1

CONTENTS 02 SITE CONTEXT & ANALYSIS 7 Site Location 8 Wider Character Areas 13 Site Character Areas 15 Photographic survey Topography 16 History of Bradford Waterworks 19 Bradford Beck catchment area 23 Pollution of Bradford Beck 25 Flood risk assessment 26 Green infrastructure 27 Bradford Canal Road Greenway 28 Access & Movement analysis 29 Public Rights Of Way 29 SWOT 30 03 RELEVANT RESEARCH DOCUMENTS 34 Research documents 33 Policy & Planning 35 04 CASE STUDIES AND RESEARCHES 38 Cheonggyecheon Stream Restoration Project- Korean 39 River Porter De-Culverting, Sheffield 40 Mayfield Park, Manchester 41 The Kallang River Bishan Park, 42 Singapore Pedestrian area for garden city 43 Slovenia 2 05 DESIGN CONCEPT 51 Vision 52 Aims and Objectives 53 Key moves 54 Concept 60 Zoning 61 Sketches 62 Figures and references Roombeek the Brook, Netherlands Soil Bioengineering for Slope Stabilization Naturalized Landscape Design Water For People – Cities Alive Sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) Application 44 45 47 49 50 Foreword 01 INTRODUCTION 4 Understanding Bradford 6

Foreword

The selected site for study within this document is located on a linear stretch of land to the north of Bradford town centre.

This document aims to uncover the local social, economic and environmental context of the site in order to establish a strategy for potential development. Suitable solutions for the site in question will be investigated within the theme of town waterside and public spaces restoration

3

4

01 INTRODUCTION

5 Fig.1

Salts Mill is a former textile mill, now an art gallery, shopping centre, and restaurant complex in Saltaire, Bradford

Understanding Bradford

One compelling theme throughout my research was that Bradford is ‘hidden’. This bred a desire to uncover the Bradford ‘experience’, starting with its position in the region; Bradford is strategically located between Leeds and Manchester.

I then looked at its’ wonderful topography and buried water courses; it is a 'hidden' asset of this city

At the network of city centres – high streets, village greens, parades and corner shops. I examined its special featureslisted buildings, historic landmarks, and panoramic views.

Above all, I discovered the diversity and strengths of its people. Bradford is the sixth largest city authority in the UK with a population of 534,000 people And the district’s population is growing Bradford is a youthful place with more than a quarter of the population under 18, making us the youngest city in the UK. Bradford has a diverse population with ethnic minorities making up 36% of the total population.

I turned our attention to the City’s dreams and aspirations, as outlined in the District’s 2020 Vision consultation The objective was clear: To create a city centre “where people are justifiably proud of where they live, learn, work and play”

To be a part of this objective, a setting designed to change the landscape – both socially and environmentally I offer a creative but deliverable solution that differentiates Bradford from ‘the rest’ and reveals it as a unique and inviting northern City.

6 Fig.2

SITE

7

02

CONTEXT &ANALYSIS

8

Town Hall, Bradford

Fig.3

Bradford Location

Bradford is a city in West Yorkshire, England, in the foothills of the Pennines, 8.6 miles (14 km) west of Leeds, and 16 miles (26 km) north-west of Wakefield

WEST YORKHIRE

ENGLAND

1 Bradford 2 Leeds 3 Wakefield 4 Kirklees 5 Calderdale

1 2 3 4 5

9

BRADFORD LOCATION

Bradford City Centre is at the heart of a great European city with an immediate population of around 350,000 people. Once the world Centre forthe worsted trade it is now reclaiming its position as one of the UK’s leading provincial cities

THE STUDY AREA

THE STUDY AREA

10

SITE LOCATION

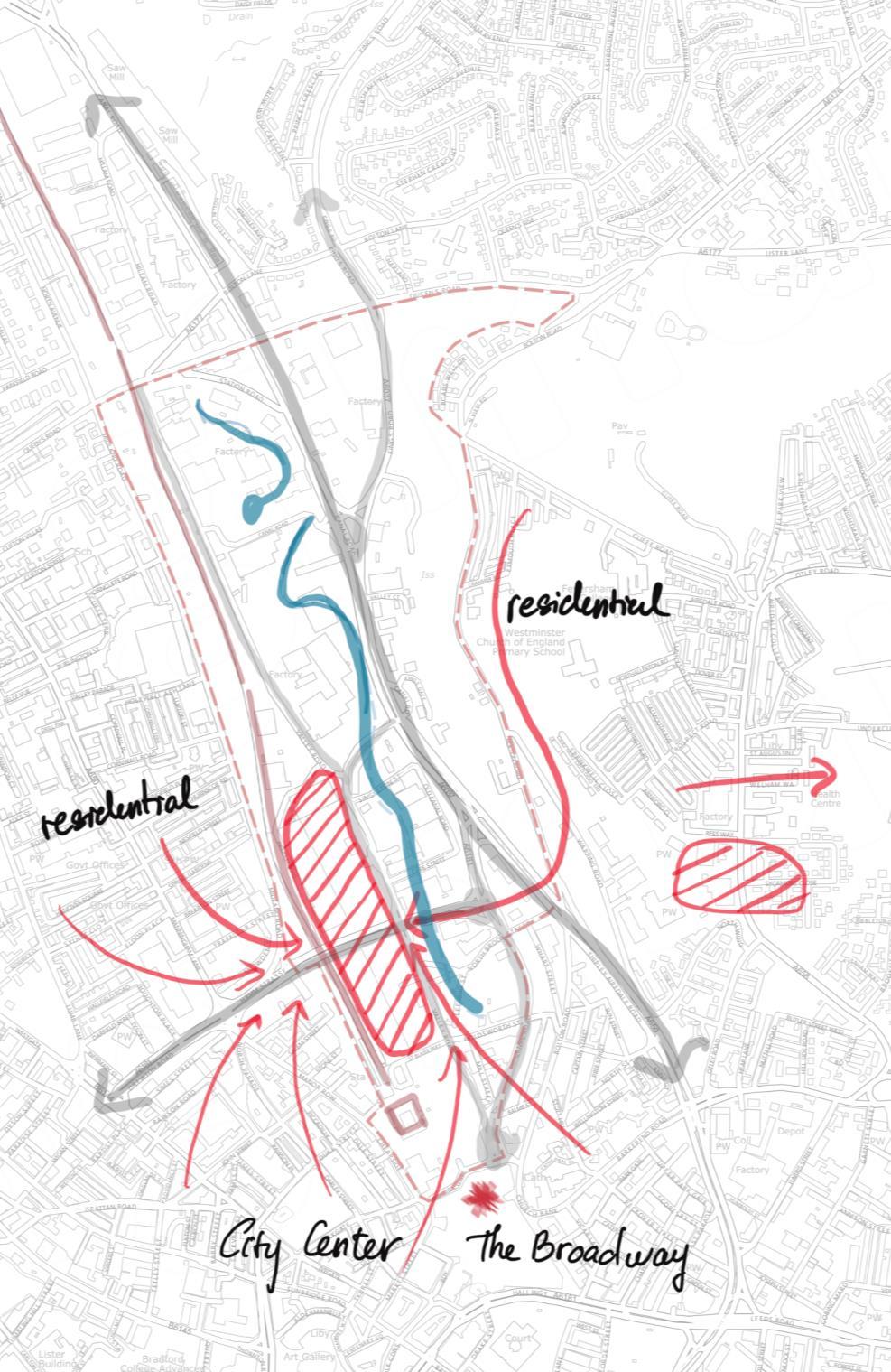

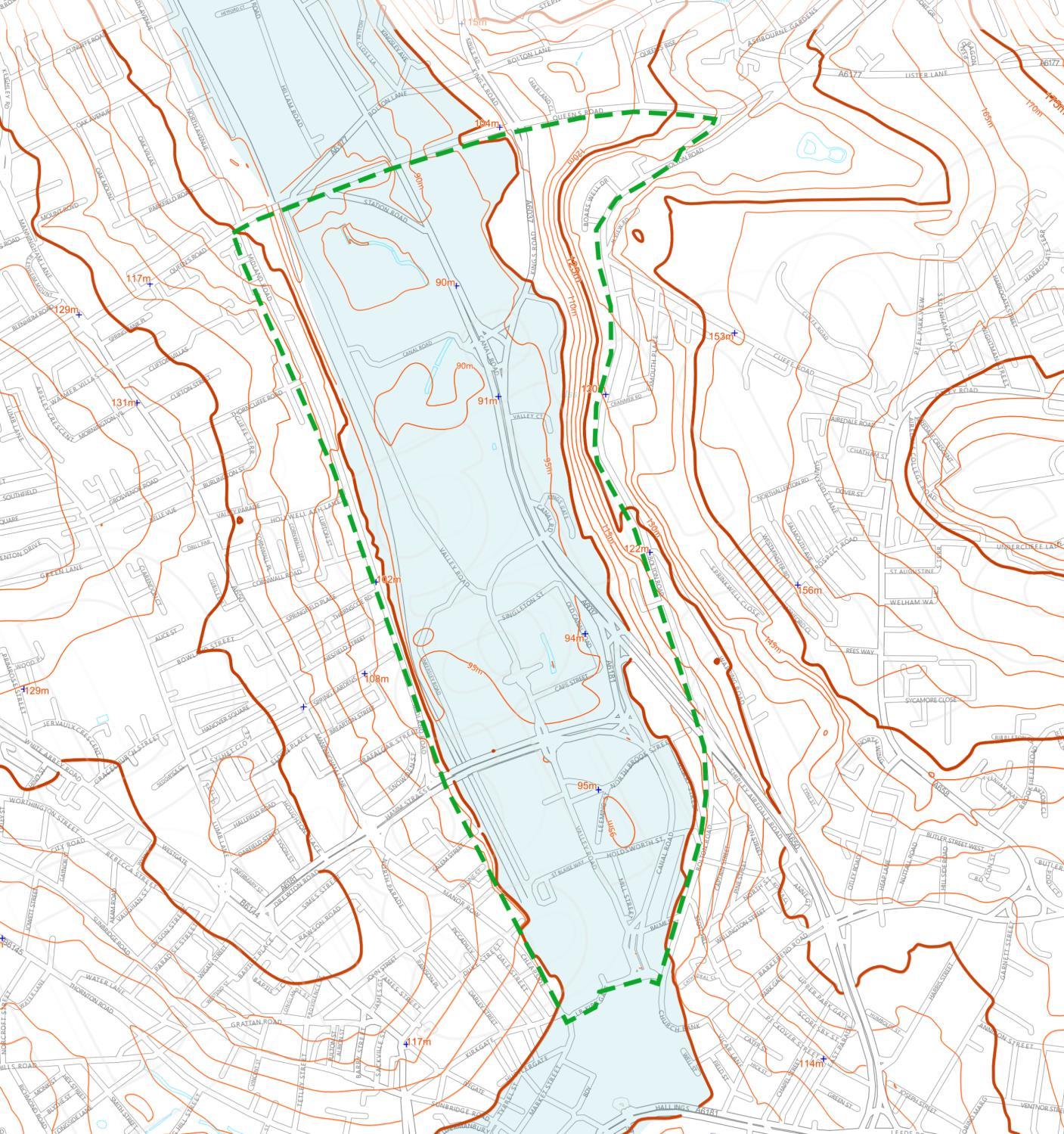

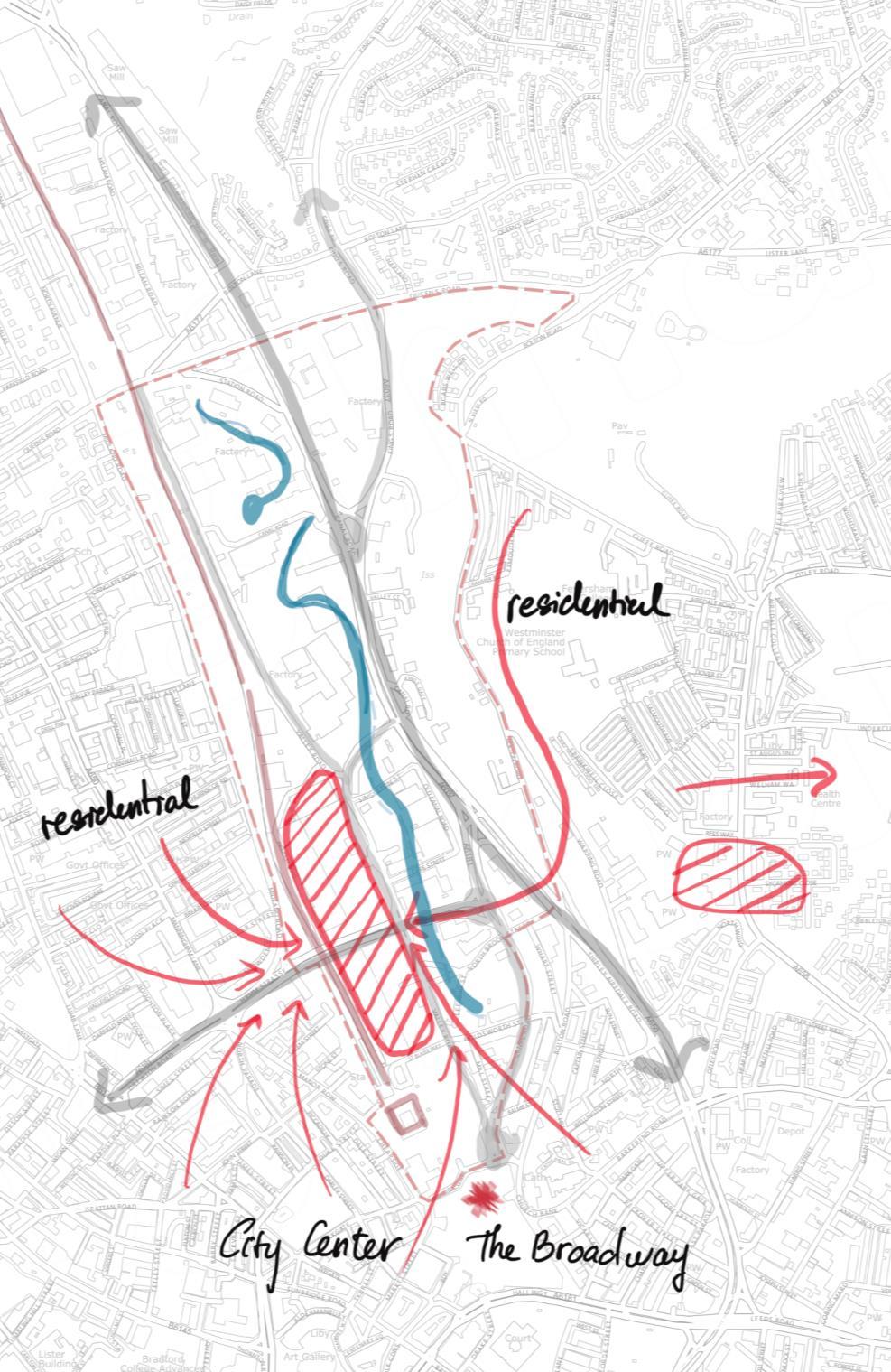

The study area is located on the edge of the city centre and Bradford Foster square Train station. The current use of the site is industry and warehouses. Hidden gems of historical influences form underground waterways and Local Mills. The sites used to have a canal which was later on removed. Bradford beck water flow leads to River Aire. Existing green corridor from the Shipley to the fringe of Bradford.

CANAL ROAD

Canal road, Bradford Canal road, Shipley

Canal road forms the eastern site boundary

CANAL ROAD

Canal road, Bradford Canal road, Shipley

Canal road forms the eastern site boundary

SITE

11

SITE LOCATION

The site is located in the North of Bradford City Centre. It is a part of the valley Canal Road Corridor connecting Bradford to Shipley and settlements to the north and beyond. Transport connections have historically been located on the valley floor with Canal Road, the train line and former Bradford canal, now filled in a lost, all running along the base of the valley. The overall topography is an assett to the site sitting within the valley floor provides level access ideal for cycling with good connections to others green spaces and the new Cycle Superhighway to Leeds and beyond.

The site is the gateway to the Bradford town centre from Shipley green way corridor

12 Fig.4

Wider Character Areas

3

4

1

5

8

2

9

6

7

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

BRADFORD CATHEDRAL RESIDENTIAL

THE BROADWAY

WHITE ABBEY RESIDENTIAL LISTER PARK

CENTENARY SQUARE city park mirror and fountain

FOSTER SQUARE STATION

BRADFORD CENTRAL MOSQUE

BRADFORD INTERCHANGE

13

RETAIL PARK AND WAREHOUSE

Bradford contains a range of different characters throughout and around the town.

The character of the town centre itself is dictated by its history and culture, with bricked streets home iconic architectural features such as Bradford Cathedral and the Centenary Square area. Outside of the centre are a number of areas with various uses including, residential, industrial, recreation and commercial.

The selected site for study within this document lies north of the historic town centre, surrounded by a number of areas with an abundance of uses.

