OLD IRELAND IN COLOUR 3

First published in 2023 by Merrion Press

10 George’s Street

Newbridge Co. Kildare Ireland

www.merrionpress.ie

© John Breslin & Sarah-Anne Buckley, 2023

9781785374715 (Hardback)

9781785374722 (Ebook)

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro, Garamond and Avenir.

Cover design by: riverdesignbooks.com

Opening credits:

PAISLEY SHAWL; October 1863, Shinrone, Co. O aly. is is an image of Miss Jinney/Jane Burton. She died in 1865 aged 83; she was 81 when this photograph was taken. Her brother, Robert ‘Bob’ Burton, died in 1875 aged 86. Both lived longer than the average life expectancy. Photographer: William Cripps Ledger; Source: the Breslin Archive; Ref.: 00TBCBWP-LEDGE001-D.

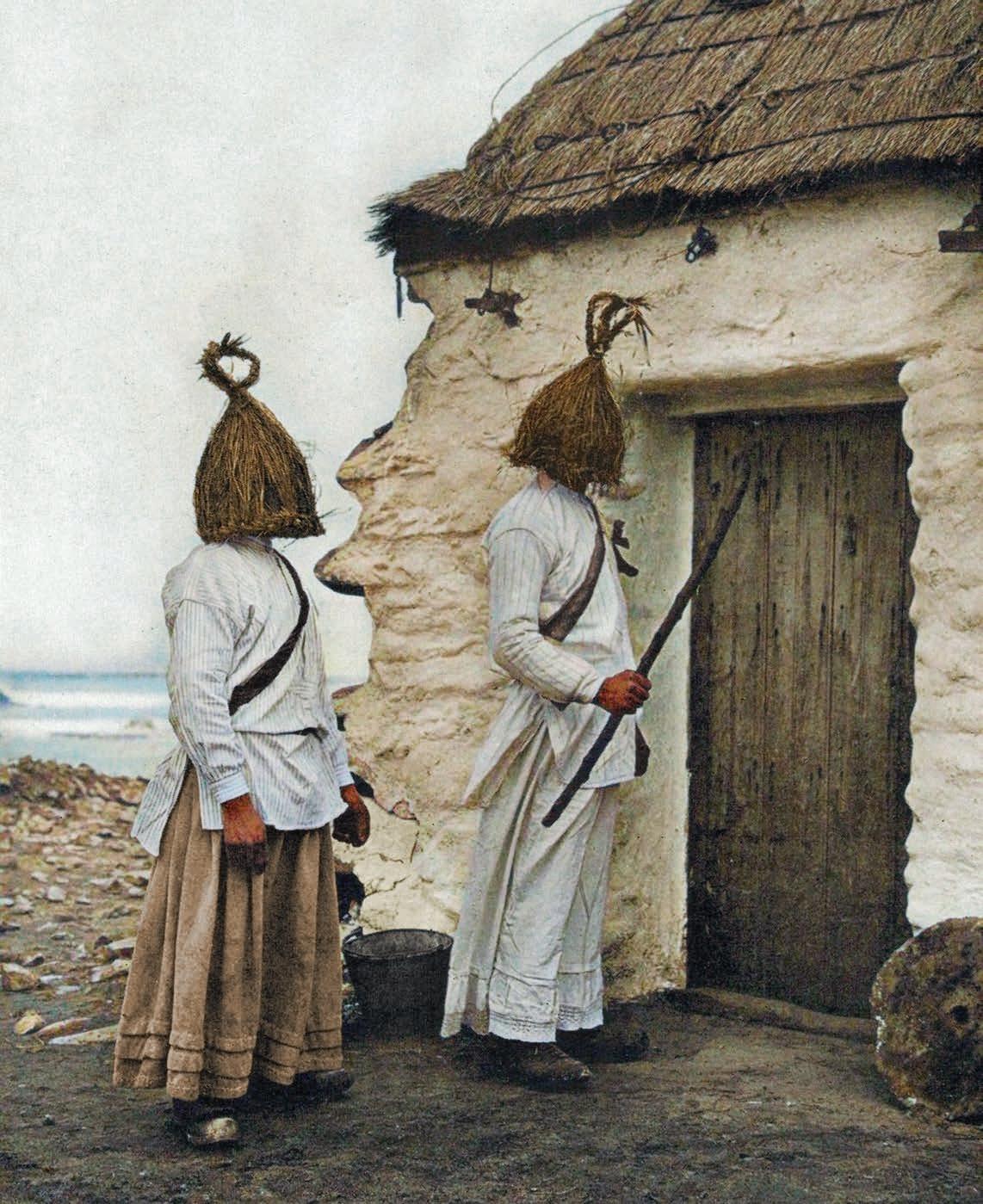

STRAW BOYS; c.1922. Straw boys were uninvited guests disguised in straw costumes with conical straw hats over their faces, who visited weddings to dance with the bride and other women. eir presence was believed to bring luck, wealth and health to the newlyweds. e tradition has mostly died out, but there are still areas in Munster where parts of the tradition continue. Photographer: Alfred William Cutler; Source: the Breslin Archive.

