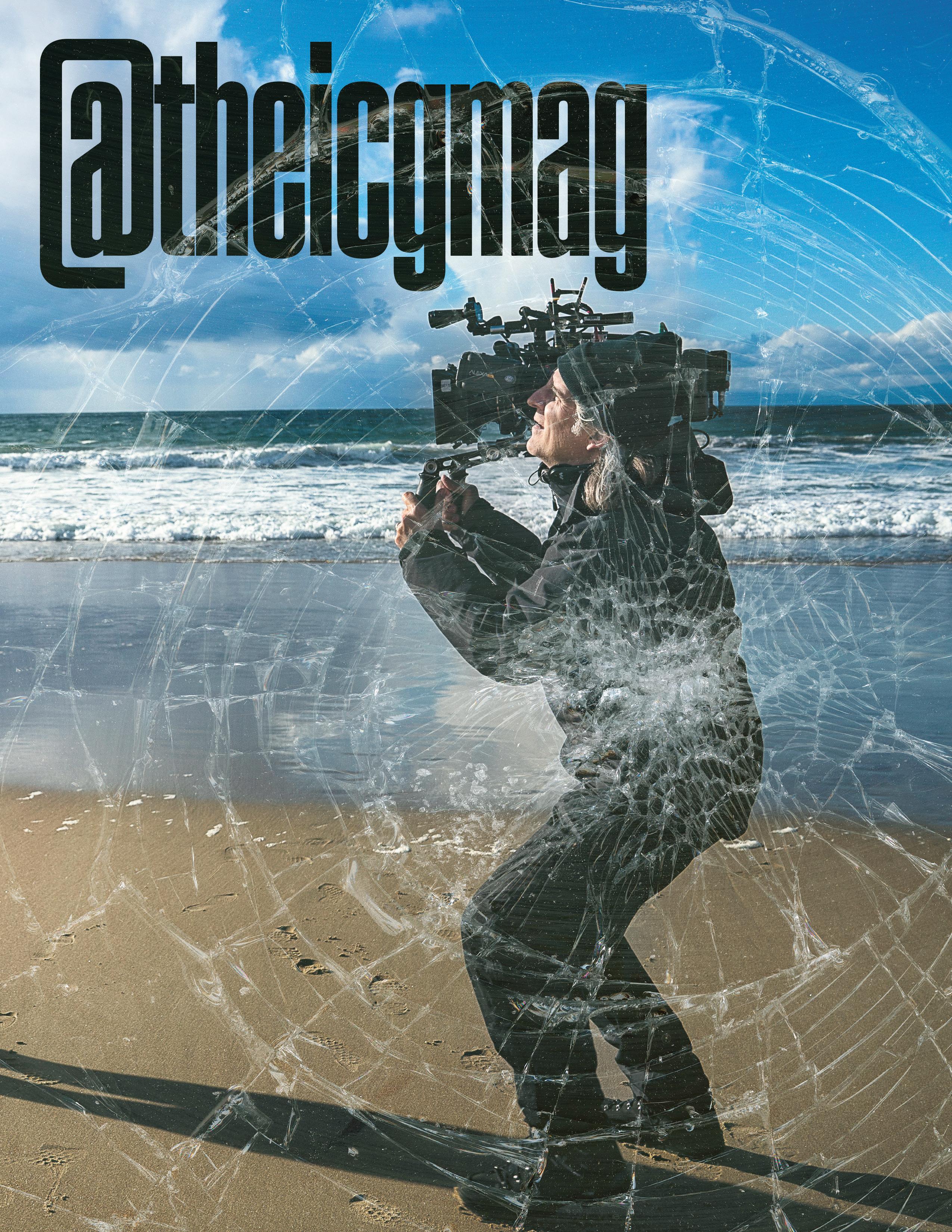

ICG MAGAZINE

STAR TREK: PICARD + UP HERE + TINY BEAUTIFUL THINGS

4 APRIL 2023 THE FINAL FRONTIER FEATURE 01 Crescenzo Notarile, ASC, AIC, and Jon Joffin, ASC, chart a visual journey beyond Federation borders for Star Trek: Picard 26 SPECIAL Sundance 2023 .... 74 NEW TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENTS gear guide ................ 12 refraction ................ 16 on the street ................ 20 exposure ................ 22 production credits ................ 104 stop motion .............. 110 April 2023 / Vol. 94 No. 03

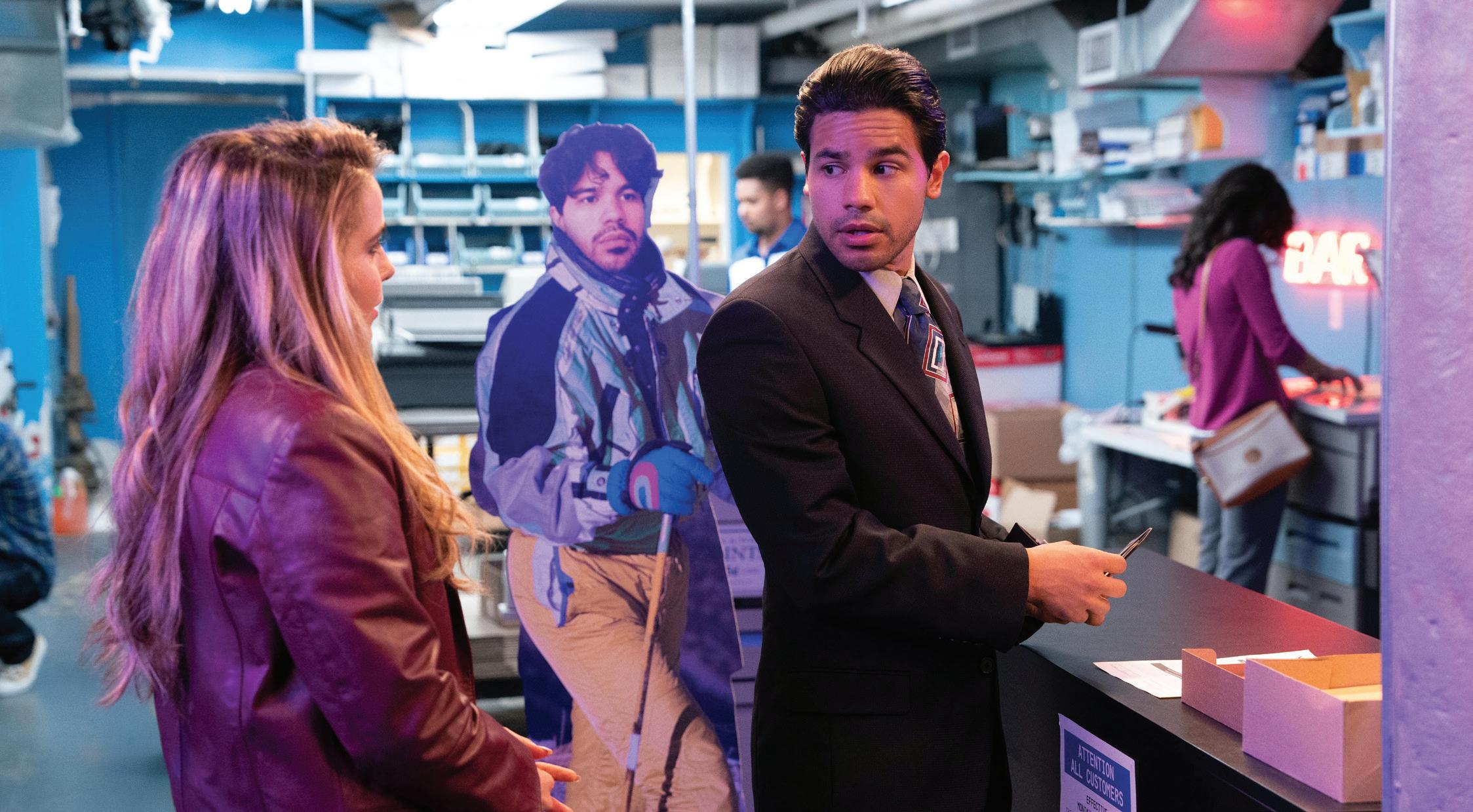

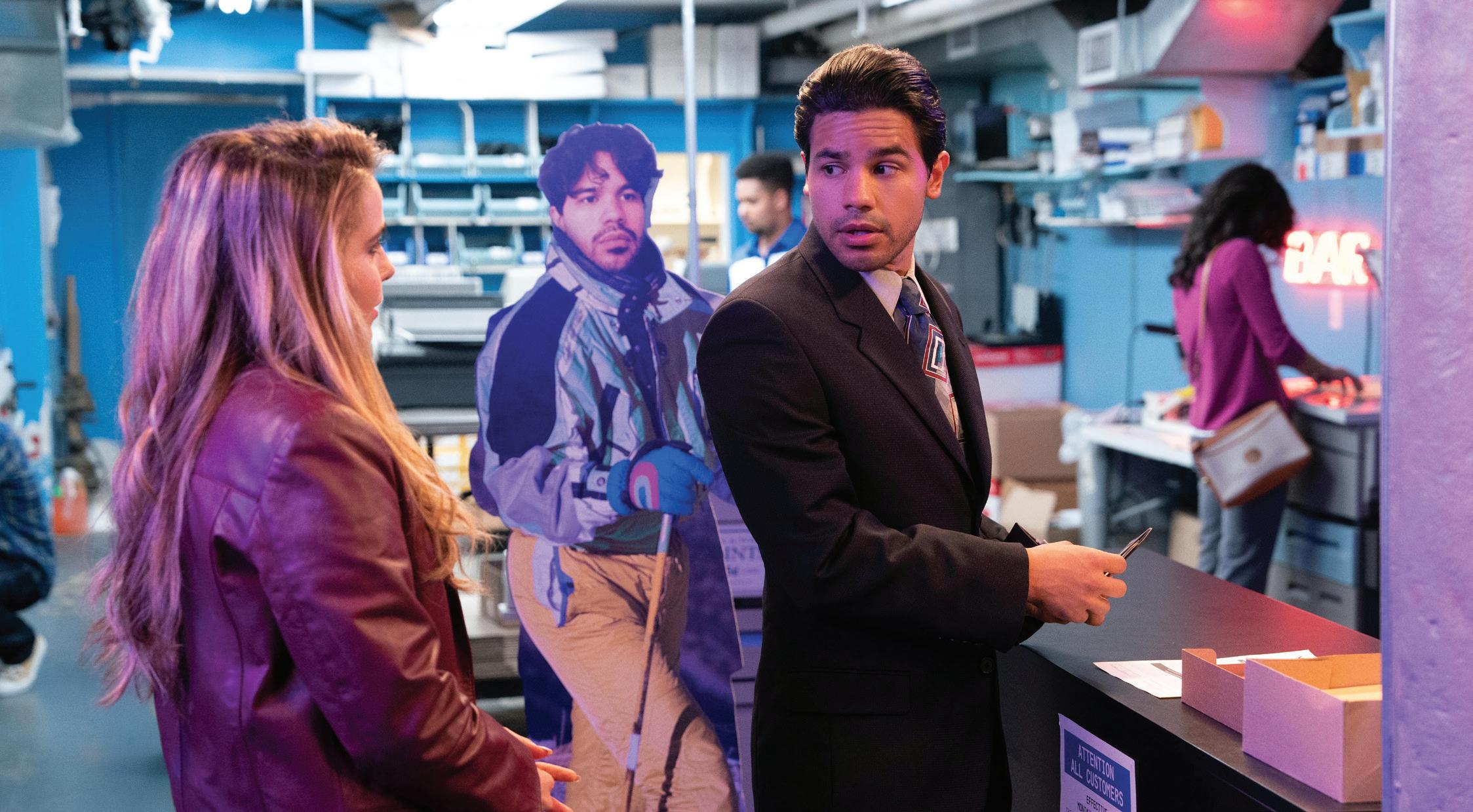

Tiny Beautiful Things FEATURE 03 FAMILY TREE Director

Ashley Connor listens to her “inner creative voice” for Hulu’s new musical series, Up Here FEATURE 02 44 60 ONE FROM THE HEART CONTENTS

Tobias

Datum joins an all-women team to bring forth Hulu’s emotionally complex new

limited series,

of Photography

Industry-leading image quality in a lightweight, go-anywhere package.

Embraced by award-winning filmmakers and owner-operators taking their careers to the next level, the ALEXA Mini LF is ARRI’s flagship large-format camera. Versatile and adaptable due to its compact size, low weight, and multiple recording formats, the Mini LF offers unsurpassed large-format image quality, continually improving ARRI accessories, software updates, and an exciting new REVEAL Color Science post workflow.

www.arri.com/alexa-mini-lf

PRESIDENT’S LETTER

Creativity Central

This month’s issue of ICG Magazine , centered around new technology, doesn’t only highlight the amazing new gear used on high-end visual effects movies and television series, as one might think. It’s also a platform for those tech innovators in this membership – DP’s, operators, assistants, DIT’s and others who take their skills from the set to the workbench, and sometimes the launching pad of a new business. Our Local 600 members have showcased gear, apps, and other products they’ve invented at key industry trade shows –like this recent February at HPA, in Palm Desert, CA, or in a few weeks from now at NAB in Las Vegas, and this June, at Cine Gear, here in Los Angeles. It’s incredible to see how this membership continues to innovate in their respective crafts. If they see a way to do something more efficiently on set; if they see something missing in the technology chain of their own workflows; or if they just imagine a way to get their job (and the jobs of other crafts) done more safely, they go and create something to make our industry better, stronger, and more productive. I’ve seen several examples in my career – from the camera to the grip department – of union film workers finding interesting technological solutions to problems they’ve encountered on sets or locations. And while I’m the first to admit I’m not aware of all the new technologies coming at us (on an almost daily basis), I can say I’m honored to be part of a union whose members take such pride in creating some of the new technologies ICG readers will learn about in this April issue – and all year round.

6 APRIL 2023

Baird B Steptoe

Photo by Scott Everett White

National President International Cinematographers Guild IATSE Local 600

Lights, Camera, Action, Logistics!

Masterpiece’s Entertainment Division understands the complex logistics of the industry including seemingly impossible deadlines, unconventional expedited routings, and show personnel that must be on hand. Masterpiece has the depth of resources to assist you in making sure everything comes together in time, every time.

Contact us to find out how our experienced team can securely and efficiently handle transporting to remote locations, made possible through our network of agents and partners around the globe. We have high-level access to restricted areas in all major international airports to oversee freight handling to make sure your precious cargo is always safe.

Our range of services, include:

• Performing Arts Industry Expertise

• Customs Brokers

• Freight Forwarders

• ATA Carnet Prep & Delivery

• Border Crossings

• Domestic Truck Transport

• International Transport via Air or Ocean

• Expedited Shipping Services

• 24/7 Service Available

FESTIVALS BALLET SPORTING STAGE

FILM & TV

ENTERTAINMENT LOGISTICS EXPERTS LEARN MORE www.masterpieceintl.com

Publisher

Teresa Muñoz

Executive Editor

David Geffner

Art Director

Wes Driver

STAFF WRITER

Pauline Rogers

COMMUNICATIONS COORDINATOR

Tyler Bourdeau

COPY EDITORS

Peter Bonilla

Maureen Kingsley CONTRIBUTORS

Michael Chambliss

Dennys Ilic

Kevin Martin

Valentina Valentini

April 2023 vol. 94 no. 03

IATSE Local 600

NATIONAL PRESIDENT

Baird B Steptoe

VICE PRESIDENT

Chris Silano

1ST NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Deborah Lipman

2ND NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Mark H. Weingartner

NATIONAL SECRETARY-TREASURER

Stephen Wong

NATIONAL ASSISTANT SECRETARY-TREASURER

Patrick Quinn

NATIONAL SERGEANT-AT-ARMS

Betsy Peoples

INTERIM NATIONAL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Chaim Kantor

COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE

John Lindley, ASC, Co-Chair

Chris Silano, Co-Chair

CIRCULATION OFFICE

7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, CA 90046

Tel: (323) 876-0160

Fax: (323) 878-1180

Email: circulation@icgmagazine.com

ADVERTISING REPRESENTATIVES

WEST COAST & CANADA

Rombeau, Inc.

Sharon Rombeau

Tel: (818) 762 – 6020

Fax: (818) 760 – 0860

Email: sharonrombeau@gmail.com

EAST COAST, EUROPE, & ASIA

Alan Braden, Inc.

Alan Braden

Tel: (818) 850-9398

Email: alanbradenmedia@gmail.com

Instagram/Twitter/Facebook:

@theicgmag

ADVERTISING POLICY: Readers should not assume that any products or services advertised in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine are endorsed by the International Cinematographers Guild. Although the Editorial staff adheres to standard industry practices in requiring advertisers to be “truthful and forthright,” there has been no extensive screening process by either International Cinematographers Guild Magazine or the International Cinematographers Guild.

