the world, thanks in great part to projects such as the housing development Søholm (1951) and the Munkegaard School, with their yellow brickwork, oblique lines and innovative ground plans. With Rødovre Town Hall (1955) and SAS Royal Hotel, Arne Jacobsen represented a more internationally oriented architecture characterized by materials such as steel, glass and aluminium. Combining a new rational aesthetic with classic, living materials, his architecture maintained a humane feel despite its stringent expression. SAS Royal Hotel, 1960. In 1964, Arne Jacobsen completed his first major project abroad: St. Catherine’s College in Oxford. (arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

1.3.4. 1970s The final years-A great legacy

At the time of his death, Arne Jacobsen was working on a range of major projects, both in Denmark and abroad.

Arne Jacobsen put Denmark on the global map. His contributions to architecture, design and art were deeply influential during his own time, and their impact on subsequent generations remains at least as significant. (arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

The combination of function, craftsmanship and aesthetic quality that characterizes Arne Jacobsen’s work continues to influence our everyday life and is evident throughout society: in the urban space,a in the workplace and in our homes.

(arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

1.3. Design Principles-Philosophy as an Landscape Architect

1.3.1. Inspired by nature studies

The inspiration from his nature studies is most directly evident in the textile patterns Arne Jacobsen designed during his exile in Sweden in the 1940s, but his passion for nature was reflected in every aspect of his artistic practice – from his pronounced sensibility to the surrounding landscape reflected in his works of architecture to the organic expression in many of his designs.

At first glance, Arne Jacobsen’s interest in lush, untamed nature might seem to be in contrast to the generally stringent expression of his architecture. However, projects that included the grounds around the buildings clearly reflect his ambition of framing the rich diversity of nature in overarching lines, figures and patterns. (arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

At Strandvejen 413, where he lived and had his studio from 1951, he established a densely packed botanical garden with more than 300 different species of plants, many of them brought home as cuttings from trips abroad. He spent countless hours here, often taking photographs or working with a pen or a paintbrush, as he studied the colours, textures and shapes of the plants. These plant studies were an important source of inspiration to Arne Jacobsen. (arnejacobsen. com, 2022)

‘If I get a new life, I would like to be a gardener.’

1.3.2

. Integrating architecture and horticulture

Jacobsen in his garden, 1950s

World War II forced Jacobsen into exile, yet when he returned to Demark, he had developed a clearer sense of how architecture and horticulture might best be integrated. “As his buildings shifted towards asymmetrical compositions of unadorned planes, their interaction with their surroundings became increasingly direct. While Jacobsen continued to design gardens for his buildings, those gardens took the form of planted courtyards or stepped terraces.” (phaidon.com, 2016)

1.3.3. A total work of art - a combination of architecture and nature, from the whole to the detail.

St. Catherine’s College in Oxford is an example of Arne Jacobsen’s emphasis on achieving a close interplay of architecture and nature

St Catherine’s, beside the the River Cherwell in Oxford, is the only 20th century college within Oxford University to be granted Grade I listing by English Heritage.

Arne Jacobsen’s successful incorporation of the historical traditions of the Oxford Colleges – English university environments combining lecture halls and student rooms, some of them with buildings dating back to the 13th century – in an architectural solution based on contemporary ideals and a painstakingly executed comprehensive design programme makes St. Catherine’s

College one of Arne Jacobsen’s principal works. (Arne Jacobsen 1902-1971,Astrid Bowron, Museum of Modern Art (Oxford, England), 2002)

His design of the college garden needed to consider the architectural traditions of the historical university environment. The college consists of a series of individual, low buildings centred around a central courtyard, the Quad, where Arne Jacobsen designed a circular lawn with a Lebanese cedar. In a comment on the interplay of architecture and nature, Arne Jacobsen pointed out that the growth of the cedar provides ‘the strongest possible horizontal effect, which fully underscores and acts as an extension of the architectural design’. To the north and south, the Quad is bordered by free-standing walls and box-shaped yew hedges that underscore the unity of built structures and garden. (arnejacobsen. com, 2022)

The North Courtyard is another example of Jacobsen’s a total work of art

The largest and oldest of the courtyards, is known as Arne Jacobsen’s Garden, as he designed it, partly inspired by his own private garden. It is composed around semi-cylindrical concrete drums functioning as plant beds and four ornamental pools. It shows Arne Jacobsen’s interest in gardens, especially succulents and green plants. (nationalbanken.dk, 2015)

In this project Arne Jacobsen composed a garden plan with a clear emphasis on stringency and geometry. On a gravel base, Arne Jacobsen planned seven rows of semi-cylindrical plant drums with low plants interrupted by alternating gaps and circular ponds – a large pond at one end of the garden and three small ones at the opposite end. (arnejacobsen.com, 2022)

BRENDA COLVIN

The role of landscape architecture is to enhance the beauty and wellbeing of places.