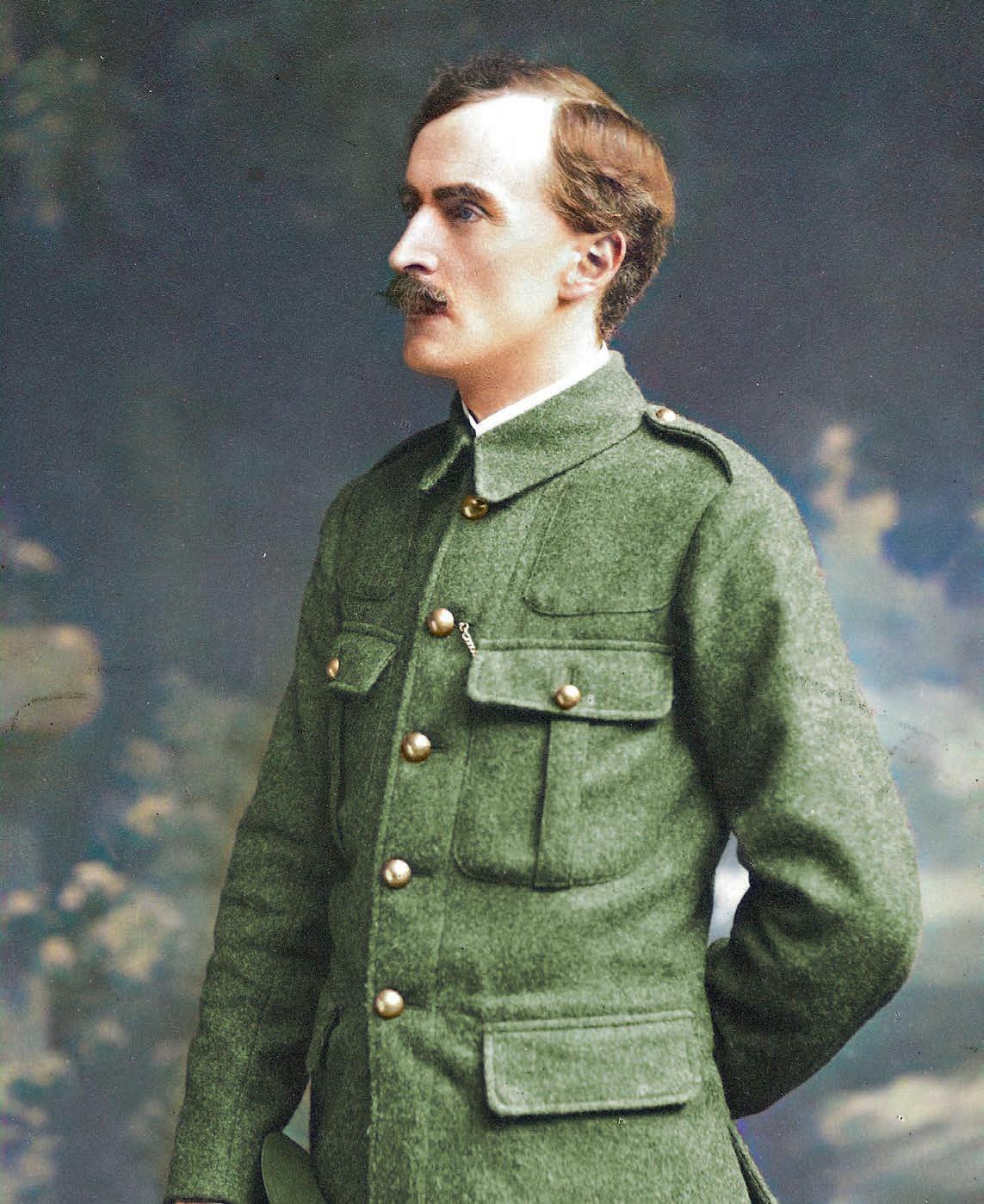

KEVIN BARRY (1902–1920); c.1917, Dublin. Kevin Barry in his Belvedere College rugby jersey, taken three years prior to his execution in Mountjoy Prison on 1 November 1920. Barry was court-martialled and executed for the murder of three British soldiers under the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, 1920. Born in 1902 in Fleet Street, Dublin, he joined the Irish Volunteers while at Belvedere. His youth, the way in which he was tried and executed, and a concerted republican campaign made Barry an immediate martyr. Remembered in numerous ballads, the infamous ‘Kevin Barry’, cites his ‘fair blue eyes’, prominent in this depiction. Photographer: Keogh Brothers Ltd; Source: National Library of Ireland; Ref.: KE 7.

‘THREE GENERATIONS OF CONNEMARA’; c.1926, Co. Galway. is shows a traditional cottage with a thatched roof held down by a net of grass ropes called súgáin, weighted at the ends with rocks. Photographer: Clifton Royal Adams; Source: the Breslin Archive.

Front cover image: HARVEST SCENE; 1947, Wilton, Cork. Photographer: Unknown; Source: Irish Examiner; Ref.: 321D.

Back cover image: ATHLONE TOWN CENTRE; Photographer: Robert French; Source: National Library of Ireland; Ref.: L_ROY_11610.

Back page image: WINTER KILLS; 10 December 1870, Clonbrock House, Ahascragh, Co. Galway. A man with a double-barrel shotgun on the grounds of the Clonbrock Estate, perhaps a gamekeeper or member of the Dillon family. Photographer: Dillon Family; Source: National Library of Ireland; Ref.: CLON2034.

ADA REHAN (1860–1916); 1897, USA. Rehan was one of Ireland’s most celebrated actresses. Born in Limerick, she grew up in Brooklyn. A Times critic wrote, ‘when Ada Rehan was in her prime, she was without a rival in her province on the comic stage’. Photographer: Aime Dupont; Source: Library of Congress; Ref.: 2002718779.

O’MAHONY’S BOOKSHOP; c.1902, George’s (now O’Connell) Street, Limerick. O’Mahony’s was founded in 1902 at 120 O’Connell Street by J.P. O’Mahony. It continues to trade from the same location and is the oldest retail family business of its type in the region. Photographer: Robert French; Source: National Library of Ireland; Ref:. L_CAB_00934.

Merrion Press is a member of Publishing Ireland

Old Ireland in Colour has been one of the most rewarding and engaging projects we have both been involved with. We would like to start by thanking everyone for their support, for contacting us and telling us about your experiences, your families’ experiences, and your love for the project. Your enthusiasm and knowledge have driven this project, and it is the reason we have created this third book.