The research site has many location advantages as it is located near Bradford town center and transportation hubs such as Foster Square and Bradford Intercharge. Surrounded by the historic residential- Bradford Cathedral, White Abbey residential as well as the gradually forming Peel Park residential to the east. The area is also linked to Bradford's busy shopping centre, the Broadway and Bradford Cathedral as landmark of the site

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

BRADFORD CATHEDRAL

THE BROADWAY

WHITE ABBEY RESIDENTIAL

FOSTER SQUARE STATION

RETAIL PARK AND WAREHOUSE DISTRICT

BRADFORD CENTRAL MOSQUE BRADFORD INTERCHANGE

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

BRADFORD CATHEDRAL

THE BROADWAY

WHITE ABBEY RESIDENTIAL

FOSTER SQUARE STATION

RETAIL PARK AND WAREHOUSE DISTRICT

BRADFORD CENTRAL MOSQUE BRADFORD INTERCHANGE

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

14

Fig.6

Fig.5

Fig.7

Fig.8

Fig.9

Fig.10

Fig.11

Fig.12

Fig.13

SITE CHARACTER AREAS

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 5 3 6 7

15

Boar well natural reserve

1 2 1 1 2 3 3 4 4 5 5

View from valley road to Bradford Cathedral

View from Valley road Foster Square derelict land Valley Road and Canal Road intersection

View from valley road to the eastern hill dwellings

16

PHOTOGRAPHIC SURVEY

PHOTOGRAPHIC SURVEY

6 7 10 6 9 7 8 9 10

Canal Road 8

Tricky Crosing between Retail parks

The site dominant by Car parks

The site dominant by Car parks

17

Inificent Cycle path

11 12 13 14 11 11 12 13 14

uphill woodland in Canal Road

Business park and uphill woodland

Derelcit Land and buiding

18

PHOTOGRAPHIC SURVEY

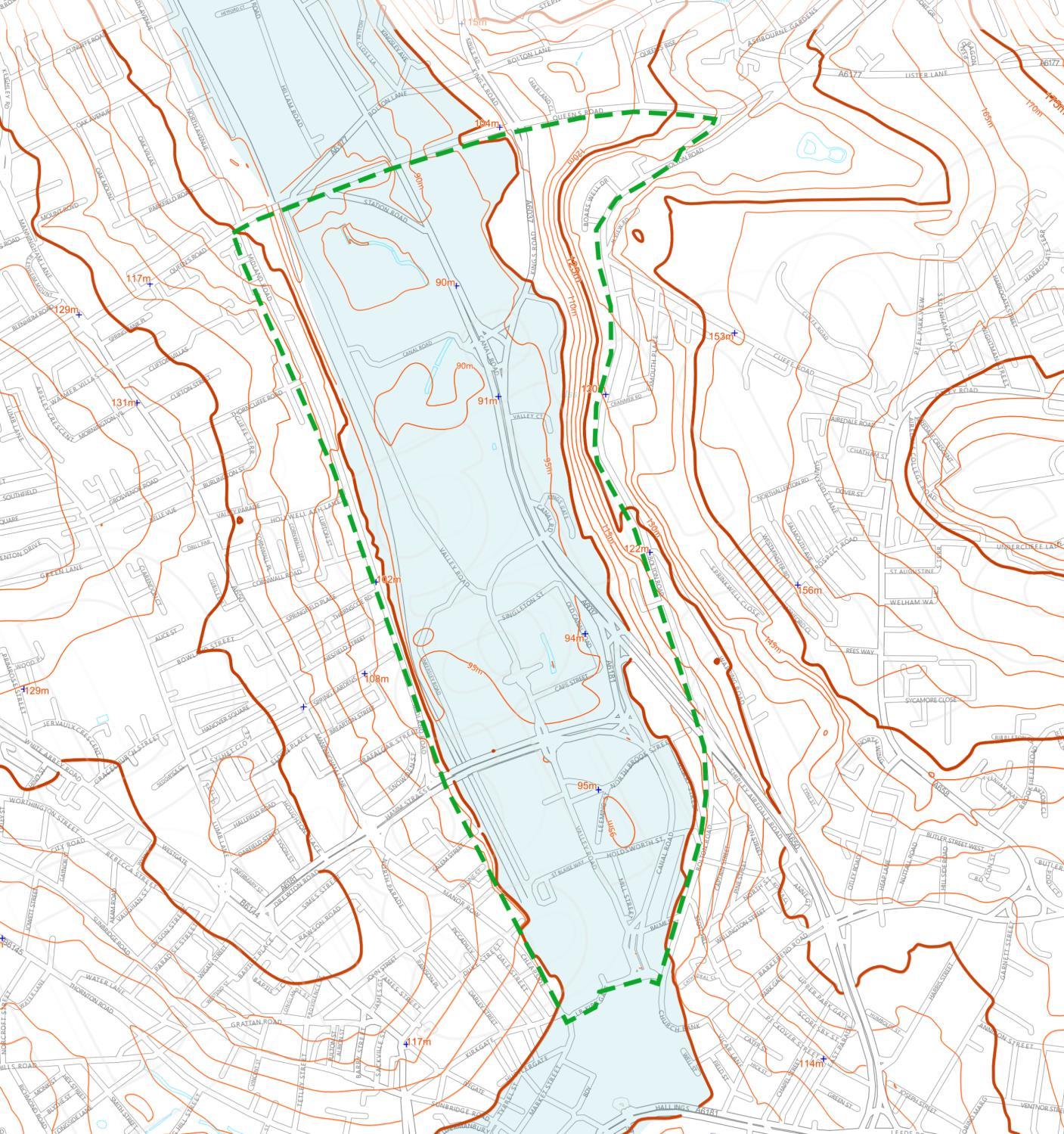

TOPOGRAPHY

The site in the valley runs along the Bradford- Shipley corridor. The topography inside of the area is quite flat, the majority of the site sits around 90 to 95 meters.

The site is flanked on each side by sloping terrain and is the reason

the Bradford beck runs along the Bradford- Shipley corridor as the site sits within the valley floor which slopes steadily from the south to the north.

The valley terrain and The sloping terrain on either side of the area give the area an interesting character, which is both a strength in terms of the viewpoint and a weakness in terms of connection

Topography Section

A

Map The site

Topography

A

+ + + + Low areas 19

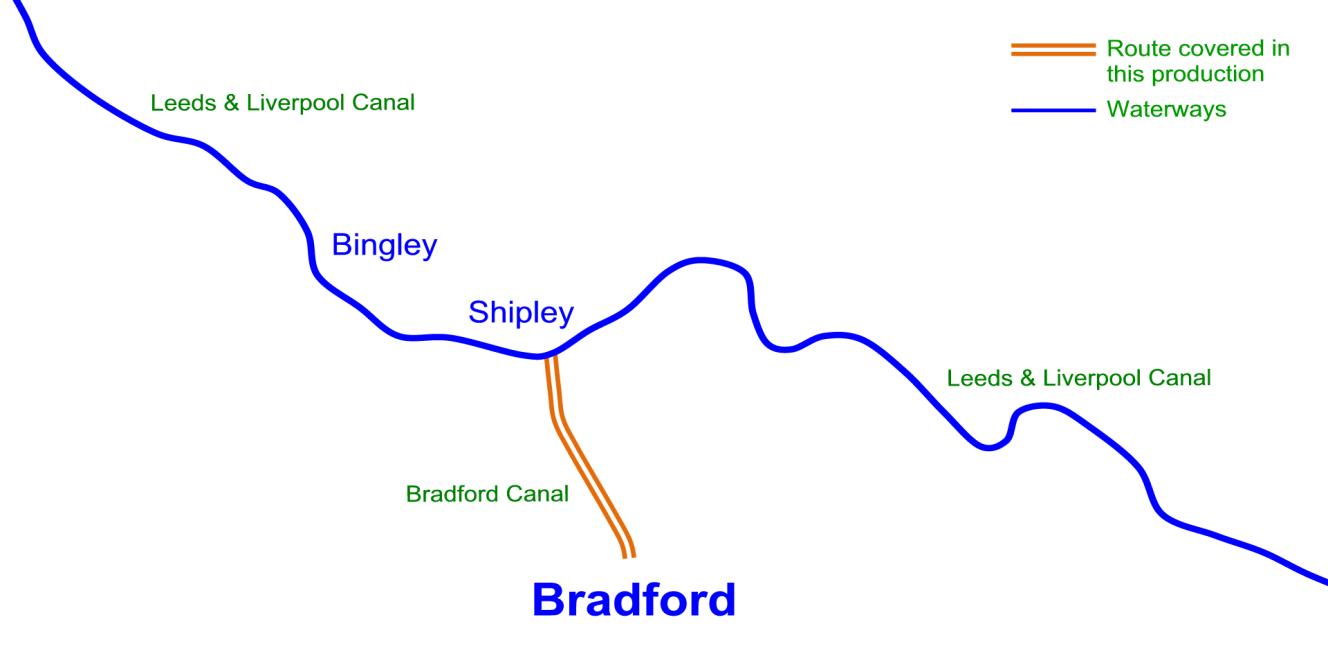

HISTORY OF BRADFORD WATERWORKS

The Bradford beck begins from small watercourses at Clayton and Thornton with a relatively small catchment area and extends all the way through Bradford and is culverted at many sections including Bradford city centre. There are many tributaries which feed into the beck many of which are through industrial areas. Bradfrord beck flows from Bradford City centre to Shipley where it meets the river Aire and is the reason why Bradford is called Bradford. The feasibility study, design and access statement and design document reveal the important layers that bond the site and make it unique in its own context.

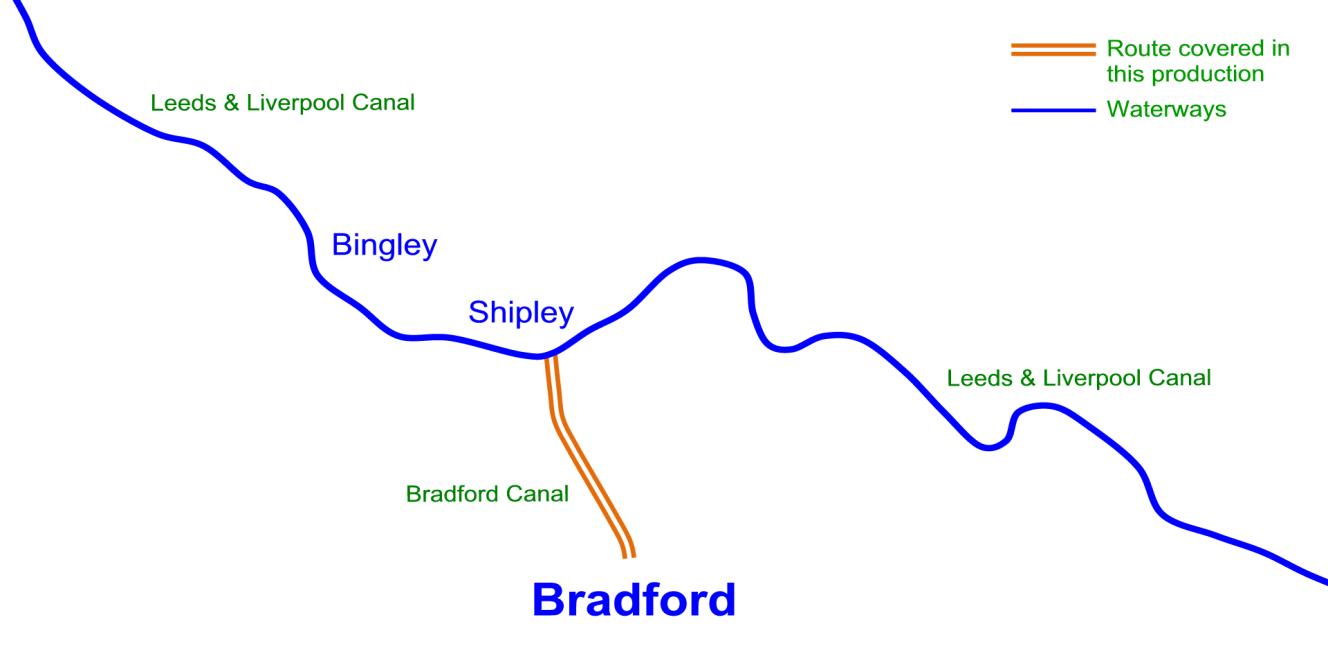

The Bradford Canal was a 3.5-mile (5.6 km) English canal which ran from the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at Shipley into the centre of Bradford. It opened in 1774, and was closed in 1866, when it was declared to be a public health hazard. Four years later it reopened with a better water supply, and closed for the second time in 1922. It was subsequently filled in, although consideration has been given to restoring it. There are some remains, including a short section of canal at the junction and a pumping station building, which is now a dwelling.

The Site

Bradford Beck

Map of Bradford c1820 Showing route of Bradford Beck

Map of Bradford c1820 Showing route of Bradford Canal

The Site

Bradford Canal

The Site

Bradford Beck

Map of Bradford c1820 Showing route of Bradford Beck

Map of Bradford c1820 Showing route of Bradford Canal

The Site

Bradford Canal

20

HISTORY OF BRADFORD AND THE FLOW OF BRADFORD BECK

Medieval times

Bradford Beck begins as a number of springs around Keelham. Bradford Beck follows a miserable course under Bradford, constrained in brick lined culverts and straight channels until it meets the River Aire in Shipley. Once a clear, open river, Bradford Beck was at the centre of Bradford life for centuries and is where the city derives its 1000+ year old name, the broad ‘ford’ or crossing over the Beck. The river system was used to power a series of corn mills and fulling mills and the demand more more water power and technological advances in milling were the driving forces behind early rerouting of the beck.

Industrial Revolution: 19th Century

During the industrial revolution Bradford grew to be the centre of the world’s wool industry. By 1840, as a fetid repository for raw sewage and industrial effluent, the beck was used as a sewer to carry away Bradford’s industrial and domestic waste. Offal, raw sewage and industrial effluent from mills and work-shops filled the beck. People still used the beck for drinking water and outbreaks of typhoid and cholera were common. However, Bradford was booming and land values were soaring so in a time of few building controls Bradford Beck was, bit by bit, culverted and built over. By 1870, it had all but disappeared from view. It has become a hidden river as it flows beneath Bradford’s streets

20th Century

Bradford began the 20th century as one of Europe’s wealthiest cities with its own stock exchange and banks dedicated to handling international trade in fibres. The boom years eventually had to end and as the city’s prominence declined from the 1960’s onwards, the industrial legacy of water pollution was an added blight to the lives of Bradford’s people.The 20th century saw major improvements in water quality but little improvement to the physical character of the river. Under the Water Framework Directive, the Beck is now classified as “poor ecological quality.

Map of Bradford c1800 Showing route of Bradford Beck 21

Fig.14

Fig.15 Fig.16

HISTORY OF BRADFORD CANAL

The Bradford Canal was a 3.5-mile canal which ran from the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at Shipley into the centre of Bradford. It opened in 1774, and was closed in 1866, when it was declared to be a public health hazard. Four years later it reopened with a better water supply, and closed for the second time in 1922. It was subsequently filled in, although consideration has been given to restoring it. There are some remains, including a short section of canal at the junction and a pumping station building, which is now a dwelling. The canal is steeped in history of a once thriving city at the height of the boom of textile manufacture.

In the early years of the 21st century, there is a plan to rebuild the Bradford Canal. Among the many projects conceived in connection with Bradford’s bid to be European Capital of Culture for 2008 (which competition was actually won by Liverpool), one was a scheme to recreate Bradford Canal. In 2004 Bradford Council, British Waterways, and Bradford Centre Regeneration jointly established a committee to investigate the possibilities of a new canal. According to “Canal Road News”, a full feasibility study has “concluded that reinstating Bradford Canal is feasible, represents value for money, and opens considerable development opportunities along the five-kilometre canal corridor”.

The Bradford Canal once ran from the Leeds & Liverpool Canal at Shipley to Bradford. It opened in 1774 and closed in 1922. There are proposals to re-open it.

22 Fig.17

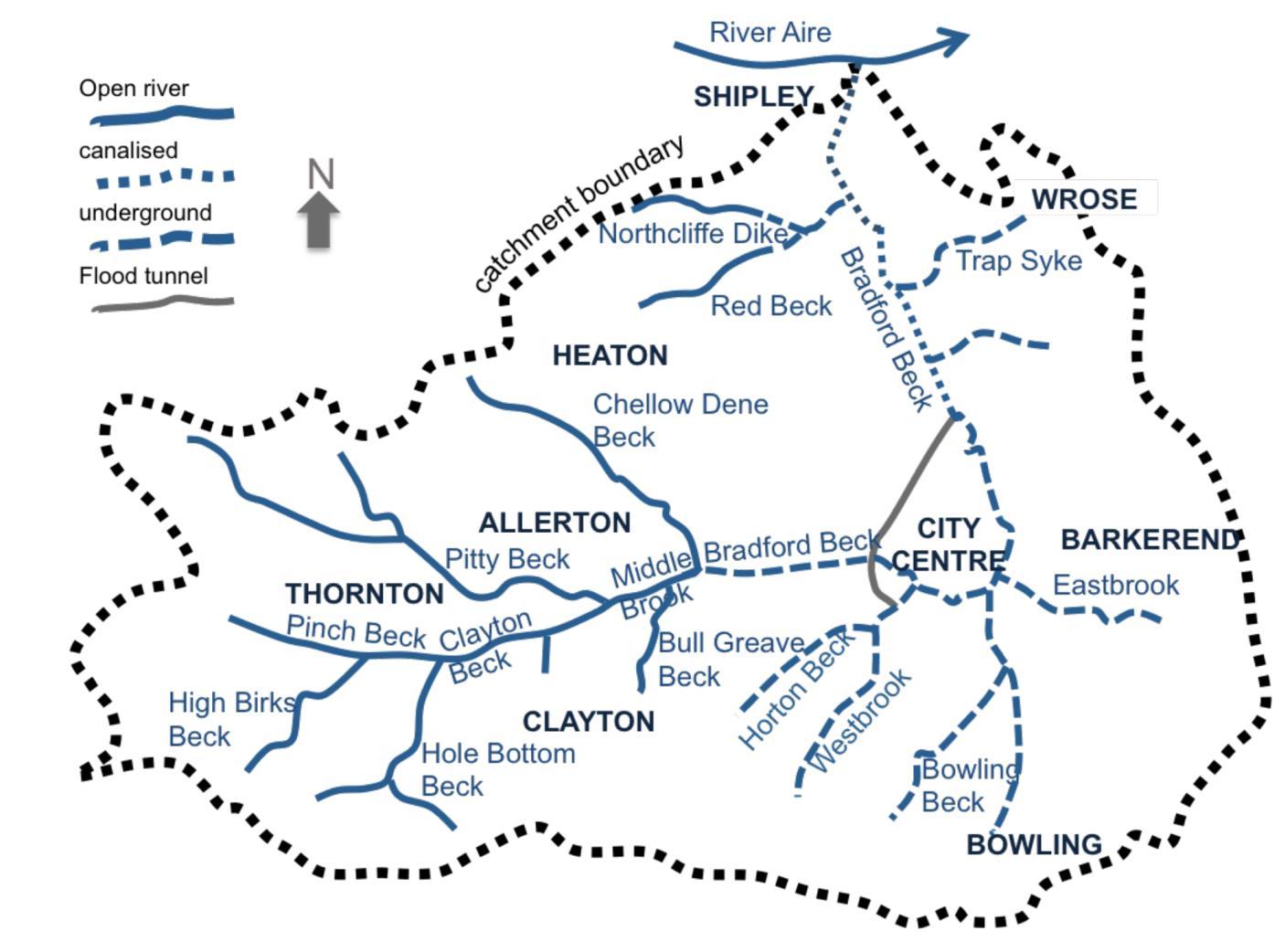

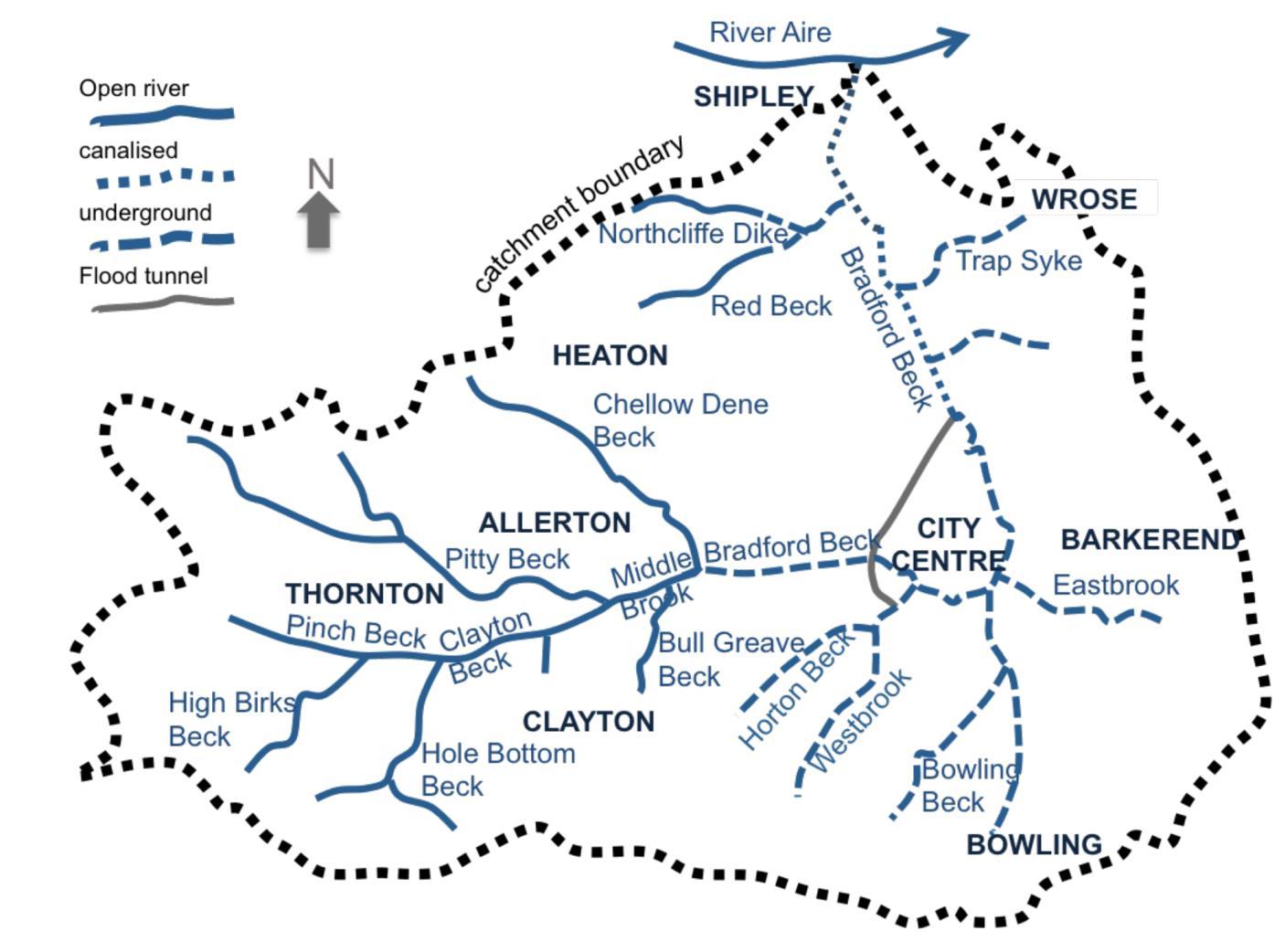

The Bradford Beck catchment of about 60 km2 in area and illustrated in the image opposite.