EDITORIAL POLICY: The International Cinematographers Guild neither implicitly nor explicitly endorses opinions or political statements expressed in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. ICG Magazine considers unsolicited material via email only, provided all submissions are within current Contributor Guideline standards. All published material is subject to editing for length, style and content, with inclusion at the discretion of the Executive Editor and Art Director. Local 600, International Cinematographers Guild, retains all ancillary and expressed rights of content and photos published in ICG Magazine and icgmagazine.com, subject to any negotiated prior arrangement. ICG Magazine regrets that it cannot publish letters to the editor. ICG (ISSN 1527-6007)

Ten issues published annually by The International Cinematographers Guild 7755 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, CA, 90046, U.S.A. Periodical postage paid at Los Angeles, California.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ICG 7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, California 90046

Copyright 2021, by Local 600, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States and Canada. Entered as Periodical matter, September 30, 1930, at the Post Office at Los Angeles, California, under the act of March 3, 1879. Subscriptions: $88.00 of each International Cinematographers Guild member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. Non-members may purchase an annual subscription for $48.00 (U.S.), $82.00 (Foreign and Canada) surface mail and $117.00 air mail per year. Single Copy: $4.95

The International Cinematographers Guild Magazine has been published monthly since 1929. International Cinematographers Guild Magazine is a registered trademark.

www.icgmagazine.com www.icg600.com

It was great to return in person this past February to the Hollywood Professionals Association (HPA) conference with my colleague, ICG Business Representative, and technology expert Michael Chambliss. Unlike much larger industry gatherings, HPA is an intimate affair, where roughly one thousand attendees – technological thought leaders from around the world – cluster at a Palm Desert, CA hotel for a flurry of presentations that, this year, ranged from an all-day seminar on the herculean tech efforts it took to create Avatar: The Way of Water (in the darkest days of COVID) to whether the entertainment industry should put all its chips (aka assets) into the cloud. HPA is also a bitesized trade show, where vendors gather in a separate hall known as the “Innovation Zone” to show off their latest products. (This year’s offerings were mainly centered on workflow and postproduction tools.)

There’s always plenty of brain power percolating at HPA, and this year’s conference was especially stimulating, with stakeholders from Sony Pictures Entertainment and The Walt Disney Company to Amazon, AVID and Zeiss. I’ll be posting a story from our visit to HPA later this month on icgmagazine.com, but I did want to highlight one HPA story running in this month’s On The Street (page 20).

Local 600 DIT Ryan Prouty has been in the film/TV/broadcast trenches for almost two decades, and he’s picked up a thing or two about production efficiency (or the lack thereof). When we met Prouty outside HPA’s Innovation Zone, he was demoing two companies he’s created – COLORSPACE [colorspacevan.com] and CinemaScan [www. cinemascan.la] – both aimed at increasing efficiency (and thus giving more time toward the creative process) on set. CinemaScan is particularly interesting to IATSE crafts workers as it combines panoramic photography and game-engine technology to create a video of a location before IATSE crews show up for work. CinemaScan provides a detailed “fly-over” and “walk-through” for basic quality-of-work issues (such as where are the bathrooms? Where is crafty staged? Where can we park our G&E truck to run the shortest amount of cabling to the set?). As Prouty told me: “Both

COLORSPACE and CinemaScan were inspired by my years spent on sets around the world: the guiding force is what technology can do for humans when it’s designed with intention.”

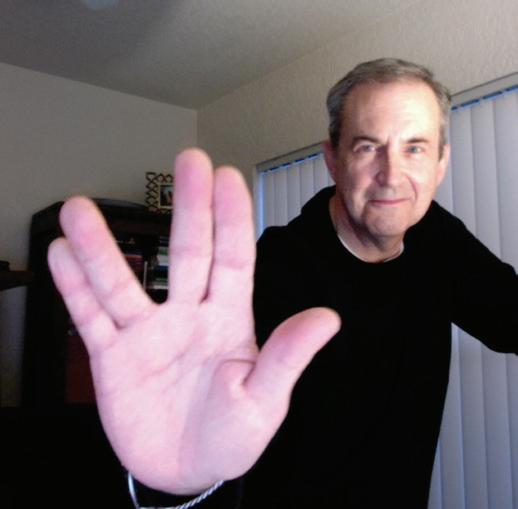

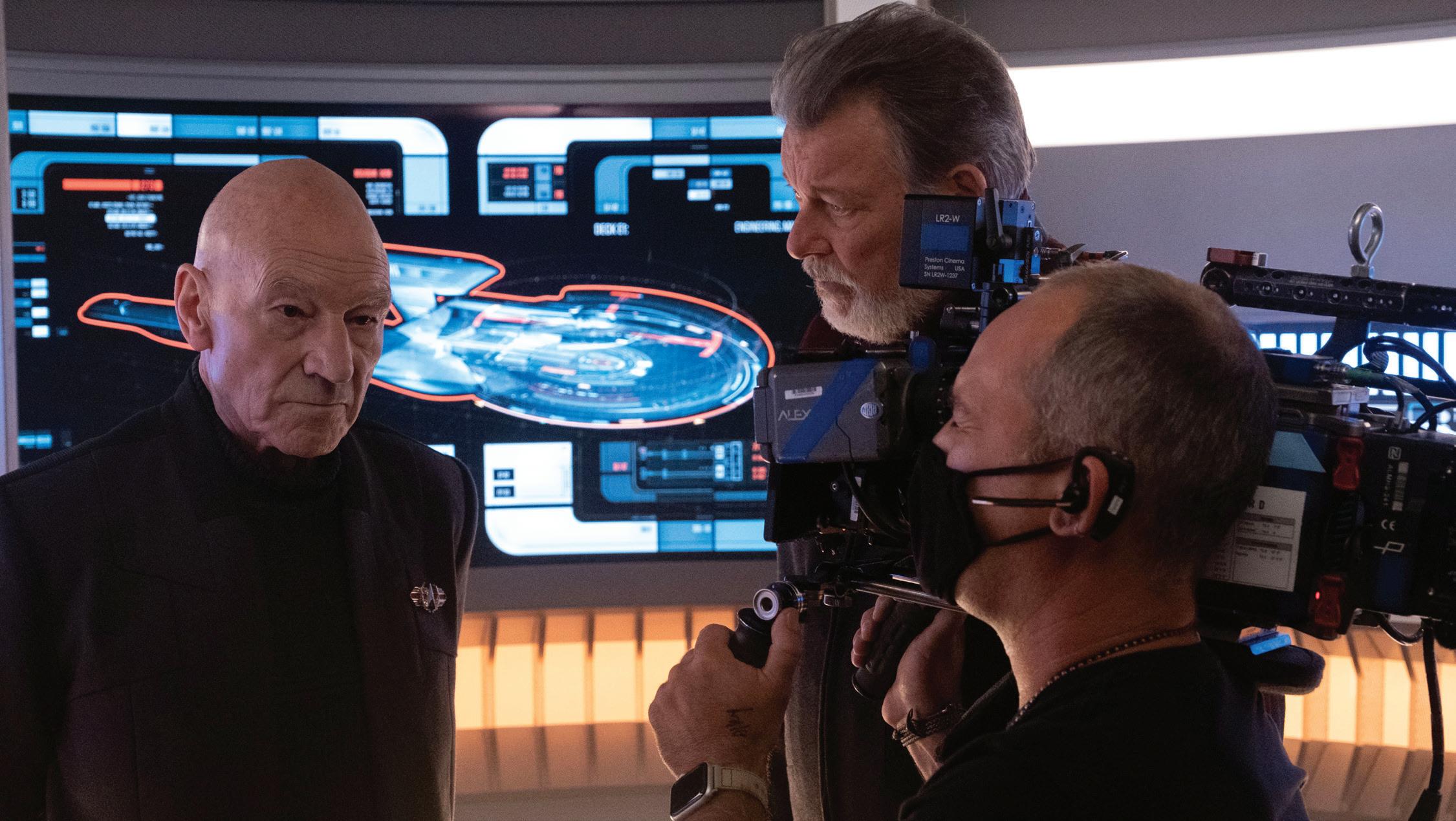

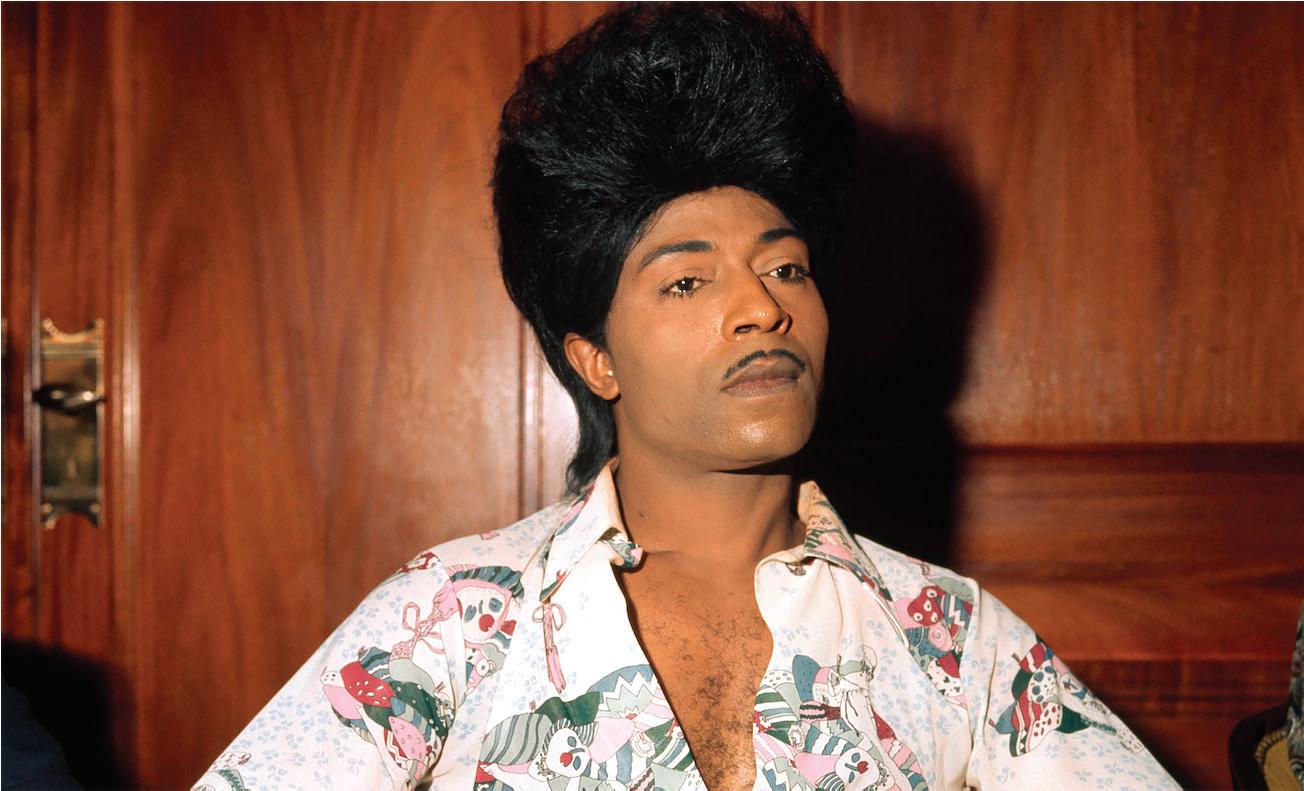

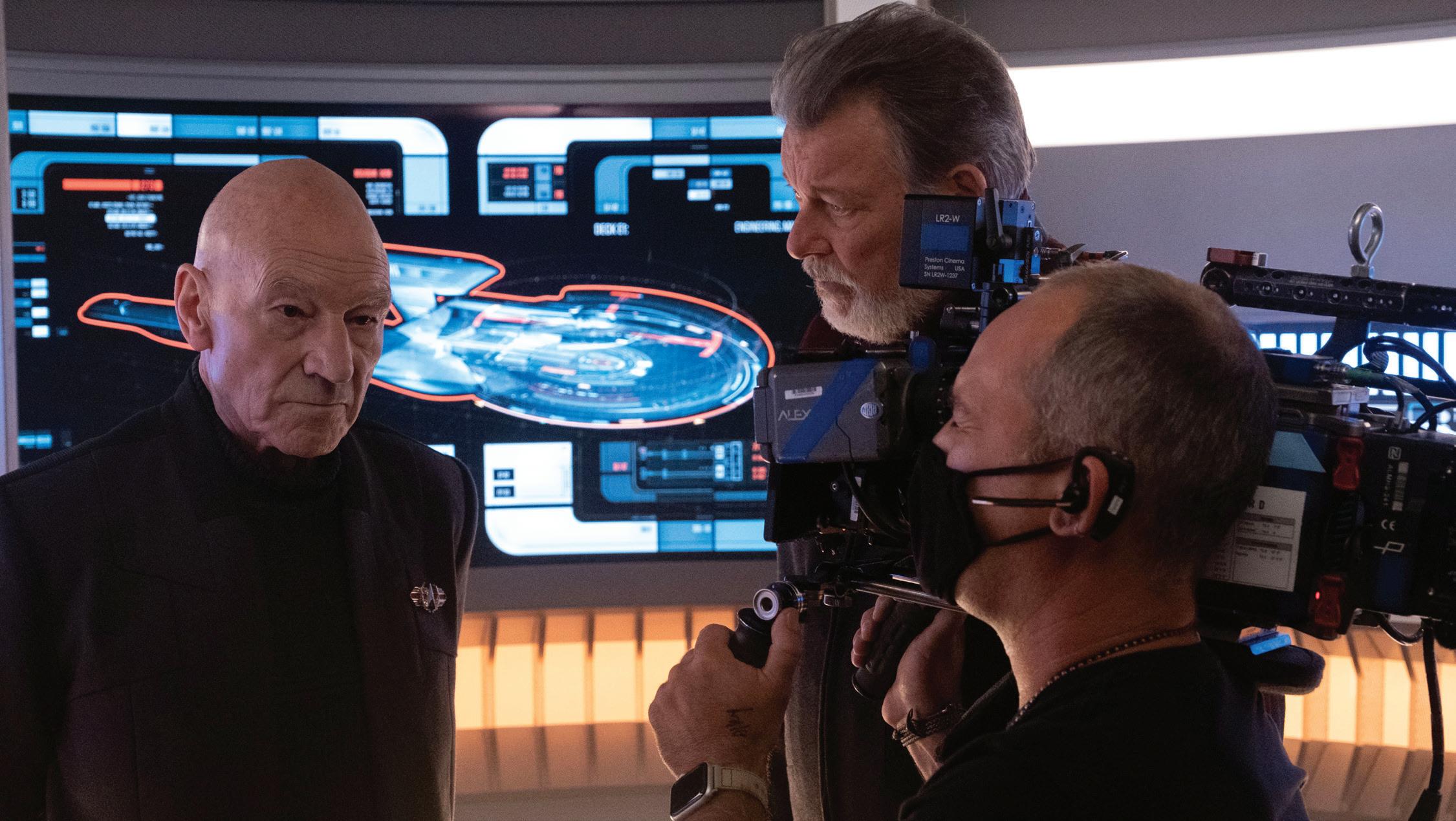

“Design with intention” describes this month’s cover story on Seasons 2/3 of Star Trek: Picard While I’m personally a Star Wars guy (sorry, Trekkies), I have nothing but love and admiration for a franchise born of three (slightly cheesy) years in the late 1960s that went on to become a global phenomenon, generating some $10.5 billion in revenue across every imaginable platform – feature films, spin-off episodics, video games, comic books, novels and so on. Two filmmakers highlighted in Kevin Martin’s story (page 26) – Director of Photography Crescenzo Notarile, ASC, AIC, and Actor/Director Jonathan Frakes –have been intimately involved with Trek’s episodics, and, in Frakes’ case, several features as well.

Crescenzo (first name only, please!) shot Seasons 1/2 of Star Trek: Discovery, before moving over to shoot Picard’s second and third seasons (sharing duties with Jon Joffin, ASC, for Season 3). His years of experience in episodic television were eagerly embraced by Frakes, who says both men bonded over such Trek staples as “foregrounding” and “lens flares.” Frakes describes Crescenzo as “a force on set, so people love him. And he’ll try anything. He even let me sneak in a third camera.”

Making the working day easier for filmmakers has also been a passion of Creative Technologist Annie Chang for the better part of 20 years. Chang, a force in her own right, especially when visiting with “everyone everywhere all at once” as she was at HPA 2023, talks about technology’s relationship to the creative process in this month’s Refraction (page 16). Her recent work at Universal Pictures in “narrative and production ontologies” is built around the realization that “you cannot force technology onto creatives and non-technical people – it must make sense for them and fit their workflows,” she states. And when it comes to what she calls “soft leadership skills,” Chang (one of the most respected women in the technology space) notes: “We must remember our responsibilities in not only setting the strategies for our companies and productions but also our accountability in providing a healthy culture and working environment for our team members.”

Or, to paraphrase one overriding theme at this year’s HPA, “It’s the human factor, guys! Create technology that’s built to support and fuel creativity.”

Kevin Martin

The Final Frontier

“Back in 1996, before CGI established dominion over the Trek-verse, I got to ‘meet’ the Enterprise-E shooting miniature when covering Star Trek: First Contact. That was the first Trek film directed by Jonathan Frakes, aka Captain Will Riker, who again pulled double-duty as actor/ director for a pair of Season 3 episodes of Star Trek: Picard, shot by Crescenzo Notarile, ASC, AIC. Frakes told me that “through the efforts of ILM’s John Knoll and actress Alice Krige, the shot when the Borg Queen’s head slowly descends to join with its body remains one of the finest bits of live-action combined with VFX I’ve ever seen.”