Everyone at Merrion Press has encouraged this book, and us, from the very beginning. To Conor, Pa, Wendy, Maeve, our publicist Peter and our cover designer Latte, a huge thank you for your work. Wendy, you have been particularly critical to this book – thank you from both of us.

As we have said many times before, this book could not exist without the work and generosity of those in our libraries, archives and museums. ank you for allowing us to highlight and access these collections. ank you in particular to the National Library of Ireland and the Flickr team and volunteers for your contributions to all our knowledge. We hope this volume re ects the breadth and diversity of our local, national and global works.

Finally, we want to thank our families and friends for all their support. We hope you enjoy this volume as much as we enjoyed working on it.

Prof. John Breslin is a Personal Professor in Electronic Engineering at the University of Galway, where he is co-PI at the Insight SFI Research Centre for Data Analytics. He is a co-founder of boards.ie, adverts.ie and the PorterShed (Galway City Innovation District). From Fanore in the Burren, he lives between Moycullen and Oughterard in Connemara.

Dr Sarah-Anne Buckley is Associate Professor in History at the University of Galway. Chair of the Irish History Students’ Association, co-PI of the Tuam Oral History Project and past President of the Women’s History Association of Ireland, she has authored/edited ten books. From Cobh, she lives in Galway.

Follow Old Ireland in Colour at @oldirelandincolour on Facebook, Instagram, reads and YouTube, at @irelandincolour on Twitter, or visit www.oldirelandincolour.com.

e third volume of the Old Ireland in Colour project has been in some ways the most challenging to curate. e rst books in this series have received such a warm response, we wanted to ensure that we built on this and continued to re ect the diverse experience of people living in Ireland and the Irish diaspora in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. We have chosen again to look at broad thematic areas – Politics, Childhood, Working, Social, Global and Place – and arrange the sections largely chronologically. While there is still a focus on Ireland’s photographic collections, we have included even more ‘unseen’ images from John’s ‘Breslin Archive’, as well as a collection of the earliest colour photographs taken in Ireland by Clifton Royal Adams. It is a diverse and colourful collection, re ecting life and how it transformed for many people over a 115-year period (1844–1969).