The Beck rises in the west and relatively rural area of the catchment (Pitty and Pinch Becks). Through much of the urban area, it flows in culvert, with very few stretches open to the atmosphere.

All the tributaries in the urban area are also culverted(Westbrook, Bowling Beck and Eastbrook), with most of them running through industrial areas. After the Beck emerges from the culvert, it is canalised all the way down to its confluence with the River Aire in Shipley; some stretches are also culverted.

In the early 1990s, a flood diversion tunnel was constructed. This can take water from Westbrook and the Bradford Beck upstream of the city centre and re-join the Beck downstream, reducing the risk of flooding in the city centre. In dry weather there should be no flow in the diversion but this was not the case during the period of this study 2012 when significant flows went through the tunnel.

Most of Bradford is on a combined sewer system (i.e. foul and storm water in the same pipes). There are 51 CSOs (combined sewer overflows) in the catchment, through which excess flows are discharged to surface water during wet weather.

In the early 2000s, 10 storm tanks were installed to store and reduce the frequency and size of such spills, but spills have not been eliminated. In addition, there are an unknown number of outfalls for surface water; these are unregulated and may have foul water drains misconnected to them.

Much of the land alongside the becks has been filled in order to raise levels and create flat areas of land for construction, often of industrial sites. Other land has been used as landfill. There is a high likelihood that much of these infilled areas will be contaminated land and at risk of leaching pollution into the streams.

BRADFORD BECK CATCHMENT AREA

23

Bradford canal valley

Fig.18

BRADFORD BECK CATCHMENT AREA

EXSISTING

Examples of culverts in Bradford

Bradford had a period of industrial prosperity associated with water ways that are now buried and hidden. This report presents a feasibility study on restoration and bringing water back to the city, recreational use and ecological enhancement.

The route of underground Bradford Beck on aerial map

Map of Bradford c1820 Showing route of Bradford Beck

Ariel map showing water course catchment 24

POLLUTION OF BRADFORD BECK

The Bradford Beck water-body was classified as of poor ecological quality in 2009. In order to update this information understand the nature and sources of pollution in the Bradford Beck and its tributaries, multiple rounds of water samples were taken by volunteers from multiple locations during 2012. The results show that the water-body is still of poor ecological quality due to high concentrations of BOD and ammonia. Concentrations of chromium are also of concern. The pollution arises from illegitimate connections of sewers into surface water drainage and into the streams. These occur in all areas but are particularly concentrated in the urban areas with culverted tributaries (Westbrook, Bowling Beck and Eastbrook). They discharge both domestic and industrial effluents. The water-body is prone to pollution incidents. As well as the many CSOs which discharge in wet weather, pollution incidents occur due to occasional industrial discharges and spills due to sewer blockages.

Pollution by acid mine drainage

Grey water produces milky colour and bad smell

Turbid odorous discharge from a food processing factory entering Bradford Beck.

25

Tipping into the beck

Fig.20

Fig.21

Fig.22

Fig.23

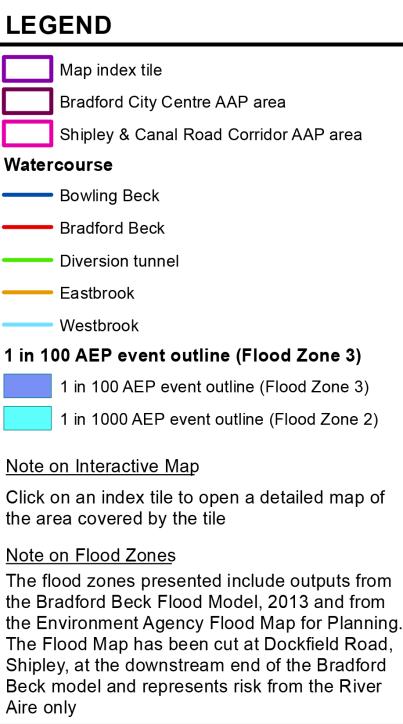

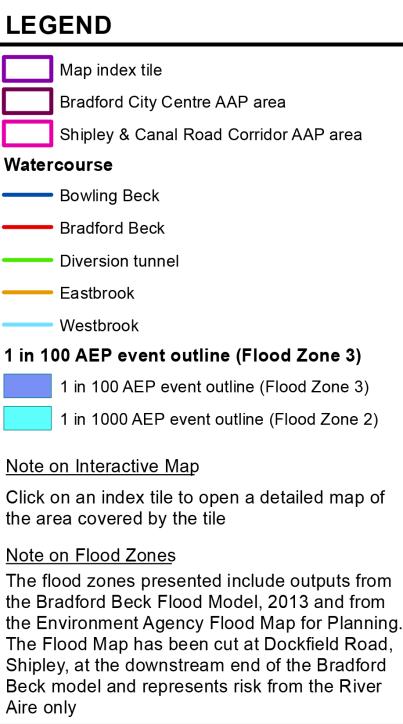

FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT

Flood Risk From Surface Water

The risk of flooding identified from surface water will certainly be a contributing factor towards any potential flooding in the area. Due to the topography of the Corridor. Also, The site is generally flat and hardstanding in character, resulting in poor drainage solutions.

Retaining and filtering excess surface water must be a priority, in order to again alleviate pressures of the site.

By incorporating effective and suitable forms of Sustainable Urban Drainage systems (SUDs) into the development, the site may become much more resilient within the context of climate change.

FLOOD ZONE 3 FLOOD ZONE 2

BURRIED WATERWAY 26

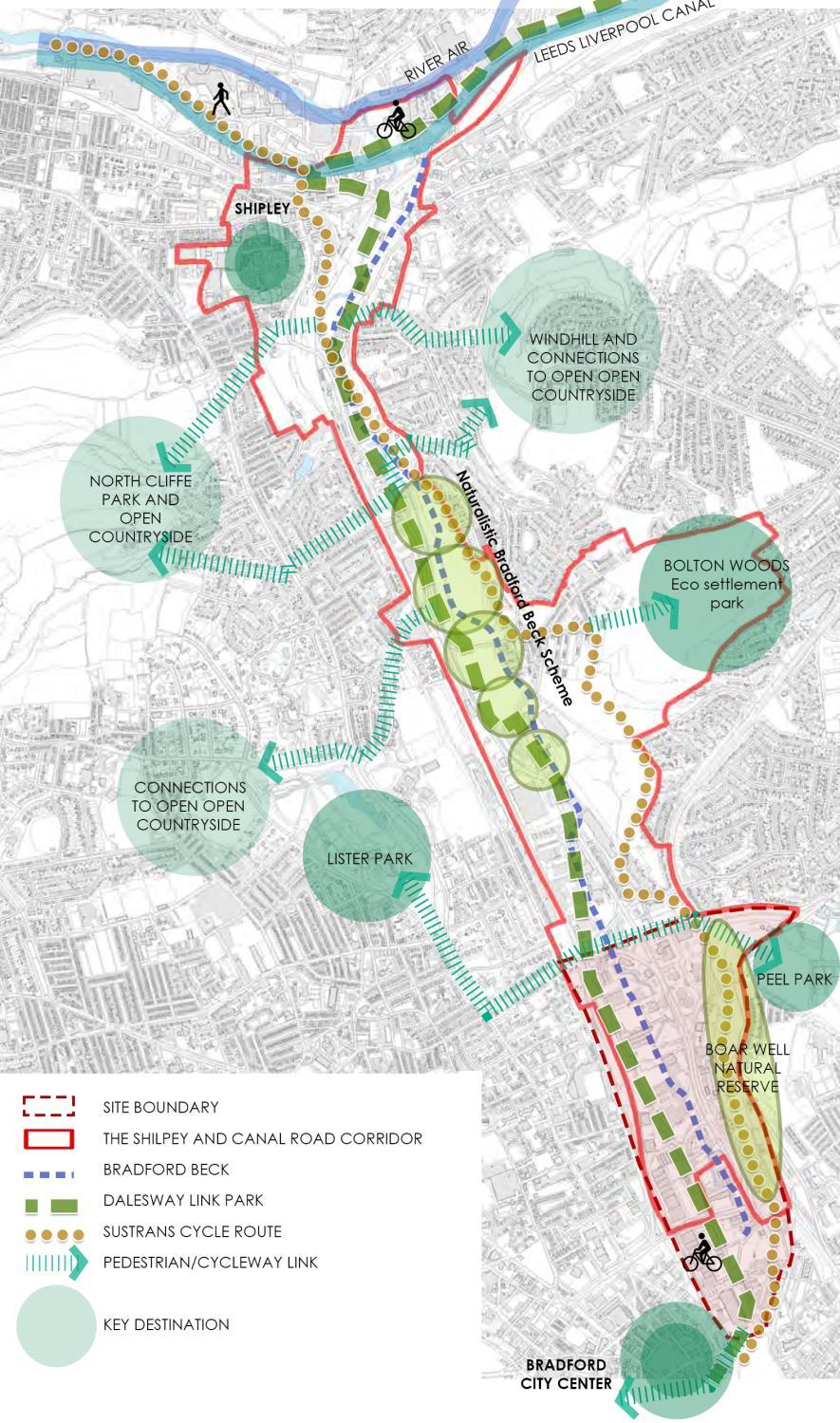

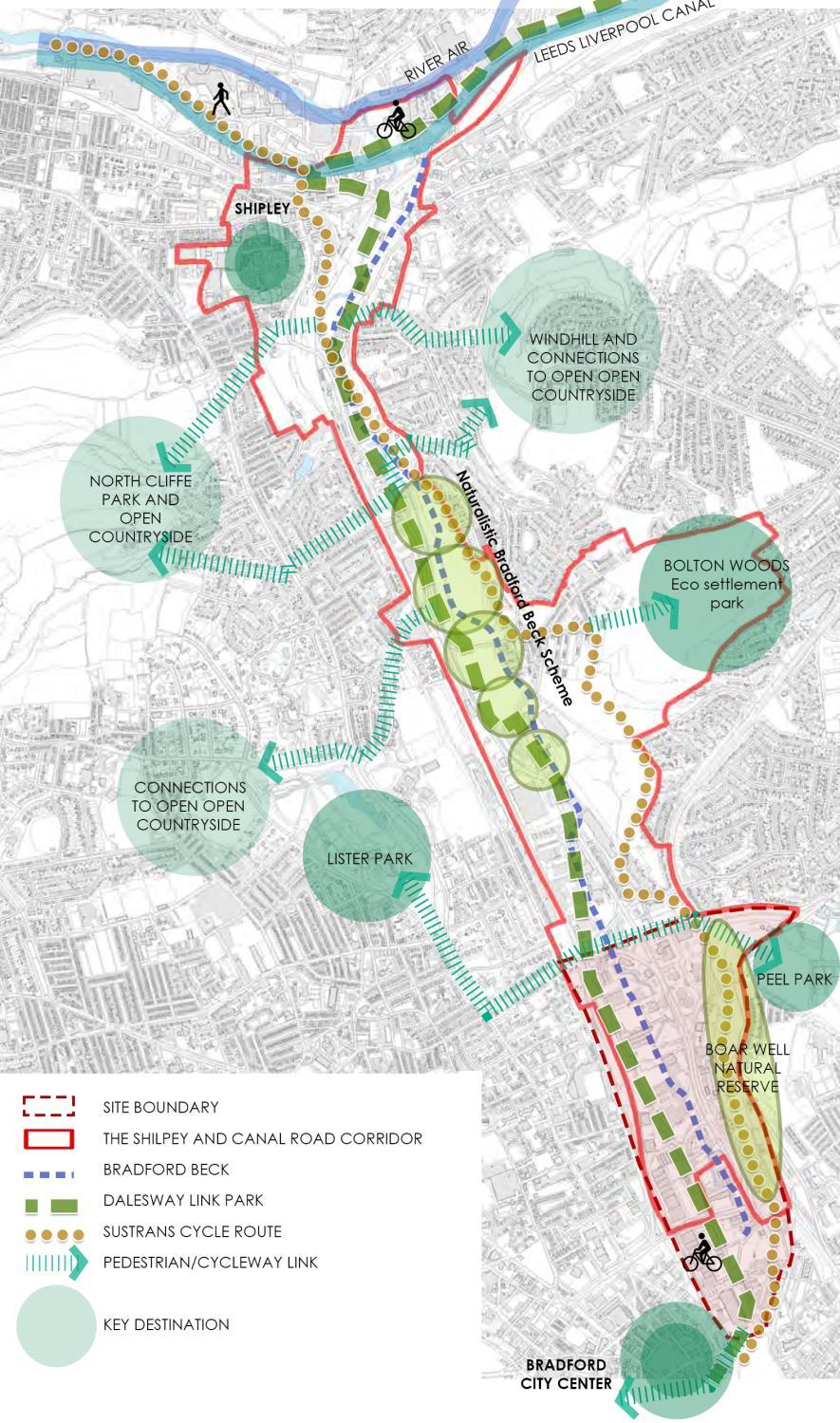

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

Green spaces within the wider context of the site in The Shipley And Canal Road Corridor. There is an abundance of green space along the corridor as large parks including Lister park, BOLTON WOODS Eco settlement park and Naturalistic Bradford Beck Scheme. And the site is at the end of the Greenway and also the gateway to the Bradford city centre with public reams as The city park Mirror and Fountain.

References through design to such a significant area may be valuable in attracting further cyclists and pedestrians. Holding very high potential as a part of green connection between Shipley and Bradford city centre. Green spaces are however disconnected from the site due to the harsh boundary of the mainline rail.

Bradford beck acts as a key strand of green infrastructure for the town and the site itself, but it is highly neglected and under-used.

Poor accessibility and the generally derelict and ruderal character of the site are factors to be addressed regarding the current underperformance of Public Right Of Way (PROW).

Promoting recreation within the proposed development would achieve stronger green links in the north and east of the site centre, potentially triggering further integration of green infrastructure into the city centre

27

BRADFORD CANAL ROAD GREENWAY

The wider context of the site reveals a network of green infrastructure with accessible routes, just like stepping stones provide opportunities for healthier alternative routes from residential areas. These provide vital links to towns and cities. Bradford Canal Road Greenway however has the benefit of sitting within the valley and provides a relatively level access route for the commute.

28

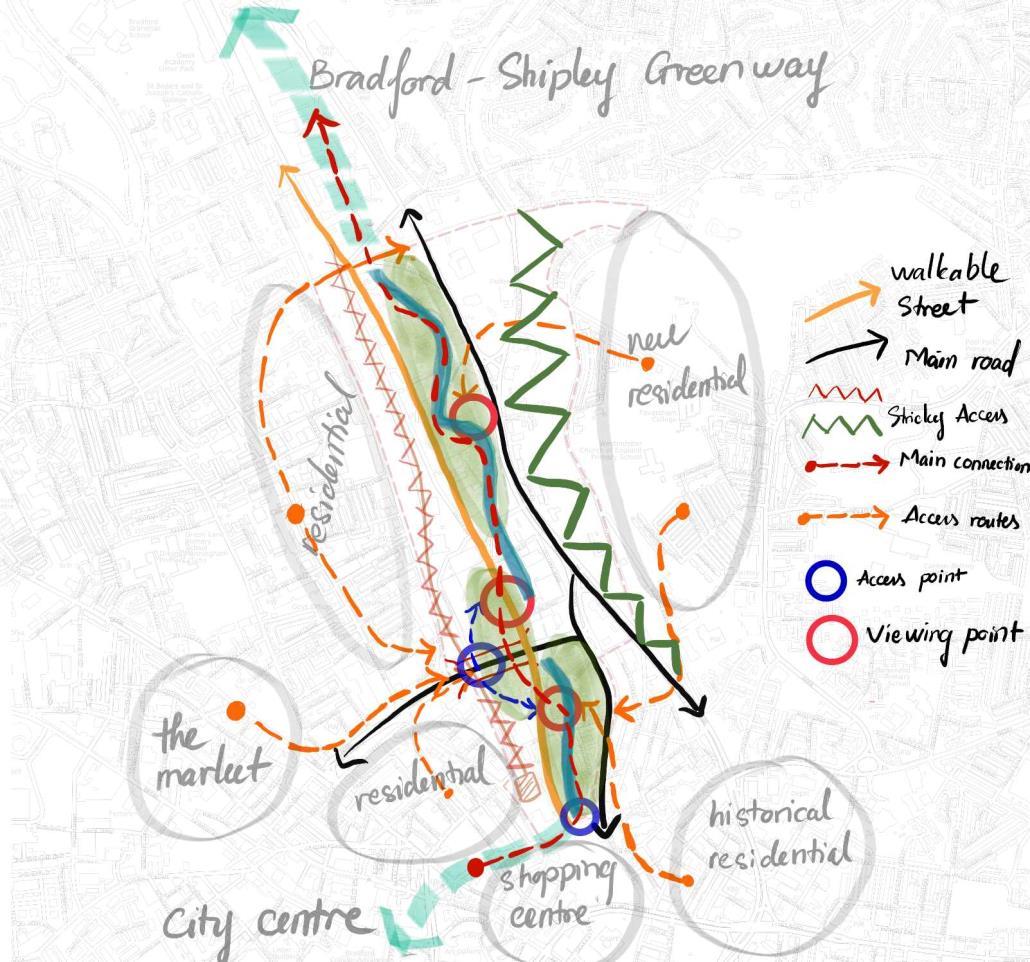

ACCESS & MOVEMENT ANALYSIS

There are Public Rights Of Way (PROWs) and Cycle Network routes extend through the site.

Accessibility into the site is generally very poor with harsh boundaries on all sides and the heavy traffic on major roads. The railway line to the west and the topography separates the site from other areas , whilst the canal road boundary cuts the site from surrounding residential areas. The only access into the town centre is via the vehicle dominated Hamm Stasse Road from the west. The access also limits pedestrians because traffic is dominated by cars and lacks safety amenities for walking.

Improved access into/out of the site must be achieved, with potential for the construction of desirable footbridges over the Canal Road or traffic calming measures over Valley Road

Access from Hamm Stasse Road

The railway separates the site

Cycle Network routes on Valley Road

Access from Hamm Stasse Road

The railway separates the site

Cycle Network routes on Valley Road

29

Access from Canal Road

PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY

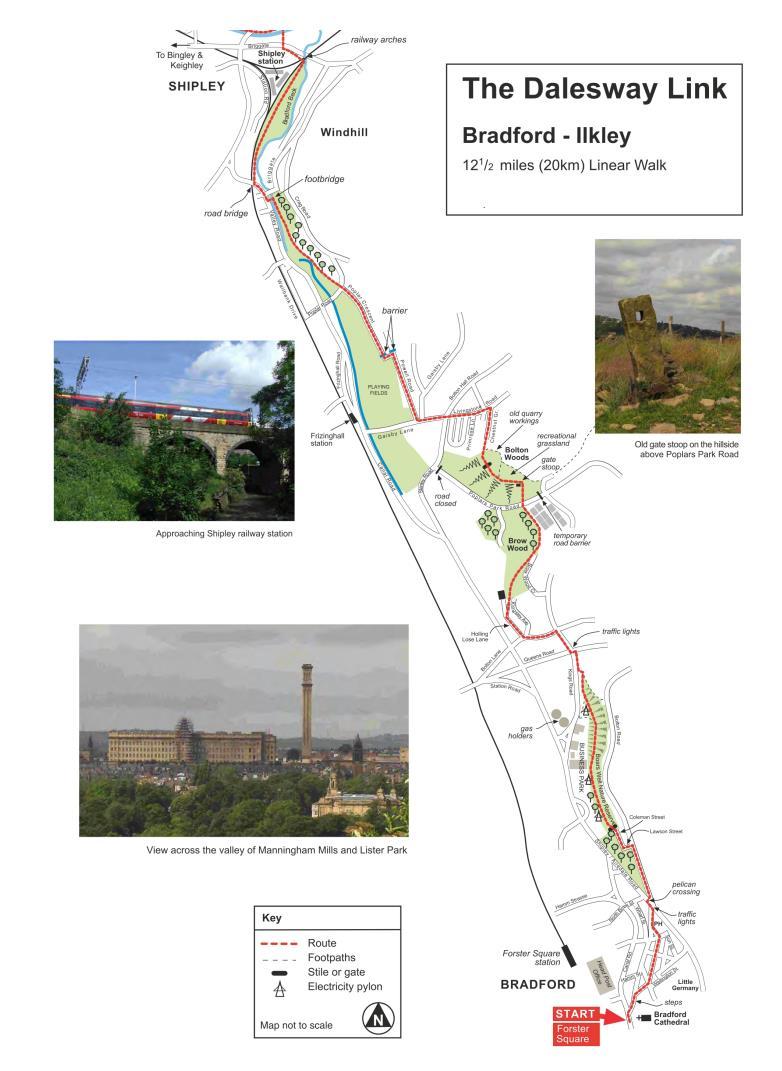

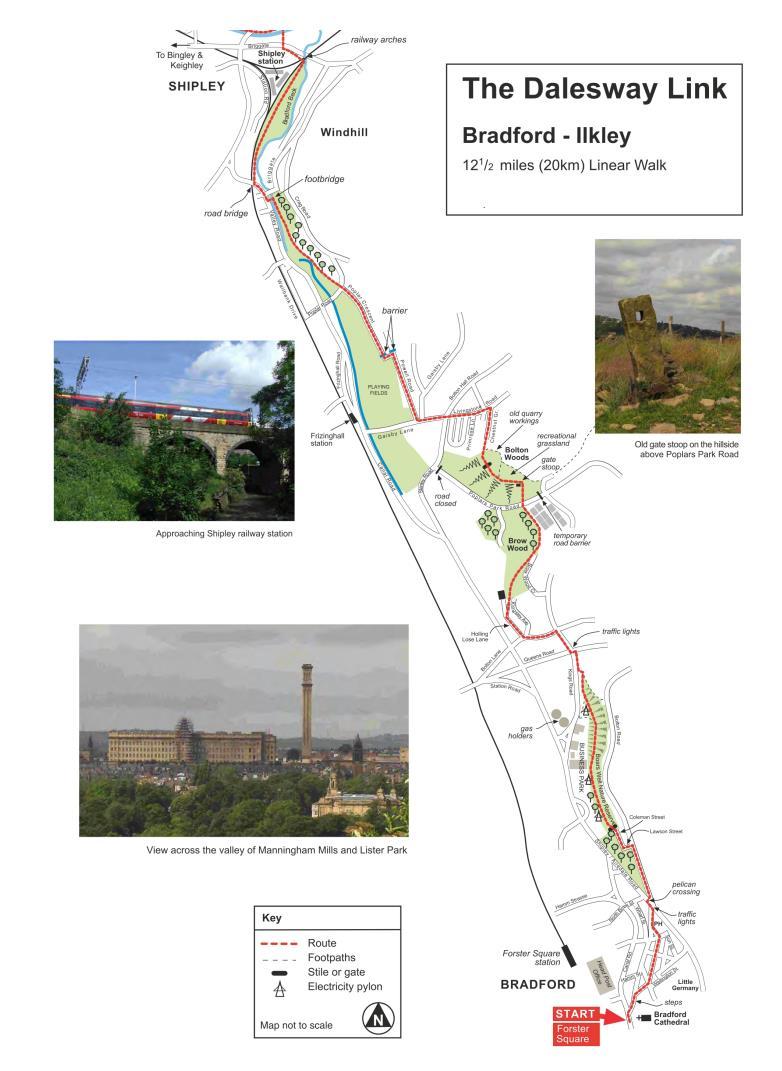

The Dales Way runs for 80 miles from Ilkley in West Yorkshire to Bowness-on-Windermere in Cumbria, following mostly riverside paths and passing through the heart of the Yorkshire Dales National Park and the gentle foothills of southern Lakeland to the shore of England’s grandest lake. There are also three Link Routes, leading from the centre of the major cities of Bradford and Leeds and from Harrogate to the start of the Dales Way at Ilkley

The site includes what the council describes as a promoted route. The council currently promotes routes that connect with regional and national walking routes.

The Dalesway is a popular route which starts at Ilkley and finishes at Bowness - on - Windermere in Cumbria. This promoted route is design to provide a link to the starting point. A section of this route extends along the greenway for approximately 1.5mile.

Dalesway Link start pointForster Square, Bradford

30

Fig.26

Fig.27

Fig.28

SSTRENGTH

The site is a defining feature of the Bradford Beck Corridor. An important element of the green infrastructure for Bradford city is improving the environmental quality of the Bradford Beck, so that it can provide an enhanced habitat and recreational asset for people and wildlife along the Corridor.

WWEAKNESS

The extent to which the enhancement of the Bradford Beck can be achieved along its full length is constrained by existing highways, buried infrastructure, land uses, land and Riparian ownerships and valley topography.

OPPORTUNITIES

The Bradford Beck is classified as ‘poor ecological quality’. This identifies opportunities for restoring the natural character of the Beck including naturalising the Beck through de-culverting covered sections of the Beck where appropriate, restoring the natural river bed, regrading river banks and introducing meanders where the Beck is cannelised.

THREAT

the introduction of sustainable and water-sensitive drainage solutions at the expense of commercial land uses. At the same time, deculverting underground water will change the topography of the area

ACTION

The Bradford Beck is indentified on the policies map as a key waterway and green infrastructure asset.

The report will support the delivery of projects to enhance the environmental quality of in the site though waterway, including the appropriate and feasible renaturalisation of the Beck.

Development of sites directly adjacent to the Bradford Beck will be expected to support its enhancement as an accessible, clean and visible waterway and habitat highway. This will include maintaining and providing site specific pedestrian and cycle links to and alongside the water

31

O T

32

03 RELEVANT RESEARCH DOCUMENTS

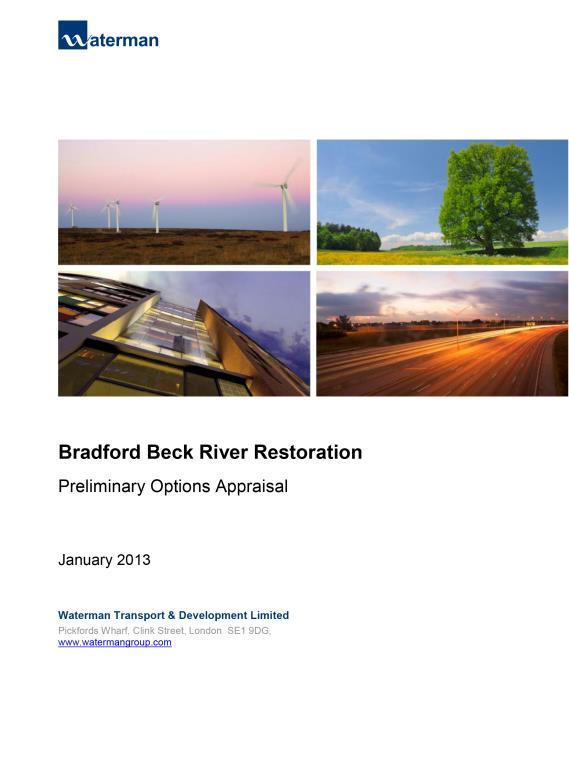

RELEVANT RESEARCH DOCUMENTS

Walks Around Bradford’s Becks

An in depth study looking at intervention to restore the natural form of Bradford Beck, including recommendations, options appraisal and benefits. Waterman were commissioned by the Aire Rivers Trust to investigate the feasibility of naturalising the Bradford Beck through the introduction of river restoration techniques

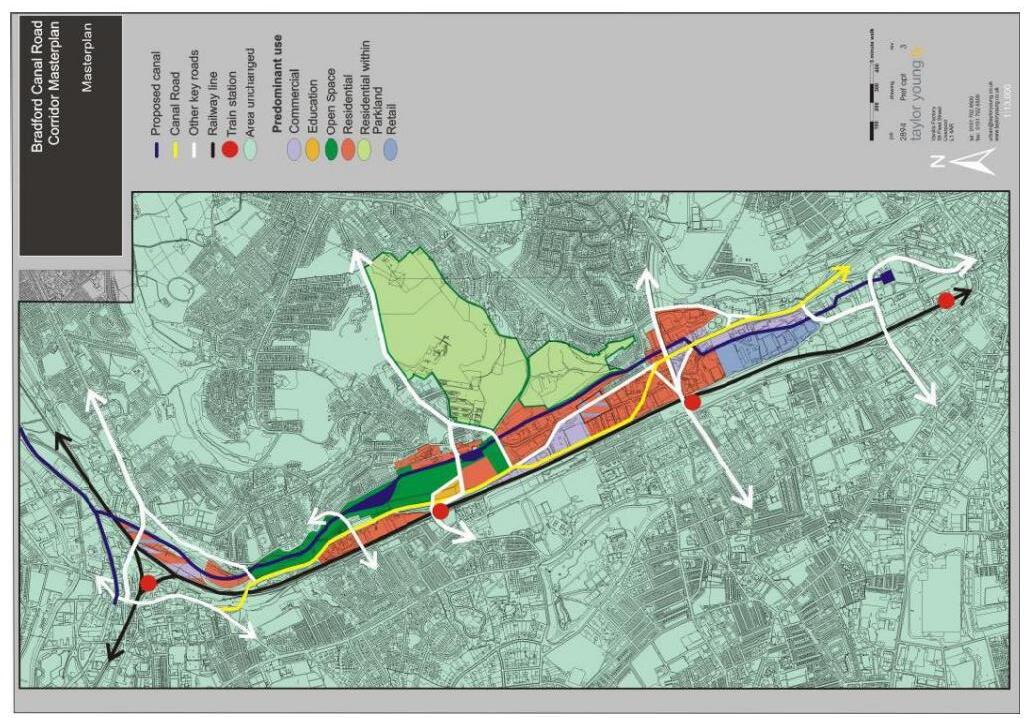

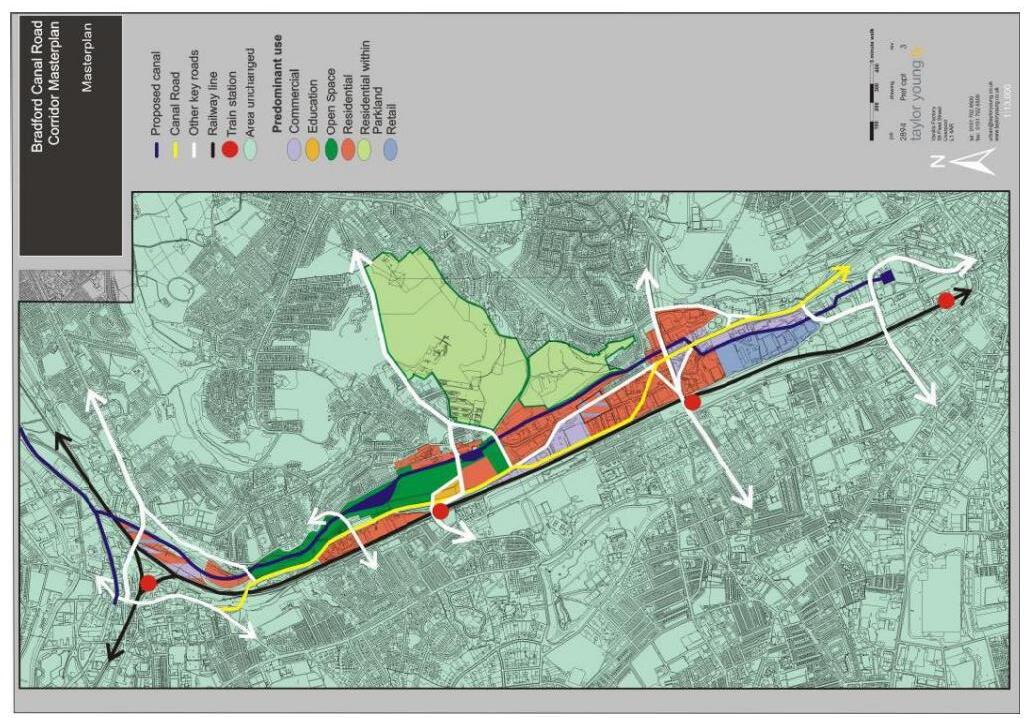

Bradford Canal Road Masterplan

Braford Canal Corridor as a priority regeneration area and includes a strong planning framework for regeneration of the area.

Bradford Regenration Masterplan

The document was the creative talent behind the city’s masterplan produced by Will Alsop and contains bold vision for the future of Bradford. It was Alsop that initiated the idea of the mirror pool a legacy which now lives on.

Ecological Assesment for the Shipley - Canal Corridor

This Ecological Assessment covers the land within both the Shipley & Canal Road Corridor and Bradford City Centre Area Action Plan areas identified in the Core Strategy as priorities for regeneration, through to 2028.

The report is an in depth ecological survey and study to ensure adverse effects on the local natural environment and biodiversity are minimised.

33

Shipley & Canal Road, Corridor Action Plan (2015)

The Shipley AAP is a 15-year development plan for the Shipley & Canal Corridor as a priority regeneration area and includes a strong planning framework for regeneration of the area.

Walks Around Bradford’s Becks

RELEVANT RESEARCH DOCUMENTS

An important reference document produced by the friends of Bradford Beck that are made up of professionals and interested members to improve the understanding and importance that the beck has to offer. The document contains information on water quality and factors affecting pollution.

Core Strategy Development Plan Document

The Core Strategy sets the strategy and framework within which all subsequent development plan documents are put together. The Core Strategy includes a spatial vision for how different parts of the district will change including the scale of development required.

This is the simgle most important document for Bradfrod Council and sets out everything the council wants to acheive and what it

34

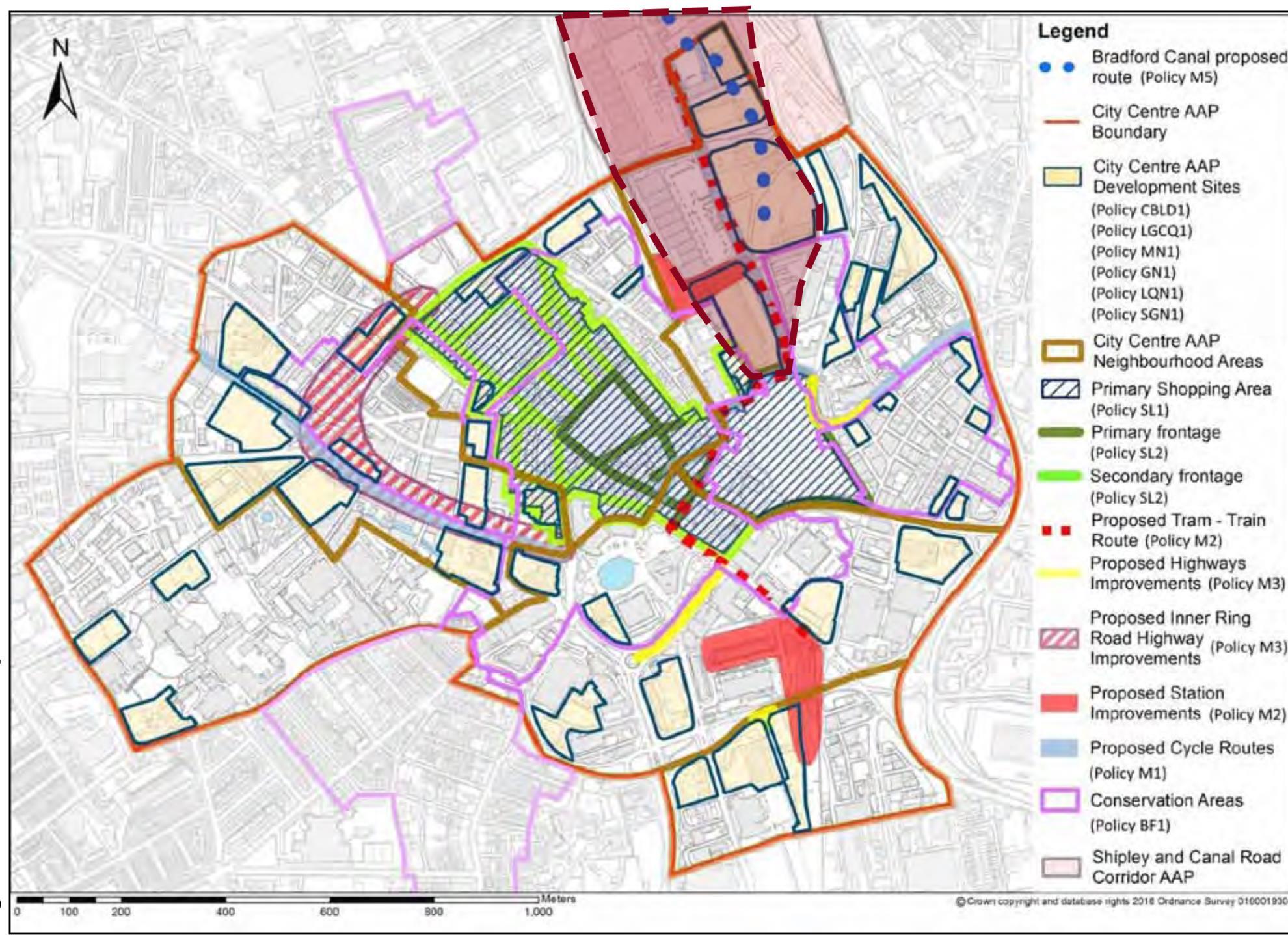

BRADFORD

CITY CENTRE

ACTION PLAN

Local Plan For The Bradford District (2007)

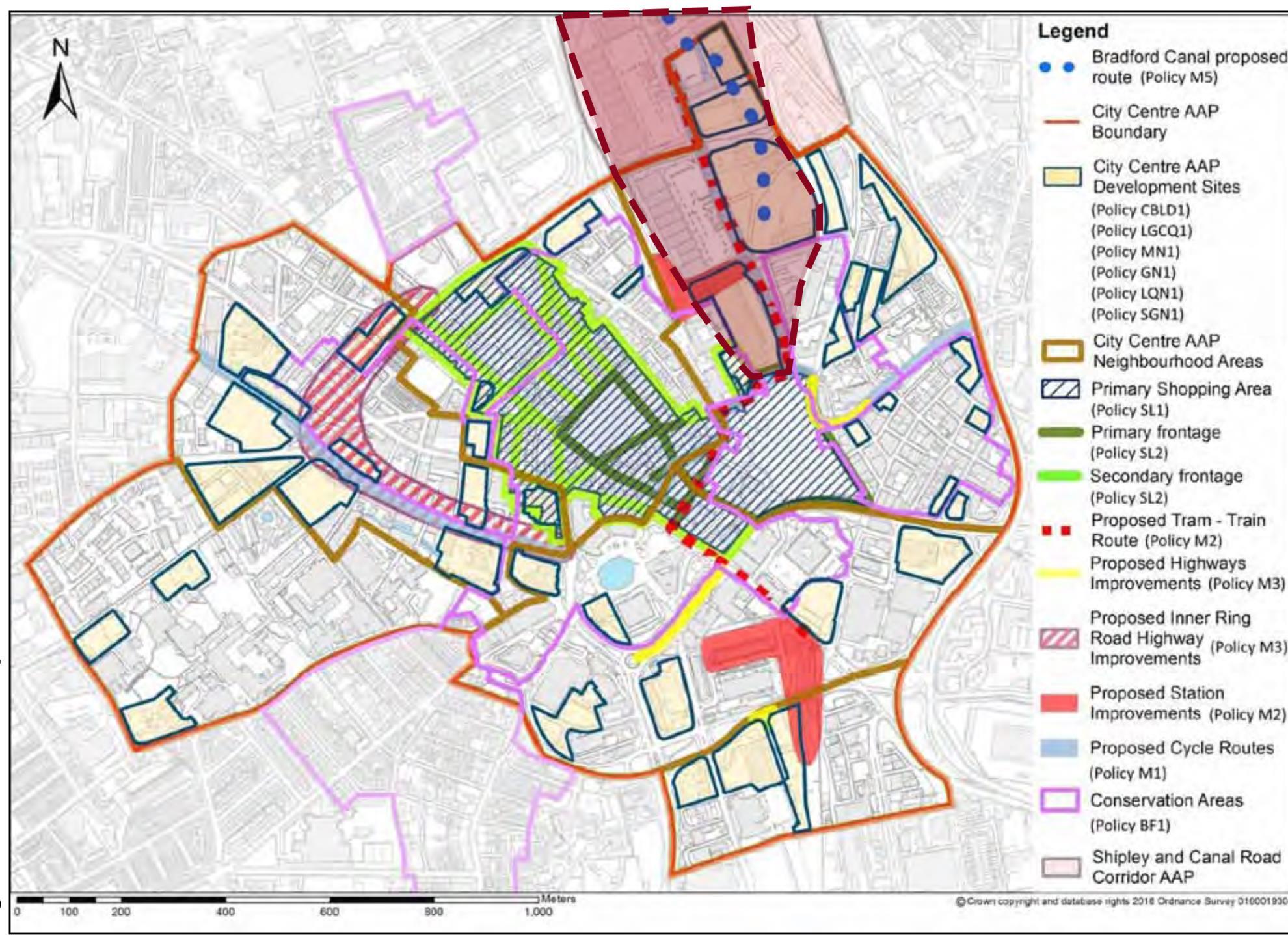

POLICY AND PLANNING

35 Fig.33

CORRIDOR

POLICY

36

BRADFORD CANAL ROAD

MASTERPLAN Shipley & Canal Road, Corridor Action Plan (2015)

AND PLANNING

Fig.34

Shipley & Canal Road, Corridor Action Plan (2015) POLICY AND PLANNING

GREEN INSFRASTRUCTURE FRAMEWORK CONCEPT PLAN

37

Fig.35

04

CASE STUDIES AND RESEARCHES

38

CASE STUDIES

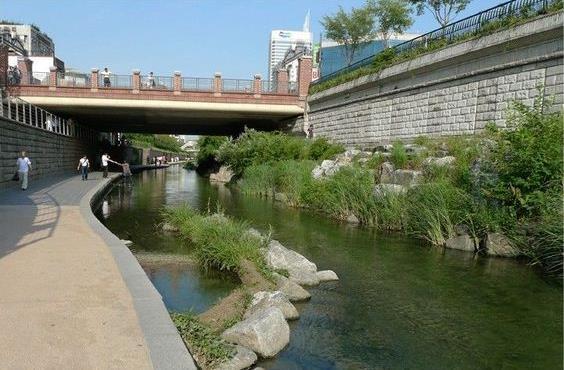

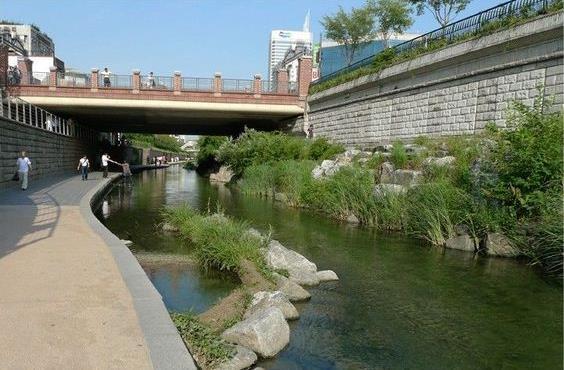

Cheonggyecheon Stream Restoration Project- Korean

The Cheonggyecheon project is remarkable for its dramatic transformation from a seedy industrial eyesore to a nature-filled public space.

Context:

The Cheonggyecheon stream had deteriorated into an open sewer and was thus paved over with concrete for sanitation reasons. an elevated freeway was built overtop the channelized river, further removing it from the public, which considered the space rife with criminal activity and illegal dumping.

Action

The outmoded elevated highway was transformed into a multifunctional, contemporary linear park.

Daylighting of a previously covered urban stream.

Creation of an extensive new open space along the daylighted stream. Creation of pedestrian amenities and recreational spaces (two plazas, eight thematic places

Benefits:

A significant increase in overall biodiversity, a reduction in the urban heat island effect and air pollution, improvement in public transit ridership and the downtown quality of life, and greater economic development in the surrounding area.

The project is a prioneer testament to how landscape regeneration brings major environmental and social benefits. with the same solution The Bradford Waterside Valley: the water return will be believed to achieve the same benefits

39

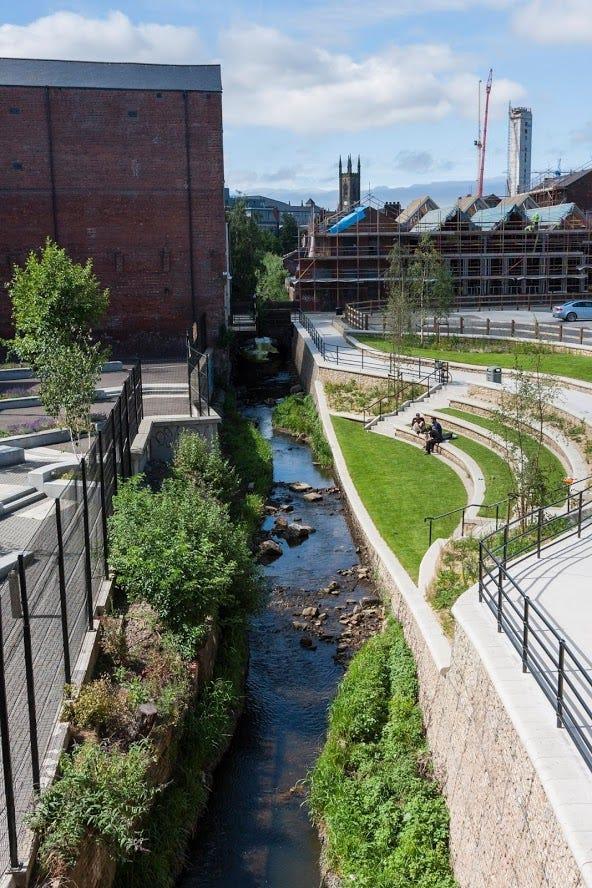

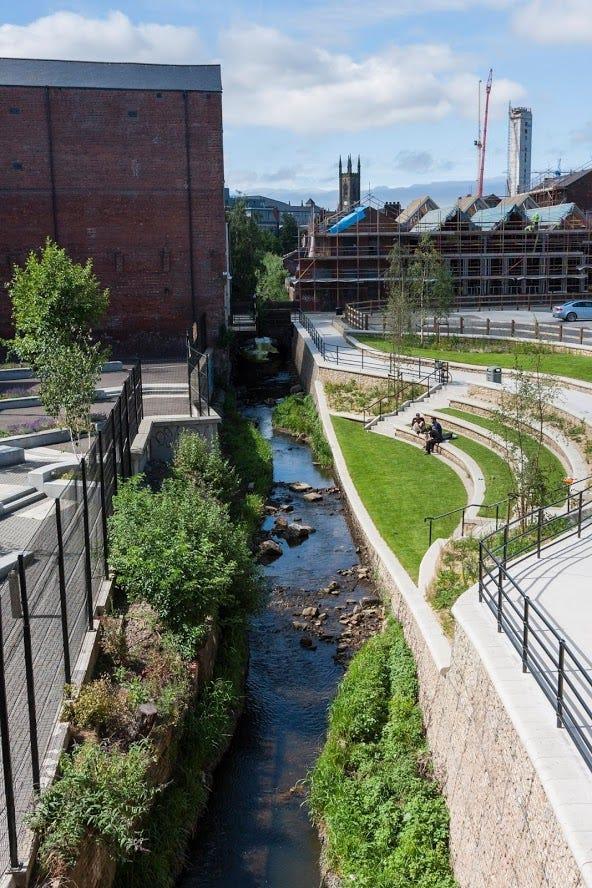

CASE STUDIES

River Porter De-Culverting, Sheffield

Partners: Sheffield City Council, Canal & Rivers Trust, Sheffield University

Context

A recent collapse of a section of the sports retailer’s car park was referred to in the media as a ‘sinkhole’, this incident tells us far more about the city’s recent history and points a way forward for its fascinating but often hidden waterways. The hole had actually appeared due to the collapse of a concrete slab culvert over the River Porter.

Culverts were constructed at a time when most of our urban rivers were dirty, noxious and devoid of life. At the time this was seen as an improvement. Along the 10km of the Porter Brook, there are about 1 km of culverts mostly in the City Centre where the latest sinkhole has appeared. This means that almost 10 per cent of the river is hidden.

This area was once at the heart of Sheffield’s steel and industrial beginnings powering flourmills, cutlery, steel and lead factories but is now being reinvented as the Cultural Industries Quarter – a place of education, innovation and city living.

In this new era the hidden rivers are acquiring a new significance as a rich restored wildlife habitat, an important element of preparation for climate change and as an attraction for investment.

Benefit

People can paddle in the Porter, and trout have been frequently spotted in its waters. This followed the removal of the culvert over the Porter, which has shown how the river bank can be restored to become a pleasant park and eventually a green corridor with reduced flood risk.

It’s been a remarkable transformation and an awardwinning one. The Porter Brook park won the ‘contribution to the built environment’ prize at the 2016 Living Waterways Awards, organised by the Canal and River Trust and which will eventually form part of a city centre walk which extends from the station to St Mary’s but it has also added significant value to the site next to it.

This project is great example of de-culverting of major watercourse and echoes strong similarities with the Bradford waterside valley: the water return. Not only does the site see the benefits of providing better access to the beck but has also provided a well-designed area of public open space in an urban area of the city.

40

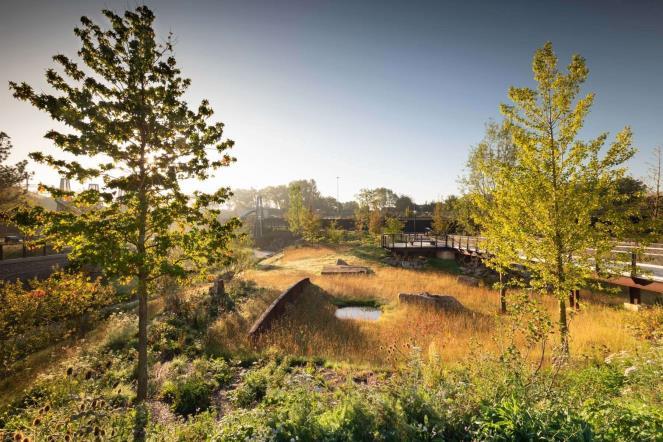

CASE STUDIES

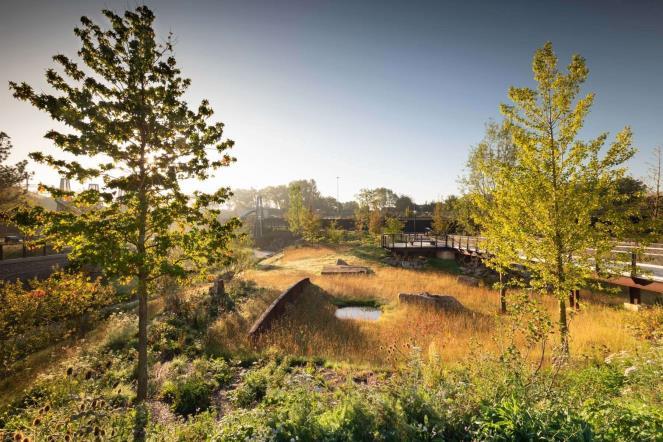

Mayfield Park, Manchester

A landscape that felt connected to its history and context, responded to the climate crisis and was balanced in its creation of habitat for wildlife and space for people.

The site was riddled with contaminates and the central River Medlock was concealed by culverts and devoid of life. On-site materials were salvaged and repaired, and innovative engineering deployed to re-use the river wall structures. Hogback beams from former river culverts were used to support three new bridges and existing wells were re-purposed to water the park. The 6.5-acre park has transformed a previously derelict area of the city into a biodiverse expanse of green and blue infrastructure. Crossing the line between civic space and urban garden, the park is a vibrant mix of water and wetlands, trees and wildflowers, long lawns, play areas and rain gardens, combining biodiverse ecological areas for wildlife with recreational spaces for visitors, all inspired by the site’s rich industrial heritage.

The Park offers a habitat in which wildlife can thrive. Opening up the River Medlock was key to amplifying nature and creating a wet-dry habitat has encouraged the beginnings of a new ecosystem which is already home to a variety of fish, birds and plantlife. In time Mayfield Park hopes to become the catalyst for change along the entire River course. Nature-based systems to accommodate flooding have been favoured (e.g. rain gardens) and the wildscape areas allow for flooding, with the riverbed planted to ensure an instant impact.

This project is a great example of renovating a site that was riddled with contaminants and a river was concealed by culverts and devoid of life. Similar aims with The Bradford Waterside Valley: the water return transformed a previously derelict area of the city into a biodiverse expanse of green and blue infrastructure. Also, what could be learned from this case study are how to reuse the former structures, and old materials and respect industrial heritage to create a sense of place.

Wildscape area with historic artefacts sat amongst floodplain meadow.

Open space, sky, trees, the natural meander of the Medlock and increased biodiversity

The site prior to intervention.

Aerial view of the ‘park first’ development. Surrounding the new 6.5-acre Mayfield Park will be approximately 1,500 homes, one million square metres of office space, a 350-bedroom hotel and retail and leisure facilities.

41

The Kallang River Bishan Park, Singapore CASE STUDIES

Bishan Park is part of a much-needed park upgrade and plans to improve the capacity of the Kallang River along the edge of the park, works were carried out simultaneously to transform the utilitarian concrete channel into a naturalised river, creating a new urban river park.

The Kallang River runs through Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park. Previously a concrete canal, it was transformed into a naturalized river with bioengineered river edges that meanders through the park so people can get closer to the water. A long-term strategic initiative to enhance the waterbodies and bring Singaporeans closer to water so that they can appreciate and cherish this precious resource.

The project’s main focus was to increase the capacity of the river channel through bio-engineering to prevent the nearby roads from flooding during heavy rainstorms, and to provide a more natural and beautiful area for wildlife and citizens.

This project is a great example of improving the river edge, transforming the utilitarian concrete channel into a naturalised river, and creating a new urban river park. This project applied bio-engineering to transform a previous concrete canal a naturalized rivers that meanders through the park so people can get closer to the water

42

STUDIES

Pedestrian area for garden city-Slovenia CASE

The Promenade in Velenje's centre forms a public space and thoroughfare for the young town. This civic space was renovated to kick off a wider revitalisation of the city centre.

Aims:

To add both greenery and event spaces to the area, on either side of the River Paka. The landscaping was planned to open up its banks and draw more attention to the stream.

Action

Angular stone terraces that vary in height and depth create pathways beside the water. Smaller steps form an amphitheatre for public performances, or relaxing in the sun. The existing bridge connecting the two river banks was replaced by a narrower structure that sits off-perpendicular to the waterway.

Benefits:

The Pedestrian area may once again claim the importance of the stream in the townspeople’s consciousness

43

CASE STUDIES

Roombeek the Brook, Netherlands

Many years ago, this city was the place with the highest number of streams in The Netherlands — including the Roombeek – but those waterways were largely contaminated due to increased industrialization. In addition, the construction of a large house hid the river from public view. City officials wanted to clean up the river and restore its public persona.

The plan for urban reconstruction was defined by long lines that have a distinctive character. In the form of water line elements in asymmetrical design, creating a micro-relief. The water in the street has different dimensions in some parts, in order to fully demonstrate the character of the river. Over the water are cracked, artificial stones similar to those found in the stream. They are of various dimensions and shapes. The presence of water also has a calming effect. Functionality and Beauty This water surface brook is not only designed to become a city symbol and a part of the urban environment, but also plays a role in the reduction of the flow of water. Lined around this water surface are deciduous trees, with interesting bark and leaf color, urban furniture such as benches and trash bins, and interesting paving.

All of these elements together form a street with visual identity and a sense of place, with recognizable structure. Functionality, sustainability, the spirit of the place, and the central point of socialization

44

Soil Bioengineering for Slope Stabilization RESEARCHES

Soil bioengineering treatments are classified as either Structural Based Soil Bioengineering treatments or Plant Based Soil Bioengineering treatments. This distinction is not just based on the material used in the construction of the treatment, but also on how the resulting treated bank or shoreline will function or behave over time to meet conservation or restoration goals.

These treatments rely on rock, dead wood, manufactured products, or other inert materials to immediately stabilize the bank and shoreline. Supplemental plant material provides aesthetic and habitat benefits as well as increases structural strength.

A Structural Based Soil Bioengineering approach is successful when it resultsin a fairly static bank or shoreline. These treatments rely on rock, dead wood, manufactured products, or other inert materials to immediately stabilize the bankand shoreline. Supplemental plant material provides aesthetic and habitat benefits as well as increases structural strength. However, if the structural material fails, the project fails, since the bank and shoreline limits are defined by the installed inert material. These projects do not allow bank and shoreline movement, and self-healing is generally not an option. Stone toes with bank grading and riparian plantings, vegetated gabions, vegetated mechanically stabilized earth (MSE) walls, root wads, some toe wood installations, and log cribs are examples of typical structural based soil bioengineering treatments

Bioengineering can be defined as:

“An approach incorporating living and non-living plant materials, in combination with natural and synthetic support materials for slope stabilization, erosion reduction, and vegetation establishment.”

THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, PART 654, NATIONAL ENGINEERING HANDBOOK, “STREAM RESTORATION DESIGN”, AUGUST 2007.

A Plant Based Soil Bioengineering results in a flexible, dynamically stable project and does not produce a static bank line or shoreline. These treatments rely on riparian plants to provide long-term strength to the bank or shoreline although the treatment may include inert material and bank or shoreline grading to promote plant establishment. A soil bioengineering treatment approach is characterized by reliance on treatments such as live clumps, fascines, vertical bundles, brush mattresses, brush barbs, brush revetments, some toe wood installations, and live cuttings.

Soil bioengineering is a proven approach to stabilize and restore streambanks and shorelines. Cost, tolerance for risk, and amount of acceptable bank movement and self-healing are factors in selecting the soil bioengineering approach.

45

How Does the Shoreline Area Provide a Habitat for Fish and Wildlife?

A natural shoreline area

Fish and frogs often spawn in the silt at the bottom of the shore and littoral zone. Vegetation provides nesting spots for birds and food for insects, waterfowl and aquatic mammals. A shoreline's natural vegetation acts as a filter, preventing sediment and unnecessary nutrients from entering the waterbody.

Recommended "soft" methods for stabilization of side bank in The Bradford Waterside Valley: the water return project

Riprap: placing large angular rocks along the shoreline to protect slopes

Vegetated Rip-Rap: The plants cover the rocks, providing shade for fish and wildlife

Different "soft" methods for stabilization of side banks

For restoration of the river bed perhaps the most challenging task is the stabilization of slopes on the banks of the river. To best preserve the shoreline environment, stabilization methods should follow these basic principles:

Imitate nature

The native vegetation usually found at the shoreline strengthens its structural integrity and prevents the land from breaking apart. The deep roots of these plants bind the earth together while their foliage and branches protect from the erosion caused by rainfall and winds. Removing these plants can cause the shore to weaken and easily crumble into the water.

Keep slopes gentle

The gradual slope of a natural shoreline absorbs the energy of waves. A steep, eroded slope or retaining wall allows waves to crash into the shore, drastically increasing erosion and causing that wave energy to cause damage on adjacent shorelines.

Employ "soft armoring" whenever possible.

By "soft armoring" we refer to live plants, logs, root wads, vegetative mats, and other methods that eliminate or reduce the need for "hard armoring", such as rock rip-rap, stone blocks, sheet-pile or other hard materials. Soft armor is alive and so can adapt to changes in its environment as well as reproduce and multiply. It also provides habitat for fish and wildlife. Vegetation can be kept trimmed so as not to block the view - after all, that's why many of us choose to live near the water!

Mix it up

Cribwall: A wooden structure that consolidates the structure of the soil and that works the front part of it.

Regardless of the type of natural shoreline encountered, you will undoubtedly see a wide diversity of materials: live trees, dead branches, stumps, rocks of many shapes and sizes, silt, sand, cattails, grasses, flowering plants, etc. By imitating this variety, you can maintain or reproduce the natural value of the shoreline and have an effective, resilient, and eye-pleasing shoreline. Working with these natural and locally available materials can also dramatically cut project costs. In the end, a mix of techniques may yield the best project, uniquely fit for your situation. If your area is already developed, it is a good idea to look to nearby undeveloped shoreline areas for examples of a more natural state. Keep it small and simple.

In some instances, only a portion of your shoreline area may be eroding. If this is the case, a small or mixed rip-rap and vegetation project may suffice. Keep in mind that healthy trees are often the cornerstones of a stable shoreline.

46

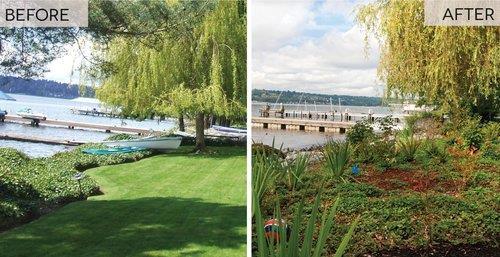

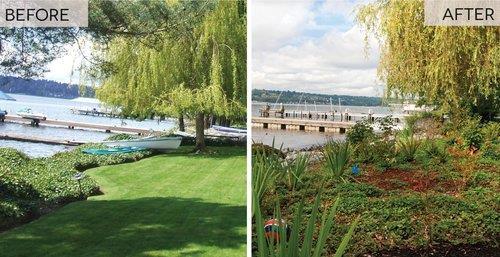

Naturalized Landscape Design RESEARCHES

Naturalizing your local park or backyard can provide a multitude of benefits to you, your community and the environment. Natural landscapes eliminate the need for chemical weed and insect control that might damage your health and the environment. And, over the years, they require less work than lawns, giving you more time to enjoy nature in your own backyard. This Extension Note provides information on some of the many benefits of backyard naturalization, as well as factors to consider when planning a naturalization project for your property

47

BENEFITS OF NATURALIZATION

Naturalization has numerous benefits:

ATTRACTING WILDLIFE

By naturalizing your local park or backyard, you can provide habitat for many plant and wildlife species. The kinds of wildlife will depend on the location, size and type of habitat created. If you live close to a ravine, woodlot, field or park, you can attract a wide range of species. On the other hand, if your property is an isolated island of greenspace within an urban environment, you will draw fewer species. You can tailor your design to attract specific species of wildlife by creating different habitats (food and cover). For example, forest habitat of tall trees such as oaks provide an upper storey canopy for orioles and acorns for squirrels. Ground cover or low shrub plantings can provide habitat for song sparrows. Wildflower meadows provide habitat for butterflies. You may experience conflict with some wildlife as a result of your naturalization project. You can try to tailor your efforts to selectively attract species of wildlife that you like. However, you should be prepared to be tolerant of most urban wildlife including birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians before undertaking a naturalization project.

ELIMINATING CHEMICAL LAWN TREATMENTS

Chemical fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides can give you a tidy lawn, but they may also kill insects, invertebrates, bacteria, fungi and other forms of life. Ninety-nine per cent of yard insects are beneficial. They pollinate flowers, help leaves and other material decay, aerate the soil, release nutrients and sustain the natural cycle of life. Not only do these chemicals kill insects, they may also do lasting damage to human health and the environment. Going natural in your backyard allows you to rely on alternatives to chemical treatments. Instead of fertilizing your lawn, you can enrich your natural area with compost. With a balanced, natural ecosystem in your backyard, you won’t need insecticides. And, if you plan your natural area well, you can do required weeding by hand, instead of using herbicides.

REDUCING LAWN MAINTENANCE

Reducing your reliance on chemical treatments means less work for you. If you retain a small patch of lawn for lounging or playing sports, eliminating fertilizers means you won’t have to mow as often. And, as an added bonus, you might have fewer skunks. That’s because less mowing means less thatch, and less thatch means fewer grubs a favorite food of skunks.

NURTURING NATIVE SPECIES

Naturalizing assists native plant species to compete with non-native plants (introduced species). Nonnative, invasive plants can displace native plants resulting in reduced habitat for wildlife that depend on these native species for food and shelter.

Naturalistic plating

Wildflower meadow

Renaturation

of the River Aire

of the River Aire

48

RESEARCHES

Water For People - Cities Alive

Climate change is the forefront of future planning and design. It is becoming a huge issue for the sources Earth provides us with, as they decline, we need to plan ahead of the damage that is occurring and will continually increase, in order to protect the planet. Atmospheric carbon dioxide is continuously on the rise and the likely hood of it being a result of human activity is a 95% probability.

‘‘As the climate changes, so will the freshwater and saltwater resources that form the foundations of our communities and economies. And as the climate changes, so will so must—our relationship to water.’’

- National Geographic

The biggest impact from climate change is the weather. The debate has shifted to how and when the issues will occur, not if. As we continue to pump Co2 into the atmosphere, the trapped gas, along with other greenhouse gasses, will warm up the planet causing global warming. The warming of the plant will cause our water sources to evaporate much quicker, thus causing more water particles in the air causing heavier and more frequent rain fall, the latest term is ‘cloud bursts’. Most cities are not design to take on this amount of water, so this leads to flooding. Which has many issues within itself, to the economy, to lives and ecosystems. Blue Infrastructure is just as important as Green Infrastructure, working hand in hand to create spaces that maintain, manage and improve ecosystems. The combination of Green and Blue Infrastructure encourages a healthier environment, enhances air quality, filters pollution and regulates temperatures, especially in cities. Nature based solutions have a huge impact on the environment and offers more opportunity’s then ‘grey’ infrastructure. By achieving positive water management, it will result in the cities resilience to the inevitable issues of climate change.

49

RESEARCHES

Sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) Application

Blue infrastructure refers to a network of natural and semi-natural water features and spaces in urban environments, designed to manage water sustainably, provide ecosystem services, and enhance the quality of life for urban residents.

Urban stormwater management is the effort to reduce hard surface runoff from rainwater, tackling issues of flooding, erosion pollution of watercourses and infrastructure damage. It is a concept that aims to integrate water into urban planning and development, recognising that water can be an asset rather than just a potential problem in urban areas.

Image demonstrates the impacts of urbanisation on a catchment by reducing its permeability and increasing surface water runoff. This reduces opportunities for water to be managed naturally with the potential for pollution and localised flooding when the piped systems cannot cope with rainfall.

Blue infrastructure includes elements such as rivers, lakes, ponds, wetlands, green spaces, and sustainable drainage systems (SuDS).

Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems techniques include:

1. Green roofs

2. Permeable surfaces where pain passes through the surface, either through gaps between individual blocks or permeable material such as gravel or porous asphalt, trapping pollutants below

3. Infiltration trenches filter drains and filter

4. Swales - shallow drainage channels. It can be used to channel run-off from roads, yards and car parks where it collects into pools before soaking away. You can also use swales to carry water through a site.

5. Detention basins, purpose-built ponds and wetlands

50

51

05 DESIGN CONCEPT

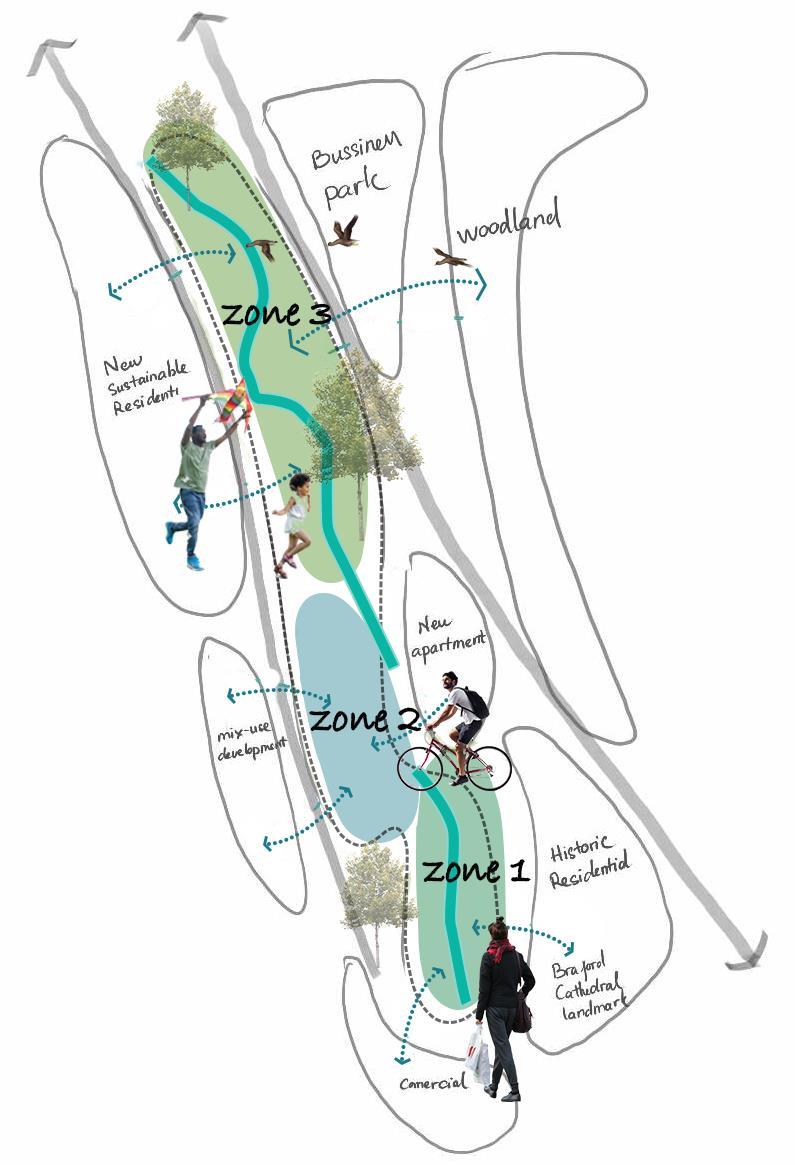

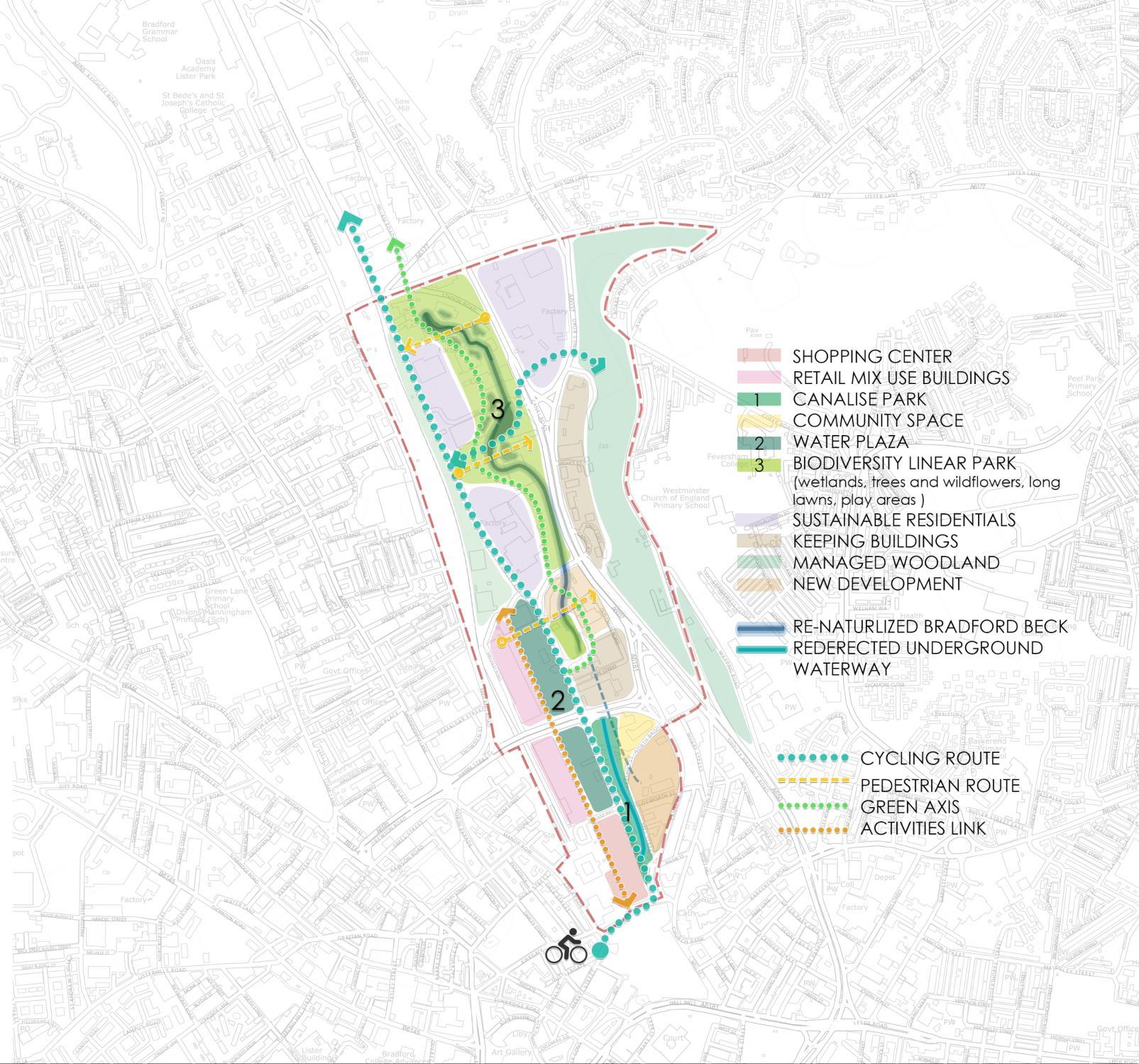

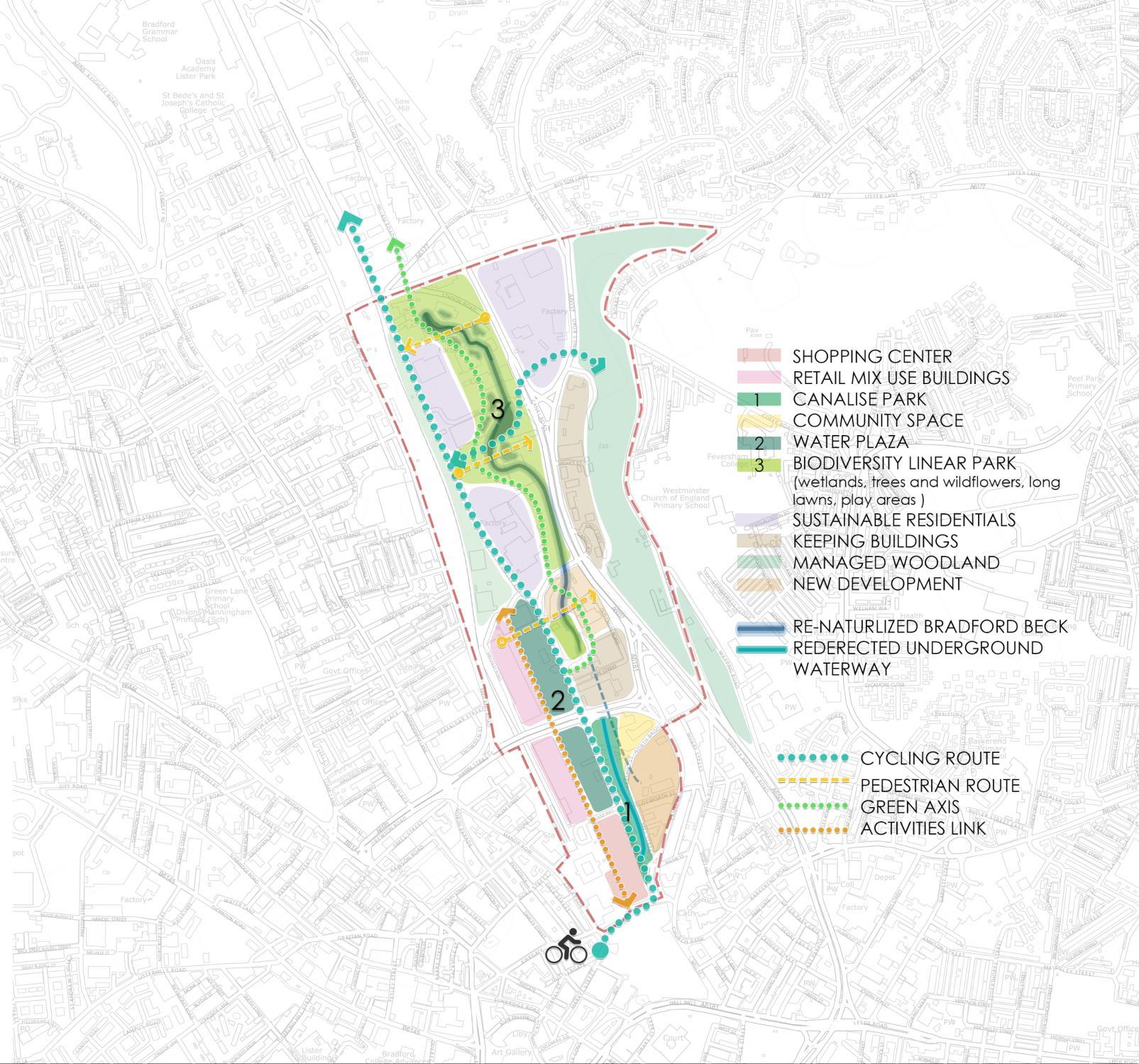

VISION

‘Bradford Waterside Valley: the water return’ will be a nature corridor in the middle of the city which enhances biodiversity habitat, creating an active and resilient bradford city center gateway where people are proud of where they live, learn, work and play

52

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES GREY TO GREEN CONNECTIVITY VITALITY

Ecosystem regeneration

Use nature

the main approach to improve environmental conditions in ruderal character areas, grey infrastructure featuring greens. introduce an ecologically sensitive development, enhance biodiversity and wildlife by creating habitats and green corridors along the re-naturalised Bradford Canal corridor.