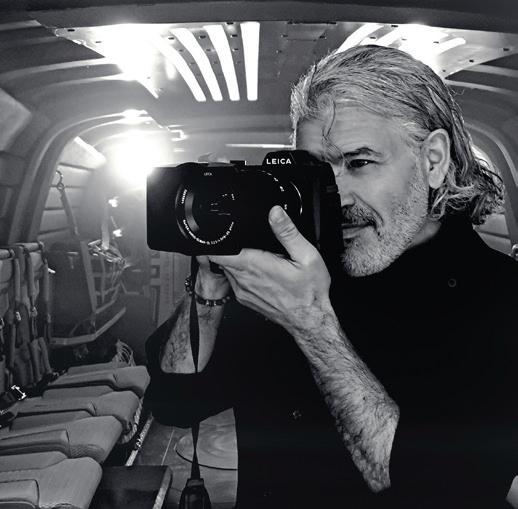

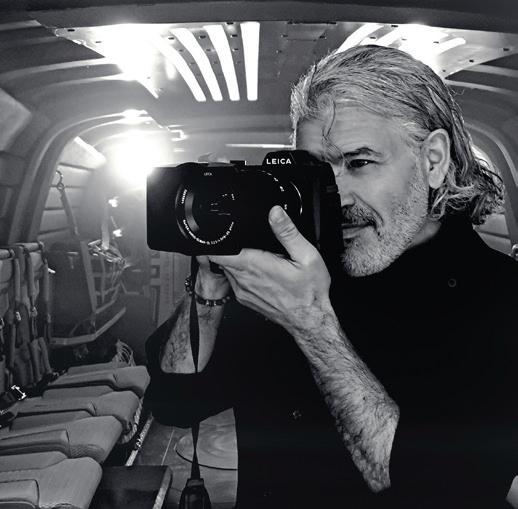

Dennys Ilic

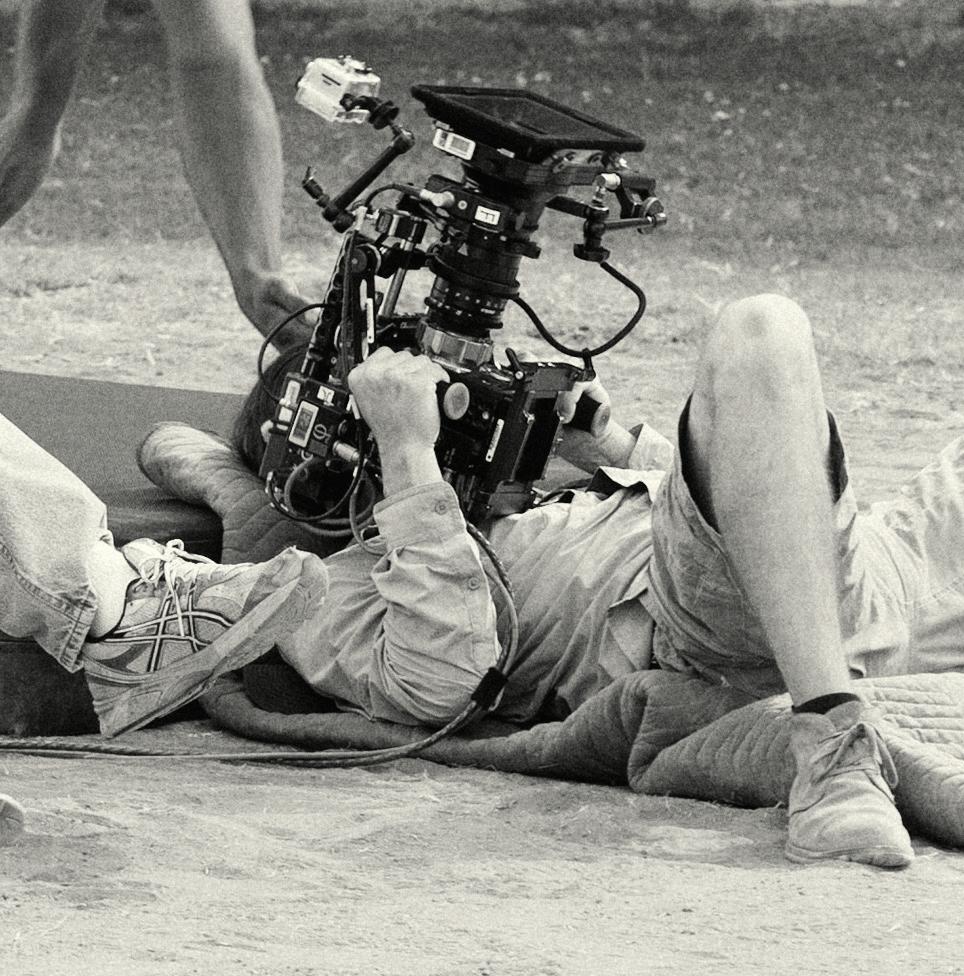

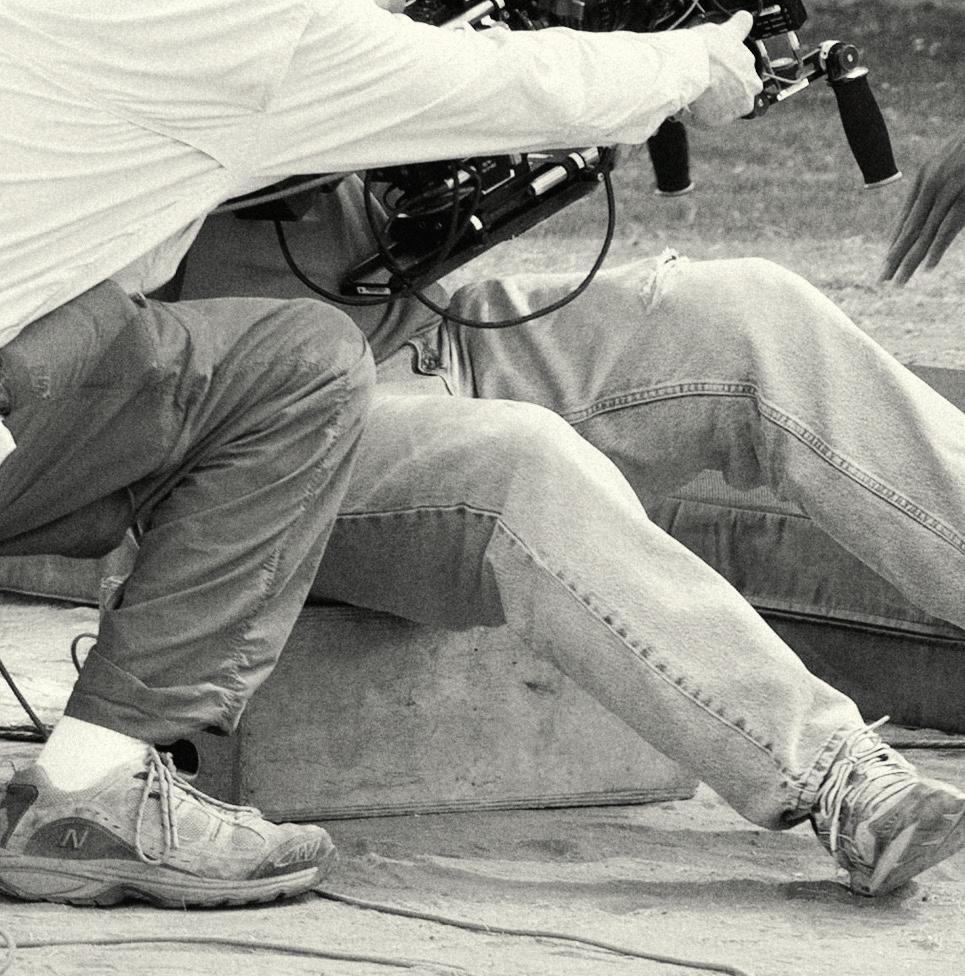

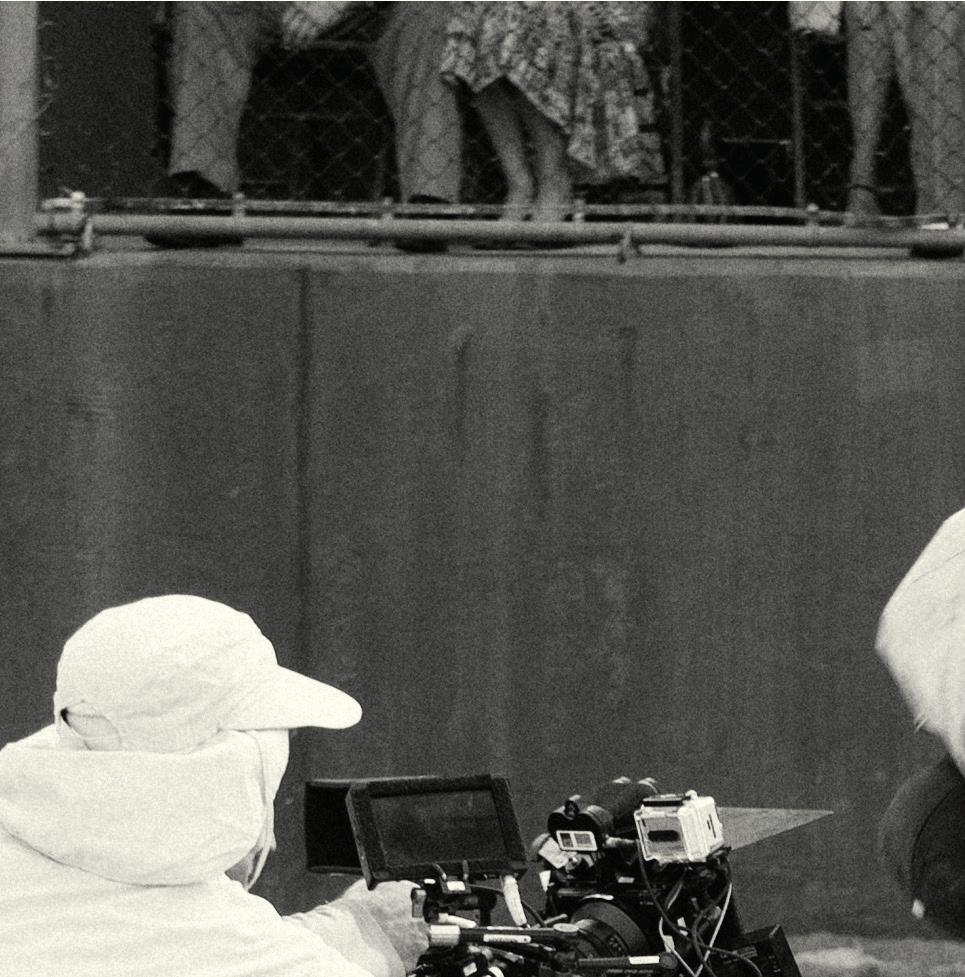

The Final Frontier, Stop Motion

“Although I’ve been shooting stills for 20 years, I started as a cinematographer. I had overlap for a while, having filmed my last feature in 2010. Having a touch of enochlophobia, I found more comfort in the solitude and control of shooting stills, so much so that even my highest profile editorial shoots involved just me and one assistant. As I burrowed more into this world, I found myself back on film and TV sets, but now enjoying the hunt from the shadows for that perfect image that holds a different perspective than the movie camera. Everything came full circle when I discovered the beautiful optics of Leica. If you love the tools as much as the job, then work can’t be anything but joy.”

David Geffner

Executive Editor

Executive Editor

Email: david@icgmagazine.com

10 APRIL 2023

ICG MAGAZINE

CONTRIBUTORS

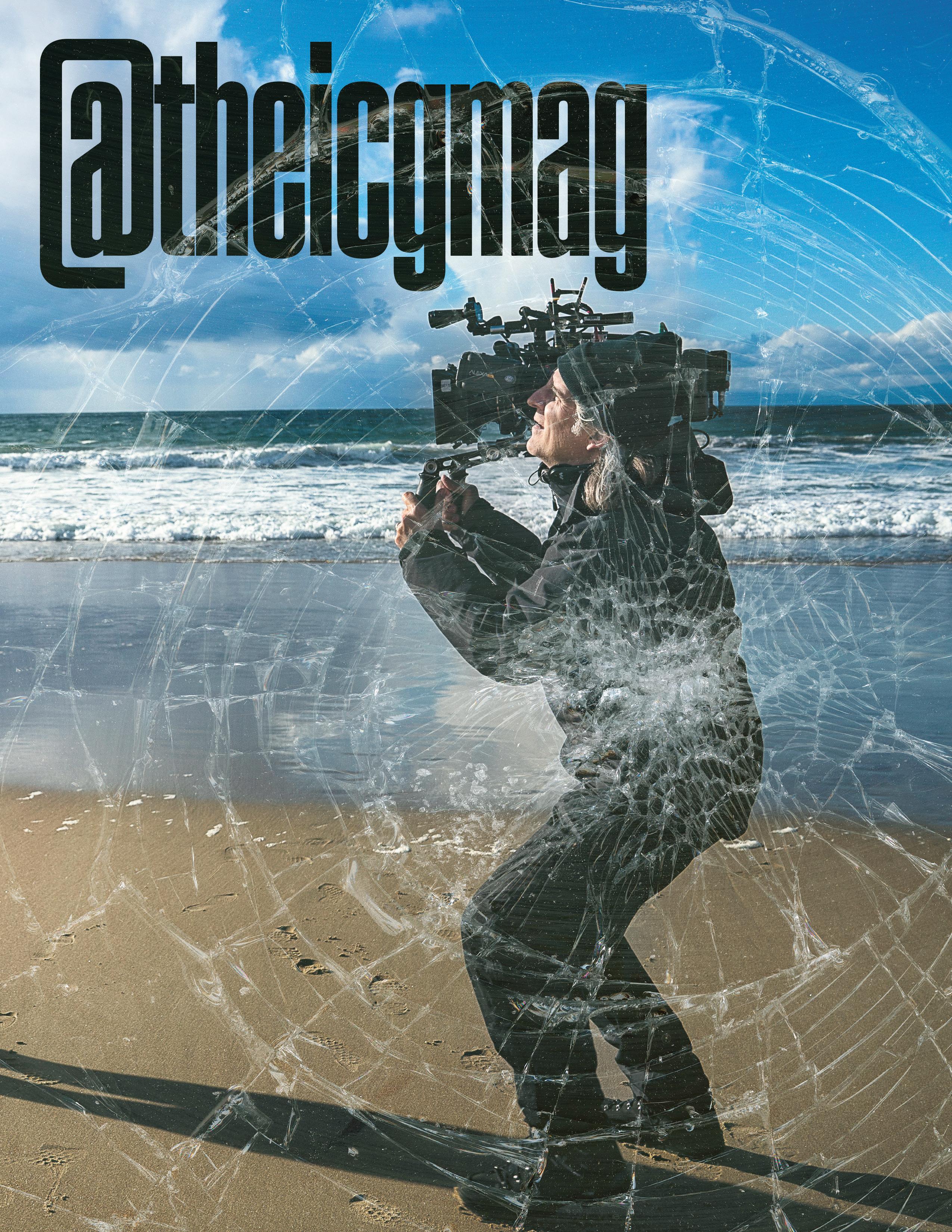

Cover photo by Trae Patton

Photo by Sara Terry

WIDE ANGLE

Create Atmosphere

T IFF en Bl A ck F og & nI gh

Fog F I l ers

Tiffen adds a new tool for the cinematographer’s pallet. Paired with digital cameras, Black Fog and Night Fog Filters can provide a soft highlight glow reminiscent of the classic double fog cinematic look.

Black Fog provides an overall atmospheric softening that creates a smooth wide flare from the highlights yet keeps the blacks, black without overly muting colors or losing detail in shadows. A subtle effect, it can be used to add an overall look to a project.

Night Fog yields a natural fog effect with overall atmospheric softening and wide flare, coupled with unique contrast reduction technology that reduces highlights without darkening shadows. In light grades it provides a beautiful new look. In strong grades it flattens the contrast and desaturates color so it is useful for day-for-night.

On Bridgerton Season 3, we often shot in historical locations that had priceless artwork. Therefore, we were not able to use atmosphere in the air. I achieved a similar look using Tiffen Black Fog Filters. They made it feel like there was ambient diffusion in the space. Also, when I lit the filter with a backlight, it added a creamy soft flare that enhanced the feeling of atmosphere even more, which I was able to utilize during key intimate moments.

Alicia Robbins Director of Photography

‘‘

new tiffen.com

GEAR GUIDE

AGITO Trax – SkyTrax

PRICING: DEPENDS ON THE SETUP WWW.MOTION-IMPOSSIBLE.COM

With the addition of the SkyTrax system to the AGITO Trax system, users can under-sling payload capacity of up to 100 kg. Following AGITO’s fully modular approach, the AGITO Track can be repurposed and converted to the SkyTrax System, or an additional track can be added. Lengths run from the largest 8-ft (2.5-m) sections to the smallest 2-ft (0.6-mm) sections, creating a system from 10 to 100 m or more. It runs fully enclosed in the SkyTrax hoops, keeping the system safe and secure, with a third rail for running cable management. The system is LOLER tested up to and beyond a 100-kg payload capacity. It’s fully customizable for multiple studios or live events. Overhead shots from perms or temporary elevated structures are newly adapted with ease. “Lifting the camera in the air with SkyTrax gives AGITO a whole new perspective,” says Rob Drewett, CEO of Motion Impossible.

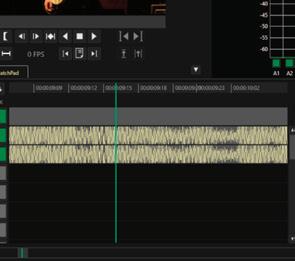

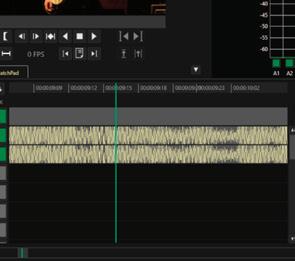

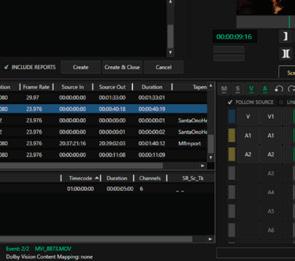

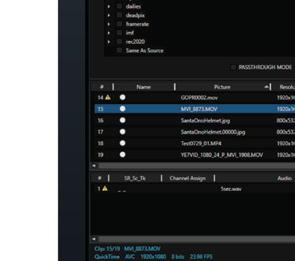

Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve for iPad

PRICING: FREE DOWNLOAD FROM APPLE IOS APP STORE. STUDIO FOR IPAD VIA ONE-OFF IN-APP PURCHASE FOR $95

WWW.BLACKMAGICDESIGN.COM

With DaVinci Resolve for iPad, creators can extend digital workflows in new ways and places. Optimized for MultiTouch technology and Apple Pencil, DaVinci Resolve for iPad features support for cut and color pages, as well as Blackmagic Cloud multi-user collaboration – cutting-edge AI tools powered by the DaVinci Neural Engine, including Magic Mask, Voice Isolation, Dialogue Leveler, Smart Reframe for social media and more. The cut page is perfect for projects with tight deadlines as it has a streamlined interface designed for speed, with features such as source tape for visual media browsing, quick review, and smart editing tools. The sync bin and source-overwrite tools are the fastest way to edit multi-cam programs, with easy-to-create, perfectly synchronized cutaways. The color page has a wide range of primary and secondary color grading features, including Power Windows, qualifiers, a 3D tracker, advanced HDR grading tools, and more.