(Moggridge, 2017)

HAL MOGGRIDGE

Contemporary Designer Colvin & Moggridge 02

2.1. Background

2.1.1 COLVIN&MOGGRIDGE is the longestestablished landscape architecture practice in the country since 1922; after Brenda Colvin met Hal Moggridge in West Oxfordshire in 1965. Their shared approach to the art and science of landscape architecture sparked an instant connection and the practice became Colvin & Moggridge. The firm based in London and the Cotswolds.

2.1.2 Benda Colvin

She founded the practice in 1922 and by 1939 . She was favoured for her brilliant plantsman ship, practical designs and sensitivity to the surrounding landscape. Always innovative, always with ecology and conservation in mind, she masterminded a great many original solutions. In 1929 she co-founded the Institute of Landscape Architects (now The Landscape Institute). She fought hard to raise the profile of the profession, including the engagement of landscape architects at the start of the planning process, not “as an ornament to architecture and engineering”. (colmog.co.uk, 2019)

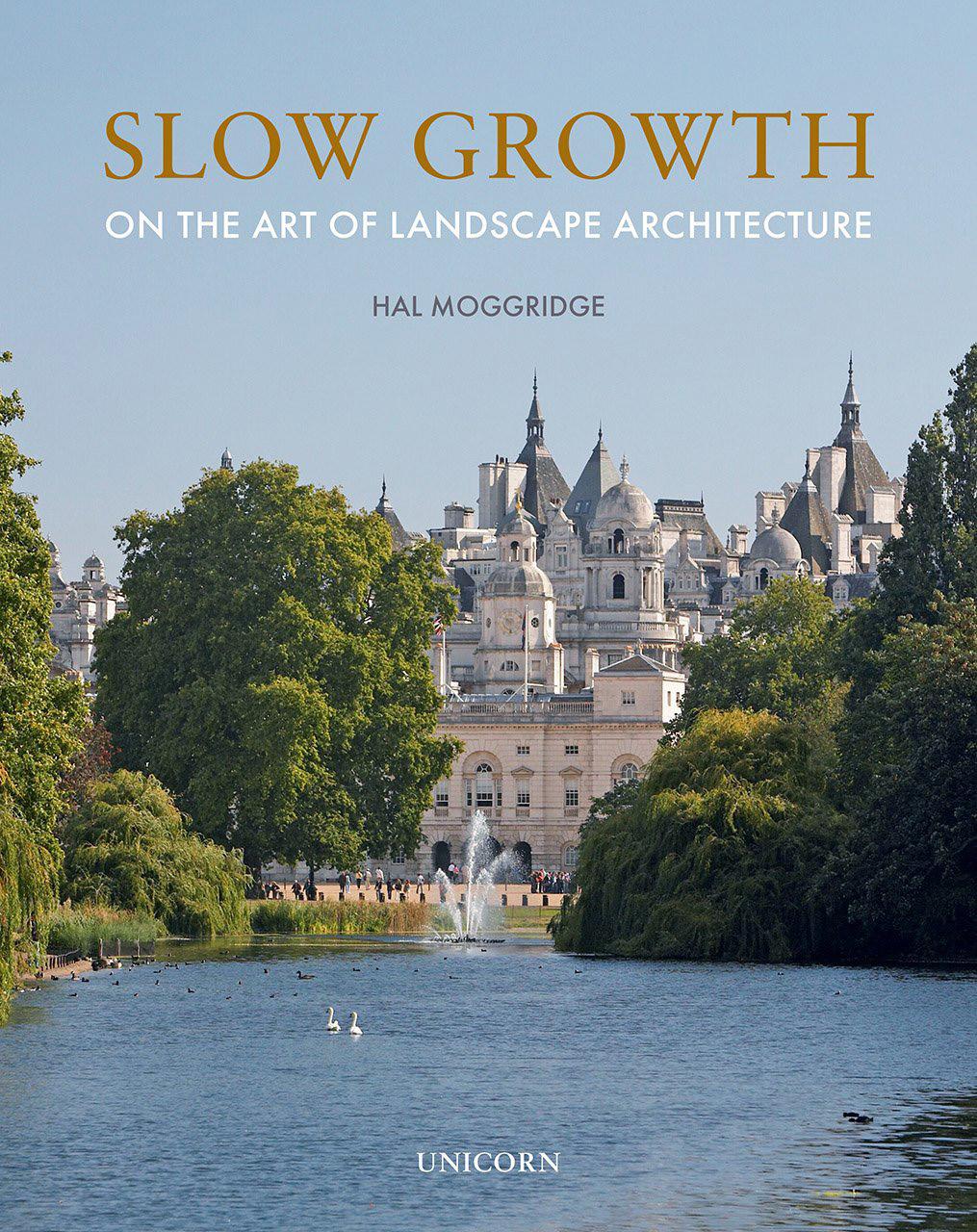

1.16 Hal Moggridge- the modern master of the natural landscape movement. Hal joined the late Brenda Colvin, a founding member of the Landscape Institute, at Colvin & Moggridge in 1969. He has written a book, Slow Growth: on the Art of Landscape Architecture. Through his work, Hal presents a modernised form of the naturalistic landscape design approach pioneered in England in the 18th century. He explores, through historic restoration projects, the 18th century naturalistic style, and the 20th-century evolution of this tradition through rural parks and lakes projects. He describes the idea of man-made projects moving from rural settings to cities as urban landscape and analyses urban views and skylines and how these might be preserved. (landscapeinstitute.org, 2017)

2.2. Design Philosophy

As a longest established landscape architecture practice in the country ‘UNIQUELY PERSONAL LANDSCAPES’

2.2.1. Ignoring landscape fashions, fads and formulas.

Theirs is a philosophy that produces landscapes where nothing seems forced, nor out of place, where every element effortlessly connects: be that the wider landscape, the past, or the people and communities using a place. They believe the art of landscape architecture lies in the ability to capture the genius loci, the spirit of the place, and visualise its capabilities. they analyse, evaluate and explain the place, its present and its past. We tie together architecture, setting and space. They know and feel what’s right for a place. They believe coherence, meaning and individuality all come from rigorous design discipline and it is these design principles that gift a landscape with lasting beauty.

2.2.2. Spaces

they improve the fabric and hierarchy of spaces as you move through the landscape. they create imaginative relationships between one space and another: through scale, openness and enclosure, not mere functional fit.

2.2.3. Sightlines and Views

They give frameworks, axes and sightlines meaning and ornament; we define and create views – in, out, across and to borrowed prospects beyond. A landscape without views is a design without life.

2.2.4 Structures

They design built structure to be artful and durable, using fine natural and modern materials.

2.2.5. Contrast and Context

To create flow, mood, balance, and appropriate complexity, they use contrasts: light and shade, rough and smooth, formal and informal; and they use the context of the landscape – its sounds and scents, its feel and history, its levels and landforms, and water, existing or introduced. We add dimensions.

2.2.6. Planting

No landscape is complete without an imaginative design for planting, of trees, shrubs and flowers in rich mix and with careful juxtaposition to create seasonal variety and ecological diversity. Plantsmanship is fundamental to the creation of lasting beauty and pleasure.

(colmog.co.uk, 2019)

2.3. Key words

2.1.1

Challenges:

To better deal with the increasing number of planning applications for very tall buildings in central London that would change the landscape character of the Inner Royal Parks.

The Outcome

Rather than object to each proposal individually, they carried out extensive fieldwork to establish the areas where views out were a material factor in determining the character of that landscape. they identified areas of high sensitivity to intrusion by distant tall buildings - typically these were areas where a rural character provided a contrast to the surrounding metropolis, or where a landscape and its views had been specifically designed - then mapped the skyspace needed to safeguard these areas from building intrusion.

The really bold move was to restore the view from St James’s Park by cutting down two mature trees that were in the way. It is pleasing to see gardens which, designed deliberately to avoid fashion fads, were little regarded on their completion but now seem virtually timeless. (colmog.co.uk, 2019)

The Rose Garden is located in the southeast corner of Hyde Park, south of Serpentine Road near Hyde Park Corner. The design was developed from the concept of horns sounding one’s arrival into Hyde Park from Hyde Park Corner. The central circular area enclosed by the yew hedge is imagined to be the mouth of a trumpet or horn and the seasonal flower beds are the flaring notes coming out of the horn. (colmog.co.uk, 2019)

The Rose Garden is located in the south east corner of Hyde Park, south of Serpentine Road near Hyde Park Corner. The design was developed from the concept of horns sounding one’s arrival into Hyde Park from Hyde Park Corner. The central circular area enclosed by the yew hedge is imagined to be the mouth of a trumpet or horn and the seasonal flower beds are the flaring notes coming out of the horn.

The rose planting is mixed with herbaceous planting, creating rich seasonal flower beds and strong scents. The spectacular seasonal bedding is a hugely popular feature; the gardens attract high numbers of tourists particularly in the summer months and are still popular throughout the year with local residents and office workers as a quiet contemplative place. (colmog.co.uk, 2019)

2.1.3 Redesign South Steps approach Royal Albert Hall, London

The music-inspired concept design won the national competition. In a nod to both the Royal Albert Hall as a concert venue and the Royal College of Music, which faces onto the steps from the south, the parterre at the top of the steps now includes topiary clipped to represent musical notations and instruments. The steps are enclosed by trees, rich foliage, flowers and scent – a deliberate horticultural celebration with an emphasis on late summer interest to coincide with the Proms Season. The strong structure of clipped hedges and trees sets off this horticultural display and works to provide year long interest in this urban site. (colmog.co.uk, 2019)