Within the pages of this book, the reader will nd familiar places and individuals, such as e O’Rahilly, Margaret Skinnider and Daniel O’Connell, but also lesser-known individuals whose impacts have only more recently been highlighted, and places that have changed almost beyond recognition. ere is also the beautifully ordinary – the clothes, the houses, the transport and the scenery. As you explore you will see vibrant shawls, strawboys, thatched roofs on whitewashed houses, barefoot children. e land and place are key – be it rural, town or city – to how people lived, worked, travelled, ate or took time for leisure. ere are individuals we perhaps know less about, like Doug ‘Wrong Way’ Corrigan or Patrick O’Connell, ‘the saviour of Barcelona FC’, and portrayals of poverty and destruction. e captions are lled with stories of life, love and loss, determined by social class, gender, geography, age, ethnicity, marital status, education, work and family structure. Expectations and choices are clear, around migration, war and love. e Irish diaspora re ects this, with some fascinating characters emerging, such as the ‘Queen of Paraguay’ and the ‘Angel of the Cassiar’.

e 161 images in this book address a key period from the Great Famine to the late 1960s. As with our earlier books, this volume does not claim to be a history of photography or a comprehensive history of modern Ireland. Re ecting the nature of the source materials, it is a snapshot of Ireland’s political, social, economic and cultural life, with many known and unknown faces. It is the story of how we worked, laughed, and played, how we loved, how we lived. Change and transformation – whether scienti c, religious, political, or labour- or work-related – remain key tenets, and with each image we can view our past and those who lived in it with empathy and humanity. ey re ect changes over the period in housing and dress, and the importance of leisure activities and religion, the growth in schooling, and developments in gender roles. e rare or unseen images, in particular, give us a poignant glimpse of life across the class spectrum.

In the captions, we have tried to give a clear overview of the subject of each image, but also to spark an interest that may lead the reader to look further. We have relied upon excellent open and available sources like the Dictionary of Irish Biography, and other key references are contained near the end of the book. As with the rst volume, we have used recorded evidence of eye and hair colour where available, be it from newspaper accounts, prison records, family portraits or contemporary

accounts. Kevin Barry, Ada Rehan, Maud Gonne, Muriel Gi ord are just a few of the examples where this was possible. Travel records, paintings and relatives have also provided so many details. Traditions old and new have been recorded in folklore – and the work of scholars and enthusiasts has been invaluable and is acknowledged. e moments recorded have a much more vivid visual impact in these colourised images.

One of the interesting aspects of this project has been the portrayal of the colourisation process as a ‘new’ process. Yet as photographers and those who study photography know, from the very earliest images up to more recent times photographs have been colourised. Tints have been added and the colours of the sky have been (re)made blue. Examples can be traced back to as early as 1841, when one of the earliest photographers, the Swiss painter and lithographer Johann Baptist Isenring, began to use dyed powders, gum and ne brushes to colourise daguerreotypes, using a heat- xing technique he went on to patent in the USA. From the 1860s onwards in Japan, photographers, such as the Italian-British Felice Beato, the Italian Adolfo Farsari and the Japanese Yokoyama Matsusaburō, were creating hand-colourised photographs of samurai, temples, and scenes of everyday life at that time, which soon became popular in the tourism industry and in uenced colourisers around the world. Hand-colourised family photographs quickly became a status symbol in the West, and many photographic studios began to o er a colourisation option to their customers. Colourised photographs also enabled middle-class and working-class families to have an equivalent of the painted portraits that up to that point had been solely the provenance of the social and economic elite. e rst commercial colour photography process was the autochrome from the Lumiére brothers in 1907, although black-and-white photography endured well into the 1960s, after which colour photography became more commonly used by amateurs. rough the colourisation of almost six score years of photographic history, we still view the Old Ireland in Colour project as part of the democratisation of history, a tool to develop empathy and a connection with the past while the original photograph remains intact.