12 APRIL 2023

DJI Goggles 2

PRICING: $649

WWW.DJI.COM/GOGGLES-2

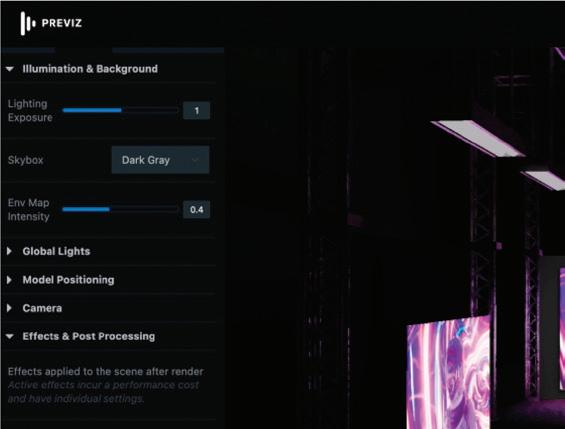

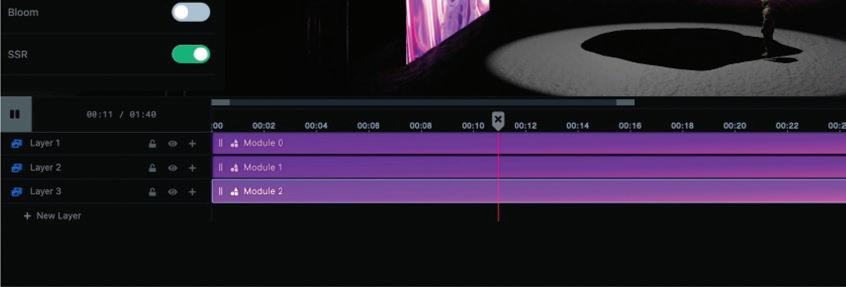

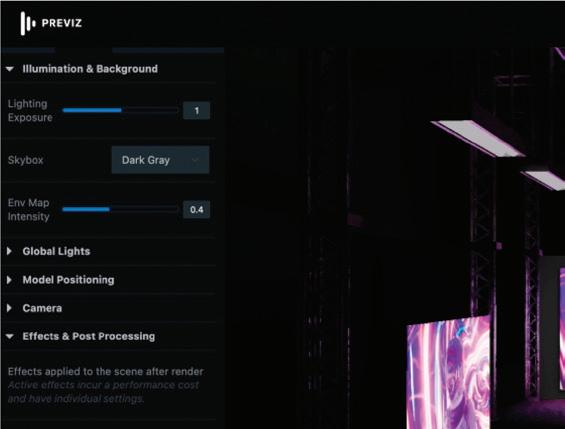

disguise Previz

PRICING: FREE 14-DAY TRIAL; FROM $49 PER MONTH AFTER TRIAL WWW.DISGUISE.ONE/CLOUD

Disguise’s new Previz, integrated into its cloud platform, is a web-based app that lets filmmakers share a 3D replica of their virtual production stage – including geometry, textures, and a baked version of the timeline. So, no matter where disguise users are in the world, they can preview, comment on, and approve every LED visual, all before the first shot. “Previz has allowed us to communicate ideas and concepts in a meaningful and visual way that is simple to use and straightforward to create and share,” describes Troy Fujimura, Head of Design and Technology at Centerstage. With Previz, production teams can ensure that every virtual production scene looks photoreal from every angle before heading to set, reducing potential production delays as well as the need for extensive fixes in post. Previs is available as part of the disguise Cloud Pro and Studio subscriptions, which let creative teams manage 3D files, animations, cameras and lighting from a mobile-friendly interface. It is also directly connected to disguise Drive, which enables fi lmmakers to easily share preview links and store multiple stage models.

DJI’s Goggles 2 is a next-generation headset that offers a smaller, lighter and more comfortable fit, with a crystalclear FPV image comparable to those from other DJI drones. The unit features a clearer Micro OLED screen with adjustable diopters, so people who normally wear glasses do not need to use them with these goggles. When used with the DJI Motion Controller, the operator can control the aircraft and the gimbal camera freely to meet his or her shooting needs in various scenarios. An intuitive touch panel on the side of the goggles enables the user to easily control settings with only one hand.

13 APRIL 2023

GEAR GUIDE

LiteGear’s Auroris

PRICING: X SYSTEM $25,999, $18,990 (FIXTURE ONLY); V SYSTEM $13,990, $10,590 (FIXTURE ONLY) WWW.LITEGEAR.COM/AURORIS

This overhead light source combines high-quality color rendition and precision control in one easy-to-use package. Powered by LiteGear’s Spectrum technology, Auroris X is built with 24 large-format pixels mappable source that can cover a 100-square-foot area with just one fixture. Designed to be light on weight and easy to rig, Auroris X is one of the slimmest, most versatile soft lights. The Auroris V brings the favorite features of the Auroris X into a compact, half-sized kit – perfect for rigging on smaller sets and in tighter spaces. The Auroris V’s unique shape allows rigging horizontally, vertically or as an overhead. Both units feature next-level Spectrum color for cinema-quality color output, with high-quality white light from 2,000K to 11,000K, and wide-gamut hue selection with full-spectrum desaturation.

SRG-A40 and SRG-A12 4K PTZ Zoom Cameras

PRICING: SRG-A40 $3000, SRG A12 $2500

Sony is expanding its lineup of pan-tilt-zoom (PTZ) cameras with the addition of two 4K models with built-in AI analytics. The SRG-A40 and SRG-A12 cameras automatically and consistently track and naturally frame presenters, regardless of movement or posture, for seamless content creation and control – all without operating a computer. The new PTZ Auto Framing technology features automatic operation for quick object tracking and rediscovery, as well as multiple Auto Framing options. Highlights of the cameras include image quality with automation, the flexibility of IP, powerful zoom, remote control, and easy configuration and operation. They are ideal for use in education, corporate, medical, government, broadcast and faith applications, as well as for live events. They will be available in North America in September.

14 APRIL 2023

WWW.PRO.SONY GEAR GUIDE

GEAR GUIDE

Atlas Slider

PRICING: STARTS AT $5,800 WWW.MRMOCO.COM

MRMC’s Atlas Slider is versatile in its modular design, meaning it can be upgraded and expanded to suit a range of applications, manual or powered. It can carry up to a 40-kg payload and offers precise mechanics, such as a fully equipped motion-control system. Perfect for studio and stage, the slider comes with a range of setup options customized to specific demands. Rail options include 0.8-m and 1.2-m sections, with 2-m and 3-m sections. Maximum length is 12 m. It is assembled without tools. Each section is equipped with feet that can be easily and quickly adjusted to any surface. Modularity allows it to be set and leveled on the ground, on tripods or even hung upside down under the ceiling. It can use a number of Slidekamera heads by MRMC, with cameras up to heavy broadcast and cine models.

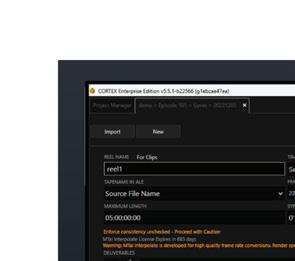

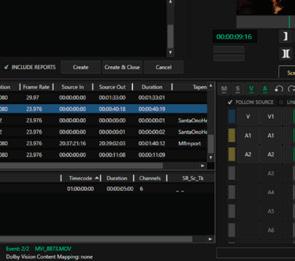

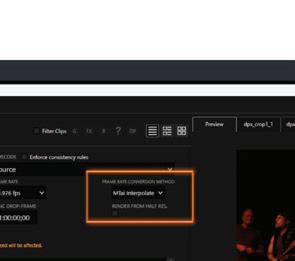

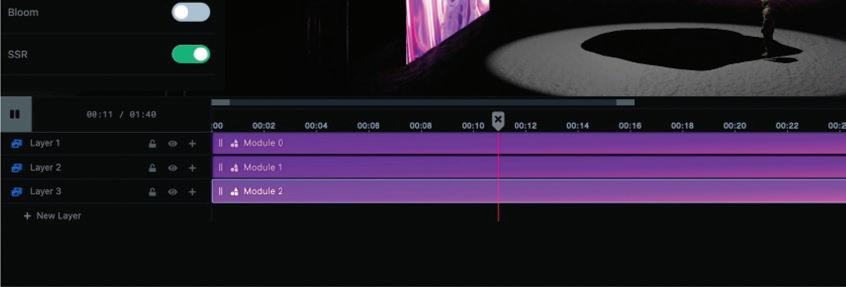

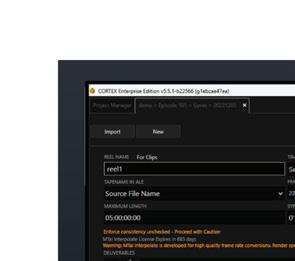

MTI Film Cortex v5.5

PRICING: FREE FOR NOW WWW.MTIFILM.COM/CORTEX

“MTai Super Resolution Uprez was developed using advanced machine learning techniques to analyze low-resolution content and generate new high-resolution content by filling in missing details that were lost in the original low resolution,” explains Wojtek Janio, director of Restoration MTI Film. “At MTI, we’ve been using MTai Super Resolution Uprez to enhance the quality of series and movies mastered in SD and upscale them to HD or UHD resolutions. Our leading-edge algorithms are at the forefront of using machine learning techniques to improve content quality and provide the best experience for audiences.” Frame Rate Conversion uses machine learning to interpolate between frames, increasing or decreasing the frame rate without ghosting, stutter or distortion. MTai Uprez applies a similar process to the task of increasing frame-rate resolution. The tool analyzes adjacent pixels within a single frame to produce intermediary pixels in a smooth transition. The result is not simply a larger image but one with greater detail and clarity.

15 APRIL 2023

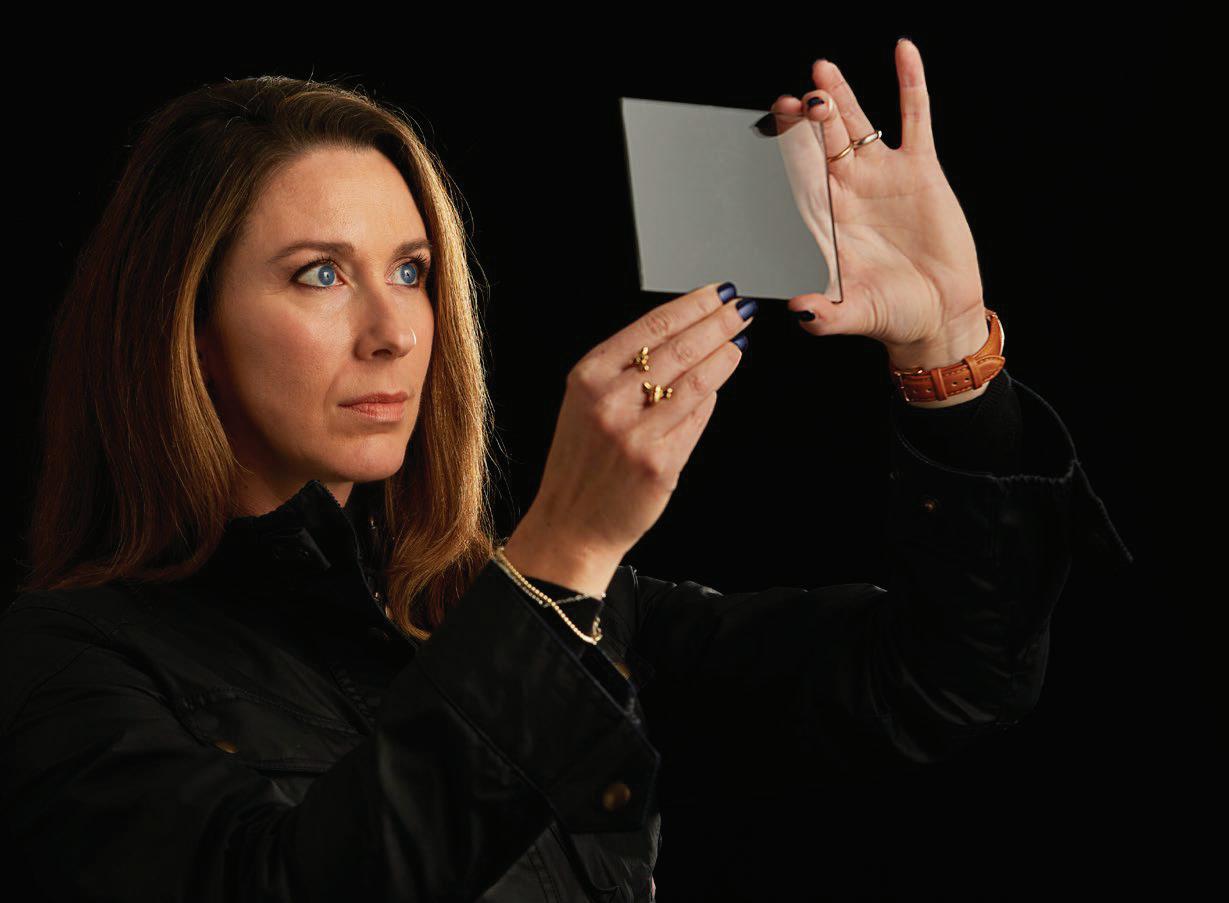

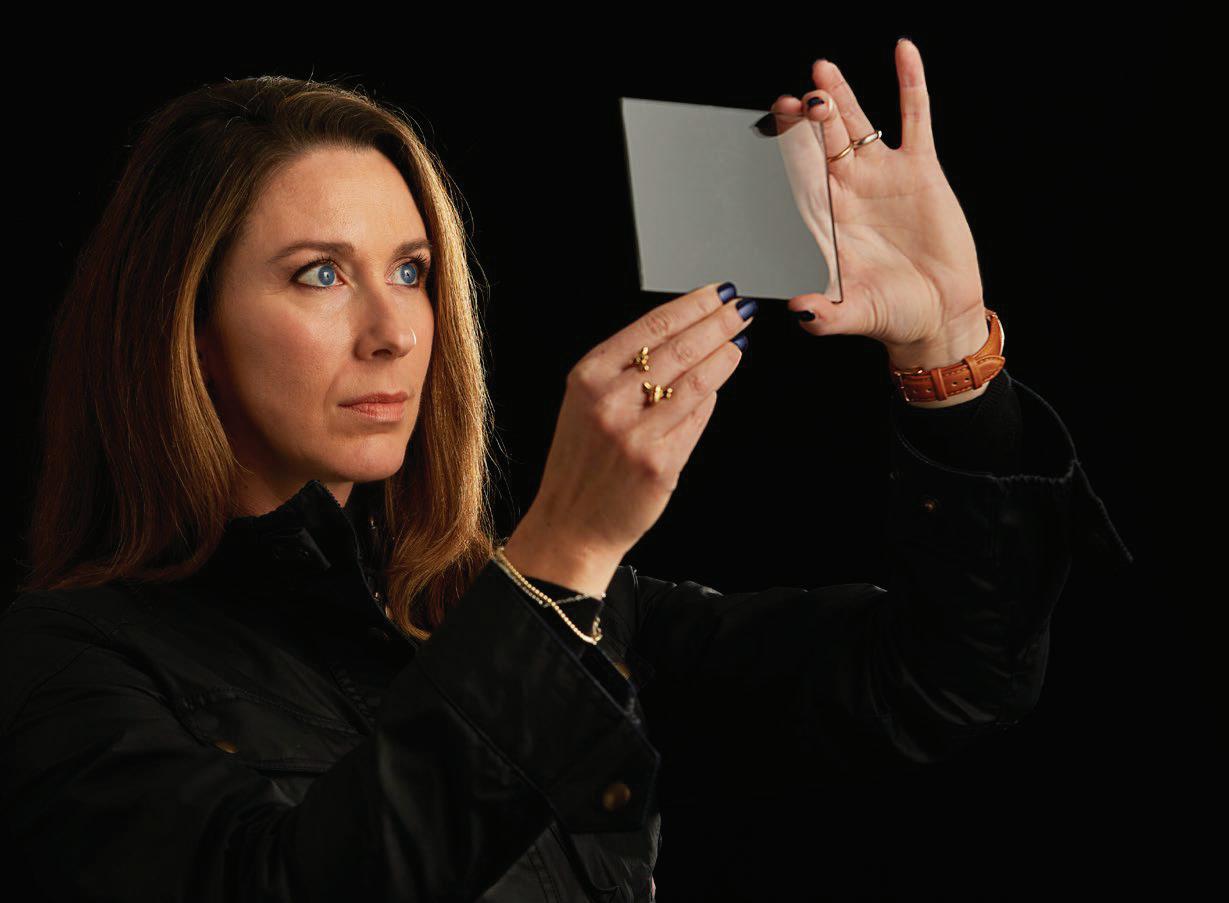

ANNIE CHANG

VP, CREATIVE TECHNOLOGIES, UNIVERSAL PICTURES

16 APRIL 2023 REFRACTION 16 APRIL 2023

PHOTO COURTESY OF ANNIE CHANG

I am often asked how to become a creative technologist, and here’s my answer.