To leave the site in a better condition and be more diverse, Increased habitat creation and biodiversity net gain

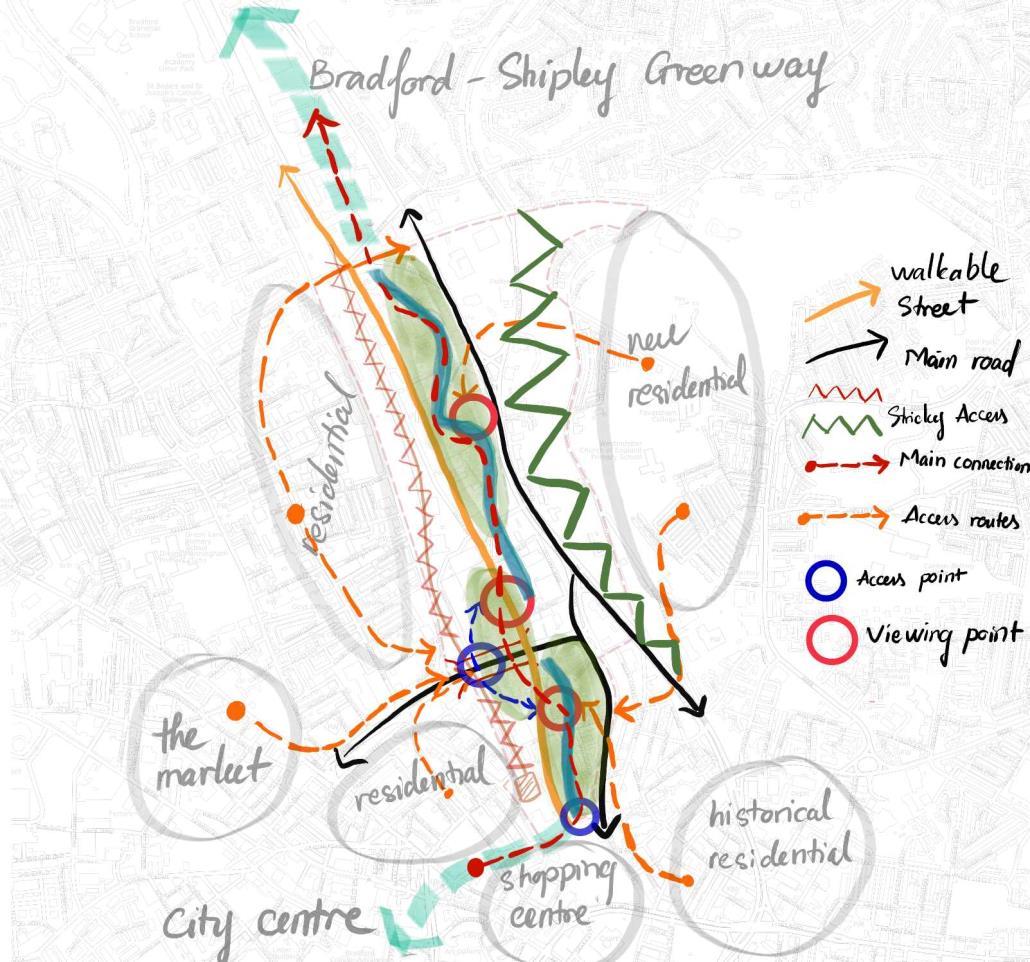

Re-connect communities that have been restricted by major highways and rail networks.

Connect humans with nature

Connect to the surrounding area by establishing green corridors and discourage traffic through the corridor to provide a healthy and attractive alternative cycle and pedestrian route, be a part of the Bradford to Shipley corridor and beyond.

Create a multi-functional space benefiting the community with nature. Open up missing connections to reconnect communities that have been restricted by major highways and rail networks.

The liveliness of a friendly Bradford.

Creating cultural and livable spaces, and providing balanced development between different areas within the city. restoration of a natural environment and enhancement of the quality of life; boost and culture; and revitalization of the economy

The essence of the restoration strategy was “space creation” – a place where the city’s residents could enjoy the ‘liveliness of a friendly Bradford.’

A resilient approach to design.

Introducing a sustainable urban development paradigm; to promote the recovery of eco-friendliness. A resilient approach to design ensure that Bradford canal Valley will survive in the long term by tackling future challenges flood mitigation and water management

53

KEY MOVES

ENVIROMENTAL

Nature-based solution Ecosystem regeneration

Water feature restoration

Wetland Riverbank greens

Action for adaptation, resilience and mitigation

Habitat and biodiversity restoration

Water management

Flood protection

Stormwater and rainfall management and storage

Improvements to water quality

SOCIAL COMMECIAL

Community Engagement

Flea Market , Events, Squares and flexible social spaces

Active Use

Informal/natural play

alternative cycle and pedestrian route

Action to Regeneration, land-use and urban development

Promotion of naturalistic urban landscape design

Tourist attraction

54

ENVIRONMENTAL KEY MOVES

Ecosystem regeneration

The new ecological qualities of are regenerate to the site is a highly important consideration. By Re–introducing water back into Bradford City Centre, the place can become an green asset and driver for tourism itself.

Methods of enhancing the water corridor and surrounding areas within the site:

• By re-naturalising the existing culverted water course Bradford beck and Bradford canal. To Connect human with nature, To enhance ecological habitats base on water course: wetland, sponge park

• Creating linear parks for residential development.. It will also deliver a safe home for nature, improve air quality and reduce noise pollution from transport

55

ENVIRONMENTAL KEY MOVES

Water Management

An water-sensitive city within the return of the water in city will be a key focus on proposed interventions in order to ensure the sustainability of all aspects within the new community. Lying on the valley, the site must look to achieve effective alleviation of potential flooding.

Interventions aiming to water management may include:

• 'Sponge' wetland parks

• Rain gardens, swales and other forms of Sustainable Urban Drainage systems (SUDs)

• Catchment basins.

56

SOCIAL KEY MOVES

Community Engagement

Renew isolated city spaces as creative and connected public destinations which enhance public life.

Community-based interventions within the site itself will include uses and strategies which encourage social interaction on a daily basis for local residents and members of the public alike, such as:

• Community gardens & allotments

• Flea Market , Events

• Squares and flexible social spaces

57

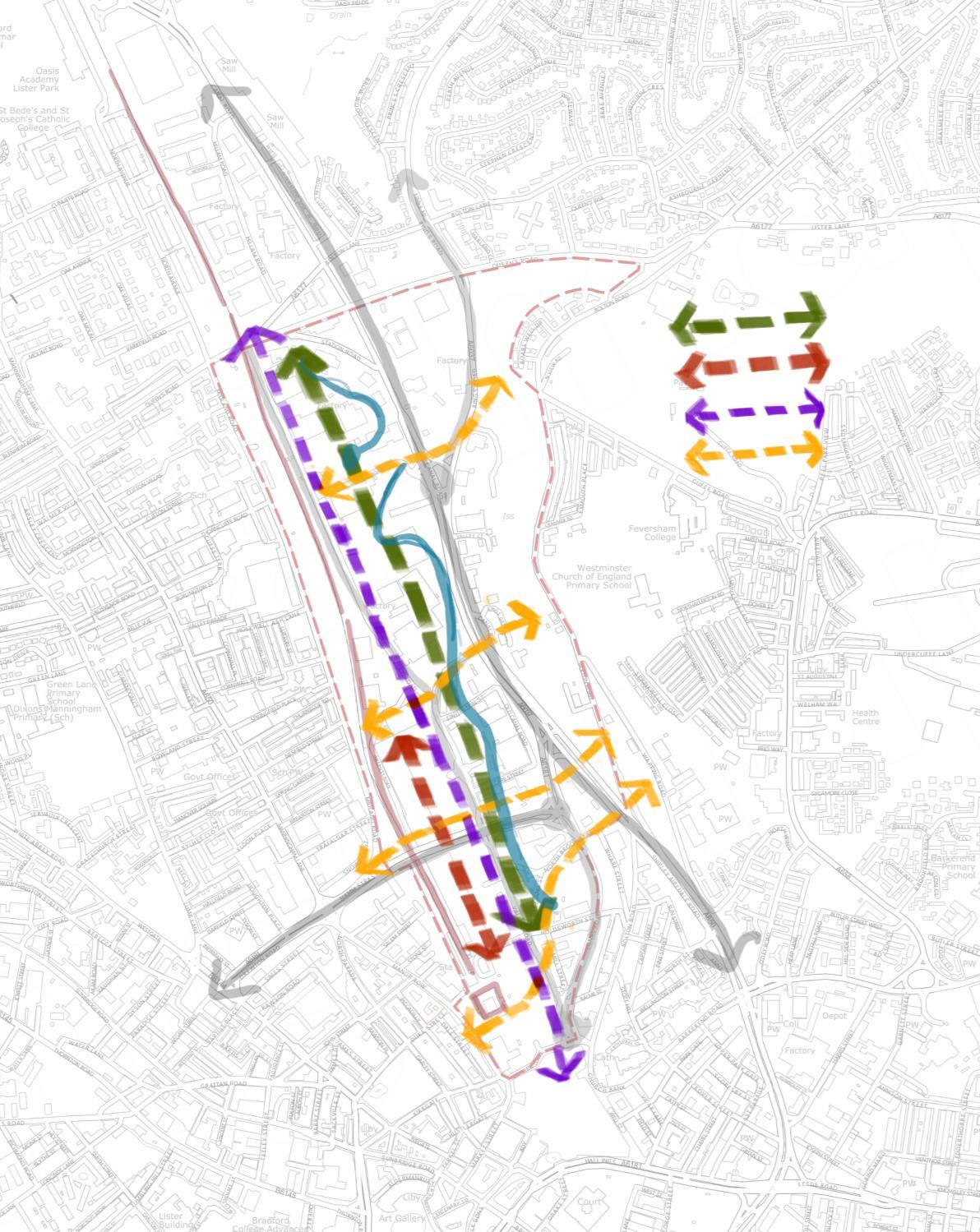

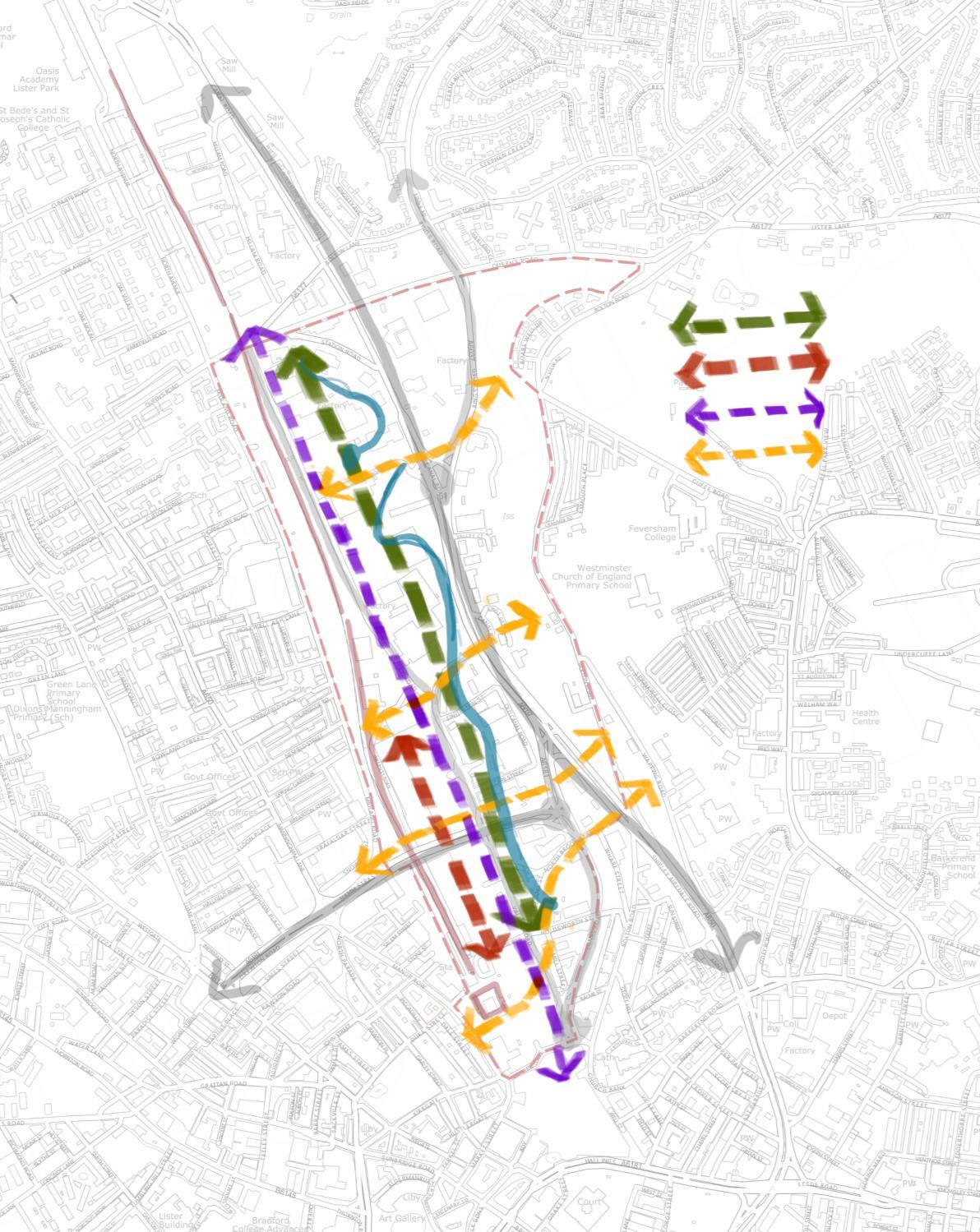

Green corridor

Cutural connections

Cycle path

Pedestrian path

Access points from surrounding residential areas that need to be

emphasized and directed for access to the site.

Proposed location improve access restrictions

SOCIAL KEY MOVES

Active Use and Accessibility

Injecting the site with a vibrant range of new activities will engage locals and tourists alike.

Offering sources of recreation to the public, providing means of recreation will also be key in engaging with users of the site, including cyclist routes along the central Public Right Of Way (PROW) A series of green spaces within recreation and leisure which is accessible nd desirable to younger generations may achieve an influx of activity along the proposed waterside development.

New forms of recreation and activity may include:

• Informal/natural play

• Events

• To provide a healthy and attar`ctive alternative cycle and pedestrian route

58

COMMERCIAL KEY MOVES

Commercial Injection

Tying into surrounding commercial areas to the south and city center areas of the immediate site context will significantly strengthen the character of the area.

• Commercial square

• Commercial park

• Retail park

59

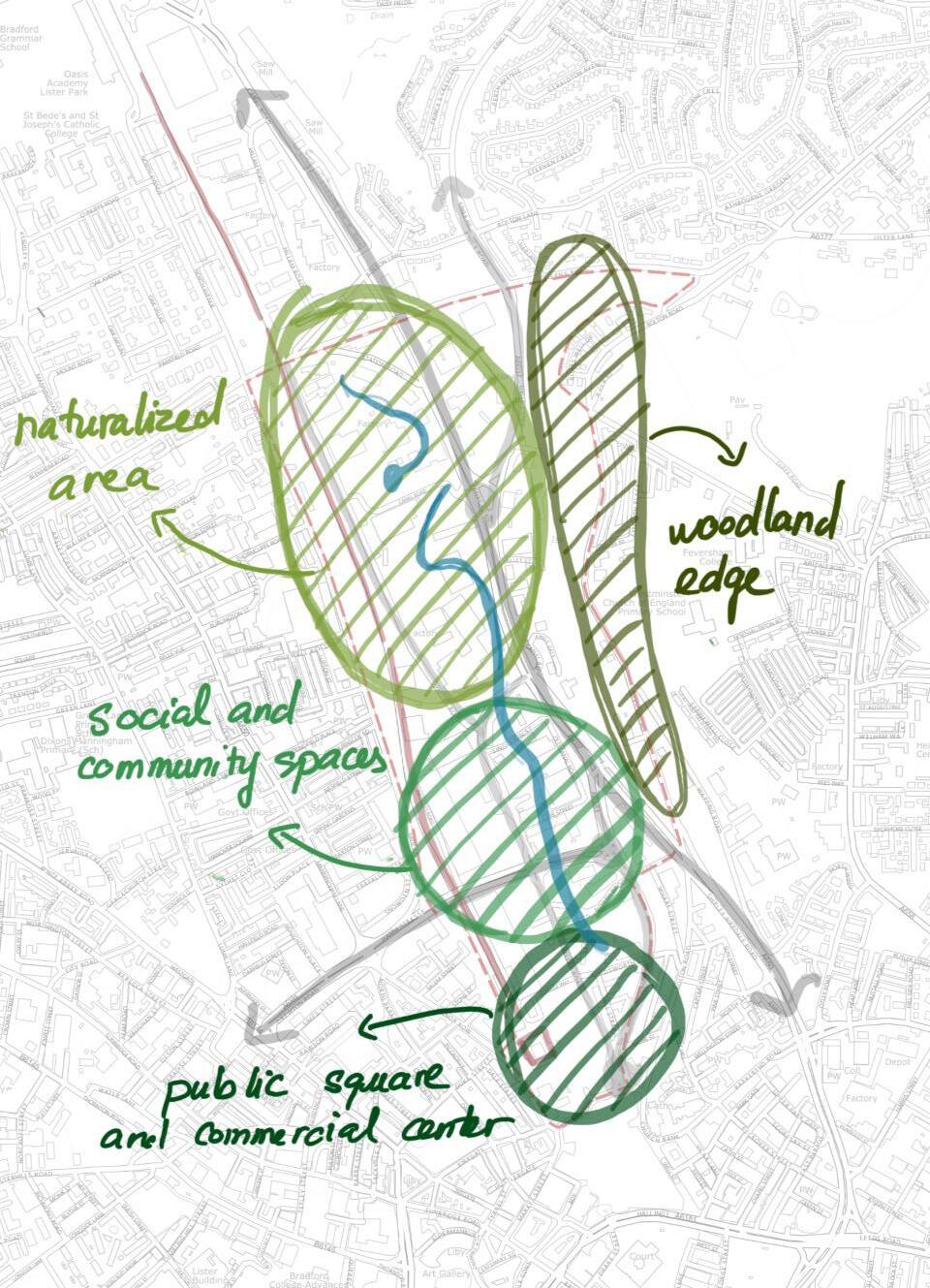

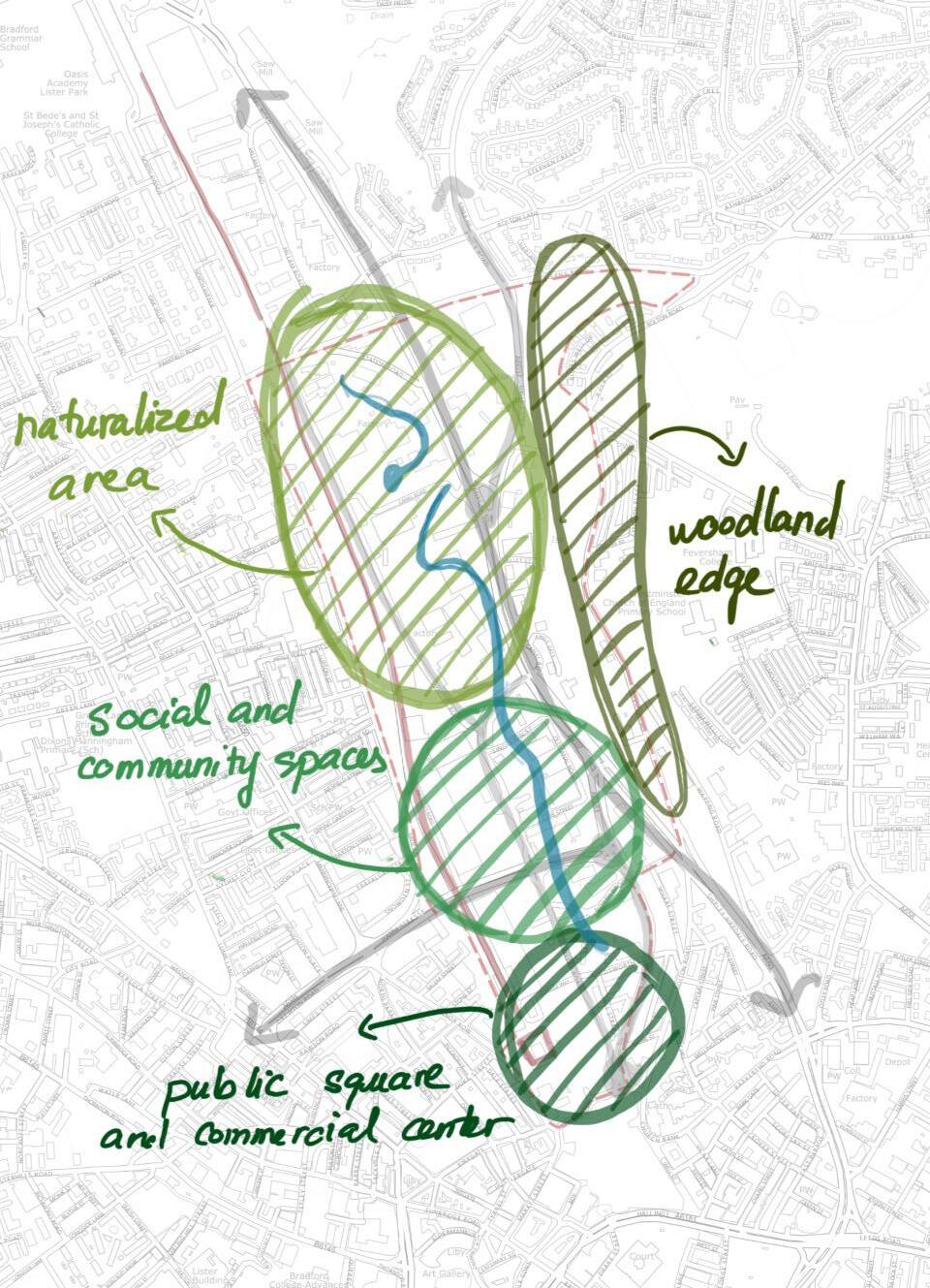

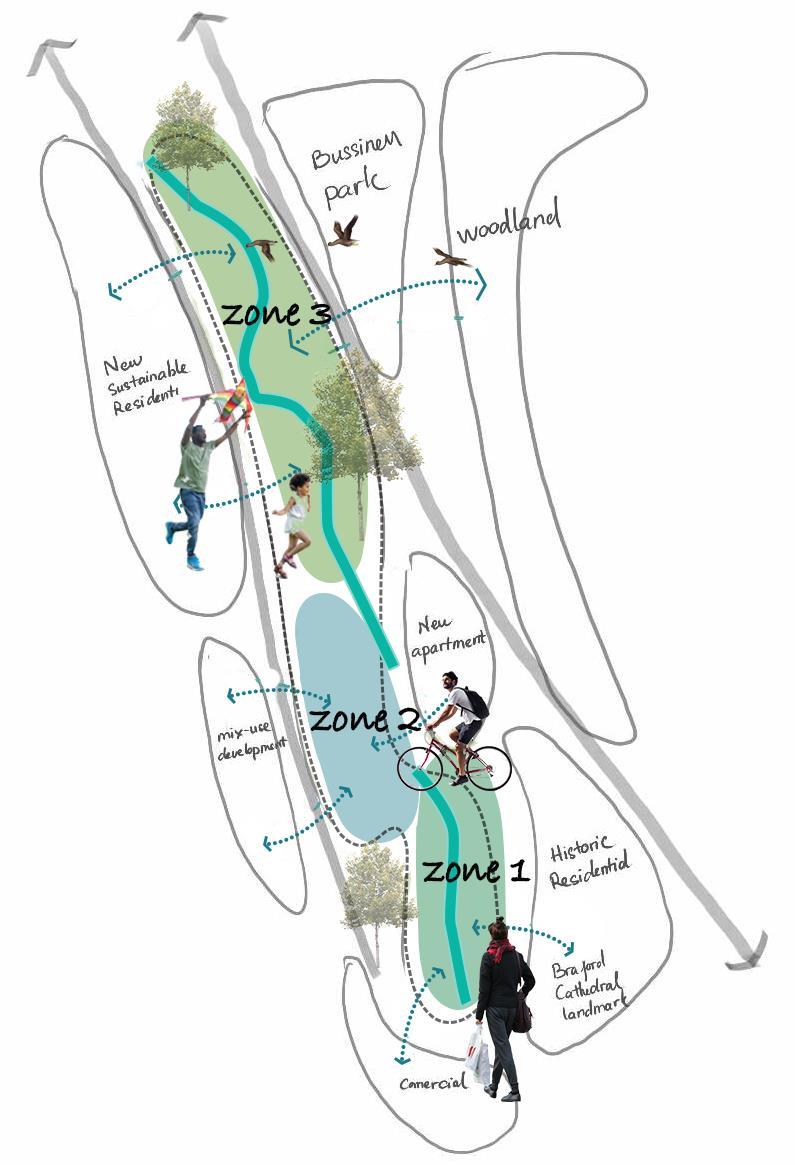

CONCEPT

SENSE OF PLACE

ZONE 1: HISTORIC AND CANALSIDE

ZONE 2: URBAN AND CULTURE

ZONE 3: NATURE IN THE MIDDLE OF THE CITY

FROM HISTORY TO FUTURE

PROPOSED GREEN CORRIDOR

WATERSIDE CULTURE NATURE 60

ZONING

61

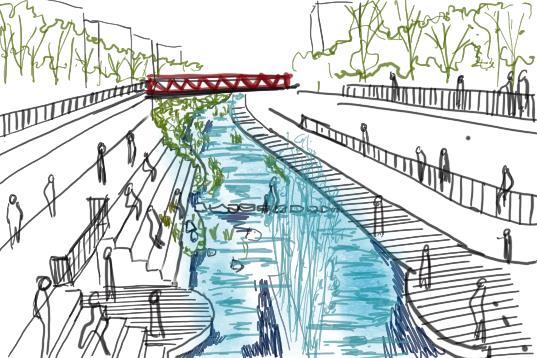

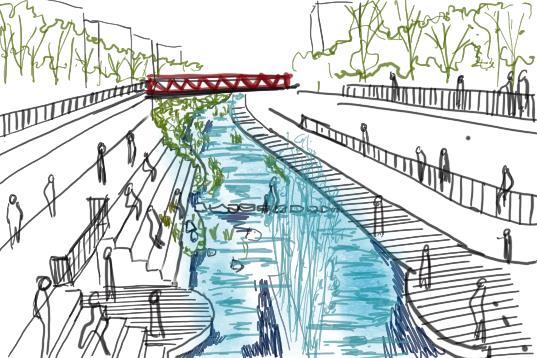

SKETCHES

WATER SQUARE

• Square

• Cycle bridge

• Amphitheater

62

SKETCHES

Softscape area in south of the beck

• Re-naturalised

• Enhance biodiversity

• Wetland habitat

63

FIGURE

• Figure 1: Green, T. (2012). A sunny day in Bradford City Park. flickr.com. Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/atoach/7956957816/in/photostream [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 2: Shipley Canal Road Corridor. (n.d.). North Sea Region. Available at: https://northsearegion.eu/begin/bgi-pilot-projects/bradford/.

• Figure 3: Town Hall, Bradford. (2019). Prolific North. Available at: https://www.prolificnorth.co.uk/news/bradford-announces-plans-city-culture-bid-costing-ps14million/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 5: Peel Park Residential. (n.d.). Gillespies. Available at: https://www.gillespies.co.uk/projects/peel-park-quarter/[Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 6: Bradford Cathedral. (n.d.). Art Together Leeds. Available at: https://artstogetherleeds.co.uk/venue/bradford-cathedral/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 7: Junction 27 Retail Park. (n.d.). Completely Retai. Available at: https://completelyretail.co.uk/scheme/junction-27-retail-park-leeds-2810 [Accessed 9 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 8: Bradford The Broadway Bradford. (n.d.). Visit Bradford. Available at: https://www.visitbradford.com/things-to-do/shopping/the-broadway-bradford-p1621521 [Accessed 11 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 9: White Abbey Bradford. (n.d.). Prime Location. Available at: https://www.primelocation.com/for-sale/property/west-yorkshire/bradford/white-abbeyroad/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 10: Bradford Central Mosque. (n.d.). Arab News. Available at: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1811661/world [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 11: Bradford Forster Square railway station. (n.d.). England Rover. Available at: https://englandrover.com/listing/bradford-forster-square-railway-station/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 12: Bradford Centenary Square. (n.d.). Visit Bradford. Available at: https://www.visitbradford.com/things-to-do/city-park-p1623731 [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 13: Bradford Interchange. (n.d.). England Rover. Available at: https://englandrover.com/listing/bradford-interchange/ [Accessed 8 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 14: Bradford: Medieval Times. (n.d.). Bradford Beck. Available at: https://bradfordbeck.org/history/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 15: Bradford: Industrial Revolution: 19th Century. (n.d.). Bradford Beck. Available at: https://bradford-beck.org/history/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 16: Bradford: 20th Century. (n.d.). Bradford Beck. Available at: https://bradfordbeck.org/history/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 17: Aerial view of barges on the Leeds-Liverpool canal c.1950. (1950). Bradford Museums. Available at: https://bradfordmuseums.org/hidden-from-view-the-bradford-canal/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 19: Schematic Map: The Catchment of the Bradford Beck. (n.d.). Bradford-Beck.org. Available at: https://bradford-beck.org/catchment-management-plan/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 20: Turbid odorous discharge from a food processing factory entering Bradford Beck. (n.d.). Bradford-beck.org. Available at: https://bradford-beck.org/urban-pollution-hunter/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 22: Downstream of the Yorkshire Water tank on George Street. (2022). bbc.co.uk. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bradford-west-yorkshire-62212673 [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 23: Bradford Beck running orange. (2015). Multi-Story Shipley. Available at: https://multi-storyshipley.co.uk/indexb648.html?p=936 [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 24: Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for City of Bradford MDC. (n.d.). bradford.gov.uk. Available at:

https://www.bradford.gov.uk/documents/citycentreactionplan/2%20publication%20draft/evidence %20base/sfra%20level%202%20appendix%20a.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 25: The Dales Way from IIkley to Bowness on Windermere 80 Miles. (n.d.). dalesway.org. Available at: http://www.dalesway.org/route.html [Accessed 11 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 26: Dalesway Link start point - Forster Square, Bradford. (n.d.). bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/media/2034/daleswaylinkbradfordilkley.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 27: Approaching Shipley Railway Station (n.d.). bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/media/2034/daleswaylinkbradfordilkley.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 28: View across the valley of Manningham Mills and Lister Park (n.d.). bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/media/2034/daleswaylinkbradfordilkley.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 29: Old gate stoop on the hillside above Poplars Park Road. (n.d.). bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/media/2034/daleswaylinkbradfordilkley.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 31: The Dalesway Link Bradford - Ilkley. (n.d.). bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/media/2034/daleswaylinkbradfordilkley.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 32: Policies Map of Bradford City Centre. (2017). Bradford City Centre Area Action Plan. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/Documents/CityCentreActionPlan/Adoption//01.%20Adopted%20Brad ford%20City%20Centre%20AAP%202017.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 33: Bradford Canal Road Corridor Master Plan. (n.d.). Bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/Documents/ShipleyActionPlan/2%20Submission%20to%20the%20Secret ary%20of%20State/1%20Submission%20documents//SCRC%20SD%20001%20SCRC%20AAP%20Publica tion%20Draft,%20December%202015.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Figure 33: Green Infrastructure Framework concept plan. (n.d.). Bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/Documents/ShipleyActionPlan/2%20Submission%20to%20the%20Secret ary%20of%20State/1%20Submission%20documents//SCRC%20SD%20001%20SCRC%20AAP%20Publica tion%20Draft,%20December%202015.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

64

REFERENCES

• Bradford Canal Road Masterplan. (2006). [online] bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/Documents/ShipleyActionPlan/2%20Submission%20to%20the%20Sec retary%20of%20State/2%20Other%20relevant%20supporting%20documents/SCRC%20SD%20043%2 0Bradford%20Canal%20Road%20Masterplan%20August%202006.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Bradford Centre Regenration Masterplan. (2003). [online] bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://bradford.gov.uk/Documents/CityCentreActionPlan/3%20Submission%20to%20the%20Secre tary%20of%20State/1%20Submission%20documents//BCC-SD043%20Bradford%20City%20Centre%20Masterplan.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023]

• bradford-beck.org. (n.d.). bradford-beck.org. [online] Available at: https://bradford-beck.org/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• bradford-beck.org. (2017). History of Bradford. [online] Available at: https://bradfordbeck.org/history/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Core Strategy Development Plan Document . (2017). [online] bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/Documents/planningStrategy/10/Adopted%20core%20strategy/1% 20Core%20Strategy%20full%20document.pdf [Accessed 11 Sep. 2023].

• Extention Notes. (n.d.). [online] lrconline.com. Available at: http://www.lrconline.com/Extension_Notes_English/pdf/Naturalize.pdf [Accessed 13 Sep. 2023].

• Hidrología Sostenible. (2013). Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems – SUDS. [online] Available at: http://www.hidrologiasostenible.com/sustainable-urban-drainage-systems-suds/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Land8.com. (2016). What Makes Roombeek The Brook a Remarkable Urban Street? [online] Available at: https://land8.com/what-makes-roombeek-the-brook-a-remarkable-urban-street/ [Accessed 25 Sep. 2023].

• Lerner, B. (2017). The Bradford Beck. The Bradford Antiquary, [online] 78, pp.88–100. Available at: https://bradfordbeckdotorg.files.wordpress.com/2021/07/beck-history-fobb-final.pdf [Accessed 9 Sep. 2023].

• Ny.gov. (2019). Shoreline Stabilization Techniques - NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation. [online] Available at: https://www.dec.ny.gov/permits/67096.html [Accessed 11 Sep. 2023].

• Shipley and Canal Road Corridor Area Action Plan. (2015). [online] bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/Documents/ShipleyActionPlan/2%20Submission%20to%20the%2 0Secretary%20of%20State/1%20Submission%20documents//SCRC%20SD%20001%20SCRC%20 AAP%20Publication%20Draft,%20December%202015.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Skinner, E., Price, L. and Masheder, R. (2014). [online] bradford.gov.uk. West Yorkshire Ecology

: City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council . Available at: https://www.bradford.gov.uk/documents/citycentreactionplan/2%20publication%20draft/evi dence%20base/ecological%20assessment.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• tudioegretwest.com. (n.d.). Mayfield Park. [online] Available at: https://studioegretwest.com/places/mayfield-park [Accessed 11 Sep. 2023].

• Susdrain (2019). Sustainable drainage. [online] Susdrain.org. Available at: https://www.susdrain.org/delivering-suds/using-suds/background/sustainable-drainage.html [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Walks Around Bradford’s Becks . (n.d.). [online] bradford.gov.uk. Available at: https://bradfordbeckdotorg.files.wordpress.com/2021/06/bradford-beck-walks.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Wanders, D. (2021). What Is Naturalized Landscape Design? | The Raymar Blog. [online] Raymar Landscaping. Available at: https://raymarlandscapes.com/blog/what-is-naturalizedlandscape-design [Accessed 11 Sep. 2023].

• Waterman Transport & Development Limited (2012). Bradford Beck River Restoration. [online] Available at: https://bradfordbeckdotorg.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/bradford-beckrestoration-appendix.pdf [Accessed 9 Sep. 2023].

• Wikipedia. (2023). Bradford Canal. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bradford_Canal [Accessed 8 Sep. 2023].

• www.bradfordtimeline.co.uk. (n.d.). Bradford Timeline - History of Bradford, Yorkshire - 1066 to 1699. [online] Available at: https://www.bradfordtimeline.co.uk/160099.htm [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

• Polster, David F. "Soil bioengineering for slope stabilization and site restoration." Mining and the Environment 3 (2003): 25-28. Available at: https:// https://pdf.library.laurentian.ca/medb/conf/Sudbury03/Amendments/122.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep. 2023].

65

THE STUDY AREA

THE STUDY AREA

CANAL ROAD

Canal road, Bradford Canal road, Shipley

Canal road forms the eastern site boundary

CANAL ROAD

Canal road, Bradford Canal road, Shipley

Canal road forms the eastern site boundary

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

BRADFORD CATHEDRAL

THE BROADWAY

WHITE ABBEY RESIDENTIAL

FOSTER SQUARE STATION

RETAIL PARK AND WAREHOUSE DISTRICT

BRADFORD CENTRAL MOSQUE BRADFORD INTERCHANGE

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

BRADFORD CATHEDRAL

THE BROADWAY

WHITE ABBEY RESIDENTIAL

FOSTER SQUARE STATION

RETAIL PARK AND WAREHOUSE DISTRICT

BRADFORD CENTRAL MOSQUE BRADFORD INTERCHANGE

PEEL PARK RESIDENTIAL

Access from Hamm Stasse Road

The railway separates the site

Cycle Network routes on Valley Road

Access from Hamm Stasse Road

The railway separates the site

Cycle Network routes on Valley Road

of the River Aire

of the River Aire