For this third volume, we have used some existing deep-learning systems and manual colourisation techniques, but also some new ones, in a hybrid computer–human colourisation methodology to produce what we believe is a better set of photographic colourisations. We put extensive and painstaking work into researching everything, and taking the deep-learning colourised image as a base layer (from colourisation systems such as DeOldify, ColorizeImages, Palette and Photoshop), we carry out extensive manual colourisation of the researched items in Photoshop: personal details from any available records (newspaper accounts, biographies, paintings, travel records such as people going through Ellis Island, passport and naturalisation applications from the USA, information provided by relatives, etc.); clothes and types of clothes that someone or some group wore (using any available records such as newspaper accounts, interviews and general sources on clothing

in di erent eras such as Dress in Ireland by Mairéad Dunlevy); uniforms (consulting with war uniform specialists in Ireland and the UK and published secondary work); traditions (e.g., folklore and stories around colours used, dyes and sources of these dyes, paintings or sketches captured of various styles, historical and museum-held artefacts and clothing from various regions); searching for copies of old advertisements, brands, products, posters, signs and paintings in the background; material culture research; and much, much more. is process can take hours in Photoshop (for a simple image), days or sometimes even weeks. We ensure that we are as accurate as possible from a historical perspective.

For the rst time in this series, we include a small number of early autochromes taken in Ireland during the mid-1920s by Clifton Royal Adams (1890–1934). e autochrome was an early colour photography process, and therefore these photographs (which appear on pages 8, 88–89, 112, 114, 156, 157, 250, 253, 254, 258–259) have not been colourised, but rather have been restored and enhanced by us using digital means.

John Breslin & Sarah-Anne Buckley

John Breslin & Sarah-Anne Buckley

Michael Joseph O’Rahilly (1875–1916) was an Irish republican and founding member of the Irish Volunteers in 1913, where he served as Director of Arms. Born and educated in Ballylongford and Clongowes Wood College, he started to study medicine at University College Dublin, but his studies were disturbed by tuberculosis and he later left to run the family business following his father’s death. e business was sold after O’Rahilly married an IrishAmerican, Nancy Brown, in 1899. e couple would go on to have six children. O’Rahilly wrote extensively for Gri th’s short-lived daily Sinn Féin (1909–10) and joined the Sinn Féin party executive in October 1910. In 1913, he revamped the loss-making Gaelic League paper, An Claidheamh Soluis. roughout this time, he wrote under the pen name ‘ e O’Rahilly’. On ursday, 27 April 1916, during the evacuation of the GPO, he was fatally wounded charging a British barricade in Moore Street. He bled to death slowly in a doorway in Moore Lane (latterly O’Rahilly Place), crying for water and writing his name in blood on a wall, nally dying the next day. e ballad

‘ e O’Rahilly’ by W.B. Yeats celebrates him as an exemplar of existential heroism.

1844, Richmond Bridewell Prison, Dublin

A rare daguerreotype and the sole surviving photograph of Daniel O’Connell (1775–1847), in which he is wearing his famous ‘Repeal Cap’. e cap was of green velvet and embroidered with golden shamrocks; it was designed by artist Henry McManus and presented to O’Connell by sculptor John Hogan. Known as ‘ e Liberator’, O’Connell was a barrister, politician and nationalist leader, born in Carhen, near Caherciveen. After studying law, in 1823 O’Connell, along with Richard Lalor Sheil, founded the Catholic Association to campaign for Catholic Emancipation. He won his rst election in Co. Clare in 1828, but could not sit in Westminster until after Emancipation in 1829. To push for repeal of the Union, in 1840 O’Connell established the Loyal National Repeal Association, and in 1841 he became the rst Catholic lord mayor of Dublin. After speaking at a series of ‘monster meetings’ in favour of repeal, he was jailed in June 1844 on charges of seditious conspiracy but released on appeal three months later. A ‘champion of civil and religious liberty and equality’, he received some criticism from other nationalists for his opposition to physical force and his lack of support for the Irish language. However, his reputation and legacy as one of Ireland’s foremost nationalist politicians remains undisputed.