First off, you need an innate desire to solve problems and make things better, but you also need the ability to look at problems and solutions creatively. Growing up, my dad was a computer scientist and electrical engineer for IBM; he and my brother were always tinkering with electronics and I loved to do the same. By the age of 12, I was soldering components onto PC boards for my dad’s side company (willing child labor since I had fun doing it). As my mom loved to sing, and my sister was and is a great artist, I also enjoyed being creative. I picked up the bass guitar in high school and dabbled in other instruments, including the French horn. I wanted to be a veterinarian, but I had a difficult time with organic chemistry in college. So, after a few fits and starts with other majors, and playing bass guitar in bands, I decided to start my recording studio and become a recording engineer. The one problem? My college didn’t have that program, so I turned to electrical engineering technology, which I thought would be helpful for sound recording.

I never did break into the music industry, so the first half of my career was spent working with new distribution technologies of the time, including DVD, digital cinema, HD telecine, Blu-ray, Apple iTunes, 3D Blu-ray, electronic sell-through (the predecessor to streaming), and the videotape-to-file transition. I helped break down confusing technical topics into things that non-technical people could understand and utilize to further these new technologies with consumers.

One example is visualizing the idea of file formats and compression schemes, which was always confusing for people. I would take a small plastic Tupperware container and a printout of one frame of a movie. I would show them that this was an uncompressed frame that would not fit in the

container. Then, I would crumple it up, showing that it was compressed, and place it in the container, explaining that we can make it fit in smaller places through compression. As I uncrumpled the paper, I would explain that the image was getting decompressed. Then, I would show it side by side with another printout that had not been crumpled to show that the compressed version, with all of its creases, would never be as good as the original uncompressed picture. This demo explained lossy compression scheme and, to this day, people who saw it rave about how they finally understood the concept of compression.

At The Walt Disney Studios, I was a digital technologist; when we started shooting on the RED ONE and MX cameras for The Muppets 2 and Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, chaos ensued because digital cameras created something called a “workflow,” which was incredibly foreign compared to the film process. Although we had been editing digitally with AVIDs for years, the major sea change was that we were now digitally kicking off the image source, the camera files. Gone were the well-understood chemical baths; in was a new world of proprietary camera and file formats, codecs, transcoding, resolution resizing, easy-to-mess-up color, and playback digital video.

My deep understanding of file formats and compression schemes was crucial to taming the chaos, and it provided me with an opportunity to move from distribution technology to production technology. The first task was to figure out why a show’s dailies didn’t look like their editorial media. It turned out to be the ubiquitous QuickTime container/ playback issue that plagued many of our early filebased shows. I also got to figure out how the VFX department on Beverly Hills Chihuahua 3 could do

their own camera plate pulls (one of the first shows to do that outside of a post house in 2012).

In 2016, I became VP of Technology for Marvel Studios, where I oversaw both Production IT and Production Technology. Production IT is the IT support for a movie or episodic production. It entails the installation and support of storage and networking but also goes into things like identity management, email, and other applications. Production technology was the precursor to creative technology, as it dealt with the workflows that sit on top of the IT infrastructure, but focused on production and post. My passion was developing strategies for filmmaking’s future and working towards that goal (although building a screening room for the VFX team on Black Panther in the middle of a tornado in Atlanta, GA, was interesting).

I am now in my fifth year as a creative technologist at Universal Pictures, where I’m seeking out new technologies and workflows to help solve problems for our film productions. I work closely with our Production IT team and shape the strategy and future vision of how Universal uses technologies for creative development, pre-production, physical production, VFX, post-production and archival. Creative-technology roles at the studios were born from traditional production-technology roles. The new terminology is more apropos to the fact that we want to make things easier, better, or more efficient for creatives, while always preserving their intent. To be a Creative Technologist, you must love solving problems but also have a knack for understanding how creatives want to work.

One big realization is that you cannot force technology onto creatives and non-technical people – it must make sense for them and fit their workflows. This means partnering with our studio executives and/or production crews to help them understand the ins and outs of specific technologies.

17 APRIL 2023 04.2023 17 APRIL 2023

That may include helping to better understand and advise on using ARRI’s ALEXA 35 camera, which has an entirely new color-management science and new features, such as Textures, or it could be to help figure out ways to take advantage of workflows being fully digital. (Even if the footage is shot on film, it is scanned into digital files right away.) It could also mean helping make sense of how artificial intelligence can be used to help creative development and visual effects.

Creative Technologists also participate in efforts to help drive commonly needed standards for our industry. One of the most exciting industry efforts is the updating of ACES (Academy Color Encoding System). ACES 1.0 was the first free, open-standard, color-management system – from camera through finishing and archive – that was production-ready upon release. It was the result of over 10 years of research, testing and field trials; many ICG readers are familiar with ACES 1.0 and may well have used it, loved it or hated it. Now, with a well-deserved update, ACES 2.0 will be available in 2023 (fingers crossed) with major improvements, addressing many concerns from ACES 1.0.

Another exciting effort is what we are doing at Universal Pictures around ontologies, a common language that enables applications and systems to exchange metadata easily and efficiently. We collect tremendous amounts of data in pre-production and production (camera notes, AD notes, script supervisor notes, editorial code books, VFX shot tracking databases, etc.) that are digital (instead of just handwritten). Wouldn’t it be interesting if we could connect all that information and relate it together to provide a rich context to others downstream? And what if we could associate assets like camera files, editorial media, VFX comps, models and other files to that web of context? This concept could make it easier to find our assets. Now, imagine if you could include script and call-sheet/schedule information into that web of information.

We’ve tested these ideas out at Universal, with some interesting results.

The process begins with these two common “backbones” of information: Narrative and Production ontologies. The Narrative ontology has everything to do with the story and comes from the script. This would include characters like Dominic Toretto and Letty Ortiz (from The Fast and the Furious series), scenes, props, vehicles and story locations. The Production ontology is the real-world equivalent of the Narrative. For example, the character Dominic Toretto is played by Vin Diesel and his real stunt doubles, while Dominic’s Charger is several different picture cars in the Universal inventory.

The camera slate is a crucial piece of Production information that ties the Narrative and Production worlds together – through this bridge we can relate the Narrative and Production ontologies. Starting to manage assets when we make them is too late in the chain. Instead, we want to see a database of the Narrative and Production elements related to each other first and then start associating assets as they are created to that backbone. Then, if you were part of the production crew, you could search by shoot day, or if you were on the VFX team, you could search by VFX shot ID. All of the data would be interrelated, allowing crew members (and eventually our archivists after the show wraps) to find whatever they are looking for through whatever method they are familiar with.

This crazy concept is part of the MovieLabs 2030 Vision. MovieLabs is a technology joint venture of the major Hollywood studios, and they released a paper [MovieLabs 2030 Vision] that details what the future of filmmaking could look like by 2030.

Before you think this is disconnected mumbo jumbo from studio executives working in a vacuum, many of us who helped write the vision (including myself) have worked on productions and seen firsthand the amount of inefficient and labor-intensive tasks required to make a movie or episodic. Part of the MovieLabs Vision is to create connected, streamlined workflows that make it easier to find and work with assets (like camera files, editorial

media, visual effects shots, etc.) that we create on our productions by leveraging all of the metadata that isn’t connected – yet.

The last thing I’ll leave you with is technology as it relates to leadership and management. Most people think technology leaders are only supposed to make strategies for the future. But one key overlooked area is the soft skills needed for good leadership and management of other technologists. To be brutally honest, many technologists, scientists and engineers are not always the most extroverted people (or necessarily socially adept). But the corporate ladder dictates that if you want to retain young technical talent, you must promote them to manager. Yet many companies do not provide these technologists with training and education on how to manage other people. The new manager gets promoted to a Director level, then a VP, then SVP, all the while not understanding what it takes to properly lead and motivate their team. Eventually, that person becomes a CTO, and those under him/her suffer.

I do not know if this is unique to technology fields, but I have experienced it in a prior role (thankfully, not at Universal). And while this presents no action item for the cinematography audience, I did want to extend the fact that when you are in a leadership position, you must remember your responsibility in not only setting the strategies for your company/ production but also your accountability in providing a healthy culture and working environment for your team members.

I was once told that my leadership style was poor and needed to change, and I began to believe that critique. But after receiving several awards for leadership and innovation from the Advanced Imaging Society, Hollywood Professional Association, TVNewsCheck, and Women in Technology Hollywood over the last few years, I’ve realized that my prior leader was wrong and that my leadership style, which includes what I wrote above, is something that technology leaders should model. Technology can sometimes be confusing and overwhelming, but that is why people like me are here to help navigate it.

18 APRIL 2023 REFRACTION 04.2023 18 APRIL 2023

"We collect tremendous amounts of data in pre-production and production... wouldn’t it be interesting if we could connect all that information and relate it together to provide a rich context to others downstream?"

cinegearexpo.com

RYAN PROUTY

BY DAVID GEFFNER

BY DAVID GEFFNER

20 APRIL 2023 ON THE STREET 20 APRIL 2023

PHOTO COURTESY OF RYAN PROUTY

DIGITAL IMAGING TECHNICIAN

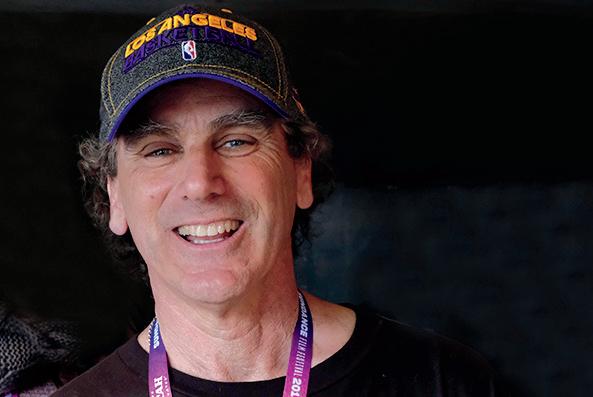

A lunch hour spent talking to Local 600 DIT Ryan Prouty, at the February 2023 HPA Conference in Palm Desert, CA, is both an educational and technologically fun experience. Prouty, who has spent some 20 years in the motion picture and broadcast industry trenches as a digital imaging technician, broadcast studio camera operator, virtual reality cinematographer, documentary producer/ director, and certified Phantom technician, is also, in his own words, “a proud ICG member” since 2013.

He’s also a man on a mission, as the two companies Prouty founded, COLORSPACE [colorspacevan.com] and CinemaScan [cinemascan. la], are intent on maximizing efficiency (and, as a result, safety) on film and TV sets. Standing outside HPA’s “Innovation Zone,” where a multitude of vendors has come to share its products with technological thought leaders from around the globe, Prouty demos COLORSPACE 1: a 4×4 Mercedes Sprinter van housing a 4K HDR color suite; a two-seat edit bay; and equipment for monitoring, ingesting, and coloring footage for productions on location. But, Prouty explains, COLORSPACE is much more than just leading-edge tech. The vehicle (COLORSPACE 1 was launched at CineGear 2019, with COLORSPACE 2 launched at HPA 2023) “gives directors the tools to see what they need to see in the moment,” Prouty tells us. “Previs, storyboards, dailies, live images et cetera. At the same time, the technology is invisible to the end user as it’s tucked behind a solid partitioned wall, preventing humming fans and blinking LED’s from taking away from the creative decision-making experience.”

As Prouty explains, COLORSPACE has a unique history. “It was discovered by Antoine Fuqua in 2020 for Netflix’s The Guilty as a solution for directing remotely during times of COVID,” he says. “Antoine ultimately preferred working out of COLORSPACE 100 percent of the time,” he adds, and has subsequently taken Prouty and COLORSPACE on to large-scale productions that include Amazon’s The Terminal List (shot by Armando Salas, ASC) and Emancipation (shot by Robert Richardson, ASC).

In addition to the two COLORSPACE vans, Prouty was at HPA launching his set-scanning service, CinemaScan, which he describes as a LIDAR set scanning service with three unique benefits to any production. “Number one is that it turns your location into a digital collaboration tool similar to Slack or Microsoft Teams,” Prouty details. “Using the art department as an example, we’re not talking about them having to send a blank email asking: ‘Hey, you know in the backyard by the fence and the barbecue? Should we have that propped to the left or the right?’ with a response that’s usually: ‘What are you talking about?’ Instead, they can send

a link to the actual location that we’ve scanned, and ask: ‘Do you want it here or here?’’’

The second benefit of CinemaScan, Prouty continues, “is to take all of those decisions – visually made through our scan – in prep and communicate them with any department via a fly-through video, which is easily made through the same scanning equipment, nearly instantaneously, and is customizable to highlight any detail or perspective. Imagine a video that shows a crewmember exactly where his or her parking space is, where to access the shuttle to set, where to get breakfast, where the bathrooms are, where the appropriate staging is for their carts – I am a DIT, after all,” he smiles, “and exactly where the first shot of the day will occur.”

The fly-through videos Prouty shows me are not unlike what your favorite real-estate broker might send for a prospective house sale, but with much more detail. “We can make custom videos on an individual, a department, a crew-wide or even a shot level,” he adds. “The production office could include the link or QR code to the video on the call sheet, and now everyone on the crew gets a quick 45-second walk-through of the location before they’ve even parked their cars.”

Prouty says the goal for all productions should be to “turn on the camera, intelligently placed and pointing at the right thing, with all of the lighting and talent in place as quickly as possible. I know that will never be one or two minutes after call time – but it should not be three hours, as I’ve experienced too many times to count,” he says. “One of the biggest barriers to cutting down the start time to say, 45 minutes to an hour, is the crew not being familiar with the location.”

The third spoke in Prouty’s drive for efficiency comes from the meshing of CinemaScan’s two technologies – a point cloud LIDAR scan coupled with panoramic photography. “We can export the point cloud data into Unreal Engine 5,” he notes, “insert some meta-humans, and have a good understanding of what the finished product will look like. As a crewmember, very rarely did I understand that aspect of my day, so adding the data into Unreal Engine creates this tool that can discover the nuances of any given location and communicate more fully what’s happening on the day, all before a single pixel is captured by camera.”

From a cinematography standpoint, CinemaScan holds some intriguing potential. Prouty offers up the scenario where a DP is finishing a commercial in New York, “your producer is with the location in L.A., and your director may be in London,” he describes. “Using the LIDAR data and Unreal, they can all do scene blocking in the actual location, online, across the world and across time zones.

“I know from experience many DP’s and directors like to feel their craft in the moment,” Prouty’s quick to add, “and, of course, we never want to lose that creative spontaneity. But this tool allows creatives to block out their slam-dunk shots in advance, and get them in a quicker, more efficient timeframe, which allows time for more fine-tuning before the next setup.”

When asked about CinemaScan’s comparison to pre-viz, Prouty says, “the kind of previsualization the DP, director, and VFX super have been doing for years on action films was an initial inspiration. But this is quick and cheap previs for logistics to achieve the first shot of the day much more quickly, as opposed to a high-resolution previz that’s going to make its way into VFX at some point on the project. We scan at about 1500 square feet per hour, so this property I’m demoing now and is also on our website was done in a hair under two hours.”

Prouty says that his background as a DIT means he is forever balancing capability versus portability. “I want to be able to say ‘yes’ to everything that’s asked of me,” he shares. “But I also want to maintain the smallest possible footprint on set. When I’m hired on a job, I ask the basics: ‘Are there stairs? Are we on the beach? Is the roof location using three scissor lifts!? It is? Yikes!’”

In simple terms, Prouty says that “the more educated I am as a crewmember about a location, the more intentional I can be about providing the DP with the right capabilities and having the most efficient footprint on set,” he continues. “The location on the demo I’m showing is a singlestory family home, where the software has already measured the doorways to let me know there would be no problem bringing my 50-inch DIT cart. If the location was a four-story building with limited roof access, I’d know to probably be coming with just a Pelican case.”

As is often the way with Local 600’s innovative membership, Prouty says CinemaScan came out of a need to “scratch our own itch. I was on a location with the COLORSPACE van, and AD’s were too busy to provide us with any location data,” he concludes. “I figured if I made it so quick and easy all they had to do was point, we’d have better results. So, I came an hour early, flew my drone over the set, and imported those files/data into Polycam [a 3D scanning app for iPhone and Android]. I then went up to one of the AD’s with a 3D-rendered map and said, ‘Hey, I just need you to point to where we’re shooting today.’ It didn’t take too long to recognize its marketability aspect, and then the sparks started flying about how this type of technology could educate the crew and, in essence, give us the ability to answer our own questions.”

21 APRIL 2023 04.2023 21 APRIL 2023

KRISTEN ANDERSON-LOPEZ & ROBERT LOPEZ

CO-EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS/CREATORS/SONGWRITERS

BY PAULINE ROGERS

Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez have won 22 industry awards and have been nominated for 40 Oscars, including Original Song (2014 Frozen and 2018 Coc o), along with a Primetime Emmy for Music and Lyrics for WandaVisio n in 2021. The two met at the BMI Musical Theatre workshop in 1999 and started dating seriously just before Y2K.

“We started working together in 2002, mostly to spend more time together!” shares Anderson-Lopez. Their first songs as a team were for a Disney Channel show called Bear in the Big Blue House . After that, they went on to write Finding Nemo The Musical for Disney's Animal Kingdom. That led to Disney Animation, where they wrote Winnie The Pooh and Frozen , then on to Pixar for Coco and more. After the two married in 2003, they started developing a version of Up Here for the stage. It was a completely different story with completely different characters than the Hulu series that debuted in late March (page 44), but it contained the same underlying themes and ideas. The couple workshopped Up Here with the Roundabout Theatre and then did a version at the La Jolla Playhouse in 2015. In retrospect, Anderson-Lopez says, “it needed Steven Levenson, Danielle Sanchez-Witzel, Tommy Kail and the streaming TV genre to find its true footing.” Like so many of their projects, Anderson-Lopez says Up Here has been a journey. ICG Magazine caught up with Filmland’s most successful musical husband-and-wife team to hear about the various challenges inherent in their many different avenues of entertainment.

22 APRIL 2023 EXPOSURE

PHOTO BY SARAH SHATZ/HULU

22 APRIL 2023

23 APRIL 2023 04.2023 23 APRIL 2023

How did the process and the story for Up Here change as it moved from stage to streaming?

Robert Lopez: Twenty years ago, when I was first learning how to write musicals in the BMI Workshop, I was taught that for a story to be a good musical, it must ideally be set “long ago and far away,” because everyone knows people in New York in modern times don’t break out into song. We also learned it must be about a larger-than-life, extroverted main character, because for a character on stage to be believably singing their emotions, those emotions must be strong and uncomplicated. I understood the reasons for the guidelines, but I still found them constraining – contemporary stories about ambivalence are the ones that most interest me!

So, what changed? Well, eventually, I got an idea: inside the mind of the most introverted, self-thwarting character are huge feelings, huge emotions, and huge characters and forces of antagonism, none of which anyone else can see –and this world inside the mind would make a great place to set a musical, perhaps about consciousness itself. When Kristen joined me on the project, her first contribution was to make it a romantic comedy because the best way to challenge anyone’s idea of themselves is to introduce a love interest. We worked for 10 years – on and off – developing this stage show. In that version, we only went into the male character’s head, and our “head characters” were zany, made-up, like the “Humbug” and the “Critic.” When the show debuted in 2015 in La Jolla, much of it felt so promising, but the fundamental story of seeing into only one person’s head felt unsatisfying and somewhat lopsided from a storytelling point of view. But we had a hard time envisioning how the piece as it existed onstage could be adapted to show Lindsay’s consciousness, and we put it aside for a few years to finish our work on Frozen Broadway and Frozen II . During the pandemic, our friend Tommy Kail called and asked whether we had any ideas for a streaming musical series. All of a sudden, we became excited to overhaul Up Here for this new medium, with a new story, new characters, and, with a few exceptions, completely new songs. Aside from being a romantic comedy called Up Here set in someone’s mind, the stage show bears little resemblance to the Hulu streaming project.

What was it like working with a Tony-winning artist like Steven Levenson? Kristen AndersonLopez: Bobby and I had always wanted to work with Steven, and there was even a time when we planned to continue working on the La Jolla version with him. Then life and other projects took over, and we lost a few years. Cut to 2019, and there we were at the opening night of Fosse/Verdon , and Bobby and I were so taken with how Steven had crafted this masterpiece that opened windows into the protagonist’s head through their iconic songs. We

knew then and there that we had to somehow revisit Up Here with Steven again. He was the visionary storyteller we needed. An added bonus is that he’s a wonderful human being and friend.

We covered Tommy Kail’s work on the film version of Hamilton [ICG Magazine September 2020]. He seems to have a knack for melding Broadway and Hollywood into one package. How did the three of you work together? RL: We had regular Zoom meetings with Steven and Tommy – and later our fifth partner, Danielle Sanchez-Witzel – to develop the characters and the scope of the show, establishing themes to explore, constantly beating and re-beating the pilot episode, and [deciding] what might be fertile ground for musical moments. We wrote some exploratory songs, some of which remain in the finished product – the song What If was the first song we wrote for it. The main challenge was figuring out who these elusive “head characters” were, how many there would be, how they would be introduced, and what the rules were for them showing up. These parameters were constantly being changed and challenged during our development process. The main change from our original stage concept was that the head characters would not be abstract but based on significant people from the main characters’ past. The idea being that when anyone goes through emotional trauma, a new guardian is created to protect them from that same danger happening again. But as we get older, some of these guardians outlive their usefulness and begin to get in the way of personal growth and true romantic connection.

How did you work with Up Here’s director of photography, Ashley Connor? Is there an example of how music and cinematography overlap? KAL: One of my favorite things about our Up Here process was that we were all working in the same building, which we jokingly named “Up Here University.” We’d be up recording or comping/mixing a song, and Ashley could wander in and see some of how the sausage was made. We would send our songs to the choreographer, Sonya Tayeh, and then wander down to see what her gang was developing. We were all figuring out what this unknown creation was together. There was a fun moment when Sonya and Ashley called us to watch the I Am Not Alone rehearsal. The dancers had big cardboard boxes that stood in for walls, and Ashley was right in the middle of it, working on her shots and angles. Bobby and I were blown away by Sonya’s choices and even more blown away by how those choices would be captured through Ashley’s many lenses. But at that moment, she looked like she was part of the number! Once we got into filming, we realized what a metaphor that rehearsal was. She would be a huge part of the choreography of every single number in the show.

What are the main differences in writing music for a large theatrical franchise like Frozen versus television like WandaVision or Up Here versus stage like Book of Mormon ? RL: In certain ways, writing a song for a musical is the same, no matter what the medium. It’s about creating characters, finding the right moments for them to sing in the story, finding their voices, and then talking through the song until we are ready to write it. This is always the most enjoyable part of our process because it’s just the two of us playing.

Is the collaboration for streaming different from theatrical? KAL: Theater is very iterative. You put something up, watch, learn, go away, and rewrite. There are workshops and previews, and you learn by repetition. With Up Here, we tried to replicate the theatrical collaboration as closely as we could, and we had some blissful days of that kind of work in preproduction. However, once production begins, TV, like time itself, marches ever forward. You execute the plan, you pivot and collaborate during the shooting hours, and it is captured and done by the end of the shooting day. The iterative part begins in post. But during the process, every day is a new adventure.

Did you talk with the editors during post? RL: Yes, as executive producers, we were in very close contact with the editors during post, weighing in at every stage. That’s honestly where the songs found their final shape. Some bits that felt necessary as we were writing needed to be cut in post. Sometimes the entrance point of the music would be changed to make the song feel organic. We realized in post that the opening vamp for our opening number, To Really Know Someone , needed to start a scene earlier in the flashback to connect the flashback to the song beginning in the present day. So, I had to add like 32 bars of piano chords and keep it interesting before the first line of the song!

What is the process of writing the score? Is it always written to rough footage, fine-cut footage, or no footage at all? KAL: We should clarify language – there is a difference between the songs and the score. The songs – there are 18 of them – were all written and recorded before anyone stepped in front of a camera. The “score” is the music that supports the scenes and storytelling, and that part is added in post. The director’s cut always included a temp score curated along with the editor. And we started working with Chris Beck and his team to replace the temp score with their original score after all the executive producers had a chance to sign off on episode cuts.

How different is it to create the “score” or “song” first and then create the footage? RL: The “score,” meaning the underscoring, is always written after

24 APRIL 2023 EXPOSURE

APRIL 2023

the picture is locked. But the “songs” must be finished before production begins since they are essentially as much a part of the script as the dialogue. However, there are parts in a song, such as an intro, transitions, and the end, that sometimes don’t have any lyrics, so they sometimes become fair game during editing and land in the realm of the score – meaning, I have to rewrite them, in favor of making the best show we can.

The music/songs/score for a franchise like Frozen end up having a massive life of their own after the movies are out. Do you see anything like that happening with Up Here ? KAL: One can never anticipate what will happen with any project. We were certainly surprised by Frozen ! We sure hope that people will hear the heart, experience and honesty we have poured into these songs and that these songs will resonate with people’s own experiences and feelings.

How important is the pacing/staging/look of a project on the music itself? RL: Most of our writing gets done before any of the production team is hired. I wish their wonderful work existed for us to be able to draw inspiration from. But usually, it’s the other way around. We make sure they all get the song demos as well as every script so they can take our work into account when they’re planning the look, feel and tone of the show. The director is ultimately in charge of that, and we were very lucky to have one of the greatest of all time in Tommy Kail.

Are there similarities and differences between WandaVision and Up Here? KAL: In some ways, they

are quite different. All the songs for WandaVision were theme songs for television genres throughout the decades. What is similar is that with both shows we are using music to act as a kind of portal into our protagonist’s imaginations, memories, traumas and emotions. Wanda is processing her trauma through these American sitcoms she watched as a child. In Up Here, each song is doing a similar job but in a different way.

Where is musical storytelling right now in features and TV? Do you think it’s growing? RL: Musicals are definitely healthier right now than they were in the 90s when we were starting. They seem to be everywhere you look. And, of course, we both think that’s a really good thing.

What is your favorite part of the process? KAL: I love breaking story at the big-picture level. It’s such a gift to work with geniuses like Steven, Danielle and Tommy and talk for hours, days, and weeks about what we want to say, how we should say it, and most importantly, why? And then later, I love the moment when the story is laid out in front of me, and I can feel the logic of the musical architecture take shape in my mind. It’s truly like I can see a magic scaffold come into focus, like one of those 3D paintings they used to sell in malls. I also just love writing and recording songs with my husband. As Jonathan Larson once said, “What a way to spend the day!”

Tommy talked about finding the moment when the dialogue turns to song. Do you have an example of this, and did you know that going in and write for it? KAL: To once again sing Steven’s much-deserved

praises, he’s such a natural at this. He makes our job easy. But I always talk about how setting up a song is like being a pilot taking off in an airplane. The scene has to follow a straight runway and pick up speed and intensity into the central idea and emotional tone and lead to the discovery or decision the character(s) are going to make somewhere in the song. Just like a pilot, you don’t want to take a sharp turn into another topic that has nothing to do with the song. Similarly, you don't want to be at 10 miles per hour if the song needs you to be at 90 miles per hour.

Do you have a favorite song/moment? RL: I know Kristen’s favorite song is The Truth Is, from episode seven, which summarizes so much of what Lindsay’s character is going through, trying to be herself instead of what the world wants her to be. Mine is probably I Am Not Alone, where you see how much of a romantic Miguel is deep down. Seeing someone’s huge private emotions is so oddly inappropriate and uncomfortable. Yet I think we all kind of relate to it.

What is so different, and key to the story, is the voices in their heads. Were the songs tailored to the visual of the voices? Or the reverse? KAL: That concept is where we began with this whole journey. We always knew that dramatizing the voices, memories, and feelings in our heads that drive the decisions we make was the reason to tell this story. And it was certainly the reason to do this story as a musical, because memories, feelings, and young traumas are bigger than talking. They are as immersive, illogical, repetitive, uncontrollable, beautiful, unpredictable and intangible as music itself. So, it was a perfect storytelling fit.

25 APRIL 2023

04.2023

"Setting up a song is like being a pilot taking off in an airplane... you need to follow a straight runway and pick up speed and intensity into the central idea, emotional tone and discovery the characters will make along the way."

25 APRIL 2023

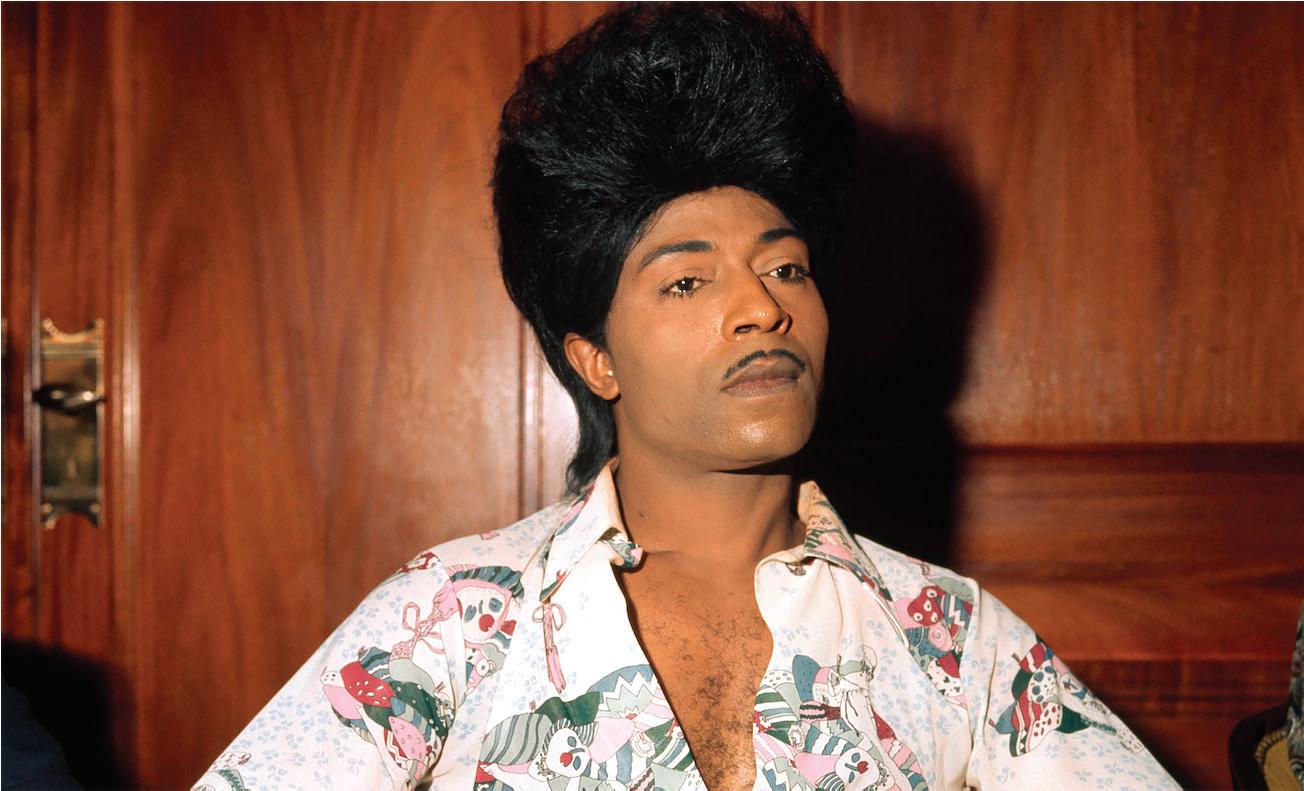

FEATURE 01

Crescenzo Notarile, ASC, AIC, and Jon Joffin, ASC, chart a visual journey beyond Federation borders for Star Trek: Picard

by Kevin Martin

Photos by Trae Patton / Paramount+

Framegrab Courtesy of Paramount+

Crescenzo Notarile, ASC, AIC, and Jon Joffin, ASC, chart a visual journey beyond Federation borders for Star Trek: Picard

by Kevin Martin

Photos by Trae Patton / Paramount+

Framegrab Courtesy of Paramount+

FRONTIER FINAL THE

FRONTIER

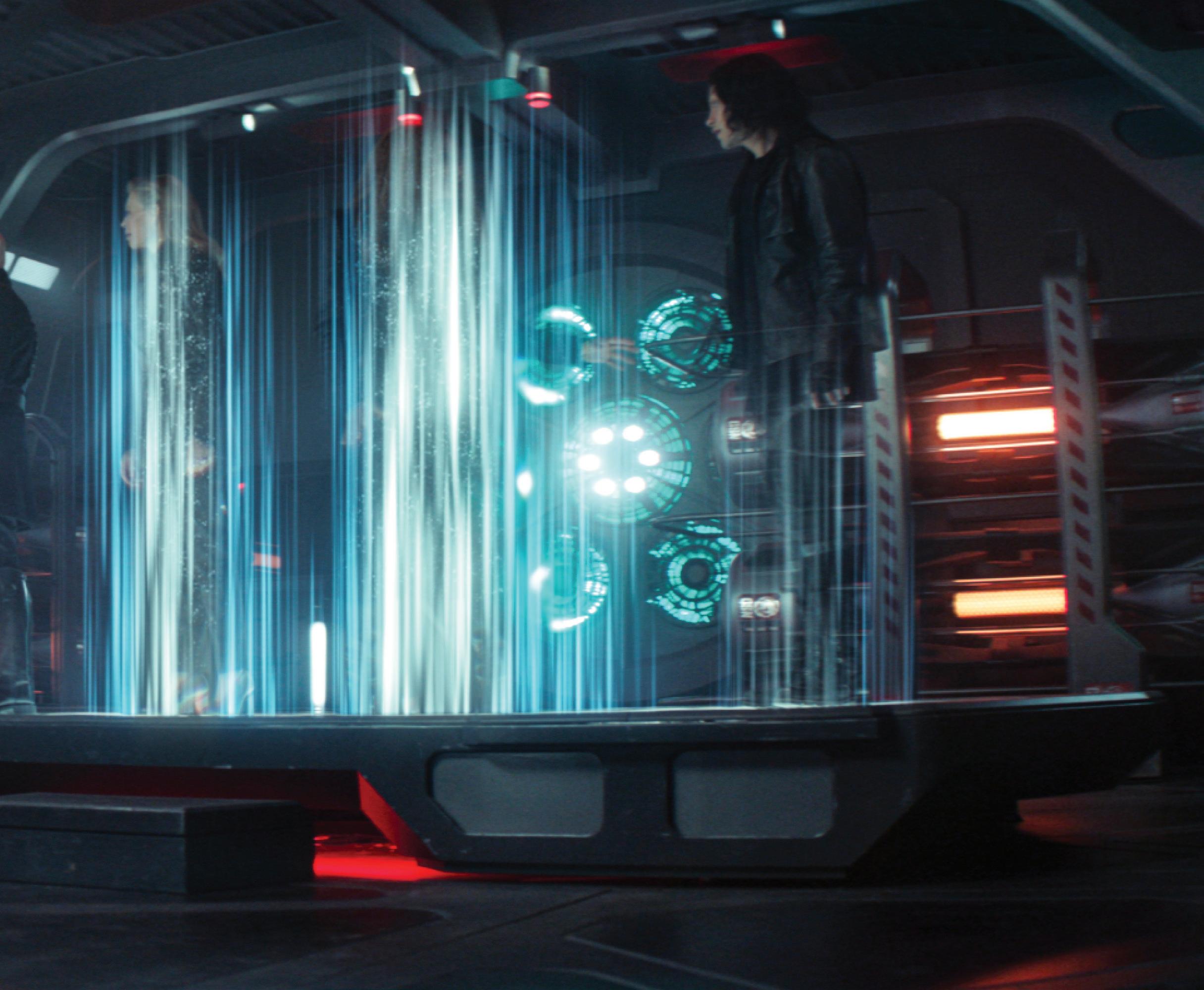

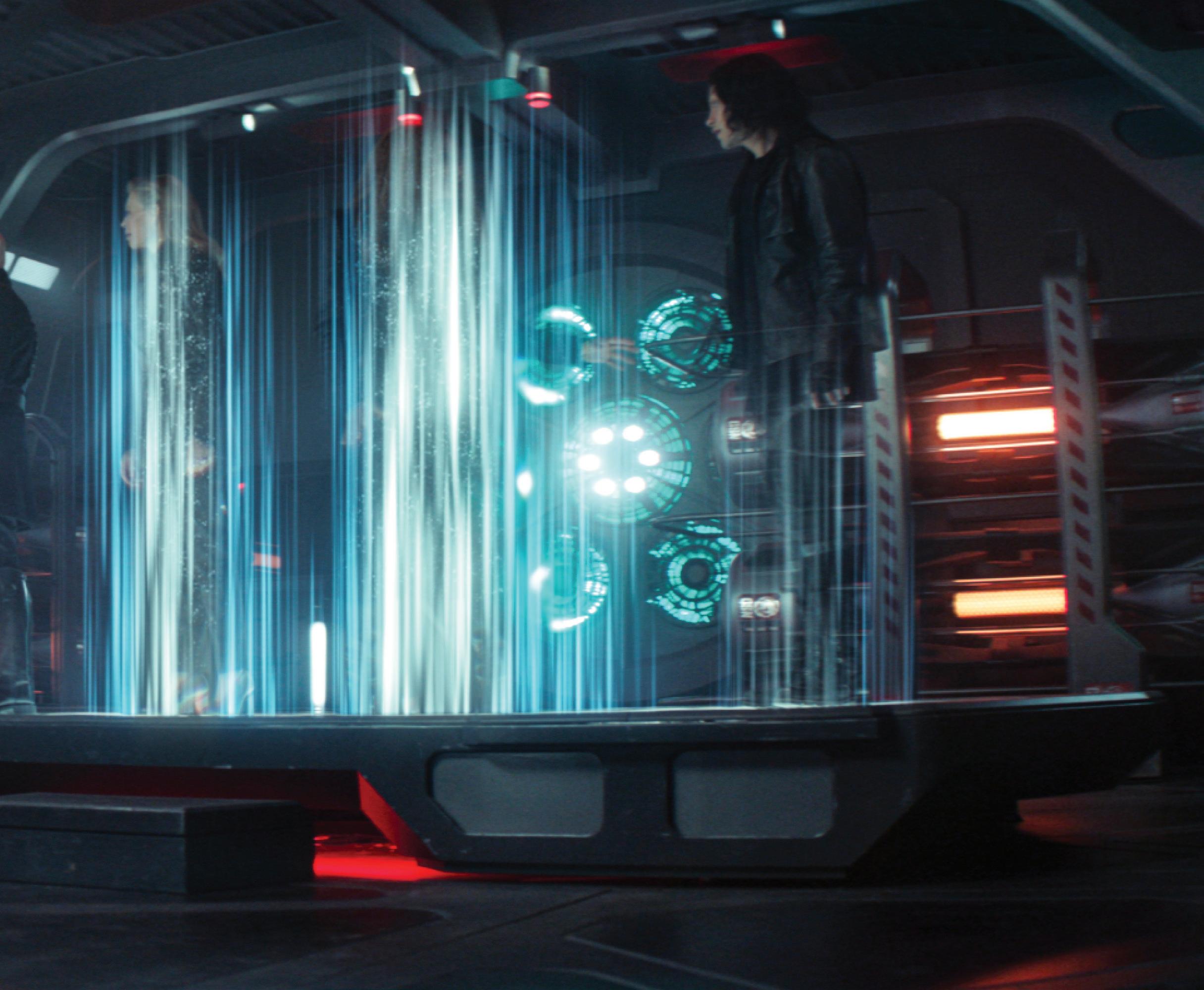

Counting animated as well as live-action series, Paramount+’s investment in the Star Trek brand currently numbers five properties, with more currently in development. While Star Trek: Picard, starring Sir Patrick Stewart, initially eschewed a reunion of Captain Picard’s The Next Generation cast members, Season 3 of the series manages to gradually reunite them – along with some other surprising returnees –in what showrunner Terry Matalas has described as a 10-hour feature.

While Crescenzo Notarile, ASC, AIC, was a newcomer to the science fiction genre before shooting Season 3 of Discovery [along with Glen Keenan, CSC, and Franco Tata], his visual style had made an impression on director Olatunde Osunsanmi when the pair teamed up for an episode of Fox’s acclaimed drama, Gotham . So, when Osunsanmi moved over to Discovery as a director-producer, he tried to recruit Crescenzo (first-name only please!) to shoot Seasons 1 and 2. “We clicked on Gotham over how we looked at using light and smoke to bring beautiful directional sources into frame, and [Osunsanmi] thought that would be great for Trek, ” recalls Crescenzo, who could not accept the entreaties until Season 3 owing to his continuing commitment to Gotham

“When I finally went up to Toronto,” he continues, “I started thinking about how to bring a bold, audacious approach to outer space. I had been lighting with 5K Xenons to get big shafts of light, but there was some question about justifying this look within a sterile starship – and I considered how much creative license I could take. I decided that when the ship is near a moon or planet, that would justify a soft and cooler reflected source coming through the windows. And when the sun was outside, that enabled me to go warmer in hue and deliver the harder shaft of light.”

The plan was for Crescenzo to shoot Discovery’s fourth season and then move over to the first season of Strange New Worlds. But a more urgent situation arose when producers approached him about Seasons 2 and 3 of Star Trek: Picard , which would be shot consecutively, with both DP’s from Season 1 no longer involved. “It was a tough decision, but being able to go back to my home in Los Angeles for the first time in seven years was a big factor,” Crescenzo acknowledges. (Picard is shot in Santa Clarita, unlike the Canadashot Discovery.) “Also, in all honesty, being in on the culmination of Jean-Luc Picard’s space odyssey sounded too good to pass up.”

31 APRIL 2023

Picard’s brain trust includes Executive Producer Alex Kurtzman, Showrunners Akiva Goldsman and Terry Matalas, and Producer-Director Doug Aarniokoski, who shares that “we all pitch in to help new directors get started. By shooting in blocks of two episodes for each director, they have more time to get immersed than would otherwise be possible. My job is primarily about shepherding them with support and answering their questions. Terry tells them where their episodes are at tonally, while I talk more in cinematic terms, and Alex always asks: ‘What does the shot make us and the audience feel?’ Production designer Dave Blass takes on the aspects pertaining to sets and location. With all this support, they can hit the ground running and feel secure about their approach.”

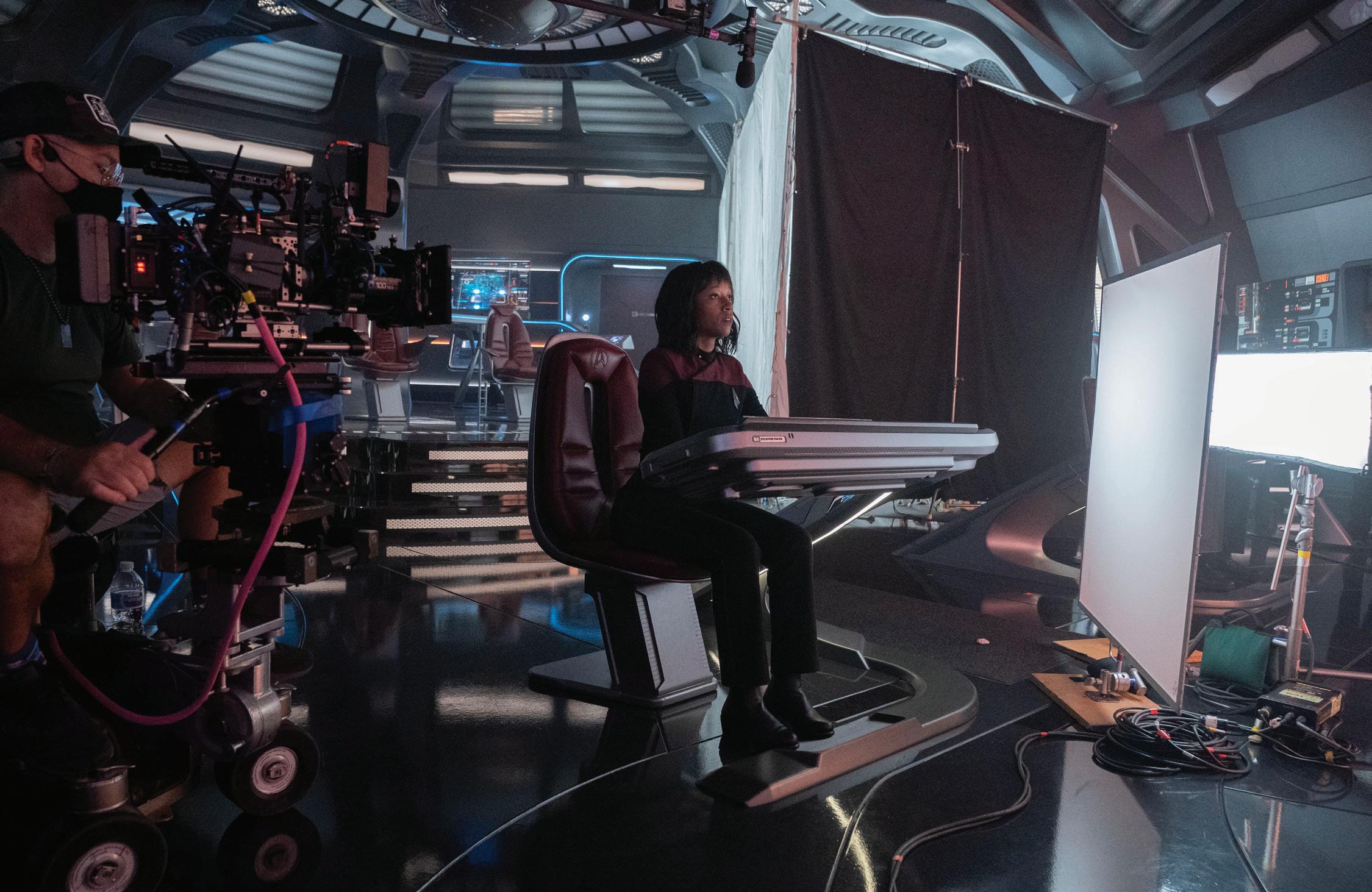

Aarniokoski directed both season openers. “It makes sense since I’m already there in discussions with the designers and crew,” he continues. “And it helps make sure we put our most prepared foot forward. I had the good fortune of working on Discovery since Season 1, which is where we learned how to efficiently shoot the starship bridge sets. They had built a platform system spanning the front end of the set, so even though the set had various levels, this created a flat area where dollies could be used. We built these jigsaw-style pieces for Picard as well, mating them against the platforms that created a kind of dance floor upon which we could move multiple cameras during a take.”

The Star Trek franchise has always been more than just its starships (although some Trekees might dispute that). “We had very specific ideas about differentiating the looks for each season,” Aarniokoski asserts. “Season 2 was heavily out on location, mostly with scenes taking place in the now instead of centuries later, plus continuing action on the first season’s La Sirena freighter. That let us vary the look of things from traditional starship-based storytelling, which we then got back to with Season 3. And since we had a large soundstage, we could vary how we shot the ship interiors, using long lenses inside when called for.”

Production Designer Blass adds, “I told my team up front to take the word ‘fantasy’ out of their minds, because Star Trek isn’t fantasy – it’s a drama with sixty years of history behind it that just happens to take place in outer space. In the past, some designers have looked at Trek with an eye toward making it their own. I thought it more important to deliver the best possible version of what fans would expect to see.” To that end, Blass managed to recruit The Next Generationera art-department alums Michael Okuda, John Eaves, and Doug Drexler. As Blass adds: “We didn’t want to destroy what came before, so with their input, we were able to evolve it, maintaining continuity with The Next Generation.” Even the various spaceship exteriors were

all fully designed and textured as 3D models within the art department, with Drexler handing those off with full tech drawings to various VFX vendors.

Season 2 finds Picard transported from a Federation ceremony into an alternate reality where his culture has turned grotesquely fascist. Blass says, “We used the same Disney Concert Hall location for both realities, but played with fascist iconography, including redand-black banners, to suggest the nature of the timeline changes.” Attempting to put time back on track, Picard and his crew travel back to the early 21st century. “My take was, we’re not traveling back to our present-day,” Blass shares. “Instead, we’re returning to an alternate Trek present that we’ve already seen a bit of in a past Deep Space Nine episode [“Future Tense”] that was prophetic in a lot of scary ways – specifically the homeless problem, plus how media companies control things. We tried to address some of that when approaching the contemporary scenes.”

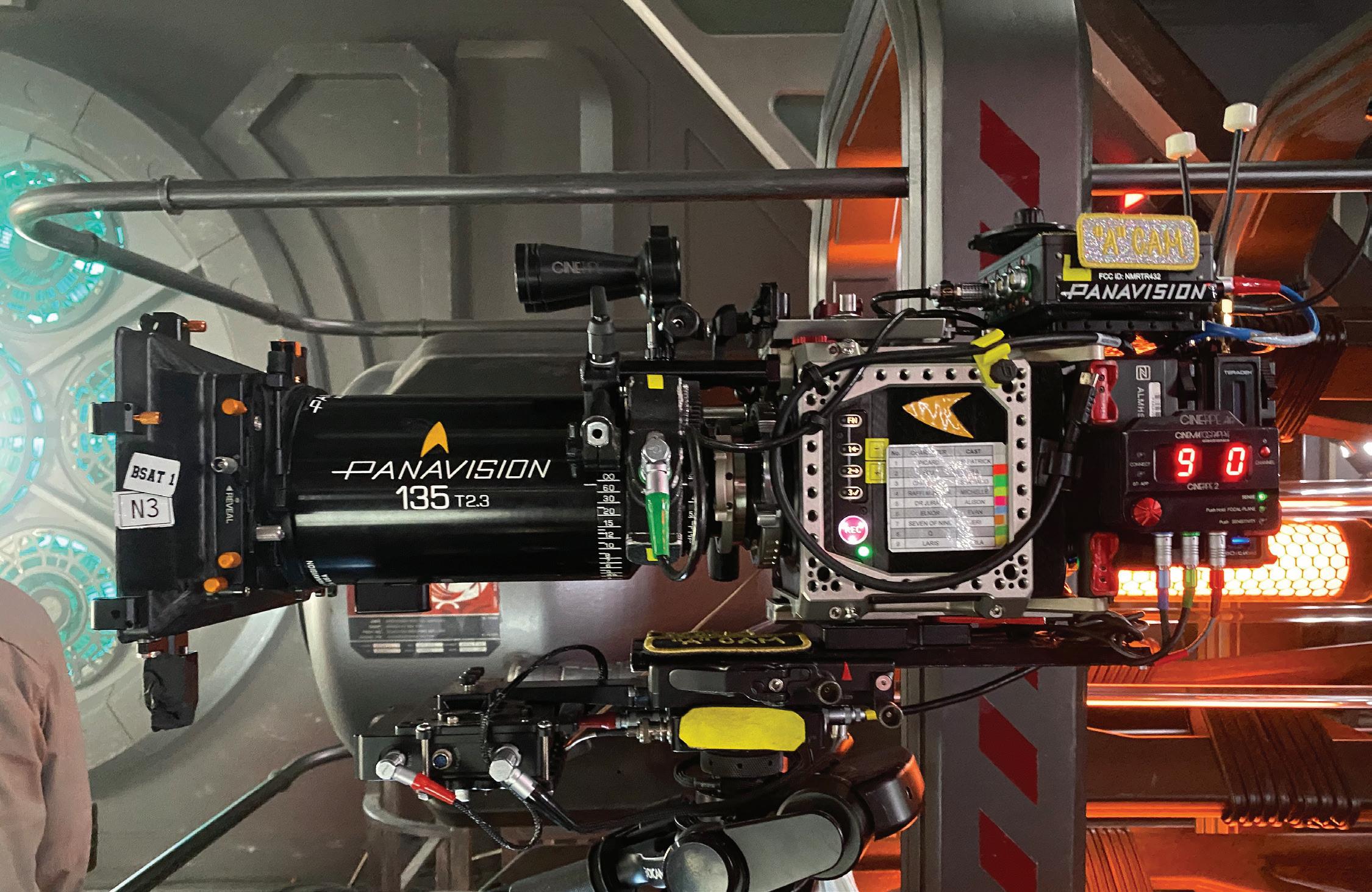

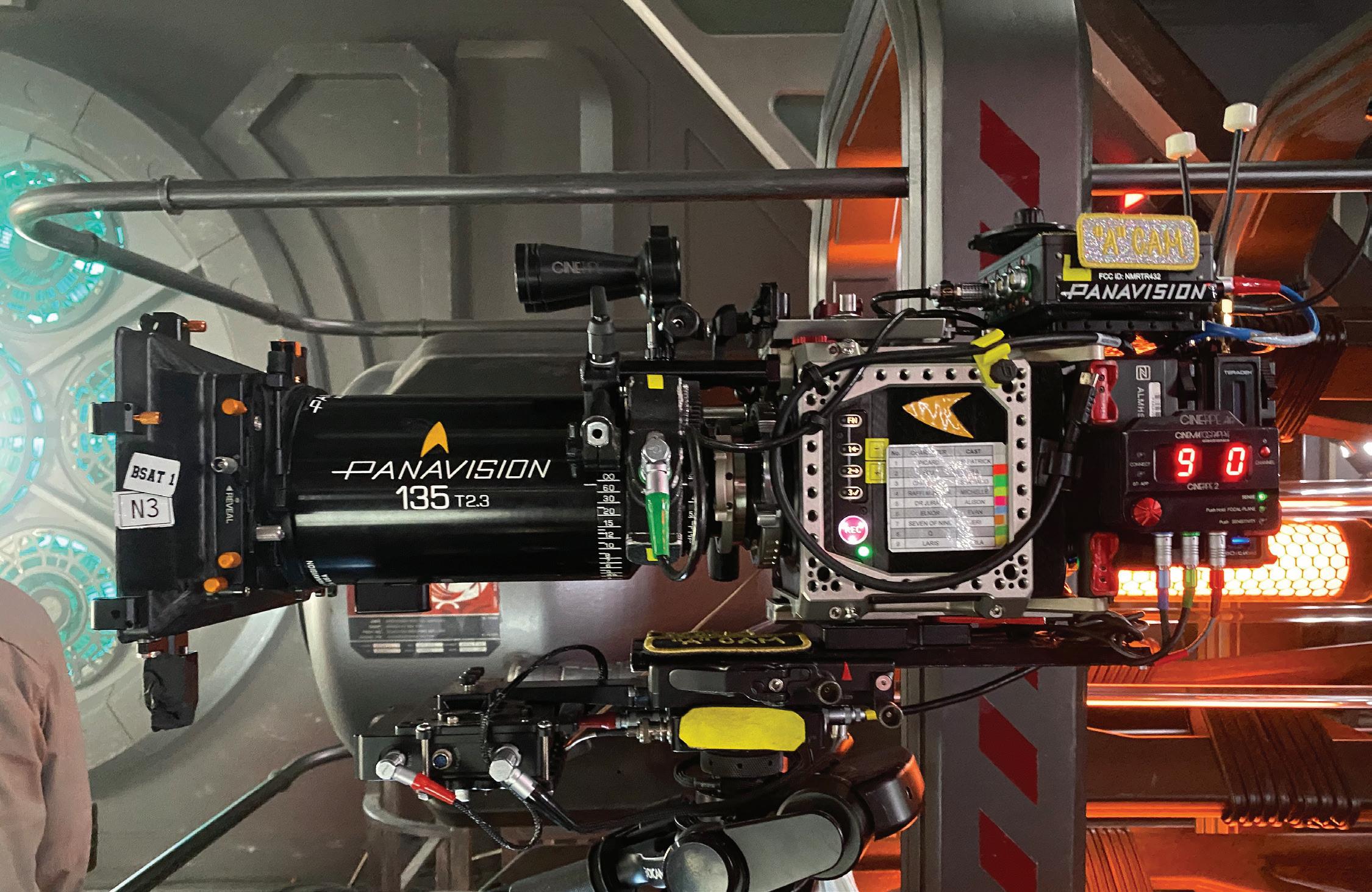

Crescenzo and Season 2 Co-Director of Photography

Jimmy Lindsey, ASC, tested the Cooke SF’s and Panavision T series glass. “I preferred the Panavision T glass because of their presence,” Crescenzo says, “with a faster edge roll-off into softness – bringing out the center, a lens coating that enhances angelic flaring of light, richer contrast and puts a hue of green into the blacks – which I love. The look wasn’t as clinical, though we bolstered that difference through various kinds of diffusion to soften certain dynamics of the frames.”

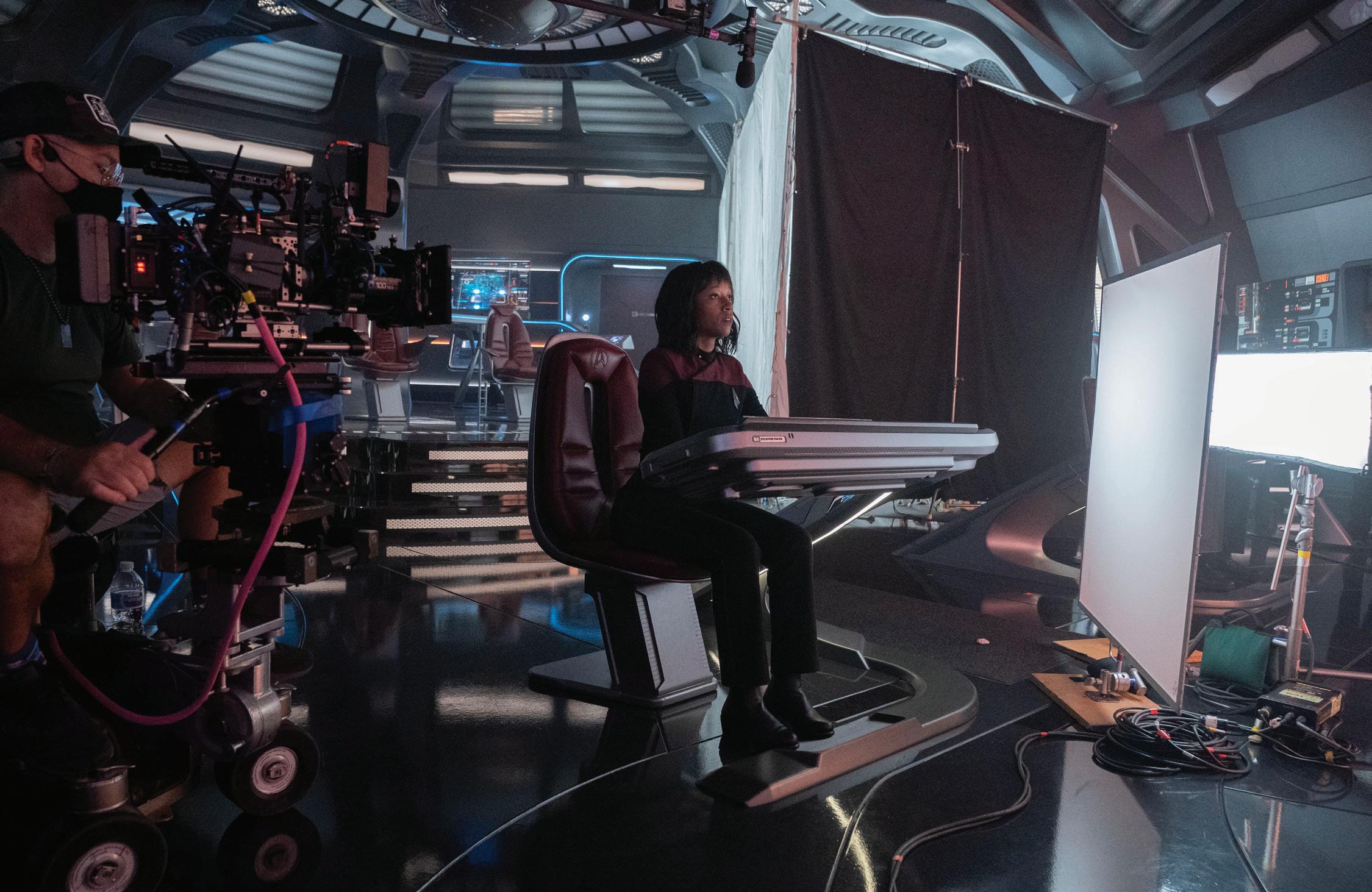

Prep work was done at Panavision Woodland Hills and handled by A-Camera 1st AC Chad Rivetti, who says the DP’s chose the ALEXA Mini “[as] the small lightweight camera body was good for quickly changing from Ronin to handheld or Steadicam. We also used the M7 Evo head on the dolly a lot. During prep, we were able to fine-tune these configurations and develop shortcuts to make the changeover as quick as possible.”

The four keys to good cinematography, according to Crescenzo, are lighting or the absence of lighting, composition, color, and movement, and these tenets are always figured into his approach. He was supported on set by DIT Ryan Kunkleman, who notes that “we wanted the best look for the dailies, so [Crescenzo and I] stood shoulder-to-shoulder on both seasons, working together to figure out the best way to go about creating CDL’s, so post will see what we were doing on set.” Shooting two cameras was the norm in Season 2, with A-Camera Operator Jody Miller and B-Camera Operator Brian Bernstein sometimes aided by C-Camera Operator Ivonne Hecht.

Shooting Season 2 of Picard during the earliest stretch of COVID was challenging.

“My number one responsibility is to not slow down production,” Crescenzo declares. “The experienced professional makes a good call when deciding what to give up on and what not to. It was so frustrating to work

32 APRIL 2023

33 APRIL 2023

REGARDING CHALLENGES UNIQUE TO SHOOTING ANY STAR TREK PROPERTY, DP CRESCENZO NOTARILE (ABOVE) SAYS: “I FOUND THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SPHERICAL AND ANAMORPHIC LENSES WAS MORE SIGNIFICANT, BECAUSE ANAMORPHIC BOKEH IS OVAL, NOT ROUND SO THE PINPRICKS OF STAR PLANET LIGHT WOULD ALSO GO OVAL. TO COMBAT THIS ERROR OF DISTRACTION, I WOULD TRY TO SHOOT WITH A HIGHER STOP AND KEEP THE BACKGROUND SHARPER, AND THE BOKEH OF PLANETS AND STARS AS ROUND AS POSSIBLE."

34 APRIL 2023

efficiently at the start of Season 2 because the standins were wearing masks and face shields. Lighting a face means having to be able to see their eyes and bone structure, but this was like lighting somebody in a space helmet, with reflections hiding the very element I was trying to expose for! Ultimately, you have to play it safe in lieu of time, and go softer, and more diffused, and that sometimes compromises the drama of the lighting, when you want to chisel it to be more defined. Halfway through Season 3, the protocols changed, which helped, but this was all very daunting. I have a rep for lighting women from my music-video days with Beyoncé, Mariah Carey, and many others, so I diligently tried to protect and do right by actresses Michelle Hurd and Jeri Ryan in spite of all this.”

Other Trek-specific difficulties also became evident.

“I found the differences between spherical and anamorphic lenses was more significant, because anamorphic bokeh is oval, not round,” Crescenzo continues. “So, with starfields outside the windows, the pinpricks of star planet light would also go oval. To combat this error of distraction, I would try to shoot with a higher stop and keep the background sharper, and the bokeh of planets and stars as round as possible. If I couldn’t accomplish that, then I’d figure out in advance and have my 1st AC order sphericals for the day.”

Season 1 had briefly featured one starship bridge, but, for two episodes in Season 2, on the Stargazer bridge (revamped and further developed into the Titan’s bridge for Season 3), Blass went all out. “The paint was barely dry on what we had done, when our thinking suddenly had to go toward turning it into the Titan, ” the designer recalls. “Since this was a different class of vessel, we needed new graphics to represent that aspect, which meant settling on the ship’s look quickly, since generating playback graphics can take days or weeks. We had thought about using an LED wall for the viewscreen, but then the question became: ‘Hey there guys, can you tell me exactly what you need to be seeing? If not, this wall is just going to get turned into the most expensive electric green screen in history.’”

Crescenzo credits Chief Lighting Technician Len Levine and Lead Lighting Console Programmer Josh Thatcher with designing and rendering the intricate bridge displays. “Josh dealt with more than a thousand lights from his board and could create dynamic and frenetic lighting patterns, letting us achieve the needed intensity and visual dramaturgy for various dramatic moments in the vessel control rooms,” Crescenzo recounts. “Lighting the ship was not as easy as it looks, as there are over a 1000 lights at your fingertips on the board, pulsing, flashing, chasing, changing colors, lifting keys, dropping fills, all on the fly, shot by shot, and within each shot, all depending on what kinetic

lighting is happening outside the windows via VFX, then marrying the interactive lighting within the ship – all while keeping all casts faces beautiful and strong. When we get into medium and close shots, I find that I can chisel the drama by adding negative fill and turning set-embedded lights off. We can bring supplementary lights in and place them lower on stands to get direct light into the actors’ eyes, which isn’t possible during the wides.”

The original plan was for an episode rotation that allowed Crescenzo to shoot the concluding episodes of Season 3; but when Lindsey left, things changed, forcing him to shoot the end of Season 2 instead (and, consequently, not opener to Season 2). “With Season 3, there is a huge difference in that we are returning to a Federation starship as the base for most of the action,” explains Aarniokoski. “We aimed for a cinematic look that differentiated us from the other two current liveaction Trek series. So, we brought in Jon Joffin [ASC] to implement a new look in the first two episodes.”

Joffin describes Rogue One as the first Star Wars film he connected with visually, owing to its sense of realism. “That’s the broad stroke I led with on this project,” he shares. “I was brought on for some of the work I had done with a heightened look, using very subtle soft light on faces. Whenever there is a bright key, to me it looks ‘lit,’ so I try to bring the key light down to appear natural and real.

“Because I came on so late, there wasn’t the time to work with Crescenzo in advance,” Joffin adds, “so I relied on what I had discussed with Doug and Terry.” Part of that involved the use of smoke on stage, “which helped desaturate the background and put more of an emphasis on our characters,” he continues, “keeping the foregrounds snappier and more colorful while also taking the digital edge off our capture. We did an early scene in the Picard mansion that let us showcase this approach. As scripted, it was to all take place at night, but I pleaded to start it in the afternoon with sunlight streaming through the windows so that we have a progression into night from a kind of golden look.”

Joffin praises the work of B-Camera Operator Joey Brian Morena, “who would make an amazing A-cam op as well,” he adds. “But having him on B was great because Joey always finds great shots and consistently delivers. As for [1st AC] Chad [Rivetti], I found him brilliant, not just pulling focus but the way he runs the department.”

Rivetti says Joffin wanted to shoot wide open as much as possible. “So, Season 3 was one of the more challenging shows I’ve done.” While Rivetti still uses a CineTape and a steel tape measure to check distances, he also employs a 7-inch SmallHD Cine7 with Teradek 4K wireless video. “The monitor is mounted to my Preston FIZ 3 focus handset,” he describes, “giving me the freedom to follow the camera and have the best

35 APRIL 2023

view of the actor and camera moves. We did a lot of push-in to close-ups on actors’ faces, wide-open on the 135 millimeter, and pushing from 10/12 feet to 4 feet. Jon liked the look of a longer lens, often opting for doing wides on a 60- or 75-millimeter set up further away.”

Joffin also used an elaborate array of diffusion to light close-ups on the bridge. “All the built-in set lighting gives you ambience, but it doesn’t light faces,” he states. “We brought in huge soft sources in the foreground, which made the set unrecognizable because these 10-by-10 and 10-by-20 frames would be hiding most of the bridge consoles and walls when we lit for the actor.” Joffin also introduced visual aberrations into the image through the use of a Lensbaby Omni, which, he says, “lets you mount little crystals on the matte box filter holder so you see some rainbow colors through them. There were four or five made, and we used them frequently on the bridge.”

As the creatives wanted Season 3 to look cinematic and rich, Joffin explains that “the LUT we had basically crushed everything. Shooting with ½ to 1 stop ND, we could dig more detail out of the darkness if need be. Ryan [Kunkleman] was very good at pushing that,

which is quite an art since you have to watch the highlights. I hadn’t shot with T-series lenses before, but Dan Sasaki told me they were designed to be shot wide-open, so I was at T2.3 most of the time.” Joffin also varied his shutter – but not for the usual no-blur benefit. “One thing I do is play with the shutter for the sake of exposure,” he smiles. “I always want to shoot wideopen, and while ND takes up a full stop, sometimes I want to open more, so closing the shutter from 144 to 270 degrees in increments can achieve that.”

Season 3 A-Camera Operator Nicholas Davidoff shares how Crescenzo and Joffin both faced extra layers of complexity. “Under normal circumstances, you light real-world sets and it can be routine,” Davidoff describes. “But aboard starships with dozens of monitors everywhere and miles of cable linking them to controllers for playback, a huge, coordinated effort was needed to ensure the proper displays were timed at the right moments during the take and shown at the necessary intensity levels which were always changing. Reflections were a constant problem with so many screens and glass everywhere. Another unique challenge for the DP’s were the arrays of pulsing, colored lights designed throughout all the ships. During the take, these practical lights were constantly dimming

36 APRIL 2023

and fading in color and intensity depending on the status of the ship. All that takes time to program and test and under the very tight schedule we had, let's just say things never got boring. We were always charging ahead on all cylinders, with only a few takes to get it right.”

Davidoff ended up going handheld throughout much of Season 3.

“It was to convey a visceral feel and amplify the energy of what was going on,” he continues. “I spent many hours in various handheld modes — easy rigs and butt dollies and on the shoulder — as we got in close to the characters, but also as we moved around the various decks and through the corridors of the various ships. Lengthy dialogue passages were often covered somewhat classically, but then you get an ungrounded kind of feel with closeups when the characters are in each other’s faces.”

For scenes on a wild planet of criminals, production shot nights at Blue Sky Ranch. Blass’s art team built a city with foreground wires going across the sky, and LED strip lights, so when Davidoff would tilt up, “it isn’t just a classic ‘all CG’ reveal,” he explains. “While there are distant city elements added in post, a lot was there incamera. We also built a cable cam to fly lights to suggest

ships passing overhead.” Joffin enlivened the cityscape by using the IVL Square system, which Len Levine had found, creating a mysterious beam of light that gave additional perspective to the environments. When a character experiences a drug reaction, Joffin trotted out an old favorite. “I had this cheap Helios 44 lens that is very blurry and let me swirl the background.”