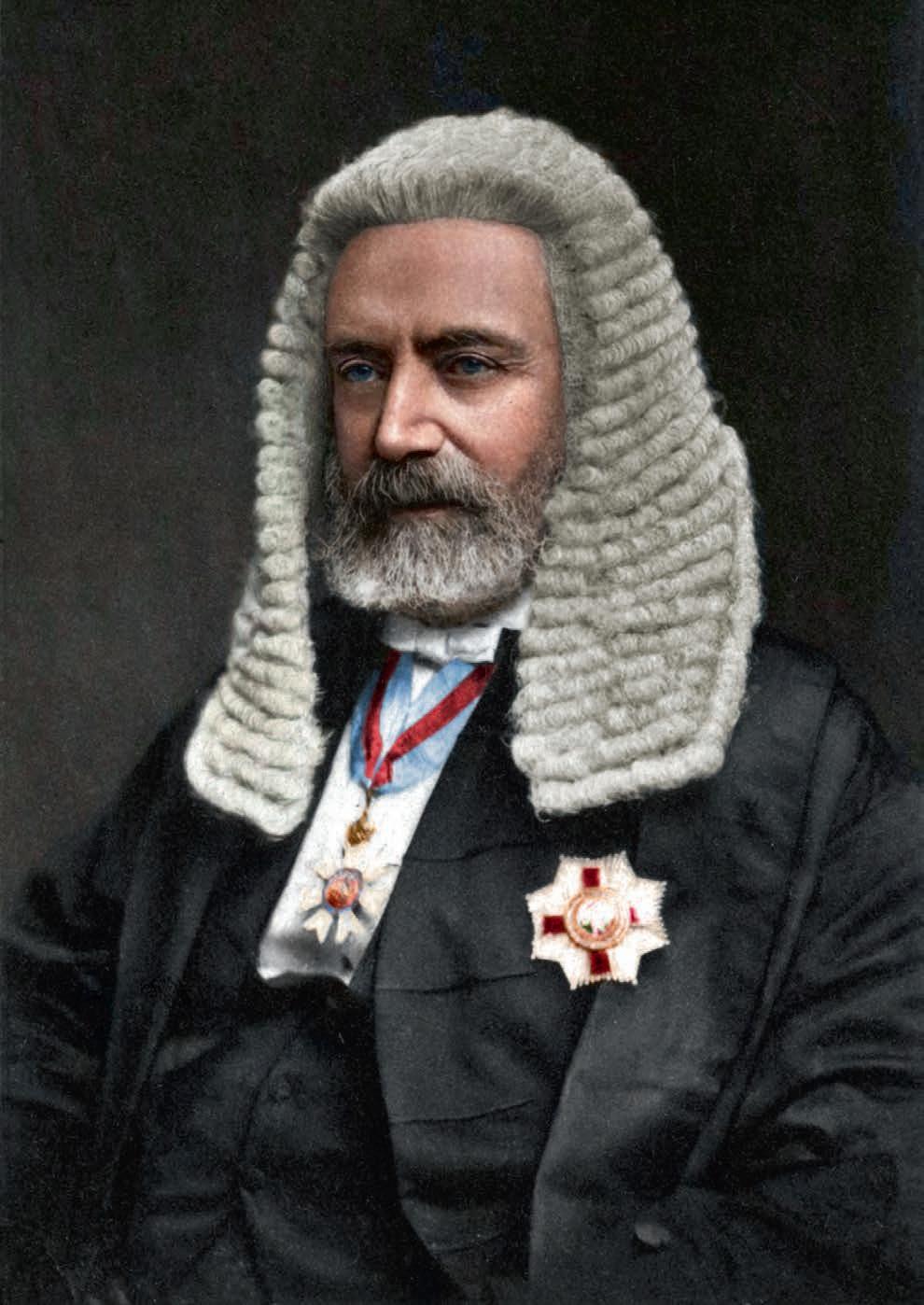

1844, Richmond Bridewell Prison, Dublin, and 1880, Australia

On the left is a daguerreotype of Young Irelander Charles Gavan Du y (1816–1903). On the right is Sir Charles Gavan Du y as Speaker of the Victorian Legislative Assembly, wearing his Order of St Michael and St George Star and Badge. A journalist, politician and writer, Du y was born in Monaghan town, the sixth and youngest child of John Du y, a shopkeeper and former United Irishman, and his wife, Anne. His parents and three older brothers died prematurely, and he was raised by the local parish priest. As a journalist, Du y became founding editor of the Belfast Vindicator, which he later bought and sold, before publishing e Nation. After Daniel O’Connell called o the Clontarf ‘monster meeting’ in October 1843, Du y was one of the ‘traversers’ arrested with him for seditious conspiracy. In the 1852 general election, Du y was elected MP for New Ross, but he became increasingly disillusioned with politics in Ireland. He moved to Australia to practise law but was again caught up in politics and was brie y Premier of Victoria. In 1880, he left Australia for France, and in later life published a series of books on Irish history, including My Life in Two Hemispheres, which incorporated his own history. He died in Nice in 1903 and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin.